Abstract

Objectives

The purpose of this study was to determine the immediate and long-term effects of intraplaque hemorrhage (IPH) on plaque progression in the carotid artery.

Background

Previous studies have associated IPH in the carotid artery with more rapid plaque progression. However, the time course and long-term effect remain unknown. Carotid magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a non-invasive imaging technique that has been validated with histology for the accurate in vivo detection of IPH and measurement of plaque burden.

Methods

Asymptomatic subjects with 50–79% carotid stenosis underwent carotid MRI at baseline and then serially every 18 months for a total of 54 months. Subjects with IPH present in at least one carotid artery at 54 months were selected. Subsequently, presence/absence of IPH and wall volume were determined independently in all time points for both sides. A piecewise progression curve was fit using linear mixed model to compare progression rates defined as annualized changes in wall volume between periods defined by their relationship to IPH development.

Results

From 14 patients that showed IPH at 54 months, 12 arteries were found to have developed IPH during the study period. The progression rates were −20.5±13.1, 20.5±13.6 and 16.5±10.8 mm3/year before, during and after IPH development, respectively. The progression rate during IPH development tended to be higher than the period before (p=0.080), but comparable to the period after (p=0.845). The progression rate in the combined period during/after IPH development was 18.3±6.5 mm3/year, which indicated significant progression (p=0.008 compared to a slope of 0) and was higher than the period before IPH development (p=0.018). No coincident ischemic events were noted for new IPH.

Conclusions

The development of IPH posed an immediate and long-term promoting effect on plaque progression. IPH appears to alter the biology and natural history of carotid atherosclerosis. Early identification of patients with IPH may prove invaluable in optimizing management to minimize future sequelae.

Keywords: carotid arteries, intraplaque hemorrhage, atherosclerosis, magnetic resonance imaging

Introduction

There is increasing evidence that intraplaque hemorrhage (IPH) is associated with the high-risk atherosclerotic carotid plaque. Prospective studies have identified a compelling link between the presence of IPH at baseline and the development of future ischemic cerebrovascular events in both previously asymptomatic and symptomatic individuals (1–3). IPH has also been associated with a more rapid growth of the lipid-rich necrotic core (LRNC) and accelerated progression in plaque burden that appears to induce luminal narrowing regardless of initial stenotic severity (4, 5). However, the time course of these deleterious effects remains undefined.

Understanding the immediate and long-term implications of IPH is particularly compelling. IPH has been identified across a wide spectrum of stenosis and/or plaque burden (6–8). The acceleration of plaque growth upon IPH development, if visualized in the same artery, will support IPH as a direct promoter for plaque progression. The duration of its effects, on the other hand, may primarily determine the clinical significance of IPH, especially those in lesions without luminal stenosis and with minimal plaque burden (6, 7).

In this study, we sought to determine the time course of effects of IPH in the carotid artery. We designed a retrospective study consisting of participants enrolled in an ongoing natural history study of carotid atherosclerotic disease imaged every 18 months for 54 months with carotid magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Carotid MRI is a non-invasive imaging technique validated with histology for the accurate in vivo detection of IPH and has become an established approach for identifying IPH during cross-sectional and longitudinal studies (9–11).

Methods

Study Sample

As part of a natural history study of carotid atherosclerotic disease, patients were recruited from the diagnostic vascular ultrasound laboratories at the University of Washington Medical Center, Veterans Affairs Puget Sound, and the Virginia Mason Medical Center with the following inclusion criteria: 1) 50–79% stenosis in at least one carotid artery; and 2) no cerebrovascular symptoms in the 6 months prior to enrollment. Study procedures and consent forms were reviewed and approved by the institutional review board at each site. Written informed consent was obtained before enrollment.

Subjects underwent carotid MRI at baseline and then serially every 18 months for a total of 54 months. Routine medical care was directed by the subjects’ primary care physicians during the entire study duration. At the baseline MRI, a standardized health questionnaire was completed and physical examination was performed. Regular follow-ups were done every 3 months by telephone interview to record recent cerebrovascular events, occurrence of carotid endarterectomy (CEA), and current medications. Patients who gave a history suggestive of an ischemic event during the telephone interviews were evaluated and confirmed by the study neurologist.

Imaging criteria for study inclusion were: 1) 54 months of imaging follow-up; and 2) IPH present (see Image Review for criteria to determine presence/absence of IPH) in at least one carotid artery at the most recent scan. Exclusion criteria were: 1) previous history of CEA; and 2) image quality <2 (see Image Review for description of image quality).

MRI Protocol

All images were acquired on a 1.5 T scanner (Signa Horizon EchoSpeed, GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, Wisconsin) using phased-array surface coils (Pathway, Seattle, Washington). A standardized carotid MRI protocol was used to acquire multi-contrast, cross-sectional images (3D time-of-flight [TOF], T1-weighted [T1w], proton density-weighted [PDw], and T2-weighted [T2w]) centered at the bifurcation of the carotid artery with 50–79% stenosis, referred to as the index artery, as previously described (12, 13). When both arteries demonstrated 50–79% stenosis at baseline, one artery was randomly chosen as the index artery for centering of coverage during image acquisition. During subsequent acquisitions, the index artery was always used for centering unless a CEA was performed on the index artery in which case centering of coverage was switched to the contralateral side. Images were obtained with a field-of-view of 13 to 16 cm, matrix size of 256 × 256, and 2 mm slice thickness. There was 1 mm of overlap between adjacent slices for TOF and no interslice spacing for other sequences. Scan coverage was 40 mm for TOF, 20–24 mm for T1w, and 30 mm for PDw and T2w. Total acquisition time was approximately 30 minutes.

Image Review

All image interpretation was performed using a custom-designed image analysis software package (CASCADE, Seattle, Washington) (14) by researchers trained in carotid MRI and blinded to clinical data. Image quality (ImQ) was rated per scan on a 4-point scale (1 = poor, 4 = excellent), consistent with previous studies (15). Scans with ImQ < 2 were excluded. Different weightings were registered during image review using the carotid bifurcation as a reference. Scans without a carotid bifurcation within the field-of-view were excluded.

The presence/absence of IPH in either carotid at the final (54 months) time point (TP) was determined by a hyperintense signal on T1w and TOF images consistent with the presence of IPH as previously validated with histology at 1.5T (9). Participants with IPH at the 54 month TP in at least one carotid artery were selected for additional image review that included both carotid arteries (i.e. IPH arteries and their contralateral arteries) and also included all previous TPs (TP1 = baseline scan, TP2 = 18 months, TP3 = 36 months, TP4 = 54 months). Multiple scans were matched blinded to time sequence using the carotid bifurcation for each participant. Only slices covered at all TPs were used for analysis. Wall volume and presence of IPH were determined independently at all TPs. PDw/T2w images were used to measure wall volume blinded to presence/absence of IPH. TOF/T1w images were used to determine presence/absence of IPH blinded to the results from wall volume measurements.

Statistical Analysis

Summary statistics of baseline demographics were presented as mean±standard deviation for continuous variables and count with percentage for categorical variables. Common coverage across multiple serial scans was presented as range with median for both TOF/T1w and PDw/T2w series. Serial data on IPH status were used to identify arteries with new IPH. Wall volume was calculated by summing up wall areas on matched slices multiplied by slice thickness, which was then normalized for varying numbers of slices to yield a volume for 10 slices (wall volume/number of slices × 10 slices) (4).

In arteries with new IPH during the study period, the inter-scan interval when new IPH occurred was defined as the IPH-new period. Periods before and after the IPH-new period were defined as the IPH-absent and IPH-present periods. To compare progression rates between the three periods, and between the IPH-absent and the combined IPH-new/IPH-present period, a linear mixed model approach was used (16). After re-centering the scan times around the occurrence of IPH (time = 0 when IPH was first observed), a piecewise linear curve was fit between wall volume and time, with knots set at boundaries between periods. A random intercept was included in the model to account for the dependence between multiple scans of the same artery. Slopes±standard errors of the piecewise linear curve correspond to progression rates in wall volume during different periods, which were compared with 0 and with each other using Wald tests.

For the other arteries that did not show new IPH during the study period, the same linear mixed model approach was used to estimate their long-term average progression rates by fitting a single line over the entire study period (16).

All data analysis was performed using R 2.11.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Statistical significance was defined as P<0.05.

Results

Fourteen subjects with 54 month follow-up had imaging evidence of IPH in at least one carotid artery at their most recent scan. Baseline demographics are shown in Table 1. In these 14 participants (n=28 carotid arteries), there were 17 carotid arteries with IPH present on MRI, 10 carotid arteries without IPH on MRI, and 1 artery was excluded due to CEA during the 54 month study period. The arteries at 54 months with (n=17) and without (n=10) IPH were selected to have their previous time point scans analyzed. Accordingly, 108 scans (27 arteries×4 time points) were available for review.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics at baseline (N=14).

| Mean±SD or n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 71.3±11.3 |

| Gender: male | 13 (92.9) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 28.0±3.8 |

| Current smoker | 5 (35.7) |

| Hypertension* | 12 (85.7) |

| Diabetes mellitus* | 2 (14.3) |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 12 (85.7) |

| History of CHD | 6 (42.9) |

| Statin therapy | 9 (64.3) |

| Anti-platelet agents | 11 (78.6) |

| Aspirin | 10 (71.4) |

| Clopidogrel | 1 (7.1) |

| Cilostazol | 1 (7.1) |

All subjects with hypertension and diabetes were on corresponding medications at enrollment.

No subject was on anti-coagulant at enrollment. CEA = carotid endarterectomy; CHD = coronary heart disease; IPH = intraplaque hemorrhage; SD = standard deviation.

During the review of TOF/T1w series for IPH, 1 (3.7%) of the 27 arteries was excluded due to lack of coverage of the carotid bifurcation at TP1 and TP2. The remaining 26 arteries had serial data on IPH status at all four TPs. The common coverage of TOF/T1w images across four scans ranged from 10 to 20 mm (median: 16 mm). During the review of PDw/T2w series for wall volume measurements, 16 (14.8%) scans were excluded due to poor image quality. This left 26 arteries with wall volume measurements at 2 to 4 TPs. The common coverage of PDw/T2w images ranged from 10 to 28 mm (median: 24 mm).

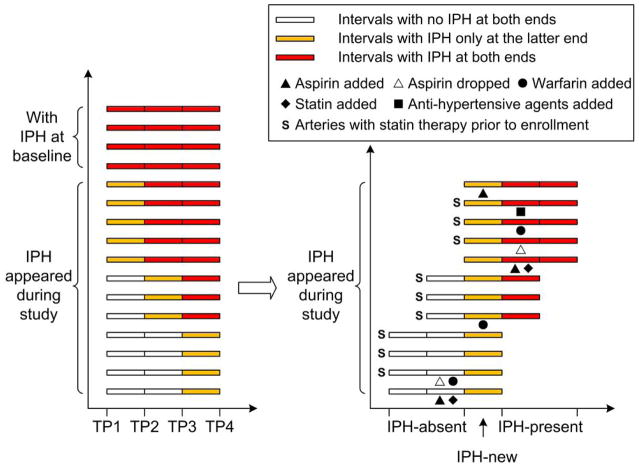

Occurrence of IPH

Of the 26 arteries with serial data on IPH, 4 (15.4%) had IPH present at all TPs (IPH-present group, Figure 1); 12 arteries (46.2%) did not have IPH at the baseline scan and had IPH on all subsequent scans following the occurrence of IPH (IPH-new group, Figure 2); 10 arteries (38.5%) did not have IPH at any TPs (IPH-absent group). Resolution of IPH was not observed. Of the 12 arteries with new IPH, 10 (83.3%) were on statin therapy when IPH occurred (Figure 3).

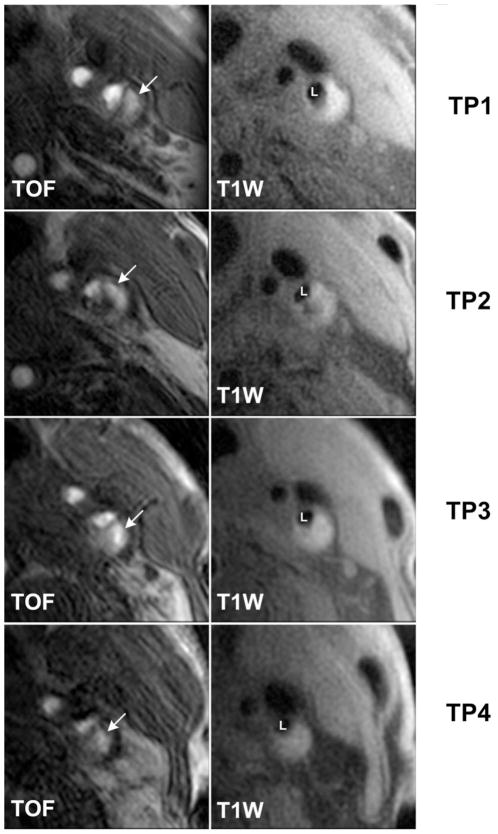

Figure 1. A representative case of arteries with IPH at all scans.

White arrows indicate the presence of IPH at all TPs shown as bright areas on TOF images. IPH = intraplaque hemorrhage; L = lumen of internal carotid artery; T1W = T1-weighted; TOF = time-of-flight;; TP = time point.

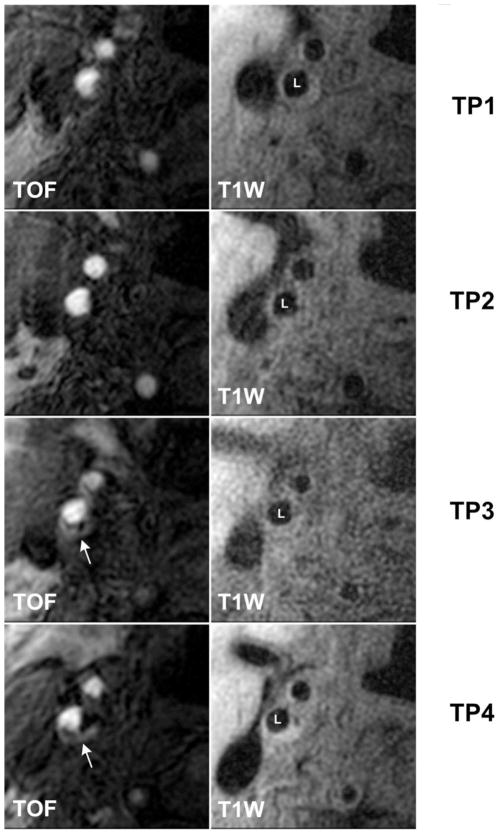

Figure 2. A representative case of arteries with incident IPH.

White arrows indicate the presence of IPH at TP3/TP4 shown as bright areas on TOF images. The IPH signal was absent at TP1/TP2. IPH = intraplaque hemorrhage; L = lumen of internal carotid artery; T1W = T1-weighted; TOF = time-of-flight;; TP = time point.

Figure 3. Serial data on presence/absence of IPH and medications.

(A) Four arteries showed IPH at all scans. Twelve arteries did not show IPH at baseline and showed IPH at all subsequent scans following the occurrence of IPH. (B) Arteries are aligned according to when IPH first appeared. Three consecutive periods are defined (IPH-absent, IPH-new, IPH-present). Arteries on statin therapy prior to enrollment are marked with “S”. Changes in relevant medications during study are marked under corresponding intervals. IPH = intraplaque hemorrhage; TP = time point.

Long-term Effects of IPH

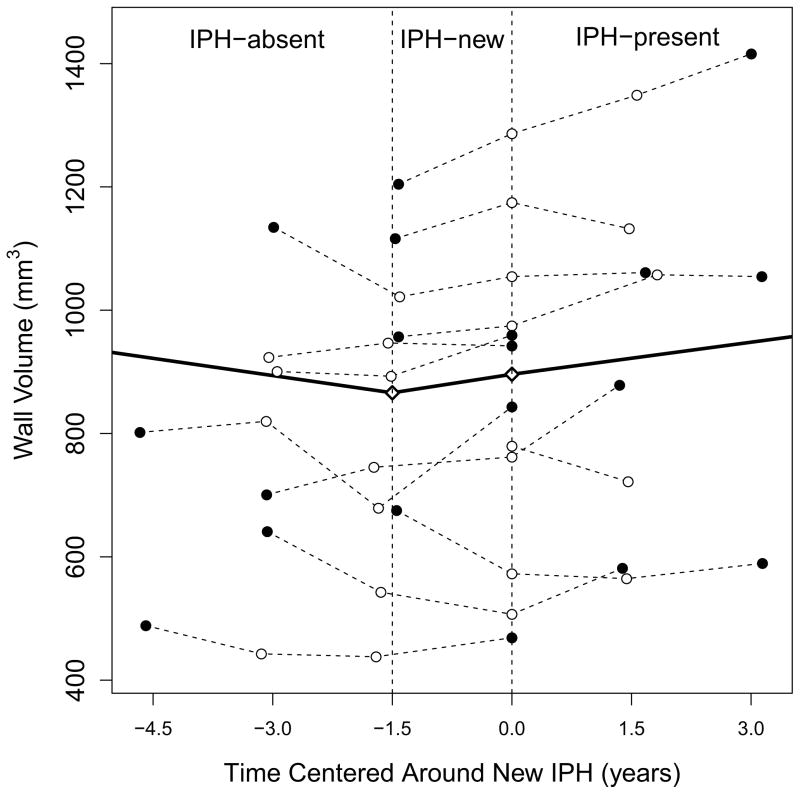

The annualized change in wall volume during the IPH-absent period was −20.5±13.1 mm3 per year (p=0.129 compared to a slope of 0). Of the 7 arteries with an IPH-absent period, 6 (85.7%) were on statin therapy and 1 (14.3%) initiated statin therapy during this period (Figure 3). During the 18 month IPH-new period, the annualized change in wall volume was 20.5±13.6 mm3 per year (p=0.141 compared to a slope of 0). Nine (81.8%) of the 11 arteries with an IPH-new period were on statin therapy during this period (Figure 3). The annualized change in wall volume in the IPH-present period was 16.5±10.8 mm3 per year (p=0.138 compared to a slope of 0). Six (75.0%) of the 8 arteries with an IPH-present period were on statin therapy and 1 (12.5%) initiated statin therapy during this period (Figure 3). The annualized change in wall volume during the IPH-new period tended to be greater than that during the IPH-absent period (p=0.080 for difference of slope), but comparable to that during the IPH-present period (p=0.845 for difference of slope). The annualized change in wall volume during the IPH-new/IPH-present period was 18.3±6.5 mm3 per year (p=0.008 compared to a slope of 0), which is significantly higher than that during the IPH-absent period (p=0.018 for difference of slope).

The average progression rates over the entire study period of IPH-present and IPH-absent arteries were 34.2±9.0 mm3 per year (p=0.004 compared to a slope of 0) and 5.3±7.2 mm3 per year (p=0.466 compared to a slope of 0), respectively. All IPH-present arteries were on statin therapy during the study period. Of the IPH-absent arteries, 7 (77.8%) were on statin therapy during the study period and 1 (11.1%) initiated statin therapy before its TP2 scan.

All of the 14 patients with IPH at TP4 remained clinically asymptomatic during the entire study period.

Discussion

In this study that utilized serial images of the in vivo carotid artery over a 54 month period, the development of IPH was found to be associated with an immediate and long-term acceleration of plaque progression compared to the period before. These observations expand our understanding of the potentially central role that IPH contributes to carotid atherosclerotic disease in two important ways. First, acceleration of plaque growth was seen coincidently with new IPH, suggesting IPH as a direct promoter rather than a bystander in plaque progression. And second, the accelerating effects of IPH did not resolve after an extended period of observation. These findings substantiate previous animal studies (17) and human studies of a shorter duration (4, 5) that conjectured the presence of IPH may fundamentally alter the biology of atherosclerotic disease. Therefore, the early identification of patients with IPH regardless of stenotic severity or plaque burden may prove invaluable in optimizing management to minimize future sequelae.

Although previous studies have identified an association between IPH and stroke (1, 3, 18), the results have largely been presented in the form of increased event risk. In the present study, no coincident clinical symptoms were noted for new IPH. The observation is supported by histopathological studies that have identified neovasculature originating from the adventitia as a potential source of IPH (19, 20), which enables the development of IPH without disruption of the plaque surface. Collectively, it’s implied that the identification of IPH may stratify patients with an advanced rate of plaque growth, but additional features such as surface disruption may need to be identified to better delineate patients at greatest risk for stroke (21, 22). Nevertheless, due to the small sample size in this study, whether the occurrence of new IPH is directly linked with cerebrovascular events needs to be further investigated.

Statin therapy improves prognosis of cardiovascular disease and has been shown to decrease plaque burden in multiple imaging studies (23–25). We found that 12 arteries developed new IPH during the study period despite the fact that 10 (83.3%) of them were on statin therapy when IPH occurred. The 4 arteries with IPH present throughout the 54 month study period were progressing despite statin therapy, as did the 12 arteries with new IPH after IPH developed. These findings suggest that statin therapy alone may be insufficient to prevent arteries from developing IPH and the effects of IPH may outweigh statin therapy in determining plaque progression. Further studies are needed to verify these observations in clinical trials.

Methemoglobin from hemoglobin breakdown after erythrocyte extravasation has been proposed to account for the high signal intensity of IPH. However, the MR signal of IPH is distinctively durable compared to hemorrhage in other pathological settings (26, 27). Using a T1-weighted sequence for IPH detection, Yamada et al reported that only 1 of 30 high signal intensity carotid arteries changed to low signal intensity during a median interval of 279 days (range: 10–1037 days) (18). Two other studies using combined TOF and T1-weighted sequences for IPH detection did not report any disappearance of IPH over an 18 month period (4, 5). Although the current study was not designed to study the resolution of IPH, we found that the hyper-intense signal of IPH could last for as long as 54 months. One possible explanation for this phenomenon is that erythrocytes may continue to extravasate from leaky vessels once IPH occurs (4, 20). Alternatively, the intraplaque environment may be unique and yields an atypical degradation of hemoglobin. Regardless, hemorrhage as detected by MRI clearly persists in carotid atherosclerotic disease and further studies targeted at understanding this unique occurrence may benefit the understanding of the atherosclerotic disease process.

Study Limitations

This study was limited by its small sample size, which was primarily because the design required that study participants not only have four serial scans using the same carotid imaging protocol but also show IPH on the last scan. However, this is the first study to serially monitor at regular intervals the natural history of atherosclerosis over an extended period. In so doing, we found that the common coverage of four serial scans was generally smaller compared to each individual scan alone, but was comparable to previous longitudinal studies which used only two time point scans (5, 28). In addition, the available coverage was sufficient to cover lesions at the carotid bifurcation as is consistent with previous reports (8). In accord, this study provides compelling evidence that monitoring plaque progression using serial imaging with a validated MRI protocol is a promising approach for the long-term, wide-scale studies of in vivo human atherosclerosis.

Conclusions

In conclusion, MRI monitoring of carotid arteries over a 54 month period demonstrated the development of IPH and the concurrent acceleration of plaque growth despite a high prevalence of statin therapy in affected arteries. IPH appears to fundamentally alter the biology and natural history of carotid atherosclerosis.

Figure 4. Trajectories of wall volume over time in relation to IPH.

Each thin dashed line represents one artery which developed IPH during the study. Closed points mark the first/last time point scans while open points mark the middle scans. T=0 is when IPH was first observed. The thick solid line is the piecewise linear progression curve fit using a linear mixed model with knots indicated as diamonds. The vertical dashed lines indicate the boundaries between IPH-absent, IPH-new and IPH-present periods. Note that while IPH status was known for all time points, in some cases wall volume measurements could not be made due to image quality. Consequently, some arteries have a reduced number of data points. IPH = intraplaque hemorrhage.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: Supported by National Institute of Health grants R01 HL061851, P01 HL072262 and R01 HL073401.

Abbreviations

- 3D

3-dimentional

- CEA

carotid endarterectomy

- ImQ

image quality

- IPH

intraplaque hemorrhage

- LRNC

lipid-rich necrotic core

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- PDw

proton-density-weighted

- T1w

T1-weighted

- T2w

T2-weighted

- TOF

time-of-flight

- TP

time point

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Takaya N, Yuan C, Chu BC, et al. Association between carotid plaque characteristics and subsequent ischemic cerebrovascular events - A prospective assessment with MRI - Initial results. Stroke. 2006;37:818–23. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000204638.91099.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altaf N, Daniels L, Morgan PS, et al. Detection of intraplaque hemorrhage by magnetic resonance imaging in symptomatic patients with mild to moderate carotid stenosis predicts recurrent neurological events. J Vasc Surg. 2008;47:337–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.09.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh N, Moody AR, Gladstone DJ, et al. Moderate Carotid Artery Stenosis: MR Imaging-depicted Intraplaque Hemorrhage Predicts Risk of Cerebrovascular Ischemic Events in Asymptomatic Men. Radiology. 2009;252:502–8. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2522080792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takaya N, Yuan C, Chu BC, et al. Presence of intraplaque hemorrhage stimulates progression of carotid atherosclerotic plaques - A high-resolution magnetic resonance Imaging study. Circulation. 2005;111:2768–75. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.504167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Underhill HR, Yuan C, Yarnykh VL, et al. Arterial remodeling in the subclinical carotid artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol Img. 2009;2:1381–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2009.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dong L, Underhill HR, Yu W, et al. Geometric and compositional appearance of atheroma in an angiographically normal carotid artery in patients with atherosclerosis. Am J Neuroradiol. 2010;31:311–6. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhao X, Underhill HR, Zhao Q, et al. Discriminating Carotid Atherosclerotic Lesion Severity by Luminal Stenosis and Plaque Burden: A Comparison Utilizing High-Resolution Magnetic Resonance Imaging at 3. 0 Tesla. Stroke. 2010;42:347–53. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.597328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saam T, Underhill HR, Chu BC, et al. Prevalence of American heart association type VI carotid atherosclerotic lesions identified by magnetic resonance imaging for different levels of stenosis as measured by duplex ultrasound. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:1014–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.10.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yuan C, Mitsumori LM, Ferguson MS, et al. In vivo accuracy of multispectral magnetic resonance imaging for identifying lipid-rich necrotic cores and intraplaque hemorrhage in advanced human carotid plaques. Circulation. 2001;104:2051–6. doi: 10.1161/hc4201.097839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moody AR, Murphy RE, Morgan PS, et al. Characterization of complicated carotid plaque with magnetic resonance direct thrombus imaging in patients with cerebral ischemia. Circulation. 2003;107:3047–52. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000074222.61572.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cappendijk VC, Cleutjens K, Heeneman S, et al. In vivo detection of hemorrhage in human atherosclerotic plaques with magnetic resonance imaging. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2004;20:105–10. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cai JM, Hastukami TS, Ferguson MS, Small R, Polissar NL, Yuan C. Classification of human carotid atherosclerotic lesions with in vivo multicontrast magnetic resonance imaging. Circulation. 2002;106:1368–73. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000028591.44554.f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yarnykh VL, Yuan C. Current Protocols in Magnetic Resonance Imaging. New York: Wiley; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kerwin W, Xu D, Liu F, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of carotid atherosclerosis: plaque analysis. Top Magn Reson Imaging. 2007;18:371–8. doi: 10.1097/rmr.0b013e3181598d9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Underhill HR, Hatsukami TS, Cai J, et al. A Noninvasive Imaging Approach to Assess Plaque Severity: The Carotid Atherosclerosis Score. Am J Neuroradiol. 2010;31:1068–75. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diggle PJ, Heagerty PJ, Liang KY, Zeger SL. Analysis of Longitudinal Data. Great Britain: Oxford University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kolodgie FD, Gold HK, Burke AP, et al. Intraplaque hemorrhage and progression of coronary atheroma. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2316–25. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamada N, Higashi M, Otsubo R, et al. Association between signal hyperintensity on T1-weighted MR imaging of carotid plaques and ipsilateral ischemic events. Am J Neuroradiol. 2007;28:287–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sluimer JC, Kolodgie FD, Bijnens A, et al. Thin-Walled Microvessels in Human Coronary Atherosclerotic Plaques Show Incomplete Endothelial Junctions Relevance of Compromised Structural Integrity for Intraplaque Microvascular Leakage. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:1517–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.12.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Virmani R, Kolodgie FD, Burke AP, et al. Atherosclerotic plaque progression and vulnerability to rupture: angiogenesis as a source of intraplaque hemorrhage. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:2054–61. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000178991.71605.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wasserman BA. Advanced contrast-enhanced MRI for looking beyond the lumen to predict stroke: building a risk profile for carotid plaque. Stroke. 2010;41:S12–6. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.596288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ota H, Yu W, Underhill HR, et al. Hemorrhage and Large Lipid-Rich Necrotic Cores Are Independently Associated With Thin or Ruptured Fibrous Caps An In vivo 3T MRI Study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29:1696–701. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.192179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Corti R, Fayad ZA, Fuster V, et al. Effects of Lipid-Lowering by Simvastatin on Human Atherosclerotic Lesions: A Longitudinal Study by High-Resolution, Noninvasive Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Circulation. 2001;104:249–52. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.104.3.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee JM, Wiesmann F, Shirodaria C, et al. Early changes in arterial structure and function following statin initiation: quantification by magnetic resonance imaging. Atherosclerosis. 2008;197:951–8. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Underhill HR, Yuan C, Zhao XQ, et al. Effect of rosuvastatin therapy on carotid plaque morphology and composition in moderately hypercholesterolemic patients: A high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging trial. Am Heart J. 2008;155:581–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bradley WJ. MR appearance of hemorrhage in the brain. Radiology. 1993;189:15–26. doi: 10.1148/radiology.189.1.8372185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fraser DG, Moody AR, Morgan PS, Martel AL, Davidson I. Diagnosis of lower-limb deep venous thrombosis: a prospective blinded study of magnetic resonance direct thrombus imaging. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:89–98. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-2-200201150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Underhill HR, Yuan C, Yarnykh VL, et al. Predictors of Surface Disruption with MR Imaging in Asymptomatic Carotid Artery Stenosis. Am J Neuroradiol. 2010;31:487–93. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]