Abstract

Organ-specific adult stem cells are critical for the homeostasis of adult organs and organ repair and regeneration. Unfortunately, it has been difficult to investigate the origins of these stem cells and the mechanisms of their development, especially in mammals. Intestinal remodeling during frog metamorphosis offers a unique opportunity for such studies. During the transition from an herbivorous tadpole to a carnivorous frog, the intestine is completely remodeled with the larval epithelial cells undergo apoptotic degeneration and are replaced by adult epithelial cells developed de novo. The entire metamorphic process is under the control of thyroid hormone, making it possible to control the development of the adult intestinal stem cells. We show here that the thyroid hormone receptor-coactivator PRMT1 (protein arginine methyltransferase 1) is upregulated in a small number of larval epithelial cells and that these cells dedifferentiate to become the adult stem cells. More importantly, transgenic overexpression of PRMT1 leads to increase adult stem cells in the intestine and conversely knocking down the expression of endogenous PRMT1 reduces the adult stem cells. In addition, PRMT1 expression pattern during zebrafish and mouse development suggests that PRMT1 plays an evolutionally conserved role in the development of adult intestinal stem cells throughout vertebrates. These findings are not only important for the understanding of organ-specific adult stem cell development but also have important implications in regenerative medicine of the digestive tract.

Keywords: adult organ-specific stem cell, histone arginine methyltransferase, transcriptional coactivator, thyroid hormone receptor, dedifferentiation

Introduction

Mammalian organ development often involves a two-step process, the formation of an immature but somewhat functional organ during embryogenesis followed by the maturation into the adult form. Often this second step takes place during the so-called post-embryonic development, a period from a few months before to several months after birth in human when plasma thyroid hormone (T3) concentrations are high1. Among the changes during this period include the transition from the fetal to adult hemoglobin to adapt to the air breathing as the lung matures, and the maturation of the brain and the intestine, etc.

The intestine is one of the best-studied organs where self-renewal is an integral part of the physiological function of the organs. In adult mammalian intestine, the complete renewal of the epithelium, the tissue responsible for the primary function of the intestinal tract (the digestion and absorption of nutrients), takes place in about 1–6 days2–4, and in amphibians, this occurs in 2 weeks5. In the mammalian intestine, cell proliferation occurs exclusively by the stem cells located in the crypts. As the cells migrate down to the bottom of the crypt or up along the crypt-villus axis, eventually to the tip of the villus, they gradually differentiated (into the Paneth cells at the bottom of the crypt or other cell types, including the major, absorptive epithelial cells on the villus). The old, differentiated epithelial cells undergo cell death and are sloughed into the lumen after a finite period of time. Such a self-renewal system has been shown to be present throughout vertebrate, from zebrafish, frogs, to human. Furthermore, its establishment in all vertebrates takes place during the postembryonic period, suggesting the existence of a conserved developmental mechanism. While extensive molecular and genetics studies, especially in mouse, have identified a number of signaling pathways required for intestinal development and cell renewal in the adult4, 6, how the adult stem cells are formed during this period and what roles of transcription factors and cofactors play in determining the transcription profiles that specify the stem cells remain unknown. On the other hand, this process appears to be well conserved throughout vertebrates and takes place during the post-embryonic developmental period when plasma T3 concentrations are high. For example, in mammals such as mouse, the intestine changes from an embryonic form to a more complex adult form during this T3-dependent period (around birth) as the crypt-villus axis is established for the self-renewal of the epithelium, similar to the transition taking place in the frog intestine during T3-dependent metamorphosis. Unfortunately, it is difficult to manipulate and study this intestinal transition in mammals as the embryos are enclosed in the uterus.

Intestinal remodeling during amphibian metamorphosis offers a unique opportunity to study the formation and regulation of the adult organ-specific stem cells during the T3-dependent postembryonic period. A major advantage of amphibian metamorphosis is that the adult organs are developed during a process that is totally dependent on T3 and takes place externally7, 8, independent of maternal influence as in the case of mammals. This makes is easy to manipulate and study the development and regulation of the adult organ-specific stem cells. In Xenopus laevis, the tadpole intestine consists of predominantly a monolayer of larval epithelial cells, surrounded by thin connective tissue and muscle layers9. During metamorphosis, the larval epithelial cells undergo apoptosis and concurrently, adult epithelial stem/progenitor cells are derived from the larval epithelium through yet known mechanism and rapidly proliferate9–11. Toward the end of metamorphosis, the adult epithelial cells differentiate to establish a trough-crest axis of epithelial fold, resembling the crypt-villus axis in the adult mammalian intestine9. The connective tissue and muscles develop extensively to become much more abundant and thicker. Despite such complex changes, like all other process during metamorphosis, intestinal remodeling is under the control of T3. Furthermore, it can be reproduced by T3-treatment of organ cultures of tadpole intestine in vitro10, 12, 13, indicating organ-autonomous formation of adult stem/progenitor cells in response to T3.

Molecular and genetic studies have shown that T3 receptor (TR) is both necessary and sufficient to mediate the controlling effects of T3 on metamorphosis in Xenopus laevis14–19. TRs are transcription factors that form heterodimers with 9-cis retinoic acid receptors (RXRs) and these dimers bind to T3 response element (TRE) in/around the promoters of target genes20–23. In the absence of T3, TR/RXR functions as a repressor, while in the presence of T3, TR/RXR functions as an activator. TRs recruit different cofactor complexes to TREs to affect transcription21, 24–31. During Xenopus laevis development, TR first recruits corepressor complexes to target genes during premetamorphosis when T3 is absent and this recruitment is important to keep the T3-inducible genes repressed and to regulate metamorphic timing19, 32–34. When T3 is present, corepressor complexes are released and coactivator complexes are recruited by TR to activate target genes and metamorphosis35–39. Furthermore, the coactivator complexes containing SRC3/p300/PRMT1 (protein arginine methyltransferase 1) are not only necessary for metamorphosis but their levels seem to control the rate of metamorphosis progression35–38. Interestingly, in our studies on PRMT1, we observed that the peak level of PRMT1 expression during intestinal remodeling correlates with rapid proliferation of the adult epithelial stem/progenitor cells but not PRMT1 recruitment by TR to target genes. This raises the possibility that this nuclear hormone receptor coactivator has additional, TR-independent roles in adult stem cell development and/or proliferation. Here we show that differentiated larval epithelial cells with high levels of PRMT1 expression are destined to become adult epithelial stem cells and that PRMT1 is also required for the stem cell development and/or proliferation. We further provide evidence that this stem cell-associated role of PRMT1 is conserved throughout vertebrates.

Materials and Methods

Experimental Animals

Wild type Xenopus laevis and tropicalis were reared in the laboratory or obtained from NASCO. Transgenic animals of Xenopus laevis with the FLAG-tagged wild type PRMT1 under the control of a heat shock inducible promoter were generated as described previously35. Heat shock treatment was done as described35. Mice strain C57BL/6 were obtained from Harlan Laboratories (USA) and reared in the laboratory. All stages of intestines of zebrafish (AB* line) were kindly gifted by the Hickstein Lab (NIH). Animal studies were done as approved by NICHD Animal Use and Care Committee.

In situ hybridization

A partial cDNA encoding Xenopus laevis PRMT1 was obtained by PCR with T7TS-myc PRMT135 as a template and the primers 5’-CTGCAACATGGAGAACTTTG-3’ (forward) and 5’-ACAGTGTTAAGCATTGATTC-3’ (reverse). A partial cDNA encoding mouse PRMT1 was obtained by reverse transcription (RT)-PCR with RNA extracted from mouse ilium at postnatal week 12 (P12 weeks) with the primers 5’- CTGCATCATGGAGGTTTC-3’ (forward) and 5’-ACGGTGTTGAGCATGGACTC-3’ (reverse). A partial cDNA encoding zebrafish PRMT1 was obtained by RT-PCR with RNA extracted from zebrafish at 3–4 days post fertilization (dpf) with the primers 5’- AGAGAGCTCAGCGAAACCTG-3’ (forward) and 5’-TCAGGAAAAATCAGGCCATC-3’ (reverse). The PCR products were cloned into pCRII-TOPO vector (Invitrogen) and verified by sequencing. To synthesize the antisense RNA probe, theses plasmids were linearized with BamHI and transcribed with T7 RNA polymerase (Roche Applied Science).

For in situ hybridization of intestinal sections, Xenopus samples were fixed with MEMFA (100 mM MOPS (pH 7.4) 2 mM EGTA, 1mM MgSO4, 10% formaldehyde) at room temperature while mouse and zebrafish samples were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS at 4 °C overnight. In situ hybridization was performed as previously40.

Immunohistochemistory

For immunohistochemistry, tissues were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS at 4 °C for 2 hours. Samples were then immersed in 30% sucrose in PBS at 4 °C and embedded in OCT compound. Tissue sections were prepared at 8 µm. Immunohistochemistory was performed as described41.

For immunohistochemistry with anti-FLAG antibody, sections were autoclaved in 0.01 M citric acid (pH 6.0) for 15 minutes after washing with PBS containing 0.1% Tween-20 (PBT). After cooling down to room temperature, the sections were washed for 5 min in PBT for 6 times. Sections were then incubated with primary antibody diluted with the blocking buffer (PBT, 0.1% Triton X-100, 1% heat-inactivated goat serum and 1% heat-inactivated donkey serum). The primary antibodies used included anti-FLAG M2 (Sigma) at 1:300 dilution and rabbit anti-phosphor-histone H3 (phosphorylated histone H3) (Upstate) at 1:1000 dilution. As secondary antibodies, anti-mouse Alexa 594 and anti-rabbit Alexa 594 antibodies were used at 1:500 dilution in the blocking buffer. Some sections were counterstained with DAPI (SIGMA) as indicated.

Histology

For histology, tissue sections were stained with methyl green-pyronine Y (Muto, Tokyo, Japan) for 5 min as described42.

Morpholino Injection

The anti-PRMT1 (5’-GTCGCTTCGGCCATCCTTGTGTCAG-3’) (against the Xenopus laevis PRMT1 gene initially reported)35, anti-PRMT1b (5’-TTCGCCTCAGCCATCTTTCGGTCAG-3’) (against the second Xenopus laevis PRMT1 gene, referred here as PRMT1b, as Xenopus laevis is a pseudo-tetraploid organism with many genes duplicated)43, 5-mis-anti-PRMT1 (5’- GTCcCTTCcGCCATCgTTcTGTgAG) and 5-mis-anti-PRMT1b (TTCgCCTCAgCCATCTTTCggTCAg) Vivo-morpholino oligos were obtained form Gene Tools LLC. Equal amount of anti-PRMT1 and anti-PRMT1b morpholino was mixed and used for blocking translation of PRMT1 genes. The 5-mis-anti-PRMT1 and 5-mis-anti-PRMT1b were mixed and used as the control morpholino oligos.

The stock solution for each of the two Vivo-morpholino oligo (0.5 mM, Gene tools) was mixed together and 3–4.5 µl (approximately 4 mg/ml)/day were intraperitoneally injected into stage 54 tadpoles at room temperature. This injection was repeated for 4 consecutive days. Intestines were dissected from some tadpoles with/without morpholino injections for western blot analysis of protein expression. The remaining tadpoles were treated with 5 nM T3 at 18 °C for 4 days after morpholino injections and the intestine was then isolated for histological and immunohistochemical analyses of the proliferation of epithelial progenitor/stem cells.

Results

High levels of PRMT1 expression marks the larval epithelial cells destined to become adult stem/progenitor cells and correlates with adult epithelial cell proliferation

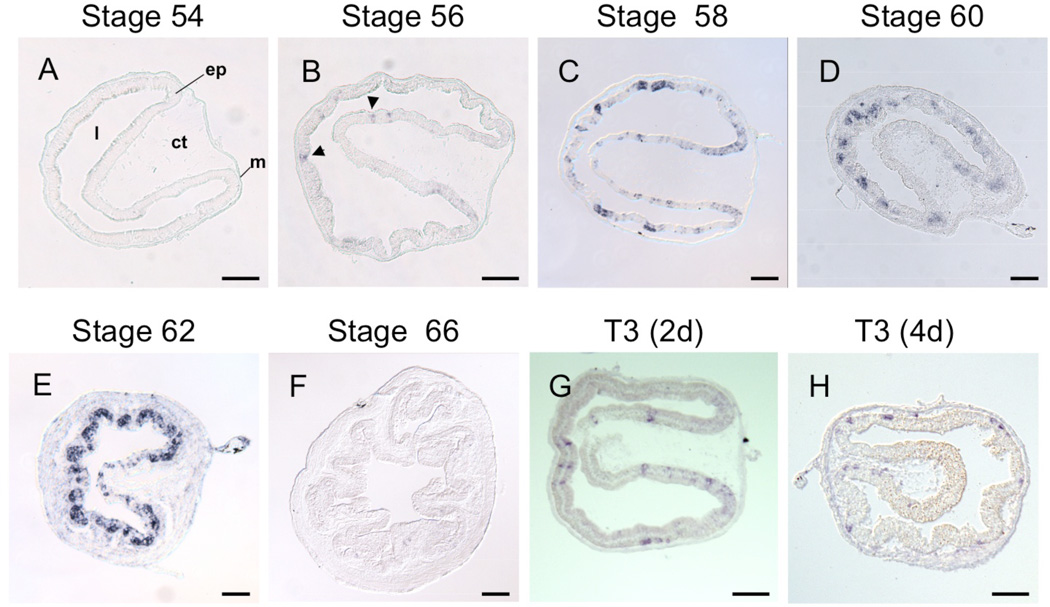

PRMT1 expression can be detected by RT-PCR and western blot throughout intestinal metamorphosis but much higher levels of its mRNA and protein are present at stage 62 when the larval epithelium is essentially replaced by proliferating adult epithelial cells35. To determine the spatiotemporal expression profile of PRMT1 during intestinal metamorphosis, we carried out in situ hybridization on intestinal cross-sections of tadpoles from premetamorphic stage 54 to the end of metamorphosis at stage 66 as well as premetamorphic tadpoles treated with T3 for 2 or 4 days (Fig. 1). Little or no PRMT1 expression was detected by in situ hybridization at premetamorphic stage 54 or the end of metamorphosis. At stage 56 (Fig. 1B), the onset of metamorphosis when T3 becomes detectable in the tadpole plasma, a few cells in the larval epithelium started to show detectable PRMT1 expression. As metamorphosis proceeded, the expression levels in the cells and the number of positive cells increased (Fig. 1C, D) and by stage 62, the climax of metamorphosis when most of the epithelium is occupied by the proliferating adult epithelial cells, high levels of PRMT1 were present in all the proliferating cells while the remaining, dying larval epithelial cells had little or no detectable PRMT1 mRNA (Fig. 1E and data not shown). In addition, after 2–4 days of T3 treatment of premetamorphic tadpoles at stage 54, PRMT1 became detectable in some of the epithelial cells (Fig. 1G and H), similar to that observed at stages 56–58. Thus, PRMT1 expression correlates with adult epithelial cell proliferation during stages 60–62.

Figure 1. PRMT1 is expressed in the adult epithelial progenitors during Xenopus intestinal development.

(A–G) Expression pattern of PRMT1 was analyzed by in situ hybridization in the intestine of tadpoles at stages 54 (A) (premetamorphosis), 56 (B) (premetamorphosis), 58 (C) (metamorphosis), 60 (D) (metamorphosis), 62 (E) (metamorphosis), and 66 (end of metamorphosis) (F), or of stage 54 tadpoles treated with 5 n M T3 for 2 (G) and 4 days (H). Note that strong expression of PRMT1 was found sporadically in the inner epithelial layer at stages 58–62 and after T3 treatment. A few weak signals in the epithelial layer were also present in at stage 56 (arrowheads).

(I–W) Spatiotemporal comparison of PRMT1 expression (J, M, P, S and V) with methyl green-pyronine Y staining (I, L, O, R and U), which preferentially stains the RNA and nuclear DNA, and IFABP expression (K, N, Q, T and W), which labels differentiated absorptive epithelial cells, in the intestine of tadpoles at stages 56 (I–K), 58 (L–N), 60 (O–Q), or of tadpoles at stage 54 treated with T3 for 2 (R–T) and 4 days (U–W). Serial sections were used for in situ hybridization for PRMT1 and IFABP or methyl green-pyronine Y staining. Note that cells weakly positive for PRMT1 expression could be detected as early as by stage 56 or after 2 day T3 treatment of stage 54 tadpoles when the larval epithelium was uniformly positive for IFABP expression. Subsequently, PRMT1 positive cells had no IFABP expression. The methyl green-pyronine Y staining was uniform at stages 56–58 or after 2 days of T3 treatment. However, at stage 60 or after 4 days of T3 treatment, it was strong only in the proliferating adult epithelial cells in the epithelium but weak in the apoptotic larval epithelial cells42. Arrowheads indicate PRMT1 positive region. ep, epithelium. ct, connective tissue. m, muscle. l, lumen. Bar in (A–H) and (I–W), 100 and 50 µm, respectively.

The proliferating adult intestinal epithelial cells can be first identified as multi-cell islets or cell nests around stage 605, 9. The PRMT1 expression pattern suggests that the cells expressing high levels of PRMT1 prior to stage 60 are adult epithelial stem cells or their precursors. To investigate this possibility, serial sections of the intestine at different stages were analyzed by in situ hybridization for the expression of PRMT1 and IFABP (intestinal fatty acid binding protein), whose expression associates with epithelial cell differentiation13, and by staining with methyl green pyronine Y. It has been well established that methyl green pyronine Y co-stains the adult epithelial islets with the stem cell marker Musashi-1 at climax of metamorphosis, thus allowing easy identification of adult progenitor cells13, 44. As shown in Fig. I–K, at the onset of metamorphosis (stage of 56), the larval epithelium was stained uniformly with methyl green pyronine Y and expressed IFABP in all cells. Interestingly, a few cells (Fig. 1J, arrowheads) had detectable levels of PRMT1 mRNA and these cells are differentiated epithelial cells due to the presence of IFABP expression (Fig. 1K, arrowheads). As metamorphosis proceeded to stage 58, there were more cells with detectable expression of PRMT1 (Fig. 1M). These cells were stained with methyl green pyronine Y similarly as the neighboring cells without PRMT1 expression (Fig. 1L). Other the other hand, the PRMT1 positive cells seemed to have lost or reduced IFABP expression (Fig. 1N, arrowheads). By the climax of metamorphosis (stage 60), the proliferating, adult epithelial cells could be easily identified as clusters of multiple cells islets (Fig. 1O, arrowheads) and the IFABP expression was no longer detectable in the epithelial layer (Fig. 1Q). All these islets were positive for PRMT1 expression (Fig. 1P). Similarly, during T3-induced metamorphosis, PRMT1 expression became detectable in a few cells after 2 days of T3 treatment of premetamorphic tadpoles and these PRMT1 positive cells retained IFABP expression and were stained with methyl green pyronine Y similarly as the neighboring cells without PRMT1 expression (Fig. 1R–T). After 4 days of T3 treatment, adult epithelial islets could be identified by their stronger staining with methyl green pyronine Y (Fig. 1U) and all expressed PRMT1 (Fig. 1V) and IFABP expression was down-regulated (Fig. 1W), mimicking that at stage 60 during natural metamorphosis. These results suggested that some of the differentiated larval epithelial cells began to express higher levels of PRMT1 when T3 becomes available during early metamorphosis. These cells subsequently dedifferentiate, losing their IFABP expression, and become the precursor of the adult epithelial stem/progenitor cells.

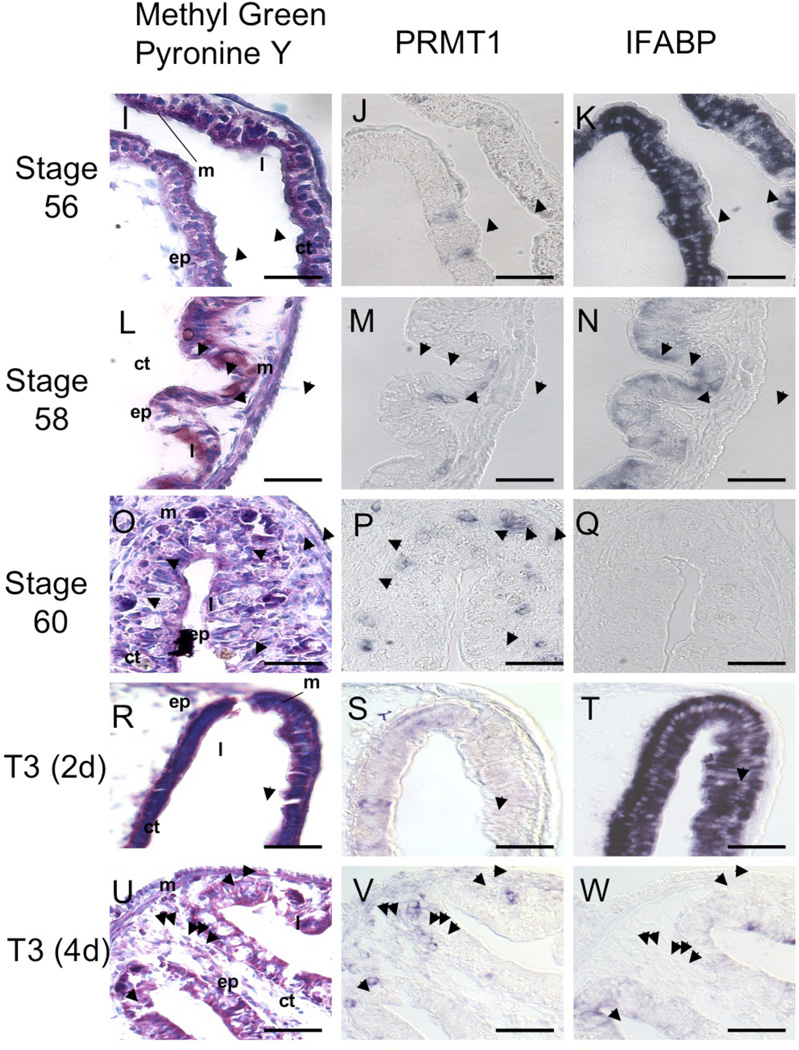

Transgenic overexpression of PRMT1 promotes the formation of adult epithelial stem cells

To investigate whether PRMT1 plays a role in the development and/or proliferation of adult intestinal stem cells, we made use of the animals with a transgenic, FLAG-tagged wild type PRMT1 under the control of heat shock-inducible promoter (Fig. 2). We mated a transgenic male frog with a wild type female and allowed the resulting transgenic (which had green eyes under UV due to the GFP transgene also present in the transgenic construct under the control of a lens-specific promoter) and sibling wild type animals to develop to stage 58, right before detectable larval epithelial cell death and adult epithelial islet formation. The animals were then treated with daily heat shocks for 6 days while they underwent natural metamorphosis, reaching around stage 60 by the end of the treatment. The intestine was isolated from the wild type and transgenic animals. Immunohistochemical analysis of the intestinal cross-sections with an anti-FLAG antibody showed that the transgenic FLAG-tagged PRMT1 was expressed throughout the transgenic intestine, most strongly in the epithelium (Fig. 2C), but not in the wild type intestine (Fig. 2B). More importantly, staining the intestine sections with methyl green pyronine Y showed that many islets of adult proliferating cells were easily detectable in the transgenic but not wild type intestine (Fig. 2D, E). Quantitative analysis showed an increase of over 2 fold in the proliferating epithelial cells in the transgenic intestine compared to the control. This increase was independently confirmed with immunohistochemical staining with an antibody against phosphorylated histone H3, which is present in the mitotic cells (Compared Fig. 2H to G). These results suggest that high levels of PRMT1 promotes the formation of the adult epithelial stem cells and/or enhance their proliferation.

Figure 2. PRMT1 overexpression induces adult cells development.

(A) Schematic representation of the double promoter construct used for generation of transgenic animals. Xenopus heat shock protein 70 promoter (Xhsp70) drives FLAG-tagged PRMT1 (F-PRMT1) expression. Lens-specific γ-crystallin promoter drives GFP expression in the animal eyes for identification of transgenic animals65, which have green eyes under UV light.

(B and C) Immunohistochemistry with an anti-FLAG antibody showing the expression of transgenic F-PRMT1 in the transgenic (Tg) (C) but not wild type (Wt) (B) tadpoles after heat shock treatment. Wt (B) and Tg animals (C) at stage 58 were subjected to heat shock treatment for 6 days. Sections of the intestine were prepared and analyzed immunohistochemically with an anti-FLAG antibody.

(D and E) Intestinal sections as in B and C were stained with methyl green-pyronine Y to detect the islets of proliferating adult cells (arrows) in intestines of Wt (D) and Tg (E) animals. Note that the proliferating islets were stained stronger than the surrounding cells as reported42.

(F) Quantification of the number of proliferating adult cells per section in the Wt and Tg intestines. 3 animals for each sample and 3 sections per animal were counted, yielding Wt=39.44±9.86, Tg=83.56±4.87 cells/section. * indicates p values < 0.05 when Tg animals was compared to Wt ones.

(G and H) Analysis of the phosphorylated histone H3 also demonstrates the increased proliferating cells in the transgenic animals. The intestinal sections in Wt (G) and Tg (H) animals as above were analyzed by immunohistochemistry with an antibody against –phosphorylated histone H3, which is specific for proliferating cells. White arrows show cells positive for phosphorylated histone H3 in the epithelium. ep, epithelium. ct, connective tissue. m, muscle. l, lumen. Bars, 50 µm.

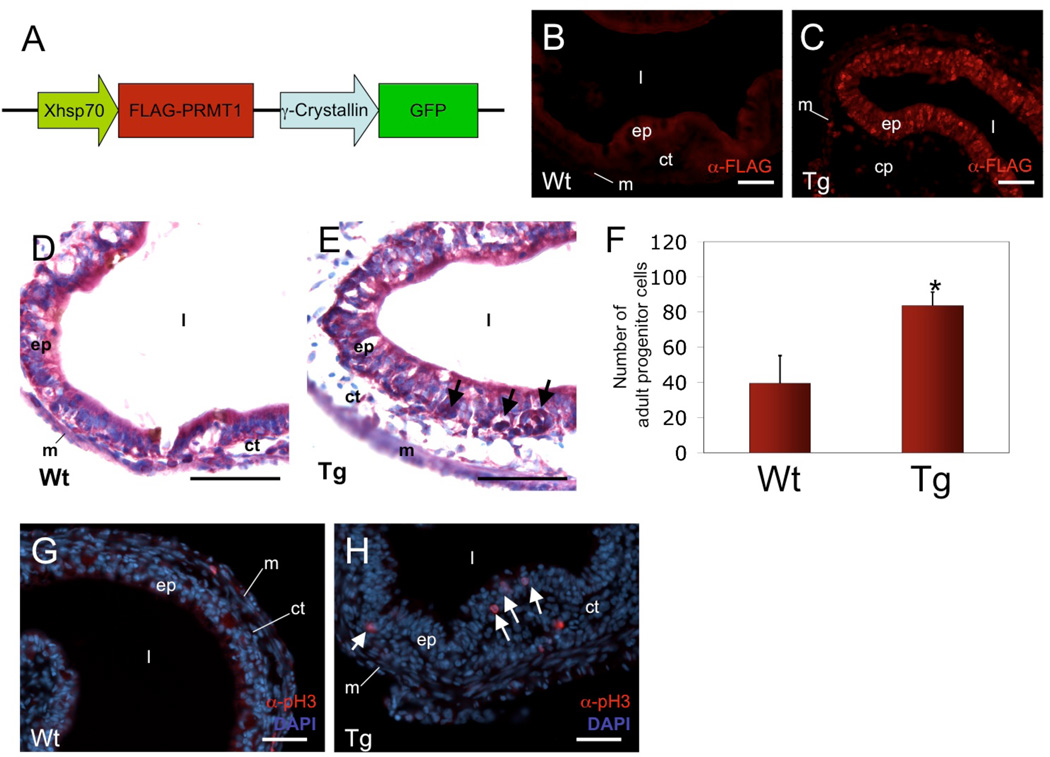

Knocking down the expression of endogenous PRMT1 inhibits the formation of adult epithelial stem cells

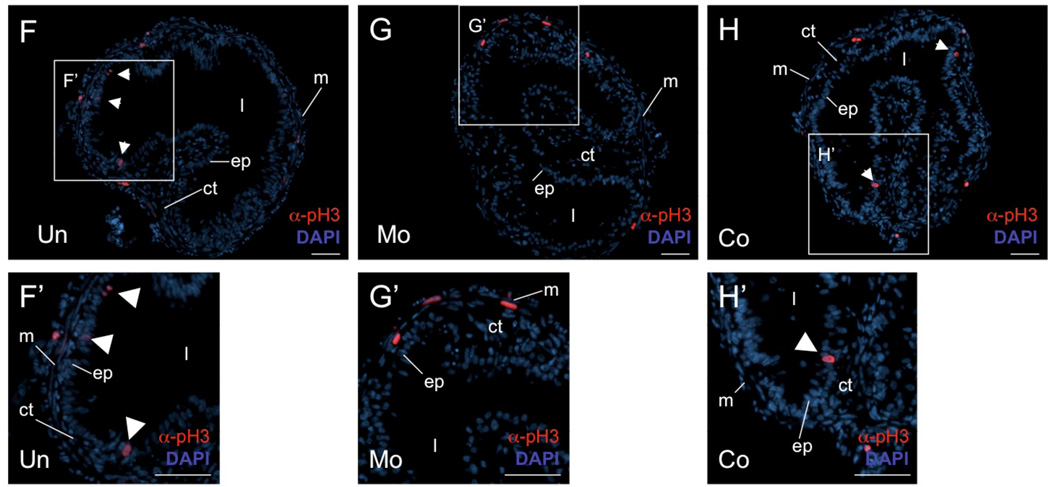

To investigate function of endogenous PRMT1 in the development and/or proliferation of adult intestinal stem cells, we chose to knock down the expression of endogenous PRMT1 by using antisense morpholino oligonucleotides. To facilitate the uptake of the oligonucleotides, we used vivo-morpholino oligonucleotides45. As there are two PRMT1 genes due to the duplication in the Xenopus laevis genome, we mixed two vivo-morpholino oligonucleotides, one against the translation start site of each of the two genes. These vivo-morpholino oligonucleotides or control vivo-morpholino oligonucleotides (containing 5 base mismatches against the genes) were intraperitoneally injected into stage 54 tadpoles at room temperature for 4 consecutive days. The animals were then treated with 5 nM T3 (about the peak plasma concentration at the climax of natural metamorphosis) for 4 additional days. As shown in Fig. 3A, the expression of PRMT1 protein in the intestine was knocked down in animals injected with the specific vivo-morpholino oligonucleotides but not with the control vivo-morpholino oligonucleotides. The specificity of the vivo-morpholino oligonucleotides was demonstrated by the lack of any effect on histone H4 (Fig. 3A). When the intestinal cross-sections were stained with methyl green pyronine Y, it was found that PRMT1 knocking down led to a reduced number of adult epithelial islets (compare Fig. 3C to B or D) and the number of adult proliferating progenitor cells (Fig. 3E). Similarly, immunohistochemical staining with the antibody against the phosphorylated histone H3 showed reduced mitotic cells in the epithelial layer of the intestine of animals injected with the specific vivo-morpholino oligonucleotides (Fig. 3G, G’) but not with the control vivo-morpholino oligonucleotides (Fig. 3H and H’) compared to the control, uninjected animals (Fig. 3F, F’) (note the some mitotic cells were detected in the connective tissue and muscle layers in all animals). These results indicate that PRMT1 is necessary for the formation and/or proliferation of the adult stem/progenitor cells.

Figure 3. Knocking-down the expression of endogenous PRMT1 results in the reduction in the number of proliferating adult cells in the intestine.

(A) In vivo knock-down of PRMT1 expression. Total protein was isolated from the intestine of stage 53/54 tadpoles with (MO, Co) or without (Un) IP injection of PRMT1 (MO) or control (Co) Vivo-morpholino oligos and subjected to western blot analysis for the endogenous PRMT1 or histone H4 (as a control). Note that PRMT1 expression was lower in the PRMT1 morphants (Mo) than wild type (Un) or control morphants (Co), while histone H4 level was not affected by Vivo-morpholino oligos.

(B–D) Reduced adult epithelial cell islets in PRMT1 morphants. After daily injection with/without morpholinos and treatment with 5nM of T3 for 4 days, tadpoles at stage 53/54 were sacrificed and intestinal phenotype was histologically analyzed after methyl green/pyronine Y staining. Black triangle indicates the islets of proliferating adult progenitor or stem cells, which stain more strongly than the surrounding larval epithelial cells undergoing apoptosis).

(E) Quantitative analysis showing a reduction in proliferating adult cells after PRMT1 morpholino oligo treatment as shown in B–D. For each group, 3 sections for each of the 3 animals were counted. Un=22.23±1.43, Mo=14.67±1.96, Co=23.42±2.05 cells/section were observed. * indicates p values < 0.05 when compared to the Un animals.

(F–H) Analysis of the phosphorylated histone H3 also demonstrates the reduced proliferating cells in PRMT1 morphants. Cell proliferation was analyzed by immunohistochemistry with anti phosphorylated histone H3 antibody (α-pH3) on the intestinal sections of uninjected (Un) (F), PRMT1 (MO) (G) or control (Co) (H) Vivo-morpholino oligo injected animals. Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI. White arrowheads indicate cells positive for phosphorylated histone H3 in the epithelium. (F’–H’) Higher magnification photographs of the inserts in (F–H). Note that in the representative examples showing here, there were 3 proliferating cells detected in epithelium of the uninjected section (F), 2 in the control oligo-injected section (H), and none in the PRMT1 oligo injected section (G). Also, some mitotic cells were detected in the connective tissue and muscle layers in all animals and there were no apparent difference among the different animal groups. ep, epithelium. ct, connective tissue. m, muscle. l, lumen. Bars, 50 µm.

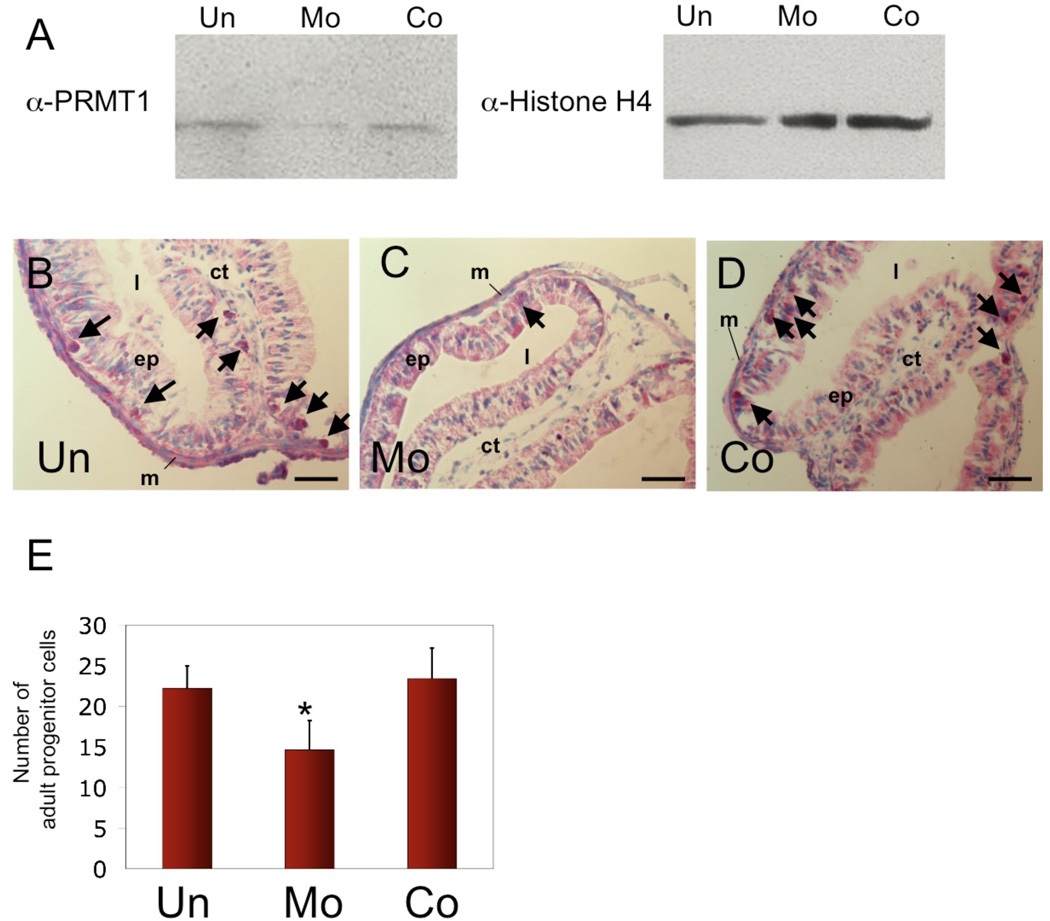

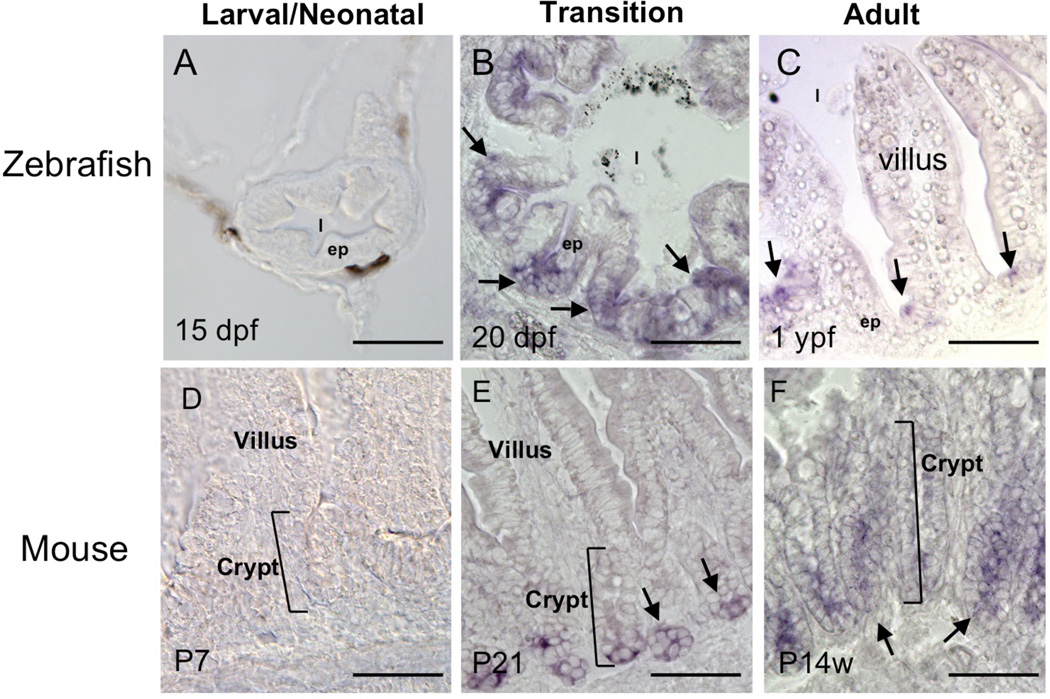

Stem cell-specific expression of PRMT1 is conserved during intestinal development in vertebrates

The intestine is structurally similar in all adult vertebrates, with the proliferating stem cells located in the crypts/troughs of the epithelial folds and differentiated epithelial cells located along the villi or the folds. At the tip of the villus or fold, the differentiated epithelial cells degenerate through apoptosis. The maturation of this adult structure occurs at different stage of development in different animals but interestingly all occurring around the time when plasma T3 levels are high, just like during amphibian metamorphosis. To investigate whether the function of PRMT1 in the intestine is conserved during development, we analyzed the expression of endogenous PRMT1 by in situ hybridization in mouse and zebrafish. We chose animals at three different stages: when plasma T3 levels were low and the intestine was the larval/neonatal form (15 dpf (days post fertilization) for zebrafish and P7 (7 days after birth for mouse)) (Fig. 4A, D), when T3 levels were high (20 dpf for zebrafish and P21 for mouse) (Fig. 4B, E), and when the animals were adult and T3 reached the adult levels (1 ypf (1 year post fertilization) for zebrafish or P14w (14 weeks after birth) for mouse) (Fig. 4C, F)46, 47. Just like in Xenopus laevis, there was little PRMT1 expression in the larval/neonatal zebrafish or mouse (Fig. 4A, D). As the intestine underwent the transition into the adult form during the transition period when T3 levels were high, high levels of PRMT1 mRNA was found to be expressed only in the bottom of the developing epithelial fold in zebrafish (Fig. 4B) or the crypt of the mouse intestine (Fig. 4E). In adult animals, the PRMT1 expression was high in the mouse crypts and the bottom of the zebrafish intestinal epithelial folds, where the stem cells were located. Thus, stem/progenitor cell-specific expression of PRMT1 is conserved spatiotemporally during vertebrate intestinal development.

Figure 4. Conserved spatiotemporal expression patters of PRMT1 in the postembryonic intestines of fish and mouse.

PRMT1 expression was analyzed by in situ hybridization in the intestines of zebrafish at 15 days post fertilization (dpf) (A), 20 dpf (B) and 1 year post fertilization (ypf) (C) and mouse at postnatal day 7 (P7), P21, and postnatal week 14 (P14w). Arrows indicate PRMT1 positive cells in the intestinal epithelium. Note that high levels of PRMT1 expression is detected only in the proliferating/stem cells located in the crypts in both species, just like in Xenopus laevis. In addition, the transition period in both species is characterized by high levels of T3 in the serum, resembling metamorphosis in amphibians. ep, epithelium. l, lumen. Bars, 50 µm.

Discussion

Adult organ-specific stem cells hold the great promise for organ repair and replacement therapies. Many tissues/organs, such as the intestine and skin, in adult vertebrates undergo regular self-renewal. This occurs through the proliferation of adult organ-specific stem cells followed by subsequent cell differentiation to replace the degenerating preexisting cells, often due to apoptosis or programmed cell death. In addition, adult organ-specific stem cells are also essential for tissue repair and regeneration. Such organ-specific stem cells are often derived during embryogenesis from one of the 3 germ layers, ectoderm, endoderm, and the in-between mesoderm. However, how they are generated and subsequently regulated in the adult are poorly understood. Deciphering the underlying mechanism is critical for generating and maintaining organ-specific stem cells that are essential for organ repair and replacement therapies.

Recent progresses on induced pluripotent stem cells have highlighted the importance of transcription factors in determining stem cell identity48, 49. Here, only four transcription factors: oct4, sox2, klf4, and myc, when overexpressed, were sufficient to reprogram fibroblasts into cells resembling embryonic stem cells49. Similarly, differentiated acinal cells in the pancreas can be converted into beta cells when just 3 genes (Ngn3, Pdx1, Mafa) were overexpressed in adult mouse pancreas50, 51. These studies indicate that altering the activities of transcriptional factors can change the fate of differentiated cells. It is generally believed that transcription factors regulate target gene expression by recruiting cofactors to the target promoters. To date, the role of transcription cofactors in stem cells remains essentially unexplored.

Here, we have provided strong evidence that one cofactor, PRMT1, a known coactivator for TR and other nuclear hormone receptors52, 53, is an important and evolutionarily conserved player in the development of adult intestinal stem cells during vertebrate development. High levels of PRMT1 expression mark the larval epithelial cells destined to become adult epithelial stem/progenitor cells during frog metamorphosis and more importantly PRMT1 is required for the development and/or proliferation of these stem cells.

Amphibian metamorphosis has long been used as a model to study vertebrate postembryonic development due to its regulation by T37, 8. The effects of T3 are mediated by TRs18. Several transcription coactivators, including PRMT1, have been shown to be expressed and recruited by liganded TR to target genes during frog metamorphosis19, 35–39, 54, 55. Interestingly, PRMT1 expression is upregulated during intestinal metamorphosis and its recruitment by liganded TR is only transient35. There is little recruitment of PRMT1 to the T3 target genes by TR at the peak of its expression at stage 62 when plasma T3 level is maximal and the larval epithelium is essentially replaced by proliferating adult epithelial cells, suggesting a TR-independent role of PRMT1 in the proliferating adult epithelial cells.

The proliferating adult intestinal epithelial cells were first identified as multi-cell islets or cell nests around stage 605, 9, 56, 57. The origin of the adult stem/progenitor cells has been a long-standing and interesting question. Several possibilities exist, including the existence of reserved stem cells, dedifferentiation of larval epithelial cells, and stem cells migrated from other tissues. Extensive earlier histological and cytological analyses had failed to identify any reserved adult stem/progenitor cells in the premetamorphic tadpole intestine5, 9, 56, 57. A number of studies suggest that these cells are derived from the epithelium, likely from dedifferentiation of larval epithelial cells5, 9–11, 56–58. Our analyses of the expression of PRMT1 and the differentiated marker gene IFABP revealed for the first time that at the early stage of metamorphosis, some of the larval epithelial cells begin to up-regulate the expression of PRMT1. These cells subsequently lose their IFABP gene expression as they dedifferentiate. They eventually form the adult epithelial stem/progenitor cells by the climax of metamorphosis. Thus, high levels of PRMT1 expression is the earliest known molecular marker for epithelial cells destined to differentiate into the adult stem cells. It would be interesting in the future to investigate how PRMT1 gene is upregulated during early metamorphosis to gain insight on how some epithelial cells are induced to become adult epithelial stem cells.

In addition to serving as an early marker, our functional studies showed that PRMT1 expression is required for either the formation of the stem cells and/or their proliferation. Transgenic overexpression leads to more proliferating adult epithelial cells while knocking down the endogenous PRMT1 expression reduces it. How PMRT1 functions during adult epithelial stem cell development and/or proliferation remains unknown. It is unlikely to function through TR. At stage 62, the larval epithelium is essentially replaced by the proliferating adult epithelial cells and PRMT1 reaches highest expression but little PRMT1 recruitment is recruited to the target genes by liganded TR35. Thus, PRMT1 likely functions through other transcription factors during adult epithelial cell proliferation. On the other hand, when PRMT1 is first activated during early metamorphosis in the differentiated epithelial cells destined to become the stem cells, it presumably functions as a coactivator of TR to regulate target genes in these cells to facilitate their dedifferentiation to become stem cells since T3 is required for adult epithelial development and PRMT1 is recruited to the TR target genes during this period9, 59.

A role of PRMT1 in cell proliferation has been implicated by studies in mammalian cells as well. PRMT1 is recruited to cyclin E1 promoter in G1/S phase60 and it is involved in oncogenesis61. PRMT1 is required for early postimplantation mouse development although PRMT1 knockout cells are viable62, 63. Interestingly, loss of PRMT1 in mouse embryonic fibroblasts leads to cell growth arrest due to spontaneous DNA damage, cell cycle progression delay, and checkpoint defects, etc.62. In addition, PRMT1 is highly expressed in colon cancer64, supporting a role in cell proliferation.

While frogs are unique in the extent of the transformations that take place during metamorphosis, T3 is critical for postembryonic development in different vertebrates1, 7, 8, 46. Furthermore, many similarities/conservations exist among different vertebrate species during the postembryonic developmental period1, 8. In both mammals and frogs, the intestine changes from a larval/embryonic form to a more complex adult form during this T3-dependent period. Our analyses here demonstrate that PRMT1 expression is also upregulated in the stem cells of the intestinal epithelium in both zebrafish and mouse as the intestine is transformed to establish the self-renewing system in adult animals. In both mouse and zebrafish, the upregulation of PRMT1 expression coincides with the establishment of the villus-crypt axis (epithelial fold), just like in Xenopus laevis, suggesting that here PRMT1 is also important for the development of the adult epithelial stem cells and the formation of the crypts in order to establish the self-renewing system in the adult intestine. Thus, PRMT1 has an evolutionarily conserved role in the development and/or maintenance of the adult intestinal epithelial stem cells. It will be necessary in the near future to functionally demonstrate this conserved role of PRMT1 in zebrafish and mouse and to determine how PRMT1 exerts this effect by identifying its target genes and interacting transcription factors/partners in this process.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Mizuki Azuma (NIH) and Dennis Hickstein (NIH) for the gift of zebrafish intestines. We also thank Drs. Makoto Suzuki (National Institute of Basic Biology, Japan), Takashi Hasebe (Nippon Medical School, Japan), Atsuko Ishizuya-Oka (Nippon Medical School, Japan) for providing us technical information and advice, and Dr. Rachel Heimeier (NIH) for helping mouse preparation.

References

- 1.Tata JR. Gene expression during metamorphosis: an ideal model for post-embryonic development. Bioessays. 1993;15(4):239–248. doi: 10.1002/bies.950150404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.MacDonald WC, Trier JS, Everett NB. Cell proliferation and migration in the stomach, duodenum, and rectum of man: Radioautographic studies. Gastroenterology. 1964;46:405–417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Toner PG, Carr KE, Wyburn GM. The Digestive System: An Ultrastructural Atlas and Review. London: Butterworth; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 4.van der Flier LG, Clevers H. Stem Cells, Self-Renewal, and Differentiation in the Intestinal Epithelium. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2009;71:241–260. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.010908.163145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McAvoy JW, Dixon KE. Cell proliferation and renewal in the small intestinal epithelium of metamorphosing and adult Xenopus laevis. J. Exp. Zool. 1977;202:129–138. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sancho E, Eduard Batlle E, Clevers H. Signaling pathways in intestinal development and cancer. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev.Biol. 2004;20:695–723. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.010403.092805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gilbert LI, Tata JR, Atkinson BG. Metamorphosis: Post-embryonic reprogramming of gene expression in amphibian and insect cells. New York: Academic Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shi Y-B. Amphibian Metamorphosis: From morphology to molecular biology. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shi Y-B, Ishizuya-Oka A. Biphasic intestinal development in amphibians: Embryogensis and remodeling during metamorphosis. Current Topics in Develop. Biol. 1996;32:205–235. doi: 10.1016/s0070-2153(08)60429-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ishizuya-Oka A, Hasebe T, Buchholz DR, Kajita M, Fu L, Shi YB. Origin of the adult intestinal stem cells induced by thyroid hormone in Xenopus laevis. Faseb J. 2009 Mar 19;23:2568–2575. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-128124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schreiber AM, Cai L, Brown DD. Remodeling of the intestine during metamorphosis of Xenopus laevis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005 Mar 8;102(10):3720–3725. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409868102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ishizuya-Oka A, Shimozawa A. Induction of metamorphosis by thyroid hormone in anuran small intestine cultured organotypically in vitro. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol. 1991;27A(11):853–857. doi: 10.1007/BF02630987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ishizuya-Oka A, Ueda S, Damjanovski S, Li Q, Liang VC, Shi Y-B. Anteroposterior gradient of epithelial transformation during amphibian intestinal remodeling: immunohistochemical detection of intestinal fatty acid-binding protein. Dev Biol. 1997;192(1):149–161. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schreiber AM, Das B, Huang H, Marsh-Armstrong N, Brown DD. Diverse developmental programs of Xenopus laevis metamorphosis are inhibited by a dominant negative thyroid hormone receptor. PNAS. 2001;98:10739–10744. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191361698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown DD, Cai L. Amphibian metamorphosis. Dev Biol. 2007 Jun 1;306(1):20–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buchholz DR, Hsia VS-C, Fu L, Shi Y-B. A dominant negative thyroid hormone receptor blocks amphibian metamorphosis by retaining corepressors at target genes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003;23:6750–6758. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.19.6750-6758.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buchholz DR, Tomita A, Fu L, Paul BD, Shi Y-B. Transgenic analysis reveals that thyroid hormone receptor is sufficient to mediate the thyroid hormone signal in frog metamorphosis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;24:9026–9037. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.20.9026-9037.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buchholz DR, Paul BD, Fu L, Shi YB. Molecular and developmental analyses of thyroid hormone receptor function in Xenopus laevis, the African clawed frog. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2006 Jan 1;145(1):1–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shi Y-B. Dual functions of thyroid hormone receptors in vertebrate development: the roles of histone-modifying cofactor complexes. Thyroid. 2009;19:987–999. doi: 10.1089/thy.2009.0041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lazar MA. Thyroid hormone receptors: multiple forms, multiple possibilities. Endocr Rev. 1993;14(2):184–193. doi: 10.1210/edrv-14-2-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yen PM. Physiological and molecular basis of thyroid hormone action. Physiol Rev. 2001;81(3):1097–1142. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.3.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mangelsdorf DJ, Thummel C, Beato M, et al. The nuclear receptor superfamily: the second decade. Cell. 1995;83(6):835–839. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90199-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsai MJ, O'Malley BW. Molecular mechanisms of action of steroid/thyroid receptor superfamily members. Ann Rev Biochem. 1994;63:451–486. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.63.070194.002315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ito M, Roeder RG. The TRAP/SMCC/Mediator complex and thyroid hormone receptor function. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2001;12(3):127–134. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(00)00355-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rachez C, Freedman LP. Mechanisms of gene regulation by vitamin D(3) receptor: a network of coactivator interactions. Gene. 2000;246(1–2):9–21. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00052-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang J, Lazar MA. The mechanism of action of thyroid hormones. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2000;62:439–466. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.62.1.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burke LJ, Baniahmad A. Co-repressors 2000. FASEB J. 2000;14(13):1876–1888. doi: 10.1096/fj.99-0943rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jepsen K, Rosenfeld MG. Biological roles and mechanistic actions of co-repressor complexes. J Cell Sci. 2002 Feb 15;115(Pt 4):689–698. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.4.689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jones PL, Shi Y-B. N-CoR-HDAC corepressor complexes: Roles in transcriptional regulation by nuclear hormone receptors. In: Workman JL, editor. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology: Protein Complexes that Modify Chromatin. Vol 274. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 2003. pp. 237–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rachez C, Freedman LP. Mediator complexes and transcription. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2001 Jun;13(3):274–280. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00209-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hu X, Lazar MA. Transcriptional Repression by Nuclear Hormone Receptors. TEM. 2000;11(1):6–10. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(99)00215-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tomita A, Buchholz DR, Shi Y-B. Recruitment of N-CoR/SMRT-TBLR1 corepressor complex by unliganded thyroid hormone receptor for gene repression during frog development. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;24:3337–3346. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.8.3337-3346.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sachs LM, Jones PL, Havis E, Rouse N, Demeneix BA, Shi Y-B. N-CoR recruitment by unliganded thyroid hormone receptor in gene repression during Xenopus laevis development. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22:8527–8538. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.24.8527-8538.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sato Y, Buchholz DR, Paul BD, Shi Y-B. A role of unliganded thyroid hormone receptor in postembryonic development in Xenopus laevis. Mechanisms of Development. 2007;124:476–488. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matsuda H, Paul BD, Choi CY, Hasebe T, Shi Y-B. Novel functions of protein arginine methyltransferase 1 in thyroid hormone receptor-mediated transcription and in the regulation of metamorphic rate in Xenopus laevis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2009;29:745–757. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00827-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Paul BD, Buchholz DR, Fu L, Shi Y-B. Tissue- and gene-specific recruitment of steroid receptor coactivator-3 by thyroid hormone receptor during development. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:27165–27172. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503999200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paul BD, Fu L, Buchholz DR, Shi Y-B. Coactivator recruitment is essential for liganded thyroid hormone receptor to initiate amphibian metamorphosis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005;25:5712–5724. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.13.5712-5724.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paul BD, Buchholz DR, Fu L, Shi Y-B. SRC-p300 coactivator complex is required for thyroid hormone induced amphibian metamorphosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:7472–7481. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607589200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Havis E, Sachs LM, Demeneix BA. Metamorphic T3-response genes have specific coregulator requirements. EMBO Reports. 2003;4:883–888. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.embor908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Matsuda H, Yokoyama H, Endo T, Tamura K, Ide H. An epidermal signal regulates Lmx-1 expression and dorsal-ventral pattern during Xenopus limb regeneration. Dev Biol. 2001 Jan 15;229(2):351–362. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Suzuki M, Satoh A, Ide H, Tamura K. Transgenic Xenopus with prx1 limb enhancer reveals crucial contribution of MEK/ERK and PI3K/AKT pathways in blastema formation during limb regeneration. Dev Biol. 2007;304:675–686. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ishizuya-Oka A, Ueda S. Apoptosis and cell proliferation in the Xenopus small intestine during metamorphosis. Cell Tissue Res. 1996;286(3):467–476. doi: 10.1007/s004410050716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Batut J, Vandel L, Leclerc C, Daguzan C, Moreau M, Néant I. The Ca2+induced methyltransferase xPRMT1b controls neural fate in amphibian embryo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15128–15133. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502483102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ishizuya-Oka A, Shimizu K, Sakakibara S, Okano H, Ueda S. Thyroid hormone-upregulated expression of Musashi-1 is specific for progenitor cells of the adult epithelium during amphibian gastrointestinal remodeling. J Cell Sci. 2003 Aug 1;116(Pt 15):3157–3164. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li Y-F, Morcos PA. Design and synthesis of dendritic molecular transporter that achieves efficient in vivo delivery of morpholino antisense oligo. Bioconjug Chem. 2008;19:1464–1470. doi: 10.1021/bc8001437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brown DD. The role of thyroid hormone in zebrafish and axoloft development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:13011–13016. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.24.13011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Friedrichsen S, Christ S, Heuer H, et al. Regulation of iodothyronine deiodinases in the Pax8−/− mouse model of congenital hypothyroidism. Endocrinology. 2003;144:777–784. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-220715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pei D. Regulation of pluripotency and reprogramming by transcription factors. J Biol Chem. 2009 Feb 6;284(6):3365–3369. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R800063200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006 Aug 25;126(4):663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhou Q, Brown J, Kanarek A, Rajagopal J, Melton DA. In vivo reprogramming of adult pancreatic exocrine cells to beta-cells. Nature. 2008;455:627–632. doi: 10.1038/nature07314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhou Q, Melton DA. Extreme makeover: converting one cell into another. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:382–388. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen D, Ma H, Hong H, et al. Regulation of transcription by a protein methyltransferase. Science. 1999;284:2174–2177. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5423.2174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee YH, Stallcup MR. Minireview: protein arginine methylation of nonhistone proteins in transcriptional regulation. Mol Endocrinol. 2009 Apr;23(4):425–433. doi: 10.1210/me.2008-0380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Matsuda H, Paul BD, Choi CY, Shi Y-B. Contrasting effects of two alternative splicing forms of coactivator-associated arginine methyltransferase 1 on thyroid hormone receptor-mediated transcription in Xenopus laevis. Mol. Endocrinology. 2007;21(5):1082–1094. doi: 10.1210/me.2006-0448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Paul BD, Shi Y-B. Distinct expression profiles of transcriptional coactivators for thyroid hormone receptors during Xenopus laevis metamorphosis. Cell Research. 2003;13:459–464. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Marshall JA, Dixon KE. Cell proliferation in the intestinal epithelium of Xenopus laevis tadpoles. J. Exp. Zool. 1978;203:31–40. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bonneville MA. Fine structural changes in the intestinal epithelium of the bullfrog during metamorphosis. J. Cell Biol. 1963;18:579–597. doi: 10.1083/jcb.18.3.579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Amano T, Noro N, Kawabata H, Kobayashi Y, Yoshizato K. Metamorphosis-associated and region-specific expression of calbindin gene in the posterior intestinal epithelium of Xenopus laevis larva. Dev Growth Differ. 1998;40:177–188. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-169x.1998.00007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shi Y-B, Ishizuya-Oka A. Thyroid hormone regulation of apoptotic tissue remodeling: Implications from molecular analysis of amphibian metamorphosis. Progress in Nucleic Acid Research and Molecular Biology. 2001;65:53–100. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(00)65002-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Messaoudi SE, Fabbrizio E, Rodriguez C, et al. Coactivator-associated arginine methyltransferase 1 (CARM1) is a positive regulator of the Cyclin E1 gene. PNAS. 2006;103:13351–13356. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605692103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ngai Cheung N, Chong Chan LC, Thompson A, Cleary ML, So CWE. Protein arginine-methyltransferase-dependent oncogenesis. Nature Cell Biology. 2007;9:1208–1215. doi: 10.1038/ncb1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yu Z, Chen T, Hebert J, Li E, Richard S. A mouse PRMT1 null allele defines an essential role for arginine methylation in genome maintenance and cell proliferation. Mol Cell Biol. 2009 Jun;29(11):2982–2996. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00042-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pawlak MR, Scherer CA, Chen J, Roshon MJ, Ruley HE. Arginine N-methyltransferase 1 is required for early postimplantation mouse development, but cells deficient in the enzyme are viable. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000;20:4859–4869. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.13.4859-4869.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Papadokostopoulou A, Mathioudaki K, Scorilas A, et al. Colon cancer and protein arginine methyltransferase 1 gene expression. Anticancer Res. 2009;29:1361–1366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fu L, Buchholz D, Shi YB. Novel double promoter approach for identification of transgenic animals: A tool for in vivo analysis of gene function and development of gene-based therapies. Mol Reprod Dev. 2002 Aug;62(4):470–476. doi: 10.1002/mrd.10137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]