Abstract

Transient receptor potential (TRP) cation channel superfamily plays important roles in variety cellular processes including polymodal cellular sensing, cell adhesion, cell polarity, proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis. One of its subfamilies are TRPM channels. mRNA expression of its founding member, TRPM1 (melastatin), correlates with terminal melanocytic differentiation and loss of its expression has been identified as an important diagnostic and prognostic marker for primary cutaneous melanoma. Because TRPM1 gene codes two transcripts: TRPM1 channel protein in its exons, and miR-211 in one of its introns, we propose a dual role for TRPM1 gene where the loss of TRPM1 channel protein is an excellent marker of melanoma aggressiveness, while the expression of miR-211 is linked to the tumor suppressor function of TRPM1. In addition, three other members of this subfamily, TRPM 2, 7 and 8 are implicated in regulation of melanocytic behavior. TRPM2 is capable of inducing melanoma apoptosis and necrosis. TRPM7 can be a protector and detoxifier in both melanocytes and melanoma cells. TRPM8 can mediate agonist-induced melanoma cell death. Therefore, we propose that TRPM1, TRPM2, TRPM7, and TRPM8 play crucial roles in melanocyte physiology and melanoma oncology, and are excellent diagnostic markers and theraputic targets.

Keywords: Transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily M, melanocytes, melanoma, melanogenesis, oncogenesis

1 Introduction

Since the discovery of melanoma supressor gene TRPM1 in 1998 (1), its molecular pathway of tumor suppressor function had evaded attention until recently. In addition, more members of the TRP superfamily have been found regulating normal and malignant melanocyte behavior, especially some members of the TRPM subfamily. This viewpoint proposes that TRPM subfamily plays a crucial role in regulation of melanocytic homeostasis and oncogenesis, defining their diagnostic and therapeutic utilities.

1.1 TRP superfamily

Ions cannot freely diffuse through biological membrane due to their lipid insolubility; they flow across the membrane through ion channels. By gating of the ion channels, external and internal signals regulate important cellular functions. The gating of channels may be direct by voltage or ligand binding, or internal, by molecular signal transduction events. Transient receptor potential (TRP) cation channels superfamily was discovered by studying of a Drosophila mutant with defective response to light (2). This mutant fly has a transient, rather than a sustained response to prolonged illumination, hence designated as “transient receptor potential (TRP)” (3). The responsible protein in the mutant fly is a Ca2+ channel, which generates the voltage light response. Other members of this superfamily, both in vertebrates and invertebrates, were discovered and classified on the basis of homology of amino acid sequence, mainly in the transmembrane domain regions. Based on amino acid sequence homology, the TRP superfamily is classified into seven subfamilies: TRPC, TRPM, TRPV, TRPA, TRPP, TRPML, and TRPN (4, 5). Except for TRPN, all of the subfamilies are conserved through evolution and exist in diverse animal species ranging from mammals and fish to fruit flies and nematodes. Structurally, between N- and C-terminals, they span the membrane six times and have a hydrophobic pore loop between tansmembrane regions 5 and 6, placing them to be a close relative of the superfamily of voltage-gated channel proteins (6–8). However, in the contrast to the voltage-gated channels, their fourth transmembrane segment lacks the complete set of positively charged residues necessary for a voltage sensor (9). In addition, TRP channels are activated by a wide range of chemical and mechanical stimuli defining them as the polymodal molecular sensors of the cell, such as temperature, touch, osmolarity, pheromones, taste and other stimuli (10, 11). Besides their sensory function, they also participate in regulation of cell adhesion, cell polarity, proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis (12–14).

1.2 TRPM subfamily

TRPM subfamily of the TRP superfamily is structurally and functionally diverse (15, 16). TRPMs are non-selective cation channels involved in processes ranging from detection of cold, taste, osmolarity, redox state and pH to control of Mg2+ homeostasis and cell proliferation or death (17, 18). The TRPM subfamily has been conserved through evolution and exists in invertebrates and vertebrates. There are eight members of the TRPM subfamily in mammals, which are numbered according to the order of their discovery, TRPM1-TRPM8. TRPM subfamily is phylogenetically divided into four groups: TRPM1/3, TRPM6/7, TRPM4/5 and TRPM2/8 (15) (supplemental Fig. 1). This subfamily was originally designated as long TRP (LTRPC), because of the unusually long N-terminal. The length of the polypeptides of this subfamily varies considerably because of a large diversity at the C-terminal. In addition to the common structure shared with all TRP channels, TRPMs have a common large TRPM homology domain in the N-terminal, and a TRP box in the C-terminal (19). Like other members of the TRP superfamily, functional TRPM channels can either be homo- or hetero-tetramers(20–22), and the C-terminal coiled-coil domain is important for assembly and tetrameric formation (23). An exceptional structural feature of three TRPM members is the presence of functional enzymes in their C-termini: TRPM2 contains a functional NUDT9 homology domain exhibiting ADP-ribose pyrophosphatase activity (24, 25), whereas both TRPM6 and TRPM7 contain a functional COOH-terminal alpha-kinase (an atypical serine/threonine kinase) (26–28).

1.3 Melanocytes and melanoma

Remarkably, four out of eight TRPM members, i.e. TRPM1, TRPM2, TRPM7, and TRPM8, are involved in regulation of melanocyte physiology and melanoma development (29–35). Melanocytes are derived from neural crest and in mature organisms, they function as melanin-synthesizing dendritic cells located within the basal layer of the epidermis, hair bulb, and outer root sheath of hair follicles. At these sites, they not only define skin and hair pigmentation, but they also regulate various skin functions (36–38). Melanogenesis represents a multistep process initiated by enzymatic activity of tyrosinase and ending with the transfer of melanosomes to epidermal keratinocytes and to hair cortex keratinocytes (36, 38, 39). Melanoma, derived from melanocytes, is an epidemic tumor whose death rate continues to rise in the United States (40). In 2012, estimated new cases and deaths from melanoma in the United States are 76,280 and 9,180, respectively(41). The exact molecular mechanisms that lead to melanoma are complex and poorly understood, involving both mutagenic and epigenetic events (42). This viewpoint hypothesizes that TRPMs are main regulators of normal and malignant melanocyte behavior with special focus on unique properties of TRMP1.

2 TRPM subfamily in melanocytes and melanoma

2.1 TRPM1

TRPM1 was originally identified as a melanoma metastasis suppressor gene based on its decreased expression in metastatic mouse melanoma cell lines (1). Duncan and colleagues found that TRPM1 is expressed at high levels in poorly metastatic variants of B16-F1 melanoma cell line and at much reduced levels in highly metastatic B16-F10 melanoma cell line (1). Subsequently, they showed that TRPM1 mRNA, which is ubiquitously expressed in normal human epidermal melanocytes and benign melanocytic nevi; is steadily lost during progression of the primary cutaneous, vertical growth phase melanomas; and is partially or completely lost in metastatic melanoma (1). Moreover, in primary melanoma, the loss of TRPM1 mRNA expression correlated with melanoma tumor thickness. This association between TRPM1 expression and melanoma invasiveness and metastasis was confirmed by Deeds and colleagues (43). They showed ubiquitous melanocytic expression of TRPM1 mRNA in melanocytic nevi, focal TRPM1 mRNA loss in some primary melanoma, and focal or complete loss in all of the melanoma metastases by radioactive in situ hybridization (RISH) methods for melastatin (TRPM1) mRNA. In addition, they found that even though all of the benign nevi expressed TRPM1, some of them showed a gradient of reduced expression with increasing dermal depth (43). This phenotype correlates with so called “melanocyte maturation”, which is characterized by a morphologic progression from epithelioid “type A” melanocytes in the papillary dermis to lymphocyte-like “type B” cells in the mid-dermis to schwannian “type C” cells in the deep dermis, reflecting phenotypic change from melanin producing to non-melanin producing melanocytes (32). They classified the TRPM1 loss in primary melanomas into 3 patterns: focal nodular loss (most common), focal scattered loss, and complete loss. These patterns of TRPM1 mRNA expression suggest diagnostic and prognostic value. Diagnostically, regional or complete loss of mRNA expression differentiates nodular melanomas from Spitz nevi, which show scattered, diffuse loss TRPM1 mRNA (44). Prognostically, loss of TRPM1 mRNA expression by RISH is an independent prognostic factor for disease free survival in addition to traditional factors such as tumor thickness, mitotic rate, ulceration, regression, and tumor-in ltrating lymphocytes (45). As an alternative to the use of radioactive agents, which cannot be supported in most pathology laboratories, a non-radioactive chromogenic in situ hybridization (CISH) method to detect and measure TRPM1 mRNA was developed (32, 33, 46). CISH evaluation of TRPM1 mRNA has reproduced and expanded on the results published for RISH. Specifically, TRPM1 mRNA is variablly expressed by normal melanocytes based on anatomic site, patient age, extent of sun-damage and proximity to melanocytic tumors (Figure 1). In addtion, TRPM1 is strongly expressed by pigmented melanocytes of the follicular bulb (Figure 1). In compound and intradermal melanocytic nevi showing congential features, dermal melanocytes exhibit a gradient of progressive loss of expression based on melanocyte (maturation) phenotype (Figure 1) (32). For patients with American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) pathologically staged Stage I and II melanomas, progressive loss of TRPM1 mRNA significantly correlated with increasing tumor thickness (Figure 2) the presence of microsatellites (in-transit metastases) (33), and independently predicted for shorter disease free survival (33). In another study by Carlson et al (46), down-regulation of TRPM1 mRNA in primary cutaneous melanomas was also found to be an independent prognostic factor for disease free survival, which correlated with advanced AJCC stage, increasing tumor mitotic rate, and absent or non-brisk tumor infiltrating host response. However, whether TRPM1 is an independent prognostic factor for overall survival in melanoma patients is still an open question. Based on the previous studies and the recent clarified molecular mechanism of tumor suppressor function (see below), we hypothesize that loss of TRPM1 expression is crucial for lethal melanoma phenotype and will be recognized as an independent prognostic factor for overall survival. Further studies with long follow-up time should clarify this challenging question.

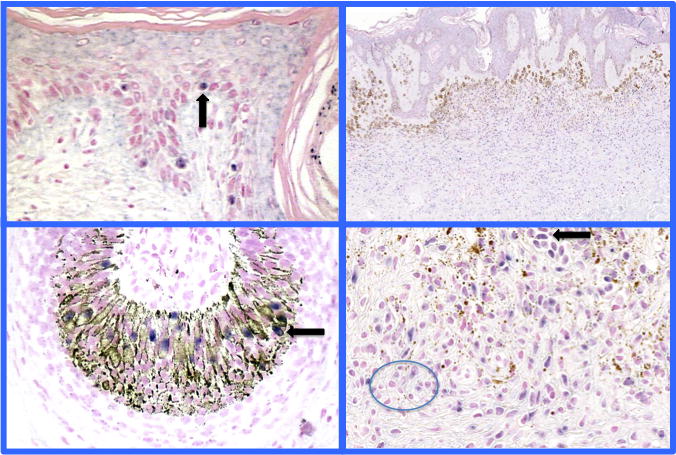

Figure 1.

Chromogenic in situ hybridization study for TRPM1 (MSLN) mRNA expression of normal melanocytes and melanocytic nevi. TRPM1 mRNA expression strongly correlates with a fully differentiated melanocyte. TRPM1 mRNA expression in normal melanocytes of the epidermis and follicular bulb (left sided panels). (Black arrows point to examples of TRPM1 mRNA expressing melanocytes). Right panels shows gradient MLSN/TRPM1 expression in an intradermal congenital melanocytic nevus- type A cells found in the upper dermis show strong expression (black arrow), type B melanocytes intermediate expression, and type C low/no expression of TRPM1 in the deep reticular dermis (circle surrounds type C melanocytes with no or focal TRPM1 mRNA nuclear expression (32). For technical details see (32).

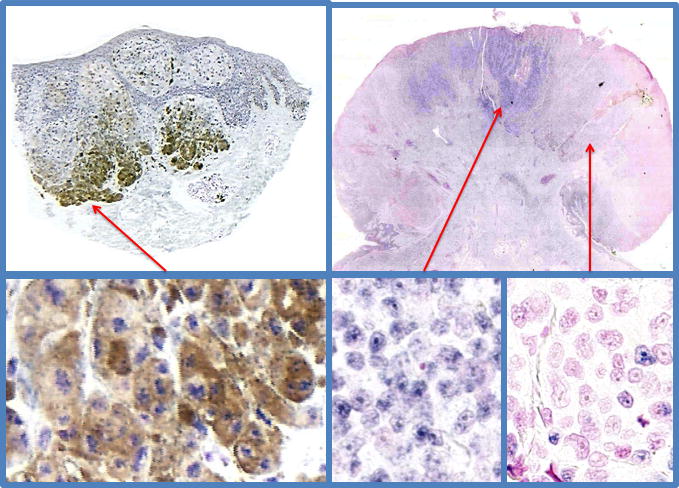

Figure 2.

Chromogenic in situ hybirdization study for TRPM1 (MSLN) mRNA expression in primary melanoma demonstrates an inverse correlations with increasing depth of invasion, disease free survival, and overall survival (33, 46)(unpublished data Carlson). Left side panels show a superficial spreading melanoma, Breslow’s thickness 1.05 mm, showing strong nuclear expression TRPM1 mRNA in the background heavy pigmentation of melanoma cells. This patient is disease free after 2 years follow up. The right side panels show a nodular, ulcerated melanoma, Breslow’s thickness 7.2mm, showing heterogeneous expression of TRPM1 mRNA. Regions of the melanoma show full, partial or complete loss of TRPM1 mRNA. This patient died of metastatic disease after 3.5 years of follow up.

By RISH and CISH, loss of TRPM1 is a marker of the aggressiveness of melanoma. Thus, the regulation of gene expression of TRPM1 has been a subject of many investigations. Based on sequence pattern analysis, Hunter and colleagues suggested that the promoter region of TRPM1 contains four microphthalmia transcription factor (MITF) binding sites (47). Two groups independently demonstrateded that MITF directly regulates expression of TRPM1 in vitro (34, 48). Thereafter, Lu and colleagues showed that TRPM1 mRNA expression significantly and strongly correlate with MITF and tyrosinase expression in vivo, supporting the in vitro finding that MITF regulates TRPM1 expression. In addition, based on correlation with multiple melanin related proteins, TRPM1 mRNA expression was found to be a marker of differentiated, melanin producing melanocytes (32). Moreover, they demonstrated that TRPM1 mRNA expression appears to be dynamic, labeling most but not all intraepidermal melanocytes, with variable expression ostensibly related to local environmental factors. For instance, while the overall population of melanocytes was similar from region to region, a decrease in TRPM1 mRNA expressing melanocytes was found in older individuals, in sun damaged skin, and in regenerative epidermis overlying a scar. This phenomenon implicates an expansion of less differentiated intraepidermal melanocytes, so called melanoblasts (32). On the other hand, Fang and colleagues (49) showed that multiple short transcripts of TRPM1 are present in melanocytes and pigmented metastatic melanoma cell lines while the full-length 5.4-kb mRNA is detectable only in melanocytes. Interestingly, treatment of pigmented melanoma cells with the differentiation-inducing agent, HMBA, resulted in up-regulation of the 5.4-kb TRPM1 mRNA as well as short RNAs. The existence of multiple forms of TRPM1 has been verified by other studies (34, 50, 51). Therefore, we speculate that alternative splicing of TRMP1 can affect an interaction between melanocytes and environment, and affect the behavior of melanoma. The mechanism could in general be similar to that described for CRF receptors, where alternative splicing lead to diverse phenotypic effects through multiple pathways (52–54). The answer to these questions requires functional assignement for each isoform and defining their role in regulation of a main isoform as it was proposed for CRF1.

Accompanied by the genetic studies, the physiological functions of TRPM1 have been gradually revealed. Thus, TRPM1 mediates Ca2+ entry in transfected HEK293 cells (50). Consistent with this finding, knockdown of TRPM1 results in reduced intracellular Ca2+ content and decreased Ca2+ uptake in cultured human melanocytes from neonatal foreskins, suggesting a role for TRPM1 in Ca2+ homeostasis in melanocytes (31). TRPM1 expression is also regulated by ultraviolet B radiation and its expression is related to melanocyte proliferation and differentiation in vitro. Consistent with its function in calcium homeostasis, TRPM1 is found to mediate an endogenous current that can be abrogated by knockdown of TRPM1 gene (51).

In addition to calcium homeostasis, there are several studies pointing out that TRPM1 might regulate melanogenesis. For example, TRPM1 expression decreased in unpigmented skin of the Appaloosa horse (55). Also TRPM1 knockdown resulted in a decrease in intracellular melanin pigment (51). Moreover, human primary melanocytes from light skin had an 80% reduction in the abundance of TRPM1 mRNA compared to the melanocytes from dark skin (51). Interestingly, TRPM1 regulatesd melanogenesis without co-localizing with melanosomes. Instead, TRPM1 is located in highly dynamic intracellular vesicular structures found in melanoma cells (51). TRPM1 knockdown resulted in a decrease in tyrosinase activity and intracellular melanin pigment (31).

The tumor suppressor function of TRPM1 gene has been shown recently, with miR-211 being down-regulated in metastatic melanoma cell line WM1552C (56). Similar to TRPM1 protein, miR-211 is also highly expressed in nevi compared to melanoma. Furthermore, the gene encoding miR-211 is located within the sixth intron of the TRPM1 gene, and both miR-211 and TRPM1 channel protein are regulated by MITF (56). However, different from TRPM1 protein, miR-211 has a direct target, KCNMA1, which is often associated with both cell proliferation and cell migration/invasion in various cancers (56). Independently, Levy and colleagues found that both miR-211 and TRPM1 protein are coded by the same gene, TRPM1 gene, share the same promoter, and are co-regulated by MITF (57). In addition, miR-211 was reduced in almost all melanomas compared to melanocytes confirming its tumor suppressor function (57). By over-expression and knockdown of either TRPM1 channel protein or miR-211, they demonstrated that miR-211 rather than TRPM1 channel protein modified melanoma invasiveness. They also identified that miR-211 regulated insulin-like growth factor 2 (IGF2R), transforming growth factor beta receptor II (TGFBR2), and nuclear factor of activated T-cells 5 (NFAT5) signal transduction pathways to assume a tumor suppressive function. It was further confirmed that miR-211 expression is greatly decreased in melanoma cells compared to melanocytes (58). In addition, they found another miR-211 target, BRN2, which mediates the de-differentiated, invasive phenotype of melanoma. The data above support the hypothesis that TRPM1 gene regulates melanocyte/melanoma behavior via generation of two transcripts including TRPM1 protein in its exons, and miR-211 in the intron (Figure 3). This indicates dual activity for this gene where loss of TRPM1 protein is an excellent marker of melanoma aggressiveness, with expression of miR-211 being linked to the tumor suppressor function (Figure 3). Therefore, our working hypothesis is that different RNA transcription format (i.e. TRPM1 mRNA and/or miR-211) of the TRPM1 gene decides on the melanocyte phenotype and melanoma behavior. Clarifying this phenomenon requires future in vitro studies with targeted disruption of TRMP1 expression format and clinicopathologic correlation using large clinical material.

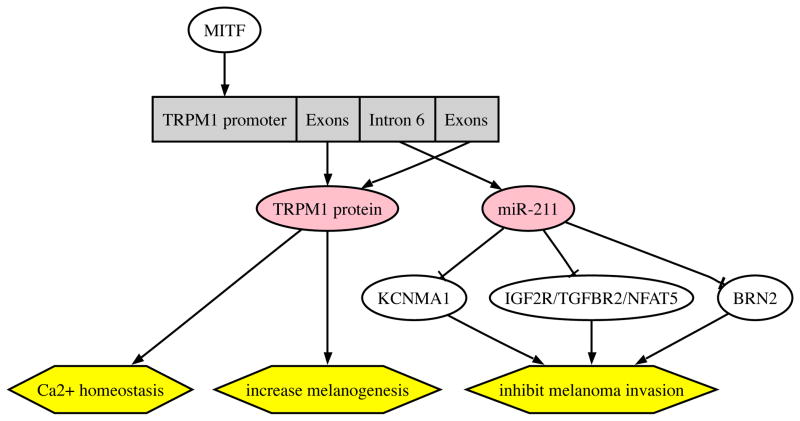

Figure 3.

TRPM1 gene encodes both TRPM1 mRNA and miR-211: proposed biological and clinical implications. TRPM1 channel protein is coded by the exons of the gene and miR-211 is coded by the sixth intron. They share the same promoter and are co-regulated by MITF(56, 57). The proposed sequence of phenotypic regulation is depicted in the graph. Briefly, TRPM1 protein regulates melanogenesis and Ca2+ homeostasis, while miR-211 acts as a tumor suppressor gene activating multiple pathways as shown. BRN2: POU domain-containing transcription factor Brn2; IGF2R: insulin-like growth factor 2; KCNMA1: potassium large conductance calcium-activated channel, subfamily M, alpha member 1; MITF: microphthalmia-associated transcription factor; NFAT5: nuclear factor of activated T-cells 5; TGFBR2: transforming growth factor, beta receptor II; TRPM1: transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily M (melastatin)

2.2 TRPM2

TRPM2 is a channel protein with enzyme activity that is widely expressed in mammalian tissues. TRPM2 is activated by intracellular ADP-ribose (ADPR), heat, and hydrogen peroxide (59, 60). TRPM2 contains a functional NUDT9 homology domain, exhibiting ADPR pyrophophatase activity (24, 25). Acting as a redox sensor for the cell, TRPM2 is capable of conferring cell death upon oxidative stress (61). In melanocytes and melanoma cell lines, TRPM2 locus also transcribes TRPM2-AS and TRPM2-TE, which is in addition to producing full length TRPM2 transcript. TRPM2-AS is a natural antisense transcript (62). TRPM2-TE is a truncated transcript functioning as a dominant-negative form of TRPM2. TRPM2-AS and TRPM2-TE share a common promoter region, which is a CpG island located in the TRPM2 gene. Quantitative PCR experiments confirmed that TRPM2-AS and TRPM2-TE transcripts were up-regulated in melanoma, and their activation correlated with the methylation status of the shared CpG island (62). Functional knock-out of TRPM2-TE or over-expression of wild-type TRPM2 increases melanoma susceptibility to apoptosis and necrosis (62). Therefore restoration of normal TRPM2 activity in melanoma cells is a viable future therapeutic target.

2.3 TRPM7

TRPM7 is another channel protein with enzyme activity in the TRPM subfamily (15, 16). It is ubiquitously expressed and involved in the regulation of cellular magnesium homeostasis (63). The C-terminal atypical protein kinase domain has homologies with the elongation factor 2 kinase, and heart, lymphocyte and muscle alpha kinases. Studies on the cutaneous melanophores of zebrafish with TRPM7 mutant have shown that TRPM7 can prevent accumulation of cytotoxic intermediates of melanin synthesis, protecting melanocytes from the death (64). Most mutant genes of melanophore-deficient zebrafish have orthologous genes disrupted in mouse white-spotting mutants. This implies that the mechanisms regulating melanocyte behavior are conserved between fish and mammals (36, 65)}. Therefore, we believe that TRPM7 can serve as an excellent therapeutic target for restoration of protective and detoxifying properties in normal melanocytes or as marker of deregulated metabolic activity in melanoma cells.

2.4 TRPM8

TRPM8 was initially cloned as a novel prostate-specific gene by screening a prostate cDNA library (66). Later, it was shown that TRPM8 has a major role in the cold sensation in trigeminal ganglion and dorsal root ganglion neurons (67, 68). In TRPM8-expressing cells, application of menthol, icilin or other cooling agents induces TRPM8 currents, which are comparable to activation of TRPM8 by cold temperature (69, 70). TRPM8 channels are expressed in human melanocytes and melanoma cells and their activation produces sustained Ca2+ influx (71). It has been shown that TRPM8 can decrease pigment producing activity of the melanocytes in vivo and in vitro by decreasing the tyrosinase and tyrosinase-related protein (TRP)-1 expression levels (30). Importantly, the viability of melanoma cells decreased in the dose dependent manner after treatment with menthol, and this effect was related to the activation of TRPM8 (71). Therefore, we propose to target TRPM8 with natural products such as menthol or other ligands as adjuvant in melanoma therapy or as means of treating pathological melanosis.

3. Conclusions and future directions

Based on embryonal origin of melanocytes and functions of TRPM channels as polymodal molecular sensors, it is not surprising that four of the eight members of the TRPM subfamily are involved in the regulation melanocyte behavior (see supplemental table 1). Of these members, TRPM1 is being established as a marker of melanoma aggressiveness whose expression is inversely related to invasiveness and metastasis. We hypothesizes that alternative splicing of TRPM1 and regulated expression of miR-211 are involved in those processes. Clinically relevant implications in pigmentation and melanoma derive from TRPM2 capability of inducing melanoma apoptosis and necrosis, protective and detoxifying functions of TRPM7 in normal and malignant melanocytes, and of TRPM8 involvement in inhibition of pigmentation and melanoma proliferation. Thus, TRPM subfamily represents an excellent pharmacological target for treatment of pigmentary disorders and/or melanoma. Furthermore, they are attractive markers of melanoma progression

Supplementary Material

Phylogenetic tree of TRPM subfamily. We retrieved the amino acid sequences of members of TRPM subfamily from Genbank. Multiple sequence alignment and phylogenetic analysis were done using ClustalW. Four species have been selected. hs: Homo sapiens (human); mm: Mus musculus (mouse); ec: Equus caballus (horse); dr: Danio rerio (zebrafish).

Acknowledgments

Writing of the paper was in part supported by by grants R01AR052190, and 1R01AR056666-01A2 from the NIH/NAIMS to AS

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest to declare for all the authors.

References

- 1.Duncan LM, Deeds J, Hunter J, et al. Down-regulation of the novel gene melastatin correlates with potential for melanoma metastasis. Cancer Res. 1998;58:1515–1520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cosens DJ, Manning A. Abnormal electroretinogram from a Drosophila mutant. Nature. 1969;224:285–287. doi: 10.1038/224285a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Minke B, Wu C, Pak WL. Induction of photoreceptor voltage noise in the dark in Drosophila mutant. Nature. 1975;258:84–87. doi: 10.1038/258084a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Montell C. Physiology, phylogeny, and functions of the TRP superfamily of cation channels. Sci STKE. 2001;2001:re1. doi: 10.1126/stke.2001.90.re1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Montell C. The TRP superfamily of cation channels. Sci STKE. 2005;2005:re3. doi: 10.1126/stke.2722005re3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clapham DE, Runnels LW, Strubing C. The TRP ion channel family. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:387–396. doi: 10.1038/35077544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Minke B, Cook B. TRP channel proteins and signal transduction. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:429–472. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00001.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nilius B, Owsianik G, Voets T, Peters JA. Transient receptor potential cation channels in disease. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:165–217. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00021.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Catterall WA. From ionic currents to molecular mechanisms: the structure and function of voltage-gated sodium channels. Neuron. 2000;26:13–25. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81133-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clapham DE. TRP channels as cellular sensors. Nature. 2003;426:517–524. doi: 10.1038/nature02196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Venkatachalam K, Montell C. TRP channels. Annu Rev Biochem. 2007;76:387–417. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dadon D, Minke B. Cellular functions of transient receptor potential channels. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2010;42:1430–1445. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2010.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moran MM, McAlexander MA, Bíró T, Szallasi A. Transient receptor potential channels as therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10:601–620. doi: 10.1038/nrd3456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosenbaum EE, Brehm KS, Vasiljevic E, Liu CH, Hardie RC, Colley NJ. XPORT-Dependent Transport of TRP and Rhodopsin. Neuron. 2011;72:602–615. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harteneck C. Function and pharmacology of TRPM cation channels. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2005;371:307–314. doi: 10.1007/s00210-005-1034-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zholos A. Pharmacology of transient receptor potential melastatin channels in the vasculature. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;159:1559–1571. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00649.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fleig A, Penner R. The TRPM ion channel subfamily: molecular, biophysical and functional features. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2004;25:633–639. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kraft R, Harteneck C. The mammalian melastatin-related transient receptor potential cation channels: an overview. Pflugers Arch. 2005;451:204–211. doi: 10.1007/s00424-005-1428-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Birnbaumer L, Yildirim E, Abramowitz J. A comparison of the genes coding for canonical TRP channels and their M, V and P relatives. Cell Calcium. 2003;33:419–432. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(03)00068-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hofmann T, Schaefer M, Schultz G, Gudermann T. Subunit composition of mammalian transient receptor potential channels in living cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:7461–7466. doi: 10.1073/pnas.102596199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li M, Jiang J, Yue L. Functional characterization of homo- and heteromeric channel kinases TRPM6 and TRPM7. J Gen Physiol. 2006;127:525–537. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200609502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strubing C, Krapivinsky G, Krapivinsky L, Clapham DE. Formation of novel TRPC channels by complex subunit interactions in embryonic brain. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:39014–39019. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306705200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsuruda PR, Julius D, Minor DL., Jr Coiled coils direct assembly of a cold-activated TRP channel. Neuron. 2006;51:201–212. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cahalan MD. Cell biology. Channels as enzymes Nature. 2001;411:542–543. doi: 10.1038/35079231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perraud AL, Fleig A, Dunn CA, et al. ADP-ribose gating of the calcium-permeable LTRPC2 channel revealed by Nudix motif homology. Nature. 2001;411:595–599. doi: 10.1038/35079100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Runnels LW, Yue L, Clapham DE. TRP-PLIK, a bifunctional protein with kinase and ion channel activities. Science. 2001;291:1043–1047. doi: 10.1126/science.1058519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Drennan D, Ryazanov AG. Alpha-kinases: analysis of the family and comparison with conventional protein kinases. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2004;85:1–32. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6107(03)00060-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chubanov V, Mederos y Schnitzler M, Waring J, Plank A, Gudermann T. Emerging roles of TRPM6/TRPM7 channel kinase signal transduction complexes. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2005;371:334–341. doi: 10.1007/s00210-005-1056-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Slominski A. Cooling skin cancer: menthol inhibits melanoma growth. Focus on “TRPM8 activation suppresses cellular viability in human melanoma”. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;295:C293–295. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00312.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Botchkarev N, Shander D. Organization W I P. Reduction of hair growth. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Devi S, Kedlaya R, Maddodi N, et al. Calcium homeostasis in human melanocytes: role of transient receptor potential melastatin 1 (TRPM1) and its regulation by ultraviolet light. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2009;297:C679–687. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00092.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lu S, Slominski A, Yang S-E, Sheehan C, Ross J, Carlson JA. The correlation of TRPM1 (Melastatin) mRNA expression with microphthalmia-associated transcription factor (MITF) and other melanogenesis-related proteins in normal and pathological skin, hair follicles and melanocytic nevi. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37 (Suppl 1):26–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2010.01504.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hammock L, Cohen C, Carlson G, et al. Chromogenic in situ hybridization analysis of melastatin mRNA expression in melanomas from American Joint Committee on Cancer stage I and II patients with recurrent melanoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:599–607. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2006.00501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhiqi S, Soltani MH, Bhat KMR, et al. Human melastatin 1 (TRPM1) is regulated by MITF and produces multiple polypeptide isoforms in melanocytes and melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2004;14:509–516. doi: 10.1097/00008390-200412000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.von Thaler AK, Kamenisch Y, Berneburg M. The role of ultraviolet radiation in melanomagenesis. Exp Dermatol. 19:81–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2009.01025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Slominski A, Tobin DJ, Shibahara S, Wortsman J. Melanin pigmentation in mammalian skin and its hormonal regulation. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:1155–1228. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00044.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Slominski A, Wortsman J. Neuroendocrinology of the skin. Endocr Rev. 2000;21:457–487. doi: 10.1210/edrv.21.5.0410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Slominski A, Wortsman J, Plonka PM, Schallreuter KU, Paus R, Tobin DJ. Hair follicle pigmentation. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;124:13–21. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.23528.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vachtenheim J, Borovansky J. “Transcription physiology” of pigment formation in melanocytes: central role of MITF. Exp Dermatol. 19:617–627. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2009.01053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jemal A, Saraiya M, Patel P, et al. Recent trends in cutaneous melanoma incidence and death rates in the United States, 1992–2006. J Am Acad Dermatol. 65:S17–25. e11–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Melanoma home page. National Cancer Institute; http://www.cancer.gov/ [Google Scholar]

- 42.Whiteman DC, Pavan WJ, Bastian BC. The melanomas: a synthesis of epidemiological, clinical, histopathological, genetic, and biological aspects, supporting distinct subtypes, causal pathways, and cells of origin. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 24:879–897. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2011.00880.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Deeds J, Cronin F, Duncan LM. Patterns of melastatin mRNA expression in melanocytic tumors. Hum Pathol. 2000;31:1346–1356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Erickson LA, Letts GA, Shah SM, Shackelton JB, Duncan LM. TRPM1 (Melastatin-1/MLSN1) mRNA expression in Spitz nevi and nodular melanomas. Mod Pathol. 2009;22:969–976. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2009.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Duncan LM, Deeds J, Cronin FE, et al. Melastatin expression and prognosis in cutaneous malignant melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:568–576. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.2.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carlson JA, Ross JS, Slominski A, et al. Molecular diagnostics in melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:743–775. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.08.034. quiz 775–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hunter JJ, Shao J, Smutko JS, et al. Chromosomal localization and genomic characterization of the mouse melastatin gene (Mlsn1) Genomics. 1998;54:116–123. doi: 10.1006/geno.1998.5549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miller AJ, Du J, Rowan S, Hershey CL, Widlund HR, Fisher DE. Transcriptional regulation of the melanoma prognostic marker melastatin (TRPM1) by MITF in melanocytes and melanoma. Cancer Res. 2004;64:509–516. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-2440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fang D, Setaluri V. Expression and Up-regulation of alternatively spliced transcripts of melastatin, a melanoma metastasis-related gene, in human melanoma cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;279:53–61. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xu XZ, Moebius F, Gill DL, Montell C. Regulation of melastatin, a TRP-related protein, through interaction with a cytoplasmic isoform. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:10692–10697. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191360198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Oancea E, Vriens J, Brauchi S, Jun J, Splawski I, Clapham DE. TRPM1 forms ion channels associated with melanin content in melanocytes. Sci Signal. 2009;2:ra21. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Slominski A, Zbytek B, Zmijewski M, et al. Corticotropin releasing hormone and the skin. Front Biosci. 2006;11:2230–2248. doi: 10.2741/1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pisarchik A, Slominski AT. Alternative splicing of CRH-R1 receptors in human and mouse skin: identification of new variants and their differential expression. FASEB J. 2001;15:2754–2756. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0487fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zmijewski MA, Slominski AT. Emerging role of alternative splicing of CRF1 receptor in CRF signaling. Acta Biochim Pol. 2010;57:1–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bellone RR, Brooks SA, Sandmeyer L, et al. Differential gene expression of TRPM1, the potential cause of congenital stationary night blindness and coat spotting patterns (LP) in the Appaloosa horse (Equus caballus) Genetics. 2008;179:1861–1870. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.088807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mazar J, DeYoung K, Khaitan D, et al. The regulation of miRNA-211 expression and its role in melanoma cell invasiveness. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13779. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Levy C, Khaled M, Iliopoulos D, et al. Intronic miR-211 assumes the tumor suppressive function of its host gene in melanoma. Mol Cell. 2010;40:841–849. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Boyle GM, Woods SL, Bonazzi VF, et al. Melanoma cell invasiveness is regulated by miR-211 suppression of the BRN2 transcription factor. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2011;24:525–537. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2011.00849.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McHugh D, Flemming R, Xu SZ, Perraud AL, Beech DJ. Critical intracellular Ca2+ dependence of transient receptor potential melastatin 2 (TRPM2) cation channel activation. JB iol Chem. 2003;278:11002–11006. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210810200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wehage E, Eisfeld J, Heiner I, Jungling E, Zitt C, Luckhoff A. Activation of the cation channel long transient receptor potential channel 2 (LTRPC2) by hydrogen peroxide. A splice variant reveals a mode of activation independent of ADP-ribose. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:23150–23156. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112096200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nazroğlu M. TRPM2 cation channels, oxidative stress and neurological diseases: where are we now? Neurochem Res. 2011;36:355–366. doi: 10.1007/s11064-010-0347-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Orfanelli U, Wenke A-K, Doglioni C, Russo V, Bosserhoff AK, Lavorgna G. Identification of novel sense and antisense transcription at the TRPM2 locus in cancer. Cell Res. 2008;18:1128–1140. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yogi A, Callera GE, Antunes TT, Tostes RC, Touyz RM. Transient receptor potential melastatin 7 (TRPM7) cation channels, magnesium and the vascular system in hypertension. Circ J. 2011;75:237–245. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-10-1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.McNeill MS, Paulsen J, Bonde G, Burnight E, Hsu M-Y, Cornell RA. Cell death of melanophores in zebrafish trpm7 mutant embryos depends on melanin synthesis. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:2020–2030. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Becker JC, Houben R, Schrama D, Voigt H, Ugurel S, Reisfeld RA. Mouse models for melanoma: a personal perspective. Exp Dermatol. 19:157–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2009.00986.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tsavaler L, Shapero MH, Morkowski S, Laus R. Trp-p8, a novel prostate-specific gene, is up-regulated in prostate cancer and other malignancies and shares high homology with transient receptor potential calcium channel proteins. Cancer Res. 2001;61:3760–3769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.McKemy DD, Neuhausser WM, Julius D. Identification of a cold receptor reveals a general role for TRP channels in thermosensation. Nature. 2002;416:52–58. doi: 10.1038/nature719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Peier AM, Moqrich A, Hergarden AC, et al. A TRP channel that senses cold stimuli and menthol. Cell. 2002;108:705–715. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00652-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Liu Y, Qin N. TRPM8 in health and disease: cold sensing and beyond. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2011;704:185–208. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-0265-3_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Denda M, Tsutsumi M, Denda S. Topical application of TRPM8 agonists accelerates skin permeability barrier recovery and reduces epidermal proliferation induced by barrier insult: role of cold-sensitive TRP receptors in epidermal permeability barrier homoeostasis. Exp Dermatol. 19:791–795. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2010.01154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yamamura H, Ugawa S, Ueda T, Morita A, Shimada S. TRPM8 activation suppresses cellular viability in human melanoma. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;295:C296–301. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00499.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Phylogenetic tree of TRPM subfamily. We retrieved the amino acid sequences of members of TRPM subfamily from Genbank. Multiple sequence alignment and phylogenetic analysis were done using ClustalW. Four species have been selected. hs: Homo sapiens (human); mm: Mus musculus (mouse); ec: Equus caballus (horse); dr: Danio rerio (zebrafish).