Abstract

Cystic fibrosis liver disease (CFLD) is a rapidly progressive biliary fibrosis, resembling primary sclerosing cholangitis that develops in 5–10% of patients with cystic fibrosis. Further research and evaluation of therapies are hampered by the lack of a mouse model for CFLD. Although primary sclerosing cholangitis is linked to both ulcerative colitis and loss of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) ion channel function, induction of colitis with dextran sodium sulfate (DSS) in cftr−/− mice causes bile duct injury but no fibrosis. Since profibrogenic modifier genes are linked to CFLD, we examined whether subthreshhold doses of the profibrogenic xenobiotic 3,5-diethoxycarbonyl-1,4-dihydrocollidine (DDC), along with DSS-induced colitis, lead to bile duct injury and liver fibrosis in mice that harbor loss of CFTR function. Exon 10 heterozygous (cftr+/−) and homozygous (cftr−/−) mice treated with DDC demonstrated extensive mononuclear cell inflammation, bile duct proliferation, and periductular fibrosis. In contrast, wild-type (cftr+/+) littermates did not develop bile duct injury or fibrosis. Histological changes corresponded to increased levels of alkaline phosphatase, hydroxyproline, and expression of profibrogenic transcripts for transforming growth factor-β1, transforming growth factor-β2, procollagen α1(I), and tissue inhibitor of matrix metaloproteinase-1. Immunohistochemistry demonstrated fibrosis and activation of periductal fibrogenic cells based on positive staining for lysyl oxidase-like-2, α-smooth muscle actin, and collagen I. These data demonstrate that subthreshold doses of DDC, in conjunction with DSS-induced colitis, results in bile duct injury and periductal fibrosis in mice with partial or complete loss of CFTR function and may represent a useful model to study the pathogenic mechanisms by which CFTR dysfunction predisposes to fibrotic liver disease and potential therapies.

Keywords: hepatic fibrogenesis, cystic fibrosis

cystic fibrosis (cf) liver disease (CFLD) and primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) share many similarities, including clinical presentation, imaging abnormalities with biliary strictures in the intra- and/or extrahepatic biliary tree, and histopathological findings of bile duct injury (bile duct proliferation, pericholangitic inflammation, bile ductular plugs, and cirrhosis). PSC is associated with inflammatory bowel disease, especially ulcerative colitis (13). Our group has shown an increased prevalence of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) single allelic mutations and abnormal CFTR ion channel function in adults and children with PSC, suggesting that CFTR dysfunction lowers the threshold to bile duct inflammation and fibrosis (24, 32). Our laboratory previously reported the development of a murine mouse model of bile duct injury in exon 10 CF knockout mice (cftr−/−) by inducing colitis with oral dextran sodium sulfate (DSS). This model resulted in bile duct injury and proliferation similar in appearance to PSC; however, the liver disease in this mouse model was patchy and did not progress to fibrosis (6). Thus the loss of CFTR function alone with colitis was insufficient to induce fibrogenesis.

CFLD is the third most common cause of death among patients with CF and accounts for 2.5% overall mortality in this population (18, 30). Because of the lack of a consistent definition, the prevalence and outcome data in CFLD are poorly characterized. The prevalence of CFLD, including asymptomatic CF patients with isolated abnormal liver blood tests or abnormal imaging studies, can be as high as 25–40% (10, 11); however, the prevalence of advanced CFLD, as defined by focal biliary cirrhosis and portal hypertension, is 5–10%. Thus loss of CFTR function alone is not sufficient to cause liver disease in these patients and indicates that other factors, including modifier genes, must play a pathogenic role (31). The fact that the peak incidence of CFLD occurs around or before puberty indicates that this is an early event (4, 11, 12, 30). Although no specific CFTR mutations have been identified leading to CFLD, male sex, α-1 antitrypsin Z allele, and transforming growth factor (TGF)-β polymorphisms are associated (4, 7, 11, 18, 30). In addition, CF patients with CFLD tend to have a greater likelihood of abnormal nutritional parameters and growth failure, CF-related diabetes, pancreatic insufficiency, advanced pulmonary morbidity, and an earlier mortality (10, 29).

The primary pathogenic mechanism appears to be fibrogenesis within the liver involving the bile ductules, leading to focal biliary cirrhosis. CFTR is localized on the apical membrane of the cholangiocyte, where it is central in regulating bile flow into the biliary tract. With loss of CFTR function, there is decreased bile flow and inspissation, leading to an obstructive process, which, in turn, leads to a buildup of toxic bile acids, upregulation of inflammatory cytokine production, activation of portal fibroblasts/hepatic stellate cells, and formation of peribiliary fibrosis (22). However, the fact that most CF patients have this abnormality and as many as 40% demonstrate abnormal hepatic imaging and biochemistry, yet only 5–10% develop focal biliary cirrhosis and portal hypertension, implies that other factors must be in play to cause advanced CFLD.

Fickert et al. (15) have shown that the xenobiotic 3,5-diethoxycarbonyl-1,4-dihydrocollidine (DDC) leads to bile duct inflammation and fibrosis at doses of 10 mg/day in wild-type (WT) mice. Since profibrogenic modifier genes (31) have been linked to the development of CFLD, we hypothesized that bile duct injury would develop in cftr+/− and cftr−/− mice, but not WT littermates, exposed to a subthreshold dose of DDC following induction of colitis with DSS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Breeding of mice.

All of the experiments were carried out under protocols approved by the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Animal Care Committee. A breeding colony was established with University of North Carolina heterozygous (HET) cftr+/− exon 10 knockout mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME). The tails of 14-day-old mice were clipped and processed for analysis of genotype. WT (cftr+/+), HET (cftr+/−), and CF (cftr−/−) mice were weaned at an average of 23 days and placed on a water and Peptamen (Nestle Clinical Nutrition, Deerfield, IL) diet ad libitum, as described before (6).

Induction of colitis and liver fibrosis.

To induce colitis, CF, HET, and their WT littermates (5 mice/group) at 6 wk of age were fed with 100 mg DSS/day (ICN Biomedicals, Costa Mesa, CA) dissolved in 15 ml of Peptamen for 7–10 days, as previously published (6). The colitis was monitored by fecal occult blood test using a hemoccult test kit (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA). The mice were concurrently fed with 1 mg/day of DDC mixed in Peptamen for 28 days. The volume of Peptamen consumed was measured on a daily basis by using specific feeders. The mortality rate was similar across all groups at 20% during the first 10 days when colitis was being induced.

Sample collection and analysis.

At the end of 28 days of feeding, the mice were euthanized with carbon dioxide. Blood was taken immediately after death by direct cardiac puncture and was centrifuged, and plasma was collected for alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate transaminase (AST), and alkaline phosphatase (AP). Plasma ALT, AST, and AP levels were measured using a Catalyst Dx Chemistry Analyzer (Idexx Laboratories).

The livers were excised and weighed. Pieces of liver from different lobes were fixed in 10% formalin for histology or immediately frozen and stored for RNA extraction and immunohistochemistry. Liver tissues were also collected and weighed for hydroxyproline measurements.

Liver histology and immunohistochemistry.

Formalin-fixed liver tissues were embedded in paraffin, cut in cross section, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin for histology and with Sirius red to assess for fibrosis. The Sirius red positive areas were quantified using iVision 4.09 software from Biovision Technologies (Exton, PA). Gilead Sciences (Foster City, CA) processed fresh frozen liver sections for immunohistochemistry, as previously described (3). Liver tissue was stained with antibodies specific to the fibrosis markers lysyl oxidase-like-2 (LOXL2), a profibrogenic protein previously shown to be important in the pathogenesis of hepatic fibrosis (3), α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), and collagen I and their appropriately conjugated secondary antibodies. Liver tissue was also stained with antibodies specific to the F4/80 antigen, a pan-macrophage marker. The anti-mouse F4/80 antibodies were obtained from eBiosciences (San Diego, CA).

Bile duct injury scoring.

Quantitation of bile duct injury in the liver specimens was based on examination of the following histological features: 1) epithelial injury, characterized by intraepithelial inflammatory mononuclear cell infiltration, 2) bile duct proliferation, 3) bile duct angulation, and 4) fibrosis. Each of these four features was scored as 0 (absent), 1 (mild), 2 (moderate), or 3 (severe) and then summated for a maximum score of 12 (6).

Liver hydroxyproline determination.

Hepatic collagen content was quantified biochemically by determining liver hydroxyproline, as previously described (25). Hydroxyproline content was measured at 565 nm using a hydroxyproline standard curve. Based on relative hepatic hydroxyproline (per 100 mg of wet liver), total hepatic hydroxyproline was calculated (per total liver, as obtained by multiplying liver weights with relative hepatic hydroxyproline).

Quantitative real-time-PCR of profibrogenic transcripts.

Snap-frozen liver tissues from different lobes were homogenized; total RNA was extracted using RNA STAT-60 (Tel-Test, Friendswood, TX), according to the manufacturer's recommendations. cDNA was obtained by reverse transcription of 1 μg of total RNA, and relative transcript levels were quantified by real-time-PCR on a LightCycler 1.5 instrument (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) using the TaqMan principle, as previously described (26, 27). TNF-α, TGF-β1, TGF-β2, procollagen α1(I), and tissue inhibitor of matrix metaloproteinase-1 (TIMP-1) levels were measured. The housekeeping gene β2-microglobulin was amplified for normalization. TaqMan probes and primer sets (summarized in Table 1) were designed using the Primer Express software (Perkin Elmer, Foster City, CA) based on published sequences and validated as described before (26, 27).

Table 1.

Primer sequences for quantitative RT-PCR

| Target Gene | 5′-Primer | TaqMan Probe | 3′-Primer |

|---|---|---|---|

| β2MG | GATACATACGCCTGCAGAGTTAA | GATACATACGCCTGCAGAGTTAA CATGTG | ATGAATCTTCAGAGCATCATGAT |

| Procollagen α1(1) | TCCGGCTCCTGCTCCTCTTA | TTCTTGGCCATGCGTCAGGAGGG | GTATGCAGCTGACTTCAGGGATGT |

| TGF-β1 | AGAGGTCACCCGCGTGCTAA | ACCGCAACAACGCCATCTATGAGAAAACCA | TCCCGAATGTCTGACGTATTGA |

| TGF-β2 | GTCCAGCCGGCGGAA | CGCTTTGGATGCTGCCTACTGCTTTAGAAAT | GCGAAGGCAGCAATTATCCT |

| MMP-2 | CCGAGGACTATGACCGGGATAA | TCTGCCCCGAGACCGCTATGTCCA | CTTGTTGCCCAGGAAAGTGAAG |

| TIMP-1 | TCCTCTTGTTGCTATCACTGATAGCTT | TTCTGCAACTCGGACCTGGTCATAAGG | CGCTGGTATAAGGTGGTCTCGTT |

| TNF-α | GGGCCACCACGCTCTTC | ATGAGAAGTTCCCAAATGGCCTCCCTC | GGTCTGGGCCATAGAACTGATG |

β2MG, β2 microglobulin; TGF-β, transforming growth factor-β; MMP-2, matrix metalloproteinase-2; TIMP-I, tissue inhibitor of matrix metaloproteinase-1; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α.

Statistical analysis.

The results are expressed as means ± SE. There was a minimum of three to five mice per group. Data were analyzed by Student's t-test with comparisons between HET and WT mice, CF and WT mice, and HET and CF mice. All analyses were performed using STATA statistical software, version 11 (StataCorp) and GraphPad Prism version 5.00 for Windows, GraphPad Software (San Diego, CA, www.graphpad.com).

RESULTS

Administration of DDC following induction of colitis in HET (cftr+/−) and CF (cftr−/−) mice results in bile duct injury with fibrosis.

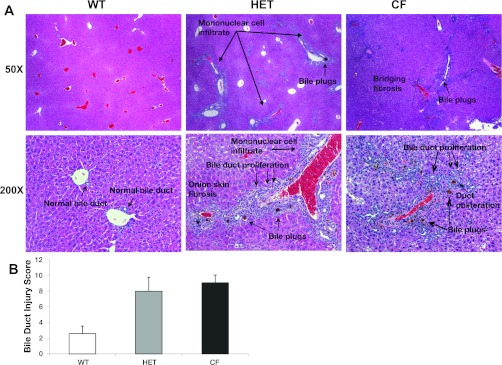

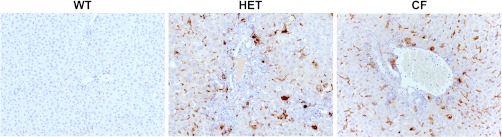

Administration of a subthreshold dose of DDC (1 mg/day) in conjunction with DSS to the Peptamen diet of cftr+/− mice (HET) and cftr−/− mice (CF) led to extensive mononuclear cell inflammation, bile duct proliferation, periductular fibrosis with areas of duct obliteration with “onion skin” type fibrosis, and bridging fibrosis (Fig. 1A, hematoxylin and eosin histology; n = 5 animals/group). Porphyrin bile plugs occluding some of the lumina of small and large bile ducts were also present, characteristic of DDC treatment. Quantitation of these histological changes is shown in Fig. 1B. Further characterization of the mononuclear inflammatory cells seen on hematoxylin and eosin staining demonstrated increased periportal and sinusoidal macrophage infiltration in the livers of CF and HET compared with WT controls based on immunohistochemistry (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

A: liver and bile duct injury occurs in heterozygous (HET) and cystic fibrosis (CF) mice, but not wild-type (WT) littermates. No liver abnormalities were seen with 3,5-diethoxycarbonyl-1,4-dihydrocollidine (DDC) alone in the absence of dextran. Hematoxylin and eosin staining was used. Original magnification: ×50 (top) and ×200 (bottom). B: bile duct injury score. Increased bile duct injury is seen in HET and CF mice compared with WT littermates (n = 5 per group). Values are means ± SD.

Fig. 2.

HET and CF mice demonstrate periportal and sinusoidal macrophage infiltration, as evidenced by immunohistochemistry using antibodies to the pan macrophage marker anti-mouse F4/80 antigen. Original magnification, ×200.

In contrast, WT littermates (cftr+/+) did not develop evidence of bile duct injury or fibrosis with this subthreshold dose of DDC and had very few porphyrin plugs seen within bile ducts. With higher doses of DDC (3 mg/day), along with 100 mg/day DSS, all animals, including WT mice, demonstrated similar severe bile duct inflammatory changes, fibrosis, and porphyrin intraductular plugs, with no difference in induced liver injury between CF, HET, and WT mice (data not shown). Administration of 1 mg/day of DDC alone in the absence of DSS resulted in no observed pathological changes in CF, HET, or WT mice (data not shown).

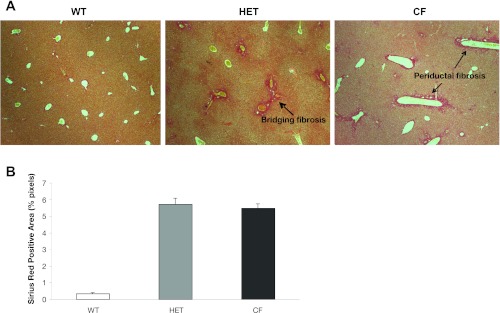

Liver histology for Sirius red staining and immunohistochemistry demonstrates periductular and bridging fibrosis.

Sirius red staining for fibrosis (Fig. 3A) demonstrates no evidence of fibrosis in low-dose DDC-treated WT livers, while overt bridging fibrosis was seen in HET and CF mice. Total Sirius red positive area, expressed as percentage of total pixels on the liver section (Fig. 3B), demonstrates quantitatively the overt increase in Sirius red-stained collagen in HET and CF mice compared with WT mice.

Fig. 3.

A: Sirius red staining demonstrates increased fibrosis in both HET and CF mice. Original magnification, ×50. B: Sirius red quantitation (n = 5 per group). Values are means ± SD.

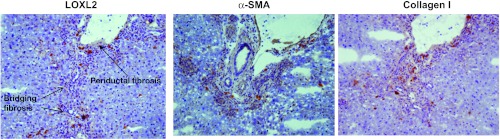

Further assessment for the presence of fibrosis and activated fibrogenic cell phenotypes was evaluated by immunohistochemistry for the fibrogenesis protein markers LOXL2, α-SMA, and collagen I (Fig. 4). These studies were conducted in HET mice given their similar histological appearance to CF mice. Evident are the inflammatory infiltrates around the portal tracts and bile duct proliferations. LOXL2 expression is present along the periductal regions and within the stroma of the surrounding tissue parenchyma. LOXL2 colocalizes with α-SMA, a marker of activated myofibroblasts and hepatic stellate cells (2, 21) and collagen I. Staining with secondary antibody alone did not show any reaction product (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

HET mice develop fibrosis, as evidenced by the presence of profibrogenic proteins by immunohistochemistry. Sequential sections were stained with lysyl oxidase-like-2 (LOXL2), α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), and collagen I. Original magnification, ×200.

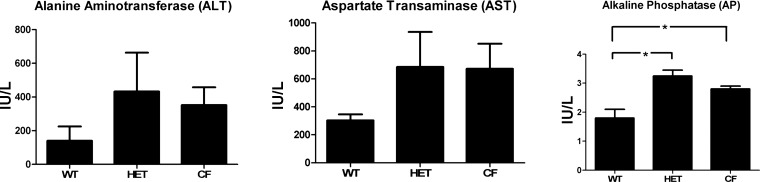

HET and CF mice demonstrate increased levels of AP compared with WT mice.

Plasma levels of AP were elevated in HET and CF mice compared with WT mice (Fig. 5). The mean value for WT mice was 1.78 ± 0.34 IU/l, compared with 3.25 ± 0.18 IU/l for HET mice (P = 0.009) and 2.81 ± 0.10 IU/l for CF mice, which was significantly different compared with WT mice (P = 0.02), but not different from HET mice. Comparison of the three groups showed no differences in the plasma levels of ALT and AST.

Fig. 5.

Alkaline phosphatase (AP) is increased in HET and CF mice compared with WT mice. ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate transaminase. Values are means ± SE. *P < 0.05.

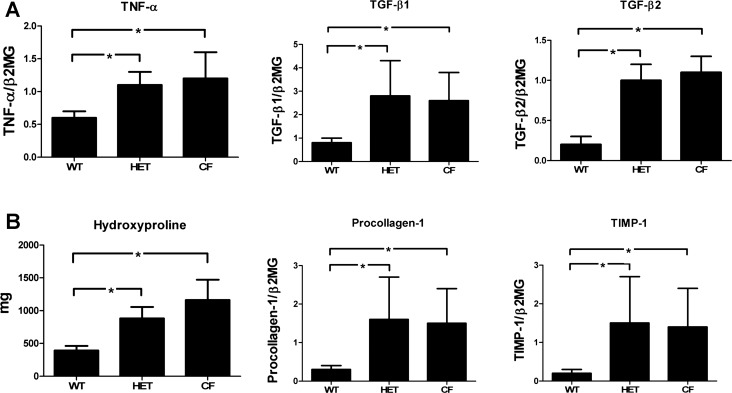

HET and CF mice demonstrate increased hepatic levels of proinflammatory and profibrogenic transcripts compared with WT mice.

The expression of TNF-α, TGF-β1, TGF-β2, procollagen α1(I), and TIMP-1 transcripts showed a statistically significant increase (P < 0.05) in HET and CF mice compared with their WT littermates (Fig. 6). There were no differences between CF and HET mice.

Fig. 6.

Proinflammatory (A) and profibrogenic (B) mediators are increased in HET and CF mice compared with WT mice. TNF-α, transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1, TGF-β2, procollagen α1(I), and tissue inhibitor of matrix metaloproteinase-1 (TIMP-1) are expressed as mRNA transcript levels normalized to the housekeeping gene β2-microglobulin (β2MG). Hydroxyproline is expressed as total liver hydroxyproline content in milligrams (mg). Values are means ± SE. *P < 0.05.

Total hepatic hydroxyproline content (mg) was significantly increased in CF (1,161.75 ± 155.66 mg) and HET (883.0 ± 87.60 mg) compared with WT (394.75 ± 33.82 mg) mice (P = 0.003 and 0.002, respectively). There was no difference in total hydroxyproline content between CF and HET mice.

DISCUSSION

We demonstrate that partial or complete loss of CFTR function, in combination with induced colitis with DSS and subthreshold exposure to the xenobiotic DDC, results in a reproducible, robust animal model of bile duct injury and liver fibrosis resembling the histological features and mononuclear infiltrate found in fibrotic liver disease, such as PSC and CFLD (8, 34). The full extent of disease was characterized by examination of histological features, including immunohistochemistry of mononuclear-derived macrophages, measurements of tissue proinflammatory and profibrogenic markers, and quantification of serologic liver function tests. The fact that similar results were obtained in both hetero- and homozygous mice (cftr+/− and cftr−/−, respectively) indicate that 50% loss of CFTR function is sufficient to maximize the response to DDC as chemical sensitizer. This is consistent with our laboratory's data in humans with PSC that a single allelic mutation in CFTR is sufficient to predispose these individuals with colitis to liver disease characterized by bile duct injury and biliary fibrosis (32).

Understanding what leads to cholangiocyte activation and downstream fibrogenesis is critical in developing therapeutics and strategies in diseases characterized by bile duct injury (28). Previous animal models have taken advantage of chemical or mechanical inducers of biliary disease, but have not defined the role of loss of CFTR in this process. Chemical inducers of fibrosis, such as carbon tetrachloride and thioacetamide, induce an effect on the hepatocyte, but do so through their toxic effects (20). Bile duct ligation provides an acute, definitive mechanical inducer of secondary biliary fibrosis, but does not allow for evaluation of early mechanisms that may lead to CFTR-related liver disease in the absence of complete biliary obstruction (19). MDR2 knockout mice demonstrate impaired phospholipid secretion into bile, leading to biliary ductal fibrosis; however, there is a lack of a major inflammatory component (14, 26). In addition, the human homologue, MDR3, has not been found to be associated with PSC. Other knockout models, including ΔF508 (17) and exon 10 congenic cftr−/− mice (5), variably demonstrate peri-cholangitic inflammation and have only minimal fibrosis after 90 days of age, while, α-1 antitrypsin Z mutation by itself is not sufficient to induce fibrosis (23).

In a xenobiotic-induced mouse model of biliary fibrosis, a 10 mg/day DDC supplemented diet for 8 wk led to cholangiocyte activation and progressive bile duct injury and liver fibrosis (15), capturing the essential time-oriented longitudinal features of cholestatic cholangiopathies. However, we found that high doses of DDC did not differentiate the contribution of CFTR dysfunction in progressive liver injury; i.e., mice fed 3 mg/day of DDC along with 100 mg/day DSS did not demonstrate variations in induced liver injury between CF, HET, and WT mice, with all animals demonstrating similar severe bile duct inflammatory changes, fibrosis, and porphyrin intraductular plugs. In addition, 1 mg/day of DDC alone in the absence of DSS-induced colitis did not result in any pathological changes in the livers of CF, HET, or WT mice. Thus, in the present study, a subthreshold dose of DDC with DSS-induced colitis defines a murine model that allows examination of the role of CFTR as important modifier gene in the pathogenesis of bile duct injury and biliary liver fibrosis, as observed in fibrotic human CFLD. In this model, we establish that partial or complete loss of CFTR dysfunction predisposes to bile duct injury, and this process requires both colitis and a (subthreshold) “second hit” to the cholangiocytes.

Our model with subthreshold DDC administration in the setting of the loss of CFTR function demonstrates evidence for cholangiocyte activation with increased mRNA expression of proinflammatory TNF-α and profibrogenic TGF-β1, TGF-β2, procollagen α1(I), and TIMP-1 (15). This parallels the results from liver biopsies in children with CFLD, where TGF-β protein and TGF-β1 mRNA expression were present in bile duct epithelial cells and correlated with the degree of hepatic fibrosis (21).

Additionally, our data demonstrated that, coupled with cholangiocyte activation, are periductal inflammatory infiltrates, bile duct proliferation, and histological features of fibrogenesis manifested as bridging portal fibrosis and bile duct onion-skin-like fibrosis and obliteration. The presence of fibrosis was confirmed by increased collagen accumulation, as measured via hydroxyproline content and Sirius red morphometry, the above mentioned profibrogenic transcripts, and positive immunohistochemistry staining of LOXL2, α-SMA, and collagen I in the periductular regions.

Additional strengths of our model include diffuse involvement of most portal tracts, and the presence of fibrosis, which was not seen in DSS-induced colitis alone (6). In the present model, we did not see cirrhosis; however, this is likely the result of the relatively short, 4-wk duration of our study.

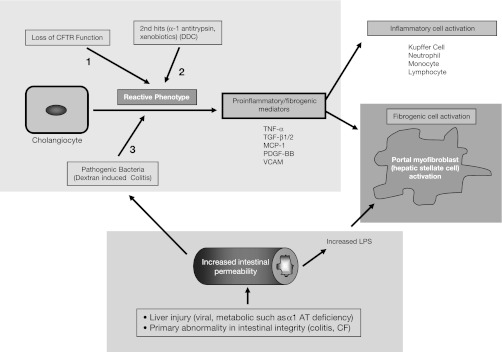

Our data would indicate that three factors are required to elicit bile duct injury and periductular fibrosis in our mouse model. The first is loss of CFTR function. The second is the presence of profibrogenic activators, which, in patients, includes α-1 antitrypsin and TGF-β, both being implicated as modifier genes in patients with CF who develop CFLD (4). In our murine model, the subthreshold xenobiotic DDC is causal as a fibrogenic activator. The third factor is increased intestinal permeability and inflammation, which can be a primary abnormality altering the intestinal integrity, such as that seen in CF or in colitis, which is the major predisposing factor to PSC in humans (9). Accordingly, in our model, DSS was used to induce colitis and alter intestinal permeability (33). Previously published literature has shown that, also, any type of liver injury, including viral or metabolic causes, such as α-1 antitrypsin deficiency, will also lead to increased intestinal permeability, with increased translocation of intestinal bacteria or toxins (1, 16). Thus our results indicate that all three aspects, as shown in Fig. 7, play a major role under these conditions in cholangiocyte transformation, leading to the production of proinflammatory and profibrogenic mediators. Since our model is dependent on the presence of the (hetero- or homozygous) cftr mutation, it should be useful for further studies into the pathogenesis of CFLD and especially for the testing of novel therapies aimed at preventing progression of CFLD to biliary cirrhosis.

Fig. 7.

Putative model for cholangiocyte activation to a reactive phenotype in cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR)-related biliary disease. MCP-1, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; PDGF, platelet-derived growth factor.

GRANTS

The Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (Award FREEDM06A0 to S. D. Freedman) funded this work. The work of C. R. Martin was supported by the Program for Faculty Development and Diversity supported by Harvard Catalyst, The Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center, from the National Center for Research Resources (Award no. UL1 RR 025758 and financial contributions from Harvard University and its affiliated academic health care centers). The work of Y. Popov and D. Schuppan was, in part, supported by the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (Grant Schupp08G0).

DISCLAIMER

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of Harvard Catalyst, Harvard University and its affiliated academic health care centers, the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

C.R.M., M.M.Z., and S.D.F. analyzed data; C.R.M., M.M.Z., G.A.K., Y.P., D.S., and S.D.F. interpreted results of experiments; C.R.M., G.A.K., D.S., and S.D.F. prepared figures; C.R.M., G.A.K., Y.P., D.S., and S.D.F. drafted manuscript; C.R.M., M.M.Z., G.A.K., A.Q.B., E.C., Y.P., D.S., and S.D.F. edited and revised manuscript; C.R.M., M.M.Z., G.A.K., A.Q.B., E.C., Y.P., D.S., and S.D.F. approved final version of manuscript; M.M.Z. and S.D.F. conception and design of research; M.M.Z., A.Q.B., and E.C. performed experiments.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful for the technical expertise provided by Haben Ghermazien of Gilead Sciences-Biologics & Target Biology/Biology Department for performing immunohistochemistry on the liver samples and staining for select fibrosis markers, and by Deanna Y. Sverdlov (BIDMC) for performing the hydroxyproline assays.

REFERENCES

- 1. Albillos A, de la Hera A, Gonzalez M, Moya JL, Calleja JL, Monserrat J, Ruiz-del-Arbol L, Alvarez-Mon M. Increased lipopolysaccharide binding protein in cirrhotic patients with marked immune and hemodynamic derangement. Hepatology 37: 208– 217, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Badid C, Desmouliere A, Babici D, Hadj-Aissa A, McGregor B, Lefrancois N, Touraine JL, Laville M. Interstitial expression of alpha-SMA: an early marker of chronic renal allograft dysfunction. Nephrol Dial Transplant 17: 1993– 1998, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Barry-Hamilton V, Spangler R, Marshall D, McCauley S, Rodriguez HM, Oyasu M, Mikels A, Vaysberg M, Ghermazien H, Wai C, Garcia CA, Velayo AC, Jorgensen B, Biermann D, Tsai D, Green J, Zaffryar-Eilot S, Holzer A, Ogg S, Thai D, Neufeld G, Van Vlasselaer P, Smith V. Allosteric inhibition of lysyl oxidase-like-2 impedes the development of a pathologic microenvironment. Nat Med 16: 1009– 1017, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bartlett JR, Friedman KJ, Ling SC, Pace RG, Bell SC, Bourke B, Castaldo G, Castellani C, Cipolli M, Colombo C, Colombo JL, Debray D, Fernandez A, Lacaille F, Macek M, Jr., Rowland M, Salvatore F, Taylor CJ, Wainwright C, Wilschanski M, Zemkova D, Hannah WB, Phillips MJ, Corey M, Zielenski J, Dorfman R, Wang Y, Zou F, Silverman LM, Drumm ML, Wright FA, Lange EM, Durie PR, Knowles MR. Genetic modifiers of liver disease in cystic fibrosis. JAMA 302: 1076– 1083, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Beharry S, Ackerley C, Corey M, Kent G, Heng YM, Christensen H, Luk C, Yantiss RK, Nasser IA, Zaman M, Freedman SD, Durie PR. Long-term docosahexaenoic acid therapy in a congenic murine model of cystic fibrosis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 292: G839– G848, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Blanco PG, Zaman MM, Junaidi O, Sheth S, Yantiss RK, Nasser IA, Freedman SD. Induction of colitis in cftr−/− mice results in bile duct injury. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 287: G491– G496, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brazova J, Sismova K, Vavrova V, Bartosova J, Macek M, Jr, Lauschman H, Sediva A. Polymorphisms of TGF-beta1 in cystic fibrosis patients. Clin Immunol 121: 350– 357, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cameron RG, Blendis LM, Neuman MG. Accumulation of macrophages in primary sclerosing cholangitis. Clin Biochem 34: 195– 201, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cariello R, Federico A, Sapone A, Tuccillo C, Scialdone VR, Tiso A, Miranda A, Portincasa P, Carbonara V, Palasciano G, Martorelli L, Esposito P, Carteni M, Del Vecchio Blanco C, Loguercio C. Intestinal permeability in patients with chronic liver diseases: its relationship with the aetiology and the entity of liver damage. Dig Liver Dis 42: 200– 204, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chryssostalis A, Hubert D, Coste J, Kanaan R, Burgel PR, Desmazes-Dufeu N, Soubrane O, Dusser D, Sogni P. Liver disease in adult patients with cystic fibrosis: a frequent and independent prognostic factor associated with death or lung transplantation. J Hepatol 55: 1377– 1382, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Colombo C, Battezzati PM, Crosignani A, Morabito A, Costantini D, Padoan R, Giunta A. Liver disease in cystic fibrosis: a prospective study on incidence, risk factors, and outcome. Hepatology 36: 1374– 1382, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Debray D, Kelly D, Houwen R, Strandvik B, Colombo C. Best practice guidance for the diagnosis and management of cystic fibrosis-associated liver disease. J Cyst Fibros 10, Suppl 2: S29–S36, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fausa O, Schrumpf E, Elgjo K. Relationship of inflammatory bowel disease and primary sclerosing cholangitis. Semin Liver Dis 11: 31– 39, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fickert P, Fuchsbichler A, Wagner M, Zollner G, Kaser A, Tilg H, Krause R, Lammert F, Langner C, Zatloukal K, Marschall HU, Denk H, Trauner M. Regurgitation of bile acids from leaky bile ducts causes sclerosing cholangitis in Mdr2 (Abcb4) knockout mice. Gastroenterology 127: 261– 274, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fickert P, Stoger U, Fuchsbichler A, Moustafa T, Marschall HU, Weiglein AH, Tsybrovskyy O, Jaeschke H, Zatloukal K, Denk H, Trauner M. A new xenobiotic-induced mouse model of sclerosing cholangitis and biliary fibrosis. Am J Pathol 171: 525– 536, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Frances R, Zapater P, Gonzalez-Navajas JM, Munoz C, Cano R, Moreu R, Pascual S, Bellot P, Perez-Mateo M, Such J. Bacterial DNA in patients with cirrhosis and noninfected ascites mimics the soluble immune response established in patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Hepatology 47: 978– 985, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Freudenberg F, Broderick AL, Yu BB, Leonard MR, Glickman JN, Carey MC. Pathophysiological basis of liver disease in cystic fibrosis employing a DeltaF508 mouse model. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 294: G1411– G1420, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Herrmann U, Dockter G, Lammert F. Cystic fibrosis-associated liver disease. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 24: 585– 592, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kountouras J, Billing BH, Scheuer PJ. Prolonged bile duct obstruction: a new experimental model for cirrhosis in the rat. Br J Exp Pathol 65: 305– 311, 1984 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. LeSage GD, Benedetti A, Glaser S, Marucci L, Tretjak Z, Caligiuri A, Rodgers R, Phinizy JL, Baiocchi L, Francis H, Lasater J, Ugili L, Alpini G. Acute carbon tetrachloride feeding selectively damages large, but not small, cholangiocytes from normal rat liver. Hepatology 29: 307– 319, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lewindon PJ, Pereira TN, Hoskins AC, Bridle KR, Williamson RM, Shepherd RW, Ramm GA. The role of hepatic stellate cells and transforming growth factor-beta(1) in cystic fibrosis liver disease. Am J Pathol 160: 1705– 1715, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lewindon PJ, Shepherd RW, Walsh MJ, Greer RM, Williamson R, Pereira TN, Frawley K, Bell SC, Smith JL, Ramm GA. Importance of hepatic fibrosis in cystic fibrosis and the predictive value of liver biopsy. Hepatology 53: 193– 201, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mencin A, Seki E, Osawa Y, Kodama Y, De Minicis S, Knowles M, Brenner DA. Alpha-1 antitrypsin Z protein (PiZ) increases hepatic fibrosis in a murine model of cholestasis. Hepatology 46: 1443– 1452, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pall H, Zielenski J, Jonas MM, DaSilva DA, Potvin KM, Yuan XW, Huang Q, Freedman SD. Primary sclerosing cholangitis in childhood is associated with abnormalities in cystic fibrosis-mediated chloride channel function. J Pediatr 151: 255– 259, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Popov Y, Patsenker E, Bauer M, Niedobitek E, Schulze-Krebs A, Schuppan D. Halofuginone induces matrix metalloproteinases in rat hepatic stellate cells via activation of p38 and NFkappaB. J Biol Chem 281: 15090– 15098, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Popov Y, Patsenker E, Fickert P, Trauner M, Schuppan D. Mdr2 (Abcb4)−/− mice spontaneously develop severe biliary fibrosis via massive dysregulation of pro- and antifibrogenic genes. J Hepatol 43: 1045– 1054, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Popov Y, Patsenker E, Stickel F, Zaks J, Bhaskar KR, Niedobitek G, Kolb A, Friess H, Schuppan D. Integrin alphavbeta6 is a marker of the progression of biliary and portal liver fibrosis and a novel target for antifibrotic therapies. J Hepatol 48: 453– 464, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Popov Y, Schuppan D. Targeting liver fibrosis: strategies for development and validation of antifibrotic therapies. Hepatology 50: 1294– 1306, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rowland M, Gallagher CG, O'Laoide R, Canny G, Broderick A, Hayes R, Greally P, Slattery D, Daly L, Durie P, Bourke B. Outcome in cystic fibrosis liver disease. Am J Gastroenterol 106: 104– 109, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rudnick DA. Cystic fibrosis associated liver disease–when will the future be now? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 54: 312, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Salvatore F, Scudiero O, Castaldo G. Genotype-phenotype correlation in cystic fibrosis: the role of modifier genes. Am J Med Genet 111: 88– 95, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sheth S, Shea JC, Bishop MD, Chopra S, Regan MM, Malmberg E, Walker C, Ricci R, Tsui LC, Durie PR, Zielenski J, Freedman SD. Increased prevalence of CFTR mutations and variants and decreased chloride secretion in primary sclerosing cholangitis. Hum Genet 113: 286– 292, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Yan Y, Kolachala V, Dalmasso G, Nguyen H, Laroui H, Sitaraman SV, Merlin D. Temporal and spatial analysis of clinical and molecular parameters in dextran sodium sulfate induced colitis. PLos One 4: e6073, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zimmermann HW, Seidler S, Nattermann J, Gassler N, Hellerbrand C, Zernecke A, Tischendorf JJ, Luedde T, Weiskirchen R, Trautwein C, Tacke F. Functional contribution of elevated circulating and hepatic non-classical CD14CD16 monocytes to inflammation and human liver fibrosis. PLos One 5: e11049, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]