Abstract

Background

Few behavioral interventions have been conducted to reduce high-risk sexual behavior among HIV-positive Men who have Sex with Men (HIV+MSM). Hence, we lack well-proven interventions for this population.

Methods

Positive Connections is a randomized controlled trial (n=675 HIV+MSM) comparing the effects of two sexual health seminars – for HIV+MSM and all MSM – with a contrast prevention video arm. Baseline, 6-, 12- and 18-month follow-up surveys assessed important psychosexual variables and frequency of serodiscordant unprotected anal intercourse (SDUAI).

Results

At post-test, intentions to avoid transmission were significantly higher in the sexual health arms. However, SDUAI frequency decreased equally across all arms, from 15.0 at baseline to 11.5 at 18 months. HIV+MSM engaging in SDUAI at baseline were more likely to leave the study.

Discussion

Tailoring interventions to HIV+MSM does not appear to increase the effectiveness of HIV prevention. A sexual health approach appears no more effective than video-based HIV prevention.

Keywords: HIV+MSM, MSM, HIV prevention, behavioral interventions, unsafe sex, prevention for positives

Background

Men who have Sex with Men (MSM) remain the largest population infected with HIV/AIDS in the United States. They comprise 48.1% of the 1.1 million adults and adolescents living with HIV nationally, and 53% of the 56,300 new HIV cases.1, 2 Surveillance studies of MSM in HIV epicenters estimate that between 8% and 20% of the MSM population is living with HIV/AIDS.3 Early HIV primary prevention efforts appeared highly effective in reducing unsafe sex and HIV transmission among MSM.4 However, since the introduction of HAART in 1995, rates of unsafe sex, sexually transmitted diseases and HIV infection have been increasing among MSM in the United States and other industrialized countries.3, 5, 6 Furthermore, HIV+MSM appear disproportionately overrepresented in newly acquired sexually transmitted infections,5, 7 suggesting high rates of high-risk sexual behaviors in this population.

In response to these statistics, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued two national alerts calling for new and renewed HIV prevention efforts targeting MSM.8, 9 A meta-analysis of HIV prevention interventions for MSM concluded that such programs appear to increase the odds of condom use by 81%.10 However, the majority of MSM in these studies were HIV-negative, and stratified analyses of the effects on HIV+MSM have not been published. Two other meta-analyses examined the efficacy of HIV prevention risk-reduction interventions for persons living with HIV. The first reviewed 19 trials11 concluding that behavioral interventions are effective in reducing the odds of unprotected anal intercourse by 27–43%. The second reviewed 15 trials, noting while interventions for other persons living with HIV had been demonstrated, interventions using HIV+MSM samples have been tried, but their effectiveness is not well-demonstrated.12 Indeed, the greater the percentage of HIV+MSM enrolled, the worse the outcome of the trial. Hence, whether HIV prevention interventions reduce the sexual risk behavior of HIV+MSM remains unclear, while the need for effective interventions remains urgent.

Intervention trials for HIV+MSM remain a severely understudied area. In all, we could find only 7 trials that included HIV+MSM, and only two others that exclusively recruited HIV+MSM. Cleary et al.13 offered a 9 hr (6 × 1.5 hr) group risk reduction program to HIV-positive blood donors, 71% of whom were HIV+MSM. No differences between experimental and control groups were found. Patterson et al.14 conducted a 4-arm trial of single session counseling, 85% of participants were MSM. However, HIV+MSM randomized to the longer comprehensive intervention reported significantly higher risk at 12-month follow-up than men in the other three (shorter) conditions, including an attention control. Caballo-Diéguez and colleagues tested a 16 hr (2 hr × 8 weeks) bilingual group-level intervention in New York for Latino gay/bisexual men, 35% of whom were HIV-positive.15 They reported steep deceases in UAI between baseline (100%) and follow-up (33%), but found no differences between experimental and control conditions.

Richardson et al.16 recruited 886 HIV-positive patients (74% MSM) randomized (by clinic) to conditions where physicians delivered different prevention messages. Those in the “loss frame” clinics reported significantly lower unprotected sex at 7-month follow-up. However, differential participation by HIV+MSM and differential attrition were noted problems, highlighting the risk inherent in mixed (MSM and non-MSM) studies of HIV where risk behavior is likely to differ substantially by gender and sexual orientation.

The Seropositive Urban Men’s Intervention Trial (SUMIT) recruited exclusively HIV+MSM in New York and San Francisco, randomized to either 18 hours (6 × 3hr) group counseling sessions or a 1-session counseling contrast condition, with 3- and 6-month follow-up.17 Post-test measures were highly encouraging, with men in the enhanced condition reporting significantly greater satisfaction and intention measures than the contrast arm. However, SDUAI at baseline was 35%, and 27–31% at follow-up, with no significant differences observed between the intervention arms.

The most promising findings were from two studies. Kalichman et al.18 randomized 233 men (53% MSM) and 99 women to 5 × 2hr weekly group sessions on either sexual risk reduction or health maintenance. They report greater reduction in serodiscordant unprotected anal/vaginal sex at 6 month follow-up in the intervention group (−56%) than control (+200%).

In the Healthy Living Project study just published, Morin et al.19 randomized HIV+MSM to either 15 90-minute sessions of individually delivered cognitive behavioral intervention (n=301) or a wait-list control (n=315). Like the Kalichman study, assessment of risk behavior, last 90 days, was through interviews of risk reviewed partner-by-partner using audio computer assisted self-interviewing (ACASI) or computer assisted personal interviewing (CAPI) for up to 5 sexual partners. They report significant reduction in the number of serodiscordant unprotected anal intercourse acts in both the intervention arm and control arms at the 5, 10, 15 and 20 month assessments. Men in the intervention condition reported a greater proportion of sexual partners who were HIV-infected at the 5 and 10 month assessments. Thus, they conclude a net reduction in risk with serodiscordant partners in the intervention arm. However, problems with assessment (31% of the sample had more than 5 partners at some time point) are a noted limitation.

We compared the demographic and research characteristics of these samples. In previous trials, the majority of participants in HIV+MSM studies have been white, middle-aged, and about half had an AIDS diagnosis. In multi-session interventions, “dosage” (intervention attendance) appears problematic with some studies reporting only 17–40% of participants attending the entire intervention. Retention during follow-up varied from 64% to 90%. In several trials, immediate post-intervention measures predicted strong intentions to lower risk but behavior change was minimal. In at least one trial, less intervention appeared more effective. Where contrast conditions were used (versus wait list controls), similar rates of behavioral decrease in the less intensive intervention were observed.

In summary, while interventions for HIV-positives have been rigorously evaluated and found effective in other populations, those for HIV+MSM have proved more challenging. Recruitment sampling, intervention dosing and retention have been problematic in some studies, while the use of mixed samples (HIV-positive samples of both MSM and non-MSM; or MSM samples of both HIV-positive and HIV-negative participants) has left results open to multiple interpretation.16

This study is based upon considerable work by our team and others in adapting sexual health education to HIV prevention.20 We based our interventions upon the Sexual Health Model.21 Based off core curriculum topics codified by the American Association of Sex Educators, Counselors and Therapists, this model aims to: 1) promote an increased understanding of participants’ own sexuality; and 2) help participants analyze their attitudes towards the sexuality of others.22 This model posits that sexually healthy persons will be more likely to make sexually healthy choices. Applied to HIV prevention, this includes decisions concerning HIV and sexual risk behaviors.21 A sexual health approach conceptualizes unsafe sex as possibly symptomatic of other underlying sexual concerns (e.g., less safer sex intentions, poorer sexual health, discomfort with sexuality, internalized homonegativity, lack of altruism, and lack of condom self-efficacy). These need to be addressed for a person to maintain safer-sex practices long-term, and for HIV-positive persons to reduce their risk of transmitting HIV. Sexual health interventions, then, focus on building comprehensive sexual well-being while addressing challenges and barriers to healthy sex and sexuality, including HIV risk behavior and risk cofactors.20 Applied to HIV prevention for MSM, this model is designed to promote long-term sexual health and responsible sexual behavior by reducing internalized homonegativity, denial, and/or minimization of sexuality.

Since the 1970’s, this model had been found effective in promoting informed and healthy sexual attitudes among medical students, clergy and the general public.23 Seminars that implement this model are typically conducted as a 2-day curriculum using lectures, panel presentations, videos, music, exercises, and small-group discussions.24 Seminars encourage a sexually pluralistic and sex-positive focus to foster comprehensive sexuality education. Key characteristics of these seminars include the explicitness of the materials and language used. These are gradually introduced using principles of systematic desensitization to facilitate open, frank and explicit discussion about sexuality.25 Therefore, we followed these established guidelines to create two sexual health seminars: one for all MSM regardless of serostatus and a matching one tailored for HIV+MSM.

In 1993, our team developed the Man2Man Sexual Health Seminars as a comprehensive sexual health intervention for MSM. In 1997–2000, we conducted a randomized controlled trial of Man2Man – called the 500 Men’s Study – for mainly HIV-negative MSM (HIV MSM).26 The goal was to test the sexual health approach as an HIV prevention intervention. At twelve-month follow-up, MSM in the contrast arm reported a 29% decrease in condom use during anal intercourse, compared with an 8% increase among men in the intervention arm. (t=2.55; p=0.015). However, high drop-out rates were a concern. We concluded that sexual health seminars appear a promising “next generation” approach to reducing long-term HIV risk behavior in this population. For this study, we created an equivalent intervention, using matching methods and content, but tailored to address HIV prevention and sexual health specifically from an HIV+MSM’s perspective.

The Positive Connections study tested two hypotheses to improve prevention for HIV+MSM: 1) we hypothesized that a sexual health approach can achieve better results in reducing high-risk behavior among HIV+MSM than a video-based HIV prevention intervention; and 2) we hypothesized that interventions which target HIV+MSM exclusively are more effective in reducing high-risk behaviors of HIV+MSM than HIV prevention interventions designed for all MSM.

Methods

Study Participants

Study participants were 675 HIV+MSM recruited between January, 2005 and April, 2006. Participants were recruited in Seattle, WA (n=114); Washington, D.C. (n=71); Boston, MA (n=64); New York, NY (n=177); Los Angeles, CA (n=146); and Houston, TX (n=103). Inclusion criteria included being male, 18 years or older, self-identified as HIV-positive, reporting at least one occasion of unprotected anal intercourse (UAI) with a man in the past year, English speaking, and available to attend both days of the weekend trial. Men were excluded if medical reasons or intoxication prevented them from active participation in the study. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the University of Minnesota and community sites, and participants provided written informed consent.

Procedures

Participants were recruited, screened, and enrolled by partner AIDS Service Organizations in each city through advertising in local gay publications, passing out flyers in popular gay neighborhoods, and placing posters in venues frequented by local MSM. These agencies also advertised the study on their websites and recruited through well-known local HIV/AIDS and STD clinics.

Before the day of the trial, registered MSM were randomized to a study condition using a computer algorithm. Walk-in enrollees were assigned sequentially to available openings in study arms. In all, 675 HIV+MSM (237 in Positive Sexual Health, 248 in Man2Man, and 190 in Men Speaking Out) were enrolled in the trial. After providing written consent, these participants completed a 19-page, 163-item baseline survey. All instruments were self-report pencil and paper inventories. Finally, participants were given color-coded name tags and key chains (yellow, blue, orange) corresponding to the intervention arm to which they had been assigned, and directed to the room where their intervention would take place. Door monitors only permitted participants with the matching color to enter the room. Breaks during the interventions were staggered to minimize contact between participants in different interventions. Participants needed to attend 85% or more of the intervention to be considered adequately “dosed” to be retained in the study.

At the end of each intervention, participants completed post-test surveys. As in the 500 Men’s Study, the survey measured safer sex intentions, evaluation of the seminar components, sexual comfort, internalized homonegativity, safer sex commitment, condom self-efficacy, and treatment optimism. Upon completion of both the pre- and post-test surveys, participants received $100 in cash.

Six, 12, and 18 months after the intervention, participants were mailed follow-up surveys. To promote retention, all participants were contacted via phone two weeks prior to each mailing. Subjects received $25 for completing each follow-up survey, and a $25 bonus after completing all surveys. For participants who did not return their forms, a standardized follow-up protocol was initiated. This involved email and alternate phone contacts, phoning two contacts (in case of lost address), reminder cards and duplicate forms.

Interventions

Man2Man (M2M)

The M2M Sexual Health Seminar is a one-weekend, 14- to 16-hour structured intervention designed to help MSM identify and address their sexual health and HIV risk concerns. Topics included sexual communication, components of sexual identity; stages of coming out; barriers to healthy sexuality including abuse, neglect, heterosexism, compulsivity, and victimization and strategies for recovery; intimacy, dating and relationships; responsible sexuality including examination of sexual attitudes, boundaries, assertiveness and how these impact sexual decision-making; sexual expression; sex functioning and dysfunction; HIV and STDs; safer sex; personal HIV risk assessment and sexual decision-making; sexuality and spirituality; mental and emotional health; and the importance of a positive appreciation of one’s own and others’ sexuality.

M2M uses a large-group format involving multimedia presentations, DVD clips, discussions, behavioral modeling, storytelling, assessments, group and dyad exercises, supplemented by facilitated small group discussions. To provide modeling and expert credibility, large-group presentations and small group discussions are facilitated by MSM-identified health professionals. Approximately 40 HIV+MSM participants were assigned to this condition in each epicenter. In addition, 40 HIV-negative or untested MSM were also recruited and pre-assigned to M2M, to ensure that at every trial, at least 50% of MSM in this arm were HIV-negative or untested. Thus, approximately 80 men in each city were enrolled in this condition. (While the non-HIV+MSM participated in all aspects of the study, only the data on HIV+MSM is reported here to validly compare the effects of the interventions on HIV+MSM’s risk behavior.)

Positive Sexual Health (PoSH)

PoSH was modeled on M2M, but designed to address HIV risk from an HIV+MSM’s perspective. The major differences in PoSH from the M2M curriculum included: 1) the content on sexual health was re-written to address HIV risk from the perspective of an HIV+MSM; 2) as a tailored intervention, all participants and group leaders in this intervention were identified as HIV+MSM; and 3) some new exercises on specific challenges for HIV+MSM (e.g., serodisclosure, and sex and relational health) replaced exercises in the M2M seminar 37. Like M2M, PoSH used a large- and small-group format. Approximately 40 participants were assigned to this condition at each epicenter.

Men Speaking Out (MSO)

The men in this contrast group were asked to participate in a 3-hour group session where they evaluated six HIV prevention DVDs tailored for MSM. As in the 500 Men’s Study, this video condition was designed to: 1) provide all study participants with information about safer sex; and 2) mirror the media format used in the other two seminars. Unlike the DVDs in the intervention arms, the contrast group scenarios were dramatic presentations focused on HIV prevention, condom use, and serodisclosure. There were no sexually explicit DVDs, no exercises to help participants contextualize information, no large or small group discussions, and group interaction was kept to a minimum. While null control conditions provide a purer test of the effects of an intervention, in this case we considered a contrast condition was ethically necessary to provide HIV+ men engaging in risk with detailed information on HIV risk reduction. After watching each DVD, participants completed a 30-item survey evaluating the degree to which the video was interesting, relevant, and helpful. Approximately 40 participants were assigned to this condition in each epicenter.

Measures

Serodiscordant Unprotected Anal Intercourse (SDUAI)

The dependent variable was defined as any unprotected anal sex with a partner of negative or unknown HIV infection status during the last three months.27, 28 This measure asked about insertive and receptive anal sex with primary and secondary partners, and was calculated from items developed for this study. Within these two categories, information was collected on partners who are HIV-positive, HIV-negative, or of unknown infection status. The frequency of unsafe intercourse was calculated by first summing the number of acts of unprotected anal sex with primary partners who were of unknown or negative HIV infection status, and the number of acts of unprotected anal sex with secondary partners who were of unknown or negative HIV status. We chose to define our unsafe measure in this manner so we could control for sero-sorting and other potentially effective strategies for limiting transmission of HIV.29

Demographics

Demographic variables included age, race/ethnicity, education level, employment status, income, and sexual orientation.

Sexual Comfort

This is a 6-item four-point Likert scale that measures comfort with sexuality and one’s body.30 High scores indicate more sexual comfort. Cronbach’s α = 0.83 in this sample.

Condom Self-efficacy

This is a 14-item five-point Likert scale that measures self-efficacy with respect to using condoms in multiple situations and settings.30 High scores indicate more self-efficacy. Cronbach’s α = 0.95 in this sample.

HIV Prevention Altruism

This is a 7-item five-point Likert-type scale that measures level of altruistic motivations toward prevention of HIV transmission.31 Higher scores indicate a higher level of HIV prevention altruism. Cronbach’s α = 0.91 in this sample.

Internalized Homonegativity

This is a 4-item, seven-point Likert-types scale that measures participants’ acceptance of negative views about their own homosexuality.32 Higher scores indicate a higher level of internalized homonegativity. Cronbach’s α = 0.88 in this sample.

Intention to Practice Safer Sex

These three questions were designed for this study and do not form a scale. Each measures participants’ intent to engage in safer-sex practices. All are 7-point Likert items, ranging from “Not at all likely” to “Very likely”. They are:

The next time you have sex with someone, how likely are you to tell this person your HIV-status?

The next time you have sex with someone, how likely are you to bring up the need to practice safer sex?

The next time you have sex with someone, how likely are you to refuse to have unsafe sex even if your partner pressures you to be unsafe?

Sexual Health Estimate

The question, designed for this study, measure participants’ sexual health – defined as “an approach to sexuality that is founded on accurate knowledge, with deep self-awareness, self-respect, and self-acceptance of my sexuality, sexual behaviors, desires, and values. Because sex is also a social behavior, it also implies a deep respect for other’s sexualities, values and differences.” It is a 7-point Likert item, ranging from “Minimum sexual health” to “Maximum sexual health”. It asks: “Please estimate your sexual health on the following scale, in the last 3 months”.

Statistical Analysis

Only the data on the 675 HIV+MSM participants were included in this analysis. Analysis of SDUAI is complicated by the non-normal distribution of the variable and large number of participants with SDUAI scores of 0. In order to analyze intervention effects on SDUAI, it was necessary to model observed SDUAI counts, which was done by assuming that count values came from a Poisson distribution. To account for the observed extra-Poisson variation, we further supposed that the Poisson mean was drawn from a lognormal distribution, with first parameter determined by a linear combination of the predictors. These data were analyzed using a hierarchical Poisson-lognormal regression with simple dummy coding for both intervention and time point predictors. MSO was the reference group for the intervention dummy variables (M2M, PoSH), and Baseline was the reference group for the time point dummy variables (6-month, 12-month, and 18-month). Random effects, αi, accounted for intra-subject correlation.33 We fitted the model using WinBUGS v 1.41.

The Sexual Health Model posits that greater sexual well-being can be obtained by modifying the psychosocial variables that make up the sexual health construct, namely: safer sex intentions, sexual health estimate, sexual comfort, internalized homonegativity, altruism, and condom self-efficacy. These variables were collected as mediators of the association between intervention arm and SDUAI. Results were examined using Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test on the three arms simultaneously, followed by post-hoc pair-wise comparisons where appropriate (Wilcoxon rank sum).

Results

Participants

Table 1 lists the proportion of general demographic and health characteristics across intervention arms for HIV+MSM participants. No significant differences on demographic and health characteristics were noted between interventions. Over 80% (n=536) of the participants were over 35 years of age. The sample included mostly men of color (n=501, 75%), most notably African-Americans (n=300, 45%). Level of education was fairly high, with 60% (n=405) of the men reporting at least some college. Only 27% (n=185) were employed, and nearly half the men were on disability (n=322, 48%). Annual income was relatively low with 50% (n=275) reporting less than $10,000 per year. Participants reported being HIV-positive for an average of 12 years (SD=6.2), and 77% (n=514) indicated current use of antiretroviral therapy. One-half of the men in the sample reported an undetectable viral load at their most recent medical visit (n=321, 50%). However, a notable number did not know their viral load or never had it measured (n=109, 17%). The percentage reporting a CD-4 count below 200, and thus, meeting diagnostic criterion for AIDS, was 11% (n=70).

Table I.

Demographic and health characteristics of HIV+MSM participants at baseline (N = 675)

| MSO | M2M | PoSH | Pearson’s χ2 | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| n (col %) | n (col %) | n (col %) | |||

| Age (in years) | 7.20 | 0.30 | |||

|

| |||||

| 18 – 25 | 3 (1.6) | 7 (2.9) | 7 (3.0) | ||

| 26 – 35 | 29 (15.3) | 49 (20.2) | 35 (14.9) | ||

| 36 – 45 | 91 (48.1) | 121 (50.0) | 109 (46.4) | ||

| Older than 45 | 66 (34.9) | 65 (26.9) | 84 (35.7) | ||

|

| |||||

| Race/Ethnicity | 3.53 | 0.74 | |||

|

| |||||

| African-American/Black | 85 (44.7) | 111 (44.9) | 104 (44.8) | ||

| Caucasian/White | 42 (22.1) | 61 (24.7) | 65 (28.0) | ||

| Latino/Spanish/Hispanic | 47 (24.7) | 59 (23.9) | 51 (22.0) | ||

| Other | 16 (8.4) | 16 (6.5) | 12 (5.2) | ||

|

| |||||

| Sexual Orientation | 1.37 | 0.50 | |||

|

| |||||

| Homosexual/Gay/Same Gender Loving | 149 (80.1) | 197 (82.1) | 182 (77.8) | ||

| Other | 37 (19.9) | 43 (17.9) | 52 (22.2) | ||

|

| |||||

| Years of Education | 1.65 | 0.44 | |||

|

| |||||

| High school graduate or less | 68 (36.0) | 103 (41.7) | 97 (40.9) | ||

| At least some college | 121 (64.0) | 144 (58.3) | 140 (59.1) | ||

|

| |||||

| Employment Status | 1.90 | 0.75 | |||

|

| |||||

| Employed | 57 (30.0) | 67 (27.1) | 61 (25.7) | ||

| On Disability | 91 (47.9) | 114 (46.2) | 117 (49.4) | ||

| Other (student, retired, etc.) | 42 (22.1) | 66 (26.7) | 59 (24.9) | ||

|

| |||||

| Annual Income | 6.25 | 0.40 | |||

|

| |||||

| Less than $10,000 | 87 (53.0) | 103 (52.3) | 85 (44.7) | ||

| $10 – 19,999 | 29 (17.7) | 39 (19.8) | 47 (24.7) | ||

| $20 – 29,999 | 19 (11.6) | 23 (11.7) | 17 (8.9) | ||

| $30,000 and over | 29 (17.7) | 32 (16.2) | 41 (21.6) | ||

|

| |||||

| Currently on Antiretroviral medications | 3.51 | 0.48 | |||

|

| |||||

| Yes | 152 (81.3) | 184 (75.1) | 178 (76.4) | ||

| No | 33 (17.6) | 55 (22.4) | 52 (22.3) | ||

| Don’t know | 2 (1.1) | 6 (2.4) | 3 (1.3) | ||

|

| |||||

| Viral Load | 4.71 | 0.79 | |||

|

| |||||

| Undetectable (≤ 50 copies/μl) | 91 (50.0) | 123 (52.1) | 107 (47.1) | ||

| 51 – 10,000 copies/μl | 33 (18.1) | 50 (21.2) | 43 (18.9) | ||

| 10,001 – 100,000 copies/μl | 18 (9.9) | 26 (11.0) | 26 (11.5) | ||

| Over 100,000 copes/μl | 6 (3.3) | 5 (2.1) | 8 (3.5) | ||

| Do not know / Never measured | 34 (18.7) | 32 (13.6) | 43 (18.9) | ||

|

| |||||

| CD4+ count | 10.04 | 0.12 | |||

|

| |||||

| ≤ 200 | 16 (8.8) | 18 (7.6) | 36 (15.9) | ||

| 201 – 349 | 38 (21.0) | 50 (21.2) | 40 (17.6) | ||

| 350 and over | 96 (53.0) | 133 (56.4) | 116 (51.1) | ||

| Do not know / Never measured | 31 (17.1) | 35 (14.8) | 35 (15.4) | ||

|

| |||||

| Had an STI within past 3 months | 4.09 | 0.13 | |||

|

| |||||

| Yes | 22 (11.9) | 15 (6.3) | 23 (f9.9) | ||

| No | 163 (88.1) | 222 (93.7) | 209 (90.1) | ||

|

| |||||

| Currently has a primary partner | 0.28 | 0.87 | |||

|

| |||||

| Yes | 89 (46.8) | 116 (46.8) | 115 (48.9) | ||

| No | 101 (53.2) | 132 (53.2) | 120 (51.1) | ||

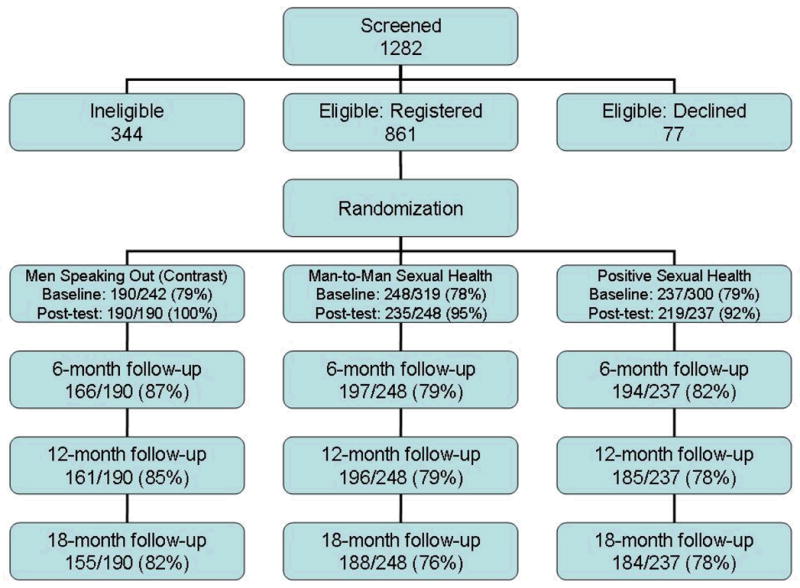

Retention

Figure 1 reports overall recruitment and retention of HIV+MSM participants by intervention arm. After completing data collection, we observed differential retention by baseline risk and intervention arm. Those who were randomized to PoSH and reported higher frequency of SDUAI at baseline were significantly less likely to complete subsequent follow-up surveys. At 18-months, we retained 71% of PoSH participants with baseline SDUAI, compared to 75% of MSO participants and 79% of M2M participants.

Figure I.

Flow diagram of the Positive Connections trial and participation rates for HIV+MSM participants only – overall recruitment and retention by intervention arm.

Immediate Outcomes

We conducted a longitudinal cohort analysis to compare the effects of the three intervention arms in reducing SDUAI frequency. In the M2M arm, 45% reported SDUAI at baseline, in PoSH, 40%, and in MSO, 48%. These proportions were not statistically different. At the end of the follow-up period, all three arms registered a significant overall decrease in reported frequency of SDUAI acts, from 15.0 to 11.5. However, there was no significant difference between the three arms throughout the 18 months.

Most psychosocial variables targeted by PoSH and M2M did not vary significantly across arms over time. The only significant difference was on safer sex intentions immediately after the intervention. HIV+MSM participants in the PoSH and M2M interventions reported significantly higher rates in their intention to avoid high-risk sexual behaviors, compared to participants in the MSO arm (see Table 2).

Table II.

Immediate Post-Seminar Evaluation of the Psychosocial Variables

| Psychosocial Variables | MSO

|

M2M

|

PoSH

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Seminar | Post-Seminar | Pre-Seminar | Post-Seminar | Pre-Seminar | Post-Seminar | |

|

|

|

|

||||

| Median (p25,p75) | Median (p25,p75) | Median (p25,p75) | Median (p25,p75) | Median (p25,p75) | Median (p25,p75) | |

| Safer sex intentions a (range: 3 to 21) | 15.0 (12,20) | 17.0 (15,20) | 15.0 (12,19) | 18.0 (15,21) | 15.0 (12,19) | 18.0 (15,21) |

|

| ||||||

| Sexual health estimate (range: 1 to 7) | 5.0 (4,6) | 6.0 (5,7) | 5.0 (4,7) | 6.0 (4,7) | 5.0 (4,6) | 6.0 (4,6) |

|

| ||||||

| Sexual comfort (range: 6 to 24) | 22.0 (18,24) | 22.0 (19,24) | 22.0 (18,24) | 23.0 (20,24) | 22.0 (20,24) | 23.0 (20,24) |

|

| ||||||

| Internalized homonegativity (range: 4 to 28) | 7.0 (4,14) | 8.0 (4,12) | 7.0 (4,13) | 6.0 (4,14) | 7.0 (4,12) | 5.0 (4,11) |

|

| ||||||

| Altruism (range: 7 to 35) | 32.0 (25,35) | 33.0 (28,35) | 31.0 (26,35) | 34.0 (30,35) | 31.0 (26,34) | 34.0 (29,35) |

|

| ||||||

| Condom self-efficacy (range: 15 to 75) | 62.0 (50,71) | 68.0 (53,75) | 62.0 (48,72) | 68.0 (58,74) | 63.0 (50,73) | 66.5 (56,73) |

Change from pre-seminar to post-seminar in PoSH and M2M arms significantly different from MSO arm (z-statistic = 2.24, p = .025; and z-statistic = 3.65, p = .0003; respectively)

Longitudinal Analysis of Intervention Efficacy

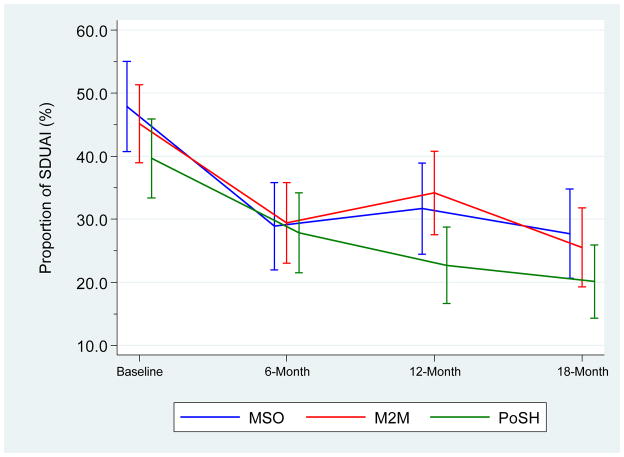

Posterior parameters for HIV+MSM participants were estimated from the hierarchical Poisson-lognormal mixed regression of SDUAI. Significance of the regression parameters was determined by examining the .025 and .975 quartiles of the posterior distribution of each parameter. Thus, a 95% credible interval was obtained. The proportion of men reporting any SDUAI, by intervention, is reported in Figure 2. Table 3 reports the raw mean counts and proportions of the SDUAI variable from baseline to the 18-month follow-up time point. The predicted mean SDUAI count and median by intervention arm and time point is reported in Table 4. The main effect parameters for follow-up time (6, 12, and 18 months) are significant and negative, indicating decreasing levels of risk behavior at the three time points. The PoSH treatment interaction with 6 months was significant and positive, suggesting the decline in SDUAI at the 6-month follow-up was less than the decline in risk among MSO participants. None of the remaining intervention main effects or interaction terms reached significance.

Figure II.

Proportion (and 95% confidence intervals) of Men Reporting any SDUAI, by Intervention

Table III.

Raw mean counts and proportions of the SDUAI variable from baseline to the 18-month follow-up time point

| Visit | MSO (contrast) | M2M (general) | PoSH (tailored) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Proportion reporting no SDUAI

| |||

| Baseline – prop. (95% CI) | 0.51 [0.44–0.58] | 0.54 [0.47–0.60] | 0.59 [0.52–0.65] |

| 6-month | 0.71 [0.64–0.78] | 0.69 [0.63–0.76] | 0.73 [0.67–0.80] |

| 12-month | 0.66 [0.59–0.74] | 0.65 [0.58–0.72] | 0.77 [0.71–0.83] |

| 18-month | 0.72 [0.65–0.79] | 0.73 [0.67–0.80] | 0.78 [0.72–0.85] |

|

| |||

|

SDUAI frequency among those reporting any SDUAI

| |||

| Baseline – mean | 11.7 | 7.9 | 15.0 |

| 6-month | 9.2 | 10.6 | 11.5 |

| 12-month | 6.9 | 9.8 | 12.2 |

| 18-month | 12.4 | 14.6 | 11.5 |

Note: values for whom complete data are available

Table IV.

Predicted mean SDUAI count (with standard deviation), and median (with 95% credible intervals) by intervention arm and time point.

| Mean | Standard Deviation | 2.5% | Median | 97.5% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −0.69 | 0.27 | −1.25 | −0.68 | −0.18 |

| 6 months | −1.35 | 0.29 | −1.92 | −1.35 | −0.79 |

| 12 months | −1.04 | 0.29 | −1.60 | −1.04 | −0.47 |

| 18 months | −1.27 | 0.30 | −1.88 | −1.26 | −0.70 |

| M2M | −0.43 | 0.32 | −1.08 | −0.43 | 0.19 |

| PoSH | −0.58 | 0.33 | −1.22 | −0.58 | 0.08 |

| 6 months * M2M | 0.63 | 0.39 | −0.15 | 0.63 | 1.38 |

| 12 months * M2M | 0.41 | 0.39 | −0.37 | 0.41 | 1.17 |

| 18 months * M2M | 0.15 | 0.41 | −0.64 | 0.14 | 0.96 |

| 6 months * PoSH | 0.47 | 0.40 | −0.33 | 0.47 | 1.24 |

| 12 months * PoSH | −0.19 | 0.41 | −0.99 | −0.20 | 0.61 |

| 18 months * PoSH | 0.01 | 0.42 | −0.81 | 0.00 | 0.83 |

Discussion

This study explored the relative effects of the Positive Sexual Health (PoSH) and Man2Man (M2M) intervention arms on the high-risk sexual behaviors of HIV+MSM. There were four major findings. First, the scores on the sexual health variables were high in this sample of high risk HIV+ men. Second, across time, we also found substantial reductions (by about half) in reported risk behavior. Third, the sexual health interventions resulted in short term change in behavioral intentions. Fourth, the sexual health interventions did not differentially affect SDUAI.

Between baseline and 6-months, the PoSH arm reported a significant decrease in risk behavior compared to the other two interventions. However, we did not observe differences across our three intervention arms on SDUAI at 12-month and 18-month follow-up time points. For our two hypotheses, we conclude that: 1) we found no evidence that a sexual health approach achieves better reduction in unsafe sex among HIV+MSM than a traditional HIV prevention approach; and 2) we found no evidence that tailored interventions are more or less effective than non-tailored interventions for targeting HIV+MSM.

Our interventions targeted those psychosocial variables deemed important from the perspective of a Sexual Health Model,21 namely: safer sex intentions, sexual comfort, safer sex altruism, internalized homonegativity, condom use self-efficacy, and a global rating of sexual health. Our sexual health intervention arms did have significant effects on behavioral intentions. However, these differential changes were of very small magnitude. Post-test measures of the remaining psychosocial variables showed no differential changes across the three study arms. Indeed, they were high at baseline and remained stable across time in all three groups. This lack of difference across time and intervention arms may be explained by our recruitment strategy. We did not screen participants on these psychosocial variables and, as a result, we appear to have admitted to the study a sample that self-reported excellent sexual heath at baseline. Such high initial estimates made any improvement on these variables difficult to measure both prospectively and between intervention arms.

Taken at face value, it would seem that this sample of HIV+MSM does not experience sexual health issues such as homonegativity or lack of sexual comfort, despite reporting high levels of sexual abuse34 and engaging in rather high levels of SDUAI at baseline. Furthermore, participants reported adequate levels of safer sex altruism, which is a measure of willingness to avoid unsafe sex to protect others rather than for self-interest,31 and condom use self-efficacy - the belief that they have the behavioral repertoire to use condoms in different situations.30 Therefore, in this sample, it may be that interventions based on the sexual health model do not address the issues supporting unsafe sexual behavior.

The significant decrease in risk behavior reported in PoSH compared to the other two interventions may be due to the fact that participants who reported higher SDUAI at baseline were more likely to drop out during follow-up. The reasons for this differential drop out remain unclear.

Our data have important similarities and differences to the two other trials which have exclusively targeted HIV+MSM. The SUMIT trial also tested a group intervention against a contrast condition, used similar measures, and also did not find differential change between treatment and comparison conditions. Unlike SUMIT, our sample of HIV+MSM registered substantial reduction in reported sexual risk behavior where SUMIT found minimal change. It may be that all the interventions in our study were equally effective. We advise future research in this area to avoid contrast conditions in favor of pure null controls. The Health Living Project trial used a far more intensive individual-based intervention (22.5 hours over several months), compared this with a waitlist null control, and employed partner-by-partner risk assessment measures, did observe short-term risk reduction. We recommend other researchers consider ACASI interview assessments as they appear more precise. Both SUMIT and Healthy Living reported higher drop out rates in their intervention arms than we experienced, which likely reflects the logistical advantage of running 16-hour interventions in a single weekend versus weekly meetings. Regarding the drop out for PoSH, we conclude that, for a substantial number of HIV+MSM engaging in highest risk, confronting risk behavior in a HIV+MSM-only group context is not productive, since it leads to non-participation. We recommend that future research investigates the reasons that HIV+MSM drop out of HIV prevention intervention trials. In evaluating HIV prevention services for this population, we recommend future research compare retention of HIV+MSM participants across individual, group and tailored group interventions.

The lack of differences found across treatment arms are in contrast to those previously reported by our team in a study of mostly HIV-negative MSM,26 which also tested the M2M intervention against the same contrast condition. However, our results mirror those reported in the SUMIT and Healthy Living Project trials. Two explanations are probable. First, interventions demonstrated effective for HIV MSM may simply not work as well for HIV+MSM. There is less inherent benefit from condom use among HIV+MSM, and potentially greater risk of confrontation and questioning of serostatus. Others have argued that differing motivation (self-protection versus altruism) may be critical in designing effective programs.35 Alternatively, if time is the dominant differential variable, interventions that were tested and found effective in the pre-HAART era may not work as well now – if at all. Future research should confirm the efficacy of HIV prevention interventions in the post-HAART era.

The Positive Connections trial had several limitations. First, the lack of a true control condition does not allow for an assessment of PoSH or M2M’s net treatment effects. Second, the study sample recruited is not representative of HIV+MSM in the participating cities or nationally. Eligibility criteria were established to enroll a high-risk and racially-diverse seropositive population. Both are limitations on generalizability. Third, as HIV prevention research evolves, the amount of information required from participants to assess risk behavior becomes very complex. In our study, the burden of completing the risk assessment instrument was significant, especially for men with low literacy. Fourth, we considered whether our dependent variable (SDUAI), which combines serostatus and risk behavior variables, may have been difficult to interpret. Therefore, we ran separate analyses for risk behavior alone. We confirm that, in contrast to the Healthy Living Project, our conclusions do not vary according to SDUAI or UAI. Fifth, in spite of an overall good retention rate, we retained fewer men who were engaging in unsafe sex at baseline than those who were not. The attrition rate was highest in the PoSH group. At least one study of HIV–MSM reported similar challenges in differential attrition across arms in the higher risk subgroups.17 A final issue is difficulties in sexual health measures. The ceiling effects in our psychometric measures at baseline increased the difficulty of finding significant changes within or across arms. It is possible that participants already had excellent sexual health to begin with, that significant social desirability bias skewed results, or that halo effects, where participants see themselves as more healthy and efficacious than they actually are, influenced participants’ self-ratings.

In the post-HAART treatment era, many people consider HIV prevention as less of a priority, than before the development of effective treatment.36 This may be especially true for HIV+MSM. Our trial produced a complex picture: on the one hand, group level behavioral interventions may decrease by half the high-risk behavior frequency of HIV+MSM. On the other hand, we failed to find evidence that group level interventions for HIV+MSM are effective, at least when compared to a contrast condition. We propose that HIV prevention researchers explore new and different interventions to address the long-term prevention needs of HIV+MSM. In the interim, we recommend that AIDS Service Organizations provide both general and targeted interventions for HIV+MSM, noting especially dropout rates between the interventions.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health, Office on AIDS Research, grant #MH064412 and conducted as a community-based participatory research trial. The Positive Connections Team comprises faculty and staff at the University of Minnesota, consultants from AIDS Service Organizations and other universities who provided specialist guidance and direction, and a national leadership team of HIV-positive gay and bisexual men who partnered with this project at every stage from conceptualization to submission of findings. As a multi-site trial, this study was conducted under the oversight of the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board (IRB), study # 0302S43321, and five other community-based IRBs. We acknowledge with gratitude our community-based partners: Howard Brown Health Center, Chicago, IL; Gay City Health Project, Seattle, WA; Whitman Walker Clinic, Washington, DC; Fenway Community Health Center, Boston, MA; Gay Men’s Health Crisis, New York, NY; AIDS Project Los Angeles and Black AIDS Institute, Los Angeles, CA; and Legacy Community Health Services, Houston, TX. In addition, we gratefully acknowledge the Positive Connections’ team of researchers, community consultants and staff who together made the study possible. Research investigators and consultants who helped design and refine the study included Drs. George Ayala, David Brennan, Alex Carballo-Dieguez, Eli Coleman, Michael Crosby, Keith Horvath, Ken Mayer, John L. Peterson, Beatrice “Bean” Robinson, Michael W. Ross, and Frank Wong. Community Consultants who designed the PoSH intervention and provided input on the target population included Jimmy Alvarez, Cornelius Baker, Kip Beardsley, Keith Bussey†, Jeffrey Kiesling, Nick Metcalf, J. E. Miles, Eduardo Parra, Antony Stately, Tim Vincent, Luis Viquez, Glenn Williams†, and Phill Wilson. Staff from AIDS Service Organizations who conducted the trial, recruited participants and/or led the seminars included Anthony Amado, Dane Ballard, Mary Bahr, Robert Bank, Scott Berlin, David Bucher, Twanna Clark, Leo Colemon, Weston Edwards, Mike Fredrickson, Jay Fournier, Roberta Geidner-Antoniotti, Laura Horwitz, Cory Johnson, Michael Kaplan, Andy Litsky, Edward Liu, Tara McKay, Bruce Maeden, Annie Mejia, Lauren Metoyer, Anthony Morgan, Jason Nelson, Aaron Norton, Benjamin Perkins, Chris Powers, Wendy Reservitz, Nestor Rocha, Eric Roland, Carl Sciortino, Kevin Sitter, Alex Solange, Fred Swanson, and Rodney Van Derwarker. University of Minnesota staff who implemented this project included the project coordinator Scott Jacoby and research assistants Brennan O’Dell, Stephanie Purkat, Tina Dickenson and Anne Cain-Nielsen. This paper is dedicated to two of our consultants, Keith Bussey and Glenn Williams, and at least 13 participants who died of AIDS during this trial.

Contributor Information

B. R. Simon Rosser, Email: rosser@umn.edu, Division of Epidemiology and Community Health, University of Minnesota, 300 WBOB, 1300 S. 2ndSt., Minneapolis, MN 55454.

Laura A. Hatfield, Email: hatfield@umn.edu, Program in Human Sexuality, University of Minnesota, 180 WBOB, 1300 S. 2ndSt., Minneapolis, MN 55454.

Michael H. Miner, Email: miner001@umn.edu, Program in Human Sexuality, University of Minnesota, 180 WBOB, 1300 S. 2ndSt., Minneapolis, MN 55454.

Margherita E. Ghiselli, Email: ghise001@umn.edu, Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy, University of Minnesota, MMC 263, 420 Delaware St. SE, Minneapolis, MN 55455.

Brian R. Lee, Email: leex1412@umn.edu, Division of Health Management and Policy, University of Minnesota, MMC 729, 420 Delaware St. SE, Minneapolis, MN 55455.

Seth L. Welles, Email: slwelles@bu.edu, Dept. of Epidemiology, Boston University School of Public Health, 715 Albany Street, 3TE, Boston, MA 02118

References

- Bell A, Weinberg M. Homosexualities: A study of diversity among men and women. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Buchacz K, Greenberg A, Onorato I, Janssen RS. Syphilis epidemics and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) incidence among men who have sex with men in the United States: Implications for HIV prevention. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2005;32(10):S73–S79. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000180466.62579.4b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullough VL. Science in the bedroom: a history of sex research. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Carballo-Diéguez A, Dolezal C, Leu C-S, et al. A randomized controlled trial to test an HIV-prevention intervention for Latino gay and bisexual men: Lessons learned. AIDS Care. 2005;17(3):314–328. doi: 10.1080/09540120512331314303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV/AIDS and Men who have Sex with Men (MSM) Vol. 2008. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report, 2006. Vol. 18. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. No turning back. CDC; Atlanta, GA: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Resurgent bacterial sexually transmitted disease among men who have sex with men - King County, Washington, 1997–1999. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 1999;48:773–777. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleary PD, Van Devanter N, Steilen M, et al. A randomized controlled trial of an education and support program for HIV-infected individuals. Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 1995;9:1271–1278. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199511000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crepaz N, Lyles CM, Wolitski RJ, et al. Do prevention interventions reduce HIV risk behaviours among people living with HIV? A meta-analytic review of controlled trials. AIDS. 2005;20:143–157. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000196166.48518.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elford J, Bolding G, Sherr L. HIV optimism: fact or fiction? FOCUS. 2001;8:1–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenton KA, Imrie J. Increasing rates of sexually transmitted diseases in homosexual men in Western Europe and the United States: Why? Infectious Disease Clinics of North America. 2005;19:311–331. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden M, Brewer D, Kurth A, Holmes K, Handsfield H. Importance of sex partner HIV status in HIV risk assessment among men who have sex with men. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2004;36(2):734–742. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200406010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Held JP, Cournoyer CR, Held CA, Chilgren RA. Sexual attitude reassessment: a training seminar for health professionals. Minnesota Medicine. 1974;57(11):925–928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbst JH, Beeker C, Mathew A, et al. The effectiveness of individual-, group-, and community-level HIV behavioral risk-reduction interventions for adult men who have sex with men: a systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2007;32:S38–S67. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BT, Carey MP, Chaudoir SR, Reid AE. Sexual risk reduction for persons living with HIV: Research synthesis of randomized controlled trials, 1993 to 2004. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2006;41:642–650. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000194495.15309.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Rompa D, Cage M, et al. Effectiveness of an intervention to reduce HIV transmission risks in HIV-positive people. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2001;21(2):84–92. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00324-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord D, Miranda-Moreno LF. Effects of low sample mean values and small sample size on the estimation of the fixed dispersion parameter of Poisson-gamma models for modeling motor vehicle crashes: a Bayesian perspective. Safety Science. 2008;46:751–770. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin BV, Gomez CA, Tschann JM, Gregorich SE. Condom use in unmarried Latino men: A test of cultural constructs. Health Psychology. 1997;16(5):458–467. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.16.5.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miner MH, et al. Improving safer sex measures through the inclusion of relationship and partner characteristics. AIDS Care. 2002;4:827–837. doi: 10.1080/0954012021000031895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin S, Shade SB, Steward WT, et al. A behavioral intervention reduces HIV transmission risk by promoting sustained serosorting practices among HIV-infected Men who have Sex with Men. Journal of the Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2008;49(5):544–551. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31818d5def. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimmons D, Nimmons D. In this together: the limits of prevention based on self-interest and the role of altruism in HIV safety. Journal of Psychology and Human Sexuality. 1998;10:108–126. [Google Scholar]

- O’Dell BL, Rosser BRS, Miner MH, Jacoby SM. HIV Prevention altruism and sexual risk behavior in HIV-positive Men who have Sex with Men. AIDS & Behavior. 2008 doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9321-9. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson TL, Shaw WS, Semple SJ. Reducing the sexual risk behaviors of HIV+ individuals: Outcome of a randomized controlled trial. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2003;25(2):137–145. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2502_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawstorne P, Fogarty A, Crawford J, et al. Differences between HIV-positive gay men who ‘frequently’, ‘sometimes’ or ‘never’ engage in unprotected anal intercourse with serononconcordant casual partners: positive Health cohort, Australia. AIDS Care. 2007;19(4):514–522. doi: 10.1080/09540120701214961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson JL, Milam J, McCutchan A, et al. Effects of brief safer-sex counseling by medical providers to HIV-1 seropositive patients: A multi-clinic assessment. Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2004;18:1179–1186. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200405210-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson BE, Bockting WO, Rosser BRS, Rugg DL, Miner M, Coleman E. A sexological approach to HIV prevention: The sexual health model. Health Education Research. 2002;17:43–57. doi: 10.1093/her/17.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosser BRS, Bockting WO, Rugg DL, et al. A randomized controlled intervention trial of a sexual health approach to long-term HIV risk reduction for men who have sex with men: Effects of the intervention on unsafe sexual behavior. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2002;14(Supplement A):59–61. doi: 10.1521/aeap.14.4.59.23885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosser BRS, Coleman E, Ohmans P. Safer sex maintenance and reduction of unsafe sex among homosexually active men: A comprehensive therapeutic approach. Health Education Research. 1993;8(1):19–34. doi: 10.1093/her/8.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosser BRS, Dwyer SM, Coleman E, et al. Using sexually explicit material in adult sex education: An eighteen year comparative analysis. Journal of Sex Education and Therapy. 1995;21(2):117–128. [Google Scholar]

- Stryker J, Coates TJ, De Carlo P, Haynes-Sanstad K, Shriver M, Makadon HJ. Prevention of HIV infection: Looking back., looking ahead. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1995;273:1134–1148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdiserri RO. Taking action to combat increases in STDs and HIV risk among men who have sex with men. CDC; Atlanta, GA: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Varga CA, Rosser BRS, Beardsley K. Positive sexual health (PoSH): sexual health curriculum for HIV+ men who have sex with men. Proceedings of the XV International AIDS Conference; Bangkok, Thailand. July 11–16.2004. [Google Scholar]

- Welles SL, Baker C, Miner MH, Brennan DJ, Jacoby S, Rosser BRS. History of childhood sexual abuse and unsafe anal intercourse in HIV+ Men who have Sex with Men. Results from a multi-city HIV prevention trial. American Journal of Public Health. 2008 doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.133280. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolitski RJ, Gomez CA, Parsons JT The SUMIT Study Group. Effects of a peer-led behavioral intervention to reduce HIV transmission and promote serostatus disclosure among HIV-positive gay and bisexual men. Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2005;19:S99–S109. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000167356.94664.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolitski RJ, Valdiserri RO, Denning PH, Levine WC. Are we headed for a resurgence in the HIV epidemic among men who have sex with men? American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91:883–888. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.6.883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolpe J. The systematic desensitization treatment of neuroses. Journal of Nervous Mental Disorders. 1961;132:189–203. doi: 10.1097/00005053-196103000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]