Abstract

The therapeutic activity of intramuscular (IM) peramivir was evaluated in mice infected with a recombinant influenza A/WSN/33 virus containing the H275Y neuraminidase (NA) mutation known to confer oseltamivir resistance. Regimens consisted of single (90 mg/kg of body weight) or multiple (45 mg/kg daily for 5 days) IM peramivir doses that were initiated 24 h or 48 h postinfection (p.i.). An oral oseltamivir regimen (1 or 10 mg/kg daily for 5 days) was used for comparison. Untreated animals had a mortality rate of 75% and showed a mean weight loss of 16.9% on day 5 p.i. When started at 24 h p.i., both peramivir regimens prevented mortality and significantly reduced weight loss (P < 0.001) and lung viral titers (LVT) (P < 0.001). A high dose (10 mg/kg) of oseltamivir initiated at 24 h p.i. also prevented mortality and significantly decreased weight loss (P < 0.05) and LVT (P < 0.001) compared to the untreated group results. In contrast, a low dose (1 mg/kg) of oseltamivir did not show any benefits. When started at 48 h p.i., both peramivir regimens prevented mortality and significantly reduced weight loss (P < 0.01) and LVT (P < 0.001) whereas low-dose or high-dose oseltamivir regimens had no effect on mortality rates, body weight loss, and LVT. Our results show that single-dose and multiple-dose IM peramivir regimens retain clinical and virological activities against the A/H1N1 H275Y variant despite some reduction in susceptibility when assessed in vitro using enzymatic assays. IM peramivir could constitute an alternative for treatment of oseltamivir-resistant A/H1N1 infections, although additional studies are warranted to support such a recommendation.

INTRODUCTION

Influenza viruses are responsible for potentially severe respiratory tract infections that affect individuals of all age groups (34). Each year, seasonal influenza epidemics can be associated with up to 1 billion infections worldwide, causing an average of 3 million to 5 million severe cases and up to 500,000 deaths (17). Influenza A viruses may also occasionally cause pandemics with a more devastating impact in terms of mortality and morbidity (34). Although immunization programs remain the primary means for the prevention of influenza virus infections, antigenic drift with mismatches between vaccine strains and circulating viruses as well as inadequate immune responses in some individuals may considerably limit the efficacy of current vaccines (20). Therefore, antivirals can play a major role for the control and prevention of influenza virus infections during either epidemics or pandemics.

Among anti-influenza agents, neuraminidase inhibitors (NAIs) constitute the antiviral class of choice. Their clinical importance was highlighted by reports showing that most seasonal A/H3N2 viruses isolated after 2005 (12), more than 95% of A/H5N1 viruses isolated in Vietnam and Thailand (15), and all A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses (13) were resistant to the other class of anti-influenza agents, i.e., the adamantanes. Two NAIs have been approved in many countries for more than a decade: inhaled zanamivir (Relenza; GlaxoSmithKline) and oral oseltamivir (Tamiflu; Hoffmann LaRoche) (1). Peramivir is a cyclopentane analogue NAI which demonstrated in vitro activity against influenza A and B viruses, including the recent A(H1N1)pdm09 pandemic strain, A/H5N1, and A/H9N2 viruses (6, 18, 28). NA inhibition assays showed that seasonal influenza A and B strains were more susceptible to peramivir (with lower 50% inhibitory concentrations [IC50s]) than to oseltamivir and zanamivir (11, 19, 21). A similar observation was made for A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses, for which the mean IC50 for peramivir was 0.06 nM compared to 0.26 nM and 0.21 nM for zanamivir and oseltamivir, respectively (28).

Despite such excellent in vitro activity, oral peramivir demonstrated only modest clinical benefits in controlled trials of prophylaxis and treatment (8). This could be attributed to the relatively low blood concentrations achieved following oral administration of the drug. Consequently, subsequent studies were performed with parenteral routes of administration. Preclinical studies in mice and ferrets demonstrated that intramuscular (IM) and intravenous (IV) administrations of peramivir rapidly produced high plasma concentrations (7, 26, 35). Accordingly, clinical trials confirmed that IM or IV peramivir elicited significantly higher plasma concentration levels (4,000 to 15,000 ng/ml) than those seen after administration of oral oseltamivir (∼350 ng/ml) (32). IV peramivir has been approved for the treatment of influenza in Japan and South Korea, whereas the drug is currently undergoing phase III trials in the United States. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) provisionally authorized the use of IV peramivir between October 2009 and June 2010 for the treatment of severe A(H1N1)pdm09 cases (10).

As NAIs target the same enzyme with similar mechanisms of action, the emergence of cross-resistance may be a major clinical concern (3). We previously demonstrated that in vitro passages of the influenza A/WSN/33 (H1N1) strain under peramivir pressure resulted in the emergence of the H275Y NA mutation (N1 numbering) (9). This well-known mutation has also emerged during oseltamivir treatment in patients infected with A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses (13) as well as A/H5N1 variants (16). In addition, most seasonal A/Brisbane/59/2007 (H1N1)-like viruses isolated in 2008 to 2009 contained the H275Y NA mutation (21, 23). As the H275Y mutation confers only moderate levels of resistance to peramivir in the A/WSN/33 (H1N1) background (48-fold increase in IC50, i.e., from 0.25 nM to 12.18 nM compared to the wild type [WT] versus a 427-fold increase in oseltamivir IC50, i.e., from 1.03 to 440 nM) (2) and considering that high peramivir concentrations could be achieved in plasma after parenteral administration, a rationale was made for possible use of IM or IV administration of peramivir against A/H1N1 variants with the H275Y mutation. Indeed, we demonstrated the prophylactic effect of IM injections of peramivir in mice infected with a recombinant influenza A/WSN/33 (H1N1) virus containing the H275Y NA mutation (4). The objective of the present study was to investigate whether IM peramivir could be also protective when therapy was delayed 24 to 48 h after viral challenge, which better mimics clinical conditions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The recombinant influenza A/WSN/33 (H1N1) WT virus and its NA H275Y variant were previously generated using reverse genetics (2). Groups of 12 18-to-22-g female BALB/c mice (Charles River, Lasalle, Quebec City, Canada) were housed four per cage and kept under conditions which prevented cage-to-cage infections. In two separate experiments, mice were inoculated intranasally, under isoflurane anesthesia, with 6.9 × 103 PFU (24-h treatment delay; Table 1) or 8 × 103 PFU (48-h treatment delay; Table 2) of recombinant A/WSN/33 (H1N1) WT virus in 30 μl of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). In another experiment, mice were similarly inoculated with 5.7 × 103 PFU of the recombinant A/WSN/33 (H1N1) H275Y NA mutant (24-h treatment delay [Table 3] and 48-h treatment delay [Table 4]). Peramivir (Biocryst, Birmingham, AL) was administered intramuscularly (i.e., by hip injection) starting at 24 or 48 h after viral challenge. One group of infected animals was left untreated, whereas other groups received either a single dose (90 mg/kg of body weight) or multiple doses (45 mg/kg once daily for 5 days) of peramivir. Oral oseltamivir (Hoffmann-La Roche, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada) treatment regimens (1 mg/kg or 10 mg/kg by gavage once daily for 5 days) were also investigated for comparison. Finally, 8 uninfected and untreated mice were used as controls. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care Committee at Laval University according to guidelines of the Canadian Council on Animal Care.

Table 1.

Impact of NAI therapy starting at 24 h postinfection in mice infected with a recombinant A/WSN/33 (H1N1) WT virusa

| Regimen | % mortality on day 12 p.i. (n = 8) | Mean % wt loss ± SD on day 5 p.i. (n = 11–12) | Mean lung viral titer (PFU/ml) ± SD on day 5 p.i. (n = 4) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uninfected/untreated | 0*** | −3.5 ± 0.7*** | Nd |

| Untreated-infected | 75 | 15.6 ± 1.5 | 2.85 × 105 ± 0.1 × 105 |

| Oseltamivir 5 × 1 mg/kg | 0*** | 7.2 ± 1.2** | 1.3 × 102 ± 0.65 × 102*** |

| Peramivir 1 × 90 mg/kg | 0*** | −2.5 ± 0.9*** | 4 × 101 ± 1 × 101*** |

| Peramivir 5 × 45 mg/kg | 0*** | −2.6 ± 1.1*** | 0.66 × 101 ± 0.11 × 101*** |

**, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 (versus the untreated group). Statistical significance was determined by using Kaplan-Meier analysis for mortality and a one-way ANOVA test for weight loss and lung viral titers. Nd, not determined. The viral inoculum was 6.9 × 103 PFU.

Table 2.

Impact of NAI therapy starting at 48 h postinfection in mice infected with a recombinant A/WSN/33 (H1N1) WT virusa

| Regimen | % mortality on day 12 p.i. (n = 8) | Mean % wt loss ± SD on day 5 p.i. (n = 11–12) | Mean lung viral titer (PFU/ml) ± SD on day 5 p.i. (n = 4) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uninfected/untreated | 0*** | −2.8 ± 0.7*** | Nd |

| Untreated-infected | 100 | 20.4 ± 1.1 | 1.6 × 106 ± 0.6 × 106 |

| Oseltamivir 5 × 1 mg/kg | 0*** | 5.3 ± 0.8*** | 6.6 × 101 ± 6.4 × 101*** |

| Oseltamivir 5 × 10 mg/kg | 0*** | 4.4 ± 1*** | 8.6 × 101 ± 4.6 × 101*** |

| Peramivir 1 × 90 mg/kg | 0*** | 1.5 ± 0.7*** | 2 × 101 ± 0*** |

| Peramivir 5 × 45 mg/kg | 0*** | 2 ± 0.8*** | 2 × 101 ± 0*** |

***, P < 0.001 versus the untreated group. Statistical significance was determined by using Kaplan Meier analysis for mortality and the one-way ANOVA test for weight loss and lung viral titers. Nd, not determined. The viral inoculum was 8 × 103 PFU.

Table 3.

Impact of NAI therapy starting at 24 h postinfection in mice infected with a recombinant A/WSN/33 (H1N1) H275Y virusa

| Regimen | % mortality on day 12 p.i. (n = 8) | Mean % wt loss ± SD on day 5 p.i. (n = 11–12) | Mean lung viral titer (PFU/ml) ± SD on day 5 p.i. (n = 4) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uninfected/untreated | 0*** | −1.2 ± 1.1*** | Nd |

| Untreated-infected | 75 | 16.9 ± 1.5 | 3.66 × 106 ± 0.11 × 106 |

| Oselamivir 5 × 1 mg/kg | 75 | 14 ± 1.4 | 3.0 × 106 ± 0.09 × 106 |

| Oseltamivir 5 × 10 mg/kg | 0*** | 11.9 ± 1* | 2.0 × 105 ± 0.44 × 105*** |

| Peramivir 1 × 90 mg/kg | 0*** | −0.6 ± 0.9*** | 8.0 × 102 ± 5.29 × 102*** |

| Peramivir 5 × 45 mg/kg | 0*** | −1.3 ± 1.1*** | 2.2 × 103 ± 0.6 × 103*** |

*, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001 (versus the untreated group). Statistical significance was determined by using Kaplan-Meier analysis for mortality and the one-way ANOVA test for weight loss and lung viral titers. Nd, not determined. The viral inoculum was 5.7 × 103 PFU.

Table 4.

Impact of NAI therapy starting at 48 h postinfection in mice infected with a recombinant A/WSN/33 (H1N1) H275Y virusa

| Regimen | % mortality on day 12 p.i. (n = 8) | % wt loss ± SD on day 5 p.i. (n = 11–12) | Mean lung viral titer (PFU/ml) ± SD on day 5 p.i. (n = 4) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uninfected/untreated | 0*** | −1.2 ± 1.1*** | Nd |

| Untreated/infected | 75 | 16.9 ± 1.5 | 3.66 × 106 ± 0.11 × 106 |

| Oseltamivir 5 × 1 mg/kg | 100 | 18.3 ± 0.7 | 2.2 × 106 ± 0.52 × 106 |

| Oseltamivir 5 × 10 mg/kg | 62.5 | 16.5 ± 1.5 | 1.46 × 106 ± 0.41 × 106 |

| Peramivir 1 × 90 mg/kg | 0*** | 7.9 ± 0.9*** | 2.8 × 104 ± 0.7 × 104* |

| Peramivir 5 × 45 mg/kg | 0*** | 9.4 ± 1.4** | 3 × 103 ± 1.8 × 103*** |

*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 (versus the untreated group). Statistical significance was determined by using Kaplan-Meier analysis for mortality and the one-way ANOVA test for weight loss and viral lung titers. Nd, not determined. The viral inoculum was 5.7 × 103 PFU.

Mice were monitored daily for body weight loss, and mortality was recorded over a period of 12 days. For determination of lung viral titers (LVTs), subgroups of 4 mice were sacrificed on day 5 postinfection (p.i.), and then their lungs were removed aseptically and homogenized in 1 ml of sterile PBS containing antibiotics. Lung homogenates were then centrifuged at 600 × g for 10 min, and supernatants were titrated in Madin-Darby bovine kidney (MDBK) cells by using a standard plaque assay.

Mortality rates of the groups were compared with Kaplan-Meier analysis. The one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test was used to compare mean weight losses on day 5 p.i. and LVTs of the different treatment regimen groups.

RESULTS

Effect of 24-h delay of treatment on influenza A/WSN/33 (H1N1) WT virus.

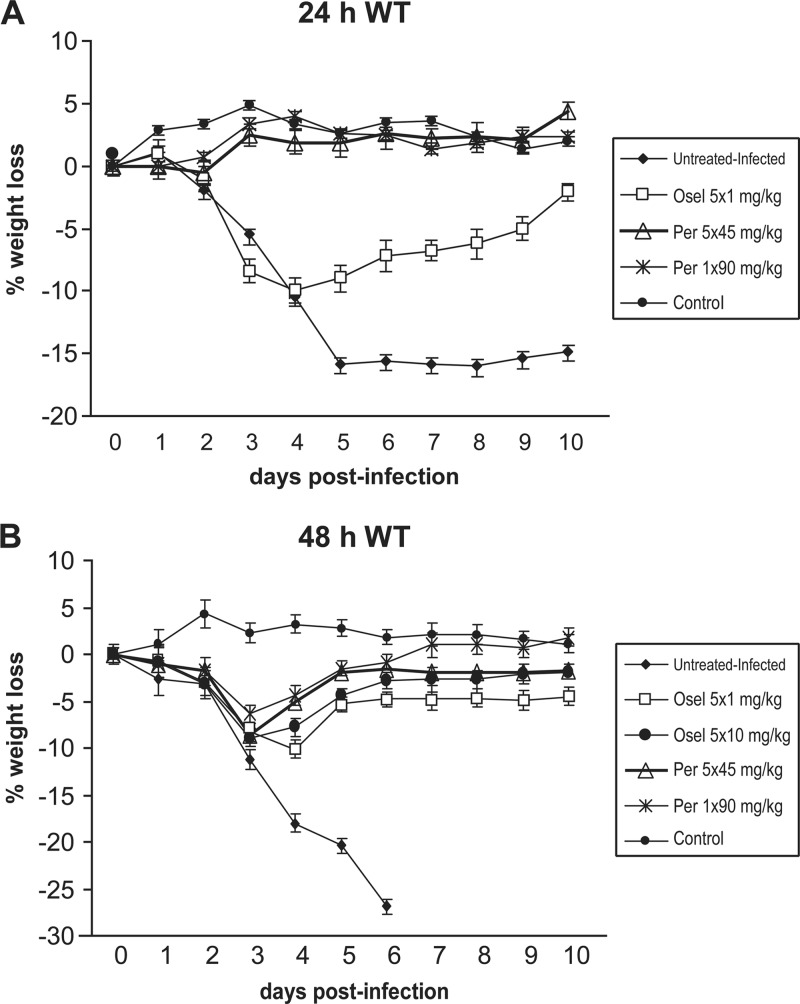

Intranasal inoculation of mice with 6.9 × 103 PFU of the recombinant WT virus resulted in a mortality rate of 75% (6/8), with a mean number of days to death (MDD) of 5 days ± 0. For the 24 h p.i. protocol (Table 1), no mortality was recorded in the low-dose (1 mg/kg) oseltamivir-treated group (the 10 mg/kg dose of oseltamivir was not included in this experiment) or in the single-dose (90 mg/kg) and multiple-dose (45 mg/kg daily for 5 days) peramivir-treated groups. Mean body weight losses on day 5 p.i. of 15.6% and 7.2% were seen in untreated animals and the low-dose oseltamivir group (Table 1 and Fig. 1A). In contrast, no weight loss was observed on day 5 in the two peramivir treatment groups. The mean viral titer determined in lung homogenates from untreated animals was 2.85 × 105 ± 0.1 × 105 PFU/ml. Reductions in the LVT of 3 log10 and 4 log10 were observed after low-dose oseltamivir treatment (1.3 × 102 ± 0.65 × 102 PFU/ml) (P < 0.001) and single-dose or multiple-dose peramivir regimens (4 × 101 ± 1 × 101 PFU/ml and 0.66 × 101 ± 0.11 × 101 PFU/ml), respectively (P < 0.001). Of note, comparison of the three NAI regimens revealed that the single-dose and multiple-dose peramivir regimens resulted in comparable weight loss and LVT values, which were significantly lower than those obtained in the oseltamivir group (P < 0.05).

Fig 1.

Impact of NAI regimens, starting at 24 h (A) or 48 h (B) after viral challenge, on body weight loss in mice infected with 6.9 × 103 PFU (A) or 8 × 103 PFU (B) of the recombinant A/WSN/33 (H1N1) WT virus. Regimens consisted of a single dose (90 mg/kg) or multiple doses (5 × 45 mg/kg, once daily [q.d.]) of IM peramivir (Per) and low-dose (1 mg/kg, q.d.) or high-dose (10 mg/kg, q.d.) oral oseltamivir (Osel). Each symbol represents the mean weight gain or loss of 12 mice ± standard deviation (SD).

Effect of 48-h delay of treatment on influenza A/WSN/33 (H1N1) WT virus.

For the 48 h p.i. protocol (Table 2), intranasal inoculation with 8 × 103 PFU of the recombinant WT virus resulted in a mortality rate of 100% in untreated animals, with an MDD of 4.87 days ± 0.35. No mortality was seen in any oseltamivir- or peramivir-treated group. Also, minimal (1.5% to 5.3%) body weight losses were recorded on day 5 p.i. in all treated animals compared to untreated and infected animals, whose mean weight loss reached 20.4% by day 5 p.i. (Table 2 and Fig. 1B). The mean LVT was 1.6 × 106 ± 0.6 × 106 PFU/ml in untreated animals. In contrast, animals that received either oseltamivir or peramivir regimens had a reduction in LVT of almost 5 log10, i.e., ranging from 2 to 8.6 × 101 PFU/ml (P < 0.001). Interregimen comparisons demonstrated no significant differences among the four NAI-treated groups in terms of mortality rate, weight loss, and LVT.

Effect of 24-h delay of treatment on influenza A/WSN/33 (H1N1) H275Y virus.

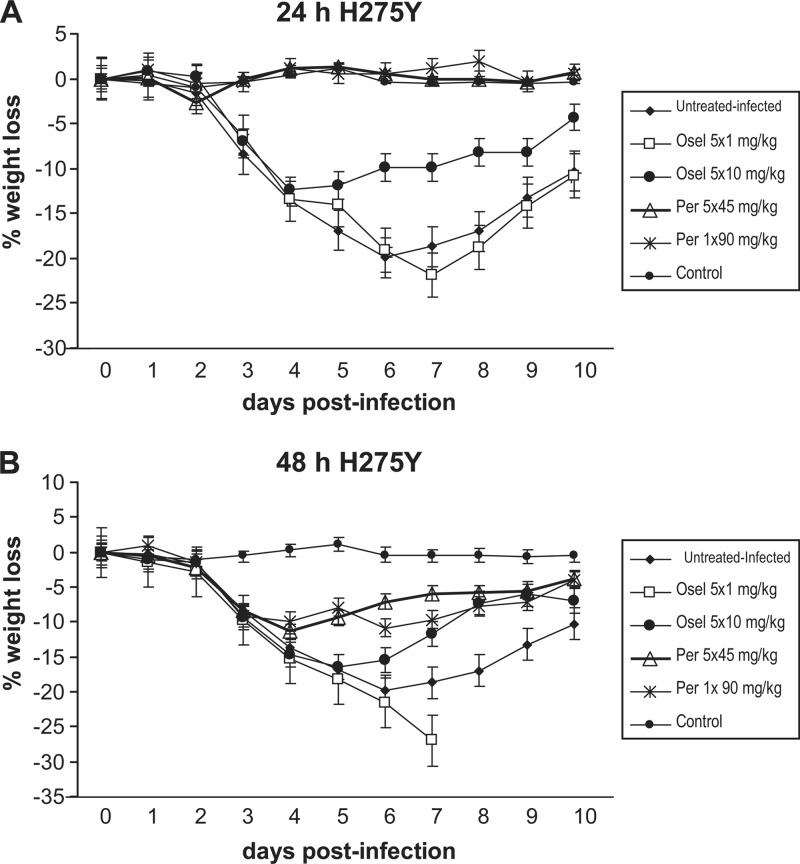

Intranasal inoculation of mice with 5.7 × 103 PFU of the recombinant H275Y NA mutant virus resulted in a mortality rate of 75% (6/8) in untreated and infected animals, with an MDD of 5.33 ± 0.51 days. For the 24 h p.i. treatment protocol (Table 3), the group that received the low-dose oseltamivir regimen had the same mortality rate as the group of untreated animals (75%), with an MDD of 6.16 ± 1.16 days. In contrast, there was no mortality in animals that received high-dose oseltamivir treatment or either of the two IM peramivir treatments. The infection resulted in significant body weight loss for the untreated group, with a mean weight loss of 16.9% on day 5 p.i. (Table 3 and Fig. 2A). Similarly, animals that received the low-dose and high-dose oseltamivir regimens had mean weight losses of 14% (P > 0.05) and 11.9% (P < 0.05), respectively. This contrasted with the groups that received single or multiple doses of peramivir, in which no weight loss was observed (P < 0.001). The mean viral titer determined in lung homogenates from untreated animals was 3.66 × 106 ± 0.11 × 106 PFU/ml. Comparable mean LVTs were found in animals that received the low-dose oseltamivir regimen, whereas there was a 1 log10 reduction (2.0 × 105 ± 0.44 × 105 PFU/ml) in mean LVT in mice treated with the high-dose oseltamivir regimen (P < 0.001). In contrast, mice that received the single and multiple peramivir treatments had a decrease in mean LVTs of at least 3 log10, i.e., 8 × 102 ± 5.29 × 102 PFU/ml and 2.2 103 ± 0.6 × 103 PFU/ml, respectively (P < 0.001). Interregimen comparisons showed that, despite a significant difference in their mortality rates (75% versus 0%; P < 0.001), the two oseltamivir regimens had comparable weight loss and LVT values. In contrast, the two peramivir regimens were comparable with regard to the mortality rate, weight loss, and LVT. The weight loss was significantly higher in animals that received 5 × 10 mg/kg of oseltamivir than in the animals in the single- and multiple-dose peramivir groups (P < 0.001), whereas no significant difference between the three groups was seen with regard to mortality and LVT.

Fig 2.

Impact of NAI regimens starting at 24 h (A) or 48 h (B) after viral challenge on body weight loss in mice infected with 5.7 × 103 PFU of the recombinant A/WSN/33 (H1N1) H275Y NA mutant. Regimens consisted of a single dose (90 mg/kg) or multiple doses (5 × 45 mg/kg, q.d.) of IM peramivir and low-dose (1 mg/kg, q.d.) or high-dose (10 mg/kg, q.d.) oral oseltamivir. Each symbol represents the mean weight gain or loss of 12 mice ± SD.

Effect of 48-h delay of treatment on influenza A/WSN/33 (H1N1) H275Y virus.

The results of the 48 h p.i. protocol in mice infected with 5.7 × 103 PFU of the H275Y mutant are shown in Table 4. Low-dose and high-dose oseltamivir regimens resulted in mortality rates of 100% and 62.5%, with an MDD of 5.75 ± 0.46 and 5.4 ± 0.54, respectively, compared to 75% mortality and an MDD of 5.33 ± 0.51 for the untreated and infected group. In sharp contrast, there was no mortality in groups that received single or multiple doses of IM peramivir. Mean body weight losses recorded on day 5 p.i. were 18.3% (P > 0.05) and 16.5% (P > 0.05) for the two oral oseltamivir groups compared to 16.9% for the untreated and infected group. On the other hand, there was a significant reduction in mean body weight loss for the two IM peramivir groups (7.9% [P < 0.001] and 9.4% [P < 0.01]) for the 1 × 90 mg/kg and 5 × 45 mg/kg groups, respectively) (Table 4 and Fig. 2B). Mean LVTs determined in groups that received low-dose or high-dose oseltamivir remained unchanged compared to the results for untreated animals (1.46 to 3.66 × 106 PFU/ml), whereas there was still a 2 log10 reduction observed in the single-IM-dose peramivir group (2.8 × 104 ± 0.7 × 104 PFU/ml) (P < 0.05) and a 3 log10 reduction observed in the multiple-dose peramivir group (3 × 103 ± 1.8 × 103 PFU/ml) (P < 0.001). Interregimen comparisons demonstrated a significant difference between the two oseltamivir regimens in terms of mortality rate (P < 0.05) despite their comparable weight loss and LVT values. In contrast, the two peramivir regimens were comparable with regard to the mortality rate, weight loss, and LVT. The effect of peramivir treatment was significantly greater than that seen with the 5 × 10 mg/kg oseltamivir group based on mortality rate (P < 0.001), weight loss (P < 0.05 for the 1 × 90 mg/kg group and P < 0.01 for the 5 × 45 mg/kg group), and LVT (P < 0.001).

DISCUSSION

As for other classes of antivirals, the increased use of NAIs may lead to the emergence and spread of drug-resistant influenza variants, compromising the long-term utility of these agents. Among available NAIs, oseltamivir has been preferred to zanamivir because of its convenient oral administration and the absence of bronchospasm, a possible secondary effect of inhaled zanamivir (27). The more frequent use of oseltamivir, combined with the greater complexity of its interactions with the catalytic site of the viral NA, may have contributed to increasing rates of resistance to this NAI, particularly among viruses of the A/H1N1 subtype (29). In that subtype, resistance is mainly mediated by the H275Y NA mutation, which also increases peramivir IC50 levels by a factor of 48- to 263-fold compared to 427- to 982-fold increases in oseltamivir IC50s (2, 31).

Parenteral peramivir, which has been approved for therapeutic use in Japan and South Korea, appears to be a valuable option for treatment of hospitalized persons with severe influenza virus infections, such as patients with gastric stasis or bleeding and those receiving extracorporeal membrane oxygenation who are unable to tolerate oral oseltamivir or inhaled zanamivir (5). Administration of intramuscular and IV peramivir demonstrated excellent pharmacokinetic properties which allowed a reliable single-dosing regimen (32). In healthy volunteers, a single intravenous injection of 600 mg of peramivir resulted in a peak plasma concentration of 34,100 ng/ml (32). Such a concentration is much higher than the in vitro IC50 exhibited by H275Y mutants. Furthermore, the IM administration of peramivir was associated with a similar pharmacokinetics profile (32). In mice, a single IM dose of 30 mg/kg resulted in a maximum plasma concentration of 17,675 ng/ml, which is 4,149 times the peramivir IC50 value (4.26 ng/ml) for the influenza H275Y NA mutant evaluated in this study. In addition to these interesting pharmacokinetics properties, peramivir demonstrated a particularly strong NA-inhibitory activity due to its conformation, which fits very well within the NA active site (6). Indeed, the negatively charged carboxylate group forms conserved hydrogen bonds with residues R118, R292, and R317 (N2 numbering) of the active site whereas the acetamido group binds to the hydrophobic pocket formed by I222 and W118 (6, 25). On the other hand, the positively charged guanidinium group forms strong hydrogen bonding and electrostatic interactions with E119, D151, and E277 (25). As a result, peramivir binds to the NA enzyme with much higher affinity than is observed with other NAIs. For instance, on-site dissociation studies showed that peramivir remained tightly bound to the NA enzyme, with a half-life for substrate conversion 19 times greater than that of zanamivir and oseltamivir (7). However, the H275Y NA mutation disturbs this affinity, resulting in a reduction of susceptibility that is 3-to-10-fold less with peramivir than with oseltamivir (19, 22).

In this study, we hypothesized that, due the excellent pharmacokinetic profile of parenteral peramivir in addition to its high NA inhibitory potency, IM peramivir would retain a protective efficacy against the oseltamivir-resistant H275Y variant even when administration was delayed up to 48 h after viral challenge, in line with our prophylactic study findings (4). Of note, we used again in this therapeutic study the peramivir dose regimens of 45 mg/kg and 90 mg/kg, which are respectively equivalent to the 300-mg and 600-mg doses currently evaluated in human clinical trials (32). On the other hand, the 10 mg/kg dose of oseltamivir is equivalent to the 75-mg oral dose used in humans (33).

Based on mortality rates, body weight losses, and LVTs, our experiments demonstrated that the single-dose (90 mg/kg) and multiple-dose (45 mg/kg daily for 5 days) IM peramivir regimens were protective against the WT as well as its H275Y variant in a lethal mouse model when initiated 24 h or 48 h after infection. Both peramivir regimens completely prevented mortality and weight loss when started 24 h after infection, whereas only mortality was prevented when treatment was initiated after 48 h. Nevertheless, weight losses observed in the two peramivir groups were significantly lower than those found in the untreated group. To a lesser extent, the high-dose oseltamivir regimen also prevented mortality and weight loss when initiated at 24 h p.i. but had no effect on mortality, weight loss, or LVTs when started after 48 h p.i. The higher level of resistance to oseltamivir conferred by the H275Y mutation and possibly lower concentrations of oseltamivir at the site of viral replication compared to those of IM peramivir could explain such differences. Against the WT virus, the high-dose (10 mg/kg) oseltamivir and both peramivir regimens showed similar protective effects in terms of mortality and reduction of LVTs in the 48-h treatment study, although peramivir was associated with less weight loss than oseltamivir.

It should be noted that the influenza strain used in this study was the mouse-adapted A/WSN/33 (H1N1) virus. Therefore, our findings regarding the activity of peramivir against the H275Y NA mutant remain to be confirmed using other viral backgrounds, including oseltamivir-resistant seasonal A/H1N1 viruses and A(H1N1)pdm09 strains, and by evaluating different animal models such as ferrets. Another interesting issue that remains to be addressed is whether IM peramivir could retain activity in virus variants with enhanced levels of resistance to peramivir due to additional NA mutations, such as those harboring the combination of H275Y and I223R/V mutations seen in A(H1N1)pdm09 variants (13, 14, 30). Finally, a limitation to our study was the daily use of oseltamivir instead of twice-daily administration as recommended in human therapeutic regimens. Thus, we cannot completely rule out an effect of twice-daily oseltamivir regimens on the replication of the H275Y mutant.

In conclusion, based on our lethal influenza A/WSN/33 (H1N1) virus mouse model, we suggest that IM or IV peramivir should be considered a possible therapeutic option for treatment of infections by oseltamivir-resistant influenza viruses harboring the H275Y mutation, especially when inhaled zanamivir is contraindicated or impractical. Because of a few instances of peramivir failure associated with the emergence of the H275Y mutation in immunocompromised patients (24), additional clinical studies are warranted before formal recommendation of the use of this NAI in the context of oseltamivir resistance.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported in part by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and BioCryst grants to G.B.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 4 June 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Abed Y, Boivin G. 2006. Treatment of respiratory virus infections. Antiviral Res. 70:1–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Abed Y, Goyette N, Boivin G. 2004. A reverse genetics study of resistance to neuraminidase inhibitors in an influenza A/H1N1 virus. Antivir. Ther. 9:577–581 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Abed Y, Nehme B, Baz M, Boivin G. 2008. Activity of the neuraminidase inhibitor A-315675 against oseltamivir-resistant influenza neuraminidases of N1 and N2 subtypes. Antiviral Res. 77:163–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Abed Y, Simon P, Boivin G. 2010. Prophylactic activity of intramuscular peramivir in mice infected with a recombinant influenza A/WSN/33 (H1N1) virus containing the H274Y neuraminidase mutation. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:2819–2822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Arya V, Carter WW, Robertson SM. 2010. The role of clinical pharmacology in supporting the emergency use authorization of an unapproved anti-influenza drug, peramivir. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 88:587–589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Babu YS, et al. 2000. BCX-1812 (RWJ-270201): discovery of a novel, highly potent, orally active, and selective influenza neuraminidase inhibitor through structure-based drug design. J. Med. Chem. 43:3482–3486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bantia S, Arnold CS, Parker CD, Upshaw R, Chand P. 2006. Anti-influenza virus activity of peramivir in mice with single intramuscular injection. Antiviral Res. 69:39–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Barroso L, Treanor J, Gubareva L, Hayden FG. 2005. Efficacy and tolerability of the oral neuraminidase inhibitor peramivir in experimental human influenza: randomized, controlled trials for prophylaxis and treatment. Antivir. Ther. 10:901–910 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Baz M, Abed Y, Boivin G. 2007. Characterization of drug-resistant recombinant influenza A/H1N1 viruses selected in vitro with peramivir and zanamivir. Antiviral Res. 74:159–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Birnkrant D, Cox E. 2009. The emergency use authorization of peramivir for treatment of 2009 H1N1 influenza. N. Engl. J. Med. 361:2204–2207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Boivin G, Goyette N. 2002. Susceptibility of recent Canadian influenza A and B virus isolates to different neuraminidase inhibitors. Antiviral Res. 54:143–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bright RA, Shay DK, Shu B, Cox NJ, Klimov AI. 2006. Adamantane resistance among influenza A viruses isolated early during the 2005–2006 influenza season in the United States. JAMA 295:891–894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. CDC 2009. Oseltamivir-resistant 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus infection in two summer campers receiving prophylaxis—North Carolina, 2009. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 58:969–972 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. CDC 2009. Update: drug susceptibility of swine-origin influenza A (H1N1) viruses, April 2009. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 58:433–435 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cheung CL, et al. 2006. Distribution of amantadine-resistant H5N1 avian influenza variants in Asia. J. Infect. Dis. 193:1626–1629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. de Jong MD, et al. 2005. Oseltamivir resistance during treatment of influenza A (H5N1) infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 353:2667–2672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fiore AE, et al. 2010. Prevention and control of influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2010. MMWR Recomm. Rep. 59(RR-8):1–62 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Govorkova EA, Leneva IA, Goloubeva OG, Bush K, Webster RG. 2001. Comparison of efficacies of RWJ-270201, zanamivir, and oseltamivir against H5N1, H9N2, and other avian influenza viruses. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:2723–2732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gubareva LV, Webster RG, Hayden FG. 2001. Comparison of the activities of zanamivir, oseltamivir, and RWJ-270201 against clinical isolates of influenza virus and neuraminidase inhibitor-resistant variants. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:3403–3408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Harper SA, et al. 2009. Seasonal influenza in adults and children—diagnosis, treatment, chemoprophylaxis, and institutional outbreak management: clinical practice guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 48:1003–1032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hurt AC, et al. 2009. Emergence and spread of oseltamivir-resistant A(H1N1) influenza viruses in Oceania, South East Asia and South Africa. Antiviral Res. 83:90–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hurt AC, Holien JK, Barr IG. 2009. In vitro generation of neuraminidase inhibitor resistance in A(H5N1) influenza viruses. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:4433–4440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Meijer A, et al. 2009. Oseltamivir-resistant influenza virus A (H1N1), Europe, 2007–08 season. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 15:552–560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Memoli MJ, Hrabal RJ, Hassantoufighi A, Eichelberger MC, Taubenberger JK. 2010. Rapid selection of oseltamivir- and peramivir-resistant pandemic H1N1 virus during therapy in 2 immunocompromised hosts. Clin. Infect. Dis. 50:1252–1255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mineno T, Miller MJ. 2003. Stereoselective total synthesis of racemic BCX-1812 (RWJ-270201) for the development of neuraminidase inhibitors as anti-influenza agents. J. Org. Chem. 68:6591–6596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mishin VP, Hayden FG, Signorelli KL, Gubareva LV. 2006. Evaluation of methyl inosine monophosphate (MIMP) and peramivir activities in a murine model of lethal influenza A virus infection. Antiviral Res. 71:64–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Moscona A. 2005. Neuraminidase inhibitors for influenza. N. Engl. J. Med. 353:1363–1373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Okomo-Adhiambo M, et al. 2010. Neuraminidase inhibitor susceptibility testing in human influenza viruses: a laboratory surveillance perspective. Viruses 2:2269–2289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pizzorno A, Abed Y, Boivin G. 2011. Influenza drug resistance. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 32:409–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pizzorno A, et al. 2012. Impact of mutations at residue i223 of the neuraminidase protein on the resistance profile, replication level, and virulence of the 2009 pandemic influenza virus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:1208–1214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pizzorno A, Bouhy X, Abed Y, Boivin G. 2011. Generation and characterization of recombinant pandemic influenza A(H1N1) viruses resistant to neuraminidase inhibitors. J. Infect. Dis. 203:25–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Shetty AK, Peek LA. 2012. Peramivir for the treatment of influenza. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 10:123–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ward P, Small I, Smith J, Suter P, Dutkowski R. 2005. Oseltamivir (Tamiflu) and its potential for use in the event of an influenza pandemic. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 55(Suppl. 1):i5–i21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wright PF, Webster RG. 2001. Orthomyxoviruses, p 1533–1562 In Knipe DM, et al. (ed), Fields virology, 4th ed Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA [Google Scholar]

- 35. Yun NE, et al. 2008. Injectable peramivir mitigates disease and promotes survival in ferrets and mice infected with the highly virulent influenza virus, A/Vietnam/1203/04 (H5N1). Virology 374:198–209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]