INTRODUCTION

Regional myocardial blood flow is very heterogeneous. This has been found by injection of radioactively labeled microspheres, or the “molecular microsphere” iododesmethylimipramine, and measuring the deposition of these flow indicators in small sample pieces into which the heart has been cut (King et al., 1985; Bassingthwaighte et al., 1987; Bassingthwaighte et al., 1988). It was also found that the spread of the flow distribution increases with the spatial resolution of the measurement. This could be expressed (Bassingthwaighte et al., 1988; Bassingthwaighte, 1988) via a mathematical relation between the relative dispersion RD, defined as the standard deviation of the flow distribution divided by its mean, and the average mass, m, of the sample pieces into which the heart was divided:

| (1) |

where m0 is an arbitrary reference mass. Since the number of sample pieces equals the total mass M divided by the average mass of the sample piece it follows that

| (2) |

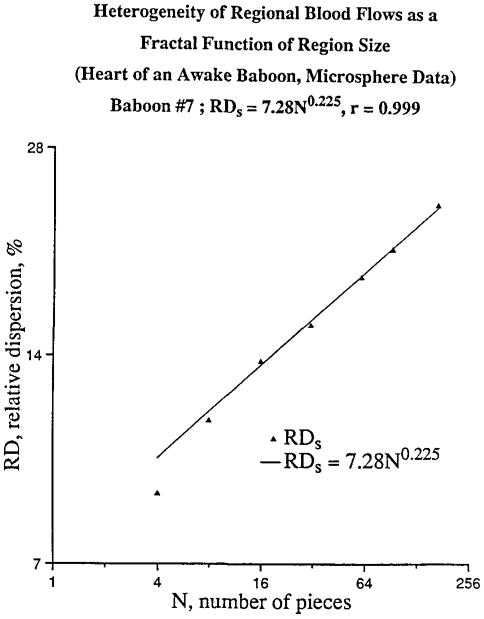

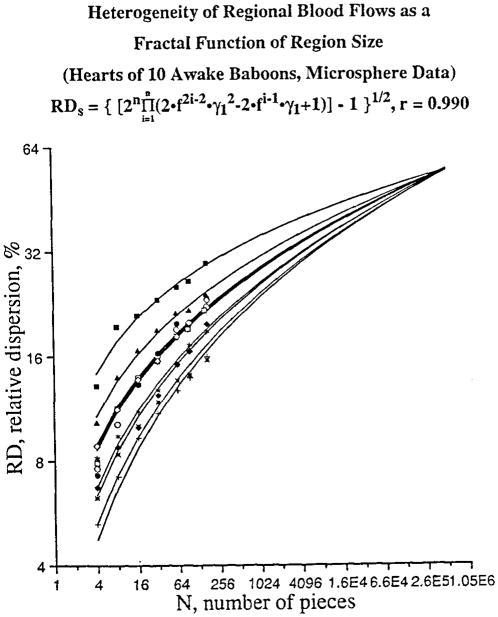

The power laws fit the measurements very well for all except the larger sample pieces (see Figure 1). Such a relation between a measure and the spatial resolution of the measurement has been found for the geometrical features of certain types of mathematical sets that are called fractals. Equations 1 and 2 are therefore often called fractal relationships and parameter D is called the fractal dimension.

Figure 1.

Relative distribution of myocardial blood flow as a function of the number of sample pieces into which the heart is divided. The relative dispersion of flow, RD, has been corrected for measurement noise. Results for one baboon.

WHAT ARE FRACTALS?

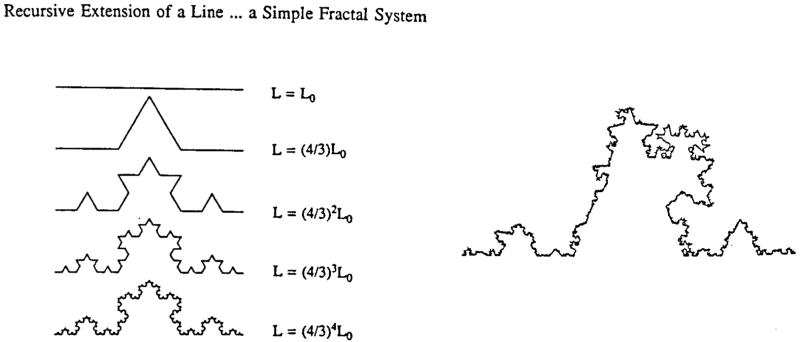

Fractals are mathematical geometrical constructs that resemble the geometrical patterns found in nature (Mandelbrot, 1983). The latter are called natural fractals. The concept of fractals has been invented and propagated by B. Mandelbrot (1983) and is explained and visualized in an esthetically pleasing way by Peitgen and Richter (1986). Mathematical fractals exhibit an infinite amount of detail, which they have acquired via an endless recurrent iteration defining the (n+1)th generation from the nth. An example is given in Figure 2, where a side of a snowflake is generated by replacing the middle third of all straight lines repeatedly by two line segments of similar length. The resulting figure forms one side of Koch’s snowflake. It can be shown that the length L of the resulting figure depends on the length of the line segment ε in that particular iteration

Figure 2.

The Koch snowflake. The left panel shows a deterministic recursive process. The right panel shows the result of a recursion with a random process.

| (3) |

where ε0 is an arbitrary reference length (Mandelbrot, 1983). The parameter D turns out to have the properties of a dimension and is called the fractal dimension. By repeating the iteration a figure of “infinite” complexity can be generated, which has “infinite” length. It is also clear that a part of Koch’s snowflake is a small replica of the whole. It shares this property of self-similarity with many other fractal structures. The pattern of the figure resembles that of a coastline. Indeed, Equation 1, which is generally valid for fractals, has been applied to real coastlines. Now ε represents the scale of the details on a geographical map that are taken into account when determining the length of the coastline. In practice one can do that by setting a caliper to width ε and walking it along the coastline on a map. Equation 2 turns out to be valid for the coastal length found in this way: the coast is a natural fractal and the Koch snowflake can serve as a crude mathematical model for it. Introducing an element of chance in the iterations for the generation of the Koch snowflake makes it look more like a natural coastline (Figure 2, right panel). The relative dispersion of blood flows in the heart, given by Equation 1, seems to behave according to the fractal law, Equation 3. However, it is not immediately obvious how the relative dispersion of flow can be compared with the length of an object. We will explore this in the next section.

THE FRACTAL RELATIONSHIP FOR DISPERSION OF FLOW CAN BE DERIVED FROM CORRELATION BETWEEN NEIGHBORS

Imagine that an organ is divided into voxels (volume elements) and that the flow to the voxels has a spread with a certain standard deviation. The flow in neighboring voxels also has a certain correlation coefficient r. We have shown (van Beek et al., 1989). that when r is constant, irrespective of the size of the voxels into which the organ is divided, the relation between voxel size and relative dispersion of flow is given by Equations 1 and 2 We found that the relation between r and fractal dimension D is given by

| (4) |

This derivation showed that the fractal relationship holds as long as the correlation of the flows in neighboring voxels is constant. This idea of a property being constant over many magnitudes of scale, self-similarity, is a feature of fractals (Mandelbrot, 1983). When the local flows are completely random, r = 0, the fractal dimension D is 1.5; when they are highly correlated with r = 1, it follows that D is 1.0.

The fractal law of Equation 1 seems to describe the experimental findings well. It therefore resolves the question of how to compare results on flow heterogeneity obtained by various investigators who used different spatial resolutions in their measurements. The fractal D found for Equation 1 is around 1.15 for myocardial blood flow, which means that the correlation between flows in adjacent voxels is around 0.63, according to Equation 4, no matter the voxel size, so long as equal sizes are compared.

FRACTAL NETWORKS

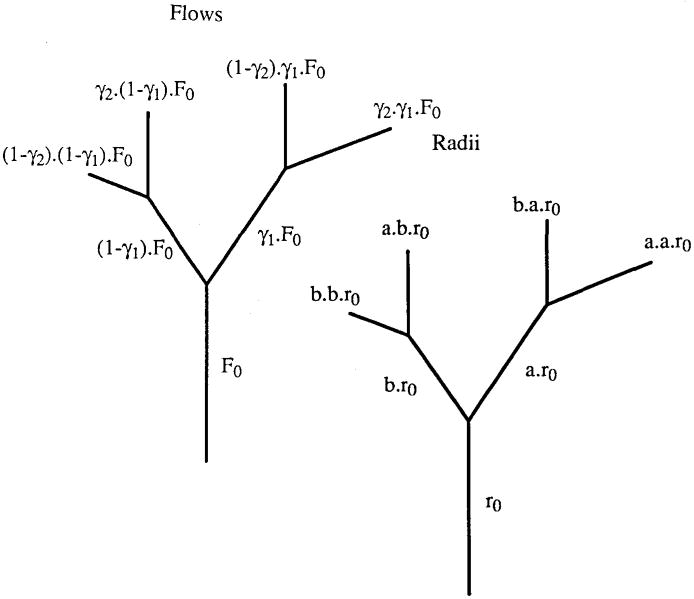

Blood vessel networks tend to show the same pattern which repeats at various levels of scale. The fact that a fractal relation described the measurements very well inspired us to investigate whether the distribution of flow might be explained by a network of blood vessels having a fractal geometry. We started to look at one of the simplest geometries: a repeatedly branching bifurcating network (see Figure 3). The radius r0 of the parent vessel in this network is reduced by a factor a in the longer daughter branch at the bifurcation, and by a factor b in the shorter one.

Figure 3.

Bifurcation of blood vessels. In the right panel the recursion for the vessel radius is shown. A similar recursion applies to the length of the vessel segments. The left hand panel shows the distribution of flow. A fraction γ of the blood flows into one of the branches, 1−γ flows into the other. This fraction is the same for all bifurcations of one generation, but may vary across the generations.

The radius r0 of the parent vessel in this network is reduced by a factor a in the longer daughter branch at the bifurcation, and by a factor b in the shorter one. The length L0 is decreased by a factor fL and fs for the longer and shorter branches. This pattern of branching is repeated and an arterial tree is generated. It is connected to a similarly constructed venous tree with a different r0 and L0, but with the same factors a, b, fL and fs. Using Poiseuille’s law, we deduced from this geometry that the flow distribution in such a network can be represented by an asymmetry parameter γ which equals fs · a4/(fL · b4 + fs · a4). A fraction γ of the flow enters one branch; a fraction 1−γ enters the other. When the geometrical branching parameters are constant all through the network (Model I), the asymmetry parameter γ is independent of the generation. For this case we derived the following relation between the relative dispersion of flow found in the branches after a certain number of bifurcations and the number of branches N concerned (van Beek et al., 1989):

| (5) |

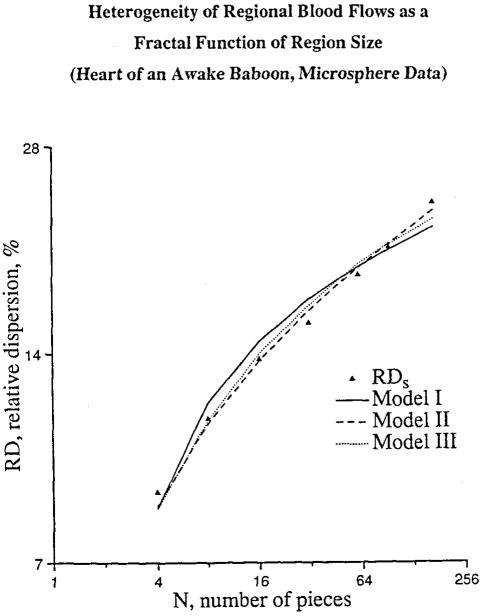

The number of symmetrical branches, with γ=0.5, is another free parameter in this model. In order to fit the experimental data we assumed a one to one correspondence between blood vessels and sample pieces. The fit to data on one baboon is given in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Fit of the models to the RD obtained experimentally in one baboon. The highest number of pieces corresponds to the number of sample pieces into which the heart was actually divided. The data for lower numbers of sample pieces (corresponding to bigger pieces) were obtained by aggregating a number of the smallest pieces.

When the geometrical parameters depend on the generation of branching, so does γ. Model II is defined by a geometric progression for γ:

| (6) |

where i is the index for the generation of branching and γ1 is the asymmetry parameter for the first generation. The relation derived (Van Beek et al., 1989) for this model is:

| (7) |

The resulting fit to the data is given in Figure 4.

Model III was generated by drawing γ for each branch point randomly from the normal distribution with mean 0.5 and variance σ2. To do this 10 trees were generated on the computer for variance 1. They were then scaled to have variance σ2. Parameter γ1 for the first generation was an independently chosen deterministic parameter. The fit of model III to the data is also shown in Figure 4.

The goodness of fit of the models to the data was assessed by using the coefficient of variation given by:

| (8) |

where ymeasured are the observed values, ymodel are the estimated values given by the model, and n is the number of measured points from which the degrees of freedom of the model are subtracted. The mean coefficient of variation for model fits to measurements on 10 baboons was 0.0647, 0.0336 and 0.0411 for models I, II and III respectively. For measurements on 11 sheep this was 0.0720, 0.0438 and 0.0499 respectively. Model II fitted the best in general, while the stochastic model III was almost as good. The value of gamma was around 0.45 and σ for model HI was around 0.05. This indicates that a moderate degree of asymmetry at branch points can lead to the marked heterogeneity of flow in the myocardium, due to repetitive branching.

THE RELATIVE DISPERSION RELEVANT FOR MICROVASCULAR EXCHANGE

The local flow determines how much of a substrate or indicator is delivered to the tissue. When the capillary permeability is finite, flow also determines the extraction fraction E of the molecules. This is exemplified by the Crone-Renkin formula E = 1 − e−PS/F which expresses the extraction, E, as a function of the local permeability-surface product PS and flow F. This formula is valid when the reflux of molecules from tissue back into the capillary is negligible. The estimate of permeability in an organ will be quite wrong when the heterogeneity in flow is not taken into account (Bassingthwaighte and Goresky, 1984). In order to estimate the PS correctly we must obtain an estimate of the relative dispersion of flow at the level of the microvascular exchange region.

We have defined the microvascular unit mass as the amount of tissue to which a single arteriole delivers blood and nutrients. Flow heterogeneity within the microvascular unit might exist but is of less importance since diffusion tends to equalize concentration gradients.

The first indication that every heart might approach a similar maximum relative dispersion was reported by Bassingthwaighte et al. (1989). For 21 animals studied (10 baboons and 11 sheep) it was found that hearts with a larger RD at the reference sample size of 1 gram had a smaller fractal dimension D, when Equation 1 was fit to the data. In other words, the best fit lines to each animal on a log RD versus log m plot tended to have a shallower slope when the RD(m0) was large, and tended to have a steeper slope when the RD(m0) was small.

However, the power law might fail when the maximum RD is approached asymptotically. For this reason, we believe that our best fitting branching model (model II), which can account for the curvature seen in the experimental data, would be the favorable tool for estimating the RD at the exchange level.

With an analytical solution available to model II (Equation 7), the model function can be extrapolated beyond the range of the experimental data. The idea was to introduce a common point at a very high spatial resolution (large N) into the data set of each animal. After being forced through this common point, the best model fits are found for each animal. Figure 5 shows the solution to the data for 10 baboons when the common point introduced was at an RD of 55%, and the hearts were theoretically sliced into 524288 pieces, average mass 52 μg which corresponds to a cube with a side of about 400 μm. The overall correlation coefficient between the model and the data from ten animals was > 0.99.

Figure 5.

Relative dispersion of myocardial perfusion as a function of the number of sample pieces into which the heart is cut. The common point introduced is at N equals 524288, and an RD of 55%. The data are for 10 baboons.

Is this the microvascular unit point? This question cannot yet be answered. Although a trend was seen in the solutions, no clear cut “winner” was obtained after numerous different common points were introduced into the data sets. The next step will be to use these results in accordance with anatomical studies and autoradiographic flow heterogeneity studies to gain further insight into the branching and flow characteristics of the myocardium at the microscopic scale. However, it did become very clear that the branching networks were much more accurate in assessing the spatial heterogeneity of regional myocardial perfusion than the power law equation.

DISCUSSION

Although the fractal networks described here do not resemble the coronary vasculature in detail (Bassingthwaighte et al., 1974), they seem to describe the measured relative dispersion of flow rather well. The network is similar to the one used by Pelosi et al. (1987) to analyze total resistance. Zamir and Chee (1987) analyzed vessel lengths and diameters in the arterial part of the human coronary network, using a labeling scheme compatible with our bifurcating network. They found that length and diameter of vessel segments decreased steadily as a function of generation number.

An alternative interpretation of the mathematics used for deriving the distribution of flow in the networks is possible. We can interpret γ as indicating the fraction of flow that is found to go to one half of the tissue, and 1−γ as the flow which goes to the other half of the tissue, when a piece of tissue is cut into 2 sample pieces. Then γi is the average distribution fraction that is found for the ith subdivision of the tissue.

CONCLUSION

Fractals form a very useful tool for modeling the capricious form and behavior found in Nature. Simple networks of blood vessels, defined in an economic fractal way, explain the heterogeneous distribution of flow in the myocardium very well.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants RR01243 and HL19139.

References

- Bassingthwaighte JB, Yipintsoi T, Harvey RB. Microvasculature of the dog left ventricular myocardium. Microvasc Res. 1974;7:229–249. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(74)90008-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassingthwaighte JB, King RB, Sambrook JE, Van Steenwyk B. Fractal analysis of blood-tissue exchange kinetics. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1988;222:15–23. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-9510-6_2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassingthwaighte JB, Goresky CA. Modeling in the analysis of solute and water exchange in the microvasculature. In: Renkin EM, Michel CC, editors. Handbook of Physiology, Sect 2 The Cardiovascular System, Vol IV, Microcirculation. Chapt 13. Bethesda, MD: American Physiological Society; 1984. pp. 549–626. [Google Scholar]

- Bassingthwaighte JB. Physiological heterogeneity: Fractals link determinism and randomness in structures and functions. News in Physiol Sci. 1988;3:5–10. doi: 10.1152/physiologyonline.1988.3.1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassingthwaighte JB, Malone MA, Moffett TC, King RB, Little SE, Link JM, Krohn KA. Validity of microsphere depositions for regional myocardial flows. Am J Physiol. 253 doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1987.253.1.H184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Heart Circ Physiol. 1987;22:H184–H193. [Google Scholar]

- Bassingthwaighte JB, King RB, Roger SA. Fractal nature of regional myocardial blood flow heterogeneity. Circ Res. 1989;65:578–590. doi: 10.1161/01.res.65.3.578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King RB, Bassingthwaighte JB, Hales JRS, Rowell LB. Stability of heterogeneity of myocardial blood flow in normal awake baboons. Circ Res. 1985;57:285–295. doi: 10.1161/01.res.57.2.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandelbrot BB. The fractal geometry of nature. San Francisco: W.H. Freeman and Co; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Peitgen HO, Richter PH. The beauty of fractals: images of complex dynamical systems. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Pelosi G, Sarossi G, Trivella MG, L’Abbate A. Small artery occlusion: a theoretical approach to the definition of coronary architecture and resistance by a branching tree model. Microvasc Res. 1987;34:318–335. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(87)90065-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Beek JH, Roger SA, Bassingthwaighte JB. Regional myocardial flow heterogeneity explained with fractal networks. Am J Physiol. 1989;257(5 Pt 2):H1670–80. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1989.257.5.H1670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamir M, Chee H. Segment analysis of human coronary arteries. Blood Vessels. 1987;24:76–84. doi: 10.1159/000158673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]