Abstract

Phospholipase C produces two second messengers - diacylglycerol (DAG), which remains in the membrane, and inositol triphosphate (IP3), which triggers the release of calcium ions (Ca2+) from intracellular stores. Genetically encoded sensors based on a single circularly permuted fluorescent protein (FP) are robust tools for studying intracellular Ca2+ dynamics. We have developed a robust sensor for DAG based on a circularly permuted green FP that can be co-imaged with the red fluorescent Ca2+ sensor R-GECO for simultaneous measurement of both second messengers.

Introduction

G protein couple receptors (GPCR) activate heterotrimeric G proteins that in turn interact with many different effectors to alter the levels of intracellular second messengers such as cyclic nucleotides, intracellular Ca2+, DAG, and IP3. A particular GPCR, acting through one type of heterotrimeric G protein, can alter the activity of multiple effectors and second messengers such that the signal that is generated within the cell involves a complex pattern of second messenger signaling coordinated in space and time. To understand this pattern of activity, and unambiguously determine which G-protein pathway causes it, new multiplex sensor systems are needed that can simultaneously measure multiple second messengers.

Many cell surface receptors couple to the heterotrimeric G protein Gq, which in turn activates Phospholipase C (PLC). PLC produces two different second messengers, DAG and IP3, and ultimately the IP3 causes an increase in intracellular Ca2+. It is this coordinated increase of both DAG and cytosolic Ca2+ that triggers the activation of conventional isoforms of protein kinase C (cPKC) which in turn phosphorylate many different protein targets. To date, the most robust fluorescent sensors for this pathway detect Ca2+, but a rise in Ca2+ is an ambiguous signal: there are other signaling pathways that cause increases in intracellular Ca2+. To unambiguously resolve PLC pathway activation, and to better understand the kinetics of these coordinated, parallel signaling processes in health and disease [1], we developed a robust sensor system for the simultaneous detection of DAG and Ca2+.

Several genetically encoded, fluorescent DAG sensors have been described. The simplest of these are composed of a green FP fused to the C1 domain of a conventional PKC [2]–[4]. This C1 domain translocates to the membrane and binds DAG when it is generated, so the physical translocation of the fluorescent protein, the membrane localization of the fluorescence, becomes the measurement of DAG signaling. The limitation of this approach is that it is not very quantitative, and it requires high resolution optical imaging, or TIRF illumination, to detect the intracellular translocation event. More recently, a sensor was created in which Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) efficiency between two different FPs changes in response to elevated levels of DAG [5]–[7]. Like the translocation sensors, this probe is useful in high resolution microscopy, but the changes in emission ratio of the donor and acceptor FPs upon sensor activation are relatively small.

Currently, the FP-based Ca2+ sensors GCaMP3 [8], G-GECO, and R-GECO [9] are the most robust class of genetically encoded fluorescent tools. These are the result of many years of of optimization in multiple research groups. Members of this class of sensors are constructed from a single circularly permuted fluorescent protein with calcium-dependent binding partners attached to the new termini. The crystal structure of one of these single FP-based sensors revealed that the binding partners cause a change in fluorescence intensity by opening and closing a hole in the protein β-barrel in close proximity to the chromophore [8]. Mutations that better occlude the hole in the Ca2+ bound state produced an even better Ca2+ sensor GCaMP3, which was in turn improved upon to create G-GECO and eventually, R-GECO.

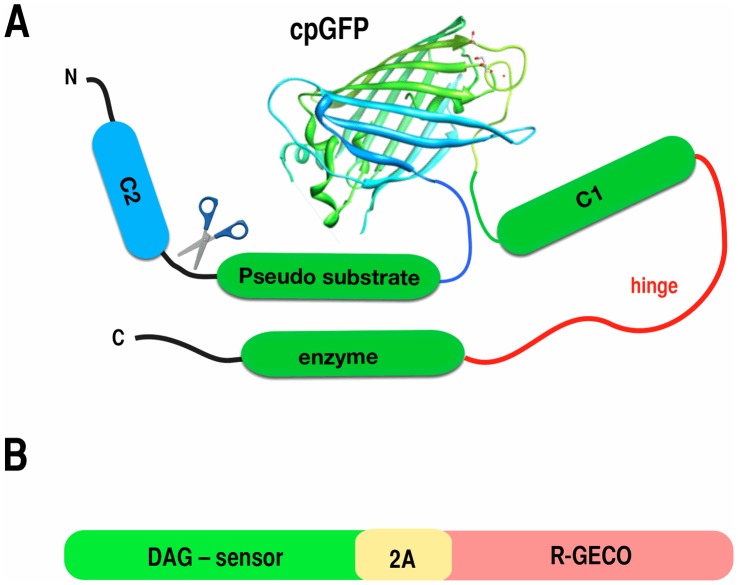

To determine whether a conceptually analogous sensor could be made for DAG, we created a variety of fusions that placed the circularly permuted green FP from G-GECO1 between the pseudo substrate domain and the C1 domain, or the hinge region, of the PKC isoform PKCδ (Figure 1). The C2 domain of PKCδ is not responsive to Ca2+ [10], and the C1 domain has a high affinity for DAG [11]. Reasoning that DAG binding to the C1 domain separates the pseudo substrate from the enzyme, we positioned the circularly permuted FP in portions of the PKCδ that could conceivably undergo large conformational alterations following DAG binding.

Figure 1. Sensor design.

(A) To create potential DAG sensors, we inserted the cpGFP from G-GECO into the region interconnecting the pseudo substrate and the C1 domain, or in the hinge that connects the C1 domain with the enzyme (red). Some constructs were created with the entire PKCδ, in others the C2 domain was removed. (B) To pair the Upward or Downward DAG sensors with R-GECO, we connected the two coding regions, in frame, with an intervening 2A peptide sequence of 17 amino acids.

Methods

Plasmid/Sensor Construction

Small changes in the exact fusion sites and linker composition can make large differences in the response properties of sensors based on circularly permuted FPs [12], so we created an initial test set of 64 fusion proteins (table 1) in which we systematically adjusted the position of the fusion site and/or removed the C2 domain. Sixty four different prototypes of a DAG sensor were created by fusing a circularly permuted green FP from G-GECO to 30 different positions within the novel PKCδ isoform. PCR amplification was used to generate fragments of PKCδ the coding region for the cpEGFP of G-GECO. Different combinations of PKC fragments were then paired with the cpEGFP amplicon and cloned into a modified version of the mammalian expression vector pcDNA3.1 using the In-Fusion Cloning system (Clontech Laboratories Inc, Mountain View, CA). The pcDNA3.1 vector was obtained from Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY). Thirty two of the prototypes involved inserting the cpEGFP into the full length PKCδ, an additional 32 constructs were created in which the N-terminal region of PKCδ containing the C2 domain was deleted.

Table 1. Summary of constructs created and tested.

| Sensor | FP position | Truncation site | Deletion | Sensor | FP position | Truncation site | Deletion |

| PcpG1 | C280 | PcpG16 2B | D217 | L122 | |||

| PcpG2 | I282 | PcpG17 2A | N158 | L91 | |||

| PcpG3 | L286 | Upward DAG | N158 | L122 | |||

| PcpG4 | A290 | PcpG17 2C | N158 | L106 | |||

| PcpG5 | Q296 | PcpG17 2D | N158 | Q129 | |||

| PcpG6 | S302 | PcpG17 2A | N158 | K138 | |||

| PcpG7 | E308 | PcpG18 2B | K157 | L122 | |||

| PcpG8 | Y313 | PcpG19 2B | I156 | L122 | |||

| PcpG9 | T320 | PcpG20 2B | Y155 | L122 | |||

| PcpG10 | E325 | PcpG21 2B | H154 | L122 | |||

| PcpG11 | G332 | PcpG22 2B | I153 | L122 | |||

| PcpG12 | I337 | Upward DAG | K152 | L122 | |||

| PcpG13 | K343 | PcpG24 2B | H159 | L122 | |||

| PcpG14 | N348 | PcpG25 2B | E160 | L122 | |||

| PcpG15 | Y448 | PcpG26 2B | F161 | L122 | |||

| PcpG16 | D217 | PcpG27 2B | I162 | L122 | |||

| PcpG17 | N158 | PcpG28 2B | A163 | L122 | |||

| PcpG1 2B | C280 | L122 | PcpG29 2B | T164 | L122 | ||

| PcpG2 2B | I282 | L122 | PcpG30 2B | E134 | L122 | ||

| PcpG3 2B | L286 | L122 | PcpG1-2 | C280 | G281-I282 | ||

| PcpG4 2B | A290 | L122 | PcpG1-3 | C280 | G281-L286 | ||

| PcpG5 2B | Q296 | L122 | PcpG1-4 | C280 | G281-A290 | ||

| PcpG6 2B | S302 | L122 | PcpG1-5 | C280 | G281-Q296 | ||

| PcpG7 2B | E308 | L122 | PcpG1-6 | C280 | G281-S302 | ||

| PcpG8 2B | Y313 | L122 | PcpG1-7 | C280 | G281-E308 | ||

| PcpG9 2B | T320 | L122 | PcpG1-8 | C280 | G281-Y313 | ||

| PcpG10 2B | E325 | L122 | PcpG1-9 | C280 | G281-T320 | ||

| PcpG11 2B | G332 | L122 | PcpG1-10 | C280 | G281-E325 | ||

| PcpG12 2B | I337 | L122 | PcpG1-11 | C280 | G281-G332 | ||

| PcpG13 2B | K343 | L122 | PcpG1-12 | C280 | G281-I337 | ||

| PcpG14 2B | N348 | L122 | PcpG1-13 | C280 | G281-K343 | ||

| PcpG15 2B | Y448 | L122 | PcpG1-14 | C280 | G281-N348 |

The sequence encoding the circularly permuted fluorescent protein was inserted into the PKCδcoding region such that fusions occurred just following the amino acid in PKCδ listed. The N-terminus of PKCδ was truncated in some constructs, with the translation start beginning just before the amino acid listed.

Cell Culture and Transfection

Cells were cultured in EMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and Penicillin-Streptomycin at 37°C in 5% CO2. HEK 293 cells and Eagle’s Minimum Essential Medium (EMEM) were purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA). Prior to cell seeding, 96-well glass-bottom plates were coated with Poly-D-Lysine. Cells were seeded on the plates, transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 Transfection Reagent according to the manafacturer’s protocol, and incubated for 48 hours at 37°C in 5% CO2. 60 ng of sensor DNA was co-transfected with 40 ng of human M1 muscarinic receptor per well. Pen-Strep liquid and Lipofectamine 2000 were obtained from Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY). Poly-D-Lysine was purchased from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburg, PA).

Cell Imaging

Prior to fluorescence imaging, EMEM culture medium was replaced with 1X DPBS. Experiments were performed on a Zeiss Axiovert S100TV inverted microscope fitted with computer controlled excitation/emission filter wheels, shutters, and a Qimaging Retiga Exi ccd camera (Surrey, BC Canada). Cells were imaged live at 25°C using the 10X objective lens. 480±20 nm excitation and and 535±25 nm emission filters were used resolve the green fluorescence from the DAG sensors, and 572±20 nm and 630±30 nm filters were used to collect the R-GECO signal. Cells were analyzed for increases or decreases in fluorescence intensity upon addition of Carbachol, PDBU, or Ionomycin. To analyze the image stacks, background fluorescence was defined as a region of the image that contained no cells. The average value of this region was subtracted frame by frame from the measurements of the mean pixel values of the fluorescent cells. Cellular fluorescence data was plotted and analyzed with IGOR software (Wavemetrics, Oswego Ore.).

Materials

Phorbol 12, 13-dibutyrate (PDBU), Carbachol, and Ionomycin were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Corp (St. Louis, MO). Dulbecco’s PBS/Modified was purchased from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburg, PA).

Results

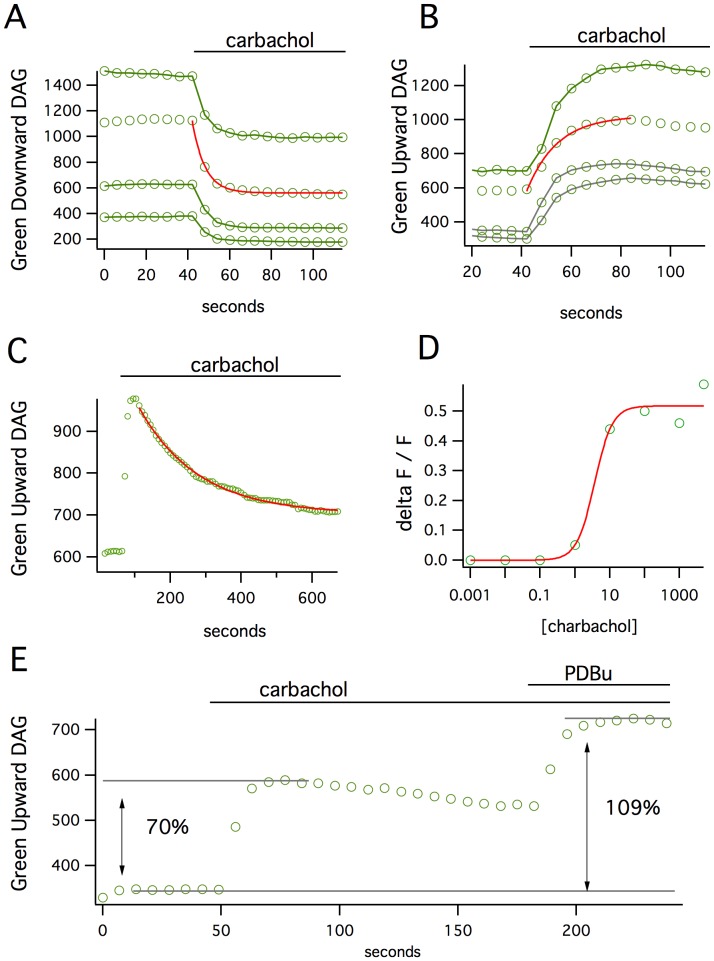

To test the functionality of the 64 fusion proteins, we co-expressed each construct with the M1 acetylcholine receptor, which couples to the Gq signaling pathway, in HEK 293 cells. Application of the agonist carbachol produced no change in fluorescence for most of the constructs, though many of the fusion proteins did translocate to the plasma membrane in response to activation. Of the 10 sensors that did produce a significant change in fluorescence, one sensor produced a remarkable 40% decrease in fluorescence (Green Downward DAG, Figure 2A). A different sensor, in which the FP insertion site was just 6 amino acids away from the first, produced a 45% increase in fluorescence (Green Upward DAG, Figure 2B). These changes were easily detected in time-lapse imaging and occurred in all transfected cells with remarkably little cell to cell variability. The increase or decrease of the signal produced by the Upward or Downward DAG, respectively, was reasonably fit by a single exponential function with a time constant of 6 to 11 seconds. The signals then returned to baseline quite slowly (τ – 170 seconds, Figure 2C).

Figure 2. The responses of Green Downward DAG and Upward DAG sensors.

(A) Carbachol stimulation of the M1 receptor on cells expressing the Downward DAG sensor produces a 40% loss in fluorescence that occurs over ∼15 seconds (mean fluorescence over time of 4 cells). (B) The Upward DAG sensor shows a fluorescence increase of 45% over a similar time scale. (C) The signals generated by either sensor return to baseline quite slowly. (D) The apparent EC50 for carbacol-stimulated Upward DAG response is 3.5 uM. (E) The carbachol stimulation does not appear to activate all of the sensor pool in the cell since direct activation of the sensors with a subsequent application of PDBu produces an additional increase in fluorescence.

Both the Upward and Downward DAG sensors showed robust changes in fluorescence that are an order of magnitude larger than the previously reported, FRET-based DAG sensors. We suspected that our measurements of the maximal sensor responses might be an underestimate. In transient expression it is possible to produce high concentrations of the protein-based sensor than the analyte itself [13]. To test whether this might be occurring, cells were first stimulated with carbachol and then the phorbol ester PDBu was added to directly activate any remaining sensors within the cell (Figure 2D). This produced an additional doubling of the change in intensity, indicating that not all of the sensors in a given cell were activated by the carbachol, and that larger changes in fluorescence might be seen at lower intracellular concentrations of sensor, such as in the context of stable cell lines or transgenic animals.

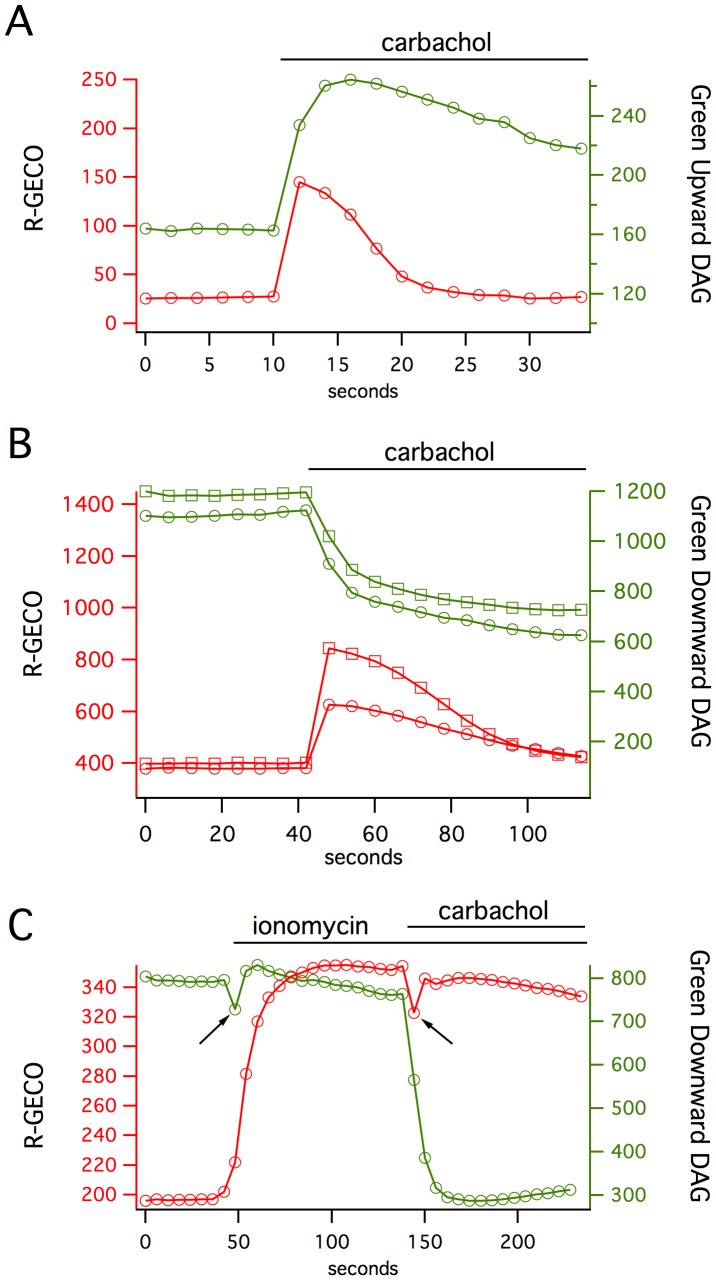

One advantage of sensors constructed with single FPs is that they use less of the visible spectrum than FRET-based systems. This means that different sensors of different colors can be combined to monitor multiple signaling pathways simultaneously. To multiplex the expression of the DAG sensor with a Ca2+ sensor, we fused the coding regions of Green Upward or Green Downward DAG to a cotranslational self-cleaving 2A [14] peptide followed by R-GECO1 [9] (Figure 1B) to produce stoichiometrically balanced proportions of the two sensors. R-GECO1 is a red fluorescent Ca2+ sensor based on a circularly permuted red fluorescent protein mApple [15] with excitation and emission properties that are easily distinguished from the green fluorescent DAG sensors.

In cells transiently expressing this dual sensor system, stimulation of the M1 receptor produces a fast rise in intracellular Ca2+, as detected by changes in the red fluorescence channel, and a much slower rise in DAG, as detected in the green fluorescence channel (Figure 3). The Ca2+ returns to baseline in ∼20 seconds, while the DAG levels remain high for 200–300 seconds. This occurs for either the Downward or Upward DAG sensors paired with R-GECO1. To test for the independence of the signals being detected by these sensors, we increased intracellular Ca2+ by applying ionomycin. This triggers a robust R-GECO1 response and no detectable change in the DAG sensor, which was subsequently activated by the addition of PDBu (Figure 3C).

Figure 3. Pairing the Green Upward and Downward DAG sensors with R-GECO makes it possible to simultaneously measure DAG and Ca2+ signaling in single cells.

(A) The Green Upward DAG sensor response is considerably slower than the red Ca2+ response in response to carbachol stimulation of the M1 receptor. (B) Similar kinetics occur with the Downward DAG sensor. (C) The two sensors can be activated independently: ionomycin, which should raise intracellular Ca2+ without affecting DAG levels produces a change in R-GECO but not Downward DAG, while the subsequent addition of PDBu activates Downward DAG (arrows indicate stimulus artifact).

Discussion

The development of these DAG sensors provides a new avenue for obtaining insights into PLC signaling. Measuring DAG and Ca2+ signaling in single cells reveals that PLC signaling appears to operate in two different time zones. Following stimulation, both Ca2+ and DAG are elevated for about 10 seconds. This time zone should be when conventional protein kinase C (cPKC) isoforms are active since they require the coordinated binding of both the C1 and C2 domains. The novel PKC isoforms (nPKC), however, should be active over a much longer time zone since elevated DAG levels are sufficient to activate the high affinity C1 domains of the nPKCs [4]. These differences in the kinetics of the signaling pathway responses have been seen with translocation-based sensors in the past [2], but they become more compelling when they can be measured at the same time in the same cell. One can imagine how this enables PLC signaling to affect different targets in different time scales.

To fully understand cell signaling, we will need probes to measure the dynamics of each step in the pathway. Protein-based sensors have made it possible to use protein domains that are exquisitely tuned to detect second messengers in physiological ranges of concentration. Recent advances in the creation of Ca2+ sensors, and cGMP [16], have shown that fusions with circularly permuted FPs can produce robust sensors that far exceed FRET-based probes. Here we show that this design is extensible and valuable for robust detection of the crucial second messenger DAG.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the NIMH - National Institue of Mental Health (1R43MH096670- 01A1), and The Montana Board of Research and Commercialization #11-37 to A.M.Q., and by Alberta Innovates (Y.Z.), Canadian Institutes of Health Research (R.E.C), and Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (R.E.C.). R.E.C. holds a Tier II Canada Research Chair in Bioanalytical Chemistry.

References

- 1. Erion DM, Shulman GI (2010) Diacylglycerol-mediated insulin resistance. Nat Med 16: 400–402 doi:10.1038/nm0410-400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Oancea E, Meyer T (1998) Protein kinase C as a molecular machine for decoding calcium and diacylglycerol signals. Cell 95: 307–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Oancea E, Teruel MN, Quest AFG, Meyer T (1998) Green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged cysteine-rich domains from protein kinase C as fluorescent indicators for diacylglycerol signaling in living cells. J Cell Biol 140: 485–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dries DR, Gallegos LL, Newton AC (2007) A single residue in the C1 domain sensitizes novel protein kinase C isoforms to cellular diacylglycerol production. J Biol Chem 282: 826–830 doi:10.1074/jbc.C600268200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sato M, Ueda Y, Umezawa Y (2006) Imaging diacylglycerol dynamics at organelle membranes. Nature Methods 3: 797–799 doi:10.1038/nmeth930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Violin JD, Zhang J, Tsien RY, Newton AC (2003) A genetically encoded fluorescent reporter reveals oscillatory phosphorylation by protein kinase C. J Cell Biol. 161: 899–909 doi:10.1083/jcb.200302125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gallegos LL, Kunkel MT, Newton AC (2006) Targeting protein kinase C activity reporter to discrete intracellular regions reveals spatiotemporal differences in agonist-dependent signaling. J Biol Chem 281: 30947–30956 doi:10.1074/jbc.M603741200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Akerboom J, Rivera JDV, Guilbe MMR, Malave ECA, Hernandez HH, et al. (2008) Crystal Structures of the GCaMP Calcium Sensor Reveal the Mechanism of Fluorescence Signal Change and Aid Rational Design. Journal of Biological Chemistry 284: 6455–6464 doi:10.1074/jbc.M807657200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao Y, Araki S, Wu J, Teramoto T, Chang YF, et al.. (2011) An Expanded Palette of Genetically Encoded Ca2+ Indicators. Science. doi:10.1126/science.1208592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10. Newton AC (2010) Protein kinase C: poised to signal. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology And Metabolism 298: E395–E402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Giorgione JR, Lin J-H, McCammon JA, Newton AC (2006) Increased membrane affinity of the C1 domain of protein kinase Cdelta compensates for the lack of involvement of its C2 domain in membrane recruitment. J Biol Chem 281: 1660–1669 doi:10.1074/jbc.M510251200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nakai J, Ohkura M, Imoto K (2001) A high signal-to-noise Ca(2+) probe composed of a single green fluorescent protein. Nature Biotechnology 19: 137–141 doi:10.1038/84397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Falkenburger BH, Jensen JB, Hille B (2010) Kinetics of M1 muscarinic receptor and G protein signaling to phospholipase C in living cells. J Gen Physiol 135: 81–97 doi:10.1085/jgp.200910344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Szymczak AL, Workman CJ, Wang Y, Vignali KM, Dilioglou S, et al. (2004) Correction of multi-gene deficiency in vivo using a single “self-cleaving” 2A peptide-based retroviral vector. Nature Biotechnology 22: 589–594 doi:10.1038/nbt957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shaner NC, Campbell RE, Steinbach PA, Giepmans BNG, Palmer AE, et al. (2004) Improved monomeric red, orange and yellow fluorescent proteins derived from Discosoma sp. red fluorescent protein. Nature Biotechnology 22: 1567–1572 doi:10.1038/nbt1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nausch LWM, Ledoux J, Bonev AD, Nelson MT, Dostmann WR (2008) Differential patterning of cGMP in vascular smooth muscle cells revealed by single GFP-linked biosensors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 105: 365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]