Abstract

Objective

The proinflammtory cytokine tumor necrosis factor (TNF), primarily via TNF receptor 1 (TNFR1), induces NF-κB-dependent cell survival, and JNK and caspase-dependent cell death, regulating vascular endothelial cell (EC) activation and apoptosis. However, signaling by the second receptor, TNFR2, is poorly understood. The goal of this study is to dissect how TNFR2 mediates NF-κB and JNK signaling in vascular endothelial cells (EC), and its relevance with in vivo EC function.

Methods and Results

We show that TNFR2 contributes to TNF-induced NF-κB and JNK signaling in EC as TNFR2 deletion or knockdown reduces the TNF responses. To dissect out the critical domains of TNFR2 that mediate the TNF responses, we examine the activity of TNFR2 mutant with a specific deletion of the TNFR2 intracellular region, which contains conserved domain I, domain II, domain III, and two TRAF2-binding sites. Deletion analyses indicate that different sequences on TNFR2 have distinct roles in NF-κB and JNK activation. Specifically, deletion of the TRAF2-binding sites (TNFR2-59) diminishes the TNFR2-mediated NF-κB, but not JNK activation; whereas, deletion of domain II or domain III blunts TNFR2-mediated JNK but not NF-κB activation. Interestingly, we find that the TRAF2-binding sites ensure TNFR2 on the plasma membrane, but the di-leucine LL motif within the domain II and aa338-355 within the domain III are required for TNFR2 internalization as well as TNFR2-dependent JNK signaling. Moreover, domain III of TNFR2 is responsible for association with AIP1, a signaling adaptor critical for TNF-induced JNK signaling. While TNFR2 containing the TRAF2-binding sites prevents EC cell death, a specific activation of JNK without NF-κB activation by TNFR2-59 strongly induces caspase activation and EC apoptosis.

Conclusion

Our data reveal that both internalization and AIP1 association are required for TNFR2-dependent JNK and apoptotic signaling. Controlling TNFR2-mediated JNK and apoptotic signaling in EC may provide a novel strategy for the treatment of vascular diseases.

Keywords: TNF, TNFR2, JNK, endothelial cell, apoptosis

INTRODUCTION

Vascular endothelial cells (EC) are among the principal physiological targets of prototypic inflammatory cytokine tumor necrosis factor (TNF)1, 2. In EC, as in other cell types, TNF elicits a broad spectrum of biological effects including proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis3. The nature of the TNF effects depends on TNF concentration, and the type and growth state of the target cells4. These differences in TNF-induced response are also due, in part, to the presence of two distinct TNF-specific plasma membrane-localized receptors, type I 55 kDa TNFR (TNFR1) and type II 75 kDa TNFR (TNFR2)5. Mice with genetic deletion of TNFR1 or TNFR2 (TNFR1-KO and TNFR2-KO) are viable and do not show any overt phenotypic abnormalities. Data from studies using these mice suggest that TNFR1 is primarily responsible for TNF-mediated host defense and inflammatory responses6. We have previously characterized the vascular phenotypes of TNFR1-KO and TNFR2-KO mice7, 8. These studies have demonstrated that TNFR1-KO and TNFR2-KO mice are “normal” in vascular development. However, TNFR1-KO and TNFR2-KO mice have distinct phenotype in ischemia-induced models. TNFR2, but not TNFR1, is highly upregulated in vascular endothelium in response to ischemia. TNFR1-KO mice have enhanced whereas TNFR2-KO have reduced capacity in ischemia-induced angiogenesis and tissue recovery7, 8.

TNFR1-mediated signaling pathways have been well characterized9. The intracellular portion of TNFR1 can be subdivided into a membrane proximal and a membrane distal part. The latter contains a “death domain” which can also be found in other receptors involved in cell death (e.g., Fas). A current model postulates that TNF binding triggers trimerization of TNFR1, which recruits adaptor proteins and signaling molecules by their intracellular domains to form a receptor-signaling complex9. The first to be recruited is the TNFR-associated death domain protein (TRADD)10. TRADD functions as a platform adaptor that recruits TNFR-associated factor-2 (TRAF2), and receptor-interacting protein kinase-1 (RIPK1)11, 12. It has been proposed that TNF-induced NF-κB, JNK and apoptosis pathways are sequentially activated, and early NF-κB signaling can inhibit JNK and apoptosis in EC. Specifically, the initial plasma membrane bound complex (complex I, comprised of TNFR1, TRADD, RIPK1 and TRAF2) for NF-κB activation, and a cytoplasmic complex (complex II or the death-inducing signaling complex (DISC)), in which the internalized TRADD, TRAF2 and RIPK1, recruits FADD and pro-caspase-8 for apoptotic signaling13. Because the NF-κB-induced protein synthesis of FLIP normally prevents the recruitment of procaspase-8/10 to FADD and therefore the formation of complex II, Complex II formation can only be detected at 2–8 h post-treatment with TNF in cells overexpressing the NF-κB inhibitor IκBα. Data from Schutze’s lab has also demonstrated that TNFR1 endocytosis is required for the formation of DISC14. Different from the findings in a study by Tschopp’s group, TNFR1 is a component of the intracellular DISC complex. Our previous data support that an intermediate complex between complex I and complex II (likely an internalized complex I) is responsible for TNF-induced JNK activation15–17. Because AIP1 is different component than complex I, we name it the AIP1 complex. We have demonstrated that the AIP1 complex is structurally and functionally different from complex I and complex II. The AIP1 complex activates JNK, while it inhibits NF-κB signaling. Moreover, AIP1-ASK1-JNK activation induces apoptotic signaling, which is dependent on intrinsic (mitochondria-dependent) pathways15–17. In EC, NF-κB is associated with cell survival while the JNK pathway is involved in apoptosis1, 2.

In contrast, the function and signaling of the second TNF receptor, TNFR2, is less well understood. This is due to several reasons. First, TNFR2 expression is limited to specific cell types, including EC, cardiac myocytes and hematopoietic cells6. Moreover, TNFR2 is often induced in response to certain stimuli, for instance, in the activation of macrophage and T lymphocytes that results in a marked increase in TNFR2 levels6, 18. TNFR2 is also highly induced in vascular EC in ischemia hindlimb, as we recently demonstrated7, 8. Second, the intracellular domains of TNFR2 and interacting proteins are not well defined. Although TRAF2 was initially identified as a TNFR2-binding protein19, subsequent studies have been focused on its role in TNFR1 signaling. Trimerization of TNFR2 in response to TNF leads to the recruitment of TRAF2 and TRAF2-associated TRAF1, cIAP1 and cIAP2. We have previously identified a Bmx-binding sequence at the C-terminus of TNFR2, which constitutively binds to non-receptor tyrosine kinase Bmx, contributing to TNFR2-mediated Akt activation, EC migration and proliferation7, 8, 20, 21. It has been shown that the Bmx-binding sequence also recruits TRAF2, regulating TNFR2-mediated NF-κB signaling22, 23. Recent studies suggest that TNFR2, independent of TNFR1, activates both canonical and noncanonical NF-κB pathways18. Specifically, TNFR2 through PI3K/Akt induces phosphorylation of IKKβ and subsequent activation of the canonical NF-κB pathway24. Only membrane-bound TNF triggers TNFR2-mediated NF-κB-inducing kinase (NIK)/IKKα-dependent noncanonical pathway25. However, the mechanism by which TNFR2 induces JNK activation has not been investigated.

In the present study, we show that TNFR2 significantly contributes to TNF-induced NF-κB and JNK activation in vascular EC. We identify two sequences other than the TRAF2-binding site are required for TNFR2-dependent JNK activation. Moreover, these sequences of TNFR2 are critical for its internalization and its association with AIP1, an adaptor molecule specific for JNK signaling. This is the first study, to our best knowledge, to dissect the TNFR2-mediated JNK signaling pathway.

METHODS

The detailed materials and methods are provided in the online supplement. Most of the methods have been previously published, including plasmids, cell culture, transfection, reporter gene assay, immunoprecipitation, immunoblotting, indirect immunofluorescence micropscopy, and quantification of apoptosis7.

RESULTS

TNFR2 contributes to TNF-induced NF-κB and JNK signaling pathways in vascular EC

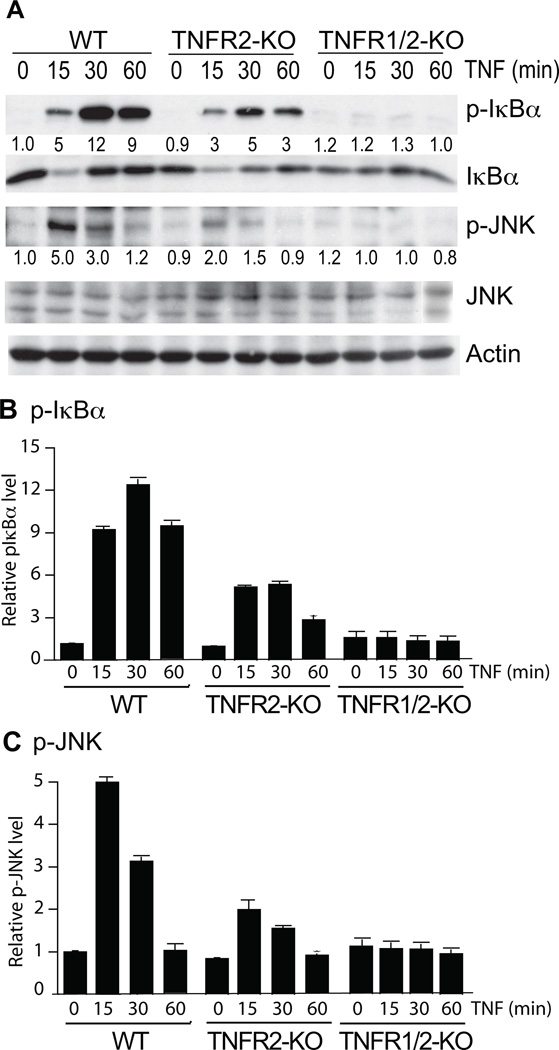

To determine the role of TNFR2 in TNF signaling, we first examined the TNF responses in mouse lung EC (MLEC) isolated from WT and TNFR2-KO mice. MLEC were treated with murine recombinant TNF for the indicated times (0, 15, 30 and 60 min), and activation of the NF-κB and JNK pathways were determined by immunoblotting with phospho-specific antibodies. Consistent with previous observations in other EC types (HUVEC and BAEC)15–17, TNF induced phosphorylation of IκBα (an indication of NF-κB activation) and JNK, peaking at 15–30 min in WT cells. TNFR2 deletion in EC reduced TNF-induced both NF-κB and JNK signaling by 50–60% compared to WT EC (Fig.1A with quantifications in Fig.1B,C). Further deletion of TNFR1 (TNFR1/2-DKO) in EC (Supplemental Fig.1A for TNFR1 and TNFR2 expression) completely abolished the TNF responses (Fig.1A with quantifications in Fig.1B,C). Knockdown of TNFR2 in human EC (HUVEC) by siRNA also reduced human TNF-induced NF-κB and JNK activation (Supplemental Fig.IB). These data suggest that TNFR2 contributes to TNF-induced NF-κB and JNK activation in EC.

Fig.1. TNFR2 contributes to TNF-induced NF-κB and JNK signaling pathways in EC.

WT, TNFR2-KO and TNFR1/2-KO MLEC (1×106) were treated with murine recombinant TNF (10 ng/ml) for the indicated times. Phospho- and total IκBα and JNK were determined by immunoblotting with the respective antibodies (A). The quantification of the ratios of p-IκBα/ IκBα and p-JNK/JNK are presented in B and C, respectively. Data are the mean ± SEM from three independent experiments. *, p<0.05 indicating statistic significance compared to the untreated VC.

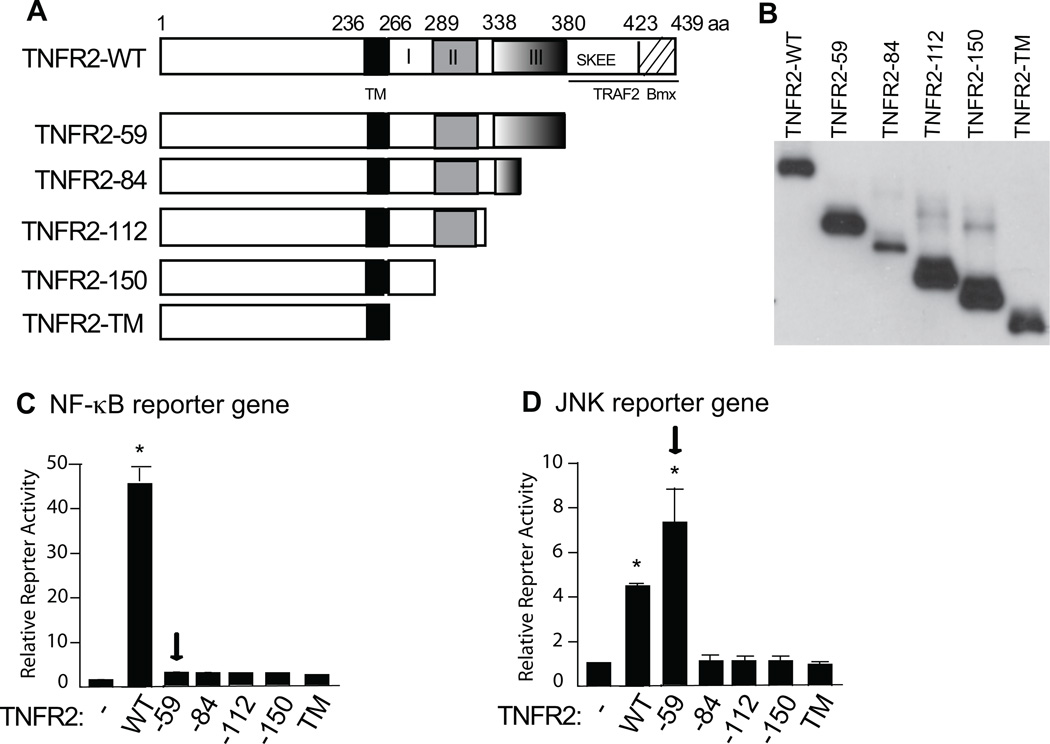

The TRAF2-binding sites are required for TNFR2-mediated NF-κB but not JNK activation

It has been shown that TNFR2 contains two TRAF2-binding sites at the C-terminus, the first being the SKEE motif and the second is the last 16 aa sequence22, 23 that overlaps with a Bmx-binding sequence7, 8, 20. Each TRAF2 site mediates TNFR2-transduced NF-κB activation independently22, 23. Besides the TRAF2-binding consensus sequences, sequence alignment of TNFR2 intracellular regions from different species revealed three additional conserved domains – domain I (aa266-289), domain II (aa289-338) and domain III (aa338-380) (Fig.2A). To determine the TNFR2 domain critical for JNK activation, we constructed a series of TNFR2 truncations with deletions of these various domains (Fig.2A,B). Activities of TNFR2 mutants in NF-κB and JNK signaling were determined by NF-κB- and JNK-reporter gene assays in TNFR2-null MLEC (Fig.2B). Overexpression of TNFR2-WT, similar to overexpression of TNFR1 or TRAF219, activated both NF-κB and JNK-reporter genes in a ligand-independent manner. Consistent with our previous findings7, deletion of the TRAF2-binding sites (TNFR2-59) abolished TNFR2-mediated NF-κB activation (Fig.2C). To our surprise, TNFR2-59 retained the ability to activate the JNK reporter gene, suggesting that the TRAF2-binding sites are not required for TNFR2-mediated JNK signaling. However, a partial (TNFR2-84) or a complete deletion of the domain III (TNFR2-112) blunted TNFR2-dependent JNK activation. Further deletions of domain II and domain I (TNFR2-150 and TNFR2-TM) had similar effects on the JNK reporter gene (Fig.2D). These data suggest that TNFR2 utilizes different regions to transduce NF-κB and JNK signaling, and the sequence between TNFR2-84 and TNFR2-59 could be important for TNFR2-mediated JNK activation.

Fig.2. The TRAF2-binding sites are required for TNFR2-mediated NF-κB but not JNK activation.

A. Schematic structure of TNFR2 and the truncated deletions at the C terminus. The numbers refer to the amino acid number, indicating the boundary of the extracellular and intracellular domains (I–III). TM: transmembrane; A TRAF2-binding motif (SKEE) and Bmx-binding sequence are also indicated. B. Expression of TNFR2 truncates as detected by immunoblotting with anti-TNFR2. C–D. Effects of TNFR2 truncation on NF-κB and JNK activation in reporter gene assays. A NF-κB-reporter gene or JNK-reporter gene was transfected into TNFR2-KO MLEC in the presence of vector control (−), TNFR2-WT or mutants. Cells were harvested for luciferase/renilla assays at 48 h post-transfection. Data are presented as mean ± SEM of duplicate samples from four independent experiments. *, p<0.05 indicating statistic significance compared to the vector control (normalized to 1.0). Arrows indicated that TNFR2-59 cannot activate NF-κB, but retains JNK activation.

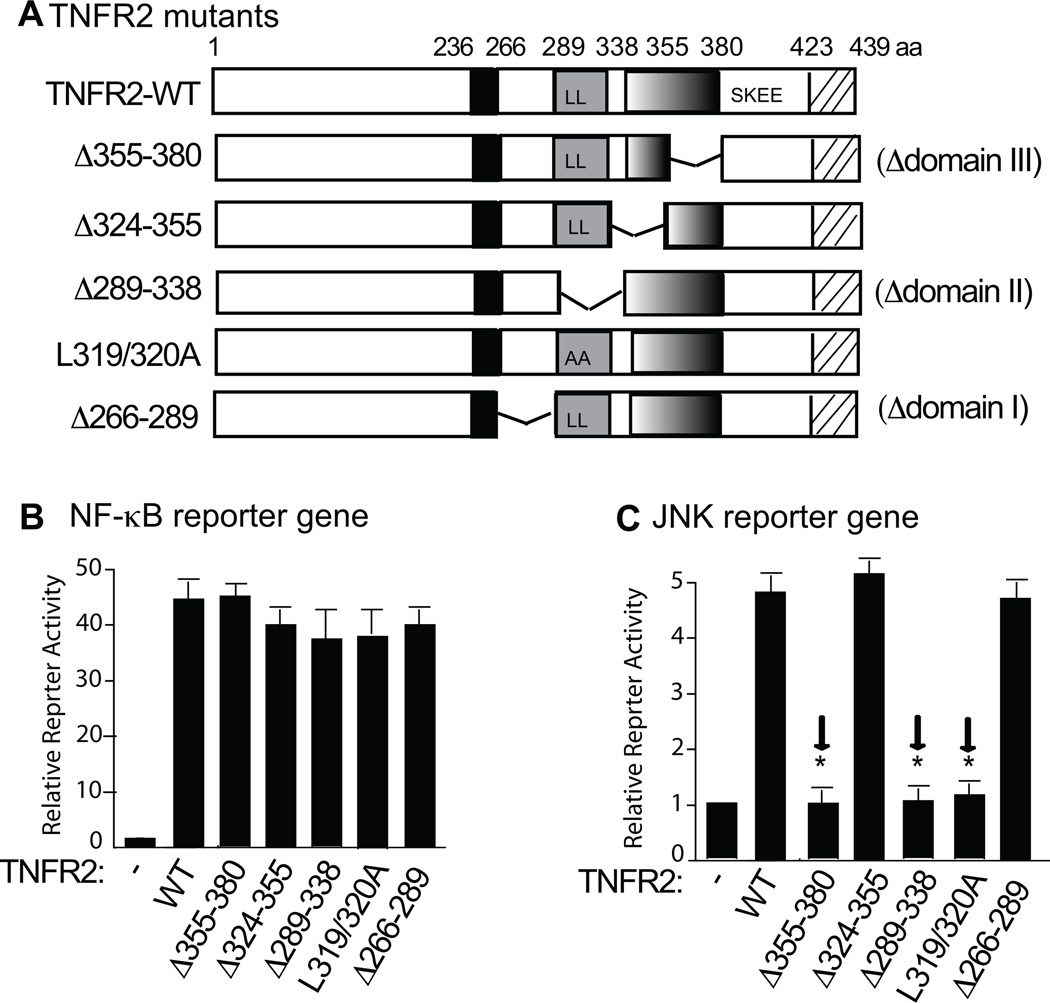

Both domain II and domain III are required for TNFR2-mediated JNK activation

The results above using the C-terminal truncations supported a role of the domain III in TNFR2-mediated JNK activation. However, the role of domain I and domain II could not be determined. To this end, each domain was then internally deleted (Δ266-289 for domain I, Δ289-338 for domain II, Δ338-355 for the first half of domain III, and Δ355-380 for the second half of domain III - the sequence located between TNFR2-84 to -59 that is critical for JNK activation). Domain II contains a di-leucine motif which has recently been shown to be important for TNFR2 internalization26. Therefore, we made a site-specific mutation at the di-leucine motif (L319/320A) (Fig.3A). These internal deletions had no effects on TNFR2 expression (not shown; also see Fig.4). Effects of these deletions/mutations on TNFR2-mediated signaling were assessed in the reporter gene assays. TNFR2 with a deletion of domain I, II or III retained the ability to activate NF-κB reporter gene. Similar to the deletion of domain II, mutations at the di-leucine motif had no effects on TNFR2-mediated NF-κB activation (Fig.3B), consistent with a recent report26. In contrast, a deletion of domain II or a mutation at the di-leucine motif was sufficient to abolish TNFR2 activity in JNK activation (Fig.3C). A deletion at the first half of domain III (Δ338-355) had no effects on JNK activation. However, deletion at the second half (Δ355-380), similar to TNFR2-84, diminished TNFR2-mediated JNK activation (Fig.3C). These data suggest that both di-leucine motif within domain II and the second half of domain III are required for TNFR2-mediated JNK activation.

Fig.3. Both domain II and domain III are required for TNFR2-mediated JNK activation.

A. Schematic structure of TNFR2 and the internal deletion mutants. The numbers refer to the amino acid number, indicating the boundary of the extracellular and intracellular domains (I–III). LL: a di-luecine motif. B–C. Effects of TNFR2 internal deletions on NF-κB and JNK activation in reporter gene assays. A NF-κB-reporter gene or JNK-reporter gene was transfected into TNFR2-KO MLEC in the presence of vector control (−), TNFR2-WT or mutants. Cells were harvested for luciferase/renilla assays at 48 h post-transfection. Data are presented as mean ± SEM of duplicate samples from four independent experiments. *, p<0.05 indicating statistic significance compared to the TNFR2-WT. Arrows indicated that a deletion of domain III or domain II or mutation at the di-leucine motif abolished the JNK activity.

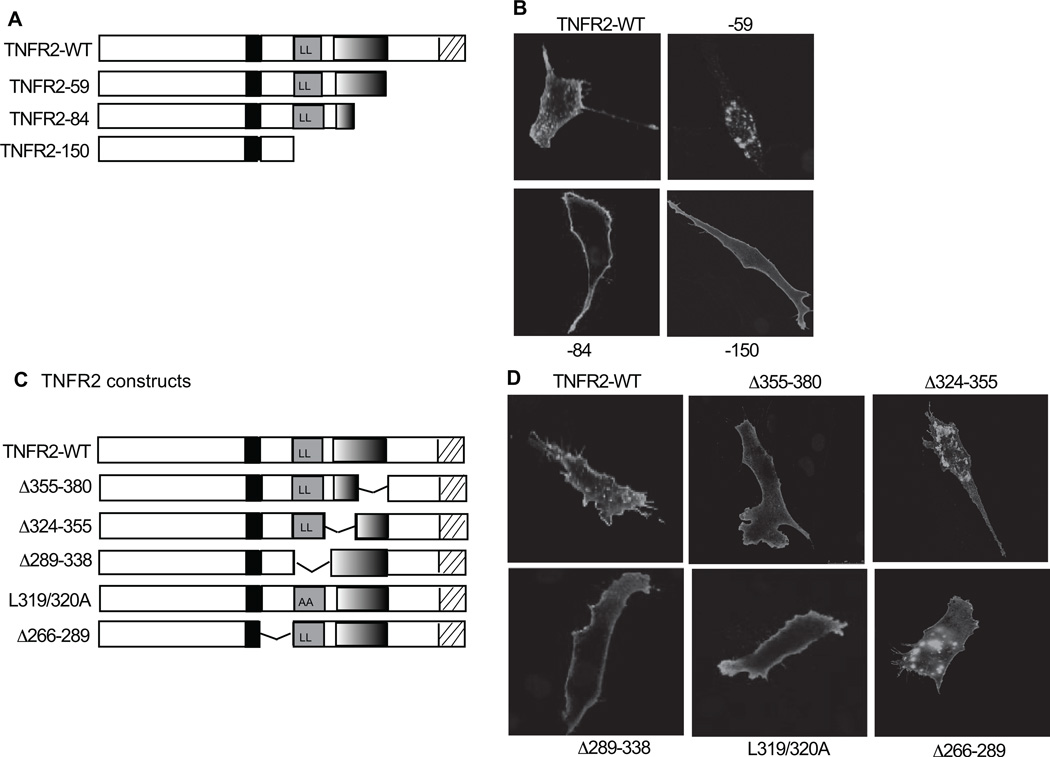

Fig.4. Both domain II and domain III of TNFR2 regulate TNFR2 intracellular localization.

A and C. Schematic structure of TNFR2 truncation and internal deletion are shown. B and D. Effects of truncations and deletions on TNFR2 cellular localization. TNFR2-KO MLEC were transfected with various TNFR2 mutants, and the localization of the TNFR2 protein was determined by indirect fluorescence microscopy with anti-TNFR2 followed by Alexa Fluor-488 donkey anti-goat IgG. TNFR2-KO cells showed no staining (not shown). Representative images from 5 cells for each truncate are shown.

Both domain II and domain III of TNFR2 regulate TNFR2 intracellular localization

The cellular localization of TNFR1 determines its activity in the NF-κB and JNK signaling pathways and in apoptosis13, 14, 16. The results that mutations of the di-leucine motif diminished TNFR2-dependent JNK but not NF-κB activity prompted us to examine TNFR2 localization. TNFR2-WT, upon expression into TNFR2-KO MLEC, exhibited both cytoplasmic membrane and intracellular localizations. Deletions of the TRAF2/Bmx motifs (−59) enhanced TNFR2 intracellular localization (Fig.4A,B), indicating that the TRAF2 (and Bmx)-binding sites are required to maintain TNFR2 on the membrane. Internalized TNFR2 was detected in intracellular vesicles, where it co-localized with the endocytic marker GFP-FYVE-1, containing two tandem-arranged FYVE domains of the late endosomal protein Hrs27 (Supplemental Fig.II). To our surprise, a further deletion of domain III (TNFR2-84) was sufficient to block TNFR2 intracellular vesicle staining, even in the presence of the di-leucine motif (Fig.4B). This result was confirmed using the internal deletion mutants (Fig.4C,D). An internal deletion of aa355-380 drastically reduced TNFR2 intracellular staining. In contrast, deletion of domain I (aa266-289) or the first half of domain III (aa324-355) did not block TNFR2 internalization. As controls, a deletion or a mutation at the di-leucine motif (Δ289-338 and L319/320A, respectively) caused a loss of intracellular vesicle localization of the TNFR2 protein. These data suggest that both the di-leucine motif of domain II and aa355-380 within domain III are required for TNFR2 internalization.

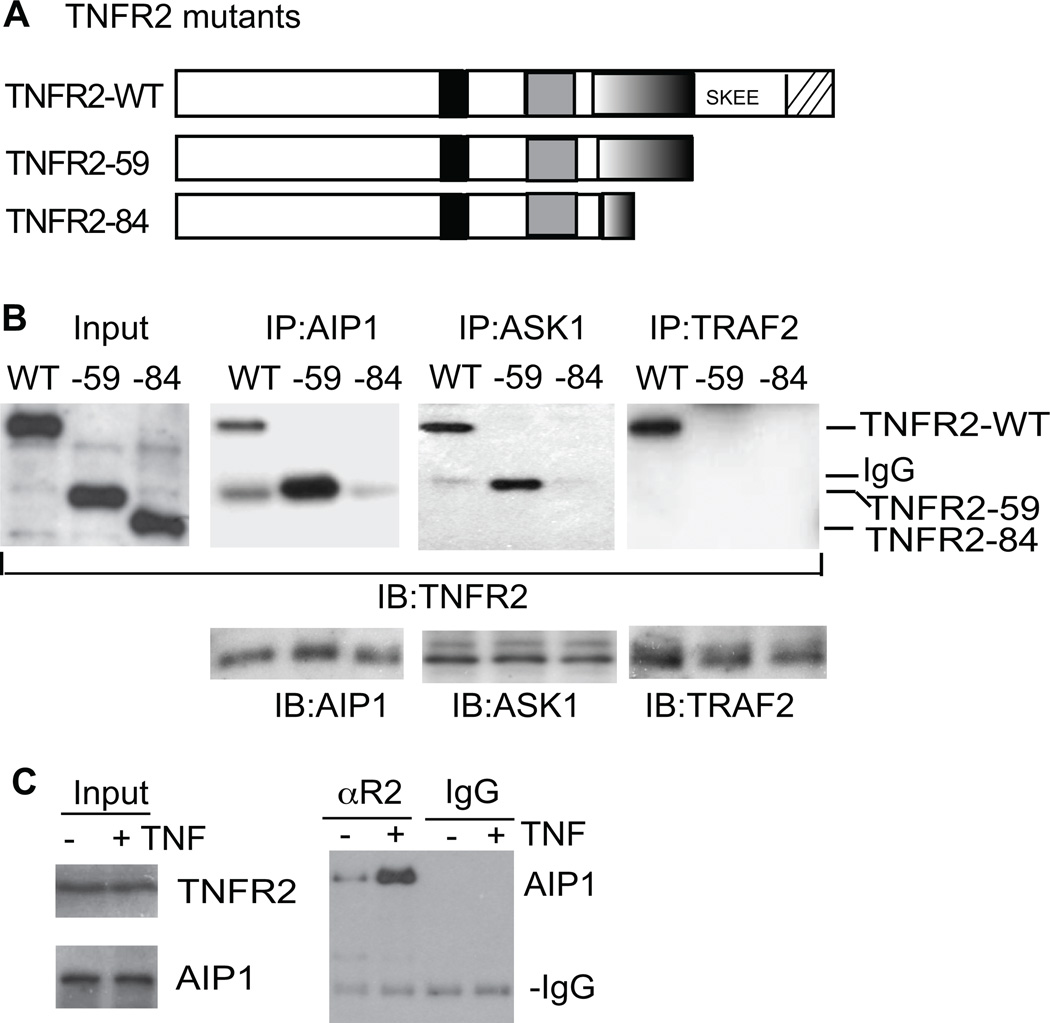

Domain III of TNFR2 is critical for the association with AIP1, an adaptor molecule for JNK activation

Since aa355-380 of domain III specifically mediates TNFR2-induced JNK but not NF-κB activation, we reasoned that it may be required for its association with JNK-specific intracellular signaling molecules. AIP1 is an adaptor molecule mediating JNK but not NF-κB activation in EC15–17, and therefore we examined if TNFR2 via its domain III associated with AIP1. To this end, AIP1-WT, TNFR2-59 and TNFR2-84 (Fig.5A) were expressed in TNFR2-KO MLEC, and association of TNFR2 with endogenous AIP1 was determined by immunoprecipitation with anti-AIP1 followed by Western blot with anti-TNFR2. Association of TNFR2 with TRAF2 was used as a control. As expected, TNFR2-WT, but not TNFR2-59 or TNFR2-84, strongly associated with TRAF2. In contrast, both TNFR2-WT and TNFR2-59 associated with AIP1, and TNFR2-59 exhibited much stronger AIP1 binding than TNFR2-WT (Fig.5B), correlating with its prominent intracellular localization and higher activity in JNK signaling. A deletion of domain III (TNFR2-84) abolished the AIP1 binding. Similar results were observed for association of TNFR2 with the AIP1 effector ASK1 (Fig.5B), an upstream MAP3K in JNK activation.

Fig.5. Domain III of TNFR2 is critical for the association with AIP1, an adaptor molecule for JNK activation.

A. Schematic structure of TNFR2-WT, −59 and −84 are shown. B. TNFR2-KO MLEC were transfected with TNFR2 mutants. Association of TNFR2 with AIP1, ASK1 and TRAF2 was determined by co-immunoprecipitation with the respective antibodies followed by immunoblotting with anti-TNFR2. C. Association of endogenous TNFR2 and AIP1 in response to TNF. HUVEC were untreated or treated with human TNF (10 ng/ml) for 15 min. TNFR2 and AIP1 in the lysates were detected by immunoblotting with respective antibodies. Association of endogenous TNFR2 with AIP1 was determined by co-immunoprecipitation with anti-TNFR2 (αR2) followed by immunoblotting with anti-AIP1. Immunoprecipitation with a goat IgG isotype was used as a control.

We then determined if endogenous TNFR2 and AIP1 proteins form a complex in EC. HUVEC were untreated or treated with TNF (10 ng/ml for 15 min), and association of TNFR2 with AIP1 was determined in a co-immunoprecipitation assay. TNFR2 associated with AIP1 in resting EC and this association was increased in response to TNF (Fig.5C). We also examined interactions of TNFR2 and AIP1 in EC by a co-localization assay. Co-localization of TNFR2 and AIP1 was detected in untreated cells, primarily on the cytoplasmic membrane. However, TNF treatment enhanced their co-localization in intracellular vesicles (Supplemental Fig.III). Taken together, these data suggest that TNFR2 via its domain III binds to AIP1 (and its effector ASK1) to activate the JNK signaling.

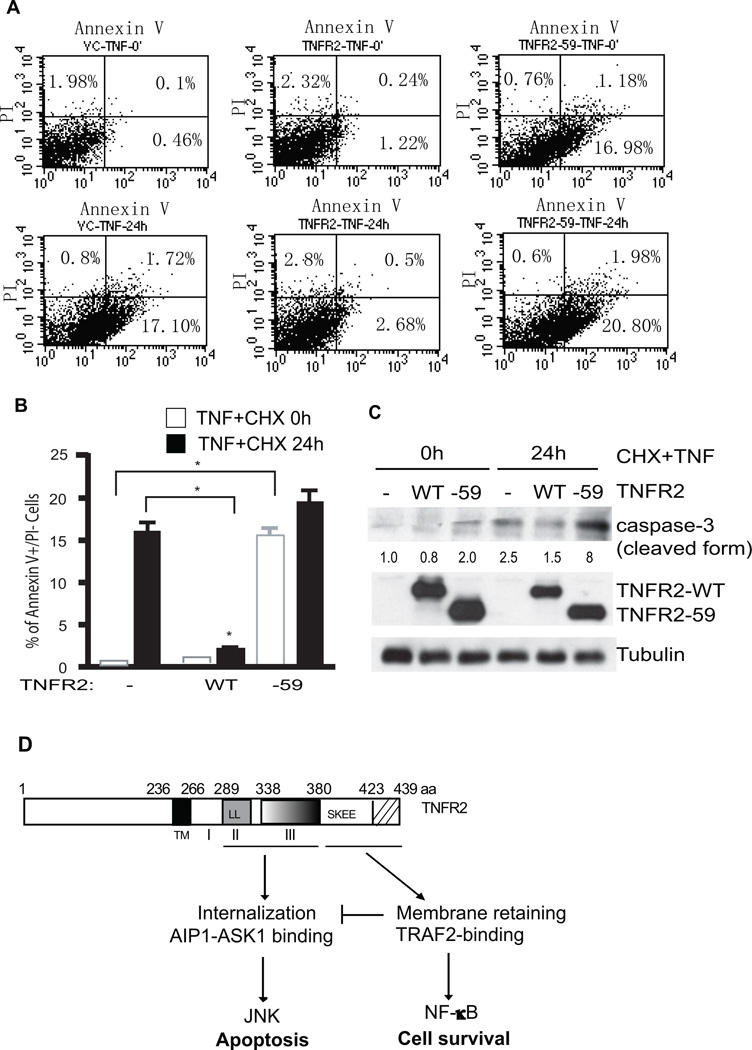

TNFR2-WT inhibits, whereas TNFR2-59 augments, TNF-induced cell apoptosis

JNK signaling has been implicated in cell apoptosis by activating caspase-dependent pathways28, 29. Since TNFR2-59 specifically activates JNK but not the NF-κB survival pathway, we used it to determine the cellular function of TNFR2-dependent JNK signaling and JNK-dependent apoptosis in EC. EC are normally resistant to cytotoxic actions of TNF due to NF-κB induced gene expression of anti-apoptotic proteins that inhibit cell death by both the caspase and the JNK pathways. To potentiate TNF-mediated EC death, TNF is provided in combination with either a global inhibitor of new gene transcription (such as actinomycin D) or of protein synthesis (such as cycloheximide or shiga-like toxin) or in combination with a selective inhibitor of NF-κB activation1, 2. To this end, TNFR2-KO MLEC were infected with lentivirus to express TNFR2-WT or TNFR2-59, and cells were treated with an apoptotic stimulus (TNF plus a protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide). Cell apoptosis was determined by annexin V/propidium iodide (PI) staining followed by flow cytometry analysis. Expression of TNFR2-WT significantly blocked TNF+CHX-induced apoptosis, consistent with its activity in NF-κB survival signaling. In contrast, expression of TNFR2-59 strongly induced EC apoptosis, even in the absence of the apoptotic stimulus. The TNFR-59-induced responses were further augmented by TNF+CHX treatment (Fig.6A, with quantification in Fig.6B). Similar results were obtained by detection of caspase-3 activation as measured for caspase-3 cleavage (Fig.6C). These data suggest that TNFR2-dependent JNK activity contributes to EC apoptosis.

Fig.6. TNFR2-WT inhibits, whereas TNFR2-59 augments, TNF-induced cell apoptosis.

A–B. TNFR2-KO MLEC were infected with lentivirus expressing a control gene LacZ, TNFR2-WT or TNFR2-59. 48 h post-infection, cells were treated with TNF (10 ng/ml) plus cycloheximide (CHX, 10 µg/ml) for 6h. Apoptosis was determined by FACS analysis with FITC-conjugated annexin V (X-axis) and propidium iodide (PI, Y-axis). The numbers indicate % of cell population in each quadruplet. Lower left: normal cells; upper left: necrotic cells; lower right: apoptotic cells; upper right: late apoptotic cells. Quantification of apoptotic (annexin V-positive, both upper and lower right quadruplets in FACS) are shown in B. Data presented are means (±SEM) of three independent experiments. *, p<0.05. C. Caspase-3 activation was measured by immunoblotting with an antibody that recognizes a cleaved form of caspase-3. Densitometry quantifications were indicated, with untreated control as 1.0. Expression of TNFR2-WT and TNFR2-59 was determined by immunoblotting with anti-TNFR2. D. A summary for TNFR2-mediated signaling. TNFR2 via the TRAF2-binding sites recruits TRAF2 to activate NF-κB survival signaling. Domain II and domain III are required for TNFR2 internalization and AIP1-ASK1 association, leading to activation JNK and apoptosis.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we have made several important findings. First, TNFR2 significantly contributes to TNF-induced NF-κB and JNK signaling in vascular EC. This is based on the studies using primary vascular EC with TNFR2 deletion or knockout. Second, by re-expressing various TNFR2 mutants into TNFR2-KO EC, we have identified the critical domains of TNFR2 involved in TNFR2-mediated NF-κB and JNK signaling (Fig.6D). Specifically, the C-terminal 59 residues (aa 380–439) containing the TRAF2- and Bmx-binding sites are essential for NF-κB activation; the adjacent domain II (aa 289–338) and domain III (aa 338–380) are critical for JNK activation; and the membrane proximal domain I is dispensable for both NF-κB and JNK signaling. Third, TNFR2 cellular localization correlates with its activity in NF-κB and JNK signaling. While the TRAF2/Bmx-binding sites are required for its localization on the membrane and its ability to activate NF-κB, the di-leucine motif within domain II and aa355-380 within domain III of TNFR2 are required for its internalization and its ability to activate JNK. We further show that the TNFR2 domain III is required for its association with the JNK-specific signaling molecule AIP1, providing the molecular basis for its role in JNK activation. Finally, we demonstrate that TNFR2-mediated NF-κB activity is associated with cell survival while the JNK signaling is involved in EC apoptosis.

One surprising finding in our study is that the TRAF2-binding sites are not required for, in fact inhibits, TNFR2-mediated JNK activation. The C-terminal TNFR2 contains two TRAF2-binding sites, one is the canonical TRAF2 motif (SKEE) which has been shown to be critical for TRAF2 binding and NF-κB activation. The second site, overlapping with the Bmx-binding sequence, is located at the C-terminal 16 aa residues. The role of this second TRAF2-binding site in TNFR2-mediated NF-κB signaling has also been characterized22, 23. However, the mechanism by which TNFR2 induces JNK activation has not been investigated. Our present study suggests that a deletion of both TRAF2-binding sites (TNFR2-59) diminishes TNFR2-mediated NF-κB but augments TNFR2-mediated JNK signaling. Based on previous and current findings, we propose the following possible models by which the TRAF2-binding sites inhibit TNFR2-mediated JNK signaling. 1) The TRAF2-binding sites regulate TNFR2 intracellular localization. The TRAF2/Bmx-binding sites appear to be important in maintaining TNFR2 on the plasma membrane, leading to NF-κB but not JNK activation. However, deletion of this sequence (TNFR2-59) causes TNFR2 intracellular localization and specific JNK activation. Previous work has demonstrated that TRAF2 regulates TNFR2 membrane localization30. It has also been shown that Bmx is localized on the plasma membrane20, 31, 32. It will be interesting to determine if TRAF2 and Bmx proteins cooperatively regulate TNFR2 membrane localization and internalization. 2) NF-κB inhibits JNK signaling. In TNFR1 signaling, NF-κB induces gene expression of anti-apoptotic proteins that inhibit both the JNK and the caspase pathways. The best characterized factor is FLICE inhibitory protein (c-FLIP)33 and A2034, 35. c-FLIP competes with procaspase 8 for binding to FADD and prevents the autocatlytic activation of caspase 8 (and 10) by the TRADD/RIPK1/TRAF2/FADD complex. A20 exhibits both de-ubiquinating and E3 ubibiquitin ligase activities and is thought to remove the signaling scaffold of lysine 48-linked ubiquitin polymer that forms on RIPK1 as part of the NF-κB and JNK activation pathways, replacing them with a lysine 68-linked ubiquitin polymer that targets RIPK1 for proteosome-mediated degradation34, 36. As a result, both JNK and caspase activation are inhibited. The importance of NF-κB-induced protective proteins is demonstrated by the potentiation of TNF-mediated EC death when TNF is provided in combination with either a global inhibitor of new gene transcription (such as actinomycin D) or of protein synthesis (such as cycloheximide or shiga-like toxin) or in combination with a selective inhibitor of NF-κB activation. 3) Our recent data suggest that TRAF2/RIPK1 in TNFR1 complex I recruits IKK, which could prevent TRAF2/RIPK1 from association with AIP1, therefore inhibiting AIP1-mediated JNK activation (Min,W., unpublished data). It is conceivable that in TNFR2 signaling pathway TRAF2-dependent NF-κB inhibits TNFR2-mediated JNK signaling by similar mechanisms.

TNFR1 endocytosis has been extensively investigated37. A TNFR1-internalization domain (TRID), comprised of the YxxW internalization motif in the cytoplasmic tail of TNFR1, has been identified and implicated in mediating endocytosis of TNFR114, 37. Caveolae also regulate TNFR1 endocytosis and signaling38, 39. In the present study, we have identified two sequences (the di-leucine motif within the domain II and aa355-380 within domain III) on TNFR2 that regulate both TNFR2 internalization and TNFR2-dependent JNK activation. TNFR2 contains a di-leucine motif, a typical sequence associated with clathrin-dependent endocytosis. A site-specific mutation at this motif (L319/320A) blocks TNFR2 internalization but has no effect on TNFR2-mediated NF-κB signaling. However, TNFR2-L319/320A abolishes TNFR2-induced JNK activation. These data suggest that TNFR2, like TNFR113, initiates NF-κB signaling on the plasma membrane while activates JNK upon internalization. It is intriguing that aa355-380 within domain III, containing no known consensus sequence(s) associated with endocytosis, is also required for TNFR2 intracellular localization as well as TNFR2-dependent JNK activation. We have uncovered that aa355-380 within the domain III of TNFR2 is required for its association with AIP1, an intracellular adaptor molecule specific for JNK signaling. Of note, JNK inhibition had no effects on the cellular localization of TNFR2-WT or TNFR2-59, a mutant TNFR2 exhibits strong internalization and JNK activation (Supplemental Fig.IV). These data suggest that JNK activation is likely a consequence of TNFR2 internalization. Interestingly, the domain III of TNFR2 contains serine/threonine-rich sequences which are potentially phosphorylated23. We have previously shown that AIP1 via one of the poly-lysine clusters binds to a serine-rich sequence on ASK115. It is conceivable that internalized TNFR2 via serine/threonine-rich sequences forms a complex with AIP1, leading to JNK activation.

What is the in vivo relevance of the TNFR2-mediated JNK signaling? Dr. DiCorleto’s lab has shown that TNFR2 is essential for TNF-induced E-selectin, vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1), and intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) expression as well as for TNF-induced leukocyte-endothelial-cell interaction in vivo. More importantly, TNFR2 is also required for progression of atherosclerosis in mouse models40, 41. It is conceivable that TNFR2-mediated NF-κB and JNK synergistically regulate expression of the adhesion molecules as we demonstrated previously42. TNFR2-mediated JNK activation could be detected in ischemic hindlimb at day 3 postsurgery, correlating with ischemia-induced apoptosis. This transient JNK activation under ischemia is likely due to decreased expression of TRAF2 in response to ischemia7, 8. The JNK activation and cellular apoptosis may be an early event during the adaptive response, which is required for revascularization and ischemic tissue regeneration7, 8. Therefore, modulation of TNFR2-mediated JNK signaling in EC may provide a novel strategy for the treatment of vascular diseases such as atherosclerosis, coronary artery disease and peripheral arterial disease.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Acknowledgements: We thank Dr. Jordan S. Pober for discussion.

Source of funding: This work was supported by grants from NIH grants R01HL65978 and R01HL109420.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure: None.

REFERENCE

- 1.Pober JS, Min W. Endothelial cell dysfunction, injury and death. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2006:135–156. doi: 10.1007/3-540-36028-x_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pober JS, Min W, Bradley JR. Mechanisms of Endothelial Dysfunction, Injury, and Death. Annu Rev Pathol. 2009;4:71–95. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.4.110807.092155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Locksley RM, Killeen N, Lenardo MJ. The TNF and TNF receptor superfamilies: integrating mammalian biology. Cell. 2001;104:487–501. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00237-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fiers W, Beyaert R, Boone E, Cornelis S, Declercq W, Decoster E, Denecker G, Depuydt B, De Valck D, De Wilde G, Goossens V, Grooten J, Haegeman G, Heyninck K, Penning L, Plaisance S, Vancompernolle K, Van Criekinge W, Vandenabeele P, Vanden Berghe W, Van de Craen M, Vandevoorde V, Vercammen D. TNF-induced intracellular signaling leading to gene induction or to cytotoxicity by necrosis or by apoptosis. J Inflamm. 1995;47:67–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wallach D, Varfolomeev EE, Malinin NL, Goltsev YV, Kovalenko AV, Boldin MP. Tumor necrosis factor receptor and Fas signaling mechanisms. Annu Rev Immunol. 1999;17:331–367. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carpentier I, Coornaert B, Beyaert R. Function and regulation of tumor necrosis factor type 2. Curr Med Chem. 2004;11:2205–2212. doi: 10.2174/0929867043364694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luo D, Luo Y, He Y, Zhang H, Zhang R, Li X, Dobrucki WL, Sinusas AJ, Sessa WC, Min W. Differential functions of tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 and 2 signaling in ischemia-mediated arteriogenesis and angiogenesis. Am J Pathol. 2006;169:1886–1898. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.060603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luo Y, Wan T, He Y, Xu Z, Jones D, Zhang H, Min W. Endothelial-Specific Transgenesis of TNFR2 Promotes Adaptive Arteriogenesis and Angiogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:1307–1314. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.204222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wajant H, Scheurich P. TNFR1-induced activation of the classical NF-kappaB pathway. Febs J. 2011;278:862–876. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hsu H, Shu HB, Pan MG, Goeddel DV. TRADD-TRAF2 and TRADD-FADD interactions define two distinct TNF receptor 1 signal transduction pathways. Cell. 1996;84:299–308. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80984-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rothe M, Wong SC, Henzel WJ, Goeddel DV. A novel family of putative signal transducers associated with the cytoplasmic domain of the 75 kDa tumor necrosis factor receptor. Cell. 1994;78:681–692. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90532-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stanger BZ, Leder P, Lee TH, Kim E, Seed B. RIP: a novel protein containing a death domain that interacts with Fas/APO-1 (CD95) in yeast and causes cell death. Cell. 1995;81:513–523. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90072-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Micheau O, Tschopp J. Induction of TNF receptor I-mediated apoptosis via two sequential signaling complexes. Cell. 2003;114:181–190. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00521-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schneider-Brachert W, Tchikov V, Neumeyer J, Jakob M, Winoto-Morbach S, Held-Feindt J, Heinrich M, Merkel O, Ehrenschwender M, Adam D, Mentlein R, Kabelitz D, Schutze S. Compartmentalization of TNF receptor 1 signaling: internalized TNF receptosomes as death signaling vesicles. Immunity. 2004;21:415–428. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang R, He X, Liu W, Lu M, Hsieh JT, Min W. AIP1 mediates TNF-alpha-induced ASK1 activation by facilitating dissociation of ASK1 from its inhibitor 14-3-3. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1933–1943. doi: 10.1172/JCI17790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang H, Zhang R, Luo Y, D'Alessio A, Pober JS, Min W. AIP1/DAB2IP, a novel member of the Ras-GAP family, transduces TRAF2-induced ASK1-JNK activation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:44955–44965. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407617200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang H, Zhang H, Lin Y, Li J, Pober JS, Min W. RIP1-mediated AIP1 phosphorylation at a 14-3-3-binding site is critical for tumor necrosis factor-induced ASK1-JNK/p38 activation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:14788–14796. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701148200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Naude PJ, den Boer JA, Luiten PG, Eisel UL. Tumor necrosis factor receptor cross-talk. FEBS J. 2011;278:888–898. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rothe M, Pan MG, Henzel WJ, Ayres TM, Goeddel DV. The TNFR2-TRAF signaling complex contains two novel proteins related to baculoviral inhibitor of apoptosis proteins. Cell. 1995;83:1243–1252. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90149-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pan S, An P, Zhang R, He X, Yin G, Min W. Etk/Bmx as a tumor necrosis factor receptor type 2-specific kinase: role in endothelial cell migration and angiogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:7512–7523. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.21.7512-7523.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Al-Lamki RS, Wang J, Vandenabeele P, Bradley JA, Thiru S, Luo D, Min W, Pober JS, Bradley JR. TNFR1- and TNFR2-mediated signaling pathways in human kidney are cell type-specific and differentially contribute to renal injury. Faseb J. 2005;19:1637–1645. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-3841com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grech AP, Gardam S, Chan T, Quinn R, Gonzales R, Basten A, Brink R. Tumor necrosis factor receptor 2 (TNFR2) signaling is negatively regulated by a novel, carboxyl-terminal TNFR-associated factor 2 (TRAF2)-binding site. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:31572–31581. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504849200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rodriguez M, Cabal-Hierro L, Carcedo MT, Iglesias JM, Artime N, Darnay BG, Lazo PS. NF-kappaB signal triggering and termination by tumor necrosis factor receptor 2. J BIOL CHEM. 2011;286:22814–22824. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.225631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marchetti L, Klein M, Schlett K, Pfizenmaier K, Eisel UL. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-mediated neuroprotection against glutamate-induced excitotoxicity is enhanced by N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor activation. Essential role of a TNF receptor 2-mediated phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-dependent NF-kappa B pathway. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:32869–32881. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311766200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rauert H, Wicovsky A, Muller N, Siegmund D, Spindler V, Waschke J, Kneitz C, Wajant H. Membrane tumor necrosis factor (TNF) induces p100 processing via TNF receptor-2 (TNFR2) J Biol Chem. 2010;285:7394–7404. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.037341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fischer R, Maier O, Naumer M, Krippner-Heidenreich A, Scheurich P, Pfizenmaier K. Ligand-induced internalization of TNF receptor 2 mediated by a di-leucin motif is dispensable for activation of the NFkappaB pathway. Cell Signal. 2011;23:161–170. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2010.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen H, De Camilli P. The association of epsin with ubiquitinated cargo along the endocytic pathway is negatively regulated by its interaction with clathrin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:2766–2771. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409719102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tournier C, Hess P, Yang DD, Xu J, Turner TK, Nimnual A, Bar-Sagi D, Jones SN, Flavell RA, Davis RJ. Requirement of JNK for stress-induced activation of the cytochrome c-mediated death pathway. Science. 2000;288:870–874. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5467.870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang R, Al-Lamki R, Bai L, Streb JW, Miano JM, Bradley J, Min W. Thioredoxin-2 inhibits mitochondria-located ASK1-mediated apoptosis in a JNK-independent manner. Circ Res. 2004;94:1483–1491. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000130525.37646.a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feng X, Gaeta ML, Madge LA, Yang JH, Bradley JR, Pober JS. Caveolin-1 associates with TRAF2 to form a complex that is recruited to tumor necrosis factor receptors. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:8341–8349. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007116200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vargas L, Nore BF, Berglof A, Heinonen JE, Mattsson PT, Smith CI, Mohamed AJ. Functional interaction of caveolin-1 with Bruton's tyrosine kinase and Bmx. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:9351–9357. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108537200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones D, Xu Z, Zhang H, He Y, Kluger MS, Chen H, Min W. Functional Analyses of the Nonreceptor Kinase Bone Marrow Kinase on the X Chromosome in Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor-Induced Lymphangiogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010 doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.214999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kreuz S, Siegmund D, Scheurich P, Wajant H. NF-kappaB inducers upregulate cFLIP, a cycloheximide-sensitive inhibitor of death receptor signaling. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:3964–3973. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.12.3964-3973.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wertz IE, O'Rourke KM, Zhou H, Eby M, Aravind L, Seshagiri S, Wu P, Wiesmann C, Baker R, Boone DL, Ma A, Koonin EV, Dixit VM. De-ubiquitination and ubiquitin ligase domains of A20 downregulate NF-kappaB signalling. Nature. 2004;430:694–699. doi: 10.1038/nature02794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Slowik MR, Min W, Ardito T, Karsan A, Kashgarian M, Pober JS. Evidence that tumor necrosis factor triggers apoptosis in human endothelial cells by interleukin-1-converting enzyme-like protease- dependent and -independent pathways. Lab Invest. 1997;77:257–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heyninck K, Beyaert R. A20 inhibits NF-kappaB activation by dual ubiquitin-editing functions. Trends Biochem Sci. 2005;30:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schutze S, Tchikov V, Schneider-Brachert W. Regulation of TNFR1 and CD95 signalling by receptor compartmentalization. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:655–662. doi: 10.1038/nrm2430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.D'Alessio A, Al-Lamki RS, Bradley JR, Pober JS. Caveolae participate in tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 signaling and internalization in a human endothelial cell line. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:1273–1282. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62346-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.D'Alessio A, Kluger MS, Li JH, Al-Lamki R, Bradley JR, Pober JS. Targeting of tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 to low density plasma membrane domains in human endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:23868–23879. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.122853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chandrasekharan UM, Mavrakis L, Bonfield TL, Smith JD, DiCorleto PE. Decreased atherosclerosis in mice deficient in tumor necrosis factor-alpha receptor-II (p75) Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:e16–e17. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000255551.33365.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chandrasekharan UM, Siemionow M, Unsal M, Yang L, Poptic E, Bohn J, Ozer K, Zhou Z, Howe PH, Penn M, DiCorleto PE. Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-alpha) receptor-II is required for TNF-alpha-induced leukocyte-endothelial interaction in vivo. Blood. 2007;109:1938–1944. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-020875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Min W, Pober JS. TNF initiates E-selectin transcription in human endothelial cells through parallel TRAF-NF-kappa B and TRAF-RAC/CDC42-JNK-c-Jun/ATF2 pathways. J Immunol. 1997;159:3508–3518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.