Abstract

Objective

The goal of this study was to assess the efficacy and tolerability of lis-dexamfetamine dimesylate (LDX) as an adjunct to nicotine replacement therapy in adult smokers with ADHD who were undergoing a quit attempt.

Methods

Thirty-two regular adult smokers with ADHD were randomized to receive LDX (n = 17) or placebo (n = 15) in addition to nicotine patch concurrent with a quit attempt.

Results

There were no differences between smokers assigned to LDX versus placebo in any smoking outcomes. Participants treated with LDX demonstrated significant reductions in self-reported and clinician-rated ADHD symptoms. LDX was well tolerated in smokers attempting to quit.

Discussion

In general, LDX does not facilitate smoking cessation in adults with ADHD more than does placebo, though both groups significantly reduced smoking. LDX demonstrated efficacy for reducing ADHD symptoms in adult smokers engaging in a quit attempt.

Keywords: adult ADHD, lis-dexamfetamine dimesylate, smoking

ADHD affects millions of children and adults in the United States and is a significant independent risk factor for smoking (Kessler et al., 2006; Lambert & Hartsough, 1998; Milberger, Biederman, Faraone, Chen, & Jones, 1997; Milberger, Biederman, Faraone, Wilens, & Chu, 1997; Molina & Pelham, 2003; Pomerleau, Downey, Stelson, & Pomerleau, 1995). Individuals with ADHD or high levels of ADHD symptoms also start smoking at an earlier age, become more dependent, and are more likely to progress from smoking experimentation to regular use (Fuemmeler, Kollins, & McClernon, 2007; Kollins, McClernon, & Fuemmeler, 2005; Milberger, Biederman, Faraone, Chen, et al., 1997; Rohde, Kahler, Lewinsohn, & Brown, 2004; Wilens et al., 2008).

In addition to conferring risk for initiation, progression, and maintenance of regular smoking, several studies have reported that a diagnosis of ADHD or high levels of ADHD symptoms may decrease the likelihood of successful smoking cessation. In a study of 71 adults with a diagnosis of ADHD, the “quit ratio” (percentage of those who had ever smoked in their lifetime who did not report current smoking) was 29%, compared with a ratio of 48.5% in the general population (Pomerleau et al., 1995). Retrospective analysis of a large cessation study involving transdermal nicotine and bupropion reported that high levels of self-reported ADHD symptoms predicted significantly lower smoking abstinence rates during the trial (Covey, Manubay, Jiang, Nortick, & Palumbo, 2008). Finally, Humfleet and colleagues reported that across several smoking cessation trials involving pharmacological and psychological interventions, only 2% of participants with a childhood diagnosis of ADHD (n = 47) maintained abstinence versus 18% of those without a childhood diagnosis (Humfleet et al., 2005).

The mechanisms underlying poor cessation outcomes among smokers with ADHD are not well understood. Many have suggested that because of the neuropharmacological, cognitive, and behavioral effects of nicotine, cigarette smoking may serve a “self-medication” function among those with ADHD (Glass & Flory, 2010; Heishman, Taylor, & Henningfield, 1994). To date, however, no published studies have directly addressed this hypothesis in a systematic way. It is also possible that smoking cessation is more difficult for individuals with ADHD because of differences in withdrawal severity following abstinence. Several studies have reported that abstinence-induced disruptions in cognitive and affective processes are more pronounced in smokers with ADHD compared with those without the disorder, even when controlling for changes in ADHD symptom severity (Kollins, McClernon, & Epstein, 2009; McClernon et al., 2008, 2011). Moreover, there is evidence that increases in ADHD-related symptoms in the first days following a quit attempt predict worse cessation outcomes among smokers enrolled in a nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) trial (Rukstalis, Jepson, Patterson, & Lerman, 2005).

The preceding evidence suggests that the pattern of affective, cognitive, and behavioral changes that take place following a quit attempt among smokers with ADHD may be more pronounced compared with smokers without ADHD. As such, one strategy to improve smoking cessation outcomes in individuals with ADHD would be to provide treatments that can mitigate abstinence-induced decrements that are likely to occur. Stimulant medication, including methylphenidate-based and amphetamine-based products, are frontline treatments for ADHD in children, adolescents, and adults, and myriad studies have documented the efficacy and safety of these products for treating the core symptoms of ADHD, including inattention, impulsivity, and hyperactivity (Faraone & Buitelaar, 2010; Faraone & Glatt, 2010). Importantly, these medications have also been shown to significantly improve deficits in the kinds of processes that are acutely disrupted following smoking abstinence, including inhibitory control and attentional functioning, in individuals with and without ADHD (Brackenridge, McKenzie, Murray, & Quigley, 2011; Nandam et al., 2011; Tucha et al., 2006).

Lis-dexamfetamine dimesylate (LDX; Vyvanse®) is a pro-drug amphetamine product approved for use in the United States as a treatment for ADHD in both children and adults. Importantly, for the purposes of this study, LDX has been shown to significantly improve both core ADHD symptoms and aspects of executive functioning (Adler et al., 2008; Brown et al., 2011; Turgay et al., 2010). The primary objective of this randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind proof-of-concept study was to examine the safety and efficacy of LDX as an adjunct to transdermal NRT to facilitate smoking cessation in adult regular smokers with ADHD. Secondary objectives included the assessment of LDX on reducing ADHD symptoms in the context of a smoking quit attempt in adults with ADHD, as well as the ability of LDX to reduce abstinence-induced deficits in inhibitory control, attention, and negative affect.

Method

Participants

Participants for this study were 32 adult regular smokers with ADHD. To be eligible for the study, participants had to be between 18 and 50 years of age, express interest in quitting smoking, smoke at least 10 cigarettes/day, have an expired air CO level of at least 10 ppm, meet full Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed.; DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994) criteria for ADHD, and have an estimated IQ score of ≥80. Exclusionary criteria included the presence of any other psychiatric condition, use of illicit drugs (confirmed by urine drug screen), and for females of childbearing potential, pregnancy. Participants were also excluded if they were currently taking psychoactive medication, although those taking medication for ADHD (n = 4) were allowed to wash out of their medication for a period of 5 half-lives prior to the first postscreening visit. All participants provided informed consent for the study, which was approved by the local Institutional Review Board.

Study Design

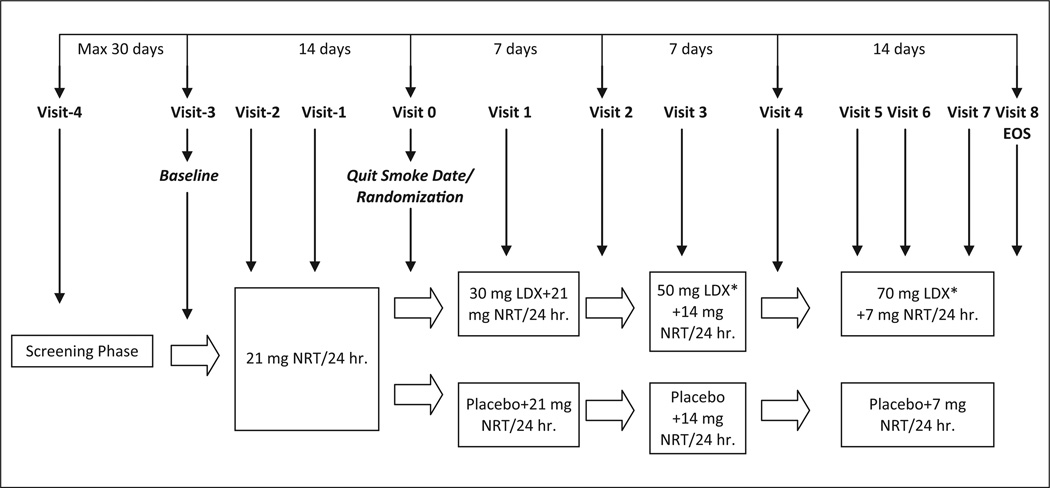

This was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel group trial. Figure 1 provides an overview of the study design. Participants were initially screened to verify diagnostic status and to ensure all inclusion and no exclusion criteria were met. Following screening, participants came to the clinic for 12 study visits as described in the following section.

Figure 1. Study schematic.

Note: EOS = End of study; NRT = nicotine replacement therapy; LDX = lis-dexamfetamine dimesylate.

Procedures and Study Visits

Screening visit

During screening, participants provided informed consent, and CO and vital signs were measured. A urine drug screen was also conducted. All participants completed the Conners’ Adult ADHD Rating Scale (CAARS; Conners, Erhardt, Sparrow, & staff, 1998) and were administered the Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test–Second Edition (Kaufman & Kaufman, 2004) to obtain an estimate of intellectual functioning. All participants, then, were administered the Conners’ Adult ADHD Interview for DSM-IV, which has been shown to have good psychometric properties for evaluating ADHD in adults (Epstein, Johnson, & Conners, 2000; Epstein & Kollins, 2006). Participants were also administered the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM (First, Gibbon, Williams, & Spitzer, 1997) to assess the presence of other significant psychopathology. Following the screening visit, participants were asked to begin a smoking diary, in which they recorded their daily number of cigarettes smoked. The diary was returned and reviewed at all subsequent study visits.

Baseline/NRT pretreatment initiation (Visit 3)

A baseline visit was scheduled to complete a range of other smoking-related variables, to establish a quit date (QD) and to initiate prequit treatment with NRT. Previous studies have suggested that initiating NRT prior to a quit attempt (i.e., while participants are still smoking) can reduce smoking prior to the QD and improve cessation outcomes after the QD, although this effect is likely to be small (Bullen et al., 2010; Lindson & Aveyard, 2011; Rose, Herskovic, Behm, & Westman, 2009). At this and all subsequent visits, participants completed a short form of the CAARS. At the baseline visit, all participants were given a supply of 21-mg transdermal NRT patches to use everyday for 10 days starting the next morning. Participants were given no explicit instructions about their smoking, and a QD was scheduled.

NRT pretreatment visits (Visits 2 and 1)

At these visits, participants completed the CAARS, and vital signs and CO were measured. Participants continued to receive transdermal NRT 21 mg once a day and reviewed any adverse events with a study clinician. In the event of untoward adverse events, participants were allowed to reduce the dose of NRT during this phase. These visits were scheduled 5 (±1) days apart.

Randomization/QD visit (Visit 0)

At this visit, participants completed the CAARS, and vital signs and CO were measured. Participants were also instructed that they should abstain from smoking starting the following morning. At this visit, participants were randomized into one of the two treatment groups—LDX and placebo. Participants in both groups were provided a supply of blinded study medication and provided instructions for initiating use, starting the following morning. The LDX initiated treatment on 30 mg LDX once daily. Participants were instructed to take the medication when they woke in the morning. Both groups continued to receive transdermal NRT 21 mg once a day.

Monitoring/dose titration visits (Visits 1–8)

Following randomization and QD, participants came for regular clinic visits approximately every 4 days. On all post-QD study visits, the smoking diary was reviewed, and participants completed the CAARS and were queried about any smoking since the last visit. Vital signs and CO were measured, and a urine drug screen was conducted.

At Study Visits 2 and 4, participants reviewed ADHD symptoms and any adverse events with a study clinician, who made a decision about whether to change the dose of study drug. Clinicians completed an investigator version of the CAARS. Dose titration could occur in 20-mg increments such that participants could be increased to 50 mg at Visit 2 and 70 mg at Visit 4. If intolerable adverse events were reported at any dose, participants could be down titrated to the next lowest dose at the next study visit. Following Study Visit 5, no study drug dose changes were made. At Study Visit 2, transdermal NRT was reduced to 14 mg once a day and further reduced to 7 mg once a day at Study Visit 4. At Study Visit 8, all experimental medication was collected and participants were debriefed and provided appropriate referral information.

Dependent Measures

The primary outcome measure for the study was the proportion of participants in each group who reported 4-week continuous smoking abstinence as verified by self-report and CO levels (≤4 ppm). A number of secondary outcomes were also examined, including self-reported cigarettes/day during the NRT pretreatment period and the post-QD period, and self- and clinician-rated ADHD symptoms as measured by the CAARS. Cognitive functioning and affect were assessed at the randomization visit (Visit 0), and all subsequent visits with a version of the Conners’ Continuous Performance Test (CPT; Conners, 2000) and the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS; Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988). Commission errors and reaction time variability from the CPT were examined as measures of inhibitory control and attentional functioning, respectively. The negative affect composite from the PANAS was used as an index of negative mood. Spontaneously reported adverse events were evaluated at each study visit.

Drugs and Administration

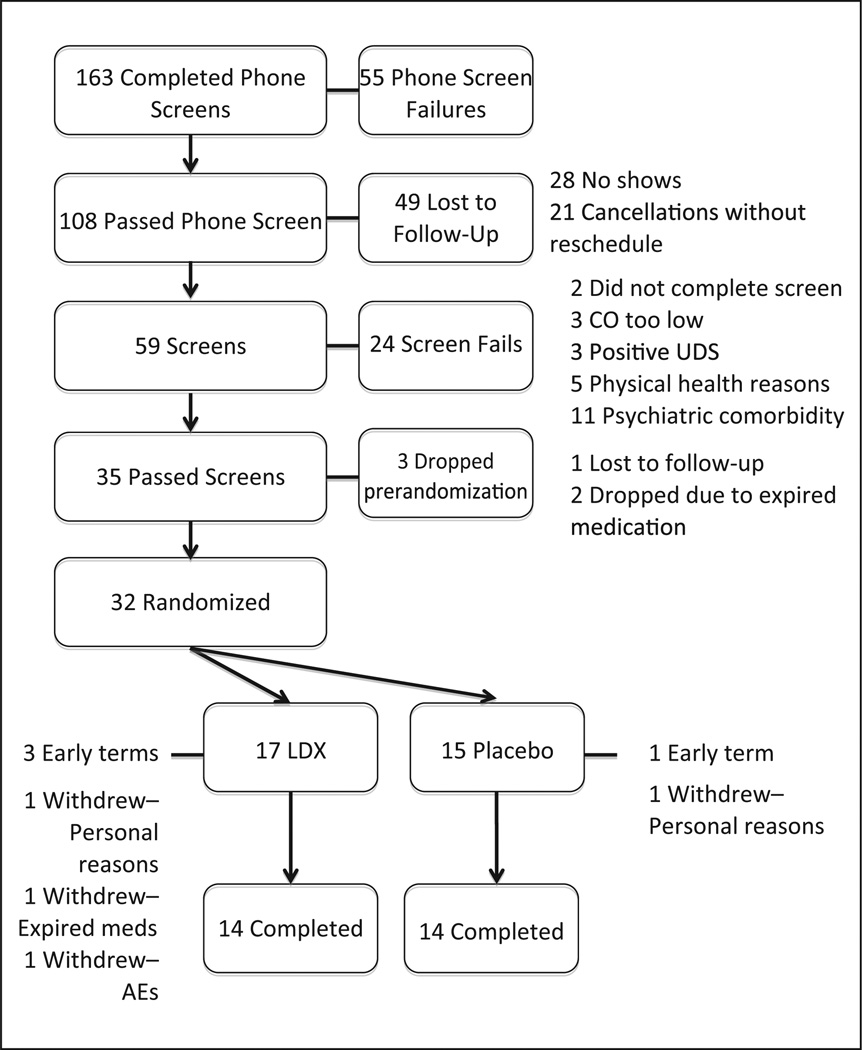

LDX and matching placebo capsules were provided by the sponsor of the study, Shire Pharmaceuticals (Wayne, Pennsylvania). Blinding, randomization, and drug dispensing was conducted by the local Investigational Drug Service. All drugs were prepared in opaque Size 3 capsules. LDX was provided in dose strengths of 30 mg, 50 mg, and 70 mg. Placebo capsules contained both filler (microcrystalline cellulose) and lubricant (magnesium stearate). The study was suspended for several months in 2010 when it was reported by the sponsor that some of the medication that had been provided had reached an expiration date. This affected two participants who were discontinued prior to randomization and one participant who was already started on medication and subsequently discontinued from the study (see Figure 2). Subsequent stability testing by the sponsor revealed no changes in medication composition, and all data from the participant who discontinued postrandomization were deemed useable.

Figure 2. Participant disposition throughout the study.

Note: LDX = lis-dexamfetamine dimesylate; UDS = Urine drug screen.

Data Analysis

For the measure of continuous abstinence, missing data were assumed to be indicative of a lapse. Data were analyzed using chi-square to compare proportions (for the primary outcome measure), paired t tests to evaluate the effects of prequit NRT on smoking behavior, Kaplan–Meier survival functions and log rank tests to assess rates of smoking abstinence across time, and mixed model ANOVA to assess ADHD symptoms, inhibitory control, attentional functioning, and negative affect, with group (LDX vs. treatment) as a between-participants variable and study visit as a within-participant variable.

Results

Figure 2 illustrates the disposition of participants throughout the study. A total of 32 participants were randomized to treatment—17 received LDX and 15 received placebo. There were no differences between randomized groups across any demographic or smoking-related variables (Table 1). Females (37.5% of the total sample) and ethnic minorities (21.8% of the sample) were well represented across groups.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

| Randomized group | LDX | Placebo | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ns | ||

| Male | 11 | 9 | |

| Female | 6 | 6 | |

| Race/ethnicity | ns | ||

| White | 14 | 11 | |

| Nonwhite | 3 | 4 | |

| ADHD subtype | ns | ||

| Inattentive | 5 | 7 | |

| Hyperactive-impulsive | 1 | 0 | |

| Combined | 11 | 8 | |

| Age in years (SD) | 29.6 (8.4) | 33.5 (9.1) | ns |

| KBIT total (SD) | 114.0 (9.4) | 115.9 (13.6) | ns |

| Cigarettes/day (SD) | 16.4 (6.2) | 16.2 (4.1) | ns |

| Screen CO in ppm (SD) | 27.0 (18.7) | 25.9 (17.8) | ns |

| Years regular smoker (SD) | 10.9 (8.8) | 12.6 (6.5) | ns |

| Age became regular smoker (SD) | 19.1 (5.1) | 18.9 (3.1) | ns |

| FTND total score (SD) | 4.2 (2.0) | 4.9 (1.5) | ns |

Note: FTND = Fagerstrom Test of Nicotine Dependence; LDX = lis-dexamfetamine dimesylate; KBIT = Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test.

Effects of pretreatment NRT

Across groups and prior to randomization, transdermal NRT resulted in significant reductions in smoking as measured by cigarettes/day and CO levels. Mean cigarettes per day between the screening visit and Study Visit 3, where NRT was initiated, was 14.9 (SD = 6.0), compared with an average of 9.8 (SD = 5.2) cigarettes per day at Study Visit 0 (t = 6.4, df = 30, p < .0001). CO levels similarly were significantly different between Study Visit 3 when NRT was initiated and Study Visit 0 (24.5 ppm [SD = 19.3] vs. 15.5 ppm [SD = 14.2], respectively; t = 4.3, df = 30, p < .001).

Treatment effects on smoking outcomes

There were no differences between the LDX and placebo groups on either CO-defined relapse rates or self-reported rates of smoking relapse. The primary outcome measure was the proportion of participants in each treatment group exhibiting sustained, 4-week smoking abstinence, defined as CO levels ≤ 4 ppm for each postquit study visit. Participants who dropped from the study for any reason were considered to have lapsed. In total, 3 of 15 smokers in the placebo group maintained continuous abstinence by this definition, compared with 5 of 17 smokers randomized to the LDX group. This difference was not statistically significant (χ2 = 0.376, df = 1, p = .54). Examining lapse as a survival function across study visits yielded similar results across the treatment groups. Log-rank tests for the equality of the survivor functions revealed no significant differences between the groups (χ2 = 0.47, df = 1, p = .50).

Similar analyses were conducted on self-reported smoking. Two participants in the placebo group reported continuous abstinence from the QD, compared with 0 participants in the LDX group (χ2 = 2.6, df = 1, p = .11). Similarly, survival analyses revealed no significant differences across groups (χ2 = 2.0, df = 1, p = .15).

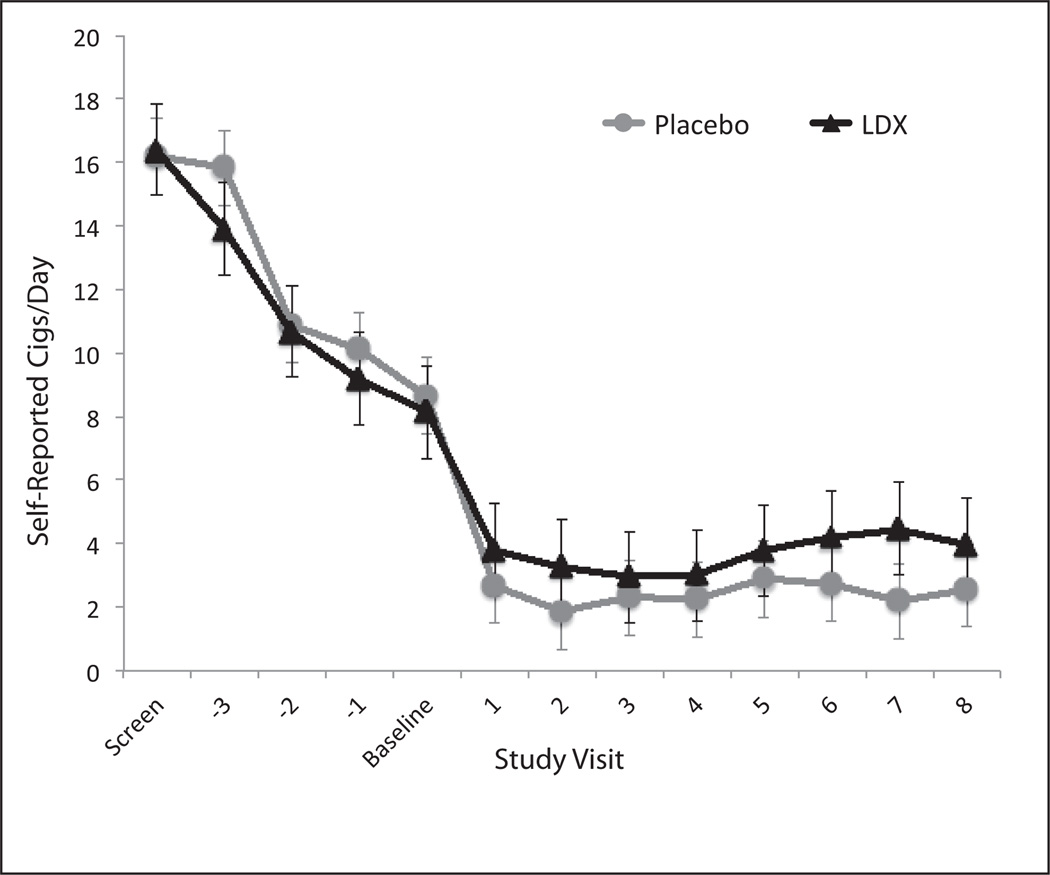

Both LDX and placebo resulted in significant reductions in self-reported cigarettes smoked per day (Fvisit = 15.8; df = 1, 28; p < .0001). There was no effect of treatment group or Treatment × Visit interaction for self-reported cigarettes per day. Figure 3 illustrates self-reported cigarettes per day across study visits as a function of treatment group.

Figure 3. Cigarettes per day as a function of study visit.

Note: LDX = lis-dexamfetamine dimesylate; SEM = Standard Error of the Mean. Error bars indicate +1 SEM.

Treatment effects on ADHD symptoms, inhibitory control, attentional functioning, and negative affect

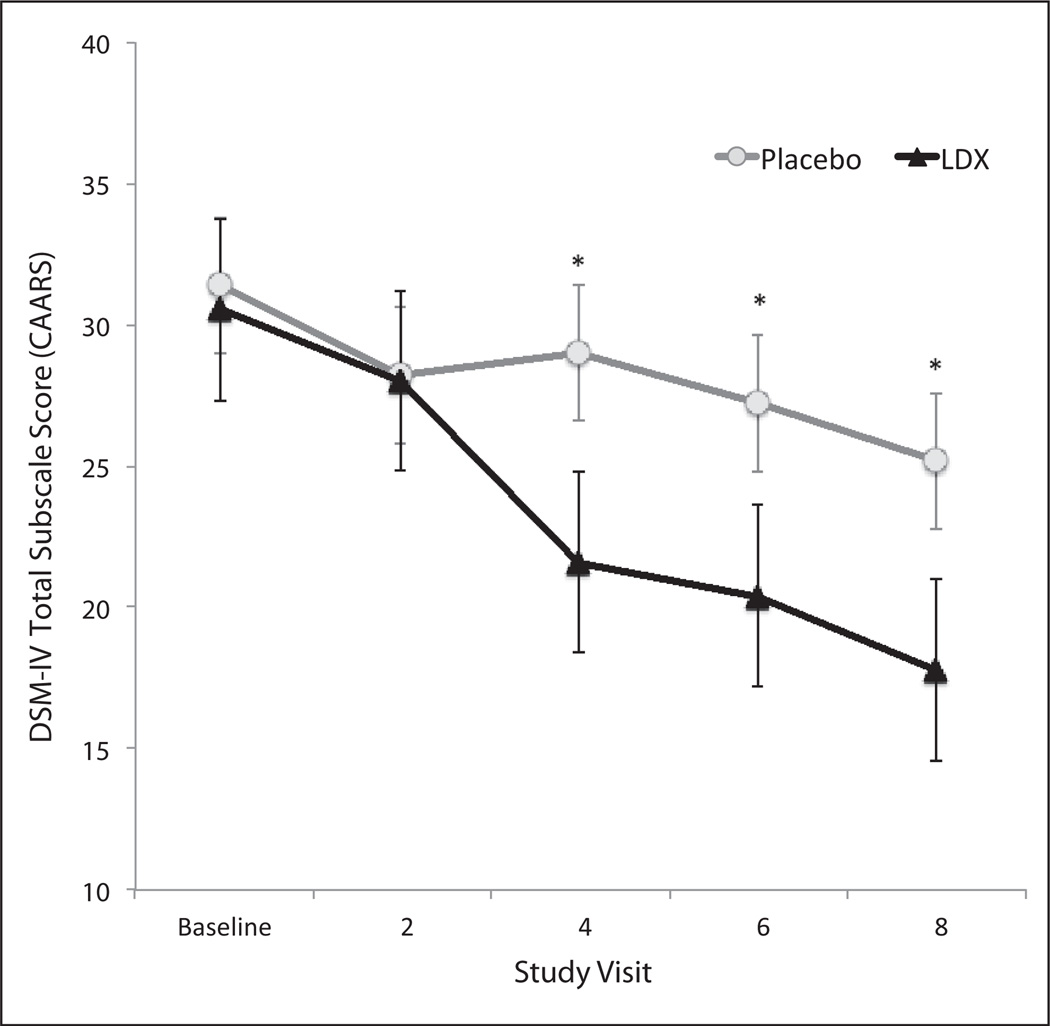

We examined the effects of LDX and placebo on clinician and self-ratings of ADHD symptoms using the DSM-IV Total subscale from the CAARS Observer and Self forms, respectively. There was a significant main effect of study visit (F = 10.02; df = 4, 26; p < .0001) and a significant Treatment × Visit interaction (F = 3.29; df = 4, 26; p = .01), indicating that following baseline, participants treated with LDX demonstrated significant reductions in their clinician-rated ADHD symptoms. Post hoc comparisons revealed differences between the placebo and LDX groups starting 2 weeks after the QD/baseline and persisting to the last study visit (Figure 4). Results from the self-report version of the CAARS yielded largely similar results with significant effects for treatment (F = 14.90; df = 4, 29; p < .0001) and Treatment × Visit (F = 5.14; df = 4, 29; p < .001). Post hoc comparisons demonstrated significant separation from placebo for the LDX group following 3 weeks of treatment.

Figure 4. Clinician ratings for the DSM-IV Total subscale of the CAARS as a function of study visit.

Note: LDX = lis-dexamfetamine dimesylate; DSM-IV = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed.); CAARS = Conners’ Adult ADHD Rating Scale.

*Groups were significantly different at p < .05.

Table 2 lists means of CPT commission errors, CPT reaction time standard error, and PANAS negative affect scores as a function of treatment and study visit. Except for a marginally significant main effect of study visit (p = .051) for reaction time standard error, there were no main effects of study treatment or study visit on these measures, nor were there any Treatment × Visit interactions. These findings indicate that participants in both treatment groups experienced minimal changes across these outcome measures from the randomization day through the end of treatment.

Table 2.

Means and Standard Deviations by Treatment and Study Visit for CPT Commission Errors and Reaction Time Standard Error and for PANAS Negative Affect Subscale

| Measure | Randomization/ Visit 0 |

Visit 1 | Visit 2 | Visit 3 | Visit 4 | Visit 5 | Visit 6 | Visit 7 | Visit 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPT commission errors | |||||||||

| LDX group | |||||||||

| M | 15.29 | 13.29 | 13.44 | 14.50 | 13.13 | 15.00 | 12.36 | 14.64 | 14.92 |

| SD | 10.58 | 9.64 | 9.14 | 8.91 | 8.33 | 7.67 | 10.43 | 9.20 | 10.80 |

| Placebo group | |||||||||

| M | 12.43 | 10.71 | 10.86 | 10.79 | 11.08 | 11.15 | 12.15 | 11.77 | 11.23 |

| SD | 9.37 | 8.62 | 8.70 | 7.52 | 9.29 | 9.20 | 8.12 | 6.98 | 9.77 |

| CPT reaction time standard error | |||||||||

| LDX group | |||||||||

| M | 5.37 | 5.52 | 5.42 | 4.97 | 4.83 | 5.54 | 4.64 | 5.29 | 4.86 |

| SD | 1.93 | 3.44 | 3.45 | 2.71 | 2.55 | 2.77 | 2.28 | 2.73 | 2.23 |

| Placebo group | |||||||||

| M | 4.61 | 4.68 | 5.05 | 5.01 | 4.79 | 5.15 | 4.97 | 5.73 | 5.08 |

| SD | 1.31 | 1.44 | 1.81 | 1.46 | 1.71 | 1.71 | 1.62 | 2.01 | 2.04 |

| PANAS negative affect | |||||||||

| LDX group | |||||||||

| M | 16.41 | 15.82 | 14.81 | 15.94 | 17.20 | 16.79 | 16.21 | 15.07 | NA* |

| SD | 4.90 | 4.91 | 4.13 | 4.96 | 5.49 | 5.82 | 5.56 | 5.98 | NA* |

| Placebo group | |||||||||

| M | 16.21 | 15.64 | 16.07 | 15.07 | 16.31 | 17.23 | 17.23 | 17.15 | NA* |

| SD | 6.19 | 5.02 | 6.45 | 6.78 | 7.74 | 7.10 | 6.81 | 8.20 | NA* |

Note: CPT = Continuous Performance Test; LDX = lis-dexamfetamine dimesylate; PANAS = Positive and Negative Affect Schedule. No significant effects were noted. See text for additional details.

The PANAS was not administered at the final visit.

Safety outcomes

There were no serious adverse events reported during the course of the study. One participant in the LDX group was discontinued from the study at Visit 4 because of marked anxiety that was determined to be severe and possibly related to study drug. A total of 15 of 17 (88%) participants in the LDX group reported adverse events (AEs) at any point during the study compared with 12 of 15 (80%) participants in the placebo group. This difference was not significant. Examining AEs following initiation of study drug (i.e., postbaseline) revealed that 13 of 17 (76%) participants in the LDX reported AEs versus 8 of 15 (53%) participants in the placebo group. This difference was not significant. Table 3 below lists the specific AEs and prevalence rates for the LDX and placebo groups during the prebaseline period (Study Visits 3, 2, 1, and 0) and postbaseline (Study Visits 1–8).

Table 3.

Prevalence of AEs During Prebaseline and Postbaseline Study Periods

| Prebaseline | Postbaseline | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adverse event | LDX (%) | Placebo (%) | LDX (%) | Placebo (%) |

| Anxiety | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5.9 | 6.7 |

| Restlessness | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 6.7 |

| Inability to concentrate | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 6.7 |

| Irritability | 0.0 | 0.0 | 17.6 | 6.7 |

| Panic attack | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 6.7 |

| Nightmares/dreams | 17.6 | 20.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Increased appetite | 5.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Decreased appetite | 0.0 | 6.7 | 35.3 | 0.0 |

| Excessive thirst | 5.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 6.7 |

| Chest tightness | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5.9 | 0.0 |

| Muscle twitches | 5.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Stomach pain | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5.9 | 0.0 |

| Arm pain | 5.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Teeth grinding/clenched Jaw | 0.0 | 0.0 | 11.8 | 0.0 |

| Heartburn | 0.0 | 6.7 | 0.0 | 6.7 |

| Fatigue/drowsiness | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 13.3 |

| Shaking hands/tremor | 0.0 | 6.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Insomnia | 5.9 | 6.7 | 5.9 | 20.0 |

| Headache | 23.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 13.3 |

| Sneezing | 5.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Cough | 5.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Nausea | 17.6 | 20.0 | 5.9 | 6.7 |

| Chills | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 6.7 |

| Itching | 5.9 | 6.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Skin irritation/burning | 5.9 | 6.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Dry mouth | 0.0 | 0.0 | 11.8 | 0.0 |

| Sore throat | 5.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Metallic taste | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 6.7 |

| Heartburn | 0.0 | 6.7 | 0.0 | 6.7 |

| Acne | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5.9 | 0.0 |

Note: LDX = lis-dexamfetamine dimesylate.

During the prebaseline period, there were three AEs that occurred in more than one study participant across both groups: increased nightmares/vivid dreams, headache, and nausea. Each of these AEs is likely related to the use of transdermal NRT. In the postbaseline period (i.e., after study drug was initiated), there were four AEs that occurred in more than one participant in the LDX group: irritability, decreased appetite, teeth grinding/clenched jaw, and dry mouth. There were three AEs that occurred in more than one participant in the placebo group: fatigue/drowsiness, insomnia, and headache. In general, most of these AEs were mild to moderate, and as noted, only one participant discontinued from the study due to AEs.

With respect to cardiovascular functioning, there were no differences between the LDX and placebo groups during the treatment period for systolic or diastolic blood pressure, or for heart rate (all Fs < 2.2, ps > .15).

Discussion

The present study is the first to our knowledge to systematically evaluate the effects of an amphetamine-based product for the treatment of ADHD to facilitate a smoking cessation attempt. Several findings were noteworthy. First, pretreatment with nicotine patch resulted in significant decreases in cigarettes smoked/day and CO levels prior to the identified QD in adult smokers with ADHD. Second, LDX had no effects compared with placebo on rates of continuous smoking abstinence. Third, participants in both groups demonstrated significant reductions in cigarettes smoked per day across the study. Fourth, LDX significantly reduced clinician-rated and self-reported symptoms of ADHD compared with placebo. Fifth, participants in this study, all of whom were treated with transdermal NRT, exhibited no changes in inhibitory control, attentional functioning, or negative affect following their QD, regardless of whether they received LDX or placebo. Finally, LDX was generally well tolerated with respect to self-reported adverse events and cardiovascular functioning.

Findings from this study are consistent with another published trial of osmotic-release methylphenidate in adult smokers with ADHD, which reported no effects of the stimulant drug on smoking cessation outcomes, but reductions in cigarettes smoked/day and significant drug-placebo differences in ADHD symptoms across the study (Winhusen et al., 2010). While our current proof-of-concept trial lacked statistical power to conclusively assess the effects of LDX on smoking cessation, treatment effects were virtually nonexistent and, combined with the previous study of osmotic-release methylphenidate, leads to the conclusion that stimulant medication does not likely facilitate smoking cessation in adult smokers with ADHD who are also treated with NRT.

Like the current study, the previous study of methylphenidate also treated participants with transdermal NRT, although in that study, NRT was initiated on the QD, rather than several weeks before as in the present trial. It is possible that beneficial effects of stimulant medication on smoking cessation were washed out by concurrent use of NRT. Indirect evidence for this hypothesis comes from our present findings that participants in neither group experienced disruptions in inhibitory control, attentional functioning, or negative affect, all of which are well characterized aspects of smoking withdrawal in those with and without ADHD (Gilbert et al., 1998, 2004; McClernon et al., 2008, 2011; Powell, Pickering, Dawkins, West, & Powell, 2004). While the effects of LDX and methylphenidate on smoking cessation in those with ADHD may be more pronounced in the absence of concurrent NRT, this would not conform to standard of care treatment for smoking cessation.

The present study had a number of strengths, including the use of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled design, rigorous diagnostic evaluation procedures, and assessment of smoking via a number of modalities (e.g., biological and self-report). However, our findings need to be considered alongside several important limitations. First, our sample size was quite small and this study can thus only be considered a pilot trial. Most of our findings did not even approach significance, however, suggesting that statistical power (i.e., sample size) was not a major factor in our findings. Moreover, our study findings are highly consistent with another much larger study, lending confidence to the idea that our results, although preliminary, are not spurious. Second, we did not collect systematic follow-up data on our sample after the end of treatment. It would have been useful to explore whether LDX-treated smokers showed a differential pattern of smoking compared with placebo-treated smokers following discontinuation of treatment. Third, the duration of our trial was short. It would have been useful to assess the impact of LDX on smoking-related outcomes over a longer duration of time. It is possible that group differences may have emerged across treatment conditions if the trial had been extended to 8 or 12 weeks, or even longer. Future studies would be well-served to explore these factors (i.e., larger sample size, longer studies, follow-up date) to more comprehensively assess the impact of stimulant drugs on smoking outcomes in individuals with ADHD.

In spite of these limitations, the present study adds to the relatively sparse literature on smoking cessation outcomes in adults with ADHD. Our findings suggest that among adult regular smokers with ADHD who are interested in quitting, LDX does not increase the probability of smoking cessation more than does placebo, but is associated with a significant overall reduction in the amount of cigarettes smoked and is effective for reducing ADHD symptoms. This finding is important, especially in light of laboratory studies that suggest stimulant drugs may increase rates of smoking in adults with and without ADHD (Rush et al., 2005; Stoops et al., 2011; Vansickel, Stoops, Glaser, Poole, & Rush, 2011). The effects of LDX and other stimulant drugs on smokers with ADHD who are not interested in quitting or who are not also taking NRT cannot be assessed from the current study but should be evaluated in clinical settings to help guide clinicians in optimally treating their patients with ADHD.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was funded by an Investigator-Initiated Study grant from Shire Pharmaceuticals to Dr. Kollins/Duke University. Study design and execution, data analysis and interpretation, and manuscript preparation were sole the responsibility of Dr. Kollins and the co-authors.

Biographies

Scott H. Kollins is an Associate Professor of Psychiatry and Director of the Duke ADHD Program at the Duke University School of Medicine. He has worked with adults, adolescents, and children with ADHD for over 15 years and has published over 100 papers in the areas of ADHD and psychopharmacology.

Joseph S. English is a Clinical Research Coordinators in the Duke ADHD Program.

Nilda Itchon-Ramos is a Clinical Research Coordinators in the Duke ADHD Program. Collectively, they have over 20 years of experience conducting clinical trials and laboratory studies of adults, adolescents, and children with ADHD.

Allan K. Chrisman is a board-certified child psychiatrists and have served as medical directors of the Duke ADHD Program. Dr. Chrisman has years of clinical and research experience treating adults, adolescents, and children with ADHD.

Rachel Dew is also a board-certified child psychiatrists and have served as medical directors of the Duke ADHD Program. Dr. Dew has years of clinical and research experience treating adults, adolescents, and children with ADHD.

Benjamin O’Brien served as a data technician for the compay and now works in as a software developer.

F. Joseph McClernon is an Associate Professor of Psychiatry at Duke University School of Medicine and a staff psychologist at the Durham VA. He has over 10 years of experience conducting human laboratory and clinical research with nicotine dependent individuals.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: During the period of the study, the following disclosures are noted. Dr. Kollins received research support and/or consulting fees fro, Shire Pharmaceuticals, Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, Addrenex Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer Inc., and NIDA/NIH. Dr. McClernon received research support from Philip Morris USA and NIDA/NIH. The other authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- Adler LA, Goodman DW, Kollins SH, Weisler RH, Krishnan S, Zhang Y, Biederman J. Double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the efficacy and safety of lisdexamfetamine dimesylate in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2008;69:1364–1373. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0903. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&;db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=19012818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Brackenridge R, McKenzie K, Murray GC, Quigley A. An examination of the effects of stimulant medication on response inhibition: A comparison between children with and without attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2011;32:2797–2804. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2011.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TE, Brams M, Gasior M, Adeyi B, Babcock T, Dirks BT. Clinical utility of ADHD symptom thresholds to assess normalization of executive function with lisdexamfetamine dimesylate treatment in adults. Current Medical Research & Opinion. 2011;27(Suppl. 2):23–33. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2011.605441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullen C, Howe C, Lin RB, Grigg M, Laugesen M, McRobbie H, Rodgers A. Pre-cessation nicotine replacement therapy: Pragmatic randomized trial. Addiction. 2010;105:1474–1483. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02989.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conners CK. The Conners Continuous Performance Test–Second Edition. Toronto, Canada: Multi-Health Systems; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Conners CK, Erhardt D, Sparrow E, staff MHS. The Conners Adult ADHD Rating Scale (CAARS) Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Multi-Health Systems; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Covey LS, Manubay J, Jiang H, Nortick M, Palumbo D. Smoking cessation and inattention or hyperactivity/impulsivity: A post hoc analysis. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2008;10:1717–1725. doi: 10.1080/14622200802443536. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&;db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=19023824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein JN, Johnson D, Conners CK. Conners’ adult ADHD diagnostic interview for DSM-IV. Toronto, Canada: Multi-Health Systems; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein JN, Kollins SH. Psychometric properties of an adult ADHD diagnostic interview. Journal of Attention Disorders. 2006;9:504–514. doi: 10.1177/1087054705283575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faraone SV, Buitelaar J. Comparing the efficacy of stimulants for ADHD in children and adolescents using meta-analysis. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010;19:353–364. doi: 10.1007/s00787-009-0054-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faraone SV, Glatt SJ. A comparison of the efficacy of medications for adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder using meta-analysis of effect sizes. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2010;71:754–763. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08m04902pur. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Gibbon M, Williams JBW, Spitzer RL. SCID Screen Patient Questionnaire–Extended version. North Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Fuemmeler BF, Kollins SH, McClernon FJ. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms predict nicotine dependence and progression to regular smoking from adolescence to young adulthood. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2007;32:1203–1213. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm051. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&;db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=17602186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert D, McClernon J, Rabinovich N, Sugai C, Plath L, Asgaard G, Botros N. Effects of quitting smoking on EEG activation and attention last for more than 31 days and are more severe with stress, dependence, DRD2 A1 allele, and depressive traits. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2004;6:249–267. doi: 10.1080/14622200410001676305. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&;db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=15203798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert DG, McClernon FJ, Rabinovich NE, Plath LC, Jensen RA, Meliska CJ. Effects of smoking abstinence on mood and craving in men: Influences of negative-affect-related personality traits, habitual nicotine intake and repeated measurements. Personality and Individual Differences. 1998;25:399–423. [Google Scholar]

- Glass K, Flory K. Why does ADHD confer risk for cigarette smoking? A review of psychosocial mechanisms. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2010;13:291–313. doi: 10.1007/s10567-010-0070-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heishman SJ, Taylor RC, Henningfield JE. Nicotine and smoking: A review of effects on human performance. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1994;2:345. [Google Scholar]

- Humfleet GL, Prochaska JJ, Mengis M, Cullen J, Munoz R, Reus V, Hall SM. Preliminary evidence of the association between the history of childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and smoking treatment failure. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2005;7:453–460. doi: 10.1080/14622200500125310. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&;db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=16085513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman AS, Kaufman NL. Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test, Second Edition (KBIT-II) Circle Pines, MN: AGS Publishing; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Adler L, Barkley R, Biederman J, Conners CK, Demler O, Zaslavsky AM. The prevalence and correlates of adult ADHD in the United States: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:716–723. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.4.716. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&;db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=16585449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kollins SH, McClernon FJ, Epstein JN. Effects of smoking abstinence on reaction time variability in smokers with and without ADHD: An ex-Gaussian analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;100:169–172. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kollins SH, McClernon FJ, Fuemmeler BF. Association between smoking and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms in a population-based sample of young adults. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:1142–1147. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.10.1142. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&;db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=16203959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert NM, Hartsough CS. Prospective study of tobacco smoking and substance dependencies among samples of ADHD and non-ADHD participants. Journal of Learning Disabilities. 1998;31:533–544. doi: 10.1177/002221949803100603. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9813951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindson N, Aveyard P. An updated meta-analysis of nicotine preloading for smoking cessation: Investigating mediators of the effect. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2011;214:579–592. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-2069-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClernon FJ, Kollins SH, Lutz AM, Fitzgerald DP, Murray DW, Redman C, Rose JE. Effects of smoking abstinence on adult smokers with and without attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Results of a preliminary study. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008;197:95–105. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-1009-3. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&;db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=18038223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClernon FJ, Van Voorhees EE, English J, Hallyburton M, Holdaway A, Kollins SH. Smoking withdrawal symptoms are more severe among smokers with ADHD and independent of ADHD symptom change: Results from a 12-day contingency-managed abstinence trial. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2011;13:784–792. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milberger S, Biederman J, Faraone SV, Chen L, Jones J. ADHD is associated with early initiation of cigarette smoking in children and adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:37–44. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199701000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milberger S, Biederman J, Faraone SV, Wilens T, Chu MP. Associations between ADHD and psychoactive substance use disorders. Findings from a longitudinal study of high-risk siblings of ADHD children. 1997;6:318–329. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&;db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=9398930. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina BS, Pelham WE., Jr Childhood predictors of adolescent substance use in a longitudinal study of children with ADHD. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:497–507. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.112.3.497. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&;db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=12943028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nandam LS, Hester R, Wagner J, Cummins TD, Garner K, Dean AJ, Bellgrove MA. Methylphenidate but not atomoxetine or citalopram modulates inhibitory control and response time variability. Biological Psychiatry. 2011;69:902–904. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomerleau OF, Downey KK, Stelson FW, Pomerleau CS. Cigarette smoking in adult patients diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1995;7:373–378. doi: 10.1016/0899-3289(95)90030-6. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&;db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=8749796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell JH, Pickering AD, Dawkins L, West R, Powell JF. Cognitive and psychological correlates of smoking abstinence, and predictors of successful cessation. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29:1407–1426. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.06.006. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&;db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=15345273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohde P, Kahler CW, Lewinsohn PM, Brown RA. Psychiatric disorders, familial factors, and cigarette smoking: II. Associations with progression to daily smoking. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2004;6:119–132. doi: 10.1080/14622200310001656948. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&;db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=14982696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose JE, Herskovic JE, Behm FM, Westman EC. Precessation treatment with nicotine patch significantly increases abstinence rates relative to conventional treatment. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2009;11:1067–1075. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rukstalis M, Jepson C, Patterson F, Lerman C. Increases in hyperactive-impulsive symptoms predict relapse among smokers in nicotine replacement therapy. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2005;28:297–304. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush CR, Higgins ST, Vansickel AR, Stoops WW, Lile JA, Glaser PE. Methylphenidate increases cigarette smoking. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;181:781–789. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0021-8. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&;db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=15983792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoops WW, Poole MM, Vansickel AR, Hays KA, Glaser PE, Rush CR. Methylphenidate increases choice of cigarettes over money. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2011;13:29–33. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucha O, Prell S, Mecklinger L, Bormann-Kischkel C, Kubber S, Linder M, Lange KW. Effects of methylphenidate on multiple components of attention in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;185:315–326. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0318-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turgay A, Ginsberg L, Sarkis E, Jain R, Adeyi B, Gao J, Findling RL. Executive function deficits in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and improvement with lisdexamfetamine dimesylate in an open-label study. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 2010;20:503–511. doi: 10.1089/cap.2009.0110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vansickel AR, Stoops WW, Glaser PE, Poole MM, Rush CR. Methylphenidate increases cigarette smoking in participants with ADHD. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2011;218:381–390. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2328-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54:1063–1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&;db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=3397865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilens TE, Vitulano M, Upadhyaya H, Adamson J, Sawtelle R, Utzinger L, Biederman J. Cigarette smoking associated with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Pediatrics. 2008;153:414–419. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.04.030. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&;db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=18534619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winhusen TM, Somoza EC, Brigham GS, Liu DS, Green CA, Covey LS, Dorer EM. Impact of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) treatment on smoking cessation intervention in ADHD smokers: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2010;71:1680–1688. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05089gry. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]