Abstract

Inflammation in the vascular wall is important for development of atherosclerosis. We have shown previously that arachidonate 15-lipoxygenase type B (ALOX15B) is more highly expressed in human atherosclerotic lesions than in healthy arteries. This enzyme oxidizes fatty acids to substances that promote local inflammation and is expressed in lipid-loaded macrophages (foam cells) present in the atherosclerotic lesions. Here, we investigated the role of ALOX15B in foam cell formation in human primary macrophages and found that silencing of human ALOX15B decreased cellular lipid accumulation as well as proinflammatory cytokine secretion from macrophages. To investigate the role of ALOX15B in promoting the development of atherosclerosis in vivo, we used lentiviral shRNA silencing and bone marrow transplantation to knockdown mouse Alox15b gene expression in LDL-receptor-deficient (Ldlr −/−) mice. Knockdown of mouse Alox15b in vivo decreased plaque lipid content and markers of inflammation. In summary, we have shown that ALOX15B influences progression of atherosclerosis, indicating that this enzyme has an active proatherogenic role.

Introduction

Atherosclerosis is a complex disease that involves chronic inflammation at every stage from initiation to progression and eventually to plaque rupture [1]. Macrophage-derived foam cells play integral roles in atherosclerosis and are key regulators of the lipid-driven proinflammatory responses that promote atherosclerosis [2]. An inflammatory subset of macrophages accumulates in atherosclerotic plaques and produces proinflammatory cytokines [2]–[3] as well as lipoxygenases, which oxygenate polyunsaturated fatty acids to proinflammatory mediators [4]. Arachidonate 15-lipoxygenase (ALOX15) catalyzes the production of eicosanoids that activate monocyte integrins and thereby enhance the adhesion of monocytes to the endothelium [5]–[6]. In vitro, ALOX15 appears to be proatherogenic, as it can be directly involved in LDL oxidation [7]–[9]. In vivo, however, both pro- and anti-atherogenic effects have been reported (reviewed in [10]). For example, atherosclerotic lesion formation is increased in Ldlr −/− mice that overexpress human ALOX15 in the endothelium [11]. In contrast, transgenic rabbits overexpressing human ALOX15 in macrophages display reduced atherosclerotic lesion area in the thoracic aorta [12].

Previous studies of lipoxygenases in the development of atherosclerotic plaques have largely focused on ALOX15 type A (ALOX15A) [13]. However, ALOX15 type B (ALOX15B) is expressed at considerably higher levels than ALOX15A in human carotid plaque macrophages [14]–[15] and levels of ALOX15B have been shown to be higher in symptomatic compared with asymptomatic lesions [14] suggesting a role for this enzyme in the atherosclerotic process. Furthermore, we have previously shown that overexpression of ALOX15B in macrophages increases secretion of the chemokines CXCL10 and CCL2, which are chemoattractants for T cells and monocytes [16]. In addition, products released in response to increased ALOX15B activation lead to increased expression of the T-cell activation marker CD69 as well as increased T-cell migration [16].

Here, we investigated the role of ALOX15B in foam cell formation in human monocyte-derived macrophages and found that silencing of the gene encoding ALOX15B (ALOX15B) decreases cellular lipid accumulation as well as proinflammatory signaling from macrophages. We also investigated the role of the mouse ortholog of ALOX15B (encoded by the gene Alox15b, also known as Alox8 [17]) in Ldlr −/− mice. In contrast to human ALOX15B, which catalyzes the formation of 15(S)-hydroperoxy eicosatetraenoic acid (HPETE), mouse ALOX15B produces 8(S)-HPETE and 8(S)-, 15(S)-diHPETE from arachidonic acid. However, the two enzymes display the highest sequence identity among all the mammalian lipoxygenases and substitution of only two amino acids of mouse ALOX15B is required to change the eicosanoids generated to 90% 15S-HETE [18]. We observed that mice transplanted with mouse Alox15b knockdown bone marrow displayed decreased atherosclerosis and impaired immune signaling. On the basis of our results, we suggest that ALOX15B has a proatherogenic and proinflammatory role during atherogenesis.

Materials and Methods

Primary macrophages

Buffy coats were obtained from healthy adult volunteer blood donors at Kungälv Hospital, Sweden, and samples were de-identified before handling. Human mononuclear cells were isolated by centrifugation in a discontinuous gradient of Ficoll-Paque (GE Healthcare). Cells were seeded in Macrophage-SFM medium (Gibco) containing granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF). After 3 days, the medium was changed to RPMI medium without GM-CSF and cells were cultured for 7 days before transfection. Macrophages were transfected with 20 nmol/L ALOX15B siRNA (Qiagen, SI03076206) or nonsilencing control siRNA (Qiagen, 1027280) in HiPerFect transfection reagent (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Cells were washed after 24 h, siRNA was added again and cells were incubated with or without dimethyloxalylglycine (DMOG) for 24 h before extraction of RNA. DMOG is an inhibitor of HIF-prolyl hydroxylase, and acts to stabilize HIF-1α expression causing induction of ALOX15B [15].

Mice

C57BL/6 Ldlr −/− mice (7-week-old males) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA) and housed in a pathogen-free barrier facility. Bone marrow donor mice of the same genotype (13-week-old males) were also purchased. All animal studies were approved by the regional animal ethics committee (animal ethics committee of Gothenburg).

Alox15b-silenced mice

Silencing of Alox15b in mice of C57BL/6 Ldlr −/− background was accomplished in vivo through lentiviral short-hairpin (sh)RNA silencing [19] using shRNA delivered with lentivirus to bone marrow from donor mice. Lentiviral transduction particles containing Alox15b shRNA (TRCN0000076452, NM_009661.2-700s1c1) or nonsilencing control shRNA (SHC002) respectively were purchased from Sigma. Bone marrow including hematopoetic stemcells with genotype Ldlr −/− were isolated from C57Bl/6 Ldlr −/− mice and infected with either Alox15b shRNA encoding or control shRNA encoding lentivirus over night in Stem span media (Stemcell technologies). Cells were harvested and injected retroorbitally to lethally irradiated (9 Gy) recipient mice. The mice were fed a western type diet (Harlan TD88137) for 20 weeks.

Analysis of gene and protein expression

Total RNA was isolated with the RNeasy kit (Qiagen). Expression of human ALOX15B and mouse Alox15b mRNA was determined and normalized to β-actin mRNA expression using quantitative real-time PCR. The reverse transcription reaction was set up using a cDNA reverse transcription kit (#4368814) and performed with a Gene Amp PCR system 9700 (Applied Biosystems). Real time PCR amplification was set up using Taq man gene expression assays for human ALOX15A (Hs00609608_m1), human ALOX15B (Hs00153988_m1), mouse Alox15b (Mm01325281_m1), human ACTB (Hs99999903_m1) mouse Emr1 (Mm00802529_m1) and mouse ActB (Mm00607939_s1) respectively in combination with Universal PCR master mix (#4324018) and performed for 50 cycles on an ABI PRISM 7700 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems).

Immunoblots were prepared as described [20]. Total cellular lysates were prepared from human macrophages, mouse bone marrow macrophages and aortic tissue. Antibodies are listed in Table 1. The polyclonal ALOX15B antibody (LX25) has been well characterized and found to detect human as well as mouse ALOX15B but not ALOX15A [21].

Table 1. Antibodies used in this study.

| Source | Antibody | Description | 2nd antibody | |

| ALOX15B | Oxford1 | LX25 | Rabbit, poly4 | Goat anti rabbit HRP6 GE7 |

| ALOX15A | Abcam | ab54772 | Mouse, mono5 | Goat anti mouse HRP6 GE7 |

| CD4 (T cells) | BD2 | 550278 | Rat, mono5 | Goat anti rat HRP6, GE7 |

| CD8 (T cells) | BD2 | 550281 | Rat, mono5 | Goat anti rat HRP6, GE7 |

| Mac-2 | NB3 | CL8942AP | Rat | Goat anti rat HRP6, GE7 |

| α-actin Cy3 | Sigma | C6198 | Mouse, mono5 | - |

Oxford Biochemical research,

BD Bioscience,

Nordic biosite,

Polyclonal,

Monoclonal,

Horse rabbit peroxidase,

GE healthcare.

Quantification of Oil Red O-stained lipid droplets

Human macrophages were grown on chamber slides (Lab-Tek Systems), stained with Oil Red O and hematoxylin, and viewed with a Zeiss Axioplan 2 microscope. Twenty images per slide were obtained and analyzed for red pixels (lipid droplets), cell size and cell number using BioPix iQ 2.2.1 (Gothenburg, Sweden, see www.biopix.se for further information) [22].

Cytokine analysis

Secreted cytokines [interferon (IFN)-γ, interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, IL-8 and IL-12 (total)] were analyzed in medium from cultured primary human macrophages using Human Proinflammatory Multiplex assay (Meso Scale Discovery; K15007C) according to the manufacturer's instructions and a SECTOR Imager 2400 reader (Meso Scale Discovery).

Mouse plasma IL-2 was analyzed using a Mouse TH1/TH2 Multiplex assay (Meso Scale Discovery; K15013C) according to the manufacturer's instructions and a SECTOR Imager 2400 reader (Meso Scale Discovery).

Quantification of atherosclerosis

The aortic roots were embedded in OCT Tissue-Tec medium and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. Cryostat sections (10 µm thick) were cut from the level of the aortic valves and distally, and stained in 0.5% Oil Red O or used for immunohistochemistry (see next section). Distal aortae were dissected free from adipose and connective tissue, cut open longitudinally, and pinned flat on silicone-coated dishes. The aorta was then fixed in 70% ethanol for 5 minutes, stained with 0.5% Sudan IV for 6 minutes, and differentiated for 3 minutes in 80% ethanol. Digital images of the entire vessel were captured and the outline of the aortic surface was defined manually, whereas the stained lesion area was defined using computerized color selection in BioPix iQ 2.2.1 (Gothenburg, Sweden). The extent of atherosclerosis was calculated as the percentage of the aortic surface covered by lesions.

Immunohistochemistry

Cryostat sections of the aortic root were fixed for 10 minutes in ice-cold acetone, dried, and blocked in 5% goat serum in Tris-buffered saline. Sections were incubated (60 minutes, room temperature) with antibodies according to Table 1. Endogenous peroxidase was silenced with 0.3% H2O2 in H2O for 10 minutes. 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole (AEC) was used for detection. α-actin was stained using a Cy3 conjugated primary antibody. Collagen was stained using Masson's trichrome stains according to the manufacturer's instructions (Sigma; HT-15). Pictures were taking using a Zeiss Axioplan 2 epifluorescence microscope with an Axiocam camera and Axiovision software. Quantification of stained lesion area was defined using computerized color selection in BioPix iQ 2.2.1 (Gothenburg, Sweden, see www.biopix.se for further information) [22].

Results

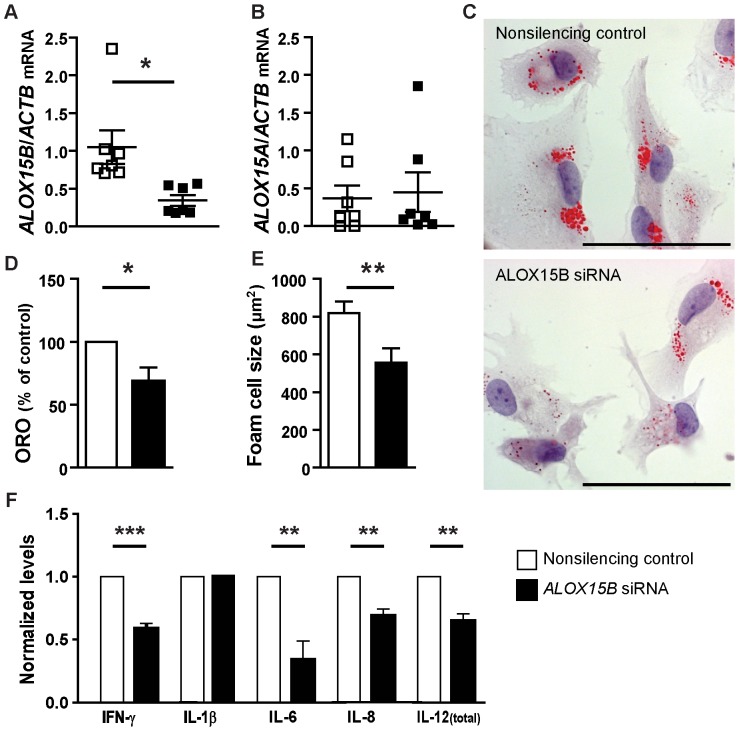

Knockdown of ALOX15B in human macrophages decreases cellular lipid levels, foam cell size and cytokine secretion

Transfection of human primary macrophages with ALOX15B siRNA resulted in knockdown of ALOX15B mRNA to approximately 50% of nonsilenced levels ( Fig. 1A ), but did not affect the expression of ALOX15A mRNA ( Fig. 1B ) or ALOX15A protein (too low levels to detect, data not shown). ALOX15B knockdown resulted in decreased lipid droplet accumulation as shown by reduced Oil Red O staining ( Fig. 1C and D ) and decreased foam cell size ( Fig. 1E ). These data indicate that ALOX15B can promote lipid droplet formation. In vitro experiments with human primary macrophages also showed lower levels of secreted IFN-γ, IL-6, IL-8 and IL-12 (total) while there was no change in the levels of IL-1β ( Fig. 1F ) in the medium when ALOX15B was knocked down using siRNA, indicating that ALOX15B affects secretion of some proinflammatory cytokines.

Figure 1. Decreased lipid uptake and immunological signaling in human ALOX15B-silenced macrophages.

Lipid accumulation was analyzed in human primary macrophages transfected with nonsilencing control siRNA or ALOX15B siRNA using Oil Red O staining after incubation with DMOG. A) Quantification of ALOX15B expression normalized to ActB expression measured with Q-PCR. B) Quantification of ALOX15A expression normalized to ActB expression measured with Q-PCR. C) Representative picture showing Oil Red O staining of control and ALOX15B-silenced macrophages (Scale bar = 50 µm). D) Quantification of Oil Red O staining in human primary macrophages (n = 7) normalized to control. E) Size of control and ALOX15B-silenced human primary macrophages (foam cells). F) Quantification of secreted cytokines in media from human primary macrophages (n = 7). Data are presented as mean±SEM normalized to control.

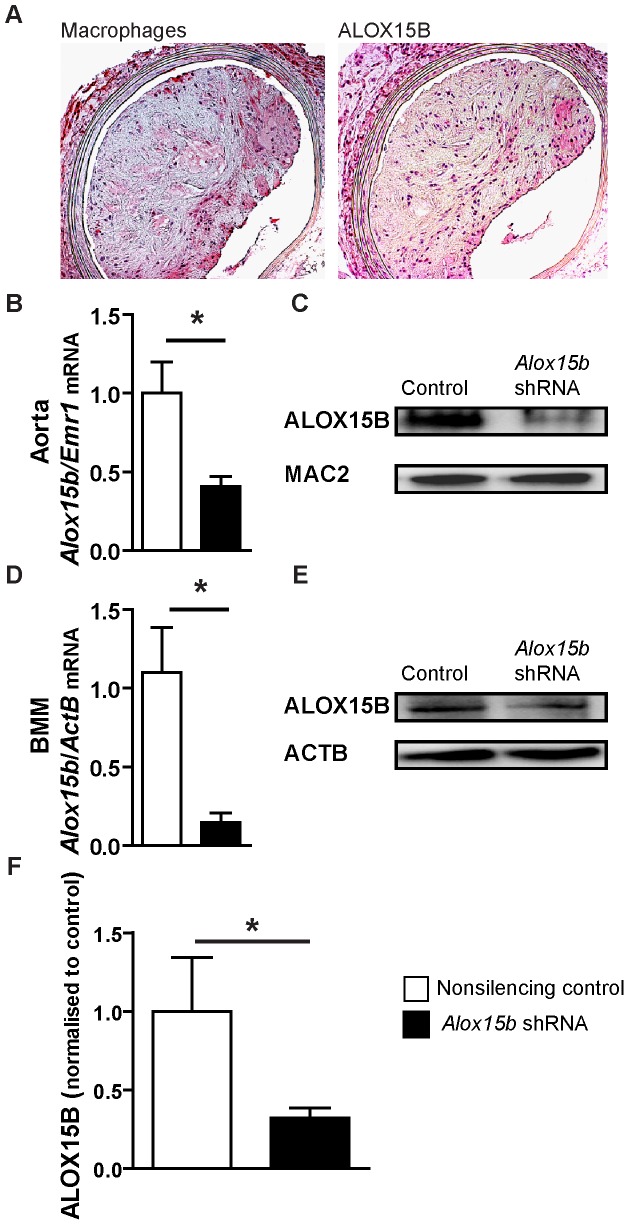

Knockdown of mouse Alox15b decreases atherosclerosis in mice aorta

Immunohistochemical analysis of serial sections of aorta from cholesterol-fed Ldlr −/− mice showed that mouse ALOX15B was expressed in macrophage-rich areas of atherosclerotic plaques in mice ( Fig. 2A ).

Figure 2. Alox15b knockdown in LDLr−/− mice.

A) Immunohistochemical detection of macrophages and ALOX15B in Ldlr−/− mice. B) Quantification of Alox15b expression, normalized to Emr1 expression (macrophage marker) in aortic tissue using Q-PCR (n = 2 for control and n = 3 for Alox15b shRNA). The sections presented in figure 2A were stained with Mayer's hematoxylin while the quantified sections used for figure 2B were not. C) Western blotting of ALOX15B and MAC-2 (macrophage marker) in aortic tissue. D) Quantification of Alox15b expression in bone marrow macrophages (BMM) isolated and differentiated at the end of the silencing experiment using Q-PCR (n = 2 for control and n = 3 for Alox15b shRNA). E) Western blotting of ALOX15B and ACTB in bone marrow macrophages. F) ALOX15B levels measured by immunohistochemistry in sections from aortic sinus from control and Alox15b knockdown mice (n = 7 per group). Data are presented as mean±SEM.

To investigate the importance of mouse ALOX15B in atherogenesis, lethally irradiated Ldlr −/− mice were transplanted with bone marrow cells infected with lentivirus containing Alox15b shRNA or nonsilencing control shRNA and fed a western diet for 20 weeks to induce atherosclerosis. Knockdown of Alox15b was confirmed by Q-PCR of mRNA and western blotting of protein from aortic tissue ( Fig. 2B and C ) and bone marrow macrophages ( Fig. 2D and E ) from recipient mice and by immunohistochemical evaluation of the proximal aorta from recipient mice ( Fig. 2F ).

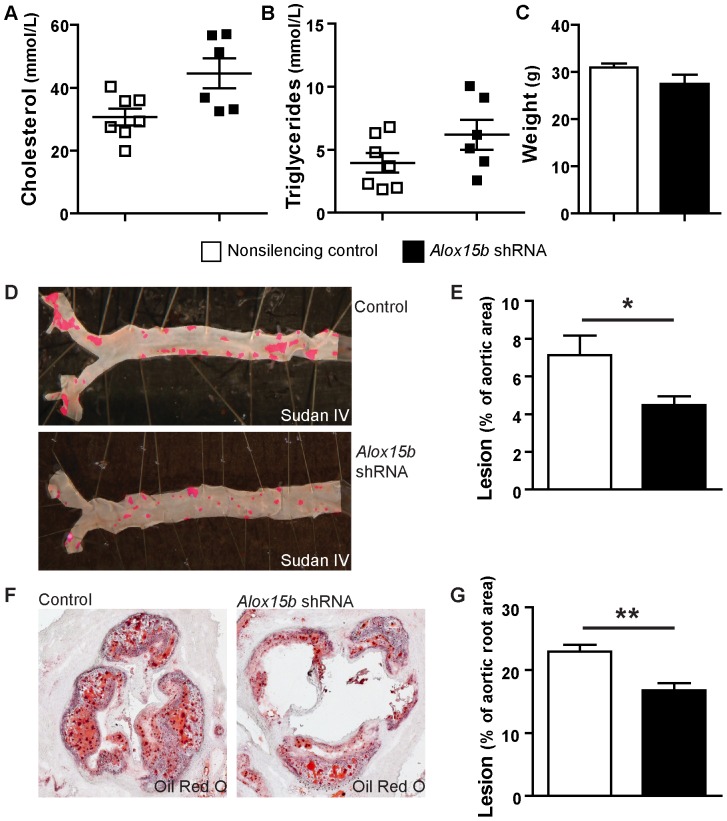

Body weight, plasma cholesterol and triglycerides did not differ between the two groups ( Fig. 3A, B, C ). Atherosclerotic lesions both in the whole aorta ( Fig. 3D and E ) and in the aortic root ( Fig. 3F and G ) were significantly decreased in mice that received Alox15b knockdown bone marrow compared to nonsilencing control.

Figure 3. Decreased atherosclerotic lesions in aortas in Alox15b knockdown mice.

A) Plasma cholesterol, B) plasma triglycerides and C) body weight of Alox15b knockdown and control mice. D) Representative photographs showing aorta pinned out by en face technique and stained with Sudan IV. E) Quantification of subendothelial lipid accumulation in the aorta (n = 7 per group). F) Representative histological analysis of the aortic sinus stained with Oil Red O. G) Quantification of subendothelial lipid accumulation in the aortic root (n = 6 per group). Data are presented as mean±SEM.

These data show that atherosclerotic lesions are decreased in Alox15b knockdown mice.

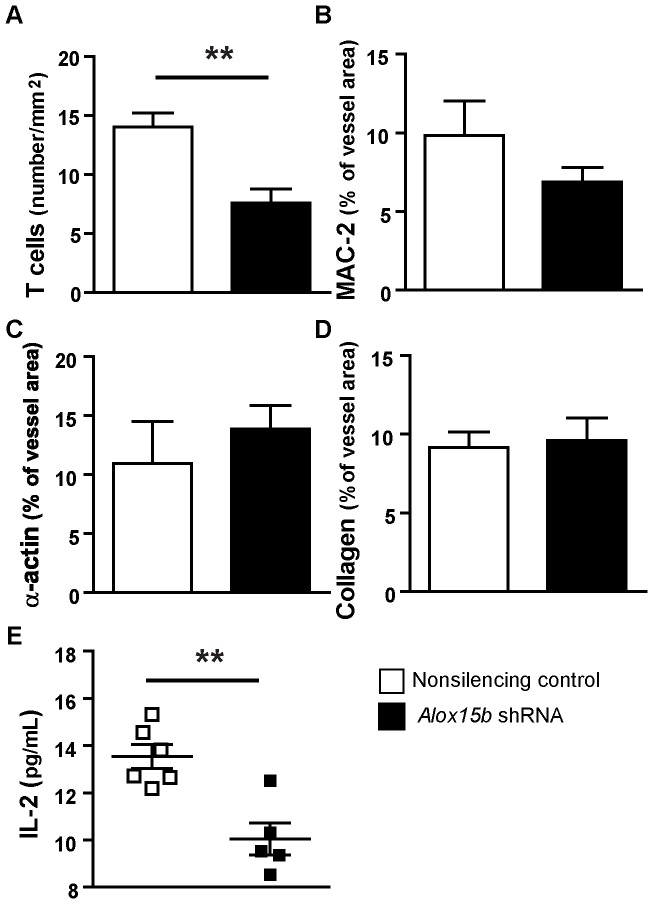

Knockdown of mouse Alox15b reduces T cell number and IL-2 levels in vivo

The number of T cells was significantly reduced in lesion areas in Alox15b knockdown mice ( Fig. 4A ) while no significant change was found in plaque macrophage content ( Fig. 4B ). Markers of plaque stability (collagen and α-actin) showed no change ( Fig. 4C and D ). To evaluate the possible proinflammatory role of mouse ALOX15B, we also measured cytokine levels in plasma from Alox15b knockdown mice compared to nonsilencing shRNA control-animals. The knockdown animals displayed significantly reduced plasma levels of IL-2 ( Fig. 4E ) indicating that Alox15b knockdown may cause decreased systemic inflammation.

Figure 4. Analysis of plaque composition and plasma levels of IL-2.

Sections from aortic sinuses were stained with antibodies against A) CD4/CD8 (T cells), B) MAC-2 (macrophages), C) α-actin (smooth muscle cells), and D) collagen. Data are presented as mean±SEM. E) Plasma levels of soluble IL-2. (n = 6 per group).

Discussion

In the present report, we studied the effects of decreased ALOX15B levels in human macrophages as well as in an atherosclerotic mouse model. Silencing of ALOX15B in human macrophages decreased cellular lipid accumulation and reduced proinflammatory cytokine secretion. In vivo experiments in an atherosclerotic mouse model showed that mouse Alox15b knockdown resulted in decreased atherosclerosis (measured as plaque area) as well as decreased inflammation, providing new evidence for ALOX15B as a proatherogenic protein.

ALOX15B knockdown in human macrophages caused markedly decreased cellular lipid accumulation and foam cell size, suggesting that ALOX15B is involved in lipid accumulation and foam cell formation. Silencing of ALOX15B decreased secretion of the proinflammatory cytokines IFN-γ IL-6, IL-8 and IL-12 from the macrophages. IFN-γ is known to promote foam cell formation [2] suggesting that the anti-foam cell formation effect of ALOX15B knockdown could be partly due to lower levels of IFN-γ. Previous data show that ALOX15B expression in human macrophages induces chemokine secretion and that the preconditioned medium from these macrophages positively affects T-cell migration [23].

To understand the role of ALOX15B in atherosclerosis in vivo, we studied the consequence of Alox15b knockdown in an atherosclerotic mouse model. Although mouse ALOX15B differs from human ALOX15B, the two enzymes display 78% sequence identity and overproduction of human or mouse ALOX15B inhibited growth in mouse keratinocytes to the same extent, suggesting common signaling pathways [24]. Upon knockdown of Alox15b in the atherosclerotic mouse model, we found that subendothelial lipid accumulation was decreased in aortas from Ldlr −/− mice that received Alox15b knockdown bone marrow. The difference in lipid accumulation was not due to differences in plaque macrophage content, as no significant change in MAC-2 staining between the two groups was detected. Since silencing of human ALOX15B affected lipid accumulation in human macrophages, it is reasonable to propose that the effect on subendothelial lipid accumulation in mouse plaques is at least partly due to direct effects on foam cell formation.

Plaque T-cell content and plasma levels of IL-2 were significantly decreased in mice that received Alox15b-deficient bone marrow, indicating that mouse ALOX15B may also affect immunoregulation. Systemic administration of IL-2 to ApoE−/− mice has been shown to cause increased atherogenesis while anti-IL-2 antibodies decreased development of atherosclerosis [25]. IL-2 plays a significant role in T-cell activation and proliferation [26]. In agreement, our previous results show that human ALOX15B overexpression in human macrophages induces activation and migration of T cells [16]. Decreased T-cell content as well as decreased IL-2 levels in mice that received Alox15B deficient bone marrow are consistent with a role for mouse ALOX15B and its products in recruiting T cells to the lesion. Lesional T cells mainly have properties of the proinflammatory Th1 subtype and secrete the cytokines IL-2, IFN-γ, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α. These cytokines cause activation of macrophages and vascular cells, promote inflammation and also participate in cellular immunity [27]. Atherosclerosis is a Th1-cell-driven disease and Th1 cytokines stimulate plaque formation [28]. Furthermore IL-2 promotes angiogenesis by activation of Akt (protein kinase B) and increase of reactive oxygen species [29]. Angiogenesis in human lesions may be maladaptive as it promotes lesion instability, with increased risk of plaque rupture and cardiovascular events [30]. It is likely that the reduced T-cell content in plaques of mice that received Alox15b-deficient bone marrow is caused by decreased immunological signaling from plaque macrophages, since silencing of human ALOX15B caused reduced cytokine expression in human macrophages.

Our experiments show that reduction of ALOX15B decreases inflammation and lipid accumulation, both in human primary macrophages and in mice, suggesting an active proinflammatory and proatherogenic role of ALOX15B.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Rosie Perkins for expert editing of the manuscript and Christina Ullström and Pernilla Jirholt for excellent technical assistance.

Funding Statement

Swedish Research Council, the Swedish Heart-Lung Foundation, the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research and the Sahlgrenska University Hospital ALF research grants. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Paoletti R, Gotto AM Jr, Hajjar DP (2004) Inflammation in atherosclerosis and implications for therapy. Circulation 109: III20–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. McLaren JE, Michael DR, Ashlin TG, Ramji DP (2011) Cytokines, macrophage lipid metabolism and foam cells: implications for cardiovascular disease therapy. Prog Lipid Res 50: 331–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Libby P, Okamoto Y, Rocha VZ, Folco E (2010) Inflammation in atherosclerosis: transition from theory to practice. Circ J 74: 213–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kuhn H, O'Donnell VB (2006) Inflammation and immune regulation by 12/15-lipoxygenases. Prog Lipid Res 45: 334–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hedrick CC, Kim MD, Natarajan RD, Nadler JL (1999) 12-Lipoxygenase products increase monocyte:endothelial interactions. Adv Exp Med Biol 469: 455–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Waddington E, Sienuarine K, Puddey I, Croft K (2001) Identification and quantitation of unique fatty acid oxidation products in human atherosclerotic plaque using high-performance liquid chromatography. Anal Biochem 292: 234–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ezaki M, Witztum JL, Steinberg D (1995) Lipoperoxides in LDL incubated with fibroblasts that overexpress 15-lipoxygenase. J Lipid Res 36: 1996–2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kuhn H, Belkner J, Suzuki H, Yamamoto S (1994) Oxidative modification of human lipoproteins by lipoxygenases of different positional specificities. J Lipid Res 35: 1749–1759. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yla-Herttuala S, Luoma J, Viita H, Hiltunen T, Sisto T, et al. (1995) Transfer of 15-lipoxygenase gene into rabbit iliac arteries results in the appearance of oxidation-specific lipid-protein adducts characteristic of oxidized low density lipoprotein. J Clin Invest 95: 2692–2698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Funk CD, Cyrus T (2001) 12/15-lipoxygenase, oxidative modification of LDL and atherogenesis. Trends Cardiovasc Med 11: 116–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Harats D, Shaish A, George J, Mulkins M, Kurihara H, et al. (2000) Overexpression of 15-lipoxygenase in vascular endothelium accelerates early atherosclerosis in LDL receptor-deficient mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 20: 2100–2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shen J, Herderick E, Cornhill JF, Zsigmond E, Kim HS, et al. (1996) Macrophage-mediated 15-lipoxygenase expression protects against atherosclerosis development. J Clin Invest 98: 2201–2208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhao L, Funk CD (2004) Lipoxygenase pathways in atherogenesis. Trends Cardiovasc Med 14: 191–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gertow K, Nobili E, Folkersen L, Newman JW, Pedersen TL, et al. (2011) 12- and 15-lipoxygenases in human carotid atherosclerotic lesions: associations with cerebrovascular symptoms. Atherosclerosis 215: 411–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hulten LM, Olson FJ, Aberg H, Carlsson J, Karlstrom L, et al. (2010) 15-Lipoxygenase-2 is expressed in macrophages in human carotid plaques and regulated by hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha. Eur J Clin Invest 40: 11–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Danielsson KN, Rydberg EK, Ingelsten M, Akyurek LM, Jirholt P, et al. (2008) 15-Lipoxygenase-2 expression in human macrophages induces chemokine secretion and T cell migration. Atherosclerosis 199: 34–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Furstenberger G, Marks F, Krieg P (2002) Arachidonate 8(S)-lipoxygenase. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat 68–69: 235–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jisaka M, Kim RB, Boeglin WE, Brash AR (2000) Identification of amino acid determinants of the positional specificity of mouse 8S-lipoxygenase and human 15S-lipoxygenase-2. J Biol Chem 275: 1287–1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Eefting D, Bot I, de Vries MR, Schepers A, van Bockel JH, et al. (2009) Local lentiviral short hairpin RNA silencing of CCR2 inhibits vein graft thickening in hypercholesterolemic apolipoprotein E3-Leiden mice. J Vasc Surg 50: 152–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Frost SC, Lane MD (1985) Evidence for the involvement of vicinal sulfhydryl groups in insulin-activated hexose transport by 3T3-L1 adipocytes. J Biol Chem 260: 2646–2652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jisaka M, Kim RB, Boeglin WE, Nanney LB, Brash AR (1997) Molecular cloning and functional expression of a phorbol ester-inducible 8S-lipoxygenase from mouse skin. J Biol Chem 272: 24410–24416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Andersson L, Bostrom P, Ericson J, Rutberg M, Magnusson B, et al. (2006) PLD1 and ERK2 regulate cytosolic lipid droplet formation. J Cell Sci 119: 2246–2257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Danielsson KN, Rydberg EK, Ingelsten M, Akyurek LM, Jirholt P, et al. (2008) 15-Lipoxygenase-2 expression in human macrophages induces chemokine secretion and T cell migration. Atherosclerosis 199: 34–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schweiger D, Furstenberger G, Krieg P (2007) Inducible expression of 15-lipoxygenase-2 and 8-lipoxygenase inhibits cell growth via common signaling pathways. J Lipid Res 48: 553–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Upadhya S, Mooteri S, Peckham N, Pai RG (2004) Atherogenic effect of interleukin-2 and antiatherogenic effect of interleukin-2 antibody in apo-E-deficient mice. Angiology 55: 289–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ross R (1999) Atherosclerosis–an inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med 340: 115–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hansson GK, Libby P, Schonbeck U, Yan ZQ (2002) Innate and adaptive immunity in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Circ Res 91: 281–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hansson GK, Libby P (2006) The immune response in atherosclerosis: a double-edged sword. Nat Rev Immunol 6: 508–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bae J, Park D, Lee YS, Jeoung D (2008) Interleukin-2 promotes angiogenesis by activation of Akt and increase of ROS. J Microbiol Biotechnol 18: 377–382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ribatti D, Levi-Schaffer F, Kovanen PT (2008) Inflammatory angiogenesis in atherogenesis–a double-edged sword. Ann Med 40: 606–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]