Abstract

Bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling in diseases is the subject of an overwhelming array of studies. BMPs are excellent targets for treatment of various clinical disorders. Several BMPs have already been shown to be clinically beneficial in the treatment of a variety of conditions, including BMP-2 and BMP-7 that have been approved for clinical application in nonunion bone fractures and spinal fusions. With the use of BMPs increasingly accepted in spinal fusion surgeries, other therapeutic approaches targeting BMP signaling are emerging beyond applications to skeletal disorders. These approaches can further utilize next-generation therapeutic tools such as engineered BMPs and ex vivo-conditioned cell therapies. In this review, we focused to provide insights into such clinical potentials of BMPs in metabolic and vascular diseases, and in cancer.

Keywords: BMP, Cancer, Diabetes, Obesity, Pulmonary hypertension, TGF-beta

INTRODUCTION

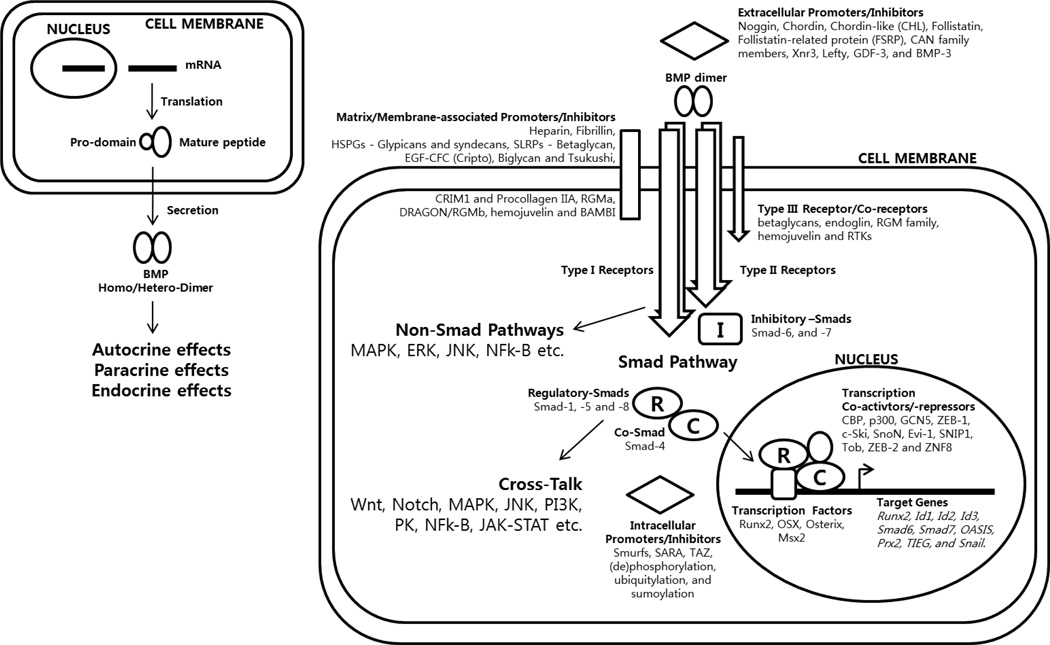

Bone Morphogenetic Proteins (BMPs) represent the largest subset within the Transforming Growth Factor (TGF)-β superfamily. They are now known to be involved in such a wide variety of processes that several investigators even suggested to change their name from ‘Bone’ to ‘Body’ Morphogenetic Proteins (1, 2). Although they share some fundamental similarities with other members of the TGF-β superfamily, the pleomorphic functions of BMPs led to their signaling functions being regulated at such complex levels that far exceed those imposed on the other members of the TGF-β superfamily (Fig. 1). One hallmark feature of BMPs is that there is a high degree of promiscuity in the interaction of ligands with their receptors and regulators that are also shared with other members of the TGF-β superfamily (Table 1, 2). Hence, the final outcome of BMP signal transduction is highly dependent on spatiotemporal circumstances in addition to the endocrine properties of those that are secreted into circulation. This requires careful examinations of potentially-overlapping signaling pathways to understand molecular mechanisms of their in vivo biological activity, thus to evaluate their potential clinical benefits. Nonetheless, the importance of BMP signals in pathophysiology cannot be overstated because of the multitude of dysregulated BMP signaling in numerous pathological processes. Clinically, BMP family members have been associated with a number of pathologies, including obesity, diabetes, various vascular diseases as well as cancer and its related comorbidities. This review will discuss selected clinical targets of the BMP signaling whose therapeutic potential have been substantiated through both in vitro and in vivo studies.

Fig. 1.

BMP synthesis to signaling.

Table 1.

Human BMPs

| Ligand | Alternate names | Gene locus | Known receptors | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type I receptors | Type II receptors | Type III receptors | |||

| BMP-1 | BMP-1 is a metalloproteinase, not a formal member of the TGF-β superfamily. | ||||

| BMP-2 | BMP-2A, XBMP2, xBMP-2, MGC114605 | 20p12 | ALK-2, ALK-3, ALK-6 | BMPR-II; ActR-IIA, ActR-IIB | TGF-βR-III; Endoglin |

| BMP-3 | Osteogenin, BMP-3A | 14p21.21 | ALK-4 | ActR-IIA, ActR-IIB | |

| BMP-4 | BMP-2B, BMP2B1, ZYME, OFC11, MCOPS6 | 14q22–q23 | ALK-2, ALK-3, ALK-5, ALK-6 | BMPR-II; ActR-IIA | TGF-βR-III |

| BMP-5 | MGC34244 | 6p12.1 | ALK-3 | ||

| BMP-6 | Vgr1, DVR-6 | 6p24-p23 | ALK-2, ALK-3, ALK-6 | BMPR-II; ActR-IIA, ActR-IIB | |

| BMP-7 | OP-1 | 20q13 | ALK-2, ALK-3, ALK-6 | BMPR-II; ActR-IIA, ActR-IIB | |

| BMP-8A | OP-2, FLJ14351, FLJ45264 | 1p34.3 | ALK-2; ALK-3; ALK-4; ALK-7 | BMPR-II; AMHR-II; | |

| BMP-8B | OP-3, PC-8, MGC131757 | 1p35-p32 | ALK-3; ALK-6 | BMPR-II; AMHR-II | |

| BMP-9 | GDF-2 | 10q11.22 | ALK-1, ALK-2 | BMPR-II; ActR-IIA, ActR-IIB | Endoglin |

| BMP-10 | MGC126783 | 2p13.3 | ALK-1, ALK-3, ALK-6 | BMPR-II; ActR-IIA, ActR-IIB | |

| BMP-11 | GDF-11 | 12q13.2 | ALK-3, ALK-4, ALK-5, ALK-7 | ActR-IIA, ActR-IIB | |

| BMP-12 | GDF-7, CDMP-3 | 2p24.1 | ALK-3, ALK-6 | BMPR-II;ActR-IIA, ActR-IIB | |

| BMP-13 | GDF-6, CDMP-2, KFS, KFSL, SGM1, MGC158100, MGC158101 | 8q22.1 | ALK-3, ALK-6 | BMPR-II; ActR-IIA | |

| BMP-14 | GDF-5, CDMP-1, OS5, LAP4, SYNS2, MP52 | 20q11.2 | ALK-3, ALK-6 | BMPR-II; ActR-IIA, ActR-IIB BMPR-II; ActR-IIA | TGF-βR-III |

| BMP-15 | GDF-9B, ODG2, POF4 | Xp11.2 | ALK-6 | ||

Table 2.

Receptors that BMPs share with other TGF-β superfamily members

| Type I receptors (also termed Activin receptor-like kinases, ALK) |

Ligands |

|---|---|

| ALK-1 | BMPs |

| ALK-2 or ActR-IA | BMPs, Activin |

| ALK-3 or BMPR-IA | BMPs |

| ALK-4 or ActR-IB | TGF-β, Activin, BMPs |

| ALK-5 or TβR-I | TGF-β, Activin, BMPs |

| ALK-6 or BMPR-IB | BMPs, AMH |

| ALK-7 or ActIR-IC | Activin, BMPs |

| Type II receptors | Ligands |

| Activin type IIA (ActR-IIA) | Activin, BMPs |

| Activin type IIB (ActR-IIB) | Activin, BMPs |

| TGF-β type II receptor (TβR-II) | TGF-β |

| BMP type II receptor (BMPR-II) | BMPs |

| BMP type II receptor (shorter form) | BMPs |

| Anti-Mullerian hormone type II receptor (AMHR-II) | AMH, BMPs |

METABOLIC DISEASES

Obesity

The last decade has witnessed an ever-growing surge in the obesity pandemic, making obesity one of the most serious predicaments among the metabolic diseases. Rates of obesity in developed countries such as the United States exceed 33% of the population primarily caused by changes in behavior and lifestyle. Moreover, the trend toward global obesity creates a substantial increase in incidences of various metabolic syndromes, such as type 2 diabetes mellitus, liver steatosis and cirrhosis, hypertension, coronary heart disease, as well as neurodegenerative Alzheimer’s disease and even some cancers (3–7). Treatment of obesity-related morbidities has imposed a huge economic burden on societies, with direct annual cost estimates for medical spending due to obesity in the United States to date being up to $147 billion for adults and $14.3 billion for children (8). Current treatment of human obesity is limited to behavioral adjustments, control of satiety, induced mal-absorption in the intestine and a variety of surgical procedures with limited efficacy, undesirable side effects, and unknown long-term consequences (9). For instance, almost all current anti-obesity drugs target the brain as appetite suppressants with a variety of adverse side effects (10, 11). Recently, BMP signaling has emerged as a promising new approach to the problem, targeting obesity from the roots. The effects of BMP signaling on adipogenesis suggest treatments that target the adipocyte-differentiation process itself and metabolic activities that favor energy expenditure.

Adipose tissue is a central player in systemic energy metabolism that exists in two forms with both shared and unique characteristics; white adipose tissue (WAT) serves as an energy reservoir, whereas the brown adipose tissue (BAT) mainly functions in energy expenditure. Both types of adipocytes developmentally arise from mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), which derive from embryonic stem cells. BMP-2 and BMP-4 promote the differentiation of WAT, whereas BMP-7 directs brown adipogenesis. Obesity is characterized by increase in WAT accumulation in the intra-abdominal visceral area (12). Increased WAT may result from increase in adipocyte size (termed hypertrophy) and/or increase in adipocyte number (termed hyperplasia) (13, 14). The hyperplasia that causes obesity results from increased number or rate of MSCs committing to the adipogenic lineage that subsequently proliferate as preadipocytes and eventually differentiate into mature adipocytes (15). Several lines of evidence indicate that commitment of MSCs into the adipogenic lineage can be strongly influenced by BMP signaling (16, 17). Elevated expression of BMP-4 has been observed precisely during the proliferation to commitment process, in addition to increased level of phosphorylated Smad 1, 5 and 8 following the same pattern (18). Exogenous BMP-4 treatment of embryonic or mesenchymal stem cells during the early proliferative stage promotes differentiation into mature adipocytes (16, 17, 19, 20). Subcutaneous injection of BMP-4-treated pluripotent stem cells into athymic mice even results in the development of adipose tissue that is indistinguishable from endogenous WAT, whereas non-treated cells do not (16). Furthermore, BMP-4 has also been shown to specifically induce white adipogenesis while suppressing brown adipogenesis, as marked by inhibited expression of a BAT marker UCP1 (17). Another BMP ligand that has been shown to promote adipogenesis is BMP-2, despite contradicting results that seem to vary on cell type, dosage and spacitotemporal differences in treatment. Similar to BMP-4, BMP-2 has also been shown to stimulate commitment of progenitors into the white adipogenic lineage, in addition to promoting terminal adipogenic differentiation (21, 22). This can be explained, at least in part, by the ability of BMP-2 to upregulate expression of a major adipogenic marker, PPAR-γ, through activation of Smad1 and subsequent cooperation with Schnurri-2 (23, 24). Accordingly, Shn-2 knockout mice (with consequentially reduced BMP-2 signaling) display reduced WAT mass, suggesting that BMP-2 utilizes the Smad pathway to regulate adipogenesis in vivo (24).

Apart from these BMPs, BMP type I receptor (BMPR-IA), ALK-3, has been associated with obesity by favoring differentiation into adipocytes rather than osteoblasts in vitro (25). ALK-3 is known to exert a much higher binding affinity to BMP-2 and BMP-4 than to BMP-7 (26), implying different roles in response to BMP-2 and BMP-4 in contrast to BMP-7. Conditional knockout mice with adipocyte-specific deletion of ALK-3 display significant reduction in body weight as well as a trend toward reduced fat mass on both normal and high fat diets (27). In humans, overweight and obese adults display higher mRNA levels of ALK-3 in visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissues, which also correlate with several parameters used to determine health, including percentage body fat as well as fasting plasma glucose and insulin levels (28). In addition, three single nucleotide polymorphisms within the ALK-3 gene were identified as obesity risk alleles, demonstrated by an association with increased body mass index (BMI) in two independent cohorts, as well as correlating with increased adipose ALK-3 mRNA levels (28).

Conversely, role of BMP antagonists in adipocyte differentiation has also been recognized. Treatment of Noggin decreases cytoplasmic triglyceride accumulation and expression of adipogenic marker genes, confirming definitive role of BMPs in adipocyte differentiation (18). In addition, expression of FSTL1 (a Follistatin-like BMP antagonist that binds and inhibits formation of BMP ligand-receptor complexes), which occurs at high levels in undifferentiated primary preadipocytes, declines rapidly during adipocyte differentiation (29). Genetic (ob/ob) and diet-induced obesity mouse models exhibit an increase in subcutaneous and decrease in visceral adipose expression of FSTL3 compared to regular diet controls (30). GDF-3, another well-known antagonist of BMP signaling, also possesses inhibitory effects in adipocyte differentiation. However, these observations should not be defined merely to modulations of BMP signaling, but rather to changes in the systematic interplay between other members of the TGF-beta superfamily, such as Activins and Myostatins.

Finally, the recent discovery of BMP-7 in promoting BAT differentiation and thermogenesis offers a new clinical potential. BMP-7 triggers commitment of MSCs to a brown adipocyte lineage (31, 32), and subcutaneous injection of these cells into athymic mice results in development of adipose tissue containing mostly BAT. BMP-7 knockout embryos display an almost complete absence of UCP1 and a marked 50–70% decrease in interscapular BAT mass compared with wild-type littermates, whereas the size of WAT and other internal organs, such as the liver, were not altered (17). Tail vein injection of adenovirus expressing BMP-7 increases BAT, without affecting the mass of WAT. Increase in BAT mass results in increased energy expenditure, higher basal body temperature and decreased body weight (17). Thus, BMP-7 promotes phenotypic characteristics and functional activity of mature brown adipocytes, which burns energy and assists in suppressing obesity. In fact, several independent teams using PET-CT (positron emission tomography-computed tomography) have revealed recently that substantial amounts of BAT is also present in humans in the cervical-supraclavicular area (neck and shoulder), particularly in young and lean female subjects (33–37).

Diabetes

In addition to regulating adipogenesis and energy metabolism, BMP signaling has been shown to be involved in glucose homeostasis. More than 5% of the US population is diagnosed with diabetes from having impaired insulin function (38). Type II diabetes is caused by defects in the secretion of insulin and resistance to the action of insulin, which accounts for >90% of diabetic cases, as opposed to type I diabetes, which is a rarer autoimmune disease that destroys pancreatic β-cells resulting in absolute requirement for exogenous insulin treatment (39, 40). Current therapies for type II diabetes improve insulin action at the level of the liver (metformin) and peripheral tissues (thiazolidinediones), or enhance insulin secretion (sulfonylureas) (41, 42). Discovery of BMP-9 as a first hepatic factor shown to regulate blood glucose concentration over an extended period of time put forward a possible new approach to treating insulin insensitivity while reducing the occurrence of side effects commonly associated with current treatments such as weight gain or hypoglycemia. BMP-9 was identified as a pharmacological and physiological target for regulating glucose metabolism (43), as it is specifically synthesized and released from the liver as a hepatic insulin-sensitizing substance (HISS) and responds to insulin for production and regulation (44, 45). 55% of glucose uptake stimulated by insulin is believed to be through the action of HISS, predominantly in skeletal muscles (46). It has been shown that BMP-9 circulates in the serum and activates Smad5, and upregulates Akt2 expression and, by stipulation, increases glucose uptake in skeletal muscle cells (47, 48). Receptors for BMP-9 have also been identified in hepatocytes and by activating these receptors. BMP-9 inhibits hepatic gluconegenesis and activates enzymes of lipid metabolism, such as malic enzyme and fatty acid synthase (FAS) (49, 50). A single subcutaneous injection of BMP-9 has been shown to reduce glycemia to near-normal levels in normal and diabetic (db/db) mice, whereas rats that received intravenous administration of BMP-9 display improved glucose tolerance and enhanced insulin sensitivity (50). These results suggest that BMP-9 is capable of acting as a systemic factor in an endocrine fashion, in addition to autocrine and paracrine manners.

VASCULAR DISEASES

Embryonic cardiac and vascular development is subject to regulation by BMP signaling as well as other pathways vital for embryogenesis (51). Since many of those pathways are reactivated after vascular injury, BMP signaling must also play crucial roles in vascular homeostasis and disease in adults (52). In fact, a number of BMPs are upregulated at sites of vascular injury, which reinforces the suggestion that they regulate normal vascular homeostasis and disease-associated vascular pathology. Hence, various components of the BMP signaling pathway have been linked to pathophysiology of vascular diseases such as vascular calcification, hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT) and pulmonary hypertension (PH).

Vascular calcification

Vascular calcification is a prominent feature of atherosclerosis and a common consequence of aging, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia and chronic renal insufficiency (53, 54). Vascular calcification can lead to aggravated hypertension and stroke, being a major risk factor for cardiovascular morbidity. Lately, the clinical importance of BMPs and related proteins in the process of vascular calcification has been discovered (55). Expression of BMP-2 and BMP-4 is upregulated in endothelial cells at sites of atherosclerotic plaques (56–58). It has also been shown that an osteogenic program is activated in the aorta of diabetic patients with atherosclerosis, including expression of BMP-2 and the osteoblasts homeobox-containing transcription factor, Msx2 (59). Msx2 has been shown to induce osteogenic over adipogenic differentiation of aortic myofibroblasts (60). BMP-2-Msx2 signaling may contribute to vascular calcification by diverting myofibroblasts capable of differentiating into either osteogenic or adipogenc lineage into the osteogenic lineage. In addition, extracellular modulators that normally inhibit BMP signaling have been associated with vascular injury and disease. Matrix gamma-carboxylated glutamate protein (MGP) is an extracellular matrix component that is produced by vascular smooth-muscle cells (VMSCs) and binds to BMPs (BMP-2 and BMP-4 in particular) to modulate BMP signaling in a concentration-dependent fashion (61, 62). Constitutive activity of MGP and other regulators of bone formation and osteoclastogenesis, along with reduced levels of BMP-2, BMP-4, osteopontin and osteonectin have been found in healthy aortas and early atherosclerotic lesions (63). Alternatively, expression levels of the same genes are upregulated as atherosclerotic plaques calcify. MGP-deficient mice develop widespread vascular calcification from progressively calcifying the tunica media into cartilage tissue (64, 65). Moreover, a poorly gamma-carboxylated form of MGP that cannot bind to BMP-2 was identified in calcified lesions of aortic wall of aging rats (60, 65). In humans, patients with Keutel syndrome, who inherit homozygous germ line mutations in MGP, display stenosis of peripheral pulmonary vessels (66). Taken together, these results strengthen the hypothesis that BMP signaling promotes vascular calcification. Besides, BMP-7 is a crucial regulator of chronic renal failure, which is a condition that is often accompanied by vascular calcification. Indeed, BMP-7 treatment has been demonstrated to be effective in preventing vascular calcification and reversing the increased osteocalcin expression levels in mouse atherosclerosis models, in addition to regenerating kidney functions in several rodent models of renal disease (67–72). Therefore, BMP-7 alone emerges as a potential therapeutic agent that can decrease vascular calcification, for which there is no adequate therapy at present.

Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT)

HHT is an autosomal dominant inheritable vascular dysplasia, in which patients develop mucosal and skin telangiectasia, pulmonary, cerebral and hepatic malformations, and hemorrhages associated with these vascular lesions. HHT is associated with mutations in three genes encoding components of the BMP signaling: ENG gene for endoglin, ACVRL1 gene for ALK-1 and SMAD4 gene (73–75). Mutations in endoglin, a co-receptor for ALK-1 results in HHT type 1 (HHT1), whereas mutations in ALK-1 itself have been identified in patients with HHT2 (76). Homozygous ALK-1 null mice die embryonically with widespread arteriovenous malformations (77–79), which is the phenotype also exhibited by endoglin null mice and BMPR-II deficient mice (80–82). These observations suggest that the BMP signaling through the three receptors - endoglin, ALK-1 and BMPR-II play a discrete role in inducing or maintaining embryonic vascular stability different from that of other members of the TGF-beta superfamily. Deletion of ALK-1 in endothelial cells (ECs) alone or heterozygous ALK-1 mutant mice that are aging also develop systemic vascular malformations and symptoms observed in human HHT2 (83–86). In order to inhibit bleeding and other vascular malformations associated with HHT, anti-angiogenic therapies have been successful (87, 88) and several clinical trials using other anti-angiogenesis agents are currently underway with more HHT patients (http://www.hht.org/). This idea implicates that BMP signaling and its close relationship with angiogenesis is a promising therapeutic target.

Pulmonary hypertension (PH)

One of the best studied vascular diseases in relation to BMP signaling is PH. PH is a severe, debilitating and progressive disease with poor prognosis, characterized by increase in blood pressure in the lung vasculature, including pulmonary-artery, -vein, and -capillaries, which eventually leads to heart failure and death (43). It is also a sequel to a variety of cardiovascular and systemic diseases. Within the last 15 years, new pharmacological agents were introduced and entered routine clinical practice, which predominantly address the endothelial and vascular dysfunctions associated with the condition. Nevertheless, these interventions simply delay progression of the disease rather than offer a cure and many patients ultimately exacerbate, requiring new therapeutic approaches. More recently, many novel targets that harness and optimize vasodilation and anti-proliferative effects have been investigated and validated in animal models of PH, including the modulation of BMP signaling.

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) was the first type of PH to spark the interest in defining a closer relationship between BMP signaling and vascular diseases. Development of PAH arises from vascular remodeling, which involves increased proliferation of vascular muscle cells (VSMCs) and extracellular matrix deposition in the vessels, leading to a decrease in lumen diameter and reduced capacity for vasodilation. These results in increased pulmonary artery pressure and, consequently, sustained pulmonary hypertension. Interestingly, it has been revealed that more than 70% of all familial (hereditary) cases of PAH inherit mutations at the BMPR-II gene (89–92), whereas up to 26% of the sporadic (non-hereditary) cases of PAH have been identified to also have mutations in BMPR-II (93–95). Surprisingly, patients developing PAH after exposure to appetite suppressants fenfluramine and dexfenfluramine also carry BMPR-II mutations (96). These mutations are likely to cause loss of function and/or dominant-negative effects, but there is no clear consensus as to how BMPR-II signaling affects the pulmonary vasculature (97). One hypothesis is that mutations in the cytoplasmic domain of BMPR-II may hinder its interaction with LIM kinase-1 (LIMK-1), which results in constitutive activation of cofilin, an actin depolymerizing factor (43, 94, 98). Various manipulations of BMPR-II expression in mice have provided insights into the mechanisms by which BMPR-II mutations may give rise to pulmonary vascular disease in PAH. Numerous studies suggest that abnormal BMP signaling associated with BMPR-II mutations in patients with PAH results in at least one or a combination of the following events: a shift from contractile to synthetic phenotype of VSMCs, aberrant vascular cell proliferation and apoptosis, changes in expression of actin organization-related genes that may be related to focal adhesions, alterations in inflammationtory cell and cytokine recruitment, and increased collagen and matrix, as well as pulmonary vascular responses to different stimulants (99–103). It appears that normal function of BMPR-II in adult animals is to assist in injury repair process, where impaired ability to terminate the repair process is due to mutations in BMPR-II results in PAH (103).

Although mutations in BMPR-II or dysregulation of the BMP signaling pathway may predispose an individual to PAH, the clinical challenge is to determine whether these new discoveries can be exploited for therapies. Based on emerging understanding of the genetic basis of PAH, various genes and delivery systems have been shown to ameliorate the progression of PAH in animal models. Gene delivery of BMPR-II has achieved significant improvements in PAH animal models, which is encouraging for the development of this technology for human applications (104, 105). Moreover, merely targeting the BMP signaling pathway alone may not be an efficient therapeutic approach. BMP signaling alone is insufficient to initiate the disease process without additional complications required for the pathogenesis of PAH (89, 106). Thus, up-and-coming approaches look forward to synergistic increase in efficiency through combinations of treatments that target multiple pathways (107).

CANCER

Outcome of BMP signaling is highly contextual throughout development, across different tissues, and thus in cancer. While the TGF-beta molecules represent a well established double- edged sword in carcinogenesis as known as tumor-suppressors in early stages but tumor-promoters in late stages of tumor progression, our current knowledge of BMPs in cancer is far from being clear (108, 109). There is not enough in vitro and in vivo data that leads to firm conclusions (110–112). Despite in vitro and in vivo studies linking BMPs to human osteosarcomas, there are no definite pro- or anti-carcinogenic BMPs in the general oncogenic process, and no straightforward mechanism of BMP dysregulation in carcinogenesis has yet been proposed. Most studies to date report that BMP-2, -4 and -7 are over-expressed in various cancers (110). However, changes in gene expression, epigenetic alterations and mutations in genes related to BMPs appear to be mostly a characteristic of a certain type of cell or tissue, not necessarily any direct nor indirect cause of carcinogenesis (110). In terms of their effects on one of the hallmarks of cancer - proliferation, even the same BMPs are described as both growth-stimulators (113–115) and growth-inhibitors (116–120), which likely reflects their complex interactions in developmental processes. Similarly, most of the cancer or anti-cancer effects of BMP signaling seem to depend on dosage, type of cell or tissue and the tumor microenvironment, which can shift a delicate balance between opposing properties of BMPs. Despite the lack of consistent reports of their roles in some events of human cancer development, closer relationships exist between BMPs and various features of carcinogenesis including angiogenesis, metastasis and cancer stem cells.

Angiogenesis

Growth of a tumor requires sustenance in the form of oxygen and nutrients via blood, as well as evacuation of metabolic wastes and carbon dioxide (121). Hence, tumors adopt angiogenesis as a survival mechanism to address these needs and pathological angiogenesis is known as one of the hallmarks of cancer (122). The onset of angiogenesis can occur at any stage of tumor progression depending on the tumor type and microenvironment, as it is orchestrated by a network of various angiogenic factors, including BMPs and their inhibitors (123). In fact, angiogenesis is an active process during embryonic development and female reproductive cycling, most of which BMPs are heavily associated with. Angiogenesis is also re-activated during wound repair and several pathological conditions such as vascular malfunctions and cancer (124–126). The relationship between vascular diseases such as HHT and PAH and dysregulation of the BMP signaling components such as endoglin, ALK-1 and BMPR-II has already been mentioned above. In tumor angiogenesis, BMPs and related proteins either stimulate or inhibit functions of ECs and VSMCs in a context-dependent manner (108). However, the exact role of each BMP and how perturbed signaling may contribute to angiogenesis in cancer and tumor progression remain to be determined in detail (127–130).

BMP-2 and BMP-4 have generally been proposed to be angiogenic factors, promoting tube formation and neovascularization of melanoma cells in the micro-vascular network (110, 131), in human blood endothelial progenitor cells (132) and in lung tumors by associating with VEFG to stimulate angiogenesis (127, 133). As target genes of BMP signaling, myosin-X and cyclooxygenase 2 have been found to play a role in vascularization (134). BMP antagonists have been reported to act as anti-angiogenic factors during tumor angiogenesis. Noggin inhibits BMP-4 induction of BEGFR-2 in embryonic blood vessels (135), whereas Chordin also inhibits BMP-4-induced in vitro tube formation of human vascular endothelial cells and malignant melanoma cells (131). Alternatively, BMP-9 and BMP-10 has been identified as the sole physiological ligands of the endothelial receptor ALK-1 in association with BMPR-II, inhibiting bFGF-stimulated proliferation and migration of bovine aortic endothelial cells, as well as preventing angiogenesis induced by VEGF (136, 137). In this view, BMP-9 appears to be a promising target for inhibiting or controlling tumor angiogenesis. However in some other mouse-model studies, inhibition of ALK-1 function impairs VEFG-induced angiogenesis and cancer progression (138). Moreover, a soluble chimeric protein (ALK-1-Fc) that selectively inhibits BMP-9 and BMP-10 mediated Id-1 expression in human umbilical vein endothelial cells has been shown to inhibit cord formation by these cells on Matrigel (139). ALK-1- Fc also reduced VEGF, FGF and BMP-mediated vessel formation, while also inhibiting the growth of B16 melanoma explants in chick chorioallantoic membrane assays (140). In the same study, MCF7 mammary adenocarcinoma grafts in mice treated with ALK-1-Fc also showed reduced tumor burden, which supports the effectiveness of ALK-1-Fc proteins as anti-angiogenic agents capable of inhibiting vascularization. The process of angiogenesis is very complex and relatively poorly understood. Other contributing factors, aside from the involvement of the BMPs, are likely to be the basis for such conflicting reports.

Metastasis

As carcinoma progress to higher pathological grades of malignancy, cancer cells typically develop changes in their morphology and adhesiveness to other cells and to the extracellular matrix (ECM), resulting in local invasion and distant metastasis. Tumors are believed to usurp processes involved in normal developmental programs and wound healing, such as epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT), tissue specific morphogenesis and cellular motility to create a complex microenvironment that sustains its survival and enable invasion. EMT is a normal embryonic process that facilitates cellular migration in gastrulation and tissue patterning (141), which have also been implicated to increase invasive and metastatic potential of cancerous cells in colonizing distant organs. Metastatic cancer cells acquire abilities to invade, to resist apoptosis, and to disseminate through EMT, capable of moving from one organ system to another via blood stream or lymphatic system (142–146).

Several studies support that BMP signaling confers various tumor cells with migratory and invasive properties (147). BMP signaling has been shown to induce EMT in normal and cancerous cell types (148, 149). Consistently, BMP-2 and BMP-4 are shown to enhance motility and invasiveness of prostate cancer cell lines (150), while functional overexpression of BMP-2 in breast cancer cells promotes invasion and ultimately induce tumor growth (151). Stable expression of a dominant-negative BMP receptor inhibited the ability of breast cancer cells to form bone metastasis (152). Moreover, orthotropic implant of tumors with scaffolds coupled with BMP-2, seeded with bone marrow stromal cells promoted metastatic spread of breast cancer cells (153). BMP-4 over-expressing colon cancer cell line displays resistance to serum starvation-induced apoptosis and increased motility and invasion activities, which are inhibited by Noggin (154). BMP-2 enhances migration and invasion of gastric cancer cells by activating the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) pathway (155). In primary human epithelial ovarian cancer, BMP-4 signaling changes cellular morphology and enhances adhesion, motility and invasion of the cancer cells (149). Exogenous BMP-4 treatment upregulates EMT markers such as SNAIL and SLUG while downregulating E-cadherin, a key cell-to-cell adhesion molecule, loss of which is the best characterized alteration involved in potentiating metastasis. Additionally, the network of alpha smooth muscle actin changes in response to BMP-4 to resemble a mesenchymal cell type (149).

BMP pathway has been shown to promote organ-specific metastasis to the bone particularly in advanced breast and prostate adenocarcinomas, which are the most prevalent cancers in women and men (156–158), respectively. Prostate and breast cancer cells are likely to be predestined to colonize the bone from primary tumor formation even before dissemination, as skeletal metastasis is particularly high in prostate and breast cancer patients: about 75% of prostate cancer and 70% of breast cancer patients have evidence of metastatic bone diseases (159–162). The spine is the most common site of tumor metastasis to bone, presenting significant morbidity to patients (157, 163). Bone metastasis is a devastating complication of these cancers, directly responsible for debilitating bone fractures, severe pain, hypercalcemia, spinal cord nerve compression and consequent paralysis (164, 165). Metastatic tumors drive bone destruction by disrupting a balance of bone homeostasis maintained by osteoblasts, the cells responsible for producing new bone matrix, and osteoclasts, the cells responsible for breaking down the bone matrix (166–168).

Preferential factors for cancer cells to metastasize to bones require sequential or simultaneous interactions among cells, growth factors, cytokines, receptors and the bone (169, 170). First, BMPs appear to select the most invasive tumor cells by stimulating the progenitor cells through an autocrine signaling pathway (171). For example in osteotropic prostate cancer cells, nuclear factor (NF)-kappa B uses PI3K/Akt pathway to activate BMP-2 signaling, which upregulates downstream BMP-2 target genes such as osteopontin, osteocalcin and collagen IA1, implying a predisposition of bone-like features (172). Both osteotropic prostate and breast cancer cells try to resemble osteoblasts by expressing bone matrix proteins as well as alkaline phosphatase-ensuing in osteomimicry which enables higher chances of survival and invasion into the bone tissue (173). Next, BMPs secreted by the tumor cells signal in a paracrine manner to create a reactive stroma through the activation of tumor-associated myofibroblasts, which are known enhancers of tumor cell growth and metastasis (174). Paracrine signaling also influences the bone microenvironment, resulting in a crosstalk between tumor cells and the bone that creates new “pre-neoplastic” niches in the bone for colonization (147, 164, 175). The BMPs produced from the bone may act as chemoattractants, assisting cell detachment by recruiting highly metastatic cells that express the BMP receptors (174). Chemoattractant activity of BMP-2 at a range of 12.5–50 nM has been demonstrated to increase migration of breast cancer cells towards a BMP-2 source in comparison to untreated cells (151). BMP-4 is also one of several factors that increase adhesion of prostate cancer cells to the endothelium of bone marrow (176). Such crosstalk between tumor cells and the bone microenvironment involving BMP signaling seems to generate bone metastasis. Since BMPs are potent regulators of bone morphogenesis, there is an increasing interest to investigate BMPs and their roles in bone metastasis. Therefore, better understanding molecular mechanisms underlying bone metastases will help to develop BMPs and its signaling molecules as new therapeutic targets for better and prolonged life expectation for patients with bone metastases.

Cancer stem cells

BMPs have extensive roles in regulating the biology of stem cells and guiding them to take part in embryonic development/organogenesis and tissue regeneration (177). Disruption of a fine balance between self-renewal and differentiation of stem cells leads to loss of control in terms of cell growth and proliferation that may result in cancer. In fact, stem cells already share characteristics of immortality, pluripotency, EMT plasticity and loss of contact inhibition with cancer cells. Hence, it is not surprising that BMPs also play pivotal roles in the maintenance and differentiation of cancer stem cells (CSCs). CSCs constitute a cellular subtype within tumors, which is thought to be the origin of tumors and their malignancies. CSCs, like normal stem cells, are believed to initiate tumorgenesis, and drive its growth, invasion and recurrence even after treatments (178, 179). Many patients are believed to respond to clinical treatments with limited effectiveness due to the presence of CSCs. The induction of developmental pathways in the midst of tumor-stromal interactions conceivably promotes an embryonic-like microenvironment that can provide a more welcoming niche for tumor cells to invade. Recent evidences have highlighted the involvement of CSCs in various types of tumors, linking EMT features with those of CSCs in particular (180).

Stem-cell signaling network is composed of cross-talk among overlapping signals between developmental pathways including WNT, FGF, Notch, Hedgehog, TGF-β, and BMP signaling cascades (181, 182). These pathways maintain pluripotent stem cells as well as CSCs by synergistically inducing EMT regulators, such as Snail (SNAI1), Slug (SNAI2), TWIST and ZEB2 (SIP1) at the tumor-stromal microenvironment (183). CSCs acquire more malignant phenotype through accumulation of additional genetic and epigenetic alterations (184). Recently, there have been major advances in understanding the role of BMP signaling in CSCs. However, the underlying mechanisms and processes are poorly understood and the oncogenic mechanisms vary with tumor type, the state of the disease as well as interaction with the tumor microenvironment. For instance, BMP-4 has been demonstrated to induce EMT and acquisition of stem cell-like phenotypes in oral squamous cell carcinoma (179), whereas the same molecule has been shown to be a promising therapeutic agent against CSCs in advanced colorectal tumors by promoting terminal differentiation, apoptosis and chemosensitization of colorectal CSCs (185). Therefore, the putative relationships warrant further investigations to prove more definitive roles of BMPs in the process of tumorigenesis with an emphasis on how aberrant activation of BMP signaling pathways connects the early events with the late events of cancer progression.

Exhaustive research activities are devoted to identifying drugs that interfere with oncogenic signaling by the aforementioned developmental pathways. Like BMPs, the secretion of Hedgehog (Hh) ligands within the tumor-stromal interaction has been shown to promote primary tumor growth (186). Recently, promising clinical data of a compound that disrupts the Hh pathway, GDC-0449 implicates that targeted therapy of developmental signaling pathways has potential for future anti-cancer therapies (187). Dorsomorphin (LDN-193189) is a selective small molecule inhibitor of BMP signaling pathway which specifically blocks ALK1, 2, 3 and 6 signaling through Smad1, 5 and 8 (188). It would be interesting to see how this small molecule influences tumor progression. In 2008, BMP-9 was patented as an anti-cancer therapeutic agent for regulating breast and prostate cancers on the basis of promoting apoptosis of prostate cancers (189, 190). For the time being, recombinant human (rh) BMP-2 and BMP-7 are clinically available for spinal fusions and long bone non-unions. In the meantime, the prevalence of BMP usage has been on the rise with at least 85% of procedures being off-label applications (191). The lack of sufficient knowledge of implications of BMPs in tumoregenesis has potential complications concerning those inpatient procedures. On the other hand, these BMPs would be of particular value in enhancing posterolateral fusion as well as in cages used for anterior reconstruction in patients who undergo routine radiation therapies for tumoregenic lesions in the spine (192). At this time, no reviews and studies report any adverse carcinogenic events in patients who underwent operations using either BMP-2 or BMP-7 (193–195). However, the lack of reported cases may be due to the relatively recent introduction of BMPs to clinical use and extra precautions must be made in determining appropriate dosage and length of retention time in the body.

PERSPECTIVES

Although much remains to be understood about the complexity of BMP signaling in metabolic malfunctions, vascular diseases and cancer, there is emerging evidence from a variety of systems that BMPs possess immense therapeutic potentials. At present, human BMPs are mass produced for clinical applications by recombinant technology and such recombinant human BMPs (rhBMPs) of BMP-2 and BMP-7 are currently used for spinal fusion, fracture healing and dental tissue engineering (196, 197). More recently, transplantation of rhBMPs with autologous stem-cells has also emerged as a promising technique in tissue engineering for the regeneration of various body parts (198). Furthermore, ex vivo rhBMP-conditioned cell therapy can be an effective alternative. The approach is theoretically recalcitrant to immunogenic complications, which opens the therapeutic strategy to a wider range of new protein-engineered synthetic BMP ligands. However, clinically effective doses of such rhBMPs (several mg) are much higher than their physiological doses (1–2 ug/kg of bone) (199, 200). Large-scale production still remains costly due to multiple preparation and purification processes and the need for large quantities of rhBMPs leads to higher costs (171). High concentrations also results in increased safety risks due to inflammation, oedema and heterotopic bone formations (201).

In order to address such problems, various genetic engineering approaches are also being explored to design second-generation BMPs. These engineered BMPs seek to acquire improved bioactivity through increased solubility, stability and affinity to receptors, decreased sensitivity to natural BMP inhibitors and better immunogenicity profile (202, 203). Shorter peptides of known active epitopes of BMPs that act just as full-length BMPs are also developed in an effort to reduce production costs (204, 205). Controlling the release of high concentrations of rhBMPs over a prolonged period of time is an other major problem for drug delivery. Carriers and scaffolds made of various materials such as collagen sponge, polymer microspheres and lipid-based microtubes have been shown to increase retention time of implanted rhBMPs to overcome short half-life and rapid clearance of the proteins in vivo (206–209). Gene therapy is a less expensive method of delivering BMPs to their disease sites in a well-controlled manner (171, 210, 211). Yet, gene therapy has a potential to risk elevated immune response following the use of adeno-, retro- and lentiviruses used to deliver DNA or RNA in gene therapies.

Clinical potentials of next-generation therapeutics such as engineered BMPs (203) and ex vivo-conditioned cell therapies offer innovative prospects. These new clinical strategies need to overcome various fundamental limitations such as cost, delivery and possible immunogenic responses. Despite these technical barriers, the emerging future of new biomedical therapeutics targeting BMP signaling is rapidly approaching and promises to be an exciting one.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the WCU program (Korea) and IFEZ (Incheon, Korea).

REFERENCES

- 1.Wagner DO, Sieber C, Bhushan R, Borgermann JH, Graf D, Knaus P. BMPs: from bone to body morphogenetic proteins. Sci. Signal. 2010;3:mr1. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.3107mr1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reddi AH. BMPs: from bone morphogenetic proteins to body morphogenetic proteins. Cytokine. Growth. Factor. Rev. 2005;16:249–250. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Satterfield MC, Wu G. Brown adipose tissue growth and development: significance and nutritional regulation. Front. Biosci. 2011;16:1589–1608. doi: 10.2741/3807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kopelman PG. Obesity as a medical problem. Nature. 2000;404:635–643. doi: 10.1038/35007508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hsu IR, Kim SP, Kabir M, Bergman RN. Metabolic syndrome, hyperinsulinemia, and cancer. Am J. Clin. Nutr. 2007;86:s867–s871. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/86.3.867S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Craft S. Insulin resistance and Alzheimer's disease pathogenesis: potential mechanisms and implications for treatment. Curr. Alzheimer. Res. 2007;4:147–152. doi: 10.2174/156720507780362137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cornier MA, Dabelea D, Hernandez TL, Lindstrom RC, Steig AJ, Stob NR, Van Pelt RE, Wang H, Eckel RH. The metabolic syndrome. Endocr. Rev. 2008;29:777–822. doi: 10.1210/er.2008-0024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hammond RA, Levine R. The economic impact of obesity in the United States. Diabetes. Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2010;3:285–295. doi: 10.2147/DMSOTT.S7384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zamani N, Brown CW. Emerging roles for the transforming growth factor-{beta} superfamily in regulating adiposity and energy expenditure. Endocr. Rev. 2011;32:387–403. doi: 10.1210/er.2010-0018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Snow V, Barry P, Fitterman N, Qaseem A, Weiss K. Pharmacologic and surgical management of obesity in primary care: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann. Intern. Med. 2005;142:525–531. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-7-200504050-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Colman E. Anorectics on trial: a half century of federal regulation of prescription appetite suppressants. Ann. Intern. Med. 2005;143:380–385. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-5-200509060-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gesta S, Tseng YH, Kahn CR. Developmental origin of fat: tracking obesity to its source. Cell. 2007;131:242–256. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martinsson A. Hypertrophy and hyperplasia of human adipose tissue in obesity. Pol. Arch. Med. Wewn. 1969;42:481–486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shepherd PR, Gnudi L, Tozzo E, Yang H, Leach F, Kahn BB. Adipose cell hyperplasia and enhanced glucose disposal in transgenic mice overexpressing GLUT4 selectively in adipose tissue. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:22243–22246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Otto TC, Lane MD. Adipose development: from stem cell to adipocyte. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2005;40:229–242. doi: 10.1080/10409230591008189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tang QQ, Otto TC, Lane MD. Commitment of C3H10T1/2 pluripotent stem cells to the adipocyte lineage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004;101:9607–9611. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403100101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tseng YH, Kokkotou E, Schulz TJ, Huang TL, Winnay JN, Taniguchi CM, Tran TT, Suzuki R, Espinoza DO, Yamamoto Y, Ahrens MJ, Dudley AT, Norris AW, Kulkarni RN, Kahn CR. New role of bone morphogenetic protein 7 in brown adipogenesis and energy expenditure. Nature. 2008;454:1000–1004. doi: 10.1038/nature07221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bowers RR, Kim JW, Otto TC, Lane MD. Stable stem cell commitment to the adipocyte lineage by inhibition of DNA methylation: role of the BMP-4 gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006;103:13022–13027. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605789103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dani C, Smith AG, Dessolin S, Leroy P, Staccini L, Villageois P, Darimont C, Ailhaud G. Differentiation of embryonic stem cells into adipocytes in vitro. J. Cell. Sci. 1997;110(Pt 11):1279–1285. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.11.1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bowers RR, Lane MD. A role for bone morphogenetic protein-4 in adipocyte development. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:385–389. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.4.3804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ji X, Chen D, Xu C, Harris SE, Mundy GR, Yoneda T. Patterns of gene expression associated with BMP-2-induced osteoblast and adipocyte differentiation of mesenchymal progenitor cell 3T3-F442A. J. Bone Miner. Metab. 2000;18:132–139. doi: 10.1007/s007740050103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sottile V, Seuwen K. Bone morphogenetic protein-2 stimulates adipogenic differentiation of mesenchymal precursor cells in synergy with BRL 49653 (rosiglitazone) FEBS Lett. 2000;475:201–204. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01655-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hata K, Nishimura R, Ikeda F, Yamashita K, Matsubara T, Nokubi T, Yoneda T. Differential roles of Smad1 and p38 kinase in regulation of peroxisome proliferator-activating receptor gamma during bone morphogenetic protein 2-induced adipogenesis. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2003;14:545–555. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-06-0356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jin W, Takagi T, Kanesashi SN, Kurahashi T, Nomura T, Harada J, Ishii S. Schnurri-2 controls BMP-dependent adipogenesis via interaction with Smad proteins. Dev. Cell. 2006;10:461–471. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen D, Ji X, Harris MA, Feng JQ, Karsenty G, Celeste AJ, Rosen V, Mundy GR, Harris SE. Differential roles for bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) receptor type IB and IA in differentiation and specification of mesenchymal precursor cells to osteoblast and adipocyte lineages. J. Cell. Biol. 1998;142:295–305. doi: 10.1083/jcb.142.1.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sebald W, Nickel J, Zhang JL, Mueller TD. Molecular recognition in bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)/receptor interaction. Biol. Chem. 2004;385:697–710. doi: 10.1515/BC.2004.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schulz TJ, Tseng YH. Emerging role of bone morphogenetic proteins in adipogenesis and energy metabolism. Cytokine. Growth. Factor. Rev. 2009;20:523–531. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2009.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bottcher Y, Unbehauen H, Kloting N, Ruschke K, Korner A, Schleinitz D, Tonjes A, Enigk B, Wolf S, Dietrich K, Koriath M, Scholz GH, Tseng YH, Dietrich A, Schon MR, Kiess W, Stumvoll M, Bluher M, Kovacs P. Adipose tissue expression and genetic variants of the bone morphogenetic protein receptor 1A gene (BMPR1A) are associated with human obesity. Diabetes. 2009;58:2119–2128. doi: 10.2337/db08-1458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu Y, Zhou S, Smas CM. Downregulated expression of the secreted glycoprotein follistatin-like 1 (Fstl1) is a robust hallmark of preadipocyte to adipocyte conversion. Mech. Dev. 2010;127:183–202. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Allen DL, Cleary AS, Speaker KJ, Lindsay SF, Uyenishi J, Reed JM, Madden MC, Mehan RS. Myostatin, activin receptor IIb, follistatin-like-3 gene expression are altered in adipose tissue and skeletal muscle of obese mice. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2008;294:E918–E927. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00798.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen TL, Shen WJ, Kraemer FB. Human BMP-7/OP-1 induces the growth and differentiation of adipocytes and osteoblasts in bone marrow stromal cell cultures. J. Cell Biochem. 2001;82:187–199. doi: 10.1002/jcb.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Neumann K, Endres M, Ringe J, Flath B, Manz R, Haupl T, Sittinger M, Kaps C. BMP7 promotes adipogenic but not osteo-/chondrogenic differentiation of adult human bone marrow-derived stem cells in high-density micro-mass culture. J. Cell Biochem. 2007;102:626–637. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Richard D, Carpentier AC, Dore G, Ouellet V, Picard F. Determinants of brown adipocyte development and thermogenesis. Int. J. Obes (Lond) 2010;34(Suppl 2):S59–S66. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2010.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cypess AM, Lehman S, Williams G, Tal I, Rodman D, Goldfine AB, Kuo FC, Palmer EL, Tseng YH, Doria A, Kolodny GM, Kahn CR. Identification and importance of brown adipose tissue in adult humans. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;360:1509–1517. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Virtanen KA, Lidell ME, Orava J, Heglind M, Westergren R, Niemi T, Taittonen M, Laine J, Savisto NJ, Enerback S, Nuutila P. Functional brown adipose tissue in healthy adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;360:1518–1525. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saito M, Okamatsu-Ogura Y, Matsushita M, Watanabe K, Yoneshiro T, Nio-Kobayashi J, Iwanaga T, Miyagawa M, Kameya T, Nakada K, Kawai Y, Tsujisaki M. High incidence of metabolically active brown adipose tissue in healthy adult humans: effects of cold exposure and adiposity. Diabetes. 2009;58:1526–1531. doi: 10.2337/db09-0530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zingaretti MC, Crosta F, Vitali A, Guerrieri M, Frontini A, Cannon B, Nedergaard J, Cinti S. The presence of UCP1 demonstrates that metabolically active adipose tissue in the neck of adult humans truly represents brown adipose tissue. FASEB. J. 2009;23:3113–3120. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-133546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harris MI. Diabetes in America: epidemiology and scope of the problem. Diabetes Care. 1998;21(Suppl 3):C11–C14. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.3.c11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Taylor SI. Deconstructing type 2 diabetes. Cell. 1999;97:9–12. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80709-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saltiel AR. New perspectives into the molecular pathogenesis and treatment of type 2 diabetes. Cell. 2001;104:517–529. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00239-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen JW, Christiansen JS, Lauritzen T. Limitations to subcutaneous insulin administration in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2003;5:223–233. doi: 10.1046/j.1463-1326.2003.00266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen W, Salojin KV, Mi QS, Grattan M, Meagher TC, Zucker P, Delovitch TL. Insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-I/IGF-binding protein-3 complex: therapeutic efficacy and mechanism of protection against type 1 diabetes. Endocrinology. 2004;145:627–638. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tobin JF, Celeste AJ. Bone morphogenetic proteins and growth differentiation factors as drug targets in cardiovascular and metabolic disease. Drug. Discov Today. 2006;11:405–411. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2006.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miller AF, Harvey SA, Thies RS, Olson MS. Bone morphogenetic protein-9. An autocrine/paracrine cytokine in the liver. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:17937–17945. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.24.17937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Caperuto LC, Anhe GF, Cambiaghi TD, Akamine EH, do Carmo Buonfiglio D, Cipolla-Neto J, Curi R, Bordin S. Modulation of bone morphogenetic protein-9 expression and processing by insulin, glucose, and glucocorticoids: possible candidate for hepatic insulin-sensitizing substance. Endocrinology. 2008;149:6326–6335. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lautt WW. The HISS story overview: a novel hepatic neurohumoral regulation of peripheral insulin sensitivity in health and diabetes. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1999;77:553–562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bidart M, Ricard N, Levet S, Samson M, Mallet C, David L, Subileau M, Tillet E, Feige JJ, Bailly S. BMP9 is produced by hepatocytes and circulates mainly in an active mature form complexed to its prodomain. Cell. Mol. Life. Sci. 2011 Jun 28; doi: 10.1007/s00018-011-0751-1. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Anhe FF, Lellis-Santos C, Leite AR, Hirabara SM, Boschero AC, Curi R, Anhe GF, Bordin S. Smad5 regulates Akt2 expression and insulin- induced glucose uptake in L6 myotubes. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2010;319:30–38. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Song JJ, Celeste AJ, Kong FM, Jirtle RL, Rosen V, Thies RS. Bone morphogenetic protein-9 binds to liver cells and stimulates proliferation. Endocrinology. 1995;136:4293–4297. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.10.7664647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen C, Grzegorzewski KJ, Barash S, Zhao Q, Schneider H, Wang Q, Singh M, Pukac L, Bell AC, Duan R, Coleman T, Duttaroy A, Cheng S, Hirsch J, Zhang L, Lazard Y, Fischer C, Barber MC, Ma ZD, Zhang YQ, Reavey P, Zhong L, Teng B, Sanyal I, Ruben SM, Blondel O, Birse CE. An integrated functional genomics screening program reveals a role for BMP-9 in glucose homeostasis. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003;21:294–301. doi: 10.1038/nbt795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang J, Greene SB, Martin JF. BMP signaling in congenital heart disease: new developments and future directions. Birth. Defects. ResAClin. Mol. Teratol. 2011;91:441–448. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lowery JW, de Caestecker MP. BMP signaling in vascular development and disease. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2010;21:287–298. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2010.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen NX, Moe SM. Arterial calcification in diabetes. Curr. Diab. Rep. 2003;3:28–32. doi: 10.1007/s11892-003-0049-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu Y, Shanahan CM. Signalling pathways and vascular calcification. Front. Biosci. 2011;16:1302–1314. doi: 10.2741/3790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rennenberg RJ, Schurgers LJ, Kroon AA, Stehouwer CD. Arterial calcifications. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2010;14:2203–2210. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01139.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Corriere MA, Rogers CM, Eliason JL, Faulk J, Kume T, Hogan BL, Guzman RJ. Endothelial Bmp4 is induced during arterial remodeling: effects on smooth muscle cell migration and proliferation. J. Surg. Res. 2008;145:142–149. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2007.03.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bostrom K, Watson KE, Horn S, Wortham C, Herman IM, Demer LL. Bone morphogenetic protein expression in human atherosclerotic lesions. J. Clin. Invest. 1993;91:1800–1809. doi: 10.1172/JCI116391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sorescu GP, Sykes M, Weiss D, Platt MO, Saha A, Hwang J, Boyd N, Boo YC, Vega JD, Taylor WR, Jo H. Bone morphogenic protein 4 produced in endothelial cells by oscillatory shear stress stimulates an inflammatory response. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:31128–31135. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300703200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cheng SL, Shao JS, Charlton-Kachigian N, Loewy AP, Towler DA. MSX2 promotes osteogenesis and suppresses adipogenic differentiation of multipotent mesenchymal progenitors. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:45969–45977. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306972200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tobin MJ. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, pollution, pulmonary vascular disease, transplantation, pleural disease, and lung cancer in AJRCCM 2002. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care. Med. 2003;167:356–370. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2212003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zebboudj AF, Imura M, Bostrom K. Matrix GLA protein, a regulatory protein for bone morphogenetic protein-2. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:4388–4394. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109683200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yao Y, Zebboudj AF, Shao E, Perez M, Bostrom K. Regulation of bone morphogenetic protein-4 by matrix GLA protein in vascular endothelial cells involves activin-like kinase receptor 1. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:33921–33930. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604239200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dhore CR, Cleutjens JP, Lutgens E, Cleutjens KB, Geusens PP, Kitslaar PJ, Tordoir JH, Spronk HM, Vermeer C, Daemen MJ. Differential expression of bone matrix regulatory proteins in human atherosclerotic plaques. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2001;21:1998–2003. doi: 10.1161/hq1201.100229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Luo G, Ducy P, McKee MD, Pinero GJ, Loyer E, Behringer RR, Karsenty G. Spontaneous calcification of arteries and cartilage in mice lacking matrix GLA protein. Nature. 1997;386:78–81. doi: 10.1038/386078a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sweatt A, Sane DC, Hutson SM, Wallin R. Matrix Gla protein (MGP) and bone morphogenetic protein-2 in aortic calcified lesions of aging rats. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2003;1:178–185. doi: 10.1046/j.1538-7836.2003.00023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hur DJ, Raymond GV, Kahler SG, Riegert-Johnson DL, Cohen BA, Boyadjiev SA. A novel MGP mutation in a consanguineous family: review of the clinical and molecular characteristics of Keutel syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2005;135:36–40. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hruska KA, Guo G, Wozniak M, Martin D, Miller S, Liapis H, Loveday K, Klahr S, Sampath TK, Morrissey J. Osteogenic protein-1 prevents renal fibrogenesis associated with ureteral obstruction. Am. J. Physiol. Renal. Physiol. 2000;279:F130–F143. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2000.279.1.F130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vukicevic S, Basic V, Rogic D, Basic N, Shih MS, Shepard A, Jin D, Dattatreyamurty B, Jones W, Dorai H, Ryan S, Griffiths D, Maliakal J, Jelic M, Pastorcic M, Stavljenic A, Sampath TK. Osteogenic protein-1 (bone morphogenetic protein-7) reduces severity of injury after ischemic acute renal failure in rat. J. Clin. Invest. 1998;102:202–214. doi: 10.1172/JCI2237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Simic P, Vukicevic S. Bone morphogenetic proteins in development and homeostasis of kidney. Cytokine. Growth. Factor. Rev. 2005;16:299–308. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zeisberg M, Hanai J, Sugimoto H, Mammoto T, Charytan D, Strutz F, Kalluri R. BMP-7 counteracts TGF-beta1-induced epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and reverses chronic renal injury. Nat. Med. 2003;9:964–968. doi: 10.1038/nm888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Davies MR, Lund RJ, Hruska KA. BMP-7 is an efficacious treatment of vascular calcification in a murine model of atherosclerosis and chronic renal failure. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2003;14:1559–1567. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000068404.57780.dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Li T, Surendran K, Zawaideh MA, Mathew S, Hruska KA. Bone morphogenetic protein 7: a novel treatment for chronic renal and bone disease. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2004;13:417–422. doi: 10.1097/01.mnh.0000133974.24935.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.McAllister KA, Grogg KM, Johnson DW, Gallione CJ, Baldwin MA, Jackson CE, Helmbold EA, Markel DS, McKinnon WC, Murrell JMc, Cormick MK, Pericak-Vance MA, Heutink P, Oostra BA, Haitjema T, Westerman CJJ, Porteous ME, Guttmacher AE, Letarte M, Marchuk DA. Endoglin, a TGF-beta binding protein of endothelial cells, is the gene for hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia type 1. Nat. Genet. 1994;8:345–351. doi: 10.1038/ng1294-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Johnson DW, Berg JN, Baldwin MA, Gallione CJ, Marondel I, Yoon SJ, Stenzel TT, Speer M, Pericak-Vance MA, Diamond A, Guttmacher AE, Jackson CE, Attisano L, Kucherlapati R, Porteous ME, Marchuk DA. Mutations in the activin receptor-like kinase 1 gene in hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia type 2. Nat. Genet. 1996;13:189–195. doi: 10.1038/ng0696-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gallione CJ, Richards JA, Letteboer TG, Rushlow D, Prigoda NL, Leedom TP, Ganguly A, Castells A, Ploos van Amstel JK, Westermann CJ, Pyeritz RE, Marchuk DA. SMAD4 mutations found in unselected HHT patients. J. Med. Genet. 2006;43:793–797. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2006.041517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sabba C, Pasculli G, Lenato GM, Suppressa P, Lastella P, Memeo M, Dicuonzo F, Guant G. Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia: clinical features in ENG and ALK1 mutation carriers. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2007;5:1149–1157. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Oh SP, Seki T, Goss KA, Imamura T, Yi Y, Donahoe PK, Li L, Miyazono K, ten Dijke P, Kim S, Li E. Activin receptor-like kinase 1 modulates transforming growth factor-beta 1 signaling in the regulation of angiogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2000;97:2626–2631. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.6.2626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Urness LD, Sorensen LK, Li DY. Arteriovenous malformations in mice lacking activin receptor-like kinase-1. Nat. Genet. 2000;26:328–331. doi: 10.1038/81634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Roman BL, Pham VN, Lawson ND, Kulik M, Childs S, Lekven AC, Garrity DM, Moon RT, Fishman MC, Lechleider RJ, Weinstein BM. Disruption of acvrl1 increases endothelial cell number in zebrafish cranial vessels. Development. 2002;129:3009–3019. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.12.3009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Li DY, Sorensen LK, Brooke BS, Urness LD, Davis EC, Taylor DG, Boak BB, Wendel DP. Defective angiogenesis in mice lacking endoglin. Science. 1999;284:1534–1537. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5419.1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Liu D, Wang J, Kinzel B, Mueller M, Mao X, Valdez R, Liu Y, Li E. Dosage-dependent requirement of BMP type II receptor for maintenance of vascular integrity. Blood. 2007;110:1502–1510. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-11-058594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Arthur HM, Ure J, Smith AJ, Renforth G, Wilson DI, Torsney E, Charlton R, Parums DV, Jowett T, Marchuk DA, Burn J, Diamond AG. Endoglin, an ancillary TGFbeta receptor, is required for extraembryonic angiogenesis and plays a key role in heart development. Dev. Biol. 2000;217:42–53. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Srinivasan S, Hanes MA, Dickens T, Porteous ME, Oh SP, Hale LP, Marchuk DA. A mouse model for hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT) type 2. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2003;12:473–482. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Park SO, Lee YJ, Seki T, Hong KH, Fliess N, Jiang Z, Park A, Wu X, Kaartinen V, Roman BL, Oh SP. ALK5- and TGFBR2-independent role of ALK1 in the pathogenesis of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia type 2. Blood. 2008;111:633–642. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-107359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bourdeau A, Faughnan ME, Letarte M. Endoglin-deficient mice, a unique model to study hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Trends. Cardiovasc. Med. 2000;10:279–285. doi: 10.1016/s1050-1738(01)00062-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bourdeau A, Cymerman U, Paquet ME, Meschino W, McKinnon WC, Guttmacher AE, Becker L, Letarte M. Endoglin expression is reduced in normal vessels but still detectable in arteriovenous malformations of patients with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia type 1. Am. J. Pathol. 2000;156:911–923. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64960-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mitchell A, Adams LA, MacQuillan G, Tibballs J, vanden Driesen R, Delriviere L. Bevacizumab reverses need for liver transplantation in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Liver. Transpl. 2008;14:210–213. doi: 10.1002/lt.21417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Cruikshank RP, Chern BW. Bevacizumab and hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia. Med. J. Aust. 2011;194:324–325. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2011.tb02989.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Machado RD, Aldred MA, James V, Harrison RE, Patel B, Schwalbe EC, Gruenig E, Janssen B, Koehler R, Seeger W, Eickelberg O, Olschewski H, Elliott CG, Glissmeyer E, Carlquist J, Kim M, Torbicki A, Fijalkowska A, Szewczyk G, Parma J, Abramowicz MJ, Galie N, Morisaki H, Kyotani S, Nakanishi N, Morisaki T, Humbert M, Simonneau G, Sitbon O, Soubrier F, Coulet F, Morrell NW, Trembath RC. Mutations of the TGF-beta type II receptor BMPR2 in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Hum. Mutat. 2006;27:121–132. doi: 10.1002/humu.20285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Machado RD, Eickelberg O, Elliott CG, Geraci MW, Hanaoka M, Loyd JE, Newman JH, Phillips JA, 3rd, Soubrier F, Trembath RC, Chung WK. Genetics and genomics of pulmonary arterial hypertension. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2009;54:S32–S42. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lane KB, Machado RD, Pauciulo MW, Thomson JR, Phillips JA, 3rd, Loyd JE, Nichols WC, Trembath RC. Heterozygous germline mutations in BMPR2, encoding a TGF-beta receptor, cause familial primary pulmonary hypertension. Nat. Genet. 2000;26:81–84. doi: 10.1038/79226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Thomson JR, Machado RD, Pauciulo MW, Morgan NV, Humbert M, Elliott GC, Ward K, Yacoub M, Mikhail G, Rogers P, Newman J, Wheeler L, Higenbottam T, Gibbs JS, Egan J, Crozier A, Peacock A, Allcock R, Corris P, Loyd JE, Trembath RC, Nichols WC. Sporadic primary pulmonary hypertension is associated with germline mutations of the gene encoding BMPR-II, a receptor member of the TGF-beta family. J. Med. Genet. 2000;37:741–745. doi: 10.1136/jmg.37.10.741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Simonneau G, Galie N, Rubin LJ, Langleben D, Seeger W, Domenighetti G, Gibbs S, Lebrec D, Speich R, Beghetti M, Rich S, Fishman A. Clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2004;43:S5–S12. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Du L, Sullivan CC, Chu D, Cho AJ, Kido M, Wolf PL, Yuan JX, Deutsch R, Jamieson SW, Thistlethwaite PA. Signaling molecules in nonfamilial pulmonary hypertension. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348:500–509. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Atkinson C, Stewart S, Upton PD, Machado R, Thomson JR, Trembath RC, Morrell NW. Primary pulmonary hypertension is associated with reduced pulmonary vascular expression of type II bone morphogenetic protein receptor. Circulation. 2002;105:1672–1678. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000012754.72951.3d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Humbert M, Deng Z, Simonneau G, Barst RJ, Sitbon O, Wolf M, Cuervo N, Moore KJ, Hodge SE, Knowles JA, Morse JH. BMPR2 germline mutations in pulmonary hypertension associated with fenfluramine derivatives. Eur. Respir. J. 2002;20:518–523. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.01762002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lowery JW, Frump AL, Anderson L, DiCarlo GE, Jones MT, de Caestecker MP. ID family protein expression and regulation in hypoxic pulmonary hypertension. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2010;299:R1463–R1477. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00866.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Foletta VC, Lim MA, Soosairajah J, Kelly AP, Stanley EG, Shannon M, He W, Das S, Massague J, Bernard O. Direct signaling by the BMP type II receptor via the cytoskeletal regulator LIMK1. J. Cell. Biol. 2003;162:1089–1098. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200212060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Frank DB, Lowery J, Anderson L, Brink M, Reese J, de Caestecker M. Increased susceptibility to hypoxic pulmonary hypertension in Bmpr2 mutant mice is associated with endothelial dysfunction in the pulmonary vasculature. Am. J. Physiol. Lung. Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2008;294:L98–L109. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00034.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Hong KH, Lee YJ, Lee E, Park SO, Han C, Beppu H, Li E, Raizada MK, Bloch KD, Oh SP. Genetic ablation of the BMPR2 gene in pulmonary endothelium is sufficient to predispose to pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circulation. 2008;118:722–730. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.736801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Song Y, Coleman L, Shi J, Beppu H, Sato K, Walsh K, Loscalzo J, Zhang YY. Inflammation, endothelial injury, and persistent pulmonary hypertension in heterozygous BMPR2-mutant mice. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2008;295:H677–H690. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.91519.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Song Y, Jones JE, Beppu H, Keaney JF, Jr, Loscalzo J, Zhang YY. Increased susceptibility to pulmonary hypertension in heterozygous BMPR2-mutant mice. Circulation. 2005;112:553–562. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.492488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.West J. Cross talk between Smad, MAPK, and actin in the etiology of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2010;661:265–278. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-500-2_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Reynolds PN. Gene therapy for pulmonary hypertension: prospects and challenges. Expert. Opin. Biol. Ther. 2011;11:133–143. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2011.542139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Reynolds PN. Viruses in pharmaceutical research: pulmonary vascular disease. Mol. Pharm. 2011;8:56–64. doi: 10.1021/mp1003477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Yuan JX, Rubin LJ. Pathogenesis of pulmonary arterial hypertension: the need for multiple hits. Circulation. 2005;111:534–538. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000156326.48823.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Baliga RS, MacAllister RJ, Hobbs AJ. New perspectives for the treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2011;163:125–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.01164.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Pardali E, ten Dijke P. Transforming growth factor-beta signaling and tumor angiogenesis. Front Biosci. 2009;14:4848–4861. doi: 10.2741/3573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Massague J. TGFbeta in Cancer. Cell. 2008;134:215–230. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Singh A, Morris RJ. The Yin and Yang of bone morphogenetic proteins in cancer. Cytokine. Growth. Factor. Rev. 2010;21:299–313. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Wharton K, Derynck R. TGFbeta family signaling: novel insights in development and disease. Development. 2009;136:3691–3697. doi: 10.1242/dev.040584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Walsh DW, Godson C, Brazil DP, Martin F. Extracellular BMP-antagonist regulation in development and disease: tied up in knots. Trends. Cell Biol. 2010;20:244–256. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2010.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Kleeff J, Maruyama H, Ishiwata T, Sawhney H, Friess H, Buchler MW, Korc M. Bone morphogenetic protein 2 exerts diverse effects on cell growth in vitro and is expressed in human pancreatic cancer in vivo. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:1202–1216. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70024-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Herrera B, van Dinther M, Ten Dijke P, Inman GJ. Autocrine bone morphogenetic protein-9 signals through activin receptor-like kinase-2/Smad1/Smad4 to promote ovarian cancer cell proliferation. Cancer Res. 2009;69:9254–9262. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Alarmo EL, Parssinen J, Ketolainen JM, Savinainen K, Karhu R, Kallioniemi A. BMP7 influences proliferation, migration, and invasion of breast cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2009;275:35–43. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Arnold SF, Tims E, McGrath BE. Identification of bone morphogenetic proteins and their receptors in human breast cancer cell lines: importance of BMP2. Cytokine. 1999;11:1031–1037. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1999.0508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Ro TB, Holt RU, Brenne AT, Hjorth-Hansen H, Waage A, Hjertner O, Sundan A, Borset M. Bone morphogenetic protein-5,-6 and-7 inhibit growth and induce apoptosis in human myeloma cells. Oncogene. 2004;23:3024–3032. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Piccirillo SG, Reynolds BA, Zanetti N, Lamorte G, Binda E, Broggi G, Brem H, Olivi A, Dimeco F, Vescovi AL. Bone morphogenetic proteins inhibit the tumorigenic potential of human brain tumour-initiating cells. Nature. 2006;444:761–765. doi: 10.1038/nature05349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Du J, Yang S, Wang Z, Zhai C, Yuan W, Lei R, Zhang J, Zhu T. Bone morphogenetic protein 6 inhibit stress-induced breast cancer cells apoptosis via both Smad and p38 pathways. J. Cell. Biochem. 2008;103:1584–1597. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Johnsen IK, Kappler R, Auernhammer CJ, Beuschlein F. Bone morphogenetic proteins 2 and 5 are down-regulated in adrenocortical carcinoma and modulate adrenal cell proliferation and steroidogenesis. Cancer Res. 2009;69:5784–5792. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Quan GM, Choong PF. Anti-angiogenic therapy for osteosarcoma. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2006;25:707–713. doi: 10.1007/s10555-006-9031-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Bergers G, Benjamin LE. Tumorigenesis and the angiogenic switch. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2003;3:401–410. doi: 10.1038/nrc1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Carmeliet P. Angiogenesis in life, disease and medicine. Nature. 2005;438:932–936. doi: 10.1038/nature04478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Carmeliet P. VEGF as a key mediator of angiogenesis in cancer. Oncology (Williston Park) 2005;69(Suppl 3):4–10. doi: 10.1159/000088478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.David L, Feige JJ, Bailly S. Emerging role of bone morphogenetic proteins in angiogenesis. Cytokine. Growth. Factor Rev. 2009;20:203–212. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Langenfeld EM, Langenfeld J. Bone morphogenetic protein-2 stimulates angiogenesis in developing tumors. Mol. Cancer Res. 2004;2:141–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Valdimarsdottir G, Goumans MJ, Rosendahl A, Brugman M, Itoh S, Lebrin F, Sideras P, ten Dijke P. Stimulation of Id1 expression by bone morphogenetic protein is sufficient and necessary for bone morphogenetic protein-induced activation of endothelial cells. Circulation. 2002;106:2263–2270. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000033830.36431.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Raida M, Clement JH, Leek RD, Ameri K, Bicknell R, Niederwieser D, Harris AL. Bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP-2) and induction of tumor angiogenesis. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2005;131:741–750. doi: 10.1007/s00432-005-0024-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Peng H, Usas A, Olshanski A, Ho AM, Gearhart B, Cooper GM, Huard J. VEGF improves, whereas sFlt1 inhibits, BMP2-induced bone formation and bone healing through modulation of angiogenesis. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2005;20:2017–2027. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.050708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]