Abstract

Mesenchymal cell populations contribute to microenvironments regulating stem cells and the growth of malignant cells. Osteolineage cells participate in the hematopoietic stem cell niche. Here, we report that deletion of the miRNA processing endonuclease Dicer1 selectively in mesenchymal osteoprogenitors induces markedly disordered hematopoiesis. Hematopoietic changes affected multiple lineages recapitulating key features of human myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) including the development of acute myelogenous leukemia. These changes were microenvironment dependent and induced by specific cells in the osteolineage. Dicer1−/− osteoprogenitors expressed reduced levels of Sbds, the gene mutated in the human bone marrow failure and leukemia predisposition Shwachman-Bodian-Diamond Syndrome. Deletion of Sbds in osteoprogenitors largely phenocopied Dicer1 deletion. These data demonstrate that differentiation stage-specific perturbations in osteolineage cells can induce complex hematological disorders and indicate the central role individual cellular elements of ‘estroma’ can play in tissue homeostasis. They reveal that primary changes in the hematopoietic microenvironment can initiate secondary neoplastic disease.

Mesenchymal cells are a part of virtually every tissue in metazoans and are thought to participate in organ formation, cellular composition, patterning and size. In adult tissues, these cells are considered ‘stroma’ without clear function. Identification of somatic stem cell populations has made possible the study of heterologous cells comprising their niche. Mesenchymal cells of osteolineage have been shown to regulate hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) 1,2 with osterix expressing skeletal progenitors initiating ectopic HSC niche formation3. We previously examined mesenchymal-HSC interactions using mice engineered to express individual genes in osteoblastic cells1,4 and now sought to define more precisely the stage of osteolineage differentiation critical for hematopoiesis using promoters more restricted in their expression to alter candidate genes. We chose to alter a gene that could modulate a landscape of other gene products.

Dicer1 is a RNase III endonuclease essential for miRNA biogenesis5 and RNA processing6. MiRNAs regulate hematopoietic cell fate 7 and global down-regulation of miRNAs by Dicer1 deletion promotes tumorigenesis in a cancer-cell-autonomous manner8. We used Dicer1 deletion as a means of altering multiple gene products in subsets of mesenchymal osteolineage cells. We intercrossed mice expressing GFP-Cre recombinase under the transcriptional control of the osterix9 promoter expressed in osteoprogenitor cells to mice with floxed Dicer1 alleles10 generating Osx-GFP-Cre+: Dicerfl/+ (OCDfl/+control) and Osx-GFP-Cre+ Dicerfl/fl (OCDfl/fl mutant) mice. The Cre transgene in this model is expressed coordinately with endogenous Osterix11 (figure 1a). Mutant mice were born at Mendelian frequency, but displayed growth retardation and impaired survival (~30% mutant mortality by 8 weeks). Therefore, we examined mice at age 4–6 weeks.

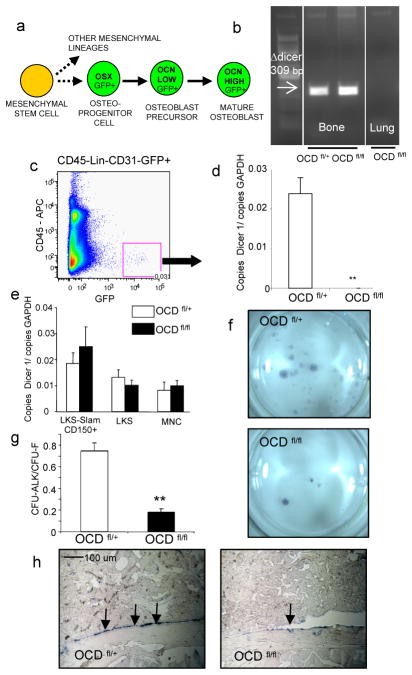

Figure 1. Impaired osteoblastic differentiation in OCD fl/fl mice.

a, endogenous osterix expression in osteolineage cells. Dicer1 deletion was demonstrated by b, genomic PCR and c,d, gene expression of primary osteolineage cells (n=5) e, dicer1 gene expression in hematopoietic subsets excluding dicer1 deletion from hematopoietic cells in OCD fl/fl mice (n=4) f–h impaired osteogenic differentiation capacity of OCD fl/fl bone marrow stromal cells as shown by reduced CFU-Alk (f,g) (n=2, performed in quadruplicate) and decreased osteocalcin gene expression by in situ hybridization (h). Data are mean ± s.e.m. * p≤0.05, **p≤0.01. OSX=osterix, LKS=lineage−ckit+Sca− cells, CFU-ALK=colony forming unit alkaline phosphatase. For further details see supplementary information.

Impaired osteoblastic differentiation

Dicer1 gene deletion in bone was shown by genomic PCR (figure 1b) and its efficiency confirmed by qPCR of Dicer1 mRNA in primary GFP+ (CD45−lineage−CD31−) cells (figure 1c,d and supplementary figure 1a,b). Dicer1 was not deleted in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (figure 1e) nor expressed in other hematopoietic subpopulations (not shown). Bone marrow stromal osteogenic colony number was decreased relative to total colony forming number (CFU-ALK/CFU-F), indicative of reduced osteogenic differentiation (figure 1f,g). OCD fl/fl bone marrow stromal cultures also demonstrated decreased alkaline phosphatase and calcified matrix deposition upon osteogenic differentiation (supplementary figure 1d). In vivo, osteoblasts from OCDfl/fl mice expressed less of the terminal differentiation marker osteocalcin (figure 1h and supplementary figure 1e). Altered texture of the mineralized bone matrix was observed (supplementary figure 1f), but not reduction in trabecular or cortical bone volume (supplementary figure 1g,h). Osteoblast number was modestly, although significantly decreased, whereas osteoclast number and function was not affected (supplementary figure 1i–k and not shown). Taken together, the data show that Dicer1 deletion in osteoprogenitors impairs osteoblastic differentiation both in vitro and in vivo.

Myelodysplasia in OCDfl/fl mice

Leukopenia with reduced numbers of cells in all leukocyte subsets was found in OCDfl/fl mice (figure 2a and supplementary figure 2a). Erythrocyte and platelet counts varied widely in OCDfl/fl mice with some animals showing profound anemia and thrombocytopenia (figure 2a). The variability was at least partly explained by extramedullary hematopoiesis in the spleen (supplementary figure 3) mitigating cytopenia in those animals. The bone marrow of OCDfl/fl mice was normo- to hypercellular (supplementary figure 2c,d). No significant differences were found in the frequency of immunophenotypically defined hematopoietic stem (Lineage−ckit+Sca1+(LKS)CD150+CD48−) and progenitor (LKS) cells (supplementary figures 2d,e and 4). Limiting dilution transplant analysis revealed an increase in HSCs in mutants which did not reach statistical significance (1:29000 vs. 1:52000, p=0.14). HSC and progenitor function was not impaired in OCDfl/fl mice as demonstrated by competitive reconstitution capacity upon transplantation or colony-forming unit (CFU-C) analysis (supplementary figure 2f,g). Decreased blood cell counts despite normal bone marrow cellularity and normal to increased stem cell function is characteristic of ineffective hematopoiesis.

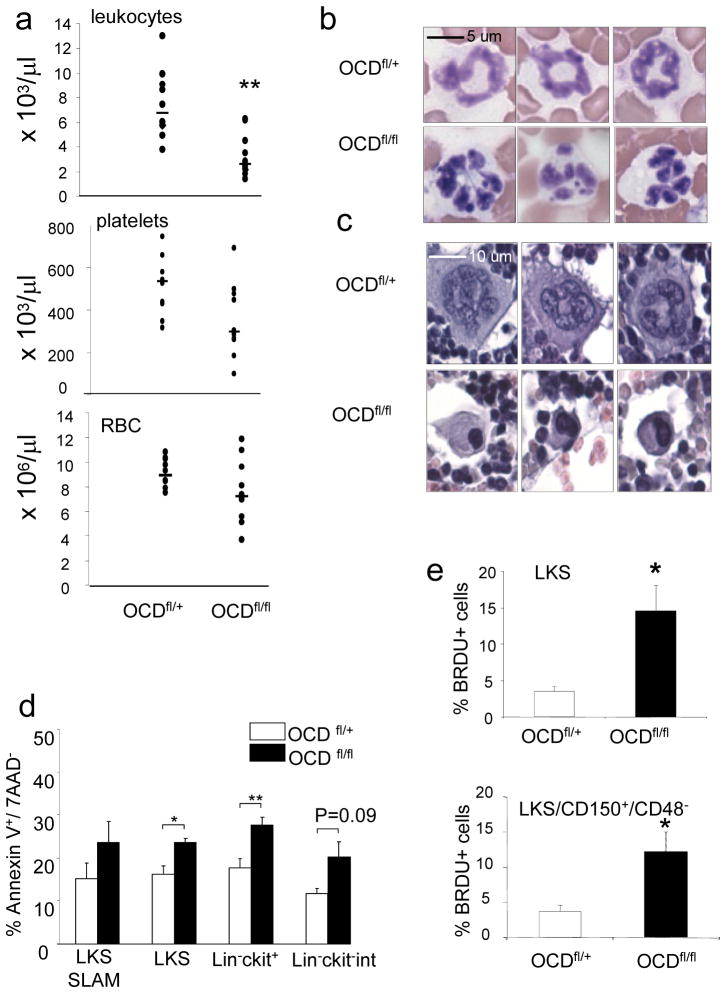

Figure 2. Myelodysplasia in OCD fl/fl mice.

a, Leukopenia with variable anemia (p=0.16) and thrombocytopenia (p=0.08) in OCD fl/fl mice (n=10). b, blood smears showing dysplastic hyperlobulated nuclei in granulocytes c, bone marrow sections showing micro-megakaryocytes with hyperchromatic nuclei d, increased apoptosis of hematopoietic progenitor cells in OCD fl/fl mice. (n=4) e, increased proliferation of hematopoietic progenitor cells as shown by in vivo BRDU labeling (n=4). Data are mean ± s.e.m. * p≤0.05, **p≤0.01. RBC=red blood cells, LKS= lineage −C-kit+ Sca1+ cells LKS-SLAM= lineage −C-kit+ Sca1+ CD150+ CD48− cells L-K+= lineage−c-kit+ cells L-K-int=lineage− Ckit intermediate, BRDU= bromodeoxyuridine. For further details see supplementary information.

Morphologic assessment revealed marked dysplasia with nuclear hypersegmentation in neutrophils and giant platelets in the blood and micromegakaryocytes with hypolobulated, hyperchromatic nuclei in the bone marrow of OCDfl/fl mice (figure 2b,c and supplementary figure 5a–c) There was neither increased fibrosis on reticulin staining nor ring sideroblasts on iron stains of the bone marrow (not shown). Peripheral cytopenia with dysgranulopoiesis and dysplastic megakaryocytes is consistent with a diagnosis of MDS in mice according to the Bethesda criteria12. The aetiology of human MDS is complex and poorly understood. It has been very difficult to engraft and propagate the hematopoietic characteristics of human MDS in murine models by transplanting hematopoietic cells from MDS patients into immunodeficient mice, sparking a longstanding debate about a potential causative or facilitating role of the microenvironment in the pathogenesis of this disease.

Examining other key characteristics of the human disease, we observed increased apoptosis and proliferation of primitive hematopoietic progenitors (figure 2d,e and supplementary figures 6, 7 and 8a)13. Increased apoptosis was limited to primitive progenitor cells, as no differences were observed in differentiated (lineage +) cells (not shown). Within Lineage-ckit+ cells, apoptosis was most pronounced in megakaryocyte-erythroid progenitors (MEP) (supplementary figure 7). HSC generally are more quiescent in close proximity to the endosteal surface in vivo.14. When we imaged transplanted wild-type cells, we noted that LKS cells located significantly closer to the endosteum in mutant animals compared with controls (supplementary figure 8b,c) and the frequency of cell duplets, an indicator of cell proliferation, was strikingly increased (supplementary figure 8d), demonstrating increased proliferation of primitive progenitors despite close proximity to the endosteal surface.

OCDfl/fl mice also had reduced B-cells and B-cell progenitors with a concomitant increased frequency of myeloid cells in the bone marrow (supplementary figures 2h,i and 9) as observed in human MDS15,16. The nature of the B-cell defect in early MDS has remained elusive since cytogenetic studies have failed to link B-cells to the malignant clone in MDS. Interestingly, osteoblasts have recently been shown to constitute a niche for B-cell lymphopoiesis17,18. OCDfl/fl mice also displayed variable, but increased vascularity in the bone marrow, a feature that has been described in MDS19 (supplementary figure 2j). Deficiency of either vitamin B12 or folate which can cause myelodysplastic features13, were excluded as contributing factors in the OCD fl/fl mice (not shown).

Myelodysplasia is environmentally induced

Next, we used transplantation to assess the contribution of the microenvironment to the hematopoietic phenotype. Hematopoietic cells of OCDfl/fl (CD45.2) mice demonstrating profound cytopenia and myelodysplastic features were transplanted into (CD45.1) B6.SJL mice (“wild-type environment”) (figure 3a). Transplanted animals were without apparent signs of disease. Assessment of peripheral blood and bone marrow 16 weeks (figure 3a–d and supplementary figure 10) or 12 months (supplementary figure 11) after transplant showed nearly complete donor (CD45.2) chimerism with complete normalization of cytopenias, granulocyte and megakaryocyte morphology, intramedullary apoptosis of primitive progenitors and bone marrow vascularity. The results indicate that the hematopoietic phenotype cannot be propagated in a hematopoietic cell-autonomous matter. Conversely, when bone marrow cells from wild-type B6.SJL mice were transplanted into lethally irradiated mutant or control mice (figure 3e–h and supplementary figure 12), mutant recipients developed leukopenia, anemia and thrombocytopenia, dysplastic features of CD45.1 blood cells, increased bone marrow vascularity with dysplastic megakaryocytes, increased frequency of myeloid cells, decreased frequency of B-cell subsets and increased apoptosis of primitive hematopoietic progenitors. The combined experiments provide formal proof that the myelodysplastic phenotype observed in mutant mice is determined by the micro-environment.

Figure 3. Myelodysplasia in OCD fl/fl mice is induced by the bone marrow microenvironment.

a, bone marrow cells of OCD fl/fl or littermate OCD fl/+ mice (n=2) were transplanted into lethally irradiated WT (B6.SJL) mice (n=4 per OCD mouse) demonstrating complete normalization of leukopenia (b), granulocyte (c) and megakaryocyte (d, open arrows ) morphology (open arrows) and bone marrow vascularity (d, closed arrow) 16 weeks post-transplant. Conversely, when e, wildtype B6.SJL cells were transplanted into OCD fl/+ (n=8) or OCD fl/fl (n=8) mice, hematopoiesis in mutant mice at 8 weeks dysplayed f, leucopenia g, dysgranulopoiesis with giant platelets (indicated by arrows) and h, increased bone marrow vascularity with dysplastic megakaryopoiesis (arrows). Data are mean ± s.e.m. * p≤0.05, **p≤0.01. For further details see supplementary information.

Osteolineage stage specificity

To examine whether mesenchymal cells of the osteoblastic lineage can directly induce aberrant hematopoiesis, we established bone marrow derived stromal cell cultures from OCDfl/+ vs. OCDfl/fl mice and co-cultured these with red-fluorescent (DS-red) hematopoietic LKS and MEP cells (supplementary figure 13). Stromal cells were osteolineage committed as evidenced by Osterix expression (and deletion of Dicer1; not shown) but lacked terminally differentiated osteoblasts as indicated by the absence of osteocalcin expression (supplementary figure 13a). Co-cultures on osterix+ osteocalcin−OCDfl/fl stromal cells revealed increased proliferation of LKS cells (supplementary figure 13 b–d) and impaired megakaryocyte differentiation of MEP cells (supplementary figure 13 e–h). The latter was accompanied by morphological changes in megakaryocytic cells (supplementary figure 13i), resembling those observed in vivo. Together, the data show that the disruption of hematopoiesis observed in OCDfl/fl mice in vivo is, at least partly, the result of a direct effect of osterix+osteocalcin− osteolineage cells on hematopoietic cell proliferation and differentiaton. To further explore whether osteoprogenitor cells rather than terminally differentiated (osteocalcin+) osteoblasts were the key participants in the hematopoietic abnormality, we crossed Dicerfl/fl with mice in which cre recombinase was driven by the osteocalcin promoter. Efficient recombination by the osteocalcin-cre as previously demonstrated20 was confirmed (supplementary figure 14a) and serial dilution of DNA isolated from long bones demonstrated equivalent efficacy of Dicer1 deletion using either the osteocalcin or osterix driven cre (not shown). Dicer1 deletion in this genetic context recapitulated some aspects of the bone phenotype, notably the altered texture and increased volume of cortical bone (supplementary figure 14b,c), but did not result in any hematopoietic abnormalities (supplementary figure 14d–h). The data demonstrate that osteoprogenitor cell-specific effects of Dicer1 deletion underlie the disruption of hematopoiesis and indicate that select subsets of cells in the osteoblast lineage have discrete functions in regulating hematopoiesis.

Emergence of leukemia

Human MDS is characterized by transformation to acute myeloid leukemia in a significant subset of patients. Strikingly, we observed the infrequent occurrence of myeloblastic tumors in OCDfl/fl mice. Four mice were observed to have facial tumors (estimated frequency 2/100 OCDfl/fl animals) of which three animals were available for detailed analysis (figure 4a). Tumors appeared at the age of 2–3 weeks and mice died at the age of 4–5 weeks. Analyses in a separate cohort of animals demonstrated that dysplastic features were already present in three week old animals (supplementary figure 15), suggesting that tumorigenesis occurred in the context of existing dysplasia. Histological examination of the tumors established a diagnosis of myeloid sarcoma (figure 4b), a soft-tissue complication of acute myelogenous leukemia (AML). Dicer1 had not been deleted in these myeloid sarcomas as determined by genomic PCR (figure 4c). Comparative genomic hybridization to germline DNA revealed genetic abnormalities in all tumors, providing direct evidence that the micro-environment facilitated clonal evolution of tumor cells (figure 4d and supplementary figure 16). Cytogenetic abnormalities included amplification of a common (27 Kb) region on chromosome 14qC1 in two tumors, the biological relevance of which, in the absence of known genes related to tumorigenesis in this region, is under investigation.

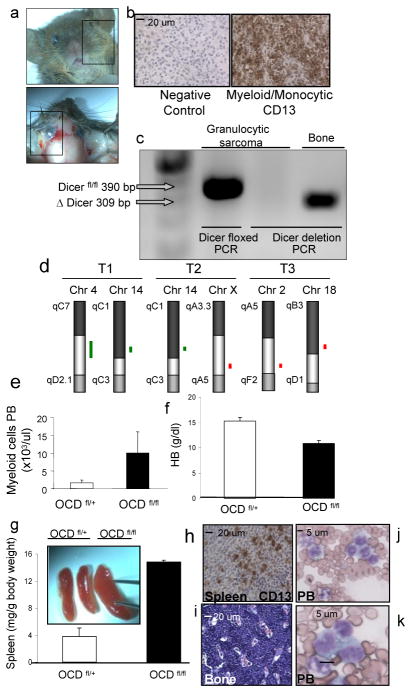

Figure 4. Myeloid sarcoma and acute myelogenous leukemia in OCD fl/fl mice.

a, tumors infiltrating soft tissue in 2–4 weeks old mice. Data from one representative animal. b, tumor sections showing predominantly myeloblasts admixed with maturing granulocytes, typical of myeloid sarcoma and confirmed by immunostaining with CD13. c, exclusion of Dicer1 deletion in myeloid sarcoma cells by genomic PCR. Bone from the same animal as positive control. d, genomic aberrancies detected in myeloid sarcomas (n=3) as detected by array-based CGH. A common amplified region was identified on chromosome 14qC1 in two tumors. Green lines represent amplifications, red line represents deletion e, myelocytosis, f, anemia, g, splenomegaly with h, infiltration of CD13+ blasts in the spleen and i, bone marrow, and j–k, monocytic blasts in a background of dysplastic granulocytes in the peripheral blood. HB=hemoglobin, PB=peripheral blood

The myeloid sarcomas displayed infiltrative behavior into surrounding tissues (supplementary figure 17) and were diagnosed in a context of myelocytosis (figure 4e), anemia (figure 4f), profound splenomegaly with infiltration of blasts (figure 4g,h) and a marked increase in blasts with a monocytic appearance in blood and bone marrow (figure 4i–k). This combination of findings strongly resembles monoblastic AML (FAB subtype AML M4/M5) in humans and fulfilled all criteria for the diagnosis of AML in mice12. Although the presence of myeloid sarcoma and acute monocytic leukemia-like disease in OCDfl/fl mice was sporadic, myeloid sarcomas were never observed in OCDfl/+ or Osx-Cre- mice (which were four-fold more abundant than mutant animals) and the occurrence of spontaneous AML in mice at an age of 2–3 weeks is unprecedented to our knowledge. Taken together, these data demonstrate that disruption of Dicer1 from cells of the osteoblastic lineage causes myelodysplasia in mice recapitulating key characteristics of human MDS, including the propensity to develop AML.

Deletion of Shwachman-Diamond-Bodian Syndrome gene

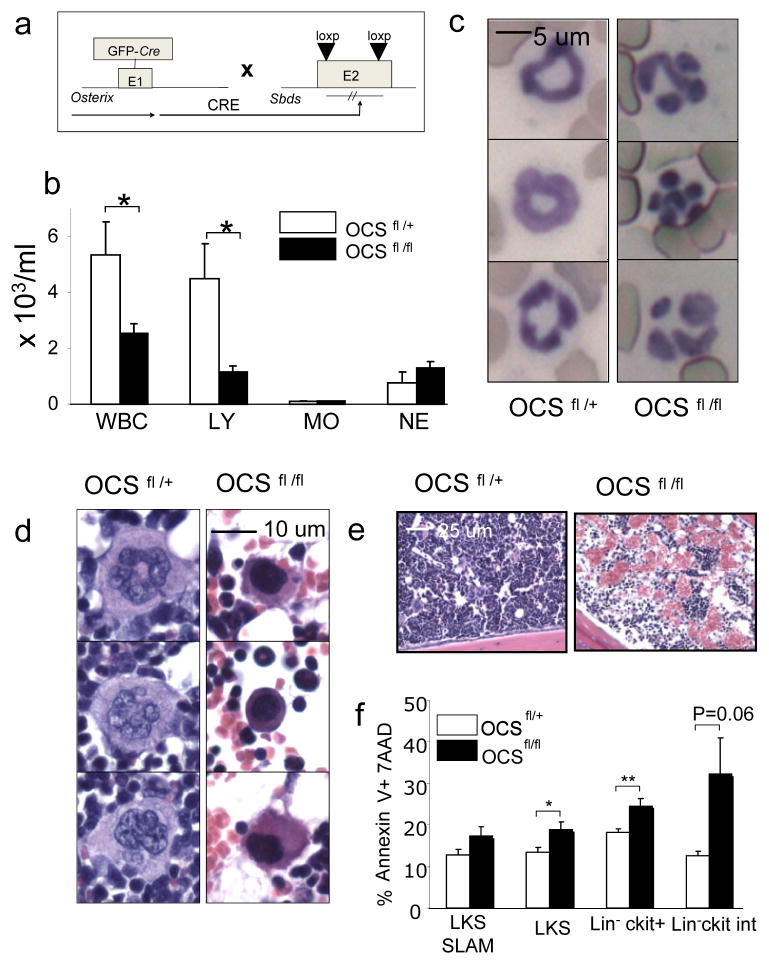

To obtain insight into the genes and molecular pathways in osteolineage cells driving the disruption of hematopoiesis in OCDfl/fl mice, we performed gene expression profiling of primary OCDfl/+ and OCDfl/fl osteolineagecells (GFP+CD45−lin−CD31−). Microarray analysis revealed a broad changes in the transcriptome in OCDfl/fl osteolineage cells with differential expression of 656 genes (p-value ≤ 0.05, Student’s t test) representing a wide array of functional groups (supplementary table 1). Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) revealed significant enrichment (FDR < 0.05) of genes involved in early osteoblastic differentiation and commitment 21, including the Wnt/βcatenin9 and TGF-β signaling pathway22, in OCDfl/+ samples (supplementary table 2). Notably differentially expressed genes and pathways further included stress response genes and cytokines (supplementary tables 2 and 3) with significant downregulation of the Shwachman-Diamond-Bodian Syndrome gene (Sbds) (2.43-fold; p=0.028, table S1) of particular interest because of its association with human disease. Inactivating mutations in the Shwachman-Bodian-Diamond Syndrome (Sbds) gene are highly associated with the clinical syndrome23 characterized by skeletal abnormalities, bone marrow failure with mild myelodysplastic changes, the propensity to develop MDS and secondary AML, increased intramedullary apoptosis of hematopoietic progenitors and exocrine pancreatic dysfunction. Studies knocking down the Sbds gene in hematopoietic progenitor subsets have failed to recapitulate key features of the clinical phenotype24 and a role of the bone marrow micro-environment in the pathogenesis of the syndrome has been suggested25. Targeted deletion of Sbds from osteoprogenitor cells by intercrossing Osterix-Cre mice to mice containing conditional (floxed) Sbds alleles (figure 5a) (S. Zhang et al, manuscript submitted) resulted in altered texture of the cortical bone (supplemental figure 18a), leukopenia and lymphopenia (but not neutropenia) (figure 5b), dysplastic features of neutrophils in the peripheral blood (figure 5c) and micromegakaryocytes (figure 5d) with increased vascularity of the bone marrow (figure 5e). Further similarities with OCDfl/fl mice included decreased frequency of B-cells and B-cell progenitors (supplementary figure 18b), increased frequency of myeloid cells (supplementary figure 18c) and intramedullary apoptosis of hematopoietic progenitor cells (figure 5f). Collectively, the data show that conditional deletion of Sbds from osteoprogenitor cells recapitulates key characteristics of OCDfl/fl mice and implicate osteoprogenitor cells in the pathogenesis of the Shwachman-Diamond syndrome.

Figure 5. Targeted deletion of the Sbds gene from osteoprogenitor cells recapitulates many features of the OCD fl/fl phenotype.

a, genetic model of Sbds deletion from osteoprogenitor cells b, leukopenia (n=8) c, dysplasia of neutrophils in peripheral blood d, dysplasia of megakaryocytes (micro-megakaryocytes) e, hypervascularity of the bone marrow f, increased intramedullary apoptosis of hematopoietic progenitor cells(n=5). Data are mean ± s.e.m. * p≤0.05, **p≤0.01.

DISCUSSION

These studies show that specific changes in specific mesenchymal cells of the hematopoietic microenvironment may be sufficient to initiate a complex phenotype of disordered homeostasis with similarities to myelodysplasia, a poorly understood human disease. Further, we demonstrate the ability of this abnormality to result in the emergence of a clonal neoplasm in a cell type of clearly distinct lineage with distinct secondary genetic changes. The data indicate that individual, well defined, mesenchymal microenvironment constituents can be primary enablers of neoplastic changes in a heterologous cell type.

While a series of genetic and epigenetic events in a single cell may be necessary for oncogenesis, they may not be sufficient and a permissive microenvironment has been hypothesized to be required for frank malignancy to emerge26. Examples of microenvironmental contributions to neoplasia include a necessary mast cell contribution to Nf1 induced neurofibromas27 and mesenchymal cell alteration of epithelial tumor growth kinetics28,29. Changes in a tissue microenvironment have also been suggested to precede and promote the initiation of genetic events by creating a “pre-malignant” state characterized by disruption of quiescence inducing signals or increases in proliferative signaling30,31. This has been validated experimentally with altered TGF-β signaling in tissue fibroblasts32 and with myeloid progenitor expansion following RAR-γ deletion in bone marrow or Rb deficiency in hematopoietic and microenvironmental cells33,34.

Our findings further the paradigm of malignancy resulting from the interplay of cell autonomous and microenvironmentally determined events and point to the microenvironment as the site of the initiating event that leads to secondary genetic changes in other cells. It is therefore possible to envision a ‘niche-based’ model of oncogenesis whereby a change in a specific microenvironmental cell can serve as the primary moment in a multi-step process toward malignancy of a supported, but distinct cell type. Signals from the microenvironment may select for subsequent transforming events and therefore such signals may represent candidate therapeutic targets in both treatment and prevention strategies.

Whether osteoprogenitor cell abnormalities play a role in the pathogenesis of human MDS and leukemia cannot be discerned from our studies. MDS is a heterogeneous disorder in which cytogenetics can be normal or reveal specific clonal lesions such as deletion of 5q. A role for the microenvironment in MDS has been raised, and reduced osteoblast surface and unchanged bone volume similar to our OCDfl/fl model has been reported35. Our findings raise the possibility that microenvironmental alterations may precede and facilitate clonal evolution in MDS. Studies examining patient samples will explore this possibility.

The Sbds studies provide further suggestive links to human disease. The human syndrome combines features seen in our model and raises the issue of whether both the pathophysiology of the disorder and the difficulty in treating this syndrome with bone marrow transplantation is in part due to a microenvironmental defect in the bone marrow.

The function of Sbds is itself unclear, but it has been implicated in ribosomal biogenesis23 and may therefore share with Dicer1 the ability to modulate the gene expression ‘landscape.’ While we pursued Sbds because its expression was decreased in the absence of Dicer1, levels in OCSfl/fl are likely to be even lower and as a consequence, may not faithfully portray the role of Sbds in our model. We therefore regard Sbds as a candidate participant in the phenotype of OCDfl/fl mice, but further studies will be needed to define the collaborating molecules causing the hematopoietic abnormalities.

These studies were initiated focusing on the stem cell niche, but the results indicate that individual microenvironment constituents can serve as regulators of tissue functions beyond that of stem cell support. Osteoprogenitor dysfunction induced altered proliferation and differentiation of both HSCs and distinct hematopoietic progenitor subsets and induced changes in the tissue architecture. Within a tissue microenvironment, certain elements may have far broader, integrative functions as the osteoprogenitor cells did here. There may be a hierarchy of activity within niche components as well as the cells they regulate. Our studies provide the rationale for further exploration of the complexity of mesenchymal ‘stroma’ and the role specific mesenchymal subsets may play as primary regulators of normal and disordered tissue function.

METHODS SUMMARY

Mice

Osx-Cre transgenic mice9, Ocn-Cre transgenic mice20 and floxed Dicer1 mice10, have been described. B6.SJL-Ptprca Pep3b/BoyJ mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory.

Transplantation

For competitive transplantation, 5 × 105 bone-marrow cells from 6-week-old OCD fl/+ or OCD fl/fl (CD45.2) littermates admixed with 5 × 105 CD45.1+ (competitor) WT cells were injected into lethally irradiated (9 Gy, split dose) BL6-SJL (CD45.1+) mice. For “ wt into mutant” experiments, wildtype congenic BL6/SJL (CD45.1+) bone marrow cells (1 × 106 cells/recipient) were transplanted into lethally irradiated 4 week old OCD fl/+ and OCD fl/fl (CD45.2+) recipients. For “ mutant into wt” experiments, OCD fl/+ or OCD fl/fl (CD45.2+) were transplanted into lethally irradiated 4 week old BL6/SJL(CD45.1+) animals. Donor cell engraftment was confirmed by FACS.

Full methods and any associated references are available as supplementary information.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ernestina Schipani, Eyal Attar and Henry Kronenberg for advice and discussion, Andy McMahon for providing the osx-cre mice, Joji Fujisaki, Damien Wilpitz, Masanobu Ohishi, Sonia Vallet, Michael Churchill and Graham Frankl for technical assistance, Gou Young Koh for providing VEGF-TRAP, the Histocore (Endocrine Unit), Flow Core at the Center for regenerative Medicine/ Massachusetts General Hospital ( Laura Pickett and Kat Folz-Donahue) and Fred Preffer and David Dombrowski for assistance with histology and flow-cytometry. David Machon for help preparing the manuscript and the Cytogenetics Core at Brigham Women/Dana Farber (Yun Xiao and Charles Lee) for performing CGH analyses.

This work was supported by a Fellowship Award of the Dutch Cancer Society and a Special Fellowship Award of The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society to M.H.G.P.R. and grants of the National Institutes of Health to D.T.S

Footnotes

Author contributions

M.R., S.G. and D.S. initiated the study. M.R., S.M. and D.S. designed the experiments and analyzed the data. M.R. carried out most of the experimental work with the help of S.M., J.S., T.K., S.G., E.S., S.Z., M.M., Z.A., and J.F. B.E. and F.A. analyzed the microarray results. R.H. reviewed bone marrow histology and peripheral blood morphology. C.L. supervised the in vivo imaging studies. M.M. and J.R. provided materials and discussion, M.R. and D.S. wrote the manuscript. D.S. directed the research. All authors discussed and commented on the manuscript.

References

- 1.Calvi LM, et al. Osteoblastic cells regulate the haematopoietic stem cell niche. Nature. 2003;425(6960):841. doi: 10.1038/nature02040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang J, et al. Identification of the haematopoietic stem cell niche and control of the niche size. Nature. 2003;425(6960):836. doi: 10.1038/nature02041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chan CK, et al. Endochondral ossification is required for haematopoietic stem cell niche formation. Nature. 2009;457(7228):490. doi: 10.1038/nature07547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fleming HE, et al. Wnt signaling in the niche enforces hematopoietic stem cell quiescence and is necessary to preserve self-renewal in vivo. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2(3):274. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116(2):281. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krol J, et al. Ribonuclease dicer cleaves triplet repeat hairpins into shorter repeats that silence specific targets. Mol Cell. 2007;25(4):575. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lu J, et al. MicroRNA-mediated control of cell fate in megakaryocyte-erythrocyte progenitors. Dev Cell. 2008;14(6):843. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kumar MS, et al. Impaired microRNA processing enhances cellular transformation and tumorigenesis. Nat Genet. 2007;39(5):673. doi: 10.1038/ng2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rodda SJ, McMahon AP. Distinct roles for Hedgehog and canonical Wnt signaling in specification, differentiation and maintenance of osteoblast progenitors. Development. 2006;133(16):231. doi: 10.1242/dev.02480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cobb BS, et al. T cell lineage choice and differentiation in the absence of the RNase III enzyme Dicer. J Exp Med. 2005;201(9):1367. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakashima K, et al. The novel zinc finger-containing transcription factors osterix is required for osteoblast differentiation and bone formation. Cell. 2002;108(1):17. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00622-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kogan SC, et al. Bethesda proposals for classification of nonlymphoid hematopoietic neoplasms in mice. Blood. 2002;100(1):238. doi: 10.1182/blood.v100.1.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heaney ML, Golde DW. Myelodysplasia. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(21):1649. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199905273402107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Celso CL, et al. Live-animal tracking of individual haematopoietic stem/progenitor cells in their niche. Nature. 2008 doi: 10.1038/nature07434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sternberg A, et al. Evidence for reduced B-cell progenitors in early (low-risk) myelodysplastic syndrome. Blood. 2005;106(9):2982. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van de Loosdrecht AA, et al. Identification of distinct prognostic subgroups in low- and intermediate-1-risk myelodysplastic syndromes by flow cytometry. Blood. 2008;111(3):1067. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-098764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu J, et al. Osteoblasts support B-lymphocyte commitment and differentiation from hematopoietic stem cells. Blood. 2007;109(9):3706. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-08-041384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu JY, et al. Osteoblastic regulation of B-lymphopoiesis is mediated by Gs {alpha} - dependent signaling pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(44):16976. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802898105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Korkolopoulou P, et al. Prognostic evaluation of the microvascular network in myelodysplastic syndromes. Leukemia. 2001;15(9):1369. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang M, et al. Osteoblast-specific knockout of the insulin-like growth factor (IGF) receptor gene reveals an essential role of IGF signaling in bone matrix mineralization. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(46):44005. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208265200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schilling T, et al. Microarray analyses of transdifferentiated mesenchymal stem cells. J Cell Biochem. 2008;103(2):413. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Janssens K, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta1 to the bone. Endocr Rev. 2005;26(6):743. doi: 10.1210/er.2004-0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boocock GR, et al. Mutations in SBDS are associated with Shwachman-Diamond syndrome. Nat Genet. 2003;33(1):97. doi: 10.1038/ng1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rawls AS, et al. Lentiviral-mediated RNA inhibition of Sbds in murine hematopoietic progenitors impairs their hematopoietic potential. Blood. 2007;110(7):214. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-03-007112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dror Y, Freedman MH. Shwachman-Diamond syndrome: An inherited preleukemic bone marrow failure disorder with aberrant hematopoietic progenitors and faulty marrow microenvironment. Blood. 1999;94(9):3048. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000;100(1):57. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang FC, et al. Nf1-dependent tumors require a microenvironment containing Nf1+/−-and c-kit-dependent bone marrow. Cell. 2008;135(3):437. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.08.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yauch RL, et al. A paracrine requirement for hedgehog signaling in cancer. Nature. 2008;455(7211):406. doi: 10.1038/nature07275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Trimboli AJ, et al. Pten in stromal fibroblats suppresses mammary epithelial tumours. Nature. 2009;461(7267):1084. doi: 10.1038/nature08486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li L, Neaves WB. Normal stem cells and cancer stem cells:the niche matters. Cancer Res. 2006;66(9):4553. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sneddon JB, Werb Z. Location, location, location:the cancer stem cell niche. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1(6):607. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bhowmick NA, et al. TGF-beta signaling in fibroblasts modulates the oncogenic potential of adjacent epithelia. Science. 2004;303(5659):48. doi: 10.1126/science.1090922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walkley CR, et al. A microenvironment-induced myeloproliferative syndrome caused by retinoic acid receptor gamma deficiency. Cell. 2007;129(6):1097. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Walkley CR, et al. Rb regulates interactions between hematopoietic stem cells and their bone marrow microenvironment. Cell. 2007;129(6):1081. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mellibovsky L, et al. Bone remodeling alterations in myelodysplastic syndrome. Bone. 1996;19(4):401. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(96)00210-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.