Abstract

An optimal platelet response to injury can be defined as one in which blood loss is restrained and haemostasis is achieved without the penalty of further tissue damage caused by unwarranted vascular occlusion. This brief review considers some of the ways in which thrombus growth and stability can be regulated so that an optimal platelet response can be achieved in vivo. Three related topics are considered. The first focuses on intracellular mechanisms that regulate the early events of platelet activation downstream of G protein coupled receptors for agonists such as thrombin, thromboxane A2 and ADP. The second considers the ways in which signalling events that are dependent on stable contacts between platelets can influence the state of platelet activation and thus affect thrombus growth and stability. The third focuses on the changes that are experienced by platelets as they move from their normal environment in freely-flowing plasma to a very different environment within the growing haemostatic plug, an environment in which the narrowing gaps and junctions between platelets not only facilitate communication, but also increasingly limit both the penetration of plasma and the exodus of platelet-derived bioactive molecules.

Introduction

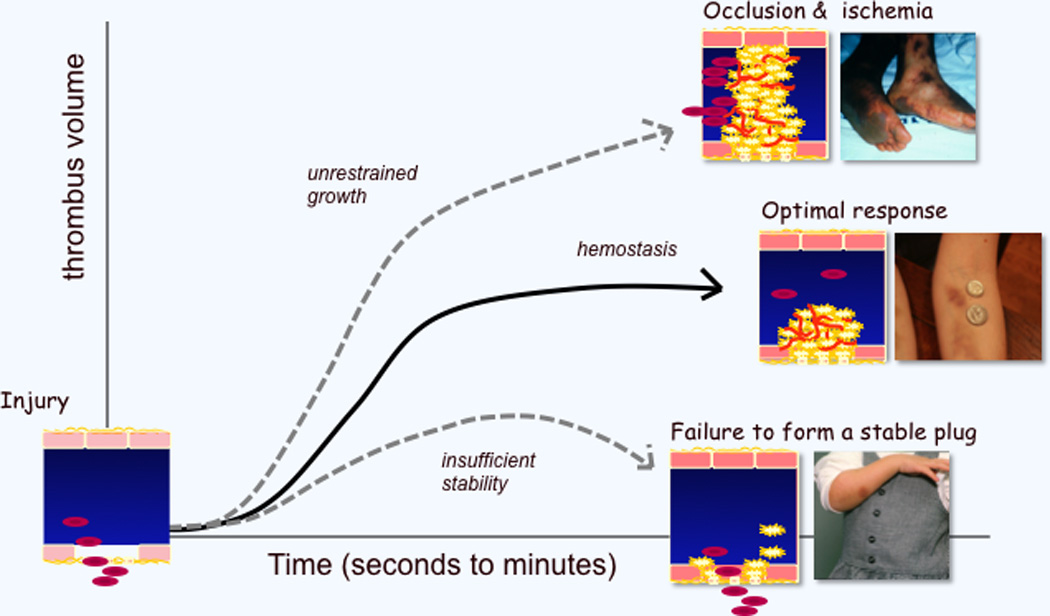

Although fish and birds make do with nucleated thrombocytes as the cellular component of haemostasis, mammals have acquired a substantially more complex means to seal leaks in a high pressure, high flow circulatory system. From a design perspective, circulating platelets must be able to sustain repeated contact with the normal vessel wall without premature activation, recognise the unique features of a damaged wall, cease forward motion, adhere despite the forces produced by continued blood flow, and stick (cohere) to each other, forming a haemostatic plug that can remain in place until it is no longer needed. In this context, an optimal response to injury can be defined as one that prevents further blood loss without causing unwarranted vascular occlusion. In other words, the optimal response normally lies somewhere between too much and too little (Figure 1). By extension the molecular mechanisms that enable an optimal response are those that have been tuned by natural selection to work best under a variety of conditions and in response to a variety of insults. The ability of platelets to respond rapidly to injury is not without cost. In fact, given all that has been learned about the molecular basis of platelet activation, there is greater reason to wonder why platelets cause as little harm as they do than there is to wonder why they ever cause harm at all.

Figure 1. Formation of an optimal platelet plug.

Vascular injury produces a haemostatic response that can be too aggressive (leading to thrombosis), inadequate (leading to further bleeding) or optimal. The examples illustrate (top) vascular occlusion in a man with bacterial sepsis and disseminated intravascular coagulation, (middle) a normal, if imperfect, response to impact in a woman who does martial arts, and (bottom) a weak response to injury in a young girl with Glanzmann’s thrombasthenia (αIIbβ3 deficiency).

This brief review considers some of the ways that an optimal platelet response can be achieved in vivo. It builds upon a very great deal of astonishing work by other investigators, not all of which can be cited in the brief space allotted. Instead, this review is, by intent, a somewhat idiosyncratic exploration of three related ideas about the regulation of thrombus growth and stability that will also be discussed in the accompanying lecture. The first idea considers one of the intracellular mechanisms that regulate the early events of platelet activation downstream of G protein coupled receptors for agonists such as thrombin, thromboxane A2 (TxA2) and ADP. The second considers the ways in which signalling events that are dependent on stable contacts between platelets can influence the state of platelet activation and thus thrombus growth and stability. The third focuses on the changes that are experienced by platelets as they move from their normal environment in freely-flowing plasma to a very different environment within the growing haemostatic plug, an environment in which the narrowing gaps and junctions between platelets increasingly limit both the penetration of plasma molecules and the exodus of platelet-derived bioactive molecules. We will begin with a very brief summary of the events that underlie the platelet contribution to the haemostatic response.

Why do platelets respond at all? A very brief overview of platelet activation

Studies from numerous laboratories have successfully addressed the molecular basis for many of the known events of platelet activation [1–3]. Although there continues to be a steady stream of new insights, the current textbook model describes platelet accumulation after injury as a stepwise sequence of events including: 1) the initial capture, activation and firm adhesion of platelets to the damaged vessel wall; 2) the recruitment of additional platelets to the growing platelet mass via the local generation of soluble platelet agonists and the development of αIIbβ3-dependent contacts between platelets; and 3) stabilisation of the platelet plug to provide continued protection from bleeding until the damaged vessel is repaired. While this description of events is consistent with the majority of research findings, recent improvements in imaging techniques show that the description needs to be refreshed, a point that we will return to in the final section of this review. Keep in mind, however, that this review is more about the mechanisms optimising the platelet response to injury as it is about the mechanisms underlying that response.

At the molecular level, the initial capture and tethering of platelets is mediated by the binding of GPIb-IX-V complex on the platelet surface to the von Willebrand factor (VWF) that decorates the damaged vessel wall, with additional binding to VWF occurring via the major platelet integrin, αIIbβ3 [4, 5]. Once tethered, platelets can be activated by collagen-induced clustering of GPVI, whose role in platelets includes promoting engagement of the integrin α2β1 to collagen, helping platelets form a monolayer to which additional platelets can eventually bind [6, 7]. Platelets are also activated by locally-generated soluble agonists for the G protein coupled receptors on the platelet surface, including those for thrombin, TxA2 and ADP [8]. Activated platelets release ADP from dense granules, generate TxA2 from arachidonate and provide a membrane surface that accelerates local thrombin generation, thus perpetuating a positive feedback loop that reinforces activation of adherent platelets and stimulates platelet recruitment to the haemostatic plug. Additional platelet recruitment is mediated by αIIbβ3, which binds to fibrinogen and other plasma proteins, leading to platelet aggregation by enabling the formation of stable platelet:platelet contacts. GPIbα and αIIbβ3 binding to VWF also contribute to the recruitment of platelets from blood to a growing haemostatic plug [4, 5].

Empiric observation shows that the relative contribution of each of these mechanisms varies according to the cause, severity and even the location of the injury. In humans, the contribution of platelets to haemostasis is different in arteries and veins. In the venous system, low flow rates and stasis permit the accumulation of activated coagulation factors and the local generation of thrombin without the need for prominent contribution from platelets. Venous thrombi contain platelets, but the dominant cellular component consists of trapped erythrocytes. In the arterial circulation, higher flow rates limit fibrin formation by washing out soluble clotting factors. In mouse models, where platelet responses to vascular injury can be observed in detail in real time, collagen and thrombin response pathways within platelets contribute to different extents depending upon whether the injury is produced by the addition of FeCl3, excitation of a soluble dye, the impact of a laser or the application of a mechanical force [9].

Intracellular events

In terms of signal transduction, platelet activation typically begins with the activation of a phospholipase C (PLC) isoform, which by hydrolysing membrane phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) produces the IP3 needed to raise the cytosolic Ca++ concentration, leading to integrin αIIbβ3 activation via a pathway that includes an exchange factor (CalDAG-GEF), a switch (the Ras family member Rap1), an adaptor (RIAM), and proteins that interact directly with the integrin cytosolic domains (kindlin and talin) [10, 11]. Thus, the chain of molecular events linking agonist receptors to at least one of the critical responses of platelets to agonists, fibrinogen binding, can be populated by all or nearly all of the main players [11].

Which isoform of phospholipase C is activated depends on the agonist. Collagen activates PLCγ2 using a mechanism that depends on the formation of a scaffold-based signalling complex and protein tyrosine kinases [12]. Thrombin, ADP and TxA2 activate PLCβ isoforms using Gq as an intermediary that directly couples their respective receptors to the phospholipase [8]. This provides an opportunity to limit as well as promote, platelet activation: the binding of PLCβ to activated Gqα turns on the phospholipase even as it accelerates the hydrolysis of GTP bound to Gqα, limiting the time that the G protein spends in the active state [13].

Signalling downstream of Gq-coupled receptors is necessary, but insufficient for platelet activation. Signalling downstream of Gi family members appears to be equally essential. The two most readily detected Gi family members in platelets are Gi2 and Gz. Knockouts of either in mice produces a platelet defect due to a defect in either ADP responses (the Gi2α knockout) [14, 15] or epinephrine responses (the Gzα knockout) [16]. Gi2 is coupled to the platelet P2Y12 ADP receptors that are the targets of clopidogrel and related drugs [14, 15, 17]. Gz is coupled to platelet α2A-adrenergic receptors [16]. Gi family members in platelets are most frequently associated with suppression of cAMP formation when adenylyl cyclase activity has been increased by PGI2 [14]. Although this is clearly one of their roles, Gi family members also couple receptors to other pathways, including one that activates PI 3-kinase and the serine/threonine kinase, Akt, as well as contributing to Rap1 activation [18, 19]. The experience with P2Y12 antagonists shows that ADP-initiated Gi –dependent signalling is essential for developing and maintaining thrombus stability.

Regulating the earliest events of platelet activation can impose limits on thrombus growth

An important lesson from observing patients with uncommon disorders such as thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and essential thrombocythemia, as well as those with atherosclerosis and sepsis is that platelet activation in the wrong place and at the wrong time can be as much a hazard as having too few platelets. Much of what has been learned about the prevention of inappropriate platelet activation has focused on processes extrinsic to the platelet, especially those that involve the endothelium. A healthy endothelial monolayer provides a physical barrier that limits platelet activation. It also produces inhibitors of platelet activation including NO [20], prostacyclin (PGI2) [21–23] and the surface ecto-ADPase, CD39, which hydrolyses plasma ADP that would otherwise sensitise platelets to activation by other agonists [24].

However, platelet activation is limited by more than just extrinsic forces. This section considers one mechanism by which this is accomplished. As already noted, most of the agonists, which extend the platelet plug do so via G protein coupled receptors. The properties of these receptors make them particularly well-suited for this task. Most G protein coupled receptors bind their ligands with high affinity and, because they act as exchange factors, each occupied receptor can theoretically activate multiple G proteins. This allows amplification of a signal that might begin with a relatively small number of receptors. Because mechanisms exist that can limit the activation of G protein coupled receptors, platelet activation can be tightly regulated even at its earliest stages. Based largely on work in cells other than platelets, those regulatory mechanisms likely include receptor internalisation, receptor phosphorylation, the binding of cytoplasmic molecules such as arrestin family members and the limits on signal duration imposed by RGS (regulator of G protein signalling) proteins. The impact of RGS proteins in platelets is just beginning to be explored. These are proteins that in cells other than platelets have been shown to limit signalling intensity and duration by accelerating the hydrolysis of GTP by activated G protein α subunits [25]. Our recent studies show that they play a similar role in platelets.

RGS proteins as regulators of platelet signalling

Once turned on, heterotrimeric G proteins remain in an active state until hydrolysis of Gα-bound GTP restores the resting state. The rate of hydrolysis is an intrinsic property of the α subunit, but it can be greatly accelerated by the binding to the activated α-subunit of a member of the RGS family. The RGS family in mammals consists of at least 37 members defined by a conserved 130kDa RGS domain [26]. As many as 10 RGS proteins have been identified in platelets at the RNA level, but only two, RGS10 and RGS18, have been detected at the protein level [27–32], a result that we have confirmed.

In a recent project, we asked whether the RGS proteins in platelet might play an essential role in limiting the extent of platelet accumulation once injury has occurred [33]. Given the uncertainty about the full repertoire of RGS proteins that are expressed in human and mouse platelets, we chose a strategy in which a single amino acid substitution in Gi2α blocks interactions with RGS proteins as a class and, therefore, renders Gi2α-GTP RGS-resistant. This would not be expected to affect the relatively slower intrinsic rate of hydrolysis by the α subunit, but would be expected to block the accelerated turn-off caused by RGS proteins. The G184S substitution that blocks Gi2α/RGS interactions had previously been characterised and developed as a mouse line by our collaborator, Richard Neubig [34]. Similar substitutions have been identified in other G proteins, including Gq and Go [35].

The results show that even one copy of the RGS-resistant Gi2α allele is sufficient to enhance platelet aggregation in vitro, shifting the dose/response curves to the left (i.e. lower concentrations) for ADP, thrombin and TxA2. The RGS-resistant Gi2α allele also increases platelet accumulation following laser injury to arterioles within the mouse cremaster circulation [33]. This increase was evident in mice expressing the Gi2α(G184S) allele globally, but it was also present when expression was limited to haematopoietic cells. At the molecular level, the Gi2α(G184S) allele caused an attenuated rise in cAMP levels in response to PGI2 and a substantial increase in basal Akt activation, two events that occur downstream of Gi2 in platelets. In contrast, agonist-stimulated increases in [Ca++]I and Rap1 activation were unaffected, indicating no crossover into Gqα-dependent signalling pathways. Taken together, these results show that removing the restraining hand of RGS proteins on Gi2 in platelets is sufficient to produce a pronounced gain of function, arguing that the normal role of the RGS proteins is to limit platelet activation.

Quis custodiet ipsos custodes? Who will guard the guardians?

Considering the regulatory role of RGS proteins during platelet activation, a reasonable question is whether feedback through RGS proteins is coordinated, allowing signalling to begin before it is constrained. We have recently determined that human and mouse platelets express spinophilin (SPL), a 130 kDa scaffold protein originally identified in screens for proteins that can bind to the serine/threonine phosphatase, PP1 [36], and F-actin [37]. In cells other than platelets, spinophilin has been shown to bind a subset of G protein coupled receptors [38–40] and RGS proteins [40–43]. A spinophilin binding site on the receptors has been mapped to the third intracellular loop, where it competes with arrestin family members, molecules that normally participate in receptor desensitisation and internalisation as well as signalling [43, 44]. In resting platelets, we have determined that spinophilin can bind RGS proteins such as RGS10 and RGS18, forming a ternary complex with the protein tyrosine phosphatase, SHP-1. Platelet activation by thrombin or TxA2 analogues activates spinophilin-bound SHP-1, triggering dissociation of the SPL/RGS complex. Furthermore, results obtained in spinophilin knockout mice suggest that when spinophilin sequesters RGS proteins in resting platelets, it allows platelet activation to begin, while decay of the complex helps to terminate signalling [45]. Although this example focuses on Gqα-dependent signalling, it suggests that RGS proteins themselves are subjected to regulation so that platelet activation can begin before it is limited.

Contact-dependent signalling affects thrombus growth and stability

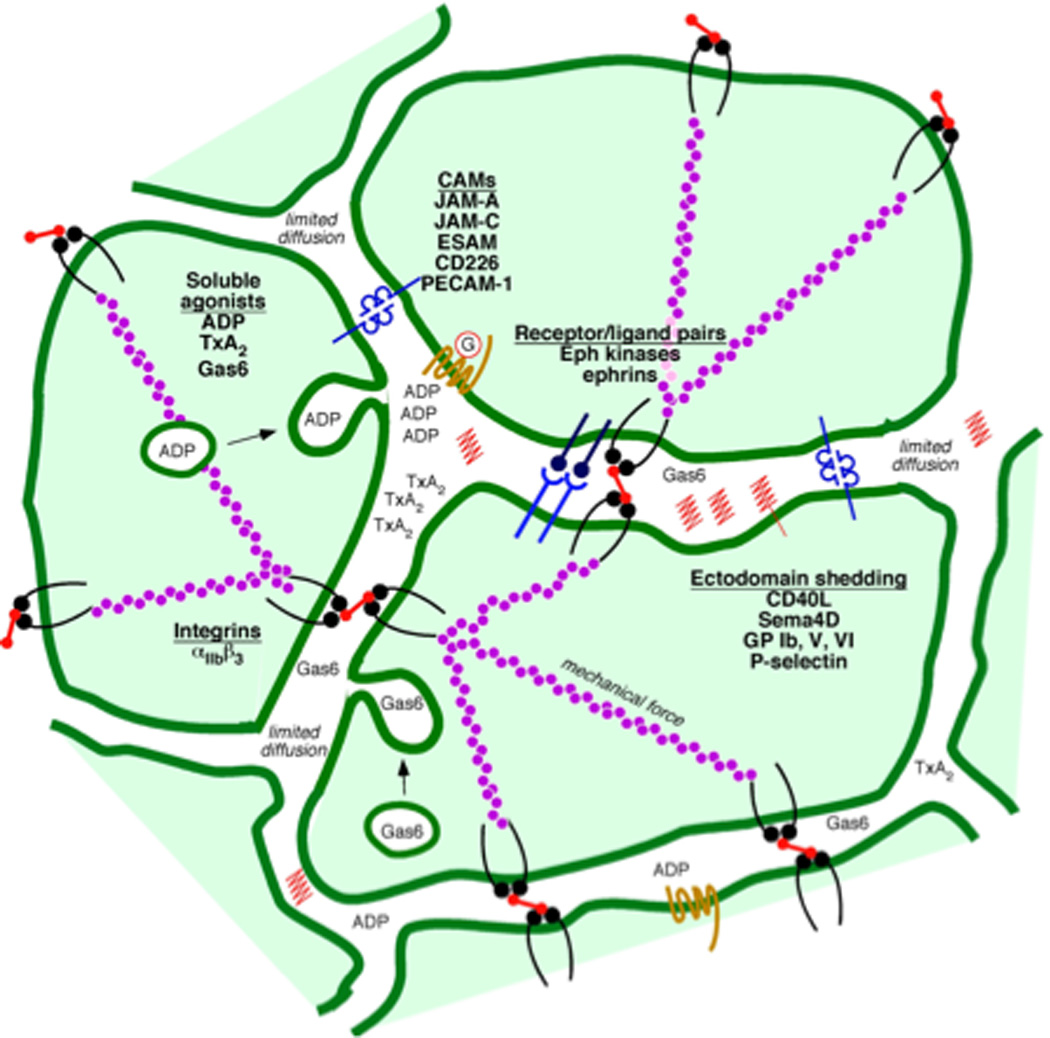

As platelet activation in response to injury proceeds, previously-mobile platelets come into increasingly stable contact with each other, eventually with sufficient stability and proximity that molecules on the surface of one platelet can interact directly with molecules on the surface of adjacent platelets (Figure 2) [1]. This process is dependent on the engagement of αIIbβ3 with one of its ligands, after which inward-directed (i.e. outside-in) signalling occurs through the integrin and through other molecules that can then engage with their counterparts in trans. Outside-in signalling by integrins has been reviewed extensively by others [3, 46, 47]. Here we will focus on the progress made in identifying other contact-dependent interactions that can serve to promote or diminish the state of platelet activation, helping to achieve an optimal response to injury. Some of these are primarily signal-generating events. Others may serve primarily to help form a type of junction between platelets.

Figure 2. Contact-dependent events.

The haemostatic response to injury brings platelets into sufficiently close contact with each other that molecules on the surface of adjacent platelets can interact with each. Examples shown in the figure include ligand/receptor pairs such as ephrinB1 and sema4D and their respective receptors. Cell adhesion molecules include αIIbβ3 integrin, several members of the CTX family (ESAM, JAM-A, JAM-C and CD226), PECAM-1 and CEACAM1. Except for the integrin, which binds to adhesive proteins such as fibrinogen, these molecules interact without the benefit of an intermediary. The space between platelets also provides a protected environment in which soluble agonists (ADP, TxA2 and others), proteins secreted from α-granules (including Gas-6), and the proteolytically-shed exodomains of platelet surface proteins such as sema4D can accumulate.

Receptor/ligand pairs: ephrins and Eph kinases

One example of a contact-dependent receptor/ligand pair are the Eph receptor tyrosine kinases and their ephrin ligands. Ephrins are cell surface molecules attached by either a GPI anchor (ephrin A family members) or a single transmembrane domain (ephrin B family members). Human platelets express at least two Eph kinases, EphA4 and EphB1, as well as their ligand, ephrinB1 [48]. Forced clustering of either EphA4 or ephrinB1 results in cytoskeletal changes leading to platelet spreading, as well as to increased adhesion to fibrinogen, Rap1B activation and granule secretion [48, 49]. EphA4 was found to interact with αIIbβ3 and the Eph/ephrin interaction was found to promote phosphorylation of the β3 cytoplasmic tail. Consistent with these findings, blockade of Eph/ephrin interactions in vitro impaired clot retraction and caused platelet disaggregation at low agonist concentrations without affecting fibrinogen binding, resulting in impaired thrombus growth [48, 50]. These observations suggest that close contact between platelets during the early stages of thrombus formation allows the binding of ephinB1 to EphA4 and EphB1 in trans to provide signalling for sustained integrin activation. The best evidence to date for biologically-meaningful interactions between ephrins and Eph kinases in human platelets comes from flow chamber studies showing diminished platelet accumulation on collagen when Eph/ephrin interactions were blocked [48, 50]. These molecules may not have a similar role in mouse platelets since our efforts to date to establish that mouse platelets express either ephrins or Eph kinases have been negative.

Receptor/ligand pairs: sema4D and its receptors

Semaphorin 4D (Sema4D, CD100) provides another example of a ligand that is involved in contact-dependent signalling in platelets. Like the ephrins, semaphorins are best known for their role in the developing nervous system [51], but they have also been implicated in organogenesis, vascularisation and immune cell regulation [52]. The 25 members of the semaphorin family are defined by a 500 amino acid sema domain [53] and divided into 8 classes. Semaphorins can either be secreted (Class 2, 3 and 8) or bound to the plasma membrane via a transmembrane domain (Class 1, 4, 5 and 6) or a GPI anchor (Class 7) [54]. Sema4D is expressed on the surface of both mouse and human platelets. Sema4D(−/−) mouse platelets have a defect in their responses to collagen and convulxin in vitro, and a reduced response to vascular injury in vivo [55]. Responses to thrombin, ADP and TxA2 mimetics are normal [55, 56].

Since Sema4D(−/−) platelets have a selective defect in collagen-induced aggregation, we have focused our studies on events downstream of the principal collagen receptor, GPVI. Signalling in this pathway has been mapped in considerable detail by others. Clustering of GPVI triggers phosphorylation of the cytoplasmic domains of the GPVI co-receptor, FcRγ, by Src family kinases. This is followed by the binding of the tyrosine kinase, Syk, to phosphorylated FcRγ, activation of Syk, formation of a signalling complex involving SLP-76 and LAT, and activation of PLCγ2 [12]. In comparing sema4D(−/−) platelets with matched controls, we found impaired signalling downstream of Syk in the absence of sema4D, while events upstream of Syk, including tyrosine phosphorylation of FcRγ and the binding of Syk to phospho-FcRγ, occurred normally [55, 56]. Notably, these differences were observed in Sema4D(−/−) platelets only when platelets were allowed to come in contact with each other. Blocking aggregation in wild type platelets reduced Syk phosphorylation to the same level as seen in the sema4D(−/−) platelets and introducing soluble recombinant sema4D exodomain reversed the defect in the sema4D(−/−) platelets. Our current model is that sema4D is a major component of contact-dependent reinforcement of Syk activation downstream of GPVI stimulation. Consistent with this model, the defects observed in sema4D(−/−) platelets can be overcome by adding soluble recombinant sema4D extracellular domain [56].

Thus, there is strong evidence that sema4D provides a contact-dependent boost in collagen-signalling. The platelets that are most likely to be activated via the GP VI signalling pathway are those in the initial monolayer that accumulates on exposed collagen. If so, then it is the sema4D expressed on what will become the second layer of platelets which may be the most relevant since it is the second layer of platelets that will be in the greatest contact with the initial layer. Sema4D is not limited to platelets, but can also be found on T-cells. Work completed well before we began our own studies in platelets showed that sema4D (or CD100) on T-cells binds to CD72 on the surface of B-cells, allowing a type of contact-dependent signalling that is critical for the development of some B-cell subtypes [57]. In the central nervous system, sema4D binds Plexin B1 and B2, respectively [58, 59]. Plexin B1 is also a sema4D receptor on endothelial cells [60]. There are 9 plexin family members, which collectively serve as the major receptor family for semaphorins [58]. While human platelets appear to express CD72, plexin B1 and plexin B2, it is not yet clear what their relative contributions are to sema4D signalling [55]. Mouse platelets do not have detectable CD72 and the CD72 knockout has not, to date, shown us a platelet phenotype.

Sema4D, plexinB1 and plexinB2 are not the only members of these two families that are expressed on human platelets. Using a proteomics approach, Lewandrowski et al. detected 5 plexin family members (A3, A4, B2, B3 and C1) and neuropilin-2, a plexin co-receptor for sema3 family members [61]. An interesting aspect of sema4D biology is that it is cleaved and shed from the surface of activated T-cells and platelets, producing a single large bioactive fragment that contains (based on size) essentially the entire extracellular domain. In a proteomics screen performed to identify other membrane proteins that are shed from activated platelets, we have detected sema4B and sema7A in human platelets [62]. Human platelet mRNAs for neuropilin-1 and plexins A1, A2 and A3 have also been described [63], as have transcripts for sema3A, 3C, 4A and 6C in human cord blood megakaryocytes [64]. Although the expression of these proteins needs to be confirmed by additional methods, it is of significant interest that there is some evidence of multiple members of a receptor/ligand family in platelets. Whether or not the additional semaphorins are involved in contact-dependent signalling as we have found with sema4D, remains to be seen.

Adhesion/junction receptors contribute to contact-dependent signalling

In addition to amplifying platelet activation, contact-dependent signalling can also help to limit thrombus growth and stability. Current examples include, PECAM-1, CEACAM1 and members of the CTX family of adhesion molecules. Knockouts of each of these in mice produce a gain of function phenotype. Platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (PECAM-1) is a type-1 transmembrane protein with 6 extracellular domains, the most distal of which can form homophilic interactions in trans [65]. The cytoplasmic domain contains an immunoreceptor tyrosine inhibitory motif (ITIM) that can bind the tyrosine phosphatase, SHP-2 [66]. PECAM1-deficient platelets exhibit enhanced responses to collagen in vitro and in vivo, consistent with a model in PECAM-1 localises SHP-2 to its substrates, including the GPVI signalling complex, thus providing a brake and preventing excessive platelet activation and thrombus growth [67–69].

Carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 1 (CEACAM1) is a second ITIM family member expressed on the platelet surface that can form homophilic and heterophilic interactions with other CEACAM superfamily members. In contrast to PECAM-1, the CEACAM1 ITIM domain prefers SHP-1 to SHP-2, although either can become bound [70, 71]. The CEACAM1 knockout, like the PECAM-1 knockout produces a gain of function, showing increased platelet activation in vitro in response to collagen and increased thrombus formation in a FeCl3 injury model [72]. Thus, at least on the basis of the knockout results, CEACAM1 also appears to be a negative regulator of GPVI signalling. Still lacking is spatial information that would explain how molecules that (in theory) should cluster at sites of platelet:platelet contact can impact events downstream of receptors that should be most relevant at sites of interaction with the vessel wall. This same issue arises with sema4D as well as PECAM-1 and CEACAM1.

Additional platelet surface proteins that form interactions across platelet:platelet contacts include at least two of the four members of the CTX family that are expressed by platelets: endothelial cell specific adhesion molecule (ESAM) and junctional adhesion molecule-A (JAM-A). Platelets also express JAM-C and CD226. Each of these proteins is a member of the immunoglobulin domain superfamily, with 2 extracellular Ig-like domains, a single transmembrane region and a cytoplasmic tail of varying length that terminates in a binding site for PDZ domain-containing proteins. Studies from our laboratory have shown that ESAM is associated with α-granules in resting platelets and then localises to the junctions between platelets during platelet activation [73]. ESAM(−/−) platelets exhibit increased aggregation in response to low doses of GPCR agonists and are more resistant to disaggregation compared to wild type platelets. In contrast, ESAM(−/−) platelets were indistinguishable from wild type platelets in assays examining individual platelets including calcium mobilisation, activation of αIIbβ3 and single platelet spreading on immobilised fibrinogen [73]. This lack of a phenotype in the absence of platelet:platelet contacts is reminiscent of our findings involving Sema4D [56] and further suggests a role of ESAM in regulating platelet function through contact-dependent events. In vivo, ESAM(−/−) mice form larger and more stable thrombi compared to their wild type counterparts [73]. Collectively, these studies suggest that ESAM negatively regulates platelet function through contact-dependent homophilic interactions although the mechanistic basis for these observations remains to be identified. JAM-A(−/−) mice also exhibit a gain of function phenotype [74]. In addition to forming homophilic interactions, JAM-A, as well as JAM-C, can bind integrins (αLβ2 and αMβ2 respectively) and may be involved in the migration of leukocytes across the endothelium [75, 76].

Heterogeneity and porosity of the growing thrombus

As in vivo imaging technologies have improved, so has the evidence that the haemostatic plug more closely approximates a heterogeneous layer cake than a homogeneous blob of putty. The idea of heterogeneity when applied to platelets can have a number of meanings that are relevant to a discussion of thrombus growth and stability. It can refer to 1) intrinsic heterogeneity among platelets with respect to age, abundance of intracellular signalling molecules and surface expression of critical receptors and adhesion molecules, 2) geographic heterogeneity in the location of platelets with respect to the vessel wall, the surface of the thrombus and the activation state of neighbouring platelets, 3) functional heterogeneity with respect to the activation state of any particular platelet, and 4) heterogeneity in both the access of plasma-borne molecules to different regions of the mass and differences in the ability of platelet-derived molecules to disperse within and exit the mass, properties that reflect in part the net porosity of the growing haemostatic mass. It is the last three of these aspects of heterogeneity that we would like to close by considering.

Thrombus heterogeneity

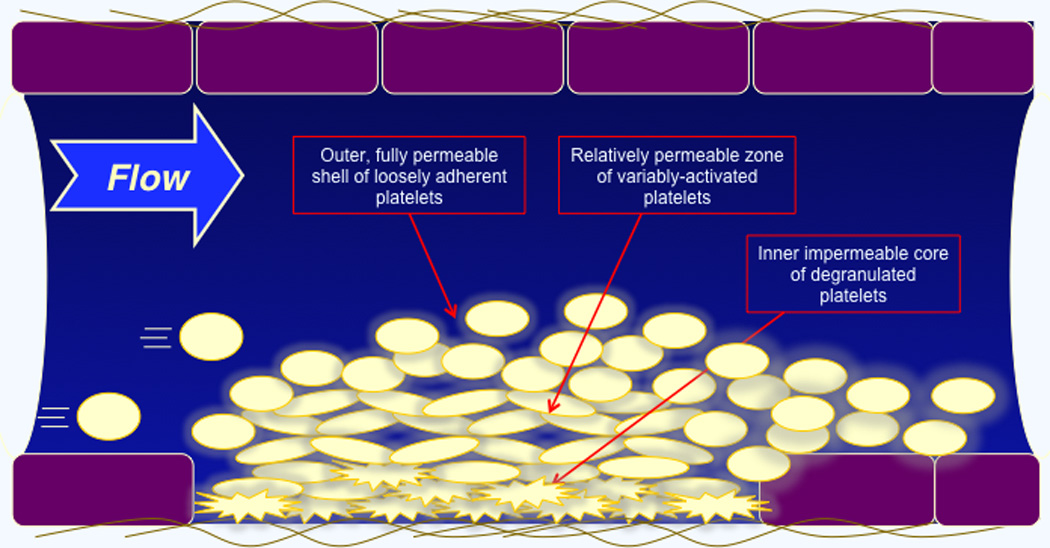

A variety of experimental approaches show that platelet activation within a developing thrombus is not uniform in either time or space [77–82]. Intravital microscopy studies show that platelets maintain their resting discoid morphology when they initially adhere to a developing thrombus, suggesting minimal activation is required for platelet recruitment [79, 83]. Subsequently, individual platelets appear to have two possible two fates: they either adhere transiently and subsequently detach or they become stably adherent to the growing platelet mass. The accumulation of stably adherent platelets occurs in a spatio-temporally restricted pattern, resulting in the formation of a thrombus core that is covered by multiple layers of loosely adherent platelets during the early stages of thrombus formation (Figure 3). Platelets in the inner core tend to have undergone α-granule exocytosis, as reflected by the appearance on their surface of the α-granule membrane protein, P-selectin, while those on the outside have not, at least initially [82, 84].

Figure 3. Heterogeneity and porosity.

Real time live imaging studies performed in mouse models show that the growing haemostatic plug consists of heterogeneous layers in which there is an outer zone of loosely adherent, discoid platelets overlying a zone of activated platelets that have not undergone granule exocytosis. Closest to the wall in this example is a zone of tightly-packed, fully activated and degranulated platelets. Studies that we have performed using fluorescently-tagged dextran molecules of various sizes indicates that the porosity of these zones is greatest in the outermost layer and least in the thrombus core.

These observations prompt a number of questions: What degree of platelet activation is actually necessary for initial platelet recruitment into the growing haemostatic plug (if activation is necessary at all)? What determines whether a tethered platelet becomes stably incorporated into a thrombus? Why does platelet recruitment and therefore overall thrombus growth stop when it reaches a certain point? A recent study by Nesbitt, et al. demonstrated that heterogeneous local shear conditions can contribute to platelet recruitment [83]. Presumably local concentrations of soluble agonists including ADP, TxA2 and thrombin do so as well. The extent to which these molecules can accumulate at concentrations sufficient to activate additional platelets reflects the net of the rate at which they are produced and/or released by platelets and the rate at which they are either washed out, hydrolysed or inactivated by plasma-borne inhibitors. During the early stages of thrombus development, the flow of plasma around individual platelets is relatively unobstructed, but as time passes, this is increasingly not the case, especially in the thrombus core - a point to which we will return shortly. It is reasonable to expect that the rate of conversion of transiently-adherent, discoid platelets on the surface of the growing haemostatic mass, to stably-adherent, fully-activated platelets within the thrombus core is influenced by contact-dependent signalling events (such as those discussed earlier in this review), by externally-derived regulators such as PGI2 and NO and by internal regulators within platelets that promote or limit the duration of signalling.

Heterogeneity has many aspects. Even a generally-applicable concept such as contact-dependent signalling may operate differently in different parts of the thrombus. As one example, consider the CTX family member, ESAM, which, as already noted, is present only in the α-granule membranes of resting platelets [73, 85]. Granule exocytosis allows ESAM to migrate to the junctions between similarly-activated platelets, but as already noted, P-selectin staining shows that only the platelets in the thrombus core have undergone granule exocytosis. By implication, only those platelets will be able to employ ESAM in this manner. Since the ESAM knockout is a gain of function, this late engagement of ESAM my serve to limit, rather than promote, extension of the thrombus core, while having less of an effect in the outer zones of the thrombus.

As a second example, consider the signalling events that occur when sema4D on the surface of platelets engages with its receptors on nearby platelets. This engagement reinforces activation of Syk downstream of GPVI [86] and is, therefore, perhaps most relevant in the “bottom” layer of platelets, the layer which is actually in contact with collagen. Sema4D is present on the surface of resting platelets, but the density of sema4D expression initially increases when platelets are activated and then decreases as sema4D (along with many other proteins on the platelet surface) is shed following cleavage by the metalloprotease, ADAM17 [55, 62]. Thus, a somewhat confusing aspect of contact-dependent signalling, its capacity to both amplify and limit platelet activation, can be resolved by incorporating the idea that different events are relevant to different regions within the haemostatic plug and, potentially, to different time points, reflecting heterogeneity in both space and time.

Thrombus porosity

The haemostatic plug that forms in response to vascular injury is less a solid block than a permeable maze whose properties vary over space and time. The term “porosity” as used here reflects the ability of soluble molecules to move freely within the gaps between adjacent activated platelets. During the early stages of thrombus development, the flow of plasma-borne molecules around individual platelets is relatively unobstructed, but as time passes, this is increasingly no longer the case, partly because as the haemostatic plug matures, platelets within the thrombus core consolidate to form a tightly packed mass [87–89]. This increasingly tight packing reduces the gaps between platelets (i.e. pores), and thus the porosity of the thrombus in the region of the core [82].

The size of the gaps between platelets can be explored by a number of different approaches, each with its own strengths and weaknesses. Static images produced by electron microscopy have the virtue of high resolution, but are limited by their static nature and by the potential impact of specimen preparation. Live imaging in vivo lacks the resolution of electron microscopy, but allows time-dependent changes to be observed in the setting (the vasculature) in which the haemostatic response normally occurs. We are currently using fluorescently-tagged albumin and dextran molecules of various sizes to probe the permeability of pre-existing thrombi in vivo, measuring with real time confocal microscopy the passage of the tagged molecules through haemostatic plugs formed following laser injury. Those studies show that porosity varies not only over time, but also regionally within the thrombus. Porosity is at its greatest in the outer regions of the haemostatic plug where platelets that have not activated sufficiently to change shape can be seen rolling, transiently tethering and then adhering to the platelets that arrived previously. Porosity is least at the thrombus core where platelets have undergone α-granule exocytosis [82].

As thrombus porosity determines the extent to which plasma and its constituents, as well as platelet-derived soluble molecules, flow into and out of the inner regions of a thrombus, this decrease in thrombus porosity is likely to impact thrombus formation and stability via a number of potential mechanisms. These mechanisms include decreased haemodynamic shear forces experienced by individual platelets, decreased access of plasma proteins such as pro- and anti-coagulant factors to the inner regions of the thrombus, increased local concentration of bioactive molecules secreted or shed from platelets, and promotion of contact-dependent signalling between adjacent platelets that reinforces platelet activation. The width of the gaps between platelets is likely to reflect opposing forces. On the one hand, fluid flow and electrostatic repulsion (sialic acid residues on GPIb give the platelet surface a net negative charge) tend to push platelets apart. Adhesive interactions mediated by αIIbβ3 hold platelets together, especially once the actin/myosin filaments within platelets that anchor the cytoplasmic domain of β3 contract.

Although αIIbβ3 is the best-described source of adhesive interactions between platelets, it is not the only one. Close platelet:platelet contacts are likely to be the regions where surface molecules such as ESAM, JAM-A, sema4D and ephrinB1 accumulate and bind to their partners in trans. This has clearly been shown for ESAM [73]; it is reasonable, but speculative to propose that the other molecules discussed in this review do so as well. Platelet:platelet contacts may not resemble the junctions that form between endothelial cells, but they have the potential to restrict the flow of molecules, especially large molecules within the haemostatic plug.

Thus, these observations about porosity are relevant not only for the haemostatic response to injury, but also to the eventual resolution of the thrombus, entry of therapeutic agents and the exodus of bioactive molecules released from their storage sites within platelets. One interpretation of the studies using markers such as anti-P-selectin is that α-granule exocytosis is limited to the inner regions of the thrombus. There is no corresponding measure of dense granule exocytosis, but if it is similar, then the ADP released by platelets is confined to the inner regions, along with all of the prothrombotic, pro-angiogenic and healing-promoting proteins that emerge from α-granules. In the case of platelet activators such as ADP, this may prove an advantage. They have a greater chance of accumulating and reaching critical concentrations within the protected zones of the inner thrombus core. On the other hand, bioactive proteins whose targets include cells other than platelets, such as shed sema4D, may be trapped.

Conclusion

In summary, we have used this brief state of the art review to explore three related concepts that affect thrombus growth and stability starting with new evidence of complex regulation of G protein dependent signalling in platelets, continuing with recent examples of events that can promote or restrict platelet activation once activated platelets come into stable contact with each other, and finishing with the impact of thrombus heterogeneity and porosity. This is clearly a work in progress. Additional studies are needed to answer the questions that are raised by these observations and to determine whether a better understanding of these mechanisms will lead to new therapeutic options.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge support for these studies from the NIH Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (LFB) and the American Heart Association (KMW and TJS).

References

- 1.Brass LF, Zhu L, Stalker TJ. Minding the gaps to promote thrombus growth and stability. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:3385–3392. doi: 10.1172/JCI26869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brass LF, Stalker TJ, Zhu L, Woulfe DS. Signal transduction during initiation, extension and perpetuation of platelet plug formation. In: Michelson AD, editor. Platelets. 2nd edn. Academic Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stegner D, Nieswandt B. Platelet receptor signaling in thrombus formation. J Mol Med. 2011;89:109–121. doi: 10.1007/s00109-010-0691-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hantgan RR, Nichols WL, Ruggeri ZM. von Willebrand factor competes with fibrin for occupancy of GPIIb:IIIa on thrombin-stimulated platelets. Blood. 1990;75:889–894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hantgan RR, Hindriks G, Taylor RG, Sixma JJ, de Groot PG. Glycoprotein Ib, von Willebrand factor, and glycoprotein IIb:IIIa are all involved in platelet adhesion to fibrin in flowing whole blood. Blood. 1990;76:345–353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen H, Locke D, Liu Y, Liu CD, Kahn ML. The platelet receptor GPVI mediates both adhesion and signaling responses to collagen in a receptor density-dependent fashion. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:3011–3019. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109714200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clemetson JM, Polgar J, Magnenat E, Wells TNC, Clemetson KJ. The platelet collagen receptor glycoprotein VI is a member of the immunoglobulin superfamily closely related to FcalphaR and the natural killer receptors. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:29019–29024. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.41.29019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brass LF, Stalker TJ, Zhu L, Woulfe D. Signal transduction during platelet plug formation. In: Michelson A, editor. Platelets. 2nd edn. San Diego: Academic Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Denis CV, Dubois C, Brass LF, Heemskerk JM, Lenting PJ. Towards standardization of in vivo thrombosis studies in mice. J Thromb Haemost. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04350.x. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee HS, Lim CJ, Puzon-McLaughlin W, Shattil SJ, Ginsberg MH. RIAM activates integrins by linking talin to ras GTPase membrane-targeting sequences. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:5119–5127. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807117200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shattil SJ, Kim C, Ginsberg MH. The final steps of integrin activation: the end game. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:288–300. doi: 10.1038/nrm2871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Watson SP, Auger JM, McCarty OJ, Pearce AC. GPVI and integrin alphaIIb beta3 signaling in platelets. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3:1752–1762. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Waldo GL, Ricks TK, Hicks SN, Cheever ML, Kawano T, Tsuboi K, Wang X, Montell C, Kozasa T, Sondek J, Harden TK. Kinetic scaffolding mediated by a phospholipase C-beta and Gq signaling complex. Science. 2010;330:974–980. doi: 10.1126/science.1193438. science. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang J, Wu J, Jiang H, Mortensen R, Austin S, Manning DR, Woulfe D, Brass LF. Signaling through Gi family members in platelets - Redundancy and specificity in the regulation of adenylyl cyclase and other effectors. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:46035–46042. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208519200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jantzen HM, Milstone DS, Gousset L, Conley PB, Mortensen RM. Impaired activation of murine platelets lacking Galphai2. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:477–483. doi: 10.1172/JCI12818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang J, Wu J, Kowalska MA, Dalvi A, Prevost N, O'Brien PJ, Manning D, Poncz M, Lucki I, Blendy JA, Brass LF. Loss of signaling through the G protein Gz, results in abnormal platelet activation and altered responses to psychoactive drugs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:9984–9989. doi: 10.1073/pnas.180194597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hollopeter G, Jantzen HM, Vincent D, Li G, England L, Ramakrishnan V, Yang RB, Nurden P, Nurden A, Julius D, Conley PB. Identification of the platelet ADP receptor targeted by antithrombotic drugs. Nature. 2001;409:202–207. doi: 10.1038/35051599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Woulfe DS. Akt signaling in platelets and thrombosis. Expert Rev Hematol. 2010;3:81–91. doi: 10.1586/ehm.09.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Woulfe D, Jiang H, Mortensen R, Yang J, Brass LF. Activation of Rap1B by Gi family members in platelets. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:23382–23390. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202212200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Furlong B, Henderson AH, Lewis MJ, Smith JA. Endothelium-derived relaxing factor inhibits in vitro platelet aggregation. Br J Pharmacol. 1987;90:687–692. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1987.tb11221.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whittle BJ, Moncada S. Pharmacological interactions between prostacyclin and thromboxanes. Br Med Bull. 1983;39:232–238. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a071825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weksler BB. Prostacyclin. Prog Hemost Thromb. 1982;6:113–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yuhki K, Kojima F, Kashiwagi H, Kawabe J, Fujino T, Narumiya S, Ushikubi F. Roles of prostanoids in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular diseases: Novel insights from knockout mouse studies. Pharmacol Ther. 2011;129:195–205. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marcus AJ, Broekman MJ, Drosopoulos JHF, Islam N, Alyonycheva TN, Safier LB, Hajjar KA, Posnett DN, Schoenborn MA, Schooley KA, Gayle RB, Maliszewski CR. The endothelial cell ecto-ADPase responsible for inhibition of platelet function is CD39. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:1351–1360. doi: 10.1172/JCI119294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abramow-Newerly M, Roy AA, Nunn C, Chidiac P. RGS proteins have a signalling complex: interactions between RGS proteins and GPCRs, effectors, and auxiliary proteins. Cellular signalling. 2006;18:579–591. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ross EM, Wilkie TM. GTPase-activating proteins for heterotrimeric G proteins: regulators of G protein signaling (RGS) and RGS-like proteins. Annu Rev Biochem. 2000;69:795–827. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yowe D, Weich N, Prabhudas M, Poisson L, Errada P, Kapeller R, Yu K, Faron L, Shen MH, Cleary J, Wilkie TM, Gutierrez-Ramos C, Hodge MR. RGS18 is a myeloerythroid lineage-specific regulator of G-protein-signalling molecule highly expressed in megakaryocytes. Biochem J. 2001;359:109–118. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3590109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nagata Y, Oda M, Nakata H, Shozaki Y, Kozasa T, Todokoro K. A novel regulator of G-protein signaling bearing GAP activity for Galphai and Galphaq in megakaryocytes. Blood. 2001;97:3051–3060. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.10.3051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim SD, Sung HJ, Park SK, Kim TW, Park SC, Kim SK, Cho JY, Rhee MH. The expression patterns of RGS transcripts in platelets. Platelets. 2006;17:493–497. doi: 10.1080/09537100600758123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gagnon AW, Murray DL, Leadley RJ. Cloning and characterization of a novel regulator of G protein signalling in human platelets. Cell Signal. 2002;14:595–606. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(02)00012-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garcia A, Prabhakar S, Hughan S, Anderson TW, Brock CJ, Pearce AC, Dwek RA, Watson SP, Hebestreit HF, Zitzmann N. Differential proteome analysis of TRAP-activated platelets: involvement of DOK-2 and phosphorylation of RGS proteins. Blood. 2004;103:2088–2095. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-07-2392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berthebaud M, Riviere C, Jarrier P, Foudi A, Zhang Y, Compagno D, Galy A, Vainchenker W, Louache F. RGS16 is a negative regulator of SDF-1-CXCR4 signaling in megakaryocytes. Blood. 2005;106:2962–2968. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-02-0526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Signarvic RS, Cierniewska A, Stalker TJ, Fong KP, Chatterjee MS, Hess PR, Ma P, Diamond SL, Neubig RR, Brass LF. RGS/Gi2alpha interactions modulate platelet accumulation and thrombus formation at sites of vascular injury. Blood. 2010;116:6092–6100. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-05-283846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang X, Fu Y, Charbeneau RA, Saunders TL, Taylor DK, Hankenson KD, Russell MW, D'Alecy LG, Neubig RR. Pleiotropic phenotype of a genomic knock-in of an RGS-insensitive G184S Gnai2 allele. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:6870–6879. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00314-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fu Y, Zhong H, Nanamori M, Mortensen RM, Huang X, Lan K, Neubig RR. RGS-insensitive G-protein mutations to study the role of endogenous RGS proteins. Methods Enzymol. 2004;389:229–243. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)89014-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Allen PB, Ouimet CC, Greengard P. Spinophilin, a novel protein phosphatase 1 binding protein localized to dendritic spines. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:9956–9961. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Satoh A, Nakanishi H, Obaishi H, Wada M, Takahashi K, Satoh K, Hirao K, Nishioka H, Hata Y, Mizoguchi A, Takai Y. Neurabin-II/spinophilin. An actin filament-binding protein with one PDZ domain localized at cadherin-based cell-cell adhesion sites. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:3470–3475. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.6.3470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith FD, Oxford GS, Milgram SL. Association of the D2 dopamine receptor third cytoplasmic loop with spinophilin, a protein phosphatase-1-interacting protein. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:19894–19900. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.28.19894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Richman JG, Brady AE, Wang Q, Hensel JL, Colbran RJ, Limbird LE. Agonist-regulated Interaction between alpha2-adrenergic receptors and spinophilin. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:15003–15008. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011679200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang X, Zeng W, Kim MS, Allen PB, Greengard P, Muallem S. Spinophilin/neurabin reciprocally regulate signaling intensity by G protein-coupled receptors. Embo J. 2007;26:2768–2776. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bansal G, Druey KM, Xie Z. R4 RGS proteins: regulation of G-protein signaling and beyond. Pharmacol Ther. 2007;116:473–495. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fujii S, Yamazoe G, Itoh M, Kubo Y, Saitoh O. Spinophilin inhibits the binding of RGS8 to M1-mAChR but enhances the regulatory function of RGS8. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;377:200–204. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.09.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang X, Zeng W, Soyombo AA, Tang W, Ross EM, Barnes AP, Milgram SL, Penninger JM, Allen PB, Greengard P, Muallem S. Spinophilin regulates Ca2+ signalling by binding the N-terminal domain of RGS2 and the third intracellular loop of G-protein-coupled receptors. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:405–411. doi: 10.1038/ncb1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang Q, Zhao J, Brady AE, Feng J, Allen PB, Lefkowitz RJ, Greengard P, Limbird LE. Spinophilin blocks arrestin actions in vitro and in vivo at G protein-coupled receptors. Science. 2004;304:1940–1944. doi: 10.1126/science.1098274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ma P, Cierniewska A, Signarvic RS, Sinnamon A, Cieslak M, Stalker TJ, Brass LF. Discovery of a New Signaling Complex Based on Spinophilin That Regulates Platelet Activation In Vitro and In Vivo. Blood. 2010;116:161. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shattil SJ. The beta3 integrin cytoplasmic tail: protein scaffold and control freak. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7(Suppl. 1):210–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Prevost N, Kato H, Bodin L, Shattil SJ. Platelet integrin adhesive functions and signaling. Methods Enzymol. 2007;426:103–115. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(07)26006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Prevost N, Woulfe D, Tanaka T, Brass LF. Interactions between Eph kinases and ephrins provide a mechanism to support platelet aggregation once cell-to-cell contact has occurred. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:9219–9224. doi: 10.1073/pnas.142053899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Prevost N, Woulfe DS, Tognolini M, Tanaka T, Jian W, Fortna RR, Jiang H, Brass LF. Signaling by ephrinB1 and Eph kinases in platelets promotes Rap1 activation, platelet adhesion, and aggregation via effector pathways that do not require phosphorylation of ephrinB1. Blood. 2004;103:1348–1355. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-06-1781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Prevost N, Woulfe DS, Jiang H, Stalker TJ, Marchese P, Ruggeri ZM, Brass LF. Eph kinases and ephrins support thrombus growth and stability by regulating integrin outside-in signaling in platelets. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:9820–9825. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404065102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pasterkamp RJ, Giger RJ. Semaphorin function in neural plasticity and disease. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2009;19:263–274. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Roth L, Koncina E, Satkauskas S, Cremel G, Aunis D, Bagnard D. The many faces of semaphorins: from development to pathology. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66:649–666. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8518-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gherardi E, Love CA, Esnouf RM, Jones EY. The sema domain. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2004;14:669–678. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2004.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Negishi M, Oinuma I, Katoh H. Plexins: axon guidance and signal transduction. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005;62:1363–1371. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5018-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhu L, Bergmeier W, Wu J, Jiang H, Stalker TJ, Cieslak M, Fan R, Boumsell L, Kumanogoh A, Kikutani H, Tamagnone L, Wagner DD, Milla ME, Brass LF. Regulated surface expression and shedding support a dual role for semaphorin 4D in platelet responses to vascular injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:1621–1626. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606344104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wannemacher KM, Zhu L, Jiang H, Fong KP, Stalker TJ, Lee D, Tran AN, Neeves KB, Maloney S, Kumanogoh A, Kikutani H, Hammer DA, Diamond SL, Brass LF. Diminished contact-dependent reinforcement of Syk activation underlies impaired thrombus growth in mice lacking Semaphorin 4D. Blood. 2010;116:5707–5715. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-279943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kumanogoh A, Watanabe C, Lee I, Wang X, Shi W, Araki H, Hirata H, Iwahori K, Uchida J, Yasui T, Matsumoto M, Yoshida K, Yakura H, Pan C, Parnes JR, Kikutani H. Identification of CD72 as a lymphocyte receptor for the class IV semaphorin CD100: a novel mechanism for regulating B cell signaling. Immunity. 2000;13:621–631. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00062-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tamagnone L, Artigiani S, Chen H, He Z, Ming GI, Song H, Chedotal A, Winberg ML, Goodman CS, Poo M, Tessier-Lavigne M, Comoglio PM. Plexins are a large family of receptors for transmembrane, secreted, and GPI-anchored semaphorins in vertebrates. Cell. 1999;99:71–80. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80063-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Masuda K, Furuyama T, Takahara M, Fujioka S, Kurinami H, Inagaki S. Sema4D stimulates axonal outgrowth of embryonic DRG sensory neurones. Genes Cells. 2004;9:821–829. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2004.00766.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Basile JR, Afkhami T, Gutkind JS. Semaphorin 4D/plexin-B1 induces endothelial cell migration through the activation of PYK2 Src, the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-Akt pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:6889–6898. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.16.6889-6898.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lewandrowski U, Wortelkamp S, Lohrig K, Zahedi RP, Wolters DA, Walter U, Sickmann A. Platelet membrane proteomics: a novel repository for functional research. Blood. 2009;114:e10–e19. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-02-203828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fong KP, Barry C, Tran AN, Traxler EA, Wannemacher KM, Tang HY, Speicher KD, Blair IA, Speicher DW, Grosser T, Brass LF. Deciphering the human platelet sheddome. Blood. 2011;117:e15–e26. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-05-283838. 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kashiwagi H, Shiraga M, Kato H, Kamae T, Yamamoto N, Tadokoro S, Kurata Y, Tomiyama Y, Kanakura Y. Negative regulation of platelet function by a secreted cell repulsive protein, semaphorin 3A. Blood. 2005;106:913–921. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-10-4092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Watkins NA, Gusnanto A, de Bono B, De S, Miranda-Saavedra D, Hardie DL, Angenent WG, Attwood AP, Ellis PD, Erber W, Foad NS, Garner SF, Isacke CM, Jolley J, Koch K, Macaulay IC, Morley SL, Rendon A, Rice KM, Taylor N, Thijssen-Timmer DC, Tijssen MR, van der Schoot CE, Wernisch L, Winzer T, Dudbridge F, Buckley CD, Langford CF, Teichmann S, Gottgens B, Ouwehand WH. A HaemAtlas: characterizing gene expression in differentiated human blood cells. Blood. 2009;113:e1–e9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-06-162958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Newman PJ, Newman DK. Signal transduction pathways mediated by PECAM-1: new roles for an old molecule in platelet and vascular cell biology. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:953–964. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000071347.69358.D9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jackson DE, Kupcho KR, Newman PJ. Characterization of phosphotyrosine binding motifs in the cytoplasmic domain of platelet/endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (PECAM-1) that are required for the cellular association and activation of the protein-tyrosine phosphatase, SHP-2. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:24868–24875. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.40.24868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Moraes LA, Barrett NE, Jones CI, Holbrook LM, Spyridon M, Sage T, Newman DK, Gibbins JM. PECAM-1 regulates collagen-stimulated platelet function by modulating the association of PI3 Kinase with Gab1 and LAT. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8:2530–2541. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.04025.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Patil S, Newman DK, Newman PJ. Platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 serves as an inhibitory receptor that modulates platelet responses to collagen. Blood. 2001;97:1727–1732. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.6.1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Falati S, Patil S, Gross PL, Stapleton M, Merrill-Skoloff G, Barrett NE, Pixton KL, Weiler H, Cooley B, Newman DK, Newman PJ, Furie BC, Furie B, Gibbins JM. Platelet PECAM-1 inhibits thrombus formation in vivo. Blood. 2006;107:535–541. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Huber M, Izzi L, Grondin P, Houde C, Kunath T, Veillette A, Beauchemin N. The carboxyl-terminal region of biliary glycoprotein controls its tyrosine phosphorylation and association with protein-tyrosine phosphatases SHP-1 and SHP-2 in epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:335–344. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.1.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Beauchemin N, Kunath T, Robitaille J, Chow B, Turbide C, Daniels E, Veillette A. Association of biliary glycoprotein with protein tyrosine phosphatase SHP-1 in malignant colon epithelial cells. Oncogene. 1997;14:783–790. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1200888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wong C, Liu Y, Yip J, Chand R, Wee JL, Oates L, Nieswandt B, Reheman A, Ni H, Beauchemin N, Jackson DE. CEACAM1 negatively regulates platelet-collagen interactions and thrombus growth in vitro and in vivo. Blood. 2009;113:1818–1828. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-06-165043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Stalker TJ, Wu J, Morgans A, Traxler EA, Wang L, Chatterjee MS, Lee D, Quertermous T, Hall RA, Hammer DA, Diamond SL, Brass LF. Endothelial cell specific adhesion molecule (ESAM) localizes to platelet-platelet contacts and regulates thrombus formation in vivo. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7:1886–1896. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Naik MU, Naik UP. Junctional adhesion molecule-A negatively regulates integrin alpha IIB beta 3-dependent contractile signaling in platelets. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7 OC-MO-046. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ostermann G, Weber KS, Zernecke A, Schroder A, Weber C. JAM-1 is a ligand of the beta(2) integrin LFA-1 involved in transendothelial migration of leukocytes. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:151–158. doi: 10.1038/ni755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Santoso S, Sachs UJ, Kroll H, Linder M, Ruf A, Preissner KT, Chavakis T. The junctional adhesion molecule 3 (JAM-3) on human platelets is a counterreceptor for the leukocyte integrin Mac-1. J Exp Med. 2002;196:679–691. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dubois C, Panicot-Dubois L, Gainor JF, Furie BC, Furie B. Thrombin-initiated platelet activation in vivo is vWF independent during thrombus formation in a laser injury model. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:953–960. doi: 10.1172/JCI30537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gross PL, Furie BC, Merrill-Skoloff G, Chou J, Furie B. Leukocyte-versus microparticle-mediated tissue factor transfer during arteriolar thrombus development. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;78:1318–1326. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0405193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Maxwell MJ, Westein E, Nesbitt WS, Giuliano S, Dopheide SM, Jackson SP. Identification of a 2-stage platelet aggregation process mediating shear-dependent thrombus formation. Blood. 2007;109:566–576. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-028282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.van Gestel MA, Heemskerk JW, Slaaf DW, Heijnen VV, Sage SO, Reneman RS, oude Egbrink MG. Real-time detection of activation patterns in individual platelets during thromboembolism in vivo: differences between thrombus growth and embolus formation. J Vasc Res. 2002;39:534–543. doi: 10.1159/000067208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Vandendries ER, Hamilton JR, Coughlin SR, Furie B, Furie BC. PAR4 is required for platelet thrombus propagation but not fibrin generation in a mouse model of thrombosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:288–292. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610188104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Stalker TJ, Traxler EA, Diamond SL, Brass LF. Development of a stable thrombotic core with limited access to plasma proteins during thrombus formation in vivo. Blood. 2010;116:2013. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Nesbitt WS, Westein E, Tovar-Lopez FJ, Tolouei E, Mitchell A, Fu J, Carberry J, Fouras A, Jackson SP. A shear gradient-dependent platelet aggregation mechanism drives thrombus formation. Nat Med. 2009;15:665–673. doi: 10.1038/nm.1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gross PL, Furie BC, Merrill-Skoloff G, Chou J, Furie B. Leukocyte versus microparticle-mediated tissue factor transfer during arteriolar thrombus development. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;78:1318–1326. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0405193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Maynard DM, Heijnen HF, Horne MK, White JG, Gahl WA. Proteomic analysis of platelet alpha-granules using mass spectrometry. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5:1945–1955. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02690.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wannemacher KM, Zhu L, Jiang H, Fong KP, Stalker TJ, Lee D, Tran AN, Neeves KB, Maloney S, Kumanogoh A, Kikutani H, Hammer DA, Diamond SL, Brass LF. Diminished contact-dependent reinforcement of Syk activation underlies impaired thrombus growth in mice lacking Semaphorin 4D. Blood. 2010 doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-279943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Calaminus SD, Auger JM, McCarty OJ, Wakelam MJ, Machesky LM, Watson SP. MyosinIIa contractility is required for maintenance of platelet structure during spreading on collagen and contributes to thrombus stability. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5:2136–2145. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02696.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Leon C, Eckly A, Hechler B, Aleil B, Freund M, Ravanat C, Jourdain M, Nonne C, Weber J, Tiedt R, Gratacap MP, Severin S, Cazenave JP, Lanza F, Skoda R, Gachet C. Megakaryocyte-restricted MYH9 inactivation dramatically affects hemostasis while preserving platelet aggregation and secretion. Blood. 2007;110:3183–3191. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-03-080184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ono A, Westein E, Hsiao S, Nesbitt WS, Hamilton JR, Schoenwaelder SM, Jackson SP. Identification of a fibrin-independent platelet contractile mechanism regulating primary hemostasis and thrombus growth. Blood. 2008;112:90–99. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-12-127001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]