Abstract

The further characterization of the orphan GPCR GPR18 conducted by McHugh et al. in this issue of the British Journal of Pharmacology has generated a pharmacological profile that raises some interesting questions about the nomenclature of this receptor and may also prompt some questions about the pharmacological definition of the classical cannabinoid receptors, CB1 and CB2.

LINKED ARTICLES

This article is a commentary on McHugh et al., pp. 2414–2424 of this issue and is part of a themed section on Cannabinoids in Biology and Medicine. To view McHugh et al. visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01497.x. To view the other articles in this section visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/bph.2012.165.issue-8. To view Part I of Cannabinoids in Biology and Medicine visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/bph.2011.163.issue-7

Keywords: cannabinoid receptor, GPR18, anandamide, N-arachidonoylglycine, tetrahydrocannabinol, AM251

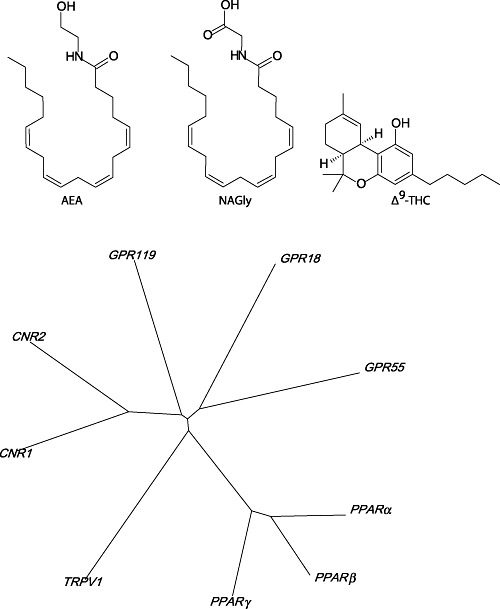

In this issue of the British Journal of Pharmacology, the second associated with a celebration of the 80th birthday of Raphael Mechoulam, Doug McHugh, Heather Bradshaw and colleagues describe their investigations into the orphan GPCR, GPR18 (McHugh et al., 2012). They observed that N-arachidonoylglycine (NAGly, an endogenous fatty acid: amino acid conjugate; see Figure 1A), Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC, the major psychoactive component of the cannabis plant; see Figure 1A) and anandamide (AEA, an endogenous cannabinoid agonist; see Figure 1A) function as ‘full’ agonists at GPR18 expressed heterologously in HEK293 cells, as measured by phosphorylation of ERK1/2, with that rank order of potency. This leads me to pose the question: what do we call GPR18 now?

Figure 1.

An evaluation of GPR18 pharmacology (A) and structure (B). The structures shown in (A) are of AEA, an endogenous cannabinoid; NAGly, the putative endogenous agonist for GPR18 receptors; and Δ9-THC, the archetypal natural cannabinoid from the Cannabis plant. An unrooted dendrogram in (B) illustrates sequence similarities for putative cannabinoid and cannabinoid-like receptors in man (conducted using ClustalX2).

The short answer to that question, of course, is that we wait for a decision from the appropriate Nomenclature Committee of IUPHAR – the Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology (http://www.iuphar.org/nciuphar.html). So what options are open to them? Guidance from NC-IUPHAR suggests naming the receptor after the endogenous ligand or group of ligands. Of the ligands examined for activity at recombinant GPR18, NAGly was the most potent in the current study (McHugh et al., 2012). Is GPR18, therefore, a NAGly (or potentially a NAGly1 or NAG1) receptor?

NAGly as an endogenous entity

GPR18 was initially cloned and deorphanized from a human T-cell line in a search for novel chemokine-like receptors (Kohno et al., 2006). Using the recombinant receptor, NAGly was observed to be an agonist, with 10 µM of this lipoamino acid evoking a rapid and transient elevation of intracellular calcium ions. Additionally, NAGly evoked a concentration-dependent, pertussis toxin-sensitive inhibition of cAMP formation, with a calculated IC50 value of 20 nM (Kohno et al., 2006), similar to its potency in the McHugh et al. study. NAGly has been reported to be ineffective as an agonist at either CB1 or CB2 cannabinoid receptors (Sheskin et al., 1997; Huang et al., 2001), despite a marked structural similarity to the endogenous cannabinoid anandamide (Figure 1A). Indeed, it has been suggested that NAGly biosynthesis might involve anandamide as a precursor, with oxidation at the terminal alcohol by cytochrome c (McCue et al., 2008) or alcohol dehydrogenase (Bradshaw et al., 2009). NAGly inhibits fatty acid amide hydrolase activity (Ghafouri et al., 2004) but not monoacylglycerol activity, suggesting selective impairment of amide endocannabinoid, but not glyceride endocannabinoid, hydrolysis (Ghafouri et al., 2004). It has also been suggested that NAGly is formed through the action of fatty acid amide hydrolase in ‘reverse mode’ (Bradshaw et al., 2009). NAGly is also a substrate for COX-2, producing prostaglandin conjugates of glycine (Prusakiewicz et al., 2002), although the relevance of this potential biotransformation is unclear.

Levels of NAGly in ex vivo tissues were initially observed to be highest in spinal cord and small intestine, with intermediate levels in brain and testes, and low levels in blood, spleen and heart (Huang et al., 2001). Further studies suggested that brain levels of NAGly were similar to those of AEA but appreciably lower than 2-arachidonoylglycerol a further endogenous cannabinoid agonist (Bradshaw et al., 2006). As yet, there are no reports demonstrating whether NAGly levels may be altered with pharmacological or pathological interventions.

Tissue distribution of GPR18

The original cloning of GPR18 suggested high levels of expression in man in testes and spleen (Gantz et al., 1997). An effect on immune function was suggested, with detectable levels of expression in the thymus, peripheral white blood cells and small intestine. Many other tissues appear to be devoid of GPR18 expression, including the brain, heart, lung, liver, kidney, pancreas, colon, skeletal muscle, ovary, placenta, prostate, adrenal medulla and cortex. In cultured cells, GPR18 expression has been identified in human lymphoid cells (Kohno et al., 2006), BV2 murine microglial cells (McHugh et al., 2010), metastatic melanoma (Qin et al., 2011) and now HEC-1B human endometrial cells (McHugh et al., 2012).

There appears, therefore, to be a slight disconnection between tissues expressing significant amounts of NAGly and the expression of the putative NAGly receptor, GPR18. Further work on the distribution of GPR18 and NAGly needs to be done to confirm co-localization (or not). Of course, it is quite conceivable that NAGly performs other functions apart from acting as a GPR18 agonist. NAGly was initially suggested to act as an agonist at GPR92, at the time another orphan receptor (Oh et al., 2008); however, a later study suggested that NAGly is a poor ligand at this receptor, while lysophosphatidic acid is a much more potent agonist (Williams et al., 2009). GPR92 has been re-named as the LPA5 receptor. Further suggested actions of NAGly include an inhibitory action at GlyT2/SLC6A5 glycine transporters (Wiles et al., 2006) and voltage-gated calcium channels (Barbara et al., 2009). So this may explain the discrepancy in distribution between agonist and receptor.

Is GPR18 a novel cannabinoid receptor?

McHugh et al. report that two cannabinoid agonists, AEA and THC, are full agonists at GPR18, while a further Cannabis-derived compound cannabidiol (CBD) is a low efficacy agonist (McHugh et al., 2012). Intriguingly, AEA is a partial agonist at CB1 cannabinoid receptors, as is THC (Pertwee et al., 2010). At CB2 cannabinoid receptors, both THC and AEA also have very low efficacy (Pertwee et al., 2010). CBD is a poor ligand at both CB1 and CB2 cannabinoid receptors (Pertwee et al., 2010). These data could be taken as evidence to suggest that GPR18 should be considered a third cannabinoid receptor, a suggestion considered premature only a year ago (Pertwee et al., 2010). Comparing primary sequences of putative cannabinoid receptors with CB1 and CB2 cannabinoid receptors suggests very little overlap in structure between the archetypal cannabinoid receptors and GPR18 (or indeed with GPR55, GPR119, TRPV1, PPARα, PPARβ and PPARγ, see Figure 1B).

As yet, there is a single report investigating the possible action of 2-arachidonoylglycerol at GPR18, where it was reported to be ineffective (Yin et al., 2009). In counterpoint, though, it should be noted that this report suggested that NAGly was also ineffective as a GPR18 agonist. What would make the suggestion that GPR18 is a further cannabinoid receptor more compelling would be a response evoked by a cannabinoid in vivo that could be shown to be mediated by GPR18, and not CB1 or CB2 cannabinoid receptors. Although a transgenic mouse model has yet to be described in which the gpr18 gene is disrupted, a double knockout of CB1 and CB2 receptors has been described, which might well be an attractive topic for future research involving GPR18. Another fruitful area of research would be to investigate whether changes in GPR18 expression or coupling result when the classical cannabinoid receptors are disrupted.

Furthermore, the antagonist action of CBD at GPR18 described by McHugh et al. (2012) may well cause a re-examination, if not re-evaluation, of the literature in which combinations of AEA and CBD or THC and CBD have been investigated. Additionally, McHugh et al. showed that the widely used CB1-selective antagonist AM251 was a very weak partial agonist at GPR18, with a calculated potency of approximately 100 µM. However, AM251 was able to evoke a concentration-dependent inhibition of THC-evoked responses at GPR18 with a potency in the mid-nanomolar range. Since THC and AM251 are often used in combination to suggest a role for CB1 cannabinoid receptors in vivo, this interpretation may need to be more cautious in the future.

To return to my initial question about how we refer to GPR18, for the moment, the most pragmatic solution would be to retain the GPR18 nomenclature but to allow the cannabinoid community to foster this orphan, at least until further research allows a more definitive decision to be made.

Glossary

- 2-AG

2-arachidonoylglycerol

- AEA

anandamide

- CBD

cannabidiol

- NAGly

N-arachidonoylglycerol

- THC

Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol

References

- Barbara G, Alloui A, Nargeot J, Lory P, Eschalier A, Bourinet E, et al. T-type calcium channel inhibition underlies the analgesic effects of the endogenous lipoamino acids. J Neurosci. 2009;29:13106–13114. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2919-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw HB, Rimmerman N, Krey JF, Walker JM. Sex and hormonal cycle differences in rat brain levels of pain-related cannabimimetic lipid mediators. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;291:R349–R358. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00933.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw HB, Rimmerman N, Hu SS, Benton VM, Stuart JM, Masuda K, et al. The endocannabinoid anandamide is a precursor for the signaling lipid N-arachidonyl glycine through two distinct pathways. BMC Biochem. 2009;10:14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2091-10-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gantz I, Muraoka A, Yang YK, Samuelson LC, Zimmerman EM, Cook H, et al. Cloning and chromosomal localization of a gene (GPR18) encoding a novel seven transmembrane receptor highly expressed in spleen and testis. Genomics. 1997;42:462–466. doi: 10.1006/geno.1997.4752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghafouri N, Tiger G, Razdan RK, Mahadevan A, Pertwee RG, Martin BR, et al. Inhibition of monoacylglycerol lipase and fatty acid amide hydrolase by analogues of 2-arachidonoylglycerol. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;143:774–784. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang SM, Bisogno T, Petros TJ, Chang SY, Zavitsanos PA, Zipkin RE, et al. Identification of a new class of molecules, the arachidonyl amino acids, and characterization of one member that inhibits pain. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:42639–42644. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107351200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohno M, Hasegawa H, Inoue A, Muraoka M, Miyazaki T, Oka K, et al. Identification of N-arachidonylglycine as the endogenous ligand for orphan G-protein-coupled receptor GPR18. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;347:827–832. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.06.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCue JM, Driscoll WJ, Mueller GP. Cytochrome c catalyzes the in vitro synthesis of arachidonoyl glycine. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;365:322–327. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.10.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh D, Hu SSJ, Rimmerman N, Juknat A, Vogel Z, Walker JM, et al. N-arachidonoyl glycine, an abundant endogenous lipid, potently drives directed cellular migration through GPR18, the putative abnormal cannabidiol receptor. BMC Neurosci. 2010;11:44. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-11-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh D, Page J, Dunn E, Bradshaw HB. Δ9-THC and N-arachidonyl glycine are full agonists at GPR18 and cause migration in the human endometrial cell line, HEC-1B. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;165:2414–2424. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01497.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh DY, Yoon JM, Moon MJ, Hwang JI, Choe H, Lee JY, et al. Identification of farnesyl pyrophosphate and N-arachidonylglycine as endogenous ligands for GPR92. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:21054–21064. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708908200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pertwee RG, Howlett AC, Abood ME, Alexander SPH, Di Marzo V, Elphick MR, et al. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. LXXIX. Cannabinoid receptors and their ligands: beyond CB1 and CB2. Pharmacol Rev. 2010;62:588–631. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.003004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prusakiewicz JJ, Kingsley PJ, Kozak KR, Marnett LJ. Selective oxygenation of N-arachidonylglycine by cyclooxygenase-2. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;296:612–617. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)00915-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin Y, Verdegaal EM, Siderius M, Bebelman JP, Smit MJ, Leurs R, et al. Quantitative expression profiling of G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) in metastatic melanoma: the constitutively active orphan GPCR GPR18 as novel drug target. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2011;24:207–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2010.00781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheskin T, Hanus L, Slager J, Vogel Z, Mechoulam R. Structural requirements for binding of anandamide-type compounds to the brain cannabinoid receptor. J Med Chem. 1997;40:659–667. doi: 10.1021/jm960752x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiles AL, Pearlman RJ, Rosvall M, Aubrey KR, Vandenberg RJ. N-Arachidonyl-glycine inhibits the glycine transporter, GLYT2a. J Neurochem. 2006;99:781–786. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JR, Khandoga AL, Goyal P, Fells JI, Perygin DH, Siess W, et al. Unique ligand selectivity of the GPR92/LPA5 lysophosphatidate receptor indicates role in human platelet activation. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:17304–17319. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.003194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin H, Chu A, Li W, Wang B, Shelton F, Otero F, et al. Lipid G-protein-coupled receptor ligand identification using β-arrestin pathhunter assay. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:12328–12338. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806516200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]