Abstract

Granular cell ameloblastoma is a rare, benign neoplasm of the odontogenic epithelium. A case of massive granular cell ameloblastoma in a 44-year-old Thai female is reported. Histopathological features displayed a follicular type of ameloblastoma with an accumulation of granular cells residing within the tumor follicles. After treatment by partial mandibulectomy, the patient showed a good prognosis without recurrence in a 2-year follow-up. To characterize the granular cells in ameloblastoma, we examined the expression of basement membrane (BM) proteins, including collagen type IV, laminins 1 and 5 and fibronectin using immunohistochemistry. Except for the granular cells, the tumor cells demonstrated a similar expression of BM proteins compared to follicular and plexiform ameloblastomas in our previous study, whereas the granular cells showed strong positivity to laminins 1 and 5 and fibronectin. The increased fibronectin expression in granular cells suggests a possibility of age-related transformation of granular cells in ameloblastoma.

Keywords: ameloblastoma, collagen type IV, fibronenctin, granular cell, laminin 1, laminin 5

Introduction

Ameloblastoma is the most common odontogenic tumor with a variety of microscopic subtypes. Histopathologic variants of ameloblastoma include follicular, plexiform, acanthomatous, granular cell, desmoplastic and basal cell patterns. Despite histopathological diversity, behaviors of these subtypes have few differences.1

Granular cell ameloblastoma is a less common histological subtype of ameloblastoma. The English literature search has revealed approximately 30 studies regarding this rare subtype of ameloblastoma. Except for the study by Hartman, only 1–4 cases were included in each study, indicating the rarity of this lesion.2,3,4,5,6 In the largest series of granular cell ameloblastomas retrieved from the files of the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, granular cell ameloblastoma accounted for 5% of 408 cases of ameloblastomas.2 Histopathological features of the granular cell ameloblastomas display a transformation of the cytoplasm in epithelial tumor cells. Instead of the stellate reticulum-like cells, the transformed cells become enlarged and contain coarse eosinophilic granules in their cytoplasm.1,7 This transformation was thought to be a degenerative change, but later studies on ultrastructure and histochemistry indicated that these cytoplasmic granules were an accumulation of lysosomes.3,5. However, how this lysosomal transformation occurs is largely unknown.

Granular cells are also found in other odontogenic tumors, namely, plexiform granular cell odontogenic tumors (PGCOTs) and granular cell variant of odontogenic fibroma. The PGCOT is an extremely rare odontogenic tumor.8,9 The key histopathological feature is interlacing strands of odontogenic epithelium with each strand being two cell layers' thick. The large polyhedral tumor cells contain abundant eosinophilic granules in their cytoplasm. The nuclei are oriented away from the basement membrane in a ‘back-to-back' appearance. The PGCOTs and the granular cell ameloblastomas are similar in many aspects. The average age at the diagnosis, the common location and the radiographic features of these two tumors are indistinguishable. The granular cells of these two lesions share similar morphological and histochemical characteristics. Ultrastructurally, the cytoplasmic granules of tumor cells in both entities are lysosomal.9 The odontogenic fibroma with granular cells is considered to be a rare variant of odontogenic fibroma.7 With respect to clinical and radiographic features, the granular cell variant of odontogenic fibroma is not different from the usual odontogenic fibroma. The essential histopathological feature is the presence of enlarge stromal cells with delicately granular cytoplasm. The granular cells in the granular cell variant of odontogenic fibroma contain lysosome-like organelles as demonstrated by electron microscopic examination.7,10 Similar to the granular cells in ameloblastomas, the accumulation process of the lysosomal granules in the granular cells in the PGCOTs and in the granular cell variant of odontogenic fibromas is not understood.

Basement membrane (BM) is a highly organized extracellular matrix that typically serves as a barrier between epithelium or endothelial cells or muscle cells and surrounding mesenchymal tissues. BM also provides a mechanical support to the overlying cells. Besides being a supportive structure, the BM mediates interactions between two cell layers, playing pivotal roles in development and diseases. The biological role of the BM has been shown to be involved in cell proliferation, differentiation, adhesion and migration.11

A number of inherited diseases affecting the skin, kidney, muscle and eyes result from defective BM proteins such as epidermolysis bullosa, Alport syndrome and Fraser syndrome.12 In addition, alterations in BM proteins expression contribute to development and progression of tumors.13,14 Expression of cytoplasmic and BM laminin was increased with the degree of tumor cell differentiation in basal cell carcinoma.14 Loss of collagen type IV has been observed in invasive prostate cancer.13 BM proteins appear to play an important role in odontogenic tumors since many BM proteins are expressed in several types of odontogenic tumors.15,16,17 For example, laminin 5 may be involved in the tumor cell differentiation of calcifying cystic odontogenic tumors and the mineralization in adenomatoid odontogenic tumors.17 In ameloblastomas, collagen type IV was shown to play a role in tumor cytodifferentiation and progression.18

Expression of BM components has been studied in ameloblastomas both in follicular and plexiform variants, but not in granular cell subtype.17,18 The purpose of this study was to report a case of granular cell ameloblastoma and to examine the expression of BM components, including collagen type IV, laminins 1 and 5 and fibronectin in this tumor. The expression of these BM proteins may provide an understanding of the granular cell transformation in this less common ameloblastoma subtype.

Case report

A 44-year-old Thai female was seen for evaluation of her right facial swelling that had been present for 5–6 years. Extra-oral examination revealed a facial asymmetry resulting from a swelling of her right cheek. On oral examination, an immense mass on the right mandible was clearly observed. The mass was firm, painless and covered by oral mucosa with notable ulcers and occlusal imprints (Figure 1). By palpation, bony hard swelling was present at buccal and lingual aspects of the mandible. There was no lip numbness. Her past medical history and the remainder of physical examinations were noncontributory. The patient could not recall the dental history related to the lost of the right lower molars. A panoramic radiograph revealed a large well-defined multilocular radiolucent lesion causing bony destruction of the right mandible and severe root resorption of the mandibular second premolar (Figure 2). The lesion extended from the mesial area of the right mandibular second premolar to the mandibular ramus.

Figure 1.

A clinical photograph of granular cell ameloblastoma in the oral cavity shows an enormous mass on the right mandible.

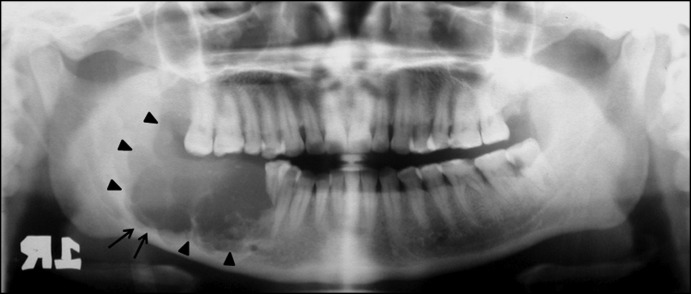

Figure 2.

A panoramic radiograph displays a well defined multilocular radiolucency with scalloped border (arrowheads) extending from the right second mandibular premolar to the mandibular ramus. Extensive root resorption of the right second mandibular premolar and thinning of the cortical plate is detected. Note that the inferior alveolar nerve canal has been displaced inferiorly to the inferior cortex of the mandible (arrows).

An incisional biopsy from the lesion was performed. Histopathological examination revealed several islands of odontogenic epithelium with peripheral palisading of columnar cells. These odontogenic islands were embedded in a mature collagenous stroma. The bordering cells of tumor islands displayed reversed polarization and hyperchromatic nuclei. In the central portions of the tumor islands, either enlarged granular cells or stellate-shaped cells were seen. The granular cells exhibited coarsely granular eosinophilic cytoplasm and small pyknotic nuclei (Figure 3). The size of the tumor islands in this case varied from small to large. A varying number of granular cells between tumor islands were found. Cystic degeneration was frequently found in the large tumor islands. Therefore, a diagnosis of ameloblastoma, granular cell variant, was made.

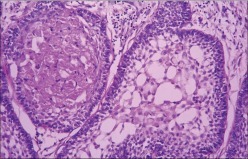

Figure 3.

Biopsy specimen reveals ameloblastomatous islands containing central large round cells with eosinophilic granules in the cytoplasm (hematoxylin and eosin stain, original magnification: ×200).

The patient was subsequently treated by partial mandibulectomy. The specimen received consisted of a right mandible with three teeth (two mandibular premolars and a mandibular canine). Confirmation of the diagnosis of granular cell ameloblastoma was done by taking several sections from the tumor mass. Bony margins of the specimens were analyzed and found to be free of tumor cells. The patient was followed up every 6 months for 2 years without any recurrence.

Materials and methods

Immunohistochemical analysis

Immunohistochemical stainings were carried out by the streptavidin–biotin peroxidase method. The sections were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated in graded ethanol solutions. Endogenous peroxidase was then blocked with 3% hydrogen peroxide for 10 min. For antibodies against laminin 1, collagen type IV and fibronectin, antigen retrieval was performed by incubating the sections with 0.4% pepsin (Sigma Chemical Co., St Louis, MO, USA) in 0.01 mol·L−1 HCl at 37 °C for 1 h. For antibodies against laminin 5, antigen retrieval was done by covering the sections with proteinase K (Dako Corporation, Carpinteria, CA, USA) at room temperature for 15 min. After washing with 0.1% Tween 20 (MERCK-Schuchardt, Hohanbrumm, Germany) in phosphate-buffered saline, the sections were treated with 2% bovine serum albumin (Sigma Chemical Co.) in phosphate-buffered saline for 30 min and then incubated with primary antibodies diluted in phosphate-buffered saline for 2 h at room temperature. The primary antibodies used were anti-collagen type IV (1∶25; Dako S/A, Glostrup, Denmark), anti-laminin 1 (1∶60; Sigma Chemical Co.), anti-laminin 5 (1∶300; Chemicon International, Temecula, CA, USA) and anti-fibronectin (1∶400; Dako S/A). Biotinylated immunoglobulin G and streptavidin–biotin peroxidase complex (strepABComplex/HRP Duet kit; Dako S/A) were applied to the sections for 30 min each. Subsequently, 3,3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (Sigma Chemical Co.) was used as a chromogen to develop the color. The sections were later counter-stained with Mayer's hematoxylin. Sections of normal oral mucosa were stained at the same run as positive control. Furthermore, a presence of positive staining with antibodies against laminin 1, collagen type IV and fibronectin in blood vessels within the tumor sections also served as an internal control. Negative control was performed by exclusion of the relevant primary antibody.

The immunoreactivity was assessed based on staining intensity. The staining intensity of positive cells was evaluated visually and classified as follows: weak intensity (W), moderate intensity (M) and strong intensity (S).

Results

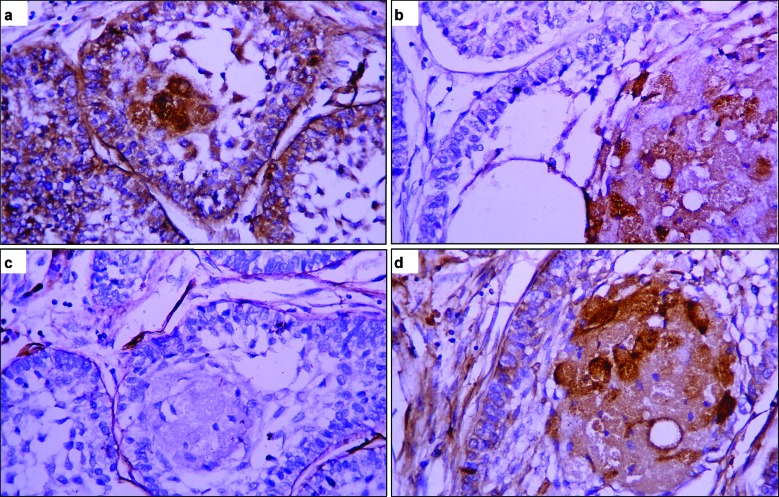

The tumor cells of granular cell ameloblastoma showed positive immunoreactivities to all proteins except for collagen type IV (Figure 4). The expression of laminins 1 and 5, collagen type IV and fibronectin is summarized in Table 1.

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemical staining of basement membrane components, including laminin 1 (a), laminin 5 (b), collagen type IV (c) and fibronectin (d) in a granular cell ameloblastoma. (a) An intense staining of laminin 1 is found in the peripheral cells, central stellate shaped-like cells and granular cells. (b) A moderate-to-strong intensity of laminin 5 is seen in granular cells. (c) A strong expression of collagen type IV is detected at the basement membrane area surrounding tumor follicles. (d) A weak to moderate staining for fibronectin is observed in peripheral cells and central cells, whereas a moderate-to-strong staining is present in granular cells (immunostaining, original magnification: ×200).

Table 1. The expression of laminins 1 and 5, collagen type IV, and fibronectin in the cytoplasm of tumor cells in a granular cell ameloblastoma.

| Staining intensity | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Examined proteins | Peripheral cells | Central cells | Granular cells |

| Laminin 1 | M to S | M | S |

| Laminin 5 | W | W | M to S |

| Collagen type IV | No staining | No staining | No staining |

| Fibronectin | W to M | W | M to S |

At the BM area surrounding tumor follicles, all examined BM proteins were detected as a thin or thick linear deposit (Figure 4). Collagen type IV showed a moderate to strong staining intensity (Figure 4c), whereas laminin 1 demonstrated a strong expression (Figure 4a). Expression of laminin 5 at the BM zone was generally weak (Figure 4b), except for only the focal area that showed a moderate staining intensity. Fibronectin exhibited a moderate staining intensity at this zone (Figure 4d). However, in some places where the tumor cells were crowded, the staining intensity was weak. At the area of tumor perforation, the epithelium of the neighboring mucosa found in the specimen showed a positive immunoreactivity to all BM studied at the BM zone, while no immunoreactivity was found in the cytoplasm of mucosal epithelial cells.

The fibrous stroma of the tumor was strongly stained for laminin 1 and fibronectin. However, the intensity of laminin 1 in the stroma was not as strong as that observed in the walls of blood vessels. Laminin 5 was weakly expressed in the stroma, whereas no expression of collagen type IV was seen in the fibrous stroma.

Discussion

This study reports a case of granular cell ameloblastoma that developed at the posterior mandible of a 44-year-old female. The age and the location of tumor of this case appear to be consistent with the study by Hartman.2 Based on a series of 20 cases of granular cell ameloblastoma, this tumor occurs at an average age of 40.7 years with no significant gender predilection and is found predominantly at the posterior region of the mandible.2 In our case, the patient had no recurrence during the 2 years after the operation, suggesting a good prognosis. The prognosis of granular cell ameloblastomas is favorable and is similar to that of the conventional ameloblastoma when the appropriate treatment was performed.4,6 Although an aggressive behavior with metastasis and recurrences of granular cell ameloblastomas have been reported, those cases were all associated with either a very long duration of the tumors or inadequate treatments at the beginning.2,19 The appropriate treatment for granular cell ameloblastoma and other histological variants of ameloblastoma is considerably the same. The most widely used treatment is marginal resection with at least 1.0 cm past the radiographic limits of the tumor.1 In case of a large tumor with extreme cortical bone destruction, the partial jaw resection is recommended.7

The histological feature of the present case showing the formation of granular cells in the follicular type of ameloblastoma is in conformity with previous reports. The granular cell ameloblastoma frequently appears in the follicular pattern in which all or a part of the stellate reticulum-like cells and, sometimes, the peripheral tumor cells are replaced by granular cells.2,20,21

The expression of BM components, including laminins 1 and 5, collagen type IV and fibronectin, has previously been studied in follicular and plexiform variants of ameloblastomas.17 With the exception of granular cells, the expressions of BM proteins in granular cell ameloblastoma are similar to those found in follicular ameloblastomas in our previous study.

The strong positivity of laminin 1 in the cytoplasm of all tumor cells, including the granular cells, was consistently found. In addition, none of mucosal epithelial cells at the region of tumor perforation was positive to laminin 1. These results support our previous notion that laminin 1 is expressed in the epithelial cells of odontogenic origin and may be a marker of odontogenic tumors.17,22 In addition, this finding further supports previous agreement that the granular cells in ameloblastoma are derived from the odontogenic epithelium, not from mesenchymal connective tissue.23 The epithelial origin of the granular cells has previously been illustrated by the positivity to cytokeratin.5,23

Interestingly, the granular cells displayed positive reactivity to laminin 5, whereas the peripheral tumor cells showed only weak reactivity to this protein. This finding suggests that laminin 5 may participate in the transformation or differentiation of granular cells. The expression of laminin 5 in granular cells of ameloblastoma of the present case is in line with previous work demonstrating mRNA expression of laminin 5 γ2 in granular cells of an ameloblastoma.15 Nevertheless, the mRNA expression of laminin 5 γ2 in the peripheral tumor cells was not mentioned.

The nature of granular cell transformation in the granular cell ameloblastomas is inconclusive. Gold and Christ believed that the cytoplasmic granules represent a metabolic process.24 However, electron microscopic and histochemical studies have indicated that the granules in the granular cells correspond to a large amount of intracytoplasmic lysosomes,3,4 the most common characteristic found in cells with senescence.25 It is likely that the granular cells in ameloblastomas represent an aging phenomenon because the average onset age of patients of the granular cell ameloblastomas is approximately 8 years older than the average onset age for the conventional ameloblastomas.2,26,27 The concept of aging process of granular cells in ameloblastomas is advocated by a long duration of this tumor. The average duration of symptoms in the granular cell ameloblastomas was 15.3 years compared to those from the conventional ameloblastomas of 2.3–5.8 years.19,26,27 Interestingly, it has been reported that the granular cells were observed 28 and 11 years after the onset of the tumors.19,28 In another case, the granular cells were recognized 22 years after the first resection.29 Although the aging process has frequently been proposed to be responsible for the granular cell transformation in ameloblastomas,3,4,19 several observations have been raised against the aging process of the granular cells such as the presence of granular cells in the recurrent tumor, which is similar to the original tumors,2 and the unchanged number of granular cells in a case of ameloblastoma after a 4-year follow-up.23

Interestingly, enhanced expression of fibronectin appears to be one of the most typical features of senescent cells.30 Fibronectin has also been proposed to be one of the biomarkers for replicative senescence.31 Increased levels of fibronectin synthesis have been observed during serial passage of skin fibroblasts, lung fibroblasts and umbilical vein endothelial cells.32,33 Thus, our present finding of increased fibronectin expression in the granular cells compared to peripheral cells is in favor of an age-related transformation. Besides the increased fibronectin expression and lysosome content, an increased cell volume34 and vimentin expression35 and a presence of senescence-associated β-galactosidase activity36 are also associated with aging phenomenon. In support of the age-related transformation of granular cells in ameloblastomas, one study reported that some granular cells in ameloblastoma were positive to vimentin.23 However, two studies did not find the expression of vimentin in the granular cells of ameloblastomas.21,37 Although the immunuhistochemical findings appear to support the aging phenomenon of the granular cells in ameloblastomas, it has to be aware that the role of replicative senescence in the aging process remains controversial.38 For example, there seems to be no clear link between telomerase repeat number and donor age in certain cell type. Post-mitotic cells in lower organisms as well as the post-mitotic tissues of higher organisms do still age.38 Taken all together, it would be of interest to further determine whether the granular cells in ameloblastomas truly represent the characteristics of aging cells.

Conclusion

We report a case of granular cell ameloblastoma developing in a follicular pattern. The patient showed a good prognosis with no sign of recurrence after treatment by partial mandibulectomy. With the exception of granular cells, the expressions of BM proteins in granular cell ameloblastoma were similar to those in follicular ameloblastomas. The strong expression of BM proteins, including laminins 1 and 5 and fibronectin, was observed in many granular cells of ameloblastoma, providing some insights into the characteristics of granular cells in this rare tumor. The lysosomal aggregates in the granular cells and the current finding of increased fibronectin expression in the granular cells led us to speculate that the granular cell transformation in granular cell ameloblastoma may be associated with the aging phenomenon.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Ekawit Boonyarangkoon (Pranakorn Sri-Ayuthaya Hospital) for providing surgical specimens, clinical photographs and radiographs. We also thank Mrs Unruen Meesakul for her technical assistance.

References

- Neville BW, Damm D, Allen C, et al. Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology3rd ed. St. Louis; Saunders Elsevier; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- Hartman KS. Granular-cell ameloblastoma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1974;38 2:241–253. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(74)90063-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noda M, Suzuki A. Ultrastructural study of granular cell ameloblastoma. Acta Pathol Jpn. 1980;30 1:145–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.1980.tb01311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasu M, Takagi M, Yamamoto H. Ultrastructural and histochemical studies of granular-cell ameloblastoma. J Oral Pathol. 1984;13 4:448–456. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1984.tb01445.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dina R, Marchetti C, Vallania G, et al. Granular cell ameloblastoma. An immunocytochemical study. Pathol Res Pract. 1996;192 6:541–546. doi: 10.1016/S0344-0338(96)80103-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo Muzio L, Mignogna MD, Staibano S, et al. Granular cell ameloblastoma: a case report with histochemical findings. Eur J Cancer B Oral Oncol. 1996;32B 3:210–212. doi: 10.1016/0964-1955(95)00096-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sciubba JJ, Fantasia J, Kahn L. Atlas of Tumors Pathology, Tumors and Cysts of the Jaw. Washington, DC; Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Altini M, Hille JJ, Buchner A. Plexiform granular cell odontogenic tumor. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1986;61 2:163–167. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(86)90180-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siar CH, Ng KH, Jalil NA. Plexiform granular cell odontogenic tumor: unicystic variant. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1991;72 1:82–85. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(91)90194-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White DK, Chen SY, Hartman KS, et al. Central granular-cell tumor of the jaws (the so-call granular-cell ameloblastic fibroma) Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1978;45 3:396–405. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(78)90525-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson AC, Couchman JR. Still more complexity in mammalian basement membranes. J Histochem Cytochem. 2000;48 10:1291–1306. doi: 10.1177/002215540004801001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiradjaja F, DiTommaso T, Smyth I. Basement membranes in development and disease. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today. 2010;90 1:8–31. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.20172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehan P, Waltregny D, Beschin A, et al. Loss of type IV collagen alpha 5 and alpha 6 chains in human invasive prostate carcinomas. Am J Pathol. 1997;151 4:1097–1104. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mostafa WZ, Mahfouz SM, Bosseila M, et al. An immunohistochemical study of laminin in basal cell carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37 1:68–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2009.01310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salo T, Kainulainen T, Parikka M, et al. Expression of laminin-5 in ameloblastomas and human fetal teeth. J Oral Pathol Med. 1999;28 8:337–342. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1999.tb02050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata M, Cheng J, Horino K, et al. Enamel proteins and extracellular matrix molecules are co-localized in the pseudocystic stromal space of adenomatoid odontogenic tumor. J Oral Pathol Med. 2000;29 10:483–490. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0714.2000.291002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poomsawat S, Punyasingh J, Vejchapipat P. Expression of basement membrane components in odontogenic tumors. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;104 5:666–675. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2006.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano K, Siar CH, Nagai N, et al. Distribution of basement membrane type IV collagen alpha chains in ameloblastoma: an immunofluorescence study. J Oral Pathol Med. 2002;31 8:494–499. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0714.2002.00162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukada Y, Delapava S, Pickren JW. Granular-cell ameloblastoma with metastasis to the lungs: report of a case and review of the literature. Cancer. 1965;18:916–925. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196507)18:7<916::aid-cncr2820180722>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumamoto H, Ooya K. Immunohistochemical and ultrastructural investigation of apoptotic cell death in granular cell ameloblastoma. J Oral Pathol Med. 2001;30 4:245–250. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0714.2001.300409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirchandani R, Sciubba JJ, Mir R. Granular cell lesions of the jaws and oral cavity: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1989;47 12:1248–1255. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(89)90718-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poomsawat S, Punyasingh J. Calcifying epithelial odontogenic tumor: an immunohistochemical case study. J Mol Histol. 2007;38 1:103–109. doi: 10.1007/s10735-007-9082-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wilde PC, Slootweg PJ, Muller H, et al. Immunocytochemical demonstration of intermediate filaments in a granular cell ameloblastoma. J Oral Pathol. 1984;13 1:29–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1984.tb01398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold L, Christ T. Granular-cell odontogenic cyst. An unreported odontogenic lesion. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1970;29 3:437–442. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(70)90147-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang ES, Yoon G, Kang HT. A comparative analysis of the cell biology of senescence and aging. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66 15:2503–2524. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0034-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichart PA, Philipsen HP, Sonner S. Ameloblastoma: biological profile of 3677 cases. Eur J Cancer B Oral Oncol. 1995;31B 2:86–99. doi: 10.1016/0964-1955(94)00037-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small IA, Waldron CA. Ameloblastomas of the jaws. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1955;8 3:281–297. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(55)90350-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoke HF, Jr, Harrelson AB. Granular cell ameloblastoma with metastasis to the cervical vertebrae. Observations on the origin of the granular cells. Cancer. 1967;20 6:991–999. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196706)20:6<991::aid-cncr2820200609>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarrette AR, Smith M. Ultrastructure of granular cell ameloblastoma. Cancer. 1971;27 4:948–955. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197104)27:4<948::aid-cncr2820270430>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fodil-Bourahla I, Drubaix I, Robert L, et al. Effect of in vitro aging on the modulation of protein and fibronectin biosynthesis by the elastin-laminin receptor in human skin fibroblasts. Gerontology. 1999;45 1:23–30. doi: 10.1159/000022051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumazaki T, Wadhwa R, Kaul SC, et al. Expression of endothelin, fibronectin, and mortalin as aging and mortality markers. Exp Gerontol. 1997;32 1/2:95–103. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(96)00080-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumazaki T, Kobayashi M, Mitsui Y. Enhanced expression of fibronectin during in vivo cellular aging of human vascular endothelial cells and skin fibroblasts. Exp Cell Res. 1993;205 2:396–402. doi: 10.1006/excr.1993.1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasoamanantena P, Thweatt R, Labat-Robert J, et al. Altered regulation of fibronectin gene expression in Werner syndrome fibroblasts. Exp Cell Res. 1994;213 1:121–127. doi: 10.1006/excr.1994.1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg SB, Grove GL, Cristofalo VJ. Cell size in aging monolayer cultures. In Vitro. 1977;13 5:297–300. doi: 10.1007/BF02616174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishio K, Inoue A, Qiao S, et al. Senescence and cytoskeleton: overproduction of vimentin induces senescent-like morphology in human fibroblasts. Histochem Cell Biol. 2001;116 4:321–327. doi: 10.1007/s004180100325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimri GP, Lee X, Basile G, et al. A biomarker that identifies senescent human cells in culture and in aging skin in vivo. . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92 20:9363–9367. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regezi JA, Zarbo RJ, Courtney RM, Crissman JD. Immunoreactivity of granular cell lesions of skin, mucosa, and jaw. Cancer. 1989;64 7:1455–1460. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19891001)64:7<1455::aid-cncr2820640716>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathon NF, Lloyd AC. Cell senescence and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2001;1 3:203–213. doi: 10.1038/35106045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]