Brief periods of ischemia protect the heart from subsequent prolonged episodes of ischemia, reducing infarct size. This effect, originally described in dog hearts by Murry and colleagues (1) in 1986, is called ischemic preconditioning. Ischemic preconditioning protects other organs, such as the brain, skeletal muscle, and intestine, and it occurs in other species as well, such as rodents, rabbits, and humans. Patients who have angina shortly before a heart attack have smaller infarcts than patients without prior angina. Although the pathways of preconditioning are partially understood, important gaps remain in our understanding of the mechanisms that protect the heart. In particular, the identity of the molecular effector of preconditioning has been a mystery.

Now, Bolli and colleagues (2) on page 11507 of this issue show that nitric oxide (NO) and the inducible NO synthase (iNOS or NOS2) mediate the beneficial effects of ischemia. Bolli and colleagues first confirm that short bursts of ischemia protect the heart in mice, as expected: ischemic preconditioning reduces subsequent myocardial infarction size by 66% in wild-type mice. Surprisingly, they next find that preconditioning has no protective effect on the hearts of iNOS null animals. This finding is dramatic; lack of iNOS completely eliminates preconditioning. Why?

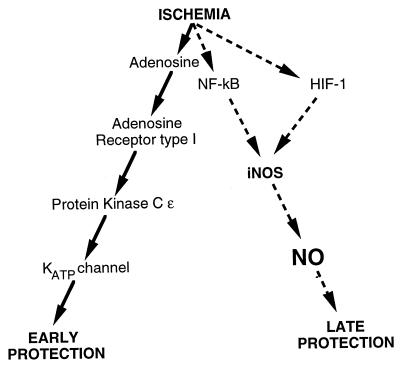

First, some background. Preconditioning limits infarct size both soon after preconditioning (the early phase or first window of protection) and long after preconditioning (the delayed phase or second window; ref. 3). Major components of the early preconditioning pathway are well known (Fig. 1). Ischemia induces the release of adenosine, which binds to the adenosine receptor type I, activating a signal transduction pathway that includes phospholipase C, PIP2, and protein kinase C ɛ. Protein kinase C ɛ and other protein kinases then activate ATP-sensitive potassium channels of the mitochondria. Precisely how the mitochondria then protect cells is unknown, but the process may involve sequestration of calcium. Although we know a good deal about how the heart is protected soon after ischemia, we know much less about the late phase of protection.

Figure 1.

Molecular pathways of ischemic preconditioning. Ischemia triggers an early phase of protection against further episodes of ischemia. The early phase, depicted on the left, begins when ischemia induces the release of adenosine, which binds to the adenosine receptor type I. An intracellular signal transduction pathway is activated by hydrolysis of PIP2, which activates protein kinase C and other protein kinases. Mitochondrial ATP-sensitive potassium channels are then activated, which protect the myocardium by unknown mechanisms. The late phase of protection, depicted on the right, begins when ischemia activates unknown transcription factors, possibly NF-κB and hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1), which induce iNOS expression, leading to NO production and then protection of the heart 24–72 h after ischemia.

Over 20 years ago, oxygen radicals were proposed as a mediator of the late phase of ischemic preconditioning, but their role is still controversial. Some studies show that radicals such as superoxide or hydrogen peroxide can reduce infarct size and improve endothelial function after ischemia (4–6). Other studies show the exact opposite: oxygen radicals are deleterious, activating the apoptosis pathway, increasing infarct size, and causing endothelial cell dysfunction (7). Still others suggest that oxygen radicals play no role at all in preconditioning (8). Perhaps some of these contradictory data can be resolved by postulating that brief periods of ischemia trigger the production of low levels of reactive oxygen species, which induce antioxidant defenses that can reduce subsequent ischemic damage; however, longer periods of ischemia generate higher levels of reactive oxygen species that are themselves cytotoxic.

The role of NO in ischemia is also controversial. For example, depending on the experimental model studied, NO seems to reduce pure ischemic damage in vivo but exacerbate ischemic damage in vitro. In contrast, NO apparently plays no role in mediating the early phase of ischemic preconditioning (9). However, some studies completed before the current one suggested that NO mediates the later phase of preconditioning. For example, exogenous NO donors can mimic the late effects of preconditioning, reducing infarct size (10). Furthermore, inhibition of NOS increases infarct size (11). Similar studies confirm that NO mediates protection against ischemia in other organs as well (12, 13). However, NO can be synthesized by any of the three NOS isoforms, neuronal NOS (nNOS or NOS1), endothelial NOS (eNOS or NOS3), or iNOS; and early studies with nonspecific NOS inhibitors could not identify the source of NO produced during preconditioning. The current study by Bolli and colleagues (2) confirms the protective role of NO and identifies iNOS as its source.

How does ischemia induce iNOS expression? Ischemic preconditioning triggers the mitogen activated protein kinase pathway, leading to activation of NF-κB (6). NF-κB in combination with other transcription factors can bind to specific sites in the iNOS regulatory region, physically bending the DNA and activating transcription of iNOS (14–16). Thus, ischemia might induce iNOS expression by activation of NF-κB.

However, recent data suggest that another transcription factor regulated by oxygen levels can also trigger iNOS expression. The hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1), a heterodimeric transcription factor discovered by Semenza (17), induces the expression of a set of genes in response to hypoxia. Activated by hypoxia, HIF-1 translocates from the cytoplasm into the nucleus and interacts with an HIF-1 response element in the regulatory region of a variety of genes, activating their transcription. The iNOS promoter region contains an HIF-1 response element, and several groups recently have shown that hypoxia activates iNOS expression and NO production (18, 19). Thus, HIF-1 might play a critical role in protecting organs from ischemic damage, in part by stimulating iNOS expression and NO production.

NO might protect myocytes from ischemic death by a variety of mechanisms. Hypoxia leads to cardiac myocyte apoptosis by activating caspases, cysteine proteases that are part of the intracellular apoptosis pathway. NO can inactivate caspases by nitrosylating the cysteine residue in the active site (20–22). Thus, ischemia might induce iNOS and NO synthesis, which in turn might inhibit caspases and decrease cardiac myocyte apoptosis, reducing infarct size.

Another possible hypothesis is that NO could protect the myocardium by regulating mitochondrial respiration. NO interacts with iron-sulfur clusters and can inhibit ubiquinone oxidoreductase and succinate oxidoreductase, both of which are mitochondrial enzymes with iron-sulfur clusters (23–25). Hintze and colleagues (26) have shown that NO can regulate mitochondrial respiration, reducing myocardial oxygen consumption. Ischemic induction of NO synthesis might therefore protect cardiac myocytes from subsequent ischemia by inhibiting mitochondria respiratory enzymes.

Another mitochondrial target of NO is an ion channel. ATP-sensitive potassium channels on mitochondria play a critical role in the signal transduction pathway of early preconditioning. Marban and colleagues (27) recently have shown that NO can activate these channels directly. Perhaps NO produced by iNOS protects the heart in part by maintaining these mitochondria channels in an open position. ATP-sensitive potassium channels play a role in early preconditioning, and NO plays a role in late preconditioning; thus, this intriguing hypothesis links the early and late preconditioning pathways through the actions of NO.

Unanswered questions remain. Can other isoforms of NOS participate in preconditioning? Endothelial NOS (eNOS or NOS3) is present, not only in the cardiac vasculature, but also in cardiac myocytes themselves. Neuronal NOS (nNOS or NOS1) is expressed at low levels in the conduction system of the heart. Hypoxia increases the expression both of eNOS and nNOS. Perhaps NO derived from eNOS also mediates the early or late phase of preconditioning in the heart. Although large amounts of NO synthesized by nNOS is neurotoxic after strokes (28), transient activation of nNOS might protect the brain.

Which cells in the heart express iNOS after ischemia? The predominant cells of the heart are cardiac myocytes, fibroblasts, and endothelial cells. Hypoxia alone can induce iNOS expression in endothelial cells, but additional stimuli are necessary for hypoxic induction of iNOS in other cells (18, 19). For example, hypoxia and interferon are both required to induce iNOS in macrophages. Perhaps hypoxia induces iNOS in select subpopulations of cardiac cells but not others.

The observation by Bolli’s group has important clinical implications as well. If NO can protect the heart from ischemic events, then exogenous NO may benefit patients at risk for myocardial infarction. Drugs such as isosorbide dinitrate or nitroglycerin that generate NO are commonly prescribed for patients with angina. Nitrates given to unstable patients before a myocardial infarction might precondition their hearts and reduce the severity of an infarction. Although large clinical trials have shown that nitrates have little effect given to patients after myocardial infarction, perhaps nitrates administered to high-risk patients might reduce the severity of subsequent infarction (29).

Footnotes

The companion to this Commentary begins on page 11507.

References

- 1.Murry C E, Jennings R B, Reimer K A. Circulation. 1986;74:1124–1136. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.74.5.1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guo Y, Jones W K, Xuan Y-T, Tang X-L, Bao W, Wu W-J, Han H, Laubach V E, Ping P, Yang Z, Qiu Y, Bolli R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:11507–11512. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bolli R, Marban E. Physiol Rev. 1999;79:609–634. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.2.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tritto I, D’Andrea D, Eramo N, Scognamiglio A, De Simone C, Violante A, Esposito A, Chiariello M, Ambrosio G. Circ Res. 1997;80:743–748. doi: 10.1161/01.res.80.5.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baines C P, Goto M, Downey J M. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1997;29:207–216. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1996.0265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maulik N, Sato M, Price B D, Das D K. FEBS Lett. 1998;429:365–369. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00632-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beresewicz A, Czarnowska E, Maczewski M. Mol Cell Biochem. 1998;186:87–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tang X L, Qiu Y, Turrens J F, Sun J Z, Bolli R. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:H1651–H1657. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.273.4.H1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weselcouch E O, Baird A J, Sleph P, Grover G J. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:H242–H249. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.268.1.H242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takano H, Tang X L, Qiu Y, Guo Y, French B A, Bolli R. Circ Res. 1998;83:73–84. doi: 10.1161/01.res.83.1.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bolli R, Bhatti Z A, Tang X L, Qiu Y, Zhang Q, Guo Y, Jadoon A K. Circ Res. 1997;81:42–52. doi: 10.1161/01.res.81.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gidday J M, Shah A R, Maceren R G, Wang Q, Pelligrino D A, Holtzman D M, Park T S. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1999;19:331–340. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199903000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peralta C, Closa D, Hotter G, Gelpi E, Prats N, Rosello-Catafau J. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;229:264–270. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xie Q W, Kashiwabara Y, Nathan C. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:4705–4708. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kamijo R, Harada H, Matsuyama T, Bosland M, Gerecitano J, Shapiro D, Le J, Koh S I, Kimura T, Green S J. Science. 1994;263:1612–1615. doi: 10.1126/science.7510419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saura M, Zaragoza C, Bao C, McMillan A, Lowenstein C J. J Mol Biol. 1999;289:459–471. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Semenza G L. Cell. 1999;98:281–284. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81957-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Melillo G, Taylor L S, Brooks A, Musso T, Cox G W, Varesio L. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:12236–12243. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.18.12236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Palmer L A, Semenza G L, Stoler M H, Johns R A. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:L212–L219. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1998.274.2.L212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Melino G, Bernassola F, Knight R A, Corasaniti M T, Nistico G, Finazzi-Agro A. Nature (London) 1997;388:432–433. doi: 10.1038/41237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dimmeler S, Haendeler J, Nehls M, Zeiher A M. J Exp Med. 1997;185:601–607. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.4.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vegh A, Papp J G, Szekeres L, Parratt J R. Br J Pharmacol. 1993;110:18–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13764.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lizasoain I, Moro M A, Knowles R G, Darley-Usmar V, Moncada S. Biochem J. 1996;314:877–880. doi: 10.1042/bj3140877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cleeter M W, Cooper J M, Darley-Usmar V M, Moncada S, Schapira A H. FEBS Lett. 1994;345:50–54. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00424-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stadler J, Billiar T R, Curran R D, Stuehr D J, Ochoa J B, Simmons R L. Am J Physiol. 1991;260:C910–C916. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1991.260.5.C910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Loke K E, McConnell P I, Tuzman J M, Shesely E G, Smith C J, Stackpole C J, Thompson C I, Kaley G, Wolin M S, Hintze T H. Circ Res. 1999;84:840–845. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.7.840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sasaki, N., Sato, T., O’Rourke, B. & Marban, E. (1999) Circulation, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Dawson T M, Dawson V L, Snyder S H. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1994;738:76–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb21792.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.ISIS-4 Study Group. Lancet. 1995;345:669–685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]