Abstract

Nkx2.2 encodes a homeodomain transcription factor required for the correct specification and/or differentiation of cells in the pancreas, intestine and CNS. To follow the fate of cells deleted for Nkx2.2 within these tissues, we generated Nkx2.2:lacZ knockin mice using a recombination-mediated cassette exchange (RMCE) approach. Expression analysis of lacZ and/or β-galactosidase in Nkx2.2lacZ/+ heterozygote embryos and adults demonstrates that lacZ faithfully recapitulates endogenous Nkx2.2 expression. Furthermore, the Nkx2.2lacZlacZ homozygous embryos display phenotypes indistinguishable from the previously characterized Nkx2.2−/− strain. LacZ expression analyses in the Nkx2.2lacZ/lacZ homozygous embryos indicate that Nkx2.2-expressing progenitor cells within the pancreas are generated in their normal numbers and are not mislocalized within the pancreatic ductal epithelium or developing islets. In the central nervous system of Nkx2.2lacZ/acZ embryos, LacZ-expressing cells within the ventral P3 progenitor domain display different migration properties depending on the developmental stage and their respective differentiation potential.

Keywords: Pancreas development, beta cells, ghrelin cells, transcriptional regulation, islet cell lineage

Introduction

Nkx2.2 is a member of the vertebrate homeodomain transcription factor gene family homologous to the Drosophila NK2/ventral nervous system defective (vnd) gene (Kim and Nirenberg, 1989; Price et al., 1992). Nkx2.2 is expressed in the central nervous system (CNS), pancreas and intestine, where it plays essential roles in the specification of progenitor cell identity and regulation of cell fate decisions (Briscoe et al., 1999; Desai et al., 2008; Sussel et al., 1998). In the developing pancreas, Nkx2.2 protein expression is initiated with Pancreatic and duodenal homeobox (Pdx1) and Pancreas transcription factor 1 subunit alpha (Ptf1a) in the dorsal and ventral pancreatic epithelium at e8.75 and e9.5, respectively (Jorgensen et al., 2007). After e11.5, Nkx2.2 expression is maintained throughout the epithelium, but is produced at varied intensities, with obvious subsets of low and high expressing cells emerging during the secondary transition. The high expressing cells predominantly correlate with the hormone-producing populations. Nkx2.2 is also found in a large number of endocrine progenitors (Jorgensen et al., 2007), where it has been proposed to modulate the expression of Neurogenin 3 (Ngn3) (Anderson et al., 2009b). In the adult pancreas, Nkx2.2 expression is maintained in alpha, beta and pancreatic polypeptide (PP) cells but not in delta cells (Sussel et al., 1998). Nkx2.2 cannot be detected within the exocrine compartment at any point during development or in the adult.

In the developing CNS, Nkx2.2 is expressed in specific subsets of neurons along the anterior-posterior axis. Nkx2.2 has been extensively studied in the ventral spinal cord where it is induced by high levels of Sonic hedgehog (Shh) to specify V3 interneurons and repress motor neuron differentiation (Briscoe et al., 2000; Ericson et al., 1997). After e12.5, a second wave of Nkx2.2-expressing progenitor cells gives rise to oligodendrocytes (Qi et al., 2001; Zhou et al., 2001). In the hindbrain, Nkx2.2 is expressed in the ventral precursor cells that first give rise to the visceral motor neurons (vMNs) and then to serotonergic neurons (Briscoe et al., 1999; Pattyn et al., 2003a). In the intestine, Nkx2.2 can be detected in a subset of Ngn3-expressing cells, endocrine progenitor cells located in the crypt compartment (Desai et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2009b) and is expressed in a large number of enteroendocrine-producing cell populations, including the glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) - expressing L cells, serotonin, somatostatin and cholecystokinin (CCK) cells (Desai et al., 2008).

Interestingly, in each of the three tissues expressing Nkx2.2, the loss of Nkx2.2 induces cell fate conversions. In the pancreas of Nkx2.2−/− (null) mice, insulin-producing beta cells are completely absent and glucagon-producing alpha cells are reduced (Prado et al., 2004; Sussel et al., 1998). Similarly, in the intestine of mice lacking Nkx2.2, many different hormone-producing populations are reduced, including those expressing CCK, GLP-1, gastrin and serotonin (Desai et al., 2008). In both the pancreas and intestine, the loss of hormone-producing cells is compensated by the upregulation of another endocrine population, the ghrelin-expressing cells (Desai et al., 2008; Prado et al., 2004). In the CNS, Nkx2.2−/− mice have reduced numbers of V3 interneurons, oligodendrocytes, and serotonergic neuronal populations. Analogous to the pancreas and gut, there is a concomitant upregulation of the dorsally located motor neuron domains in the spinal cord (Briscoe et al., 1999; Pattyn et al., 2003b). Although it is apparent that Nkx2.2 is essential for the specification of specific cell types in each tissue, it is not clear whether the cell conversions result from the loss of specific Nkx2.2-producing progenitor populations, a failure of Nkx2.2-expressing cells to migrate or proliferate appropriately, and/or the redirection of Nkx2.2-expressing cells to alternative cell fates.

In this study, we describe the generation and characterization of an Nkx2.2:lacZ knock-in allele generated by Recombination-Mediated Cassette Exchange (RMCE) (Chen et al., 2011; Long et al., 2004). Analyses of the Nkx2.2lacZ/+ heterozygous mice demonstrate the faithful recapitulation of lacZ and beta-galactosidase in the endogenous Nkx2.2 expression domains and Nkx2.2lacZ/lacZ homozygous mice phenocopy the Nkx2.2−/− mice (Prado et al., 2004; Sussel et al., 1998). Furthermore, the ability to track lacZ-expressing cells in the absence of Nkx2.2 suggest that the majority of Nkx2.2-derived populations in the pancreas and CNS are maintained in the absence of functional Nkx2.2 protein and appear to be respecified into alternative cell fates, as previously hypothesized (Briscoe et al., 1999; Prado et al., 2004). However, these studies also revealed that a population of progenitors in the spinal cord fails to migrate from the ventricular zone after e12.5 and thus may not become respecified. The detection of beta-galactosidase expression in the Nkx2.2lacZ/+ mice has also allowed us to monitor the fate of Nkx2.2-expressing cells in the absence of Pdx1 or Ngn3. In each case, Nkx2.2:lacZ-expressing cells are present, indicating that Pdx1 and Ngn3 are not required to initiate or maintain Nkx2.2 expression.

Results

We generated the Nkx2.2:lacZ allele using a two step RMCE approach (Chen et al., 2011). The first step involved the generation of an Nkx2.2 acceptor allele using standard homologous recombination methods. The Nkx2.2 acceptor allele (Nkx2.2LCA) was engineered in TL-1 ES cells (Labosky et al., 1994) and has a 5.115 kb region of the Nkx2.2 genomic region, including both coding exons, replaced with a pUΔTK-EM7kan cassette that is flanked with heterologous lox sites (Figure 1A and materials and methods). Electroporated ES cells were screened by southern analysis using external 5′ and 3′ probes to identify 8 correctly targeted Nkx2.2LCA ES cells (Figure 1A,C; data not shown). To generate the Nkx2.2:lacZ cassette, the full-length lacZ gene containing a N-terminal nuclear localization signal (nls) (Picard and Yamamoto, 1987) was cloned in frame with the Nkx2.2 ATG, replacing most of the Nkx2.2 two coding exons and the intervening intron (Figure 1B, materials and methods). RMCE of the Nkx2.2:lacZ cassette was performed in ES cell clones 2G6 and 4E9 with an exchange efficiency of 47% and 41%, respectively. RMCE clones were screened by PCR (Figure 1D). One clone from each correctly recombined ES cell line was injected into blastocysts; mice generated from clone 4E9/4D2 were validated by PCR and selected for further analysis (Figure 1E; 53004 and 53005).

Figure 1. Generation of the Nkx2.2LCA ES cells and Nkx2.2:lacZ knockin allele.

(a) Schematic of the strategy used to create the Nkx2.2LCA allele in ES cells. P1 and P2 indicate the location of the 5′ and 3′ external southern probes. The blue boxes labeled “1” and “2” represent the two Nkx2.2 coding exons. “SA” indicates the short arm of homology and “LA” indicates the long arm of homology. (b) Schematic of the Nkx2.2:lacZ cassette and Nkx2.2:lacZ knockin allele. The nls-lacZ gene was cloned in frame at the Nkx2.2 ATG codon and just upstream of the stop codon, effectively replacing the Nkx2.2 coding sequence and intervening intron. The Nkx2.2:lacZ cassette replaces the Nkx2.2LCA allele using RMCE. The Flpe-recombinase is used to remove the FRT-flanked hygromycin cassette. (c) Representative southern blot analysis of targeted ES cells using the 3′ (P2) probe. ES cell DNA was digested with Kpn1. The Nkx2.2 wild type allele is 17,026 bp and Nkx2.2LCA is 15,504 bp. TL1 is the parent ES cell line; the remaining lanes show correctly targeted ES cells. The wild type band from the TL1 parental ES cells migrates at a slightly faster rate due to a difference in DNA abundance and salt concentration in ES cell DNA preparation. (d) Representative PCR amplification results of Nkx2.2LCA ES cells containing Cre-mediated recombination of the Nkx2.2:nls-lacZ allele. For each RMCE ES cell clone, two sets of primers were used. Lanes labeled “a” indicate a PCR reaction for the targeted Nkx2.2:lacZ allele using primers 1 and 2 (606 bp) and lanes labeled “b” indicate the reaction using primers 3 and 4 (556 bp for the Nkx2.2:nlslacZ allele and 479 bp for the Nkx2.2 wild type allele). (e) Representative PCR amplification results of Nkx2.2:lacZ chimeric mice and one of the correctly targeted ES cell clones (4E9/4D2). Lanes are labeled “a” and “b” as above. Chimera #53004 and 53005 were correctly targeted.

Nkx2.2 is expressed in the developing CNS, intestine and pancreas (Briscoe et al., 1999; Desai et al., 2008; Jorgensen et al., 2007; Sussel et al., 1998). To confirm that lacZ expression in the Nkx2.2lacZ/+ mice accurately recapitulated endogenous Nkx2.2 expression, we characterized lacZ expression and/or beta-galactosidase activity in Nkx2.2lacZ/+ heterozygous embryos throughout embryogenesis (Figure 2). Critical to this analysis, heterozygous Nkx2.2+/− or Nkx2.2lacZ/+ embryos express Nkx2.2 mRNA transcript at levels comparable to Nkx2.2 wild type embryos and appear phenotypically wild type (Supplemental figure 1e and 4). Whole mount X-gal staining of e10.5 and e12.5 Nkx2.2lacZ/+ embryos demonstrated LacZ expression along the entire anterior-posterior axis of the CNS and in the pancreatic bud region, as expected (Figure 2a and 2b) (Jorgensen et al., 2007; Shimamura et al., 1995). At both stages, X-gal staining is apparent in ventral regions of the forebrain, midbrain, hindbrain, and spinal cord, while lacZ expression is not detected in control wild type littermates (Supplemental figure 1a and b). Sections at comparative levels from e12.5 embryos demonstrate that LacZ expression corresponds to endogenous Nkx2.2 mRNA expression in the CNS and dorsal and ventral pancreatic buds (compare Figure 2c to 2d). A ventral view of whole e12.5 brain shows concentrated X-gal staining along the ventral midline, with staining spreading laterally within Nkx2.2-expressing cells of the anterior subventricular zone that ultimately migrate rostrally to give rise to oligodendrocyte populations in the olfactory bulb (Figure 2e) (Aguirre and Gallo, 2004; Tonchev et al., 2006). The dorsal view of the embryo shows two pronounced stripes of expression in the spinal cord flanking the midline, which is also characteristic of endogenous Nkx2.2 expression (Figure 2f). In the e17.5 pancreas, X-gal staining can be detected strongly throughout the epithelial ductal tree and becomes downregulated in the peripheral cells that give rise to the exocrine tissue (Figure 2g). Scattered X-gal staining can be detected throughout the Nkx2.2lacZ/+ intestine, representing Nkx2.2-expressing enteroendocrine cells (Figure 2h) (Desai et al., 2008). Intestine from Nkx2.2 wild type embryos display only diffuse X-gal staining that could arise from endogenous beta-galactosidase activity (Supplemental figure 1c). Transverse sections of e9.5 and e10.5 whole mount embryos reveal LacZ expression in the CNS and the dorsal and ventral pancreatic buds at 10.5 (Figure 2i, Supplemental figure 1d). Strong X-gal staining can also be detected in the P3 region of the ventral spinal cord, adjacent to the floorplate, as previously described (Briscoe et al., 2000; Briscoe et al., 1999) (Figure 1i′,I‴, Supplemental figure 1e′,e‴). X-gal staining on sections of embryonic and adult pancreata confirms extensive expression of LacZ throughout the pancreatic epithelium at e12.5 and restricted expression of LacZ in the adult pancreatic islet (Figure 2j and 2k). With the exception of rare X-gal signal observed in isolated centroacinar cells and juxta-ductal cells, X-gal staining is predominantly excluded from the acinar tissue, as expected (Figure 2k, Supplemental figure 1f, Supplemental figure 2) (Sussel et al., 1998).

Figure 2. The Nkx2.2:lacZ allele reproduces endogenous Nkx2.2 expression pattern.

(a,b) X-gal staining in whole mount Nkx2.2lacZ/+ embryos. The dotted line indicates the level of the section shown in c. (c) A transverse section through an Nkx2.2lacZ/+ e12.5 embryo stained with X-gal. The level of the section in indicated by the dotted line in b. (d) An Nkx2.2 mRNA in situ performed on a section from an e12.5 wild type embryo. (e,f) Ventral (e) and dorsal (f) views showing X-gal staining of whole mount Nkx2.2lacZ/+ brain indicates LacZ expression in the dorsal and ventral CNS. (g) X-gal staining of dissected e17.5 pancreas. (h) X-gal staining of dissected e17.5 intestine. (i) Transverse section at e10.5 indicates Nkx2.2:lacZ expression in the CNS and the dorsal and ventral pancreas in e10.5 embryos. Boxed regions are magnified in i′-i‴. (j) A section through an e12.5 pancreas; X-gal staining can be detected throughout the pancreatic epithelium. (k) Section through an adult pancreas;X-gal staining is restricted to pancreatic islet in adults. CNS, central nervous system; FB, forebrain; MB, midbrain; HB, hindbrain; SC, spinal cord; DP, dorsal pancreas; VP, ventral pancreas.

To confirm appropriate pancreatic Nkx2.2:lacZ expression at the cellular level, we performed co-immunostaining with anti-beta-galactosidase antibody in combination with pancreatic cell lineage markers in Nkx2.2lacZ/+ embryos or adult animals. At e12.5, beta-galactosidase expression can be detected throughout the pancreatic epithelium, extensively overlapping with E-Cadherin, Pdx1 and Ptf1a expressing cells (Figure 3a,3b and Supplemental figure 3). Similar to endogenous Nkx2.2 protein expression, there appears to be populations of low and high expressing beta-galactosidase-expressing cells in the Nkx2.2 expression domain, with the high expressing cells predominantly representing a Pdx1-negative, glucagon-positive population (Figure 3b–3f; arrows; Supplemental figure 3). This would suggest that Nkx2.2 becomes upregulated in the cells that are transitioning from a multipotent progenitor state to a hormone-producing endocrine cell. At e15.5, beta-galactosidase is extensively co-expressed with Ngn3 in the endocrine progenitor cells and co-expressed with insulin, glucagon and ghrelin in the differentiating endocrine populations. By this stage, beta-galactosidase expression is excluded from Ptf1a-expressing exocrine cells (Figure 3g–3k). At e18.5, beta-galactosidase continues to be co-expressed with insulin, glucagon, ghrelin and PP, but is also unexpectedly found in a small number of somatostatin-expressing delta cells (Figure 3l–3p). Since endogenous Nkx2.2 is not normally co-expressed with somatostatin and does not appear to function in the delta cell population (Sussel et al., 1998), the observed co-expression may be due to either the perdurance of beta-galactosidase protein or disruption of a delta cell-specific repressor element in the Nkx2.2:LacZ allele. Consistent with the former hypothesis, the co-expression LacZ with somatostatin is transient and beta-galactosidase is excluded from the somatostatin-expressing delta cells in the adult islet (Figure 3t). Beta-galactosidase can be detected in alpha, beta, PP and the majority of Pdx1-expressing cells in the adult islet (Figure 3q–3s,3u).

Figure 3. Nkx2.2:lacZ spatio-temporal expression analysis in Nkx2.2lacZ/+ embryos.

(a–f) At e12.5 adjacent sections in the pancreatic epithelium show beta-galactosidase staining in the pancreatic domain marked by E-cadherin and Pdx1. (b–f) Beta-galactosidase is extensively co-expressed with Pdx1, except for a population of Nkx2.2:LacZhigh expressing cells that co-stain with glucagon. The small insets in b and c highlight the fields magnified in d and e respectively. (g–k) At e15.5, beta-galactosidase is co-expressed with insulin-, glucagon- and ghrelin. By this stage the exocrine lineage and LacZ-expressing cells are mutually exclusive. (k) Nkx2.2:lacZ is also expressed in Ngn3-expressing endocrine progenitor cells. Filled arrowhead indicates Ngn3+/beta-galactosidase+ and empty arrowhead indicates Ngn3+/beta-galactosidase−. (l–p) At e18.5, beta-galactosidase is expressed in most of the endocrine cell populations within the forming islet. (q–u) In adult islets, beta-galactosidase is restricted to α, β and PP cells and in the majority of Pdx1-expressing cells. l–u are confocal images. DAPI staining was used to visualize the nuclei in a,f,g,h,I,k,l,o,p, and t. Magnification 20X otherwise indicated. Insets show higher magnification. All staining was performed in Nkx2.2lacZ/+ embryos and animals.

We have previously shown that the Nkx2.2−/− mice display altered endocrine cell ratios: insulin-producing beta cells are undetectable at all time points and there is a reduction in the glucagon-producing alpha and pancreatic polypeptide-producing PP cell populations. In the place of these cell types, there is a corresponding increase in the ghrelin-producing epsilon cells (Prado et al., 2004; Sussel et al., 1998). Both Nkx2.2lacZ/lacZ and Nkx2.2lacZ/− mice display an identical phenotype to the Nkx2.2−/− mice confirming that insertion of the lacZ gene into the Nkx2.2 genomic locus creates a null allele (Figure 4 and Supplemental Figure 4). To determine the fate of the Nkx2.2-producing cell population in the absence of functional Nkx2.2 protein, we assessed beta-galactosidase expression in the Nkx2.2lacZ/lacZ mice. Although there are fewer alpha and PP cells at all stages examined, beta-galactosidase is co-expressed with glucagon and PP in the cells that do form (Figure 4a,b,g,h), suggesting that although these cells are capable of expressing Nkx2.2, their formation is independent of Nkx2.2 function. In addition, the ghrelin-expressing population, which now represents the majority of cells in islets lacking Nkx2.2, also express beta-galactosidase (Figure 4f). This would indicate that the mutant ghrelin-producing population is derived from a respecified Nkx2.2-expressing progenitor cell.

Figure 4. Number and location of Nkx2.2:lacZ expressing cells in the developing pancreas is indistinguishable between Nkx2.2lacZ/lacZand Nkx2.2lacZ/+ littermates.

(a)Immunofluorescence analysis beta-galactosidase in the Nkx2.2lacZ/lacZembryos shows that LacZ is expressed in glucagon-producing cells at e10.5. (b–e) At e12.5 in the Nkx2.2lacZ/lacZembryos, beta-galactosidase is co-expressed with Pdx1 within the pancreatic epithelium, with the exception of a population of beta-galactosidasehigh expressing cells that co-express with glucagon, as seen in Nkx2.2lacZ/+. (f–j) By e15.5, beta-galactosidase is co-expressed with Ngn3 in the ductal epithelium and the endocrine hormones; beta-galactosidase is not detected in the amylase-expressing exocrine tissue. (k) Quantification of the hormone producing cells co-stained with beta-galactosidase in e15.5 Nkx2.2lacZ/+ and Nkx2.2lacZ/lacZ embryos. (l) The number of beta-galactosidase positive cells is unchanged in e15.5 Nkx2.2lacZ/lacZcompared to Nkx2.2lacZ/+. White and black bars represent Nkx2.2lacZ/+ and Nkx2.2lacZ/lacZ respectively. * p≤0.05. Magnification 20X. Insets show higher magnification. DAPI staining was used to visualize the nuclei in a,c,f,h, and i.

Interestingly, in Nkx2.2lacZ/lacZ pancreas we continue to observe similar ratios of high and low Nkx2.2/beta-galactosidase-expressing cells, suggesting that Nkx2.2 expression may not be autoregulated as previously suggested (Watada et al., 2003). In addition, at early developmental stages we do not detect alterations in the total numbers of lacZ-expressing cells or their spatial or cellular distribution within the pancreatic epithelium (Figure 4a–d). Beta-galactosidase is also still extensively co-expressed with E-cadherin and Pdx1, although Pdx1 is expressed at lower levels per cell, as previously reported (Figure 3b,d vs. 4d; 4e, l; (Prado et al., 2004; Sussel et al., 1998). Furthermore, the numbers of beta-galactosidase and Ngn3-co-expressing endocrine progenitor cells are equivalent to those present in wild type mice, although the amount of Ngn3 expressed per cell is reduced as previously described (Figure 4e; (Anderson et al., 2009b). These findings suggest that the altered endocrine cell ratios caused by the absence of Nkx2.2 is not due to the mislocalization or loss of the Nkx2.2-expressing progenitor cell population. Quantification of the total number of each endocrine hormone-producing population at e18.5 confirms that the Nkx2.2lacZ/lacZ mice are phenotypically identical to mice homozygous for the Nkx2.2−/− allele and also demonstrates that the altered islet cell ratios is not caused by a loss of an Nkx2.2-expressing population (Figure 4k and l; Supplemental figure2c-d).

Comparison of gene expression levels between Nkx2.2LacZ/+ and Nkx2.2LacZ/LacZ were consistent with the cell quantification analysis (Figure 5). There was no difference in the amount of lacZ mRNA expression between the heterozygous and homozygous mutant pancreas at all stages of development, confirming that that loss of Nkx2.2 does not affect the regulation of the Nkx2.2 locus (Figure 5a). In agreement with our previous studies of the Nkx2.2−/− allele, the Nkx2.2lacZ/lacZ pancreas has reduced Ngn3 expression throughout the secondary transition (Figure 5b) (Anderson et al., 2009b). The changes in hormone gene expression are also consistent with the observed altered endocrine cell ratios (Figure 5c).

Figure 5. mRNA expression of endocrine markers is altered in Nkx2.2lacZ/− embryos.

(a) lacZ mRNA expression at different time points during pancreas development is unchanged in Nkx2.2lacZ/− and Nkx2.2lacZ/+ embryos, suggesting that the number of lacZ-expressing cells is unchanged in Nkx2.2lacZ/− and Nkx2.2lacZ/+ embryos. (b) Nkx2.2 function is required for maximum expression of Ngn3 at e12.5 and e15.5. White and black bars represent Nkx2.2lacZ/+ and Nkx2.2lacZ/− respectively. * p≤0.05. (c) Hormone mRNA quantification in e15.5 Nkx2.2lacZ/− embryos compared to Nkx2.2lacZ/+.

Pancreatic expression of Nkx2.2 is initiated just after the onset of Pdx1 expression in both pancreatic buds, and co-expression of Nkx2.2 with Pdx1, Ptf1a, Nkx6.1 defines the progenitor cell population within the pancreatic epithelium (Jorgensen et al., 2007). In the Pdx1 null mice, the pancreatic primordia forms, but bud outgrowth and cell differentiation fails to proceed (Offield et al., 1996). To determine whether Nkx2.2 expression is retained in the Pdx1-deficient pancreatic primordia, we assessed Nkx2.2:lacZ expression in Pdx1 null mice (Nkx2.2lacZ/+; Pdx1tTA/tTA; (Holland et al., 2002). At e10.5, a small number of beta-galactosidase cells were detected within the remaining pancreatic primordia, indicating that initiation of Nkx2.2 pancreatic expression is not dependent on Pdx1 activity (Supplemental figure 5).

It has been previously demonstrated that Nkx2.2 and Ngn3 play intersecting regulatory roles in the developing pancreas (Anderson et al., 2009a; Anderson et al., 2009b; Wang et al., 2008). The two transcription factors directly and indirectly co-regulate a number of pancreatic transcription factors and possibly cross-regulate each other (Anderson et al., 2009b; Wang et al., 2008). In addition, although Nkx2.2 is expressed prior to the expression of Ngn3 and is required to maintain wild type levels of Ngn3 expression, the number of Ngn3-expressing endocrine progenitor cells is not affected in Nkx2.2−/− mice (Anderson et al., 2009b). In the Ngn3 null mice (Ngn3tTA/tTA), all endocrine cells fail to differentiate (Wang et al., 2009a; Gradwohl et al., 2000; Heller et al., 2005), but surprisingly Nkx2.2 mRNA expression is only decreased approximately 50% (Figure 6e). There was no statistical difference (p=0.1544; two-tailed student’s t test) in the reduction of Nkx2.2 expression in the Ngn3 null pancreas on either the Nkx2.2+/+ or Nkx2.2LacZ/+ genetic background (Figure 6e), confirming that the observed phenotype is not due haploinsufficiency that could be associated with loss of one Nkx2.2 allele on the sensitized Ngn3 null background. To determine which cell types maintain the expression of Nkx2.2 in the absence of Ngn3, we characterized the fate of Nkx2.2:lacZ expressing cells in Ngn3 null mice (Nkx2.2lacZ/+; Ngn3tTA/tTA). In normal pancreata at e18.5, LacZ is predominantly expressed in the differentiated endocrine cells as they move away from the ductal epithelium to form islets, although a small number of ductal cells still retain low level expression of LacZ (Figure 6a,a′,c,c′; arrows). In contrast, in the Ngn3tTA/tTA mice lacking all endocrine cells, beta-galactosidase remains expressed at high levels in almost all cells of the ductal epithelium, similar to Nkx2.2:LacZ expression in the ductal epithelium at earlier stages of pancreas development (Figure 3a-k). Interestingly, expression can also be detected at low levels in the nuclei of exocrine cells in the Ngn3 null pancreas (Figure 6b, b′, d, d′; arrowheads).

Figure 6. . Nkx2.2-lacZ is expressed in the absence of Ngn3.

(a–d) Co-immunostaining of beta-galactosidase and amylase, marker of acinar cells or DBA, marker of pancreatic ducts in Ngn3tTA/+ (a, c) and Ngn3tTA/tTA (b, d) e18.5 embryos. Arrows in a’ indicate the rare beta-galactosidase positive, Nkx2.2-expressing cells present in the ducts of wild type embryos. Arrowheads in b’ indicate beta-galactosidase expression in amylase-expressing cells in Ngn3 null mice. (e) Nkx2.2 mRNA expression in wild type (white bar, n=3), Ngn3tTA/tTA Nkx2.2+/+ (grey bar, n=5) and Ngn3tTA/tTA;Nkx2.2lacZ/+ (black bar, n=5) e16.5 embryos. * p≤0.05 vs wild type. There is no statistical difference (p=0.1544) in Nkx2.2 expression between the Ngn3tTA/tTA Nkx2.2+/+ and Ngn3tTA/tTA;Nkx2.2lacZ/+ embryos (two-tailed student’s t test). Magnification 20X. DAPI staining was used to visualize the nuclei in a, c, and d.

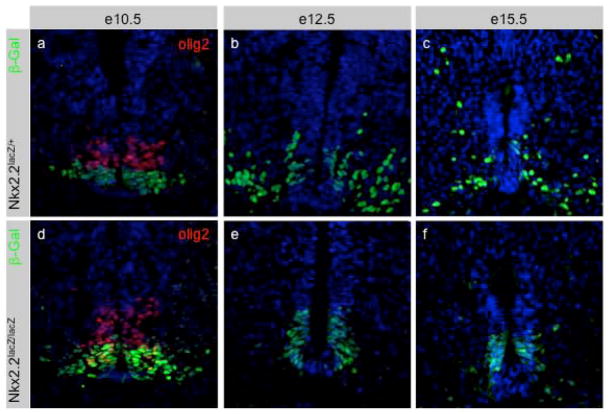

In addition to its expression in the pancreas, Nkx2.2 is expressed in the CNS where it is required for the appropriate differentiation of serotonergic neurons in the hindbrain (Briscoe et al., 1999; Pattyn et al., 2003a), and the ventral V3 interneurons and oligodendrocytes in the spinal cord (Briscoe et al., 2000; Briscoe et al., 1999; Qi et al., 2001). In the absence of Nkx2.2, the P3 progenitor domain forms, however the P3 progenitors appear to undergo a ventral-to-dorsal transformation to generate motor neurons in place of the Sim1 positive V3 interneurons (Briscoe et al., 1999). Consistent with this idea, in e10.5 Nkx2.2lacZ/lacZ embryos, beta-galactosidase-producing cells continue to migrate laterally out of the P3 ventricular zone, similar to Nkx2.2lacZ/+ control embryos (Figure 7d), although in the absence of Nkx2.2 the laterally located cells are ectopic motor neurons that express Lim3, HB9 and Isl1/2 (Briscoe et al., 1999). By e12.5, the Nkx2.2-expressing P3 progenitor cells give rise to oligodendrocyte precursors, which fail to differentiate in the Nkx2.2−/− mice (Qi et al., 2001). Interestingly, at this stage of development the spatial distribution of beta-galactosidase expressing cells in Nkx2.2lacZ/lacZ embryos is altered compared to Nkx2.2lacZ/+ littermates: beta-galactosidase expressing cells predominantly remain within the ventricular zone and do not migrate laterally (Figure 7e, 7f and data not shown). This is consistent with the hypothesis that Nkx2.2 is necessary for the appropriate differentiation of oligodendrocyte progenitors (Qi et al., 2001).

Figure 7. A subset of Nkx2.2-lacZ expressing neural progenitor cells fail to migrate out of the ventricular zone in the rostral spinal cord of Nkx2.2lacZ/lacZ mice.

(a,d) At e10.5, beta-galatosidase-expressing cells migrate laterally out of the ventricular zone in both Nkx2.2lacZ/+ and Nkx2.2lacZ/lacZ embryos. Immunofluorescent staining of Olig2 (red), which is normally repressed by Nkx2.2, shows co-expression of Olig2 and beta-galactosidase in the Nkx2.2lacZ/lacZ embryos, confirming this embryo has lost Nkx2.2 activity, despite the normal migration of progenitor cells. (b,e) At e12.5, beta-galactosidase cells migrate laterally out of the ventricular zone of the hindbrain in Nkx2.2lacZ/+ embryos, but not in Nkx2.2lacZ/lacZ littermates. (c,f)By e15.5, a large number of beta-galactosidase cells continue to migrate away from the midline in the Nkx2.2lacZ/+ embryos, but little migration can be observed in the Nkx2.2lacZ/lacZ embryos. DAPI staining was used to visualize the nuclei in all panels.

In Nkx2.2lacZ/+ mice, expression of beta-galactosidase in the intestine and stomach also reflects the known expression of endogenous Nkx2.2 (Supplemental figure 6; (Desai et al., 2008). In the stomach, beta-galactosidase is co-expressed with ghrelin as well as several other hormone producing populations (Supplemental figure 6a–b). In the intestine, beta-galactosidase expression can also be detected in the enteroendocrine cell populations, including ghrelin-expressing cells (Supplemental figure 6c). Furthermore, beta-galactosidase expression is present in the expanded ghrelin population that forms in the absence of Nkx2.2, indicating that similar to the pancreas, these cells are derived from Nkx2.2-expressing populations (Supplemental figure 6d).

Discussion

In this study, we describe the generation of mice carrying an Nkx2.2:lacZ knockin allele. To generate this new mouse line, we utilized recombination mediated cassette exchange (RMCE) technology. The RMCE technology consists of two sequential ES cell manipulations that ultimately produces an ES cell line that allows us the generation of multiple allele variants with high efficiency (Chen et al., 2011; Feng et al., 1999; Long et al., 2004). With this technology, we first generated an ES cell line containing the Nkx2.2 cassette acceptor allele (Nkx2.2LCA) using homologous recombination. The Nkx2.2LCA allele positions heterologous loxP sites within the Nkx2.2 genomic locus flanking a deletion of the two Nkx2.2 coding exons. These ES cells allowed us to introduce the Nkx2.2:lacZ allele described in this study into the Nkx2.2 locus with 40–50% efficiency. The Nkx2.2LCA allele also facilitates the generation of a series of Nkx2.2 targeted alleles with high efficiency. This is particularly useful since homologous recombination at the Nkx2.2 genomic locus has proven to occur with low efficiency due to the high G-C content and numerous repetitive elements associated within essential regions of this locus. To date, we have successfully used the Nkx2.2LCA ES cells to generate several new Nkx2.2 alleles, including two mutant alleles that disrupt distinct protein domains and alleles containing Cre-EGFP, rtTA and mCherry. Overall, the RCME technology has allowed us to overcome many of the challenging steps associated with gene targeting in mice and has facilitated further analysis of Nkx2.2 function in the development of the pancreas, intestine and CNS.

The Nkx2.2:lacZ allele was generated by replacing the Nkx2.2 coding exons with the lacZ gene. Expression of the beta-galactosidase protein faithfully recapitulates Nkx2.2 expression and provides a surrogate marker that allows us to monitor the fate of Nkx2.2-expressing cells when Nkx2.2 is deleted. The ability to follow the Nkx2.2-derived lineage in the absence of Nkx2.2 enabled us to directly test our previous hypothesis that cell-respecification is occurring in the Nkx2.2−/− mice. In the pancreatic islet and in the small intestine, elimination of Nkx2.2 resulted in the loss or reduction of several endocrine populations with the concomitant increase of the ghrelin-expressing cell population. In the Nkx2.2lacZ/lacZ mice, there was no discernable decrease in the numbers of lacZ-expressing cells, supporting the idea that loss of specific cell types was not due to the absence of a population of Nkx2.2-derived progenitor cells. Furthermore, the fact that the ghrelin cells in the Nkx2.2lacZ/lacZ pancreas also express LacZ suggests that the mutant ghrelin population is derived from Nkx2.2-producing progenitors rather than from non-Nkx2.2 expressing cell populations that expand in the absence of Nkx2.2 or the other mature hormone-producing cells. These studies also revealed LacZ expression in the populations of PP and glucagon cells that form in the absence of Nkx2.2, indicating that these cells are also derived from Nkx2.2-expressing progenitor cells, although it appears that their specification is independent of Nkx2.2 function.

In the CNS, Nkx2.2 is also required for the differentiation of several neuronal populations (Briscoe et al., 1999; Qi et al., 2001). This has been particularly well studied in the spinal cord, where V3 neurons and oligodendrocytes are sequentially derived from the Nkx2.2-expressing P3 progenitor domain. In the spinal cord prior to e12.5, it has been proposed that the loss of Nkx2.2 activity results in a “ventral-to-dorsal” switch in progenitor fate, such that the P3 progenitors now give rise to motor neurons. The observation that LacZ-expressing cells continue to migrate laterally out of the P3 progenitor domain of the Nkx2.2lacZ/lacZ embryos early in development validates the idea that the P3 progenitors are respecified to form the ectopic motor neurons, rather than an alternative mechanism by which the more dorsally located motor neurons expand and migrate ventrally into the space created by the loss of the V3 interneuron population. Interestingly, however, after e12.5 when P3 progenitors give rise to the oligodendrocyte lineage, beta-galactosidase-producing progenitor cells of Nkx2.2lacZ/lacZ embryos fail to migrate laterally and remain in the ventricular zone within a region of the rostral spinal cord. These cells likely delineate the oligodendrocyte precursor population that fails to differentiate in the absence of Nkx2.2. Future studies utilizing Nkx2.2:Cre mediated lineage tracing will be necessary to determine the ultimate fate of the Nkx2.2 P3 domain cells.

The creation of the Nkx2.2lacZ/+ mice also facilitated assessment of Nkx2.2 regulation by two essential pancreatic proteins, Pdx1 and Ngn3. Currently, the commercially available Nkx2.2 antibodies do not reliably detect Nkx2.2 protein expression in the developing pancreas, whereas X-gal staining is highly sensitive and there are several commercially available anti-beta-galactosidase antibodies made in different species that facilitate co-immunofluorescence analysis of different antigen combinations. We took advantage of these reagents to determine the fate of Nkx2.2-expressing cells in mice lacking either Pdx1 or Ngn3. Pdx1 and Nkx2.2 are two of the earliest genes to be expressed in the pancreatic progenitor domain, although Pdx1 expression arises shortly prior to Nkx2.2 (Jorgensen et al., 2007). Furthermore, Pdx1 null mice display almost complete pancreatic agenesis, while Nkx2.2 appears to function at later endocrine cell specification steps of pancreatic development (Offield et al., 1996; Sussel et al., 1998). Although, the respective expression patterns and mutant phenotypes indicate that Pdx1 functions upstream of Nkx2.2, it appears that Pdx1 is dispensable for initiation of Nkx2.2 expression in the pancreatic primordium that does form.

The functional relationship between Ngn3 and Nkx2.2 is less well-defined. Nkx2.2 expression precedes Ngn3 during pancreatic development and Ngn3 expression is reduced in the absence of Nkx2.2. Conversely, deletion of Ngn3 leads to the complete loss of all islet endocrine cells and therefore appears to function upstream of Nkx2.2, which only affects the specification of a subset of endocrine cells. Interestingly, analysis of Nkx2.2 (beta-galactosidase) expression in the Ngn3tTA/tTA pancreas indicated that Nkx2.2 expression is maintained at unexpectedly high levels in the epithelial ducts, which reflects wild type Nkx2.2 expression in earlier staged ductal cells. This may indicate that the ductal epithelial cells within the Ngn3tTA/tTA pancreas are blocked at a more immature stage of development. Another unexpected observation was the identification of low levels of Nkx2.2 (beta-galactosidase) expression in the acinar cells of the Ngn3tTA/tTA pancreas. Wang et al., (Wang et al., 2010) previously described that inactivation or reduction of Ngn3 levels, caused the reallocation of a subset of Ngn3-expressing endocrine progenitors to the exocrine lineage. Ngn3 and Nkx2.2 are expressed both individually and together in different populations of ductal epithelial progenitor cells. The identification of beta-galactosidase expression in the nuclei of amylase-expressing acinar cells of the Ngn3tTA/tTA pancreas suggests that the Ngn3-expressing progeny that become redirected to the exocrine lineage in the absence or reduction of Ngn3 are derived from the Ngn3 and Nkx2.2 co-expressing progenitor population.

In summary, the Nkx2.2:LacZ mouse provides a useful tool to study the function of Nkx2.2 in the pancreas, intestine and CNS. Furthermore, the creation of Nkx2.2 RMCE acceptor ES cells will facilitate the generation of additional Nkx2.2 alleles for in vivo analyses.

Materials and methods

Generation of Nkx2.2 RMCE ES cells and Nkx2.2:lacZ mice

A gene targeting vector for Nkx2.2 was constructed using the recombineering approach and utilizing the Cre-lox system for future RMCE manipulations as described in Chen et al. (Chen et al., 2011). The first step involved the generation of an Nkx2.2 acceptor allele (Nkx2.2LCA) in TL-1 ES cells (Labosky et al., 1994) using traditional homologous recombination. The targeting construct was derived from an Nkx2.2-encoding RP22 BAC clone (#183-A20). The short and long arm Nkx2.2 fragments (SA & LA) are 4,298 base pairs and 9,668 base pairs respectively. A 5,115 base pair region between these arms was replaced by the floxed tk-Kan cassette, a puromycin-Δthymidine kinase fusion gene driven by the mouse phosphoglycerol kinase promoter (pUΔTK) and a kanamycin resistant gene driven by the bacterial EM7 promoter (EM7-kan) flanked by minimal (34 bp) tandemly oriented lox71 and lox2272 sites (Cre-recombinase recognition sequences). The construct also contains a diphtheria toxin negative selection cassette (pgk-DT-A). All plasmids and their sources have been described in detail (Chen et al., 2011). The resulting Nkx2.2LCA gene targeting vector was linearized with NotI and used to electroporate TL-1 ES cells. 318 puromycin resistant colonies were screened by Southern blot using 5′ and 3′ external probes (Figure 1a). For 5′ probe analysis, genomic DNA was digested with NsiI to produce a wild type fragment of 17,819 base pairs and targeted fragment of 4,991 base pairs. For 3′ probe analysis, genomic DNA was digested with Kpn1 to generate a wild type fragment of 17,026 base pairs and targeted fragment of 15,504 base pairs. Eight clones (2.5% efficiency) contained the correctly targeted locus (Figure 1C). Three clones (2D4, 2G6 and 4E9) were used for subsequent RMCE targeting.

To generate the Nkx2.2:lacZ targeting vector, an Nkx2.2 basal exchange vector (pNkx2.2.Ex1.H; Supplemental figure 1) was first created. pNkx2.2.Ex1.H was generated by inserting the 5,115 base pair DNA fragment of the Nkx2.2 genomic locus that was removed from the Nkx2.2LCA targeting allele into pMCS.66/2772 (Chen et al., 2011). A smaller 3491 base pair HpaI DNA fragment from within the 5,115 base pair genomic fragment was then subcloned into a pGL3 vector to allow for efficient manipulation of the DNA using overlap PCR. The nls-lacZ gene (Picard and Yamamoto, 1987) was fused in frame with the Nkx2.2 start ATG on the 5′ end and 115 base pairs upstream of the stop codon on the 3′ end of Nkx2.2. The modified Nkx2.2:nls-lacZ fusion DNA was sequence verified and cloned back into the pNkx2.2.Ex1.H vector using the HpaI sites.

RMCE was performed in two parental clones (2G6 and 4E9) using a positive-negative selection strategy previously described (Chen et al., 2011; Long et al., 2004). In brief, approximately 6×106 mESCs containing the Nkx2.2LCA allele were co-electroporated with 40 μg of an exchange plasmid and 40 μg of pBS185, a Cre-expression plasmid (Sauer, 1998). 200 μg/ml neomycin (Invitrogen) was used for positive selection and 8 μM gancyclovir (Sigma, St Louis, MO) for negative selection. Surviving clones were screened by DNA PCR using the following primers: Primer 1 (Nkx.A-3′) 5′-CTGAGCAGCTCGGAGTGAGGCGCT-3′, Primer 2 (hygro 5′) 5′-ACGAGACTAGTGAGACGTGCTACT-3′; Primer 3 (Nkx2.2.P2) 5′-CGTCAACCTCAAATCTGGAGCCTA-3′; Primer 4 (Nkx.B-3′) 5′-ACTTGGTACGCAGATATTGAGA-3′. Primers 1 and 2 amplify a 606 bp DNA fragment only in the exchanged allele. Primers 3 and 4 detect a 556 bp fragment in the Nkx2.2:nlslacZ (hereafter referred to as Nkx2.2:lacZ) allele and a 479 bp fragment in the Nkx2.2 wild type locus. Correctly exchanged ES cell clones were expanded from the master plate and used to inject C57BL/6J blastocysts to generate Nkx2.2lacZ/+ mouse lines. Four of the eight parental clones gave germline transmission; one clone was subsequently maintained and used for all studies. The chimeras were initially back-crossed to C57BL/6J mice and subsequently maintained on an outbred Black Swiss (Taconic) background in order to replicate studies with the Nkx2.2−/− mice, which are also maintained on a Swiss Black background. No phenotypic variations have been observed throughout the breeding process.

Animals

Nkx2.2lacZ/+(Nkx2-2tm3Suss; MGI:5302422), Nkx2.2+/− (Nkx2-2tm1Jlr; MGI:1932100), Pdx1tTA/+ (Pdx1tm1Macd; MGI:2388676) and Ngn3tTA/+ (Neurog3tm2(tTA)Ggu; MGI:3850054) knockin mice were maintained on a Black Swiss (Taconic) background. Genotyping of mice and embryos was performed by PCR analysis. For Nkx2.2lacZ allele,5′-3 forward’: gagtggcgcttcgcctggtt and 5′-3′ reverse: agggagtagcagccggtggg primers were used. Nkx2.2+/−, Pdx1tTA/+ and Ngn3tTA/+ alleles were previously described (Holland et al., 2002; Sussel et al., 1998; Wang et al., 2009a). All mice were housed and treated according to the Columbia University IACUC approval protocol. All procedures to generate the Nkx2.2lacZ mice were approved by the Vanderbilt University Animal Care and Use Committee. The Nkx2.2LacZ/+ mice are available to the research community upon request.

Immunohistochemistry

Tissues were fixed in 4% PFA for four hours or overnight, washed in cold PBS, incubated in 30% sucrose and cryopreserved. Immunofluorescence was performed on 8μM sections. Sections were blocked in the appropriate serum (5% serum in 1x PBS + 0.5% triton-X) for 30 minutes. Primary antibodies were diluted in blocking buffer and incubated on tissue sections overnight at 4 degrees Celsius. The primary antibodies used were: anti-amylase (rabbit, 1:500; Sigma-Aldrich), anti-E-cadherin (rat, 1: 500; Zymed), anti-β-galactosidase (chicken, 1:500; Abcam), anti-ghrelin (goat, 1:500; Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Inc), anti-glucagon (guinea pig, 1:1000; Linco), anti-insulin (guinea pig, 1:200; Linco; rabbit, 1:200; Cell Signaling Technology), anti-neurogenin3 (rabbit, 1:500; Beta Cell Biology Consortium), anti-Pdx1 (rabbit, 1:1000; guinea pig, 1:1000; Millipore), anti-PP (rabbit, 1:500; Zymed), anti-Ptf1a (rabbit, 1:500; a gift from Ray Macdonald), anti-somatostatin (rabbit, 1:500; Phoenix Pharmaceuticals, Inc). Sections were incubated with appropriate secondary antibodies (Jackson Immunoresearch). DAPI (1:1000; Invitrogen) was applied for 30 minutes following secondary antibody incubation. Fluorescent images were obtained with a Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope, Q-image camera and ImagePro software (Media Cybernetics). Confocal images were captured using a Zeiss LSM 510 NLO Multiphoton. For quantification purposes, stained cells were counted manually on every seventh section throughout the entire pancreas for wild type (n=3) and mutant (n=3). All values are expressed as means +/− SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using a two-tailed Student’s unpaired t test. Results were considered significant when p < 0.05.

X-gal staining

Dissected tissues or whole embryo were briefly fixed with 4% PFA, rinsed in wash solution (0.1 M sodium phosphate, 0.1% deoxycholic acid, 0.2% NP40, 2 mM magnesium chloride) and stained in wash solution containing 1 mg/ml X-gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-b-D-galactoside).

After the whole-mount samples were photographed under the dissecting microscope, transverse frozen sections were prepared for histological analysis.

RNA Analysis

Total RNA was isolated from whole pancreatic tissue from the respective embryonic ages (RNeasy, QIAGEN), and cDNA was prepared using the SuperScript III kit (Invitrogen) and random hexamer primers. Quantitative PCR was performed using 200 ng cDNA, PCR master mix (Eurogentec) and Taqman probes (ABI Assays on Demand) for ghrelin (Mm00445450_m1), glucagon (Mm00801712_m1), insulin 2 (Mm00731595_gH), somatostatin (Mm00436671_m1), pancreatic polypeptide (Mm00435889_m1), Nkx2.2 (probe 5′: ccattgactctgccccatcgctct, forward primer, 5′-3′: cctccccgagtggcagat, reverse primer 5′-3′: gagttctatcctctccaaaagttcaaa) and neurogenin 3 (probe 5′: cctgcgcttcgcccacaact, forward primer, 5′-3′: gacgccaaacttacaaag, reverse primer 5′-3′: gtcagtgcccagatg t). LacZ mRNA expression was tested by Sybr-Green qPCR (forward primer, 5′-3′: gagtggcgcttcgcctggtt, reverse primer, 5′-3′: agggagtagcagccggtggg). All genes were normalized to Cyclophilin B and were quantified with ABI prism software. An n ≥4 was obtained for all mouse populations. All values are expressed as means +/− SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using a two-tailed Student’s unpaired t test. Results were considered significant when p < 0.05.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1: Non-specific X-gal staining is not observed in control embryos or Nkx2.2 non-expressing tissues. (a,b) X-gal staining of e10.5 and e12.5 wild type Nkx2.2 embryos; littermate controls of embryos shown in figure 2a and b, respectively. (c) X-gal staining of e17.5 wild type Nkx2.2 intestine shows no endogenous beta-galactosidase activity. (d) Nkx2.2 expression is not reduced in heterozygous Nkx2.2+/− or Nkx2.2LacZ/+ compared to wild type (e) Transverse section at e9.5 indicates Nkx2.2:lacZ expression in the CNS and foregut endoderm, but not elsewhere in the embryo, consistent with endogenous Nkx2.2 expression. Boxed regions are magnified in d′-d‴. SC, spinal cord; FG, foregut. (f) Whole pancreas isolated from Nkx2.2lacZ/+ adult and stained with X-gal demonstrates that Nkx2.2:LacZ expression in restricted to islets and is not expressed throughout the exocrine tissue. The area indicated by the black box is magnified in f′.

Figure S2: Nkx2.2:lacZ expression is mostly restricted to endocrine and ductal cells in Nkx2.2lacZ/+ and Nkx2.2lacZ/lacZembryos and adults. (a) Beta-galactosidase is not expressed in the exocrine tissue stained with amylase in adult Nkx2.2lacZ/+ mice. (b) Scattered cells in the duct and centroacinar cells are positive for X-gal staining in adult Nkx2.2lacZ/+ mice. (c,d) Representative low magnification images of beta-galactosidase and amylase co-staining in the pancreata of Nkx2.2lacZ/+ and Nkx2.2lacZ/lacZ mice indicate there are no major anatomical alterations caused by the loss of Nkx2.2 using this new Nkx2.2:lacZ mutant allele.

Figure S3. Nkx2.2:lacZ is expressed in the Pdx1+/Ptf1a+ pancreatic progenitor domain. (a, b, c) Immunofluorescence staining on adjacent sections at e12.5 shows Nkx2.2-lacZlow expressing cells co-localize with the Pdx1+/Ptf1a+ domain. (d) An adjacent section shows that the region of Nkx2.2-lacZhigh and Pdx1low/Ptf1alow cells(indicated by the dashed line) co-express glucagon. DAPI staining was used to visualize the nuclei in d.

Figure S4. The phenotypes of Nkx2.2lacZ/lacZ and Nkx2. 2LacZ/− mice are indistinguishable from mice carrying the Nkx2.2 null allele. (a-f) Immunofluorecence staining with insulin, glucagon and ghrelin at e15.5 shows that Nkx2.2 heterozygous Nkx2.2+/− or Nkx2.2LacZ/+pancreata are phenotypically indistinguishable from the pancreas in wild type embryos (a-c) and the Nkx2.2lacZ/lacZ and Nkx2.2LacZ/− phenotypes recapitulate the Nkx2.2 null phenotype. DAPI staining was used to visualize the nuclei.

Figure S5. Initiation of Nkx2.2:lacZ expression is not dependent on Pdx1 activity. (a,b) e10.5 X-gal staining in the pancreatic epithelium of Pdx1+/+ and Pdx1tTA/tTA embryos. Magnification 20X. Inset in b shows a magnification of the remaining Nkx2.2:lacZ-expressing cells in the pancreatic epithelium of Pdx1 null embryos.

Figure S6. Nkx2.2:lacZ is expressed in stomach and intestine. (a) Beta-galactosidase expression in the stomach (outlined within the dashed lines) of an e18.5 embryo. (b) Magnification of the boxed area in (a) indicates beta-galactosidase-positive cells co-staining with ghrelin. (c,d) Beta-galactosidase is co-expressed with ghrelin in the intestine of Nkx2.2lacZ/+ and Nkx2.2lacZ/lacZ embryos. Insets show 40x magnification of boxed regions. DAPI staining was used to visualize the nuclei.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jan N. Jensen and Palle Serup (Hagedorn Research Institute) for sharing the Ngn3:tTA mice and Ray Macdonald (UT Southwestern) for sharing the Pdx1:tTA mice. We thank Kathy Shelton for assistance with generating the RMCE ES cells. We would also like to thank members of the Sussel lab for scientific discussions and critical reading of the manuscript. Support for this study was provided by NIH Beta Cell Biology Consortium (BCBC) grants U01 DK072504 (LS), U01 DK089523 (LS,MM); NIH grant R01 DK082590 (LS); Foundation for Diabetes Research (LA). Additional support was provided by the Columbia University DERC (P30 DK63608) and the Vanderbilt Transgenic Mouse/ES Cell Shared Resource.

References

- Aguirre A, Gallo V. Postnatal neurogenesis and gliogenesis in the olfactory bulb from NG2-expressing progenitors of the subventricular zone. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2004;24:10530–10541. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3572-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson KR, Torres CA, Solomon K, Becker TC, Newgard CB, Wright CV, Hagman J, Sussel L. Cooperative transcriptional regulation of the essential pancreatic islet gene NeuroD1 (beta2) by Nkx2.2 and neurogenin 3. J Biol Chem. 2009a;284:31236–31248. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.048694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson KR, White P, Kaestner KH, Sussel L. Identification of known and novel pancreas genes expressed downstream of Nkx2.2 during development. BMC Dev Biol. 2009b;9:65. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-9-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briscoe J, Pierani A, Jessell TM, Ericson J. A homeodomain protein code specifies progenitor cell identity and neuronal fate in the ventral neural tube. Cell. 2000;101:435–445. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80853-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briscoe J, Sussel L, Serup P, Hartigan-O’Connor D, Jessell TM, Rubenstein JL, Ericson J. Homeobox gene Nkx2.2 and specification of neuronal identity by graded Sonic hedgehog signalling. Nature. 1999;398:622–627. doi: 10.1038/19315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen SX, Osipovich AB, Ustione A, Potter LA, Hipkens S, Gangula R, Yuan W, Piston DW, Magnuson MA. Quantification of factors influencing fluorescent protein expression using RMCE to generate an allelic series in the ROSA26 locus in mice. Dis Model Mech. 2011 doi: 10.1242/dmm.006569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai S, Loomis Z, Pugh-Bernard A, Schrunk J, Doyle MJ, Minic A, McCoy E, Sussel L. Nkx2.2 regulates cell fate choice in the enteroendocrine cell lineages of the intestine. Dev Biol. 2008;313:58–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.09.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ericson J, Rashbass P, Schedl A, Brenner-Morton S, Kawakami A, van Heyningen V, Jessell TM, Briscoe J. Pax6 controls progenitor cell identity and neuronal fate in response to graded Shh signaling. Cell. 1997;90:169–180. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80323-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng YQ, Seibler J, Alami R, Eisen A, Westerman KA, Leboulch P, Fiering S, Bouhassira EE. Site-specific chromosomal integration in mammalian cells: highly efficient CRE recombinase-mediated cassette exchange. J Mol Biol. 1999;292:779–785. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gradwohl G, Dierich A, LeMeur M, Guillemot F. neurogenin3 is required for the development of the four endocrine cell lineages of the pancreas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:1607–1611. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.4.1607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heller RS, Jenny M, Collombat P, Mansouri A, Tomasetto C, Madsen OD, Mellitzer G, Gradwohl G, Serup P. Genetic determinants of pancreatic epsilon-cell development. Dev Biol. 2005;286:217–224. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland AM, Hale MA, Kagami H, Hammer RE, MacDonald RJ. Experimental control of pancreatic development and maintenance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:12236–12241. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192255099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen MC, Ahnfelt-Ronne J, Hald J, Madsen OD, Serup P, Hecksher-Sorensen J. An illustrated review of early pancreas development in the mouse. Endocr Rev. 2007;28:685–705. doi: 10.1210/er.2007-0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Nirenberg M. Drosophila NK-homeobox genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:7716–7720. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.20.7716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labosky PA, Barlow DP, Hogan BL. Mouse embryonic germ (EG) cell lines: transmission through the germline and differences in the methylation imprint of insulin-like growth factor 2 receptor (Igf2r) gene compared with embryonic stem (ES) cell lines. Development. 1994;120:3197–3204. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.11.3197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long Q, Shelton KD, Lindner J, Jones JR, Magnuson MA. Efficient DNA cassette exchange in mouse embryonic stem cells by staggered positive-negative selection. Genesis. 2004;39:256–262. doi: 10.1002/gene.20053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Offield MF, Jetton TL, Labosky PA, Ray M, Stein RW, Magnuson MA, Hogan BL, Wright CV. PDX-1 is required for pancreatic outgrowth and differentiation of the rostral duodenum. Development. 1996;122:983–995. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.3.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattyn A, Vallstedt A, Dias JM, Samad OA, Krumlauf R, Rijli FM, Brunet JF, Ericson J. Coordinated temporal and spatial control of motor neuron and serotonergic neuron generation from a common pool of CNS progenitors. Genes Dev. 2003a;17:729–737. doi: 10.1101/gad.255803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattyn A, Vallstedt A, Dias JM, Sander M, Ericson J. Complementary roles for Nkx6 and Nkx2 class proteins in the establishment of motoneuron identity in the hindbrain. Development. 2003b;130:4149–4159. doi: 10.1242/dev.00641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picard D, Yamamoto KR. Two signals mediate hormone-dependent nuclear localization of the glucocorticoid receptor. The EMBO journal. 1987;6:3333–3340. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02654.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prado CL, Pugh-Bernard AE, Elghazi L, Sosa-Pineda B, Sussel L. Ghrelin cells replace insulin-producing beta cells in two mouse models of pancreas development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:2924–2929. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308604100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price M, Lazzaro D, Pohl T, Mattei MG, Ruther U, Olivo JC, Duboule D, Di Lauro R. Regional expression of the homeobox gene Nkx-2.2 in the developing mammalian forebrain. Neuron. 1992;8:241–255. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90291-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi Y, Cai J, Wu Y, Wu R, Lee J, Fu H, Rao M, Sussel L, Rubenstein J, Qiu M. Control of oligodendrocyte differentiation by the Nkx2.2 homeodomain transcription factor. Development. 2001;128:2723–2733. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.14.2723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauer B. Inducible gene targeting in mice using the Cre/lox system. Methods. 1998;14:381–392. doi: 10.1006/meth.1998.0593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimamura K, Hartigan DJ, Martinez S, Puelles L, Rubenstein JL. Longitudinal organization of the anterior neural plate and neural tube. Development. 1995;121:3923–3933. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.12.3923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sussel L, Kalamaras J, Hartigan-O’Connor DJ, Meneses JJ, Pedersen RA, Rubenstein JL, German MS. Mice lacking the homeodomain transcription factor Nkx2.2 have diabetes due to arrested differentiation of pancreatic beta cells. Development. 1998;125:2213–2221. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.12.2213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonchev AB, Yamashima T, Sawamoto K, Okano H. Transcription factor protein expression patterns by neural or neuronal progenitor cells of adult monkey subventricular zone. Neuroscience. 2006;139:1355–1367. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.01.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Hecksher-Sorensen J, Xu Y, Zhao A, Dor Y, Rosenberg L, Serup P, Gu G. Myt1 and Ngn3 form a feed-forward expression loop to promote endocrine islet cell differentiation. Dev Biol. 2008;317:531–540. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Jensen JN, Seymour PA, Hsu W, Dor Y, Sander M, Magnuson MA, Serup P, Gu G. Sustained Neurog3 expression in hormone-expressing islet cells is required for endocrine maturation and function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009a;106:9715–9720. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904247106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Yan J, Anderson DA, Xu Y, Kanal MC, Cao Z, Wright CV, Gu G. Neurog3 gene dosage regulates allocation of endocrine and exocrine cell fates in the developing mouse pancreas. Dev Biol. 2010;339:26–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YC, Gallego-Arteche E, Iezza G, Yuan X, Matli MR, Choo SP, Zuraek MB, Gogia R, Lynn FC, German MS, Bergsland EK, Donner DB, Warren RS, Nakakura EK. Homeodomain transcription factor NKX2.2 functions in immature cells to control enteroendocrine differentiation and is expressed in gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2009b;16:267–279. doi: 10.1677/ERC-08-0127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watada H, Scheel DW, Leung J, German MS. Distinct gene expression programs function in progenitor and mature islet cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:17130–17140. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M213196200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Q, Choi G, Anderson DJ. The bHLH transcription factor Olig2 promotes oligodendrocyte differentiation in collaboration with Nkx2.2. Neuron. 2001;31:791–807. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00414-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1: Non-specific X-gal staining is not observed in control embryos or Nkx2.2 non-expressing tissues. (a,b) X-gal staining of e10.5 and e12.5 wild type Nkx2.2 embryos; littermate controls of embryos shown in figure 2a and b, respectively. (c) X-gal staining of e17.5 wild type Nkx2.2 intestine shows no endogenous beta-galactosidase activity. (d) Nkx2.2 expression is not reduced in heterozygous Nkx2.2+/− or Nkx2.2LacZ/+ compared to wild type (e) Transverse section at e9.5 indicates Nkx2.2:lacZ expression in the CNS and foregut endoderm, but not elsewhere in the embryo, consistent with endogenous Nkx2.2 expression. Boxed regions are magnified in d′-d‴. SC, spinal cord; FG, foregut. (f) Whole pancreas isolated from Nkx2.2lacZ/+ adult and stained with X-gal demonstrates that Nkx2.2:LacZ expression in restricted to islets and is not expressed throughout the exocrine tissue. The area indicated by the black box is magnified in f′.

Figure S2: Nkx2.2:lacZ expression is mostly restricted to endocrine and ductal cells in Nkx2.2lacZ/+ and Nkx2.2lacZ/lacZembryos and adults. (a) Beta-galactosidase is not expressed in the exocrine tissue stained with amylase in adult Nkx2.2lacZ/+ mice. (b) Scattered cells in the duct and centroacinar cells are positive for X-gal staining in adult Nkx2.2lacZ/+ mice. (c,d) Representative low magnification images of beta-galactosidase and amylase co-staining in the pancreata of Nkx2.2lacZ/+ and Nkx2.2lacZ/lacZ mice indicate there are no major anatomical alterations caused by the loss of Nkx2.2 using this new Nkx2.2:lacZ mutant allele.

Figure S3. Nkx2.2:lacZ is expressed in the Pdx1+/Ptf1a+ pancreatic progenitor domain. (a, b, c) Immunofluorescence staining on adjacent sections at e12.5 shows Nkx2.2-lacZlow expressing cells co-localize with the Pdx1+/Ptf1a+ domain. (d) An adjacent section shows that the region of Nkx2.2-lacZhigh and Pdx1low/Ptf1alow cells(indicated by the dashed line) co-express glucagon. DAPI staining was used to visualize the nuclei in d.

Figure S4. The phenotypes of Nkx2.2lacZ/lacZ and Nkx2. 2LacZ/− mice are indistinguishable from mice carrying the Nkx2.2 null allele. (a-f) Immunofluorecence staining with insulin, glucagon and ghrelin at e15.5 shows that Nkx2.2 heterozygous Nkx2.2+/− or Nkx2.2LacZ/+pancreata are phenotypically indistinguishable from the pancreas in wild type embryos (a-c) and the Nkx2.2lacZ/lacZ and Nkx2.2LacZ/− phenotypes recapitulate the Nkx2.2 null phenotype. DAPI staining was used to visualize the nuclei.

Figure S5. Initiation of Nkx2.2:lacZ expression is not dependent on Pdx1 activity. (a,b) e10.5 X-gal staining in the pancreatic epithelium of Pdx1+/+ and Pdx1tTA/tTA embryos. Magnification 20X. Inset in b shows a magnification of the remaining Nkx2.2:lacZ-expressing cells in the pancreatic epithelium of Pdx1 null embryos.

Figure S6. Nkx2.2:lacZ is expressed in stomach and intestine. (a) Beta-galactosidase expression in the stomach (outlined within the dashed lines) of an e18.5 embryo. (b) Magnification of the boxed area in (a) indicates beta-galactosidase-positive cells co-staining with ghrelin. (c,d) Beta-galactosidase is co-expressed with ghrelin in the intestine of Nkx2.2lacZ/+ and Nkx2.2lacZ/lacZ embryos. Insets show 40x magnification of boxed regions. DAPI staining was used to visualize the nuclei.