Abstract

Achieving satisfactory retention in online HIV prevention trials typically have proved difficult, particularly over extended timeframes. The overall aim of this study was to assess factors associated with retention in the Men’s INTernet Study II (MINTS-II), a randomized controlled trial of a sexual risk reduction intervention for men who have sex with men. Participants were recruited via e-mails and banner advertisements in December, 2007 to participate in the MINTS-II Sexpulse intervention and followed over a 12-month period. Retention across the treatment and control arms was 85.2% at 12 months. Factors associated with higher retention included: randomization to the control arm, previous participation in a study by the research team, e-mail and telephone reminders to complete a survey once it was available to take, and fewer e-mail contacts between surveys. The results provide evidence that achieving satisfactory retention is possible in online HIV prevention trials, and suggest best practices for maximizing retention.

Keywords: Retention, Internet, Randomized Controlled Trial, Men who have Sex with Men

Introduction

Recent reviews note both the enormous potential and the significant challenges facing online behavioral assessment and intervention research [1–6]. Online research is attractive because it allows access to hidden populations, has the potential to reach large numbers of potential participants, is relatively low-cost, and may not be as labor intensive with respect to data collection and management. Conversely, challenges of Internet-based research include the absence of a known sample frame from which participants are drawn and difficulty validating participant identity. Retaining participants in online longitudinal studies, the focus of this paper, also has been challenging. The overall aim of this paper is to examine 12-month retention in an Internet-based HIV prevention intervention targeting men who have sex with men (MSM), and the effects of retention strategies on overall retention.

Maintaining engagement in online behavioral studies may vary as a function of topic (e.g., weight loss v. sexual risk reduction), participant characteristics (e.g., high v. low motivation to change behavior), recruitment source (e.g., strictly online recruitment v. conventional recruitment sources), marketing strategy (e.g., online banner ads v. print media), the number and content of reminder messages to complete study activities, and length to follow-up. Retention rates are inconsistent across a variety of online intervention trial studies. Online interventions to increase physical activity or improve nutritional habits have yielded consistently high retention rates (>80%), with older and socioeconomically advantaged participants most likely to remain engaged (age>60 years) [7–9]. Similar success has been demonstrated in Internet-based weight loss interventions [10] and self-management programs for adults living with chronic conditions [11]. In comparison, retention rates after one year were lower in online studies of tobacco [(52% retention)12] and alcohol [(61% retention)13] use. Overall, studies vary widely by participant and design characteristics, making it difficult to identify factors consistently associated with high retention across these and other [14] online behavioral studies.

For this reason, comparing retention rates within topic and delivery mode may reduce the number of possible influences on retention, and provide greater insight into current dilemmas facing researchers as they attempt to maintain participant involvement. Since the early 2000s, a number of technology-based HIV risk reduction interventions have been conducted, against which more direct comparisons of retention rates can be made for the purpose of this study. A meta-analysis of 12 computer-delivered or Internet-based HIV prevention interventions reported retention rates between 37% and 95%, with only six of the twelve studies demonstrating greater than 70% retention [6]. The study with the longest follow-up period (24 months) showed a 64% retention rate [15], with follow-up time of the remaining eleven studies ranging from one to nine months. Three of the twelve interventions were delivered only on the Internet, with retention rates ranging from 37% to 81%. Although the Internet-based HIV prevention intervention with highest retention (i.e., 81%) was delivered online, its adolescent sample was initially recruited from local high schools using conventional recruitment strategies [16]. Overall, the meta-analysis of computer-based HIV prevention interventions clearly demonstrates that achieving adequate retention in such studies is a challenge, which has also been shown to be the case among similar studies [e.g., 17, 18, 19].

Responding to challenges of retention in online interventions, a variety of techniques to encourage participants to remain engaged have been used, including incentives [20], lotteries [21], and varying the frequency and personalization of communication with participants [22]. For example, to improve upon the 20% retention rate at 3 month follow-up found in an online sexual risk reduction intervention targeting youth [19], Bull and her colleagues established a more intensive follow-up reminder schedule, guaranteed incentives, and provided bonuses for completing all study activities in a follow-up study [23]. Retention increased to 53% at 2-month follow-up in the latter study as a result of these efforts, although they acknowledge that the retention rate still falls short of that expected in conventional intervention trials.

The aim of the Men’s Internet Study II (MINTS-II) was to estimate the effect of an online intervention to reduce sexual risk behavior among adult MSM with the overall goal of reducing HIV transmission. The study is unique in that participants were recruited and completed the intervention via the Internet, and were assessed at baseline, immediate post-intervention, and 3, 6, 9, and 12 months after completion of intervention activities. Anticipating that achieving acceptable retention would be challenging, we employed a variety of strategies to engage participants throughout the study period. In this paper, we seek to answer the following research questions:

For the overall sample and by treatment group assignments, what was the cumulative retention rate at each assessment period?

What effect does online recruitment source (direct e-mail v. online banner ad) have on cumulative retention?

Does cumulative retention vary by number of reminders to complete the survey at each assessment period?

Is there an optimal number of e-mail contacts with participants between assessment periods to maximize cumulative retention?

Does payment method affect cumulative retention?

The findings contribute to the growing body of research on the effects of strategies to achieve satisfactory long-term retention in Internet-based behavioral studies.

Methods

Eligibility Requirements and Recruitment Sources

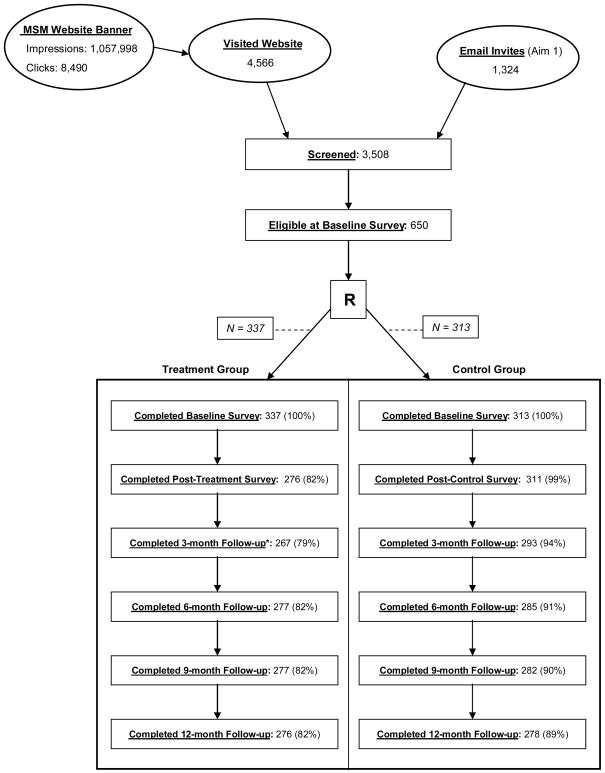

Participants were 650 Internet-using MSM enrolled in the MINTS-II intervention trial in December 2007. Potential participants were screened for eligibility, which included being 18 years or older, a US resident, and having consented to viewing sexually explicit materials online. In addition, because the primary purpose of the overall study was to determine the effect of the online HIV prevention intervention on self-reported risk behavior, MSM who engaged in unprotected intercourse were oversampled. Participants were recruited from one of two sources (see Figure 1). First, banner advertisements placed on two of the nation’s largest gay websites were used to connect 4,566 MSM to the study webpage to be screened for inclusion into the study. Second, 1,324 men who had completed an online sexual risk survey in August 2005 and expressed interest in future research opportunities [24] were sent an invitation e-mail with a link to connect them to the study webpage to be screened for inclusion into this study. Men who received the invitation e-mail were originally recruited for the 2005 survey using via online banner advertisements posted primarily in chat rooms of a website popular among MSM to socialize and seek sexual partners [24].

Figure 1.

Procedures

Participants who clicked on the banner advertisement or invitation e-mail link were taken to a secure study website. Prospective participants viewed a welcome page with an overview of procedures and information about the study and staff. Prospective participants’ IP addresses, which identifies the server that a computer is connected to, were recorded and used to block any individual from multiple entry attempts. After answering eligibility questions, eligible respondents were invited to give informed consent, in accordance with procedures approved by the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board, and to create a username and password for re-entry to the survey website. In addition, participants chose their preferred method of reimbursement that included using electronic money transfer (using PayPal©), traditional check, or donating their reimbursement to a HIV/AIDS charity. Participants selecting donation or electronic money transfer were required to provide a valid e-mail and a name or pseudonym. Those who selected to receive a traditional check also were required to provide a valid address for mailing. Ineligible persons viewed a separate webpage that thanked them for their interest.

A computer algorithm was used to randomize each person who met eligibility requirements, provided consent, and completed the baseline survey into either the treatment (n=337) or control (n=313) group. Excluding outliers (n=10), the mean length of intervention for participants completing the full treatment was 1 hour and 20 minutes, with a standard deviation of 35 minutes (for all participants completing intervention, the mean time for intervention completion was 1 hour 39 minutes with a standard deviation of 2 hours 9 minutes). Treatment and control group activities are described in greater detail elsewhere [25]. After completion of the treatment or control group activities, participants were provided immediate access to the post-treatment/control survey. Quarterly surveys of participants’ attitudes and HIV risk behavior were administered at four follow-up time periods (i.e., the 3-, 6-, 9- and 12-month follow-up survey). Compensation was set at $80 for completing the pretest, intervention and post-test, with an additional $20–25 for completing each follow-up survey. In addition, we held a quarterly “e-raffle” with a first prize of $150, which we describe in more detail below.

Reminder E-mail and Telephone Contact

Once a follow-up survey was to be completed, participants received an initial e-mail invitation that provided them immediate access to the survey. Participants who enrolled in the study were sent reminder e-mails to complete surveys at all assessment periods regardless of whether they completed or failed to complete any of the prior assessments (with the exception of the 3-month follow up as described below). Participants who did not respond after the first e-mail received up to two automated reminder e-mails scheduled one week apart. A more intensive retention strategy was initiated to encourage men who did not respond after the second reminder e-mail to complete the survey that included a telephone contact and a third reminder e-mail. Research staff made up to three telephone contact attempts (varied by day and time) to reach the participant in person; if unsuccessful, a generic voice message (to maintain participant confidentiality) was left on the third telephone contact attempt. Regardless of whether the participant was able to be contacted in-person or whether a voice message was left, a third and final personalized e-mail reminder (i.e., providing individualized information about their level of their involvement and, if the participant started the survey, how much they have left to complete) was sent asking them to take or complete the survey. If the participant was unresponsive after the final reminder, he was considered a non-completer for that assessment period.

Interim Contact

In addition, to study the optimal number of e-mail contacts in between follow-up assessment surveys that would keep participants engaged, participants were randomized into one of three contact groups: 1) every month (i.e., twice between follow-up surveys), 2) every one and a half months (i.e., once between follow-up surveys), or 3) every 3 months (i.e., when the survey was opened for participants to complete). Interim e-mail contacts allowed participants to verify and/or update their contact information and enter an e-raffle for a cash drawing (worth $150) that was held each quarter. Regardless of interim contact group to which participants were assigned, all participants were provided equal opportunity to win the cash drawing by clicking on the link in the e-mail (e.g., monthly interim contact group members were provided two lottery tickets per contact, 1.5 month contact group members were provided 3 tickets per contact, and the quarterly contact group members were provided six lottery tickets per contact).

Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using STATA 9.2 [26]. Retention at baseline and follow-up assessments were calculated using frequencies and percentages. Tests of proportions were conducted between the once a month interim contact group and the every 1.5 months interim contact group. We chose to compare these two groups, rather than statistically exploring differences between all potential pairs of groups, to limit the number of statistical comparisons and because retention rates were similar between the every 1.5 month and every 3 months contact group (as shown in the analyses below).

Multiple logistic regression analyses were used to determine the effects of study assignment and retention strategies on 12-month retention, controlling for individual-level factors (e.g., race/ethnicity, education, and age). The first model examined the effect of study assignment on retention, while the individual level factors were introduced in the second model. In the final model, payment type, interim contact, and recruitment source were introduced. Reminder e-mail was not included in the final model because the number of reminder e-mails could vary within person and across time, and therefore could not be accounted for in the analyses.

Results

Overall Retention (Figure 1)

Of the 650 men who enrolled in the study, overall retention dropped most precipitously between enrollment and the post-treatment/control survey (90.3% retention). At the 3-month follow-up survey period, we failed to send those participants who did not complete the post-treatment/-control survey (n=63) a reminder e-mail in error; the error was corrected in the subsequent follow-up survey periods. Adjusting for this error at the 3-month follow-up period, an additional 4% loss occurred (86.2% retention). After the 3-month follow-up, retention remained relatively stable across both study arms: 86.5% at 6-month follow-up, 86.0% at 9-month follow-up, and 85.2% at 12-month follow-up. Overall, 78.9% of participants completed all five surveys, although a higher percentage of men in the control arm (85.6%) completed all five surveys than those in the treatment arm (72.7%). Among those participants who did not complete the 3-month follow-up reminder e-mail because they failed to complete the assigned treatment and did not receive the reminder e-mail in error, approximately 30% were retained at the end of the study (n = 17/63 at 6-month, 19/63 at 9-month and 20/63 at 12-month).

Figure 1 shows retention by study arm. At the post-treatment/control period and each of the follow-up survey periods, retention was higher in the control group than the treatment group. Within the treatment group, retention dropped most precipitously during the intervention period. At the 12-month follow-up period, the treatment arm retained 82% of participants, while the control arm retained 89% of participants.

Retention by Recruitment Source (Table I)

Table I.

Cumulative Retention at Each Post-Condition Survey by Recruitment Source (N = 650)

| Recruitment Source | Treatment Group | Control Group | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Email (%) | Banner Ad (%) | Email (%) | Banner Ad (%) | |

| Participants enrolled at Baseline (N) | 71 | 266 | 62 | 251 |

| Post-Condition Survey | 95.8 | 78.2 | 100.0 | 99.2 |

| 3-month Follow-up* | 98.5 | 96.2 | 100.0 | 92.8 |

| 6-month Follow-up | 90.1 | 80.1 | 98.4 | 89.2 |

| 9-month Follow-up | 91.5 | 79.7 | 96.8 | 88.4 |

| 12-month Follow-up | 90.1 | 79.7 | 98.4 | 86.5 |

The overall N for each survey is 650 except for the 3-month survey, where N = 587.

Retention varied by recruitment source. As shown in Table I, men recruited using existing e-mails were retained at higher rates than participants recruited using online banner advertisements. At 12 months, retention was lowest among the men recruited through banner ads and randomized into the treatment arm (79.7% retention), with highest retention among men recruited using existing e-mails and randomized into the control arm (98.4%).

Retention by Number of Reminder E-mails (Table II)

Table II.

Retention at Each Post-Treatment Survey by Number of Reminder Emails (N = 650)

| 0 reminders | 1 reminder | 2 reminders | 3+ reminders | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reminders Sent (n) | Of reminders, % completed | Reminders Sent (n) | Of reminders, % completed | Reminders Sent (n) | Of reminders, % completed | Reminders Sent (n) | Of reminders, % completed | |

| 3-month Follow-up* | 587 | 72.2 | 163 | 43.6 | 92 | 42.4 | 53 | 49.1 |

| 6-month Follow-up | 650 | 61.4 | 251 | 34.7 | 164 | 34.1 | 108 | 18.5 |

| 9-month Follow-up | 650 | 59.8 | 261 | 31.8 | 178 | 23.6 | 136 | 33.1 |

| 12-month Follow-up | 650 | 58.9 | 267 | 31.1 | 184 | 27.7 | 133 | 27.8 |

The overall N for each survey is 650 except for the 3-month survey, where N = 587.

The percentage of participants who completed the survey after receiving just one reminder diminished across time. For example, at the 3-month follow-up period, 43.6% of the remaining participants (i.e., of those who did not complete after receiving the initial e-mail allowing them access to the survey) completed the survey after receiving one reminder e-mail. The percentage of participants responding to the first reminder e-mail decreased steadily at the 6- (34.7%), 9- (31.8%) and 12- (31.1%) month assessment periods. However, across the number of reminder e-mails sent at each assessment period, the percentage of remaining participants who completed the survey after receiving a reminder remained relatively consistent. For example, at the 12-month follow-up, between 27.7% and 31.1% of the remaining participants completed the survey after receiving additional reminders. However, as described above, the final reminder was an intensive effort (consisting of a telephone reminder and a final e-mail reminder) by research staff to keep the participant engaged, which may explain its success.

Retention by Interim Contact (Table III)

Table III.

Cumulative Retention at Each Post-Treatment Survey by Frequency of Interim Contact, among Participants recruited via Banner Advertisement (N = 517)

| Contact Every 1 Month (%) | Contact Every 1.5 Months (%) | Contact Every 3 Months (%) | p-value† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants enrolled at Baseline (N) | 180 | 168 | 169 | - |

| 3-month Follow-up* | 89.9 | 96.0 | 97.3 | 0.041 |

| 6-month Follow-up | 79.4 | 86.9 | 87.6 | 0.064 |

| 9-month Follow-up | 77.8 | 85.1 | 89.3 | 0.079 |

| 12-month Follow-up | 76.7 | 85.1 | 87.6 | 0.046 |

The overall N for each survey is 517 except for the 3-month survey, where N = 457 due to a programming error.

The p-value, which is based on a proportions test, compares the difference between the group receiving contact each month with the group receiving contact every 1.5 months.

Participants were contacted between surveys on average either once a month, once every one and a half months, or only every 3 months when a survey was opened to be taken. Table III shows retention by interim contact group only for those recruited by banner advertisement. Retention rates by interim contact among participants recruited by e-mail are not shown in the table for two reasons. First, uniformly high retention across assessment periods for men recruited by e-mail precludes finding significant differences in retention rates by interim contact group (which was indeed found when tests of proportions were conducted, not shown). Second, the previous history of men recruited via e-mail with earlier aspects of the study may bias the effects of the interim contacts on retention; therefore, even if significant differences were found, they would be difficult to interpret.

For men recruited into the study by banner advertisement, the one and a half month contact and every three month contact groups demonstrated similar retention at each assessment period (e.g., 85.1% and 87.6% retention at 12 month assessment for the 1.5 and 3 month contact group, respectively). However, participants who were contacted monthly between surveys were less likely to be retained at 3- (89.9%) and 12- (76.7%) month follow-up compared to men who were contacted every 1.5 months (96.0% and 85.1%, respectively, p<.05).

Retention by Payment Type (Table IV)

Table IV.

Cumulative Retention by Payment Type, Stratified by Recruitment Source and Study Group

| Recruited via Email | Recruited via Banner Ad | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paypal (%) | Check (%) | Donation (%) | Paypal (%) | Check (%) | Donation (%) | |

|

| ||||||

| % completed, (cell n) | % completed, (cell n) | % completed, (cell n) | % completed, (cell n) | % completed, (cell n) | % completed, (cell n) | |

| Participants enrolled at baseline (N) | 47 | 83 | 3 | 85 | 417 | 15 |

| 3-month Follow-up* | ||||||

| Treatment Group (n=276) | 96.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 95.9 | 80.0 |

| Control Group (n=311) | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 95.1 | 92.0 | 100.0 |

| 6-month Follow-up | ||||||

| Treatment Group (n=337) | 92.0 | 88.6 | 100.0 | 83.7 | 80.0 | 62.5 |

| Control Group (n=313) | 100.0 | 97.4 | 100.0 | 90.5 | 88.6 | 100.0 |

| 9-month Follow-up | ||||||

| Treatment Group (n=337) | 92.0 | 91.9 | 100.0 | 81.4 | 80.5 | 50.0 |

| Control Group (n=313) | 100.0 | 94.9 | 100.0 | 92.9 | 88.1 | 71.4 |

| 12-month Follow-up | ||||||

| Treatment Group (n=337) | 92.0 | 88.6 | 100.0 | 81.4 | 80.9 | 37.5 |

| Control Group (n=313) | 100.0 | 97.4 | 100.0 | 90.5 | 86.1 | 71.4 |

The overall N for each survey is 650 except for the 3-month survey, where N = 587.

Retention at each survey period by study arm and payment type is shown in Table IV. Noticeably, participants who were recruited with online banner advertisements and opted to donate their reimbursement showed the lowest retention, particularly for those randomized to the treatment arm (37.5% retention at 12-month follow-up). Moreover, participants who were recruited via online banner advertisements and opted to receive a check for reimbursement had slightly lower retention rates at 12 months for both the treatment (80.9%) and the control (86.1%) group than participants who were recruited by e-mail and opted to be reimbursed by electronic money transfer. Independent of whether participants were recruited via e-mail or an online banner advertisement, there appeared to be a noticeable drop on retention between the 3- and 6-month follow-up surveys for participants who opted to receive a check for reimbursement.

Estimated effect of retention strategies on retention (Table V)

Table V.

Factors Associated with Study Retention at 12-month Follow-up using Multiple Logistic Regression (N=650)*

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p-value | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p-value | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p-value | |

| Study Assignment | ||||||||||

| Treatment Group | 337 | 0.57 | 0.36 – 0.89 | 0.014 | 0.57 | 0.36 – 0.90 | 0.016 | 0.55 | 0.34 – 0.88 | 0.012 |

| Control Group | 313 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||||||

| Hispanic or Latino | 98 | 0.77 | 0.43 – 1.39 | 0.383 | 0.65 | 0.34 – 1.22 | 0.181 | |||

| Other Race | 109 | 1.42 | 0.73 – 2.75 | 0.304 | 0.99 | 0.49 – 2.01 | 0.979 | |||

| White | 443 | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||

| Level of Education | ||||||||||

| Less than College Degree | 274 | 0.58 | 0.37 – 0.91 | 0.017 | 0.60 | 0.38 – 0.95 | 0.031 | |||

| College Degree or More | 376 | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||

| Age (Continuous) | - | 1.00 | 0.98 – 1.03 | 0.666 | 1.01 | 0.99 – 1.03 | 0.495 | |||

| Payment Type | ||||||||||

| Paypal | 132 | 1.28 | 0.68 – 2.41 | 0.438 | ||||||

| Donate | 18 | 0.21 | 0.07 – 0.62 | 0.005 | ||||||

| Check | 500 | - | - | - | ||||||

| Interim Contact Group | ||||||||||

| Monthly | 217 | 0.46 | 0.26 – 0.80 | 0.007 | ||||||

| Every 1.5 Months | 219 | 0.76 | 0.41 – 1.39 | 0.369 | ||||||

| Quarterly | 214 | - | - | - | ||||||

| Recruitment Type | ||||||||||

| Banner | 517 | 0.30 | 0.13 – 0.68 | 0.004 | ||||||

| 133 | - | - | - | |||||||

Notes: Total cumulative attrition is 96 participants of 650. Moreover, all regression analyses model the odds of retention such that retention = 1 and attrition = 0.

The effects of payment type, interim contact, and recruitment source on retention at 12 months, adjusted for study assignment and individual-level factors, is shown in Model 3 in Table V. Compared to payment by check, odds of retention was lower for participants opting to donate their reimbursement (OR=0.21; 95%CI=0.07–0.62, p=.005). In addition, men who received monthly interim e-mails had lower odds of retention than men who received only quarterly e-mails (OR=0.46; 95%CI=0.26–0.80, p=.007), and men who were recruited via banner ads had lower odds of retention compared to men recruited through e-mail (OR=0.30; 95%CI=0.13–0.68, p=.004). Across all models, being assigned to the treatment group (in the fully adjusted model: OR=0.55; 95%CI=0.34–0.88, p=.012) and not holding an undergraduate college degree (in the fully adjusted model: OR=0.60; 95%CI=0.38–0.95, p=.031) were associated with lower retention.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine retention during the MINTS-II intervention trial and assess which strategies appeared to be associated with improved or poorer retention. A number of conclusions can be drawn from the results. First, obtaining long-term retention rates similar to those seen in conventional HIV prevention trials is achievable, as demonstrated by the finding that nearly 79% of participants were retained at 12 months in this trial. Second, retention rates may be significantly improved by developing an ongoing relationship with research participants. Third, the number of contacts with participants between assessments must be carefully considered, as the results from our randomized sub-study suggest that high frequency contact may be detrimental to retention. Each of these points is elaborated on in more detail below.

The retention rate in the MINTS-II intervention trial was considerably higher than that from comparable online HIV prevention trials [17, 18, 27], despite the longer assessment period in this study. We attribute part of the success of maintaining participant involvement in this study to the rigorous retention protocol that was developed and implemented. In particular, telephoning those participants who had not responded to the second reminder e-mail yielded an 18–49% increase in participation across the assessment periods. Anecdotally, study staff who made the telephone reminder calls remarked on the large number of participants who seemed genuinely surprised by the personal telephone call. Our experience, and that of other researchers who also have included telephone contact into their retention protocol for online intervention trials [23], suggests that using multiple modes of contact with participants is a key factor to maintaining engagement among traditionally hard to retain participants [28]. The response of surprise to the telephone calls suggests that participants who are the most difficult to retain in online research trials may fail to fully appreciate the significant resources in study staff and time needed to conduct Internet-based research, or that online studies require study staff at all. Alternatively, these participants may not have initially understood the expectation for involvement in online research is similar to that in conventional research studies.

Retention was higher for participants who were screened and enrolled from a prior online study conducted by this research group, compared to those recruited directly from the online banner advertisement (most of whom we presume had not been involved with this study before). Although we did not ask men to rate their level of connection they felt with study staff during the intervention trial, it is possible that the high rate of retention among men recruited from the existing database reflects positive rapport between study staff and these participants. Studies of other difficult to retain participants note the importance of establishing rapport with participants [28–30]. Compared to offline studies, Internet-based studies have the advantage that establishing rapport with participants may be as easy as a series of regular e-mailings. However, while face-to-face studies may engender trust between participants and research staff, establishing credibility in online research can be more of a challenge [31, 32]. Establishing a high level of rapport not only entails having regular contact with participants, but also requires that online studies be responsive to participant inquiries and follow through with participant payment in a timely manner. Our experience shows that taking these steps may yield a highly invested participant pool (as appeared to be the case with the group of men who were enrolled in this study using the e-mail they provided in a prior survey), while failure to do so may be damage the reputation of the research team and online research in general. Alternative explanations to the high retention rates among this group of participants are, first, that they may represent a group of individuals who are highly invested in the research process regardless of history with any one particular research study or, second, that men who maintain involvement over years of a study may be highly compliant.

Importantly, regular contact with participants to establish and maintain rapport must be weighed against the possibility that too much contact may be detrimental to retention. Findings from our randomized sub-study showed little difference in retention between participants contacted on average once in between three month assessment periods and those who were contacted every three months when the survey was opened. In contrast, lower retention was found among participants contacted monthly during the trial, which may be attributed to several factors. First, some participants receiving monthly e-mails from study staff may have felt irritated or burdened by the frequency of e-mails and consequently withdrew from the study. Verifying participant annoyance with the regularity of e-mails is difficult and we did not record any calls from participants asking us to stop e-mailing them during the trial. A second possibility is that some participants chose to ignore e-mails from study staff once they realized that most e-mails were not reminders to take a survey. Thus, over time, an increasingly greater number of participants receiving monthly e-mails deleted them without determining if the purpose of the e-mail was to maintain interim contact or to remind them to take a survey. Regardless of the possible reasons for lower retention among this group, this finding suggests that there is an optimal frequency of contact with participants to maintain their involvement, and we caution researchers not to assume that more contact yields higher retention.

In addition to these main findings, several other results are worth considering. First, most participants opted to be reimbursed by receive a traditional check, compared to receiving payment electronically or donating their reimbursement. Interestingly, although few men opted to donate their reimbursement, those who did were less likely to be retained at 12 months than men who received reimbursement by check. In fact, only slightly more than one-third of those men who were assigned to the treatment arm of the intervention were retained at 12 months. The combination of relatively high burden combined with no personal monetary benefit may hinder motivation to persist in a study over time, although this possibility must be verified with further experimental evidence. Researchers looking to provide participants with payment options should consider choices that will continue to motivate participants, or allow participants to modify their payment choice throughout the study.

Second, we found lower retention among participants assigned to the treatment group compared to participants assigned to the control group. The time commitment required to complete the intervention for those assigned to the treatment group, which is where the majority of drop-out occurred, was notably longer compared to that required of men assigned to the control condition. Additionally, the time commitment required for the intervention group was longer than the time commitment described in previous online HIV prevention interventions [18, 27]. Participant burden has long been recognized to influence involvement in offline [33, 34] and online studies [35], and it appears that participant burden may have affected retention in this study.

Third, failure to send the 63 participants who did not complete the assigned treatment the 3-month follow-up e-mail reminder provided a natural experiment in which to evaluate the effectiveness of our retention protocol among this group of select participants. Overall, we found that 30% of these participants were retained at 12-months, in spite of not completing the post-intervention/control survey or 3-month survey. These participants are likely difficult to retain in general given their non-compliance to the treatment protocol, suggesting that our retention protocol demonstrated some effectiveness even among presumably non-compliant individuals.

Study Limitations

The results may not generalize to other study populations. MSM were early adopters of the Internet for sex-seeking purposes [36], and therefore strategies to retain Internet-savvy participants in online intervention trials may be different than for persons with less online experience. Studies to assess the degree to which the retention strategies used in this study may be useful in other populations should be undertaken. We cannot rule out the possibility that the generous reimbursement for completing study activities may have influenced retention rates. The high retention rate among the men recruited by e-mail may have been the result of their previous experience with reimbursement for participation in the earlier survey. Nor can we exclude the possibility that we recruited a highly motivated, self-selected group of individuals into our study, thereby resulting in higher retention rates. In particular, men who entered the study via the invitation e-mail had participated in a previous study and expressed interest in future research opportunities, indicating that this is a highly motivated group of individuals. Moreover, a large number of men who visited the study via banner advertisement did not participate in the study. Although some of these men were ineligible, it is likely that a portion of these men chose not to participate due to the anticipated time commitment, study topic, or other unknown reasons. Nonetheless, compared to previous studies with similar recruitment methods, we managed to achieve high levels of retention. Finally, we did not assess the personal motivations of participants who were retained in, or chose to drop out of, the study, which may be an important area for future research.

Conclusions

We believe the results of this study are encouraging for future online intervention trials, particularly with hidden or hard-to-reach populations. Despite its ease of use, Internet-based behavioral research frequently suffer from insufficient retention rates, leading some to question its utility. However, over 70% of participants assigned to the treatment group in this study were retained after one year. We believe the results have implications for researchers wishing to conduct online HIV intervention studies and for areas of future research. For interventionists, maintaining a database of participants willing to participate in studies may provide a highly motivated and engaged participant pool. However, the database must be regularly updated and used judiciously. The methodological rigor of the intervention can be maintained by screening all participants for inclusion into the study, regardless of whether they have participated in prior studies by the research team. In addition, interventionists must carefully consider the appropriate level of contact between assessment periods to maximize retention. Our results suggest that too frequent of contact may be detrimental to retention goals. Similarly, offering a donation option for participant reimbursement may be problematic, as the motivation of participants who do not receive direct compensation for their efforts may lag over time. Finally, these results suggest that treatment burden may adversely affect retention over time. Online behavioral intervention researchers must carefully balance burden placed on participants during intervention with ensuring that the intervention is sufficiently intensive to promote behavior change. For this and other reasons, pilot testing the online intervention prior to implementing the full study is critical.

Advancing our understanding of retention in online behavioral studies would benefit from gaining greater insight into personal motivations for remaining engaged in, or dropping out from, long-term studies. In addition, the complex relationship between previous participation in research surveys or interventions and level of reimbursement warrants further study. Although much remains to be learned, the results of the MINTS-II trial demonstrate that investing time and resources into the retention process, that includes both automated and personalized contact with participants, yields high rates of retention.

References

- 1.Couper MP, Miller PV. Web survey methods: Introduction. Public Opin Q. 2008;72:831–5. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pequegnat W, Rosser BR, Bowen AM, et al. Conducting Internet-based HIV/STD prevention survey research: Considerations in design and evaluation. AIDS Behav. 2007;11:505–21. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9172-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Naglieri JA, Drasgow F, Schmit M, et al. Psychological testing on the Internet: New problems, old issues. Am Psychol. 2004;59:150–62. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.3.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wantland D, Portillo C, Holzemer W, Slaughter R, McGhee E. The effectiveness of web-based vs. non-web-based interventions: A meta-analysis of behavioral change outcomes. J Med Internet Res. 2004;6:e40. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6.4.e40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Griffiths F, Lindenmeyer A, Powell J, Lowe P, Thorogood M. Why are health care interventions delivered over the internet? A systematic review of the published literature. J Med Internet Res. 2006;8:e10. doi: 10.2196/jmir.8.2.e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Noar SM, Black HG, Pierce LB. Efficacy of computer technology-based HIV prevention interventions: A meta-analysis. AIDS. 2009;23:107–15. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32831c5500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verheijden MW, Jans MP, Hildebrandt VH, Hopman-Rock M. Rates and determinants of repeated participation in a web-basedbehavior change program for healthy body weight and healthy lifestyle. J Med Internet Res. 2007;9:e1. doi: 10.2196/jmir.9.1.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glasgow RE, Nelson CC, Kearney KA, et al. Reach, engagement, and retention in an Internet-based weight loss program in a multi-site randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2007;9:e11. doi: 10.2196/jmir.9.2.e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alexander GL, McClure JB, Calvi JH, et al. A randomized clinical trial evaluating online interventions to improve fruit and vegetable consumption. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:319–26. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.154468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stevens VJ, Funk KL, Brantley PJ, et al. Design and implementation of an interactive website to support long-term maintenance of weight loss. J Med Internet Res. 2008;10:e1. doi: 10.2196/jmir.931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lorig KR, Ritter PL, Dost A, Plant K, Laurent DD, McNeil I. The Expert Patients Programme online, a 1-year study of an Internet-based self-management programme for people with long-term conditions. Chronic Illn. 2008;4:247–56. doi: 10.1177/1742395308098886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.West R, Gilsenan A, Coste F, et al. The ATTEMPT cohort: A multi-national longitudinal study of predictors, patterns and consequences of smoking cessation; introduction and evaluation of internet recruitment and data collection methods. Addiction. 2006;101:1352–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koski-Jannes A, Cunningham J, Tolonen K. Self-assessment of drinking on the Internet--3-, 6- and 12-month follow-ups. Alcohol Alcohol. 2009;44:301–5. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agn124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van ‘t Riet J, Crutzen R, De Vries H. Investigating predictors of visiting, using, and revisiting an online health-communication program: A longitudinal study. J Med Internet Res. 2010;12:e37. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McFarlane M, Kachur R, Klausner JD, Roland E, Cohen M. Internet-based health promotion and disease control in the 8 cities: Successes, barriers, and future plans. Sex Transm Dis. 005;32(10 Suppl):S60–4. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000180464.77968.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roberto AJ, Zimmerman RS, Carlyle KE, Abner EL. A computer-based approach to preventing pregnancy, STD, and HIV in rural adolescents. J Health Commun. 2007;12(1):53–76. doi: 10.1080/10810730601096622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bowen A, Williams M, Daniel C, Clayton S. Internet based HIV prevention research targeting rural MSM: Feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy. J Behav Med. 2008;31:463–77. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9171-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kok G, Harterink P, Vriens P, deZwart O, Hospers H. The gay cruise: Developing a theory- and evidence-based Internet HIV-prevention intervention. Sex Res Soc Pol. 2006;3:52–67. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bull S, Lloyd L, Rietmeijer C, McFarlane M. Recruitment and retention of an online sample for an HIV prevention intervention targeting men who have sex with men: The Smart Sex Quest Project. AIDS Care. 2004;16:931–43. doi: 10.1080/09540120412331292507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goritz A. Incentives in web studies: Methodological issues and a review. Int J Internet Sci. 2006;1:58–70. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goritz AS, Wolff H-G. Lotteries as incentives in longitudinal web studies. Soc Sci Comput Rev. 2007;25:99–110. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cook C, Heath F, Thompson RL. A meta-analysis of response rates in web- or Internet-based surveys. Educ Psychol Meas. 2000;60:821–36. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bull S, Vallejos D, Levine D, Ortiz C. Improving recruitment and retention for an online randomized controlled trial: Experience from the Youthnet study. AIDS Care. 2008;20:887–93. doi: 10.1080/09540120701771697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosser BRS, Oakes JM, Horvath KJ, Konstan JA, Peterson JA. HIV sexual risk behavior by men who use the Internet to seek sex with men: Results of the Men’s INTernet Sex Study-II (MINTS-II) AIDS Behav. 2009;13:488–98. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9524-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosser BRS, Oakes JM, Konstan J, et al. Reducing HIV risk behavior of MSM through persuasive computing: Results of the Men’s INTernet Study (MINTS-II) AIDS. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833c4ac7. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software. 9. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bowen AM, Horvath K, Williams ML. A randomized control trial of Internet-delivered HIV prevention targeting rural MSM. Health Educ Res. 2007;22(1):120–7. doi: 10.1093/her/cyl057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robles N, Flaherty DG, Day NL. Retention of resistant subjects in longitudinal studies: Description and procedures. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1994;20:87–100. doi: 10.3109/00952999409084059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Evans ME, Mejia-Maya LJ, Zayas LH, Boothroyd RA, Rodriguez O. Conducting research in culturally diverse inner-city neighborhoods: Some lessons learned. J Transcult Nurs. 2001;12:6–14. doi: 10.1177/104365960101200102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Steinhauser KE, Clipp EC, Hays JC, et al. Identifying, recruiting, and retaining seriously-ill patients and their caregivers in longitudinal research. Palliat Med. 2006;20:745–54. doi: 10.1177/0269216306073112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.James N, Busher H. Credibility, authenticity and voice: Dilemmas in online interviewing. Qual Res. 2006;6:403–20. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosser B, Gurak L, Horvath KJ, Oakes J, Konstan J, Danilenko GP. The challenges of ensuring participant consent in Internet-based sex studies: A case study of the men’s INTernet sex (MINTS-I and II) studies. J Comput Mediated Commun. 2009;14:602–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1083-6101.2009.01455.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schulz CH, Wasserman J, Ostwald SK. Recruitment and retention of stroke survivors: The CAReS experience. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 2006;25:17–29. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wipke-Tevis DD, Pickett MA. Impact of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act on participant recruitment and retention. West J Nurs Res. 2008;30:39–53. doi: 10.1177/0193945907302666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Formica M, Kabbara K, Clark R, McAlindon T. Can clinical trials requiring frequent participant contact be conducted over the Internet? Results from an online randomized controlled trial evaluating a topical ointment for herpes labialis. J Med Internet Res. 2004;6:e6. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6.1.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McFarlane M, Bull SS, Rietmeijer CA. The Internet as a newly emerging risk environment for sexually transmitted diseases. JAMA. 2000;284(4):443–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.4.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]