Abstract

Mosaic tetracycline resistance determinants are a recently discovered class of hybrids of ribosomal protection tet genes. They may show different patterns of mosaicism, but their final size has remained unaltered. Initially thought to be confined to a small group of anaerobic bacteria, mosaic tet genes were then found to be widespread. In the genus Streptococcus, a mosaic tet gene [tet(O/W/32/O)] was first discovered in Streptococcus suis, an emerging drug-resistant pig and human pathogen. In this study, we report the molecular characterization of a tet(O/W/32/O) gene-carrying mobile element from an S. suis isolate. tet(O/W/32/O) was detected, in tandem with tet(40), in a circular 14,741-bp genetic element (39.1% G+C; 17 open reading frames [ORFs] identified). The novel element, which we designated 15K, also carried the macrolide resistance determinant erm(B) and an aminoglycoside resistance four-gene cluster including aadE (streptomycin) and aphA (kanamycin). 15K appeared to be an unstable genetic element that, in the absence of recombinases, is capable of undergoing spontaneous excision under standard growth conditions. In the integrated form, 15K was found inside a 54,879-bp integrative and conjugative element (ICE) (50.5% G+C; 55 ORFs), which we designated ICESsu32457. An ∼1.3-kb segment that apparently served as the att site for excision of the unstable 15K element was identified. The novel ICE was transferable at high frequency to recipients from pathogenic Streptococcus species (S. suis, Streptococcus pyogenes, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Streptococcus agalactiae), suggesting that the multiresistance 15K element can successfully spread within streptococcal populations.

INTRODUCTION

Mosaic tetracycline resistance genes are a recently discovered class of hybrids of ribosomal protection tet genes (34). The mosaic tet genes found so far have shown different patterns of mosaicism, but the final size of the genes has remained unaltered. It is under debate whether they represent a previously undetected feature or a recent event in the evolution of tet genes. Mosaic derivatives of tet(O) and tet(W) were first detected in the Gram-negative anaerobe Megasphaera elsdenii from the swine intestine (31). In fact, a tet(O/32/O) mosaic gene, initially reported as tet(32), had previously been described in a Clostridium-related human isolate (22, 32). At first thought to be confined to a small group of anaerobic bacteria (28), mosaic tet genes were then found to be abundant in human and animal fecal samples (26). Other mosaic tet genes were later detected in organisms of genera Clostridium (19, 26), Bifidobacterium, and Lactobacillus (35).

In the genus Streptococcus, a mosaic tet gene [tet(O/W/32/O)] was first reported in Streptococcus suis-–an emerging drug-resistant pig and human pathogen (12, 21, 25, 36)—in a survey, where it was found to be second in frequency only to tet(O) among tet determinants (27). High rates of S. suis resistance to tetracyclines (up to >90%) have been reported in pig isolates worldwide (13, 27, 37, 41), probably reflecting the broad use of these antibiotics in piggeries. Tetracycline resistance in S. suis is mainly due to the ribosomal protection genes tet(O) and tet(M); tet(W) and the efflux genes tet(B), tet(L), and tet(40) have also been reported (25). Recent studies (20, 24) and the analyses of sequenced genomes (6, 15–18, 39, 40) have provided significant insights into the S. suis resistome, leading to the identification of several genetic elements carrying tet genes: primarily integrative and conjugative elements (ICEs), but also transposons, genomic islands, phages, and chimeric elements (25). A key role of ICEs in the dissemination of tet and other resistance genes has recently been reported, besides in S. suis, in major streptococcal pathogens such as S. pyogenes (3, 5, 11) and S. pneumoniae (7, 23).

The present study reports the molecular characterization of the tet(O/W/32/O) gene-carrying element from an S. suis pig isolate (27). The mosaic tet gene was detected, in tandem with tet(40), in a 14,741-bp unstable genetic element capable of undergoing spontaneous excision in the absence of recombinases. This element also carried macrolide [erm(B)] and aminoglycoside (aadE, aphA) resistance genes. In the integrated form, it was found inside an ICE (54,879 bp) that was transferable at high frequency to pathogenic Streptococcus species.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

S. suis 32457, the tet(O/W/32/O)-carrying strain used in this study, was isolated from the lung of a diseased pig in a recent survey of S. suis isolates in Italy (27). It was highly resistant to tetracycline (MIC, >256 μg/ml) and erythromycin [MIC, >256 μg/ml; erm(B) genotype].

Antimicrobials and susceptibility tests.

Tetracycline, erythromycin, streptomycin, and kanamycin were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO. MICs were determined by a standard broth microdilution method.

Amplification experiments.

The principal primers used in PCR experiments are listed in Table 1. DNA preparation and amplification and electrophoresis of PCR products were carried out by established procedures. The Ex Taq system (TaKaRa Bio, Shiga, Japan) was used when the expected PCR products exceeded 3 kb in size. The four att sequences were investigated by PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis using HindIII endonuclease (Roche Applied Science, Basel, Switzerland).

Table 1.

Principal oligonucleotide primers used in this study

| Gene | Primer |

Source or reference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Designation | Sequence (5′–3′) | ||

| tet(O/W/32/O) | tetWFa | GGAGGAAAATACCGACATA | 26 |

| tet(O/W/32/O) | tet32Ra | CTCTTTCATAGCCACGCC | 26 |

| erm(B) | ermBFb | TCATCTATTCAACTTATCGTC | This study |

| erm(B) | ermBRb | CTGTGGTATGGCGGGTAAG | This study |

| orf805-SC84c | PAI1 | CACGCATCTCGTAGAGTTTGAC | 6 |

| orf807-SC84c | intF | GATCTTGGAATCGATCCAGT | This study |

| orf807-SC84c | intR | TTCACCTGCTGGAGTTTTTG | This study |

| orf846-SC84c | primF | GTGGCAGGTGTTACTTTC | This study |

| orf846-SC84c | primR | GTCGTCTCTTGTATTGCCTG | This study |

| orf870-SC84c | SNF2F | TACTTCACTTTGAGACAGATG | This study |

| orf870-SC84c | SNF2R | TAGTTGAGTTACCGAGGC | This study |

| orf877-SC84c | virBF | GGTCGAATGGGTCTTTGTCT | This study |

| orf877-SC84c | virBR | GCTTGGTGTGTTGTGGGATC | This study |

| orf889-SC84c | repAF | GTGTCATCTCGTGGCTATTT | This study |

| orf889-SC84c | repAR | GCCCCATCCTCATCAATCC | This study |

| orf891-SC84c | rplLF | AAAGTTGGCGTTATCAAAG | This study |

| DNA primased | A | CGTGTCATCTTGTCTCCCTA | This study |

| 15K-leftd | B | AAAAAGCCCTACAATGCCGT | This study |

| 15K-rightd | C | ATAATGATTTTGCCATTGTC | This study |

| SNF2 helicased | D | GTCAAGAAATCACAAAAGGAG | This study |

Also used to obtain a probe specific for the tet(O/W/32/O) gene.

Also used to obtain a probe specific for the erm(B) gene.

Numbered according to the reported sequence of the genome of Streptococcus suis SC84 (accession no. FM252031).

Used in PCR-RFLP experiments to investigate att sequences.

DNA sequencing and sequence analysis.

PCR products were purified using Montage purification columns (Millipore Corporation, Bedford, MA). Sequencing was carried out using ABI Prism (Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) with dye-labeled terminators. Sequences were analyzed using the Sequence Navigator software package (Perkin-Elmer). Open reading frames (ORFs) were predicted using the ORF Finder software (http://ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gorf/gorf.html). Criteria to design a potential ORF were the existence of a start codon and a minimum coding size of 50 amino acids. Sequence similarity searches were carried out using BLAST (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov).

Conjugal transfer experiments.

Four rifampin- and fusidic acid-resistant (RF) derivatives of tetracycline- and erythromycin-susceptible strains of different species were used as recipients in mating experiments with S. suis 32457 as the donor: S. suis v36RF (27), Streptococcus pyogenes 12RF (9), Streptococcus pneumoniae R6RF, and Streptococcus agalactiae 1357RF. Transfer experiments were performed with a membrane filter (9), and selection was performed with suitable antibiotic concentrations. To rule out the contribution of transformation to the genetic exchange during conjugation, matings were carried out in the presence of 10 mg/ml DNase I (Sigma) (30). The frequency of transfer was expressed as the number of transconjugants per recipient. Transfer experiments were done a minimum of three times.

PFGE and hybridization experiments.

Macrorestriction with SfiI endonuclease (Roche) and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) analysis were performed as described elsewhere (27). SfiI was used instead of SmaI because a SmaI restriction site was found in the genetic element investigated. Southern blotting and hybridization assays were done as described previously (10) using probes obtained by PCR with the oligonucleotide primers reported in Table 1.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of ICESsu32457 has been submitted to the GenBank/EMBL sequence database and assigned accession number FR823304.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The tet(O/W/32/O)-carrying element from strain 32457 was investigated by combining conjugation experiments, PFGE, hybridization assays, PCR, restriction analysis, and sequence analysis.

Evidence of a 50- to 60-kb mobile element carrying tet(O/W/32/O) and erm(B).

In mating experiments, tetracycline resistance was successfully transferred at high frequency from S. suis 32457 to the recipients of all four species (S. suis, S. pyogenes, S. pneumoniae, and S. agalactiae) (Table 2). All transconjugants carried not only tet(O/W/32/O) but also erm(B), suggesting a linkage between the two resistance genes in a mobile element. The transconjugants exhibited the same tetracycline and erythromycin MICs as the donor.

Table 2.

Conjugal transfer of resistance genes tet(O/W/32/O) and erm(B) from the S. suis 32457 donor to four susceptible Streptococcus recipients

| Recipients |

Transfer frequencyb | Transconjugants |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strain | MIC (μg/ml)a |

PFGE and hybridization |

MIC (μg/ml)a |

|||||

| TET | ERY | Insertion size (kb) | tet(O/W/32/O) | erm(B) | TET | ERY | ||

| S. suis v36RF | 0.06 | 0.06 | 3.1 × 10−4 | 50–60 | + | + | >256 | >256 |

| S. pyogenes 12RF | <0.015 | <0.015 | 7.5 × 10−5 | 50–60 | + | + | >256 | >256 |

| S. pneumoniae R6RF | 0.5 | 0.03 | 4.3 × 10−5 | 50–60 | + | + | >256 | >256 |

| S. agalactiae 1357RF | 0.25 | 0.5 | 2.0 × 10−5 | 50–60 | + | + | >256 | >256 |

TET, tetracycline; ERY, erythromycin.

Data are from assays using tetracycline (10 μg/ml) for resistance selection, but closely comparable results were obtained using erythromycin (10 μg/ml).

Five randomly chosen transconjugants from each mating assay were used in experiments aimed at confirming and characterizing the transferred element. Results of SfiI PFGE analysis and hybridization assays, performed with the recipients and the transconjugants, were consistent with the existence of a 50- to 60-kb mobile element carrying tet(O/W/32/O) and erm(B) in the genome of the transconjugants.

PCR detection of a circular 14,741-bp tet(O/W/32/O)- and erm(B)-carrying element.

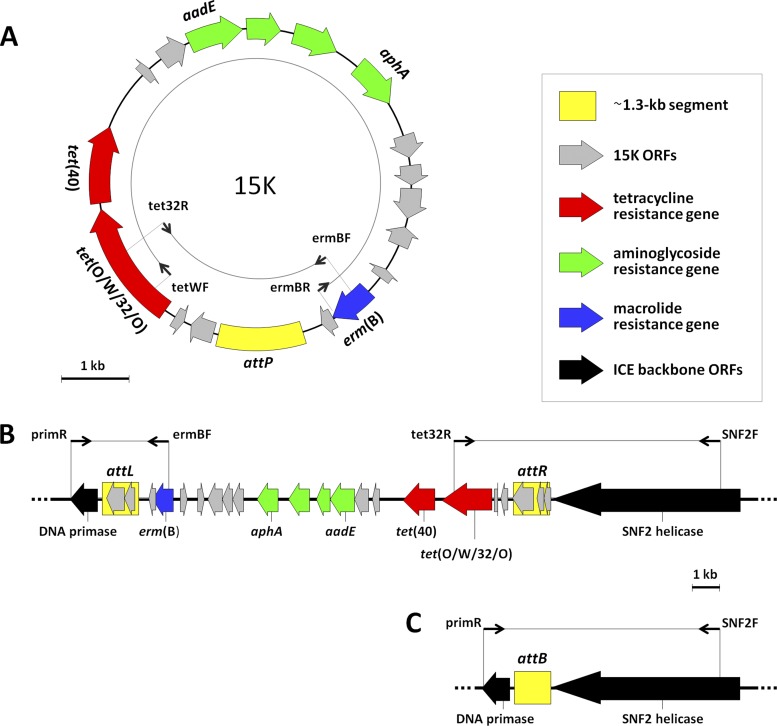

The putative genetic linkage between tet(O/W/32/O) and erm(B) was explored in PCR experiments by testing all four combinations of forward/reverse primers internal to the two genes. Interestingly, two combinations yielded a different PCR product each (11,543 bp and 4,305 bp) (Fig. 1A). Sequencing of the two amplicons, together with further PCR experiments with primers external to tet(O/W/32/O) and erm(B), clearly demonstrated a circular element (14,741 bp; 39.1% G+C; containing an SmaI restriction site). Seventeen ORFs, of which 14 were transcribed in the same direction as the resistance genes and 3 in the opposite direction, were identified in this element, which we designated 15K. Additional antibiotic resistance genes—namely, tet(40) and an aminoglycoside resistance gene cluster—were found in the larger portion lying between tet(O/W/32/O) and erm(B). tet(40), here located immediately downstream of tet(O/W/32/O), is a novel efflux gene so far consistently detected in tandem with ribosomal protection tet genes, such as tet(O/32/O) in Clostridium saccharolyticum (19) and tet(O) in S. suis (16, 25). The tandem presence of a ribosomal protection tet gene and an efflux tet gene is consistent with the high-level tetracycline resistance displayed by S. suis 32457 and the transconjugants. The aminoglycoside resistance gene cluster was formed by four ORFs, three—including the streptomycin resistance determinant aadE-–>99% identical to a trio found in Enterococcus faecalis plasmid pEF418 (accession no. AF408195), plus the kanamycin resistance determinant aphA. In agreement with the presence of these genes, the transconjugants exhibited 8- to 16-fold-higher streptomycin and kanamycin MICs than the recipients. All the other ORFs of 15K coded for hypothetical proteins with unknown function.

Fig 1.

15K from S. suis 32457: an unstable multiresistance genetic element exploiting a conserved ∼1.3-kb ICE segment as the att site for its excision. (A) Genetic organization of the 15K element in the circular form. (B) Genetic organization of the 15K element in the integrated form. (C) DNA repair after 15K excision. Major primer pairs used and relevant amplicons are shown. ORFs are indicated as arrows pointing in the direction of transcription. No ORFs are associated with attP or attB due to the genetic heterogeneity of the relevant sequences. Color coding is defined in the inset.

Insights into an ∼1.3-kb segment playing a key role in 15K excision.

Analysis of the smaller portion of 15K lying between tet(O/W/32/O) and erm(B) disclosed an ∼1.3-kb segment of special interest. The segment showed >90% identity with corresponding regions of several streptococcal ICEs, including a few recently detected in S. suis (6, 15, 40). In some of these S. suis ICEs, the segment is flanked on one or the other side by cargo DNA, whereas in others it is split by the insertion of cargo DNA into two fragments (∼700 bp and ∼550 bp); in all cases, the region formed by the ∼1.3-kb segment plus the cargo DNA is surrounded by two highly conserved backbone ORFs, a putative DNA primase on the left side and a putative SNF2 helicase on the right side. Remarkably, both conserved ORFs, which were not detected by PCR in the four recipients, were detected in the genome of S. suis 32457 and of all transconjugants. These findings suggested to us that 15K could be integrated as a cargo in an ICE (i.e., the 50- to 60-kb mobile element detected by PFGE and hybridization assays). By combining primers internal to 15K with primers internal to the DNA primase and the SNF2 helicase coding sequences, 15K was found to be integrated as a linear element between the two ORFs (Fig. 1B). Sequencing revealed that when 15K was in the integrated form, there were two copies (displaying 95% identity) of the ∼1.3-kb segment, one on the left side and one on the right side. Two ORFs were associated with the former and three with the latter, all coding for hypothetical proteins with unknown function. Interestingly, PCR experiments demonstrated that in addition to being integrated as a linear element, 15K could also be missing altogether (both in S. suis 32457 and in the transconjugants), consistent with its excision in circular form: after DNA repair, only one copy of the ∼1.3-kb segment was found between the two backbone ORFs (Fig. 1C).

Despite their unusual length, the four copies of the ∼1.3-kb segment actually represent att sequences involved in 15K excision and, possibly, integration: attL and attR, the two copies flanking the integrated 15K; attP, the copy found in the circular 15K; and attB, the copy found between the two conserved backbone ORFs after 15K excision.

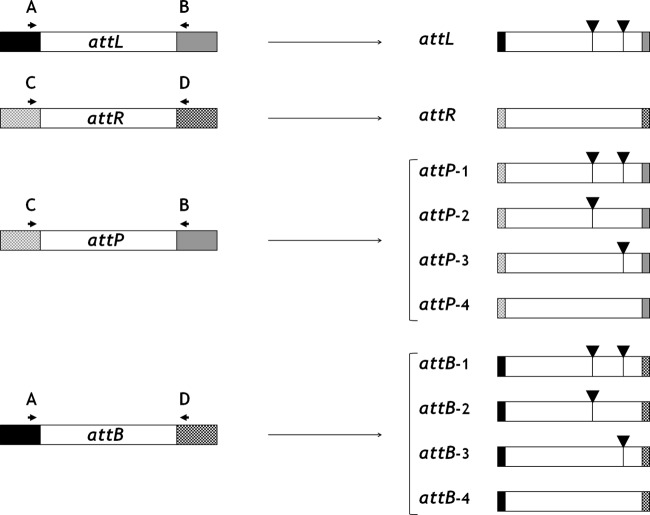

In recent studies of unstable genetic elements resembling 15K (i.e., capable of spontaneous excision in the absence of their own recombinase genes by exploiting long att sequences) (1, 29), the excision mechanism appeared to be associated with recombination events between attL and attR, yielding multiple attP and attB hybrid sequences in the bacterial population. The possibility that 15K could share this feature was suggested by the occurrence of several dual peaks in the electropherograms of the attB- and attP-containing amplicons just where mismatches between attL and attR were detected. PCR-RFLP analysis using HindIII endonuclease (which has two restriction sites in attL and none in attR) confirmed that, while attL and attR were fixed sequences, attB and attP were heterogeneous hybrids of the attL and attR sequences, some containing both HindIII restriction sites detected in attL, some just one, and some none (Fig. 2).

Fig 2.

Schematic illustration of PCR-RFLP assays using HindIII endonuclease, indicating that attB and attP sequences are heterogeneous hybrids of the fixed attL and attR sequences. The att sequences are shown as white bars, flanked by DNA of ICE backbone ORFs (plain black, DNA primase; checkered black, SNF2 helicase) or of 15K (plain gray, left end; checkered gray, right end). Primers (A, B, C, and D) are depicted as arrowheads. HindIII restriction sites are depicted as vertical strokes with overhanging black triangles.

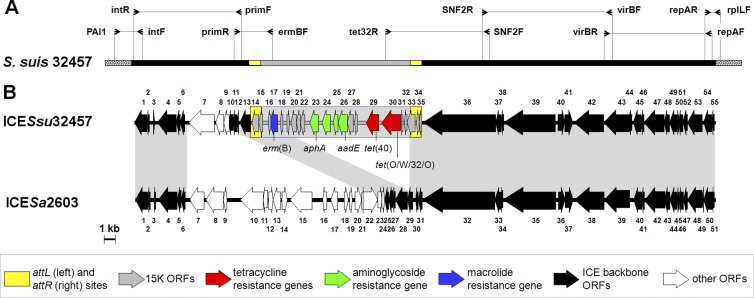

Characterization of a 54,879-bp ICE carrying 15K.

PCR mapping using primers internal to conserved regions of streptococcal ICEs demonstrated a 15K-carrying composite ICE in S. suis 32457 and the transconjugants (Fig. 3A). The ICE, which we named ICESsu32457, was completely sequenced (54,879 bp; 50.5% G+C), and its chromosomal junctions were determined. Sequence analysis revealed 55 ORFs, of which 50 were transcribed in the same direction and 5 in the opposite direction (Fig. 3B). The fragment formed by 15K plus the attL and attR sequences (22 ORFs) was integrated between orf13 (DNA primase) and orf36 (SNF2 helicase) of ICESsu32457. The highest BLASTN score for the ICE backbone was S. agalactiae ICESa2603 (33) (>94% identity). BLASTP analysis of the integrase (orf1) disclosed >99% amino acid identity with the tyrosine family recombinase of S. agalactiae ICESa2603. The latter, which has extensively been compared with ICEs from other streptococcal species (7, 8), is regarded as the prototype of an ICE family recognized in a recent ICE classification (ICEberg database http://db-mml.sjtu.edu.cn/ICEberg) based on the amino acid identity of integrases (4). In S. suis 32457 and all tested transconjugants, the integrase mediated ICE integration immediately downstream of the 50S ribosomal protein L7/L12 gene (rplL). In both S. suis 32457 and the transconjugants, ICESsu32457 was also detected by PCR in the circular form, as is required for ICE transfer (38).

Fig 3.

Genetic organization of 15K-carrying ICESsu32457 from S. suis 32457. (A) PCR mapping of ICESsu32457. Major primer pairs used and relevant amplicons are shown. The DNA is represented by a bar (black, ICE; gray, 15K; yellow, att sites; spotted, chromosome). (B) ORF map and genetic organization of ICESsu32457 and its alignment with the ORF map of ICESa2603. The ORFs, indicated as arrows pointing in the direction of transcription, are numbered consecutively in the two ICEs. Color coding is defined in the inset.

Concluding remarks.

tet(O/W/32/O), detected by our group in S. suis pig isolates, was the first mosaic tet gene reported in the genus Streptococcus (27). It has subsequently been detected in a human endocarditis isolate of Streptococcus gallolyticus subsp. gallolyticus, a taxon resulting from the recent reclassification of Streptococcus bovis (2), where it was carried by an ∼21-kb non-self-transmissible plasmid (14). This is the first study to characterize a mosaic tet gene-carrying conjugative element. ICESsu32457, which is transferable to the major pathogenic Streptococcus species, may be an important genetic vehicle for the spread of tet(O/W/32/O); however, it is not the sole, and probably not even the most common, genetic support for the gene. In the recent survey of S. suis isolates in Italy leading to collection of S. suis 32457, seven additional clonally unrelated pig isolates were found to harbor the tet(O/W/32/O) gene (27). However, in these seven isolates the gene, still linked to erm(B), was carried by a variety of non-self-transmissible plasmids (∼15 to ∼25 kb in size), a genetic organization that was reminiscent of the one mentioned above for S. gallolyticus subsp. gallolyticus (14). However, the genetic contexts of tet(O/W/32/O) in 15K and the above plasmids showed no similarities (data not shown).

An especially interesting finding of this study is the novel genetic element (15K) integrated as a cargo in ICESsu32457. On the one hand, 15K bears a unique combination of tetracycline, macrolide, and aminoglycoside resistance genes. On the other, it appears to be an unstable genetic element that, though lacking an integrase/excisionase system, undergoes spontaneous excision in circular form under standard growth conditions. 15K may represent a novel class of mobile genetic structures capable of excision in spite of the lack of their own recombinase genes. As indicated in recent reports on enterobacteria (1, 29), excision apparently occurs through recombination between unusually long, imperfect direct repeats flanking the element. It has been suggested that such elements may employ a parasitic strategy for their mobility (1), exploiting host recombination trans-acting functions (1, 29). It may be hypothesized that, as demonstrated for an Escherichia coli microcin-encoding genomic island (1), 15K can also spread to other streptococcal ICEs by integrating into the conserved empty attB. The fact that 15K is carried by ICESsu32457, a composite ICE capable of moving at high frequency to a broad spectrum of streptococcal hosts, suggests that this unstable multiresistance element can successfully spread among streptococcal populations.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported in part by the Italian Ministry of Education, University and Research (PRIN 2008CBSB9Y and 200929YFMK).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 18 June 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Azpiroz MF, Bascuas T, Laviña M. 2011. Microcin H47 system: an Escherichia coli small genomic island with novel features. PLoS One 6:e26179 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0026179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Beck M, Frodl R, Funke G. 2008. Comprehensive study of strains previously designated Streptococcus bovis consecutively isolated from human blood cultures and emended description of Streptococcus gallolyticus and Streptococcus infantarius subsp. coli. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46:2966–2972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Beres SB, Musser JM. 2007. Contribution of exogenous genetic elements to the Group A Streptococcus metagenome. PLoS One 2:e800 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0000800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bi D, et al. 2012. ICEberg: a web-based resource for integrative and conjugative elements found in Bacteria. Nucleic Acids Res. 40:D621–D626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brenciani A, et al. 2011. Two distinct genetic elements are responsible for erm(TR)-mediated erythromycin resistance in tetracycline-susceptible and tetracycline-resistant strains of Streptococcus pyogenes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:2106–2112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chen C, et al. 2007. A glimpse of streptococcal toxic shock syndrome from comparative genomics of S. suis 2 Chinese isolates. PLoS One 2:e315 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0000315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Croucher NJ, et al. 2009. Role of conjugative elements in the evolution of the multidrug-resistant pandemic clone Streptococcus pneumoniae Spain23F ST81. J. Bacteriol. 191:1480–1489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Davies MR, Shera J, Van Domselaar GH, Sriprakash KS, McMillan DJ. 2009. A novel integrative conjugative element mediates genetic transfer from group G streptococcus to other β-hemolytic streptococci. J. Bacteriol. 191:2257–2265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Giovanetti E, et al. 2002. Conjugative transfer of the erm(A) gene from erythromycin-resistant Streptococcus pyogenes to macrolide-susceptible S. pyogenes, Enterococcus faecalis, and Listeria innocua. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 50:249–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Giovanetti E, Brenciani A, Lupidi R, Roberts MC, Varaldo PE. 2003. Presence of the tet(O) gene in erythromycin- and tetracycline-resistant strains of Streptococcus pyogenes and linkage with either the mef(A) or the erm(A) gene. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:1935–1940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Giovanetti E, Brenciani A, Tiberi E, Bacciaglia A, Varaldo PE. 2012. ICESp2905, the erm(TR)-tet(O) element of Streptococcus pyogenes, is formed by two independent integrative and conjugative elements. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:591–594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gottschalk M, Xu J, Calzas C, Segura M. 2010. Streptococcus suis: a new emerging or an old neglected zoonotic pathogen? Future Microbiol. 5:371–391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hendriksen RS, et al. 2008. Occurrence of antimicrobial resistance among bacterial pathogens and indicator bacteria in pigs in different European countries from year 2002-2004: the ARBAO-II study. Acta Vet. Scand. 50:19 doi:10.1186/1751-0147-50-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hinse D, et al. 2011. Complete genome and comparative analysis of Streptococcus gallolyticus subsp. gallolyticus, an emerging pathogen of infective endocarditis. BMC Genomics 12:400 doi:10.1186/1471-2164-12-400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Holden MT, et al. 2009. Rapid evolution of virulence and drug resistance in the emerging zoonotic pathogen Streptococcus suis. PLoS One 4:e6072 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0006072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hu P, et al. 2011. Complete genome sequence of Streptococcus suis serotype 14 strain JS14. J. Bacteriol. 193:2375–2376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hu P, et al. 2011. Complete genome sequence of Streptococcus suis serotype 3 strain ST3. J. Bacteriol. 193:3428–3429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hu P, et al. 2011. Comparative genomics study of multi-drug-resistance mechanisms in the antibiotic-resistant Streptococcus suis R61 strain. PLoS One 6:e24988 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0024988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kazimierczak KA, et al. 2008. A new tetracycline efflux gene, tet(40), is located in tandem with tet(O/32/O) in a human gut firmicute bacterium and in metagenomic library clones. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:4001–4009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Li M, et al. 2011. GI-type T4SS-mediated horizontal transfer of the 89K pathogenicity island in epidemic Streptococcus suis serotype 2. Mol. Microbiol. 79:1670–1683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lun ZR, Wang QP, Chen XG, Li AX, Zhu XQ. 2007. Streptococcus suis: an emerging zoonotic pathogen. Lancet Infect. Dis. 7:201–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Melville CM, Scott KP, Mercer DK, Flint HJ. 2001. Novel tetracycline resistance gene, tet(32), in the Clostridium-related human colonic anaerobe K10 and its transmission in vitro to the rumen anaerobe Butyrivibrio fibrisolvens. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:3246–3249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mingoia M, Tili E, Manso E, Varaldo PE, Montanari MP. 2011. Heterogeneity of Tn5253-like composite elements in clinical Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:1453–1459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Palmieri C, Princivalli MS, Brenciani A, Varaldo PE, Facinelli B. 2011. Different genetic elements carrying the tet(W) gene in two human clinical isolates of Streptococcus suis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:631–636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Palmieri C, Varaldo PE, Facinelli B. 2011. Streptococcus suis, an emerging drug-resistant animal and human pathogen. Front. Microbiol. 2:235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Patterson AJ, Rincon MT, Flint HJ, Scott KP. 2007. Mosaic tetracycline resistance genes are widespread in human and animal fecal samples. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:1115–1118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Princivalli MS, et al. 2009. Genetic diversity of Streptococcus suis clinical isolates from pigs and humans in Italy (2003-2007). Euro Surveill. 14:15–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Roberts MC. 2005. Update on acquired tetracycline resistance genes. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 245:195–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Santiviago CA, et al. 2010. Spontaneous excision of the Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis-specific defective prophage-like element φSE14. J. Bacteriol. 192:2246–2254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Santoro F, Oggioni MR, Pozzi G, Iannelli F. 2010. Nucleotide sequence and functional analysis of the tet(M)-carrying conjugative transposon Tn5251 of Streptococcus pneumoniae. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 308:150–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Stanton TB, Humphrey SB. 2003. Isolation of tetracycline-resistant Megasphaera elsdenii strains with novel mosaic gene combinations of tet(O) and tet(W) from swine. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:3874–3882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Stanton TB, Humphrey SB, Scott KP, Flint HJ. 2005. Hybrid tet genes and tet gene nomenclature: request for opinion. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:1265–1266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tettelin H, et al. 2002. Complete genome sequence and comparative genomic analysis of an emerging human pathogen, serotype V Streptococcus agalactiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:12391–12396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Thaker M, Spanogiannopoulos P, Wright GD. 2010. The tetracycline resistome. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 67:419–431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. van Hoek AH, et al. 2008. Mosaic tetracycline resistance genes and their flanking regions in Bifidobacterium thermophilum and Lactobacillus johnsonii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:248–252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wertheim HFL, Nghia HDT, Taylor W, Schultsz C. 2009. Streptococcus suis: an emerging human pathogen. Clin. Infect. Dis. 48:617–625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wisselink HJ, Veldman KT, Van den Eede C, Salmon SA, Mevius DJ. 2006. Quantitative susceptibility of Streptococcus suis strains isolated from diseased pigs in seven European countries to antimicrobial agents licensed in veterinary medicine. Vet. Microbiol. 113:73–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wozniak RA, Waldor MK. 2010. Integrative and conjugative elements: mosaic mobile genetic elements enabling dynamic lateral gene flow. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8:552–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ye C, et al. 2009. Clinical, experimental, and genomic differences between intermediately pathogenic, highly pathogenic, and epidemic Streptococcus suis. J. Infect. Dis. 199:97–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Zhang A, et al. 2011. Comparative genomic analysis of Streptococcus suis reveals significant genomic diversity among different serotypes. BMC Genomics 12:523 doi:10.1186/1471-2164-12-523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zhang C, et al. 2008. In vitro antimicrobial susceptibility of Streptococcus suis strains isolated from clinically healthy sows in China. Vet. Microbiol. 131:386–392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]