Abstract

B cells represent an important link between the adaptive and innate immune systems, as they express both antigen-specific B cell receptors (BCRs) as well as various toll-like receptors (TLRs). Several checkpoints in B cell development ensure that self-specific cells are eliminated from the mature B cell repertoire to avoid harmful autoreactive responses. These checkpoints are controlled by BCR-mediated events, but are also influenced by TLR-dependent signals from the innate immune system. Additionally, B cell-intrinsic and extrinsic TLR signaling are critical for inflammatory events required for the clearance of microbial infections. Factors secreted by TLR-activated macrophages or dendritic cells directly influence the fate of protective and autoreactive B cells. Additionally, naïve and memory B cells respond differentially to TLR ligands, as do different B cell subsets. We review here recent literature describing intrinsic and extrinsic effects of TLR stimulation on the fate of B cells, with particular attention to autoimmune diseases.

Keywords: B cells, Toll-like receptors, TLRs, autoimmunity, autoreactive, tolerance, innate, SLE, Lupus, BAFF, IFN-I

Introduction

The generation of a diverse antibody repertoire occurs in a stochastic fashion and requires checkpoints to either eliminate or tolerize B cells with anti-self specificity 1. Autoreactive B cells that escape these checkpoints have the potential to initiate or contribute to the development of autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) or rheumatoid arthritis 2, 3. In contrast, effective activation and clonal expansion of antigen-specific B cells is required to quickly neutralize and eradicate both viral and bacterial infections.

It is well established that B cell receptor-triggering events regulate both tolerance to self-derived antigens in the bone marrow and periphery, as well as activation in response to foreign antigens 4. Central tolerance mechanisms occur in the bone marrow and involve clonal deletion to eliminate B cells with self-reactive BCRs 5-7. Additionally, receptor editing of autoreactive BCRs via alternative light chain usage can alter B cell-specificity and thus, eliminate self-reactivity 8. In the event that an autoreactive B cell escapes central tolerance in the bone marrow, it is subject to a number of peripheral tolerance mechanisms. First, anergy, or functional unresponsiveness, can prevent peripheral autoreactive B cells from becoming activated and differentiating into plasma cells1. In addition, self-reactive B cells can be deleted from the peripheral lymphocyte pool 9, 10. Mature autoreactive B cells in the germinal center reaction can undergo V(D)J recombination to change otherwise harmful self-specific BCRs 11-14. Antigen-dependent exclusion of autoreactive B cells from follicles also prevents overt self-specific responses 15, 16. Finally, in some cases, fully functional B cells with self-specificity were found to be auto-antigen ignorant 17-19. All of the above mentioned mechanisms are thought to require recognition of the BCR with soluble or membrane-bound self-antigen. However, it is becoming more appreciated that signals from the innate immune system can also help determine the fate of auto-reactive, as well as foreign-antigen-specific B cells 20, 21. Herein, we review the most recent literature describing methods the innate immune system uses to drive as well as dampen B cell responses.

Intrinsic effects of TLR ligands on naïve and memory B cells

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs), which recognize conserved microbial products and activate the innate immune system22. TLR-1, -2, -4 and -5 are expressed on the cell surface and recognize non-nucleic acid components of microbes 23. TLR2, in conjunction with TLR1 or TLR6, recognize lipopeptides while TLR4 and TLR5 recognize bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or flagellin, respectively 24. Other TLRs localize to endocytic compartments such as TLR-3, -7, -8 and -9. These TLRs recognize dsRNA (TLR3), ssRNA(TLR7/8) and CpG-containing DNA(TLR9) 23. Proximal signaling events downstream of all TLRs except TLR3 involve the adaptor molecule myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88 (MyD88) and interleukin-1 receptor associated kinase (IRAK) 24. Distal signaling events lead to interferon regulatory factor (IRF) and/or NFκB-dependent induction of type one interferon (IFN-I) as well as pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, TNF-α, and IL12 22. B cell activation, proliferation, and class-switch recombination are all influenced by the TLR pathways 25-31, but exactly which B cell population is most sensitive and which additional factors are required for full B cell activation are still open questions. Among recent studies focused on this issue, we will summarize, on one side, reports of activation of various B cell populations with TLR ligands, and on the other side, reports of B cell suppressor activity as a consequence of TLR activation.

TLR-mediated activation of B cells

The immune system uses a hierarchy of B cell subtypes to respond to TLR ligands32. Thus, marginal zone B cells respond to a greater extent in response to TLR3 and TLR4 ligands than transitional or follicular B cells with regard to plasma cell differentiation and IgM secretion 32, 33. This is consistent with the characterization of marginal zone B cells being more “innate-like” B cells34. Also, due to the functional differences between naïve and memory B cell subsets, there has been interest in delineating the differential effects of TLR agonists on each. For instance, human memory B cells were shown to have increased levels of CD180, a TLR-related molecule that cooperates with TLR4 to recognize LPS, compared to naïve cells 35. This correlated with increased proliferation of memory B cells in response to CD40L and anti-CD180. Other studies have demonstrated higher protein levels of TLRs on memory versus naïve B cells 36. Resiquimod, a TLR7 agonist, was shown to induce IgM and IgG secretion without T cell help in both naïve and memory human B cells in vitro, but naïve B cells required boosting with IL-2 + IL-10 for an efficient response (Fig. 1) 37. These data indicate that TLR ligands alone may be sufficient to lead to preferential activation of memory B cells and differentiation into IgM and IgG-secreting plasma cells in the absence of T cell help. But the in vitro data on B cell differentiation upon TLR stimulation might not be easily translated to in vivo findings. For example, it was found that TLR4, 7 & 9 ligands could stimulate B cells from NP-immunized mice to secrete high affinity NP-specific IgM and IgG in vitro. Purified NP-specific memory B cells had the greatest capacity to differentiate into high-affinity NP-specific IgG+ cells in response to TLR4 or TLR9 ligands, compared to plasma cells and non-switched NP-specific cells. The situation was very different in vivo, however, as TLR4 and 9 ligands were unable to boost NP-specific antibody titers in the serum of immunized mice [36]. Thus, it appears that the real consequence of activating the TLR pathway in B cells in vivo in the absence of BCR engagement or other co-stimulators is still uncertain.

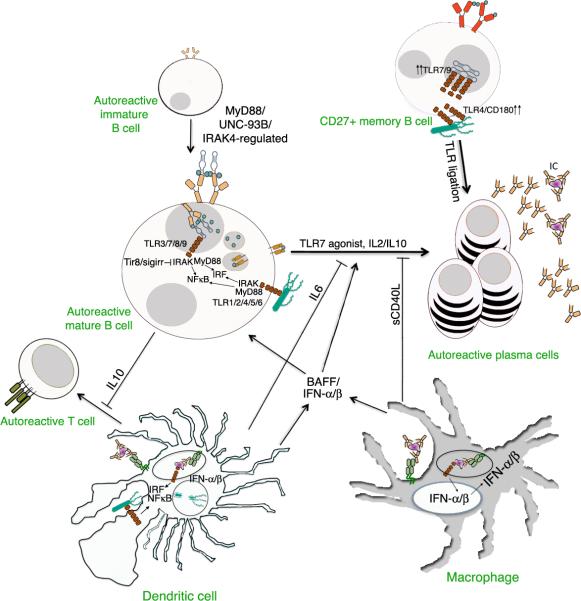

Figure 1. Innate pathways to B cell activation and tolerance.

Intrinsic TLR signaling in naïve and memory B cells can lead to IgM and IgG-secreting plasma cell formation through IRAK and MyD88. Memory B cells express increased levels of TLRs and have a greater capacity to differentiate into plasma cells via TLR stimulation than naïve B cells. TLR-activated B cells can suppress T cell responses indirectly through an IL10-dependent mechanism. Type one IFN production from macrophages and dendritic cells stimulated with immune complexes or TLR agonists can promote the differentiation of B cells into plasma cells. TLR-stimulated dendritic cells and macrophages can suppress autoreactive B cell differentiation into plasma cells through IL6 and sCD40L, respectively. BAFF, produced by APCs, can also influence B cell homeostasis and differentiation into plasma cells. MyD88, UNC-93B and IRAK4 each decrease the level of autoreactive B cells in the periphery.

It is interesting to note that B cells with high affinity autoreactive BCRs are less responsive to ligands for TLR4 and 9, with respect to differentiation into antibody-secreting cells, despite having a higher proliferation index, than B cells with lower affinity autoreactive BCRs 32. This suggests that high affinity autoreactive B cells may be intrinsically programmed to respond poorly to endogenous TLR ligands. The concentration of TLR ligand and duration of stimulation strictly regulate how many cell divisions a B cell will undergo 38. Under optimal stimulation conditions, however, a maximum number of B cell divisions, termed population division destiny, is reached and will not be exceeded 38. Since cell proliferation is tightly linked to plasma cell formation, B cells most likely use this to limit the extent of TLR effects during a normal inflammatory response. Additional mechanisms may exist in B cells to limit TLR signaling. For instance, in HEK293 cells stimulation of TLR2, -4 or -9 leads to downregulation of the critical IL1R/TLR adaptor IRAK4 39, 40. Receptors with regulatory function on TLR signaling such as the inhibitory TIR8/SIGRR could also limit B cell activation. Indeed, TIR8 has been shown to be a factor in maintaining B cell tolerance in vivo 41 as will be discussed below in the section describing mouse models of autoimmune disease.

Since B cell-intrinsic TLR signaling can promote B cell activation, proliferation, and class-switch recombination, its role in the production of pathogenic antibodies in autoimmune diseases is currently being investigated 26, 30. In the AM14 transgenic mouse model, in which B cells are expressing a BCR specific for IgG2a, it was shown that administration of IgG2a anti-chromatin antibodies lead to extrafollicular plasma cell expansion, class-switch recombination, affinity maturation and antibody secretion 42, 43. This process could proceed at least partially in the absence of T cell help and required B cell-intrinsic expression of MyD88, a critical adaptor molecule for TLR signaling. Furthermore, the appearance of antibody-forming cells (AFC's) required the expression of TLR7 and TLR9, as combined deficiency completely eliminated these antigen-specific AFCs 42. These results seem to indicate that chromatin-containing immune complexes activate B cells in vivo by engaging endogenous TLRs and thus induce their differentiation into plasmablasts 29, 42, 44, 45.

Role of TLRs in B cell suppressive functions

New reports suggest that B cell-intrinsic TLR signaling can lead to tolerance in T cell-mediated responses. Using the mouse model of autoimmune disease experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), B cells were shown to play a suppressive role in the recovery phase of disease and they required expression of MyD88 or TLR2/4 46. Furthermore, IL-10 from TLR-activated B cells prevented CpG-stimulated DCs from promoting T cell activation in vitro, thus providing a possible molecular mechanism whereby B cells suppress EAE46, 47. In separate experiments where B cells present the encephalitogenic peptide MOG 35-55 on MHC class II molecules, T cells become tolerized and do not initiate MOG-induced EAE 48. This process did not require IL10 expression. Human B cells have also been reported capable of suppressing T cell responses in certain conditions. It was shown that TLR9-activated human CD25+ B cells could suppress T cell proliferation and IFN-γ production through a contact-dependent mechanism 49. B cells appeared to require IL2 for the suppressive effect, as blocking the IL2R on B cells partially reversed the repression. Thus, these studies indicate that B cells can suppress T cell function through TLR-dependent and independent mechanisms.

Extrinsic effects of innate immune pathways on B cell activation and tolerance

In this section we will discuss how TLR signaling and subsequent innate responses in cell types other than B cells influence the outcome of B cells during infection or autoimmune responses.

Effects of IFN-I on B cells

Dendritic cells (DCs) and macrophages express a variety of TLRs important for microbe recognition 50. Inflammatory cytokines secreted by DCs and macrophages stimulated with TLR ligands can ultimately influence the fate of B cells during normal inflammatory responses or during autoreactive ones 22, 51, 52. For example, IFN-I, secreted at high levels by plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs) upon viral infection or TLR stimulation, increased the expression of TLR7 in naïve B cells 53-55. Others have shown that pDC-derived IFN-I increased the sensitivity of memory B cells to TLR7 ligand-induced plasma cell formation 56. This was limited to TLR7, as TLR3 and TLR9 ligands had little combined effect in the presence of pDCs or IFN-I in inducing plasma cell formation. Additionally, pDCs, versus myeloid DCs (mDCs), were able to support better memory plasma B cell differentiation and proliferation.

Elevated levels of IFN-I and interferon stimulated gene expression have been found in association with human lupus as well as mouse lupus models 57-62. Immune complexes containing DNA antigens can be internalized by pDCs, which leads to the induction of IFN-I 63, 64. This process, downstream of the initiation and expansion of autoreactive B cells, is thought to amplify lupus 65. In the pristane-induced lupus mouse model, IFN-I receptor deficiency eliminated autoantibody production and glomerulonephritis 60. TLR7 expression was also required in this model for IFN-I production as well as the increase in anti-nuclear antibodies 66, 67. Interestingly, FcγRI and FcγRIII, which are required for uptake of IgG-antibody containing immune complexes in pDCs, were dispensable for IFN-I production in response to pristane. Taken together, these results suggest that in addition to being a result of immune complex-mediated stimulation of pDCs, IFN-I may also have effects upstream of the initial break in tolerance against nuclear antigens by B cells. In support of this idea, patients treated with IFN-I for cancer or Hepatitis C viral infection have an increase in circulating anti-nuclear antibodies 68, 69.

Suppressive effects of innate immune cells and cytokines on B cells

TLR-activated macrophages and DCs can also have suppressive effects on autoreactive B cells. In co-culture experiments, LPS-stimulated mDCs and macrophages suppressed the differentiation of autoreactive B cells into antibody-secreting cells 70, 71. The suppressive effect of mDCs and macrophages was dependent on IL-6 and sCD40L secretion, respectively 70, 71. Importantly, the suppressive effects of these soluble factors seem to be limited to chronically activated autoreactive B cells, as naïve B cell differentiation into antibody-secreting cells was unaffected. Follicular B cells were also more sensitive to the inhibitory effects of DCs and macrophages than marginal zone B cells70. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells have also been shown to play a suppressive role in a mouse model of autoimmune arthritis 72. In this model, Th1-polarized T cells specific for OVA were adoptively transferred into BALB/c recipients and one day later challenged with a subcutaneous injection of OVA in complete Freund's adjuvant (CFA). 10 days later, the mice were challenged with a subcutaneous periarticular injection of heat-aggregated OVA into both ankles 73. Inflammatory arthritis was established, characterized by ankle joint swelling, and the breakdown of tolerance to collagen antigens 73. Anti-collagen antibodies are detected in the serum of these animals and increase in the absence of pDCs, indicating a suppressive role on autoreactive B cells. Anti-OVA antibody levels were similar between pDC-depleted and non-depleted animals, suggesting that the suppression may be specific to autoreactive B cells 72.

Effects of BAFF on the fate of B cells

B-cell-activating factor (BAFF) is a member of the tumor-necrosis-factor family and induces B cell proliferation and differentiation both in vitro and in vivo74. BAFF is an essential component of B cell homeostasis, as it is critical for B cell survival and effector function 75, 76. Transgenic overexpression of BAFF results in a severe autoimmune disorder characterized by the production of autoantibodies, proteinuria, splenomegaly, immunoglobulin deposition in kidneys, spontaneous germinal center formation and expanded marginal zone cells 75, 76. Increased serum levels of BAFF have also been detected in patients with SLE 77.

Some phenotypic features seen in BAFF transgenic mice are similar to autoimmune regulator gene (AIRE)-deficient mice 76. Aire-/- mice contain elevated levels of BAFF in their serum and expanded, BAFF-expressing antigen presenting cells, such as dendritic cells, which persist in the absence of T cells 76, 78. Patients with loss-of-function mutations in Aire frequently develop Autoimmune Polyendocrine Syndrome type I 78, 79. Elevated levels of circulating BAFF were detected in these patients, which was shown to be dendritic cell-intrinsic. These results suggest the intriguing possibility that BAFF regulates tolerance in the absence of functional AIRE.

Early activation of B lymphocytes in the target organs of some autoimmune diseases may be the consequence of increased levels of BAFF, secreted by activated innate immune cells80. For instance, viral infections can induce secretion of BAFF in human salivary gland epithelial cells, which are primary targets of Sjögren's syndrome. Viral-induced BAFF upregulation was shown to involve TLRs, IFN-Is, as well as other unidentified factors. This study demonstrates how viral infection could link the innate immune system with BAFF-dependent activation of B cells.

Blockade of BAFF is a promising therapy in several autoimmune diseases. BAFF antagonists have been shown to be effective in the prevention and treatment of the lupus-prone mice 81. Several BAFF antagonists, including soluble forms of the receptor and neutralizing monoclonal antibodies are currently in human clinical trials for SLE treatment 81-83. More experiments are needed to determine the optimal way to neutralize BAFF without compromising adaptive immunity to microbes.

In addition to an inflammatory role for BAFF in promoting B cell activation, it has also been demonstrated to play an anti-inflammatory role by supporting the expansion of T regulatory cells 84. Deregulated BAFF expression alters T cell-dependent alloimmune responses. BAFF transgenic mice with the H-2b haplotype failed to reject transplanted islet allografts from BALB/c donors with the H-2d haplotype. Furthermore, skin allografts were also tolerated in BAFF Transgenic MHC-mismatched recipients. Tolerance was due to BAFF-dependent expansion of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ T regulatory cells (T regs) in the periphery, which suppressed T cell-mediated effector function. Finally, the mechanism of BAFF-mediated expansion of T regs was shown to be B cell-intrinsic 84.

Mouse models of B cell autoimmunity and tolerance

Recently, several mouse models of B-cell associated autoimmune diseases induced by dysregulation of innate immune responses have been described. Using in vivo transgenic expression, it was recently shown that TNF-receptor associated factor 3 (TRAF3) plays a critical role in the control of tolerance and the development of autoimmunity 85. TRAF3 overexpression produced a phenotype similar to SLE, characterized by systemic inflammation and elevated levels of inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, MCP-1, IL-6 and IFNγ. TRAF3 transgenic mice also contained an elevated frequency of plasma cells, correlating with hypergammaglobulinemia and increased serum levels of IgG2a and IgG2b. Transgenic expression of TRAF3 also alters TLR-mediated B-cell differentiation, as LPS or CpG enhanced humoral responses without affecting proliferation, compared to wild type mice.

Another example, which underscores the importance of TLR regulation in the prevention of autoimmune disease, is the mouse deficient in the inhibitory TIR8/SIGIRR receptor. The TLR-related molecule TIR8 negatively regulates TLR and IL-1R signaling through the inhibition of TRAF-6 and IRAK 86-88. Mice deficient in this molecule on the lupus-prone B6lpr/lpr background develop a lymphoproliferative disease characterized by splenomegaly, lymph follicle hyperplasia and the presence of both anti-dsDNA and anti-snRNP antibodies41. In addition to the known role of TIR8 in DCs and epithelial cells, Lech and co-workers demonstrated that B6.lpr/lprTir8-/- B cells are hyperresponsive to ligands for TLRs -4, -7 and -9 compared to B6.lpr/lprTir8+/+41, 86, 89. These data suggest that TIR8 could operate in B cells to restrict the production of anti-nuclear and anti-nucleolar plasmablasts.

A mouse with a hypomorphic allele of the inhibitory protein-tyrosine phosphatase SHP-1 is another example of spontaneous multi-organ autoimmune disease that depends on TLR/IL-1 activity 90. Disease in this new mouse model was shown to be dependent on MyD88, IRAK-4 and the IL-1 receptor, but not on STAT1, suggesting that IFN-I production might not be critical in this case 90.

Innate immune regulation of human B cells and autoantibodies

Recently, B cell depletion therapies have proven effective for the treatment of human autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and lupus91-93. These observations underscore the importance in understanding the genetic and environmental basis for how human B cells contribute to the break in tolerance to self-antigens. As described above, TLR signaling contributes to both B cell activation and tolerance to auto-antigens (e.g., antigens of nuclear origin). But paradoxically, it was recently discovered that patients who have loss-of-function mutations in IRAK4, UNC-93B or MyD88, all of which are molecules critical for TLR signaling, have an emergence of autoreactive B cells in their peripheral blood 94. Using a single-cell BCR cloning and expression system, Isnardi, et al. determined that new emigrant B cells isolated from IRAK4-, MyD88- and UNC-93B-deficient patients contain between a 5-10 fold higher frequency of multi auto-antigen specific B cells than healthy controls. This suggests that IL-1R/TLR signaling events are required early in B cell development to effectively eliminate autoreactive cells. Although the removal of new emigrant B cells specific for anti-nuclear antigens required IRAK4 and MyD88, UNC-93B was dispensable for this process 94. In contrast, all three proteins were required for the removal of multi auto-antigen and nuclear-specific mature naïve B cells in the periphery. Interestingly, despite the elevated frequency of B cells with nuclear specificity in their blood, serum from these patients did not contain anti-nuclear antibodies. This observation is in agreement with mouse studies demonstrating the importance of MyD88 and TLR7 for systemic autoimmunity 28, 95-98. It would be interesting to examine the B cell repertoire of mice deficient for IRAK4 or MyD88 to determine if, similar to humans, they have increased frequencies of B cells with self-specificities. Crossing these mice to various lupus-prone strains would help to elucidate the mechanisms by which these B cells are silenced in the periphery.

Others have recently shown that B cells with anti-nuclear specificity are part of the normal human peripheral repertoire 99. These cells are functionally anergic and phenotypically identical to naïve B cells with the exception of the reduced expression of surface IgM. Anergy in these B cells could be reversed when they were rested overnight in the absence of self-antigen. Autoreactive IgG+ B cells have also been demonstrated in the memory pool of normal individuals 100. It is plausible that perturbations in TLR signaling (such as a viral infection) may give these autoreactive pools of B cells a selective advantage and lead to a break in peripheral tolerance and eventually autoimmunity.

Blockade of TNF-α has proven to be a very effective treatment for patients with rheumatoid arthritis and Crohns disease 101. Recently, however, it was discovered that patients treated with anti-TNF-α have an emergence of anti-dsDNA and anti-nucleosome antibodies in their serum 102, 103. Interestingly, the presence of anti-nucleosome antibodies in the serum of patients treated with TNF-α blockers positively correlated with circulating nucleosomes 104. This suggests that availability of antigen drives de novo production of autoreactive B cells in the presence of the TNF-α-blocking antibody, rather than a change in the inflammatory environment favoring the expansion of low frequency precursor cells. Nucleosomes from late apoptotic cells can also stimulate cytokine release and the upregulation of costimulatory markers in macrophages and DCs, respectively 105. This effect appears to be dependent on high mobility group box protein 1 (HMGB1), contained within the nucleosomes, and TLR2 expression on responding cells. This process, in combination with the TLR9-dependent activation of DCs by chromatin-containing immune complexes, may contribute to the overall amplification of inflammation seen in SLE 29, 63, 64.

Conclusions

B cell fate during an inflammatory response must be tightly regulated by signals from the adaptive and innate immune systems. Balance between activating and inhibitory signals can help prevent overt autoreactive responses while maintaining immunity against harmful infectious agents. We reviewed here the most recent progress in understanding how innate immune signals originating from TLRs control the fate of B cells (Fig. 1). Interestingly, in addition to a role for TLR signaling in promoting humoral immunity and autoimmunity, it seems that under certain conditions TLRs contribute to B cell-mediated suppression of autoreactive responses. These effects appear to be both B cell intrinsic and extrinsic. Understanding the innate mechanisms balancing activation and suppression of B cells will help in strategies for treating autoimmune diseases or for designing better vaccination protocols.

Acknowledgement

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, NIAID.

References

- 1.Goodnow CC, et al. Cellular and genetic mechanisms of self tolerance and autoimmunity. Nature. 2005;435:590–597. doi: 10.1038/nature03724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hostmann A, et al. Peripheral B cell abnormalities and disease activity in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2008;17:1064–1069. doi: 10.1177/0961203308095138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yanaba K, et al. B-lymphocyte contributions to human autoimmune disease. Immunol Rev. 2008;223:284–299. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ding C, Yan J. Regulation of autoreactive B cells: checkpoints and activation. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz) 2007;55:83–89. doi: 10.1007/s00005-007-0011-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nemazee DA, Burki K. Clonal deletion of B lymphocytes in a transgenic mouse bearing anti-MHC class I antibody genes. Nature. 1989;337:562–566. doi: 10.1038/337562a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lang J, et al. B cells are exquisitely sensitive to central tolerance and receptor editing induced by ultralow affinity, membrane-bound antigen. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1685–1697. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.5.1685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hippen KL, et al. In vivo assessment of the relative contributions of deletion, anergy, and editing to B cell self-tolerance. J Immunol. 2005;175:909–916. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.2.909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nemazee D. Receptor editing in B cells. Adv Immunol. 2000;74:89–126. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60909-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kench JA, Russell DM, Nemazee D. Efficient peripheral clonal elimination of B lymphocytes in MRL/lpr mice bearing autoantibody transgenes. J Exp Med. 1998;188:909–917. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.5.909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Russell DM, et al. Peripheral deletion of self-reactive B cells. Nature. 1991;354:308–311. doi: 10.1038/354308a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Han S, et al. V(D)J recombinase activity in a subset of germinal center B lymphocytes. Science. 1997;278:301–305. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5336.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Han S, et al. Neoteny in lymphocytes: Rag1 and Rag2 expression in germinal center B cells. Science. 1996;274:2094–2097. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5295.2094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hikida M, et al. Reexpression of RAG-1 and RAG-2 genes in activated mature mouse B cells. Science. 1996;274:2092–2094. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5295.2092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Papavasiliou F, et al. V(D)J recombination in mature B cells: a mechanism for altering antibody responses. Science. 1997;278:298–301. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5336.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cyster JG, Goodnow CC. Antigen-induced exclusion from follicles and anergy are separate and complementary processes that influence peripheral B cell fate. Immunity. 1995;3:691–701. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90059-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cyster JG, Hartley SB, Goodnow CC. Competition for follicular niches excludes self-reactive cells from the recirculating B-cell repertoire. Nature. 1994;371:389–395. doi: 10.1038/371389a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aplin BD, et al. Tolerance through indifference: autoreactive B cells to the nuclear antigen La show no evidence of tolerance in a transgenic model. J Immunol. 2003;171:5890–5900. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.11.5890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koenig-Marrony S, et al. Natural autoreactive B cells in transgenic mice reproduce an apparent paradox to the clonal tolerance theory. J Immunol. 2001;166:1463–1470. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.3.1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu X, Manser T. Antinuclear antigen B cells that down-regulate surface B cell receptor during development to mature, follicular phenotype do not display features of anergy in vitro. J Immunol. 2005;174:4505–4515. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.8.4505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ehlers M, Ravetch JV. Opposing effects of Toll-like receptor stimulation induce autoimmunity or tolerance. Trends Immunol. 2007;28:74–79. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vilen BJ, Rutan JA. The regulation of autoreactive B cells during innate immune responses. Immunol Res. 2008;41:295–309. doi: 10.1007/s12026-008-8039-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kawai T, Akira S. Toll-like receptor and RIG-I-like receptor signaling. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1143:1–20. doi: 10.1196/annals.1443.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Palm NW, Medzhitov R. Pattern recognition receptors and control of adaptive immunity. Immunol Rev. 2009;227:221–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00731.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Uematsu S, Akira S. Toll-Like receptors (TLRs) and their ligands. Handbook of experimental pharmacology. 2008:1–20. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-72167-3_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jegerlehner A, et al. TLR9 signaling in B cells determines class switch recombination to IgG2a. J Immunol. 2007;178:2415–2420. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.4.2415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pasare C, Medzhitov R. Control of B-cell responses by Toll-like receptors. Nature. 2005;438:364–368. doi: 10.1038/nature04267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Christensen SR, et al. Toll-like receptor 9 controls anti-DNA autoantibody production in murine lupus. J Exp Med. 2005;202:321–331. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ehlers M, et al. TLR9/MyD88 signaling is required for class switching to pathogenic IgG2a and 2b autoantibodies in SLE. J Exp Med. 2006;203:553–561. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leadbetter EA, et al. Chromatin-IgG complexes activate B cells by dual engagement of IgM and Toll-like receptors. Nature. 2002;416:603–607. doi: 10.1038/416603a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McGettrick AF, O'Neill LA. Toll-like receptors: key activators of leucocytes and regulator of haematopoiesis. Br J Haematol. 2007;139:185–193. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06802.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cervantes-Barragan L, et al. TLR2 and TLR4 signaling shapes specific antibody responses to Salmonella typhi antigens. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39:126–135. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Diz R, McCray SK, Clarke SH. B cell receptor affinity and B cell subset identity integrate to define the effectiveness, affinity threshold, and mechanism of anergy. J Immunol. 2008;181:3834–3840. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.6.3834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rubtsov AV, et al. TLR agonists promote marginal zone B cell activation and facilitate T-dependent IgM responses. J Immunol. 2008;180:3882–3888. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.6.3882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bendelac A, Bonneville M, Kearney JF. Autoreactivity by design: innate B and T lymphocytes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2001;1:177–186. doi: 10.1038/35105052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Good KL, Avery DT, Tangye SG. Resting human memory B cells are intrinsically programmed for enhanced survival and responsiveness to diverse stimuli compared to naive B cells. J Immunol. 2009;182:890–901. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.2.890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bernasconi NL, Onai N, Lanzavecchia A. A role for Toll-like receptors in acquired immunity: up-regulation of TLR9 by BCR triggering in naive B cells and constitutive expression in memory B cells. Blood. 2003;101:4500–4504. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-11-3569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Glaum MC, et al. Toll-like receptor 7-induced naive human B-cell differentiation and immunoglobulin production. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123:224–230. e224. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Turner ML, Hawkins ED, Hodgkin PD. Quantitative regulation of B cell division destiny by signal strength. J Immunol. 2008;181:374–382. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.1.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hatao F, et al. Prolonged Toll-like receptor stimulation leads to down-regulation of IRAK-4 protein. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;76:904–908. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0504277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hatao F, et al. MyD88-induced downregulation of IRAK-4 and its structural requirements. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2008;53:260–264. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2008.00425.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lech M, et al. Tir8/Sigirr prevents murine lupus by suppressing the immunostimulatory effects of lupus autoantigens. J Exp Med. 2008;205:1879–1888. doi: 10.1084/jem.20072646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Herlands RA, et al. T cell-independent and toll-like receptor-dependent antigen-driven activation of autoreactive B cells. Immunity. 2008;29:249–260. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Herlands RA, et al. Anti-chromatin antibodies drive in vivo antigen-specific activation and somatic hypermutation of rheumatoid factor B cells at extrafollicular sites. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:3339–3351. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lau CM, et al. RNA-associated autoantigens activate B cells by combined B cell antigen receptor/Toll-like receptor 7 engagement. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1171–1177. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Viglianti GA, et al. Activation of autoreactive B cells by CpG dsDNA. Immunity. 2003;19:837–847. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00323-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lampropoulou V, et al. TLR-activated B cells suppress T cell-mediated autoimmunity. J Immunol. 2008;180:4763–4773. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.7.4763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fillatreau S, et al. B cells regulate autoimmunity by provision of IL-10. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:944–950. doi: 10.1038/ni833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Frommer F, et al. Tolerance without clonal expansion: self-antigen-expressing B cells program self-reactive T cells for future deletion. J Immunol. 2008;181:5748–5759. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.8.5748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tretter T, et al. Induction of CD4+ T-cell anergy and apoptosis by activated human B cells. Blood. 2008;112:4555–4564. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-140087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Akira S, Uematsu S, Takeuchi O. Pathogen recognition and innate immunity. Cell. 2006;124:783–801. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kobayashi M, et al. Toll-like receptor-dependent production of IL-12p40 causes chronic enterocolitis in myeloid cell-specific Stat3-deficient mice. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1297–1308. doi: 10.1172/JCI17085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zipris D, et al. TLR activation synergizes with Kilham rat virus infection to induce diabetes in BBDR rats. J Immunol. 2005;174:131–142. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.1.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bekeredjian-Ding IB, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells control TLR7 sensitivity of naive B cells via type I IFN. J Immunol. 2005;174:4043–4050. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.7.4043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Heil F, et al. Species-specific recognition of single-stranded RNA via toll-like receptor 7 and 8. Science. 2004;303:1526–1529. doi: 10.1126/science.1093620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Diebold SS, et al. Innate antiviral responses by means of TLR7-mediated recognition of single-stranded RNA. Science. 2004;303:1529–1531. doi: 10.1126/science.1093616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Douagi I, et al. Human B cell responses to TLR ligands are differentially modulated by myeloid and plasmacytoid dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2009;182:1991–2001. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hooks JJ, et al. Immune interferon in the circulation of patients with autoimmune disease. N Engl J Med. 1979;301:5–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197907053010102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Baechler EC, et al. Interferon-inducible gene expression signature in peripheral blood cells of patients with severe lupus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:2610–2615. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0337679100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bennett L, et al. Interferon and granulopoiesis signatures in systemic lupus erythematosus blood. J Exp Med. 2003;197:711–723. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nacionales DC, et al. Deficiency of the type I interferon receptor protects mice from experimental lupus. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:3770–3783. doi: 10.1002/art.23023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jorgensen TN, et al. Type I interferon signaling is involved in the spontaneous development of lupus-like disease in B6.Nba2 and (B6.Nba2 × NZW)F(1) mice. Genes Immun. 2007;8:653–662. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6364430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Santiago-Raber ML, et al. Type-I interferon receptor deficiency reduces lupus-like disease in NZB mice. J Exp Med. 2003;197:777–788. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Means TK, et al. Human lupus autoantibody-DNA complexes activate DCs through cooperation of CD32 and TLR9. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:407–417. doi: 10.1172/JCI23025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Means TK, Luster AD. Toll-like receptor activation in the pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1062:242–251. doi: 10.1196/annals.1358.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Monrad S, Kaplan MJ. Dendritic cells and the immunopathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus. Immunol Res. 2007;37:135–145. doi: 10.1007/BF02685895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Savarese E, et al. Requirement of Toll-like receptor 7 for pristane-induced production of autoantibodies and development of murine lupus nephritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:1107–1115. doi: 10.1002/art.23407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lee PY, et al. TLR7-dependent and FcgammaR-independent production of type I interferon in experimental mouse lupus. J Exp Med. 2008;205:2995–3006. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ronnblom LE, Alm GV, Oberg KE. Possible induction of systemic lupus erythematosus by interferon-alpha treatment in a patient with a malignant carcinoid tumour. J Intern Med. 1990;227:207–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.1990.tb00144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Noda K, et al. Induction of antinuclear antibody after interferon therapy in patients with type-C chronic hepatitis: its relation to the efficacy of therapy. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1996;31:716–722. doi: 10.3109/00365529609009156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kilmon MA, et al. Macrophages prevent the differentiation of autoreactive B cells by secreting CD40 ligand and interleukin-6. Blood. 2007;110:1595–1602. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-12-061648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kilmon MA, et al. Low-affinity, Smith antigen-specific B cells are tolerized by dendritic cells and macrophages. J Immunol. 2005;175:37–41. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.1.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jongbloed SL, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells regulate breach of self-tolerance in autoimmune arthritis. J Immunol. 2009;182:963–968. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.2.963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Maffia P, et al. Inducing experimental arthritis and breaking self-tolerance to joint-specific antigens with trackable, ovalbumin-specific T cells. J Immunol. 2004;173:151–156. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.1.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Moore P, et al. BLyS: Member of the Tumor Necrosis Factor Family and B Lymphocyte Stimulator. Science. 1999;285:260. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5425.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mackay F, Browning JL. BAFF: A fundamental survival factor for B cells. Nature Reviews. 2002;2:465. doi: 10.1038/nri844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mackay F, et al. Mice Transgenic for BAFF Develop Lymphocytic Disorders Along with Autoimmune Manifestations. J Exp Med. 1999;190:1697. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.11.1697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Stohl W, et al. B lymphocyte stimulator overexpression in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: Longitudinal observations. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:3475–3486. doi: 10.1002/art.11354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lindh E, et al. AIRE regulates T-cell-independent B-cell responses through BAFF. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:18466–18471. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808205105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Aaltonen J, et al. An autosomal locus causing autoimmune disease: Autoimmune polyglandular disease type I assigned to chromosome. Nat Genet. 1994;8:83–87. doi: 10.1038/ng0994-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ittah M, et al. Viruses induce high expression of BAFF by salivary gland epithelial cells through TLR- and type-I IFN-dependent and - independent pathways. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:1058–1064. doi: 10.1002/eji.200738013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ramanujam M, Davidson A. BAFF blockade for systemic lupus erythematosus: will the promise be fulfilled? Immunol Rev. 2008;223:156–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lin WY, et al. Anti-BR3 antibodies: a new class of B-cell immunotherapy combining cellular depletion and survival blockade. Blood. 2007;110:3959–3967. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-04-088088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Vugmeyster Y, et al. A soluble BAFF antagonist, BR3-Fc, decreases peripheral blood B cells and lymphoid tissue marginal zone and follicular B cells in cynomolgus monkeys. Am J Pathol. 2006;168:476–489. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Walters S, et al. Increased CD4+Foxp3+ T cells in BAFF-transgenic mice suppress T cell effector responses. J Immunol. 2009;182:793–801. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.2.793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zapata JM, et al. Lymphocyte-specific TRAF3-transgenic mice have enhanced humoral responses and develop plasmacytosis, autoimmunity, inflammation, and cancer. Blood. 2008 doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-165456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wald D, et al. SIGIRR, a negative regulator of Toll-like receptor-interleukin 1 receptor signaling. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:920–927. doi: 10.1038/ni968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Liew FY, et al. Negative regulation of toll-like receptor-mediated immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:446–458. doi: 10.1038/nri1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Thomassen E, Renshaw BR, Sims JE. Identification and characterization of SIGIRR, a molecule representing a novel subtype of the IL-1R superfamily. Cytokine. 1999;11:389–399. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1998.0452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Garlanda C, et al. Intestinal inflammation in mice deficient in Tir8, an inhibitory member of the IL-1 receptor family. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:3522–3526. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308680101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Croker BA, et al. Inflammation and autoimmunity caused by a SHP1 mutation depend on IL-1, MyD88, and a microbial trigger. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:15028–15033. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806619105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Manjarrez-Orduno N, Quach TD, Sanz I. B cells and immunological tolerance. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:278–288. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sanz I, Anolik JH, Looney RJ. B cell depletion therapy in autoimmune diseases. Front Biosci. 2007;12:2546–2567. doi: 10.2741/2254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Edwards JC, et al. Efficacy of B-cell-targeted therapy with rituximab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2572–2581. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Isnardi I, et al. IRAK-4- and MyD88-dependent pathways are essential for the removal of developing autoreactive B cells in humans. Immunity. 2008;29:746–757. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Berland R, et al. Toll-like receptor 7-dependent loss of B cell tolerance in pathogenic autoantibody knockin mice. Immunity. 2006;25:429–440. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Christensen SR, et al. Toll-like receptor 7 and TLR9 dictate autoantibody specificity and have opposing inflammatory and regulatory roles in a murine model of lupus. Immunity. 2006;25:417–428. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Pisitkun P, et al. Autoreactive B cell responses to RNA-related antigens due to TLR7 gene duplication. Science. 2006;312:1669–1672. doi: 10.1126/science.1124978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Deane JA, et al. Control of toll-like receptor 7 expression is essential to restrict autoimmunity and dendritic cell proliferation. Immunity. 2007;27:801–810. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Duty JA, et al. Functional anergy in a subpopulation of naive B cells from healthy humans that express autoreactive immunoglobulin receptors. J Exp Med. 2009;206:139–151. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Tiller T, et al. Autoreactivity in human IgG+ memory B cells. Immunity. 2007;26:205–213. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Keating GM, Perry CM. Infliximab: an updated review of its use in Crohn's disease and rheumatoid arthritis. BioDrugs. 2002;16:111–148. doi: 10.2165/00063030-200216020-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.De Rycke L, et al. Infliximab, but not etanercept, induces IgM anti-double-stranded DNA autoantibodies as main antinuclear reactivity: biologic and clinical implications in autoimmune arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:2192–2201. doi: 10.1002/art.21190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.De Rycke L, et al. Antinuclear antibodies following infliximab treatment in patients with rheumatoid arthritis or spondylarthropathy. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:1015–1023. doi: 10.1002/art.10876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Cantaert T, et al. Exposure to nuclear antigens contributes to the induction of humoral autoimmunity during TNF alpha blockade. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008 doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.093724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Urbonaviciute V, et al. Induction of inflammatory and immune responses by HMGB1-nucleosome complexes: implications for the pathogenesis of SLE. J Exp Med. 2008;205:3007–3018. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]