Abstract

Although pharmacological and interventional advances have reduced the morbidity and mortality of ischemic heart disease, there is an ongoing need for novel therapeutic strategies that prevent or reverse progressive ventricular remodeling following myocardial infarction, the process that forms the substrate for ventricular failure. The development of cell-based therapy as a strategy to repair or regenerate injured tissue offers extraordinary promise for a powerful anti-remodeling therapy. In this regard, the field of cell therapy has made major advancements in the past decade. Accumulating data from preclinical studies have provided novel insights into stem cell engraftment, differentiation, and interactions with host cellular elements, as well as the effectiveness of various methods of cell delivery and accuracy of diverse imaging modalities to assess therapeutic efficacy. These findings have in turn guided rationally designed translational clinical investigations. Collectively, there is a growing understanding of the parameters that underlie successful cell-based approaches for improving heart structure and function in ischemic and other cardiomyopathies.

Keywords: myocardial infarction, stem cells, mesenchymal stem cells, bone marrow cells, heart failure

this article is part of a collection on Physiological Basis of Cardiovascular Cell and Gene Therapies. Other articles appearing in this collection, as well as a full archive of all collections, can be found online at http://ajpheart.physiology.org/.

Introduction

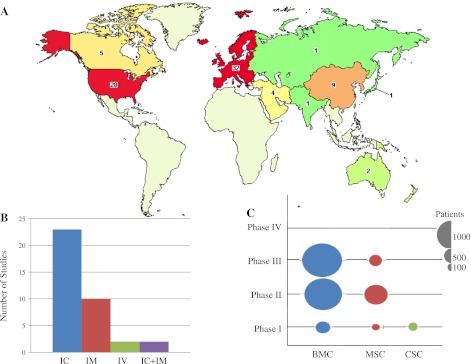

A recent update from the American Heart Association (140) reported that in 2008, 2.7% of Americans suffered a myocardial infarction (MI), ∼8 million survived an MI, and an estimated 82.6 million were living with one or more types of cardiovascular disease, costing a staggering $300 billion that year. These statistics underscore the challenges facing our health care system today. While advances in both pharmacological and interventional approaches for revascularization have significantly reduced the morbidity and mortality of ischemic heart disease over the past half-century, they do not directly reverse the major reason for ventricular failure and electrical system disturbance, the progressive ventricular remodeling that follows an MI. Therefore, the need for novel therapeutic modalities is paramount. In this regard, encouraging results from preclinical studies and phase I–III clinical trials (Fig. 1) suggest that stem cell therapy provides anti-remodeling effects leading to the restoration of contractile function in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy.

Fig. 1.

Ongoing clinical trial activity evaluating cell-based therapy for heart disease. A: topographic representation of ongoing clinical trials currently registered with ClinicalTrials.gov employing stem cell therapy for myocardial infarction (map adapted from ClinicalTrials.gov). B: types of delivery systems. IC, intracoronary infusion; IM, intramyocardial injection; IV, intravenous infusion. C: number of patients enrolled in clinical trials of different phases. BMC, bone marrow-derived stem cells; MSC, mesenchymal stem cells; CSC, cardiac stem cells.

With the discovery of cardiac stem cells (CSCs), the notion that adult myocardial tissue has endogenous regenerative capability (12) signaled the beginning of a new era in cardiovascular medicine. A stem cell is defined by its ability to self-renew and to differentiate into one or more lineages of specialized cell types (151). In addition, stem cells are generally organized in niches where their interaction with other cell types (including other stem cells) and the stroma maintains their “stemness” (61, 110, 173). Characteristics of an ideal stem cell for use in cardiac cell-based therapy are availability, tissue residence or homing specifically to the injured tissue, ability to mobilize endogenous repair mechanisms that are otherwise overwhelmed by the magnitude of damage, and providing a sustainable benefit that translates as prevention or reversal of pathological remodeling and as improvement of left ventricular (LV) function. Previous and ongoing preclinical studies and clinical trials suggest that there are many stem cells that could play this role. Determining the most effective stem cell(s) and also understanding the mechanisms by which they exert their therapeutic effects are the focus of current studies (96, 104). Each stem cell type, in theory, exhibits some of the characteristics that contribute to a capacity to exert a therapeutic response. As is typical in the evolution of new therapeutic strategies, the ultimate proof derives from clinical testing, and in this regard, some cell therapeutic strategies have not produced the hypothesized improvements in clinical endpoints (161). Nevertheless, in this early stage of stem cell therapy, both the successes and the failures are informative. This article will review the different types of stem cells and recent advances and molecular mechanisms underlying cell-based therapeutic modalities for preventing or reversing myocardial remodeling.

Pluripotent Stem Cells

Pluripotent stem cells, such as embryonic stem cells (ESCs) that can differentiate into all adult cell types, have fundamental characteristics that could produce cardiac regeneration, namely, the ability to differentiate into cells that resemble spontaneously beating cardiac myocytes and express characteristic cardiac myocyte transcription factors (45) as well as into cells that participate in neovascularization (106). When transplanted into infarcted rodent myocardium, ESC-derived cardiac myocytes engraft and improve cardiac function (111, 113). However, their immune-privileged properties have been questioned (189), and ethical, legal, and biological (15, 41) issues have hampered the use of ESCs in human trials. The ability to circumvent these problems by reprogramming adult somatic cells into ESC-like, induced pluripotent stem cells (177) or induced cardiomyocytes (64) potentially provides an attractive alternative to ESCs. These cells have only recently been investigated in clinical trials (71, 119), but the reproducibility, durability, and safety of human cell reprogramming and genetic engineering strategies remains the subject of intense laboratory investigation.

Umbilical Cord Blood Stem Cells

Umbilical cord blood contains a wide variety of stem cells, including hematopoietic stem cells (176), mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) (23), and a population of unrestricted somatic stem cells (83), that can be differentiated both in vitro and in vivo into numerous cell types, including cardiomyocytes (83). Although umbilical cord blood stem cells have generated conflicting results in preclinical studies (75, 83, 101, 114), there are studies (27) showing that Wharton's jelly-derived MSCs have a greater endothelial differentiation capacity than bone marrow-derived MSCs, and they are currently the subject of the phase-II clinical trial, Intracoronary Human Wharton's Jelly-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells (WJ-MSCs) Transfer in Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction (WJ-MSC-AMI; NCT01291329).

Skeletal Myoblasts

Skeletal myoblasts (satellite cells) are a population of quiescent stem cells located under the basal lamina of muscle fibers that proliferate in response to injury to help regenerate muscular tissue (19). Although they have limited differentiation ability, skeletal myoblasts, based on the concept that these cells would have sufficient plasticity for cardiac myocyte differentiation, have been investigated as a potential therapeutic approach for myocardial regeneration (1, 53, 162). Studies indicate that skeletal myoblasts are unable to couple electromechanically with the endogenous cardiomyocytes, and this deficit is likely the basis of the detrimental ventricular tachyarrhythmias observed in early studies (154, 156). Thus, despite more than 40 preclinical studies, questions regarding the safety and efficacy of these cells remain (154, 156), and there is relatively less enthusiasm for this cell type compared with other alternatives.

Bone Marrow-Derived Stem Cells

There is intense interest in the bone marrow as a source of cells with capacity for cardiac repair, and bone marrow has been widely tested in mechanistic studies and clinical trials for cardiac disease. Bone marrow harbors a wide variety of stem/precursor cells with potential for cardiac differentiation. Some, but not all, studies support the idea that bone marrow-derived stem/progenitor cells (BMSCs) (20) have the capacity to differentiate into cardiac myocytes and endothelial cells (123, 124). These characteristics and the relative accessibility of bone marrow have supported the hypothesis that autologous BMSCs and/or its stem/progenitor cell populations could produce phenotypic and clinical recovery in patients with remodeled ventricles. Preclinical studies have demonstrated that whole bone marrow (8, 65, 70, 118, 123) improves hemodynamic parameters and cardiac morphology. Kamihata et al. (70) showed that whole bone marrow improved myocardial perfusion and reduced infarct size in a swine model. In addition, the newly formed capillaries, but not the fibroblasts, in the infarct area were derived from donor BMSCs, supporting the notion that BMSC therapy produces a proangiogenic rather than a fibrosis-inducing microenvironment.

Endothelial progenitor cells and mononuclear cells.

In addition to whole bone marrow, numerous studies have been conducted examining specific constituents of bone marrow. Endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) share certain phenotypic and functional characteristics with fetal angioblasts (80) and express the surface markers CD34, CD133 (5), Flk-1 [vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptor-2] (128), and AC133 (hematopoietic stem cell marker not expressed on mature endothelial cells) (51). In preclinical studies, EPCs promote neovascularization, leading to the prevention of LV remodeling and to some degree of cardiomyocyte regeneration (147). Although several phase-1 clinical trials have reported preliminary feasibility and safety data with EPC therapy after MI, most of these studies actually investigated bone marrow-derived mononuclear cells (MNCs), not isolated EPCs (150). In the Transplantation of Progenitor Cells and Regeneration Enhancement in Acute Myocardial Infarction (TOPCARE-AMI) trial (91), patients with acute MI received an intracoronary infusion of ex vivo expanded bone marrow MNCs or culture-enriched EPCs derived from peripheral blood MNCs. With this strategy, there was sustained improvement in LV function, reduction in end-systolic volume, and prevention of remodeling one year later in both the bone marrow MNCs and culture-enriched circulating EPC treatment groups. Given the promising findings of the TOPCARE-AMI trial, additional clinical investigations are underway. Notably, the Enhanced Angiogenic Cell Therapy-Acute Myocardial Infarction Trial (ENACT-AMI) is a phase-II clinical trial that will investigate the efficacy and safety of autologous EPCs and autologous EPCs transfected with human endothelial nitric oxide synthase (NCT00936819).

While there is substantial evidence for the safety of bone marrow MNCs from clinical trials, there are inconsistent findings as to their efficacy. The TOPCARE-AMI (91) and the BOne marrOw transfer to enhance ST-elevation infarct regeneration (BOOST) trials (144) recently completed their 5-year follow-up. These trials, which together totaled 119 patients, illustrated the long-term safety of this cell-based therapy approach. In TOPCARE-AMI, the improvement in LV ejection fraction (LVEF) in the treated group was sustained, but results from BOOST showed that the early (6 mo) improvement in LVEF in the treated group was not sustained at 5 years. These inconsistent findings emphasize the importance of examining in future trials the long-term sustainability of cell-based therapy.

Furthermore, the First Mononuclear Cells injected in the United States conducted by the Cardiovascular Cell Therapy Research Network (FOCUS-CCTRN) phase-2 trial evaluated whether transendocardial delivery of bone marrow MNCs improves LV performance and perfusion at 6 mo in patients with chronic ischemic cardiomyopathy (130). Although there was no improvement compared with placebo in LV end-systolic volume, maximal oxygen consumption, or myocardial perfusion, exploratory analyses showed significant improvement in LVEF and stroke volume. Interestingly, the improvement in ejection fraction was associated with higher bone marrow CD34+ and CD133+ progenitor cell counts. These results suggest that the cellular composition of the bone marrow may determine clinical end points, with certain cell populations providing a greater regenerative benefit.

MSCs for ischemic heart disease.

MSCs comprise ∼0.01% of bone marrow and are operationally defined as plastic-adherent, hematopoietic lineage negative cells of the MNC fraction of the bone marrow (133). MSCs have also been isolated from virtually every tissue type (33) and are thought to participate in niches, regulating the function of hematopoietic cells (26) and other specific lineages (40). Interestingly, MSCs also differentiate into bone, tendon, cartilage, fat, and muscle, raising the possibility of their use in disorders of organ systems comprising those tissues (26). While these cells express numerous cell surface markers, including CD105, CD73, and CD90 (190), no single cell surface marker indisputably characterizes MSCs. Furthermore, MSCs may lose the expression of certain surface markers or even acquire the expression of new ones as they are isolated and expanded in vitro (67). Therefore, MSCs are not a homogenous population of cells (120) and whether MSCs from different tissues are biologically equivalent remains to be determined (191).

Multilineage differentiation potential has become one of the defining characteristics of MSCs (7). Under specific culture conditions in vitro, these cells can differentiate into osteocytes, chondrocytes, adipocytes, smooth muscle cells, fibroblasts, endothelial cells, (132) and cardiomyocyte-like cells (102). Caplan (21) showed that differentiation depends on the cellular milieu. For example, bone marrow-derived MSCs (BM-MSCs) cultured in the presence of 5-azacytidine differentiate into multinucleated myotubes that express β-myosin heavy chain, desmin, and α-cardiac actin and also display spontaneous rhythmic calcium fluxes (180). Murine BM-MSCs cultured under the same conditions started beating spontaneously, connected to adjoining cells, and became synchronized after 2 to 3 wk (102). Those cells adopted two types of action potentials, sinus node-like and ventricular myocyte-like, and exhibited cardiomyocyte-specific gene expression (atrial natriuretic peptide, α- and β-myosin heavy chain, Nkx2–5, and GATA4) (102). Rat BM-MSCs cocultured with neonatal rat ventricular myocytes differentiated into cardiomyocytes that contracted, expressed sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum calcium-ATPase 2 and ryanodine receptor 2 and were positive for troponin T, α-actinin, and desmin (98). Another factor that may promote cardiomyocyte differentiation is mechanical loading (131). Several studies have revealed two main regulatory pathways of MSCs differentiation, the Wnt (17, 37, 44) and the transforming growth factor (TGF)-β pathways (4, 7), but there is a plethora of other molecules that have been shown to play a regulatory role, such as epidermal growth factor, platelet-derived growth factor, and fibroblast growth factor (108, 165).

Animal studies have established that MSCs are capable of differentiating into cardiomyocytes and/or vascular structures in both allogeneic (61, 145) and xenotransplantation (166) models, resulting in significant functional improvement and reduction of ischemic scar area. Interestingly, animals subjected to allogeneic MSC transplantation did not manifest evidence of rejection (3, 141), consistent with observations by several groups that MSCs exhibit immune-privileged properties in vitro and in vivo (56), likely because of the absence of MHC-II, B-7 costimulatory molecules, and CD40 ligand (170). The lack of costimulatory molecules prevents T-cell responses and also induces an immunosuppressive local microenvironment through the production of prostaglandins and other soluble mediators such as nitric oxide, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase, and heme oxygenase-1 (24, 79, 84, 138, 143). MSCs reduce the respiratory burst that follows neutrophilic responses by releasing interleukin-6 (136). They also inhibit the differentiation of immature monocytes into dendritic cells, hence the antigen presentation to naïve T cells is greatly impaired (66). In addition, MSCs release soluble factors, such as hepatocyte growth factor and TGF-β1 (39) that suppress the proliferation of cytotoxic and helper T cells.

The potential clinical application of MSCs was explored early in the developing field of cell-based therapy. Chen et al. randomized 69 patients post-MI to receive intracoronary administration of either autologous MSCs or placebo. They used single positron emission computer tomography and detected a significant improvement in LV function and perfusion defect, suggesting that MSC therapy induces regeneration of infarcted myocardium and protects against LV remodeling (28). We compared the therapeutic benefit of intravenous administration of allogeneic MSCs to placebo in 60 patients after acute MI (60). In addition to establishing the safety of allogeneic MSC delivery to humans, echocardiography revealed a 6% increase in LVEF at 3 mo for MSC-treated patients. In addition, patients receiving MSCs had improved quality of life, better respiratory function, and a near eradication of ventricular arrhythmias. Recently, Williams et al. (179) reported the results from the first eight patients of the Transendocardial Autologous Cells in Ischemic Heart Failure Trial (TAC-HFT), in which autologous BMSCs (either culture expanded MSCs or MNCs) were injected intramyocardially into patients with chronic ischemic cardiomyopathy. These patients demonstrated improved regional myocardial contractility and decreased infarct size. Notably, early improvements in regional function predicted the degree of reverse remodeling 12 mo following cell therapy. These early investigations have engendered a plethora of ongoing trials testing the capacity of MSCs or MSC precursors for myocardial regeneration. Importantly, the findings from these studies have also indicated that the selection of end points, such as direct measures of infarct size and ventricular remodeling, that accurately reflect clinical outcomes could represent more suitable measures of efficacy for cell therapy (161, 179) than LVEF, which most cell therapy trials have used as the primary end-point marker of efficacy.

As previously mentioned, MSCs have the capacity to be used as an allogeneic cell therapeutic. To test whether allogeneic MSCs are as safe and effective as autologous MSCs, our group is conducting The Percutaneous Stem Cell Injection Delivery Effects on Neomyogenesis Pilot Study (The POSEIDON-Pilot Study; NCT01087996), the first direct randomized head-to-head comparison of autologous versus allogeneic MSCs delivered by transendocardial, intramyocardial injection. This study will help determine whether or not allogeneic MSCs, a cost-effective “off the shelf” cell product, are equally effective as a therapeutic regimen as autologous MSCs and will also define the relative advantages of the autologous versus allogeneic approach in various patient populations.

MSCs for nonischemic heart disease.

Although the majority of cardiac cell-based therapy studies have targeted acute MI and ischemic cardiomyopathy, it is important to point out that a significant number of heart failure patients have nonischemic cardiomyopathy. Idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) is a leading cause of heart failure morbidity and mortality and accounts for ∼50% of heart transplants (163). The primary phenotype of DCM is an enlarged, remodeled ventricle with increased end-diastolic and end-systolic volumes, reduced ejection fraction, and impaired contractile and diastolic function. Given that cell-based therapy produces durable and sustainable improvements in cardiac function and causes reverse remodeling in ischemic cardiomyopathy, it is attractive to hypothesize the same for patients with nonischemic cardiomyopathies. If these effects can be clinically established and optimized, there is enormous potential for improving clinical outcomes for the many patients suffering from DCM. A case report and small clinical study on the safety and feasibility of cell therapy for DCM (86, 109) were encouraging and indicate that larger scale randomized trials are warranted. Accordingly, we have initiated a clinical trial to establish the safety and efficacy of bone marrow-derived MSC therapy for patients with DCM. The Percutaneous Stem Cell Injection Delivery Effects on Neomyogenesis-Dilated Cardiomyopathy (POSEIDON-DCM; NCT01392625) study is a randomized comparison of autologous versus allogeneic MSC therapy employing percutaneous delivery with a transendocardial catheter delivery system.

Cardiac Stem Cells

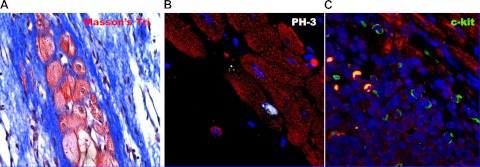

The realization that adult myocardial tissue(s) have endogenous regenerative capability (12) dramatically shifted the long-held view that the heart is a terminally differentiated organ without regenerative capability. It has now become evident that there are myocytes in the heart expressing the cell cycle proteins CDC6, Ki67, MCM5, serine 10-phosphorylated histone H3 (PH3; Fig. 2B), and aurora B kinase, indicating that these cells can replicate (11). The rate of replication of these myocytes increases substantially in pathological states (93). Two possibilities could account for the presence of these cells: replicating CSCs (Fig. 2C) evolving into transient amplifying cells or mature myocytes that have dedifferentiated and reentered the cell cycle (14, 43, 85). A landmark study by Beltrami et al. (12) was the first to challenge the dogma that the adult myocardium lacks regenerative capacity. The authors reported a population of cardiac Lin− c-kit+ cells possessing the properties of CSCs. These cells gave rise to cardiomyocytes, smooth muscle cells, and endothelial cells; indicating their ability to undergo trilineage differentiation, reconstitute myocardium, and form new blood vessels and cardiomyocytes when injected into an ischemic heart. Accordingly, this study established that the adult mammalian heart does indeed contain a compartment of stem cells.

Fig. 2.

Mechanisms of cardiac regeneration. Mammalian myocyte renewal may result from stem cell differentiation and/or myocyte mitosis. These processes are likely linked in that CSCs become mature myocytes by becoming transient amplifying cells, a process enhanced by MSCs. A: Masson's trichrome (Masson's Tri) histological stain obtained from the border zone between infarcted and viable myocardium in the porcine heart. In this image viable new myocytes are shown in red and scarred myocardium in blue. Immunohistochemical analysis for the mitotic marker serine 10 phosphorylated histone H3 (PH3; white nucleus) in B and c-kit (green) in C suggests regeneration of new myocardium from replicating myocytes and adult c-kit+ CSCs, respectively. The relative contribution of CSCs or adult dedifferentiation to myocyte entry into the cell cycle is not definitively defined. The spatial and temporal colocalization of c-kit cells and the PH3 myocytes in an animal treated with MSCs is suggestive that the mitotic cells represent transient amplifying cells (61, 94).

CSCs are a diverse cell population. They are approximately one-tenth the size of mature cardiac myocytes and express the stem cell factor receptor c-kit (CD117) (12), stem cell antigen 1 (Sca-1; an antigen present in rodents but not mammals) (122), and in some cases the transcription factor Islet-1 (89), which in neonatal hearts marks the second heart field. Islet-1 is also reported in cardiosphere-derived cells (discussed below) derived from postnatal hearts (112). Hierlihy et al. (62) identified a side population of cells that form colonies in vitro (semisolid media) and differentiate into cardiomyocytes. Interestingly, these cells were found to be activated when growth of the postnatal murine heart was attenuated, through overexpression of a dominant negative cardiac transcription factor (MEF2C), and subsequently depleted. These findings were suggestive of a responsive CSC pool in the adult myocardium. Additionally, Martin et al. (107) detected another side population of cells that are capable of proliferating and differentiating into cardiac and hematopoietic lineages in vitro. These cells were identified based on their expression of Abcg2, an ATP-binding cassette transporter.

Another source of CSCs may emerge from studying the integral role of the epicardium in heart development (158), which in lower vertebrates (68, 74) participates in cardiac regeneration. Although several groups have studied the presence of c-kit+ cells in the epicardium with variable results (100, 184), there is now mounting evidence for the presence of epicardial progenitor cells that resemble MSCs (29). Following MI, these cells undergo endothelial-to-mesenchymal cell transformation (22). The acquisition of a mesenchymal phenotype and subsequent migration from the subepicardial space into the myocardial wall is followed by proliferation and formation of myocardial precursors and vascular cells (22, 38, 100). Furthermore, MI triggers the activation of fetal epicardial genes (Tbx18, WT1, and retinaldehyde dehydrogenase type 2) (99). Limana et al. (99) demonstrated in infarcted murine hearts that epicardial progenitor cells coexpress c-kit and WT1 and/or Tbx18, suggesting that these cell populations are epicardial cardiogenic precursors.

The identification of progenitor cells in the epicardium with ESC characteristics suggests that signaling factors that modulate embryonic epicardial cell functions may also contribute to the activation of adult epicardial progenitors. Several growth factors that contribute to coronary vessel formation [erythropoietin, VEGF, fibroblast growth factor (FGF), thymosin β4] have been administered in animal models of MI and heart failure resulting in enhanced vascularization (2, 90, 139, 171). Smart et al. (155) studied cardiac-specific thymosin β4 knockdown mice and demonstrated that the loss of thymosin β4 may result in impaired paracrine signaling to the epicardium, leading to impaired coronary vascular formation. Furthermore, it has been shown that systemic administration of thymosin β4 in mice after MI results in decreased cardiomyocyte death (159) and reactivation of the embryonic program, as demonstrated by the epicardial increased expression of VEGF, Flk-1, FGF17, FGF receptor-2, FGF receptor-4, TGF-β and β-catenin (16).

CSCs are likely supported and maintained within cardiac tissue in specialized microenvironments termed “stem cell niches” (48, 115). Niches are located in the myocardial interstitium where CSCs can maintain their “stemness” by forming connections with other stem and supporting cells, i.e., mature cardiomyocytes and fibroblasts, through connexins and cadherins. Niches have been detected throughout the myocardium and are concentrated at the atria and apex (172), and it is from within these niches that endogenous stem cells proliferate and then migrate to the injury site after an ischemic incident (122). CSCs and side population cells most likely mediate endogenous mechanisms for minor repair and for replacement of ongoing cell turnover within the adult heart. The endogenous repair appears to be limited to noninfarcted tissue (13) and may attenuate the progression to heart failure. However, significant cellular injury, as inflicted by an MI, could overwhelm the regenerative ability and contribute to stem cell and niche depletion or destruction (94).

It has been proposed that cardiospheres mimic cardiac niches (95). Cardiospheres contain a central cluster of c-kit+ cells, layers of differentiating cells expressing myocyte proteins and the gap junction protein, connexin 43, and an external layer of mesenchymal cells. When transplanted into murine-injured hearts, cardiospheres exhibit enhanced engraftment and improved myocardial function compared with cells grown in a monolayer. This difference may in part be due to the presence of connexin-43 gap junctions. Connexin 43 plays a differentiation-dependent role. In more differentiated cardiomyocytes, connexin 43 promotes cell-cell electrical coupling (72), whereas in less mature cells it promotes proliferation and differentiation (55, 125). Dissociation of cardiospheres into single cells decreased the expression of adhesion molecules and undermined resistance to oxidative stress, thereby reducing their ability to engraft and their functional benefit (95). On the other hand, Ye at al. (182) isolated and cloned Sca-1+CD45− cardiosphere-derived cells and injected them into post-MI mice hearts. They observed that cloned Sca1+CD45− cells induced angiogenesis, differentiated into endothelial and smooth muscle cells, and improved cardiac function. Interestingly, the expression of the transcription factor Islet-1 was threefold higher in the Sca1+CD45− cells than in whole cardiospheres. Islet-1 is expressed in a cell population that gives rise to both myocardial and vascular tissues (89). These studies suggest that cardiospheres provide a niche-like environment that helps resist oxidative stress and maintain “stemness,” whereas isolation of cells from cardiospheres promotes their differentiation and lineage commitment. Further studies are needed to elucidate the mechanisms involved in the balance between resistance to oxidative stress and relevant lineage commitment.

Clinical trials employing CSCs.

CSCs can be harvested from patient cardiac biopsies and expanded ex vivo to generate large numbers of autologous cells (10), which can then be delivered back to the patient. Recently published results from the phase-I clinical trial Cardiac Stem Cell Infusion in Patients With Ischemic CardiOmyopathy (SCIPIO) (18) demonstrated that intracoronary infusion of autologous c-kit+ CSCs is effective at improving LV systolic function and reducing infarct size in patients with heart failure after MI. These results are very encouraging and provide rationale for larger randomized trials that will extend these observations to test whether clinical benefits derive in patients receiving infusions of these cells.

A phase-I randomized clinical trial of cardiospheres as a cell-based therapeutic was also recently completed. The CArdiosphere-Derived aUtologous stem CElls to reverse ventricUlar dySfunction (CADUCEUS) trial (103) included 25 patients who had suffered an MI and who were randomized to receive cardiosphere-derived cells (by intracoronary infusion) or standard care. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) analyses 6 mo after treatment with cardiospheres showed a reduction in scar mass and an increase in viable heart mass, regional contractility, and regional systolic wall thickening. In contrast to the study of culture-expanded c-kit+ CSCs, cardiospheres did not augment parameters of integrated cardiac performance such as LVEF.

Mechanisms of Action of Cell-Based Therapy

The initial motivation for stem cell research and cell-based therapy was the idea that the injection of stem cells into a scarred myocardium would promote regeneration through transdifferentiation of the exogenously delivered stem cells, a hypothesis supported by Orlic et al. (123). However, the totality of ongoing mechanistic and translational studies has highlighted the fact that the therapeutic process is a multifaceted, orchestrated process involving multiple mechanisms of action.

The in vivo mechanism of action of MSCs is under intense investigation in an effort to shed light on the multifaceted nature of cell-based stimulation of cardiac repair (3, 135, 166, 181). MSCs engraft and differentiate when transplanted in the heart (61, 135). In this regard, Toma et al. (166) used immunofluorescence staining with anti-β-galactosidase to identify engrafted MSCs (labeled with lacZ) intramyocardially delivered to murine hearts. Engrafted MSCs expressed markers of myocardial differentiation as early as 14 days postinjection. Building on these early results, many studies followed in rodent (149) as well as swine models (3, 61, 145, 185). The study by Quevedo et al. (135), using a swine model of ischemic cardiomyopathy, showed that 14% of engrafted MSCs demonstrated evidence of cardiomyocyte differentiation. In addition, there was evidence of cell-to-cell coupling between these differentiated MSCs and host myocytes via connexin-43 gap junctions. In a swine model of acute MI, a combination of a statin and intramyocardial injections of BM-MSCs improved cardiomyocyte-differentiation capability by fourfold (181). However, not all studies show in vivo differentiation of MSCs. For example, MSC differentiation was not evident in a canine model by Silva and colleagues (152), revealing potential differences between species and/or study designs.

Despite the evidence for differentiation of engrafted MSCs (69, 105, 135), the collective results from studies of MSCs have called into question the correlation between the frequency of engraftment and differentiation of transplanted MSCs and the reported functional recovery early posttransplantation. For instance, reports of LV functional improvement within 72 h postinjection cannot be explained by MSC transdifferentiation (117). Based on these observations, some investigators questioned whether differentiation occurs at all, raising the theory that cell fusion with resident myocytes could explain, at least in part, cardiac recovery (121). On the other hand, the fact that of hundreds of millions of cells fewer than 10% remain after 2 wk has lent credence to the paracrine signaling hypothesis (54), whereby exogenous MSCs secrete factors that induce neovascularization and prevent cardiomyocyte apoptosis, thereby reducing remodeling and improving cardiac function (80, 147). However, the observation of long-term MSC survival, engraftment, and trilineage differentiation and that MSC engraftment correlated with functional recovery in contractility and myocardial blood flow in a swine model of chronic ischemic cardiomyopathy (105) indicate that stem cells do provide more than simply paracrine support for repair. Moreover, other investigators have suggested that it may simply be the sheer mechanical strengthening of the MI scar that prevents further deterioration in cardiac function (121). It is likely that the combination of short- and long-term effects of MSCs maintains the process of reverse remodeling.

With regard to the paracrine signaling hypothesis, various studies indicate that MSCs secrete proangiogenic, antifibrotic, and antiapoptotic factors, such as VEGF, stromal-derived factor-1 (77), angiopoietin 1 (73), insulin-like growth factor 1 (57), hepatocyte growth factor, periostin (76), and thymosin b4 (63). Amado et al. (3) reported that MSCs express VEGF, which is linked to both neoangiogenesis and stem cell homing and migration, but also provided strong evidence of cell differentiation.

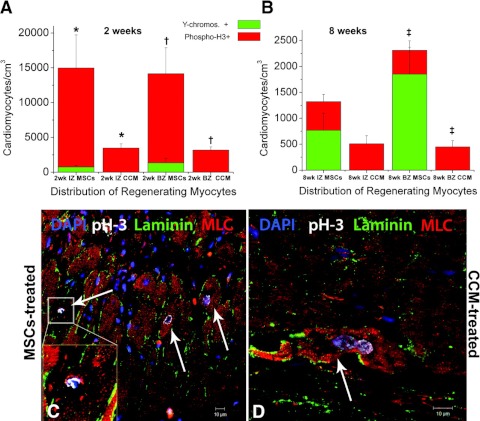

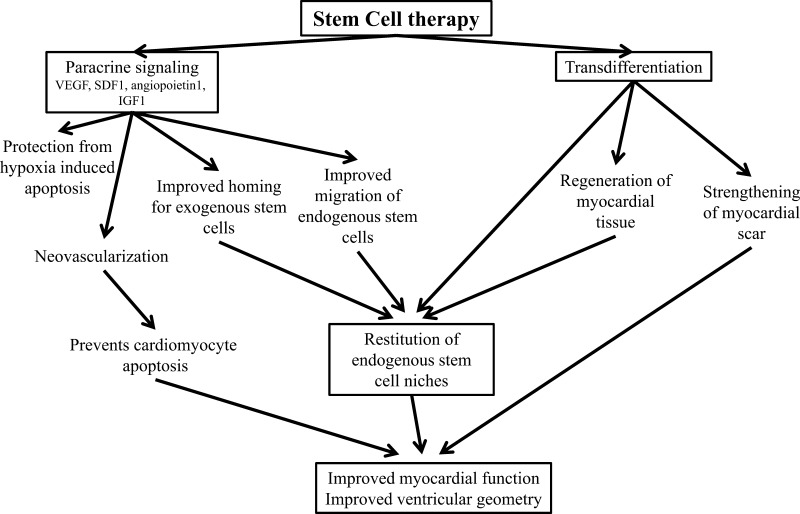

Perhaps the most important insight into the mechanism of action derives from studies of cell-cell interactions. In a study comparing MSC conditioned medium versus MSCs themselves, Hatzistergos et al. (61) demonstrated in a swine model of MI that intramyocardial injection of MSCs reduced infarct size by recruiting endogenous c-kit+ CSCs, whereas an injection of concentrated MSC-conditioned media had no effect. In this study, histological examination revealed chimeric clusters comprised of adult cardiomyocytes, transplanted MSCs, and host c-kit+ CSCs that expressed connexin-43-mediated gap junctions and N-cadherin mechanical connections between cells. Importantly, MSC treatment enhanced substantially the abundance of host c-kit+ CSCs and their cardiomyocyte lineage commitment capacity. In addition, MSCs and CSCs appeared to create cell clusters closely resembling stem cell niches (Fig. 3). The latter underscores the emerging concept that MSCs may act both as progenitors for certain cell lineages and, through their participation in niches, as supporting/regulatory cells for other lineages (94). All of the aforementioned mechanistic insights (Fig. 4) allow us to generate a novel hypothesis that cell therapy reconstitutes endogenous stem cell niches—by way of transdifferentiation and paracrine signaling—and in that manner facilitate cardiac self-healing.

Fig. 3.

MSCs stimulate endogenous cardiomyocyte cell (CM) cycling. A and B: quantification of newly formed myocytes of both host (red bar graph, phospho-H3+) and donor (green bar graph, Y chromosome+) origin 2- and 8-wk postinjection, respectively. MSCs stimulated host cardiomyocytes to amplify during the first 2 wk following transendocardial injection. The new CMs were mainly distributed at the ischemic zone (IZ) and border zone (BZ) of the treated hearts, indicating active regeneration of injured myocardium. By 8 wk, endogenous cycling CMs levels had returned to normal values. C and D: mitotic features in endogenous CMs from the BZ of an MSC-treated and cell-conditioned media (CCM)-treated heart, respectively. MLC, myosin light chain; DAPI, 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. Values are means ± SE (n = 3 hearts, each). *P < 0.05, †P ≤ 0.005 between groups; ‡P = 0.05 between groups. Reproduced with permission from Hatzistergos et al., Circulation Research, 2010 (61).

Fig. 4.

Mechanisms underlying cardiac regeneration due to cell-based therapy. The improvement in myocardial function and ventricular geometry after transplantation of stem results from multiple coordinated actions of cells used as a therapeutic. Successful cell-base therapy, as observed as a result of MSC and CSC therapy, likely arises from the actions of both administered cells and host cellular elements. Notably, MSCs both have the capacity for trilineage differentiation, as well as stimulating the recruitment, survival, and differentiation of host CSCs. This action of MSCs results from both secretion of cytokines and growth factors [vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), stromal-derived factor 1 (SDF1), insulin-growth factor 1 (IGF1), angiopoietin 1] and antifibrotic mediators that together promote neovascularization and reduce fibrosis. Together these actions and the recruitment of endogenous CSCs could represent the reconstitution of stem cell niches in the myocardium.

Timing of Delivery

It is recognized that practical issues such as timing, delivery method, and dosing could contribute substantially to the outcome of clinical investigation. In the setting of acute MI, cell therapy seems to have a specific time frame of therapeutic opportunity, a period after MI when the myocardium is more “ripe” for cell therapy (6, 42). In this regard, two clinical trials are investigating the optimal timing of cell delivery of bone marrow MNCs with the intent of resolving the questions regarding their therapeutic potential. The Transplantation in Myocardial Infarction Evaluation (TIME) study is a phase-II trial developed by the CCTRN to test the efficacy, safety, and most appropriate timing of bone marrow MNCs in patients after acute MI (169). This trial is comparing the effects of intracoronary delivery of MNCs at 3 and 7 days post-MI in patients with ST-segment elevation, whereas the recently published LateTIME trial tested whether delaying MNC delivery for 2 to 3 wk following MI, and primary percutaneous coronary intervention improves global and regional LV function (59, 168). In LateTIME, there were no significant changes between baseline and 6-mo measures in the MNC group compared with placebo in LVEF, wall motion in the infarct zone, and wall motion in the border zone, as measured by cardiac MRI. These results suggest that the timing of cell therapy at 2 to 3 wk post-MI may exceed the therapeutic window.

Insights on the most appropriate timing can be gleaned from preclinical studies. For instance, Zang et al. (188) attempted to determine the timing and frequency of cell injections necessary for optimal therapeutic efficacy. They examined the relationship between frequency of injection and therapeutic potential by injecting bone marrow cells into murine ischemic hearts at days 3, 7, or 14 post-MI (monotherapy), at days 3 and 7 (dual therapy), and at days 3, 7, and 14 (triple therapy). Injection solely at day 3 reduced infarct size and improved LV function. However, multiple injections of bone marrow cells had no additive effect, and delaying cell therapy post-MI resulted in no functional benefit. Moreover, a study by Urbanek et al. (172) showed that endogenous CSCs proliferate immediately after MI, but in the chronic phase, their numbers fall and the remaining CSCs have less regenerative potential. This notion is challenged by the preliminary results of the TAC-HFT clinical trial (179) where functional improvement was achieved even at a very late stage post-MI, when heart failure was well established.

Delivery Methods

While there is general agreement that stem cells are a promising therapeutic regimen post-MI, determining the most appropriate stem cell delivery method is still a matter of vigorous debate. To date many techniques have been described, including intravenous (9), transarterial (175), intracoronary (160), intramyocardial—either transepicardial (129) or catheter-based transendocardial (153)—and transvenous injection into coronary veins (164). The least invasive, transvenous, has the disadvantage that cells may be trapped in the pulmonary circulation (9) before they even reach the systemic circulation. Thus far, the most frequently used technique in clinical trials is the percutaneous coronary delivery of cells. The cells are injected via an over-the-wire balloon catheter into the vessel supplying the ischemic territory. This technique requires a transient ischemic period through the inflation of the balloon to give the cells the chance to be distributed and not washed out, although Tossios et al. (167) proposed that the occlusion is unnecessary.

Intramyocardial delivery of cells is a technique that has gained momentum in the clinical setting (Fig. 1) (3, 179). The advantage of this method lies in the fact that unlike the intracoronary approach, which requires transmigration of the endothelial barrier, cells that undergo intramyocardial injection are largely found in the interstitial space. Conversely, the main disadvantage is that larger scarred areas require multiple injections. The addition of electromechanical mapping will render this approach the most accurate on tracking the ischemic areas (156). Determining the most suitable method and the most appropriate route of cell delivery will likely depend on the clinical setting and the cell type and no consensus has been reached.

The common issues surrounding every cardiac delivery method employed to date are the reduction of inflammation, stimulation of neovascularization, and improvement in cell engraftment, proliferation, and survival rates (174). To address these issues, new experimental strategies are emerging using cardiac tissue engineering. The general strategy involves a combination of cells and biomaterials (hydrogel or three-dimensional scaffolds) (148). This approach promotes greater cell retention (higher viscosity than saline-based suspension) and survival (antiapoptotic biomaterials) (31, 137). A variety of biomaterials have been investigated, including fibrin (142, 186), collagen (34), Matrigel (82), self-assembling peptides (35), chitosan (183), and alginate (92) in combination with skeletal myoblasts (30), endothelial cells (36), bone marrow MNCs (186), MSCs (187), ESCs (81), and neonatal cardiomyocytes (36). Although there are obvious advantages to this strategy, there are also some disadvantages. The biomaterials lack flexibility and thus cannot successfully mimic the myocardial mechanical microenvironment (50). In addition, they degrade relatively quickly, and, more importantly, the engrafted cells create isolated “islands” with no direct cell-cell interaction with the surrounding tissue (49).

Optimal Dosage of Cell Therapy

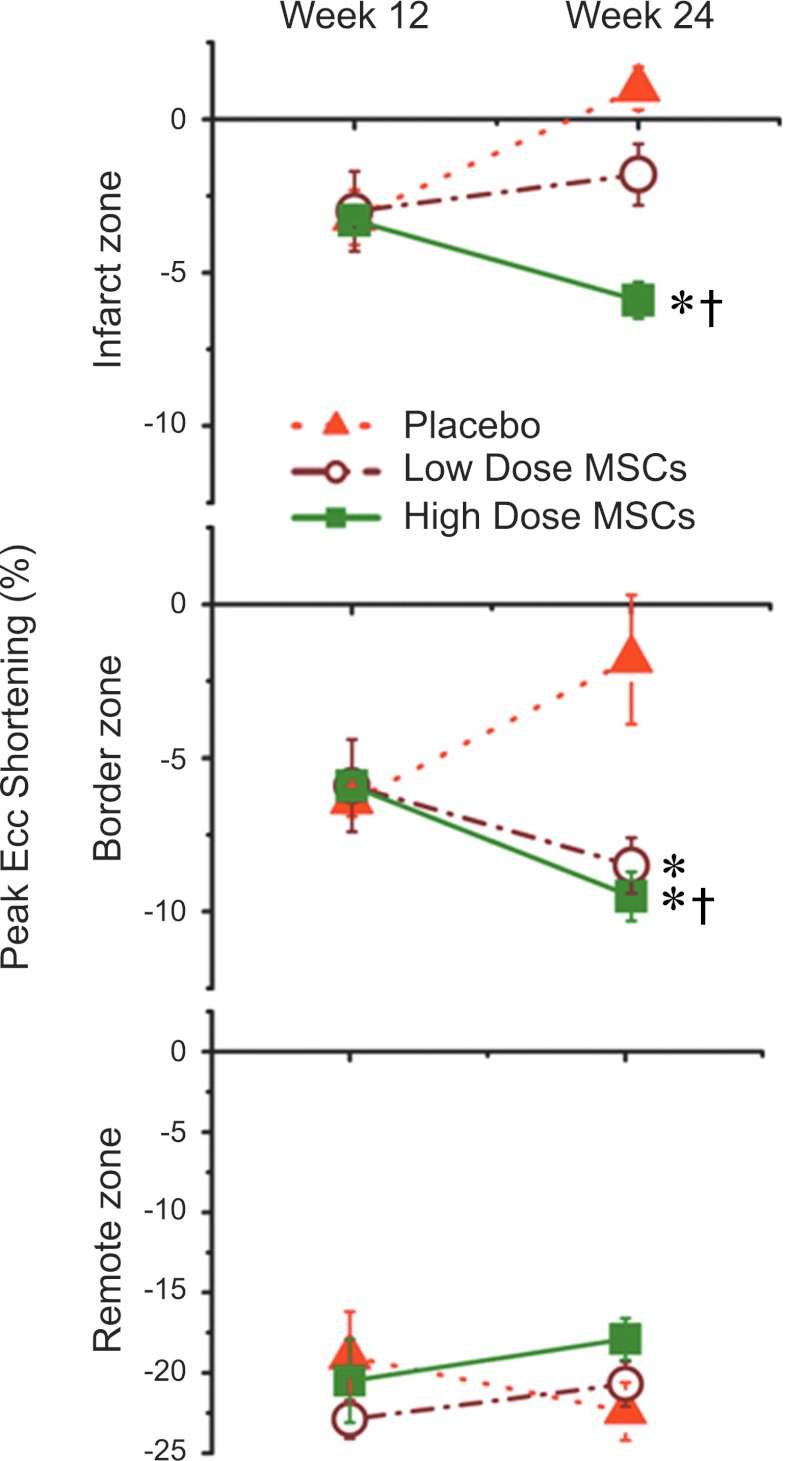

Another issue defining an effective therapy is the appropriate quantity of cells transplanted. Instinctively, in stem cell therapy it may be assumed that the more cells transplanted the larger their beneficial impact would be. Two studies that addressed cell dosage reported interesting results that introduce the notion of the threshold effect. Hamamoto and colleagues (58) injected sheep with one of four different dosages (25, 75, 225, and 450 million allogeneic STRO-3-positive MSCs) or cell media, 1 h post-induced MI. When compared with control, low-dose (25 and 75 million) cell treatment significantly attenuated infarct expansion and increases in LV end-diastolic volume and LV end-systolic volume. LVEF was improved at all cell doses. On the other hand, Schuleri et al. (146) reported a significant reduction in infarct size in high-dose (200 million) autologous MSC-treated swine compared with low-dose (20 million) autologous MSC-treated animals. The regional contractility, as assessed by tagged MRI-derived peak Eulerian circumferential shortening, was improved in both groups, although the contractility of the infarct zone was improved only in the higher dose-treated animals (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Dose responsiveness of cardiac functional recovery to intramyocardial MSCs. Plots depict peak circumferential shortening (peak Ecc) in the infarct, border, and remote zones. Peak negative Ecc values represent myocardial shortening and increased contractility, whereas increasingly positive values indicate myocardial dysfunction. Ecc improves after cell therapy in both low- and high-dose cell groups in border zones. In contrast, Ecc improves in infarct zones only in the high- and not the low-dose MSC group, consistent with a dose-response effect to MSC therapy in that zone. *P < 0.05 vs. placebo; †P < 0.05 week 12 vs. week 24. Reproduced with permission from Schuleri et al, European Heart Journal, 2009 (146).

Emerging Trends

Although cell therapy has progressed substantially since the landmark trials at the beginning of the 21st century, many questions remain unanswered regarding the best cell type, the source of cells, the route of delivery, the timing of the intervention, and the number of the cells needed. Studies have suggested that cells harvested from patients do not show the same benefit as those from healthy individuals (52), highlighting the need for a better understanding of the mechanisms leading to stem cell function and dysfunction. There is a plethora of preclinical studies that suggest strategies to improve homing and engraftment capacity of stem cells, which will potentially translate into better clinical results (71, 134, 157). Two potentially exciting possibilities are the combining of different stem cells or the combination of cell and gene therapy. Recently, microRNAs have assumed a role as potential regulators of cardiovascular biology, vascular growth, and stem cell differentiation and may be attractive targets to optimize cell-based therapies (25).

A major issue with cell-based therapy is cell survival, and the recipient environment seems to play a major role. Human MSCs were injected into rat infarcted or healthy myocardium and after 28 days; 90% of human MSCs were still found in the healthy myocardium, whereas only 18% of those injected in the infarcted zone were detectable (88). This observation supports the idea that ischemia creates an unfavorable environment, likely because of locally expressed proinflammatory cytokines inducing cell apoptosis (47). Preconditioning, by incubation of stem cells with prosurvival factors (e.g., stromal derived factor 1a) (126), increased cell survival by 20% and reduced the number of dying cells in the peri-infarct region by 33%. A more complicated approach is transfection of stem cells with prosurvival or antiapoptotic (i.e., Bcl-2) genes (97). Another focus of genetic modification of stem cells is the serine-threonine kinases, Akt, and its downstream target Pim-1, both of which appear to play a crucial prosurvival signaling role in the myocardium (32, 116). Normally, the expression of Pim-1 is low in mature human and murine myocardium. MI and its sequelae are accompanied by a reactivation of Akt and Pim-1 signaling, but this overexpression after injury is apparently insufficient to (completely) reverse the damage (116). Fischer et al. (46) modified CSCs to stably overexpress Pim-1 and injected them into murine infarcted myocardium. They reported greater levels of cellular engraftment, survival, and functional improvement for Pim-1-overexpressing cells relative to control 32 wk postdelivery.

Preconditioning the recipient environment represents another therapeutic approach. Activation of the Akt system reduced post-MI myocardial apoptosis by ∼41% and infarct size by 7% in a rodent model (78). Alternatively, inhibition of local inflammation may increase cell survival. Patel et al. (127) used an adenosine agonist at the time of coronary reperfusion in a canine MI model and reported a 16% reduction of infarct size. Moreover, simultaneous delivery of MSCs and VEGF to ischemic myocardium increased MSC survival by almost threefold (134).

Laflamme et al. (87) coinjected a “cocktail” of six different agents together with cardiomyocytes derived from ESCs in a murine heart post-MI. Each agent was chosen based on a different beneficial function. Z-Val-Ala-Asp-fluoromethylketone was used to inhibit caspase-induced apoptosis, cyclosporine and Bcl-XL peptide to block different mitochondrial death pathways, pinacildil to open ATP dependent potassium channels, Matrigel to prevent anoikis, and insulin growth factor-1 to promote cell proliferation. This combinatorial approach resulted in a 2.5-fold increase in LV wall thickening and suggests that a combination of cell types and/or factors will prove the most efficacious in eliciting a favorable remodeling response. Evidence to this effect is found in a preliminary report in a porcine MI model showing that the combination of MSCs and CSCs is more effective at reverse remodeling than either cell type alone (178).

Conclusion

In summary, the use of cell-based therapy in acute MI and chronic ischemic cardiomyopathy is rapidly emerging as a therapeutic approach with enormous clinical potential. This cell-based approach also holds promise for the treatment of nonischemic DCM. The next phase of work will likely focus not only on determining the best cell type(s) to use but, more importantly, the mechanisms by which these cells interact with host cells and elicit their therapeutic effects. As mechanistic understanding evolves, there is the growing opportunity to enhance the production and utilization of novel formulations of cell-based therapeutics.

GRANTS

J. M. Hare is supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants RO1-HL-094849, P20-HL-101443, RO1-HL-084275, RO1-HL-107110, and RO1-HL-110737.

DISCLOSURES

J. M. Hare and K. E. Hatzistergos are listed on a patent for cardiac cell-based therapy. J. M. Hare is a consultant to Kardia and receives research support from Biocardia.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

V.K. prepared figures; V.K. drafted manuscript; V.K., W.B., I.H.S., K.H., and J.M.H. edited and revised manuscript; V.K., W.B., I.H.S., K.H., and J.M.H. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1. Aharinejad S, Abraham D, Paulus P, Zins K, Hofmann M, Michlits W, Gyongyosi M, Macfelda K, Lucas T, Trescher K, Grimm M, Stanley ER. Colony-stimulating factor-1 transfection of myoblasts improves the repair of failing myocardium following autologous myoblast transplantation. Cardiovasc Res 79: 395–404, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ahn WS, Jeon JJ, Jeong YR, Lee SJ, Yoon SK. Effect of culture temperature on erythropoietin production and glycosylation in a perfusion culture of recombinant CHO cells. Biotechnol Bioeng 101: 1234–1244, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Amado LC, Saliaris AP, Schuleri KH, John M, Xie JS, Cattaneo S, Durand DJ, Fitton T, Kuang JQ, Stewart G, Lehrke S, Baumgartner WW, Martin BJ, Heldman AW, Hare JM. Cardiac repair with intramyocardial injection of allogeneic mesenchymal stem cells after myocardial infarction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 11474–11479, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Arita NA, Pelaez D, Cheung HS. Activation of the extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2 (ERK1/2) is needed for the TGFbeta-induced chondrogenic and osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 405: 564–569, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Asahara T, Murohara T, Sullivan A, Silver M, van der Zee R, Li T, Witzenbichler B, Schatteman G, Isner JM. Isolation of putative progenitor endothelial cells for angiogenesis. Science 275: 964–967, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Assmus B, Iwasaki M, Schachinger V, Roexe T, Koyanagi M, Iekushi K, Xu Q, Tonn T, Seifried E, Liebner S, Kranert WT, Grunwald F, Dimmeler S, Zeiher AM. Acute myocardial infarction activates progenitor cells and increases Wnt signalling in the bone marrow. Eur Heart J. 2011. December 15 [Epub ahead of print.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Augello A, De Bari C. The regulation of differentiation in mesenchymal stem cells. Hum Gene Ther 21: 1226–1238, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Balsam LB, Wagers AJ, Christensen JL, Kofidis T, Weissman IL, Robbins RC. Haematopoietic stem cells adopt mature haematopoietic fates in ischaemic myocardium. Nature 428: 668–673, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Barbash IM, Chouraqui P, Baron J, Feinberg MS, Etzion S, Tessone A, Miller L, Guetta E, Zipori D, Kedes LH, Kloner RA, Leor J. Systemic delivery of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells to the infarcted myocardium: feasibility, cell migration, and body distribution. Circulation 108: 863–868, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Barile L, Chimenti I, Gaetani R, Forte E, Miraldi F, Frati G, Messina E, Giacomello A. Cardiac stem cells: isolation, expansion and experimental use for myocardial regeneration. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med 4, Suppl 1: S9–S14, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bearzi C, Rota M, Hosoda T, Tillmanns J, Nascimbene A, De Angelis A, Yasuzawa-Amano S, Trofimova I, Siggins RW, Lecapitaine N, Cascapera S, Beltrami AP, D'Alessandro DA, Zias E, Quaini F, Urbanek K, Michler RE, Bolli R, Kajstura J, Leri A, Anversa P. Human cardiac stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 14068–14073, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Beltrami AP, Barlucchi L, Torella D, Baker M, Limana F, Chimenti S, Kasahara H, Rota M, Musso E, Urbanek K, Leri A, Kajstura J, Nadal-Ginard B, Anversa P. Adult cardiac stem cells are multipotent and support myocardial regeneration. Cell 114: 763–776, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Beltrami AP, Urbanek K, Kajstura J, Yan SM, Finato N, Bussani R, Nadal-Ginard B, Silvestri F, Leri A, Beltrami CA, Anversa P. Evidence that human cardiac myocytes divide after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 344: 1750–1757, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bersell K, Arab S, Haring B, Kuhn B. Neuregulin1/ErbB4 signaling induces cardiomyocyte proliferation and repair of heart injury. Cell 138: 257–270, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Blum B, Benvenisty N. The tumorigenicity of human embryonic stem cells. Adv Cancer Res 100: 133–158, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bock-Marquette I, Shrivastava S, Pipes GC, Thatcher JE, Blystone A, Shelton JM, Galindo CL, Melegh B, Srivastava D, Olson EN, DiMaio JM. Thymosin beta4 mediated PKC activation is essential to initiate the embryonic coronary developmental program and epicardial progenitor cell activation in adult mice in vivo. J Mol Cell Cardiol 46: 728–738, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Boland GM, Perkins G, Hall DJ, Tuan RS. Wnt 3a promotes proliferation and suppresses osteogenic differentiation of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. J Cell Biochem 93: 1210–1230, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bolli R, Chugh AR, D'Amario D, Loughran JH, Stoddard MF, Ikram S, Beache GM, Wagner SG, Leri A, Hosoda T, Sanada F, Elmore JB, Goichberg P, Cappetta D, Solankhi NK, Fahsah I, Rokosh DG, Slaughter MS, Kajstura J, Anversa P. Cardiac stem cells in patients with ischaemic cardiomyopathy (SCIPIO): initial results of a randomised phase 1 trial. Lancet 378: 1847–1857, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 19. Buckingham M. Skeletal muscle formation in vertebrates. Curr Opin Genet Dev 11: 440–448, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bui QT, Gertz ZM, Wilensky RL. Intracoronary delivery of bone-marrow-derived stem cells. Stem Cell Res Ther 1: 29, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Caplan AI. Mesenchymal stem cells. J Orthop Res 9: 641–650, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Castaldo C, Di Meglio F, Nurzynska D, Romano G, Maiello C, Bancone C, Muller P, Bohm M, Cotrufo M, Montagnani S. CD117-positive cells in adult human heart are localized in the subepicardium, and their activation is associated with laminin-1 and alpha6 integrin expression. Stem Cells 26: 1723–1731, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cetrulo CL., Jr Cord-blood mesenchymal stem cells and tissue engineering. Stem Cell Rev 2: 163–168, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chabannes D, Hill M, Merieau E, Rossignol J, Brion R, Soulillou JP, Anegon I, Cuturi MC. A role for heme oxygenase-1 in the immunosuppressive effect of adult rat and human mesenchymal stem cells. Blood 110: 3691–3694, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chamorro-Jorganes A, Araldi E, Penalva LO, Sandhu D, Fernandez-Hernando C, Suarez Y. MicroRNA-16 and microRNA-424 regulate cell-autonomous angiogenic functions in endothelial cells via targeting vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 and fibroblast growth factor receptor-1. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 31: 2595–2606, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Charbord P, Livne E, Gross G, Haupl T, Neves NM, Marie P, Bianco P, Jorgensen C. Human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells: a systematic reappraisal via the genostem experience. Stem Cell Rev 7: 32–42, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chen MY, Lie PC, Li ZL, Wei X. Endothelial differentiation of Wharton's jelly-derived mesenchymal stem cells in comparison with bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Exp Hematol 37: 629–640, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chen SL, Fang WW, Qian J, Ye F, Liu YH, Shan SJ, Zhang JJ, Lin S, Liao LM, Zhao RC. Improvement of cardiac function after transplantation of autologous bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Chin Med J (Engl) 117: 1443–1448, 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chong JJ, Chandrakanthan V, Xaymardan M, Asli NS, Li J, Ahmed I, Heffernan C, Menon MK, Scarlett CJ, Rashidianfar A, Biben C, Zoellner H, Colvin EK, Pimanda JE, Biankin AV, Zhou B, Pu WT, Prall OW, Harvey RP. Adult cardiac-resident MSC-like stem cells with a proepicardial origin. Cell Stem Cell 9: 527–540, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Christman KL, Fok HH, Sievers RE, Fang Q, Lee RJ. Fibrin glue alone and skeletal myoblasts in a fibrin scaffold preserve cardiac function after myocardial infarction. Tissue Eng 10: 403–409, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Christman KL, Vardanian AJ, Fang Q, Sievers RE, Fok HH, Lee RJ. Injectable fibrin scaffold improves cell transplant survival, reduces infarct expansion, and induces neovasculature formation in ischemic myocardium. J Am Coll Cardiol 44: 654–660, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cook SA, Matsui T, Li L, Rosenzweig A. Transcriptional effects of chronic Akt activation in the heart. J Biol Chem 277: 22528–22533, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. da Silva Meirelles L, Chagastelles PC, Nardi NB. Mesenchymal stem cells reside in virtually all post-natal organs and tissues. J Cell Sci 119: 2204–2213, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Dai W, Wold LE, Dow JS, Kloner RA. Thickening of the infarcted wall by collagen injection improves left ventricular function in rats: a novel approach to preserve cardiac function after myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 46: 714–719, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Davis ME, Hsieh PC, Takahashi T, Song Q, Zhang S, Kamm RD, Grodzinsky AJ, Anversa P, Lee RT. Local myocardial insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) delivery with biotinylated peptide nanofibers improves cell therapy for myocardial infarction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 8155–8160, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Davis ME, Motion JP, Narmoneva DA, Takahashi T, Hakuno D, Kamm RD, Zhang S, Lee RT. Injectable self-assembling peptide nanofibers create intramyocardial microenvironments for endothelial cells. Circulation 111: 442–450, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Day TF, Guo X, Garrett-Beal L, Yang Y. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in mesenchymal progenitors controls osteoblast and chondrocyte differentiation during vertebrate skeletogenesis. Dev Cell 8: 739–750, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Di Meglio F, Castaldo C, Nurzynska D, Romano V, Miraglia R, Montagnani S. Epicardial cells are missing from the surface of hearts with ischemic cardiomyopathy: a useful clue about the self-renewal potential of the adult human heart? Int J Cardiol 145: e44–e46, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Di Nicola M, Carlo-Stella C, Magni M, Milanesi M, Longoni PD, Matteucci P, Grisanti S, Gianni AM. Human bone marrow stromal cells suppress T-lymphocyte proliferation induced by cellular or nonspecific mitogenic stimuli. Blood 99: 3838–3843, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Diaz-Solano D, Wittig O, Ayala-Grosso C, Pieruzzini R, Cardier JE. Human olfactory mucosa multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells promote survival, proliferation and differentiation of human hematopoietic cells. Stem Cells Dev 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Draper JS, Pigott C, Thomson JA, Andrews PW. Surface antigens of human embryonic stem cells: changes upon differentiation in culture. J Anat 200: 249–258, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Dulce RA, Balkan W, Hare JM, Schulman IH. Wnt signalling: a mediator of the heart-bone marrow axis after myocardial injury? Eur Heart J. 2011. December 23 [Epub ahead of print.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Engel FB. Cardiomyocyte proliferation: a platform for mammalian cardiac repair. Cell Cycle 4: 1360–1363, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Etheridge SL, Spencer GJ, Heath DJ, Genever PG. Expression profiling and functional analysis of wnt signaling mechanisms in mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells 22: 849–860, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Fijnvandraat AC, van Ginneken AC, Schumacher CA, Boheler KR, Lekanne Deprez RH, Christoffels VM, Moorman AF. Cardiomyocytes purified from differentiated embryonic stem cells exhibit characteristics of early chamber myocardium. J Mol Cell Cardiol 35: 1461–1472, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Fischer KM, Cottage CT, Wu W, Din S, Gude NA, Avitabile D, Quijada P, Collins BL, Fransioli J, Sussman MA. Enhancement of myocardial regeneration through genetic engineering of cardiac progenitor cells expressing Pim-1 kinase. Circulation 120: 2077–2087, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Forrester JS, Libby P. The inflammation hypothesis and its potential relevance to statin therapy. Am J Cardiol 99: 732–738, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Fuchs E, Tumbar T, Guasch G. Socializing with the neighbors: stem cells and their niche. Cell 116: 769–778, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Fujimoto KL, Ma Z, Nelson DM, Hashizume R, Guan J, Tobita K, Wagner WR. Synthesis, characterization and therapeutic efficacy of a biodegradable, thermoresponsive hydrogel designed for application in chronic infarcted myocardium. Biomaterials 30: 4357–4368, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Gaudette GR, Cohen IS. Cardiac regeneration: materials can improve the passive properties of myocardium, but cell therapy must do more. Circulation 114: 2575–2577, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Gehling UM, Ergun S, Schumacher U, Wagener C, Pantel K, Otte M, Schuch G, Schafhausen P, Mende T, Kilic N, Kluge K, Schafer B, Hossfeld DK, Fiedler W. In vitro differentiation of endothelial cells from AC133-positive progenitor cells. Blood 95: 3106–3112, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Giannotti G, Doerries C, Mocharla PS, Mueller MF, Bahlmann FH, Horvath T, Jiang H, Sorrentino SA, Steenken N, Manes C, Marzilli M, Rudolph KL, Luscher TF, Drexler H, Landmesser U. Impaired endothelial repair capacity of early endothelial progenitor cells in prehypertension: relation to endothelial dysfunction. Hypertension 55: 1389–1397, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Gmeiner M, Zimpfer D, Holfeld J, Seebacher G, Abraham D, Grimm M, Aharinejad S. Improvement of cardiac function in the failing rat heart after transfer of skeletal myoblasts engineered to overexpress placental growth factor. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 141: 1238–1245, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Gnecchi M, Zhang Z, Ni A, Dzau VJ. Paracrine mechanisms in adult stem cell signaling and therapy. Circ Res 103: 1204–1219, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Gramsch B, Gabriel HD, Wiemann M, Grummer R, Winterhager E, Bingmann D, Schirrmacher K. Enhancement of connexin 43 expression increases proliferation and differentiation of an osteoblast-like cell line. Exp Cell Res 264: 397–407, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Griffin MD, Ritter T, Mahon BP. Immunological aspects of allogeneic mesenchymal stem cell therapies. Hum Gene Ther 21: 1641–1655, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Guo J, Lin G, Bao C, Hu Z, Chu H, Hu M. Insulin-like growth factor 1 improves the efficacy of mesenchymal stem cells transplantation in a rat model of myocardial infarction. J Biomed Sci 15: 89–97, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hamamoto H, Gorman JH, 3rd, Ryan LP, Hinmon R, Martens TP, Schuster MD, Plappert T, Kiupel M, John-Sutton MG, St, Itescu S, Gorman RC. Allogeneic mesenchymal precursor cell therapy to limit remodeling after myocardial infarction: the effect of cell dosage. Ann Thorac Surg 87: 794–801, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Hare JM. Bone marrow therapy for myocardial infarction. JAMA 306: 2156–2157, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Hare JM, Traverse JH, Henry TD, Dib N, Strumpf RK, Schulman SP, Gerstenblith G, DeMaria AN, Denktas AE, Gammon RS, Hermiller JB, Jr, Reisman MA, Schaer GL, Sherman W. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-escalation study of intravenous adult human mesenchymal stem cells (prochymal) after acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 54: 2277–2286, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Hatzistergos KE, Quevedo H, Oskouei BN, Hu Q, Feigenbaum GS, Margitich IS, Mazhari R, Boyle AJ, Zambrano JP, Rodriguez JE, Dulce R, Pattany PM, Valdes D, Revilla C, Heldman AW, McNiece I, Hare JM. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells stimulate cardiac stem cell proliferation and differentiation. Circ Res 107: 913–922, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Hierlihy AM, Seale P, Lobe CG, Rudnicki MA, Megeney LA. The post-natal heart contains a myocardial stem cell population. FEBS Lett 530: 239–243, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Ho JH, Ma WH, Su Y, Tseng KC, Kuo TK, Lee OK. Thymosin beta-4 directs cell fate determination of human mesenchymal stem cells through biophysical effects. J Orthop Res 28: 131–138, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Ieda M, Fu JD, Delgado-Olguin P, Vedantham V, Hayashi Y, Bruneau BG, Srivastava D. Direct reprogramming of fibroblasts into functional cardiomyocytes by defined factors. Cell 142: 375–386, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Jackson KA, Majka SM, Wang H, Pocius J, Hartley CJ, Majesky MW, Entman ML, Michael LH, Hirschi KK, Goodell MA. Regeneration of ischemic cardiac muscle and vascular endothelium by adult stem cells. J Clin Invest 107: 1395–1402, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Jiang XX, Zhang Y, Liu B, Zhang SX, Wu Y, Yu XD, Mao N. Human mesenchymal stem cells inhibit differentiation and function of monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Blood 105: 4120–4126, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Jones EA, Kinsey SE, English A, Jones RA, Straszynski L, Meredith DM, Markham AF, Jack A, Emery P, McGonagle D. Isolation and characterization of bone marrow multipotential mesenchymal progenitor cells. Arthritis Rheum 46: 3349–3360, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Jopling C, Sleep E, Raya M, Marti M, Raya A, Izpisua Belmonte JC. Zebrafish heart regeneration occurs by cardiomyocyte dedifferentiation and proliferation. Nature 464: 606–609, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Kajstura J, Rota M, Whang B, Cascapera S, Hosoda T, Bearzi C, Nurzynska D, Kasahara H, Zias E, Bonafe M, Nadal-Ginard B, Torella D, Nascimbene A, Quaini F, Urbanek K, Leri A, Anversa P. Bone marrow cells differentiate in cardiac cell lineages after infarction independently of cell fusion. Circ Res 96: 127–137, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Kamihata H, Matsubara H, Nishiue T, Fujiyama S, Tsutsumi Y, Ozono R, Masaki H, Mori Y, Iba O, Tateishi E, Kosaki A, Shintani S, Murohara T, Imaizumi T, Iwasaka T. Implantation of bone marrow mononuclear cells into ischemic myocardium enhances collateral perfusion and regional function via side supply of angioblasts, angiogenic ligands, and cytokines. Circulation 104: 1046–1052, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Kanashiro-Takeuchi RM, Schulman IH, Hare JM. Pharmacologic and genetic strategies to enhance cell therapy for cardiac regeneration. J Mol Cell Cardiol 51: 619–625, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Kapoor N, Galang G, Marban E, Cho HC. Transcriptional suppression of connexin43 by TBX18 undermines cell-cell electrical coupling in postnatal cardiomyocytes. J Biol Chem 286: 14073–14079, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Khoury M, Drake A, Chen Q, Dong D, Leskov I, Fragoso MF, Li Y, Iliopoulou BP, Hwang W, Lodish HF, Chen J. Mesenchymal stem cells secreting angiopoietin-like-5 support efficient expansion of human hematopoietic stem cells without compromising their repopulating potential. Stem Cells Dev 20: 1371–1381, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Kikuchi K, Holdway JE, Werdich AA, Anderson RM, Fang Y, Egnaczyk GF, Evans T, Macrae CA, Stainier DY, Poss KD. Primary contribution to zebrafish heart regeneration by gata4+ cardiomyocytes. Nature 464: 601–605, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Kim BO, Tian H, Prasongsukarn K, Wu J, Angoulvant D, Wnendt S, Muhs A, Spitkovsky D, Li RK. Cell transplantation improves ventricular function after a myocardial infarction: a preclinical study of human unrestricted somatic stem cells in a porcine model. Circulation 112: I96–I104, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Kinnaird T, Stabile E, Burnett MS, Lee CW, Barr S, Fuchs S, Epstein SE. Marrow-derived stromal cells express genes encoding a broad spectrum of arteriogenic cytokines and promote in vitro and in vivo arteriogenesis through paracrine mechanisms. Circ Res 94: 678–685, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Kitaori T, Ito H, Schwarz EM, Tsutsumi R, Yoshitomi H, Oishi S, Nakano M, Fujii N, Nagasawa T, Nakamura T. Stromal cell-derived factor 1/CXCR4 signaling is critical for the recruitment of mesenchymal stem cells to the fracture site during skeletal repair in a mouse model. Arthritis Rheum 60: 813–823, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Klopsch C, Furlani D, Gabel R, Li W, Pittermann E, Ugurlucan M, Kundt G, Zingler C, Titze U, Wang W, Ong LL, Wagner K, Li RK, Ma N, Steinhoff G. Intracardiac injection of erythropoietin induces stem cell recruitment and improves cardiac functions in a rat myocardial infarction model. J Cell Mol Med 13: 664–679, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Klyushnenkova E, Mosca JD, Zernetkina V, Majumdar MK, Beggs KJ, Simonetti DW, Deans RJ, McIntosh KR. T cell responses to allogeneic human mesenchymal stem cells: immunogenicity, tolerance, and suppression. J Biomed Sci 12: 47–57, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Kocher AA, Schuster MD, Szabolcs MJ, Takuma S, Burkhoff D, Wang J, Homma S, Edwards NM, Itescu S. Neovascularization of ischemic myocardium by human bone-marrow-derived angioblasts prevents cardiomyocyte apoptosis, reduces remodeling and improves cardiac function. Nat Med 7: 430–436, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Kofidis T, de Bruin JL, Hoyt G, Lebl DR, Tanaka M, Yamane T, Chang CP, Robbins RC. Injectable bioartificial myocardial tissue for large-scale intramural cell transfer and functional recovery of injured heart muscle. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 128: 571–578, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Kofidis T, Lebl DR, Martinez EC, Hoyt G, Tanaka M, Robbins RC. Novel injectable bioartificial tissue facilitates targeted, less invasive, large-scale tissue restoration on the beating heart after myocardial injury. Circulation 112: I173–I177, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Kogler G, Sensken S, Airey JA, Trapp T, Muschen M, Feldhahn N, Liedtke S, Sorg RV, Fischer J, Rosenbaum C, Greschat S, Knipper A, Bender J, Degistirici O, Gao J, Caplan AI, Colletti EJ, Almeida-Porada G, Muller HW, Zanjani E, Wernet P. A new human somatic stem cell from placental cord blood with intrinsic pluripotent differentiation potential. J Exp Med 200: 123–135, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Krampera M, Cosmi L, Angeli R, Pasini A, Liotta F, Andreini A, Santarlasci V, Mazzinghi B, Pizzolo G, Vinante F, Romagnani P, Maggi E, Romagnani S, Annunziato F. Role for interferon-gamma in the immunomodulatory activity of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells 24: 386–398, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Kuhn B, del Monte F, Hajjar RJ, Chang YS, Lebeche D, Arab S, Keating MT. Periostin induces proliferation of differentiated cardiomyocytes and promotes cardiac repair. Nat Med 13: 962–969, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Lacis A, Erglis A. Intramyocardial administration of autologous bone marrow mononuclear cells in a critically ill child with dilated cardiomyopathy. Cardiol Young 21: 110–112, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Laflamme MA, Chen KY, Naumova AV, Muskheli V, Fugate JA, Dupras SK, Reinecke H, Xu C, Hassanipour M, Police S, O'Sullivan C, Collins L, Chen Y, Minami E, Gill EA, Ueno S, Yuan C, Gold J, Murry CE. Cardiomyocytes derived from human embryonic stem cells in pro-survival factors enhance function of infarcted rat hearts. Nat Biotechnol 25: 1015–1024, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Laflamme MA, Gold J, Xu C, Hassanipour M, Rosler E, Police S, Muskheli V, Murry CE. Formation of human myocardium in the rat heart from human embryonic stem cells. Am J Pathol 167: 663–671, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Laugwitz KL, Moretti A, Lam J, Gruber P, Chen Y, Woodard S, Lin LZ, Cai CL, Lu MM, Reth M, Platoshyn O, Yuan JX, Evans S, Chien KR. Postnatal isl1+ cardioblasts enter fully differentiated cardiomyocyte lineages. Nature 433: 647–653, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Lavine KJ, White AC, Park C, Smith CS, Choi K, Long F, Hui CC, Ornitz DM. Fibroblast growth factor signals regulate a wave of Hedgehog activation that is essential for coronary vascular development. Genes Dev 20: 1651–1666, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Leistner DM, Fischer-Rasokat U, Honold J, Seeger FH, Schachinger V, Lehmann R, Martin H, Burck I, Urbich C, Dimmeler S, Zeiher AM, Assmus B. Transplantation of progenitor cells and regeneration enhancement in acute myocardial infarction (TOPCARE-AMI): final 5-year results suggest long-term safety and efficacy. Clin Res Cardiol 100: 925–934, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Leor J, Tuvia S, Guetta V, Manczur F, Castel D, Willenz U, Petnehazy O, Landa N, Feinberg MS, Konen E, Goitein O, Tsur-Gang O, Shaul M, Klapper L, Cohen S. Intracoronary injection of in situ forming alginate hydrogel reverses left ventricular remodeling after myocardial infarction in Swine. J Am Coll Cardiol 54: 1014–1023, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Leri A, Kajstura J, Anversa P. Cardiac stem cells and mechanisms of myocardial regeneration. Physiol Rev 85: 1373–1416, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Leri A, Kajstura J, Anversa P. Role of cardiac stem cells in cardiac pathophysiology: a paradigm shift in human myocardial biology. Circ Res 109: 941–961, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 95. Li TS, Cheng K, Lee ST, Matsushita S, Davis D, Malliaras K, Zhang Y, Matsushita N, Smith RR, Marban E. Cardiospheres recapitulate a niche-like microenvironment rich in stemness and cell-matrix interactions, rationalizing their enhanced functional potency for myocardial repair. Stem Cells 28: 2088–2098, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Li TS, Cheng K, Malliaras K, Smith RR, Zhang Y, Sun B, Matsushita N, Blusztajn A, Terrovitis J, Kusuoka H, Marban L, Marban E. Direct comparison of different stem cell types and subpopulations reveals superior paracrine potency and myocardial repair efficacy with cardiosphere-derived cells. J Am Coll Cardiol 59: 942–953, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Li W, Ma N, Ong LL, Nesselmann C, Klopsch C, Ladilov Y, Furlani D, Piechaczek C, Moebius JM, Lutzow K, Lendlein A, Stamm C, Li RK, Steinhoff G. Bcl-2 engineered MSCs inhibited apoptosis and improved heart function. Stem Cells 25: 2118–2127, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]