Abstract

Background

The psychological reactions to catastrophic events are not known well in children.

Purpose

The present study was performed to quantify the core features of post-traumatic stress reactions in schoolchildren after the Kobe earthquake.

Methods

Children’s psychological reactions to the Kobe earthquake were examined in a total of 8,800 schoolchildren attending the third, fifth, or eighth grade in the disaster areas. The control subjects were 1,886 schoolchildren in the same grades in distant areas minimally affected by the earthquake. A self-report questionnaire was developed with reference to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV and the post-traumatic stress disorder reaction index and was used to score psychological reactions rating them from 1 to 4 depending on the frequency of the symptom. The survey was conducted four times, from 4 months to 2 years after the earthquake.

Results

Three factors were consistently extracted by factor analysis on the results of each study. Factor 1 was interpreted as relating to direct fear of the disaster and general anxiety, factor 2 as relating to depression and physical symptoms, and factor 3 as social responsibility such as feelings of sympathy for those who are suffering more severely and guilt for surviving. Young schoolchildren displayed particularly high scores on these factors. Furthermore, these factors were significantly associated with injuries of the children themselves, fatalities/injuries of family members, and the experience of being rescued or staying in shelters.

Conclusions

Psychological and comprehensive interventions should be directed at the most vulnerable populations of young children after future earthquakes.

Keywords: Kobe earthquake, Children, Post-traumatic stress disorder

Introduction

A devastating earthquake with a magnitude of 7.2 on the Richter scale [1] hit Kobe and nearby cities in Japan early morning of January 17, 1995. Nearly 1.6 million people lived in this heavily damaged area; 5,502 died immediately, and 41,527 were wounded. A total of 39,440 houses were damaged. At the time of maximum evacuation, there were 317,000 evacuees and 1,150 shelters [2].

After the Kobe (Great Hanshin-Awaji) earthquake, people experienced devastating Haiti (2010); Bhuj, India (2001); Bam, Iran (2003); and Wenchuan, China (2008). Much remains to be done to reduce earthquake hazards especially for those living along active plate boundaries.

Catastrophic events, in contrast to stressors of lesser magnitude, have been etiologically linked to a specific syndrome, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [3]. However, many of the studies on this syndrome have been of adults exposed to extremely life-threatening situations and there have been few empirical studies of children in such situations [4–6]. The current study was conducted to examine the magnitude, the nature, and the time–course of the psychological consequences for 8,800 schoolchildren who were greatly affected by the Kobe earthquake.

Methods

Subjects

The subjects of the survey were 8,800 schoolchildren in the third, fifth, or eighth grade at 32 elementary schools and 14 junior high schools in the disaster areas such as Kobe city and Nishinomiya city. The control subjects were 1,886 schoolchildren in the third, fifth, or eighth grade at six elementary schools and five junior high schools in distant areas that were minimally affected by the earthquake.

Questionnaire

The questionnaire was in a self-report format and consisted of 10 items about the disaster, 22 items about mental health condition, and 1 item in which participants were free to describe whatever they wished. With reference to the DSM-IV [3] and the PTSD reaction index [4–6], the items about mental health condition referred to physical symptoms (four items), anxiety symptoms (four items), depression symptoms (three items), flashback symptoms (two items), avoidance symptoms (two items), arousal symptoms (three items), regression symptoms (one item), survivor’s guilt (one item), and self-esteem (two items).

Survey

The survey was conducted by the respective classroom teachers. First, teachers explained the contents of the survey and how to complete the questionnaire in conformity with a manual that we had prepared for teachers. For children in the third grade, the teachers read out each question. In the first survey, members of the study group (including pediatric psychiatrists and psychologists) were present in case the students expressed psychological restlessness such as anxiety.

The first survey (hereafter referred to as the fourth month) was conducted during the period April 24 to May 16, 1995 with 8,800 schoolchildren in the disaster areas and 1,886 control schoolchildren. The second survey (hereafter referred to as the sixth month) was carried out during the period July 11 to 20, 1995 in the disaster areas only, and the third survey (hereafter referred to as the first year) was conducted during the period February 11 to March 22, 1996 in the disaster areas only. The fourth survey (hereafter referred to as the second year) was carried out during the period December 1 to 15, 1996 in both the disaster and control areas.

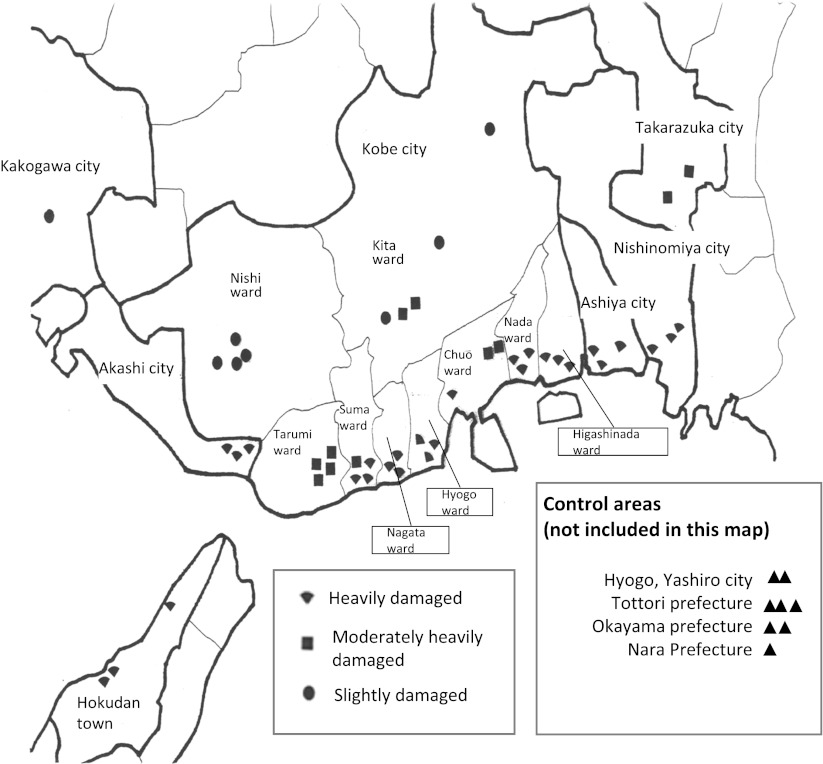

Classification of Areas by the Extent of the Disaster

Areas were classified into four categories based on the extent of the disaster (Fig. 1). Heavily damaged areas were defined as those where resident children gave less than 50% of affirmative answers to the questions "no house damage by the earthquake" and "no injuries to the family members due to the earthquake" (n = 4,293 children in the first survey). Moderately heavily damaged areas had 50–70% of affirmative answers to these questions (n = 1,645 children in the first survey), and slightly damaged areas had 71–90% of affirmative answers (n = 2,862 children in the first survey). Control areas had nearly 100% affirmative answers. These classifications paralleled the extent of the disaster on the Richter scale.

Fig. 1.

Location of the schools (62 in total) where surveys were conducted 3, 6, and 12 months after the Kobe earthquake

Factor Analysis

The answers to the survey were rated from 1 to 4 depending on the frequency of the symptom (1 = "none", 2 = "sometimes", 3 = "often", and 4 = "always"). Three factors were consistently elicited in the analysis of the results of the survey carried out at 4 months, 6 months, 1 year, and 2 years after the earthquake (Table 1).

Table 1.

Factor analysis

| Kobe earthquake mental state index for children (Kemsi-c) | 4 Months | 6 Months | 1 Year | 2 Years | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | communality h2 | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | communality h2 | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | communality h2 | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | communality h2 | |

| Do scenes of the earthquake come to mind all of sudden? or Are you afraid of another earthquake? | 0.67 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.54 | 0.67 | 0.21 | 0.19 | 0.53 | 0.67 | 0.19 | 0.15 | 0.52 | 0.65 | 0.16 | 0.12 | 0.47 |

| Are you scared when not in the company of family members and friends? | 0.63 | 0.26 | 0.09 | 0.48 | 0.62 | 0.25 | 0.10 | 0.47 | 0.62 | 0.28 | 0.10 | 0.47 | 0.58 | 0.29 | 0.10 | 0.43 |

| Are you afraid of another earthquake attack or other accidents? | 0.62 | 0.17 | 0.21 | 0.46 | 0.64 | 0.19 | 0.20 | 0.49 | 0.66 | 0.19 | 0.17 | 0.50 | 0.64 | 0.20 | 0.16 | 0.48 |

| Are you easily frightened by small noises? | 0.59 | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.41 | 0.58 | 0.23 | 0.16 | 0.42 | 0.60 | 0.24 | 0.14 | 0.44 | 0.57 | 0.22 | 0.13 | 0.28 |

| Do you hate to hear or speak about the earthquake? | 0.52 | 0.12 | 0.22 | 0.34 | 0.54 | 0.11 | 0.21 | 0.35 | 0.50 | 0.10 | 0.23 | 0.31 | 0.52 | 0.10 | 0.17 | 0.36 |

| Are you unable to sleep when not in the company of others, or when the light is off? | 0.49 | 0.28 | 0.03 | 0.32 | 0.51 | 0.27 | 0.07 | 0.34 | 0.50 | 0.24 | 0.05 | 0.31 | 0.48 | 0.22 | 0.04 | 0.28 |

| Do you have dreams of the earthquake and bad dreams? | 0.47 | 0.30 | 0.15 | 0.34 | 0.51 | 0.29 | 0.13 | 0.37 | 0.53 | 0.26 | 0.14 | 0.37 | 0.52 | 0.28 | 0.10 | 0.36 |

| Do you hate to stay at the site of the earthquake? | 0.34 | 0.15 | 0.08 | 0.15 | 0.35 | 0.15 | 0.07 | 0.15 | 0.32 | 0.14 | 0.07 | 0.13 | 0.35 | 0.13 | 0.04 | 0.14 |

| Do you get angry or irritated? | 0.06 | 0.56 | 0.03 | 0.32 | 0.08 | 0.53 | 0.05 | 0.35 | 0.11 | 0.59 | 0.03 | 0.36 | 0.10 | 0.61 | 0.02 | 0.39 |

| Are you unable to concentrate on play or study? | 0.14 | 0.50 | 0.07 | 0.28 | 0.16 | 0.51 | 0.05 | 0.29 | 0.12 | 0.56 | 0.06 | 0.34 | 0.09 | 0.57 | 0.05 | 0.33 |

| Do you have headaches, stomachaches, or palpitations, or feel dizzy? | 0.22 | 0.50 | 0.13 | 0.32 | 0.20 | 0.58 | 0.12 | 0.39 | 0.25 | 0.56 | 0.11 | 0.39 | 0.23 | 0.58 | 0.10 | 0.40 |

| Do you feel pain when talking with other people? or Are you unable to enjoy being with others? | 0.11 | 0.50 | 0.04 | 0.26 | 0.14 | 0.55 | 0.01 | 0.33 | 0.14 | 0.55 | 0.00 | 0.32 | 0.12 | 0.55 | −0.00 | 0.31 |

| Do you feel lonely or depressed? | 0.38 | 0.49 | 0.14 | 0.41 | 0.39 | 0.51 | 0.16 | 0.44 | 0.14 | 0.49 | 0.12 | 0.43 | 0.32 | 0.56 | 0.14 | 0.44 |

| Do you have any skin irritations? | 0.28 | 0.42 | 0.10 | 0.27 | 0.32 | 0.42 | 0.10 | 0.29 | 0.41 | 0.43 | 0.10 | 0.31 | 0.29 | 0.44 | 0.12 | 0.30 |

| Are you unable to sleep? Or, do you wake soon after going to bed? | 0.11 | 0.41 | 0.08 | 0.19 | 0.10 | 0.44 | 0.04 | 0.21 | 0.33 | 0.46 | 0.05 | 0.24 | 0.15 | 0.42 | 0.04 | 0.20 |

| Do you cry easily? | 0.36 | 0.41 | 0.12 | 0.31 | 0.33 | 0.40 | 0.11 | 0.33 | 0.13 | 0.43 | 0.09 | 0.33 | 0.36 | 0.41 | 0.07 | 0.31 |

| Do you want to ask someone for a help even though you can manage by yourself? | 0.15 | 0.40 | 0.08 | 0.19 | 0.14 | 0.43 | 0.09 | 0.22 | 0.36 | 0.40 | 0.08 | 0.19 | 0.16 | 0.42 | 0.04 | 0.20 |

| Are you unable to eat much or do you have a poor appetite? | 0.16 | 0.40 | 0.02 | 0.18 | 0.22 | 0.40 | 0.02 | 0.21 | 0.15 | 0.41 | 0.04 | 0.20 | 0.17 | 0.41 | 0.06 | 0.20 |

| Do you cough? | 0.14 | 0.32 | 0.05 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.35 | 0.04 | 0.15 | 0.17 | 0.39 | 0.07 | 0.19 | 0.16 | 0.37 | 0.04 | 0.17 |

| Do you strongly want to help someone in trouble? | 0.17 | 0.07 | 0.67 | 0.49 | 0.16 | 0.05 | 0.71 | 0.54 | 0.19 | 0.72 | 0.72 | 0.57 | 0.06 | 0.13 | 0.70 | 0.51 |

| Do you feel sorry for victims suffering from the earthquake? | 0.22 | 0.06 | 0.52 | 0.33 | 0.24 | 0.07 | 0.54 | 0.35 | 0.26 | 0.57 | 0.57 | 0.39 | 0.04 | 0.23 | 0.49 | 0.30 |

| Do you feel that you are helpful to somebody? | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.33 | 0.13 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.35 | 0.14 | 0.06 | 0.39 | 0.39 | 0.17 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.39 | 16.00 |

| 6.93 | 7.45 | 7.56 | 7.19 | |||||||||||||

| Sums of squares of loadings | 3.09 | 2.70 | 1.14 | 3.24 | 2.99 | 1.20 | 3.29 | 3.01 | 1.25 | 3.03 | 3.08 | 1.08 | ||||

Factor 1 is related to fear and anxiety and includes the following eight items: Do scenes of the earthquake come to mind all of sudden? Or are you afraid of another earthquake? Are you scared when not in the company of family members and friends? Are you afraid of another earthquake attack or other accidents? Are you easily frightened by small noises? Do you hate to hear or speak about the earthquake? Are you unable to sleep when not in the company of others or when the light is off? Do you have dreams of the earthquake and bad dreams? Do you hate to stay at the site of the earthquake?

Factor 2 is related to depression and physical symptoms and includes the following 11 questions: Do you get angry or irritated? Are you unable to concentrate on play or study? Do you have headaches, stomachaches or palpitations, or feel dizzy? Do you feel pain when talking with other people? Or are you unable to enjoy being with others? Do you feel lonely or depressed? Do you have any skin irritations? Are you unable to sleep? Or do you wake soon after going to bed? Do you cry easily? Do you want to ask someone for a help even though you can manage by yourself? Are you unable to eat much, or do you have a poor appetite? Do you cough?

Factor 3 is related to social responsibility (consideration for others) and includes the following 3 items: Do you strongly want to help someone in trouble? Do you feel sorry for victims suffering from the earthquake? Do you feel that you are helpful to somebody?

Analysis of Variance

Analyses of variance were performed on mean scores of the total count of factors 1, 2, and 3, and the trend and recovery process were evaluated in terms of the extent of the disaster that the children experienced, the grade of the children, their sex, and the length of time after the earthquake. Statistical Analysis System was used to further analyze each of the three factors. Each class was handled as a unit for statistical analysis. Data are expressed as means ± SD.

Results

Nearly 100% (99.9%, 99.8%, 99.8%, and 99.7%) of the children provided sufficient responses to the questionnaires carried out at 4 months, 6 months, 1 year, and 2 years after the earthquake. Three factors were consistently extracted by factor analysis on the results of each survey.

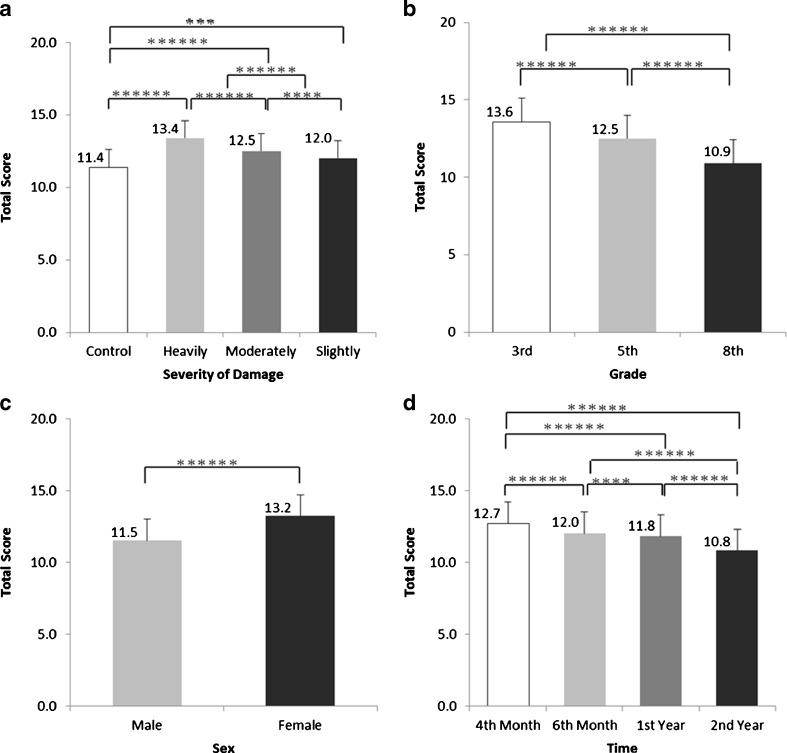

Factor 1

Factor 1 was interpreted as relating to direct fear of the disaster and general anxiety. The maximum score was 32 (achieved if all answers were “always”) and the minimum score was eight (if all answers were “none”). As shown in Fig. 2a, the highest score was demonstrated in highly damaged areas [13.4 vs. 11.4 (control), p < 0.0001]. Even in the slightly damaged areas, the difference from the control areas was statistically significant (p < 0.005). It is possible that the effects of mass media and images on television concerning the earthquake influenced the results for control children. In fact, the scores in control areas were significantly reduced 2 years after the earthquake (p < 0.005). The anxiety score was highest in the youngest (third grade) schoolchildren (Fig. 2b) and was higher in females than in males (Fig. 2c). The scores decreased over time (Fig. 2d), irrespective of grade and gender. Factor 1 was significantly associated with injuries of the children themselves (p < 0.001), fatalities/injuries of family members (p < 0.0001) or friends (p < 0.001), and an experience of being rescued (p < 0.001) or staying in a shelter (p < 0.001). These results suggest that factor 1 is directly related to the child’s experience of the earthquake.

Fig. 2.

Cluster analysis of the total scores of factor 1 (fear and anxiety) in terms of the extent of the disaster that the children experienced (a), the children’s grade (b), their sex (c), and the length of time after the earthquake (d). Each class is handled as a unit, and data are expressed as mean ± SD; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.005, ****p < 0.001, *****p < 0.0005, ******p < 0.0001

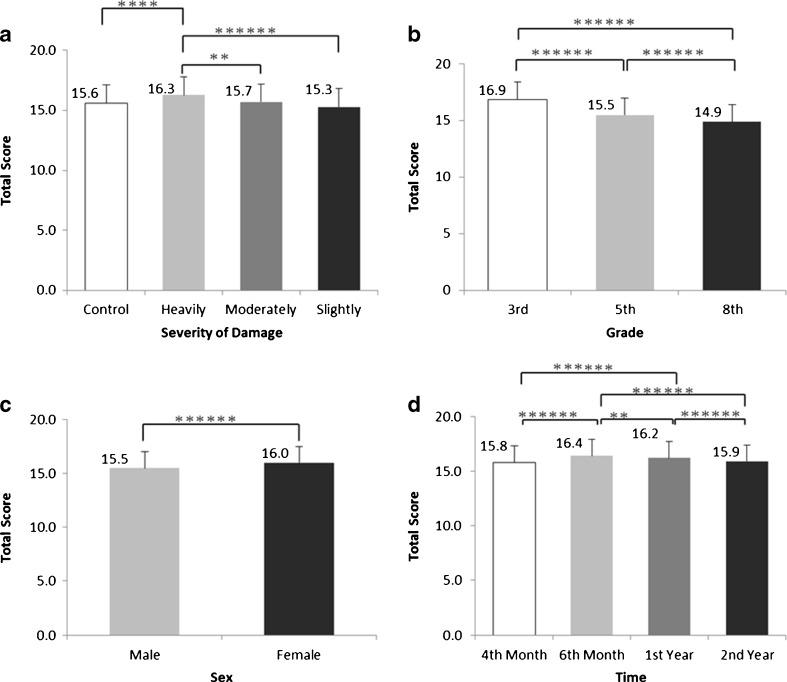

Factor 2

Factor 2 was interpreted as relating to depressive and psycho-physical symptoms. The maximum score was 44 (achieved if all answers were “always”). As shown in Fig. 3, factor 2 was strongly affected by the severity of earthquake damage experienced (Fig. 3a), the child’s grade (Fig. 3b), and gender (Fig. 3c), as was the case for factor 1. However, with regard to the extent of the disaster, statistically significant differences were observed only in heavily damaged areas. Moreover, the score at the sixth month was significantly higher than that at the fourth month (p < 0.0001), and the score returned to the level of the fourth month at 2 years after the earthquake (Fig. 3d). Factor 2 was significantly associated with injuries of the children themselves (p < 0.0001), fatalities/injuries of family members (p < 0.0001) or friends (p < 0.0001), and an experience of being rescued (p < 0.0001) or staying in a shelter (p < 0.0001). These results suggest that although factor 2 was directly related to the experience of the earthquake, it was modified by environmental changes.

Fig. 3.

Cluster analysis of the total scores of factor 2 (depression and physical symptoms) in terms of the extent of the disaster that the children experienced (a), the children’s grade (b), their sex (c), and the length of time after the earthquake (d). Each class is handled as a unit, and data are expressed as mean ± SD; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.005, ****p < 0.001, *****p < 0.0005, ******p < 0.0001

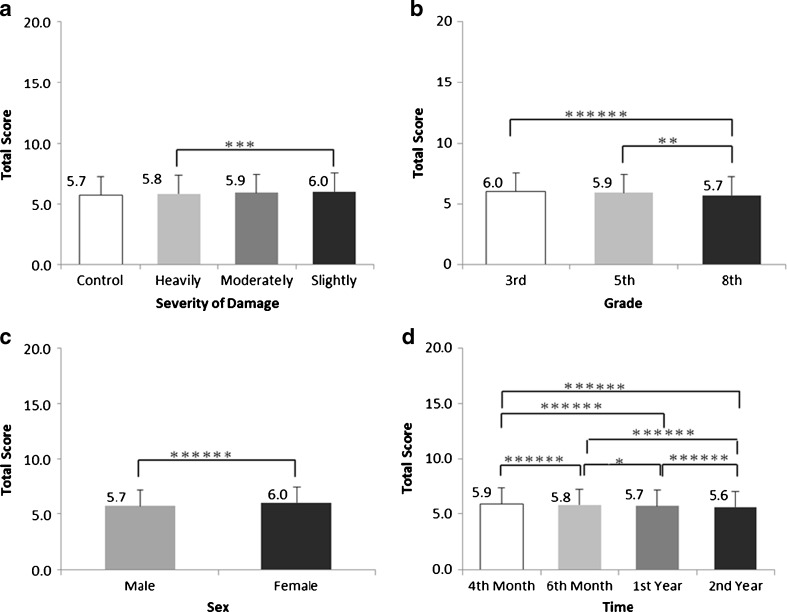

Factor 3

Factor 3 was interpreted as relating to social responsibility, such as feelings of sympathy for the people who suffered most and guilt for surviving. The maximum score was 12 (achieved if all answers were “always”).

As shown in Fig. 4, the total score of social responsibility was lowest in the heavily damaged areas (Fig. 4a). The score was significantly higher in the third and the fifth grade than in the eighth grade (Fig. 4b) and in females than in males (Fig. 4c). The score decreased over time as the effects of the disaster were being remedied (Fig. 4d). Factor 3 was significantly associated with injuries of the children themselves (p < 0.0001) and fatalities/injuries of family members (p < 0.0001).

Fig. 4.

Cluster analysis of the total scores of factor 3 (social responsibility) in terms of the extent of the disaster that the children experienced (a), the children’s grade (b), their sex (c), and the length of time after the earthquake (d). Each class is handled as a unit and data are expressed as mean ± SD; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.005, ****p < 0.001, *****p < 0.0005, ******p < 0.0001

Discussion

Disasters in urban areas have been shown to severely affect vulnerable members of society [7–9]: the elderly [2], the disabled, the women, and the children. After the Kobe earthquake, psychological care was needed to prevent suicides and alcohol dependency [9]. Privacy, income, jobs, and health were the major issues of concern at relief shelters. However, the effects of the earthquake on the mental health of children remain largely unknown.

The present survey was completed by 8,800 schoolchildren in the disaster areas. The questionnaire was originally developed based on the findings about PTSD of previous studies [4–6] and the information about PTSD in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)-IV [3]. It was applicable to children and it quantitatively measured psychological reactions after traumatic stress. High scores on the questionnaire indicated that children had many symptoms related to PTSD. The validity of the questionnaire was also supported by our study that showed a highly significant correlation with scores on the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ; unpublished data). The GHQ has been used in various countries as a screening instrument to detect potential psychiatric problems or disorders including those observed in patients with diabetes mellitus [8] and anorexia nervosa [10] and in medical staff [11] after the Kobe earthquake.

Most research on PTSD has been based on criteria in the DSM-III or the DSM-III-R and has examined adults rather than children [12]. The effects of traumatic stressors such as warfare, criminal violence, burns, and serious accidents on children have only recently been studied. Rynoos et al. [13] reported the post-traumatic stress reactions in children after the Armenian earthquake in 1988. High rates of chronic, severe PTSD reactions were found among children in the most damaged cities. PTSD consists of re-experiencing the trauma through dreams and waking thoughts, persistent avoidance of reminders of the trauma and numbing of responsiveness to such reminders, and persistent hyperarousal [14]. However, the criteria for PTSD remain controversial [15]. Furthermore, problems occur in the application of the available criteria for PTSD to victims of natural disasters [16], to young children [17], and to those with different social and cultural backgrounds. Using the questionnaire, profound post-traumatic stress reactions in school-aged children, which were subdivided into three main factors, were clearly demonstrated. Factor 1 consisted of fear and anxiety, factor 2 of depression and physical symptoms, and factor 3 of social responsibility. These factors differed based on the extent of the disaster that the children experienced, their grade and sex, and the time of the survey. Greater earthquake damage to houses and family members was associated with more severe fear, anxiety, depression, or physical symptoms. Young schoolchildren and girls were especially vulnerable. In the Armenian earthquake, girls reported more persistent fears than boys [13]. Debate continues regarding whether children are more susceptible to the development of PTSD than adults [18] and about the association of PTSD with female gender [18,19]. It appears that younger schoolchildren do not have sufficient skills to cope with life-threatening traumatic stress. Gender differences may be due to a cultural background that facilitates strong emotional reactions in females [20] or to preexisting levels of anxiety in females [21]. Although fear and anxiety symptoms tended to lessen by 1 year after the earthquake, depression and physical symptoms became more evident 6 months to 1 year after the earthquake. Because psychic trauma in childhood frequently results in arrested emotional development [14], long-term psychological consequences are a serious concern. The consequences of psychic trauma are often underestimated and even mental health services often fail to provide adequate care [22]. In the Armenian earthquake, untreated adolescents who were exposed to severe trauma were at risk for chronic PTSD and depressive symptoms [23]. However, brief trauma/grief-focused psychotherapy was effective in reducing PTSD symptoms and halting the progression of depression [23].

The Kobe earthquake exposed serious flaws in the Japanese emergency services. The scale of the earthquake was beyond all expectations and the contingency plans for a large disaster proved to be inadequate [2]. On March 11, 2011, a magnitude 9.0 earthquake struck northeastern Japan but seismic risk assessments, tsunami preparedness, and the hardiness of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant did not meet expectations, and emergency plans were again inadequate. Even a highly organized and affluent society may come to a standstill when it experiences such a substantial disaster [2]. The need to revise earthquake probability analyses extends far beyond Japan [24].

The phenomenon of PTSD and the course of the illness may differ based on the nature of the traumatic events as well as in unique populations of individuals such as children [25]. The current study extracted and quantified the core features of the post-traumatic stress reactions in 8,800 schoolchildren after the disastrous Kobe earthquake. This study strongly indicates the need for the comprehensive treatment of child trauma victims, including medical and welfare treatment. Psychological interventions should be targeted toward young schoolchildren in regions affected by the recent earthquake.

Acknowledgments

This study was founded by the Education Committee of Kobe City and presented at the first meeting of the Children and Adolescents Psychiatric Society. We would like to thank Akihiko Shioyama, MD, PhD; Wataru Seki, MD; Masako Honda, CP; Hiroshi Osabe, MA; Ryoji Natsuno, MA; Shigeki Mori, MA; Naotaka Shinfuku, MD, PhD; Masako Honda, CP; Keiko Shirakawa, CP; Chika Yonenaga, CP; and the teachers and students for their cooperation.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Normile D. Kobe earthquake. Faculty picks up the pieces of shattered research projects. Science. 1995;268:1429–1431. doi: 10.1126/science.268.5216.1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tanida N. What happened to elderly people in the great Hanshin earthquake. BMJ. 1996;313:1133–1135. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7065.1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Psychiatric Association, Committee on Nomenclature and Statistics . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pynoos RS, Frederick C, Nader K, et al. Life threat and posttraumatic stress in school-age children. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1987;44:1057–1063. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800240031005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pynoos RS, Nader K. Children who witness the sexual assaults of their mothers. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1988;27:567–572. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198809000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brent DA, Perper JA, Meritz G, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder in peers of adolescent suicide victims: predisposing factors and phenomenology. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;34:209–215. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199502000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raphael B. When disaster strikes: how individuals and communities cope with catastrophe. New York: Basic Books; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Inui A, Kitaoka H, Majima M, et al. Effect of the Kobe earthquake on stress and glycemic control in patients with diabetes mellitus. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:274–278. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.3.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baba S, Taniguchi H, Nambu S, Tsuboi S, Ishihara K, Osato S. The great Hanshin earthquake. Lancet. 1996;347:307–309. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)90473-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Inui A, Uemura T, Honda M, Uemoto M, Kasuga M, Taniguchi H. Kobe earthquake and the patients with anorexia nervosa. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:464–465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Uemoto M, Inui A, Shindo S, Kasuga M, Taniguchi H. Kobe earthquake and psychology of medical staff. BMJ. 1997;313:1144. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7065.1144a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McNally RJ. Stress that produce posttraumatic stress disorder in children. In: Davidson JRT, Foa EB, editors. Posttraumatic stress disorder, DSM-IV and beyond. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1993. pp. 57–74. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pynoos RS, Goenjian A, Tashjian M, Karakashian M, Manjikian R, Manoukian G, Steinberg AM, Fairbanks LA. Post-traumatic stress reactions in children after the 1988 Armenian earthquake. Br J Psychiatry. 1993;163:239–247. doi: 10.1192/bjp.163.2.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaplan HI, Sadock BJ, Grebb JA. Posttraumatic stress disorder and acute stress disorder. Synopsis of psychiatry. Seventh edition, chapter 16. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 1994. pp. 606–611. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Solomon SD, Gerrity ET, Muff AM. Efficacy of treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder. JAMA. 1992;268:633–638. doi: 10.1001/jama.1992.03490050081031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shore JH, Volmer WM, Tatum EL. Community patterns of posttraumatic stress disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1989;177:681–685. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198911000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Green BL, Korol M, Grace MC, Vary MG, Leonard AC, Gleser GC, Smitson-Cohen S. Children and disaster: age, gender, and parenteral effect on PTSD symptoms. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1991;30:945–951. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199111000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Quinn KM. Guidlines for the psychiatric examination of posttraumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents. In: Simon RI, editor. Posttraumatic stress disorder in litigation. Guidelines for forensic assessment. Chapter 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1995. pp. 85–98. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Breslau N, Davis GC, Andreski P, Peterson E. Traumatic events and posttraumatic stress disorder in an urban population of young adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48:216–222. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810270028003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Milgram NA, Toubiana YH, Kingman A. Situational exposure and personal loss in children’s acute and chronic stress reactions to a school bus disaster. J Trauma Stress. 1988;1:339–352. doi: 10.1002/jts.2490010306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shannon MP, Lonigan CJ, Finch AJ, Jr, Taylor CM. Children exposed to disaster: I. Epidemiology of post-traumatic symptoms and symptom profiles. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1994;33:80–93. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199401000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gersons BPR, Carlier IVE. Post-traumatic stress disorder: the history of a recent concept. Br J Psychiatr. 1992;161:742–748. doi: 10.1192/bjp.161.6.742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goenjian AK, Walling D, Steinberg AM, Karayan I, Najarian LM, Pynoos R. A prospective study of posttraumatic stress and depressive reactions among treated and untreated adolescents 5 years after a catastrophic disaster. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(12):2302–2308. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.12.2302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Normile D. Japan disaster. Scientific consensus on great quake came too late. Science. 2011;332(6025):22–23. doi: 10.1126/science.332.6025.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu M, Wang L, Shi Z, Zhang Z, Zhang K, Shen J. Mental health problems among children one-year after Sichuan earthquake in China: a follow-up study. PLoS One. 2011;6(2):e14706. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]