Abstract

Background

Male circumcision(MC) can reduce HIV acquisition. However, a better understanding of the indirect protective effect of MC on sexually transmitted infections (STIs) is required.

Objective

To assess the incremental benefits conferred by MC on HIV infection at the individual-level in circumcision trials (no herd immunity effect) and at the population-level (with herd immunity effect) due to its protective effect against other STIs.

Methods

A dynamical stochastic model of HIV and STI infections in a Kenyan population was used to simulate the impact of circumcision offered to a minority of trials participants or to a large fraction of men in order to study the protective role of MC on HIV infection at the individual-level and at the population-level, respectively.

Results

Less than 20% of the HIV infections prevented in the circumcised arm of the circumcision trials (individual-level) could be attributable to MC efficacy against STIs rather than MC efficacy against HIV. At the population-level, MC can significantly reduce HIV prevalence especially among males and among females in the longer term. However, even at the population-level, the long-term incremental impact of MC on HIV due to the protection against STI is modest (even if MC efficacy against the STI and STI prevalence was high).

Discussion

The protection of MC against STI contributes little to the overall effect of MC on HIV in the trials. Additional work is needed to identify if the protective effect of MC efficacy against STIs can have a significant incremental benefit on the HIV epidemic.

Introduction

There is compelling evidence that male circumcision(MC) reduces susceptibility to HIV infection. Early evidence was based on ecological and observational studies(1–9). Results from a meta-analysis of observational studies showed a 50% and 70% reduction in HIV risk amongst circumcised men from the general population and higher-risk groups, respectively(6). The most compelling evidence comes from three recent unblinded randomised control trials(RCT) conducted among adult men in Kenya, Uganda and South Africa(10–12) which suggested a 50% to 60% reduction in HIV risk among circumcised men across the three trials(Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of the three randomised circumcision control trials

| South Africa (Orange Farm, Gauteng) Auvert et al(2005) |

Uganda (Rakai) Gray et al(2007) |

Kenya (Kisumu) Bailey et al(2007) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Community Characteristics | |||

| Population | Semi-urban | Rural | Urban |

| MC rate | 20% | 16% | 10% |

| HIV incidence(per year) | ~1.7% | ~1.8% | ~1.8% |

| Study Characteristics | |||

| Age | 18–24 | 15–49 | 18–24 |

| Sample size | 3274 | 4996 | 2784 |

| Mean follow-up | 18 months | < 24 months | 24 months1 |

| Overall effectiveness (Intention-to-treat) |

60% 95%CI=32−76% |

51% 95%CI= 16−72% |

53% 95%CI=22−72% |

| STI- at baseline | NR -Patients with potential GUD were excluded until successful treatment |

-Self reported: 7% GUD, 3.5%urethral discharge, 6% Dysuria -Patients with potential GUD were excluded until successful treatment |

28% HSV-2, 1% Syphilis, 2% Trichomonas vaginalis, 2% gonorrhoeae, 5% chlamydia, 0% Heamophilus ducreyi -Patients with STI were deferred until treatment |

| Protection of male circumcision against STI |

-The proportion of participants attending a clinic for a GU problem in the 12 months prior to the visit at month 12 was 4.7% in the intervention group compared to the control group(7.2%). |

Self-reported STI: GUD: 47%(36%–57%) Genital discharge: 16%(− 11%, 37%) Dysuria: 3%(−21%−23%) |

NR |

| Protection of male circumcision against HIV after controlling for acquisition of other STI during the trial |

NR | No GUD: 40% 95%CI=− 8%−67% Self reported GUD: 71%(− 29%−97%) |

NR |

| These trials were not designed to provide evidence on the potential mechanisms of protection of male circumcision on HIV acquisition |

|||

NR: Not Reported,

median

Given the overwhelming evidence and the limited preventive options available, WHO/UNAIDS have published recommendations for countries to consider scaling up access to MC in seronegative men, in areas of high HIV prevalence where MC is rare(13). However, a number of important issues such as the safety, cost, feasibility, acceptability, ethics, and potential increase in risky behaviour following circumcision should be considered ideally before the large scale implementation of MC(13). A better understanding of the potential population-level impact of MC is needed in order to identify who should be circumcised. Further research is needed to guide programme implementation and to better understand additional benefits or risks of MC, including the protective effects of MC on other sexually transmitted infections(STIs)(13). Without conducting community based randomised trials, the impact of circumcision at the population-level can be addressed with mathematical modelling if we have a clear understanding of the protective biological mechanisms of MC at the individual-level. To achieve this, it is useful to clearly understand the results of the circumcision trials and to make a distinction between efficacy and effectiveness of MC.

In this paper, we first review and discuss the efficacy and effectiveness of MC on HIV, in particular the incremental benefit of MC on HIV infection due to its indirect protection against cofactor STIs in the context of the three aforementioned randomised trials(10–12). In addition, we present new results on the incremental benefit of MC at the population-level due to its efficacy against other STIs.

Methods

The population-level impact of MC on HIV prevalence was assessed using a previously validated stochastic compartmental model which simulates transmission of HIV and one STI in the heterosexual population in the Kisumu district of Kenya(12,14). The modelled population was stratified into six sexual activity classes with specific rates of sexual partner acquisition. In absence of specific data, the mixing between activity classes was assumed to be proportionate. The STI was modelled with two compartments representing infected or not infected individuals. Infecteds could recover from the STI and be reinfected. Without loss of generalisability, the modelled STI should be thought of as ‘generic’, rather than representing any one specific STI. HIV infection has been modelled with 5 stages representing susceptible, acute, asymptomatic, pre-AIDS, AIDS. The progression of individuals between states was based on specific disease stage parameters or on the force of infection(for susceptible), which depended on the sexual activity, the HIV or STI infection status, HIV and STI prevalence in the pool of partners, the strength of the HIV-STI interaction and the efficacies of MC against HIV(ESHIV) and STI(ESSTI). Upon commencement of the circumcision intervention, a fixed number of susceptible men were recruited from the uncircumcised to the circumcised susceptible compartment. The model structure, the equations and the Monte-Carlo simulation process are fully described in Supplement material.

High(scenario A) and low(scenario B) STI prevalence scenarios were modelled. The distribution by sexual activity classes and rates of sexual partner acquisition for scenario B were selected to agree with infection rates in the Kisumu UNIM male circumcision trial population(12,14–17) and the 2003 Kenyan Demographic and Health Survey(15) corresponding to years 15–17 of the simulated epidemic. Remaining parameters for HIV(14,18–23) and STI(27–29) transmission probabilities, duration of the different HIV states(14,18–24–26) and duration of STI infection(27–29) were based on published studies(Table 2).

Table 2.

Parameter input values used in model simulations for the low baseline (B) and high (A) STI prevalence scenarios (additional model details are provided in supplement material)

| Description of epidemiological parameters | Parameter value with Symbols1 | References | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Duration of HIV stages: | 1/γ1 = 4.4 months, stage 2: 1/γ2 =6.5 yrs, stage 3:1/γ3 = 2 yrs. | 14,18,24–26 | |

| βhk*,j,i: HIV transmission probabilities per partnership from individual of sex k*, sexual activity class j and infection phase h(h=2,3,4) to partner of opposite sex k and class i. Values for females(k*=1) of low activity class(j= 1,2 = lowf) or high activity class(j=3,…,6 = highf) to males of low activity class(i= 1,2 = lowm) or high activity class(i=3,…,6 = highm). Transmission probabilities for male to female are doubled. |

Scenario A β21,lowf ,lowm= 0.048 β31,lowf ,lowm = 0.0032 β41,lowf ,lowm = 0.051 β21,lowf ,highm = 0.026 β31,lowf ,highm = 0.0017 β41,lowf ,highm = 0.026 β21,highf ,lowm = 0.015 β31,highf ,lowm = 0.001 β41,highf ,lowm = 0.0071 β21,highf, highm = 0.015 β31,highf ,highm = 0.001 β41,highf ,highm = 0.0071 Scenario B β21,lowf ,lowm = 0.0048 β31,lowf ,lowm = 0.0032 β41,lowf ,lowm = 0.0051 β21,lowf ,highm = 0.0026 β31,lowf ,highm = 0.0017 β41,lowf ,highm = 0.0026 β21,highf ,lowm = 0.0015 β31,highf ,lowm = 0.0001 β41,highf ,lowm = 0.0071 β21,highf ,highm = 0.0015 β31,highf ,highm = 0.0001 β41,highf ,highm = 0.0071 |

14, 18–23 | |

| Duration with STI infection for all sexes k and activity classes i. | Scenario B: 1/σk,i = 6 months Scenario A: 1/σk,i = 1.33 years | 27 –29 | |

|

Per partnership STI transmission probability: from infected individual of sex k and sexual activity class j to partner of opposite sex k* and class i. |

ξk,i,j = 0.15 for all k,i,j | 27–29 | |

|

HIV cofactors: relative risk(multiplicative factor) for: a1 = increased infectivity with HIV given partner co-infected with STI; a2 = increased susceptibility to HIV given STI infection in the self STI cofactors: relative risk(multiplicative factor) for: b1= increased infectivity with STI given partner co-infected with HIV; b2= increased susceptibility to STI given HIV infection in the self. |

a1=4 a2=3 b1=1.5 b2 =1.5 |

30–32 | |

| Mortality rate due to AIDS (α) | 1/α = 1 year | 24–26 | |

|

Annual rate of sexual partner change: m k,i is the number of new sexual partners per year for person of sex k and sexual activity class i. k=1 represents females; k=2 males. |

Scenario B: Scenario A: m k=1,i=1…6 = m k=1,i=1…6 = 1.0 3.5 5 10 50 75 1.5 4.0 6 12 35 40 m k=2,i=1…6 = m k=2,i=1…6 = 1.5 5.0 10 15 20 25 1.0 3.5 5 10 25 35 |

Assumed | |

|

Percentage of population by activity class i for class k at start of HIV epidemic: ppk,I (%) |

pp k=1, =1…6= 55 20 10 10 2.5 2.5 pp k=2, =1…6= 50 30 5 5 5 5 |

Assumed | |

| Rate of departure from sexually active population | µ = 0.029 (1/µ = 35 yrs) | Assumed | |

| Size of population | 100 000 | Assumed | |

| Coverage =Percentage of HIV-negative males recruited for circumcision | 75% | Assumed | |

| Efficacy of circumcision against HIV | EsHIV = 60% | 10–13 | |

| Efficacy of circumcision against STI | EsSTI = 0%, 40%, 70% | 11,37 –45 | |

| Model output | |||

| Average HIV prevalence in general population over 20 yers | Scenario A: 29.8% | Scenario B: 16.4% | 13,12,14–17 |

| Average STI prevalence in general population over 20 years | Scenario A: 22.3% | Scenario B: 3.7% | |

| Average HIV incidence in general population over 20 years | Scenario A: 5.9 per 100 person-years | Scenario B: 1.9/100 p-yr | |

Symbols relate to equations in Appendix

The presence of STI in the HIV-infected sexual partner was assumed to increase HIV per-partner infectivity by 4-fold, while STI in the HIV-susceptible increased per- HIV susceptibility by 3-fold. This reflected the results from a meta-analytic review of observational studies where the relative risk of HIV due to STI(RRs) in men was less than 4.4 for genital ulcer disease(GUD), 3.1 for all STIs, 2.7 for herpes, 2.5 for syphilis, 3.9 for gonorrhoea and 0.8 for Chlamydia(30–33). HIV infection was also assumed to increase susceptibility to and infectivity with STI by 1.5-fold(30–32). Scenario A was obtained from scenario B by increasing the average duration of STI infection from 6 months to 1.3 years. Because this change also increased HIV infection rates, due to the STI and HIV interaction, we simultaneously decreased HIV transmission probabilities during the early stage and slightly modified the rates of sexual partner change in order to hold HIV infection rates to reasonable levels. The parameter values used for both scenarios and the key characteristics of the simulated STI and HIV epidemics are summarised in Table 2. In both scenarios, the male HIV prevalence was 28% at year 15 and declined as the epidemic progressed due to a strong dependence on STI prevalence which declined due to AIDS differential mortality. In scenario A, the overall STI and HIV prevalence, and HIV incidence averaged 22.3%, 29.8%, and 5.9 per 100 person-years over the 20 years following the intervention (introduced at year 15), respectively compared to 3.7%, 16.4% and 1.9 per 100 person-years respectively for scenario B(1–3,12,14–17).

To assess the individual-level impact of MC, Desai et al(14) simulated the Kisumu MC trial by recruiting and following-up 2750 initially uncircumcised seronegative men from the overall simulated population and randomly assigning them to the circumcision or control arm. The simulated follow-up was 24 months, HIV incidence rate was 2.5% per year in control subjects, STI prevalence averaged 8.2% in controls over the 2 years, which compares with the overall prevalence of bacterial infections observed in the UNIM trial participants at baseline.

To assess the population-level impact of MC, new simulations were performed where a large scale mass circumcision programme was initiated in a mature HIV epidemic in low and high STI prevalence settings(scenarios A and B). Low to high values of MC efficacy against STI (6 scenarios in all) were assumed in MC interventions offered to 75% of HIV susceptible males(either STI positive or STI negative) instead of offering it to a minority of men (as in the simulated trials) where coverage was too small to generate herd immunity.

Theoretical context

Individual-level effect of MC: Efficacy vs Effectiveness

In the clinical trial literature “efficacy” is typically defined as the individual-level clinical/biological benefit of the intervention used under ideal conditions(e.g. with 100% compliance and adherence) – reflecting the maximal effect it can have. Individual-level “effectiveness”, often termed ‘real world’ effectiveness, (not to be confounded with the population-level effectiveness) refers to the effect of the intervention achieved under more realistic conditions of use(e.g., imperfect adherence) and relates more closely to the potential benefit of the intervention to individuals when widely used in practice(33–34).

Determining the efficacy of MC is more complex because MC can have different individual-level efficacies, reflecting different biological/clinical protective mechanisms conferred to individuals directly against HIV or indirectly against other STIs(14,34), such as:

Reduction in susceptibility to HIV infection(EsHIV) or to other cofactors STI(EsSTI);

Reduction of the infectiousness of HIV infected(EIHIV) or STI infected(EISTI) circumcised men for their sexual partners;

Modification of the natural history of STI infection by reducing the frequency of ulcers or by accelerating the natural clearance(EnhSTI).

In RCTs, where HIV negative individuals are randomized and follow-up, it is only possible to estimate a reduction in acquisition to HIV(EsHIV ) and STIs(EsSTI ) independently(34).

Because cofactors STI were on the causal pathway to HIV infection, the primary outcome of the three circumcision trials was the overall effectiveness of MC on HIV acquisition, rather than the independent efficacies against HIV and STIs(11). Thus, the overall effectiveness(i.e. the overall reduction in HIV incidence) measured in the trials could have been the result of a combination of direct protection(efficacies) against HIV acquisition(EsHIV) and/or against acquisition of cofactor STI(EsSTI). For example, in the South African MC trial, the overall effectiveness of 60% could be due to an efficacy against HIV only (EsHIV=60%,EsSTI = 0%) or to some degree of protection against both HIV and STI(0%<EsHIV<60%,0%<EsSTI < 60%).

Population-level and long term: impact

MC has direct effects on HIV at the individual-level and additional indirect effects at the population-level due to herd immunity(i.e a reduced exposure to infection among non circumcised men or women due reduced STIs or HIV prevalence)(31). The total population-level impact is function of the different individual-level efficacies(EsHIV,EsSTI ,EIHIV,EISTI,EnhSTI), thus justifying the need to quantify each of them when possible.

It is also important to evaluate the incremental role played by MC on reducing the incidence of new STI infections and indirectly preventing new HIV infections. Knowledge of EsHIV and EsSTI can help interpret the MC effectiveness results on HIV and to extrapolate results to other communities. If most of the protection against HIV was obtained indirectly via the protection against STIs, then the trial results would depend more strongly on the epidemiology of STIs and the trial population and would therefore have a poorer external validity. The potential impact of MC at the population-level would also depend on the prevalence of the different STIs and the associated synergetic impact with HIV.

Biologically, MC may reduce susceptibility to HIV infection because the underside of the foreskin is rich in HIV target cells(CD4+ T cells). It may also reduce the risk of abrasion, micro tearing and inflammatory conditions suffered by the inner mucosa of the foreskin in uncircumcised men(10–13,35–36). Only one observational study in Rakai suggested a reduction in infectiousness of HIV positive circumcised men for their female partners(8). However, in a very recent clinical trial in Rakai, higher(but not statistically significant) HIV incidence was observed among the wives of circumcised HIV positive men, which was attributed to premature resumption of sexual activity following the surgical procedure, rather than behavioural disinhibition(37).The protective effect of MC against STIs is more uncertain(37–45). A meta-analysis suggested a 33% and 12% reduction in the risk of syphilis and HSV-2 among circumcised men, respectively(38). The estimates across different observational studies varied between −10% to 88% for chancroid. Evidence on the protective effect against gonorrhoea is unclear and mostly based on early studies(9,39,41–44). One study suggested a reduced rate of Chlamydia transmission to their female partners by circumcised compared to uncircumcised men(45). Thus, in the results presented below, the MC efficacies were modelled as a reduction in males’ susceptibility to HIV infection which was fixed to 60%(EsHIV). The efficacy against STI(EsSTI) was varied between 0% and 70%. Low EsSTI(~0–20%) reflected the efficacy of MC on chlamydia and HSV-2 while high EsSTI(~60–80%) reflects efficacy against chancroid and syphilis(11,38,40). We assumed that male-to-female HIV transmission was unchanged by circumcision status(Table 2).

Results

Insights from previous clinical trial simulations

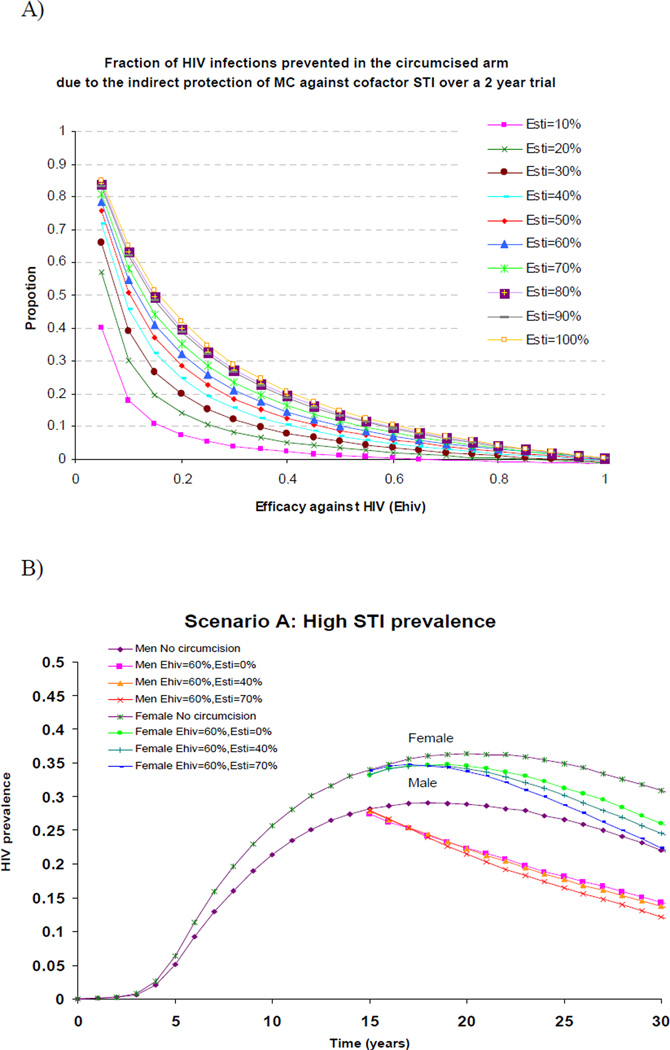

The protective role of MC against cofactor STI on the risk of HIV infection at the individual-level was assessed in Desai et al(14 study, where a small fraction of men were follow-up for two years in the simulated UNIM MC trial in Kisumu(Table 1). Under the UNIM simulated conditions, if MC did not protect against HIV(EsHIV=0%) but strongly protected circumcised men (HIV+ or HIV−) against the STI only(EsSTI=80%), the overall effectiveness against HIV would be only 13%. If the trial duration was prolonged to 5 years and MC efficacy against STI was increased to 100%, the overall effectiveness against HIV, due to the protection against STI alone, increased to 21%. The effectiveness reached 25% or 30% only when the STI prevalence was increased to 19% or when the RRS was increased to six-fold respectively. As these assumptions, especially the 100% efficacy against the STI appeared unrealistically high, the authors concluded that the effectiveness above 50%, as observed in the field RCT, could not have been due solely to the protection against cofactor STI. MC needed to strongly protect directly against HIV(14). In addition, under the STI conditions, MC needed to have an HIV efficacy of at least 40% and 50% to generate the observed overall effectiveness of 50% or 60% against HIV, respectively, even if the efficacy against STI was as high as 60%(14). This also meant that if the MC efficacy against HIV was 40%, not more than 20% of the HIV infections prevented in the circumcised arm of the trial could be attributable to the efficacy against the STI(rather than efficacy against HIV). This proportion decreased as the efficacy against HIV increased(Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

A: Individual-level effectiveness: Fraction of new HIV infections prevented over 2-yers follow-up in the circumcised arm of the simulated Kisumu trial that is due to the indirect protection of male circumcision(MC) against the STI, rather than to a direct protection against HIV(y-axis). In these simulations, both EsSTI and EsHIV were varied. The maximum HIV infection prevented is 100%. Thus, is the STI efficacy(EsSTI) component prevented 20% of new infections, the remaining 80% prevented was due to the efficacy against HIV(EsHIV). As EsHIV, the contribution of EsSTI to the total infections prevented declined.

B: Population-level effectiveness: Overall male and female HIV prevalence over time without and with the circumcision intervention in scenario A when EsHIV =60% and EsSTI varied from 0% to 70%. 75% of uninfected men are reached and circumcised at the beginning of the intervention introduced in a mature epidemic. Scenario A: STI prevalence averaged 24.3% and 20.2% in female and male, respectively.

Insight from the three MC circumcision trials

The effect of circumcision on STI incidence was not reported in the South African trial(10). The baseline STI prevalence only was reported in the Kenyan trial. Gray et al(11) reported a baseline prevalence of 7% and a 47%(95% CI: 36%–57%) reduction in self-reported GUD in the circumcised arm during part of the trial(Table 1). In subgroup analysis, an effectiveness of 40%(95% CI: 8%, 66%) against HIV was reported in the GUD negative group compared to an effectiveness of 51%(95% CI: 16%, 72%) for the whole cohort. In line with the meta-analysis results for high-risk individuals(6), the Rakai sub-group analyses reported an effectiveness of 71%(95% CI −29%, 97%) and 70%(95% CI: 15%, 91%) in men reporting more than 2 partners and with self-reported GUD, respectively. Based on our simulation results, the difference between an effectiveness of 70% and an effectiveness of 50%–60% among high-risk individuals compared to general population, respectively, could partly be explained by the additional protection of MC against STIs if the STI prevalence(≫20%) or the recurrence of ulcers among high-risk individuals is high. In addition, under the UNIM trial conditions, MC efficacy against HIV is predicted to be at least 40%–50% given that the observed individual-level MC effectiveness in the three trials was 50%–60%.

Insights from new simulation results: Population-level and long term impact

Because the trials were of short duration and only captured the reduction in susceptibility to HIV infection(at the individual-level), the field and the simulated trials do not necessarily reflect adequately the incremental impact of MC on HIV at the population-level due to its protective impact against cofactors STI. The full incremental impact due to MC efficacy against STIs may be larger at the population-level and over a longer time scale when coverage increases. To understand the extent of the impact of MC efficacy against STI, we simulated a high(A) and low(B) STI scenario, with a strong STI-HIV interaction.

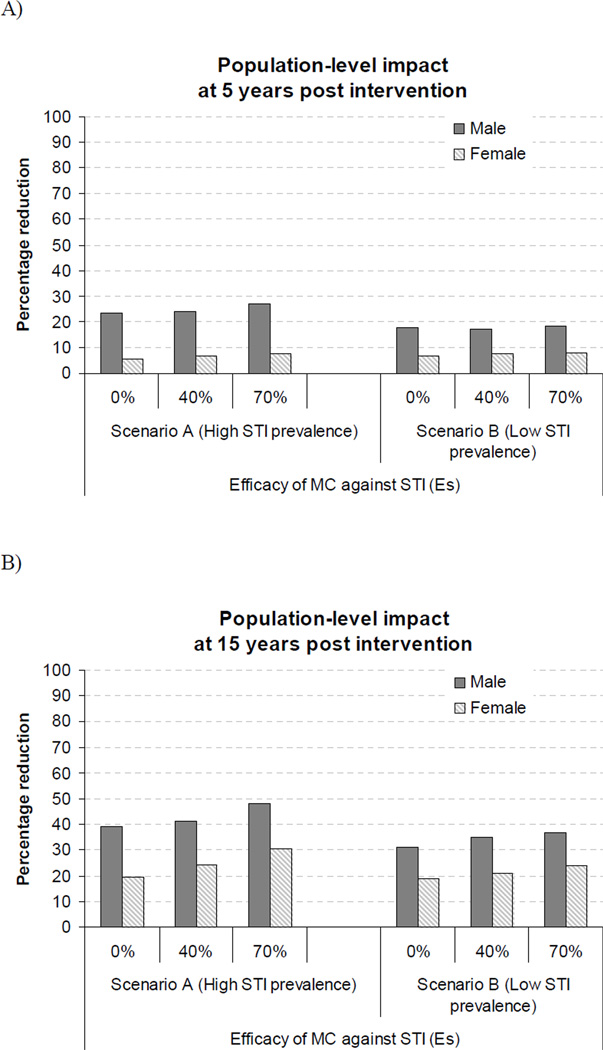

Figure 1B shows the impact of MC on HIV prevalence over time for scenario A. The figure shows that MC can reduce the long term male HIV prevalence and that females would somewhat benefit from herd immunity effect but not noticeably until five to ten years following the intervention. Importantly, the figure also highlights the small incremental impact of MC due to MC efficacy against STI in the long term, even if EsSTI was as high as 70% and if STI prevalence was high. The incremental benefit of MC EsSTI was slightly greater for women than men because STI prevalence declines faster than HIV prevalence in men, and females benefit from the reduced HIV infectivity of men who avoid STIs. Figure 2 summarises the percentage reduction in HIV prevalence 5 and 15 years after the introduction the circumcision intervention. MC efficacy against the STI has a limited impact even in the long term, unless STI prevalence is high (scenario A) and EsSTI is higher (>0%) than currently suggested by data. In the long term, females could benefit substantially from the herd immunity effect of MC (20% reduction in HIV prevalence). Even at the population-level, MC efficacy against HIV produced most of the benefit on HIV in both men and women. Only under specific conditions of very high STI prevalence, high synergetic interaction or large EsSTIcould MC efficacy against STI produce a noticeable incremental benefit for men and women.

Figure 2.

Percentage reduction in overall male and female HIV prevalence between an uncircumcised and circumcised population A) 5 and B) 15 years after a circumcision intervention. 75% of uninfected men are reached and circumcised at the beginning of the intervention which is delivered 15 years after the beginning of the HIV epidemic in scenario A and B. Scenario A: STI prevalence averaged 24.3% and 20.2% in female and male, respectively. Scenario B: STI prevalence averaged 2.9% and 4.5% in female and male, respectively.

Discussion

In this paper, we distinguished between the overall effectiveness of MC and the efficacies of MC against HIV and STIs in order to assess the population-level impact of MC on HIV. Together, the field and simulated trial results suggested that only a small fraction of the observed MC effectiveness against HIV in the RCT could be due to the indirect efficacy against STIs, rather than the efficacy against HIV. The fact that EsSTI contributed little to the overall individual-level effectiveness, may explain the consistency of the estimates, which varied by less than 10% across trials, despite differences in STI prevalence. Thus, the three circumcision trials have good external validity and the results can be extrapolated to settings with different STI epidemiology. To generalise trial results, to settings outside sub-Saharan Africa, the mechanism of protection against HIV- in particular the relative role of hygiene compared to biological mechanisms - remains to be clarified.

Our results support previous modelling studies suggesting that MC has the potential to help curb the HIV epidemic in the long term, in population where MC prevalence is low and in absence of associated sexual disinhibition(46–51). If enough men are circumcised, females will benefit from long-term herd immunity effects. In our model, men were circumcised in a short window period. In practice such high coverage would be reached over a longer term period. It is therefore important to determine who should be circumcised first(e.g., younger and more sexually active men) in order to scale-up circumcision programme to achieve maximum impact very rapidly(51). The population-level impact of MC would even be larger, especially for females if it also reduced the infectiousness of HIV positive circumcised men. However, it could also have detrimental effects if men were more infectious to their female partners immediately after the procedure(37,46). This has obvious implications for the roll-out of mass circumcision.

In the long term, our analysis suggested that the incremental population-level impact of MC on HIV due to a reduction in the acquisition of STIs(EsSTI) among male is also likely to be small. Although we only modelled one generic STI, our conclusions remained valid under extreme assumptions of high MC efficacy against STI (higher than what has been observed), strong STI and HIV association, and very high STI prevalence(Figure 2). The incremental benefit of EsSTI was marginally better for women than men simply because their protection was mediated by herd immunity effects through the rapid decline in STI prevalence among men. Based on current knowledge, we assumed that MC reduced acquisition of new STIs. However, if MC also reduced the frequency or duration of ulcers during the course of infection(11,40), this may provide additional incremental benefits. Considerable uncertainty remains regarding MC efficacy against STIs. The Rakai circumcision trial on HIV acquisition reported a 50% reduction on self-reported GUD(40). However, results from a complementary trial observed a 25% reduction in acquisition of HSV-2 among HIV negative circumcised male, and a 25% reduction in GUD(40). These estimates of MC efficacy against HSV-2 were greater than those suggested in Weiss’s meta-analysis(35,38). The incremental effect of MC on HIV among females would be larger if MC also reduces bacterial vaginosis and trichomonias in the wives of circumcised men(40).

Our results do not demonstrate that MC does not protect against STIs. They only predict that the incremental impact of MC against HIV due to a reduction in males’ susceptibility(EsSTI) to STI is likely to be relatively small in generalized HIV epidemics. Additional work is needed to identify if MC efficacy against STIs can produce more significant benefits under different epidemic characteristics(e.g. concentrated, rising) and to better understand how MC protect against STIs. Even if MC efficacy against STIs did not play an important role in preventing HIV, it would still be beneficial to reduce the burden of STIs.

Supplementary Material

Key Messages.

It is important to distinguish between the overall effectiveness of MC and the efficacies of male circumcision (MC) against HIV and STIs in order to assess the population-level impact of MC on HIV

Only a small fraction of the observed MC effectiveness against HIV in the three MC RCT could be due to the indirect efficacy against STIs, rather than the direct efficacy against HIV

The direct protection of MC against HIV has the potential to help curb the HIV epidemic, in the long term, in population where MC prevalence is low and in absence of associated sexual disinhibition. If enough men are circumcised, females will benefit from long-term herd immunity effects.

However, the incremental population-level benefit of MC on HIV due to a reduction in the acquisition of STIs(EsSTI) among male is predicted to be modest in mature HIV epidemics, unless MC efficacy against STI is very high.

More research is needed to better understand the potential protective mechanisms of MC against STI at both the individual and population-level.

List of abbreviations

- UNIM

Universities of Nairobi, Illinois and Manitoba

- MC

Male circumcision

- RCT

randomised control trial

- ESHIV

Efficacy due to a reduction in susceptibility to HIV infection

- ESSTI

Efficacy due to a reduction in susceptibility to STI infection

- EIHIV

Efficacy due to a reduction in HIV infectiousness of HIV positive circumcised men

- EISTI

Efficacy due to a reduction in STI infectiousness of STI positive circumcised men

- EnhSTI

Efficacy due to a change in the STI natural history among circumcised men

- GUD

Genital ulcer diseases

- RRs

Relative risk of HIV due to STI

Footnotes

The Corresponding Author has the right to grant on behalf of all authors and does grant on behalf of all authors, an exclusive licence (or non exclusive for government employees) on a worldwide basis to the BMJ Publishing Group Ltd to permit this article (if accepted) to be published in STI and any other BMJPGL products and sub-licences such use and exploit all subsidiary rights, as set out in our licence http://sti.bmjjournals.com/ifora/licence.pdf)". If your manuscript does not contain this statement, you will be contacted by the Editorial staff to ensure that it is added.

Authors’ contribution:

All authors have contributed to the planning, the interpretation of the results and the redaction of the manuscript. In addition, MCB and KD have performed written he first version of the manuscript, designed the study and performed the analysis.

References

- 1.Moses S, Plummer FA, Bradley JE, Ndinya-Achola JO, Nagelkerke NJ, Ronald AR. The association between lack of male circumcision and risk for HIV infection: a review of the epidemiological data. Sex Transm Dis. 1994;21:201–210. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199407000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moses S, Bradley JE, Nagelkerke NJ, Ronald AR, Ndinya-Achola JO, Plummer FA. Geographical patterns of male circumcision practices in Africa: association with HIV seroprevalence. Int J Epidemiol. 1990;19(3):693–697. doi: 10.1093/ije/19.3.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tyndall MW, Ronald AR, Agoki E, Malisa W, Bwayo JJ, Ndinya-Achola JO, Moses S, Plummer FA. Increased risk of infection with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 among uncircumcised men presenting with genital ulcer disease in Kenya. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;23(3):449–453. doi: 10.1093/clinids/23.3.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drain PK, Halperin DT, Hughes JP, Klausner JD, Bailey RC. Male circumcision, religion, and infectious diseases: an ecologic analysis of 118 developing countries. BMC Infect Dis. 2006;6:172. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-6-172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Auvert B, Buvé A, Ferry B, Caraël M, Morison L, Lagarde E, Robinson NJ, Kahindo M, Chege J, Rutenberg N, Musonda R, Laourou M, Akam E. Study Group on the Heterogeneity of HIV Epidemics in African Cities. Ecological and individual level analysis of risk factors for HIV infection in four urban populations in sub-Saharan Africa with different levels of HIV infection. AIDS. 2001;15(Suppl 4):S15–S30. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200108004-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weiss HA, Quigley MA, Hayes RJ. Male circumcision and risk of HIV infection in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS. 2000;14:2361–2370. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200010200-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siegfried N, Muller M, Deeks J. HIV and male circumcision – a systematic review with assessment of the quality of studies. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5:165–173. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(05)01309-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gray RH, Kiwanuka N, Quinn TC, Sewankambo NK, Serwadda D, et al. Male circumcision and HIV acquisition and transmission: cohort studies in Rakai, Uganda. Rakai Project Team. Aids. 2000;14:2371–2381. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200010200-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reynolds SJ, Shepherd ME, Risbud AR, Gangakhedkar RR, Brookmeyer RS, Divekar AD, Mehendale SM, Bollinger RC. Male circumcision and risk of HIV-1 and other sexually transmitted infections in India. Lancet. 2004;363(9414):1039–1040. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15840-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Auvert B, Taljaard D, Lagarde E, Sobngwi-Tambekou J, Sitta R, et al. Randomized, controlled intervention trial of male circumcision for reduction of HIV infection risk: the ANRS 1265 Trial. PLoS Med. 2005;2:e298. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gray RH, Kigozi G, Serwadda D, Makumbi F, Watya S, et al. Male circumcision for HIV prevention in men in Rakai, Uganda: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2007;369:657–666. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60313-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bailey RC, Moses S, Parker CB, Agot K, Maclean I, et al. Male circumcision for HIV prevention in young men in Kisumu, Kenya: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;369:643–656. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60312-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.UNAIDS, WHO. [accessed January 31, 2008];Recommendations from expert meeting on male circumcision for HIV prevention. 2007 http://data.unaids.org/pub/PressRelease/2007/20070328_pr_mc_recommendations_en.pdf.

- 14.Desai K, Boily MC, Garnett GP, Masse BR, Moses S, Bailey RC. The role of sexually transmitted infections in male circumcision effectiveness against HIV - insights from clinical trial simulation. ETE. 2006;22:3–19. doi: 10.1186/1742-7622-3-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Central Bureau of Statistics Kenya and Ministry of Health Kenya. Kenya Demographic and Health Survey. 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moses S, Bailey RC, Agot K, Parker CB, Maclean IW, Ndinya-Achola JO. A randomized controlled trial of male circumcision to reduce HIV incidence in Kisumu Kenya: Progress to date [Abstract TO-702] International Society of Sexually Transmitted Diseases Research. 2005 Jul 10–13; [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bailey RC, Moses S, Agot K, Parker CB, Maclean IW, Ndinya-Achola JO. A randomized controlled trial of male circumcision to reduce HIV incidence in Kisumu, Kenya: progress to date [Abstract TUAC0201]; XVI International AIDS conference; August 13–18, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wawer MJ, Gray RH, Sewankambo NK, Serwadda D, Li X, Laeyendecker O, Kiwanuka N, Kigozi G, Kiddugavu M, Lutalo T, Nalugoda F, Wabwire-Mangen F, Meehan MP, Quinn TC. Rates of HIV-1 transmission per coital act, by stage of HIV-1 infection in Rakai, Uganda. J Infect Dis. 2005;191(9):1403–1409. doi: 10.1086/429411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leynaert B, Downs AM, de Vincenzi I. Heterosexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus: variability of infectivity throughout the course of infection. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;148(1):88–96. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Vincenzi I. A longitudinal study of human immunodeficiency virus transmission by heterosexual partners. N Engl J Med. 1994;331(6):341–346. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199408113310601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fideli US, Allen SA, Musonda R, Trask S, Hahn BH, Weiss H, Mulenga J, Kasolo F, Vermund SH, Aldrovandi GM. Virologic and immunologic determinants of heterosexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in Africa. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2001;17(10):901–910. doi: 10.1089/088922201750290023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gray RH, Wawer MJ, Brookmeyer R, Sewankambo NK, Serwadda D, Wabwire-Mangen F, Lutalo T, Li X, vanCott T, Quinn TC Rakai Project Team. Probability of HIV-1 transmission per coital act in monogamous, heterosexual, HIV-1-discordant couples in Rakai, Uganda. Lancet. 2001;357(9263):1149–1153. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04331-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Quinn TC, Wawer MJ, Sewankambo N, Serwadda D, Li C, Wabwire-Mangen F, Meehan MO, Lutalo T, Gray RH. Viral load and heterosexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(13):921–929. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200003303421303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smit C, Geskus R, Uitenbroek D, Mulder D, Van Den Hoek A, Coutinho RA, Prins M. Declining AIDS mortality in Amsterdam: contributions of declining HIV incidence and effective therapy. Epidemiology. 2004;15(5):536–542. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000135171.07103.f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.San Andres Rebollo FJ, Rubio Garcia R, Castilla Catalan J, Pulido Ortega F, Palao G, de Pedro Andres I, Costa Perez-Herrero JR, del Palacio Perez-Medel A. Mortality and survival in a cohort of 1,115 HIV-infected patients (1989–97) An Med Interna. 2004;21(11):523–532. doi: 10.4321/s0212-71992004001100002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marins JR, Jamal LF, Chen SY, Barros MB, Hudes ES, Barbosa AA, Chequer P, Teixeira PR, Hearst N. Dramatic improvement in survival among adult Brazilian AIDS patients. AIDS. 2003;17(11):1675–1682. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200307250-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brunham RC, Plummer FA. A General Model of Sexually Transmitted Disease Epidemiology and Its Implications for Control. Medical Clinics of North America. 1990;74(6):1339–1352. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(16)30484-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pinkerton SD, Layde PM. Using sexually transmitted disease incidence as a surrogate marker for HIV incidence in prevention trials - A modeling study. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2002;29(5):298–307. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200205000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anderson RM. Transmission Dynamics of Sexually Transmitted Infections. In: Holmes KK, Sparling PF, Mardh PA, Lemon SM, Stamm WE, Piot P, Wasserheit JN, editors. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. McGraw-Hill; pp. 25–37. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rottingen JA, Cameron DW, Garnett GP. A systematic review of the epidemiologic interactions between classic sexually transmitted diseases and HIV: how much really is known? Sex Transm Dis. 2001;28:579–597. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200110000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fleming DT, Wasserheit JN. From epidemiological synergy to public health policy and practice: the contribution of other sexually transmitted diseases to sexual transmission of HIV infection. Sex Transm Infect. 1999 Feb;75(1):3–17. doi: 10.1136/sti.75.1.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laga M, Alary M, Nzila N, et al. Condom promotion, sexually transmitted diseases treatment, and declining incidence of HIV-1 infection in female Zairian sex workers. Lancet. 1994;344(8917):246–248. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)93005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Piantadosi S. In: Clinical trials A methodological perspective. John Wiley, Sons, editors. New-York: 1997. p. page 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boily MC, Abu-Radda L, Desai K, et al. Measuring the public-health impact of candidate HIV vaccines as par of the licensing process. Lancet Infectious Disease. 2008 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70292-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weiss HA. Male circumcision as a preventive measure against HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2007 Feb;20(1):66–72. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e328011ab73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Szabo R, Short RV. How does male circumcision protect against HIV infection? BMJ. 2000 Jun 10;320(7249):1592–1594. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7249.1592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wawer M, et al. Trial of circumcision in HIV+ men in Rakai, Uganda: effects in HIV+ men and women partners; Fifteenth Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; Boston. 2008. Abstract 33LB. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weiss HA, Thomas SL, Munabi SK, Hayes RJ. Male circumcision and risk of syphilis, chancroid, and genital herpes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sex Transm Infect. 2006 Apr;82(2):101–109. doi: 10.1136/sti.2005.017442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Van Howe RS. Genital ulcerative disease and sexually transmitted urethritis and circumcision: a meta-analysis. Int J STD AIDS. 2007 Dec;18(12):799–809. doi: 10.1258/095646207782717045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tobian A, et al. Trial of male circumcision: prevention of HSV-2 in men and vaginal infections in female partners, Rakai, Uganda; Fifteenth Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; Boston. 2008. Abstract 28LB. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Donovan B, Bassett I, Bodsworth NJ. Male circumcision and common sexually transmissible diseases in a developed nation setting. Genitourin Med. 1994 Oct;70(5):317–320. doi: 10.1136/sti.70.5.317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cook LS, Koutsky LA, Holmes KK. Circumcision and sexually transmitted diseases. Am J Public Health. 1994;84(2):197–201. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.2.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hart G. Factors associated with genital chlamydial and gonococcal infection in males. Genitourin Med. 1993;69(5):393–396. doi: 10.1136/sti.69.5.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Parker SW, Stewart AJ, Wren MN, Gollow MM, Straton JA. Circumcision and sexually transmissible disease. Med J Aust. 1983;2(6):288–290. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1983.tb122467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Castellsagué X, Peeling RW, Franceschi S, de Sanjosé S, Smith JS, Albero G, Díaz M, Herrero R, Muñoz N, Bosch FX IARC Multicenter Cervical Cancer Study Group. Chlamydia trachomatis infection in female partners of circumcised and uncircumcised adult men. Am J Epidemiol. 2005 Nov 1;162(9):907–916. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kalichman S, Eaton L, Pinkerton S. Circumcision for HIV Prevention: Failure to Fully Account for Behavioral Risk Compensation. PLoS Med. 2007 Mar 27;4(3):e138. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nagelkerke NJ, Moses S, de Vlas SJ, Bailey RC. Modelling the public health impact of male circumcision for HIV prevention in high prevalence areas in Africa. BMC Infect Dis. 2007;7:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-7-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Williams BG, Lloyd-Smith JO, Gouws E, Hankins C, Getz WM, et al. The potential impact of male circumcision on HIV in Sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e262. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Podder CN, Sharomi O, Gumel AB, Moses S. To cut or not to cut: a modelling approach for assessing the role of male circumcision in HIV control. Bull Math Biol. 2007 Nov;69(8):2447–2466. doi: 10.1007/s11538-007-9226-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Orroth KK, Freeman EE, Bakker R, Buvé A, Glynn JR, Boily MC, White RG, Habbema JD, Hayes RJ. Understanding the differences between contrasting HIV epidemics in east and west Africa: results from a simulation model of the Four Cities Study. Sex Transm Infect. 2007;83(Suppl 1):i5–i16. doi: 10.1136/sti.2006.023531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hallett TB, Singh K, Smith JA, White RG, Abu-Raddad LJ, Garnett GP. Understanding the impact of male circumcision interventions on the spread of HIV in southern Africa. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(5):e2212. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.