Abstract

Objectives

The high prevalence of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and the increased cost of treatment have prompted strategies for the primary prevention of CVD in the UK to move towards the use of validated CVD risk scores to identify individuals at the highest risk. There are no reviews evaluating the effectiveness of this strategy as a means of reducing CVD risk or mortality. This review summarizes current evidence for and against the use of validated CVD risk scores for the primary prevention of CVD.

Design

We utilized an in depth search strategy to search MEDLINE, EMBASE and the Cochrane database of clinical trials, expert opinions were sought and reference lists of identified studies and relevant reviews were checked. Due to a lack of homogeneity in outcomes and risk scores used it was not possible to conduct a meta-analysis of the identified studies.

Setting

The majority of included trials were carried out in a primary care setting. 2 trials were carried out in North America, 2 in Scandinavia and 1 in the UK.

Participants

31,651 participants in total were recruited predominantly from a primary care setting. Participants were aged 18-65 years old and were free from CVD at baseline.

Main outcome measures

Outcome measures used in the included studies were change in validated CVD risk score and CVD/All-cause mortality.

Results

We identified 16 papers which matched the inclusion criteria reporting 5 unique trials. Due to a lack of homogeneity in outcomes and risk scores used it was not possible to conduct a meta-analysis of the identified studies. Only one study reported a significant difference in risk score at follow up and one study reported a significant difference in total mortality, however significant differences in individual risk factors were reported by the majority of identified studies.

Conclusions

This review demonstrates the potential for multifactorial interventions aimed at individuals selected by CVD risk scores for lowering CVD risk and mortality. However, the majority of studies in this area do not provide an intensity of intervention which is sufficient in significantly reducing CVD mortality or validated CVD risk.

Background

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is one of the leading causes of mortality and morbidity worldwide. In 2001, approximately one third of mortalities worldwide were attributable to CVD and it is predicted to become the leading cause of death in developed countries.1 In the USA, CVD accounts for 35.2% of mortality2 compared to 48% in Europe.3 The estimated annual cost of CVD to the EU economy is £169 Billion.4

The risk of suffering from CVD is governed in part, by modifiable risk factors including; physical activity level, obesity, cholesterol levels, blood pressure, smoking status and glucose intolerance. CVD prevention programmes aim to reduce the risk of CVD by modifying one or more risk factors through lifestyle modification or pharmacological therapy.5

Evidence for the use of lifestyle interventions in reducing cardiovascular mortality is relatively scarce. There are very few studies that have been designed to detect changes in total or CVD mortality instead focussing on changes in individual risk factors. A recent review found that of ten trials reporting change in total mortality, three reported significant changes in mortality and only one showed a significant benefit for coronary heart disease mortality.5

Assessing risk of CVD has emerged as a simplistic way of targeting intervention strategies at those who are asymptomatic but at high risk of developing CVD.6 Multivariate risk functions derived from large scale cohort studies and RCT's form the basis of these predictive scores.7–10

Evidence for the efficacy of sustained behaviour change following individually tailored multifactorial interventions in the primary prevention of CVD is sparse. Unifactorial Interventions targeted at reducing risk factors such as smoking have proven successful,11 but there is a need for further evaluation of multifactorial interventions.

In England during 2009, the Department of Health introduced the ‘NHS Health Check’ programme, aimed at assessing people aged 40–74 for their CVD risk followed by appropriate interventions and management in high-risk individuals.12,13 This method of identifying and treating individuals at the highest risk has proved successful in preventing and managing the progression of other chronic diseases.14,15 No reviews have focused on studies that used this method of systematically selecting participants using validated risk scores and offering an intervention to reduce CVD risk or mortality.

A systematic review was conducted assessing the efficacy of lifestyle interventions in reducing CVD risk or CVD mortality and morbidity. We searched for multifactorial interventions which recruited participants at risk, defined by a validated CVD score. The aim of this review is to assess the effectiveness of the use of CVD risk scores when combined with lifestyle interventions in the prevention of CVD.

Methods

EMBASE (1980–2008 week 37), MEDLINE (1950-2008 September week 2) and the Cochrane database of clinical trials were searched for articles assessing the effect of multifactorial interventions on CVD risk score, CVD mortality or morbidity. The search was carried out using medical search headings (MeSH) and keywords. (See Appendices available online at: http://jrsm.rsmjournals.com/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1258/jrsm.2012.110193/-/DC1)

Procedure

One reviewer (AW) performed the electronic searches and two researchers (AW and TY) performed the hand-searches and analysed the results. Two researchers (AW and TY) independently reviewed all relevant studies and performed data extraction.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

We included studies with at least 6 months follow-up. Participants were aged 40 or above and free from CVD at baseline but classified as high risk by a validated risk score. Outcomes included were: CVD mortality, incidence of CV events or changes in a validated CVD risk score as a composite measure of change in risk factors. Study type was restricted to RCT's. No studies were excluded due to publication date. Studies with insufficient randomization or no control group were also removed from the analysis. Studies which did not define high-risk patients using a validated CVD risk score were excluded.

Assessment of study quality

Study quality was assessed by two reviewers (AW and TY) using several key indicators which are known to influence the risk of bias in trials.16 Due to the nature of the interventions used, participant blinding was not possible. This indicator was therefore not considered as a measure of quality for this review.

Results

Trial flow

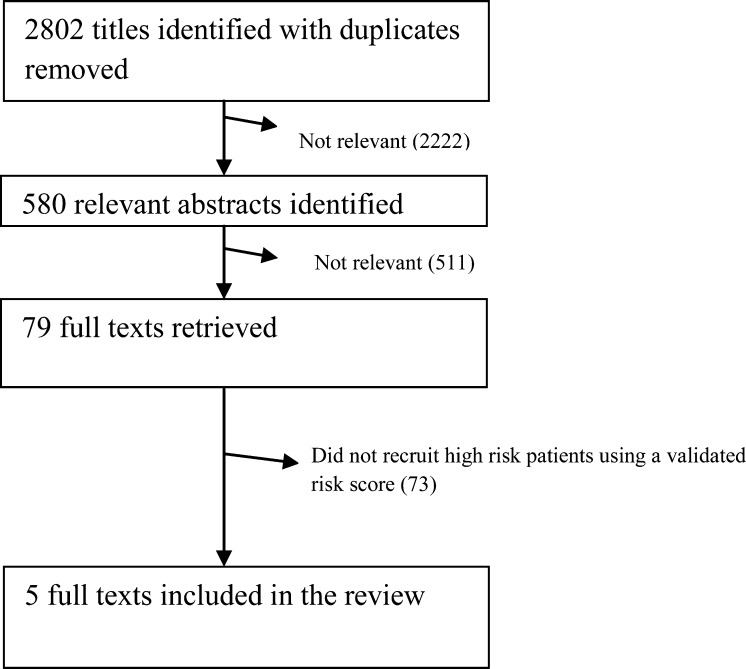

We identified 2802 unique articles. We assessed the titles and abstracts and obtained the full texts for all relevant papers. Of these, 79 full texts were retrieved and 74 were excluded as they did not use a validated risk score to recruit. A total of 16 papers were identified and 5 unique trials were reported (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Number of trials identified at each stage of the selection process and reasons for their exclusion

Due to the heterogeneity between the risk scores used it was not possible to conduct a meta-analysis.

A total of 5 trials evaluating interventions in patients identified by a risk score were included in the review. The characteristics of the included trials are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of included studies

| Study name | Country | Sample size | Risk tool | Intervention | No of Appointments/Contact time | Follow up | Change in risk score versus control | Change in mortality/CV events |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wister et al.15 | Canada | 315 | Framingham | Tailored risk profile with letter grading system, telephone counselling | Appointments at 10 days and 6 months thereafter for 30 mins per session and up to 60 mins per year. Additional smoking cessation sessions. | 1 Year | Intervention. −3.10 (−3.98 to −2.22) Control −1.30 (−2.18 to 0.42) (P = 0.002) | Not Reported |

| Meland et al.16 | Norway | 110 | ‘Infarction Score’ | 3 monthly lifestyle counselling. Promotion of self monitoring. Stress coping audiotape offered. | Appointments every 3 months, GP's in control arm attended 2 hour educational session | 1 Year | Infarction score went from 1.98–0.01 in self-directed care group but not significant from control (P = 0.25) | Not Reported |

| Ketola E17 | Finland | 150 | Finnish CVD risk score derived from North Karelia project | Individualized HCP led risk factor advice using booklets on healthy lifestyle. Those with BMI ≥34 received counselling from a dietician. Weight reduction group and group/individual physio sessions. Drugs prescribed if targets not met. | Appointments at baseline, 6 months, 12 months and 24 months | 2 Years | CVD risk score decreased by 28% in the intervention group but not significantly different to control (P value not reported) | Not Reported |

| MRFIT6 | USA | 12,866 | Framingham derived risk score | Individualized HCP led intensive intervention stage addressing three main risk factors; blood pressure, nutritional advice and smoking cessation. Followed up quarterly to track risk factor changes | 3 screening visits, Intervention group attended clinic at 4 and 8 months. All attended annual clinics. | 7 Years | Risk factor levels declined in intervention group. But not significant from control (P value not reported) | CHD mortality 7.1% lower (not significant) and CVD deaths 4.7% lower than control. (P value not reported) |

| WHO Multifactorial Preventative Trial19 | Europe | 18,210 | Computer risk scoring system | Cholesterol lowering diet advice, smoking cessation, PA advice, hypertensive medication for those with systolic pressure of ≥160. | Annual appointments. Delivery of intervention varied depending on factory medical staff and between countries. | 6 Years | Intervention group reduced risk by 19.4% compared to 11.1% in the trial as a whole (P value not reported) | 7.4% reduction in CHD Deaths. (P > 0.05) |

PA = Physical activity, HCP = Health Care Professional

Two of the trials identified were carried out in North America, two in Scandinavia and one in Europe. Sample sizes ranged from 110 to 18,210, and a mean follow-up of 3 years, ranging from 1 to 7 years. The age of participants in the identified trials ranged from 18–65 years.

Of the trials identified, all five reported change in risk score as an outcome measure, two of the studies reported CVD mortality as outcomes. Three of the trials identified had sufficient power to detect a difference in risk score. Two of the trials were designed with sufficient power to detect a difference in CVD mortality.

Assessment of study quality

An overview of the results of the study quality assessment can be found in Table 2. All but one study17 did not adequately describe the allocation sequence or allocation concealment. All papers gave a detailed method with regards to incomplete outcome data. Other possible sources of bias were also sufficiently discussed.

Table 2.

Summary of Study Quality

| Study | Sequence Generation Reported | Allocation concealment Reported | Incomplete Outcome Data addressed | Selective outcome reporting addressed | Other Sources of Bias explained |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MRFIT6 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Wister et al.15 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| WHO Multifactorial Preventative Trial19 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Ketola et al.17 | No | No | Unclear | Unclear | No |

| Meland et al.16 | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

The studies included in this review demonstrate heterogeneity in interventions offered to participants, thus making it difficult to assess the effect of interventions collectively without relative weighting of the individual elements.

All of the trials included screening sessions to record cholesterol, blood glucose, smoking status, activity level and dietary habits. The results of this informed the treatment given. All studies used some degree of individually tailored intervention based on individual risk profile. Two of the studies17,18 encouraged goal setting to promote long-term adherence to the intervention. All of the interventions gave supporting literature consisting of didactic brochures and information on smoking cessation where appropriate. Stress coping audiotapes and instructions on cognitive relaxation techniques were provided to patients in one study.18 Different approaches to promotion of a healthy diet were adopted by all of the studies identified. One intervention18 used self report questionnaires and self-monitoring of foods eaten and written contracts to increase adherence. The MRFIT trial adopted a wider approach by encouraging the development of lifelong shopping and eating patterns rather than imposing strict dietary regimes. Five of the interventions were nurse-led with behavioural scientists, nutritionists and health councillors providing care. The telephone-based study by Meland et al.18 was led by Kinesiologists. All of the trials used some form of drug treatment in combination with lifestyle advice to treat individual risk factors and modify overall CVD risk in line with the appropriate guidelines.

In all of the trials identified, the control arm was reported as having received normal or conventional care, however in two studies19 the control arm received normal/conventional care and additional didactic brochures and booklets aimed at risk factor modification. In the MRFIT study,20 participants in the control group received normal care but received an annual invite to undergo a physical examination.

Intensity of intervention

Only one of the identified trials17,21 included sufficient detail to establish exact contact time. However, the frequency of follow-up visits and consultations during the study period was reported and varied dramatically. The MRFIT trial20 consisted of two initial screening sessions for those at high risk; assessment of blood pressure, smoking status, dietary assessment and lipid profiling at 4 and 8 months, 10 weekly group sessions and annual assessments. The European WHO22 trial followed an initial screening and intervention session by assessing a fresh 5% random sample of the intervention group annually and the whole study population at baseline and 5 year follow-up. Subsequently, 75% of participants in the intervention group only had contact at baseline and 5 year follow-up.22

Change in risk factor score

There was very little homogeneity in the risk score used and the method by which it was reported. As a result, comparison of the results between trials identified is difficult. However, a significant between group difference in favour of a reduction in risk score was reported in one of the trials identified.22 A net reduction in estimated CHD risk of 19% was reported with a high level of variation in risk reduction between subgroups. Figures for the UK arm of this study show a more modest 4% reduction in estimated CHD risk, compared to a difference of 28% in Italy. These differences were explained by variations in staffing levels and the intensity of intervention which was not standardized.

Change in risk factors

Two of the identified trials22 either did not report changes in individual risk factors or did not report results from sub group analyses for individuals in the high-risk group identified by a risk score. The main risk factors measured were: total cholesterol, body weight, systolic blood pressure, blood glucose and smoking history. In general, trials reported conflicting results for changes in individual risk factors. Total cholesterol showed a small but significant difference between intervention and control groups in three of the five trials identified with between group differences ranging from 1–2%.20–22 Non-significant differences were found in the remaining study. However, it was noted that these trials were designed with sufficient power to detect a change in individual risk factors.

Interventions had a significant effect in reducing blood pressure in one of the five identified trials19 with reported between group differences of 4% in the MRFIT trial, however no significant between group differences were reported in the other trials.

There was strong evidence for the success of smoking cessation following multifactorial lifestyle interventions. One of the identified trials reported significant differences in smoking cessation when adjusted for the direct measurement of thyocyanate.20 Although the obvious benefits gained from smoking cessation cannot be ignored, the results from a number of the included trials showed that this was not associated with a statistically significant change in CVD risk score, when compared to the control arm.

Change in total mortality

Two trials were designed with sufficient power to detect a change in risk of CVD mortality.20,22 The MRFIT trial reported a potential net lowering of CHD mortality of 22.2% following analysis based on CHD risk and 6 year follow up. Results from the WHO collaborative trial22 showed percentage net difference between intervention and control of 7.4 % (SD 1.6). However, sub-group analysis conducted by country showed a significant reduction in incidence of fatal CHD and nonfatal MI of 24% (SD 2.7) in the Belgian study arm.

Discussion

The evidence for the use of risk cores followed by multifactorial interventions for the reduction of CVD risk is currently not strong enough to formulate a definitive conclusion. Of five trials identified, one trial identified a significant difference between intervention and control for a reduction in CVD risk score.22 Two trials which measured CVD mortality, both reported reductions in mortality, although only one reported a statistically significant difference from the control group.

Both of the interventions that reported significant differences between groups17,20 used a higher intensity of intervention to do so and were the two most intensive interventions included in the review. In general, there was a logical trend towards greater reductions in CVD risk and CVD mortality in trials with more intensive interventions. It is possible that the majority of studies included in this review which found no beneficial effect on outcomes did so because the interventions delivered were not intensive enough to provoke a change in behaviour.

Past literature has prompted the hypothesis that greater benefits may be obtained from lifestyle modification and education in high-risk individuals than at those at lower risk. Individuals at high risk may be more likely to modify their choices relating to healthy behaviour following consultation with a GP23 therefore reducing CVD risk. No clear conclusion can be drawn from the data in this area as only two trials identified by this review support this hypothesis. Studies by Wister et al.17 and the MRFIT20 study group found significant reductions in a validated risk score and CHD mortality following multiple risk factor interventions when recruiting individuals at high risk of CVD. Past reviews have generally found no effect of interventions on mortality.5

The majority of the trials were limited to a follow-up period of one year which may not be sufficient time for the benefits to individual risk factors to be observed. In comparison, a 7 year follow-up data from the MRFIT20 trial showed significant reductions in cholesterol, smoking and blood pressure. Previous trials have determined that the full benefits of lipid modifying and antihypertensive medication may not become apparent until at least 2 years of adherence.24,25 Previous commentators have suggested this could be attributable to greater than expected changes in control groups. Significant increases in exercise have been observed at 12 months,19 but it is questionable whether long term behavioural change can be effectively evaluated within such a timeframe. One criticism of at least two trials relates to the risk score used, both to recruit and as an outcome measure to define changes in global CVD risk. Both the MRFIT20 and trial by Wister et al.17 used risk scores which only differentiate between smokers and non-smokers, and do not consider the length of time since quitting. The risks associated with smoking do not disappear immediately and may exist after the individual has ceased.26

Reporting an individual as a non-smoker at follow-up could lead to an underestimation of risk, giving a short-term false benefit of an intervention.

Ethical issues surrounding the design of such trials prevented interventions being compared to a ‘true’ control group. The control group in some studies received booklets on healthy lifestyle or were invited to annual health checks. This may have had a positive health impact on the control group.

Current strategies for the prevention and management of chronic conditions in the UK are unstructured and vary between individual practices and primary care trusts.27,28 Previous reviews show that multifactorial approaches to risk factor reduction may bring about greater decreases in cardiovascular mortality than the sum of the effects of individual risk factor reductions,29 current practice needs to reflect this. Evidence for the use of multiple risk factor interventions in low to medium CVD risk individuals is currently weak, with the majority of trials having no effect on mortality or estimates of CVD risk.5 In practice the identification of ‘high risk’ individuals and targeting of intensive interventions has the potential for greater benefit to individuals. However, the current evidence for this approach needs to be strengthened to assist in the development of interventions which are both intensive enough to bring about long term behaviour change and deliverable using current resources available to primary care organizations.

Strengths and weaknesses of this review

This systematic review is the first to assess whether recruiting participants using CVD risk scores and subsequently offering lifestyle advice is effective in reducing mortality or their CVD risk. Consequently there are no reviews with which to compare the results of this review. We utilized an in-depth systematic design and execution of our search strategy, including a number of relevant databases, and in selecting our final papers and extracting and reviewing the relevant data. Due to the low number of trials that fitted the inclusion criteria and the lack of homogeneity in risk score used, we were unable to conduct a meta-analysis and limited our ability to make quantitative comparisons of effect sizes relating to changes in risk score or mortality.

Implications for clinical practice

The Department of Health has estimated that the Health Checks programme will prevent 9500 heart attacks and prevent 4000 people from developing diabetes.30 The strategy for implementing the NHS Health Check requires the calculation of a validated risk score to identify those at high risk of CVD, and to provide appropriate management with lifestyle interventions and pharmacological therapy. The majority of trials identified have found no effect of lifestyle interventions on CVD risk.18,19 However, both trials that assessed effect on mortality19,20 found a lowering of CVD mortality following an intervention. The intensity of intervention was higher in those trials which reported significant differences in CVD risk and mortality. The findings of this review have future implications in the planning primary care interventions where a balance must be found between real improvements in health related outcomes; and an intensity of intervention that does not overwhelm current resources. There is therefore some evidence to support the potential use of this strategy as a means of reducing mortality. However, further research is needed to provide evidence to inform the development of future interventions.

Conclusion

Current evidence suggests that lifestyle interventions aimed at the primary prevention of CVD that use validated risk scores to recruit high risk individuals show potential for lowering CVD mortality and the incidence of cardiovascular events, particularly in trials with high intensity interventions.

The findings of this review highlight the importance of targeting individuals at the higher risk of CVD whom have most to gain in terms of absolute reduction in CVD risk and where the best evidence for improvement is shown. From the limited amount of evidence that is available it is clear that more intensive interventions have shown to be effective, particularly in smoking cessation, reductions in blood pressure and behaviour change relating to diet. Further investigation is needed into lower intensity interventions in low to moderate risk groups.

All future trials in this area would benefit from a more thorough economic evaluation given the current financial climate in which cost effectiveness will play a major part in deciding whether interventions are adopted into routine care for the primary prevention of CVD.

DECLARATION

Competing interests

KK and MJD are both advisors to the national screening committee. They are co-authors of the handbook for vascular risk assessment, risk reduction and risk management. They have received grants from the national institute for health research and Diabetes UK to conduct research in the early detection, prevention and management of diabetes and cardiovascular disease. AW and TY have no competing interests to declare

Funding

None

Ethical approval

Not appropriate

Guarantor

KK

Contributorship

AW contributed as first author to this paper. MD and KK advised on the study design and analysis. TY acted as second reviewer

Acknowledgements

None

Reviewer

John Robson

References

- 1.World Health Organisation. World Health Report 2002. Reducing Risks and Promoting Healthy Life. Geneva, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.American Heart Association Statistics Writing Group. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics–2008 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation 2008;117:e25–146. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.World Health Organisation. European cardiovascular disease statistics 2008 Chapter 1: Mortality. Geneva, 2008.

- 4.British Heart Foundation. European Cardiovascular Disease Statistics. 2005 Edition.

- 5.Ebrahim S, Beswick A, Burke M, Davey Smith G Multiple Risk Factor Interventions for Primary Prevention of Coronary Heart Disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2006;Issue 4:CD001561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brindle P, Beswick A, Fahey T, Ebrahim S Accuracy and impact of risk assessment in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: a systematic review. Heart 2006;92:1752–59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anderson K, Odell P, Wilson P, Kannel W Cardiovascular disease risk profiles. American Heart Journal 1991;121:293–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Assman G, Cullen P, Schulte H Simple scoring scheme for calculating the risk of acute coronary events based on the 10 year follow up of the prospective cardiovascular Munster (PROCAM) study. Circulation 2002;105:310–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilson PF, D'Agostino R, Levy D, Belanger A, Silbershatz H, Kannel W Prediction of coronary heart disease using risk factor catagories. Circulation 1998;97:1837–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hippisley-Cox J, Coupland C, Robson J, Sheikh A, Brindle P Predicting risk of type 2 diabetes in England and Wales: prospective derivation and validation of QDScore. BMJ 2009;338:b880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parkes G, Greenhalgh T, Griffin M, Dent R Effect on smoking quit rate of telling patients their lung age: the Step2quit randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2008;336:598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Department of Health. Putting prevention first – vascular checks: risk assessment and management. Annex 1: options stage impact assessment for vascular risk assessments, 2008.

- 13.Patel K, Minhas R, Gill P, Khunti K, Clayton R Vascular risk checks in the UK: strategic challenges for implementation. Heart 2009;95:866–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kulzer BH, Gorges N, Schwarz D, Haak P Prevention of Diabetes Self Management Programme (PREDIAS): Effects on Weight, Metabolic Risk Factors and behavioural Outcomes. Diabetes Care 2009;32:1143–46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spijkerman A, Dekker J, Nijpels G, et al. Microvascular Complications at Time of Diagnosis of Type 2 Diabetes Are Similar Among Diabetic Patients Detected by Targeted Screening and Patients Newly Diagnosed in General Practice: The Hoorn Screening Study. Diabetes Care 2003;26:2604–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Higgins JPT, Green S Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.0.2 [updated September 2009]: The Cochrane Collaboration, 2009

- 17.Wister A, Loewen N, Kennedy-Symonds H, McGowan B, McCoy B, Singer J One-year follow-up of a therapeutic lifestyle intervention targeting cardiovascular disease risk. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association Journal 2007;177:859–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meland E, lærum E, Ulvik R Effectivness of two preventitive interventions for coronary heart disease in primary care. Scandinavian Journal of Primary Health Care 1997;15:57–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ketola E, Mäkelä M, Klockars M Individualised multifactorial lifestyle intervention trial for high-risk cardiovascular patients in primary care. The British Journal of General Practice: the Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners 2001:291–4 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Multiple risk factor intervention trial Research Group Multiple risk factor intervention trial. Risk factor changes and mortality results. JAMA 1982;248:1465–77 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wood D, Kinmouth A, Davies G, et al. Randomised Controlled Trial Evaluating Cardiovascular Screening and Intervention in General Practice: principal results of British Family Heart Study. BMJ 1994;308:313–20 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kornitzer M, Rose G WHO European Collaborative Trial of multifactorial prevention of coronary heart disease. Prev Med 1985;14:272–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Edwards AG, Evans R, Dundon J, Haigh S, Hood K, Elwyn GJ Personalised Risk Communuication for Informed Decision Making about Taking Screening Tests (Review). The Cochrane Library 2009;Issue 1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Collins R, MacMahon S Blood pressure, antihypertensive treatment and the risk of stroke and coronary heart disease. British Medical Bulletin 1994;50:272–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study Group Randomised trial of lowering in 4444 patients with coronary heart disease: the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S). Lancet 1994;344:1383–89 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frank E Benefits of Stopping Smoking. West J Med 1993;159:83–86 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khunti K, Ganguli S, Baker R, Lowy A Features of primary care associated with variations in process and outcome of care of people with diabetes. British Journal of General Practice 2001;51:356–60 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hippisley-Cox J, O'Hanlon S, Coupland C Association of deprivation, ethnicity, and sex with quality indicators for diabetes: population based survey of 53,000 patients in primary care. BMJ 2004;329:1267–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vartiainen E, Puska P, Jousilahti P, Huttunen J The success of prevention of CHD in finland. Suomen Laakarilehti 1998;53:2023–26 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Department of Health. Putting Prevention First. Vascular checks: Risk Assesment and Managment. London, 2008.