Abstract

On the cellular level, oxidative stress may cause various responses, including autophagy and cell death. All of these outcomes involve disturbed Ca2+ signaling. Here we show that the nuclear enzymes poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP1) and PARP2 control cytosolic Ca2+ shifts from extracellular and intracellular sources associated with autophagy or cell death. The different Ca2+ signals arise from the transient receptor potential melastatin 2 (TRPM2) channels located in the cellular and lysosomal membranes. They induce specific stress kinase responses of canonical autophagy and cell death pathways. Autophagy is under the control of PARP1, which operates as an autophagy suppressor after oxidative stress. Cell death is activated downstream of extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2) and AKT, whereas cell survival correlates with the phosphorylation of p38, stress-activated protein kinase/Jun amino-terminal kinase (SAPK/JNK), and cyclic AMP response element-binding protein (CREB) with its activating transcription factor (ATF-1). Our results highlight an important role for PARP1 and PARP2 in the epigenetic control of cell death and autophagy pathways.

INTRODUCTION

On the cellular level, oxidative stress may induce pleiotropic responses ranging from autophagy to death. Little is known about the molecular switches between death and autophagy (10). Here we investigated the role of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP1) and PARP2, two nuclear enzymes, in regulating the outcome of oxidative stress. Oxidative stress induces DNA damage, activating PARP1 and PARP2. Activated PARP signals downstream into DNA repair processes and cell death pathways. It is therefore a key factor in the maintenance of genomic stability (11). PARP1 is the main enzyme, producing about 90% of poly(ADP-ribose) (PAR) (11, 12, 27). PARP2 shares many of the properties of PARP1 but contributes far less to PAR synthesis (38). PAR is immediately degraded by poly(ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase (PARG) to free PAR and finally to monomeric ADP-ribose (ADPR) (12). It has been shown in vitro and in a variety of different cell types that intracellular ADPR activates transient receptor potential melastatin 2 (TRPM2) channels (21, 24, 35). This Ca2+ channel operates in plasma membranes and lysosomes (16, 23, 30). It is well established that an insult-dependent cellular Ca2+ overload results in cytotoxic stress responses ranging from survival to autophagy to cell death (39).

This study focused on the types and sources of cytosolic Ca2+ shifts after low and high levels of oxidative stress in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs). Using gene knockout, RNA interference (RNAi), and chemical inhibitors, we determined the impact of PARP1 and PARP2 on distinct Ca2+ shifts and downstream consequences for cell death and autophagy. Our results show that PARP1 regulates Ca2+ shifts by plasma membrane TRPM2 and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) at low levels of oxidative stress. The presence or absence of PARP1-mediated cytosolic Ca2+ is further translated into a different stress kinase pattern leading to cell death or survival responses. Therefore, H2O2-provoked PARP1 activity is indicative of cell fate decisions.

In contrast, PARP2 induces Ca2+ shifts from other TRPM2 localizations, most likely lysosomes, under high-dose stress conditions, even when PARP1 is completely inactive. Downstream of Ca2+ signaling, PARP1 operates as a suppressor of the autophagy pathway.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

Immortalized MEFs from the Parp1+/+ (wild type [WT]) and Parp1−/− backgrounds were used. MEFs were cultured at 37°C in a water-saturated (5% CO2) atmosphere in complete Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Gibco) containing 1 g/liter glucose and supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum and penicillin-streptomycin (Invitrogen).

RNAi.

All transfection experiments were performed with siPORT Amine (Ambion) as the transfection reagent under conditions described earlier. Small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) against Becn1 (siRNA-B1; 5′-AAAGCUACCAUUGCAUGGUCA-3′ [antisense sequence]), Parp1 (siRNA-P1; 5′-AAGAGCGATGCCTATTACTGC-3′ [antisense]) (7), Parp2 (siRNA-P2; 5′-AAGATGATGCCAGAGGAACTC-3′ [antisense]) (7), and Trpm2 (siRNA-T2; 5′-UACUCGACCACGUAGACUCCA-3′ [antisense]) (3) were obtained from Applied Biosystems. For maximal silencing efficacy, we performed silencing of Becn1 for 24 h and that of all others for 72 h.

H2O2 treatment.

Cells were challenged with 1 part H2O2 (Sigma) diluted in OPTI-MEM I (Gibco) to the desired concentration. After 1 h, 3 parts complete DMEM was added. This treatment was maintained without any alterations until the end of the experiment.

Chemicals.

3-Aminobenzamide (3-AB) was from Alexis Biochemicals. 3-Methyladenine (3-MA), bafilomycin A1 (Baf A1), H2O2, N-{N-[(phenylmethoxy)carbonyl]-l-valyl}-phenylalaninal (MDL 28170), and 2-(4-amino-1-isopropyl-1H-pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidin-3-yl)-1H-indol-5-ol (PP242) were from Sigma. N-(p-Amylcinnamoyl)-anthranilic acid (ACA) and N-(2-quinolyl)valyl-aspartyl-(2,6-difluorophenoxy)methyl ketone (Q-VD-OPh) were from Calbiochem. Hoechst 33342 was from Invitrogen. 2-(4-Morpholinyl)-8-phenyl-4H-1-benzopyran-4-one hydrochloride (LY294002) was from Biaffin GmbH & Co. KG. 4-(4-Fluorophenyl)-2-(4-methylsulfinylphenyl)-5-(4-pyridyl)1H-imidazole (SB203580) was from Cell Signaling. 1-{6-[(17-β-3-Methoxyestra-1,3,5(10)-trien-17-yl)amino]hexyl}-1H-pyrrole-2,5-dione (U-73122), methylthiohydantoin-dl-tryptophan (necrostatin 1), 2′-amino-3′-methoxyflavone (PD-98059), and 1,9-pyrazoloanthrone (SP600125) were from Enzo Life Sciences. All inhibitors were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide, except for U-73122, which was dissolved in chloroform, and 3-MA, which was directly dissolved in the culture medium. All other chemicals were from Applichem, Fluka, Merck, or Sigma. If not stated differently, all of the chemicals used as inhibitors were simultaneously administered with the H2O2 treatment.

Cellular subfractionation.

Isolation of cell nuclei was performed as described before (7). Briefly, MEFs were harvested and washed twice with Tris-HCl (pH 7.0)–0.13 M NaCl–5 mM KCl–7.5 mM MgCl2. After incubation in 3.5 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.8)–3 mM NaCl–0.5 mM MgCl2 for 5 min, cells were mechanically broken. Homogenate was mixed with 1/9 of the cell volume of 0.35 M Tris-HCl (pH 7.8)–0.2 M NaCl–50 mM MgCl2 and spun for 3 min at 1,600 × g. The pellet (nuclei) was harvested directly in Laemmli buffer and subsequently analyzed by Western blotting. All procedures were performed on ice.

Antibodies for Western blot detection.

The primary antibodies used were anti-pAKT (S473; R&D Systems; 1:4,000), anti-pAMPKα (Cell Signaling; 1:1,000), anti-Atg7 (Cell Signaling; 1:1,000), anti-Atg12 (D88H11 XP; Cell Signaling; 1:1,000), anti-BECN1 (H-300; Santa Cruz Biotechnology; 1:1,000), anti-CREB (48H2; Cell Signaling; 1:1,000), anti-pCREB (Ser133; Cell Signaling; 1:1 000), anti-ERK1/2 (R&D Systems; 1:1,000), anti-pERK1/2 [(T202/Y204)/(T185/Y187); R&D Systems; 1:2,000], anti-glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (anti-GAPDH; Ambion; 1:100,000), anti-inositol triphosphate (anti-IP3) receptor 1 (Millipore; 1:500), anti-LC-3B (G40; Cell Signaling; 1:1,000), anti-MSK1 (C27B2; Cell Signaling; 1:1,000), anti-pMSK1 (Cell Signaling; 1:1,000), anti-PARP1 (C2-10; Alexis; 1:5,000), anti-PARP2 (4G8; Alexis; 1:50), anti-pPERK (Thr 980; Cell Signaling; 1:1,000), anti-SAPK/JNK (56G8; Cell Signaling; 1:1,000), anti-pSAPK/JNK (Thr183/Tyr185 G9; Cell Signaling; 1:2,000), anti-α-tubulin (Cell Signaling; 1:50,000), anti-Topo-1 (BD Biosiences; 1:5,000), anti-p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK; Cell Signaling; 1:1,000), anti-p-p38 MAPK (Thr180/Tyr182 3D7; Cell Signaling; 1:1,000), anti-p62 (Cell Signaling; 1:1,000), and anti-p-p70S6 kinase (Cell Signaling; 1:1,000). All secondary antibodies were from Sigma.

Immunoblot assays were performed as described previously (7). Equal quantities of protein were loaded into each lane for SDS-PAGE separation as controlled by the simultaneous use of internal protein standards.

Calcium measurements and visualization.

Calcium measurements and visualization were performed as described before (3). Briefly, 20,000 cells/well in 96-well plates (Costar; Corning Incorporated) were washed twice with 49 parts of calcium-free Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS; 0.49 mM MgCl2, 0.41 mM MgSO4, 5.33 mM KCl, 0.44 mM KH2PO4, 4.17 mM NaHCO3, 137 mM NaCl, 0.34 mM Na2HPO4, 5.56 mM dextrose) supplemented with 1 part 1 M HEPES (pH 7.2; assay buffer) containing or not containing CaCl2. A 100-μl volume of Fluo-4-NW dye mix from Molecular Probes (Invitrogen) was added, and the mixture was incubated for 30 min at 37°C and then incubated for 30 min in the dark at room temperature. Changes in the number of relative fluorescence units (ΔRFU) emitted by the Fluo-4-NW dye quantified alterations in cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations (excitation and emission wavelengths, 485 and 535 nm; slits, 10 and 15 nm) in an LS55 luminescence spectrometer (Perkin-Elmer) after H2O2 treatment. Ca2+ was monitored for 30 min with a 0.1-s interval between measurements. Every 50th time point was taken for analysis. For Ca2+ visualization, Fluo-4-loaded cells were analyzed 0.5 and 2 h after H2O2 treatment in a fluorescence microscope (Nikon).

Immunofluorescence.

Cells were seeded onto coverslips (Thermo Scientific) in six-well plates (Costar; Corning Incorporated), washed twice with OPTI-MEM I, and then treated with H2O2. Cells were fixed with ice-cold methanol. Coverslips were subsequently washed with 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and incubated with blocking buffer (1× PBS, 3% milk powder, 1.5% bovine serum albumin) overnight at 4°C. The primary antibodies (all diluted 1:200 in blocking buffer) used were anti-LC-3B (G40; Cell Signaling), anti-PAR (Alexis), and anti-PCNA (BD Biosciences). After incubation for 1 h at 37°C, coverslips were washed three times with blocking buffer and then subjected to a second antibody incubation (1:200) for 1 h at 37°C in the dark. Probes were washed once with blocking buffer and twice with 1× PBS. If desired, Hoechst 33342 (stock, 1 mg/ml; 1:10,000 in PBS; 15 min) was added at room temperature. Probes were washed three times with 1× PBS and dried afterward. Coverslips were processed further with the ProLong Antifade kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Visualization of acidic organelles.

Cells were seeded into μ-Dishes (ibidi) and washed twice with 1× PBS. Monolayers of cells were covered with 200 μl of labeling solution from the GFP-Certified Lyso-ID Red Lysosomal detection kit (Enzo Life Sciences) and incubated for 30 min at 37°C in the dark. Cells were washed with 200 μl of 1× assay buffer and analyzed by fluorescence microscopy (Nikon).

Viability assay.

Cells were seeded into 96-well plates (15,000 cells/well). Cells were treated at 50 μl/well with H2O2 diluted in OPTI-MEM I for 1 h before 150 μl DMEM was added. After 20 h, the medium was replaced with 200 μl DMEM–10% (vol/vol) AlamarBlue (Biozol). After 4 h, fluorescence was monitored at an excitation wavelength of 530 nm and an emission wavelength of 590 nm in an LS55 luminescence spectrometer.

Statistical analysis.

If not stated differently, all results are shown as the mean ± the standard deviation (SD) of the indicated number of independent experiments. The significance of differences was estimated by analysis of variance (ANOVA), and a P value of <0.05 was considered significant. All statistical analyses were calculated with InStat3 or Prism software 5.0b (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

RESULTS

The activation of PARP1 by oxidant-induced DNA strand breaks plays a dominant role in H2O2-induced cytosolic Ca2+ shifts and cytotoxicity.

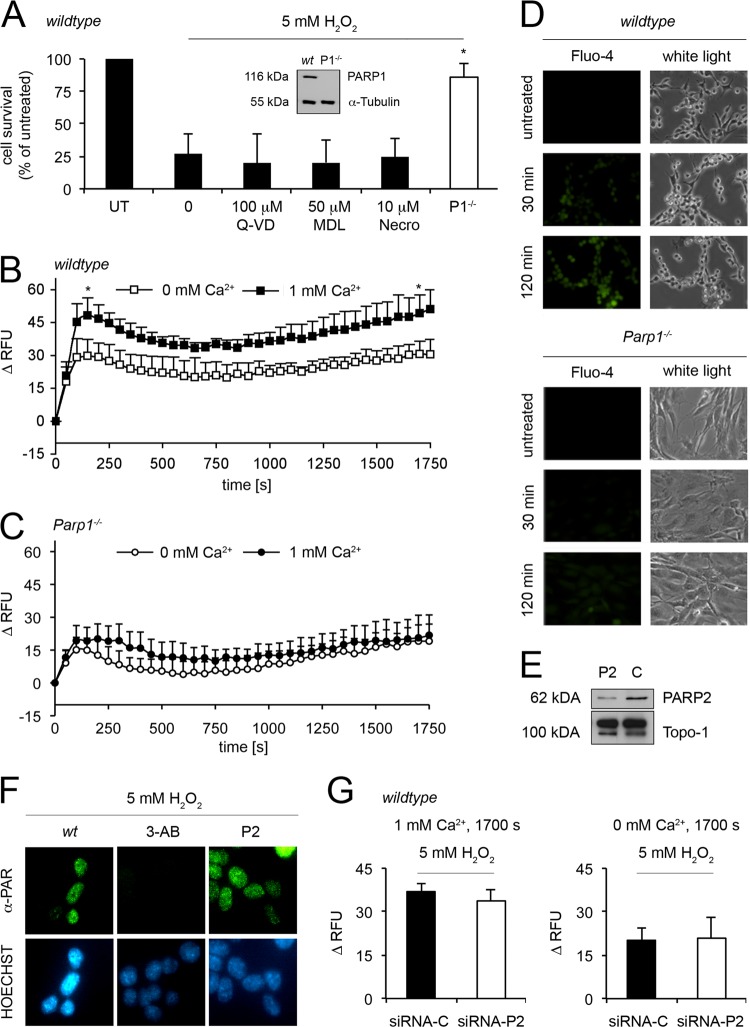

MEFs lacking the Parp1 gene (Fig. 1A) showed remarkable resistance to the cytotoxicity of 5 mM H2O2, in contrast to Parp1-carrying cells. While only 25% of the WT cells survived, more than 75% of the Parp1−/− cells recovered 20 h after a challenge. To determine the type of stress pathway involved in H2O2 toxicity, we investigated three different cell death inhibitors (Fig. 1A). The caspase inhibitor Q-VD-OPh, the calpain inhibitor MDL 28170, and necrostatin 1 all failed to protect WT cells against oxidant-induced toxicity, suggesting that PARP1 controls a different cell death pathway.

Fig 1.

Impact of H2O2 on cell survival, Ca2+ levels in WT and Parp1−/− cells, and the role of PARP2 in WT cells. (A) WT cells were treated (additional 1 h pretreatment) with Q-VD-OPh (100 μM; n = 4), MDL 28170 (50 μM; n = 3) or necrostatin 1 (no pretreatment; 10 μM; n = 7) and 5 mM H2O2 (mean ± SD; not significant; t test). Parp1−/− (P1−/−) cells were also treated with 5 mM H2O2 (mean ± SD; *, P < 0.0001; n = 7; t test). Cell survival was monitored by AlamarBlue. Western blot analysis of PARP1 in untreated (UT) WT and Parp1−/− cells. α-Tubulin was used as the control. (B) Fluo-4 assay of WT cells treated with 5 mM H2O2. Ca2+ determinations with and without extracellular Ca2+ ions were made directly after treatment with H2O2 for 30 min and were expressed as ΔRFU compared to the basal levels (mean ± SD; *, P < 0.005; n = 4; t test). (C) Ca2+ shifts after the treatment of Parp1−/− cells with 5 mM H2O2 with and without extracellular Ca2+ ions (mean ± SD; not significant; n ≥ 5; t test). (D) Microscopic visualization of intracellular Ca2+ shifts after a challenge of WT and Parp1−/− cells with 5 mM H2O2 (for 30 or 120 min) using the Ca2+ indicator Fluo-4. White light was used as the control. (E) Western blot analysis of WT cells with Parp2 (P2) or a control (C) silenced. Topo-1 was the loading control. (F) PAR detection and Hoechst staining by immunofluorescence after treatment with 5 mM H2O2 (30 min) in control MEFs (WT) and cells treated overnight with 3 mM 3-AB or with Parp2 silenced (P2). (G, left side) Comparison of Ca2+ levels at 1,700 s in WT cells with Parp2 (siRNA-P2) or a control (siRNA-C) silenced after treatment with 5 mM H2O2 (mean ± SD; not significant; n = 4; t test) with extracellular Ca2+. (G, right side) Comparison of Ca2+ levels at 1,700 s in WT cells with Parp2 (siRNA-P2) or a control (siRNA-C) silenced after treatment with 5 mM H2O2 (mean ± SD; not significant; n ≥ 4; t test) without extracellular Ca2+.

Ca2+ shifts play an important role in cell death induction (39), and therefore we determined the role of PARP1 in regulating cytosolic Ca2+ shifts. H2O2 induced a biphasic elevation of cytosolic Ca2+, as determined in Fluo-4 Ca2+ assays (Fig. 1B). It started with an immediate peak (150 s), followed by a recovery period (minimal at 650 s) and a subsequent rise (up to 1,700 s). This final rise could be attributed to the PARP1/PARG-dependent formation of ADPR and its interaction with plasma membrane TRPM2 channels (3). The cytosolic Ca2+ influx originates from both extra- and intracellular Ca2+ sources (Fig. 1B). In contrast, when Parp1−/− cells were challenged with 5 mM H2O2, the increase in cytosolic Ca2+ was only moderate and independent of extracellular Ca2+ (Fig. 1C). The Ca2+ shifts (or their absence in Parp1−/− cells) were observed in all of the cells of the population and also after prolonged exposure to H2O2, as demonstrated by microscopy of Fluo-4 signals (Fig. 1D). Constitutive cytosolic Ca2+ is detectable in both cell types and is apparently not affected by Parp1 ablation (see Fig. S1A to D in the supplemental material).

In order to elucidate the possible involvement of PARP2, the second PARP activated by DNA strand breaks (38), we silenced Parp2 in WT cells by RNAi as described previously (7). While Parp2 silencing was effective (Fig. 1E), it did not have any effect on PAR levels (Fig. 1F), Ca2+ shifts (Fig. 1G), or H2O2-induced cell death (see Fig. S2A in the supplemental material). Additionally, we saw similar effects in cells with abrogated TRPM2 (see Fig. S2B). Thus, when cells were challenged with 5 mM H2O2 for 30 min, PARP2 did not seem to play a role in cytosolic Ca2+ shifts involved in cell death signaling, demonstrating the predominant role of PARP1 (Fig. 1F). siRNA against Parp2 or its controls did not affect cytosolic Ca2+ levels (see Fig. S1G to J in the supplemental material), nor did it affect Ca2+ shifts after H2O2 challenge (see Fig. S2C and D). To discriminate the sources of cytosolic Ca2+ shifts, we performed assays in the absence of extracellular Ca2+. We found that Ca2+ released from intracellular compartments was not altered by RNAi against Parp2 (Fig. 1G, right side; see Fig. S2D). These data confirmed the dominant role of PARP1 in oxidant-induced cell death.

PARP1 and PI3K orchestrate the cytosolic Ca2+ response to H2O2 and subsequent cell death.

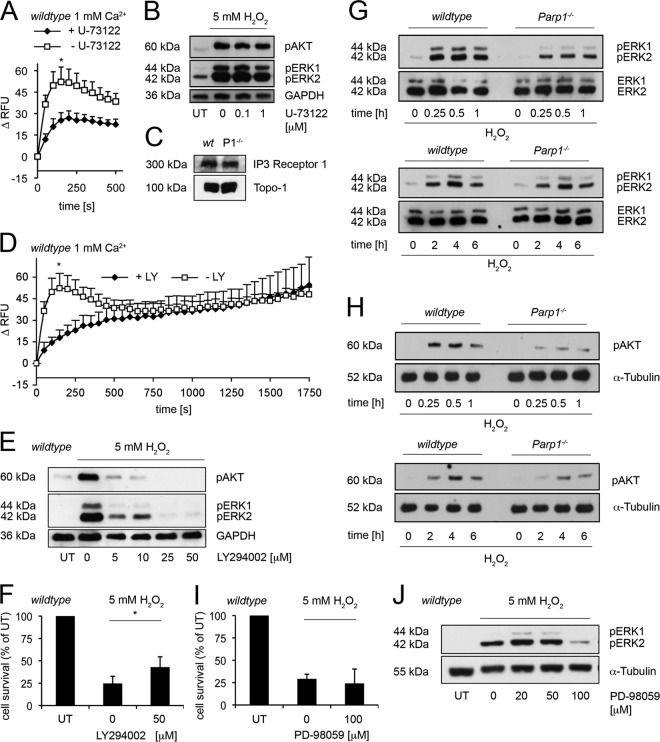

IP3 is a likely candidate for generating the first Ca2+ peak in H2O2-induced cell death (13, 20, 28, 32). Therefore, IP3 synthesis was blocked by the phospholipase C (PLC) inhibitor U-73122 and cytosolic Ca2+ signals were determined with Fluo-4. While U-73122 (1 μM) suppressed the initial Ca2+ peak (Fig. 2A), which was evident only in WT cells, it did not affect basal levels of cytosolic Ca2+ (see Fig. S1E in the supplemental material). Interestingly, U-73122 had no effect on extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2) and AKT, which occurred 30 min after H2O2 treatment (Fig. 2B). Figure 2C shows that IP3 receptor 1 was expressed at equal levels in WT and Parp1−/− cells. We then investigated PI3K signaling, performing assays in the presence of the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 together with 5 mM H2O2 (Fig. 2D to F). In fact, 50 μM LY294002 suppressed the first cytosolic Ca2+ peak at 150 s (Fig. 2D). LY294002 alone had no effect on cytosolic Ca2+ kinetics (see Fig. S1F). The second rise in cytosolic Ca2+ was not altered by LY294002, indicating two distinct mechanisms, an early PI3K-mediated pathway (Fig. 2) and a late PARP1-derived pathway (Fig. 1 and 2). As expected, neither U-73122 nor LY294002 had any effect on cytosolic Ca2+ elevations in cells lacking Parp1 (see Fig. S2E and F in the supplemental material).

Fig 2.

PI3K acts upstream in oxidant-induced cell death. (A) Cytosolic Ca2+ shifts after treatment with 5 mM H2O2 in control (− U-73122) WT cells and those treated with 1 μM U-73122 (+ U-73122). Results represent the mean ± SD (*, P < 0.0005; n ≥ 3; t test). (B) Western blot analysis of pAKT and pERK1/2 in WT cells treated with different doses of U-73122 as indicated (pretreatment for 5 min) and 5 mM H2O2 for 30 min. GAPDH was used as the control. (C) Western blot analysis of IP3 receptor 1 in WT and Parp1−/− (P1−/−) cells shown. Topo-1 was the loading control. (D) Cytosolic Ca2+ shifts after treatment with 5 mM H2O2 in control (− LY) WT cells and those treated with 50 μM LY294002 (+ LY) (pretreatment for 30 min). Results represent the mean ± SD (*, P < 0.0001; n ≥ 3; t test). (E) Western blot analysis of pAKT and pERK1/2 in WT cells treated with different doses of LY294002 as indicated (pretreatment for 30 min) and 5 mM H2O2 for 30 min. GAPDH was used as the control. (F) Cytotoxicity assay of WT cells treated or not treated with LY294002 (1 h pretreatment, 50 μM) and 5 mM H2O2 (mean ± SD; *, P < 0.05; n = 4; t test). (G) Western blot analysis of phosphorylated ERK1/2 (pERK1/2). ERK1/2 was used as the control for WT and Parp1−/− cells treated with 5 mM H2O2 for the times indicated. (H) Western blot analysis of phosphorylated AKT (pAKT) in 5 mM H2O2-treated WT and Parp1−/− MEFs at the indicated time points. α-Tubulin was the loading control. (I) Cytotoxicity assay of WT cells treated or not treated with PD-98059 (pretreatment overnight) and 5 mM H2O2 (mean ± SD; not significant; n = 3; t test). (J) Western blot analysis of pERK1/2 in WT cells treated with PD-98059 as indicated (pretreatment overnight) and 5 mM H2O2 for 1 h. α-Tubulin was the loading control. UT, untreated.

LY294002 decreased downstream phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and AKT, which occurred 30 min after H2O2 treatment, in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2E). Moreover, wortmannin, another PI3K inhibitor, confirmed our findings (see Fig. S2G in the supplemental material). Finally, we tested the effect of LY294002 on the cytotoxicity of 5 mM H2O2 in WT cells (Fig. 2F). LY294002 increased the survival of cells from 24.6% ± 8.06% to 43.0% ± 11.54%. The parallel incubation of 5 mM H2O2-treated Parp1−/− cells in LY294002 did not alter the survival rates (data not shown). Taken together, these results point to an early PI3K-dependent Ca2+ mobilization in PARP1-dependent cell death after H2O2 treatment. Both Parp1−/− cells lacking the first immediate PI3K-controlled Ca2+ shift (Fig. 1C) and inhibition of its downstream signals in the WT background (Fig. 2A and D) led to elevated cell survival (Fig. 1A and 2F).

We then investigated the PARP1 dependence of Ca2+ signaling at early (0.25 and 0.5 h) and late (1, 2, 4, and 6 h) time points. Phosphorylation of the ERK1/2 and AKT proteins after treatment with 5 mM H2O2 (Fig. 2G and H) strongly correlated with IP3-mediated Ca2+ in WT but not in Parp1−/− mutant cells. In general, phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and AKT was faster and more abundant in WT than in Parp1−/− cells. In WT cells, a maximal level of phosphorylated ERK1/2 and AKT already occurred between 0.25 and 1 h. Concomitant incubation of H2O2 with the inhibitors LY294002 and wortmannin suppressed the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and AKT at 0.5 h (Fig. 2E; see Fig. S2G in the supplemental material) and its mediated cytosolic Ca2+ signal dose dependently (Fig. 2A and D). Thus, there is a functional link between PARP1 and Ca2+-mediated stress signaling. Remarkably, inhibition of ERK1/2 phosphorylation downstream of IP3, using the MEK inhibitor PD-98059 (Fig. 2J), could not rescue cell viability (Fig. 2I). Thus, IP3 is an upstream signal for oxidant-induced cell death.

The role of PARP1 in Ca2+-independent stress signaling.

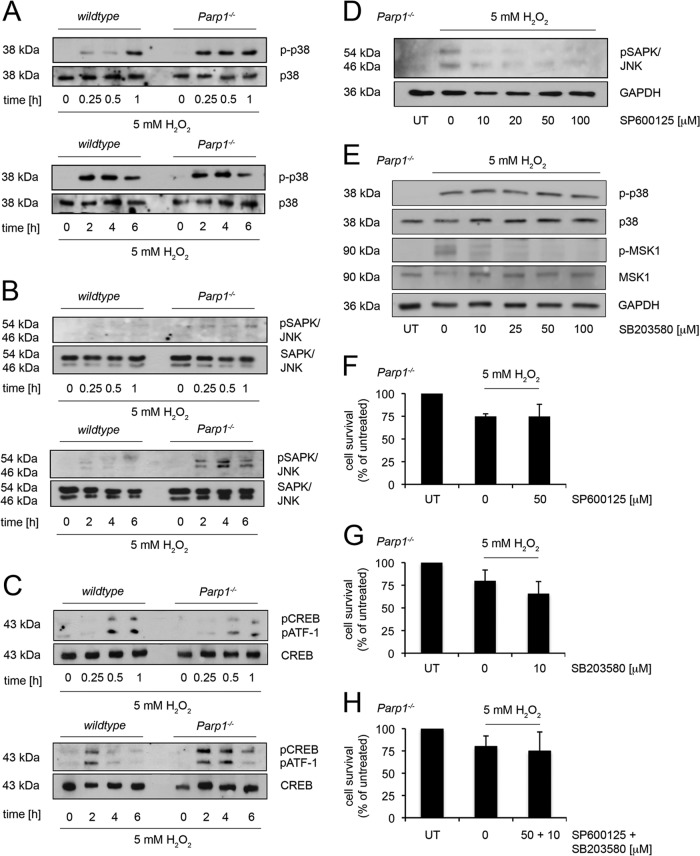

Stress response kinases are activated in a Ca2+-independent manner (2, 17, 22, 37). Therefore, we analyzed the phosphorylation of p38, stress-activated protein kinase/Jun amino-terminal kinase (SAPK/JNK), and their related transcription factors cyclic AMP response element-binding protein (CREB) and its activating transcription factor (ATF-1) in WT and Parp1−/− cells (Fig. 3A to C). P38 phosphorylation was faster (1 h) in 5 mM H2O2-challenged Parp1−/− cells than in WT cells (0.25 h) (Fig. 3A). Moreover, activation of SAPK/JNK was detectable only in Parp1−/− cells, at 2, 4, and 6 h posttreatment with a maximum at 4 h, and not in WT cells (Fig. 3B). As expected, the phosphorylation of SAPK/JNK led to the subsequent phosphorylation of their downstream transcription factors CREB and ATF-1 (Fig. 3C). In the next set of experiments, we investigated the effects of JNK and p38 inhibitors on cell survival in H2O2-treated Parp1−/− cells (Fig. 3D to H). First, we included the inhibitor SP600125, which is selective for JNK1, -2, and -3, to evaluate a possible survival function of phosphorylated SAPK/JNK in H2O2-treated Parp1−/− cells (Fig. 3D and F). SAPK/JNK phosphorylation was inhibited (Fig. 3D), but this had no impact on Parp1−/− cell death (Fig. 3F). Likewise, we analyzed the effect of SB203580, an inhibitor of p38 signaling (Fig. 3E and G). As expected, SB203580 reduced the phosphorylation of the p38 downstream factor MSK1 in a dose-dependent manner without any effect on the phosphorylation status of p38 itself (Fig. 3E). The parallel application of SB203580 in H2O2-challenged Parp1−/− cells did not interfere with the overall survival rates (Fig. 3G), and also combined treatment with SP600125 and SB203580 did not alter the response of H2O2-treated Parp1−/− cells (Fig. 3H).

Fig 3.

The role of PARP1 in Ca2+-independent stress signaling. (A) Western blot analysis of p-p38 in WT and Parp1−/− cells treated with 5 mM H2O2 for the times indicated. Unphosphorylated p38 was the loading control. (B) Western blot analysis of pSAPK/JNK in WT and Parp1−/− cells treated with 5 mM H2O2 for the times indicated. Unphosphorylated SAPK/JNK was the loading control. (C) Western blot analysis of pCREB and pATF-1 in WT and Parp1−/− cells treated with 5 mM H2O2 for the times indicated. Unphosphorylated CREB was the loading control. (D) Western blot analysis of pSAPK/JNK in Parp1−/− cells treated with increasing doses of SP600125 (1 h pretreatment) as indicated and 5 mM H2O2 for 4 h. GAPDH was the loading control. (E) Western blot analysis of p-p38, p-38, p-MSK1, and MSK1 in Parp1−/− cells treated with 5 mM H2O2 and increasing doses of SB203580 as indicated for 2 h. GAPDH was the loading control. (F) Survival was monitored in Parp1−/− cells treated with 50 μM SP600125 (1 h pretreatment) and 5 mM H2O2 (mean ± SD; not significant; n = 3; t test). (G) Survival was monitored in Parp1−/− cells treated with 10 μM SB203580 (1 h pretreatment) and 5 mM H2O2 (mean ± SD; not significant; n = 4; t test). (H) Survival was monitored in Parp1−/− cells treated with 50 μM SP600125 together with 10 μM SB203580 (1 h pretreatment) and 5 mM H2O2 (mean ± SD; not significant; n = 4; t test). UT, untreated.

In conclusion, we identified two distinct cellular stress responses to H2O2: a PARP1- and PI3K-dependent response involving Ca2+ signaling and phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and AKT leading to cell death and a PARP1-independent response involving the preferential phosphorylation of p38, SAPK/JNK, and CREB/ATF-1 leading to survival.

PARP1 and Ca2+ is involved in autophagy signaling.

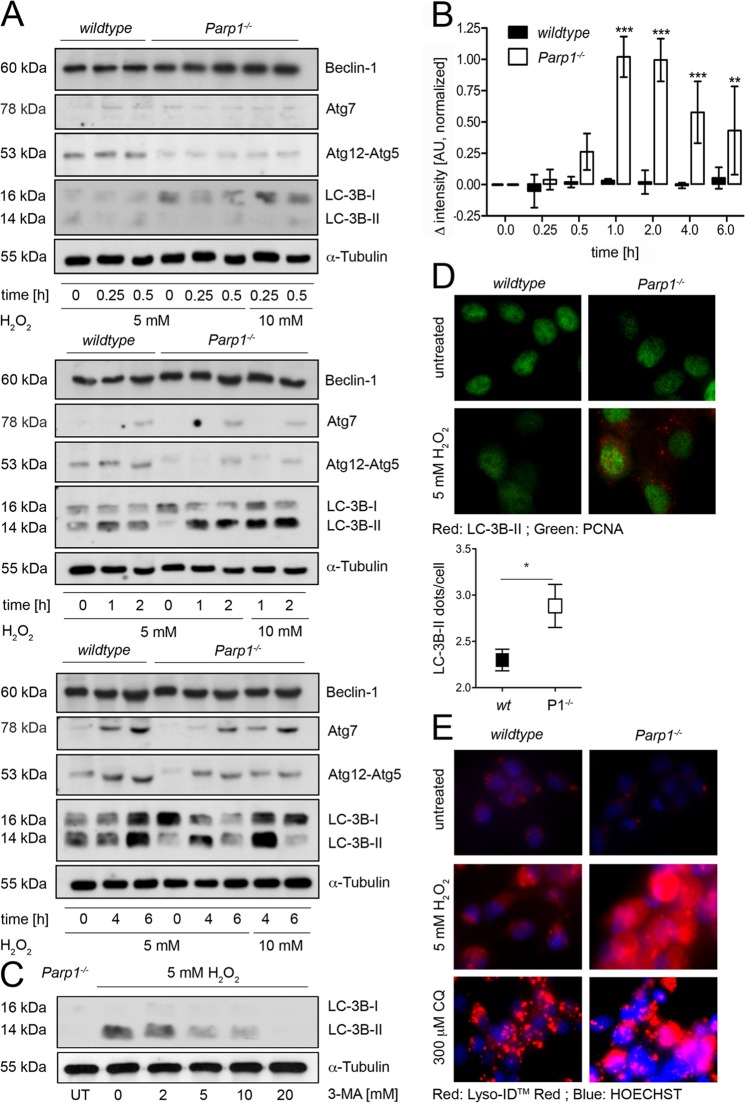

Autophagy is an organized clearance mechanism that delivers damaged cell structures to lysosomes for subsequent degradation (18, 26, 34). H2O2 induces autophagy, and this is associated with lysosomal Ca2+ release (5, 25, 33). The results in Fig. 4A show that H2O2 induces early autophagy markers in WT and Parp1−/− cells (15). While beclin-1 was expressed constitutively, Atg7 and an Atg12-Atg5 complex were induced by H2O2 in WT cells and with some delay in Parp1−/− cells. However, the autophagy marker microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain (Map1lc3b; LC-3B-II) was evident only in Parp1−/− cells (Fig. 4A to C), suggesting that PARP1 suppresses late-stage autophagy. In fact, LC-3B lipidization is a marker of autophagosome formation. It is activated by the Atg-7-mediated conjugation of phosphatidylethanolamine. Figure 4B shows the course of LC-3B-II formation in Parp1−/− cells and the virtual absence of this marker in WT cells. Nevertheless, while WT cells failed to display LC-3B-II in response to H2O2, they retained the expected LC-3B-II formation in starvation-induced autophagy (see Fig. S3C in the supplemental material). Likewise, LC-3B-II could also be induced with bafilomycin A1 (4, 14, 19), a canonical lysosomal Ca2+ releaser (see Fig. S3A and B). LC-3B-II induction in Parp1−/− cells was sensitive to the autophagy inhibitor 3-MA (Fig. 4C). Microscopic analysis demonstrated the distribution of LC-3B-II immunofluorescence dots exclusively in H2O2-treated Parp1−/− cells and not in untreated and WT cells (Fig. 4D). The fusion of lysosomes with the autophagosome is the final step in autophagy. To monitor this, we determined lysosomal activity by using the acidity-selective dye Lyso-ID in WT and Parp1−/− cells challenged with 5 mM H2O2 for 2 h. Figure 4E shows massively induced lysosomal activity in Parp1−/− but not in WT cells. The lysosome-perturbing agent chloroquine (CQ), which regulates changes in lysosome number, was used as a positive control (Fig. 4E). From these data, we conclude that PARP1 is a suppressor of H2O2-induced autophagy.

Fig 4.

PARP1 is involved in autophagy signaling after H2O2 treatment. (A) Western blot analysis of beclin-1, Atg7, Atg12-Atg5, and LC-3B-II in WT or Parp1−/− cells after H2O2 treatment as indicated. α-Tubulin was the loading control. (B) Statistical analysis of LC-3B-II Western blot signals of 5 mM H2O2-treated WT or Parp1−/− cells at the indicated time points. Results are shown as arbitrary units (AU) normalized to GAPDH or α-tubulin (mean ± SD; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; n ≥ 4; two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni multiple-comparison posttest). (C) Western blot analysis of LC-3B-II in Parp1−/− cells pretreated for 1 h with increasing doses of 3-MA before a challenge with 5 mM H2O2 for 2 h. (D, top) LC-3B-II and PCNA staining by immunofluorescence in WT and Parp1−/− cells treated with 5 mM H2O2 after 2 h. (D, bottom) Quantification of LC-3B-II dots in WT (n = 142) and Parp1−/− cells (P1−/−; n = 94) after 2 h of H2O2 treatment (mean ± standard error of the mean; *, P < 0.025; t test). Only LC-3B-II-positive cells were considered. (E) Visualization of acidic organelles with Lyso-ID Red dye in WT and Parp1−/− cells after 2 h of 5 mM H2O2 treatment or after 2 h of 300 μM CQ treatment with Hoechst staining as the control. UT, untreated.

Autophagy plays an integrative role in PARP1-dependent cell death after H2O2 treatment.

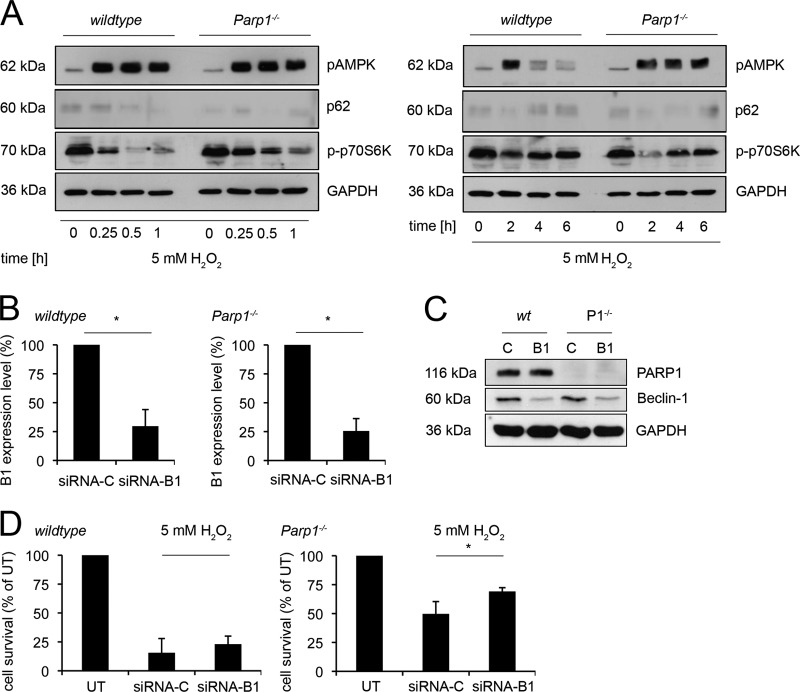

The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) complex is an integrative negative regulator in autophagy signaling and senses growth factors, nutrients, and energy availability (18, 26, 34). First, we analyzed phosphorylated AMP-activated protein kinase (pAMPK), one of the upstream inhibitors of mTOR, in WT and Parp1−/− cells after H2O2 treatment (Fig. 5A). AMPK phosphorylation was already observed after 0.25 h and maintained until 2 h, regardless of Parp1 status. However, phosphorylated AMPK declined markedly between 2 and 6 h in WT cells but not in Parp1−/− cells. Second, H2O2 initiated mTOR-mediated dephosphorylation of p70S6K in WT and Parp1−/− cells, but it was delayed in the latter (Fig. 5A). Independent of PARP1, phosphorylation of p70S6K was restored to basic levels within 6 h posttreatment, suggesting its dynamic regulation. Remarkably, 1 and 2 h after oxidative damage, phosphorylation of p70S6K was lowest in Parp1−/− cells. A similar pattern was observed in the degradation of p62, a second factor downstream of mTOR activity. This strongly correlates with maximal LC-3B-II conversions in these cells (Fig. 4B). The observed (de)activation of AMPK, p70S6K, and p62 clearly indicates a direct involvement of mTOR signaling in H2O2-induced autophagy. The AMPK and p70S6K expression levels in the two cell types were similar (data not shown). Control experiments using serum starvation showed that mTOR signaling was intact in both of the cell types analyzed (see Fig. S3C in the supplemental material). To determine effects of H2O2-induced autophagy on cell survival, we performed experiments with the autophagy inhibitor 3-MA in Parp1−/− cells. However, no effects were seen, even at an inhibitor concentration of up to 20 mM (see Fig. S3D in the supplemental material). Moreover, the mTOR inhibitor PP242 could enhance H2O2-induced autophagy in Parp1−/− cells as assessed by p-p70S6K, p62, and LC-3B-II conversion 2 h after H2O2 treatment (see Fig. S3E). Interestingly, parallel treatment of PP242 together with H2O2 did not alter the overall cell survival rate (see Fig. S3F).

Fig 5.

H2O2 induction of mTOR-mediated autophagy and role of beclin-1 in H2O2-induced PARP1-dependent cell death. (A) Western blot analysis of phosphorylated AMPK (pAMPK) in WT and Parp1−/− cells at the indicated time points after treatment with 5 mM H2O2. The levels of phosphorylated p70S6K (p-p70S6K) are also shown, as well as p62. α-Tubulin was the loading control. (B) Becn1 mRNA levels of WT and Parp1−/− cells with the Becn1 gene silenced (siRNA-B1) or not silenced (siRNA-C) as determined by RT-PCR normalized to GAPDH (mean ± SD; *, P < 0.0001; n = 3; t test). (C) Western blot analysis of WT and Parp1−/− (P1−/−) cells with Becn1 (B1) or a control (C) silenced. PARP1 and GAPDH were controls. (D) Assay of cytotoxicity of treatment with 5 mM H2O2 of WT (n = 4) and Parp1−/− cells (n = 4) with Becn1 (siRNA-B1) or a control (siRNA-C) silenced (mean ± SD; not significant in WT; *, P < 0.025 in Parp1−/− cells; t test). UT, untreated.

In a more targeted analysis, RNAi silencing of the autophagy upstream regulator Becn1 in Parp1−/− and WT cells (Fig. 4A) was effective at the mRNA (Fig. 5B) and protein levels (Fig. 5C) but did not alter the cell death response in WT cells treated with 5 mM H2O2 (Fig. 5D, left side). Nevertheless, the autophagy-proficient Parp1−/− cells displayed a higher survival rate when challenged with 5 mM H2O2 (Fig. 5D, right side), suggesting that beclin-1-dependent autophagy does not rescue cells from cell death.

PARP2 as a back-up mechanism for PAR synthesis and Ca2+ signaling in Parp1−/− cells.

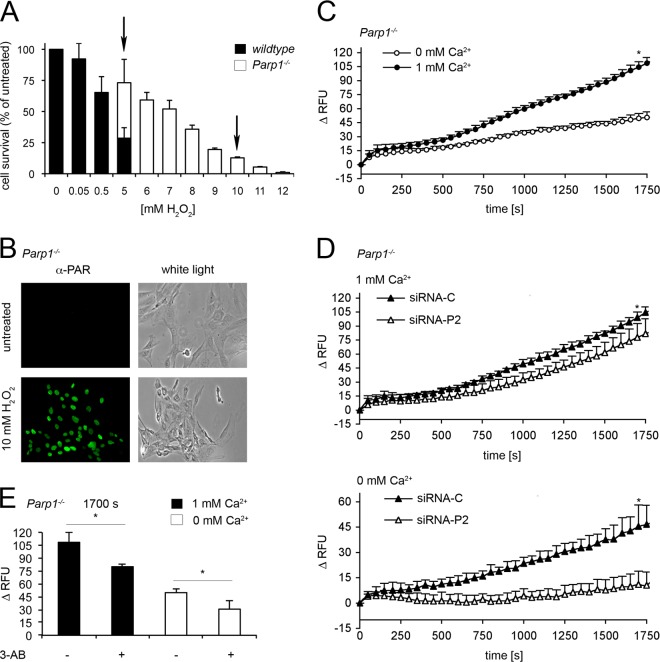

Parp1−/− cells were markedly more resistant to H2O2 than WT cells were (Fig. 6A and 1A). An H2O2 concentration (5 mM) 10 times higher than in WT cells (0.5 mM) was needed to induce a cell death rate of 25% in Parp1−/− cells. A 5 mM H2O2 concentration led to 75% cell death in WT cells. A 10 mM H2O2 concentration induced equivalent death rates in Parp1−/− cells (Fig. 6A), and this caused substantial PAR synthesis by PARP2 (Fig. 6B; see Fig. S4A in the supplemental material). A rapid increase in cytosolic Ca2+ to more than 100 RFU was observed with almost linear kinetics up to 30 min (Fig. 6C). This was double the amount observed in WT cells challenged with equitoxic doses of H2O2 (Fig. 1B).

Fig 6.

Treatment with 10 mM H2O2 induces PAR formation and cytosolic Ca2+ shifts in Parp1−/− cells. (A) WT and Parp1−/− cells were treated with increasing concentrations of H2O2 as indicated. Cell survival was determined (n ≥ 4). (B) PAR detection in Parp1−/− cells by immunofluorescence after 30 min of treatment with 10 mM H2O2. White light was used as the control. (C) Fluo-4 assay of Parp1−/− cells treated with 10 mM H2O2 with and without extracellular Ca2+. Results represent the mean ± SD (*, P < 0.0001; n = 4; t test). (D, top) Cytosolic Ca2+ shifts of Parp1−/− cells with Parp2 (siRNA-P2) or a control (siRNA-C) silenced after treatment with 10 mM H2O2 in Ca2+-containing buffer (mean ± SD; *, P < 0.05; n = 4; t test). (D, bottom) Same as before but in the absence of extracellular Ca2+ (mean ± SD; *, P < 0.005; n = 4; t test). (E) Comparison of cytosolic Ca2+ levels at 1,700 s after treatment with 10 mM H2O2 in Parp1−/− control and 3-AB treated cells (3 mM 3-AB overnight) in the presence (mean ± SD; *, P < 0.005; n ≥ 3; t test) or absence of extracellular Ca2+ (mean ± SD; *, P = 0.0005; n = 5; t test).

RNAi silencing was used to address the role of PARP2 in Ca2+ signaling in Parp1−/− cells. siRNA-P2 reduced Parp2 mRNA to 36.4% ± 10.65% of control levels (see Fig. S4B in the supplemental material). As a functional consequence, PAR formation by PARP2 was reduced in Parp1−/− cells after treatment with 10 mM H2O2 (see Fig. S4A in the supplemental material). Parp2 silencing reduced the overall cytosolic Ca2+ response from 99.0 ± 5.85 RFU (siRNA-C) to 77.9 ± 14.59 RFU (siRNA-P2) at 1,700 s (Fig. 6D, top) in the presence of extracellular Ca2+. Interestingly, the silencing effect on intracellular Ca2+ release was greater (Fig. 6D, bottom), suggesting that PARP2 regulates Ca2+ release from intracellular stores. The PARP inhibitor 3-AB also reduced Ca2+ shifts (Fig. 6E; see Fig. S4C and D in the supplemental material), indicating that PARP2 catalytic activity is involved. The peak levels of Ca2+ abrogation obtained with siRNA-P2 and 3-AB were similar (21 versus 25 RFU at 1,700 s). More importantly, this effect was also observed in Parp1−/− cells incubated with 3-AB in the absence of extracellular Ca2+ (Fig. 6E; see Fig. S4D). Parp2 silencing or incubation with 3-AB did not alter the baseline cytosolic Ca2+ levels of unchallenged cells (see Fig. S1M, N, Q, and T in the supplemental material). Taken together, these observations suggest that PARP2 activity controls an intracellular Ca2+ release mechanism.

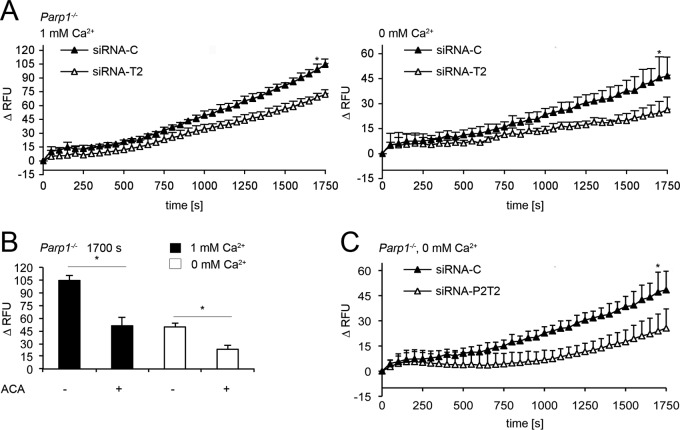

PARP2 activity mobilizes intracellular TRPM2 channels in a Parp1−/− background.

We tested the hypothesis that PARP2-sensitive intracellular Ca2+ release after H2O2 treatment in Parp1−/− cells could be mediated by TRPM2. RNAi silencing of Trpm2 in Parp1−/− cells challenged with 10 mM H2O2 reduced cytosolic Ca2+ responses (Fig. 7A, left side). Repeating these experiments in the absence of extracellular Ca2+ again suggested an intracellular source of Ca2+ (Fig. 7A, right side). To verify this, we used the broad-spectrum inhibitor of TRP channels ACA (1) (Fig. 7B; see Fig. S4E and F in the supplemental material). As expected, treatment with ACA reduced the cytosolic Ca2+ response to H2O2 in Parp1−/− cells when extracellular Ca2+ was present (Fig. 7B; see Fig. S4E), as well as in the absence of extracellular Ca2+ (Fig. 7B; see Fig. S4F). In fact, Ca2+ release from intracellular sources was the same in siRNA-C-transfected cells (45.5 ± 12.59 RFU, Fig. 7A, right side) and Parp1−/− cells without ACA (49.6 ± 5.03 RFU, Fig. 7B; see Fig. S4F). In addition, blocking TRPM2 activity by either siRNA-T2 (Fig. 7A, right side) or ACA (Fig. 7B; see Fig. S4F) reduced this level to 24.3 ± 7.01 or 23.3 ± 4.99 RFU in the absence of extracellular Ca2+, respectively. Trpm2 silencing or ACA incubation did not induce cytosolic Ca2+ differences of unchallenged cells (see Fig. S1K, L, O, and P in the supplemental material). Moreover, double silencing of Parp2 and Trpm2 (siRNA-P2T2) could not additionally promote this effect (Fig. 7C; see Fig. S1U). Thus, Ca2+ release from intracellular compartments is an integral part of the H2O2 response of Parp1−/− cells and is under the control of PARP2 (Fig. 6D and E; see Fig. S4C and D) and TRPM2 (Fig. 7A to C; see Fig. S4E and F).

Fig 7.

Intracellular TRPM2 channels release Ca2+ in Parp-1−/− cells after H2O2 treatment. (A, left side) Fluo-4 assays with extracellular Ca2+ in Parp1−/− cells with Trpm2 (siRNA-T2) or a control (siRNA-C) silenced after treatment with 10 mM H2O2 (mean ± SD; *, P < 0.00025; n = 4; t test). (A, right side) Fluo-4 assays done as before but without extracellular Ca2+ (mean ± SD; *, P < 0.05; n ≥ 3; t test). (B) Comparison of cytosolic Ca2+ levels at 1,700 s after treatment with 10 mM H2O2 in Parp1−/− control and ACA-treated cells (pretreatment for 5 min; 5 μM) with extracellular Ca2+ (mean ± SD; *, P < 0.0001; n ≥ 3; t test) and without Ca2+ (mean ± SD; *, P = 0.0001; n = 3; t test). (C) Cytosolic Ca2+ shifts in Parp1−/− cells with both Parp2 and Trpm2 (siRNA-P2T2) or a control (siRNA-C) silenced after treatment with 10 mM H2O2 in the absence of extracellular Ca2+ (mean ± SD; *, P < 0.0025; n ≥ 3; t test).

DISCUSSION

Oxidative stress induces DNA damage, Ca2+ mobilization, autophagy, and cell death (Fig. 8). It is not well understood how these stress responses are interconnected and regulated. Here we found that Ca2+ imbalances, primarily gated by two membrane-bound TRPM2 channels, are under the control of two DNA nick-sensing enzymes, PARP1 and PARP2. Using a combination of genetic knockout, silencing, and chemical inhibition, we found that plasma membrane TRPM2 channels are under the control of PARP1 under moderate-stress conditions. Lysosomal TRPM2 seems to be the channel for high-stress conditions, activated by PARP2. Both channels respond to ADPR generated by one of the PARPs in conjunction with PARG, which converts PAR into ADPR (3).

Fig 8.

Roles of PARP1 and PARP2 in the oxidative stress response leading to cell death, autophagy, or cell survival. (A) Summary of PARP1- and PARP2-driven, TRPM2-mediated cytosolic Ca2+ responses after H2O2-induced DNA damage. (B) A moderate stress level (5 mM H2O2) mobilizes Ca2+ via activation of PARP1. PARP1 produces the activating signal (ADPR) for the plasma membrane TRPM2 channel in conjunction with PARG (14). This, in combination with the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and AKT, causes cell death in WT MEFs. A moderate stress level (5 mM H2O2) in a Parp1−/− background involves the phosphorylation of p38, SAPK/JNK, and CREB/ATF-1 and activates autophagy markers, leading to cell survival. PARP1 operates as a checkpoint between cell survival and death or autophagy. A high level of oxidative stress (10 mM H2O2) triggers late autophagy steps and leads to the activation of PARP2 activity in a Parp1−/− background. This ends in Ca2+ mobilization from lysosomes, the only other known localization of TRPM2, leading to cell death.

PARP1 plays the dominant role in H2O2-induced Ca2+ mobilization when cells are navigating toward cell death. The cytosolic Ca2+ shifts originated from both PI3K-mediated and TRPM2-gated Ca2+ sources. Whereas abrogation of PLC and PI3K abolished the first Ca2+ peak at 150 s after H2O2 treatment (Fig. 1 and 2), the subsequent rise in cytoplasmic Ca2+ was not affected (Fig. 2). These findings indicate that there are two different and independent mechanisms by which PARP1 controls the cytosolic Ca2+ stress response. Indeed, Parp1 ablation led to a different stress kinase pattern, resulting in cell survival after exposure to 5 mM H2O2, a dose that killed their WT counterparts (Fig. 1 to 3). Our data also show that PARP1 does not control the entire intracellular Ca2+ mobilization process since there is a substantial amount that could come from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), which contains around 500 μM Ca2+ (31). We found a substantial ER stress response, i.e., protein kinase-like ER kinase phosphorylation (pPERK), regardless of the Parp1 proficiency of the cells (see Fig. S3G in the supplemental material).

PARP2 operates as a backup mechanism under high-stress conditions (10 mM H2O2) in the absence of PARP1. It activates PAR synthesis and subsequent cytosolic Ca2+ shifts (Fig. 6 and 7). As PARP2 generates PAR to a lesser extent than PARP1 does (38), an equitoxic concentration (10 versus 5 mM) is required to advance Parp1−/− cells into the cell death pathway. Moreover, Parp1−/− cell death shows PARP2- and TRPM2-dependent cytosolic Ca2+ responses. In contrast to dying WT cells, PARP2/TRPM2-mediated Ca2+ shifts originate from intracellular compartments (Fig. 6 and 7). TRPM2 localizes to lysosomes, the only other membrane system described, expressing TRPM2 channels (16, 30). TRPM2 channels in lysosomes are associated with cellular functions different from plasma membrane localization, e.g., the differentiation and maturation of dendritic cells (29). Lysosomes represent a substantial pool of 400 to 600 μM Ca2+ (6, 9, 19).

Another major finding was that PARP1 is not required for the late autophagic response. In fact, only Parp1−/− cells showed autophagy markers (Fig. 4A and B) and related autophagy phenotypes (Fig. 4D and E). This suggests that Parp1 is an autophagy suppressor gene. Moreover, H2O2 treatment stimulated the mTOR complex, a negative regulator of autophagy. Phosphorylated AMPK and dephosphorylated p70S6K and p62, all indicative of mTOR signaling, were observed solely in Parp1−/− cells (Fig. 5A). This correlated closely with maximal LC-3B-II conversion in these cells (Fig. 4B). Moreover, the autophagy-proficient Parp1−/− cells with Becn1 silenced displayed a higher survival rate after an oxidative insult. Therefore, beclin-1-dependent autophagy seemed not to rescue these cells from death. In general, beclin-1 exists in a complex with bcl-2 (B-cell lymphoma 2) in the cells and becomes liberated from this complex because of phosphorylation of JNK or p38 kinase to process autophagy (8, 36). Both stress kinases are activated in H2O2-treated Parp1−/− cells (Fig. 3). Therefore, we analyzed inhibitors of JNK and p38. However, none of the chemicals applied or their combination was sufficient to modulate the amount of surviving cells after H2O2 treatment. Nevertheless, both inhibitors successfully repressed their corresponding downstream signaling factors.

In conclusion, this study describes three different stress response scenarios under the control of PARP1 and PARP2 (Fig. 8A and B). First, 5 mM H2O2 causes cell death in the WT background. This cell death is characterized by PARP1 activation with concomitant plasma membrane TRPM2- and PI3K-dependent cytosolic Ca2+ elevations and subsequent ERK1/2 and AKT phosphorylation (Fig. 1 and 2). In contrast, 5 mM H2O2 does not affect cell viability in the absence of PARP1. This type of stress response involves the phosphorylation of p38, MSK1, SAPK/JNK, and CREB/ATF-1 and, beyond that, activates autophagy markers, leading finally to cell survival (Fig. 3 to 5). Third, 10 mM H2O2 is an equitoxic killing dose in the Parp1−/− background compared to in WT cells (Fig. 8B). Here, PARP2 generates TRPM2-dependent cytosolic Ca2+ shifts from an intracellular source, most likely lysosomal, triggering a parallel autophagy pathway leading to cell death (Fig. 6 and 7).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Deana Haralampieva, Theresa Pesch, Christine Uhl, and in particular Cristina Vercelli for their contributions to this work, as well as Sascha Beneke for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation and a grant from the Lotte and Adolf Hotz-Sprenger Foundation, Zurich, awarded to Felix R. Althaus.

We have no conflict of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 2 July 2012

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://mcb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bari MR, et al. 2009. H2O2-induced Ca2+ influx and its inhibition by N-(p-amylcinnamoyl) anthranilic acid in the beta-cells: involvement of TRPM2 channels. J. Cell Mol. Med. 13: 3260–3267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Blanc A, Pandey NR, Srivastava AK. 2003. Synchronous activation of ERK 1/2, p38mapk and PKB/Akt signaling by H2O2 in vascular smooth muscle cells: potential involvement in vascular disease (review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 11: 229–234 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Blenn C, Wyrsch P, Bader J, Bollhalder M, Althaus FR. 2011. Poly(ADP-ribose)glycohydrolase is an upstream regulator of Ca2+ fluxes in oxidative cell death. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 68: 1455–1466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bowman EJ, Siebers A, Altendorf K. 1988. Bafilomycins: a class of inhibitors of membrane ATPases from microorganisms, animal cells, and plant cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 85: 7972–7976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cheng WT, et al. 2009. Oxidative stress promotes autophagic cell death in human neuroblastoma cells with ectopic transfer of mitochondrial PPP2R2B (Bbeta2). BMC Cell Biol. 10: 91 doi:10.1186/1471-2121-10-91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Christensen KA, Myers JT, Swanson JA. 2002. pH-dependent regulation of lysosomal calcium in macrophages. J. Cell Sci. 115: 599–607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cohausz O, Blenn C, Malanga M, Althaus FR. 2008. The roles of poly(ADP-ribose)-metabolizing enzymes in alkylation-induced cell death. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 65: 644–655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. De Chiara G, et al. 2006. Bcl-2 phosphorylation by p38 MAPK: identification of target sites and biologic consequences. J. Biol. Chem. 281: 21353–21361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dong XP, Wang X, Xu H. 2010. TRP channels of intracellular membranes. J. Neurochem. 113: 313–328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Green DR, Galluzzi L, Kroemer G. 2011. Mitochondria and the autophagy-inflammation-cell death axis in organismal aging. Science 333: 1109–1112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hassa PO, Haenni SS, Elser M, Hottiger MO. 2006. Nuclear ADP-ribosylation reactions in mammalian cells: where are we today and where are we going? Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 70: 789–829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Heeres JT, Hergenrother PJ. 2007. Poly(ADP-ribose) makes a date with death. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 11: 644–653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Joseph SK, Hajnoczky G. 2007. IP3 receptors in cell survival and apoptosis: Ca2+ release and beyond. Apoptosis 12: 951–968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kinnear NP, Boittin FX, Thomas JM, Galione A, Evans AM. 2004. Lysosome-sarcoplasmic reticulum junctions. A trigger zone for calcium signaling by nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate and endothelin-1. J. Biol. Chem. 279: 54319–54326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Klionsky DJ, et al. 2010. A comprehensive glossary of autophagy-related molecules and processes. Autophagy 6: 438–448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lange I, et al. 2009. TRPM2 functions as a lysosomal Ca2+-release channel in beta cells. Sci. Signal. 2: ra23 doi:10.1126/scisignal.2000278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lee B, et al. 2009. The CREB/CRE transcriptional pathway: protection against oxidative stress-mediated neuronal cell death. J. Neurochem. 108: 1251–1265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Levine B, Mizushima N, Virgin HW. 2011. Autophagy in immunity and inflammation. Nature 469: 323–335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lloyd-Evans E, et al. 2008. Niemann-Pick disease type C1 is a sphingosine storage disease that causes deregulation of lysosomal calcium. Nat. Med. 14: 1247–1255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Marks AR. 1997. Intracellular calcium-release channels: regulators of cell life and death. Am. J. Physiol. 272: H597–H605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Naziroğlu M. 2011. TRPM2 cation channels, oxidative stress and neurological diseases: where are we now? Neurochem. Res. 36: 355–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nishina H, Wada T, Katada T. 2004. Physiological roles of SAPK/JNK signaling pathway. J. Biochem. 136: 123–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Patel S, Docampo R. 2009. In with the TRP channels: intracellular functions for TRPM1 and TRPM2. Sci. Signal. 2: pe69 doi:10.1126/scisignal.295pe69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Perraud AL, et al. 2001. ADP-ribose gating of the calcium-permeable LTRPC2 channel revealed by Nudix motif homology. Nature 411: 595–599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pyo JO, et al. 2008. Compensatory activation of ERK1/2 in Atg5-deficient mouse embryo fibroblasts suppresses oxidative stress-induced cell death. Autophagy 4: 315–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rabinowitz JD, White E. 2010. Autophagy and metabolism. Science 330: 1344–1348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sallmann FR, Vodenicharov MD, Wang ZQ, Poirier GG. 2000. Characterization of sPARP1. An alternative product of PARP1 gene with poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase activity independent of DNA strand breaks. J. Biol. Chem. 275: 15504–15511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sarkar S, Rubinsztein DC. 2006. Inositol and IP3 levels regulate autophagy: biology and therapeutic speculations. Autophagy 2: 132–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sumoza-Toledo A, et al. 2011. Dendritic cell maturation and chemotaxis is regulated by TRPM2-mediated lysosomal Ca2+ release. FASEB J. 25: 3529–3542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sumoza-Toledo A, Penner R. 2011. TRPM2: a multifunctional ion channel for calcium signalling. J. Physiol. 589: 1515–1525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Szabadkai G, Duchen MR. 2008. Mitochondria: the hub of cellular Ca2+ signaling. Physiology (Bethesda) 23: 84–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Szlufcik K, Missiaen L, Parys JB, Callewaert G, De Smedt H. 2006. Uncoupled IP3 receptor can function as a Ca2+-leak channel: cell biological and pathological consequences. Biol. Cell 98: 1–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Szumiel I. 2011. Autophagy, reactive oxygen species and the fate of mammalian cells. Free Radic. Res. 45: 253–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tanida I. 2011. Autophagy basics. Microbiol. Immunol. 55: 1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tóth B, Csanady L. 2010. Identification of direct and indirect effectors of the transient receptor potential melastatin 2 (TRPM2) cation channel. J. Biol. Chem. 285: 30091–30102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wei Y, Pattingre S, Sinha S, Bassik M, Levine B. 2008. JNK1-mediated phosphorylation of Bcl-2 regulates starvation-induced autophagy. Mol. Cell 30: 678–688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wu GS. 2007. Role of mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatases (MKPs) in cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 26: 579–585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yélamos J, Schreiber V, Dantzer F. 2008. Toward specific functions of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-2. Trends Mol. Med. 14: 169–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zhivotovsky B, Orrenius S. 2011. Calcium and cell death mechanisms: a perspective from the cell death community. Cell Calcium 50(3): 211–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.