Abstract

Objective

To test the reliability, validity, acceptability, and practicality of short message service (SMS) messaging for collection of research data.

Materials and methods

The studies were carried out in a cohort of recently delivered women in Tayside, Scotland, UK, who were asked about their current infant feeding method and future feeding plans. Reliability was assessed by comparison of their responses to two SMS messages sent 1 day apart. Validity was assessed by comparison of their responses to text questions and the same question administered by phone 1 day later, by comparison with the same data collected from other sources, and by correlation with other related measures. Acceptability was evaluated using quantitative and qualitative questions, and practicality by analysis of a researcher log.

Results

Reliability of the factual SMS message gave perfect agreement. Reliabilities for the numerical question were reasonable, with κ between 0.76 (95% CI 0.56 to 0.96) and 0.80 (95% CI 0.59 to 1.00). Validity for data compared with that collected by phone within 24 h (κ =0.92 (95% CI 0.84 to 1.00)) and with health visitor data (κ =0.85 (95% CI 0.73 to 0.97)) was excellent. Correlation validity between the text responses and other related demographic and clinical measures was as expected. Participants found the method a convenient and acceptable way of providing data. For researchers, SMS text messaging provided an easy and functional method of gathering a large volume of data.

Conclusion

In this sample and for these questions, SMS was a reliable and valid method for capturing research data.

Keywords: Cellular phone, SMS text messaging, reproducibility of results, data collection, method acceptability, midwifery, feeding your baby study, psychology

Background and significance

Short message service (SMS) is a promising tool for gathering data for research and clinical purposes. Automated text messages are sent to mobile phones and text responses recorded electronically. The method is cheap and simple and allows rapid communication with people involving minimum disturbance. The ownership of mobile phones has increased: currently it is estimated that the rate of mobile phone ownership in the Americas is 94.1%,1 while, in some communities in the UK, ownership of a mobile phone is more common than a home landline.2 These statistics suggest that mobile phones may be an effective means of capturing research data from a wide public.

Health-related use of SMS has included modification of beliefs relating to medication adherence,3 4 delivering behavior change interventions,5 6 reminding patients of scheduled outpatient appointments,7 8 and supporting patients with disease control.9–13 In the maternity services, SMS messaging has been used successfully in a randomized controlled trial in Thailand to deliver health messages.11 However, most studies have looked at using SMS to send messages to patients, not for data capture: there is a limited literature on the use of the method for collection of research data.

We searched for studies that both used SMS for data collection and evaluated this method for reliability, validity, acceptability, or practicality. A number of studies have assessed the reliability of the data received via text messaging.14–21 However, these studies have either used small samples, only made within-group comparisons, used non-validated instruments, or did not assess the validity of the method, only the properties of the scale used. Response rates have varied from 15%14 to 70–75%19 and 100%.20 Higher response rates were achieved where researchers had previously met participants, were dependent on the context of the study (research or clinical need), or used persistent reminders.20 The successful use of SMS messaging for data collection has also been reported in the behavioral sciences, using university students as participants. Patient acceptance of the method is encouraging, with three studies reporting positive participant feedback in a variety of contexts.3 9 19

Overall therefore we were unable to find any within-participant studies of the reliability and validity of SMS text-based data collection from patients.

Every measurement method needs to have its reliability and validity checked before use in a demonstration study.22 The acceptability of the method to participants and its practicality for researchers are also important considerations. We planned to use SMS for data capture as part of a larger study on the breastfeeding plans and practices of women in Tayside, Scotland. This group has a high ownership of mobile phones, and SMS seemed to offer a simple way to consult them asynchronously, with minimum disturbance to their daily activities. However, in addition to data capture, we decided to evaluate the reliability, validity, acceptability, and practicality of this method of data collection.

Objective

The study aims were to quantify the reliability and validity of data gathered via SMS messages, our primary method for capturing the infant feeding choices of new mothers. We also aimed to assess women's views about the acceptability of this method of data collection and its practicality from the perspective of the researchers.

Materials and methods

Women in Tayside, Scotland, UK were recruited to the main study (to ascertain their attitudes to infant feeding and feeding plans) during pregnancy (n=355). The findings of the main study will be reported in a future publication. After delivery, women were followed up by SMS text messages every 2 weeks to ascertain their current feeding method. Finally, a telephone exit interview asked about their experiences of infant feeding.

SMS platform

The study website sent SMS messages to patients and received their response via a third party SMS provider, the ‘ActiveSMS’ internet messaging gateway. ActiveSMS is a two-way SMS messaging server for the Windows platform designed to integrate into bespoke applications. The study website used the ActiveSMS coding library to interface to its gateway and ActiveSMS and then sent the SMS to the network SMS Gateway (eg, Vodafone). For receiving messages, the process was reversed (see online appendix 1). Sent and received messages were stored on both the study website database and the third-party SMS provider database. No identifiers other than cell phone numbers were stored, however, to minimize privacy issues.

Question wording and SMS delivery

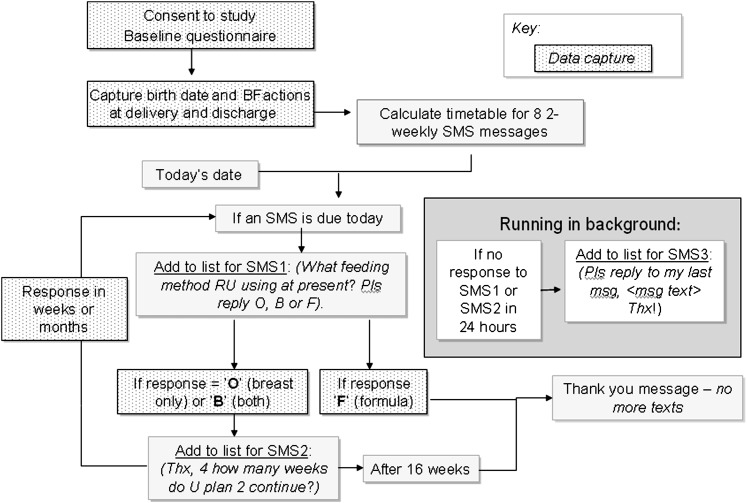

The schedule of SMS messages used in the main study is shown in figure 1. Two weeks after delivery of the baby, all participants were sent the following text:

Figure 1.

Schedule of SMS messages. BF, breast feeding.

SMS1: ‘The Feeding Your Baby Team asks, what infant feeding method RU using at present? Pls reply O, F, or B, where O=Only Breast, F=Formula, and B=Both.’

If the response was ‘F’, the participant was sent a final thank you text advising that no more texts would be sent and to expect a final contact by phone in 4 weeks. If the response indicated that any breast feeding continued (‘O’ or ‘B’), a second text was sent with a numerical response expected:

SMS2: ‘Thx, 4 how many weeks do U plan 2 continue?’

The cycle of SMS1 and SMS2 was repeated every 2 weeks until an ‘F’ response was received (indicating breast feeding had stopped), or the 16 week ‘end point’ was reached, whichever was sooner. Four weeks after their final text message, all women completed a final exit questionnaire administered by telephone.

Study 1: reliability

Factual reliability of SMS1

A second SMS message was sent to 48 women who had already responded to SMS1 (the factual question about feeding method) asking them the same question 1 day later (long enough for them to forget their previous answer but not so long that they were likely to have changed their feeding method). The message was worded to suggest that we were checking the SMS system: ‘Thanks for your reply. Checking our system works. The FYB Team asks again, what infant feeding method RU using at present? Pls rely O (Only breast), F (Formula) or B (Both).’

Reliability of SMS2

The reliability of numerical responses to SMS2 (the plans/intentions question only sent to breastfeeding mothers) was tested by sending a second SMS to 68 ‘only breast’ or ‘both’ women. The message was sent a day after their first response to SMS2: ‘Thanks for your reply. Checking our system works. The FYB Team asks again, for how long do you plan to continue? Please reply, for example, 6 weeks, 3 months.’

Study 2: validity

Face validity of SMS1 and SMS2

Clinical breastfeeding experts were asked to inspect the SMS questions and response options to assess for measurement of the appropriate construct.23

Criterion validity of SMS1

A further subgroup of 62 participants were telephoned within 24 h of their response to SMS1 (factual question) asking them the same question (SMS1) as asked in the text.

Criterion validity of SMS1 (compared with data collected by other means)

The SMS1 response closest to the first text response (if available) from women was compared with the feeding practice reported by the mother at a routine infant health check carried out by a local community nurse (the health visitor) at about 10 days (if available).

Construct/correlational validity of SMS1

We calculated correlations between the feeding method reported in the first text response (2 weeks) (received from 314 participants in the main study) with a variety of other data about the woman. We expected a positive correlation between reported breast feeding, maternal age, Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (a measure of affluence), and previous breast feeding.24 No relationship was expected with the gender of the baby, mode of delivery, or parity of the mother.

Study 3: acceptability and practicality of SMS for data collection

At the end point of the main study, women were phoned by the research assistant and an exit questionnaire was completed about their overall infant feeding experiences. At this time, a subgroup of 74 women were asked ‘Did you find receiving text messages about feeding your baby…’: ‘convenient?’; ‘a nuisance?’; ‘easy to do?’; ‘time consuming?’. A ‘yes’ or ‘no’ response was sought for each question. These women were also given the opportunity to make open comments about the text messaging.

Throughout the study, researchers kept a log of their experiences of using SMS messaging for data collection, which was later analyzed to uncover practical problems with the technique.

Sample recruitment

Sample recruitment for reliability and validity testing (studies 1 and 2)

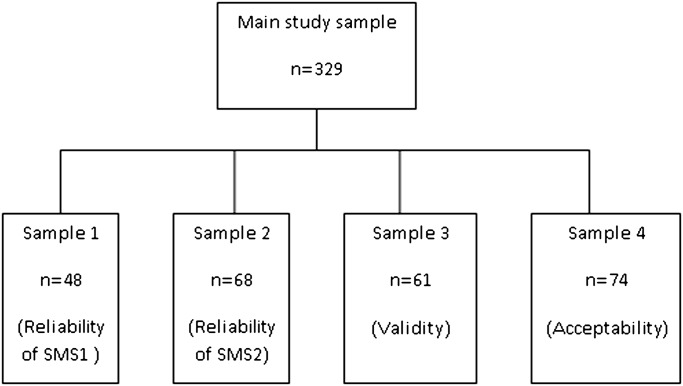

Three distinct convenience samples (samples 1–3) were drawn from a mainly urban population of women enrolled in the main study who were receiving text messages asking about infant feeding method and intentions. Of those receiving texts each day, women were allocated sequentially to one of the three sample groups in rotation for reliability/validity testing. If there was no reply to the call/text, they were included for ‘testing’ 2 weeks later (if they were still in the system) (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Summary of sample recruitment for each study.

Sample recruitment and data collection for assessing acceptability of the method (study 3)

A separate subgroup of the final 74 women exiting from the main study (sample 4) was asked during the exit telephone interview about their views on receiving text messages.

Data analysis

Cohen's κ describes the strength of agreement for a nominal scale used on separate occasions.22 25 It compares agreement with that expected by chance alone and so is a chance-corrected index of agreement. Weighted κ takes account of the distance between disagreements and so is appropriate for scales with more than two categories. There is no accepted standard for what is considered good agreement, but in general 0.6–0.8 is seen as ‘good’ agreement, while >0.80 is considered excellent. κ=1 indicates perfect agreement. Analyses were carried out in SAS V.9.2. Spearman's rank correlation was used to compare text responses with external measures in the analysis of construct validity.

In study 3, the qualitative comments from participants at the end of the telephone questionnaire were transcribed at the time of questionnaire completion. A simple thematic analysis was carried out independently by two researchers (HW and AS) to code and categorize replies.26 After discussion, any differences were resolved.

Results

Of the 355 women recruited to the main study, 329 were successfully followed up by SMS text messaging after delivery. The samples for reliability and validity testing were drawn from these 329 women. Table 1 shows the age and Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation distribution of the original baseline population and each of the study groups. The mean ages are very similar across groups, while groups 2 and 4 tend to have higher proportions of more affluent women than the baseline study and groups 1 and 3.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the women in each study

| Characteristic | Main sample (main study, n=355) |

Sample 1 (study 1: reliability of SMS1, n=48) |

Sample 2 (study 1: reliability of SMS2, n=68) |

Sample3 (study 2: validity studies, n=62) |

Sample 4 (study 3: acceptability, n=74) |

| Age, mean (SD) | 28.60 (5.83) | 29.67 (5.63) | 30.57 (4.55) | 28.97 (4.81) | 30.70 (4.89) |

| Age range | 16–42 | 18–39 | 20–40 | 18–42 | 20–42 |

| SIMD | Missing n=1 (0.3) | ||||

| 1–3 (high deprivation), n (%) | 157 (44.2) | 23 (47.9) | 19 (27.9) | 23 (35.3) | 17 (23.0) |

| 4–7 (medium deprivation), n (%) | 90 (25.4) | 10 (20.9) | 11 (16.2) | 26 (39.7) | 26 (35.1) |

| 8–10 (low deprivation), n (%) | 107 (30.1) | 15 (31.3) | 38 (55.9) | 13 (25.0) | 31 (41.9) |

SIMD, Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation.

Study 1: factual reliability of SMS1

Table 2 shows the agreement between the initial SMS message and the same message re-sent within 24 h. There was perfect agreement, with κ=1 (se=0.12; p<0.0001): all re-sent SMS messages were identical with the content of the original message.

Table 2.

Factual reliability of SMS1 (n=48) (sample 1)

| Re-sent SMS1 within 24 h | |||

| Formula | Only breast | Both | |

| Initial SMS1 | |||

| Formula | 25 | 0 | 0 |

| Only breast | 0 | 19 | 0 |

| Both | 0 | 0 | 4 |

Study 1: reliability of SMS2 (numerical question)

When a second SMS reporting feeding plans/intentions was compared with the first SMS on feeding plans (SMS2) (table 3), agreement was still good but less than perfect. In those feeding with ‘only breast’, κ=0.76 (95% CI 0.562 to 0.959) (p<0.0001). Agreement was slightly better in those who initially stated ‘both’ as feeding method, with κ=0.796 (95% CI 0.589 to 1.000) (p<0.0001).

Table 3.

Reliability of SMS2 (n=68) (sample 2)

| Only breast (n=47) | Second SMS2 | ||

| <2 months | 2–6 months | >6 months | |

| Initial SMS2 | |||

| <2 months | 3 | 1 | 0 |

| 2–6 months | 1 | 31 | 2 |

| >6 months | 0 | 1 | 8 |

| Both (n=21) | Second SMS2 | |||

| <1 months | 1–2 months | 2–6 months | >6 months | |

| Initial SMS2 | ||||

| <1 months | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 1–2 months | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| 2–6 months | 0 | 0 | 8 | 2 |

| >6 months | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

Study 2: face validity of SMS1 and SMS2

The questions were reviewed by experts in infant feeding.23 On the basis of their comments and after discussion, minor changes were made to the wording of questions to ensure the questions and response options made sense and appeared appropriate before testing with women.

Study 2: criterion validity of SMS1

Agreement was good for comparison of SMS1 with capture of the information using the same question asked over the telephone within 24 h, with κ=0.924 (95% CI 0.841 to 1.000) (p<0.0001) indicating excellent validity (table 4).

Table 4.

Criterion validity of SMS1 (n=62) (sample 3)

| Follow-up phone call within 24 h | |||

| Formula | Only breast | Both | |

| Initial SMS1 | |||

| Formula | 20 | 1 | 1 |

| Only breast | 0 | 27 | 0 |

| Both | 0 | 1 | 12 |

Study 2: criterion validity of SMS1 compared with data collected by other means

Agreement was also good between the first SMS response received at 14 days with the data retrieved from the health visitor 2-week records, with κ=0.854 (95% CI 0.733 to 0.974) (p<0.0001) (table 5).

Table 5.

Criterion validity of SMS1 (n=59) (sample 3, three missing)

| Health visitor 2-week visit data | |||

| Formula | Only breast | Both | |

| First SMS1 (14 days) | |||

| Formula | 17 | 0 | 1 |

| Only breast | 0 | 31 | 1 |

| Both | 0 | 3 | 6 |

Study 2: construct/correlational validity of SMS1

The comparison of current breastfeeding method with other related measures found that breast feeding correlated with age (r=−0.218, p<0.0001; younger women were less likely to breast feed), deprivation (r=−0.188, p=0.0007; deprived women were less likely to breast feed), and breast feeding a previous baby (r=−0.562, p<0.0001; women who had never previously breast fed were less likely to breast feed a subsequent child). There was no significant correlation with gender of the baby (r=−0.040, p<0.474), method of delivery (r=0.114, p<0.038), or parity (r=0.030, p<0.603). These results show that the SMS responses on feeding method are consistent with what is already known about the characteristics of mothers who are more likely to breast feed.

Study 3: acceptability and practicality of SMS messaging for data collection

Acceptability from participants' perspective

Two women could only be contacted by home phone during the study: one had no mobile phone, while the other preferred not to receive text messages. Of 74 women asked about the use of SMS messages at the end of the exit questionnaire, 97.3% (n=72) found the method convenient, and 100% (n=74) found it easy. Similarly, 96% (n=71) reported that the method was not a nuisance, and 100% (n=74) that it was not time consuming.

Participants' qualitative comments reinforce these findings and indicate that the majority thought text messaging an acceptable, practical, and convenient method for collecting answers to regular brief questions:

‘I thought it was great, so easy and quick, if you didn't have time to reply straight away didn't have to and just one letter to reply’

‘Good way for busy mums, modern, easier than paper and email’

‘I think it was a brilliant way of doing it, if it had been telephone calls I wouldn't have had time for it but being texts was brilliant.’

The few negative comments mainly related to difficulty in answering the second question:

‘…only minor thing not clear was what the second question meant, till weaning or what?’

‘I thought the second one wasn't that clear, first time was fine, wasn't sure if it meant till the child is a certain age or how many weeks - maybe asking for how much longer would be a bit clearer.’

Other negative comments related to the way the system was set up or to the automated nature of the system:

‘Only thing, different number every time on i-phone, if not replied, different number for reminder.’

‘received some maybe twice’

A few participants had technical or credit problems with their phones:

‘I ran out of credit and couldn't text back, not so convenient.’

‘Not good mobile reception so sometimes messages were not received at the right time’

Practicality from the researcher perspective

We kept a log of our experiences of using SMS text messaging to gather data. Owing to the complexity of the timing of the different text messages (a two-stage message format and different ‘entry’ points for each participant depending on date of delivery), a specially designed program was required to manage the database and schedule the texts. This required the input of a computer programmer at a late stage in the project and left only a short time available for piloting.

During the course of the study, a total of 2952 texts were sent to 355 women. A response was received to 2372 of these (80.4% response rate to texts) from 329 women (92.7% participant response rate). Of these, 2738 were sent automatically via the main scheduler, and 214 were sent ‘manually’. Texts were sent as scheduled to 91.9% of participants; however, because of system or researcher errors, 6.3% were sent the wrong number of texts (too many or too few), while in 1.8% of cases there were other problems. Reminders because of delayed response were sent on 659 occasions (22.3%), but 580 (88%) of these elicited no response. Some non-responses may have been due to participants changing mobile phone number or the cost of the texts for participants (an unfortunate and unforeseen feature of the SMS package chosen). Non-responses were followed up with a phone call and then a letter; successful contact meant some participants subsequently re-entered the system. Data from 42 women were gathered by phone call on 114 occasions when the SMS system was unavailable.

Early system problems (such as loss of changes to participant data or participants being sent too many texts) required resolution by a system shut down for 3 days. We initiated regular manual checking to identify problems. This was onerous as more women entered the system, but became less necessary once the scheduler program was revised. An alert process was incorporated latterly to inform researchers if an ‘uncategorised’ reply was received or in the event of a participant being unexpectedly excluded by the system. Once the system was working properly, we found it an easy to use and functional method of gathering a large volume of data, provided that the question/answer format was simple.

Discussion

As far as we know, this is the first study that has examined the reliability, validity, and acceptability of SMS messaging for capture of research data. Some previous studies only considered collecting clinical data.9 12 Others assessed reliability but not validity.14–18

Strengths of our study include the fact that reliability was checked against both texted repeat questions and telephoned questions, within a suitable time interval to avoid the data changing. We also looked at the reliability of answers to questions with both factual and numerical responses (study 1). Validity was checked against: a repeat of the same question asked over the phone; the same data collected by other means and against other proxy measures for feeding methods (study 2). In addition, we evaluated the acceptability and practicality of the method for data collection, from the perspective of both the participants and the researchers (study 3).

We achieved an excellent response rate, receiving text responses from 92.7% of the baseline sample. The low percentage of reminder texts required (22.3%) and the excellent overall response rate to texts (80.4%) compares well with other studies and data collection methods. Lower SMS response rates were found when there had been no previous contact with participants (15%14). Similar to our study, Anhøj and Møldrup19 reported a 70–75% response rate in a study of self-selected volunteers reporting asthma symptoms. The highest rate (100%20) required persistent reminders and, on some occasions, face-to-face contact.

We found that the use of text messaging for data collection using SMS1 (the factual question) was highly reliable and valid. Our findings are better than those reported in recent studies that have used SMS.17 18 Alfvén18 used SMS to capture pain data from a small sample of children, and, while compliance with the SMS method of data capture was reported, the reliability and validity of the method were not (only the validity and reliability of the scale itself). Johansen and Wedderkopp17 assessed test–retest reliability comparing SMS responses with telephone responses for data on low back pain in a small sample. They found good reliability (12% difference) for recall of recent data, but less precise results for data beyond 1 month. Our findings suggest that, for straightforward questions requiring a simple response (either numerical or one letter), this is a good method of gathering high-quality data. The qualitative comments confirmed the high acceptability and convenience of this as a method of collecting contemporaneous data from this client group.

The agreement was less high for the reliability of SMS2 (the numerical plans/intentions question). The qualitative comments offer an explanation for this finding. Some participants found the question asked in SMS2 slightly confusing, reporting uncertainty about whether the question meant ‘For how many weeks from today do you plan to continue?’ or ‘For how many weeks do you plan to continue (ie, age of the child when you will stop)?’. This highlights the need to keep the question wording (and required responses) simple and to ensure careful piloting of the questions.

The studies assessing criterion validity of SMS1 indicated that there was good agreement between data collected by text compared with the same data collected by telephone or by direct questioning by a health professional (in this case the health visitor). There was also good correlation between the method of feeding reported by text and other measures known to be related to feeding method, such as maternal age, deprivation,26 and previous breast feeding, and no relationship (as expected) with measures unrelated to feeding method (gender of baby, parity, and mode of delivery). Other studies have not addressed validity in this way. Researchers can therefore have confidence that this method of factual data collection is valid.

The high level of acceptability and lack of intrusion reported by this client group is a very positive finding. There are similar reports of the convenience of using mobile phones to gather data from patients or deliver health messages.19 27 The reported ease of incorporating receipt and sending of text messages into usual daily activities is very encouraging.

Our experiences of designing a program and running the system to manage the high volume of SMS messages has encouraged us to believe that this method of data capture has wide potential for application beyond the scope of this moderate sized study. As others have shown,5 12 13 28 messaging can be used to gather symptom information from patients for both research and clinical purposes. It has potential application in health promotion whereby messages could easily be disseminated by text.5 Support and encouragement could be provided for activities such as breast feeding as well as other types of behavior change (such as smoking cessation or dietary modification). The early identification of problems could lead to more efficient and effective use of the time of healthcare personnel. Applications could be designed for the next generation of smart phones with the ability to tailor messages to individual client characteristics. One participant indicated that being asked about her feeding on a regular basis (and being able to reply that she was still breast feeding) had provided a positive reward and an incentive to continue. This potential for text messaging as a motivational tool could be explored further. Mobile ownership is very high in the younger age group; there may be other client groups where ownership levels are lower. An additional consideration is that, in some locations, mobile reception on some networks is incomplete.

Our study was limited by small numbers in each sub study; however, table 1 shows that each subgroup was broadly representative of the main study population and large enough to produce reliable κ statistics. Samples 2 and 4 included a slightly higher proportion of women from the least deprived backgrounds. In study 1 (sample 2), we tested a question only relevant to women who were breast feeding. Similarly, study 3 (sample 4) was carried out toward the end of the main study, so many of these women had continued breast feeding. These differences are therefore not surprising, as women from more affluent areas are more likely to breast feed.26 As this was a study of infant feeding, all samples consisted mainly of younger women; however, a wide range of deprivation categories was included. The study involved the single topic of infant feeding method, so responses could be brief; this method may be unsuitable for research where more detail is required.

Conclusions

We conclude that, in this relatively young but deprived UK sample and for the brief questions we included, SMS was a reliable and valid method for capturing data for research purposes. It was also acceptable to the research participants and practical for researchers. This suggests that it is adequate for capturing data for clinical purposes and a useful method of data collection in many other research situations including randomized controlled trials.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Shelia Knight, who contributed to early plans for the study, and Massimo Brilliante, the software developer.

Footnotes

Contributors: HW: planned and designed the study, obtained funding for the study, convened project steering group, translated study protocol into detailed protocols and data collection forms for the researchers, trained and supported researchers in data capture, wrote and revised drafts of the paper. PTD: advised on study design, analyzed data, reviewed paper. AS: advised on study design, reviewed paper. GK: contributed to design of data capture, collected data, reviewed paper. EM-H: contributed to design of data capture, collected data, reviewed paper. PR: analyzed data, reviewed paper. JCW: performed literature review, designed the study, wrote first draft of this article. All authors approved the final version.

Funding: Office for the Chief Scientist, NHS Scotland under grant number CZH/4/568.

Competing interests: PTD has received funds for research grants in the past from GSK, Pfizer, Amgen and Otsuka pharmaceuticals.

Ethics approval: The study was granted approval by the NHS Tayside Research Ethics Committee on 08.07.2009 under reference 09/S1402/28.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Mobithinking http://mobithinking.com/mobile-marketing-tools/latest-mobile-stats#subscribers (accessed 15 Nov 2011).

- 2.Ofcom http://media.ofcom.org.uk/facts/ (accessed 11 Sep 2011).

- 3.Neville R, Greene A, McLeod J, et al. Mobile phone text messaging can help young people manage asthma. BMJ 2002;325:600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Petrie KJ, Perry K, Broadbent E, et al. A text message programme designed to modify patient' illness and treatment beliefs improves self-reported adherence to asthma preventer medication. Br J Health Psychol 2012;17:74–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cole-Lewis H, Kershaw T. Text messaging as a tool for behavior change in disease prevention and management. Epidemiol Rev 2010;32:56–69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Free C, Knight R, Roberston S, et al. Smoking cessation support delivered via mobile phone text messaging (txt2stop): a single-blind, randomised trial. Lancet 2011;378:49–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Downer SR, Meara JG. Da Costa AC. Use of SMS text messaging to improve outpatient attendance. Med J Aust 2005;183:366–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koshy E, Car J, Majeed A. Effectiveness of mobile-phone short message service (SMS) reminders for ophthalmology outpatient appointments: observational study. BMC Ophthalmol 2008;8:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferrer-Roca O, Franco Burbano K, Cárdenas A, et al. Web-based diabetes control. J Telemed Telecare 2004;10:277–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Franklin VL, Waller A, Pagliari C, et al. A randomized controlled trial of Sweet Talk, a text-messaging system to support young people with diabetes. Diabet Med 2006;23:1332–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jareethum R, Titapant V, Chantra T, et al. Satisfaction of healthy pregnant women receiving short message service via mobile phone for prenatal support: a randomized controlled trial. J Med Assoc Thai 2008;91:458–63 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liang X, Wang Q, Yang X, et al. Effect of mobile phone intervention for diabetes on glycaemic control: a meta-analysis. Diabet Med 2011;28:455–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mirza F, Norris T, Stockdale R. Mobile technologies and the holistic management of chronic diseases. Health Informatics J 2011;14:309–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bexelius C, Merk H, Sandin S, et al. SMS versus telephone interviews for epidemiological data collection: feasibility study estimating influenza vaccination coverage in the Swedish population. Eur J Epidemiol 2009;24:73–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lauriston K, Degl' Innocenti A, Hendel L, et al. Symptom recording in a randomised clinical trial: paper diaries vs. electronic or telephone data capture. Control Clin Trials 2004;25:585–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moumoulidis I, Mani N, Patel H, et al. A novel use of photo messaging in the assessment of nasal fractures. J Telemed Telecare 2007;13:387–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johansen B, Wedderkopp N. Comparison between data obtained through real-time data capture by SMS and a retrospective telephone interview. Chiropr Osteopat 2010;18:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alfvén G. SMS pain diary: a method for real-time data capture of recurrent pain in childhood. Acta Paediatrica 2010;99:1047–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anhøj J, Møldrup C. Feasibility of collecting diary data from asthma patients through mobile phones and SMS (short message service): response rate analysis and focus group evaluation from a pilot study. J Med Internet Res 2004;6:e42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kew ST. Text messaging: an innovative method of data collection in medical research. BMC Res Notes 2010;3:342 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1756-0500/3/342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salvador CH, Pascual Carrasco M, Gonzalez de Mingo MA, et al. Airmed-cardio: a GSM and Internet services-based system for out-of-hospital follow-up of cardiac patients. IEEE Trans Inf Technol Biomed 2005;9:73–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Friedman CP, Wyatt JC. Evaluation Methods in Biomedical Informatics. 2nd edn New York: Springer-Publishing, 2006:386 ISBN 0-387-25889-2 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Polit DF, Beck CT. Essentials of Nursing Research. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 24.ISD Scotland http://www.isdscotland.org/Health-Topics/Child-Health/Publications/2011-10-25/2011-10-25-Breastfeeding-Report.pdf?84164065123 (accessed 17 Nov 2011).

- 25.Dunn G. Statistical Evaluation of Measurement Errors: Design and Analysis of Reliability Studies. 2nd edn Chichester: Wiley, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3:77–101 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gerber B, Stolley M, Thompson A, et al. Mobile phone text messaging to promote healthy behaviors and weight loss maintenance: a feasibility study. Health Informatics J 2009;15:1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reimers S, Stewart N. Using SMS text messaging for teaching and data collection in the behavioral sciences. Behav Res Methods 2009;41:675–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.