Abstract

Short palate, lung and nasal epithelium clone 1 (SPLUNC1) is enriched in normal airway lining fluid, but is significantly reduced in airway epithelium exposed to a Th2 cytokine milieu. The role of SPLUNC1 in modulating airway allergic inflammation (e.g., eosinophils) remains unknown. We used SPLUNC1 knockout (KO) and littermate wild-type (C57BL/6 background) mice and recombinant SPLUNC1 protein to determine the impact of SPLUNC1 on airway allergic/eosinophilic inflammation, and to investigate the underlying mechanisms. An acute ovalbumin (OVA) sensitization and challenge protocol was used to induce murine airway allergic inflammation (e.g., eosinophils, eotaxin-2, and Th2 cytokines). Our results showed that SPLUNC1 in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of OVA-challenged wild-type mice was significantly reduced (P < 0.05), which was negatively correlated with levels of lung eosinophilic inflammation. Moreover, SPLUNC1 KO mice demonstrated significantly higher numbers of eosinophils in the lung after OVA challenges than did wild-type mice. Alveolar macrophages isolated from OVA-challenged SPLUNC1 KO versus wild-type mice had higher concentrations of baseline eotaxin-2 that was amplified by LPS (a known risk factor for exacerbating asthma). Human recombinant SPLUNC1 protein was applied to alveolar macrophages to study the regulation of eotaxin-2 in the context of Th2 cytokine and LPS stimulation. Recombinant SPLUNC1 protein attenuated LPS-induced eotaxin-2 production in Th2 cytokine–pretreated murine macrophages. These findings demonstrate that SPLUNC1 inhibits airway eosinophilic inflammation in allergic mice, in part by reducing eotaxin-2 production in alveolar macrophages.

Keywords: SPLUNC1, asthma, alveolar macrophage, Th2 cytokines, eotaxin-2

Clinical Relevance

Th2 cytokines significantly reduce short palate, lung and nasal epithelium clone 1 (SPLUNC1) expression in human airway epithelial cells. However, whether reduced SPLUNC1 in turn modulates airway allergic inflammation is unknown. This study demonstrates that allergic inflammation reduces SPLUNC1 in murine lungs. SPLUNC1 deficiency enhances airway eosinophilic inflammation in ovalbumin-challenged mice, in part by increasing eotaxin-2 production in alveolar macrophages. Restoring SPLUNC1 concentrations in allergic airways may reduce asthma severity by reducing eosinophilic inflammation.

Asthma is a complex inflammatory syndrome afflicting millions of people worldwide (1). Persistent airway inflammation and acute exacerbations, the hallmarks of severe asthma, pose significant challenges to healthcare. Although the underlying mechanisms of asthma exacerbations are unclear, eosinophils appear to play a major role at least in a subset of patients (2). Clinical studies demonstrated strong correlations between enhanced endotoxin (LPS) responsiveness and disease severity in asthma (3–5). LPS, a ubiquitous component of dust and air pollution, has been proposed to activate eosinophils in the bronchial tissues of patients with asthma, in some cases provoking inflammatory processes (6). Alveolar macrophages, comprising one of the first lines in lung host defense, play a central role in the maintenance of lung homeostasis, although an excessive immune response from alveolar macrophages can exaggerate airway inflammation (7). Previous studies showed that alveolar macrophages isolated from subjects with asthma are hyperresponsive to LPS, compared with alveolar macrophages from healthy control subjects (8), but the underlying mechanisms remain unclear.

Short palate, lung and nasal epithelium clone 1 (SPLUNC1) is an abundant protein present in the airway lining fluid of healthy humans and mice, and is mainly produced by large airway epithelia and submucosal glands. SPLUNC1 was predicted to exert host defense functions, based on its sequence homology with other known antimicrobial proteins such as bactericidal permeability increasing protein and LPS-binding protein (LBP) (9). We previously demonstrated that the Th2 cytokine IL-13 significantly reduces SPLUNC1 expression and secretion from well-differentiated human primary airway epithelial cells, rendering a host susceptible to bacterial infections (10). Recent studies by our group and others demonstrated that SPLUNC1 is critical for clearing respiratory pathogens such as Mycoplasma pneumoniae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa from murine lungs (10–12). In addition to its antimicrobial function, we have shown that murine recombinant SPLUNC1 protein inhibits the Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) agonist–induced production of IL-8 in human airway epithelial cells (10). These observations led us to hypothesize that SPLUNC1 has the potential to affect airway allergic inflammation. The present study investigated whether SPLUNC1 is important in regulating airway eosinophilic inflammation by using our recently generated SPLUNC1 knockout (KO) murine model and recombinant SPLUNC1 protein.

Materials and Methods

Murine Model of Ovalbumin-Induced Airway Allergic Inflammation

The SPLUNC1 KO mice generated in our laboratory and littermate wild-type mice (C57BL/6 background) were bred under pathogen-free housing conditions (11). All mice (6–8 weeks old) were sensitized by an intraperitoneal injection of 20 μg ovalbumin (OVA; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) emulsified in aluminum hydroxide (Imject Alum; Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) on Day 0 and Day 7, and challenged with aerosolized 1% OVA or saline for 30 minutes each day for 3 consecutive days (on Days 14, 15, and 16). Mice were killed 24 hours after the last challenge (13). Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was performed with 1 ml saline. All of the experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at National Jewish Health.

Macrophage Cell Culture

Murine primary alveolar macrophages (AMs) were obtained by lavaging murine lungs. AMs were isolated by adherence and cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS and penicillin/streptomycin. Because of the limited numbers of murine primary AMs, a murine macrophage cell line Raw 264.7 was similarly cultured to study the mechanisms of eotaxin-2 regulation in the presence or absence of Th2 cytokines and LPS. In some experiments, cells were pretreated for 1 hour with human recombinant SPLUNC1 protein before LPS stimulation. At the indicated time points, cell samples were collected for protein and mRNA determination.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR

An equal amount of RNA (1 μg) was used to prepare cDNA. Murine SPLUNC1, MUC5AC, and eotaxin-2 (CCL24) mRNA concentrations were determined by quantitative real-time PCR, and normalized to the housekeeping gene 18S rRNA. The comparative threshold cycle method was applied to determine the fold change in target gene mRNA expression after different treatments, compared with untreated control conditions.

ELISA

Eotaxin-2 ELISA (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) was used to quantify eotaxin-2 in murine BAL fluid and lung tissues. Lung tissue eotaxin-2 was normalized with total proteins in the lung homogenates.

Western Blot Analysis

Western blot analysis was performed to examine SPLUNC1 and c-Jun. Primary antibodies against SPLUNC1 (R&D Systems), phospho–c-Jun (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), c-Jun (Abcam, Cambridge, MA), and a corresponding secondary horseradish peroxidase–conjugated antibody with an enhanced chemiluminescent substrate were used to detect respective proteins.

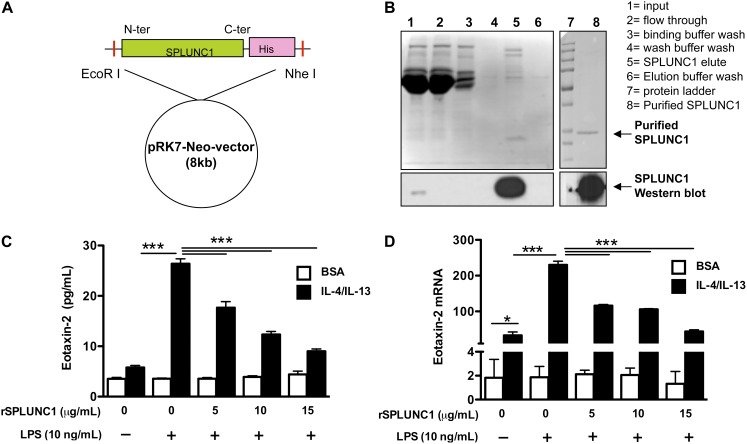

Generation of Human Recombinant SPLUNC1 Protein in Mammalian Cells

The full-length cDNA of human SPLUNC1 with a histidine (His) tag at the C-terminus was cloned into a pRK7-Neomycin (pRK7-Neo) expression vector, and the protein was expressed in the human embryonic kidney–293 (HEK293) cell line. HEK293 cells transfected with SPLUNC1 cDNA secreted His-tagged SPLUNC1 protein that was purified by affinity column chromatography, using a Ni-NTA column (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). High concentrations of salts from the elution buffer were removed using 10-kD spin filter columns (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ). Purified recombinant SPLUNC1 (rSPLUNC1) protein (> 95%) was stored at −80°C in sterile PBS with 10% glycerol solution. All reagents used for protein purification were prepared in endotoxin-free water.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical significance was determined by applying an unpaired Student t test or ANOVA, followed by the Tukey post hoc test among various treatment groups. A correlation analysis was performed by using the Pearson correlation coefficient.

Results

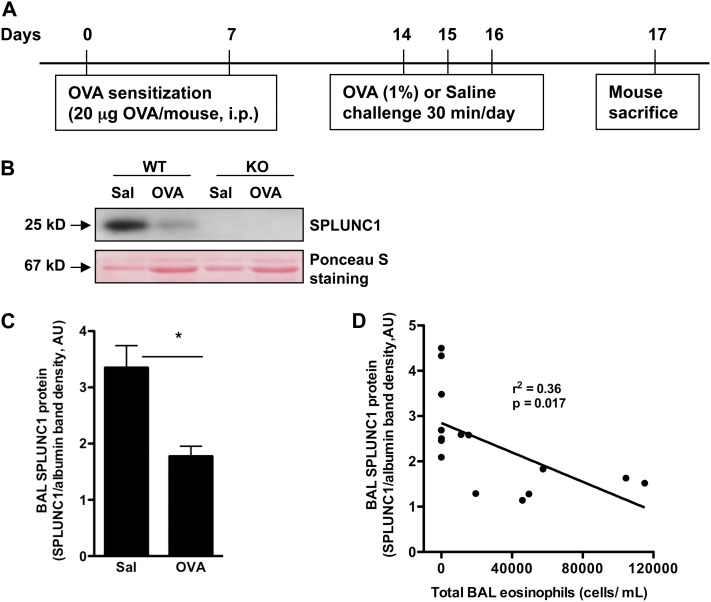

Reduced SPLUNC1 in OVA-Challenged, Wild-Type Murine Lungs

We previously showed that the Th2 cytokine IL-13 significantly reduced SPLUNC1 expression in cultured human airway epithelial cells. We also demonstrated that OVA-induced allergic inflammation in BALB/c mice significantly reduced SPLUNC1 mRNA expression in airway epithelium (10). However, a systemic investigation of reduced SPLUNC1 in allergic lungs and of its impact on airway inflammation was not previously reported, to the best of our knowledge. Using an acute OVA challenge protocol, we reproduced our previous observations by showing that allergic inflammation down-regulated SPLUNC1 concentrations in the BAL fluid of wild-type (C57BL/6 background) mice (Figures 1A–1C). Moreover, we found a significant inverse correlation between SPLUNC1 protein concentrations and eosinophils in BAL fluid (Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

Airway allergic inflammation reduces SPLUNC1 in wild-type murine lungs. (A) A schematic of ovalbumin (OVA) sensitizations and challenges to induce airway allergic inflammation in mice. Adult (6–8-week-old) C57BL/6 mice were sensitized intraperitoneally (i.p.) with OVA, challenged with aerosolized OVA or saline (Sal), and killed 24 hours after the last challenge. (B) Above, a representative Western blot shows reduced SPLUNC1 protein in the bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid (20 μl/lane) of OVA-challenged wild-type (WT) mice. Below, Ponceau S staining of the nitrocellulose membrane that was used for SPLUNC1 immunoblotting in BAL fluid. The major 67-kD protein (albumin) band was used to normalize SPLUNC1 protein in BAL fluid. (C) Densitometric analysis of SPLUNC1 protein in BAL fluid samples, which was normalized to the 67-kD protein band, as detected by Ponceau S staining (51). (D) Scatterplot shows a negative correlation between BAL SPLUNC1 and eosinophils in both saline-challenged and OVA-challenged WT mice. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 7–8 mice/group). *P < 0.05. AU, arbitrary units.

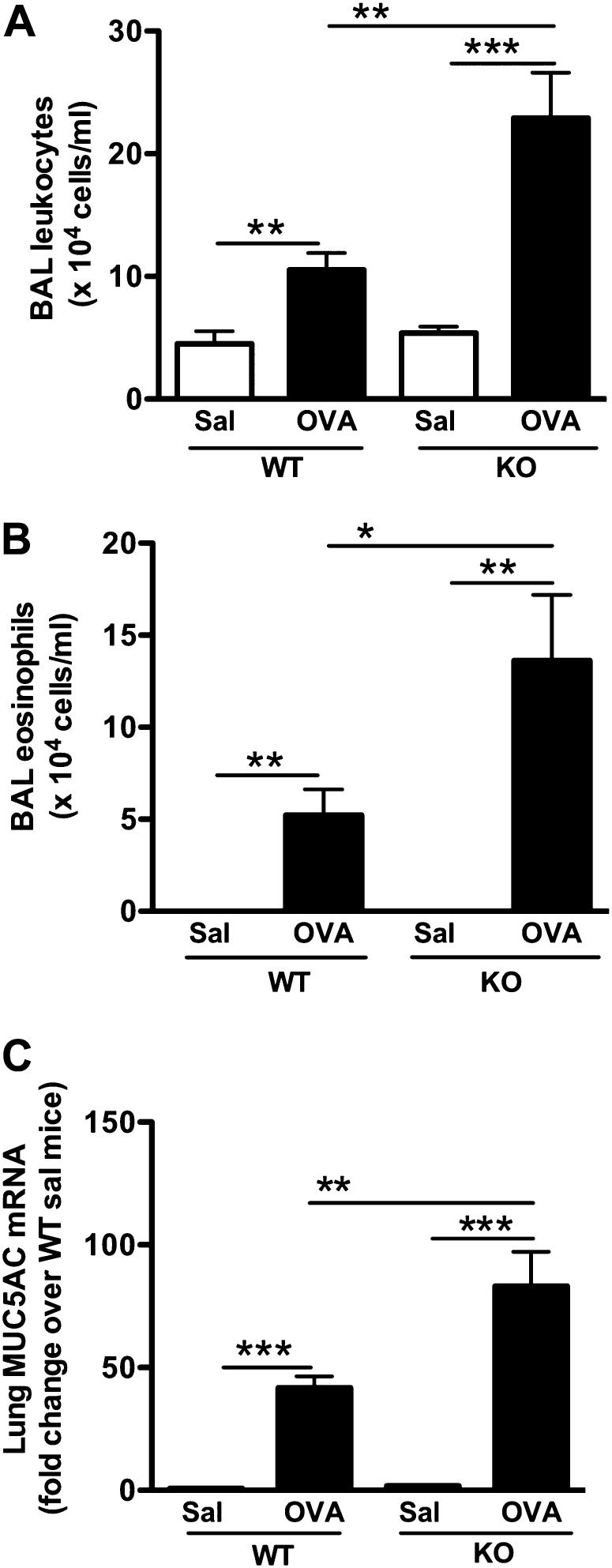

SPLUNC1 Deficiency Exaggerates OVA-Induced Murine Airway Eosinophilic Inflammation

SPLUNC1 KO mice and littermate wild-type (WT) mice were sensitized and challenged with OVA, as described in Figure 1A. OVA-sensitized/challenged SPLUNC1 KO mice, compared with WT mice, demonstrated increased airway inflammation, as indicated by increased numbers of leukocytes, including eosinophils in the lung (Figures 2A and 2B). OVA challenges in SPLUNC1 KO mice also increased lung MUC5AC mRNA expression, a hallmark of airway allergic inflammation (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

SPLUNC1 deficiency enhances airway eosinophilic inflammation. SPLUNC1 knockout (KO) and wild-type (WT) mice were sensitized and challenged with ovalbumin (OVA) or saline (Sal), as described in Figure 1A. Airway allergic inflammation was determined by quantifying BAL total leukocytes (A), eosinophils (B), and whole-lung MUC5AC mRNA (C). Data are expressed as means ± SEM (n = 7–20 mice/group). *P < 0.05. **P < 0.01. ***P < 0.001.

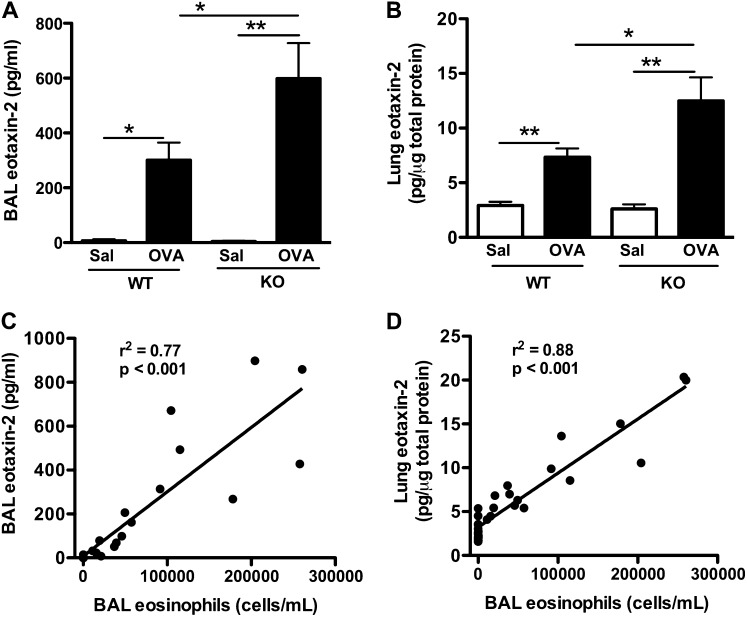

SPLUNC1 Deficiency Increases Murine Lung Eotaxin-2 Production

Because OVA-sensitized/challenged SPLUNC1 KO mice exhibited an increase in lung eosinophils, we studied the inflammatory mediators responsible for enhanced eosinophil recruitment into the lung. Previous studies demonstrated that eotaxins, including 1 and 2, display eosinophil chemotactic properties (14). Eotaxin-2 usually peaks at 24 hours after an allergen challenge, and has been considered the major eotaxin isoform in recruiting eosinophils into murine airways (15–18). Because our study outcomes were examined 24 hours after the last OVA challenge, we determined eotaxin-2 production. OVA challenges in SPLUNC1 KO versus WT mice significantly increased the eotaxin-2 protein in BAL and whole-lung tissue (Figures 3A and 3B). Eotaxin-2 protein concentrations were positively correlated with airway eosinophilia in both strains of mice (Figures 3C and 3D).

Figure 3.

SPLUNC1 deficiency enhances eotaxin-2 production in mice. SPLUNC1 knockout (KO) and wild-type (WT) mice were sensitized and challenged with ovalbumin (OVA) or saline (Sal), as described in Figure 1A. Eotaxin-2 protein concentrations in BAL fluid (A) and whole-lung tissue (B) were measured by ELISA. (C and D) Scatterplot graphs show a positive correlation between BAL or lung eotaxin-2 and BAL eosinophils, respectively. Data are expressed as means ± SEM (n = 8–26 mice/group). *P < 0.05. **P < 0.01.

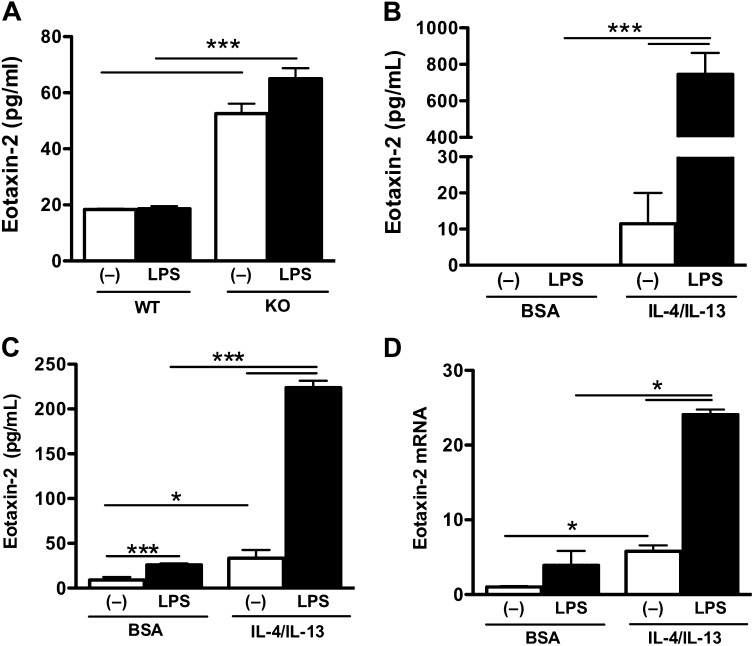

Th2 Cytokines Enhance LPS-Induced Eotaxin-2 Production in Alveolar Macrophages

Alveolar macrophages are one of the major cellular sources of eotxin-2 in the lung (19). Alveolar macrophages were isolated from saline-challenged and OVA-challenged WT and SPLUNC1 KO mice and cultured ex vivo for 24 hours, with and without LPS (10 ng/ml) stimulation. Eotaxin-2 production in the alveolar macrophages of saline-challenged WT and SPLUNC1 KO mice did not differ (data not shown). However, alveolar macrophages from OVA-sensitized/challenged SPLUNC1 KO mice produced significantly higher concentrations of eoxtain-2 at baseline compared with those from OVA-sensitized/challenged WT mice (Figure 4A). Eotaxin-2 production in the alveolar macrophages of OVA-challenged SPLUNC1 KO mice was further enhanced by LPS stimulation (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

Eotaxin-2 production in murine macrophages. (A) Alveolar macrophages were isolated from ovalbumin (OVA)–sensitized/challenged SPLUNC1 knockout (KO) and wild-type (WT) mice, and seeded onto a 48-well tissue culture plate (4 × 104 cells/well). Cells were stimulated with LPS (10 ng/ml) or medium (control) for 24 hours, and eotaxin-2 secretion was determined by ELISA. (B) Alveolar macrophages collected from OVA-naive WT mice were seeded onto a 48-well tissue culture plate (10 × 104 cells/well). Cells were treated with BSA (control) or murine recombinant IL-4/IL-13 (each at 10 ng/ml) for 2 hours, and then stimulated with LPS (10 ng/ml) for 24 hours, and eotaxin-2 secretion was determined by ELISA. (C and D) Raw 264.7 cells were seeded (5 × 105 cells/well) onto a 48-well tissue culture plate. The next day, they were treated with BSA (control) or murine IL-4/IL-13 (10 ng/ml each) for 2 hours, and then stimulated with LPS (10 ng/ml) for 24 hours, and eotaxin-2 protein (C) and mRNA (D) were measured using ELISA and real-time PCR, respectively. Data are expressed as means ± SEM (n = 3–4 replicates). *P < 0.05. ***P < 0.001.

Previous studies demonstrated that alveolar macrophages isolated from subjects with asthma are hyperresponsive to LPS, because asthmatic macrophages produce higher concentrations of proinflammatory mediators than do normal cells (8). The in vitro stimulation of murine alveolar macrophages and human peripheral blood–derived macrophages with IL-4 and/or IL-13 has been shown to increase concentrations of eotaxin-2 (20, 21). We isolated alveolar macrophages from OVA-naive WT mice and pretreated them with murine IL-4 and IL-13 (10 ng/ml each) for 2 hours. These cells were then stimulated with LPS (10 ng/ml) or medium for 24 hours. In line with previous reports (20, 21), we observed an increase of eotaxin-2 production in murine primary alveolar macrophages after IL-4 and IL-13 treatment (Figure 4B). Moreover, LPS stimulation in IL-4/IL-13–pretreated murine primary alveolar macrophages further increased eotaxin-2 production (Figure 4B). Because of the limitations of primary murine alveolar macrophages, we used a murine macrophage cell line Raw 264.7 to study the mechanisms of SPLUNC1 immunomodulatory function. Similar to our observations in murine primary alveolar macrophages, IL-4/IL-13 enhanced eotaxin-2 production in Raw 264.7 cells, and this production was significantly enhanced by LPS treatment (Figures 4C and 4D). Thus, Raw 264.7 cells represent a valid model for studying the molecular mechanisms of eotaxin-2 regulation.

SPLUNC1 Attenuates IL-4/IL-13 and LPS-Induced Eotaxin-2 Production in Macrophages

Human and murine SPLUNC1 proteins share approximately 70% homology, and they similarly inhibited Mycoplasma pneumoniae growth (10, 22). Therefore, we used a mammalian protein expression system to generate endotoxin-free human rSPLUNC1 protein (Figures 5A and 5B). The addition of rSPLUNC1 to murine IL-4/IL-13–pretreated Raw 264.7 cells dose-dependently reduced eotaxin-2 production after LPS stimulation (Figures 5C and 5D).

Figure 5.

SPLUNC1 reduces eotaxin-2 in murine macrophages. (A) Full-length human SPLUNC1 cDNA with histidine (His) tag at the C-terminus (C-ter) was cloned into a pRK-7–neo-vector and expressed in human embryonic kidney–293 (HEK293) cells by transient transfection. (B) His-tagged SPLUNC1 protein was purified by affinity chromatography. Western blotting was used to verify recombinant SPLUNC1 (rSPLUNC1) protein secretion and purity. (C and D) Raw 264.7 cells were seeded (5 × 105 cells/well) onto a 48-well tissue culture plate. The next day, cells were pretreated with BSA (control) or murine IL-4/IL-13 (10 ng/ml each) for 1 hour. Thereafter, cells were treated with rSPLUNC1 at different concentrations or with the control solution purified from HEK293 cells transfected with an empty plasmid vector. One hour later, cells were stimulated with LPS (10 ng/ml) or medium alone for 24 hours. Murine eotaxin-2 protein (C) and mRNA (D) were measured using ELISA and real-time PCR, respectively. Data are expressed as means ± SEM (n = 3–4 replicates). *P < 0.05. ***P < 0.001. N-ter, N-terminal.

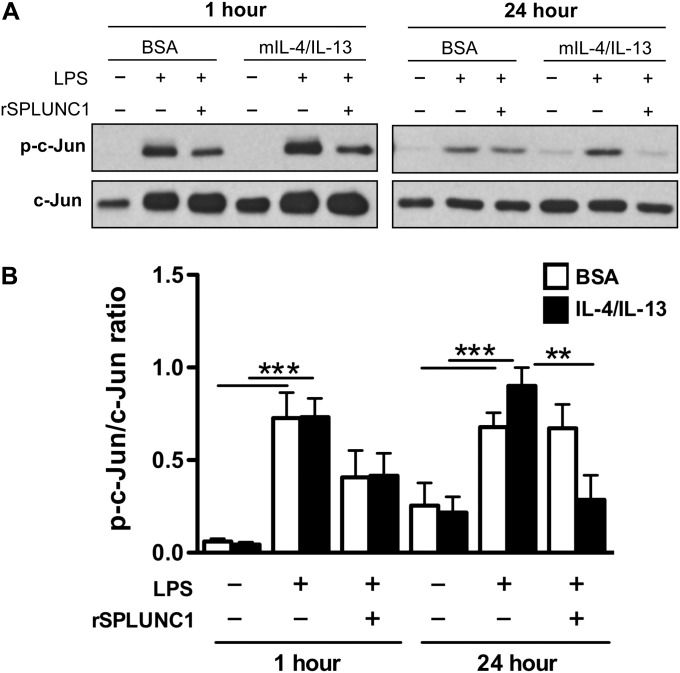

Analysis of the 5′ flanking region (−2 kb) of the murine eotaxin-2 gene (GenBank accession number NC_000071.5), using the TRANSFAC database (http://www.cbrc.jp/research/db/TFSEARCH.html), revealed the presence of two distal activator protein 1 (AP-1) [TGA(C/G)TCA] binding motifs in the promoter region. IL-4/IL-13 and LPS were shown to activate mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling in various types of cells, including macrophages (23–27). AP-1 has been described as a downstream target of MAPK signaling in different cell types (28). We studied the role of c-Jun activation, a part of the AP-1 transcription factor complex, in murine macrophage eotaxin-2 production. Our results demonstrated that the combination of IL-4/IL-13 and LPS significantly increased c-Jun (AP-1) activation in Raw 264.7 cells (Figures 6A and 6B). The addition of rSPLUNC1 protein 1 hour before LPS stimulation significantly reduced c-Jun activation at 24 hours (Figures 6A and 6B). These results suggest that the inhibition of c-Jun activation by SPLUNC1 may be involved in its inhibition of eotaxin-2 production in murine macrophages.

Figure 6.

SPLUNC1 inhibits c-Jun activation in macrophages stimulated with Th2 cytokines and LPS. Raw 264.7 cells were seeded onto a 48-well tissue culture plate (5 × 105 cells/well) and treated with BSA (control) or murine IL-4/IL-13 (each at 10 ng/ml). One hour later, rSPLUNC1 (10 μg/ml) protein or control solution was added to the cells. After another hour, cells were stimulated with LPS (10 ng/ml) for 1 hour and 24 hours to determine c-Jun activation by Western blotting. (A) Representative image of phosphorylated (p)–c-Jun (ser63) and total c-Jun Western blot. (B) Densitometric analysis of c-Jun activation, as determined by the ratio of p–c-Jun and total c-Jun proteins. Data are expressed as means ± SEM (n = 3–5 replicates). **P < 0.01. ***P < 0.001.

Discussion

In the present study, we demonstrate that SPLUNC1 concentrations are reduced in allergic murine lungs. Moreover, we find that SPLUNC1 deficiency significantly enhances airway eosinophilic inflammation along with increased eotaxin-2 production in the lung tissue, as well as in alveolar macrophages. Collectively, and for the first time to the best of our knowledge, our data suggest an inhibitory role of SPLUNC1 in eosinophil influx into allergic airways. Our findings may provide a novel approach to attenuating eosinophilic inflammation in patients with asthma.

Allergic asthma is characterized by variable airway obstruction, bronchial hyperresponsiveness, mucus hypersecretion, and airway inflammation. Airway inflammation is manifested by the infiltration of inflammatory cells, including eosinophils and Th2 cells, into the lungs. Th2 cytokines (particularly IL-13 and IL-4) regulate both innate and adaptive immunity (29–32). For example, we have shown that Th2 cytokines dampen airway innate immunity by reducing TLR2 signaling and SPLUNC1 expression in the airways (10, 33, 34). SPLUNC1 is a newly identified host defense protein that was shown to protect the host from infections of respiratory pathogens, including Mycoplasma pneumoniae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (10–12). Our present study has significantly advanced previous work by showing that allergic inflammation–mediated or Th2 cytokine–mediated SPLUNC1 reduction exacerbates airway eosinophilic inflammation in OVA-challenged mice. First, after OVA challenges, SPLUNC1 KO mice demonstrated increased numbers of eosinophils in the airways, compared with WT mice. Second, we observed a significant negative correlation between SPLUNC1 and airway eosinophils in WT mice upon OVA and saline challenges. However, the correlation of SPLUNC1 and eosinophils in OVA-challenged mice alone was not as strong as that in both saline-challenged and OVA-challenged WT mice (r2 = 0.17 versus r2 = 0.36), which could be attributable to the relatively small sample size (n = 8) for OVA-challenged mice alone, and to the fact that eosinophilic inflammation can be regulated by additional mediators such as IL-5. Because the treatment of eosinophilic inflammation with anti–IL-5 antibody alone has not provided significant protection against late asthmatic responses and acute exacerbations in humans with asthma (35, 36), SPLUNC1 therapy may offer a novel approach to attenuating eosinophilic inflammation with additonal antimicrobial benefits, because respiratory infections are often associated with acute exacerbations in asthma (37, 38).

Eotaxin-2 has been established as a potent eosinophil chemoattractant in regulating airway inflammation in mice (17, 39). We observed a significant increase of eotaxin-2 production in OVA-sensitized/challenged SPLUNC1 KO mice, suggesting that SPLUNC1 may prevent airway eosinophilic inflammation by reducing eotaxin-2 production. Moreover, we observed an increase of Th2 cytokine IL-13 in OVA-challenged SPLUNC1 KO murine lungs. However, the concentration of Th1 cytokine IFN-γ was not significantly different between OVA-challenged SPLUNC1 KO and WT mice.

One of the key questions in the present study involved the way that SPLUNC1 suppresses eosinophilic inflammation in allergic lungs. To address this question, we focused on alveolar macrophage eotaxin-2 production because, for therapeutic purposes, managing innate airway cell functions, including alveolar macrophages, is relatively easier than managing adaptive immune cells such as T cells. Moreover, Pope and colleagues suggested a predominant role of eotaxin-2 in causing luminal/airway eosinophilia in mice (18). Alveolar macrophages have been described as one of the major cellular sources of extaxin-2 in the airways (19). Th2 cytokine treatment alone has been shown to enhance extaxin-2 production in alveolar macrophages and macrophages derived from human peripheral blood monocytes (20, 21). Our results show that alveolar macrophages pre-exposed to an allergic milieu or Th2 cytokines become hyperresponsive to LPS, because eoxtain-2 was synergistically increased in these cells. This synergetic increase in eotaxin-2 production may be attributable to LPS-induced proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and TGF-β, which in collaboration with Th2 cytokines have been shown to enhance eotaxin production synergistically in fibroblasts, smooth muscle cells, and epithelial cells (40, 41). However, further studies are needed to confirm these mechanisms in macrophages.

By using SPLUNC1 KO mice, we demonstrate, for the first time to the best of our knowledge, that SPLUNC1 inhibits eotaxin-2 production in OVA-challenged mice, thus reducing airway allergic inflammation, because the lack of SPLUNC1 in vivo increased lung tissue as well as macrophage eotaxin-2 production. Furthermore, SPLUNC1 protein directly reduced eotaxin-2 production in macrophages that had been pre-exposed to IL-4/IL-13, and then stimulated with LPS (Figures 5B and 5C). Our data support a previous study showing reduced concentrations of airway eosinophils in human SPLUNC1–overexpressing mice with OVA challenges (42). However, in that study, the mechanisms of eosinophil regulation by SPLUNC1 were not examined. Our results provide a plausible mechanism for the regulation by SPLUNC1 of airway allergic inflammation. Therefore, SPLUNC1 has potential therapeutic applications in reducing airway inflammation and recurrent bacterial infections in Th2 cytokine–exposed airways.

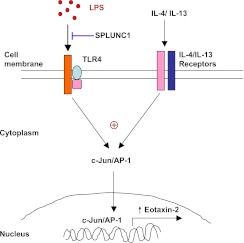

It remains unclear how SPLUNC1 down-regulates eotaxin-2 production in macrophages stimulated with Th2 cytokines and LPS. SPLUNC1 may bind to LPS (43, 44), thus reducing LPS binding to TLR4 or its coreceptors (Figure 7). One of the signatures of TLR4 signaling activation after LPS stimulation involves the activation of c-Jun, a member of the AP-1 transcription factor family, which can be activated by MAPKs (23, 28, 45). Interestingly, Th2 cytokines also activate c-Jun (46–48). The activation of c-Jun, as determined by its phosphorylation at different sites, has been shown to regulate c-Jun binding to gene promoters, c-Jun protein stability, and its dimerization with other AP-1 family members (49, 50). Analysis of 5′ flanking region of the murine eotaxin-2 gene revealed two putative AP-1 binding motifs in the distal region of the murine eoxtain-2 promoter. Our results show that LPS exposure to IL-4/IL-13–pretreated murine macrophages significantly enhanced c-Jun activation, which was suppressed by recombinant SPLUNC1 protein (Figures 6A and 6B). Whether the SPLUNC1-mediated down-regulation of c-Jun activation leads to the transcriptional repression of eotaxin-2 warrants further investigation. Together, our data suggest that SPLUNC1 attenuates eosinophilic inflammation in part by reducing eotaxin-2 production in alveolar macrophages.

Figure 7.

A schematic illustrates how SPLUNC1 may attenuate eotaxin-2 production in LPS-stimulated macrophages that are pre-exposed to IL-4 and IL-13 or an allergic airway milieu. AP-1, activator protein 1; TLR4, Toll-like receptor–4.

The present study contains several limitations. First, because multiple transcription factors may control eotaxin-2 production, the role of other transcription factors warrants future studies. Second, the way in which SPLUNC1 modulates Th2 cytokine signaling in the absence or presence of LPS or bacteria remains to be clarified. Third, because other types of cells in the lung, such as airway epithelial cells, also produce eotaxin-2, the contribution of these cells versus macrophages to lung eotaxin-2 production in its entirety needs to be addressed. Lastly, the role of SPLUNC1 in regulating airway eosinophilic inflammation can be further investigated by using human SPLUNC1 transgenic mice.

In conclusion, our data indicate that airway allergic inflammation reduces SPLUNC1. SPLUNC1 deficiency can exacerbate airway eosinophilic inflammation by enhancing eotaxin-2 production. Our study suggests a novel mechanism for persistent airway inflammation and chronic bacterial infection, as observed in a subset of patients with asthma. The administration of SPLUNC1 in asthma patients with a Th2 phenotype may provide an alternative therapy for attenuating the excessive airway inflammation associated with (or without) bacterial infection.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Fangkun Ning and Sean Smith for their technical assistance. The authors also thank Dr. Sally Wenzel at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center for discussions and critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01 HL088264 and R01 AI070175 (H.W.C.).

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2012-0064OC on April 12, 2012

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Subbarao P, Mandhane PJ, Sears MR. Asthma: epidemiology, etiology and risk factors. CMAJ 2009;181:E181–E190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haldar P, Brightling CE, Hargadon B, Gupta S, Monteiro W, Sousa A, Marshall RP, Bradding P, Green RH, Wardlaw AJ, et al. Mepolizumab and exacerbations of refractory eosinophilic asthma. N Engl J Med 2009;360:973–984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Michel O, Duchateau J, Sergysels R. Effect of inhaled endotoxin on bronchial reactivity in asthmatic and normal subjects. J Appl Physiol 1989;66:1059–1064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Michel O. Role of house-dust endotoxin exposure in aetiology of allergy and asthma. Mediators Inflamm 2001;10:301–304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reed CE, Milton DK. Endotoxin-stimulated innate immunity: a contributing factor for asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2001;108:157–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Plotz SG, Lentschat A, Behrendt H, Plotz W, Hamann L, Ring J, Rietschel ET, Flad HD, Ulmer AJ. The interaction of human peripheral blood eosinophils with bacterial lipopolysaccharide is CD14 dependent. Blood 2001;97:235–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herbert C, Scott MM, Scruton KH, Keogh RP, Yuan KC, Hsu K, Siegle JS, Tedla N, Foster PS, Kumar RK. Alveolar macrophages stimulate enhanced cytokine production by pulmonary CD4+ T-lymphocytes in an exacerbation of murine chronic asthma. Am J Pathol 2010;177:1657–1664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Catena E, Mazzarella G, Peluso GF, Micheli P, Cammarata A, Marsico SA. Phenotypic features and secretory pattern of alveolar macrophages in atopic asthmatic patients. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis 1993;48:6–15 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou HD, Fan SQ, Zhao J, Huang DH, Zhou M, Liu HY, Zeng ZY, Yang YX, Huang H, Li XL, et al. Tissue distribution of the secretory protein, SPLUNC1, in the human fetus. Histochem Cell Biol 2006;125:315–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chu HW, Thaikoottathil J, Rino JG, Zhang G, Wu Q, Moss T, Refaeli Y, Bowler R, Wenzel SE, Chen Z, et al. Function and regulation of SPLUNC1 protein in mycoplasma infection and allergic inflammation. J Immunol 2007;179:3995–4002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gally F, Di YP, Smith SK, Minor MN, Liu Y, Bratton DL, Frasch SC, Michels NM, Case SR, Chu HW. SPLUNC1 promotes lung innate defense against Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection in mice. Am J Pathol 2011;178:2159–2167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lukinskiene L, Liu Y, Reynolds SD, Steele C, Stripp BR, Leikauf GD, Kolls JK, Di YP. Antimicrobial activity of PLUNC protects against Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. J Immunol 2011;187:382–390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jonasson S, Hedenstierna G, Hjoberg J. Concomitant administration of nitric oxide and glucocorticoids improves protection against bronchoconstriction in a murine model of asthma. J Appl Physiol 2010;109:521–531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lloyd C. Chemokines in allergic lung inflammation. Immunology 2002;105:144–154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ying S, Robinson DS, Meng Q, Barata LT, McEuen AR, Buckley MG, Walls AF, Askenase PW, Kay AB. C–C chemokines in allergen-induced late-phase cutaneous responses in atopic subjects: association of eotaxin with early 6-hour eosinophils, and of eotaxin-2 and monocyte chemoattractant protein–4 with the later 24-hour tissue eosinophilia, and relationship to basophils and other C–C chemokines (monocyte chemoattractant protein–3 and RANTES). J Immunol 1999;163:3976–3984 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heiman AS, Abonyo BO, Darling-Reed SF, Alexander MS. Cytokine-stimulated human lung alveolar epithelial cells release eotaxin-2 (CCL24) and eotaxin-3 (CCL26). J Interferon Cytokine Res 2005;25:82–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ben-Yehuda C, Bader R, Puxeddu I, Levi-Schaffer F, Breuer R, Berkman N. Airway eosinophil accumulation and eotaxin-2/CCL24 expression following allergen challenge in BALB/c mice. Exp Lung Res 2008;34:467–479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pope SM, Zimmermann N, Stringer KF, Karow ML, Rothenberg ME. The eotaxin chemokines and CCR3 are fundamental regulators of allergen-induced pulmonary eosinophilia. J Immunol 2005;175:5341–5350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ying S, Meng Q, Zeibecoglou K, Robinson DS, Macfarlane A, Humbert M, Kay AB. Eosinophil chemotactic chemokines (eotaxin, eotaxin-2, RANTES, monocyte chemoattractant protein–3 (MCP-3), and MCP-4), and C–C chemokine receptor 3 expression in bronchial biopsies from atopic and nonatopic (intrinsic) asthmatics. J Immunol 1999;163:6321–6329 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu Q, Martin RJ, LaFasto S, Chu HW. A low dose of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection enhances an established allergic inflammation in mice: the role of the prostaglandin E2 pathway. Clin Exp Allergy 2009;39:1754–1763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Watanabe K, Jose PJ, Rankin SM. Eotaxin-2 generation is differentially regulated by lipopolysaccharide and IL-4 in monocytes and macrophages. J Immunol 2002;168:1911–1918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chu HW, Gally F, Thaikoottathil J, Janssen-Heininger YM, Wu Q, Zhang G, Reisdorph N, Case S, Minor M, Smith S, et al. SPLUNC1 regulation in airway epithelial cells: role of Toll-like receptor 2 signaling. Respir Res 2010;11:155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Monick MM, Hunninghake GW. Activation of second messenger pathways in alveolar macrophages by endotoxin. Eur Respir J 2002;20:210–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DeFranco AL, Hambleton J, McMahon M, Weinstein SL. Examination of the role of MAP kinase in the response of macrophages to lipopolysaccharide. Prog Clin Biol Res 1995;392:407–420 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bhattacharjee A, Pal S, Feldman GM, Cathcart MK. HCK is a key regulator of gene expression in alternatively activated human monocytes. J Biol Chem 2011;286:36709–36723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee PJ, Zhang X, Shan P, Ma B, Lee CG, Homer RJ, Zhu Z, Rincon M, Mossman BT, Elias JA. ERK1/2 mitogen-activated protein kinase selectively mediates IL-13–induced lung inflammation and remodeling in vivo. J Clin Invest 2006;116:163–173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Olsson S, Sundler R. The role of lipid rafts in LPS-induced signaling in a macrophage cell line. Mol Immunol 2006;43:607–612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karin M. The regulation of AP-1 activity by mitogen-activated protein kinases. J Biol Chem 1995;270:16483–16486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.D'Andrea A, Ma X, Aste-Amezaga M, Paganin C, Trinchieri G. Stimulatory and inhibitory effects of interleukin (IL)–4 and IL-13 on the production of cytokines by human peripheral blood mononuclear cells: priming for IL-12 and tumor necrosis factor alpha production. J Exp Med 1995;181:537–546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Varin A, Mukhopadhyay S, Herbein G, Gordon S. Alternative activation of macrophages by IL-4 impairs phagocytosis of pathogens but potentiates microbial-induced signalling and cytokine secretion. Blood 2010;115:353–362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roy S, Charboneau R, Melnyk D, Barke RA. Interleukin-4 regulates macrophage interleukin-12 protein synthesis through a c-Fos mediated mechanism. Surgery 2000;128:219–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wenzel SE, Trudeau JB, Barnes S, Zhou X, Cundall M, Westcott JY, McCord K, Chu HW. TGF-beta and IL-13 synergistically increase eotaxin-1 production in human airway fibroblasts. J Immunol 2002;169:4613–4619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu Q, Martin RJ, Lafasto S, Efaw BJ, Rino JG, Harbeck RJ, Chu HW. Toll-like receptor 2 down-regulation in established mouse allergic lungs contributes to decreased mycoplasma clearance. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008;177:720–729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Case SR, Martin RJ, Jiang D, Minor MN, Chu HW. MicroRNA-21 inhibits Toll-like receptor 2 agonist-induced lung inflammation in mice. Exp Lung Res 2011;37:500–508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leckie MJ, ten Brinke A, Khan J, Diamant Z, O'Connor BJ, Walls CM, Mathur AK, Cowley HC, Chung KF, Djukanovic R, et al. Effects of an interleukin-5 blocking monoclonal antibody on eosinophils, airway hyper-responsiveness, and the late asthmatic response. Lancet 2000;356:2144–2148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zarogiannis S, Gourgoulianis KI, Kostikas K. Anti–interleukin-5 therapy and severe asthma. N Engl J Med 2009;360:2576, author reply 2577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang YJ, Nelson CE, Brodie EL, Desantis TZ, Baek MS, Liu J, Woyke T, Allgaier M, Bristow J, Wiener-Kronish JP, et al. Airway microbiota and bronchial hyperresponsiveness in patients with suboptimally controlled asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011;127:372–381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Newcomb DC, Peebles RS., Jr Bugs and asthma: a different disease? Proc Am Thorac Soc 2009;6:266–271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ravensberg AJ, Ricciardolo FL, van Schadewijk A, Rabe KF, Sterk PJ, Hiemstra PS, Mauad T. Eotaxin-2 and eotaxin-3 expression is associated with persistent eosinophilic bronchial inflammation in patients with asthma after allergen challenge. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2005;115:779–785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Terada N, Hamano N, Nomura T, Numata T, Hirai K, Nakajima T, Yamada H, Yoshie O, Ikeda-Ito T, Konno A. Interleukin-13 and tumour necrosis factor–alpha synergistically induce eotaxin production in human nasal fibroblasts. Clin Exp Allergy 2000;30:348–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hirst SJ, Hallsworth MP, Peng Q, Lee TH. Selective induction of eotaxin release by interleukin-13 or interleukin-4 in human airway smooth muscle cells is synergistic with interleukin-1beta and is mediated by the interleukin-4 receptor alpha–chain. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;165:1161–1171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wright PL, Yu J, Di YP, Homer RJ, Chupp G, Elias JA, Cohn L, Sessa WC. Epithelial reticulon 4B (Nogo-B) is an endogenous regulator of Th2-driven lung inflammation. J Exp Med 2010;207:2595–2607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ghafouri B, Kihlstrom E, Tagesson C, Lindahl M. PLUNC in human nasal lavage fluid: multiple isoforms that bind to lipopolysaccharide. Biochim Biophys Acta 2004;1699:57–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhou HD, Li GY, Yang YX, Li XL, Sheng SR, Zhang WL, Zhao J. Intracellular co-localization of SPLUNC1 protein with nanobacteria in nasopharyngeal carcinoma epithelia HNE1 cells depended on the bactericidal permeability increasing protein domain. Mol Immunol 2006;43:1864–1871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hambleton J, Weinstein SL, Lem L, DeFranco AL. Activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase in bacterial lipopolysaccharide-stimulated macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1996;93:2774–2778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fujisawa T, Joshi BH, Puri RK. IL-13 regulates cancer invasion and metastasis through IL-13Ralpha2 via ERK/AP-1 pathway in mouse model of human ovarian cancer. Int J Cancer (In press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wu Q, Jiang D, Smith S, Thaikoottathil J, Martin RJ, Bowler RP, Chu HW. IL-13 dampens human airway epithelial innate immunity through induction of IL-1 receptor–associated kinase M. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2012;129:825–833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lorentz A, Wilke M, Sellge G, Worthmann H, Klempnauer J, Manns MP, Bischoff SC. IL-4–induced priming of human intestinal mast cells for enhanced survival and Th2 cytokine generation is reversible and associated with increased activity of ERK1/2 and c-Fos. J Immunol 2005;174:6751–6756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hess J, Angel P, Schorpp-Kistner M. AP-1 subunits: quarrel and harmony among siblings. J Cell Sci 2004;117:5965–5973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.van Dam H, Castellazzi M. Distinct roles of Jun: Fos and Jun: ATF dimers in oncogenesis. Oncogene 2001;20:2453–2464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kliment CR, Englert JM, Gochuico BR, Yu G, Kaminski N, Rosas I, Oury TD. Oxidative stress alters syndecan-1 distribution in lungs with pulmonary fibrosis. J Biol Chem 2009;284:3537–3545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.