Abstract

LFF571 is a novel semisynthetic thiopeptide antibiotic with potent activity against a variety of Gram-positive pathogens, including Clostridium difficile. In vivo efficacy of LFF571 was compared to vancomycin in a hamster model of C. difficile infection (CDI). Infection was induced in Golden Syrian hamsters using a toxigenic strain of C. difficile. Treatment started 24 h postinfection and consisted of saline, vancomycin, or LFF571. Cox regression was used to analyze survival data from a cohort of animals evaluated across seven serial experimental groups treated with vancomycin at 20 mg/kg, LFF571 at 5 mg/kg, or vehicle alone. Survival was right censored; animals were not observed beyond day 21. At death or end of study, cecal contents were tested for C. difficile toxins A and B. In summary, the data showed that 5 mg/kg LFF571 decreased the risk of death by 79% (P < 0.0001) and 69% (P = 0.0022) compared with saline and 20 mg/kg vancomycin, respectively. Further analysis of the pooled data indicated that the survival benefit of LFF571 treatment at 5 mg/kg compared to vancomycin at 20 mg/kg was due primarily to a decrease in the risk of recurrence after end of treatment. Animals successfully treated with LFF571 or vancomycin had no detectable C. difficile toxin. Overall, LFF571 was more efficacious at the end of the study, at a lower dose, and with fewer recurrences, than vancomycin in the hamster model of CDI. LFF571 is being assessed in humans for safety and efficacy in the treatment of C. difficile infections.

INTRODUCTION

The bacterial elongation factor Tu (EF-Tu) is an essential and highly conserved chaperone that is required for protein synthesis. EF-Tu forms a ternary complex with GTP and aminoacylated tRNA (aa-tRNA) and then delivers the aa-tRNA to the receptor (“A”) site of the elongating ribosome (16). The natural thiopeptide antibiotic GE2270 A inhibits the function of EF-Tu by interfering with the binding of aa-tRNA and is potent against a broad spectrum of Gram-positive bacterial pathogens (29). LFF571 is a novel, semisynthetic derivative of GE2270 A that also inhibits bacterial translation, as shown in the accompanying article (20a). LFF571 has improved physicochemical properties (20; S. Bushell, M. J. LaMarche, J. A. Leeds, and L. Whitehead, 18 June 2009, international patent application WO 2009/074605) while retaining potent antibacterial activity against important pathogens, including the Gram-positive anaerobic sporeformer Clostridium difficile (8, 13). C. difficile is the leading cause of antibiotic-associated infectious diarrhea (24). Disease caused by the bacteria ranges from mild and self-limiting to severe, life-threatening pseudomembranous colitis (14). Therapy for patients with C. difficile infection (CDI) includes treatment with vancomycin or metronidazole (9), agents that inhibit the growth of the pathogen but often fail to prevent recurrence of disease after treatment. Recently, the FDA approved fidaxomicin for treatment of CDI. In clinical trials comparing fidaxomicin to vancomycin, fidaxomicin reduced recurrence in patients infected with many strains of C. difficile, but not the epidemic and highly toxigenic strain B1/NAP1/027 (10, 21).

LFF571 is more potent than vancomycin against C. difficile in vitro (MICs against 90% of isolates studied [MIC90s] of ≤0.5 μg/ml and ≤2 μg/ml, respectively) (8, 15). This potency across a range of C. difficile isolates prompted us to evaluate oral LFF571 versus oral vancomycin in the Golden Syrian hamster model of CDI. Although disease progression is more rapid and more lethal in this model than is typically observed in humans, the hamster model for CDI is useful for evaluating the dose-response relationship of an experimental therapy in the treatment phase and for monitoring recurrence of disease following the end of therapy (28). Comparisons can be made with standards of care, and combined with in vitro susceptibility and pharmacokinetic data, the model has been used to support the progression of clinical candidates into human efficacy studies (1, 18, 21). Here, we established a dose-response relationship for LFF571 in the hamster model of CDI and then compared the efficacy of 5 mg/kg LFF571 to 20 mg/kg vancomycin, via statistical analysis of a cohort of animals treated across seven serial experiments, to determine the impact of a therapeutic dose of LFF571 on recurrence of CDI in hamsters following end of therapy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antimicrobial agents.

LFF571 was synthesized at Novartis using published methods (20; Bushell et al., international patent application WO 2009/074605). Clindamycin was purchased from MP Biomedicals, and vancomycin was obtained from Sigma. The agar MICs for LFF571 and vancomycin against the animal model strain of C. difficile (ATCC 43255) were 0.25 μg/ml and 1 μg/ml, respectively (13).

Bacterial strain.

C. difficile (ATCC 43255), which was previously validated in the hamster model (1), was stored at −70°C in brucella broth supplemented with vitamin K1 (1 μg/ml), hemin (5 μg/ml), 5% lysed horse blood, and 20% glycerol.

Clindamycin-induced C. difficile colitis model.

Male Golden Syrian hamsters, purchased from Harlan (Indianapolis, IN), were pretreated 24 h prior to infection with a single subcutaneous injection of clindamycin at 10 mg/kg. On the day of infection (day 0), animals were inoculated by oral gavage with approximately 106 C. difficile vegetative cells per hamster. C. difficile inoculum was prepared by growing the bacteria in Difco reinforced clostridial medium with 1% Oxyrase for 24 h under anaerobic conditions. The optical density at 600 nm (OD600) was adjusted to 1.5 and then diluted 1:10. The hamsters were administered 0.75 ml of this suspension orally. An aliquot of the inoculum was then serially diluted, plated on brucella agar supplemented with hemin and vitamin K1 (Remel, Lenexa, KS), and incubated anaerobically for 48 h in an airtight container (Pack-Anaero MGC) to determine the infection titer.

Antibiotic treatment.

Saline, vancomycin (20 mg/kg), or LFF571 (0.2, 1, 2, 5, or 10 mg/kg) was administered orally beginning 24 h after infection. All seven experiments included the 5-mg/kg LFF571 dose group as well as 2 to 3 other dose groups. Treatment continued once daily, for a total of 5 days, unless animals died or were sacrificed moribund.

Animal observations.

Studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Novartis Institutes for BioMedical Research, Inc., Cambridge, MA. Animals were singly housed in 7.5-in.-wide by 6-in.-deep cages with corn cob bedding and free access to water and standard rodent chow; environmental conditions included 12-h-dark/12-h-light cycles, 20 to 22°C constant temperature, 50% relative humidity, and 10 to 15 exchanges of fresh HEPA filter air per hour. Animals were observed twice daily for 24 h postinfection and then every 2 h for the following 24 h during the acute phase of disease, followed by twice daily for the remainder of the study (up to 21 days postinfection). If the animals showed signs of disease at any time, the frequency of observations was increased. General observations included signs of mortality and morbidity, presence of diarrhea (“wet tail”), and overall appearance (activity, general response to handling, touch, or ruffled fur); body weights were taken every 2 to 3 days. Animals were euthanized if judged to be in a moribund state by the following criteria: extended periods (5 days) of weight loss, signs of paralysis, skin erosions or trauma, hunched posture, and a distended abdomen. Moribund animals underwent necropsy and had the contents of their ceca removed. These samples were diluted with an equal volume of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and frozen at −70°C until processing. All surviving animals were euthanized by CO2 inhalation and used for sampling of ceca as described above.

Statistical analysis.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves were computed and displayed for each of the three treatment groups. Survival differences between the three groups were explored by the Cox regression model. A random frailty variable was included for modeling the within-experiment correlation (33). A gamma distribution with mean 1 and unknown variance was chosen for the frailty. The model was fitted using the Cox proportional hazard library function of R version 2.8.2.

Measurement of C. difficile toxins A and B.

Cecum homogenates were assayed for the presence of C. difficile toxins A and B using the Wampole C. difficile Tox A/B II enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit in accordance with the manufacturer's directions. Lower limits of quantification were >0.8 ng/ml for toxin A and 2.5 ng/ml for toxin B.

RESULTS

Efficacy of LFF571 in the hamster model of C. difficile infection.

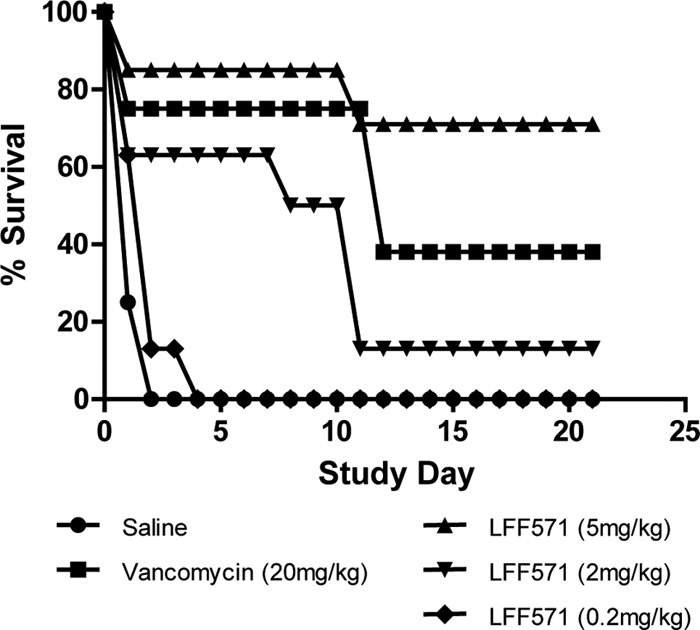

The Golden Syrian hamster model was used to evaluate the efficacy of LFF571, compared to the standard-of-care vancomycin, during the treatment and recurrent phases of CDI. Seven serial studies were conducted to determine the efficacy of LFF571 compared to vancomycin or vehicle alone and to monitor the dose responses of LFF571. Figure 1 shows a representative experiment in which LFF571 (5, 2, and 0.2 mg/kg) was compared to vehicle alone and vancomycin at 20 mg/kg. All of the vehicle-treated animals died by the end of day 2. In the group dosed with 5 mg/kg LFF571, 5 out of 7 (71%) hamsters remained alive on day 21; the eighth animal in the group was excluded from study on day 1 due to an abscess on the testicle. In the LFF571 2-mg/kg treatment group, 1 out of 8 animals (12.5%) survived, while all 8 animals died in the LFF571 0.2-mg/kg-treated group. In the vancomycin (20-mg/kg)-treated group, 2 out of 8 (25%) animals died on day 1, 37.5% succumbed to recurrent disease on day 12, and the remaining 37.5% survived until day 21. All animals surviving to day 21 had no detectable levels of C. difficile toxins A and B in their cecal contents when measured at the end of the study, whereas all of the animals that died during the study period were positive for toxins A and B.

Fig 1.

Dose response of LFF571 in the hamster model of C. difficile infection. A representative experiment comparing LFF571 at doses of 5, 2, and 0.2 mg/kg to vehicle alone (saline) and vancomycin at 20 mg/kg. Animals were infected with approximately 106 C. difficile vegetative cells on study day 0 and treatment was administered once daily from study days 1 to 5. Animals were observed up to study day 21.

Statistical analysis of the efficacy of LFF571 versus vancomycin.

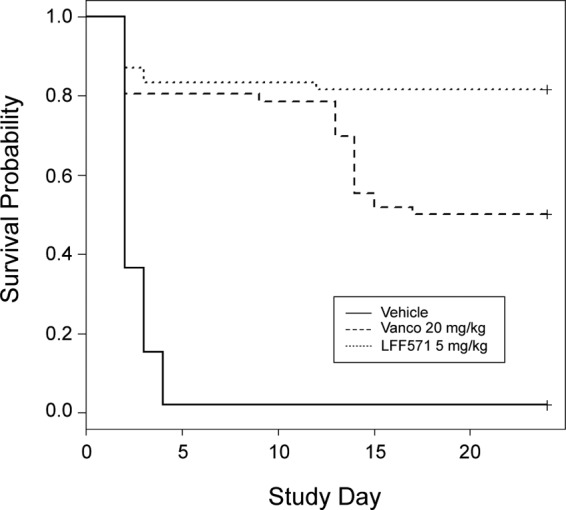

The survival data from the cohort of animals receiving the LFF571 5-mg/kg dose in the seven serial studies were compared to the survival data from the animals receiving the vancomycin 20-mg/kg dose or vehicle alone. Across all seven studies, LFF571 was consistently more efficacious at the end of the study, at a lower dose, than vancomycin. Whereas 37.8% of the total number of animals alive at end of treatment with 20 mg/kg vancomycin suffered a recurrence in disease, this was only observed in 2.2% of animals alive at the end of treatment with 5 mg/kg of LFF571. The statistical analyses of the censored survival times across the cohort of animals are summarized in Tables 1 and 2 and Fig. 2. The survival times are right censored; animals alive beyond day 21 were not observed further. The number of deaths and time to death or censoring are shown in Table 1. The number of surviving animals and time to death were markedly lower in the vehicle-treated group than those in the 5-mg/kg LFF571 and 20-mg/kg vancomycin-treated groups. The presence of censoring makes it inappropriate to base inference on the summary data in Table 1. In order to discern the difference in survival between the vehicle- and 5-mg/kg LFF571-treated groups, Cox proportional hazards models were employed. The estimated changes in proportional hazard between the LFF571 (5-mg/kg)-treated group and the vancomycin (20-mg/kg)- or vehicle-treated groups are shown in Table 2. Based on the analysis, the hazard of the death of hamsters falls by 79% when comparing treatment with vehicle to treatment with 5 mg/kg LFF571 (P < 0.0001). Furthermore, the hazard falls by 69% when comparing treatment with vancomycin at 20 mg/kg to treatment with LFF571 at 5 mg/kg (P = 0.0022). This interpretation is also supported by the clear separation of the data in the graph of survival probability as a function of study day (Fig. 2). These data suggest that the survival difference between treatment with vancomycin (20 mg/kg) and treatment with LFF571 (5 mg/kg) mainly appears after the end of dosing. Hence, it is reasonable to hypothesize that this survival difference represents a change in the death hazard postdosing. In order to investigate this hypothesis, a different Cox regression model was fitted to the data (33). In this analysis, only animals surviving at day 5 (end of treatment) were included. This model (Table 2) suggests that there is an overall decrease in recurrence hazard of roughly 95% from vancomycin at 20 mg/kg to LFF571 at 5 mg/kg (P = 0.0024).

Table 1.

Summary of pooled survival hamster data from seven individual studies

| Treatment | n | No. of deaths | Mean (SE) days to death or censoring |

|---|---|---|---|

| LFF571 (5 mg/kg) | 54 | 10 | 17.52 (1.02) |

| Vancomycin (20 mg/kg) | 56 | 28 | 14.55 (1.03) |

| Control | 52 | 51 | 1.87 (0.39) |

Table 2.

Estimated decrease in proportional hazard of death or recurrence hazard

| Covariate | % decrease in hazard | 95% confidence interval (%) | P value for difference from 1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proportional hazard of death | |||

| From vehicle to LFF571 (5 mg/kg) | 79 | 68–86 | <0.0001 |

| From vancomycin (20 mg/kg) to LFF571 (5 mg/kg) | 69 | 34–85 | 0.0022 |

| Recurrence hazard | |||

| From vancomycin (20 mg/kg) to LFF571 (5 mg/kg) | 95 | 67–99 | 0.0024 |

Fig 2.

Survival plot of pooled data from hamster C. difficile infection studies. Statistical analyses of survival times across the cohort of animals from seven studies receiving LFF571 (5 mg/kg) compared to vancomycin (20 mg/kg) or vehicle alone (saline). Survival times are right censored; animals alive beyond day 21 were not observed further.

DISCUSSION

The Golden Syrian hamster model is routinely used to study the impact of antibiotic therapy on the course of C. difficile infection (3, 4, 12, 18, 30). It is one of the few in vivo models that recapitulates aspects of C. difficile infection in humans, including the recurrence stage following a course of antibiotic treatment (7, 27). Similar to C. difficile infection in humans, clindamycin-induced CDI in hamsters shows a comparable shift in the gut flora toward a proliferation of clostridial species (4). Hamsters also exhibit histological changes, such as pseudomembrane lesions (2), similar to those found in human patients.

While the hamster model is useful for studying some aspects of CDI, the model diverges from human disease in several important ways. First, there is a high level of mortality in the hamster model that is not seen in the human clinical syndrome (28). In addition, some studies with non-antibiotic-based therapies have shown discordance between drug activity in hamsters and efficacy in humans (19). Finally, the variability of comparator dosages used in this model across reported studies and the lack of a clear correlation with human dose/response make it difficult to justify one dose over another. For example, when evaluating vancomycin in the hamster model, dosages from 5 mg/kg to 50 mg/kg have been employed (1, 11, 12, 18, 23, 25, 26, 30, 31). In the experiments reported here, 20 mg/kg vancomycin was chosen as the comparator based upon preliminary dose-response experiments used to set up our specific model (data not shown). This dose resulted in an 82.1% end-of-treatment survival rate, and recurrence occurred within a window of time that is historically observed in reports using this strain of C. difficile (1, 12, 18). Nevertheless, the 37.8% recurrence of CDI observed in this study for animals treated with 20 mg/kg vancomycin is not reflective of the recurrence rate in human CDI, which is reported to be historically around 18% (17), with recent clinical trials demonstrating recurrence rates approaching 25% (5, 21, 22). For all of these reasons, we acknowledge the possibility that vancomycin was underdosed in the experiments described in this report compared to other animal studies reported in the literature, as well as in comparison to human therapy.

As discussed above, the high lethality observed in the hamster model of CDI necessitates large numbers of animals for statistical analyses. For logistical reasons, we divided the cohort into seven serial studies and maintained the 5-mg/kg LFF571 dose and 20-mg/kg vancomycin dose across all studies. Combined analysis of these studies was conducted using the “frailty model” (33), which allows variability between experiments to be taken into account when simple pooling of the data is inappropriate. The essence of this analysis, which is commonly used for human survival data (32), is to treat the variability between experiments as a variance component while estimating the treatment effect from all data. We also performed an alternative analysis, comparing pooled survival rates by contingency table analysis using the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel method. This analysis is less powerful than the frailty model, in that it reduces the data to a binary indicator of death or survival; however, similar results were obtained with both methods.

In the reported analyses of in vivo efficacy studies, LFF571 was more efficacious at the end of study, and at a lower dose, than vancomycin. The analyses demonstrate a clear difference in survival (as measured by a proportional hazard difference) between the placebo-treated and 5-mg/kg LFF571-treated group (79% proportional hazard decrease from placebo to LFF571) and between the 20-mg/kg vancomycin- and 5-mg/kg LFF571-treated groups (69% proportional hazard decrease). Furthermore, the data substantiate that the survival benefit of LFF571 over vancomycin can be explained as a decrease in death hazard after day 5 (modeling a separate change in proportional hazard after day 5 shows a 95% decrease from vancomycin to LFF571). One explanation for this is that the relapse rate following treatment with 5 mg/kg LFF571 is improved over that following treatment with 20 mg/kg vancomycin. These results support further development of LFF571 for the treatment of C. difficile infections.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Donghui Yu, Sharee Pettiford, Megan Gaston, and Kathryn Kelley from the Novartis Institute for BioMedical Research for technical assistance and contributions to the project and Akash Jain from Novartis Technical Research and Development for assistance with compound formulation. We thank Catherine Jones for editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 29 May 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Anton PM, et al. 2004. Rifalazil treats and prevents relapse of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea in hamsters. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:3975–3979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bartlett JG. 2008. Historical perspectives on studies of Clostridium difficile and C. difficile infection. Clin. Infect. Dis. 46(Suppl 1):S4–S11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bartlett JG, Chang TW, Gurwith M, Gorbach SL, Onderdonk AB. 1978. Antibiotic-associated pseudomembranous colitis due to toxin-producing clostridia. N. Engl. J. Med. 298:531–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bartlett JG, Onderdonk AB, Cisneros RL, Kasper DL. 1977. Clindamycin-associated colitis due to a toxin-producing species of Clostridium in hamsters. J. Infect. Dis. 136:701–705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bouza E, et al. 2008. Results of a phase III trial comparing tolevamer, vancomycin and metronidazole in patients with Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhoea. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 14:S103–S104 [Google Scholar]

- 6. Reference deleted.

- 7. Chang JY, et al. 2008. Decreased diversity of the fecal microbiome in recurrent Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea. J. Infect. Dis. 197:435–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Citron DM, Tyrrell KL, Merriam CV, Goldstein EJ. 2012. Comparative in vitro activities of LFF571 against Clostridium difficile and 630 other intestinal strains of aerobic and anaerobic bacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:2493–2503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cohen SH, et al. 2010. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults: 2010 update by the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA). Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 31:431–455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cornely OA, et al. 2012. Fidaxomicin versus vancomycin for infection with Clostridium difficile in Europe, Canada, and the USA: a double-blind, non-inferiority, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 12:281–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dong MY, Chang TW, Gorbach SL. 1987. Treatment of Clostridium difficile colitis in hamsters with a lipopeptide antibiotic, LY146032. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 31:1135–1136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dvoskin S, et al. 2012. A novel agent effective against Clostridium difficile infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:1624–1626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dzink-Fox J, et al. 2011. Antimicrobial activity of the novel elongation factor Tu inhibitor, LFF571, abstr F1-1346. Abstr. 51st Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., Chicago, IL [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gerding DN, Johnson S, Peterson LR, Mulligan ME, Silva J., Jr 1995. Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea and colitis. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 16:459–477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hecht D, Osmolski J, Gerding D. 2012. Activity of LFF571 against 103 clinical isolates of C. difficile, abstr P-1440. Abstr. 22nd Eur. Soc. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis., London, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hogg T, Mesters JR, Hilgenfeld R. 2002. Inhibitory mechanisms of antibiotics targeting elongation factor Tu. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 3:121–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kelly CP, LaMont JT. 2008. Clostridium difficile—more difficult than ever. N. Engl. J. Med. 359:1932–1940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kokkotou E, et al. 2008. Comparative efficacies of rifaximin and vancomycin for treatment of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea and prevention of disease recurrence in hamsters. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:1121–1126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kurtz CB, et al. 2001. GT160-246, a toxin binding polymer for treatment of Clostridium difficile colitis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:2340–2347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. LaMarche MJ, et al. 2012. Discovery of LFF571: an investigational agent for Clostridium difficile infection. J. Med. Chem. 55:2376–2387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20a. Leeds JA, Sachdeva M, Mullin S, Dzink-Fox J, LaMarche MJ. 2012. Mechanism of action of and mechanism of reduced susceptibility to the novel anti-Clostridium difficile compound LFF571. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:4463–4465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Louie TJ, et al. 2011. Fidaxomicin versus vancomycin for Clostridium difficile infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 364:422–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lowy I, et al. 2010. Treatment with monoclonal antibodies against Clostridium difficile toxins. N. Engl. J. Med. 362:197–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mathur T, et al. 2011. Activity of RBx 11760, a novel biaryl oxazolidinone, against Clostridium difficile. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66:1087–1095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. McGlone SM, et al. 2012. The economic burden of Clostridium difficile. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 18:282–289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. McVay CS, Rolfe RD. 2000. In vitro and in vivo activities of nitazoxanide against Clostridium difficile. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:2254–2258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ochsner UA, et al. 2009. Inhibitory effect of REP3123 on toxin and spore formation in Clostridium difficile, and in vivo efficacy in a hamster gastrointestinal infection model. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 63:964–971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. O'Neill GL, Beaman MH, Riley TV. 1991. Relapse versus reinfection with Clostridium difficile. Epidemiol. Infect. 107:627–635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sambol SP, Merrigan MM, Tang JK, Johnson S, Gerding DN. 2002. Colonization for the prevention of Clostridium difficile disease in hamsters. J. Infect. Dis. 186:1781–1789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Selva E, et al. 1991. Antibiotic GE2270 a: a novel inhibitor of bacterial protein synthesis. I. Isolation and characterization. J. Antibiotics 44:693–701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Swanson RN, et al. 1991. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of tiacumicins B and C against Clostridium difficile. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 35:1108–1111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Swanson RN, et al. 1989. Phenelfamycins, a novel complex of elfamycin-type antibiotics. III. Activity in vitro and in a hamster colitis model. J. Antibiotics 42:94–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Therneau T, Grambsch P. 2000. Modeling survival data: extending the Cox model. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany [Google Scholar]

- 33. Therneau T, Grambsch P, Pankratz V. 2003. Penalized survival models and frailty. J. Comput. Graph. Stat. 12:156–175 [Google Scholar]