Abstract

Chemical senses are crucial for all organisms to detect various environmental information. Different protein families, expressed in chemosensory organs, are involved in the detection of this information, such as odorant-binding proteins, olfactory and gustatory receptors, and ionotropic receptors. We recently reported an Expressed Sequence Tag (EST) approach on male antennae of the noctuid moth, Spodoptera littoralis, with which we could identify a large array of chemosensory genes in a species for which no genomic data are available.

Here we describe a complementary EST project on female antennae in the same species. 18,342 ESTs were sequenced and their assembly with our previous male ESTs led to a total of 13,685 unigenes, greatly improving our description of the S. littoralis antennal transcriptome. Gene ontology comparison between male and female data suggested a similar complexity of antennae of both sexes. Focusing on chemosensation, we identified 26 odorant-binding proteins, 36 olfactory and 5 gustatory receptors, expressed in the antennae of S. littoralis. One of the newly identified gustatory receptors appeared as female-enriched. Together with its atypical tissue-distribution, this suggests a role in oviposition. The compilation of male and female antennal ESTs represents a valuable resource for exploring the mechanisms of olfaction in S. littoralis.

Keywords: Olfactory receptor, Gustatory receptor, Odorant-binding protein, Expressed sequence tag, Lepidoptera, Spodoptera littoralis.

Introduction

The sense of smell is highly important for most animals to detect chemical information regarding various fitness-related resources. For many decades, moths have proven to be important models for studying the physiological and molecular bases of olfactory detection 1. First, their nocturnal life has led to a highly developed and sensitive olfactory system well suited to describe general paradigms. Second, moths include diverse and important pests of crops, forests and stored products, and studying their sense of smell offers the possibility to develop olfactory-based strategies to perturb critical behaviors, such as sex pheromone-mediated reproduction, host selection and oviposition.

The noctuid moth Spodoptera littoralis is one of the major Lepidoptera models used in olfaction research. This polyphagous noctuid species is an important cotton pest, and extensive research has led to a comprehensive insight into its chemical communication system. The sex pheromone and plant volatiles activating olfactory sensory neurons (OSN) have been identified 2, 3, various functional types of antennal olfactory sensilla have been characterized 3, 4, and the organization of the primary central olfactory system, the antennal lobe, as well as higher areas as the mushroom bodies has been described 5-7. From a molecular point of view, we recently sequenced an Expressed sequence tag (EST) library prepared from male S. littoralis antennae, leading to the identification of a partial repertoire of genes putatively involved in odorant and pheromone detection 8. Among them, we described members of crucial gene families involved in the olfactory process, such as odorant-binding proteins (OBPs), olfactory and gustatory receptors (ORs, GRs), and ionotropic receptors (IRs). OBPs are soluble proteins proposed to bind odorant molecules and transport them through the aquaeous sensillar lymph, allowing hydrophobic molecules to reach OSN dendrites 9, 10. Another family of binding proteins, the chemosensory protein (CSP) family, groups soluble proteins whose function is unclear. Although some exhibit binding activity towards odorants and pheromones 11, 12, they may participate in other physiological processes beyond chemoreception 13, 14. ORs and IRs constitute two families of chemosensory receptors located in the dendritic membrane of OSNs, whose activation upon ligand binding leads to the generation of an electrical signal that is transmitted to the brain 15, 16. ORs are multi-transmembrane domain ionotropic receptors, functioning as ion channels via heterodimerization with a subunit conserved within insects, referred to as ORco 17-19, while the variable part of the dimer defines ligand specificity 20, 21. This variable part also couples to G proteins, inducing upon activation a complementary metabotropic signaling 20. IRs are related to ionotropic glutamate receptors but with a divergent ligand-binding domain 16. Although they appear to be far more ancient than ORs, as they are found across protostomians, they were only recently discovered as key actors in odorant detection 22, 23. GRs are transmembrane domain receptors distantly related to insect ORs and expressed in gustatory receptor neurons. Recent studies suggest that GRs present a similar membrane topology to ORs 24 and act as ionotropic channels 25.

Research in the molecular field of moth olfaction has, until recently, largely been restricted to the silkmoth Bombyx mori, due to the availability of genomic data. Our EST strategy has been demonstrated to be well suited to identify a wide array of olfactory genes in a given species and was particularly relevant for the identification of divergent chemosensory receptors in a species for which no genomic data is available 8. Similar strategies have been followed to identify broad or partial repertoires of chemosensory receptors in some other moth species, such as Epiphyas postvittana 26, Manduca sexta 27 and Cydia pomonella 28, but the picture of the moth OR and IR gene families is still incomplete.

Here, we report the sequencing and analyses of a female S. littoralis antennal EST library that, together with our previous male EST data, allows us to extend our view of the S. littoralis antennal transcriptome and to significantly increase the number of identified olfactory genes in S. littoralis. Both male and female ESTs were assembled, leading to a total of 13,685 unigenes whose gene ontology (GO) annotation revealed enrichment in binding and catalytic activities. These data allowed us to identify new S. littoralis olfactory genes, including binding proteins and chemosensory receptors. Further qPCR experiments were conducted to study tissue- and sex-distribution of the newly identified ORs and GRs, revealing one female-enriched transcript possibly involved in oviposition.

Materials and Methods

Insect rearing and female antennae cDNA library construction

Insects were from a laboratory strain of S. littoralis that originated from an Egyptian population. Insects were reared on semi-artificial diet 29, under 23°C, 60-70% relative humidity and 16:8 light:dark cycle. Pupae were sexed and males and females were kept separately. Antennae were collected from 1-2 day old naïve adult females and stored at -80°C. Total RNA were isolated using the TriZol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), quantified in a spectrophotometer, and the quality verified by agarose gel electrophoresis. A custom normalized cDNA library was created by Evrogen (Russia) in the pAL 17.3 vector, using 1 mg of total RNA as starting material, without any amplification. The normalization procedure was used to minimize EST redundancy and to enrich the library for rare and low abundant genes, to allow new gene discovery.

EST sequencing

The library was plated, and 20,000 clones were randomly picked. Their 5' ends were sequenced using REV primer by the Genoscope (Evry, France). The plated library was arrayed robotically and bacterial clones had their plasmid DNA amplified using phi29 polymerase. The plasmids were end-sequenced using BigDye Termination kits on Applied Biosystems 3730xl DNA Analysers. Adaptor and vector were localized using cross_match (http://www.phrap.org/) using default matrix (1 for a match, -2 penalty for a mismatch), with mean scores of 6 and 10, respectively. Sequences were then trimmed following three criteria: vector and adaptor, poly(A) tail or low quality (defined as at least 15 among 20 bp with a phred score below 12). We finally obtained the 5' end sequences of 18,342 ESTs.

Sequence processing, assembly, unigene and peptide generation

Female ESTs were assembled with previously obtained male ESTs using the TGI Clustering tools (TGICL, http://compbio.dfci.harvard.edu/tgi/software) using the default parameters (minimum percent identity for overlaps: 94, minimum overlap length: 30 bp, maximum length of unmatched overhangs: 30), generating unigenes and singletons. Peptides were extracted from the unigenes using FrameDP 1.03 30, with three training iterations and using Swissprot (398,181 entries, August 2009) as reference protein database.

Gene identification and functional annotation

The newly identified unigenes were compared to the NCBI non redundant protein database (June 24th 2011 version), using BLASTX, with a 1e-8 e-value threshold. The Gene Ontology mapping and distribution were done with the help of BLAST2GO (GO association done by a BLAST against the NCBI NR database) 31. Finally, the functional domain protein profile and domain were predicted by queries against InterPro using InterproScan, 32, running a batch of analyses (BLASTProDom, Coil, FprintScan, Gene3D, HMMPanther, HMMPfam, HMMPIR, HMMSmart, HMMTigr, PatternScan, ProfileScan, RNA-BINDING, Seg and Superfamily) on the predicted ORFs.

GO-term enrichment

The analysis of the enrichment in GO-term between male and female transcriptomes was performed with the BLAST2GO application using GOSSIP 33. GO-terms in female data (female singletons + contigs assembled from female ESTs only) (test group) were tested for enrichment compared to male data (male singletons + contigs assembled from male ESTs only) (reference group) using Fisher's exact test with multiple testing correction.

Identification of odorant-binding proteins and chemosensory receptors

The S. littoralis antennal unigenes were searched with B. mori OBPs, CSPs, chemosensory receptors and available insect ORs retrieved from Swissprot as queries using TBLASTN 34. Additionally, the Interproscan results were scanned for the Interpro accession IPR006170 (Pheromone/general odorant-binding protein, PBP/GOBP Molecular Function: odorant binding GO:0005549) and IPR004117 (Molecular Function: olfactory receptor activity GO:0004984). S. littoralis putative chemosensory receptor sequences were in turn employed in searches to find more genes in an iterative process. OR transmembrane domains were predicted using the TMHMM server v.2.0 35. OBPs and CSPs were searched for the occurrence of a signal peptide using SignalP 4.0 36, secondary structures were predicted using the Psipred server 37, and logos were generated using WebLogo 38.

Phylogenetic analyses

We built OR and GR neighbor-joining trees based on Lepidoptera data sets. The OR data set contained 64 amino acid sequences from B. mori 39, 18 sequences from H. virescens 40, 41, 45 sequences from M. sexta 27 and the three OR sequences characterized in Epiphyas postvittana 26. The GR data set contained 65 amino acid sequences from B. mori 42, three, two and one sequences from H. virescens 41, M. sexta 27 and Papilio xuthus 43, respectively. Amino acid sequences were aligned using ClustalW2 44. Unrooted trees were constructed using the BioNJ algorithm with Poisson correction of distances, as implemented in Seaview v.4 45. Node support was assessed using a bootstrap procedure based on 1000 replicates. Images were created using the iTOL web server 46.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Naïve males and females in the middle of their second scotophase were used in the following experiments: female antennae, brains, proboscis, legs (mixture of front, middle, and hind legs), thorax, ovipositors and male antennae total RNAs (one sample per tissue) were extracted with the RNeasy® MicroKit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) that included a column DNase treatment. For each tissue, single-stranded cDNA was synthesized from 1 µg of total RNA with 200 U of M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Clontech, Mountain View, CA, USA) using buffer and protocol supplied in the Advantage® RT-for-PCR kit (Clontech). Gene-specific primers for S. littoralis chemosensory receptors and the endogenous control rpL8 were designed using the Beacon Designer 4.0 software (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA), yielding PCR products ranging from 100 to 250 bp (Table 1). qPCR mix was prepared in a total volume of 20 µl with 10 µl of Absolute QPCR SYBR Green Mix (ThermoFisher Scientific, Epsom, UK), 5 µl of diluted cDNA (or water for the negative control or RNA for controlling for the absence of genomic DNA) and 200 nM of each primer. qPCR assays were performed on S. littoralis cDNAs using a MJ Opticon Monitor Detection System (Bio-Rad). The PCR program began with a cycle at 95 °C for 15 min, followed by 40 cycles of 20 s at 95 °C, 15 s at 53 to 62 °C (depending on the primer pair) and 20 s at 72 °C. To assess the purity of the PCR reactions, a dissociation curve of the amplified product was performed by gradual heating from 50°C to 95°C at 0.2 °C/s. Standard curves were generated by a five-fold dilution series of a cDNA pool evaluating primer efficiency E (E=10(-1/slope)). All reactions were performed in duplicate. Chemosensory receptor expression levels were calculated relative to the expression of the rpL8 control gene and expressed as the ratio = ESlitCR(ΔCT SlitCR)/ErpL8 (ΔCT rpL8) 47.

Table 1.

Forward and reverse primer sequences used in real-time PCR, annealing temperatures, resulting amplicon lengths and PCR efficiencies.

| Unigenes | qPCR Forward primer sequences (5' to 3') | qPCR Reverse primer sequences (5' to 3') | Annealing T (°C) | Amplicon lenght (pb) | Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SlitOR7 | CCTTCCTATCGATGGCTCTG | CCCAGGTACCACTTGCAGTT | 60 | 115 | 2.1 |

| SlitOR10 | TTGCACTTTATGGGCAATGA | GAAGAGGAAAAGCGCTGATG | 62 | 188 | 1.9 |

| SlitOR12 | TTGGCCTTGGGTGTATCTTC | AAACGGCCACAAGTCTCATC | 62 | 171 | 2.1 |

| SlitOR19 | AAACGTGACTCCGTGAGCTT | CCGCCATCAACGTATTTTCT | 62 | 148 | 2.3 |

| SlitOR24 | CGCATCCGTTTATCGACTTT | CAAACCAGACCACAAGAGCA | 60 | 116 | 2.1 |

| SlitOR32 | GGTACTAAGGCGGTGGATGA | CCAATCCACAACCAAAATCC | 58 | 192 | 2.2 |

| SlitOR34 | CGCAATATGGGTGTCTTCCT | CATGTTGCTCGATTCCCTTT | 62 | 178 | 2.3 |

| SlitGR1 | CGACATTTACCGCGAATTTT | TTGGGACGAGCCTCAATTAC | 60 | 114 | 2.1 |

| SlitGR2 | GCCGGTGTCCAAGATACACT | CATGCTGATTGCCGAAGTAA | 62 | 168 | 2.2 |

| SlitGR4 | ATGCTGCGTCACACGACTAC | CCAACGGGAACATCTTCAAT | 58 | 115 | 2.2 |

| SlitGR5 | GTTTGTGTTGCTGGTGATGG | TTCGAGGCTAGGATCAAGGA | 62 | 159 | 1.9 |

| S. littoralis RpL8 | ATGCCTGTGGGTGCTATGC | TGCCTCTGTTGCTTGATGGTA | 58/62 | 189 | 1.90 |

Results and discussion

Complete repertoires of moth olfactory genes have been established only in B. mori, thanks to the availability of its sequenced genome. To date, it remains the only moth genome available. RNA sequencing appears to be a good alternative to identify partial olfactory gene repertoires in other species, and previous studies have proved it to be efficient 8, 27. In particular, the high sequence divergence observed within insect ORs has long served as a brake in chemosensory receptor identification. These receptors are very divergent both within and across insect species, precluding their identification through classical homology-based approaches 48.

EST statistics and unigene prediction

A total of 18,342 ESTs (mean length: 664.9 bp, median length: 665.1 bp, max length: 888 bp, min length: 72 bp, Table 2) were obtained from female antennae of S. littoralis. These ESTs have been deposited in the European Molecular Biology Laboratory database (EMBL) [EMBL:FQ958213-FQ976554]. The ESTs were processed and assembled with 20,760 male ESTs previously obtained 8. 30,986 ESTs were assembled into 5,623 contigs, 8,062 ESTs were singletons (20.6 % of total ESTs). On average, each contig was assembled from 18 ESTs. Among the singletons, 4,361 corresponded to male and 3,701 to female ESTs. The assembly led to a total of 13,685 unigenes (mean length: 980.9 bp, median length: 832 bp, max length: 4,100 bp, min length: 40 bp, Table 2) that putatively represent different transcripts. Compared to the 9,033 unigenes we previously identified in male antennae 8, this led to the identification of 4,652 new unigenes from S. littoralis antennae. It must be pointed out that we did only 5' end sequencing that, together with splice variants, polymorphism or reverse transcriptase errors, may have led to under-assembly and thus over-estimation of unigene counts. Indeed, by using the mean coding sequence size of 1.1-1.2 kb in the B. mori genome as reference 49, we could estimate the number of genes expressed to be 11,000-12,000 (13,685 unigenes with an average size of~ 981pb). This is higher than the estimation made in M. sexta, for which 7,000-8,000 genes were estimated to be expressed 27.

Table 2.

Data summary.

| Counts (total nb) | Min. length (bp/aa) | Average length (bp/aa) |

Max length (bp/aa) | Median lenght (bp/aa) | Accession numbers | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male ESTs | 20760 | 40 | 958.1 | 1525 | 820 | FQ0142366-FQ032656 |

| GW824594-GW826804 | ||||||

| HO118288-HO118415 | ||||||

| Female ESTs | 18 342 | 72 | 664.9 | 888 | 665.1 | FQ958213-FQ976554 |

| Unigenes | 13685 | 40 | 980.9 | 4,100 | 832 | |

| Coding regions | 8449 | 30 | 205.6 | 922 | 203 |

Identification of putative ORFs

Among the 13,685 unigenes, 8,449 presented a coding region (62 %, mean length: 205.6 aa, median length: 203 aa, max length: 922 aa, min length: 30 aa, Table 2). Protein sequences translated from the predicted open reading frame (ORF) set were compared to the non-redundant protein database (NR, version October 26th 2011). Most of the sequences (80.3 %) translated from predicted ORFs showed similarity to known proteins. 1,663 ORFs showed no similarity at all.

Gene identification and functional annotation

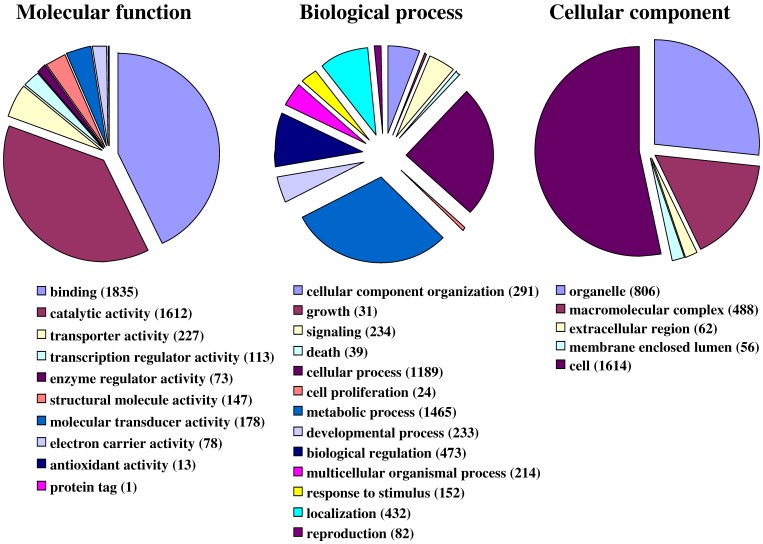

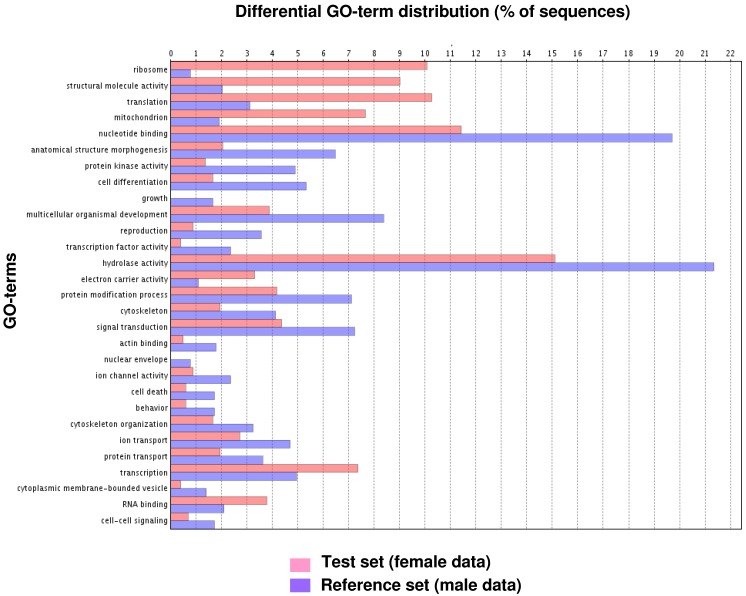

Fig. 1 illustrates the distribution of the S. littoralis unigene set in GO terms. Among the 13,685 S. littoralis unigenes, 3,376 correspond to at least one GO-term. As observed in the antennal transcriptome of M. sexta 27, a large number of transcripts could not be associated with a GO-term (75 %). Among those associated to a GO-term, 2,944 were assigned to a molecular function (87.2 %), 2,147 to putative biological processes (63.6 %), and 1,673 to a cellular component (49.6 %) (Fig. 1). In the molecular function category, the terms “binding” and “catalytic activity” were the most represented (54% and 47%, respectively), as already observed through the analyses of the male ESTs 8. When we compared the GO-term distribution of “male only” sequences (male singletons + contigs assembled from male ESTs only) with “female only”, differential distribution (P < 0.05) was observed for some GO-terms, such as “signal transduction” enriched in male antennae (Fig. 2). Interestingly, numbers of GO-terms were similar in the two datasets, suggesting a similar complexity of male and female antennae (Supplementary material S1). This is different from what has been observed in the analysis of M. sexta male and female transcriptomes 27, where the number of terms appearing for biological process and molecular function in female antennae was approximately twice the number as for male antennae.

Figure 1.

Distribution of S. littoralis unigenes annotated at GO level 2.

Figure 2.

GO-terms (GO-Slim) differentially distributed between male and female transcriptomes (Fisher's exact test, P < 0.05). Female data: female singletons + contigs assembled from female ESTs only (test group). Male data: male singletons + contigs assembled from male ESTs only (reference group).

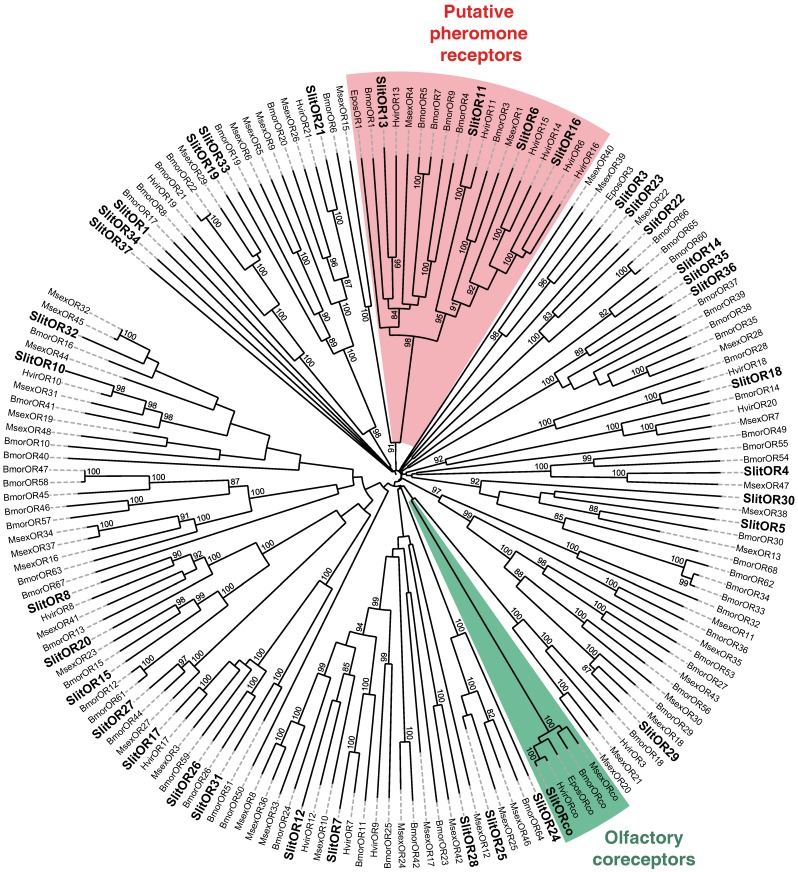

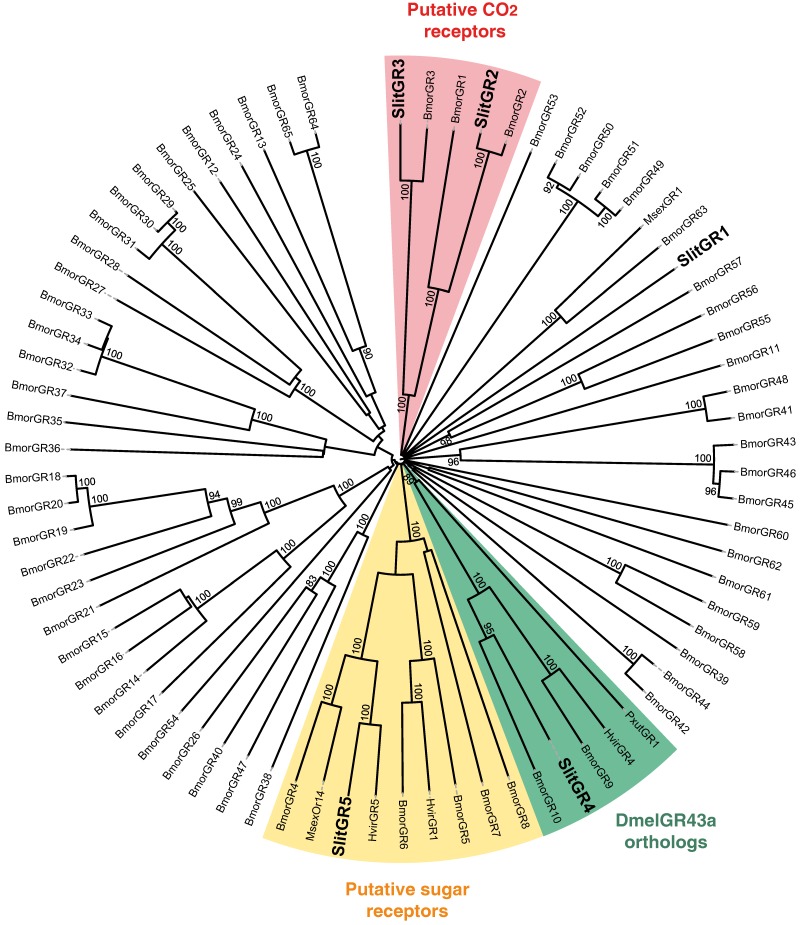

Olfactory and gustatory receptors

In our previous study, which focused on male antennal ESTs, we annotated 29 ORs and 2 GRs. Thanks to the female antennal sequences, we could extend five of the previously characterized SlitORs (OR4, 5, 8, 21, 29, former accession numbers FQ018861, EZ982621, FQ030158, EZ983645, EZ981024) and we identified seven new candidate SlitORs (OR7, 10, 12, 19, 24, 32, 34). In addition, one GR (GR2, former accession number GW825869) could be extended and three new candidate GRs were annotated (GR1, 4, 5). This led to a total of 36 ORs and 5 GRs identified in S. littoralis antennae (Table 3, fasta format file in Supplementary material S2). For convenience, SlitORs and GRs were numbered according to their closest homologs -when possible - from H. virescens, M. sexta or B. mori in the phylogenetic analyses (Fig. 3 & 4). Note that SlitOR9 is missing because the corresponding sequence was first annotated as a candidate OR but was later eliminated due to the presence of a stop codon within the predicted ORF.

Table 3.

List of S. littoralis unigenes putatively involved in chemosensory reception. Transmembrane domains (TM) were predicted using TMHMM version v.2.0.35.

| Name | Length (amino acid) | TM nb | BlastP hit | E value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SlitOR1 | 298 | 4 | ref|NP_001116817.1|olfactory receptor-like [Bombyx mori] | 1e-118 |

| SlitOR2 | 473 | 7 | gb|ABQ82137.1|chemosensory receptor 2 [Spodoptera littoralis] | 0.0 |

| SlitOR3 | 270 | 4 | gb|AEF32141.1|odorant receptor [Spodoptera exigua] | 8e-174 |

| SlitOR4 | 386 | 6-7 | ref|NP_001166616.1|olfactory receptor 54 [Bombyx mori] | 2e-101 |

| SlitOR5 | 397 | 6 | ref|NP_001103623.1|olfactory receptor 33 [Bombyx mori] | 8e-99 |

| SlitOR6 | 263 | 3 | emb|CAG38117.1|putative chemosensory receptor 16 [Heliothis virescens] | 5e-111 |

| SlitOR7 | 216 | 4 | emb|CAD31853.1|putative chemosensory receptor 7 [Heliothis virescens].. | 6e-98 |

| SlitOR8 | 258 | 4 | emb|CAD31949.1|putative chemosensory receptor 8 [Heliothis virescens] | 2e-110 |

| SlitOR10 | 212 | 3 | gb|ACC63238.1|olfactory receptor 10 [Helicoverpa armigera] | 1e-70 |

| SlitOR11 | 223 | 3 | gb|ACS45305.1|candidate odorant receptor 2 [Helicoverpa armigera] | 1e-139 |

| SlitOR12 | 224 | 3 | emb|CAG38113.1|putative chemosensory receptor 12 [Heliothis virescens]. | 8e-79 |

| SlitOR13 | 299 | 4 | dbj|BAG71423.2|olfactory receptor [Mythimna separata] | 5e-130 |

| SlitOR14 | 238 | 4 | ref|NP_001155301.1|olfactory receptor 60 [Bombyx mori] | 8e-126 |

| SlitOR15 | 390 | 7 | ref|NP_001091789.1|olfactory receptor 15 [Bombyx mori] | 1e-156 |

| SlitOR16 | 410 | 7-8 | emb|CAG38117.1|putative chemosensory receptor 16 [Heliothis .virescens] | 0.0 |

| SlitOR17 | 391 | 5 | emb|CAG38118.1|putative chemosensory receptor 17 [Heliothis virescens]. | 0.0 |

| SlitOR18 | 328 | 5 | gb|ACL81189.1|putative olfactory receptor 18 [Spodoptera littoralis] | 0.0 |

| SlitOR19 | 216 | 4 | tpg|DAA05980.1|TPA: TPA_exp: odorant receptor 22 [Bombyx mori] | 1e-101 |

| SlitOR20 | 331 | 5 | emb|CAD31949.1|putative chemosensory receptor 8 [Heliothis virescens] | 4e-108 |

| SlitOR21 | 215 | 4 | emb|CAG38122.1|putative chemosensory receptor 21 [Heliothis virescens] | 5e-112 |

| SlitOR22 | 280 | 5 | dbj|BAH66361.1|olfactory receptor [Bombyx mori] | 5e-07 |

| SlitOR23 | 422 | 6 | gb|EHJ75140.1|olfactory receptor [Danaus plexippus] | 4e-63 |

| SlitOR24 | 211 | 5 | ref|NP_001166621.1|olfactory receptor 64 [Bombyx mori] | 4e-42 |

| SlitOR25 | 131 | 1 | ref|NP_001166621.1|olfactory receptor 64 [Bombyx mori] | 8e-58 |

| SlitOR26 | 391 | 5 | ref|NP_001091790.1|candidate olfactory receptor [Bombyx mori] | 0.0 |

| SlitOR27 | 429 | 6-7 | ref|NP_001166607.1|olfactory receptor 44 [Bombyx mori] | 0.0 |

| SlitOR28 | 453 | 5 | gb|ABQ84982.1|putative chemosensory receptor 12 [Spodoptera littoralis]. | 0.0 |

| SlitOR29 | 326 | 5 | ref|NP_001166894.1|olfactory receptor 29 [Bombyx mori] | 9e-169 |

| SlitOR30 | 239 | 4 | dbj|BAH66327.1|olfactory receptor [Bombyx mori] | 9e-57 |

| SlitOR31 | 400 | 5 | dbj|BAH66346.1|olfactory receptor [Bombyx mori] | 4e-93 |

| SlitOR32 | 205 | 4 | ref|NP_001104832.2|olfactory receptor 16 [Bombyx mori] | 2e-101 |

| SlitOR33 | 250 | 4 | ref|NP_001091785.1|olfactory receptor 19 [Bombyx mori] | 7e-47 |

| SlitOR34 | 141 | 2 | gb|ADM32898.1|odorant receptor OR-5 [Manduca sexta] | 8e-13 |

| SlitOR35 | 408 | 6 | ref|NP_001103476.1|olfactory receptor 35 [Bombyx mori] | 1e-156 |

| SlitOR36 | 245 | 4 | ref|NP_001103476.1|olfactory receptor 35 [Bombyx mori] | 5e-89 |

| SlitOR37 | 266 | 5 | gb|EFN70678.1|Putative odorant receptor 13a [Camponotus floridanus]. | 0.90 |

| SlitGR1 | 120 | 1 | gb|EHJ69979.1| putative gustatory receptor candidate 59 [Danaus plexippus]. | 1e-22 |

| SlitGR2 | 244 | 4 | gb|EHJ68848.1| putative Gustatory receptor 21a [Danaus plexippus]. | 3e-155 |

| SlitGR3 | 213 | 4 | gb|EHJ78216.1| gustatory receptor 24 [Danaus plexippus] | 4e-93 |

| SlitGR4 | 128 | 1 | ref|NP_001091791.1| candidate olfactory receptor [Bombyx mori] | 2e-26 |

| SlitGR5 | 205 | 4 | emb|CAD31947.1| putative chemosensory receptor 5 [Heliothis virescens] | 2e-73 |

Figure 3.

Neighbor-joining tree for candidate olfactory receptors (ORs) from S. littoralis and other Lepidoptera. The tree was drawn with iTOL, based on an unrooted tree constructed using the BioNJ algorithm in Seaview v.4, which was made based on a sequence alignment using ClustalW2. Bmor, B. mori 39; Epos, E. postvittana 52, Hvir, H. virescens 40, 41; Msex, M. sexta 27; Slit, S. littoralis 8(this paper).

Figure 4.

Neighbor-joining tree for candidate gustatory receptors (GRs) from S. littoralis and other Lepidoptera. The tree was drawn with iTOL, based on an unrooted tree constructed using the BioNJ algorithm in Seaview v.4, which was made based on a sequence alignment using ClustalW2. Bmor, B. mori 42; Hvir, H. virescens 41; Msex, M. sexta 27; Pxut, P. xuthus 43; Slit, S. littoralis 8(this paper).

In S. littoralis, 63 glomeruli have been identified in the antennal lobe 6. Considering the one receptor-one glomerulus paradigm 50, 51, by which the number of expected ORs in a given species should correlate with the number of glomeruli in the antennal lobe, the 36 candidate OR genes identified may not represent the entire repertoire of adult S. littoralis ORs. Indeed, 47 and 43 ORs were identified through adult antennal transcriptome sequencing in M. sexta 27 and C. pomonella 28, respectively. In B. mori, 66 ORs were annotated from genome analyses 39. However, expression studies revealed that B. mori adult antennae express only 35 ORs out of these 66 39, a number that is very close to the 36 ORs we annotated in S. littoralis. Some glomeruli are also very likely innervated by OSNs expressing other classes of chemoreceptors, such as ionotropic receptors and gustatory receptors.

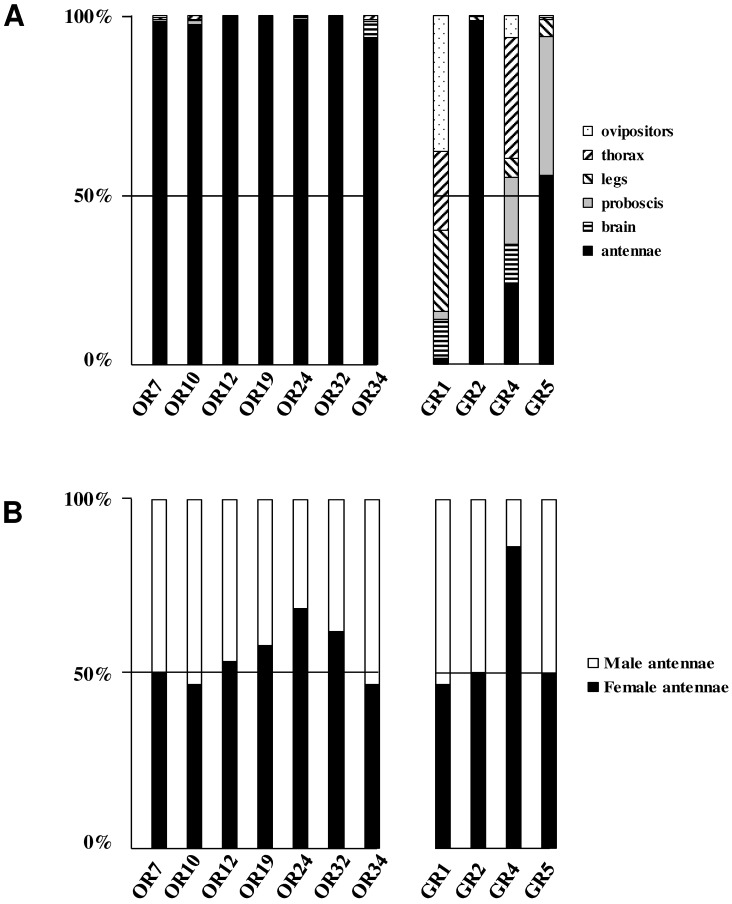

To complete our previously work 8, we conducted a preliminary study of the tissue-distribution of the newly identified S. littoralis candidate chemosensory receptors by qPCR, and we built neighbor-joining trees with all identified SlitORs and GRs. The seven new candidate ORs were clearly antenna enriched, with antennal expression in both sexes (Fig. 5AB), supporting our annotation. In the OR phylogenetic analysis (Fig. 3), no homologs of the B. mori cis-jasmone receptor (BmorOR56) or the linalool/linalyl acetate receptor (BmorOR42) were found, but homologs of BmorOR29 (whose known ligands are linalool, citral and several acetates) and of the Epiphyas postvittana citral receptor (EposOR3) were present 39, 52. Neither were homologs of the female-enriched B. mori ORs (OR30, 45, 46, 47, 48, 50 53, 54) found, but SlitOR33 clustered with a B. mori female-specific receptor, BmorOR19, which binds linalool 53, 54. SlitOR33 was, however, equally expressed in male and female antennae of S. littoralis 8. None of the new sequences clustered in the pheromone receptor clade (Fig. 3).

In the GR phylogeny (Fig. 4), one of the new GR candidates (SlitGR4) grouped in the D. melanogater GR43a ortholog subgroup, which includes the newly characterized B. mori fructose receptor (BmorGR9) 25 and the P. xuthus synephrine receptor (PxutGR1). The latter is expressed in female tarsi and necessary for correct oviposition behavior in this butterfly 43. SlitGR4 appeared in our preliminary qPCR analysis as enriched in female antennae compared to male (Fig. 5B), and was also expressed in other female body parts such as proboscis, legs and ovipositors (Fig. 5A). Together with the fact that sugars and other carbohydrates are known to influence host preference and oviposition in female moths 55, these data suggest that SlitGR4 may fulfill an important function in S. littoralis female oviposition. SlitGR5 grouped in the putative sugar receptor subfamily (Fig. 4), which includes the newly characterized B. mori inositol receptor (BmorGR8) 24. This is in concordance with previous electrophysiological studies that revealed that moth antennae are involved in sugar detection 56. SlitGR5 was found to be expressed not only in antennae but also in female proboscis and legs (Fig. 5A). Taken together, our results suggest that sugar/oviposition site detection may involve different sensory organs. Another SlitGR (SlitGR1) did not cluster with any identified moth candidate GRs (Fig. 4). Although found in antennae, this GR was mainly expressed in ovipositors and legs (Fig. 5A), which the female may use to explore oviposition sites.

Figure 5.

Distribution patterns of the newly identified S. littoralis candidate olfactory and gustatory receptors in different female tissues (A) and in male and female antennae (B). Gene expression levels were determined by real-time PCR and calculated relative to the expression of the rpL8 control gene and expressed as the ratio = ESlitCR(ΔCT SlitCR)/ErpL8 (ΔCT rpL8) .

The male EST analyses allowed us to classify one candidate SlitGR (GR2, formerly named GW825869) as a putative CO2 receptor 8. Here we could extend its sequence, confirming its high identity (83%) with one of the three B. mori candidate CO2 receptors, BmGr2NJ 42. Using qPCR, we revealed an unexpected antennal-specific expression of this gene (Fig. 5A). The construction of the GR tree revealed that another SlitGR, GR3, also clustered in the CO2 receptor family (Fig. 4), this one being equally expressed in antennae and proboscis 8. Up to now, moth sensory neurons specific for CO2 have been described only on labial palps 57. The annotation of two candidate CO2 receptors being expressed in antennae support our hypothesis that moths may also detect CO2 via their antennae.

Ionotropic receptors

We previously identified 12 candidate IRs in male antennal ESTs 58. The sequencing of female ESTs revealed that at least seven IR genes were also expressed in female antennae (IR76b, 25a, 75q.1, 75q.2, 41a, 87a, 25a), in concordance with our previous RT-PCR analyses 58. No additional IR sequences could be identified in female ESTs. Thus, we yet lack the SlitIR8a sequence, a gene suspected to be expressed in insect antennae and, like IR25a, encoding a co-receptor for other IRs 23. Both IR8a and IR25a could be identified in the transcriptomes of M. sexta 27 and C. pomonella 28.

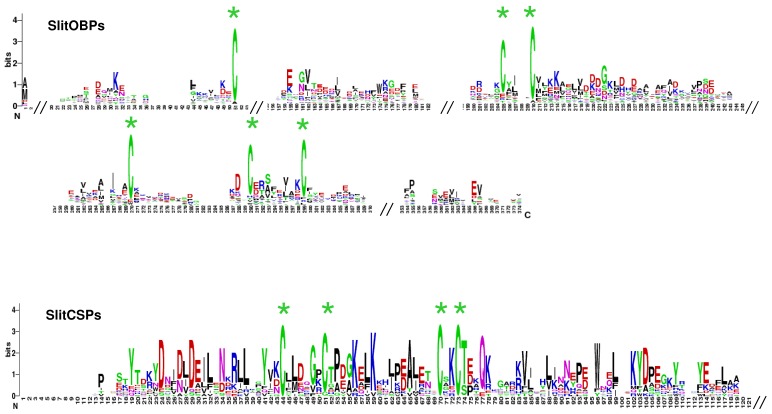

Odorant-binding proteins

A total of 35 sequences showing similarities with Lepidoptera OBPs were identified. Comparisons with the 17 OBP dataset obtained after analysis of the male data revealed that 9 female sequences were new OBPs and one female sequence extended an existing OBP sequence. This led to a total of 26 OBPs identified in S. littoralis antennae (FASTA format file in Supplementary material S2). Almost all the identified genes have the characteristic hallmarks of the OBP gene family: the presence of a signal peptide, the six α-helix pattern, and the highly conserved six cysteine profiles (Table 4, Fig. 6). However, despite the highly conserved secondary structure of OBP proteins, the SlitOBPs are highly divergent (average amino acid identity 18 %, min 6 %, max 65%) and exhibit a wide range of protein lengths (up to 266 amino acids) and cysteine number (up to 12, Table 4). For convenience, SlitOBPs were numbered according to their closest homologs. The number of candidate SlitOBPs identified is far less than the 46 annotated OBPs found in the genome of B. mori 59, 60 but more than the 18 putative OBPs identified in the transcriptome of M. sexta 27.

Table 4.

List of S. littoralis unigenes putatively involved in odorant binding. Signal peptides were determined using SignalP 4.0 36 and α-helices structures were predicted using the Psipred server 37.

| Name | Length (amino acid) | Signal peptide | C nb | α-helice nb | BlastP hit | E value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SlitPBP1 | 164 | Yes | 6 | 7 | ABQ84981.1 pheromone-binding protein 1 [Spodoptera littoralis] | 7e-120 |

| SlitPBP2 | 162 | Yes | 6 | 7 | AAS55551.2 pheromone binding protein 2 [Spodoptera exigua] | 2e-115 |

| SlitPBP3 | 164 | Yes | 6 | 7 | ACY78413.1 pheromone binding protein 3 [Spodoptera exigua] | 4e-104 |

| SlitGOBP1 | 163 | Yes | 7 | 7 | ABM54823.1 general odorant-binding protein GOBP1 [Spodoptera litura] | 9e-104 |

| SlitGOBP2 | 151 | No | 6 | 7 | ABM54824.1 general odorant-binding protein GOBP2 [Spodoptera litura] | 1e-104 |

| SlitOBP1 | 194 | Yes | 14 | 5 | EHJ77172.1 odorant binding protein [Danaus plexippus] | 1e-59 |

| SlitOBP2 | 184 | Yes | 8 | 6 | CAX63249.1 odorant-binding protein SaveOBP4 precursor [Sitobion avenae] | 1e-44 |

| SlitOBP3 | 129 | Yes | 4 | 6 | ADY17884.1 odorant binding protein [Spodoptera exigua] | 8e-72 |

| SlitOBP4 | 134 | Yes | 4 | 6 | AAL60426.1 antennal binding protein 8 [Manduca sexta] | 6e-74 |

| SlitOBP5 | 158 | Yes | 7 | 6 | ADY17882.1 odorant binding protein [Spodoptera exigua] | 1e-108 |

| SlitOBP6 | 62 | No | 3 | 3 | NP_001140187.1 odorant-binding protein 3 precursor [Bombyx mori] | 4e-15 |

| SlitOBP7 | 141 | Yes | 7 | 6-7 | AEB54588.1 OBP13 [Helicoverpa armigera] | 5e-78 |

| SlitOBP8 | 252 | Yes | 2 | 2 | BAH79159.1 odorant binding protein [Bombyx mori] | 1e-121 |

| SlitOBP9 | 258 | Yes | 6 | 5 | ADQ01713.1 odorant binding protein 29 [Anopheles funestus] | 1e-14 |

| SlitOBP10 | 174 | No | 5 | 4 | EFA09155.1 odorant binding protein 22 [Tribolium castaneum] | 4e-10 |

| SlitOBP11 | 147 | Yes | 6 | 6 | AAR28762.1 odorant-binding protein [Spodoptera frugiperda] | 8e-94 |

| SlitOBP12 | 147 | Yes | 6 | 6 | ADY17881.1 antennal binding protein [Spodoptera exigua] | 2e-93 |

| SlitOBP13 | 217 | Yes | 12 | 6 | AAL60414.1 twelve cysteine protein 1 [Manduca sexta] | 2e-21 |

| SlitOBP14 | 142 | Yes | 6 | 6 | AEB54586.1 OBP2 [Helicoverpa armigera] | 2e-87 |

| SlitOBP15 | 131 | No | 7 | 6 | AAL60415.1 antennal binding protein 4 [Manduca sexta] | 7e-53 |

| SlitOBP16 | 122 | No | 9 | 5 | AAL60414.1 twelve cysteine protein 1 [Manduca sexta] | 0.040 |

| SlitOBP17 | 144 | Yes | 6 | 6 | AAL60415.1 antennal binding protein 4 [Manduca sexta] | 5e-75 |

| SlitOBP18 | 151 | Yes | 6 | 6 | AEB54589.1 OBP8 [Helicoverpa armigera] | 1e-83 |

| SlitOBP19 | 239 | Yes | 4 | 2 | NP_001157372.1 odorant binding protein fmxg18C17 precursor [Bombyx mori] | 1e-73 |

| SlitOBP20 | 137 | Yes | 6 | 6-7 | CAA05508.1 antennal binding protein X [Heliothis virescens] | 5e-75 |

| SlitOBP21 | 126 | no | 8 | 6 | AAL60413.1 antennal binding protein 3 [Manduca sexta] | 1e-49 |

| SlitCSP1 | 128 | Yes | 4 | 6 | ACX53804.1 chemosensory protein [Heliothis virescens] | 1e-71 |

| SlitCSP2 | 120 | Yes | 4 | 6 | ACX53800.1 chemosensory protein [Heliothis virescens] | 2e-75 |

| SlitCSP3 | 75 | No | 3 | 4 | ABM67686.1 chemosensory protein CSP1 [Plutella xylostella] | 8e-20 |

| SlitCSP4 | 148 | Yes | 5 | 5 | EHJ76401.1 chemosensory protein CSP1 [Danaus plexippus] | 2e-51 |

| SlitCSP5 | 128 | Yes | 4 | 6 | ABM67688.1 chemosensory protein CSP1 [Spodoptera exigua] | 7e-85 |

| SlitCSP6 | 123 | Yes | 4 | 6 | ACX53806.1 chemosensory protein [Heliothis virescens] | 3e-72 |

| SlitCSP7 | 108 | Yes | 4 | 5 | BAF91720.1 chemosensory protein [Papilio xuthus] | 1e-56 |

| SlitCSP8 | 128 | Yes | 4 | 6 | ABM67689.1 chemosensory protein CSP2 [Spodoptera exigua] | 5e-86 |

| SlitCSP9 | 127 | Yes | 6 | 6 | AAY26143.1 chemosensory protein CSP [Spodoptera litura] | 1e-89 |

| SlitCSP10 | 266 | Yes | 4 | 6-7 | NP_001037069.1 chemosensory protein 9 precursor [Bombyx mori] | 2e-89 |

| SlitCSP11 | 113 | Yes | 4 | 6 | AAK14793.1 sensory appendage protein-like protein [Mamestra brassicae] | 5e-44 |

| SlitCSP12 | 124 | Yes | 4 | 6 | ACX53817.1 chemosensory protein [Heliothis virescens] | 4e-58 |

| SlitCSP13 | 122 | Yes | 4 | 6 | ACX53813.1 chemosensory protein [Heliothis virescens] | 4e-75 |

| SlitCSP14 | 127 | Yes | 4 | 6 | BAF91712.1 chemosensory protein [Papilio xuthus] | 1e-70 |

Figure 6.

SlitOBP and CSP sequence logo. Degree of amino acid sequence conservation 38 along the primary sequence axis of odorant-binding proteins (OBPs) and the chemosensory proteins (CSPs) of S. littoralis. Depicted amino acid character size correlates to relative conservation across aligned sequences. Green asterisks indicate the conserved six and four cysteine motifs of OBP and CSP, respectively.

Sensory neuron membrane proteins and chemosensory proteins

Sensory neuron membrane proteins (SNMPs), located in the dendritic membrane of primarily pheromone-specific OSNs, are thought to trigger ligand delivery to the receptor 61. Moths usually express two SNMPs, and the D. melanogaster SNMP1 homolog has been demonstrated to play a role in pheromone detection 62. The two SlitSNMPs were previously identified in the male ESTs, and were also represented in female ESTs, revealing that these proteins are expressed in both sexes. The SlitSNMP1 sequence was complete thanks to the male data. The female data allowed us to complete the SlitSNMP2 sequence.

Chemosensory proteins are soluble proteins expressed in a wide range of tissues and a chemosensory function has in fact been demonstrated for only a restricted number of such proteins 10, the others acting as general carriers for hydrophobic ligands in the insect body. Here, we identified 17 sequences expressed in female antennae showing similarities with Lepidoptera CSPs. Comparison with the 9 CSP annotated in the male ESTs revealed that five female sequences were new CSPs, leading to a total of 14 CSPs identified in S. littoralis antennae (FASTA format file in Supplementary material S2). Almost all deduced protein sequences have the characteristic hallmarks of CSPs: the presence of a signal peptide, the six α-helix pattern, and the highly conserved four cysteine profiles (Table 4, Fig. 6). 22 putative CSPs have been annotated in B. mori 60, 63 and 21 in M. sexta 27, while we identified only 14 candidate CSPs. Nevertheless, our data confirmed that Lepidoptera express a higher number of CSPs than other insect families, such as Diptera 60. Although their role in chemoreception should be taken with caution, at least one SlitCSP (SlitCSP3) may be involved in contact chemoreception since it is homologous to Plutella xylostella CSP1 that binds non volatile oviposition deterrents 64.

LepidoDB implementation

Lepido-DB (http://www.inra.fr/lepidodb) is a centralized bioinformatic resource for the genomics of major lepidopteran pests 65. This Information System was designed to store, organize, display and distribute various genomic data and annotations. All the data, unigenes, ORFs and their annotation generated in this project have been included in LepidoDB. As a result, from the project page http://www.inra.fr/lepidodb/spodoptera_littoralis, one can retrieve the whole sequence set, query with a keyword and retrieve the corresponding sequences.

Conclusion

The main objective of this study was to investigate the antennal transcriptome of the noctuid moth S. littoralis. Thanks to the sequencing of female ESTs, we annotated a total of 26 candidate OBPs, 14 CSPs, 36 ORs and 5 GRs in the antennae of S. littoralis. This strategy appears to be particularly relevant for the identification of new insect chemosensory receptors in a species for which no genomic data are available. The availability of this large antennal transcriptome constitutes a valuable resource for studies of insect olfaction.

Although the generation of gender-specific transcriptomes did not highlight strong differences between sexes, we evidenced male-specific ORs as candidate pheromone receptors and a female-enriched GR as a candidate oviposition stimulant receptor. It has to be noticed that we focused our study on naïve insects, whereas mating is known to induce big changes in the olfactory behaviors. For example, S. littoralis females switch their olfactory response from food to egg-laying cues following mating 66. This switch may be associated with regulation in the transcriptome expression. Comparison of antennal transcriptomes from males and females that encountered diverse experiences would then lead to identification of more regulated genes, as candidate genes involved in gender-specific behaviors.

Supplementary Material

S1: Comparison of male and female gene expression using GO categorization for biological processes (upper) and molecular function (lower), both level 3. S2: Fasta amino acid sequences of annotated S. littoralis OBPs, CSPs, ORs and GRs.

Acknowledgments

We thank the BioGenouest platform for their bioinformatics support. This work was supported by INRA, ANR-09-BLAN-0239-01 funding, a Genoscope partnership, the Swedish Government Linnaeus initiative Insect Chemical Ecology, Ethology and Evolution, the Swedish Science Council, the Trygger Foundation, and the Max Planck Society.

References

- 1.Kaissling K-E. Physiology of pheromone reception in insects (an example of moths) ANIR. 2004;6:73–91. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nesbitt BF, Beevor PS, Cole RA, Lester R, Poppi RG. Sex pheromones of two noctuid moths. Nat New Biol. 1973;244:208–9. doi: 10.1038/newbio244208a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson P, Hansson BS, Lofqvist J. Plant-odour-specific receptor neurones on the antennae of female and male Spodoptera littoralis. Physiol Entomol. 1995;20:189–98. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ljungberg H, Anderson P, Hansson BS. Physiology and morphology of pheromone-specific sensilla on the antennae of male and female Spodoptera littoralis (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) J Insect Physiol. 1993;39:253–60. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ochieng SA, Anderson P, Hansson BS. Antennal lobe projection patterns of olfactory receptor neurons involved in sex pheromone detection in Spodoptera littoralis (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) Tissue Cell. 1995;27:221–32. doi: 10.1016/s0040-8166(95)80024-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Couton L, Minoli S, Kieu K, Anton S, Rospars JP. Constancy and variability of identified glomeruli in antennal lobes: computational approach in Spodoptera littoralis. Cell Tissue Res. 2009;337:491–511. doi: 10.1007/s00441-009-0831-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sjoholm M, Sinakevitch I, Strausfeld NJ, Ignell R, Hansson BS. Functional division of intrinsic neurons in the mushroom bodies of male Spodoptera littoralis revealed by antibodies against aspartate, taurine, FMRF-amide, Mas-allatotropin and DC0. Arthropod Struct Dev. 2006;35:153–68. doi: 10.1016/j.asd.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Legeai F, Malpel S, Montagne N, Monsempes C, Cousserans F, Merlin C. et al. An Expressed Sequence Tag collection from the male antennae of the Noctuid moth Spodoptera littoralis: a resource for olfactory and pheromone detection research. BMC Genomics. 2011;12:86. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vogt RG. Biochemical diversity of odor detection:OBPs, ODEs and SNMPs. In: Blomquist GJ, Vogt RG, editors. Insect Pheromone Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. Elsevier Academic Press; 2003. pp. 391–445. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pelosi P, Zhou JJ, Ban LP, Calvello M. Soluble proteins in insect chemical communication. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63:1658–76. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5607-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacquin-Joly E, Vogt RG, Francois MC, Nagnan-Le Meillour P. Functional and expression pattern analysis of chemosensory proteins expressed in antennae and pheromonal gland of Mamestra brassicae. Chem Senses. 2001;26:833–44. doi: 10.1093/chemse/26.7.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Briand L, Swasdipan N, Nespoulous C, Bezirard V, Blon F, Huet JC. et al. Characterization of a chemosensory protein (ASP3c) from honeybee (Apis mellifera L.) as a brood pheromone carrier. Eur J Biochem. 2002;269:4586–96. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.03156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kitabayashi AN, Arai T, Kubo T, Natori S. Molecular cloning of cDNA for p10, a novel protein that increases in the regenerating legs of Periplaneta americana (American cockroach) Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 1998;28:785–90. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(98)00058-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gonga L, Luoa Q, Rizwan-ul-Haqa M, Hua M-Y. Cloning and characterization of three chemosensory proteins from Spodoptera exigua and effects of gene silencing on female survival and reproduction. Bull Entomol Res. 2012 doi: 10.1017/S0007485312000168. doi:10.1017/S0007485312000168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Touhara K, Vosshall LB. Sensing odorants and pheromones with chemosensory receptors. Annu Rev Physiol. 2009;71:307–32. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.010908.163209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benton R, Vannice KS, Gomez-Diaz C, Vosshall LB. Variant ionotropic glutamate receptors as chemosensory receptors in Drosophila. Cell. 2009;136:149–62. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Larsson MC, Domingos AI, Jones WD, Chiappe ME, Amrein H, Vosshall LB. Or83b encodes a broadly expressed odorant receptor essential for Drosophila olfaction. Neuron. 2004;43:703–14. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benton R, Sachse S, Michnick SW, Vosshall LB. Atypical membrane topology and heteromeric function of Drosophila odorant receptors in vivo. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e20. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vosshall LB, Hansson BS. A Unified Nomenclature System for the Insect Olfactory Coreceptor. Chem Senses. 2011;36:497–8. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjr022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wicher D, Schafer R, Bauernfeind R, Stensmyr MC, Heller R, Heinemann SH. et al. Drosophila odorant receptors are both ligand-gated and cyclic-nucleotide-activated cation channels. Nature. 2008;452:1007–11. doi: 10.1038/nature06861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sato K, Pellegrino M, Nakagawa T, Vosshall LB, Touhara K. Insect olfactory receptors are heteromeric ligand-gated ion channels. Nature. 2008;452:1002–6. doi: 10.1038/nature06850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Croset V, Rytz R, Cummins SF, Budd A, Brawand D, Kaessmann H. et al. Ancient protostome origin of chemosensory ionotropic glutamate receptors and the evolution of insect taste and olfaction. PLoS Genet. 2010;6(8):e1001064. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abuin L, Bargeton B, Ulbrich MH, Isacoff EY, Kellenberger S, Benton R. Functional architecture of olfactory ionotropic glutamate receptors. Neuron. 2011;69:44–60. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.11.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang HJ, Anderson AR, Trowell SC, Luo AR, Xiang ZH, Xia QY. Topological and functional characterization of an insect gustatory receptor. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e24111. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sato K, Tanaka K, Touhara K. Sugar-regulated cation channel formed by an insect gustatory receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:11680–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019622108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jordan MD, Stanley D, Marshall SD, De Silva D, Crowhurst RN, Gleave AP. et al. Expressed sequence tags and proteomics of antennae from the tortricid moth, Epiphyas postvittana. Insect Mol Biol. 2008;17:361–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2008.00812.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grosse-Wilde E, Kuebler LS, Bucks S, Vogel H, Wicher D, Hansson BS. Antennal transcriptome of Manduca sexta. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:7449–54. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017963108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bengtsson JM, Trona F, Montagné N, Anfora G, Ignell R, Witzgall P. et al. Putative chemosensory receptors of the codling moth, Cydia pomonella, identified by antennal transcriptome analysis. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(2):e31620. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Poitout S, Buès R. Elevage de chenilles de vingt-huit espèces de Lépidoptères Noctuidae et de deux espèces d'Arctiidae sur milieu artificiel simple. Particularités de l'élevage selon les espèces. Ann Zool Ecol anim. 1974;6:431–41. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gouzy J, Carrere S, Schiex T. FrameDP: sensitive peptide detection on noisy matured sequences. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:670–1. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Conesa A, Gotz S, Garcia-Gomez JM, Terol J, Talon M, Robles M. Blast2GO: a universal tool for annotation, visualization and analysis in functional genomics research. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:3674–6. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Quevillon E, Silventoinen V, Pillai S, Harte N, Mulder N, Apweiler R. et al. InterProScan: protein domains identifier. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W116–20. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bluthgen N, Brand K, Cajavec B, Swat M, Herzel H, Beule D. Biological profiling of gene groups utilizing Gene Ontology. Genome Inform. 2005;16:106–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W. et al. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krogh A, Larsson B, von Heijne G, Sonnhammer EL. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. J Mol Biol. 2001;305:567–80. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Petersen TN, Brunak S, von Heijne G, Nielsen H. SignalP 4.0: discriminating signal peptides from transmembrane regions. Nat Methods. 2011;8:785–6. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Buchan DW, Ward SM, Lobley AE, Nugent TC, Bryson K, Jones DT. Protein annotation and modelling servers at University College London. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:W563–8. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Crooks GE, Hon G, Chandonia JM, Brenner SE. WebLogo: a sequence logo generator. Genome Res. 2004;14:1188–90. doi: 10.1101/gr.849004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tanaka K, Uda Y, Ono Y, Nakagawa T, Suwa M, Yamaoka R. et al. Highly selective tuning of a silkworm olfactory receptor to a key mulberry leaf volatile. Curr Biol. 2009;19:881–90. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krieger J, Grosse-Wilde E, Gohl T, Dewer YM, Raming K, Breer H. Genes encoding candidate pheromone receptors in a moth (Heliothis virescens) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:11845–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403052101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Krieger J, Raming K, Dewer YM, Bette S, Conzelmann S, Breer H. A divergent gene family encoding candidate olfactory receptors of the moth Heliothis virescens. Eur J Neurosci. 2002;16:619–28. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wanner KW, Robertson HM. The gustatory receptor family in the silkworm moth Bombyx mori is characterized by a large expansion of a single lineage of putative bitter receptors. Insect Mol Biol. 2008;17:621–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2008.00836.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ozaki K, Ryuda M, Yamada A, Utoguchi A, Ishimoto H, Calas D. et al. A gustatory receptor involved in host plant recognition for oviposition of a swallowtail butterfly. Nat Commun. 2011;2:542. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGettigan PA, McWilliam H. et al. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2947–8. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gouy M, Guindon S, Gascuel O. SeaView version 4: A multiplatform graphical user interface for sequence alignment and phylogenetic tree building. Mol Biol Evol. 2010;27:221–4. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msp259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Letunic I, Bork P. Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL): an online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:127–8. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:e45. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jacquin-Joly E, Merlin C. Insect olfactory receptors: contributions of molecular biology to chemical ecology. J Chem Ecol. 2004;30:2359–97. doi: 10.1007/s10886-004-7941-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.ISGC. The genome of a lepidopteran model insect, the silkworm Bombyx mori. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2008;38:1036–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2008.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Couto A, Alenius M, Dickson BJ. Molecular, anatomical, and functional organization of the Drosophila olfactory system. Curr Biol. 2005;15:1535–47. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fishilevich E, Vosshall LB. Genetic and functional subdivision of the Drosophila antennal lobe. Curr Biol. 2005;15:1548–53. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.07.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jordan MD, Anderson A, Begum D, Carraher C, Authier A, Marshall SD. et al. Odorant receptors from the light brown apple moth (Epiphyas postvittana) recognize important volatile compounds produced by plants. Chem Senses. 2009;34:383–94. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjp010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wanner KW, Anderson AR, Trowell SC, Theilmann DA, Robertson HM, Newcomb RD. Female-biased expression of odourant receptor genes in the adult antennae of the silkworm, Bombyx mori. Insect Mol Biol. 2007;16:107–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2007.00708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Anderson AR, Wanner KW, Trowell SC, Warr CG, Jaquin-Joly E, Zagatti P. et al. Molecular basis of female-specific odorant responses in Bombyx mori. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2009;39:189–97. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lombarkia N, Derridj S. Resistance of apple trees to Cydia pomonella egg laying due to leaf surface metabolites. Ent Exp Appl. 2008;128:57–65. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jorgensen K, Almaas TJ, Marion-Poll F, Mustaparta H. Electrophysiological characterization of responses from gustatory receptor neurons of sensilla chaetica in the moth Heliothis virescens. Chem Senses. 2007;32:863–79. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjm057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bogner F, Boppre M, Ernst KD, Boeckh J. CO2 sensitive receptors on labial palps of Rhodogastria moths (Lepidoptera: Arctiidae): physiology, fine structure and central projection. J Comp Physiol A. 1986;158:741–9. doi: 10.1007/BF01324818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Olivier V, Monsempes C, Francois MC, Poivet E, Jacquin-Joly E. Candidate chemosensory ionotropic receptors in a Lepidoptera. Insect Mol Biol. 2011;20:189–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2010.01057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gong DP, Zhang HJ, Zhao P, Xia QY, Xiang ZH. The Odorant Binding Protein gene family from the genome of silkworm, Bombyx mori. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:332. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vieira FG, Rozas J. Comparative genomics of the odorant-binding and chemosensory protein gene families across the Arthropoda: origin and evolutionary history of the chemosensory system. Genome Biol Evol. 2011;3:476–90. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evr033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nichols Z, Vogt RG. The SNMP/CD36 gene family in Diptera, Hymenoptera and Coleoptera: Drosophila melanogaster, D. pseudoobscura, Anopheles gambiae, Aedes aegypti, Apis mellifera, and Tribolium castaneum. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2008;38:398–415. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Benton R, Vannice KS, Vosshall LB. An essential role for a CD36-related receptor in pheromone detection in Drosophila. Nature. 2007;450:289–93. doi: 10.1038/nature06328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gong DP, Zhang HJ, Zhao P, Lin Y, Xia QY, Xiang ZH. Identification and expression pattern of the chemosensory protein gene family in the silkworm, Bombyx mori. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;37:266–77. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2006.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liu X, Luo Q, Zhong G, Rizwan-Ul-Haq M, Hu M. Molecular characterization and expression pattern of four chemosensory proteins from diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae) J Biochem. 2010;148:189–200. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvq050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.d'Alençon E, Sezutsu H, Legeai F, Permal E, Bernard-Samain S, Gimenez S. et al. Extensive synteny conservation of holocentric chromosomes in Lepidoptera despite high rates of local genome rearrangements. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:7680–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910413107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Saveer AM, Kromann SH, Birgersson G, Bengtsson M, Lindblom T, Balkenius A. et al. Floral to green: mating switches moth olfactory coding and preference. Proc Biol Sci. 2012;279:2314–22. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2011.2710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

S1: Comparison of male and female gene expression using GO categorization for biological processes (upper) and molecular function (lower), both level 3. S2: Fasta amino acid sequences of annotated S. littoralis OBPs, CSPs, ORs and GRs.