Abstract

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) surface antigen (HBsAg) decay was explored in HIV-1- and HBV-coinfected patients beginning antiretroviral (ARV) therapy containing tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF). The mean HBsAg decay was 0.38 log10 IU/ml/year (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.71 to 0.05) in 18 patients with sustained plasma HIV-1 RNA suppression and 0.15 log10 IU/ml/year (0.21 to 0.09) in 12 patients experiencing HIV-1 virologic failure due to suboptimal adherence to ARV (P = 0.17). We estimated that six of these 18 patients will attain HBsAg values below 10 IU/ml after 10 years of treatment.

TEXT

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) suppression maintained by treatment with lamivudine (3TC), emtricitabine (FTC), and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) reduces the progression of disease to liver failure and the development of hepatocellular carcinoma in HIV-1-infected patients. In some patients, therapy induces a complete loss of HBV surface antigen (HBsAg), indicating control of chronic HBV infection. HBsAg clearance was observed in 3% of HBV envelope antigen (HBeAg)-positive patients uninfected by HIV-1 after 1 year of treatment with 3TC (6), in 8% of HBeAg-positive patients after 3 years of treatment with TDF (5), and in 5% of HBeAg-negative patients after 5 years of treatment with adefovir (4). We conducted a longitudinal analysis of HBsAg concentration in HIV-1- and HBV-coinfected patients to explore the long-term evolution of HBsAg concentration after initiation of antiretroviral therapy (ART) containing TDF. The impact of imperfect adherence to ART on HBsAg decay was also explored.

Ethical approval for this study was given by the local ethics committee (Comité de Protection des Personnes Sud Méditerranée IV), under the reference Q2011.12.01. Thirty HIV-1/HBV-coinfected subjects monitored in the Montpellier University Teaching Hospital were tested for HBsAg concentration after providing written informed consent. Patients had chronic hepatitis B infection, defined as detectable serum HBsAg for more than 6 months. TDF was initiated as a part of an ARV therapy regimen containing 3TC or FTC and a nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (11 of 30) or protease inhibitors (19 of 30). A mean (standard deviation [SD]) of 8 (±4) samples were quantified for HBsAg concentration per individual during a mean (SD) follow-up under ART of 6.5 years (±3).

To address the potential impact of suboptimal adherence to ART on HBsAg clearance, we included in the group with suboptimal compliance with therapy 12 subjects that experienced HIV-1 RNA rebound exceeding 3 months during the follow-up and identified regular missed doses during interviews. Subjects who had detectable HIV-1 plasma RNA loads 9 months after initiation of ART were also included in this group. The other 18 individuals were categorized as being optimally treated. At the time of therapeutic initiation, the mean age was 40 years (±9); CD4 T cell count was 387/mm3 (±100); the median (interquartile range [IQR]) HIV-1 RNA level was 4.48 (3.69 to 5.21) log10 copies/ml, HBV DNA 5.62 (4.90 to 7.16) log10 IU/ml, 14/30 (47%) of the subjects were positive for HBeAg, 14/30 (47%) had elevated ALT (>40 U/liter), and one patient had hepatitis C virus coinfection. None of the individuals included had hepatitis delta virus (HDV) coinfection (ETI-AB-DELTAK-2 assay; DiaSorin, Turin, Italy), malignancies, or end-stage liver insufficiency. HBsAg concentrations were analyzed using the ETI-MAK-4 assay (DiaSorin, Turin, Italy) on a Triturus automated analyzer (Grifols, Barcelona, Spain) as previously described (11). Rates of HBsAg decay were estimated with the use of a longitudinal mixed-effects model (NLME package, R software, version 2.14; Free Software Foundation, Inc., Boston, MA). Comparisons of estimates between groups were made using a test of interaction (1). The evolution of CD4 T cell counts, HBV loads, and HIV-1 loads in optimally and suboptimally treated groups was computed using cubic spline regression adjusting for subject effect (rm [repeated measurements] boot function, Hmisc package). The P values presented are two-sided, and a P value of less than 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

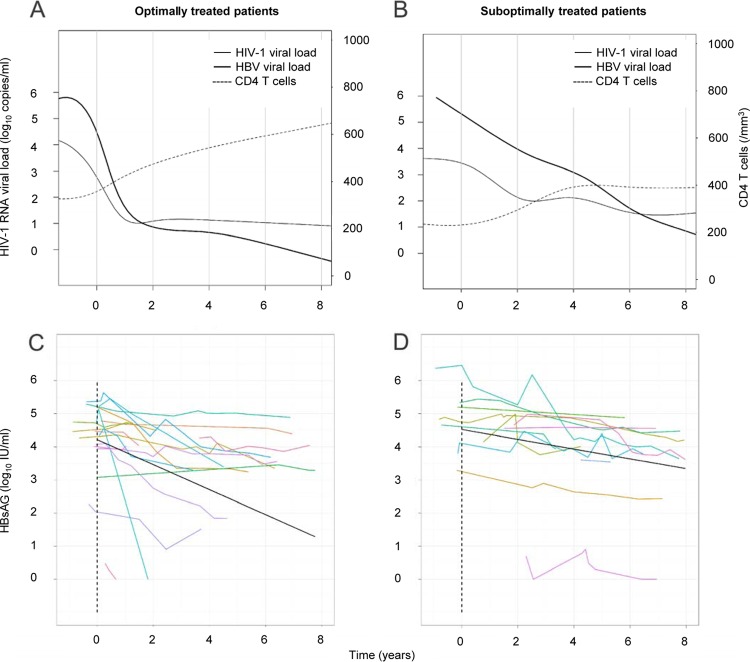

Pretreatment levels of HBsAg and HBV DNA were moderately correlated (r = 0.65, P = 0.007) (data not shown). HBV DNA and HIV-1 RNA declines and CD4 T cell recovery were faster in patients with sustained plasma HIV-1 RNA suppression than in subjects that experienced HIV-1 RNA rebound (Fig. 1A and B).

Fig 1.

Longitudinal analysis of serum HBsAg concentration in HIV-1/HBV-coinfected patients beginning a tenofovir-containing regimen. (A and B) Evolution of HIV-1 plasma RNA levels, HBV plasma DNA levels, and CD4 T cell counts in 18 patients with sustained plasma HIV-1 RNA suppression (A) and 12 patients experiencing HIV-1 virologic failure (B). (C and D) Evolution of HBsAg serum concentration in patients with sustained plasma HIV-1 RNA suppression (C) and patients experiencing HIV-1 virologic failure (D). Colored lines represent individual evolution of serum HBsAg concentrations over time. Black lines show the slope of decline, given by mixed-effect linear models in the two groups.

Overall, under ART the HBsAg concentration declined slowly in the both groups. We observed mean decays of 0.38 log10 IU/ml per year (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.71 to 0.05) in the optimally treated group and 0.15 log10 IU/ml per year (95% CI, 0.21 to 0.09) in the suboptimally treated group (P = 0.17). Visual inspection showed that the log-linear decay model fitted well with the data at the individual level (Fig. 1C and D). Important interindividual differences in the decrease of HBsAg were observed in the two groups, with the HBsAg log10 decay per year ranging from 2.68 to 0.03 in the optimally treated group versus 0.29 to 0.03 in the suboptimally treated group. We failed to observe a significant influence of CD4 T cells at baseline or CD4 T cell recovery on HBsAg decay (data not shown). In the optimally treated group, HBsAg clearance was seen in two patients with emergence of anti-HBs antibodies in one of them, and one patient reached an HBsAg concentration below 10 IU/ml after 2 years of ARV. HBsAg clearance and emergence of anti-HBs antibodies (>10 IU/ml) were observed in one patient in the group experiencing HIV-1 virologic failure. Based on our observations, we estimated that five patients from the optimally treated group but only one from the suboptimally treated group will attain a value below 10 IU/ml after 10 years of treatment. We calculated that four patients in the optimally treated group and one patient in the suboptimally treated group would never reach this value on therapy, since more than 50 years of the current anti-HBV treatment would be required to reach an HBsAg value below 10 IU/ml.

Our findings indicate that in HIV-1/HBV-coinfected individuals, HBsAg concentration decrease after therapeutic initiation of TDF/FTC- or 3TC-containing ARV regimens. Limitations of this study were the small number and heterogeneity of patients tested. Hence, we were not able to compare HBsAg decline in patients grouped according to HBeAg status, phase of persistent HBV infection, or HBV genotype. Previous studies have reported small variations in HBsAg concentration in non-HIV-1-infected subjects not treated with anti-HBV drugs (3, 9, 11). The reduction of HBsAg concentration may result from both a direct effect of the drugs on HBV polymerase and the immune reconstitution that follows initiation of ART (7). The rate of HBsAg decay we observed was higher than that in a recent study by Thibault and coworkers exploring HBsAg evolution in a group of coinfected patients with undetectable HIV-1 RNA and HBV DNA in a TDF-containing regimen (10) but comparable to the rates observed in HBV-monoinfected patients (5) and in a recently reported study by Maylin and coworkers investigating HIV-1/HBV-coinfected patients (7). The effect of adherence to treatment on the rate of HBsAg decline was less visible than that seen for HIV-1 RNA or HBV DNA decline or CD4 T cell recovery. While some HIV-1/HBV-coinfected patients with good adherence to ART did not undergo a significant decline in HBsAg level, others likely have a good chance to reach HBsAg concentrations below 10 IU/ml during lifelong treatment for HIV-1 infection. These patients may have a lower risk of HBV reactivation, since detection of HBsAg has been proposed as a marker of sustained HBV response after peginterferon-based regimens (2, 8). The necessity of maintaining inclusion of TDF in ART regimens in these patients should be further evaluated.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Johannes Viljoen for editorial assistance in the preparation of the manuscript.

This work was supported by a research grant from the Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (INSERM U1058).

E. Tuaillon, C. Lozano, N. Kuster, A. Poinso, D. Kania, N. Nagot, A. M. Mondain, G. P. Pageaux, J. Ducos, and P. Van De Perre declare no conflict of interest. J. Reynes has received funds from Abbott, Boehringer Ingelheim, BMS, Gilead, GSK, MSD, Pfizer, Tibotec, and ViiV Healthcare.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 3 July 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Altman DG, Bland JM. 2003. Interaction revisited: the difference between two estimates. BMJ 326:219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brunetto MR, et al. 2009. Hepatitis B virus surface antigen levels: a guide to sustained response to peginterferon alfa-2a in HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology 49:1141–1150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chan HL, et al. 2010. A longitudinal study on the natural history of serum hepatitis B surface antigen changes in chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology 52:1232–1241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hadziyannis SJ, et al. 2006. Long-term therapy with adefovir dipivoxil for HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B for up to 5 years. Gastroenterology 131:1741–1743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Heathcote EJ, et al. 2011. Three-year efficacy and safety of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate treatment for chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology 140:132–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Marcellin P, et al. 2004. Peginterferon alfa-2a alone, lamivudine alone, and the two in combination in patients with HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B. N. Engl. J. Med. 351:1206–1217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Maylin S, et al. 2012. Kinetics of hepatitis B surface and envelope antigen and prediction of treatment response to tenofovir in antiretroviral-experienced HIV-hepatitis B virus-infected patients. AIDS 26:939–949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Moucari R, et al. 2009. Early serum HBsAg drop: a strong predictor of sustained virological response to pegylated interferon alfa-2a in HBeAg-negative patients. Hepatology 49:1151–1157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Simonetti J, et al. 2010. Clearance of hepatitis B surface antigen and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in a cohort chronically infected with hepatitis B virus. Hepatology 51:1531–1537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Thibault V, et al. 2011. Six-year follow-up of hepatitis B surface antigen concentrations in tenofovir disoproxil fumarate treated HIV-HBV-coinfected patients. Antivir. Ther. 16:199–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tuaillon E, et al. 2012. Comparison of serum HBsAg quantitation by four immunoassays, and relationships of HBsAg level with HBV replication and HBV genotypes. PLoS One 7:e32143 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0032143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]