Abstract

Limited empirical evidence concerning the efficacy of substance abuse treatments among African Americans reduces opportunities to evaluate and improve program efficacy. The current study, conducted as a secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial conducted by the Clinical Trials Network of the National Institute of Drug Abuse, addressed this knowledge gap by examining the efficacy of motivational enhancement therapy (MET) compared with counseling as usual (CAU) among 194 African American adults seeking outpatient substance abuse treatment at 5 participating sites. The findings revealed higher retention rates among women in MET than in CAU during the initial 12 weeks of the 16-week study. Men in MET and CAU did not differ in retention. However, MET participants self-reported more drug-using days per week than participants in CAU. Implications for future substance abuse treatment research with African Americans are discussed.

Keywords: motivational enhancement therapy, substance abuse, African Americans, retention, females

Substance abuse, a major public health concern in the United States, is significantly associated with crime, homelessness, mental illness, and even death among individuals of all ages, socioeconomic groups, and races (Kennedy, Efremova, Frazier, & Saba, 1999; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2009). Although generally pervasive, the adverse consequences of drug use are reportedly greater in the African American community than in other groups. African American substance abusers experience more negative health and social consequences (Strycker, Duncan, & Pickering, 2003), a higher risk of HIV transmission (Galea & Rudenstein, 2005), and more substance abuse-related legal involvement (Shillington & Clapp, 2003). In addition, African Americans, although only 12% of the population, represented 21% of admissions to publicly funded substance abuse treatment in 2006 (SAMHSA, 2008). Unfortunately, the disproportionate admission rates among African Americans are coupled with lower retention rates (McCaul, Svikis, & Moore, 2001).

Many studies suggest that ethnic minority groups have lower retention, higher dropout rates, and poorer compliance in substance abuse treatment (Agosti, Nunes, & Ocepeck-Wilson, 1996; Longshore, 1999; McCaul et al., 2001; Milligan, Nich, & Carroll, 2004; Sue, 1988). Increasing retention rates is important because research suggests that length of time in treatment is one of the best predictors of better outcomes (Milligan et al., 2004; Simpson, 1981; Simpson, Joe, & Rowan-Szal, 1997). Therefore, retention is an important first step for potentially reducing the disproportionate adverse consequences due to substance abuse among African Americans (McCaul et al., 2001). The lower number of African Americans describing substance abuse treatment as effective may partially explain the lower retention rates (Heron, Twomey, Jacobs, & Kaslow, 1997; Jackson, Stephens, & Smith, 1997).

Motivational enhancement therapy (MET), a widely used brief substance use intervention, offers one low-cost potential approach for addressing the need for more effective treatments for African Americans. MET fits within the framework of stages of change theory (Prochaska, DiClemente, & Norcross, 1992), with particular emphasis on personal assessment feedback within the overall clinical style of motivational interviewing (MI), a “client-centered, directive method for enhancing intrinsic motivation to change by exploring and resolving ambivalence” (Miller & Rollnick, 2002, p. 25). The basic MI principles are expressing empathy, developing discrepancy, avoiding argumentation, rolling with resistance, and supporting self-efficacy. MI/MET consists of two phases: building motivation for change and strengthening commitment to change (Miller & Rollnick, 2002).1 Several recent meta-analyses support the efficacy of MI/MET for treating excessive drinking (Burke, Arkowitz, & Menchola, 2003; Vasilaki, Hosier, & Cox, 2006) and substance use (Hettema, Steele, & Miller, 2005; Lundahl, Kunz, Brownell, Tollefson, & Burke, 2010). Moreover, MI/MET has modest effects on smoking cessation (Hettema & Hendricks, 2010). However, some studies have found that MI/MET was no more effective than a comparison condition in improving retention (Ball et al., 2007; Mullins, Suarez, Ondersma, & Page, 2004) and urinalysis (Mullins et al., 2004) outcomes. Hettema et al. (2005) suggested that examining whether MI/MET works differently across ethnic groups and other participant characteristics (e.g., gender) might help explain the variability across studies.

Motivational Interviewing/Motivational Enhancement Therapy With African Americans

Although the research on MI/MET effectiveness among African Americans is limited, the results of some studies are promising (Montgomery, Burlew, Wilson, & Hall, in press). Moreover, one study actually suggests that MET improves retention among African Americans. Specifically, HIV-positive African American youth remained in HIV treatment longer when they participated in MI sessions delivered by a peer outreach worker (Naar-King, Outlaw, Green-Jones, Wright, & Parsons, 2009). Other findings revealed MI/MET effectiveness for increasing medication adherence among African Americans with hypertension (Ogedegbe et al., 2007) and increasing fruit and vegetable intake (Resnicow et al., 2001).

Few previous studies examined the effectiveness of MI/MET in reducing substance use among African Americans. Only six of the 72 studies in a recent meta-analysis of the MI literature (Hettema et al., 2005) had a majority (74% or higher) of participants who were African American and only one of the six assessed substance use (Longshore, Grills, & Annon, 1999). Longshore and Grills (2000) found that the African Americans in a culturally congruent version of an MI intervention (i.e., included traditional African American meals, a community peer, and a 15-min video clip of success stories from African Americans in recovery) were more likely than those in standard treatment to report abstinence from substance use (i.e., heroin, crack cocaine, and other cocaine) 1 year later. The need for targeted research on the effective elements of substance abuse treatments for African Americans is clearly evident.

Although research findings in this area are promising, several gaps exist in the literature. First, previous studies frequently combined ethnic minority groups into a single group and then compared ethnic minorities with nonminorities (Hettema et al., 2005). Such designs make it difficult to interpret whether the findings apply to some of the ethnic groups or all of them (Burlew, Feaster, Brecht, & Hubbard, 2009). More studies focusing exclusively on African Americans are needed. Second, studies examining MET outcomes specifically for African American substance users have only assessed culturally tailored versions of MET (Longshore & Grills, 2000) but not generic versions. However, many clinics serve diverse populations and only have limited resources to implement interventions developed for one specific ethnic group. Such clinics need to know when they can use generic versions effectively and when it is absolutely necessary to tailor the intervention because the intervention is not effective for the target group (Castro, Barrera, & Holleran-Steiker, 2010). Third, despite some promising findings, two meta-analyses (not limited to just substance abuse treatment studies) showed inconsistent findings about MET’s effectiveness with African Americans. Lundahl et al. (2010) reported a negative relationship between the number of African Americans in the sample and the overall mean effect size in their meta-analysis of 119 generic MI/MET interventions, whereas Hettema et al. (2005) found that generic versions of MI were more effective among ethnic minorities than Whites in a meta-analysis of 72 studies. These inconsistencies support the need for further research. Fourth, previous studies that failed to assess within-group differences ignored the heterogeneity among African Americans. One approach to addressing the heterogeneity problem is to examine treatment effects for specific subgroups of African Americans such as males and females (Burlew et al., 2009, in press; Castro et al., 2010; Greenfield et al., 2007). Analyses of the data within subgroups in substance abuse treatment research might help explain some of the inconsistent findings in the existing MI/MET literature and help determine MI/MET efficacy among African Americans.

The Clinical Trials Network (CTN) 0004 study (Motivational Enhancement Treatment to Improve Treatment Engagement and Outcome in Individuals Seeking Treatment for Substance Abuse; Carroll et al., 2001) of the National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA) provided an opportunity for a secondary analysis to address existing gaps (i.e., evaluating the efficacy of a generic version of MET in a sample of African American men and women) in African American outpatient substance abuse treatment research. In the original multisite clinical trial (Ball et al., 2007), 461 substance-abusing adults were randomized to receive either MET as an adjunct to counseling as usual (CAU) or CAU alone. CAU varied across sites, but typically consisted of a substance abuse assessment, case management, substance use counseling, and referrals to other community services, such as Alcoholic Anonymous.

The overall findings revealed no treatment differences in substance use or retention outcomes between MET and CAU participants (Ball et al., 2007). However, a growing number of substance use studies have revealed ethnic group differences in the outcomes of specific substance abuse interventions. For example, Winhusen et al. (2008) reported that the ethnic minorities in a MET intervention for pregnant substance users had better outcomes (i.e., decreased substance use) than the overall majority White sample. Therefore, as suggested by other research teams (Burlew et al., 2009), future research should examine rather than assume that the findings from the overall sample are applicable to the racial/ethnic minorities in the sample.

Current Study

The current study, a secondary analysis of the 194 African Americans in CTN 0004, evaluated the efficacy of MET on reducing primary substance use and increasing retention. It was hypothesized that (1) African Americans participants in MET would self-report less use of their primary substance than African Americans in CAU, and (2) African Americans in MET would achieve higher retention rates than African Americans in CAU. Separate analyses for men and women were also conducted.

Method

Participants

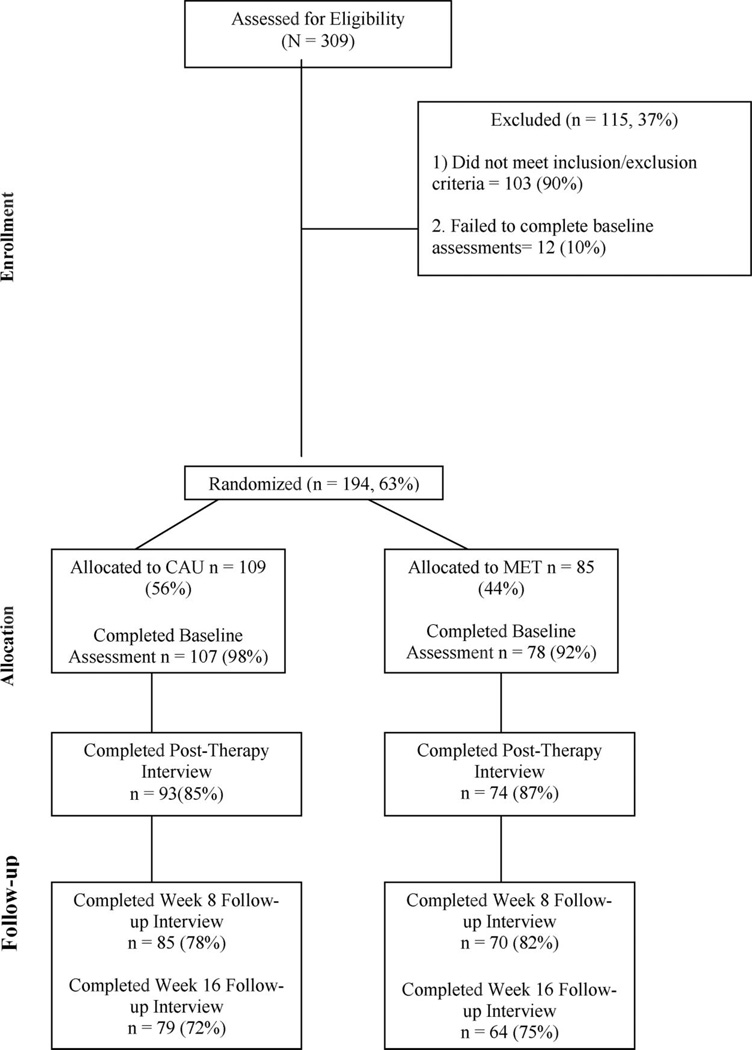

We assessed outcomes among the 194 African American participants in the CTN 0004 trial. Figure 1 outlines eligibility, enrollment, randomization, treatment, and follow-up rates for African American participants. The demographic information for the overall sample is available elsewhere (Ball et al., 2007). Eligible individuals were seeking outpatient treatment for any substance use disorder, had used substances within 28 days prior to the study, were 18 years of age or older, were willing to participate in the protocol, and were able to understand and provide written informed consent. Individuals too medically or psychiatrically unstable to participate in outpatient treatment and individuals seeking only detoxification, methadone maintenance treatment, or residential treatment were excluded.

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram of eligibility, enrollment, randomization, treatment, and follow-up rates. CAU = counseling as usual; MET = motivational enhancement therapy. Note. The highest number of participants providing data at any time point was recorded as the total n for each time point.

Participating community treatment programs (CTPs)

The five participating CTPs provided outpatient treatment in a non–methadone-maintenance setting. CTPs eligible for this protocol enrolled adequate numbers of new patients to meet the recruitment targets for the parent study (i.e., 100 participants per CTP, with approximately 50 participants per treatment group) and had at least six clinicians willing to participate in the protocol. The CTPs were affiliated with the following three regional research nodes of the NIDA CTN: the New England Node, the Delaware Valley Node, and the Pacific Region Node. Further information on the participating CTPs can be found in the publication by Ball et al. (2007).

Participating clinicians

Eligible clinicians were currently employed at the participating CTPs, were willing to use a manualized version of MET, were willing to accept an assignment to either MET or standard treatment, and were approved by the CTPs’ administrative/supervisory staff as appropriate for the study. Clinicians with prior MI/MET training were ineligible. Further information on staff eligibility criteria and training plans can be found in the CTN 0004 protocol (Carroll et al., 2001).

Measures

Substance use calendar (SUC)

The first outcome measure, substance use (i.e., number of self-reported days of primary substance use per week for each of the 16 study weeks), was assessed using the SUC. The SUC is a self-report substance use (marijuana, cocaine, alcohol, methamphetamine, benzodiazepines, opioids, and other illicit substances) measure recording daily use. Participants reported their primary substance use at baseline. The number of days per week of primary substance use reported on the SUC was used to assess treatment outcomes over time. The SUC is adapted from the Form-90 and Timeline Followback (TLFB), two widely used self-report measures of substance use in calendar form (i.e., day to day). The Form-90 (Miller & DelBoca, 1994) and TLFB (Ehrman & Robbins, 1994; Fals-Stewart, O’Farrell, Freitas, McFarlin, & Rutigliano, 2000; Sobell & Sobell, 1992) demonstrated good reliability and validity in assessing substance use.

Client disposition—End of trial status form

The second outcome measure, retention (i.e., the number of days between the day of enrollment and the last day the participant received services at the clinic during the 16 study weeks), was assessed with the client disposition—end of trial status form. The form includes information on the date of the last treatment session.

Demographics

A demographic form was used to collect data such as age, frequency of use, ethnicity, primary substance type at baseline, and other demographic variables.

Procedure

The research team identified and referred individuals seeking outpatient substance abuse treatment at each of the participating five CTPs to a research assistant. Research assistants collected baseline information from eligible individuals providing written consent. Following a baseline assessment, participants were randomly assigned via urn randomization to receive either three sessions of CAU or MET. The variables used in the original study for urn randomization included gender, race, primary substance, referral type (mandated or voluntary), and employment status (Stout, Wirtz, Carbonari, & DelBoca, 1994). After randomization, participants began either three MET sessions in the active phase and CAU in the follow-up phase (i.e., 12 weeks following the active phase) or three CAU sessions in the active phase and additional CAU sessions in the follow-up phase. During the 4-week active phase, research assistants attempted weekly meetings with participants to collect information on substance use and treatment use. Research assistants also collected follow-up substance use and treatment use data 8 and 16 weeks after enrollment.

Counseling as usual

Participants attended three sessions (45–55 min each) during the 4-week active phase as an adjunct to standard treatment. Clinicians “collected information on substance use and psychosocial functioning, explained treatment program requirements, discussed the participant’s treatment goals, provided early case management and substance use counseling, encouraged attendance at 12-step meetings, promoted abstinence, and emphasized follow through with treatment at the clinic” (Ball et al., 2007, p. 559). All clinicians met monthly with a supervisor to review individual patient treatment progress and submitted audiotaped sessions later rated to assess fidelity to adherence and competence. Further details are available in Ball et al. (2007) and the CTN 0004 protocol (Carroll et al., 2001).

Motivational enhancement therapy

Participants in the MET condition attended three sessions (45–55 min each) during the 4-week active phase as an adjunct to CAU. Clinicians used a MET manual (Farentinos, Obert, & Woody, 2000) developed for the CTN study. The manual describes “three carefully planned sessions, with the first session focused on reviewing an individualized Personal Feedback Report (i.e., summarizes objective and personal information on participant’s substance use), and the other two focused on discussing plans for changing substance use” (Carroll et al., 2001, p. 12). The clinician’s goal was to enhance the client’s own motivation and commitment to change.

Local MET expert trainers from each site were required to attend centralized MET training to standardize the procedures across sites. The local experts then trained the study therapists at their site. After training, each local MET therapist submitted audiotaped practice sessions to the local MET expert trainers. MET therapists were certified when they received at least adequate or average adherence and competence ratings on the structured tape rating system. A paper by Ball et al. (2007) and the CTN 0004 protocol (Carroll et al., 2001) provide more detail on the demographics, training, supervision, and certification of therapists in MET and CAU.

Data Analysis Methods

The outcome measures included the number of self-reported days of primary substance (i.e., cocaine, alcohol, marijuana, two or more drugs, and other drug use as shown in Table 1) use per week for each of the 16 study weeks and treatment retention (the number of days between the day of enrollment and the last day the participant received services at the clinic during the 16 study weeks). Longitudinal analysis using linear mixed modeling was performed to determine treatment difference (MET vs. CAU) in self-reported primary substance use over time (baseline throughout the 16-week study period). The dependent variable was the number of days per week of primary substance use; treatment assignment and time were the independent variables. A random intercept in a model accounted for the correlation of outcome (dependent variable) over time. The relationship between time and the outcome was nonlinear. Separate models were conducted for men and women. A parsimonious final model reflecting nonlinearity is described in the Appendix. Trajectories for MET and CAU were compared and the corresponding p value resulted from specification of appropriate contrasts using parameter estimates from the linear mixed model as described in the Appendix. Kaplan–Meier survival curves were used to display retention (percentage enrolled) over time for the overall sample and, separately, for men and women. The log-rank test was used to compare Kaplan–Meier curves. We considered p values less than or equal to .05 significant. All analyses were performed via SAS or S-plus.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of African American Participants in Clinical Trials Network 0004 Study

| Characteristic | MET (n = 85) | CAU (n = 109) | Total (N = 194) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Female | 21 (24.7) | 27 (24.8) | 48 (24.7) |

| Male | 64 (75.3) | 82 (75.2) | 146 (75.3) |

| Primary substance, n (%) | |||

| Cocaine | 16 (18.8) | 34 (31.2) | 50 (25.8) |

| Alcohol | 28 (32.9) | 23 (21.1) | 51 (26.3) |

| Marijuana | 17 (20.0) | 18 (16.5) | 35 (18.0) |

| 2 or more | 17 (20.0) | 30 (27.5) | 47 (24.2) |

| Other | 7 (8.2) | 4 (3.6) | 11 (5.6) |

| Age (years), Mean (SD) | 36.6 (10.5) | 38.3 (9.5) | 37.5 (9.9) |

Note. MET = motivational enhancement therapy; CAU = counseling as usual.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Table 1 summarizes the demographic characteristics of African American participants in the CTN MET data set. The sample was 24.7% female and the average age was 37.5 years. The two most frequently reported primary substances were alcohol (26.3%) and cocaine (25.8%). Participants reported the highest use of their primary substance use at baseline (M = 2.5 days).

Main Study Findings

Hypothesis 1

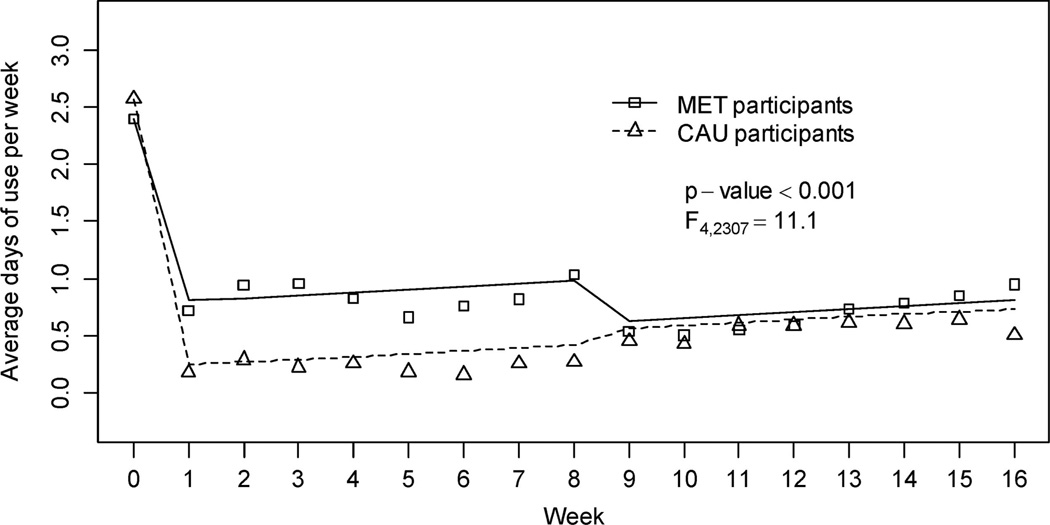

Figure 2 displays the weekly average days of primary substance use per week for the MET and CAU groups. Lines illustrate trajectories based on the fitted model (see the Appendix) and observed data are displayed for MET and CAU representing average (over patients) number of days of primary substance use per week. MET participants reported using primary substances more often than CAU participants, F(4, 2307) = 11.1, p < .001, during the study period ,with the difference occurring primarily in Weeks 1–8 (see Figure 2). This finding was also true for both men (p = .001) and women (p = .001). (Urine toxicology screen data were available only during the 4-week active phase and are therefore not included in the 16-week model. Logistic regression analyses revealed no significant differences (p = .52) on the probability of positive urines between participants in MET and those in CAU during the 4-week active phase. Similar findings emerged when examining gender by treatment differences (p = .68) on the probability of positive urine screens.)

Figure 2.

Average days of primary substance use per week by therapy condition across baseline (Week 0), the active phase (Weeks 1–4), and follow-up phases (Weeks 5–16). MET = motivational enhancement therapy; CAU = counseling as usual. Lines reflect the fitted model. Symbols display observed average weekly primary substance use (in days). Number (N) of participants with available data is listed under the plot separately for each condition.

Hypothesis 2

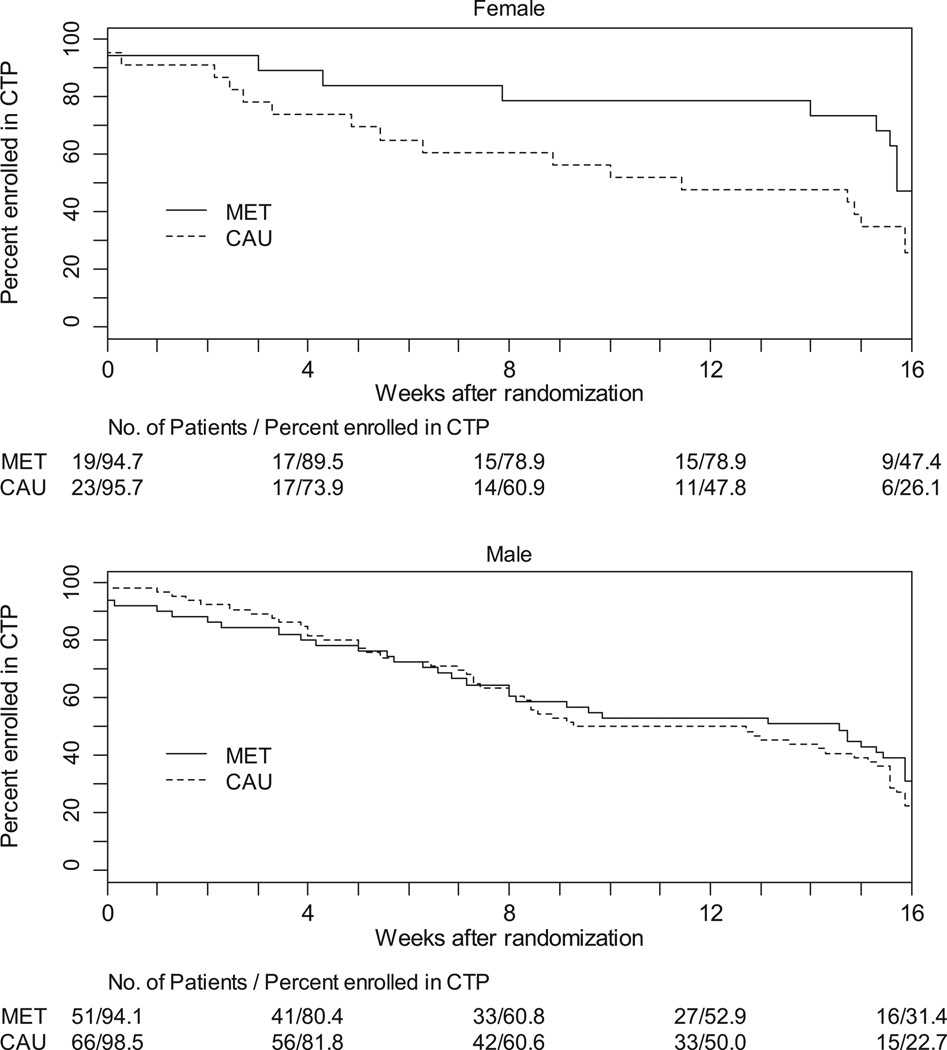

Figure 3 displays the Kaplan–Meier survival curves separately for men and women in MET and in CAU. A log-rank test comparing Kaplan–Meier survival curves for women revealed significantly better retention among women assigned to MET (log-rank statistic = 3.84, p = .05) than women in CAU during the initial 12 weeks (log-rank statistic = 2.90, p = .09, for 16-week data). No retention differences were evident for men (log-rank statistic = 0.03, p = .86, for 12 weeks; log-rank statistic = 0.63, p = .43, for 16 weeks). Moreover, MET and CAU participants overall did not differ significantly on retention (logrank statistic = 2.67, p = .10).

Figure 3.

Therapy condition by gender for the proportion of participants enrolled in the active phase (1–4 weeks) and follow-up phases (5 –16 weeks). MET = motivational enhancement therapy; CAU = counseling as usual; CTP = community-based treatment program.

Discussion

This multisite randomized clinical trial evaluated the efficacy of MET among African Americans in five CTPs. Similar to the original study (Ball et al., 2007), the findings did not support the hypothesis that MET would reduce substance use among African Americans. In fact, MET participants self-reported using primary substances more often than CAU participants. This finding was also true for African American men and women. Several factors might contribute to the lack of effectiveness of MET in reducing substance use. First, MET might best be conceptualized as an adjunct to treatment rather than the primary treatment. Accordingly, a reasonable expectation for a brief three-session intervention might be to prepare the client to respond more favorably to the primary treatment. If that is the case, then increasing retention may be an indication that MET is having the expected effect. The number of sessions of MET may need to be increased before the MET treatment itself can impact substance abuse outcomes. Some existing research supports this viewpoint.The Marijuana Treatment Project Research Group (2004) found that a nine-session multicomponent (i.e., MET, cognitive– behavioral therapy, and case management) intervention yielded better outcomes than a two-session MET intervention. Further research is needed to explore these possibilities.

Second, previous findings also suggest that a culturally tailored version of MET may yield better substance use outcomes for African Americans. Longshore and Grills (2000) evaluated a culturally congruent version of MET for African American substance users. The findings revealed that African Americans in the culturally tailored version of MET used fewer illegal substances 1 year later than participants in standard treatment. Third, the type of drugs used in this sample might have also contributed to the limited effectiveness of the generic version of MET for African Americans in decreasing substance use. Cocaine was one of the most commonly used substances among African Americans in this study. Petry (2003) found that African American cocaine users have more severe employment problems than Whites and may respond better to education-oriented programs targeted to improve vocational skills. The demographics of the current study were consistent with this finding, as 62% of cocaine users were unemployed in the 3 years prior to enrollment in the study. MET lacks an educational component or vocational training. Therefore, future research might examine whether the MET therapeutic approach might be more effective among African American cocaine users as an adjunct to a treatment that includes an educational or vocational component.

The second hypothesis was that African Americans in MET would achieve higher retention rates than African Americans in CAU. The original study did not find any overall or gender differences on retention (Ball et al., 2007). However, the findings in the current study revealed that women in MET had better retention than women in CAU during the first 12 study weeks. The difference between those women still enrolled in MET (89.5%) and CAU (78.9%) by Week 3 was not very large. However, by Week 12, 73.9% of women in MET remained enrolled, but only 47.8% of CAU participants remained. This finding coincides with growing evidence of gender differences in substance abuse outcomes (Amaro, Blake, Schwartz, & Flinchbaugh, 2001; Ellis, Perl, Davis, & Vichinsky, 2008; Greenfield et al., 2007; Marsh, Cao, & D’Aunno, 2004). Although African American women did not display significant reductions in drug use, MET may include activities that are at least effective enough to retain African American women in treatment. Research suggests that African American women prefer therapeutic approaches that enhance selfefficacy and sense of control and include a collaborative relationship (McNair, 1996) with a nonjudgmental and nonconfrontational therapist (Sun, 2006). These values are consistent with the theory of MI. However, the intervention may lack other factors (e.g., culture-specific activities; Longshore & Grills, 2000) that would not only increase retention, but also reduce substance use. Nevertheless, this study provides preliminary evidence for the efficacy of MET in increasing retention among African American women. This finding is particularly important given the low retention rates of African Americans in substance abuse treatment (Milligan et al., 2004).

No significant treatment differences were apparent on retention for men in MET and those in standard treatment. Men are more likely to report experiencing racism and other problems in health encounters than women (Royster, Richmond, Eng, & Margolis, 2006). That reality, or even the perception of racism or discrimination, might lower male retention. In addition, Royster et al. (2006) suggested that men are socialized to exhibit stereotypically masculine behaviors, especially marginalized African American men. Men exhibiting these behaviors and attitudes may be less likely to seek treatment and may experience higher levels of ambivalence and skepticism about treatment even if they do enroll (Longshore, Hsiesh, & Anglin, 1993). Future research should explore the relationship of these attitudes to the retention rates of African American men in MET and other treatments.

Although we have no empirical evidence to explain the difference between the findings at 12 and 16 weeks, two speculations are at least plausible. First, the effects of MET on treatment participation (i.e., retention) could diminish after 12 weeks. Exploring efforts to increase the sustainability of MET from 12 versus 16 weeks may be a useful focus for future research. This recommendation for further research is also consistent with a meta-analysis of MI studies conducted by Hettema et al. (2005). The authors found that the treatment effect diminished over time in several controlled trials of MI. Second, some participants may have been inactive at the 16-week point because participants completed treatment at different rates. Therefore, the retention findings during Week 16 may be confounded because some participants may have completed treatment faster than others. The difference in treatment completion might also vary by site.

This study has several strengths. First, the study addressed three major gaps in the literature: (a) examining retention and substance use outcomes specifically among African American MET participants, (b) assessing outcomes in a generic (i.e., not culturally tailored) version of MET, and (c) identifying gender as a potential moderator that may explain the inconsistent findings in past research on the efficacy of MI/MET for African Americans. Second, the CTN data used to conduct this secondary analysis had several strengths, including random assignment of participants and therapists to treatment conditions, the use of therapists certified in MET, and the inclusion of therapists without prior allegiance to MET (Ball et al., 2007).

Nonetheless, the research team for the original study mentioned some of the same limitations in this study that are common to clinical trials, such as inconsistencies in treatment delivery, inconsistencies in training, and the possible contamination of therapy conditions (Ball et al., 2007). Because these limitations apply to both treatment conditions, there is no evidence that these limitations had any influence on the current findings. However, we encourage researchers to address these limitations in future research. Despite the limitations pointed out in the original study, this trial provides valuable clinical and research implications for substance abuse treatment for African Americans.

Two measurement issues warrant further discussion. First, the current study included an analysis only of participants’ primary substance use. We opted to use primary substance abuse as our outcome variable for two reasons. First, in an effort to replicate the Ball et al. (2007) study with the African American sample, we decided to define substance use in the same way as the original authors. Second, primary substance use was one of the variables used in the urn randomization. For that reason, we have more confidence that the MET and CAU groups were balanced on primary substance use than on the other substance use variables. Nevertheless, we acknowledge the possibility that a treatment could reduce primary substance use, but increase or not reduce other substance use. Because such a finding would have important implications for the development of future treatments, we recommend that future studies also consider the participant’s secondary substances of abuse not only as an outcome but also during the randomization process.

The use of self-report, particularly when measuring sensitive behaviors, is another limitation. The original study collected urine screens only for the 4-week active phase. Urine screen data were analyzed for the 4-week active phase in the current study, but unfortunately did not allow for a 16-week analysis. Although the study lacks a 16-week urine screen analysis, previous research supports the accuracy of self-report information about substance use (Fals-Stewart et al., 2000; Levy et al., 2004).

The findings from the current study demonstrate that study designs that consider the heterogeneity within a racial/ethnic group may yield even more information regarding the treatment effectiveness. Findings from the original study (Ball et al., 2007) did not reveal retention differences between individuals in MET and CAU. However, our separate analysis of the data for African Americans revealed group differences in retention, but for women only. If the data had not been analyzed separately for men and women, this promising finding may not have emerged. Findings are also consistent with the notion that examining interaction effects may yield additional information beyond the main effects alone (Hser, Polinsky, Maglione, & Anglin, 1999).

The results from this study reveal that MET may improve retention among African American women. Furthermore, the findings underscore the need to identify other treatment components required not only to increase retention, but also to reduce substance use. Overall, this study highlights the importance of considering the heterogeneity within ethnic groups (e.g., gender) when studying treatment outcomes. Therefore, future MI/MET studies on African American substance users should continue to examine the influence of moderators, such as age (Lemke & Moos, 2003) and drug type (Stephens, Roffman, Fearer, Williams, & Burke, 2007) on the relationship between treatment and outcomes. Furthermore, there is a dearth of literature examining how MI/MET exerts its effects (Apodaca & Longabaugh, 2009), especially among African American substance users. Therefore, studies are needed that examine potential variables that contribute to behavior change in MI/MET. For example, several studies support change talk (talk in favor of making a behavior change) as a potential mediator between MI/MET and successful treatment outcomes (Amhrein, Miller, Yahne, Palmer, & Fulcher, 2003). No studies are available on the influence of change talk or other potential mechanisms of change among African American substance users in MI/MET.

Future research that replicates (e.g., Longshore & Grills, 2000) and develops more culturally tailored MET interventions are needed. Research suggests that culturally tailored versions of substance abuse treatments are effective for African Americans. For example, Matthews, Sanchez-Johnson, and King (2009) found that a culturally targeted intervention (i.e., using community-based recruitment strategies and addressing specific cultural factors that affect tobacco use among African Americans and their participation in smoking cessation research) that incorporated theoretical guidelines from cognitive– behavioral therapy (CBT), MI, and the 12-step program was more effective than standard treatment (i.e., excludes the culturally targeted components) among African American smokers. African American smokers in the culturally targeted intervention had higher quit rates and better retention and follow-up than those in standard treatment. In addition, this study highlights the significance of examining the efficacy of MI/MET as an adjunct to other evidence-based treatments, such as CBT, for African Americans. Future research should examine how MI/MET works, for what subgroups of African Americans substance users and under what set of conditions.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kathleen Carroll and Samuel Ball and their research team at Yale University for sharing their data from the Clinical Trials Network and providing invaluable input on the development of the article.

Appendix

Table A1 summarizes the fitted longitudinal model with self-reported number of days of primary substance use per week at each of the 16 study weeks as the outcome. The model contains treatment and time in the most parsimonious nonlinear form appropriate to the data. Coding of all the considered independent variables is described in the note to Table A1. The p value for difference between MET and CAU resulted from a test of hypothesis that coefficients for TRT, TRT*TIMEMIN, TRT*TIMEMAX, and TRT*POST8 are simultaneously equal to zero.

Table A1.

Fitted Longitudinal Model of Primary Substance Use Across 16 Study Weeks

| Effect | Coefficient | SE | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 2.552 | 0.159 | <.001 |

| TRT | −0.174 | 0.244 | .475 |

| TIMEMIN | −2.336 | 0.119 | <.001 |

| TIMEMAX | 0.0246 | 0.00948 | .0096 |

| POST8 | 0.127 | 0.0960 | .188 |

| TRT*TIMEMIN | 0.738 | 0.174 | <.001 |

| TRT*POST | −0.495 | 0.089 | <.001 |

Note. TRT (1:MET, 0:CAU); TIMEMIN = min(1, time), time measured in weeks; TIMEMAX = max(1, time); POST8 indicator for long-term follow-up (1: time > 8 weeks, 0: time ≤ 8 weeks).

Footnotes

MI and MET are used interchangeably throughout the article.

Contributor Information

LaTrice Montgomery, Department of Psychology, University of Cincinnati.

Ann Kathleen Burlew, Department of Psychology, University of Cincinnati.

Andrzej S. Kosinski, Department of Biostatistics and Bioinformatics, Duke University School of Medicine/Duke Clinical Research Institute

Alyssa A. Forcehimes, Department of Psychology, University of New Mexico/Center on Alcoholism, Substance Abuse, and Addictions

References

- Agosti V, Nunes EV, Ocepeck-Welikson K. Patient factors related to early attrition from an outpatient cocaine research clinic. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 1996;22:29–39. doi: 10.3109/00952999609001643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaro H, Blake SM, Schwartz PM, Flinchbaugh LJ. Developing theory-based substance abuse prevention programs for young adolescent girls. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2001;21:256–293. [Google Scholar]

- Amhrein PC, Miller WR, Yahne, Palmer CE, Fulcher L. Client commitment language during motivational interviewing predicts drug use outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:862–878. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.5.862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apodaca TR, Longabaugh R. Mechanisms of change in motivational interviewing: A review and preliminary evaluation of the evidence. Addiction. 2009;104:705–715. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02527.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball SA, Martino S, Nich C, Frankforter TL, Van Horn D, Crits-Cristoph, Carroll KM. Site matters: Multisite randomized trial of motivational enhancement therapy in community drug abuse clinics. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:556–567. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.4.556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke BL, Arkowitz H, Menchola M. The efficacy of motivational interviewing: A meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:843–861. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.5.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burlew AK, Feaster D, Brecht M, Hubbard R. Measurement and data analysis in research addressing health disparities in substance abuse. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2009;36:25–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burlew AK, Weekes JC, Montgomery L, Feaster DJ, Robbins MS, Rosa CL, Wu L. Conducting research with ethnic minorities: Methodological lessons from the NIDA Clinical Trials Network. American Journal of Drug Abuse and Alcohol. 2011;37:324–332. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2011.596973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll K, Ball S, Crits-Cristoph P, Farentinos C, McLellan T, Morgenstern J, Woody G. Clinical Trial Network (CTN) 0004 protocol: Motivational enhancement treatment to improve treatment engagement and outcome in individuals seeking treatment for substance abuse. Bethesda, MD: National Institute of Drug Abuse; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Castro FG, Barrera M, Holleran-Steiker LK. Issues and challenges in the design of culturally adapted evidence-based interventions. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2010;6:213–239. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-033109-132032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrman RN, Robbins J. Reliability and validity of 6-month timeline reports of cocaine and heroin use in a methadone population. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1994;62:843–850. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.4.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis JA, Perl SB, Davis K, Vichinsky L. Gender differences in smoking and cessation behaviors among young adults after implementation of local comprehensive tobacco control. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98:310–316. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.101758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W, O’Farrell TJ, Freitas TT, McFarlin SK, Rutigliano P. The Timeline Followback reports of psychoactive substance use by drug-abusing patients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:134–144. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.1.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farentinos C, Obert JL, Woody GE, editors. CTN Motivational Enhancement Treatment Manual. Draft. 2000;1 Unpublished Manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Galea S, Rudenstein S. Challenges in understanding disparities in drug use and its consequences. Journal of Urban Health. 2005;82:5–12. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield SF, Brooks AJ, Gordon SM, Green CA, Kropp F, McHugh RK, Miele GM. Substance abuse treatment entry, retention, and outcome in women: A review of the literature. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;86:1–21. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heron RL, Twomey HB, Jacobs DP, Kaslow NJ. Culturally competent interventions for abused and suicidal African American women. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training. 1997;34:410–424. [Google Scholar]

- Hettema JE, Hendricks PS. Motivational interviewing for smoking cessation: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78:868–884. doi: 10.1037/a0021498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hettema J, Steele J, Miller W. Motivational interviewing. Annual Review in Clinical Psychology. 2005;1:91–111. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hser YI, Polinsky ML, Maglione M, Anglin MD. Matching clients’ needs with drug treatment services. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1999;16:299–305. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(98)00037-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson MS, Stephens RC, Smith RL. Afrocentric treatment in residential substance abuse care. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1997;14:87–92. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(96)00120-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy GJ, Efremova I, Frazier A, Saba A. The emerging problems of alcohol and substance abuse in late life. Journal of Social Distress and the Homeless. 1999;8:227–239. [Google Scholar]

- Lemke S, Moos H. Outcomes at 1 and 5 years for older patients with alcohol use disorders. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2003;24:43–50. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00321-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy S, Sherritt L, Harris SK, Gates EC, Holder DW, Kulig JW, Knight JR. Test-retest reliability of adolescents’ self-report of substance use. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2004;28:1236–1241. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000134216.22162.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longshore D. Help-seeking by African American drug users. Addictive Behaviors. 1999;24:683–686. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00111-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longshore D, Grills C. Motivating illegal drug use recovery: Evidence for a culturally congruent intervention. Journal of Black Psychology. 2000;26:288–301. [Google Scholar]

- Longshore D, Grills C, Annon K. Effects of a culturally congruent intervention on cognitive factors related to drug-use recovery. Substance Use & Misuse. 1999;34:1223–1241. doi: 10.3109/10826089909039406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longshore D, Hsieh S, Anglin MD. Methadone maintenance and needle/syringe sharing. International Journal of the Addictions. 1993;28:983–996. doi: 10.3109/10826089309062178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundahl BW, Kunz C, Brownell C, Tollefson D, Burke BL. A meta-analysis of motivational interviewing: Twenty-five years of empirical studies. Research on Social Work Practice. 2010;20:137–160. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh JC, Cao D, D’Aunno T. Gender differences in the impact of comprehensive services in substance abuse treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2004;27:289–300. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marijuana Treatment Project Research Group. Brief treatments for cannabis dependence: Findings from a randomized multisite trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:455–466. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews AK, Sanchez-Johnson L, King A. Development of a culturally targeted smoking cessation intervention for African American smokers. Journal of Community Health. 2009;34:480–492. doi: 10.1007/s10900-009-9181-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCaul ME, Svikis DS, Moore RD. Predictors of outpatient treatment retention: Patient versus substance use characteristics. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2001;62:9–17. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00155-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNair LD. African American women and behavior therapy: Integrating theory, culture, and clinical practice. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 1996;3:337–349. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, DelBoca FK. Measurement of drinking behavior using the Form 90 Family of Instruments. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1994;12(Suppl):112–117. doi: 10.15288/jsas.1994.s12.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Milligan CO, Nich C, Carroll K. Ethnic differences in substance abuse treatment retention, compliance, and outcome from two clinical trials. Psychiatric Services. 2004;55:167–173. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.2.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery L, Burlew AK, Wilson J, Hall R. Promising evidence-based treatments for African Americans: Motivational interviewing/motivational enhancement therapy. In: Columbus AM, editor. Advances in psychology research. New York: Nova Science Publishers; (in press). Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Mullins SM, Suarez M, Ondersma SJ, Page MC. The impact of motivational interviewing on substance abuse treatment retention: A randomized control trial of women involved with child welfare. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2004;27:51–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naar-King S, Outlaw A, Green-Jones M, Wright K, Parsons JT. Motivational interviewing by peer outreach workers: A pilot randomized clinical trial to retain adolescents and young adults in HIV care. AIDS Care. 2009;21:868–873. doi: 10.1080/09540120802612824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogedegbe G, Schoenthaler A, Richardson T, Lewis L, Belue R, Espinosa E, Charlson ME. An RCT of the effect of motivational interviewing on medication adherence in hypertensive African Americans: Rationale and design. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2007;28:169–181. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM. A comparison of African American and non-Hispanic Caucasian cocaine-abusing outpatients. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2003;69:43–49. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00255-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC, Norcross JC. In search of how people change: Applications to addictive behavior. American Psychologist. 1992;47:1102–1114. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.47.9.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnicow K, Jackson A, Wang T, De AK, McCarty F, Dudley W, Baranowski T. A motivational interviewing intervention to increase fruit and vegetable intake though Black churches: Results of the Eat for Life trial. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91:1686–1693. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.10.1686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royster MO, Richmond A, Eng E, Margolis L. Hey brother, how’s your health? A focus group analysis of the health and health-related concerns of African American men in a southern city in the United States. Men and Masculinities. 2006;8:389–404. [Google Scholar]

- Shillington AM, Clapp JD. Adolescents in public substance abuse treatment programs: The impact of sex and race on referrals and outcomes. Journal of Child and Adolescent Substance Abuse. 2003;12:69–79. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson DD. Treatment for drug abuse: Follow-up outcomes and length of time spent. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1981;38:875–880. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1981.01780330033003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson DD, Joe GW, Rowan-Szal GA. Drug abuse treatment retention and process effects on follow-up outcomes. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1997;47:227–235. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)00099-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline Follow Back. A technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption. In: Litten R, Allen J, editors. Measuring alcohol consumption. New York, NY: Humana Press; 1992. pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- Stephens RS, Roffman RA, Fearer SA, Williams C, Burke RS. The Marijuana Check-up: Promoting change in ambivalent marijuana users. Addiction. 2007;102:947–957. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01821.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stout RL, Wirtz PW, Carbonari JP, DelBoca FK. Ensuring balanced distribution of prognostic factors in treatment outcome research. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1994;12(Suppl):70–75. doi: 10.15288/jsas.1994.s12.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strycker LA, Duncan SC, Pickering A. The social context of alcohol initiation. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse. 2003;2:35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2007 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National findings (Office of Applied Studies, NSDUH Series H-34, DHHS Publication No. SMA 08-4343) Rockville, MD: Department of Health and Human Services; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2008 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National findings (Office of Applied Studies, NSDUH Series H-36, DHHS Publication No. SMA 09-4434) Rockville, MD: Department of Health and Human Services; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sue S. Psychotherapeutic services for ethnic minorities. American Psychologist. 1988;43:301–308. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.43.4.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun A. Program factors related to women’s substance abuse treatment retention and other outcomes: A review and critique. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2006;30:1–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasilaki EI, Hosier SG, Cox WM. The efficacy of motivational interviewing as a brief intervention for excessive drinking: A meta-analytic review. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2006;41:328–335. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agl016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winhusen T, Kropp F, Babcock D, Hague D, Erickson SJ, Renz C, Somoza E. Motivational enhancement therapy to improve treatment utilization and outcome in pregnant substance users. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2008;35:161–173. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]