Abstract

Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) expression is induced by mitogenic and proinflammatory factors. Its overexpression plays a causal role in inflammation and tumorigenesis. COX-2 expression is tightly regulated, but the mechanisms are largely unclear. Here we show the control of COX-2 expression by an endogenous tryptophan metabolite, 5-methoxytryptophan (5-MTP). By using comparative metabolomic analysis and enzyme-immunoassay, our results reveal that normal fibroblasts produce and release 5-MTP into the extracellular milieu whereas A549 and other cancer cells were defective in 5-MTP production. 5-MTP was synthesized from l-tryptophan via tryptophan hydroxylase-1 and hydroxyindole O-methyltransferase. 5-MTP blocked cancer cell COX-2 overexpression and suppressed A549 migration and invasion. Furthermore, i.p. infusion of 5-MTP reduced tumor growth and cancer metastasis in a murine xenograft tumor model. We conclude that 5-MTP synthesis represents a mechanism for endogenous control of COX-2 overexpression and is a valuable lead for new anti-cancer and anti-inflammatory drug development.

Keywords: tumor suppression, tryptophan metabolism, inflammation control

Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) is a rate-limiting enzyme in the production of diverse prostanoids with potent biological activities. It is involved in multiple physiological functions and triggers key pathological processes, such as tumorigenesis and inflammation (1, 2). COX-2 is constitutively overexpressed in a wide variety of human cancers and is enhanced by proinflammatory stimuli (3, 4). There is convincing evidence for a causal role of COX-2 in tumorigenesis. Inhibition of COX-2 activities was reported to control human colorectal cancer (5–8). COX-2 induces tumorigenesis by promoting important cellular functions including cell proliferation, migration, and resistance to apoptosis (9–11). The induced COX-2 expression by proinflammatory and mitogenic factors in normal cells is tightly controlled (12) whereas its overexpression in cancer cells is attributed to dysregulated transcription (13). The endogenous control mechanisms for COX-2 expression in normal cells and the mechanisms underlying the dysregulation in cancer cells are poorly understood. We previously identified in the conditioned medium of human fibroblasts small molecules (named cytoguardins) that suppress COX-2 expression induced by proinflammatory mediators (14). NMR analysis of a semipurified fraction revealed compounds with indole moieties (14). However, the exact chemical structures remain elusive. In this study, we elucidated the structure of cytoguardins by comparing the metabolomic profiles between normal and cancer cells.

Results

Cytoguardins Inhibit Cancer Cell COX-2.

To determine that fibroblast factors are capable of suppressing cancer cell COX-2 expression, we cocultured human Hs68 foreskin fibroblasts (HsFb) with A549 lung cancer cells in a Boyden chamber for 24 h. A549 cells were removed and treated with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) for 4 h, and COX-2 proteins were analyzed. HsFb suppressed A549 COX-2 expression in a cell-density–dependent manner (Fig. 1A). To ensure that inhibition of A549 COX-2 is attributable to HsFb factors, we added conditioned medium (CM) collected from proliferative HsFb to washed A549 cells and analyzed COX-2 expression. PMA induced robust expression of COX-2 in A549 cells, which was suppressed by HsFb CM but not by control medium (Fig. 1B). By contrast, A549 CM did not inhibit PMA-induced COX-2 expression in serum-starved HsFb (Fig. 1B). Conditioned medium prepared from other types of human fibroblasts inhibited PMA-induced A549 COX-2 expression (Fig. S1A). Conditioned medium of MCF10A (breast epithelial cell) inhibited COX-2 expression whereas CM of MCF7 (breast cancer cell) as well as other cancer cells did not (Fig. S1B). Taken together, these results indicate that cancer cells are defective in controlling PMA-induced COX-2 expression, which is restored by normal fibroblast and epithelial cell factors.

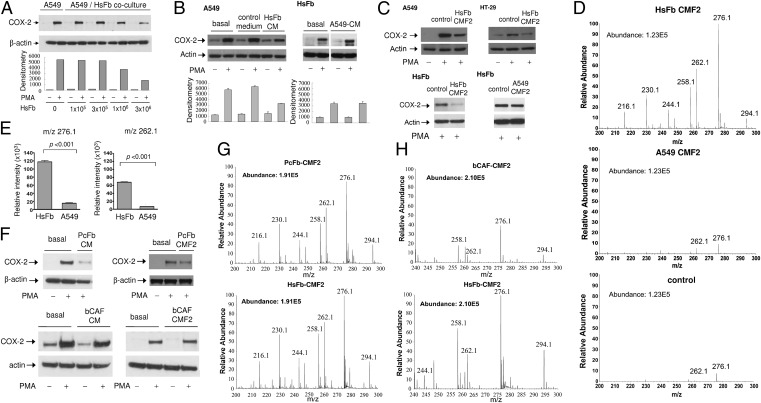

Fig. 1.

Suppression of cancer cell COX-2 expression by soluble factors from fibroblasts. (A) A549 lung cancer cells (106 cells) were cocultured with HsFb at various cell densities in a Boyden chamber for 24 h. A549 cells were removed and treated with PMA (100 nM) for 4 h. COX-2 proteins in the cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting. (B) Conditioned medium (CM) was collected from Hs68 fibroblasts (HsFb) or A549 cells cultured in medium containing 2.5% FBS for 24 h. (Left) HsFb CM was added to washed A549 cells. (Right) A549 CM was added to washed serum-starved Hs68 fibroblasts. Cells were treated with PMA for 4 h, and COX-2 proteins were analyzed by Western blotting. Error bars denote mean ± SEM (n = 3). (C) CMF2 fractions prepared from HsFb or A549 CM were added to washed A549, HT29, or serum-starved HsFb, and PMA-induced COX-2 was analyzed. CMF2 of HsFb inhibited COX-2 expression whereas CMF2 of A549 had no effect. Two independent experiments were performed with similar results. (D) Representative mass spectra (m/z 0–300) of CMF2 prepared from HsFb or A549. Control denotes F2 fraction of the basal DMEM containing 2.5% FBS. Metabolomic analysis of CMF2 was performed using UPLC–QTof mass spectrometry. (E) Comparison of relative intensity of m/z 276.1 and m/z 262.1 between HsFb CMF2 and A549 CMF2. Error bars denote mean ± SEM (n = 3). (F) Effect of cancer-associated fibroblasts on PMA-induced COX-2 expression in A549 cells. CM and CMF2 prepared from prostate cancer-associated fibroblasts (PcFb) inhibited COX-2 expression whereas neither CM nor CMF2 of breast cancer-associated fibroblasts (bCAF) did. (G and H) The metabolomic profile of (G) PcFb-CMF2 was similar to that of HsFb-CMF2, whereas the profile of (H) bCAF-CMF2 reveals diminished m/z 276.1, m/z 262.1, and other m/z peaks.

In view of the overt difference in COX-2–suppressing activities in the conditioned medium of fibroblasts vs. cancer cells, we reasoned that the chemical structure of cytoguardins may be solved by comparative metabolomic analysis. We prepared partially purified fraction CMF2 from HsFb and A549 CM by a modified procedure (14). CMF2 of HsFb was effective in inhibiting PMA-induced COX-2 expression in cancer cells whereas CMF2 of A549 had no effect on HsFb COX-2 expression (Fig. 1C). HsFb CMF2 inhibited PMA-induced COX-2 promoter activity in A549 whereas A549 CMF2 had no effect (Fig. S2).

Metabolomic Analysis of CMF2.

A high resolution ultraperformance liquid chromatography (UPLC) coupled online to a triple quardrupole-time of flight (QTof) mass spectrometry (MS) system was used to detect differences in the metabolomic profile between HsFb and A549 CMF2. Chromatograph and mass spectra of CMF2 fractions prepared from multiple batches of HsFb and A549 CM were analyzed. There is a distinct difference in the metabolomic profiles between HsFb and A549 (Fig. S3), characterized by increased intensities in HsFb of several peaks between m/z 100 and 300 among which m/z 276.1 and m/z 262.1 are the most prominent (Fig. 1D). Most of the peaks detected in HsFb CMF2 were undetectable or barely detectable in A549 CMF2 (Fig. 1D). In fact, the mass spectra of A549 CMF2 was not significantly different from that of the control CMF2, consistent with the notion that A549 cells are unable to generate cytoguardins. The intensities of m/z 276.1 and m/z 262.1 of HsFb CMF2 were ∼10-fold higher than that of A549 CMF2 (Fig. 1E). The intensity of other peaks such as m/z 294.1, 258.1, 244.1, 230.1, and 216.1 was also significantly higher in HsFb CMF2.

There is increasing evidence that cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) are “educated” by cancer and converted to a phenotype that promotes cancer growth (15–21). However, CAFs are heterogeneous (17, 22), and several reports have shown that fibroblasts inhibit cancer cell proliferation through generation of soluble factors or direct cellular contact (23–25). We were curious whether fibroblasts in cancer are capable of producing cytoguardins. The metabolomic profile of CMF2 of fibroblasts isolated from freshly resected prostate cancer (PcFb)—reported to inhibit cancer cell growth as previously described (25) and from human breast cancer (bCAF) that promotes cancer growth—were analyzed. PcFb CM and CMF2 inhibited PMA-induced COX-2 expression whereas bCAF did not (Fig. 1F). Metabolomic analysis of PcFb CMF2 revealed a mass spectra similar to that of HsFb with comparable intensity of m/z 276.1 and 262.1 (Fig. 1G). By contrast, m/z 276.1 and 262.1 as well as other minor peaks were reduced in the CMF2 of bCAF (Fig. 1H). These results suggest that fibroblasts in human cancers are heterogenous in producing cytoguardins and suppressing COX-2 expression.

5-HTP Pathway Suppresses COX-2.

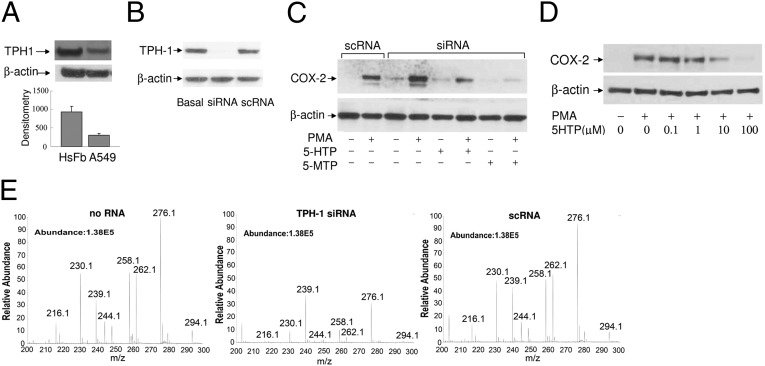

Data from the metabolomic analysis suggest that m/z 276.1 and m/z 262.1 may be involved in COX-2 suppression. Because the NMR analysis has shown that cytoguardins might be indole derivatives, we initially searched the database for indole compounds that fit the chemical characteristics of m/z 276.1 and m/z 262.1. The database listed 5-hydroxytryptophan (5-HTP) conjugated to acetonitrile (CH3CN) as a candidate of m/z 262.1. 5-HTP is synthesized from l-tryptophan (Try) by tryptophan hydroxylase (TPH) and is further metabolized to serotonin and melatonin in neural cells (26, 27). Two TPH isoforms have been identified and characterized. The TPH-2 isoform expression is restricted to neural cells and is a rate-limiting enzyme for serotonin biosynthesis (26–28). TPH-1 has been reported to be expressed in vascular cells (29). However, little is known about its expression and metabolism in fibroblasts and cancer cells. We analyzed its expression by Western blotting. TPH-1 was detected in HsFb and A549 cells, and its level in HsFb was higher than that in A549 cells (Fig. 2A). Knockdown of TPH-1 by specific siRNA (Fig. 2B) resulted in abrogation of COX-2 suppression manifested by an enhanced PMA-induced COX-2 expression, whereas control scramble control RNA (scRNA) did not alter the COX-2 level (Fig. 2C). Loss of COX-2 control in the TPH-1–silenced HsFb was rescued (Fig. 2C) by addition of pure 5-HTP compound (Fig. S4A). Furthermore, 5-HTP was effective in suppressing PMA-induced COX-2 expression in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 2D). These results suggest that the TPH-1 pathway is important in suppressing COX-2 expression. To determine that TPH-1 is directly responsible for generation of m/z 262.1, we prepared CMF2 fractions from HsFb transfected with or without TPH-1 siRNA. Metabolomic analysis of CMF2 from the siRNA-modified HsFb revealed a reduction of m/z 262.1 intensity by siRNA but not by scRNA (Fig. 2E). These results confirm that m/z 262.1 generation depends on TPH-1.

Fig. 2.

Tryptophan hydroxylase (TPH-1)-derived 5-HTP suppresses COX-2 expression. (A) TPH-1 proteins in HsFb vs. A549 cells were analyzed by Western blotting. The error bars refer to mean ± SEM (n = 3). (B) TPH-1 protein levels in siRNA-transfected HsFb vs. control scRNA-transfected HsFb. “Basal” denotes untransfected cells. (C) Analysis of COX-2 proteins in HsFb transfected with TPH-1 siRNA or scRNA. COX-2 was increased in siRNA-treated cells, and COX-2 suppression was restored by 5-HTP (10 μM) or 5-MTP (10 μM) supplement. 5-MTP supplement completely inhibited COX-2 expression whereas 5-HTP partially suppressed COX-2 proteins. (D) HsFb were pretreated with 5-HTP followed by PMA for 4 h. COX-2 proteins were analyzed by Western blotting. (E) Metabolomic analysis of CMF2 prepared from CM of HsFb with or without siRNA or scRNA transfection.

5-Methoxytryptophan Controls COX-2.

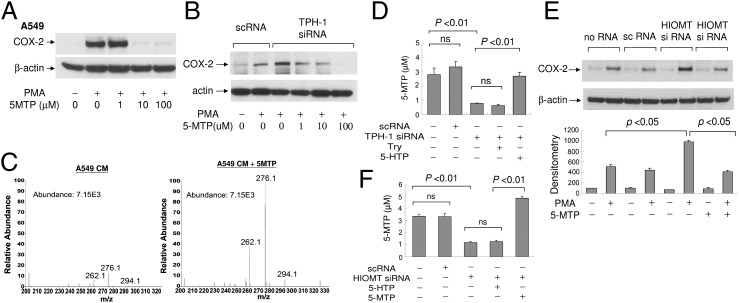

We suspected that the active cytoguardin is derived from 5-HTP and that m/z 276.1 may hold the clue. By searching the database, 5-methoxytryptophan (5-MTP) conjugated to CH3CN was listed as a potential chemical compound that fits m/z 276.1. However, there had been no report of 5-MTP synthesis in mammalian cells or any report on the COX-2–suppressing function of this molecule. To provide supporting evidence, we obtained pure 5-MTP, validated its molecular homogeneity (Fig. S4B), and evaluated its effect on COX-2 expression. 5-MTP completely inhibited PMA-induced COX-2 proteins in A549 cells (Fig. 3A). Furthermore, 5-MTP restored COX-2 suppression in TPH-1–silenced fibroblasts in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 3B). Thus, 5-MTP possesses COX-2–suppressing activity and is capable of correcting the defect in A549 cells. To provide additional evidence for the identity of m/z 276.1, we added 5-MTP to A549 CM and determined whether the intensity of m/z 276.1 in A549 CMF2 is enhanced. The intensity of m/z 276.1 was indeed increased (Fig. 3C). The intensity of m/z 262.1 was also increased, which might be derived from m/z 276.1 via a demethylation reaction.

Fig. 3.

Endogenous and exogenously added 5-MTP inhibits COX-2 expression. (A) Pure 5-MTP at increasing concentrations was added to A549 treated with or without PMA for 4 h. COX-2 proteins were analyzed by Western blotting. (B) 5-MTP restored COX-2 suppression in TPH-1 siRNA-transfected HsFb in a concentration-dependent manner. (C) Addition of 5-MTP to A549 cells enhances m/z 276.1 and 262.1 peaks on mass spectrometry. (D) HsFbs were transfected with TPH-1 siRNA or scRNA. l-Tryptophan (Try) or 5-HTP was added to the transfected cells. Conditioned medium was collected, and 5-MTP concentration was measured by EIA. Each bar denotes mean ± SEM (n = 3). ns, not statistically significant. (E) Analysis of COX-2 proteins by Western blotting in HsFb transfected with HIOMT siRNA or a control scRNA. (Upper) Representative blot. (Lower) Quantitative analysis by densitometry. Error bars denote mean ± SEM (n = 3). Concentration of 5-MTP was 10 μM. (F) Measurement by EIA of 5-MTP in the CM of HsFb under the indicated treatment; 10 μM of 5-HTP or 5-MTP was added. Each error bar denotes mean ± SEM of three independent experiments done in triplicate. ns, not statistically significant.

The identity of 5-MTP was validated by an enzyme-immuno assay (EIA) developed in our laboratory. A linear calibration curve was obtained at the range of 5-MTP concentrations up to 2,000 ng/mL (∼8.6 μM) (Fig. S5). We measured 5-MTP content in the CM of HsFb by EIA. HsFb released ∼3 μM 5-MTP in the CM (Fig. 3D). The 5-MTP level in the CM of HsFb treated with TPH-1 siRNA was reduced to the basal level whereas 5-MTP in HsFb treated with control scRNA was not changed (Fig. 3D). 5-MTP production was restored by adding 5-HTP to TPH-1 siRNA-treated HsFb and was not influenced by Try (Fig. 3D). These results indicate that 5-MTP is generated from 5-HTP via TPH-1 pathway.

Hydroxyindole O-methyltransferase Catalyzes 5-MTP Synthesis.

Conversion of 5-HTP to 5-MTP is likely to be catalyzed by a methyltransferase. We speculated that hydroxyindole O-methyltransferase (HIOMT, EC2.1.1.4) might be involved in 5-MTP synthesis. HIOMT was characterized as an enzyme that catalyzes the final step of melatonin synthesis in pineal gland (30, 31). It transfers methyl group from 5-adenosyl-l-methionine to N-acetyl-5-hydroxytryptamine to form melatonin. The human HIOMT gene has been cloned and sequenced (32). To test the hypothesis, we obtained siRNA based on the human sequence and evaluated its effect on PMA-induced COX-2 expression. HIOMT protein was constitutively expressed in HsFb, and its knockdown in HsFb by siRNA (Fig. S6) resulted in abrogation of COX-2 suppression, which was rescued by 5-MTP (Fig. 3E). To ascertain that HIOMT siRNA transfection blocks 5-MTP production, we measured 5-MTP by EIA in HsFb transfected with siRNA vs. the control scRNA. 5-MTP was reduced to basal level by siRNA and was not affected by scRNA (Fig. 3F). Addition of 5-HTP could not rescue 5-MTP production whereas exogenous addition of 5-MTP restored the level (Fig. 3F). These results confirm the involvement of HIOMT in catalyzing the conversion of 5-HTP to COX-2–suppressing 5-MTP in HsFb.

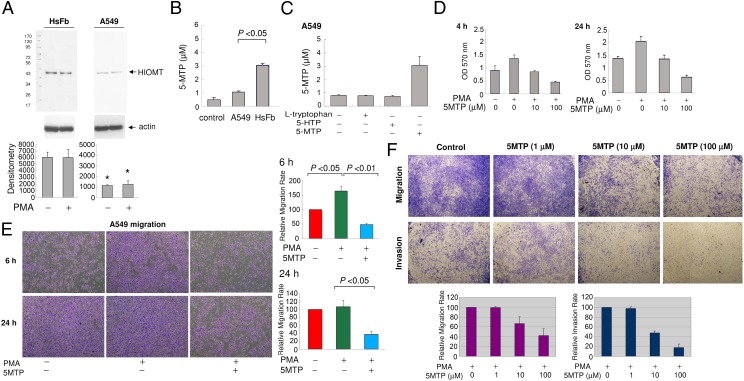

Compared with HsFb, HIOMT protein was barely detectable in A549, which was not affected by PMA (Fig. 4A). Corresponding to the low HIOMT protein expression, 5-MTP level in the A549 CM was low and close to the control level (Fig. 4B). Neither Try nor 5-HTP supplement increased A549 5-MTP (Fig. 4C). Addition of 5-HTP did not suppress PMA-induced COX-2 protein expression in A549 cells (Fig. S7). These results suggest that deficiency of 5-MTP production in A549 may be due to defective expression of HIOMT.

Fig. 4.

5-MTP rescues A549 defects in 5-MTP synthesis and cell proliferation and migration. (A) Analysis of HIOMT proteins in A549 vs. HsFb. (Upper) Representative blot. (Lower) Densitometric analysis of three independent experiments. The error bars are mean ± SEM (*P < 0.01). (B) Measurement of 5-MTP level in A549 vs. HsFb CM. Error bars are mean ± SEM (n = 3). (C) Neither Try nor 5-HTP increased A549 5-MTP production, whereas addition of exogenous 5-MTP increased the 5-MTP level measured by EIA. The error bars are mean ± SEM (n = 3). (D) A549 cells labeled with MTT were treated with 5-MTP for 4 or 24 h. Each bar denotes mean ± SEM (n = 3). (E) A549 cells were pretreated with 5-MTP (10 μM) for 30 min followed by PMA (100 nM) for 6 or 24 h. (Upper panels) Representative cell migration. (Lower panels) Migrated cell counts expressed as percentage of basal controls. Error bars denote mean ± SEM (n = 3). (F) A549 cells were seeded on regular or matrigel-coated membrane and pretreated with 5-MTP for 30 min followed by PMA. (Upper) Representative cell migration and invasion. (Lower panels) Quantitative analysis of migration and invasion.

5-MTP Blocks Cancer Growth and Metastasis.

Because COX-2 overexpression in cancer cells is attributed to 5-MTP deficiency, we determined whether 5-MTP corrects cancer cell proliferation and invasion. We evaluated the effect of 5-MTP on A549 viability and proliferation by methylthiazole tetrazolium (MTT) assay. 5-MTP suppressed A549 cell proliferation (Fig. 4D). Furthermore, it abrogated PMA-induced cell migration in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 4 E and F). To determine whether 5-MTP inhibits A549 invasion, we seeded A549 onto matrigel-coated surface and analyzed PMA-induced A549 invasion through the matrigel at 24 h. 5-MTP inhibited A549 cell invasion (Fig. 4F).

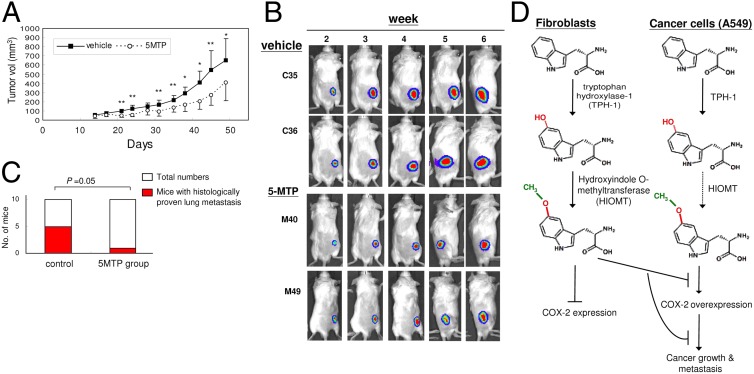

To confirm the anti-cancer property of 5-MTP in vivo, we evaluated the effect of 5-MTP on A549 tumor formation in a xenograft tumor model. A549 cells stably transfected with luciferase (A549-luc-c8, 5 × 106 cells) were injected s.c. into the flank of SC1D-Beige mice. Tumor growth was analyzed by caliper measurement of tumor volume and in vivo bioluminescent imaging using a cooled CCD camera. 5-MTP or vehicle was administered intraperitoneally twice weekly, and tumor volume was measured twice weekly for 7 wk. 5-MTP suppressed tumor volume in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 5A). The average tumor volume at 7 wk in the 5-MTP–treated group was ∼50% of that in the control group. Results of bioluminescence imaging are consistent with reduction of tumor growth, as illustrated in Fig. 5B. To determine whether 5-MTP suppresses A549 cancer metastasis, we euthanized mice on day 52 and examined lungs for metastatic nodules. Multiple small nodules were detected on the lung surface in 5 of the 10 mice in the vehicle group and in only 1 of the 10 mice receiving 5-MTP (Fig. 5C). Numbers of nodules ranged from 6 to 28 (Fig. S8). Histological examination of H&E-stained lung specimen confirmed metastatic cancer cells in all of the nodules as illustrated in Fig. S9. Thus, 5-MTP treatment significantly attenuated cancer metastasis to the lungs. Taken together, these results indicate that the 5-MTP inhibits cancer cell proliferation, migration, and invasiveness in vitro and cancer growth and metastasis in vivo.

Fig. 5.

5-MTP reduces cancer growth and metastasis in a murine tumor xenograft model. A549 (5 × 106 cells) were transfected with luciferase (A549-luc-c8) and injected s.c. into the flank of SCID-Beige mice. Ten mice each received i.p. injection of 5-MTP (100 mg/kg) or vehicle twice weekly. (A) Caliper measurement of the s.c. tumor volume periodically for 7 wk. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01. (B) Tumor growth was monitored by in vivo bioluminescent imaging (IVIS). The time courses of IVIS of two representative vehicle-treated and two representative 5-MTP–treated mice are illustrated. (C) 5-MTP reduces lung metastasis. Mice were euthanized and both lungs were removed. Nodules were counted. Each nodule was sectioned and stained with hematoxylin-eosine and examined under the microscope. 5-MTP pretreatment significantly attenuated lung metastasis. (D) Metabolic scheme illustrating 5-MTP biosynthesis in HsFb vs. A549 cancer cells. The dotted line denotes possible defects in the synthetic pathway.

Discussion

We have discovered a 5-MTP synthetic pathway that provides endogenous control of COX-2 overexpression. Our data indicate that 5-MTP is produced in human fibroblasts by two enzymatic steps: tryptophan hydroxylase to convert Try to 5-HTP and hydroxyindole O-methyltransferase to convert 5-HTP to 5-MTP (Fig. 5D). 5-MTP production is defective in cancer cells, which accounts for the dysregulated COX-2 overexpression in cancer cells within the inflammatory microenvironment. Our metabolic analysis provides evidence that deficiency in 5-MTP synthesis in cancer cells is closely associated with a low level of HIOMT expression and defective HIOMT catalytic activity. It is unclear whether defective 5-MTP synthesis in cancer cells could be attributed entirely to a low level of HIOMT expression or contributed by other factors that block the enzyme activity. Elucidation of the underlying mechanism will shed lights on the endogenous tumor surveillance and pave the way to identify target for tumor detection and cancer therapy.

Our findings have important pathophysiological relevances. Fibroblasts are widely distributed in most organs and tissues. At resting state, they are quiescent. However, in response to injury signals, they migrate to the tissue damage sites where they undergo rapid proliferation and phenotypic changes (33). They are considered to play an important role in wound healing, tissue remodeling, and inflammation (33–35). Our results imply that the proliferative fibroblasts are pivotal in controlling excessive inflammatory responses by producing robust quantities (in micromolars) of 5-MTP. 5-MTP acts in a paracrine and autocrine manner to suppress proinflammatory mediator-induced COX-2 expression. Because COX-2 overexpression is unequivocally linked to inflammation and inflammatory disorders (35), 5-MTP could be considered a unique endogenous control of inflammation, and its synthetic pathway is a viable target for new anti-inflammatory drug development. Fibroblasts can also respond to cancer signals. The resident fibroblasts migrate to the cancer territory where they are activated and proliferative. As stated above, their phenotype may be changed by cancer cells and the CAFs become actively involved in assisting cancer growth and metastasis. Our findings provide evidence for heterogeneity of CAF. A subset of CAF has active 5-MTP synthetic activity and may in fact play a role in cancer surveillance, whereas the “educated” CAFs lose the ability to synthesize 5-MTP and are converted to cancer-promoting cells. As proof of principle, we evaluated only two types of CAFs. It is unclear whether differential production of 5-MTP in prostate vs. breast CAFs is cancer type-, tissue-, or patient-related. Further studies are needed to elucidate the mechanism underlying the differential 5-MTP production, COX-2 inhibition, and cancer growth control by naive fibroblasts vs. CAFs. Nonetheless, 5-MTP and its synthetic pathway are crucial in cancer control and will be a valuable lead for improving cancer detection and therapy.

Materials and Methods

Cells.

Human fibroblasts, Hs68, Hs27, Hs925-sk, WI38 and murine cells, RAW264.7 and M. Dunni(Clone III8C) were from American Type Culture Collection. Human cancer cell lines A549, HT-29, Hep3B, and MCF7 and MCF10A were from the Bioresource Collection and Research Center. PcFb were isolated from a surgical specimen from a patient with prostate cancer as previously described (25). It was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm. bCAF were isolated from primary breast cancer tissue of a patient at National Health Research Institutes-National Cheng Kung University Hospital with IRB approval. Fibroblasts isolated from the human cancer were CD90 positive. Serum-starved and serum-replenished proliferative HsFb were prepared as previously described (36). The culture procedures and materials are provided in SI Materials and Methods.

Western Blot Analysis.

Analysis of COX-2 proteins by Western blotting was performed as previously described (37). A detailed procedure is provided in SI Materials and Methods.

Cell Migration and Invasion Assays.

A549 cancer cell migration was measured by transwell assay. All of the assays were done in triplicate. The detailed procedure is provided in SI Materials and Methods.

RNA Interference.

The target siRNA sequences used to silence human THP-1 compose three different siRNA duplexes (Santa Cruz Biotechnology): 5'-CUG UGA AUC UAC CAG AUA ATT-3', 5'-CCA ACA GAG UUC UGA UGU ATT-3'. and 5'-GGA AUG UCU UAU CAC AAC UTT-3'. The human HIOMT siRNA is a pool of three different siRNA duplexes: 5'-CUG UCA GUGUUC CCA CUU ATT-3', 5'-CUG UAC CCU GGA UGU AAG ATT-3', and 5'-GAG AGG AUC UAC CAC ACU UTT-3'. The negative control sequence was 5'-UUC UCCGA A CGU GUC ACG UTT-3'. Cells were transfected with siRNA duplexes using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) as previously described (38). The procedure is described in SI Materials and Methods.

Analysis of COX-2 Promoter Activity.

A promoter region of human COX-2 gene (−891 to +9) was constructed into luciferase reporter vector pGL3 as previously described (38). A detailed procedure is provided in SI Materials and Methods.

MTT Assay for Cell Proliferation.

Viable cells were analyzed by using MTT assay. The detailed procedure is provided in SI Materials and Methods.

Preparation of CMF2.

CMF2 was prepared by procedures modified from those previously reported (14). The detailed procedure is provided in SI Materials and Methods.

Metabolomic Analyses.

The metabolite analysis was performed using ultraperformance liquid chromatography (Acquity UPLC System, Waters Corporation) coupled with an orthogonal time-of-flight mass spectrometer (Xevo TOF MS, Waters Corporation). The detailed procedures are provided in SI Materials and Methods. The Human Metabolome Database and KEGG Database were used to search for chemical identity.

5-MTP Enzyme-Immunoassay.

The assay was developed according to a method previously described (39). The detailed procedure is provided in SI Materials and Methods.

Tumor Xenograft Experiment.

Six-week-old male CB-17 SCID mice, purchased from BioLASCO, were housed in a daily cycle of 12-h light and 12-h darkness and pathogen-free conditions at 26 °C at the Animal Center of the National Health Research Institutes. A549-luc-C8 cells (Caliper Life Sciences), cultured in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% FBS, were pretreated with 100 μM 5-MTP or vehicle for 5 h and were inoculated into the mice s.c. (5 × 106 cells/mouse). The 5-MTP–treated mice were injected with 100 mg 5-MTP/kg body weight intraperitoneally twice weekly. The vehicle group were injected with vehicle (0.033 N HCl in RPMI medium, neutralized with NaOH) twice weekly. The size of s.c. tumors were caliper-measured twice weekly. The tumor volume was calculated according to the formula of length × width × width/2. The tumor growth was also monitored weekly by an IVIS spectrum imaging system (40) as described in the SI Materials and Methods. Mice were euthanized at day 52. Subcutaneous tumors and lungs were removed and fixed with 10% Formalin. Nodules on each lobe of the lungs were counted. Histology of the nodules was examined under microscopy by tissue section and H&E staining. The animals’ care was in accordance with institutional guidelines and the protocol of in vivo experiments was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Utilization Committee of the National Health Research Institutes.

Statistical Analysis.

In all experiments except the metastastic nodules in xenograft tumor experiments, the statistical significance was analyzed by Student’s t test. The statistical significance of lung nodules in 5-MTP vs. control groups (n = 10 each) was analyzed by χ2. A P < 0.05 is considered significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Hsing-Pang Hsieh at the National Health Research Institutes for suggestions regarding serotonin-related chemicals, Dr. Gi-Ming Lai for discussions, and Dr. Pei-Feng Chen for discussion and critical reading of the manuscript. K.K.W., C.-C.K., and K.K.-C.T. are funded by the intramural program, National Health Research Institutes (Taiwan). K.K.W. is funded by the National Science Council (Taiwan) (96-3111-B-400-003, 99-3111-B-400-005, and 100-2321-B-400-020). H.G., E.F., L.S., and G.K. are funded by the Karolinska Institutet, Sweden.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1209919109/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Smith WL, DeWitt DL, Garavito RM. Cyclooxygenases: Structural, cellular, and molecular biology. Annu Rev Biochem. 2000;69:145–182. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang D, Dubois RN. The role of COX-2 in intestinal inflammation and colorectal cancer. Oncogene. 2010;29:781–788. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DuBois RN, Radhika A, Reddy BS, Entingh AJ. Increased cyclooxygenase-2 levels in carcinogen-induced rat colonic tumors. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:1259–1262. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8613017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wolff H, et al. Expression of cyclooxygenase-2 in human lung carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1998;58:4997–5001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elder DJ, Paraskeva C. COX-2 inhibitors for colorectal cancer. Nat Med. 1998;4:392–393. doi: 10.1038/nm0498-392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jacoby RF, Seibert K, Cole CE, Kelloff G, Lubet RA. The cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor celecoxib is a potent preventive and therapeutic agent in the min mouse model of adenomatous polyposis. Cancer Res. 2000;60:5040–5044. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steinbach G, et al. The effect of celecoxib, a cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor, in familial adenomatous polyposis. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1946–1952. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200006293422603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arber N, et al. PreSAP Trial Investigators Celecoxib for the prevention of colorectal adenomatous polyps. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:885–895. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsujii M, DuBois RN. Alterations in cellular adhesion and apoptosis in epithelial cells overexpressing prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase 2. Cell. 1995;83:493–501. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90127-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsujii M, et al. Cyclooxygenase regulates angiogenesis induced by colon cancer cells. Cell. 1998;93:705–716. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81433-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsujii M, Kawano S, DuBois RN. Cyclooxygenase-2 expression in human colon cancer cells increases metastatic potential. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:3336–3340. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.3336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu KK. Inducible cyclooxygenase and nitric oxide synthase. Adv Pharmacol. 1995;33:179–207. doi: 10.1016/s1054-3589(08)60669-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shao J, Sheng H, Inoue H, Morrow JD, DuBois RN. Regulation of constitutive cyclooxygenase-2 expression in colon carcinoma cells. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:33951–33956. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002324200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deng WG, et al. Purification and characterization of a cyclooxygenase-2 and angiogenesis suppressing factor produced by human fibroblasts. FASEB J. 2002;16:1286–1288. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0844fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olumi AF, et al. Carcinoma-associated fibroblasts direct tumor progression of initiated human prostatic epithelium. Cancer Res. 1999;59:5002–5011. doi: 10.1186/bcr138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bissell MJ, Radisky D. Putting tumours in context. Nat Rev Cancer. 2001;1:46–54. doi: 10.1038/35094059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mueller MM, Fusenig NE. Friends or foes: Bipolar effects of the tumour stroma in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:839–849. doi: 10.1038/nrc1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhowmick NA, Neilson EG, Moses HL. Stromal fibroblasts in cancer initiation and progression. Nature. 2004;432:332–337. doi: 10.1038/nature03096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kalluri R, Zeisberg M. Fibroblasts in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:392–401. doi: 10.1038/nrc1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Orimo A, et al. Stromal fibroblasts present in invasive human breast carcinomas promote tumor growth and angiogenesis through elevated SDF-1/CXCL12 secretion. Cell. 2005;121:335–348. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Räsänen K, Vaheri A. Activation of fibroblasts in cancer stroma. Exp Cell Res. 2010;316:2713–2722. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2010.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sugimoto H, Mundel TM, Kieran MW, Kalluri R. Identification of fibroblast heterogeneity in the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Biol Ther. 2006;5:1640–1646. doi: 10.4161/cbt.5.12.3354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stoker MG, Shearer M, O’Neill C. Growth inhibition of polyoma-transformed cells by contact with static normal fibroblasts. J Cell Sci. 1966;1:297–310. doi: 10.1242/jcs.1.3.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paland N, et al. Differential influence of normal and cancer-associated fibroblasts on the growth of human epithelial cells in an in vitro cocultivation model of prostate cancer. Mol Cancer Res. 2009;7:1212–1223. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-09-0073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Flaberg E, et al. High-throughput live-cell imaging reveals differential inhibition of tumor cell proliferation by human fibroblasts. Int J Cancer. 2011;128:2793–2802. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walther DJ, et al. Synthesis of serotonin by a second tryptophan hydroxylase isoform. Science. 2003;299:76. doi: 10.1126/science.1078197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang X, Beaulieu JM, Sotnikova TD, Gainetdinov RR, Caron MG. Tryptophan hydroxylase-2 controls brain serotonin synthesis. Science. 2004;305:217. doi: 10.1126/science.1097540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ichimura T, et al. Molecular cloning of cDNA coding for brain-specific 14-3-3 protein, a protein kinase-dependent activator of tyrosine and tryptophan hydroxylases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:7084–7088. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.19.7084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ni W, et al. The existence of a local 5-hydroxytryptaminergic system in peripheral arteries. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;154:663–674. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Axelrod J, Wurtman RJ, Snyder SH. Control of hydroxyindole O-methyltransferase activity in the rat pineal gland by environmental lighting. J Biol Chem. 1965;240:949–954. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Donohue SJ, Roseboom PH, Klein DC. Bovine hydroxyindole-O-methyltransferase. Significant sequence revision. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:5184–5185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rodriguez IR, Mazuruk K, Schoen TJ, Chader GJ. Structural analysis of the human hydroxyindole-O-methyltransferase gene. Presence of two distinct promoters. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:31969–31977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sartore S, et al. Contribution of adventitial fibroblasts to neointima formation and vascular remodeling: From innocent bystander to active participant. Circ Res. 2001;89:1111–1121. doi: 10.1161/hh2401.100844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Iyer VR, et al. The transcriptional program in the response of human fibroblasts to serum. Science. 1999;283:83–87. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5398.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martin P. Wound healing: Aiming for perfect skin regeneration. Science. 1997;276:75–81. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5309.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gilroy DW, Saunders MA, Sansores-Garcia L, Matijevic-Aleksic N, Wu KK. Cell cycle-dependent expression of cyclooxygenase-2 in human fibroblasts. FASEB J. 2001;15:288–290. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0573fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Deng WG, Zhu Y, Wu KK. Up-regulation of p300 binding and p50 acetylation in tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced cyclooxygenase-2 promoter activation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:4770–4777. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209286200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Deng WG, Zhu Y, Wu KK. Role of p300 and PCAF in regulating cyclooxygenase-2 promoter activation by inflammatory mediators. Blood. 2004;103:2135–2142. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-09-3131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu JY, Kuo CC. Pivotal role of ADP-ribosylation factor 6 in Toll-like receptor 9-mediated immune signaling. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:4323–4334. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.295113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jenkins DE, et al. Bioluminescent imaging (BLI) to improve and refine traditional murine models of tumor growth and metastasis. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2003;20:733–744. doi: 10.1023/b:clin.0000006815.49932.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.