Abstract

Type 2 diabetes (T2D) has become a leading health problem throughout the world. It is caused by both environmental and genetic factors and interactions between them. However, until very recently, the T2D susceptibility genes have been poorly understood. During the past 5 years, with the advent of genome-wide association studies (GWAS), a total of 58 T2D susceptibility loci have been associated with T2D risk at a genome-wide significance level (P <5×10−8) and evidence shows that most of these genetic variants influence pancreatic β-cell function. Most novel T2D susceptibility loci were identified through GWAS in European populations and later confirmed in other ethnic groups. Although the recent discovery of novel T2D susceptibility loci has contributed substantially to our understanding of the pathophysiology of the disease, clinical utility of these loci in disease prediction and prognosis is limited. More studies using multiethnic meta-analysis, gene-environment interaction analysis, sequencing analysis, epigenetic analysis, and functional experiments are needed to identify new susceptibility T2D loci and causal variants and to establish biological mechanisms.

Keywords: Europeans, Genetics, Genome-wide association studies, Type 2 diabetes

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes (T2D) has become a leading health problem throughout the world, not only in Western countries, but also in developing countries. According to the International Diabetes Federation, the total number of people with diabetes is projected to rise from current estimates of 366 million to 552 million by the year 2030, with two-thirds of all diabetes cases occurring in low- to middle-income countries.1 In addition to lifestyle factors, there is compelling evidence that T2D has a strong genetic component. The concordance of T2D in monozygotic twins (~70%) is much higher compared to dizygotic twins (20–30%).2 A family history confers first-degree relatives a 3-fold increases risk of developing T2D.3 It has also been suggested that ethnic differences in the prevalence of T2D could be ascribed to genetic differences.4 Classic genetic research conducted with twins and with biological and adoptive and families, consistently supports genetic links to T2D. However, until very recently, T2D susceptibility genes have been poorly understood. With the recent advent of genome-wide association studies (GWAS), a number of T2D susceptibility loci have been identified during the past 5 years. The purpose of the present review is to summarize the research on recently established T2D susceptibility genes in European populations. The review will also briefly discuss the potential mechanisms, risk prediction, and gene-environment interactions underlying T2D.

Detection and validation of T2D susceptibility loci

With rapid improvements in high-throughput SNP genotyping technology and the development of the HapMap project, the identification of T2D susceptibility genes has changed dramatically. Since the identification of PPARG and KCNJ11 through candidate gene studies and TCF7L2 through large-scale association analysis, the emergence of GWA studies has dramatically increased the number of validated T2D susceptibility genes. To date, a total of 58 loci have been established to be associated with T2D at a genome-wide significance level (P <5×10−8). Among them, 39 loci was identified in European populations (Table 1), and the other 19 loci was identified in Asian populations (Please see the complementary review article by Jia et al. for details regarding genetics of T2D in Asian populations).

Table 1.

Type 2 diabetes susceptibility loci identified in European populations

| Locus | SNP | Chr | Allele (+/−) | RAF* | OR | Probable mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Candidate and large-scale association | ||||||

| 2000 | ||||||

| PPARG6 | rs1801282 | 3 | C/G | 092 | 1.147–9 | Insulin action |

| 2003 | ||||||

| KCNJ1111 | rs5219 | 11 | T/C | 0.50 | 1.147–9 | β-cell function |

| 2006 | ||||||

| TCF7L218 | rs7903146 | 10 | T/C | 0.25 | 1.377–9 | β-cell function |

| 2007 | ||||||

| WFS113 | rs10010131 | 4 | G/A | 0.60 | 1.11 | β-cell function |

| HNF1B (TCF2)17 | rs4430796 | 17 | A/G | 0.47 | 1.10 | unknown |

| 2011 | ||||||

| BCL221 | rs12454712 | 18 | T/C | 0.64 | 1.09 | Unknown |

| GATAD2A21 | rs3794991 | 19 | T/C | 0.08 | 1.12 | Unknown |

| GWAS | ||||||

| 2007 | ||||||

| IGF2BP27–9 | rs4402960 | 3 | T/G | 0.29 | 1.14 | β-cell function |

| CDKAL17–9, 23, 25 | rs10946398 | 6 | C/A | 0.31 | 1.12 | β-cell function |

| SLC30A824 | rs13266634 | 8 | C/T | 0.75 | 1.127–9 | β-cell function |

| CDKN2A/B7–9 | rs10811661 | 9 | T/C | 0.79 | 1.20 | β-cell function |

| HHEX/IDE24 | rs1111875 | 10 | C/T | 0.56 | 1.137–9 | β-cell function |

| FTO8, 9, 23 | rs8050136 | 16 | A/C | 0.45 | 1.17 | Obesity |

| 2008 | ||||||

| NOTCH232 | rs10923931 | 1 | T/G | 0.11 | 1.13 | Unknown |

| THADA32 | rs7578597 | 2 | T/C | 0.92 | 1.15 | β-cell function |

| ADAMTS932 | rs4607103 | 3 | C/T | 0.81 | 1.09 | Insulin action |

| JAZF132 | rs864745 | 7 | T/C | 0.52 | 1.10 | β-cell function |

| CDC123/CAMK1D32 | rs1277979032 | 10 | G/A | 0.23 | 1.11 | β-cell function |

| TSPAN8/LGR532 | rs7961581 | 12 | C/T | 0.23 | 1.09 | β-cell function |

| KCNQ144 | rs231362 | 11 | G/A | 0.52 | 1.08 | β-cell function |

| 2009 | ||||||

| IRS135 | rs2943641 | 2 | C/T | 0.61 | 1.19 | Insulin action |

| MTNR1B36–38, 42 | rs10830963 | 11 | G/C | 0.30 | 1.09 | β-cell function |

| 2010 | ||||||

| PROX142 | rs340874 | 1 | C/T | 0.50 | 1.07 | β-cell function |

| BCL11A44 | rs243021 | 2 | A/G | 0.46 | 1.08 | Unknown |

| GCKR42 | rs780094 | 2 | C/T | 0.62 | 1.06 | Insulin action |

| RBMS143 | rs7593730 | 2 | C/T | 0.83 | 1.11 | Insulin action |

| ADCY542 | rs11708067 | 3 | A/G | 0.78 | 1.12 | Unknown |

| ZBED344 | rs4457053 | 5 | G/A | 0.26 | 1.08 | Unknown |

| GCK42 | rs4607517 | 7 | A/G | 0.20 | 1.07 | β-cell function |

| DGKB/TMEM19542 | rs2191349 | 7 | T/G | 0.47 | 1.06 | β-cell function |

| KLF1444 | rs972283 | 7 | G/A | 0.55 | 1.07 | Unknown |

| TP53INP144 | rs896854 | 8 | T/C | 0.48 | 1.06 | Unknown |

| TLE4 (CHCHD9)44 | rs13292136 | 9 | C/T | 0.93 | 1.11 | Unknown |

| CENTD244 | rs1552224 | 11 | A/C | 0.88 | 1.14 | β-cell function |

| HMGA244 | rs1531343 | 12 | C/G | 0.10 | 1.11 | Unknown |

| HNF1A44 | rs7957197 | 12 | T/A | 0.85 | 1.07 | Unknown |

| PRC144 | rs8042680 | 15 | A/C | 0.22 | 1.07 | Unknown |

| ZFAND644 | rs11634397 | 15 | G/A | 0.56 | 1.06 | Unknown |

| DUSP944 | rs5945326 | X | G/A | 0.12 | 1.27 | Unknown |

Data were derived from HapMap EU or original studies.

SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; Chr, chromosome; +/−, risk/reference allele; RAF, risk allele frequency; OR, odds ratio.

Candidate gene studies

During the past 2 decades, only four T2D susceptibility loci were identified through the candidate gene approach. Though the loci were ultimately validated, numerous candidate genetic association analyses for T2D were carried out, but failed to be replicated. The Pro12Ala polymorphism (rs1801282) in PPARG and E23K (rs5219) polymorphism in KCNJ11 were the first robustly replicated signals associated with T2D. PPARG encodes the nuclear receptor PPAR-γ which is predominantly expressed in adipose tissue where it regulates the transcription of genes involved in adipogenesis. It is also a molecular target for thiazolidinedione compounds, a class of insulin-sensitizing drugs used to treat T2D. A non-synonymous SNP changing a proline in position 12 protein to alanine, Pro12Ala, was shown to be associated with increased insulin sensitivity and protection against T2D.5 A meta-analysis6 that strongly supported the association between the Pro12Ala variant and T2D was is also confirmed by recent GWAS.7–9 KCNJ11 encodes KIR6.2, a subunit with receptor 1 (SUR1) (encoded by ABCC8), and forms an ATP-sensitive potassium channel. The ATP-sensitive potassium channel regulates glucose-dependent insulin secretion in pancreatic beta-cells and it is also a molecular target for a class of diabetes drug, the sulfonylureas. A Glu23Lys polymorphism (E23K) gene has been associated with T2D in candidate gene studies10, 11 and was also confirmed in GWAS.7–9

More recently, the associations between genetic variants in WFS1 and HNF1B were identified from in-depth studies of candidate genes. WFS1 encodes wolframin, a membrane glycoprotein that maintains calcium homeostasis of the endoplasmic reticulum. Mutations in this gene may cause Wolfram syndrome which is characterized by diabetes insipidus, juvenile-onset non-autoimmune diabetes mellitus, optic atrophy, and deafness.12 In a study of 1,536 SNPs in 84 candidate genes involved in pancreatic beta cell function and survival, only WFS1 was associated with T2D.13 The association between the lead SNP rs10010131 and T2D was confirmed in a large meta-analysis.14 HNF1B, also known as TCF72, encodes hepatocyte nuclear factor 1 homeobox B (transcription factor 2), a liver-specific factor of the homeobox-containing basic helix-turn-helix family. Mutations in the HNF1B gene have been identified as the cause of maturity onset diabetes of the young type 5 (MODY5).15 Association between HNF1B genetic variants and T2D was first reported in a candidate genetic association study tested for known MODY genes.16 A GWAS initially designed for prostate cancer confirmed HNF1B as a T2D susceptibility gene.17

Large-scale association analysis

TCF7L2 is the first T2D susceptibility gene identified by large-scale association analysis,18 a ‘hypothesis-free’ association approach. The strong association between common variants in TCF7L and risk of T2D was highly confirmed in numerous replication studies and GWAS,7–9 with a per-allele odds ratio of ~1.4. TCF7L2 encodes a transcription factor that is a crucial component of the Wnt signaling pathway and that had not been considered as a candidate for type 2 diabetes. Current evidence indicates that TCF7L2 may confer type 2 diabetes risk through impaired beta-cell function and insulin secretion, incretin effects, and dysregulation of proglucagon gene expression.19, 20

Very recently, a large-scale meta-analysis of 39 studies by using a custom ~50,000 SNP genotyping array with ~2000 candidate genes identified two additional type 2 diabetes loci at genome-wide significance, GATAD2A and BCL2.21 GATAD2A encodes the GATA zinc finger domain containing 2A, a transcriptional repressor that interacts with the methyl-CpG-binding domain proteins MBD2 and MBD3. Methyl-CpG-binding domain proteins are involved in functional responses of methylated DNA. The lead SNP rs3794991 in GATAD2A is in strong LD (r2 >0.90 in HapMap CEU) with another SNP rs16996148, previously identified to be associated with low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and triglycerides levels in GWAS. 22 BCL2 encodes an integral outer mitochondrial membrane protein that plays an anti-apoptotic role but has not previously been implicated in T2D.

Genome-wide association studies in European populations

During the past 5 years, GWAS have made the most important contributions to identifying novel T2D susceptibility loci. In 2007, the first wave of T2D GWAS carried out in European populations identified 6 novel susceptibility loci: SLC30A8, HHEX/IDE, CDKAL1, CDKN2A/B, IGF2BP2, and FTO.7–9, 23–25 Subsequent studies have shown that diabetes-risk alleles in these 5 loci were associated with reduced insulin secretion, 26–29 while FTO, the first and strongest obesity gene identified so far,30, 31 may confer T2D risk through its primary effect on adiposity.8, 9, 30, 31

In 2008, a meta-analysis of three GWAS (Diabetes, Genetics, Replication and Meta-analysis, DIAGRAM Consortium) identified 6 additional T2D susceptibility loci: NOTCH2, THADA, ADAMTS9, JAZF1, CDC123/CAMK1D, and TSPAN8/LGR5.32 Genetic variants in JAZF1, CDC123/CAMK1D, TSPAN8/LGR5, THADA, and ADAMTS9 have been shown to be associated with impaired glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in subsequent studies.33, 34

In 2009, only one novel loci, IRS1, was identified by GWAS for T2D,35 but three groups concurrently reported another new T2D loci, MTNR1B, in follow-up analysis of GWAS for fasting glucose.36–38 IRS1 encodes insulin receptor substrate 1 that is phosphorylated by insulin receptor tyrosine kinase and is essential to insulin signaling pathway. The risk allele of the rs2943641 in IRS1 was also found to be associated with insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia in human populations, and was associated with reduced basal levels of IRS1 protein and decreased phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase activity in skeletal muscles.35 MTNR1B encodes melatonin receptor 1B, one of two known human melatonin receptors. Melatonin is a neurohormone and was reported to influence insulin secretion and glucose levels in previous studies.39–41

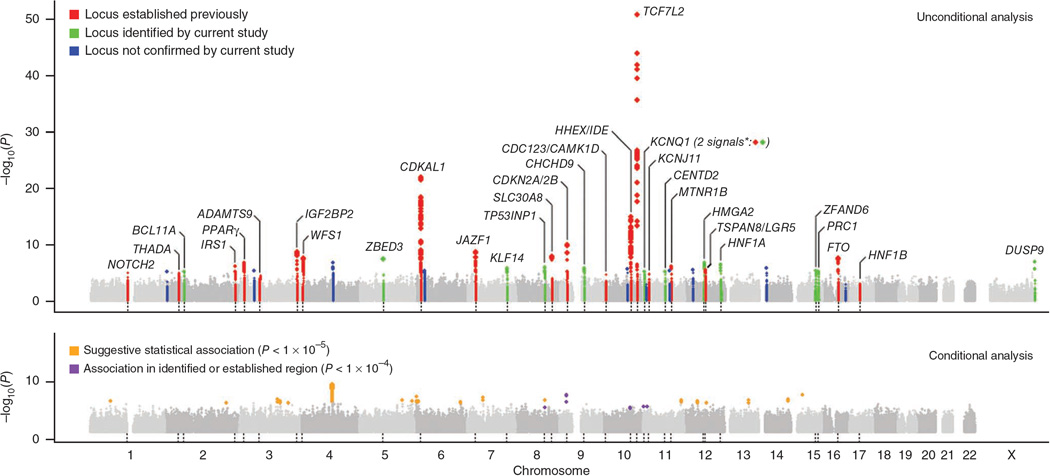

The most recent efforts in identifying T2D susceptibility loci have been made by collaborative meta-analyses of individual GWAS data. In early 2010, by combining the data from 21 GWAS, the Meta-analysis of Glucose and Insulin-related traits Consortium (MAGIC) identified 18 loci associated with fasting glucose and/or fasting insulin, and five of these loci were demonstrated as T2D susceptibility loci: ADCY5, PROX1, GCK, GCKR, and DGKB-TMEM195.42 A GWAS conducted in the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) and Health Professional Follow-up Study (HPFS) in combination with validation data from 11 independent GWAS, identified a new T2D susceptibility locus, RBMS1, on chromosome 2q24.43 Genetic variants in this region were nominally associated with fasting glucose and HOMA-IR in the MAGIC consortium. The updated meta-analysis conducted in the DIAGRAM consortium increased the discovery sample size which substantially expanded the number of T2D susceptibility loci (Figure 1),44 and 12 new loci were identified: BCL11A, ZBED3, KLF14, TP53INP1, TLE4, CENTD2, HMGA2, HNF1A, PRC1, ZFAND6, DUSP9, and KCNQ1 (a second independent signal in this locus which was first identified in East Asian GWAS45, 46). Of these recently identified loci, few could have been considered strong biological candidates prior to these studies. GCK encodes glucokinase which is the key glucose phosphorylation enzyme responsible for the first rate-limiting step in the glycolysis pathway and which regulates glucose-stimulated insulin secretion from pancreatic beta cells and glucose metabolism in the liver; and GCKR encodes glucokinase regulator. Both genes have previously been considered as candidates, but the associations with T2D were not strong in earlier studies.7, 47–49 HNF1A encoding hepatocyte nuclear factor 1, together with HNF2B and HNF4A, have been known as MODY genes.15 DUSP9 is the first reported signal at the X-chromosome, and it encodes dual specificity phosphatase 9, a mitogen-activated protein kinase that has a potential role in the regulation of insulin action in mice.50

Figure 1. Genome-wide Manhattan plots for the DIAGRAM+ stage 1 meta-analysis.

Data are based on a meta-analysis of eight T2D GWAS (8,130 T2D cases and 38,987 controls) in European populations, adapted from Voight et al.44

Biological mechanisms of T2D susceptibility loci

T2D is characterized by insulin resistance and impaired β-cell function. To date, identified T2D susceptibility loci appear to influence β-cell function rather than insulin resistance (Table 1). Numerous studies have suggested that genetic variants in or near KCNJ11, TCF7L2, WFS1, IGF2BP2, CDKAL1, SLC30A8, CDKN2A/B, HHEX/IDE, THADA, JAZF1, CDC123/CAMK1D, TSPAN8/LGR5, MTNR1B, KCNQ1, PROX1, GCK, DGKB/TMEM195, and CENTD2 may confer T2D risk most likely through impaired β-cell function,25, 37, 44, 51–60 although precise mechanisms are largely unclear. In the short list of insulin resistance-related loci, PPARG and IRS1 have been well-recognized given their known biological function in insulin action and signaling. ADAMTS9 and GCKR may also have an effect on insulin action,61–63 although the results from other studies are somewhat conflicting.57, 64, 65 In addition, RMBS1 was also reported to be associated with insulin resistance.43 FTO appears to confer T2D risk through its primary effect on adiposity,8, 9, 30, 31 however, two recent meta-analyses have shown that the association with T2D could not be fully explained by its effect on BMI.66, 67

Recent genetic discoveries have implicated novel potential pathways in the development of T2D. The strongest association signal in TCF7L2 highlights the important role of the Wnt-signaling pathway in β-cell function and insulin secretion.20 The discovery of SLC30A8 which encodes zinc transporter 8 suggests the importance of the role of insulin packaging and storage through β-cell zinc transporter68 in the development of T2D. Several newly identified loci, such as CDKAL1, CDKN2A/B, and CDC123, have been involved in cell cycle regulation, and thus might be implicated in the pancreatic beta-cell regenerative process. Identification of MTNR1B as a T2D locus indicates a genetic link between circadian rhythm and glucose metabolism. In addition, genetic variants in ADCY5, encoding adenylate cyclase type 5, have been also associated with low birth weight,69, 70 providing new information on the observed relationship between low birth weight and increased risk of T2D in epidemiological studies.71

Genetic prediction in T2D

Genetic information is expected to have important clinical utility in the prediction of developing T2D. However, with the exception of risk allele TCF7L2 which has a per-allele OR of ~1.4, most risk alleles in the newly identified T2D loci may only increase risk of T2D by 10–20%. Because of the modest effect sizes of each individual genetic variant, creating a genetic risk score by summing the number of risk alleles has been widely used in recent studies.72–81 It has been suggested that a genetic risk score that combines information from multiple genetic variants might be useful for identifying individuals with a particularly high risk for T2D.72–81 For example, a nested case-control study from the NHS and HPFS created a genetic risk score on the basis of 10 genetic variants and subgroups with extreme genetic risk profiles (4% of subjects with 0–7 risk alleles vs 5% of subjects with ≥ 15 risk alleles) showed a 4-fold difference in the risk of T2D.77 In a population-based prospective study, 19 T2D genetic variants were used and individuals carrying 21 risk alleles or more (14% of the population) had about a 2-fold higher T2D risk compared with the reference group of 0–12 alleles (2 % of the population).76

When using the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves (AUCs) to evaluate discriminative accuracy of T2D by genetic variants (the AUC can range from 0.5 [total lack of discrimination] to 1.0 [perfect discrimination] and a test with AUC of greater than 0.75 is considered to be clinically useful), the results are less compelling. In most previous combined analyses of 10 to 20 T2D risk SNPs, the AUC for the genetic risk score alone was around 0.60,72, 75, 76, 78–80 while the AUC for conventional risk factors (such as age, gender, BMI, lifestyle, and family history of diabetes, etc.) was greater than 0.75.72, 73, 75, 77–80 The addition of the genetic risk score to the model of conventional risk factors slightly improved the discrimination of T2D.72, 73, 75–79 Thus, the prospects for individual prediction of T2D risk seem limited in the current stage. However, it should be noted that identified genetic loci account for only ~10% of T2D susceptibility in European-descent populations.44

Gene-environment interactions

It is widely accepted that T2D is a product of the interplay between genetic and environmental factors. Although the genetic background of a certain population is relatively constant for many generations, it seems that the effects of genetic factors are amplified in the presence of certain environmental triggers. There have been dramatic changes in lifestyle and dietary habits over the past several decades, from a “traditional” style to a “Westernized” or “obesogenic” style, which is categorized by increased access to highly-palatable, calorie-dense food, and a sedentary lifestyle. In the HPFS, Qi et al found a significant interaction between a Western dietary pattern, derived from a principle component analysis of 40 food groups, and a genetic risk score of T2D susceptibility, based on 10 established SNP (P = 0.02).82 The multivariable ORs of T2D across increasing quartiles of the Western dietary pattern were 1.00, 1.23 (95% CI: 0.88, 1.73), 1.49 (1.06, 2.09), and 2.06 (1.48, 2.88) among men with a higher genetic risk score. Among those with a lower genetic risk score, the Western dietary pattern was not associated with diabetes risk. On the other hand, the genetic association with diabetes risk was more pronounced in individuals with a higher Western dietary pattern compared to those with a lower Western dietary pattern. This study illustrates the impact of gene-environment interactions on diabetes risk. In addition, several individual T2D loci, such as TCF7L2, PPARG, SLC30A8, and GCKR, have also been found to interact with dietary and lifestyle factors on T2D risk and related traits.83–86

There are emerging studies reporting interactions between T2D loci and prenatal nutrition. In an earlier study, de Rooij et al. reported significant interactions between the PPARG Pro12Ala polymorphism and early malnutrition during mid-gestation on risk of impaired glucose tolerance and T2D.87 Recently, Pulizzi et al. tested interactions between variants of nine T2D loci and birth weight, and they found that risk variants at the HHEX, CDKN2A/2B, and JAZF1 loci significantly interacted with birth weight to predict future T2D.88 In addition, in the Dutch Famine Birth Cohort, the IGF2BP2 polymorphism showed an interaction with prenatal exposure to famine on glucose level.89 These interaction analyses are related to the thrifty phenotype hypothesis90 which states that malnutrition during fetal development leads to poor fetal and infant growth and predisposes individuals to T2D and other chronic metabolic disease. These data suggest that an individual’s genetic background may modulate the response to prenatal nutrition and subsequently affect T2D risk caused by a hyper-caloric environment in later life.

With the identification of T2D genetic loci, some progress has also been made in characterizing gene-environment interactions that underlie T2D, however, many inconsistencies remain and significant findings require further replication and validation.91 Furthermore, studies focused on gene-environment interactions in relation to T2D are sparse in Asians and other ethnic groups.

Conclusions

Over a relatively short time, significant progress in understanding the genetics of T2D has been made by the waves of GWAS. To date, a total of 58 T2D genetic loci have been identified and most genetic variants seem to influence pancreatic β-cell function. Although the actual causal variants and biological function of most T2D genetic loci are largely unknown, many new loci provide new insights into the pathophysiology of T2D. In addition, the discovery of novel T2D susceptibility loci helps us understand the ethnic differences in diabetes risk and gene-environment interactions underlying T2D and provides new information in the clinical utility of genetic factors. More studies, such as fine-mapping, whole exome and genome sequencing, multiethnic meta-analysis, gene-gene and gene-environment interactions, epigenetics (DNA methylation analysis), and functional studies, are needed to identify new T2D loci, causal variants, and the underlying mechanisms and will help us better understand the differences in diabetes risk across ethnic groups.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants HL71981 and DK58845 from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

References

- 1.International Diabetes Federation. International Diabetes Federation's 5th edition of the Diabetes Atlas. [Accessed on 1 May 2012]; Available from http://www.idf.org/

- 2.Elbein SC. The genetics of human noninsulin-dependent (type 2) diabetes mellitus. J Nutr. 1997;127:1891S–1896S. doi: 10.1093/jn/127.9.1891S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gloyn AL, McCarthy MI. The genetics of type 2 diabetes. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;15:293–308. doi: 10.1053/beem.2001.0147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Serjeantson SW, Owerbach D, Zimmet P, Nerup J, Thoma K. Genetics of diabetes in Nauru: effects of foreign admixture, HLA antigens and the insulin-gene-linked polymorphism. Diabetologia. 1983;25:13–17. doi: 10.1007/BF00251889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deeb SS, Fajas L, Nemoto M, et al. A Pro12Ala substitution in PPAR[gamma]2 associated with decreased receptor activity, lower body mass index and improved insulin sensitivity. Nat Genet. 1998;20:284–287. doi: 10.1038/3099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Altshuler D, Hirschhorn JN, Klannemark M, et al. The common PPAR[gamma] Pro12Ala polymorphism is associated with decreased risk of type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2000;26:76–80. doi: 10.1038/79216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saxena R, Voight BF, Lyssenko V, et al. Genome-wide association analysis identifies loci for type 2 diabetes and triglyceride levels. Science. 2007;316:1331–1336. doi: 10.1126/science.1142358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scott LJ, Mohlke KL, Bonnycastle LL, et al. A Genome-Wide Association Study of Type 2 Diabetes in Finns Detects Multiple Susceptibility Variants. Science. 2007;316:1341–1345. doi: 10.1126/science.1142382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zeggini E, Weedon MN, Lindgren CM, et al. Replication of genome-wide association signals in UK samples reveals risk loci for type 2 diabetes. Science. 2007;316:1336–1341. doi: 10.1126/science.1142364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hani EH, Boutin P, Durand E, et al. Missense mutations in the pancreatic islet beta cell inwardly rectifying K+ channel gene (KIR6.2/BIR): a meta-analysis suggests a role in the polygenic basis of Type II diabetes mellitus in Caucasians. Diabetologia. 1998;41:1511–1515. doi: 10.1007/s001250051098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gloyn AL, Weedon MN, Owen KR, et al. Large-Scale Association Studies of Variants in Genes Encoding the Pancreatic Î2-Cell KATP Channel Subunits Kir6.2 (KCNJ11) and SUR1 (ABCC8) Confirm That the KCNJ11 E23K Variant Is Associated With Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes. 2003;52:568–572. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.2.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inoue H, Tanizawa Y, Wasson J, et al. A gene encoding a transmembrane protein is mutated in patients with diabetes mellitus and optic atrophy (Wolfram syndrome) Nat Genet. 1998;20:143–148. doi: 10.1038/2441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sandhu MS, Weedon MN, Fawcett KA, et al. Common variants in WFS1 confer risk of type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2007;39:951–953. doi: 10.1038/ng2067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Franks P, Rolandsson O, Debenham S, et al. Replication of the association between variants in <i>WFS1</i> and risk of type 2 diabetes in European populations. Diabetologia. 2008;51:458–463. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0887-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fajans SS, Bell GI, Polonsky KS. Molecular Mechanisms and Clinical Pathophysiology of Maturity-Onset Diabetes of the Young. New England Journal of Medicine. 2001;345:971–980. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra002168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Winckler W, Weedon MN, Graham RR, et al. Evaluation of Common Variants in the Six Known Maturity-Onset Diabetes of the Young (MODY) Genes for Association With Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes. 2007;56:685–693. doi: 10.2337/db06-0202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gudmundsson J, Sulem P, Steinthorsdottir V, et al. Two variants on chromosome 17 confer prostate cancer risk, and the one in TCF2 protects against type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2007;39:977–983. doi: 10.1038/ng2062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grant SFA, Thorleifsson G, Reynisdottir I, et al. Variant of transcription factor 7-like 2 (TCF7L2) gene confers risk of type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2006;38:320–323. doi: 10.1038/ng1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lyssenko V, Lupi R, Marchetti P, et al. Mechanisms by which common variants in the TCF7L2 gene increase risk of type 2 diabetes. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2007;117:2155–2163. doi: 10.1172/JCI30706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schäfer S, Tschritter O, Machicao F, et al. Impaired glucagon-like peptide-1-induced insulin secretion in carriers of transcription factor 7-like 2 (<i>TCF7L2</i>) gene polymorphisms. Diabetologia. 2007;50:2443–2450. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0753-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saxena R, Elbers CC, Guo Y, et al. Large-Scale Gene-Centric Meta-Analysis across 39 studies Identifies Type 2 Diabetes Loci. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;***9;90:410–425. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kathiresan S, Willer CJ, Peloso GM, et al. Common variants at 30 loci contribute to polygenic dyslipidemia. Nat Genet. 2009;41:56–65. doi: 10.1038/ng.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Genome-wide association study of 14,000 cases of seven common diseases and 3,000 shared controls. Nature. 2007;447:661–678. doi: 10.1038/nature05911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sladek R, Rocheleau G, Rung J, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies novel risk loci for type 2 diabetes. Nature. 2007;445:881–885. doi: 10.1038/nature05616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steinthorsdottir V, Thorleifsson G, Reynisdottir I, et al. A variant in CDKAL1 influences insulin response and risk of type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2007;39:770–775. doi: 10.1038/ng2043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Staiger H, Machicao F, Stefan N, et al. Polymorphisms within Novel Risk Loci for Type 2 Diabetes Determine Î2-Cell Function. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e832. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boesgaard T, Žilinskaitė J, Vänttinen M, et al. The common SLC30A8; Arg325Trp variant is associated with reduced first-phase insulin release in 846 non-diabetic offspring of type 2 diabetes patients—the EUGENE2 study. Diabetologia. 2008;51:816–820. doi: 10.1007/s00125-008-0955-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grarup N, Rose CS, Andersson EA, et al. Studies of Association of Variants Near the HHEX, CDKN2A/B, and IGF2BP2 Genes With Type 2 Diabetes and Impaired Insulin Release in 10,705 Danish Subjects. Diabetes. 2007;56:3105–3111. doi: 10.2337/db07-0856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pascoe L, Tura A, Patel SK, et al. Common Variants of the Novel Type 2 Diabetes Genes CDKAL1 and HHEX/IDE Are Associated With Decreased Pancreatic Î2-Cell Function. Diabetes. 2007;56:3101–3104. doi: 10.2337/db07-0634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dina C, Meyre D, Gallina S, et al. Variation in FTO contributes to childhood obesity and severe adult obesity. Nat Genet. 2007;39:724–726. doi: 10.1038/ng2048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frayling TM, Timpson NJ, Weedon MN, et al. A Common Variant in the FTO Gene Is Associated with Body Mass Index and Predisposes to Childhood and Adult Obesity. Science. 2007;316:889–894. doi: 10.1126/science.1141634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zeggini E, Scott LJ, Saxena R, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association data and large-scale replication identifies additional susceptibility loci for type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2008;40:638–645. doi: 10.1038/ng.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simonis-Bik AM, Nijpels G, van Haeften TW, et al. Gene Variants in the Novel Type 2 Diabetes Loci CDC123/CAMK1D, THADA, ADAMTS9, BCL11A, and MTNR1B Affect Different Aspects of Pancreatic Î2-Cell Function. Diabetes. 59:293–301. doi: 10.2337/db09-1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grarup N, Andersen G, Krarup NT, et al. Association Testing of Novel Type 2 Diabetes Risk Alleles in the JAZF1, CDC123/CAMK1D, TSPAN8, THADA, ADAMTS9, and NOTCH2 Loci With Insulin Release, Insulin Sensitivity, and Obesity in a Population-Based Sample of 4,516 Glucose-Tolerant Middle-Aged Danes. Diabetes. 2008;57:2534–2540. doi: 10.2337/db08-0436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rung J, Cauchi S, Albrechtsen A, et al. Genetic variant near IRS1 is associated with type 2 diabetes, insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1110–1115. doi: 10.1038/ng.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bouatia-Naji N, Bonnefond A, Cavalcanti-Proenca C, et al. A variant near MTNR1B is associated with increased fasting plasma glucose levels and type 2 diabetes risk. Nat Genet. 2009;41:89–94. doi: 10.1038/ng.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lyssenko V, Nagorny CLF, Erdos MR, et al. Common variant in MTNR1B associated with increased risk of type 2 diabetes and impaired early insulin secretion. Nat Genet. 2009;41:82–88. doi: 10.1038/ng.288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Prokopenko I, Langenberg C, Florez JC, et al. Variants in MTNR1B influence fasting glucose levels. Nat Genet. 2009;41:77–81. doi: 10.1038/ng.290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boden G, Ruiz J, Urbain JL, Chen X. Evidence for a circadian rhythm of insulin secretion. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:E246–E252. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1996.271.2.E246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Van Cauter E. Putative roles of melatonin in glucose regulation. Therapie. 1998;53:467–472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peschke E, Frese T, Chankiewitz E, et al. Diabetic Goto Kakizaki rats as well as type 2 diabetic patients show a decreased diurnal serum melatonin level and an increased pancreatic melatonin-receptor status. Journal of Pineal Research. 2006;40:135–143. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2005.00287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dupuis J, Langenberg C, Prokopenko I, et al. New genetic loci implicated in fasting glucose homeostasis and their impact on type 2 diabetes risk. Nat Genet. 42:105–116. doi: 10.1038/ng.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Qi L, Cornelis MC, Kraft P, et al. Genetic variants at 2q24 are associated with susceptibility to type 2 diabetes. Human Molecular Genetics. 19:2706–2715. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Voight BF, Scott LJ, Steinthorsdottir V, et al. Twelve type 2 diabetes susceptibility loci identified through large-scale association analysis. Nat Genet. 2010;42:579–589. doi: 10.1038/ng.609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Unoki H, Takahashi A, Kawaguchi T, et al. SNPs in KCNQ1 are associated with susceptibility to type 2 diabetes in East Asian and European populations. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1098–1102. doi: 10.1038/ng.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yasuda K, Miyake K, Horikawa Y, et al. Variants in KCNQ1 are associated with susceptibility to type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1092–1097. doi: 10.1038/ng.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vaxillaire M, Veslot J, Dina C, et al. Impact of common type 2 diabetes risk polymorphisms in the DESIR prospective study. Diabetes. 2008;57:244–254. doi: 10.2337/db07-0615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sparsø T, Andersen G, Nielsen T, et al. The GCKR rs780094 polymorphism is associated with elevated fasting serum triacylglycerol, reduced fasting and OGTT-related insulinaemia, and reduced risk of type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2008;51:70–75. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0865-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Qi Q, Wu Y, Li H, et al. Association of GCKR rs780094, alone or in combination with GCK rs1799884, with type 2 diabetes and related traits in a Han Chinese population. Diabetologia. 2009;52:834–843. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1290-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xu H, Dembski M, Yang Q, et al. Dual Specificity Mitogen-activated Protein (MAP) Kinase Phosphatase-4 Plays a Potential Role in Insulin Resistance. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278:30187–30192. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302010200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Boesgaard TW, Grarup N, Jorgensen T, Borch-Johnsen K, Hansen T, Pedersen O. Variants at DGKB/TMEM195, ADRA2A, GLIS3 and C2CD4B loci are associated with reduced glucose-stimulated beta cell function in middle-aged Danish people. Diabetologia. 53:1647–1655. doi: 10.1007/s00125-010-1753-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ingelsson E, Langenberg C, Hivert MF, et al. Detailed physiologic characterization reveals diverse mechanisms for novel genetic Loci regulating glucose and insulin metabolism in humans. Diabetes. 59:1266–1275. doi: 10.2337/db09-1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nielsen EM, Hansen L, Carstensen B, et al. The E23K variant of Kir6.2 associates with impaired post-OGTT serum insulin response and increased risk of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2003;52:573–577. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.2.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Grarup N, Rose CS, Andersson EA, et al. Studies of association of variants near the HHEX, CDKN2A/B, and IGF2BP2 genes with type 2 diabetes and impaired insulin release in 10,705 Danish subjects: validation and extension of genome-wide association studies. Diabetes. 2007;56:3105–3111. doi: 10.2337/db07-0856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pascoe L, Tura A, Patel SK, et al. Common variants of the novel type 2 diabetes genes CDKAL1 and HHEX/IDE are associated with decreased pancreatic beta-cell function. Diabetes. 2007;56:3101–3104. doi: 10.2337/db07-0634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Boesgaard TW, Zilinskaite J, Vanttinen M, et al. The common SLC30A8 Arg325Trp variant is associated with reduced first-phase insulin release in 846 non-diabetic offspring of type 2 diabetes patients--the EUGENE2 study. Diabetologia. 2008;51:816–820. doi: 10.1007/s00125-008-0955-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Grarup N, Andersen G, Krarup NT, et al. Association testing of novel type 2 diabetes risk alleles in the JAZF1, CDC123/CAMK1D, TSPAN8, THADA, ADAMTS9, and NOTCH2 loci with insulin release, insulin sensitivity, and obesity in a population-based sample of 4,516 glucose-tolerant middle-aged Danes. Diabetes. 2008;57:2534–2540. doi: 10.2337/db08-0436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sparso T, Andersen G, Albrechtsen A, et al. Impact of polymorphisms in WFS1 on prediabetic phenotypes in a population-based sample of middle-aged people with normal and abnormal glucose regulation. Diabetologia. 2008;51:1646–1652. doi: 10.1007/s00125-008-1064-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wu Y, Li H, Loos RJ, et al. Common variants in CDKAL1, CDKN2A/B, IGF2BP2, SLC30A8, and HHEX/IDE genes are associated with type 2 diabetes and impaired fasting glucose in a Chinese Han population. Diabetes. 2008;57:2834–2842. doi: 10.2337/db08-0047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Qi Q, Li H, Loos RJF, et al. Common variants in KCNQ1 are associated with type 2 diabetes and impaired fasting glucose in a Chinese Han population. Human Molecular Genetics. 2009;18:3508–15. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Orho-Melander M, Melander O, Guiducci C, et al. Common missense variant in the glucokinase regulatory protein gene is associated with increased plasma triglyceride and C-reactive protein but lower fasting glucose concentrations. Diabetes. 2008;57:3112–3121. doi: 10.2337/db08-0516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sparso T, Andersen G, Nielsen T, et al. The GCKR rs780094 polymorphism is associated with elevated fasting serum triacylglycerol, reduced fasting and OGTT-related insulinaemia, and reduced risk of type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2008;51:70–75. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0865-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Boesgaard TW, Gjesing AP, Grarup N, et al. Variant near ADAMTS9 known to associate with type 2 diabetes is related to insulin resistance in offspring of type 2 diabetes patients--EUGENE2 study. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7236. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schleinitz D, Tonjes A, Bottcher Y, et al. Lack of significant effects of the type 2 diabetes susceptibility loci JAZF1, CDC123/CAMK1D, NOTCH2, ADAMTS9, THADA, and TSPAN8/LGR5 on diabetes and quantitative metabolic traits. Horm Metab Res. 42:14–22. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1233480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Qi Q, Wu Y, Li H, et al. Association of GCKR rs780094, alone or in combination with GCK rs1799884, with type 2 diabetes and related traits in a Han Chinese population. Diabetologia. 2009;52:834–843. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1290-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hertel JK, Johansson S, Sonestedt E, et al. FTO, Type 2 Diabetes, and Weight Gain Throughout Adult Life. Diabetes. 60:1637–1644. doi: 10.2337/db10-1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Li H, Kilpeläinen T, Liu C, et al. Association of genetic variation in FTO with risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes with data from 96,551 East and South Asians. Diabetologia. 55:981–995. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2370-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chimienti F, Favier A, Seve M. ZnT-8, A Pancreatic Beta-Cell-Specific Zinc Transporter. BioMetals. 2005;18:313–317. doi: 10.1007/s10534-005-3687-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Andersson E, Pilgaard K, Pisinger C, et al. Type 2 diabetes risk alleles near ADCY5, CDKAL1; and HHEX-IDE are associated with reduced birthweight. Diabetologia. 53:1908–1916. doi: 10.1007/s00125-010-1790-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Freathy RM, Mook-Kanamori DO, Sovio U, et al. Variants in ADCY5 and near CCNL1 are associated with fetal growth and birth weight. Nat Genet. 42:430–435. doi: 10.1038/ng.567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Harder T, Rodekamp E, Schellong K, Dudenhausen JW, Plagemann A. Birth Weight and Subsequent Risk of Type 2 Diabetes: A Meta-Analysis. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2007;165:849–857. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwk071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lyssenko V, Jonsson A, Almgren P, et al. Clinical Risk Factors, DNA Variants, and the Development of Type 2 Diabetes. New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;359:2220–2232. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0801869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Meigs JB, Shrader P, Sullivan LM, et al. Genotype Score in Addition to Common Risk Factors for Prediction of Type 2 Diabetes. New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;359:2208–2219. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cauchi Sp, Meyre D, Durand E, et al. Post Genome-Wide Association Studies of Novel Genes Associated with Type 2 Diabetes Show Gene-Gene Interaction and High Predictive Value. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2031. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lango H, Palmer CNA, Morris AD, et al. Assessing the Combined Impact of 18 Common Genetic Variants of Modest Effect Sizes on Type 2 Diabetes Risk. Diabetes. 2008;57:3129–3135. doi: 10.2337/db08-0504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.van Hoek M, Dehghan A, Witteman JCM, et al. Predicting Type 2 Diabetes Based on Polymorphisms From Genome-Wide Association Studies. Diabetes. 2008;57:3122–3128. doi: 10.2337/db08-0425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cornelis MC, Qi L, Zhang C, et al. Joint Effects of Common Genetic Variants on the Risk for Type 2 Diabetes in U.S. Men and Women of European Ancestry. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2009;150:541–550. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-8-200904210-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sparsø T, Grarup N, Andreasen C, et al. Combined analysis of 19 common validated type 2 diabetes susceptibility gene variants shows moderate discriminative value and no evidence of gene–gene interaction. Diabetologia. 2009;52:1308–1314. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1362-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Qi Q, Li H, Wu Y, et al. Combined effects of 17 common genetic variants on type 2 diabetes risk in a Han Chinese population. Diabetologia. 2010;53:2163–2166. doi: 10.1007/s00125-010-1826-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Janipalli CS, Kumar MVK, Vinay DG, et al. Analysis of 32 common susceptibility genetic variants and their combined effect in predicting risk of Type 2 diabetes and related traits in Indians. Diabetic Medicine. 2012;29:121–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2011.03438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Xu M, Bi Y, Xu Y, et al. Combined Effects of 19 Common Variations on Type 2 Diabetes in Chinese: Results from Two Community-Based Studies. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e14022. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Qi L, Cornelis MC, Zhang C, van Dam RM, Hu FB. Genetic predisposition, Western dietary pattern, and the risk of type 2 diabetes in men. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2009;89:1453–1458. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.27249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cornelis MC, Qi L, Kraft P, Hu FB. TCF7L2, dietary carbohydrate, and risk of type 2 diabetes in US women. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2009;89:1256–1262. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.27058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kanoni S, Nettleton JA, Hivert M-F, et al. Total Zinc Intake May Modify the Glucose-Raising Effect of a Zinc Transporter (SLC30A8) Variant. Diabetes. 60:2407–2416. doi: 10.2337/db11-0176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nettleton JA, McKeown NM, Kanoni S, et al. Interactions of Dietary Whole-Grain Intake With Fasting Glucose– and Insulin-Related Genetic Loci in Individuals of European Descent. Diabetes Care. 33:2684–2691. doi: 10.2337/dc10-1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lamri A, Abi Khalil C, Jaziri R, et al. Dietary fat intake and polymorphisms at the PPARG locus modulate BMI and type 2 diabetes risk in the D.E.S.I.R. prospective study. Int J Obes. 36:218–224. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2011.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.de Rooij SR, Painter RC, Phillips DIW, et al. The Effects of the Pro12Ala Polymorphism of the Peroxisome Proliferator–Activated Receptor-Î22 Gene on Glucose/Insulin Metabolism Interact With Prenatal Exposure to Famine. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:1052–1057. doi: 10.2337/diacare.2951052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Pulizzi N, Lyssenko V, Jonsson A, et al. Interaction between prenatal growth and high-risk genotypes in the development of type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2009;52:825–829. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1291-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.van Hoek M, Langendonk JG, de Rooij SR, Sijbrands EJG, Roseboom TJ. Genetic Variant in the IGF2BP2 Gene May Interact With Fetal Malnutrition to Affect Glucose Metabolism. Diabetes. 2009;58:1440–1444. doi: 10.2337/db08-1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hales CN, Barker DJP. The thrifty phenotype hypothesis. British Medical Bulletin. 2001;60:5–20. doi: 10.1093/bmb/60.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Cornelis MC, Hu FB. Gene-Environment Interactions in the Development of Type 2 Diabetes: Recent Progress and Continuing Challenges. Annual Review of Nutrition 2012. 32:17.1–17.15. doi: 10.1146/annurev-nutr-071811-150648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]