Abstract

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) have been linked to oxidation and nuclear efflux of class IIa histone deacetylase 4 (HDAC4) in cardiac muscle. Here we use HDAC-GFP fusion proteins expressed in isolated adult mouse flexor digitorum brevis muscle fibers to study ROS mediation of HDAC localization in skeletal muscle. H2O2 causes nuclear efflux of HDAC4-GFP or HDAC5-GFP, which is blocked by the ROS scavenger N-acetyl-l-cysteine (NAC). Repetitive stimulation with 100-ms trains at 50 Hz, 2/s (“50-Hz trains”) increased ROS production and caused HDAC4-GFP or HDAC5-GFP nuclear efflux. During 50-Hz trains, HDAC5-GFP nuclear efflux was completely blocked by NAC, but HDAC4-GFP nuclear efflux was only partially blocked by NAC and partially blocked by the calcium-dependent protein kinase (CaMK) inhibitor KN-62. Thus, during intense activity both ROS and CaMK play roles in nuclear efflux of HDAC4, but only ROS mediates HDAC5 nuclear efflux. The 10-Hz continuous stimulation did not increase the rate of ROS production and did not cause HDAC5-GFP nuclear efflux but promoted HDAC4-GFP nuclear efflux that was sensitive to KN-62 but not NAC and thus mediated by CaMK but not by ROS. Fibers from NOX2 knockout mice lacked ROS production and ROS-dependent nuclear efflux of HDAC5-GFP or HDAC4-GFP during 50-Hz trains but had unmodified Ca2+ transients. Our results demonstrate that ROS generated by NOX2 could play important roles in muscle remodeling due to intense muscle activity and that the nuclear effluxes of HDAC4 and HDAC5 are differentially regulated by Ca2+ and ROS during muscle activity.

Keywords: reactive oxygen species, class IIa histone deacetylases 4 and 5, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidases

in skeletal muscle, myocyte enhancer factor 2 (MEF2) is a master regulator of fiber type-specific gene expression (4). The transcriptional activity of MEF2 is partially repressed by class IIa histone deacetylases (HDACs; HDACs 4, 5, 7, and 9) through the formation of HDAC-MEF2 complexes within the cell nucleus. Translocation of HDACs from the nucleus to the cytoplasm relieves the HDAC repression on MEF2. Skeletal muscle activity results in HDAC4 translocation from nucleus to cytoplasm by activating calcium-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII; Ref. 26). Phosphorylation of class IIa HDACs at specific serine residues induces the binding between HDAC and 14-3-3 that results in masking of the nuclear localization signal and exposure of the nuclear export signal, which leads to cytoplasmic translocation of HDACs. However, HDAC5 is not a substrate of CaMKII (3), lacking the unique binding sites for CaMKII, and therefore the localization of HDAC5 is not directly regulated by CaMKII or by the activity-dependent activation of CaMKII. Although HDAC5 is reported to be carried by HDAC4 through forming hetero-oligommers with HDAC4, such cotranslocation has not yet been demonstrated in skeletal muscle. HDAC5 can be phosphorylated by PKD and translocated out of slow fiber nuclei in response to α-adrenergic stimulation (21), but PKD is not present in fast fibers (21). Therefore, whether or how HDAC5 is regulated during skeletal muscle activity, especially in fast fibers, requires further investigation. The issue of possible selective or common mechanisms for nuclear cytoplasmic movements of different class IIa HDACs is important in regard to both possible distinct and redundant effects of these transcriptional regulators in muscle fiber nuclei.

In addition to phosphorylation as a mechanism for regulation of nuclear cytoplasmic distribution of HDACs, a novel reactive oxygen species (ROS) signaling pathway for regulation of class IIa HDAC translocation has been recently reported (1, 31). ROS generated during cardiac hypertrophy oxidize HDAC4 at Cys-667 and Cys-669 to form a disulfide bond, which exposes the nuclear export signal on HDAC4. This leads to the nuclear export of HDAC4 from cardiac cells. Alignment of HDAC4 with other class II HDACs shows that the two critical cysteines are conserved among HDAC4, 5, 7, and 9 (1). Therefore, we hypothesize that both HDAC4 and 5 should respond to ROS generated by skeletal muscle activity and translocate from nucleus to cytoplasm.

It is well established that contracting skeletal muscles produce ROS (13, 17, 35), although the amount of ROS production is still an open question (13). Growing evidence suggests that intracellular ROS production is required for the remodeling that occurs in skeletal muscle in response to repeated bouts of endurance exercise (12, 35). ROS is also reported to regulate redox-sensitive kinases, phosphatases, and transcription factors in skeletal muscle (35). ROS production is greatly increased in isolated mouse skeletal muscle stimulated by certain patterns of activity (41).

Both mitochondria and NADPH oxidases (NOXs) are considered as potential sources of ROS production (36), and NOX2 is expressed in skeletal muscle fibers (44). However, there are few studies on how the changes in redox status regulate gene expression in skeletal muscle (35) and whether particular subcellular sources of ROS are involved. Furthermore, no information is available on the subcellular sources and functional roles of ROS in the regulation of the nuclear/cytoplasmic distribution of HDAC4 or HDAC5 during skeletal muscle contraction.

The experiments presented in this study were designed to determine the possible roles of ROS in the regulation of HDAC4 and 5 during skeletal muscle activity. We find that during intense activity of fast muscle fibers HDAC5 is translocated out of fiber nuclei exclusively in response to NOX2-dependent ROS production. In contrast, during the same intense activity in the same type of fast fibers, HDAC4 is also translocated out of fiber nuclei, but this response is only partially dependent on NOX2 generated ROS and partly dependent on CaMK activation.

METHODS

Animals.

All animals were housed in a pathogen-free area at the University of Maryland, Baltimore. The animals were killed according to authorized procedures of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, University of Maryland Baltimore, by regulated delivery of compressed CO2 overdose followed by cervical dislocation. CD1 mice were purchased from Charles River. NOX2 knockout (KO; B6.129S6-Cybbtm1Din/J, stock number 002365) and wild-type littermate control (C57BL/6J) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory.

Infection of recombinant adenoviruses in muscle fibers.

Single muscle fibers were enzymatically dissociated from flexor digitorum brevis (FDB) muscles of female 4- to 5-wk-old CD-1 mice or from NOX2 KO and wild-type control mice and cultured as described previously (19). This age mouse is convenient due to ease of collagenase digestion of FDB muscle and for adenoviral transduction. Isolated fibers were cultured on laminin-coated glass coverslips, each glued over a 10-mm-diameter hole through the center of a plastic petri dish. Fibers were cultured in MEM containing 10% FBS and 50 μg /ml gentamicin sulfate in 5% CO2 (37°C). Virus infections were performed as previously described (19).

Microscopy, image acquisition, and analysis.

To study the localization of HDAC4-GFP or HDAC5-GFP, FDB fibers were infected with adenovirus containing HDAC4-GFP or HDAC5-GFP cDNA. Two days after infection, culture medium was changed to Ringer's solution (in mM; 135 NaCl, 4 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 10 glucose, and 1.8 CaCl2, pH 7.4). The culture dish was mounted on an Olympus IX70 inverted microscope equipped with an Olympus PflügView 500 laser scanning confocal imaging system. Fibers were viewed with an Olympus 60×/1.2 NA water immersion objective and scanned at ×2.0 zoom with constant laser power and gain.

To monitor the ROS production, fibers were loaded with 10 μM of 5-(and-6)-chloromethyl-2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (CM-H2DCFDA) for 15 min at room temperature, followed by rinse with Ringer solution and 10-min incubation. Muscle fibers were imaged by excitation at 488 nm (33). The emitted light was collected above 505 nm. For HDAC4-GFP, HDAC5-GFP, and CM-H2DCFDA experiments, the fibers were maintained and imaged at room temperature under similar conditions.

For fluorescence data from HDAC4-GFP or HDAC5-GFP, the average fluorescence of pixels within user specified areas of interest (AOI) in each image was quantified using Imaging J. The nuclear fluorescence values at each time point were normalized by the nuclear fluorescence value of 0 min of that specific muscle fiber to obtain the n/n0 ratio. Results are expressed as the means ± SE. If an image of a fiber had more than one nucleus in focus, then all the nuclei in good focus were analyzed and the multiple nuclei were treated equally.

For fluorescence data from CM-H2DCFDA, the AOI was placed in cytoplasm area (see Fig. 1A for demonstration of typical AOI). The average fluorescence of pixels in each AOI was also quantified using ImagingJ and normalized to the initial value in each AOI, to give a set of values of fluorescence-to-average resting fluorescence (F/F0) at successive time points in each fiber. Data from successive fluorescence images were fit by a straight line to obtain the slope of increasing fluorescence. Results are expressed as the means ± SE. Paired t-test was used for data from the same fiber before and after treatment.

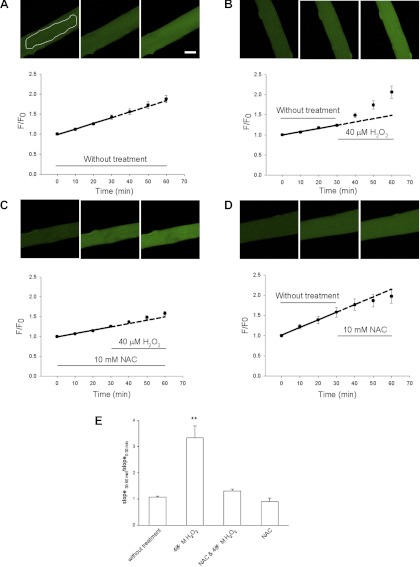

Fig. 1.

Monitoring reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation with ROS-sensitive dye 5-(and-6)-chloromethyl-2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (CM-H2DCFDA) in flexor digitorum brevis (FDB) fibers in resting condition or treated with H2O2. A and B: FDB fibers were first loaded with CM-H2DCFDA. Then, 8 fibers were imaged every 10 min for 60 min without any treatment (A), or 8 other fibers were first imaged for 30 min under control conditions and then imaged for another 30 min in the presence of 40 μM H2O2 (B). Images were quantified and fit with a linear fit to obtain slopes for the first 30 min and second 30 min, respectively, which reflects the speed of CM-H2DCF oxidation by endogenous ROS and/or H2O2. Addition of H2O2 (B) significantly increased the slope of CM-DCF fluorescence by enhancing the speed of ROS generation. Scale bar = 10 μm. White line in A demonstrates how the cytoplasmic areas of interest (AOI) is defined. C: preincubation with 10 mM N-acetyl-l-cysteine (NAC) antagonized the increase in the rate of CM-H2DCF oxidation by H2O2 addition. Data were from 5 fibers. D: addition of 10 mM NAC did not significantly change the slope of fluorescence increase. Data were from 7 fibers. Dashed lines in A–D are extrapolation of the linear fit of the first 30-min data. In A and C, the dashed lines are nearly superimposed on the measured data. However, in B the measured data are significantly higher than the extrapolation. E: ratio of slopes of the second 30 min over the first 30 min. Columns from left to right are data from A–D respectively. F/F0, fluorescence-to-average resting fluorescence. **P < 0.01.

MEF2 activity reporter assay.

For MEF2 reporter assay, cultured muscle fibers were infected with adenovirus encoding MEF2-driven luciferase reporter (45) for 48 h. The cultures were then stimulated for 1 h with 50-Hz trains. The cultures were kept in the incubator for another 24 h. Cultures were then lysed in passive lysis buffer (Promega). Luciferase activity was determined with a luciferase assay kit (Promega).

Indo-1 measurements.

Single fiber indo-1 ratiometric recordings and analysis were performed as previously described (6, 37) with minor modifications. When required, cultured FDB fibers from wild-type and NOX2 KO mice were loaded with indo-1 AM at 1 μM for 60 min at 22°C. The fibers were washed thoroughly to remove residual indo-1 AM and incubated at 22°C for another 30 min to allow dye conversion. The culture dish was mounted on an Olympus IX71 inverted microscope, and fibers were imaged with an Olympus 60×/1.20 NA water immersion objective. Excitation light was delivered by a 150-W Xenon arc-lamp and gated by a computer-controlled shutter (Vincent Associates). Fibers were illuminated at 360 ± 10 nm, and the fluorescence emitted at 405 ± 15 and 485 ± 20 nm was detected simultaneously.

Fluorescence emission from a region of interest within a fiber was selected by an image-plane pinhole and measured with an ambient temperature photomultiplier tube (Hamamatsu). Four cycles of measurements were taken for each fiber, and the results were averaged. To correct for autofluorescence and background light scatter, averages from individual unloaded fibers were subtracted from same-day experimental values. The emission signals were sampled at 2 KHz and digitized using a built-in AD/DA converter of an EPC10 amplifier and the acquisition software Patchmaster (HEKA Instruments). Field stimulation (square pulse, 14 V × 1 ms) was produced by a custom pulse generator through a pair of platinum electrodes. The electrodes were closely spaced (0.5 mm) and positioned directly above the center of the objective lens to achieve semilocal stimulation. Only fibers exhibiting reproducible and consistent responses to field stimulation of alternate polarity were used for the analysis.

Fluo-4 measurements.

High-speed fluo-4 fluorescence confocal microscopy measurements were carried out on a Zeiss LSM 5 Live system as previously described (32, 38). Fibers were loaded with fluo-4 AM (Invitrogen) at 2 μM for 30 min at 22°C. The fibers were washed thoroughly to remove residual fluo-4 AM and incubated at 22°C for another 30 min to allow dye conversion. The culture dish was mounted on a Zeiss Axiovert 200M inverted microscope on a Zeiss LSM 5 Live confocal system and viewed with a 63×/1.2 NA water immersion objective. Excitation was provided by a 488-nm laser with emission detected using a long-pass 505-nm filter. Fibers were stimulated using a protocol consisting of a single stimulus followed by a pulse train (400 ms; 100 Hz) separated by an interval of 400 ms at a set time after the start of a confocal scan. Field stimulation (square pulse, 14 V × 1 ms) was produced by a custom pulse generator through a pair of platinum electrodes. Fibers were selected based on the above inclusion criteria as well as an additional criterion of minimum fiber movement in the line scan plane to prevent movement artifacts in signals. The confocal system was operated in line scan mode, with images collected at 100 μs/line for 1.4-s acquisition time using Zeiss LSM 5 live software. Average intensity of fluorescence within selected regions of interest (ROI) was measured with a Zeiss LSM Image Examiner (Carl Zeiss). Images were background corrected by subtracting an average value recorded outside the cell. The average resting fluoresce (F0) value in each ROI before electrical stimulation was used to scale fluo-4 signals in the same ROI as ΔF/F0.

All experiments (CM-H2DCFDA or HDAC4 or 5-GFP fluorescence imaging, fiber stimulation, and calcium measurement) were carried out at room temperature, 21–23°C.

Data analysis and statistics.

All values are presented as means ± SE. Statistical significance was tested with ANOVA or t-test as appropriate. For all comparisons, the level of statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Monitoring ROS production in muscle fibers due to application of H2O2.

We first examined the increase in intracellular ROS levels in response to H2O2 addition to cultured FDB fibers by monitoring fluorescence of the ROS-sensitive dye CM-H2DCFDA. Fibers were loaded with CM-H2DCFDA and imaged every 10 min. CM-H2DCFDA is hydrolyzed to CM-DCFH in the cell, and CM-DCFH is oxidized to form highly fluorescent CM-DCF (33, 47) in the presence of the appropriate oxidant (15). The rate of change (slope) of the CM-DCF fluorescence signal is a measure of the rate of oxidative CM-DCF generation due to ROS present within the cell (22, 33).

Figure 1A presents images of a fiber maintained under control conditions for 60 min of observation. The CM-DCF fluorescence increases continuously with time, even in the absence of added H2O2, indicating a resting rate of ROS production under control conditions. To characterize the resting rate of ROS production, a group of fibers was loaded with CM-H2DCFDA and the CM-DCF fluorescence was observed for 60 min under control conditions without any addition of H2O2. Straight-line segments were fit to the CM-DCF normalized fluorescence. The average slope of the normalized fluorescence for the first 30 min and second 30 min, 1.57 ± 0.02 and 1.62 ± 0.02%/min, respectively, was not significantly different (8 FDB fibers, P > 0.05 ), indicating a constant steady rate of ROS production throughout the entire 60 min period. This is shown graphically by the dashed line in Fig. 1A (also Figs. 3 and 6), which represents an extension of the solid straight line fit to the data from 0 to 30 min to the time interval from 30 to 60 min. In another group of fibers, after the first 30-min period, 40 μM H2O2 was added to the culture dishes (Fig. 1B). The slopes of the CM-DCF fluorescence increase for the first 30 min (without H2O2) and the second 30 min (with H2O2) were significantly different (0.81 ± 0.06 and 2.73 ± 0.47%/min, respectively; 8 FDB fibers; P < 0.01). The increase in fluorescence above the dashed extrapolation of the solid line fit to the first 30 min demonstrates that addition of 40 μM H2O2 effectively increased ROS production in the cultured fibers. In the presence of 10 mM of added ROS scavenger N-acetyl-l-cysteine (NAC), addition of H2O2 to the culture dishes did not change the slope of CM-DCF fluorescence (Fig. 1C; 0.84 ± 0.07 and 1.09 ± 0.13%/min for the first 30 min and second 30 min, respectively; 5 FDB fibers; P > 0.05). In a separate group of FDB fibers, we tested the effects of NAC on the slope of CM-DCF fluorescence without other treatment (Fig. 1D). After 30 min at rest, 10 mM NAC were added but the rate of CM-DCFH oxidation was not significantly changed (1.49 ± 0.29 and 1.15 ± 0.12%/min, respectively, for the first and second 30 min; 7 FDB fibers; P > 0.05).

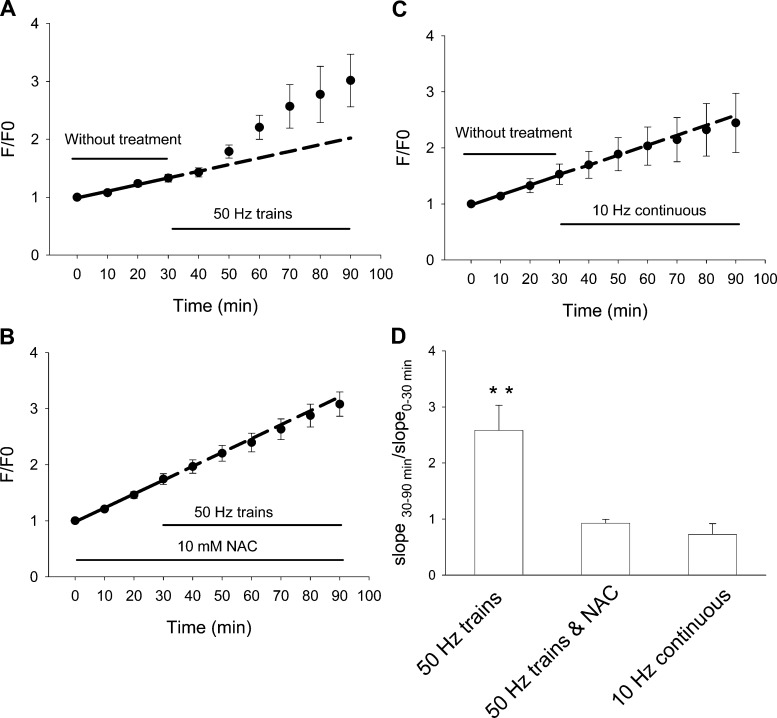

Fig. 3.

Effects of 50-Hz train or 10-Hz continuous stimulation on the production of endogenous ROS. A: FDB fibers were loaded with ROS sensitive dye CM-H2DCFDA and monitored by imaging every 10 min. Fibers were first monitored for 30 min without stimulation. Electrical stimulation of 50-Hz trains for 60 min significantly increased the rate of ROS generation compared with the 30-min resting period of the same group of muscle fibers. Data were from 7 FDB fibers. B: same pattern of electrical stimulation was applied to FDB fibers preincubated with 10 mM NAC for 30 min. Electrical stimulation for 60 min did not result in significant increase of the slope of linear fit, suggesting that there is no significant increase in ROS generation. Data were from 6 FDB fibers. C: FDB fibers were loaded with CM-H2DCFDA and monitored by imaging every 10 min, while continuous electrical stimulation at 10 Hz for 60 min. There is no significant difference in slope of fluorescence increase in the 60-min stimulation period comparing to the 30-min resting period, suggesting the electrical stimulation at 10 Hz continuously does not generate more ROS than without stimulation. Data were from 6 FDB fibers. Dashed lines in A–C are extrapolation of the linear fit of the first 30 min without electrical stimulation. In B and C, the dotted lines are nearly superimposed on the measured data. However, in A the measured data are significantly higher than the extrapolation. D: ratio of slopes of the 60-min stimulation period over the 30-min resting period. Columns from left to right are data from A–C, respectively. **P < 0.01.

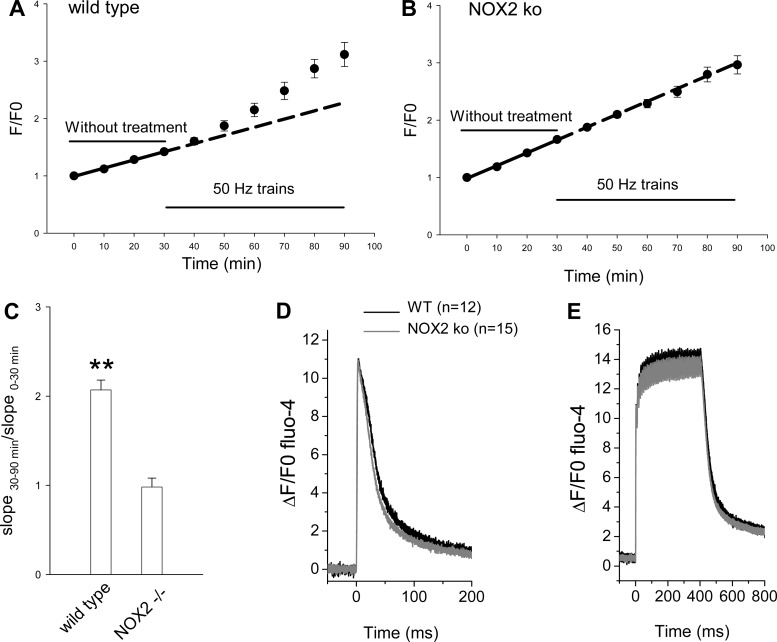

Fig. 6.

Measuring ROS production and calcium transients in FDB fibers from NOX2 knockout (KO) mice or wild-type control mice. FDB fibers from wild-type control (A) or from NOX2 KO (B) mice were loaded with ROS sensitive dye CM-H2DCFDA and monitored by imaging every 10 min. Fibers were first monitored for 30 min without stimulation. Electrical stimulation of 50-Hz trains for 60 min significantly increased the rate of ROS generation compared with the 30-min resting period in control fibers (A), but not in NOX2 KO fibers (B). Data were from 12 FDB fibers for A and 16 fibers for B, respectively. C: ratio of slopes of the 60 min stimulation period over the 30-min resting period. **P < 0.01. D and E: fibers from NOX2 KO mice or from wild-type mice have similar calcium transients. D: superimposed typical single calcium transients from wild-type FDB fiber (black) or from NOX2 KO FDB fiber (gray) with calcium sensitive dye fluo-4. Data are shown as ΔF/F0. E: fibers from wild-type or NOX2 KO were stimulated with by a pulse train (400 ms at 100 Hz) and the resulting calcium transients were recorded with fluo-4. Calcium transients recorded from wild-type or NOX2 KO showed similar peak values and decay rates.

As judged from the rate of change of CM-DCF fluorescence, the normalized rate of CM-DCF production varied considerably from experiment to experiment, even under control conditions. To quantify the effects of fiber manipulation on ROS production, we normalized the slope of CM-DCF fluorescence during the test period to the slope determined in the same fiber in the control period (Fig. 1E). When no change in conditions was made (Fig. 2A), the ratio of the slope in the second to the first interval was 1.07 ± 0.03 (Fig. 1E, first bar), not significantly different than 1.00 (P > 0.05). When H2O2 was applied in the second interval, the slope increased to 3.33 ± 0.46 of control (Fig. 1E, second bar from left; P < 0.01), and this increase was eliminated in the presence of NAC during both the control and test intervals (Fig. 1E, third bar from left). NAC itself caused no significant change in the rate of CM-DCF fluorescence increase (0.90 ± 0.13; Fig. 1E, fourth bar; P > 0.05).

Fig. 2.

Effects of H2O2 on the nuclear efflux of class IIa histone deacetylase 4 (HDAC4)-GFP and HDAC5-GFP in FDB fibers. A: FDB fibers were infected with HDAC4-GFP and treated with 40 μM H2O2. HDAC4-GFP was concentrated in the nucleus before the application of H2O2 (0 min). H2O2 resulted in net nuclear to cytoplasmic translocation of HDAC4-GFP (60 min). Data are presented as ratio of nuclear HDAC4-GFP mean pixel fluorescence at different time point/nuclear mean pixel fluorescence at 0 min from the same individual fiber. Data were from 10 nuclei of 5 FDB fibers. Scale bar = 10 μm. B: response of HDAC4 to H2O2 was blocked by exogenous ROS scavenger NAC. NAC was added 60 min before the addition of H2O2. Data were from 12 nuclei of 6 FDB fibers. C: H2O2 caused a decline in nuclear HDAC5-GFP in a way similar to HDAC4-GFP. Data were from 12 nuclei of 5 FDB fibers. D: response of HDAC5 to H2O2 was blocked by NAC. Data were from 12 nuclei of 6 FDB fibers. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Application of H2O2 causes HDAC4-GFP and HDAC5-GFP translocation from nucleus to cytoplasm.

We next examined whether increasing intracellular ROS by addition of H2O2 to the Ringer solution has any effects on the nuclear localization of HDAC4-GFP or HDAC5-GFP fusion protein constructs expressed in adult skeletal muscle fibers. Under control conditions, HDAC4-GFP is concentrated in FDB fiber nuclei (Fig. 2A). During the first 30 min no reagent was added, and the nuclear HDAC4-GFP remained constant (Fig. 2A, open circles, −30 and 0 min). Subsequent application of H2O2 (40 μM) caused a continuous decline in nuclear HDAC4-GFP (Fig. 2A). The nuclear mean pixel fluorescence declined by 20 ± 2% (P < 0.01) by the end of the 60-min observation period in the presence of H2O2. We also examined the effects of H2O2 on the nuclear efflux of HDAC5-GFP. As reported previously (20), HDAC5-GFP is more highly localized in muscle fiber nuclei under resting conditions than is HDAC4 (mean value of n/c for HDAC4-GFP from 10 nuclei from 5 fibers = 2.87 ± 0.24; mean value of n/c for HDAC5-GFP from 12 nuclei from 6 fibers = 6.22 ± 0.41). As was the case for HDAC4, addition of H2O2 also caused a net nuclear efflux of HDAC5-GFP (Fig. 2C, open circles). The nuclear mean pixel fluorescence from HDAC5-GFP declined by ∼22 ± 3% (P < 0.01) by the end of the 60-min observation period in the presence of H2O2.

We then investigated the effects of NAC on the H2O2-induced nuclear efflux of HDAC4 and 5-GFP. Under resting conditions before H2O2 addition, NAC has no effects on the localization of HDAC4-GFP (Fig. 2B) or HDAC5-GFP (Fig. 2D). In the presence of NAC, the H2O2-induced nuclear efflux of both HDAC4-GFP and of HDAC5-GFP was completely blocked (Fig. 2, B and D), establishing that oxidation underlies the effect of applied H2O2 on nuclear efflux of HDAC4 and 5-GFP.

Intense FDB muscle fiber activity increases intracellular ROS.

Skeletal muscle contraction can generate ROS (33, 41). We thus tested whether 100-ms trains at 50 Hz with 2 trains/s (hereafter referred to as “50-Hz trains”), a relatively intense stimulation pattern previously shown to generate ROS in mouse extensor digitorum longus (EDL) muscle bundles (41), can significantly increase the rate of CM-DCFH oxidation relative to the resting rate in our single FDB fiber culture system. CM-DCF fluorescence was first recorded every 10 min during a 30-min control period without stimulation. Then, the fibers were repetitively electrically stimulated with the 50-Hz train protocol, a relatively intense pattern of activity. CM-DCF fluorescence was recorded every 10 min (between trains of fiber stimulation) during a 60-min stimulation period. During the 30-min resting period, the CM-DCF fluorescence increased constantly with a slope of 1.15 ± 0.24%/min (Fig. 3A, solid line) During the 60-min stimulation period, the fluorescence increased significantly faster, with a slope of 3.08 ± 0.10%/min (7 fibers, P < 0.01). This indicates that the simulation pattern used here (50-Hz trains) causes generation of more ROS than is produced under resting conditions in our FDB cultures. This increase is clearly seen by comparison of the extrapolation (Fig. 3A, dashed line) of the fit to the 30-min control period to the period of fiber stimulation. The rate of increase of CM-DCF fluorescence during fiber stimulation clearly exceeds the extrapolated control rate of increase.

In another group of FDB fibers, we tested whether NAC can block the increase in the slope of CM-DCF fluorescence during 50-Hz train electrical stimulation. In the presence of NAC, the slopes for the 30-min resting period and for the 60 min with 50-Hz train electrical stimulation were not significantly different (2.48 ± 0.24 and 2.24 ± 0.23%/min, respectively; 6 FDB fibers; P > 0.05). As shown in Fig. 3B, preincubation with the anti oxidant NAC essentially eliminated the difference in the slopes between the 30-min resting period and the 60-min electrical stimulation period.

We also measured the ROS generation produced by 10-Hz continuous stimulation. Figure 3C shows that in the first 30-min resting period, the slope of the normalized fluorescence was 1.79 ± 0.63%/min. In the following 60 min, when the same group of fibers were stimulated continuously at 10 Hz, the slope of the normalized fluorescence was not significantly different (1.53 ± 0.60%/min; 6 FDB fibers; P > 0.05). This indicates that 10-Hz continuous electrical stimulation does not produce more ROS than is produced at rest. In this regard, it is of interest to note that both 50-Hz train and 10-Hz continuous stimulation deliver the same overall number of pulses averaged over time (i.e., 10 pulses over a 1-s period), but grouped differently.

In Fig. 3D, we normalized the slope of CM-DCF fluorescence during the 60-min muscle stimulation period in each fiber to the slope determined in the same fiber in the control period. When 50-Hz trains were applied in the second interval, the slope increased to 2.58 ± 0.45 times that of control (Fig. 3D, left bar; P < 0.01 compared with slopes of before stimulation). This increase was eliminated in the presence of NAC during both the control and stimulation intervals (Fig. 3D, middle bar; P > 0.05 compared before stimulation). The 10-Hz continuous stimulation did not significantly change the rate of CM-DCF fluorescence increase (Fig. 3D, right bar; P > 0.05 compared with before stimulation).

HDAC5 nuclear efflux responds only to a muscle activity pattern that generates significant amounts of ROS.

Next, the 50-Hz train stimulation pattern was applied to FDB cultures expressing HDAC5-GFP, and HDAC5-GFP nuclear efflux was monitored. The nuclear level of HDAC5-GFP declined continuously during 50-Hz train stimulation (Fig. 4A, circles), dropping by 18 ± 5% after 60 min of 50-Hz train stimulation.

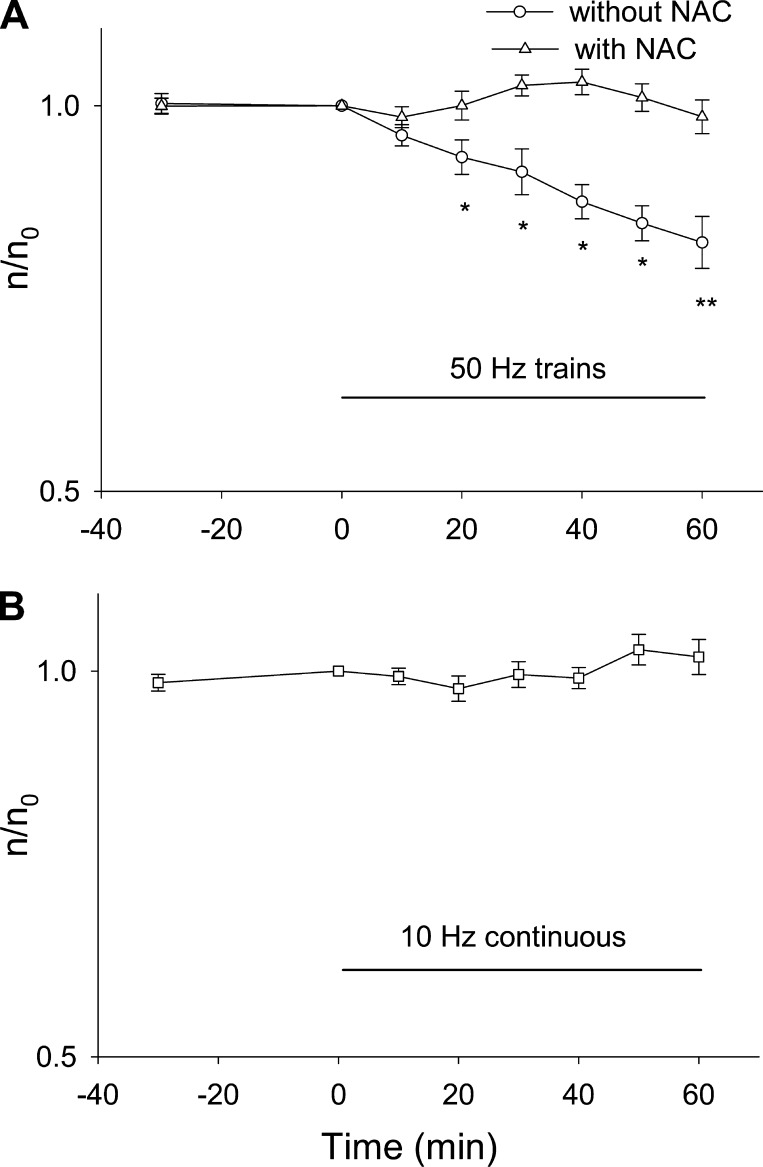

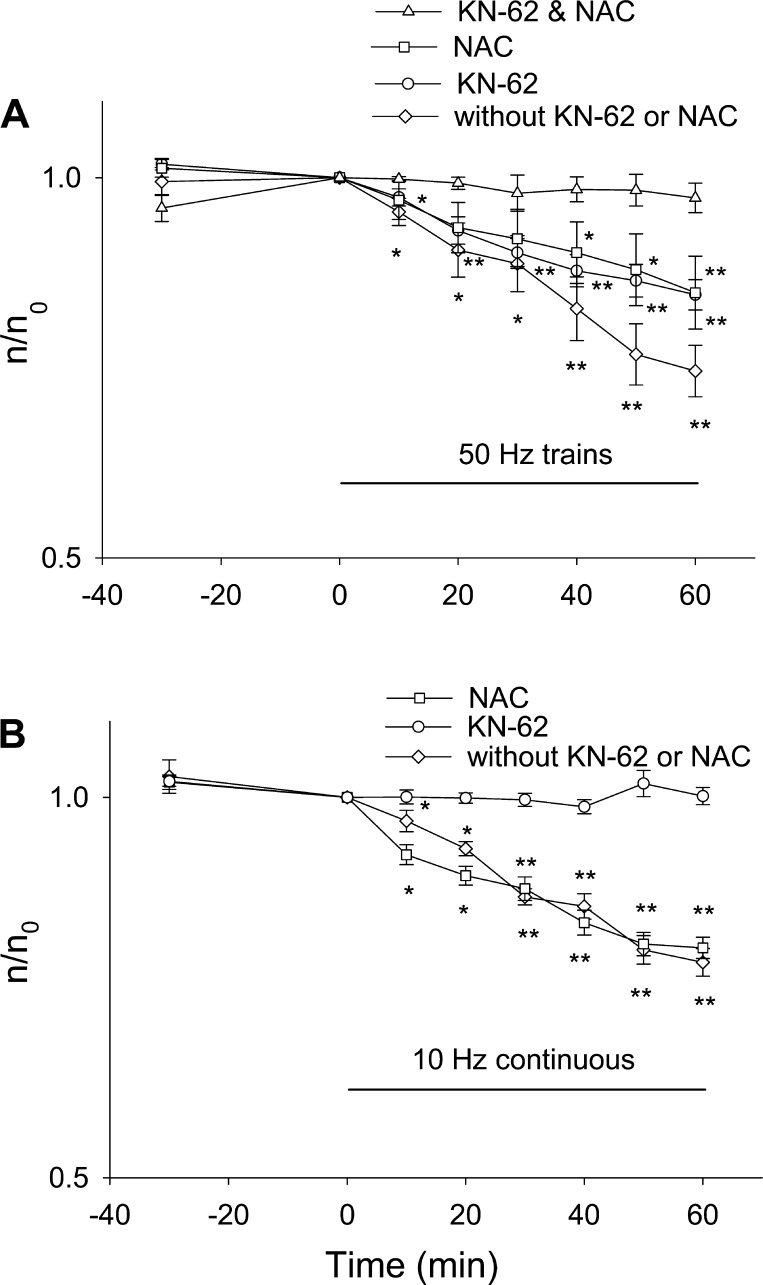

Fig. 4.

Effects of electrical stimulation and ROS production on HDAC5-GFP nuclear efflux. A: FDB fibers expressing HDAC5-GFP were electrical stimulated with 50-Hz trains. Stimulation resulted nuclear to cytoplasmic translocation of HDAC5-GFP. Data were from 9 nuclei of 5 FDB fibers. If fibers expressing HDAC5-GFP were pretreated with NAC, electrical stimulation with 50-Hz trains did not result in nuclear efflux of HDAC5-GFP. Data were from 12 nuclei of 6 FDB fibers. B: FDB fibers expressing HDAC5-GFP were stimulated with 10 Hz continuously. This pattern of muscle activity did not cause nuclear efflux of HDAC5-GFP. Data were from 12 nuclei of 6 FDB fibers. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

It was shown in Fig. 3, A and B, that the 50-Hz train stimulation pattern generates more ROS than is produced under resting conditions and that this increase in ROS production can be eliminated by preexposure to NAC. To test for a possible role of ROS in the HDAC5-GFP nuclear efflux during 50-Hz train stimulation, in another group of FDB fibers expressing HDAC5-GFP, we first incubated fibers with NAC for 30 min after which the fibers were stimulated with the same 50-Hz train pattern. , In the presence of NAC (Fig. 4A, triangles), electrical stimulation with 50-Hz train for 60 min has no effects on the nuclear level of HDAC5-GFP (14 nuclei from 10 FDB fibers). Thus, compared with the 18% decrease of nuclear HDAC5-GFP in the absence of NAC, the presence of NAC essentially abolished the effects of muscle activity on HDAC5-GFP nuclear efflux. This demonstrates that ROS generated by muscle activity played an essential role in HDAC5-GFP nuclear efflux.

In another group of HDAC5-GFP-expressing FDB fibers, we tested the effects of 10-Hz continuous stimulation, which does not increase ROS production (Fig. 3C), on the nuclear efflux of HDAC5-GFP. As noted above, 10-Hz continuous stimulation delivers the same number of stimuli as the 50-Hz train pattern but grouped differently. However, during the 60-min 10-Hz continuous stimulation, there is no noticeable decrease in nuclear HDAC5-GFP (Fig. 4B; 1.8 ± 0.9% decline; P > 0.05 for significant difference from 0 min). Taken together, these results show that a muscle activity pattern that does not increase ROS production will not promote HDAC5-GFP nuclear efflux, further strengthening the conclusion that HDAC5-GFP nuclear efflux during fiber stimulation exclusively depends on ROS produced during muscle activity.

HDAC4-GFP nuclear efflux responds to both ROS production and CaMK activation during repetitive fiber stimulation.

Previously, we reported that both “10-Hz train” (one 5-s duration train at 10 Hz delivered every 50 s) electrical stimulation and 1-Hz continuous stimulation did not lead to any HDAC5 nuclear efflux but did cause nuclear efflux of HDAC4-GFP and that the HDAC4-GFP nuclear efflux was accomplished via activation of CaMK II (20). However, a possible role of ROS in HDAC4 nuclear efflux was not investigated. We therefore now tested the effects of 50-Hz train stimulation, a muscle activity pattern that increases ROS production in FDB cultures (Fig. 3A), on the nuclear efflux of HDAC4-GFP. Figure 5A (circles) shows that 60-min muscle activity with 50-Hz train stimulation promoted continuous HDAC4-GFP nuclear efflux throughout the stimulation, with HDAC4-GFP nuclear fluorescence declining by 25 ± 5% (significantly different from 0 min; P < 0.01) by the end of the 60-min stimulation period.

Fig. 5.

Effects of electrical stimulation, ROS production, and calcium-dependent protein kinase (CaMK) activation on the nuclear efflux of HDAC4-GFP. A: FDB fibers expressing HDAC4-GFP were electrical stimulated with 50-Hz trains. Stimulation caused nuclear efflux of HDAC4-GFP during the 60 min period of observation. Data were from 8 nuclei of 5 FDB fibers. FBD fibers expressing HDAC4-GFP were incubated in 10 mM NAC for 30 min before electrical stimulation was started. Treatment with NAC decreased the rate of nuclear efflux of HDAC4-GFP triggered by electrical stimulation. Data were from 9 nuclei of 5 FDB fibers. FBD fibers expressing HDAC4-GFP were incubated in 5 μM KN-62 for 30 min before electrical stimulation was started. KN-62 decreased the rate of nuclear efflux of HDAC4-GFP triggered by electrical stimulation. Data were from 11 nuclei of 7 FDB fibers. If FDB fibers were incubated with both NAC and KN-62, the nuclear efflux of HDAC4-GFP was completely blocked. Data were from 9 nuclei of 6 FDB fibers. B: FDB fibers expressing HDAC4-GFP were stimulated with 10 Hz continuously, which caused a net nuclear efflux of HDAC4-GFP. Data were from 10 nuclei of 6 FDB fibers. Preincubation with 10 mM NAC did not affect the nuclear efflux caused by 10-Hz continuous stimulation. Data were from 16 nuclei of 8 FDB fibers. CaMK inhibitor KN-62 antagonized the nuclear efflux of HDAC4-GFP caused by 10-Hz continuous stimulation. Data were from 13 nuclei of 6 FDB fibers. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Since 50-Hz train stimulation generates ROS in these fibers (Fig. 3A), we next investigated whether ROS produced by muscle activity plays any roles in the nuclear efflux of HDAC4-GFP induced by 50-Hz train stimulation by using the ROS scavenger NAC. In the presence of 10 mM NAC, 50-Hz train stimulation still can cause continuous nuclear efflux of HDAC4-GFP during stimulation (Fig. 5A, squares), with nuclear HDAC4 declining by 15 ± 3% by the end of 60-min 50-Hz train stimulation, which was significantly less decline than in the absence of NAC. Thus NAC decreased, but did not completely block, the nuclear efflux of HDAC4-GFP during 50-Hz train stimulation (Fig. 5A, circle and squares).

KN-62 is a widely used inhibitor of CaMK that was found to completely eliminate the nuclear efflux of HDAC4-GFP caused by 10-Hz train electrical stimulation in a previous study from our laboratory (20). Here, we found that KN-62 only partially blocked the nuclear efflux in response to 50-Hz trains (Fig. 5A, circles). After 60 min of 50-Hz train stimulation in the presence of KN-62, nuclear HDAC4-GFP concentration was decreased significantly less than in control (P < 0.01) but was also significantly decreased compared with the starting level (P < 0.01). This is different from the previously observed effects of KN-62 on the nuclear efflux due to 10-Hz train stimulation or 1-Hz continuous stimulation, where KN-62 completely eliminated HDAC4 nuclear efflux (20). This suggests that different muscle activity patterns may promote HDAC4 nuclear efflux through different mechanisms, with 10-Hz trains or 1-Hz continuous stimulation acting on HDAC4 nuclear efflux exclusively via CaMK but with 50-Hz trains acting on HDAC4 via both mechanisms. Treatment with a combination of both KN-62 and NAC fully abolished the nuclear efflux of HDAC4-GFP by 50-Hz trains (Fig. 5A, triangles; 60-min value not significantly different from 0; P > 0.05), showing that both ROS and CaMK are involved in the nuclear efflux of HDAC4-GFP caused by 50-Hz trains.

We next tested the effects of 10-Hz continuous stimulation, which delivers the same average number of pulses per minute as 50-Hz trains but with the pulses grouped differently, on HDAC4-GFP nuclear efflux. The 10-Hz continuous stimulation also caused nuclear efflux of HDAC4-GFP (Fig. 5B, circles), with nuclear concentration declining by 16 ± 4% after 60 min. However, this decline in nuclear HDAC4-GFP fluorescence in response to 10-Hz continuous stimulation is not blocked by 10 mM NAC incubation (Fig. 5B, squares, which is not significantly from the percent decline without any blockers; P > 0.05) but is completely eliminated by the CaMK inhibitor KN-62 (Fig. 5B, triangles). The change in nuclear fluorescence during 10-Hz continuous stimulation in the presence of KN-62 was not significantly different from 0 min (P > 0.05). Taken together, the current results suggest that 10-Hz continuous stimulation, which activates CaMK without affecting ROS production, enhances HDAC4-GFP nuclear efflux exclusively through HDAC4 phosphorylation by CaMK but has no effect on the nuclear movements of HDAC5. Thus in the absence of ROS generation, fiber activity can promote HDAC4 but not HDAC5 nuclear efflux. The latter requires ROS production, which is not detectable during the 10-Hz train stimulation.

NOX2 is the main source of ROS generated by intense muscle activity.

Since NAC indiscriminately scavenges ROS and reactive nitrogen species from various sources, we further examined the specific source of the ROS that generates ROS dependent HDAC nuclear efflux due to intense (50-Hz trains) muscle activity. NOX are considered as a potential intracellular source of ROS in skeletal muscle (both normal and dystrophic; Refs. 36, 42, 44). FBD fibers were isolated from NOX2 KO mice (as well as from matched wild-type mice) and were cultured and loaded with CM-H2DCFDA. Electrical stimulation with 50-Hz trains resulted in significant increase of CM-DCF fluorescence slope in muscle fibers from wild-type control mice (Fig. 6, A and C, left bar; slope increased from 1.36 ± 0.39 to 2.43 ± 0.24%/min; P < 0.01), which is similar to results from CD-1 mouse (Fig. 3, above). In contrast, in cultures from NOX2 KO mice, the same pattern of electrical stimulation did not change the slope of fluorescence increase during the 60-min stimulation interval compared with the 30-min resting period (Fig. 6, B and C, right bar; slope was 1.82 ± 0.16 in control and 1.85 ± 0.19%/min during stimulation; P > 0.05). These results with muscle from NOX KO mice strongly suggest that NOX2 is the source of ROS production during stimulation with 50-Hz trains in FDB muscle fibers under our culture and experimental conditions.

We also examined whether there were any differences in calcium handling in NOX2 KO mice compared with wild-type controls. Using indo-1-loaded fibers, we found that there was no difference in indo-1 fluorescence ratio in resting fibers (0.76 ± 0.01 in 24 wild type and 0.72 ± 0.01 in 18 NOX2 KO; P > 0.05) indicating that the resting Ca2+ concentration was the same in both types of fibers. As shown in Fig. 6, Ca2+ transients in response to both single action potentials (Fig. 6D) and during tetanic contraction in response to 400-ms trains of action potentials at 100 Hz (Fig. 6E) measured with fluo-4 were very similar. For the single action potential, there was no significant difference between NOX2 KO and wild-type control fibers in either peak of calcium transient (11.3 ± 0.5 in 12 wild type and 11.1 ± 0.5 in 15 NOX2 KO; P = 0.8) or the time to peak (3.42 ±0.28 in the wild type and 3.01 ± 0.17 in the NOX2 KO; P = 0.2), but the half duration was slightly shorter in the NOX2 KO fibers (33.0 ± 1.1 in the wild type and 27.0 ± 1.3 in the NOX2 KO; P = 0.003). Thus the differences observed for ROS generation in NOX2 KO fibers compared with wild-type control fibers were not due to changes in resting Ca2+ or Ca2+ transients in the NOX2 KO fibers.

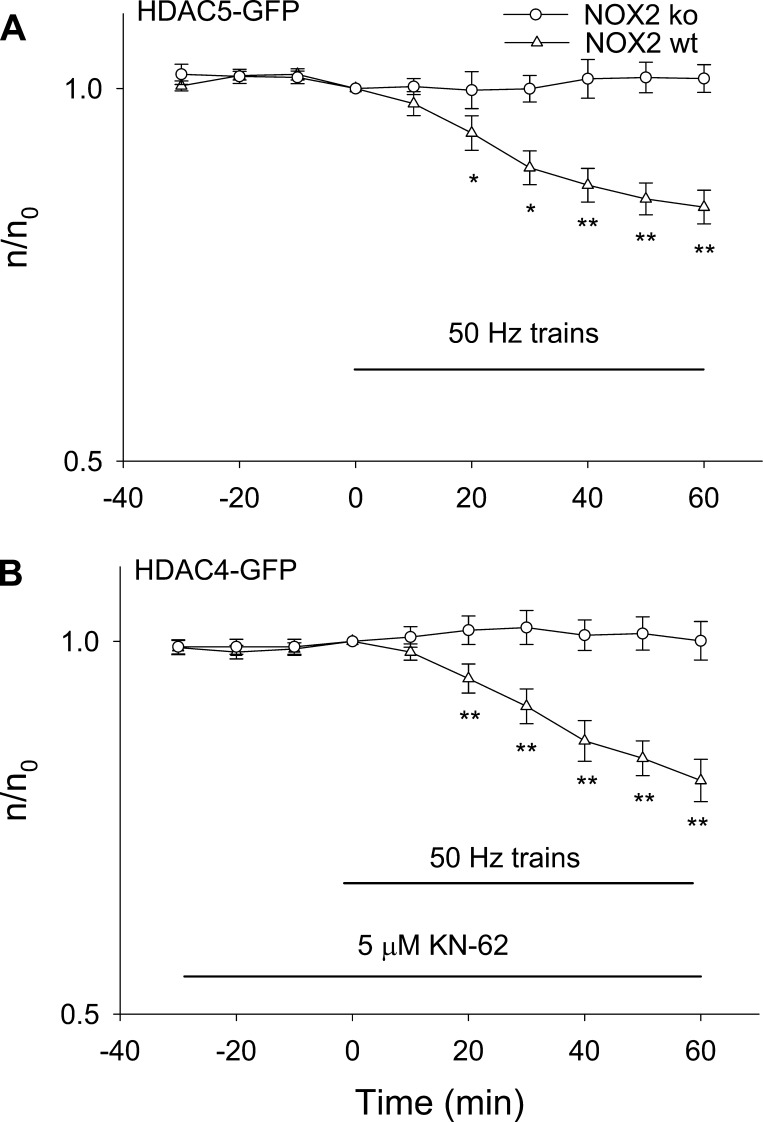

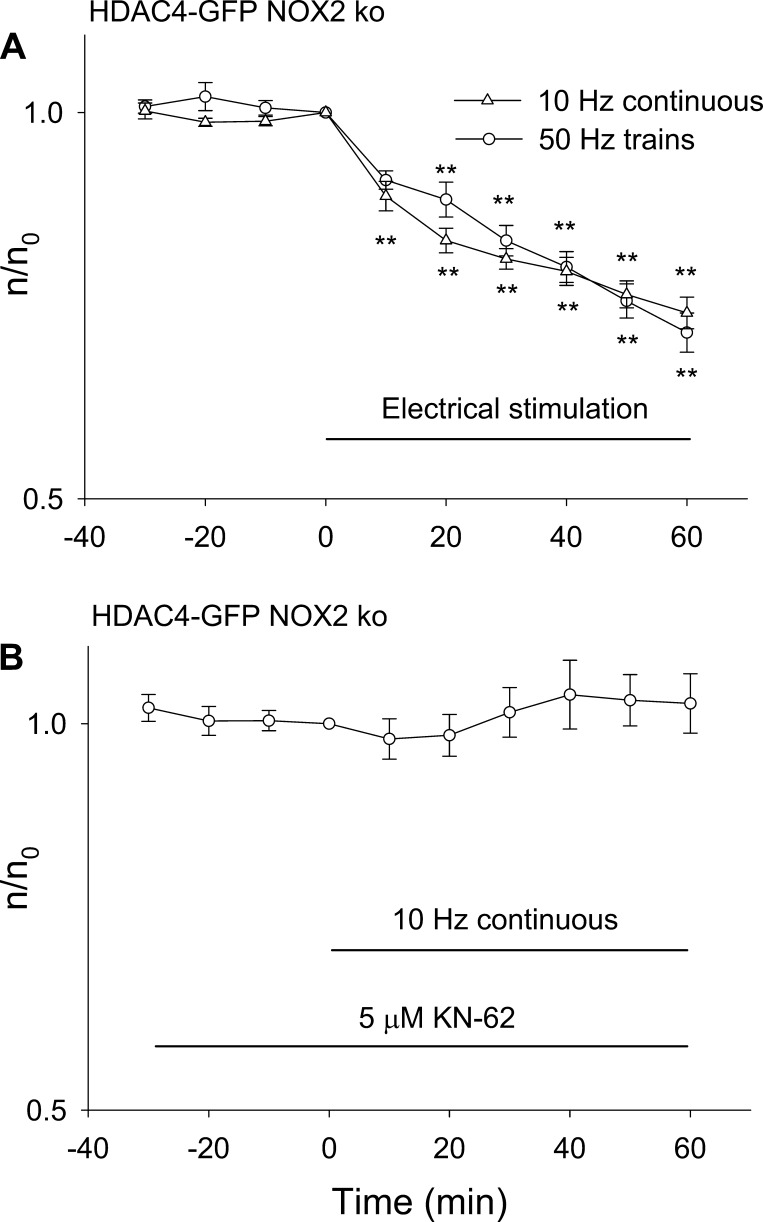

Next, we expressed HDAC4-GFP or HDAC5-GFP in FDB fibers either from NOX KO mice or from matched wild-type mice. Figure 7A shows that 50-Hz trains resulted in nuclear efflux of HDAC5-GFP in fibers from wild-type control mice but that the efflux of HDAC5-GFP was completely lacking in the fibers from NOX KO mice, with the relative nuclear fluorescence not significantly different from 0 min after 60-min stimulation (P > 0.05). For the experiments on HDAC4-GFP (Fig. 7B), fibers from wild-type or NOX KO mice were first incubated with CaMK inhibitor KN-62 for 30 min to eliminate any effects of CaMK activation during stimulation. The fibers were then stimulated with 50-Hz trains. In the presence of KN-62, which selectively eliminates CaMK activation, 50-Hz train stimulation again led to nuclear efflux of HDAC4-GFP in wild-type fibers but not in NOX KO fibers. Taken together, our results suggest that ROS generated by NOX2 is the main source of ROS production during 50-Hz train muscle activity and that ROS generated by NOX2 causes nuclear efflux of HDAC4 and 5.

Fig. 7.

Effects of 50-Hz train stimulation on HDAC5-GFP or HDAC4-GFP nuclear efflux in NOX2 KO mice and wild-type control mice. A: FDB fibers from NOX2 KO mice or control mice expressing HDAC5-GFP were stimulated. Stimulation in fibers from control mice enhanced nuclear efflux of HDAC5-GFP, but not in fibers from NOX2 KO mice. Data were from 11 nuclei of 9 FDB fibers for NOX2 KO mice. Data were from 11 nuclei of 9 FDB fibers for control mice. B: FDB fibers from NOX2 KO mice or control mice expressing HDAC4-GFP were first treated with KN-62, then stimulated. Stimulation in fibers from control mice enhanced nuclear efflux of HDAC4-GFP but not in fibers from NOX2 KO mice. Data were from 12 nuclei of 8 FDB fibers for NOX2 KO mice. Data were from 11 nuclei of 7 FDB fibers for control mice. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Based on the results in Fig. 7, the NOX2 KO fibers provide a means of characterizing the Ca2+-dependent nuclear efflux of HDAC4 in the absence of ROS-dependent contributions. In the NOX2 KO fibers, both 50-Hz train and 10-Hz continuous stimulation gave the same rate of decline of nuclear HDAC4, indicating that CaMK was already maximally activated by the 10-Hz continuous stimulation and that concentrating the pulses into 50-Hz trains caused no further HDAC4 nuclear efflux (Fig. 8A). This is in contrast to wild-type fibers, where 50-Hz trains activate NOX2-dependent ROS generation, resulting in a component of HDAC4-GFP nuclear efflux dependent on ROS production, which is not seen with 10-Hz continuous stimulation (Fig. 5). In NOX2 KO fibers in the presence of pharmacological block of CaMK by KN-62, neither 10-Hz continuous stimulation (Fig. 8B) nor 50-Hz train stimulation (Fig. 7B, open circles) causes nuclear efflux of HDAC4-GFP.

Fig. 8.

Effects of 50-Hz train or 10-Hz continuous stimulation on HDAC4-GFP nuclear efflux in NOX2 KO mice. A: FDB fibers from NOX2 KO mice were stimulated with 50-Hz trains or with 10 Hz continuously. Both patterns of stimulation caused similar nuclear efflux of HDAC4-GFP. Data were from 8 nuclei of 6 fibers for 50-Hz train and 12 nuclei from 6 fibers for 10-Hz continuous stimulation. B: 10-Hz continuous stimulation did not result in significant nuclear efflux of HDAC4-GFP if muscle fibers from NOX2 KO mice were incubated with 5 μM KN-62. Data were from 9 nuclei of 5 fibers. **P < 0.01.

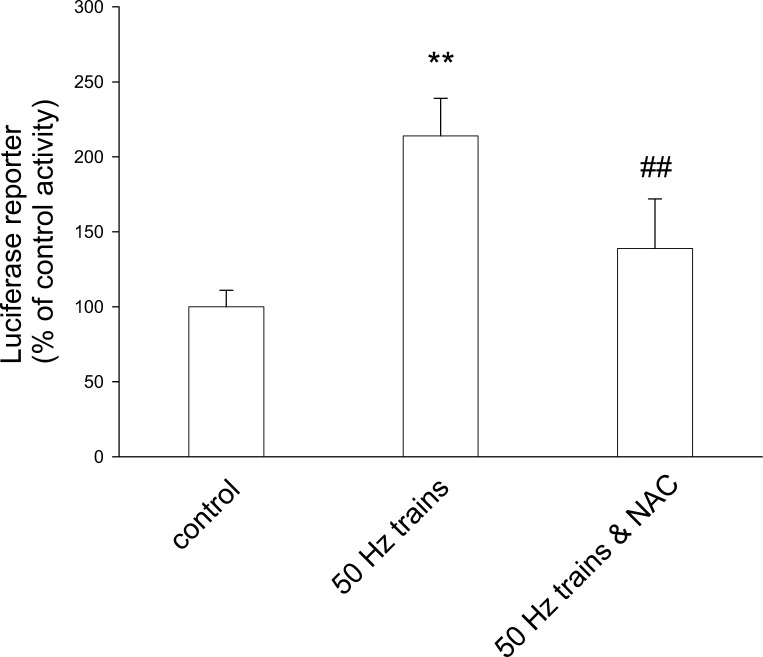

ROS production by muscle activity activates MEF2.

Stimulation of FDB cultures also resulted in changes in expression of a MEF2-element-driven luciferase reporter construct. FDB fibers were infected with adenovirus containing a luciferase cDNA driven by a promoter containing six consecutive MEF2 elements (45) and incubated for 2 days. Fibers were stimulated for 1 h with 50-Hz trains and then cultured for another 24 h. This stimulation caused the luciferase activity in fiber culture extracts to increase to 2.14 times compared with extracts from unstimulated fiber cultures (Fig. 9; P < 0.01). Pretreatment with 10 mM NAC partially blocked the enhancement of MEF2 reporter activity induced by stimulation (Fig. 9), indicating that at least part of the increase in MEF2-driven luciferase reporter activity during intense muscle activity was mediated by ROS.

Fig. 9.

Effects of electrical stimulation and NAC on MEF2 activity. Luciferase activity was increased in fibers infected with MEF2-luciferase reporter and stimulated with 50-Hz trains (middle bar; **P < 0.01 compared with control). The presence of 10 mM NAC partially blocked the increase in luciferase activity stimulated with electrical pulses (right bar, ##P < 0.01 compared with stimulated in the absence of NAC). Results represent triplicate measurements from each of four independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

We (20) have previously reported that both 10-Hz train and 1-Hz continuous electrical stimulation of FDB muscle fibers causes nuclear efflux of HDAC4, which can be inhibited by the CaMK inhibitor KN-62, but that the same patterns of electrical stimulation had little or no effect on the subcellular distribution of HDAC5 (20). The present work was therefore initiated to identify and characterize alternative pathways that might give rise to HDAC5 nuclear efflux in fast skeletal muscle fibers. Sparked by the recent reports that ROS can regulate distribution of HDAC4 in cardiac cells (1, 31), we now investigated the effects of ROS on the localization of HDAC4 and HDAC5 in skeletal muscle and here present several novel results. Under the conditions of our experiments on isolated adult FDB muscle fibers, we find that 1) ROS promotes the nuclear efflux of both HDAC4 and HDAC5 when expressed as GFP fusion proteins in isolated muscle fibers; 2) 50-Hz train stimulation causes an increase in ROS production that leads to nuclear efflux of both HDAC4 and 5; 3) HDAC4 and HDAC5 respond to electrical stimulation differentially: HDAC5 responds only to stimulation patterns (e.g., 50-Hz trains) generating an increased rate of ROS production, whereas HDAC4 responds both to an intense stimulation pattern generating increased rate of ROS production (50-Hz trains), as well as to less intense stimulation patterns (10-Hz trains and 1- and 10-Hz continuous) that do not increase ROS production but that do activate CaMK; 4) the ROS production that leads to HDAC4 and 5 nuclear efflux during intense fiber stimulation patterns requires NOX2; but 5) NOX2 does not modulate resting Ca2+ or the amplitude of the Ca2+ transients due to single action potentials or during trains of action potentials . These results clearly implicate ROS and NOX2 in the intense activity-dependent nuclear efflux of HDAC4 and 5 in isolated FDB muscle fibers under the conditions of our experiments. The extent to which ROS and NOX2 are also involved and activated by intense activity in muscle fibers in muscles in vivo remains to be determined.

Production of ROS cause both HDAC4 and HDAC5 nuclear efflux.

Two recent elegant reports (1, 31) studied the role of redox-dependent pathways in the regulation of class II HDACs and cardiac hypertrophy. They found that Cys-667 and Cys-669 in HDAC4 could be oxidized by ROS generated by hypertrophic stimuli. Such oxidation led to the formation of intramolecular disulfide bonds and exposed the nuclear export signal in HDAC4. The two cysteines in HDAC4 are conserved in other class II HDAC members. The redox pathway for regulation of HDAC4 is reported to be independent of the phosphorylation-dependent pathway for HDAC regulation that has been extensively studied both in cardiac (3) and skeletal (20, 27) muscles. Both cysteines are conserved in HDAC5 as Cys-696 and Cys-698. In our study with skeletal muscle, both HDAC4-GFP and HDAC5-GFP respond with nuclear efflux due to an increased rate of ROS production either generated by addition of H2O2 to the bath solution or by intense electrical stimulation.

HDAC4 and HDAC5 respond differentially to electrical stimulation.

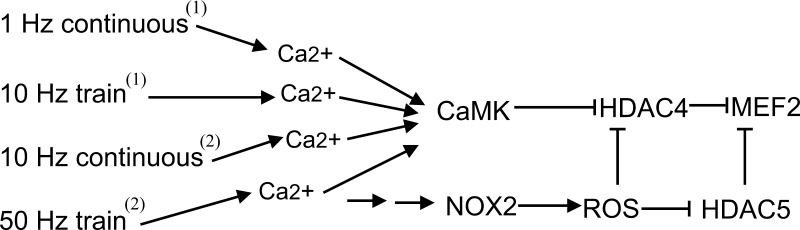

One of our novel findings is that nuclear efflux of HDAC5 is increased only by stimulation patterns generating an increased rate of production of ROS. HDAC5 nuclear efflux was not increased by patterns of muscle activity that only activate CaMK but do not increase the rate of ROS production. This further strengthens the notion that HDAC5 is not a substrate of CaMK II (2). As for HDAC4, since it is a substrate of CaMK II, it responds to electrical stimulation via both ROS and CaMKII. Figure 10 presents a signaling schematic summary for the differential regulation of HDAC4 and 5 nuclear efflux, which is represented functionally in Fig. 10 as an inhibition of the inhibitory influence of HDAC4 or 5 on MEF2 transcriptional activity. Only 50-Hz trains lead to the nuclear efflux of HDAC5 (bottom line), which is mediated exclusively by ROS generated by NOX2. In contrast, all four of the stimulation patterns lead to HDAC4 nuclear efflux, which is mediated by both CaMK and ROS.

Fig. 10.

Working hypothesis: 1-Hz continuous stimulation, 10-Hz train, 10-Hz continuous stimulation, and 50-Hz train trigger calcium transients and activate CaMK, the latter phosphorylates only HDAC4 but not 5, promoting the nuclear efflux of HDAC4. Only 50-Hz train stimulation generates ROS, resulting in nuclear efflux of HDAC4 and 5. Nuclear efflux of HDACs will remove the inhibition on transcription factor MEF2. 1): Liu et al. (20); 2): this study.

NOX2 generates the ROS that causes nuclear efflux of HDAC4 or 5.

NOX2 uses NADPH as a substrate to convert molecular oxygen to generate superoxide, which is then rapidly converted to H2O2. Recently, NOX2 has been reported to be localized mainly in the sarcolemma in skeletal muscle (44) and is considered to be a major source of ROS contributing to muscle damage in dystrophic skeletal muscle (42, 44). During activity of normal skeletal muscle, although NOX was implicated as being a more important source of ROS than mitochondria (28), the exact source and location of ROS generation have not been established (36). Here by using NOX2 KO mice we found that during intense muscle activity, ROS is mainly generated by a NOX2-dependent process. These findings with NOX2 KO mice should be more specific than results with the NOX inhibitors DPI or apocynin. In contrast, in cardiac muscle NOX4 is a major source of oxidative stress (16). According to very recent reports, in cardiac muscle NOX4 plays an essential role in mediating phenylephrine-induced superoxide production and nuclear export of HDAC4 (23), whereas NOX2 is responsible for the ROS generation during mechano-stress in cardiac cells (37). Thus it seems that in skeletal muscle or cardiac muscle, different isoforms of NOX produce ROS in response to different stress signals.

In addition to ROS produced by NOX2, nitric oxide (NO) is generated by nitric oxide synthase during skeletal muscle activity (12, 40) and the ROS-sensitive dye CM-DCFH can react with NO (30). NO production as monitored with an NO-specific dye is increased in FDB fibers stimulated by electrical pulses (500-ms 50-Hz trains, 1 every second; Ref. 40). This is 2.5 times more stimuli per second, on average, than in our 50-Hz train stimulation pattern. However, our results with NOX2 KO mice demonstrate that the entire effect of the 50-Hz train stimulation used in our studies requires NOX2, which does not produce NO. Thus any role of NO in the observed nuclear efflux of HDAC5 or in the NAC-sensitive nuclear efflux of HDAC4 during our 50-Hz train stimulation protocol would have to be via NOX2-generated ROS in conjunction with NO from another source.

Downstream and upstream signaling from and to NOX2.

Assuming that genetic global knockout of NOX2 does not result in compensatory changes resulting in reduced non-NOX2 ROS production during intense muscle activity, our results with muscle fibers from NOX2 KO mice implicate NOX2 as the main source of ROS production during 50-Hz train stimulation. However, the downstream pathway linking this ROS production to HDAC nuclear efflux has not been examined here. One possible mechanism would be direct oxidation and resulting nucleus to cytoplasm translocation of HDAC4 and 5, as recently found for HDAC4 in cardiac muscle but not yet investigated in skeletal muscle (1). Another possible mechanism would be direct or indirect ROS-dependent activation of a kinase that then phosphorylates HDAC4 and 5. Oxidative activation of AMPK (46) could lead to phosphorylation of HDAC4 and 5, resulting in nuclear efflux (24, 25). In contrast, oxidative activation of CaMKII (9) could only phosphorylate HDAC4, but not HDAC5 since CaMKII does not phosphorylate HDAC5. Thus at least the observed nuclear efflux of HDAC5 during 50-Hz train stimulation must be independent of CaMKII.

We have also not investigated the upstream signaling mechanism leading from 50-Hz trains of action potentials to activation of NOX2. Direct Ca2+ activation of NOX2 does not seem to occur (5, 8), but Ca2+ binding to some other direct or indirect regulator of NOX2 might be a possibility. Alternatively, NOX2 could be activated by the mechanical stretch/deformation occurring during the fiber contraction generated by the 50-Hz train stimulation Ca2+ transients (39). In this case, the mechanical changes in response to less intense stimulation patterns, which do not generate ROS, would be insufficient to activate NOX2.

Stimulation pattern-dependent ROS production.

We have found that 50-Hz trains, but not 10-Hz continuous stimulation, generate an increased rate of ROS production in muscle fibers compared with that found in resting fibers as measured with the ROS-sensitive fluorescent dye CM-DCFH. The 50-Hz train pattern of electrical stimulation that we use gives the same average number of pulses per minute as 10-Hz continuous stimulation but grouped at a higher frequency (50 Hz) and in shorter bursts. How an equal number of pulses but grouped into bursts of different frequencies generates different amounts of ROS is an interesting open question for further study. To the best of our knowledge, there is no previous study published on the relationship between stimulation pattern and frequency and the rate of ROS generation in skeletal muscle.

Implications for muscle remodeling and denervation atrophy.

Our findings have potential implications for improved understanding of the connections between ROS production and regulation of muscle function via HDACs. Oxidative stress is implicated in a wide variety of physiological and disease processes in skeletal muscle (34). ROS generated in skeletal muscle is involved in osmotic stress-induced Ca2+ release in normal and dystrophic skeletal muscle fibers (22, 44). Paradoxically, ROS production is increased in skeletal muscle both in response to muscle use as in exercise training and during prolonged periods of disuse (35). In normal skeletal muscle, ROS act as a signaling system during muscle activity by regulating redox sensitive kinases, phosphatases, and transcription factors (35). Of particular importance related to skeletal muscle remodeling is the phosphatase calcineurin, which activates the transcription factor nuclear factor of activated T cells and which is inhibited by oxidation (7). NF-κB and proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator-1α are two other muscle transcriptional regulators previously found to be affected by redox status (11, 14). Here we report for the first time that the nuclear cytoplasmic distribution of class II HDAC4 and 5 are also both regulated by ROS. Enhanced ROS-dependent nuclear efflux of HDAC4 and 5 would relieve the inhibition of these class II HDACs on the transcription factor MEF2 and result in the upregulation of MEF2 transcriptional activity leading to enhanced slow fiber-type gene expression (10, 43). If HDAC4 and 5 have differential effects on MEF2 transcriptional activity, the effects of HDAC4 would be removed by lower intensity activity without ROS involvement, whereas the effects of HDAC5 would only be removed by the higher intensity activity that generates ROS.

HDAC4 and 5 not only play important roles in skeletal muscle fiber type regulation but also are implicated in denervation induced muscle atrophy (29). Dual knockout of HDAC4 and 5 strongly suppresses the expression of MuRF1 and atrogin-1 during denervation and essentially eliminates muscle denervation atrophy (29). On the other hand ROS production, which we show here can promote HDAC nuclear efflux thus decreasing the transcriptional repressor effects of HDACs, is enhanced in disuse muscle atrophy (34), in which both MurF1 and atrogin-1 are increased (18). It will thus be interesting in future studies to quantitatively compare ROS production under different physiological and pathological conditions and to determine the resulting effects on the sub cellular localization of HDACs. It is also important to further investigate how ROS production is fine-tuned under different muscle conditions and to determine whether localization of HDACs is affected. For example, we show here that during intense fiber stimulation the ROS causing HDAC4 and 5 nuclear efflux is generated by NOX2. It is possible that other sources of ROS production and/or other subcellular locations for particular sources of ROS production may ultimately account for the diverse effects of ROS in skeletal muscle. Finally, the possibility of distinct vs. redundant effects of HDAC4 and 5 in muscle fibers requires further investigation.

In conclusion, our results show that NOX2-dependent generation of ROS causes nuclear efflux of HDAC5 and contributes to nuclear efflux of HDAC4 during intense skeletal muscle activity but does not alter Ca2+ transients.

GRANTS

This work is supported by National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases Grant R01-AR056477.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: Y.L., E.O.H.-O., W.R.R., and M.F.S. conception and design of research; Y.L. and E.O.H.-O. performed experiments; Y.L., E.O.H.-O., W.R.R., and M.F.S. analyzed data; Y.L., E.O.H.-O., W.R.R., and M.F.S. interpreted results of experiments; Y.L., E.O.H.-O., W.R.R., and M.F.S. prepared figures; Y.L., E.O.H.-O., W.R.R., and M.F.S. drafted manuscript; Y.L., E.O.H.-O., W.R.R., and M.F.S. edited and revised manuscript; Y.L., E.O.H.-O., W.R.R., and M.F.S. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. M. Williams for NOX2 KO and control mice, Dr. S. L. Schreiber for HDAC4-GFP cDNA, Dr. J. D. Molkentin for adenovirus encoding MEF2-luciferase reporter, and Dr. T. A. McKinsey for adenovirus encoding HDAC5-GFP.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ago T, Liu T, Zhai P, Chen W, Li H, Molkentin JD, Vatner SF, Sadoshima J SF. A redox-dependent pathway for regulating class II HDACs and cardiac hypertrophy. Cell 133: 978–993, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Backs J, Song K, Bezprozvannaya S, Chang S, Olson EN. CaM kinase II selectively signals to histone deacetylase 4 during cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. J Clin Invest 116: 1853–1864, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Backs J, Backs T, Bezprozvannaya S, McKinsey TA, Olson EN. Histone deacetylase 5 acquires calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase II responsiveness by oligomerization with histone deacetylase 4. Mol Cell Biol 28: 3437–3445, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN. Signaling pathways in skeletal muscle remodeling. Annu Rev Biochem 75: 19–37, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bedard K, Krause KH. The NOX family of ROS-generating NADPH oxidases: physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol Rev 87: 245–313, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brown LD, Rodney GG, Hernández-Ochoa E, Ward CW, Schneider MF. Ca2+ sparks and T tubule reorganization in dedifferentiating adult mouse skeletal muscle fibers. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 292: C1156–C1166, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Carruthers NJ, Stemmer PM. Methionine oxidation in the calmodulin-binding domain of calcineurin disrupts calmodulin binding and calcineurin activation. Biochemistry 47: 3085–3095, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Drummond GR, Selemidis S, Griendling KK, Sobey CG. Combating oxidative stress in vascular disease: NADPH oxidases as therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov 10: 453–471, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Erickson JR, Joiner ML, Guan X, Kutschke W, Yang J, Oddis CV, Bartlett RK, Lowe JS, O'Donnell SE, Aykin-Burns N, Zimmerman MC, Zimmerman K, Ham AJ, Weiss RM, Spitz DR, Shea MA, Colbran RJ, Mohler PJ, Anderson ME. A dynamic pathway for calcium-independent activation of CaMKII by methionine oxidation. Cell 133: 462–474, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Esser K, Nelson T, Lupa-Kimball V, Blough E. The CACC box and myocyte enhancer factor-2 sites within the myosin light chain 2 slow promoter cooperate in regulating nerve-specific transcription in skeletal muscle. J Biol Chem 274: 12095–12102, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Irrcher I, Ljubicic V, Hood DA. Interactions between ROS and AMP kinase activity in the regulation of PGC-1α transcription in skeletal muscle cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 296: C116–C123, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jackson MJ. Reactive oxygen species and redox-regulation of skeletal muscle adaptations to exercise. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 360: 2285–2291, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jackson MJ. Control of reactive oxygen species production in contracting skeletal muscle. Antioxid Redox Signal 15: 2477–2486, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kabe Y, Ando K, Hirao S, Yoshida M, Handa H. Redox regulation of NF-kappaB activation: distinct redox regulation between the cytoplasm and the nucleus. Antioxid Redox Signal 7: 395–403, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kalyanaraman B, Darley-Usmar V, Davies KJ, Dennery PA, Forman HJ, Grisham MB, Mann GE, Moore K, Roberts LJ, II, Ischiropoulos H. Measuring reactive oxygen and nitrogen species with fluorescent probes: challenges and limitations. Free Radic Biol Med 52: 1–6, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kuroda J, Ago T, Matsushima S, Zhai P, Schneider MD, Sadoshima J. NADPH oxidase 4 (Nox4) is a major source of oxidative stress in the failing heart. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 15565–15570, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lamb GD, Westerblad H. Acute effects of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species on the contractile function of skeletal muscle. J Physiol 589: 2119–2127, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Levine S, Nguyen T, Taylor N, Friscia ME, Budak MT, Rothenberg P, Zhu J, Sachdeva R, Sonnad S, Kaiser LR, Rubinstein NA, Powers SK, Shrager JB. Rapid disuse atrophy of diaphragm fibres in mechanically ventilated humans. N Engl J Med 358: 1327–1335, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Liu Y, Cseresnyes Z, Randall WR, Schneider MF. Activity-dependent nuclear translocation and intranuclear distribution of NFATc in adult skeletal muscle fibres. J Cell Biol 155: 27–39, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Liu Y, Randall WR, Schneider MF. Activity-dependent and -independent nuclear fluxes of HDAC4 mediated by different kinases in adult skeletal muscle. J Cell Biol 168: 887–897, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Liu Y, Contreras M, Shen T, Randall WR, Schneider MF. Alpha-adrenergic signalling activates protein kinase D and causes nuclear efflux of the transcriptional repressor HDAC5 in cultured adult mouse soleus skeletal muscle fibres. J Physiol 587: 1101–1115, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Martins AS, Shkryl VM, Nowycky MC, Shirokova N. Reactive oxygen species contribute to Ca2+ signals produced by osmotic stress in mouse skeletal muscle fibres. J Physiol 586: 197–210, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Matsushima S, Kuroda J, Ago T, Sadoshima J. The role of nuclear Nox4 in mediating oxidation of HDAC4 in response to phenylephrine stimulation. Cir Res 109: AP205, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 24. McGee SL, van Denderen BJ, Howlett KF, Mollica J, Schertzer JD, Kemp BE, Hargreaves M. AMP-activated protein kinase regulates GLUT4 transcription by phosphorylating histone deacetylase 5. Diabetes 57: 860–867, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. McGee SL, Fairlie E, Garnham AP, Hargreaves M. Exercise-induced histone modifications in human skeletal muscle. J Physiol 587: 5951–5958, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. McKinsey TA, Zhang CL, Lu J, Olson EN. Signal-dependent nuclear export of a histone deacetylase regulates muscle differentiation. Nature 408: 106–111, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McKinsey TA, Zhang CL, Olson EN. Identification of a signal-responsive nuclear export sequence in class II histone deacetylases. Mol Cell Biol 21: 6312–6321, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Michaelson LP, Shi G, Ward CW, Rodney GG. Mitochondrial redox potential during contraction in single intact muscle fibers. Muscle Nerve 42: 522–529, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Moresi V, Williams AH, Meadows E, Flynn JM, Potthoff MJ, McAnally J, Shelton JM, Backs J, Klein WH, Richardson JA, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN. Myogenin and class II HDACs control neurogenic muscle atrophy by inducing E3 ubiquitin ligases. Cell 143: 35–45, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Murrant CL, Andrade FH, Reid MB. Exogenous reactive oxygen and nitric oxide alter intracellular oxidant status of skeletal muscle fibres. Acta Physiol Scand 166: 111–121, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Oka S, Ago T, Kitazono T, Zablocki D, Sadoshima J. The role of redox modulation of class II histone deacetylases in mediating pathological cardiac hypertrophy. J Mol Med (Berl) 87: 785–791, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Olojo RO, Hernández-Ochoa EO, Ikemoto N, Schneider MF. Effects of conformational peptide probe DP4 on bidirectional signaling between DHPR and RyR1 calcium channels in voltage-clamped skeletal muscle fibers. Biophys J 100: 2367–2377, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Palomero J, Pye D, Kabayo T, Spiller DG, Jackson MJ. In situ detection and measurement of intracellular reactive oxygen species in single isolated mature skeletal muscle fibres by real time fluorescence microscopy. Antioxid Redox Signal 10, 1463–1474, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pellegrino MA, Desaphy JF, Brocca L, Pierno S, Camerino DC, Bottinelli R. Redox homeostasis, oxidative stress and disuse muscle atrophy. J Physiol 589: 2147–2160, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Powers SK, Duarte J, Kavazis AN, Talbert EE. Reactive oxygen species are signalling molecules for skeletal muscle adaptation. Exp Physiol 95: 1–9, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Powers SK, Talbert EE, Adhihetty PJ. Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species as intracellular signals in skeletal muscle. J Physiol 589: 2129–2138, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Prosser BL, Wright NT, Hernãndez-Ochoa EO, Varney KM, Liu Y, Olojo RO, Zimmer DB, Weber DJ, Schneider MF. S100A1 binds to the calmodulin-binding site of ryanodine receptor and modulates skeletal muscle excitation-contraction coupling. J Biol Chem 283: 5046–5057, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Prosser BL, Hernández-Ochoa EO, Zimmer DB, Schneider MF. Simultaneous recording of intramembrane charge movement components and calcium release in wild-type and S100A1-/- muscle fibres. J Physiol 587: 4543–4559, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Prosser BL, Ward CW, Lederer WJ. X-ROS signaling: rapid mechano-chemo transduction in heart. Science 333: 1440–1445, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pye D, Palomero J, Kabayo T, Jackson MJ. Real-time measurement of nitric oxide in single mature mouse skeletal muscle fibres during contractions. J Physiol 581: 309–318, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sandström ME, Zhang SJ, Bruton J, Silva JP, Reid MB, Westerblad H, Katz A. Role of reactive oxygen species in contraction-mediated glucose transport in mouse skeletal muscle. J Physiol 575: 251–262, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Shkryl VM, Martins AS, Ullrich ND, Nowycky MC, Niggli E, Shirokova N. Reciprocal amplification of ROS and Ca2+ signals in stressed mdx dystrophic skeletal muscle fibres. Pflügers Arch 458: 915–928, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tang H, Macpherson P, Marvin M, Meadows E, Klein WH, Yang XJ, Goldman DA. histone deacetylase 4/myogenin positive feedback loop coordinates denervation-dependent gene induction and suppression. Mol Biol Cell 20: 1120–1131, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Whitehead NP, Yeung EW, Froehner SC, Allen DG. Skeletal muscle NADPH oxidase is increased and triggers stretch-induced damage in the mdx mouse. PLos One 5: e15354, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wilkins BJ, Dai YS, Bueno OF, Parsons SA, Xu J, Plank DM, Jones F, Kimball TR, Molkentin JD. Calcineurin/NFAT coupling participates in pathological, but not physiological, cardiac hypertrophy. Circ Res 94: 110–118, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zmijewski JW, Banerjee S, Bae H, Friggeri A, Lazarowski ER, Abraham E. Exposure to hydrogen peroxide induces oxidation and activation of AMP-activated protein kinase. J Biol Chem 285: 33154–33164, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zuo L, Clanton TL. Detection of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species in tissues using redox-sensitive fluorescent probes. Methods Enzymol 352: 307–325, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]