Abstract

An effective immune response to an invading viral pathogen requires the combined actions of both innate and adaptive immune cells. For example, NK cells and cytotoxic CD8 T cells are capable of the direct engagement of infected cells and the mediation of antiviral responses. Both NK and CD8 T cells depend on common gamma chain (γc) cytokine signals for their development and homeostasis. The γc cytokine IL-15 is very well characterized for its role in promoting the development and homeostasis of NK cells and CD8 T cells, but emerging literature suggests that IL-15 mediates the anti-viral responses of these cell populations during an active immune response. Both NK cells and CD8 T cells must become activated, migrate to sites of infection, survive at those sites, and expand in order to maximally exert effector functions, and IL-15 can modulate each of these processes. This review focuses on the functions of IL-15 in the regulation of multiple aspects of NK and CD8 T cell biology, investigates the mechanisms by which IL-15 may exert such diverse functions, and discusses how these different facets of IL-15 biology may be therapeutically exploited to combat viral diseases.

Keywords: IL-15, Anti-viral Immunity, NK Cells, CD8 T Cells, Immune Intervention, Cytokine Therapy

1. Introduction

Cytokines are low molecular weight proteins that mediate intra and intercellular communications in the body. Though most cell types in the body express cytokines or their receptors, a large role for cytokine signaling has been defined in the immune system, and cytokines are best characterized as immunomodulators. As such, cytokine production, regulation, and administration shape the development of the immune response to pathogens, autoimmune disorders, inflammatory diseases, and immunodeficiencies. Within and outside the immune system, cytokines are expressed by a variety of cell types and exert a wide range of functions, often exhibiting a high degree of pleiotropy and redundancy in their effects. This redundancy can, in part, be explained by the sharing of receptor subunits. An often-referred to example is the common gamma chain family of cytokines, which includes IL-2, IL-4, IL-7, IL-15, IL-9, and IL-21 and all have multimeric receptors that utilize the common gamma chain (γc).

IL-15 is a γc cytokine independently identified by two groups in 1994 based on its ability to stimulate the proliferation of the murine T cell line CTLL-2 [1-3]. Now, human, murine, bovine, porcine, feline, and rabbit IL-15 have all been cloned with 70-80% structural homology [4]. Like IL-2, IL-15 is a 14-15 kDa glycoprotein member of the four α-helix bundle-containing cytokines [2, 5, 6]. Additionally, both cytokines signal through trimeric receptors that utilize γc, and CD122 (IL-2 Rβ) [2, 7]. Specificity for a cytokine is conferred to each receptor by a private α chain, CD25 or IL-15Rα for IL-2 and IL-15, respectively [8, 9]. IL-15 may be presented in trans to responsive cells expressing CD122 and CD132 by cells expressing the cytokine itself bound to a membrane form of the receptor alpha chain [10], and a similar mode of signaling may also exist for IL-2 [11]. With so many shared structural and signaling components, it is not surprising that IL-2 and IL-15 also share many functional redundancies including induced proliferation of NK and CD8 T cells and enhanced CTL activity in these cell types [12-14]. Both cytokines also induce the proliferation and differentiation of stimulated human B cells [15]. Despite the many overlapping functions between IL-2 and IL-15, however, it has become abundantly clear that IL-15 exclusively mediates many immune functions. Whereas IL-2 has a critical role in activation-induced cell death (AICD), IL-15 appears to always oppose AICD by acting to prolong the survival of T lymphocytes [16, 17]. IL-15 is also exceptional in its ability to support the homeostasis of natural killer (NK cells) and memory phenotype and antigen-specific memory CD8 T cells, and it is probably best characterized for its role in maintaining memory pools of CD8 T cells [18]. Therefore, despite the high degree of redundancy in cytokine signaling within the immune system, IL-15 clearly mediates many important unique aspects of immunity.

Emerging literature is revealing many divergent functions for IL-15 outside of the immune system as well, but many of these functions—and mechanisms by which these functions are differentiated in various cell types—are not well understood. IL-15 transcripts are abundantly expressed in placenta and skeletal muscle, and IL-15 has been implicated in a variety of physiological processes including angiogenesis [19], skeletal muscle hypertrophy [20], endometrial decidualization [21], permeability of the blood brain barrier [22], and body fat composition [23]. IL-15 expression in all tissues is heavily regulated at the posttranscriptional level [24, 25] (Tagaya [26] and Budagian [4]) review these modifications at length). Overall, IL-15 translation is very inefficient due to multiple layers of negative regulation. Such abundant regulatory mechanisms may reflect on IL-15’s potency as a pro-inflammatory cytokine. Unchecked IL-15 expression could easily lead to a various inflammatory and autoimmune disorders, and indeed, IL-15 is implicated in the pathology of many of these diseases including inflammatory bowel disorder, celiac disease, and rheumatoid arthritis [27]. However, IL-15 expression induced by an infectious agent is a very important part of transforming NK cells, CD8 T cells, and other cells of the immune system into functional effectors capable of efficiently eliminating pathogens. Both innate and adaptive immune responses can be ramped up or dampened down by increasing or decreasing IL-15 availability, respectively. While it is clear that IL-15 mediates an incredible number of various functions within and outside of the immune system, this review seeks to emphasize the many roles IL-15 plays in modulating immune responses to viral pathogens.

An effective immune response to an invading viral pathogen invasion consists of the combined effects of both innate and adaptive immune cells, which are responsible for the recognition and removal of infected host cells in order to halt viral replication. The cell types best capable of engaging infected cells directly and mediate antiviral responses through cytokine release (such as IFN γ) are NK cells, lymphocytes of the innate immune system, and cytotoxic CD8 T cells, lymphocytes of the adaptive immune system. As recently reviewed by Sun and Lanier [28], these cell populations bear many parallels to one another, including their professional killing capacities via release of perforin and granzymes, their development from common lymphoid progenitors, and notably, their dependence on γc cytokine signals for their development and homeostasis. Both NK cells and CD8 T cells must become activated in the presence of foreign antigens, migrate to sites of infection, and be able to survive and expand in order to maximally exert effector functions. Although a variety of cytokine signals are important in this process, IL-15 is a potent activator, chemotactic agent, and homeostatic signal for NK cells and CD8 T cells. This review focuses on the functions of IL-15 in the regulating multiple aspects of NK and CD8 T cell biology, as well as the mechanisms by which IL-15 may exert such diverse functions, and discusses how these different facets of IL-15 biology may be therapeutically exploited to combat virus-mediated diseases.

2. IL-15 and Immune Cell Function

2.1 IL-15 and Natural Killer Cells

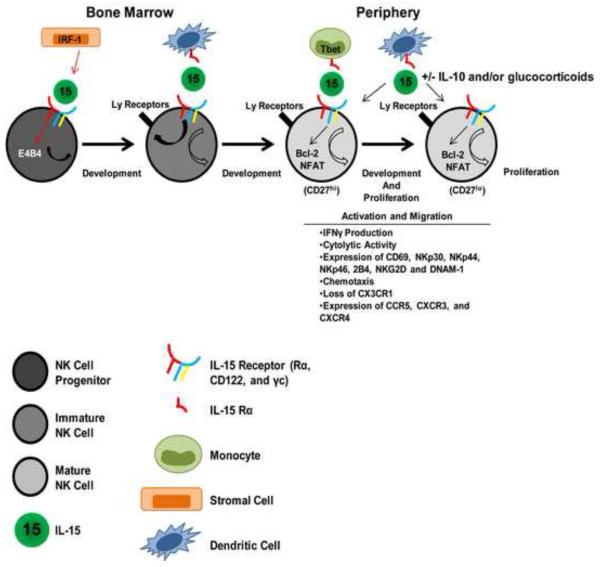

In addition to B and T cells, NK cells constitute the third population of cell types that originate from a common lymphoid progenitor. Despite their lymphocyte origin, NK cells have been classified as innate immune cells because they do not use recombination-activating gene (RAG) enzymes to generate specific antigen receptors, and, as such, are able to respond rapidly to infected cells without any prior sensitization [28]. Although IL-15 is an important modulator of many different functions of innate immune cells such as neutrophils, basophils, and eosinophils, NK cells are perhaps the innate immune effector most dependent on IL-15 signaling for development, homeostasis, and function (Fig 1).

Figrure 1

All stages of developing NK cells express high levels of CD122, suggesting that IL-15 could act on these cells throughout the entire course of their development [29]. Accordingly, analyses of IL-15−/− and IL-15Rα−/− animals revealed severe reductions in numbers of NK cells, implicating an important role for IL-15 in the development of NK cells [29-32]. The earliest NK cell progenitor does not have any known lineage-specific markers, but is currently identified as a non-stromal bone marrow cell that expresses CD122 and IL-15Rα [33]. The necessary expression of CD122 and IL-15Rα by NK cell progenitors highlights how important IL-15 signaling is in the early development of NK Cells, and in vitro studies have confirmed that IL-15 is sufficient in inducing differen tiation of NK cells from early hematopoietic cells [34]. How IL-15 signaling in early haematopoietic cells results in NK cell differentiation is somewhat less clear, but many studies have contributed significantly to understanding the induction of NK cell development by IL-15. IL-15 expression in bone marrow stromal cells is upregulated by IRF-1 acting on an IRF response element in the IL-15 promoter (IRF-E) [35]. The induced IL-15 then acts on NK and NK T cell progenitors, stimulating their subsequent maturation [35, 36]. Therefore, upstream expression of the IRF-1 transcription factor is important for IL-15 expression and subsequent NK cell development. Additionally, transcription factors downstream of IL-15 signaling within the NK cell progenitor have also been identified. The transcription factor E4BP4 (also known as NFIL3) has been proposed as a NK cell lineage-specifying factor, since E4BP4-deficient mice show a severe reduction in NK cell numbers [37, 38]. E4BP4 was shown to be downstream of IL-15R signaling when addition of exogenous IL-15 was unable to rescue NK cell development in E4BP4-deficient progenitor cells [37]. Thus, transcription factors not only influence the expression of IL-15 (and probably its receptor), but also lie downstream of the IL-15R signaling pathway in NK cell progenitors to control subsequent stages of NK cell development.

Another way in which IL-15 signaling may affect NK cell development is through the induction of Ly49 receptors. Ly49 receptors mediate activating and inhibitory signaling in mature NK cells through interactions with MHC class I elements and are increasingly more appreciated as important mediators of “education” or “licensing” in developing NK cells [39, 40]. Some reports indicate that in NK cells lacking IL-15Rα Ly49 expression is reduced [41]. Others have indicated that immature NK cells in IL-15−/− mice do express Ly49 receptors, but these cells do not phenotypically develop beyond the “minor but discrete CD11b− CD27+DX5hiCD51dullCD127dullCD122hi stage” [42]. Still others have used a model in which bone marrow (BM)-derived dendritic cells were prepared from mice transgenically modified to express varying amounts of IL-15α to demonstrate that NK cell homeostasis, NK cell differentiation, and acquisition of Ly49 receptor and effector functions by NK cells require different levels of IL-15 trans-presentation input to achieve full status [43]. IL-15 promotes not only early NK cell development but is also suggested to be important for the differentiation of CD11b+CD27+ NK cells into CD11b+CD27− fully matured NK cells, as monocytes need to express Tbet and IL-15Rα for this maturation to occur [44]. Although many differences exist between mouse and human NK cell development, recombinant human interleukin-15 (rhIL-15) or an Adenovirus-vector expressing human IL-15 is able to significantly enhance NK cell development and maturation in the bone marrow and liver of Balb/c Rag2−/−γc−/− mice reconstituted with human hematopoietic stem cells [45]. Thus, varying levels of IL-15 stimulation in discrete microenvironments may induce different stages of NK cell development, and only further study will determine when, where, and how much IL-15 is available in vivo to the various stages in the NK cell lineage.

In addition to the requirement for IL-15 in optimal NK cell development and maturation, NK cells require IL-15 for their homeostasis in the periphery—that is to maintain normal numbers. Mature NK cells adoptively transferred into IL-15−/− or IL-15Rα−/− mice fail to proliferate, and their half-life of 7-8 days is reduced to only 2 days [46, 47]. The mechanisms by which IL-15 influences the homeostasis of NK cells are known to depend on IL-15’s ability to induce Bcl-2 expression [46] and suppress both the forkhead box O3A (FOXO3A) and the pro-apoptotic factor Bcl-2-interacting mediator of cell death (BIM) transcription factors [48]. Interestingly, these vital signals are dependent on the transpresentation of IL-15 by IL-15Rα-expressing dendritic cells [18]. Whereas mixed bone chimeras generated from IL-15Rα−/− mice and IL-15Rβ−/− mice could support the survival of adoptively transferred NK cells, mixed bone chimeras generated from IL-15Rα−/− and IL-15−/− mice could not, indicating that IL-15 and its Rα chain must be expressed by the same cells types to support the survival of NK cells [47, 49]. In complimentary experiments, forced expression of IL-15R on only dendritic cells (DCs) or treatment of mice with soluble IL-15 /IL-15Rα complexes promotes the expansion of NK cell populations [50, 51]. In human NK cells, IL-15 sustains the expression of its high-affinity receptor, leading to long-lasting STAT5 phosphorylation and Bcl-2 expression important for the long-term survival of these cells [52].

Although survival of mature NK cells is in the periphery is strictly dependent on transpresented IL-15, this requirement can be by-passed by transgenically forcing the constitutive expression of Bcl-2 [53]. However, even though numbers of circulating NK cells could be restored in these transgenic animals, the NK cells in these mice were impaired in their cytolytic activity [53]. More recent research suggests that IL-15 works additively with IL-10 to increase cytotoxicity of NK cells [54]. Glucocorticoids may also work synergistically with IL-15 to mediate activation of NK cells. Glucocorticoids when combined with IL-15 in cultures of peripheral blood (PB)-derived CD56+ cells induce increased cytolytic activity, IFNγ production, and expression of NKp30, NKp44, NKp46, 2B4, NKG2D and DNAM-1 [55].These data imply that IL-15 is also an important signal in the activation of NK cells. Dendritic cells (DCs) are known to activate NK cells [56], and IL-15Rα expression by the DC is an essential component in its ability to activate NK cells, enhancing both cytolytic activity and IFNγ production [57]. Upon transient or prolonged exposure to IL-15 complexed to a soluble form of its receptor alpha chain in vivo, NK cells also undergo distinct phenotypic changes [58]. Importantly, transient stimulation augmented the NK cell pool and le d to a more activated phenotype including increased CD69, NKG2D, and NKp46 expression; whereas chronic stimulation with IL-15 complexes appeared to impair NK cell activation and function [58]. Therefore, although future study is clearly warranted in this area, IL-15 may provide important signals for tuning the activation state of mature NK cells.

Mature NK cells are largely localized in the red pulp of the spleen and the sinusoidal regions of the liver; however, during viral infection they infiltrate the splenic white pulp and migrate rapidly to sites of infection [59]. The precise signals required for NK cell traffic in different situations are not well defined, but a small but convincing body of literature implicates IL-15 in the migration of NK cells from the circulation to sites of immunological insult. Only three years after the discovery of the cytokine, it was shown that NK cells would migrate to IL-15 in in vitro checkerboard chemotaxis assays and that these cells adherred more readily to a vascular endothelial cell line after stimulation with IL-15 [60]. Our own findings indicate that IL-15 is an important factor in recruiting NK cells from the circulation to the lung airways upon influenza infection, and NK cells from influenza-infected animals migrate to IL-15 in an in vitro transwell assay (Verbist, 2012, Publication Pending). Although IL-15 does appear to induce the migration of NK cells, it is unclear whether this is direct chemotaxis to the cytokine or an indirect effect due to modulation of other cell surface receptors. Stimulation with IL-15 is known to modulate CD11a expression on NK cells, thus increasing their adhesion to vascular endothelium [60]. Additionally, stimulation with IL-15 is known to alter the expression of several different chemokine receptors on the surface of NK cells. Expression of CX3CR1 is well described as a chemokine receptor whose expression is negatively regulated by IL-15 signaling through NFAT-dependent mechanisms [61, 62]. This effect appears to be specific to CX3CR1, however, as expression of CCR5 by NK cells is increased upon stimulation with IL-15, and expression of CXCR4 remains unaltered upon IL-15 stimulation [63]. In combination with glucocorticoids, treatment of PBMC-derived NK cells with IL-15 significantly increased surface expression of CXCR3 and CXCR4 [55].

Overall, IL-15 is a key regulator of NK cells, modulating all aspects of NK cell biology, including their development and maturation, survival and proliferation, activation and cytoxicity, and migration to sites of inflammation. Thus, IL-15 is a vital part of NK cell responses, effecting a population of innate cells in sufficient number and capacity to respond to infection and limit viral replication.

2.2 IL-15 and Antigen-Presenting Cells

Although the immune system is frequently and conveniently broken down into innate and adaptive immunity, in reality there is no clear demarcation in vivo indicating the end of innate responses and the initiation of adaptive responses. Rather, a cascade of innate effectors is followed fluidly by a cascade of adaptive effectors whose functions are shaped by the signals of their predecessors. Although almost all cells of the innate immune system can affect those of the adaptive immune system, the key regulators of adaptive responses and long-considered “bridges” of innate and adaptive immunity are antigen presenting cells (APCs). APCs including dendritic cells and monocytes/macrophages are not only profoundly affected by IL-15 signals, but are also key producers of IL-15. Thus, IL-15 represents a cytokine signal that influences and informs both arms of the immune system and brings them together into a single, functional unit.

In response to infection, antigen-presenting cells must functionally mature to optimally prime cells of the adaptive immune system, and IL-15 plays an important role in this process. IL-15 stimulation enhances the phagocytic uptake of microbial pathogens by monocytes and macrophages and induces the production of pro-inflammatory factors such as IL-8 and monocyte chemotactic protein 1 (MCP-1) by these cells [64]. IL-15 signaling in DCs may also lower the peptide concentration required for priming, as this has been shown to be the case in IL-15-stimulated DCs used to prime CTL responses to melanoma antigens [65], possibly because IL-15 stimulation increases levels of CD11c and MHC molecules, as well as CD40, CD80, and CD86 [66]. Similarly, IL-15 enhances IL-12 production and responsiveness, increases IFNγ production, and enables cross talk between conventional DCs and plasmacytoid DCs by upregulating CD40 on conventional DCs that allows interactions with CD40L-expressing plasmacytoid DCs [4, 67]. Furthermore, DCs from IL-15 deficient mice are impaired in their ability to prime delayed type hypersensitivity reactions or produce IL-2 and thus stimulate T cell proliferation [68, 69]. In contrast, in in vivo infection models, initial priming and proliferation of T cells in IL-15−/− mice appears to be unaltered, with defects in T cell proliferation appearing only late in the memory phase [70, 71]. These differences may be accounted for by compensatory and/or redundant cytokine signals in active infections, that is, the context in which these cells are primed. Monocytes differentiated in vitro into DCs with GM-CSF and IL-15 initiate Th1 and Th17-type responses [72], and enhance NK cell production of IFNγ, leading to enhanced CD8 T cell induction [73]. There is little doubt, then, that IL-15 signaling in responsive APCs is an important part of shaping subsequent responses in specific lymphocyte populations.

Not only must antigen-presenting cells be able to receive signals from IL-15 to be fully functional, but in order to instruct the eventual functions of the cells they prime, antigen-presenting cells provide soluble IL-15 or transpresent it to the cells that they interact with. DCs matured with pathogenic stimuli such as poly I:C and LPS produce IL-15 in response [74]. The stimulation of DCs with covalently linked extracellular CD40L domains also induces the production of IL-15 and enhances T cell proliferation to C. albicans antigen [75]. In anti-viral immune responses, type 1 interferons serve as a potent inducer of IL-15 expression, since the IL-15 promoter contains an interferon regulated element [74, 76]. Once APCs are induced to express IL-15, NK and T cells are able to respond to these signals, continuing the evolution of the immune response to the invading pathogen. It has been shown, for example, that monocytes activate NK and NKT cell proliferation and LMP1 expression through transpresented IL-15 [77]. Additionally, DC-derived IL-15 is required for tumoricidal NK activity [78] as well as CD69 expression, IFNγ secretion, and proliferation [79]. IL-15 presented by dendritic cells to anti-viral CD8 T cells is also important for the generation and maintenance of these responses in both systemic viral infections [80] and at specific sites following tissue-specific infections [81], partially because IL-15 expression by DCs in response to signals from Ag-specific CD4 cells is an important mechanism by which CD8 T cells escape TRAIL-mediated apoptosis during immune reactions [82].

2.3 IL-15 and CD8 T Cells

CD8 T cells express all three components of the IL-15 heterotrimeric receptor. Although T cells constitutively express very low levels of IL-15Rα [6], expression of this receptor chain is induced by stimulation with IL-2, anti-CD3 antibody, or phorbol-myristate acetate. CD122 is constitutively expressed by T cells; although, CD8 T cells express much higher levels of this receptor chain than CD4 cells, and memory subsets express higher levels than naïve subsets [83]. In general, IL-15 signals are thought to be more important for the homeostasis of memory CD8 T cells than other T cell subsets. Signaling through the IL-15 receptor is known to be coupled to Jak1 and Jak3 activation and phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of STAT3 and STAT5 [84, 85]. Additionally, IL-15 signaling in T cells results in the phosphorylation p56lck and p72syk, induction of the MAP kinase pathway, and induction of Bcl-2 [4, 86]. These signals are important for the survival of T cell populations, especially memory populations whose survival is dependent on cytokine stimulation and independent of antigen.

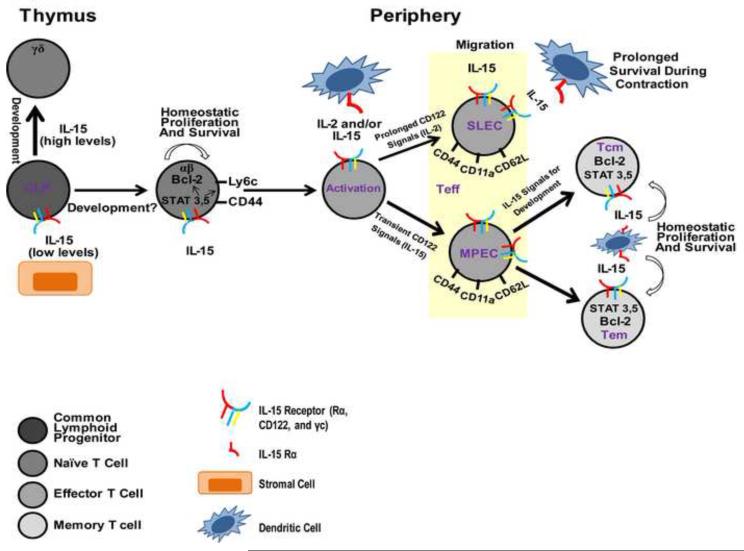

Paralleling NK cells, IL-15 signaling affects all phases of CD8 T cell biology, including their development, activation, proliferation, survival, and cytotoxicity (Figure 2). NK cells, however, appear to have much stricter requirements for IL-15 for their development than CD8 T cells. Original analyses of IL-15−/− and IL-15Rα−/− mice revealed reductions numbers of CD8 T cells that could be found in the periphery, but these deficiencies were largely restricted to the memory (CD44hi) population [31, 32]. These data would suggest that the early development of naïve TCRαβ CD8 T cells is minimally dependent on IL-15. Indeed, these findings are consistent with earlier studies that suggested that IL-15 is expressed only by thymic stromal epithelial cells and only at very low levels, which is important for promoting the development of TCRαβ T cells from thymic bipotential T/NK progenitor cells, as high concentrations of IL-15 promoted the development of TCRγδ CD8 T cells and NK cells instead [87]. Nonetheless, thymic IL-15 may subtly affect naïve CD8 T cell development. Although IL-7 is well-known to be critical in normal thymocyte development, γc−/− mice have a more severe thymocyte defect than IL-7Rα−/− mice [88, 89]. Furthermore, IL-7Rα−/− IL-2Rβ−/− double mutant mice display a similar thymic phenotype to γc−/− mice, while IL-7Rα−/− IL-2−/− double mutant mice phenotypically resemble IL-7Rα−/− mice [90]. These observations suggest that IL-7Rα independent signals that utilize IL-2Rβ and γ chains independently of IL-2 (likely IL-15) are important in fine-tuning thymocyte development [30].

Figrure 2

Once CD8 T cells have made their exodus from the thymus, IL-15 provides CD8 T cells in the periphery proliferative signals in steady-state conditions. This has been evidenced by the fact that lymphocytes from un-immunized IL-15Rα−/− mice proliferate at a lower rate in vivo compared with lymphocytes from normal mice [31]. In reverse experiments, injection of IL-15 causes the selective proliferation of memory phenotype CD8+ T cells [76]. Consistent with these findings, IL-15 transgenic mice that over-express IL-15 have increased numbers of memory phenotype CD8 T cells [91, 92], and delivery of IL-15 complexed to its Rα chain induces the robust proliferation of memory phenotype CD8 T cells and (to a lesser extent) naïve CD8 T cells [51]. There is evidence, however, that even this naïve CD8 T cell reponse to IL-15 complex depends on interactions with MHC I and the avidity of the TCR [93]. Thus, in the absence of an antigenic stimulus, IL-15 delivers a proliferative signal to CD8 T cells; however, it remains unclear how important this signal is to naïve CD8 T cells in the periphery, as all of these studies together implicate a more important role for IL-15 in the proliferation of memory (or at least memory phenotype) CD8 T cells.

While IL-15 may support the basal proliferation of naïve CD8 T cells to some degree, it may be important for their proliferation in lymphopenic environments. When T cells are transferred into lymphopenic conditions, IL-15 is a potent inducer of homeostatic proliferation. In experimental models of homeostatic proliferation, small numbers of T cells (e.g. (1–2) × 106 cells per mouse) are transferred into either constitutively (e.g. RAG-1−/− or RAG-2−/− mice), or transiently (e.g. sublethally irradiated or anti-TCR mAb treated) lymphopenic mice. Transfer of naive T cells into sublethally irradiated IL-15−/− hosts leads to reduced proliferation compared with normal hosts (although this deficit is not as profound as in IL-7−/− hosts) [94-96]. The increased expression of IL-2Rβ on naive T cells undergoing homeostatic proliferation suggests that signals delivered through IL-2R β containing receptors may involved in this process, and IL-15 appears to be an important signal not for initiating homeostatic proliferation, but rather for its continuation [97]. Interestingly, naïve CD8 T cells homeostatically proliferating or proliferating in response to IL-15 complexes acquire a memory-like phenotype, expressing CD44, Ly6c, and CD69 [51, 98]. Thus, IL-15 contributes to the sustained homeostatic proliferation and possibly the phenotypic conversion of naive cells during this process.

In addition to providing the stimulus for CD8 T cells to proliferate, IL-15 has been shown to be an important survival factor for these cells. IL-15 can protect lymphocytes from undergoing programmed cell death; although, this function may not be independent of its ability to promote proliferation, as IL-15 appears partially influence cell survival by causing them to enter the cell cycle [30]. In vitro, the induction of anti-Fas-mediated apoptosis can be prevented in cultures of concanavalin A-treated human T lymphocytes by the addition of IL-15 to these cultures [99]. Co-culture with IL-15 also rescued ex-vivo T cells from AD10 transgenic mice that were induced to undergo apoptosis by previous injection of with the Vβ3 family inducing superantigen SEA [100]. A role for IL-15 in preventing cell death has also been demonstrated in vivo by protection of mice injected with an anti-Fas antibody with administration of a chimeric human IL-15-murine IgG2b fusion protein [99]. Thus, IL-15 is able to protect T cells against apoptotic cell death. All the mechanisms by which IL-15 protects cells from undergoing programmed cell death in different circumstances have not been fully delineated, but IL-15 is known to upregulate expression of anti-apoptotic proteins (most notably Bcl-2) and cause entry into the cell cycle.

Initial activation of CD8 T cells is a consequence of engagement of specific TCR and peptide-loaded MHC I molecules on APCs and non-specific engagement of costimulatory molecules. These events proceed independently of any cytokine signaling; however, these events bring T cells into close and prolonged interactions with APCs during which APCs can provide multiple cytokine stimuli, an important one of which is transpresented IL-15. Expression of both IL-15Rα and CD122 increases after TCR activation, and heterologous IL-15 can support the survival and/or proliferation of activated T cells [100]. Similarly, addition of IL-15 to mice augmented specific T cell proliferation and cytoxicity to SIINFEKL-pulsed DCs [101]. Contact with IL-15 and especially signaling through CD122 seem to be essential factors in differentiating activated CD8 T cells. Whereas strong, prolonged signaling through CD122—effected by IL-2 binding—promotes terminal effector differentiation, weaker and intermediate-strength signaling through CD122—effected by IL-15 binding—promotes central memory development and survival [102]. This is consistent with evidence that IL-2, but not IL-15, is essential for the generation of primary effector responses [103] and the dispensability of IL-15 in primary CD8 T cell responses to various pathogens (discussed below). Although these cells are generated in the absence of IL-15 signaling, the prolonged survival of effector CTLs through the contraction phase is highly dependent on IL-15 [104, 105], and this is especially true of CD127lo, KLRG-1hi short-lived effector cells [105, 106]. The long-term maintenance of established memory pools of CD8 T cells is thought to be highly dependent on IL-15 transpresentation, but recent evidence suggests that primary human CD8 T cells do not require transpresentation of human IL-15 in vitro [107]. While human CD8 T cell proliferation can be boosted by IL-15 transpresentation [108], cis-presentation (IL-15 bound to IL-15Rα is presented to CD122/γc heterodimers on the same cell surface) occurs more efficiently in the human receptor-ligand combination than in that of the mouse system [107]. These results imply that the maintenance of memory CD8 T cells may be achieved via distinct mechanisms in humans and mice, though both systems utilize IL-15 signaling to achieve lasting populations of memory CD8 T cells.

As early as 1995—only a year after its discovery—a role for IL-15 in the chemoattraction of T cells was described [109]. IL-15-induced migration of T cells is likely very important for the arrival of effector CTLs at sites of inflammation and/or infection. In models of rheumatoid arthritis, for example, IL-15 is abundant in synovial fluid and can the migration of human PBMCs in vitro [110]. In responses to influenza infection, IL-15 has been shown to induce the migration of effector CD8 T cells to the lung airways [111]. Similar to the IL-15-induced migration of NK cells, it is unclear whether chemoattraction of T cells by IL-15 is a result of direct chemotaxis, indirect modulation of molecules important for lymphocyte migration, or some combination of the two. IL-15 has been shown to induce the expression of both chemokines and their receptors in T cells, and IL-15 promotes T cell extravasation through endothelial cells via a CD44-dependent mechanism [112]. The expression of the adhesion molecules CD44, LFA-1, and CD62-L are aberrantly expressed on CD8 T cells from IL-15Rα−/− mice, and splenocytes from IL-15Rα−/− mice were less efficient than normal splenocytes at entering peripheral lymphoid organs after intravenous injection [31].

Therefore, in parallel to the many ways in which IL-15 regulates NK cell biology, IL-15 represents an integral part of shaping anti-viral CD8 T cell responses. IL-15 promotes the survival and proliferation of CD8 T cells at all stages of the immune responses (especially the memory phase), enhances the cytoxicity of effector CD8 T cells, and signals T cells either directly or indirectly to enter infected locales.

3. IL-15 and Anti-Viral Immunity

3.1 Systemic Viral Infections

The effects of IL-15 on the outcome of virally-mediated diseases vary greatly from virus to virus. Because IL-15 is a potent activator of NK and CD8 T cell populations, viral diseases whose control largely depends on NK and CD8 T cell may be aggravated by an IL-15 deficiency whereas viruses that cause lympho-proliferative disorders may be ameliorated be the loss of IL-15. One such example of the latter is human T cell lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV-1). HTLV-1 causes a neurological disease termed HTLV-1-associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis (HAM/TSP) with clinical manifestations similar to those of multiple sclerosis. The increased proliferation of lymphocytes in HAM/TSP-infected individuals can be partially attributed to increased expression of IL-15Rα and increased production of the cytokine itself, and blocking antibodies against IL-15 or its receptor blocks some proliferation [113, 114]. In addition to increasing their proliferation, IL-15 signaling may also increase the activation status of lymphocytes in these patients by enhancing their effector capabilities, causing spontaneous degranulation and IFNγ secretion [115]. Thus, in diseases such as HAM/TSP, wherein viral infection results in expansion of the lymphocyte pool, blocking IL-15 signaling may be an important therapeutic option. In fact, the humanized antibody Mikβ1, a blocking antibody against CD122 is in clinical trials for HAM/TSP patients (http://clinicaltrails.gov).

In viral infections, far more common than the desire to reduce lymphocyte proliferation and activation is the desire to augment lymphocyte numbers and cytotoxicity to such a degree that they are potent effectors able to control and eliminate the viral pathogens. The potential role for IL-15 in this process has been investigated in a variety of models of viral pathogens. An absence of IL-15 poses no problems in the acute phase of infection with either vesicular stomatitis virus or lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus, as IL-15−/− mice clear these viruses [70, 71, 80]. In contrast to the unaltered control of viral load in IL-15−/− mice infected with VSV or LCMV, infection of IL-15−/− mice with vaccinia virus results in a loss of control of viral replication, and these animals succumb to infection [32]. These differences likely reflect differential roles for NK cells in immune responses to these viruses. NK cells are thought to help control the initial replication of vaccinia virus, but robust NK cell responses to LCMV play little role in viral clearance and may actually be immunoregulatory, suppressing T cell responses that are critical in controlling this infection [116]. Regardless of whether or not IL-15 is necessary for NK cell responses and/or viral clearance, IL-15 is not unimportant in immune responses to VSV and LCMV infections. Models of intravenous infection of mice with these viruses have revealed that IL-15 is important for the generation of antigen-specific memory CD8 T cells responding to VSV infection [80]. While a similar requirement for IL-15 in the generation of memory CD8 T cells was not observed following LCMV infection, in both viral infection models, IL-15 is requisite for the long-term maintenance of the antigen-specific memory CD8 T cells, as this population wanes dramatically over time following infection [70, 71, 80].

3.2 Tissue-Specific Viral Infections

In contrast to the gradual attrition of antigen-specific memory CD8 T cells in IL-15−/− mice infected with VSV or LCMV, IL-15−/− mice infected with either latent gammaherpesvirus (MHV-68) or influenza virus show no defects in the antigen-specific memory CD8 T cells [117, 118], even though the decline of these cells from specific sites (namely, the lung airways) has been associated with loss of IL-7 and IL-15 receptors [119]. This difference may be partially accounted for by the continual presence of antigen from reactivation of the gammaherpes virus [117], but viral persistence is likely not the main factor maintaining memory CD8 T cells in the absence of IL-15 following a low dose influenza infection, since IL-15−/− mice clear this virus with kinetics similar to wild type mice in primary and challenge infections ([118]and unpublished observations). IL-15-independent memory CD8 T cells in this model, then, may be a result of the mucosal environment in which these CD8 T cells are primed, since there is also no attrition of CD8 memory T cells following an intranasal infection with vesicular stomatitis virus [118]. Thus, immune responses primed in specific tissues may impart transcriptional programs on responding CD8 T cells that renders these cells more or less dependent on IL-15 for their homeostasis.

IL-15 is not required for positive disease outcome or maintenance of a memory CD8 T cell population in the aforementioned tissue-specific viral infections, but IL-15 is not unimportant in tissue-specific viral infections. It has been repeatedly observed that viruses induce expression of IL-15, and this expression is important for anti-viral responses by different lymphocyte populations. Infection with hepatitis B, for example, induces IL-15 expression, and low levels of circulating IL-15 are associated with high viremia and poor disease outcome [120]. In individuals infected with hepatitis C, there is no correlation between the disease and IL-15 expression, but in vitro studies have shown that IL-15 treatment promotes the proliferation and survival of NK cells, a cell population that is known to be important in the control of hepatitis C replication in the liver [121]. Thus, in both diseases, suboptimal production of IL-15 is correlated with the likelihood of the virus entering a chronic phase, presumably because protective NK cell responses cannot be maintained in absence of IL-15. IL-15 production is also known to be upregulated in response to respiratory viruses such as RSV [122] and influenza [111]. In the latter, local IL-15 production appears to be important for the optimal recruitment of NK and effector CD8 T cells to the site of infection and their prolonged survival in the lung airways [81, 111].

Following infection with herpes simplex virus-2 (HSV-2), IL-15−/− mice are unable to control the pathogen and the infection is lethal—effects thought to be mainly mediated by the lack of NK and NKT cells in these animals [123]. In vitro evidence corroborates these conclusions, as IL-15 has been shown to have antiviral effects on isolated human PBMCs infected with HSV-1, Epstein barr virus, or herpes virus-6, mainly through its action on NK cells [124], but additional studies with HSV-2 report a critical role for IL-15 in the innate immune response for protection independent of any action on natural killer cells [125]. These studies were further corroborated by more recent studies in which IL-15−/− mice were not protected against HSV-2, but wild type animals depleted of natural killer cells were [126]. Although it is somewhat unclear as to the mechanism by which IL-15 mediates protection in this herpes model, it is known that effective CD4 responses are essential for viral clearance, and IL-15 supports the basal proliferation of CD4 cells and enhances the TCR-dependent proliferation of Th1/Th17 (IFNγ, IL-17 double positive) cells [127]. However, over-expression of IL-15 during HSV-2 infection compromised CD4-mediated protection, presumably by expanding the CD8 T cell compartment to such an extent that it out-competed the CD4 compartment for limited resources [128]. On the whole, how IL-15 signaling affects the cell population most important for control of a pathogen determines the importance of IL-15 as an immune modulator in that system. Thus, it is of critical importance that the role of IL-15 be examined in individual infections: systemic or mucosal.

3.3 Chronic Viral Infection/HIV

The chronic virus-mediated disease in which immune intervention via IL-15 targeting has received the most attention is Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV). IL-15 treatment has been explored as a method of enhancing NK cell responses to control viral replication, immune restoration in patients in whom antiretroviral therapy is sufficient to suppress viral load but T cell counts remain low, and as a potential for vaccines designed to elicit robust T cell memory [129]. Non-human primate models are most widely used to investigate the immunological benefits of candidate therapies in immunodeficient settings. In SIV models, IL-15 has been shown to increase effector functions of specific CD8 T cells. In vitro, IFNγ production by CD8 T cells from SIV and SHIV-infected macaques was increased by IL-15 stimulation [130]. When administered as a treatment in vivo to chronically SIV infected macaques, IL-15 augmented populations of effector memory CD8 T cells [131]. IL-15 treatment has also been shown to augment populations of effector memory CD4 T cells in anti-retroviral treated animals [132]. Although IL-15 treatment had no effect on viral load in either of these studies, the ability to expand effector memory CD8 and CD4 T cell compartments reveal potential for this mode of treatment in immune reconstitution. In similar studies, a reduction in viral load was reported in animals co-immunized with IL-15 expression plasmids, but differences in viral titers were only discernible after the release of anti-retroviral treatment [133]. Additionally, IL-15 treatment alone or in combination with IL-2 was effective at inducing new CD4 and CD8 memory to influenza and tetanus toxins, indicating that IL-15 treatment may also be effective in ameliorating the severe consequences of coinfection in HIV-infected individuals [134]. In studies of human immunodeficiency virus (type 1), in vitro studies have revealed that IL-15 can increase IFNγ production and chemokine secretion by NK cells isolated from HIV-1-infected subjects [135]. Increased IFNγ production, enhanced cytotoxicity, and protection from apoptosis upon IL-15 treatment in vitro has also been shown for CD8 T cells isolated from HIV-1-infected subjects [136].

Although several studies suggest that IL-15 shows substantial promise as a therapeutic for HIV infections, evidence also exists that IL-15 may exacerbate disease. Because IL-15 treatment expands T cell populations, the treatment could increase viral targets and lead to increased viral load [129]. In models of acute SIV infection, IL-15 treatment increased viral setpoint by 3 logs and accelerated disease progression in 2 out of 6 animals [137], and as a vaccine adjuvant had no benefits [138]. In follow up studies attempting to address the mechanism by which IL-15 exacerbated disease, it was found that CD4 T cells cultured with IL-15 and/or SIV increased their density of CD4 expression, leading to higher infection levels [137]. These studies were supported by additional studies correlating high viremia during the acute phase of infection with high levels of IL-15 in plasma [139]. In models of chronic SIV infection, however, IL-15 treatment resulted in no difference in viral load when compared with the control group [140]. With regards to HIV-1, in vitro studies using isolated PBMCs stimulated with PHA indicated that IL-15 stimulation enhanced viral replication [141]. These observations that IL-15 could increase viral replication lead to the hypothesis that IL-15 might be an effective vaccine adjuvant, increasing the immunogenicity of the vaccination. Indeed, HIV DNA vaccines co-infected with the IL-15 gene enhanced CD8 T cell responses [142], and similar platforms in which DNA vaccines encoding SIV antigen were coinjected with an IL-15 containing plasmid were associated with enhanced protection from an SHIV (SHIV 89.6P) challenge when compared to animals receiving the vaccination alone [143]. Comparable studies, however, report no clinical differences between vaccinated and vaccinated plus IL-15-adjuvanted groups in terms of viral load, although adjuvanted animals did exhibit increases in SIVgag-specific T cell responses [144]. Finally, when IL-15 was employed to adjuvant a vaccine to a more virulent challenge virus, SIV mac251, the IL-15-induced proliferation of viral targets appeared to abrogate any benefits from the vaccine itself [145]. Therefore, while IL-15 seems to have little potential as an HIV vaccine adjuvant, the consistently reported expansion of effector memory T cell populations without disease exacerbation in the chronic phase suggests that IL-15 may be an effective therapeutic for immune reconstitution in HIV-infected individuals.

3.4 IL-15 and Immune Intervention to Viral Pathogens

Because IL-15 production in response to viral infection appears to an important mechanism of immune control, there has been considerable interest in trying to use IL-15 expression as a method of adjuvanting vaccines and/or improving immune responses to viral pathogens. These interests have been further encouraged by the development of IL-15-expression vectors and therapeutics for immune-intervention and reconstitution for HIV, and their application has been gradually expanded to include various other viral pathogens (Table 1). Indeed, such strategies have met some successes. A vaccinia-virus-based vaccine platform was engineered to express the hemagglutinin and neuraminidase from H5N1 influenza viruses as well as IL-15. This vaccine induced cross-neutralizing antibody responses and robust cellular immune responses that conferred cross-clade protection to mice challenged with different H5N1 viruses [146]. Intranasal delivery of recombinant IL-15 complexed to its Rα chain has also been therapeutically exploited following influenza infection. Introduction of IL-15 complexes to the lung airways of influenza-infected mice lead to enhanced lymphocyte migration to the site of infection and improved control of viral replication early and during challenge infections ([111] and unpublished observations). Additionally, a smallpox vaccine with integrated IL-15 has been shown to protect cynomolgus monkeys from a lethal dose of monkeypox virus administered three years post vaccination [147]. Enhanced immune responses to plasmid DNA vaccination by IL-15 was also reported against hepatitis B surface antigen [148] and the HSV-1 glycoprotein B [149]. However, not all attempts have yielded such promising results. Immunizing rhesus macaques with different doses of IL-15 expressing plasmid in an influenza immunogenecity model, Yin et al. found that whereas low doses of IL-15 were effective at improving T cell responses, high doses of IL-15 (4mg) decreased production of IFNγ and T cell proliferation [150]. These data highlight the importance of optimizing adjuvants but overall reveal a significant potential for IL-15 as an effective strategy for improving vaccines to viruses.

Table 1.

Strategies of IL-15 therapies in virus-mediated diseases.

| Disease | Treatment | Effects | Model | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HAM/TSP | Humanized MIKβ1 (anti CD122) |

Reduced Lymphocyte Proliferation and Activation |

Human Clinical Trials |

Humanclinicaltrials.gov |

| SHIV (SHIV89.6P) |

SHIV Plasmid DNA + IL-15 Expression Plasmid |

More Rapid Control of Challenge Infection |

Rhesus Macaques |

[139] |

| SHIV (SHIV89.6P) |

SHIV Plasmid DNA + IL-15 Expression Plasmid |

No Effect | Rhesus Macaques |

[140] |

| SIV (SIVmac251) |

SIV Plasmid DNA + IL-15 Expression Plasmid |

Abrogation of Vaccine Benefits with Cytokine Adjuvant |

Rhesus Macaques |

[141] |

| SIV (SIVmac251) |

SIV Plasmid DNA + IL-15 Expression Plasmid and a Replicating Adenovirus-SIV with SIV Protein Boosting |

No Control of Vaginal Challenge | Rhesus Macaques |

[134] |

| Chronic SIV (SIVmac251) |

1°: SIV Plasmid DNA + ART Boost: SIV Plasmid DNA + IL-15/IL-15Rα Expression Plasmid |

Increased T Cell Responses and Decreased Viral Load After Release of ART Treatment |

Rhesus Macaques |

[129] |

| Influenza | Vaccina Virus Expressing Influenza Coat Proteins and IL-15 |

Increased Cellular and Humoral Responses and Cross-Clade Protection Against a Variety of H5N1 Challenge Infections |

Mice (BALB/c) |

[142] |

| Influenza | H3N2 Immunization + Intranasal IL-15/IL-15Rα Complexes |

Increased Specific T Cell Responses and Enhanced Clearance of H1N1 Challenge |

Mice (C57Bl/6) |

[114] |

| Monkeypox | Smallpox Vaccine (Wyeth Vaccinia) with Integrated IL- 15 |

Milder Symptoms and Enhanced Recovery to Challenge with Lethal Monkeypox (Zaire 79 MA-104) |

Cynomolgus Monkeys |

[143] |

| Hepatitis B | Hep B Plasmid DNA + IL-15 Expression Plasmid |

Enhanced Specific T Cell Responses |

Mice (BALB/cJ) |

[144] |

| HSV-1 | HSV-1 Plasmid DNA + IL- 15 Expression Plasmid |

Elevated Survival Rates After Lethal HSV-1 Challenge |

Mice (BALB/c) |

[145] |

| Influenza | Influenza Plasmid DNA + Low or High Dose IL-15 Expression Plasmid |

Low Dose IL-15: Increased T Cell Responses High Dose IL-15: Decreased T Cell Responses *No Differences in Hemagglutinin Inhibition Antibody Titers |

Rhesus Macaques |

[146] |

4. Conclusions

The wide range of functions from IL-15 signaling in so many different cell types makes IL-15 an attractive target for immune intervention, but also demands caution in doing so. The many shared receptor components results in functional redundancy with other cytokines, and the broad tissue distribution of IL-15Rα, the potential to activate multiple signaling pathways, and the layered regulation of cytokine expression all dictate that the context in which a cell encounters IL-15 will be critical in determining the functional output of that cell type. An important consideration is that IL-15 is known to signal through several receptor permutations. Classically, and importantly for its role in maintaining NK and T cell populations, IL-15 is transpresented to responsive cells expressing CD122 and CD132 by cells expressing the cytokine itself and R [10, 30, 151]. It has also been demonstrated, though, that soluble IL-15 is able to signal through the high affinity heterotrimeric receptor complex [152], an intermediate affinity dimeric receptor consisting of CD132 and R [153], and through the receptor alpha chain alone [4, 154, 155]. Although these numerous potential signaling pathways of IL-15 complicate the ability to develop IL-15 as an effective immune therapy, they also help explain how IL-15 mediates so many diverse functions and provides opportunities for more focused or targeted immune therapies.

Abbreviations

- IL-15

(interleukin-15)

- γc

(common gamma chain)

- NK

(natural killer)

- Teff

(effector T cells)

- Tmem

(memory T cells)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

IL-15 has been implicated in the development and immunobiology of both NK and CD8 T cells Virally induced IL-15 influences the migration and effector function of NK and CD8 T cells IL-15 has great potential for modulating anti-viral immune responses and vaccine development

References

- [1].Bamford RN, Grant AJ, Burton JD, Peters C, Kurys G, Goldman CK, et al. The interleukin (IL) 2 receptor beta chain is shared by IL-2 and a cytokine, provisionally designated IL-T, that stimulates T-cell proliferation and the induction of lymphokine-activated killer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:4940–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.11.4940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Grabstein KH, Eisenman J, Shanebeck K, Rauch C, Srinivasan S, Fung V, et al. Cloning of a T cell growth factor that interacts with the beta chain of the interleukin-2 receptor. Science. 1994;264:965–8. doi: 10.1126/science.8178155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Bamford RN, Battiata AP, Burton JD, Sharma H, Waldmann TA. Interleukin (IL) 15/IL-T production by the adult T-cell leukemia cell line HuT-102 is associated with a human T-cell lymphotrophic virus type I region /IL-15 fusion message that lacks many upstream AUGs that normally attenuates IL-15 mRNA translation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:2897–902. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.7.2897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Budagian V, Bulanova E, Paus R, Bulfone-Paus S. IL-15/IL-15 receptor biology: a guided tour through an expanding universe. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2006;17:259–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Bazan JF. Structural design and molecular evolution of a cytokine receptor superfamily. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:6934–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.18.6934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Anderson DM, Kumaki S, Ahdieh M, Bertles J, Tometsko M, Loomis A, et al. Functional characterization of the human interleukin-15 receptor alpha chain and close linkage of IL15RA and IL2RA genes. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:29862–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.50.29862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Giri JG, Ahdieh M, Eisenman J, Shanebeck K, Grabstein K, Kumaki S, et al. Utilization of the beta and gamma chains of the IL-2 receptor by the novel cytokine IL-15. EMBO J. 1994;13:2822–30. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06576.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Giri JG, Anderson DM, Kumaki S, Park LS, Grabstein KH, Cosman D. IL-15, a novel T cell growth factor that shares activities and receptor components with IL-2. J Leukoc Biol. 1995;57:763–6. doi: 10.1002/jlb.57.5.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Giri JG, Kumaki S, Ahdieh M, Friend DJ, Loomis A, Shanebeck K, et al. Identification and cloning of a novel IL-15 binding protein that is structurally related to the alpha chain of the IL-2 receptor. EMBO J. 1995;14:3654–63. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00035.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Dubois S, Mariner J, Waldmann TA, Tagaya Y. IL-15Ralpha recycles and presents IL-15 In trans to neighboring cells. Immunity. 2002;17:537–47. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00429-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Wuest SC, Edwan JH, Martin JF, Han S, Perry JS, Cartagena CM, et al. A role for interleukin-2 trans-presentation in dendritic cell-mediated T cell activation in humans, as revealed by daclizumab therapy. Nat Med. 2011;17:604–9. doi: 10.1038/nm.2365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Waldmann TA, Dubois S, Tagaya Y. Contrasting roles of IL-2 and IL-15 in the life and death of lymphocytes: implications for immunotherapy. Immunity. 2001;14:105–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Carson WE, Giri JG, Lindemann MJ, Linett ML, Ahdieh M, Paxton R, et al. Interleukin (IL) 15 is a novel cytokine that activates human natural killer cells via components of the IL-2 receptor. J Exp Med. 1994;180:1395–403. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.4.1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Kennedy MK, Park LS. Characterization of interleukin-15 (IL-15) and the IL-15 receptor complex. J Clin Immunol. 1996;16:134–43. doi: 10.1007/BF01540911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Armitage RJ, Macduff BM, Eisenman J, Paxton R, Grabstein KH. IL-15 has stimulatory activity for the induction of B cell proliferation and differentiation. J Immunol. 1995;154:483–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Lenardo MJ. Fas and the art of lymphocyte maintenance. J Exp Med. 1996;183:721–4. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.3.721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Marks-Konczalik J, Dubois S, Losi JM, Sabzevari H, Yamada N, Feigenbaum L, et al. IL-2-induced activation-induced cell death is inhibited in IL-15 transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:11445–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.200363097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Ma A, Koka R, Burkett P. Diverse functions of IL-2, IL-15, and IL-7 in lymphoid homeostasis. Annu Rev Immunol. 2006;24:657–79. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.24.021605.090727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Angiolillo AL, Kanegane H, Sgadari C, Reaman GH, Tosato G. Interleukin-15 promotes angiogenesis in vivo. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;233:231–7. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Quinn LS, Anderson BG, Drivdahl RH, Alvarez B, Argiles JM. Overexpression of interleukin-15 induces skeletal muscle hypertrophy in vitro: implications for treatment of muscle wasting disorders. Exp Cell Res. 2002;280:55–63. doi: 10.1006/excr.2002.5624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Verma S, Hiby SE, Loke YW, King A. Human decidual natural killer cells express the receptor for and respond to the cytokine interleukin 15. Biol Reprod. 2000;62:959–68. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod62.4.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Stone KP, Kastin AJ, Pan W. NFkB is an unexpected major mediator of interleukin-15 signaling in cerebral endothelia. Cellular physiology and biochemistry: international journal of experimental cellular physiology, biochemistry, and pharmacology. 2011;28:115–24. doi: 10.1159/000331720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Alvarez B, Carbo N, Lopez-Soriano J, Drivdahl RH, Busquets S, Lopez-Soriano FJ, et al. Effects of interleukin-15 (IL-15) on adipose tissue mass in rodent obesity models: evidence for direct IL-15 action on adipose tissue. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1570:33–7. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(02)00148-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Bamford RN, DeFilippis AP, Azimi N, Kurys G, Waldmann TA. The 5′ untranslated region, signal peptide, and the coding sequence of the carboxyl terminus of IL-15 participate in its multifaceted translational control. J Immunol. 1998;160:4418–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Bamford RN, Battiata AP, Waldmann TA. IL-15: the role of translational regulation in their expression. J Leukoc Biol. 1996;59:476–80. doi: 10.1002/jlb.59.4.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Tagaya Y, Bamford RN, DeFilippis AP, Waldmann TA. IL-15: a pleiot ropic cytokine with diverse receptor/signaling pathways whose expression is controlled at multiple levels. Immunity. 1996;4:329–36. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80246-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Di Sabatino A, Calarota SA, Vidali F, Macdonald TT, Corazza GR. Role of IL-15 in immune-mediated and infectious diseases. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2011;22:19–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2010.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Sun JC, Lanier LL. NK cell development, homeostasis and function: parallels with CD8 T cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:645–57. doi: 10.1038/nri3044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Vosshenrich CA, Ranson T, Samson SI, Corcuff E, Colucci F, Rosmaraki EE, et al. Roles for common cytokine receptor gamma-chain-dependent cytokines in the generation, differentiation, and maturation of NK cell precursors and peripheral NK cells in vivo. J Immunol. 2005;174:1213–21. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.3.1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Lodolce J, Burkett P, Koka R, Boone D, Chien M, Chan F, et al. Interleukin-15 and the regulation of lymphoid homeostasis. Mol Immunol. 2002;39:537–44. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(02)00211-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Lodolce JP, Boone DL, Chai S, Swain RE, Dassopoulos T, Trettin S, et al. IL-15 receptor maintains lymphoid homeostasis by supporting lymphocyte homing and proliferation. Immunity. 1998;9:669–76. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80664-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Kennedy MK, Glaccum M, Brown SN, Butz EA, Viney JL, Embers M, et al. Reversible defects in natural killer and memory CD8 T cell lineages in interleukin 15-deficient mice. J Exp Med. 2000;191:771–80. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.5.771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].DiSanto JP. Cytokines: shared receptors, distinct functions. Curr Biol. 1997;7:R424–6. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00208-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Puzanov IJ, Bennett M, Kumar V. IL-15 can substitute for the marrow microenvironment in the differentiation of natural killer cells. J Immunol. 1996;157:4282–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Ogasawara K, Hida S, Azimi N, Tagaya Y, Sato T, Yokochi-Fukuda T, et al. Requirement for IRF-1 in the microenvironment supporting development of natural killer cells. Nature. 1998;391:700–3. doi: 10.1038/35636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Ohteki T, Ho S, Suzuki H, Mak TW, Ohashi PS. Role for IL-15/IL-15 receptor beta-chain in natural killer 1.1+ T cell receptor-alpha beta+ cell development. J Immunol. 1997;159:5931–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Gascoyne DM, Long E, Veiga-Fernandes H, de Boer J, Williams O, Seddon B, et al. The basic leucine zipper transcription factor E4BP4 is essential for natural killer cell development. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:1118–24. doi: 10.1038/ni.1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Kamizono S, Duncan GS, Seidel MG, Morimoto A, Hamada K, Grosveld G, et al. Nfil3/E4bp4 is required for the development and maturation of NK cells in vivo. J Exp Med. 2009;206:2977–86. doi: 10.1084/jem.20092176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Moretta L, Bottino C, Pende D, Vitale M, Mingari MC, Moretta A. Different checkpoints in human NK-cell activation. Trends Immunol. 2004;25:670–6. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Vivier E, Tomasello E, Baratin M, Walzer T, Ugolini S. Functions of natural killer cells. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:503–10. doi: 10.1038/ni1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Kawamura T, Koka R, Ma A, Kumar V. Differential roles for IL-15R alpha-chain in NK cell development and Ly-49 induction. J Immunol. 2003;171:5085–90. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.10.5085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Yoshizawa K, Nakajima S, Notake T, Miyagawa S, Hida S, Taki S. IL-15-High-Responder Developing NK Cells Bearing Ly49 Receptors in IL-15−/− Mice. J Immunol. 2011;187:5162–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Lee GA, Liou YH, Wang SW, Ko KL, Jiang ST, Liao NS. Different NK cell developmental events require different levels of IL-15 trans-presentation. J Immunol. 2011;187:1212–21. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Soderquest K, Powell N, Luci C, van Rooijen N, Hidalgo A, Geissmann F, et al. Monocytes control natural killer cell differentiation to effector phenotypes. Blood. 2011;117:4511–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-10-312264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Pek EA, Chan T, Reid S, Ashkar AA. Characterization and IL-15 dependence of NK cells in humanized mice. Immunobiology. 2011;216:218–24. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2010.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Cooper MA, Bush JE, Fehniger TA, VanDeusen JB, Waite RE, Liu Y, et al. In vivo evidence for a dependence on interleukin 15 for survival of natural killer cells. Blood. 2002;100:3633–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2001-12-0293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Koka R, Burkett PR, Chien M, Chai S, Chan F, Lodolce JP, et al. Interleukin (IL)-15 R[alpha]-deficient natural killer cells survive in normal but not IL-15R[alpha]-deficient mice. J Exp Med. 2003;197:977–84. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Huntington ND, Puthalakath H, Gunn P, Naik E, Michalak EM, Smyth MJ, et al. Interleukin 15-mediated survival of natural killer cells is determined by interactions among Bim, Noxa and Mcl-1. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:856–63. doi: 10.1038/ni1487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Prlic M, Blazar BR, Farrar MA, Jameson SC. In vivo survival and homeostatic proliferation of natural killer cells. J Exp Med. 2003;197:967–76. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Castillo EF, Stonier SW, Frasca L, Schluns KS. Dendritic cells support the in vivo development and maintenance of NK cells via IL-15 trans-presentation. J Immunol. 2009;183:4948–56. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Stoklasek TA, Schluns KS, Lefrancois L. Combined IL-15/IL-15Ralpha immunotherapy maximizes IL-15 activity in vivo. J Immunol. 2006;177:6072–80. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.9.6072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Pillet AH, Theze J, Rose T. Interleukin (IL)-2 and IL-15 have different effects on human natural killer lymphocytes. Hum Immunol. 2011;72:1013–7. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2011.07.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Minagawa M, Watanabe H, Miyaji C, Tomiyama K, Shimura H, Ito A, et al. Enforced expression of Bcl-2 restores the number of NK cells, but does not rescue the impaired development of NKT cells or intraepithelial lymphocytes, in IL-2/IL-15 receptor beta-chain-deficient mice. J Immunol. 2002;169:4153–60. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.8.4153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Park JY, Lee SH, Yoon SR, Park YJ, Jung H, the cytolytic activity of human natural kill. Kim TD, et al. IL-15-induced IL-10 increases er cells. Molecules and cells. 2011;32:265–72. doi: 10.1007/s10059-011-1057-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Moustaki A, Argyropoulos KV, Baxevanis CN, Papamichail M, Perez SA. Effect of the simultaneous administration of glucocorticoids and IL-15 on human NK cell phenotype, proliferation and function. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2011;60:1683–95. doi: 10.1007/s00262-011-1067-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Gerosa F, Baldani-Guerra B, Nisii C, Marchesini V, Carra G, Trinchieri G. Reciprocal activating interaction between natural killer cells and dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2002;195:327–33. doi: 10.1084/jem.20010938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Koka R, Burkett P, Chien M, Chai S, Boone DL, Ma A. Cutting edge: murine dendritic cells require IL-15R alpha to prime NK cells. J Immunol. 2004;173:3594–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.6.3594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Elpek KG, Rubinstein MP, Bellemare-Pelletier A, Goldrath AW, Turley SJ. Mature natural killer cells with phenotypic and functional alterations accumulate upon sustained stimulation with IL-15/IL-15Ralpha complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:21647–52. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012128107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Dokun AO, Chu DT, Yang L, Bendelac AS, Yokoyama WM. Analysis of in situ NK cell responses during viral infection. J Immunol. 2001;167:5286–93. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.9.5286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Allavena P, Giardina G, Bianchi G, Mantovani A. IL-15 is chemotactic for natural killer cells and stimulates their adhesion to vascular endothelium. J Leukoc Biol. 1997;61:729–35. doi: 10.1002/jlb.61.6.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Barlic J, Sechler JM, Murphy PM. IL-15 and IL-2 oppositely regulate expression of the chemokine receptor CX3CR1. Blood. 2003;102:3494–503. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-03-0946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Barlic J, McDermott DH, Merrell MN, Gonzales J, Via LE, Murphy PM. Interleukin (IL)-15 and IL-2 reciprocally regulate expression of the chemokine receptor CX3CR1 through selective NFAT1- and NFAT2-dependent mechanisms. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:48520–34. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406978200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Sechler JM, Barlic J, Grivel JC, Murphy PM. IL-15 alters expression and function of the chemokine receptor CX3CR1 in human NK cells. Cell Immunol. 2004;230:99–108. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2004.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Carroll HP, Paunovic V, Gadina M. Signalling, inflammation and arthritis: Crossed signals: the role of interleukin-15 and -18 in autoimmunity. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008;47:1269–77. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ken257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Dubsky P, Saito H, Leogier M, Dantin C, Connolly JE, Banchereau J, et al. IL-15-induced human DC efficiently prime melanoma-specific naive CD8+ T cells to differentiate into CTL. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:1678–90. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Pulendran B, Dillon S, Joseph C, Curiel T, Banchereau J, Mohamadzadeh M. Dendritic cells generated in the presence of GM-CSF plus IL-15 prime potent CD8+ Tc1 responses in vivo. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:66–73. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Kuwajima S, Sato T, Ishida K, Tada H, Tezuka H, Ohteki T. Interleukin 15-dependent crosstalk between conventional and plasmacytoid dendritic cells is essential for CpG-induced immune activation. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:740–6. doi: 10.1038/ni1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Ruckert R, Brandt K, Bulanova E, Mirghomizadeh F, Paus R, Bulfone-Paus S. Dendritic cell-derived IL-15 controls the induction of CD8 T cell immune responses. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:3493–503. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Feau S, Facchinetti V, Granucci F, Citterio S, Jarrossay D, Seresini S, et al. Dendritic cell-derived IL-2 production is regulated by IL-15 in humans and in mice. Blood. 2005;105:697–702. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Becker TC, Wherry EJ, Boone D, Murali-Krishna K, Antia R, Ma A, et al. Interleukin 15 is required for proliferative renewal of virus-specific memory CD8 T cells. J Exp Med. 2002;195:1541–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Wherry EJ, Becker TC, Boone D, Kaja MK, Ma A, Ahmed R. Homeostatic proliferation but not the generation of virus specific memory CD8 T cells is impaired in the absence of IL-15 or IL-15Ralpha. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2002;512:165–75. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0757-4_22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Harris KM. Monocytes differentiated with GM-CSF and IL-15 initiate Th17 and Th1 responses that are contact-dependent and mediated by IL-15. J Leukoc Biol. 2011;90:727–34. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0311132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Hardy MY, Kassianos AJ, Vulink A, Wilkinson R, Jongbloed SL, Hart DN, et al. NK cells enhance the induction of CTL responses by IL-15 monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Immunol Cell Biol. 2009;87:606–14. doi: 10.1038/icb.2009.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Mattei F, Schiavoni G, Belardelli F, Tough DF. IL-15 is expressed by dendritic cells in response to type I IFN, double-stranded RNA, or lipopolysaccharide and promotes dendritic cell activation. J Immunol. 2001;167:1179–87. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.3.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Kuniyoshi JS, Kuniyoshi CJ, Lim AM, Wang FY, Bade ER, Lau R, et al. Dendritic cell secretion of IL-15 is induced by recombinant huCD40LT and augments the stimulation of antigen-specific cytolytic T cells. Cell Immunol. 1999;193:48–58. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1999.1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Zhang X, Sun S, Hwang I, Tough DF, Sprent J. Potent and selective stimulation of memory-phenotype CD8+ T cells in vivo by IL-15. Immunity. 1998;8:591–9. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80564-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Ishii H, Takahara M, Nagato T, Kis LL, Nagy N, Kishibe K, et al. Monocytes enhance cell proliferation and LMP1 expression of nasal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma cells by cell contact-dependent interaction through membrane-bound IL-15. Int J Cancer. 2012;130:48–58. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Boudreau JE, Stephenson KB, Wang F, Ashka r AA, Mossman KL, Lenz LL, et al. IL-15 and type I interferon are required for activation of tumoricidal NK cells by virus-infected dendritic cells. Cancer Res. 2011;71:2497–506. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Vujanovic L, Szymkowski DE, Alber S, Watkins SC, Vujanovic NL, Butterfield LH. Virally infected and matured human dendritic cells activate natural killer cells via cooperative activity of plasma membrane-bound TNF and IL-15. Blood. 2010;116:575–83. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-240325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Schluns KS, Williams K, Ma A, Zheng XX, Lefrancois L. Cutting edge: requirement for IL-15 in the generation of primary and memory antigen-specific CD8 T cells. J Immunol. 2002;168:4827–31. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.10.4827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].McGill J, Van Rooijen N, Legge KL. IL-15 trans-presentation by pulmonary dendritic cells promotes effector CD8 T cell survival during influenza virus infection. J Exp Med. 2010;207:521–34. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Oh S, Perera LP, Terabe M, Ni L, Waldmann TA, Berzofsky JA. IL-15 as a mediator of CD4+ help for CD8+ T cell longevity and avoidance of TRAIL-mediated apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:5201–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801003105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Bodnar A, Nizsaloczki E, Mocsar G, Szaloki N, Waldmann TA, Damjanovich S, et al. A biophysical approach to IL-2 and IL-15 receptor function: localization, conformation and interactions. Immunol Lett. 2008;116:117–25. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2007.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Johnston JA, Bacon CM, Finbloom DS, Rees RC, Kaplan D, Shibuya K, et al. Tyrosine phosphorylation and activation of STAT5, STAT3, and Janus kinases by interleukins 2 and 15. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:8705–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.19.8705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Lin JX, Migone TS, Tsang M, Friedmann M, Weatherbee JA, Zhou L, et al. The role of shared receptor motifs and common Stat proteins in the generation of cytokine pleiotropy and redundancy by IL-2, IL-4, IL-7, IL-13, and IL-15. Immunity. 1995;2:331–9. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90141-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Miyazaki T, Liu ZJ, Kawahara A, Minami Y, Yamada K, Tsujimoto Y, et al. Three distinct IL-2 signaling pathways mediated by bcl-2, c-myc, and lck cooperate in hematopoietic cell proliferation. Cell. 1995;81:223–31. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90332-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Leclercq G, Debacker V, de Smedt M, Plum J. Differential effects of interleukin-15 and interleukin-2 on differentiation of bipotential T/natural killer progenitor cells. J Exp Med. 1996;184:325–36. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.2.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Cao X, Shores EW, Hu-Li J, Anver MR, Kelsall BL, Russell SM, et al. Defective lymphoid development in mice lacking expression of the common cytokine receptor gamma chain. Immunity. 1995;2:223–38. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90047-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Peschon JJ, Morrissey PJ, Grabstein KH, Ramsdell FJ, Maraskovsky E, Gliniak BC, et al. Early lymphocyte expansion is severely impaired in interleukin 7 receptor-deficient mice. J Exp Med. 1994;180:1955–60. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.5.1955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Porter BO, Malek TR. IL-2Rbeta/IL-7Ralpha doubly deficient mice recapitulate the thymic and intraepithelial lymphocyte (IEL) developmental defects of gammac−/− mice: roles for both IL-2 and IL-15 in CD8alphaalpha IEL development. J Immunol. 1999;163:5906–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Yajima T, Nishimura H, Ishimitsu R, Watase T, Busch DH, Pamer EG, et al. Overexpression of IL-15 in vivo increases antigen-driven memory CD8+ T cells following a microbe exposure. J Immunol. 2002;168:1198–203. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.3.1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Fehniger TA, Suzuki K, Ponnappan A, VanD eusen JB, Cooper MA, Florea SM, et al. Fatal leukemia in interleukin 15 transgenic mice follows early expansions in natural killer and memory phenotype CD8+ T cells. J Exp Med. 2001;193:219–31. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.2.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Stoklasek TA, Colpitts SL, Smilowitz HM, Lefrancois L. MHC class I and TCR avidity control the CD8 T cell response to IL-15/IL-15Ralpha complex. J Immunol. 2010;185:6857–65. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Tan JT, Dudl E, LeRoy E, Murray R, Sprent J, Weinberg KI, et al. IL-7 is critical for homeostatic proliferation and survival of naive T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:8732–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.161126098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Tan JT, Ernst B, Kieper WC, LeRoy E, Sprent J, Surh CD. Interleukin (IL)-15 and IL-7 jointly regulate homeostatic proliferation of memory phenotype CD8+ cells but are not required for memory phenotype CD4+ cells. J Exp Med. 2002;195:1523–32. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Schluns KS, Kieper WC, Jameson SC, Lefrancois L. Interleukin-7 mediates the homeostasis of naive and memory CD8 T cells in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:426–32. doi: 10.1038/80868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Sandau MM, Winstead CJ, Jameson SC. IL-15 is required for sustained lymphopenia-driven proliferation and accumulation of CD8 T cells. J Immunol. 2007;179:120–5. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.1.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]