History

A 27-year-old Filipino female, who was previously treated for otitis media, presented following a 2-year history of bilateral cervical lymphadenopathy and ear pain. At her most recent visit, she presented with chief complaints of headache, occasional dizziness, diplopia, epistaxis, and numbness of the left side of her face. Abduction of the left eye was impaired, and a visibly large left cervical neck mass was present.

Radiographic Features

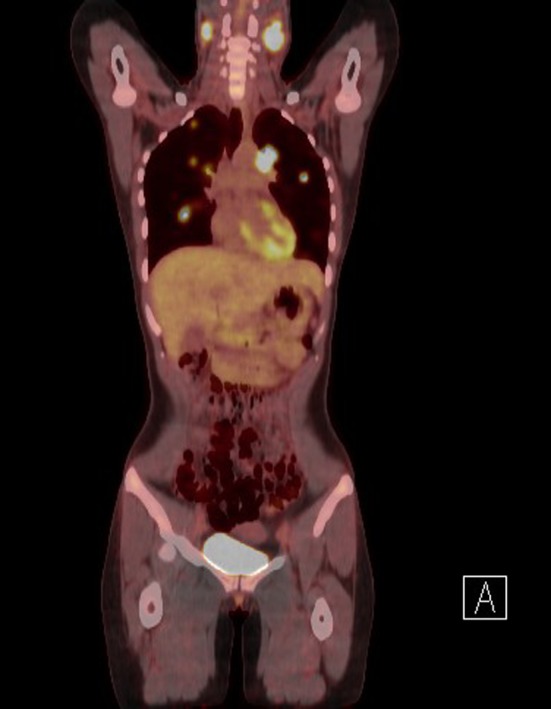

A sagittal T1-weighted magnetic resonance (MR) image of the current case demonstrated abnormal marrow signal within the clivus (Fig. 1), which in this case, indicated direct extension of tumor. An axial T1-weighted pre-contrast MR image demonstrated a mass that favored the left pharyngeal space and extended into the adjacent parapharyngeal space (Fig. 2). An axial T1-weighted post-contrast MR image demonstrated contrast enhancement within this mass, and at the level of the pterygopalatine fossa, perineural spread of tumor along the left trigeminal V2 segment (Fig. 3) was noted. Positron emission tomography of the current case revealed numerous bilateral pulmonary nodules within the lung parenchyma and in subpleural locations (Fig. 4). In addition, a large soft tissue-density mass was identified posterior to the nasopharynx and extending to both sides of the midline. The mass extended anteriorly behind the left maxillary sinus and displaced the wall of the sinus. On the right side, the mass extended posterolaterally. There were large level V masses in the upper posterior neck bilaterally as well as smaller level V lymph nodes in the lower cervical region. A level IIb mass was present in the left neck.

Fig. 1.

Sagittal T1-weighted MRI demonstrating abnormal marrow signal when compared to vertebral bodies below

Fig. 2.

Axial T1-weighted MRI demonstrating a left pharyngeal space mass extending into the adjacent parapharyngeal space

Fig. 3.

Axial T1-weighted post-contrast MRI demonstrating perineural spread of tumor along the left trigeminal V2 segment

Fig. 4.

Positron emission tomography highlighting bilateral neck and lung tumor nodules

Diagnosis

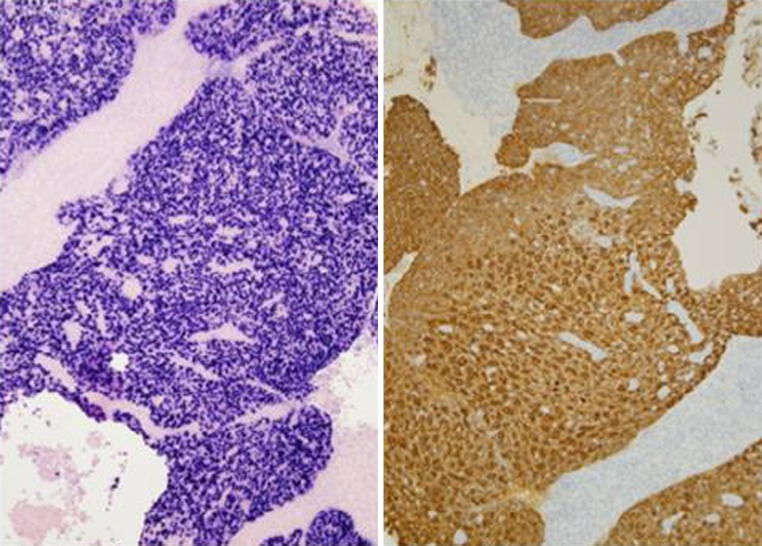

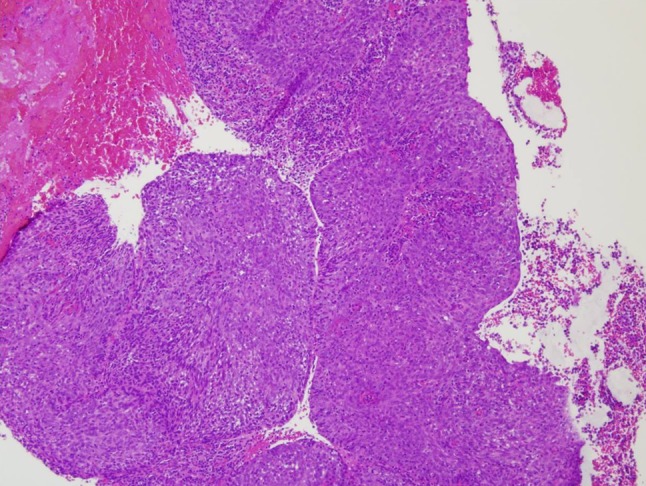

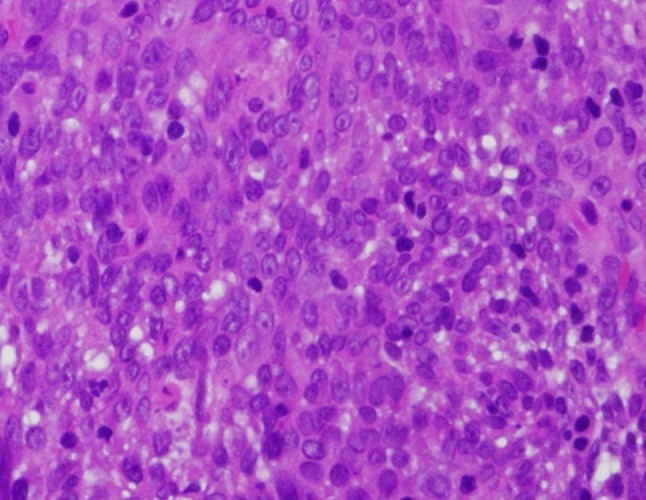

The hematoxylin and eosin stained surgical specimens from the right and left nasal masses as well as the right nasal pharyngeal mass, were each composed of highly cellular nests of syncytial cells clearly demarcated from the surrounding stroma (Fig. 5). The cells demonstrated indistinct cell borders, vesicular nuclei with prominent, centrally-located nucleoli, and amphophilic cytoplasm (Fig. 6). Scattered throughout the lesions were benign mature lymphocytes. Keratin stains were positive and supported the focal histologic impression of squamous differentiation, which is minimal. In situ hybridization for Epstein-Barr virus encoded RNA (EBER) was strongly positive with a nuclear staining pattern (Fig. 7). Given the histologic and ancillary findings, the present case was diagnosed as nasopharyngeal carcinoma, nonkeratinizing, undifferentiated type.

Fig. 5.

A syncytial growth pattern where squamous differentiation is not readily evident by light microscopy

Fig. 6.

Pavemented cellular arrangement with indistinct cellular borders, round to oval nuclei and an inclusion of scant admixed lymphocytes

Fig. 7.

Left: strong, diffuse nuclear reactivity with EBER technique, Right: CK 5/6 highlights neoplastic cells

Discussion

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is rare in most parts of the world, but is more common in southern China, Southeast Asia, and North Africa. Once thought to occur most frequently in Hong Kong and Taiwan where 1 in 40 men develop NPC before the age of 75, NPC is also, interestingly, noted to arise in immigrants from these areas [1]. However, these trends appear to be changing slightly. Parts of Malaysia and Singapore are demonstrating increasingly higher rates than that seen in Hong Kong [6]. The annual incidence in the United States and Europe is approximately 1 per 100,000 of the population and shows a 2:1 male: female prevalence with a peak age of incidence in the sixth decade [2].

Etiologic factors associated with NPC include genetic and environmental factors. Certain human leukocyte antigen types, infection with Epstein-Barr virus, and exposure to nitrosamines and polycyclic hydrocarbons in salt-preserved food have all been associated with the development of NPC. For example, HLA-A2, -B17, and -Bw26 are associated with twice the risk of developing NPC in endemic populations [3]. EBV has been implicated in infecting epithelial cells by inclusion of clonal viral DNA into the host genome which can then result in malignant transformation [2].

The most common site of origin of NPC is the fossa of Rosenmüller, which is located superior and posterior to the torus tubarius, the cartilage that surfaces the eustachian tubes superiorly and posteriorly [2]. Due to proximity of the tumor to the eustachian tubes, ear pain is a frequent presenting symptom. Most patients present at some point with an asymptomatic cervical mass that is frequently found in the apex of the posterior cervical triangle, or in the superior jugular chain of nodes [3].

NPC originates from the nasopharyngeal mucosa and shows evidence of squamous differentiation. The World Health Organization now classifies NPC into three types: keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma, nonkeratinizing carcinoma, and basaloid squamous cell carcinoma [1]. Of the three types, nonkeratinizing carcinoma is by far the most common variant and can be further subclassified as either differentiated or undifferentiated, although this has no effect on treatment or outcome. It has an overall 5-year survival rate of 75% [1]. Basaloid squamous cell carcinoma is extremely rare in the nasopharynx. Keratinizing NPC histologically appears as conventional squamous cell carcinoma and has a poor 5-year survival rate of 20–40%.

In the current case, the patient presented to her initial medical provider with ear pain and was subsequently treated for otitis media. As a result of the vagueness of the presenting symptoms and the difficultly of examination, NPC is frequently misdiagnosed early in its course and is rarely diagnosed before it has spread to the regional lymph nodes, as demonstrated in this case. The most frequent presenting symptom is cervical lymphadenopathy. Blood-stained nasal discharge, unilateral hearing loss, and unilateral nasal obstruction are other presenting symptoms [2].

Cranial nerve involvement, also demonstrated in this case, is seen in approximately 25% of cases [2]. This case presented with left facial numbness and loss of lateral rectus function (impaired abduction) in the left eye. These signs indicate cranial nerve V and VI involvement due to invasion of the skull base.

The histologic differential diagnosis includes oropharyngeal nonkeratinizing carcinoma, lymphoma, high-grade sarcoma, and mucosal malignant melanoma. Oropharyngeal nonkeratinizing carcinoma would test p16 positive and EBER negative when compared to NPC. The work-up for nodal metastatic carcinomas with features of NPC or oropharyngeal nonkeratinizing carcinoma should always include staining for EBER and p16. Occasionally, it is difficult to distinguish nonkeratinizing NPC from a large cell lymphoma. In the mucosa of the nasopharynx and in nodal metastases, the dispersed growth and occasional eosinophilic infiltrate may lead to a misdiagnosis of Hodgkin lymphoma. However, the presence of cohesive cells that are positive for cytokeratin favors the diagnosis of NPC and effectively rules out a lymphoma, which would be positive for leucocyte common antigen (CD45). Mucosal malignant melanoma will be positive for S100 and melanoma markers such as HMB-45 and Melan-A. NPC with cellular spindling can mimic a high-grade sarcoma, but distinction can again be made with cytokeratin stains [1, 2].

The radiographic differential diagnosis would include lymphoma, an aggressive minor salivary gland malignancy, and a primary or secondary sarcoma. CT with contrast and MR with enhancement are the standard imaging modalities, with MR as the preferred imaging method because it provides more information on extension and intra-cranial involvement. NPC typically presents radiographically as a mass centered in the lateral pharyngeal recess of the nasopharynx with deep extension and cervical lymphadenopathy. On CT, it may show destruction of the clival cortex, pterygoid plates, or posterior skull base. Extension to surrounding spaces rules out benign nasopharyngeal lesions. Non-Hodgkin lymphoma will typically diffusely involve the adenoids with no enhancing septa on contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MR. It may be difficult to radiographically distinguish NPC from minor salivary gland malignancies or soft tissue sarcomas. While nodal metastasis is common in NPC, it is rare in minor salivary gland malignancies [4].

Treatment of early stage (T1-2a;N0;M0) NPC is radiotherapy alone. Systemic treatment with cisplain-based chemoradiation is now the standard of care for advanced disease. Adjuvant chemotherapy and neoadjuvant chemotherapy before concomitant chemoradiotherapy are still being investigated. Prognosis depends on the clinical stage at presentation and histologic variant. Prognosis is improved with a younger patient age, lower clinical stage, and female gender [1, 5]. The patient in this case was in clinical stage IV and is being treated with concurrent carboplatin and radiotherapy. The left lateral rectus function has returned and the neck mass is no longer visible.

Acknowledgments

Disclaimer

The opinions and assertions expressed herein are those of the authors and are not to be construed as official or representing the views of the Department of the Navy or the Department of Defense. I certify that all individuals who qualify as authors have been listed; each has participated in the conception and design of this work, the writing of the document, and the approval of the submission of this version; that the document represents valid work; that if we used information derived from another source, we obtained all necessary approvals to use it and made appropriate acknowledgements in the document; and that each takes public responsibility for it. We are military service members. This work was prepared as part of our official duties. Title 17 U.S.C. 105 provides that ‘Copyright protection under this title is not available for any work of the United States Government.’ Title 17 U.S.C. 101 defines a United States Government work as a work prepared by a military service member or employee of the United States Government as part of that person’s official duties.

References

- 1.Barnes L, Everson JW, Reichart P, Sidransky D, editors. World Health Organization classification of tumours. Pathology and genetics of head and neck tumours. Lyon: IARC Press; 2005. pp. 85–97. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jeyakumar A, Brickman TM, Jeyakumar A, Doerr T. Review of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Ear Nose Throat J. 2006; 85(3):168–70, 172–3, 184. [PubMed]

- 3.Thompson L. Update on nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Head Neck Pathol. 2007;1(1):81–86. doi: 10.1007/s12105-007-0012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goh J, Lim K. Imaging of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2009;38(9):809–816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caponigro F, Longo F, Ionna F, Perri F. Treatment approaches to nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a review. Anticancer Drugs. 2010;21(5):471–477. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0b013e328337160e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wei KR, Yu YL, Yang YY, et al. Epidemiological trends of nasopharyngeal carcinoma in China. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2010;11(1):29–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]