Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the potential impact of revised criteria for mild cognitive impairment (MCI), developed by a Workgroup sponsored by the National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer’s Association, on the diagnosis of very mild and mild Alzheimer disease (AD) dementia.

Design

Retrospective review of ratings of functional impairment across diagnostic categories. Participants: The functional ratings of individuals (N = 17,535) with normal cognition, MCI, or AD dementia who were evaluated at Alzheimer’s Disease Centers and submitted to the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center were assessed in accordance with the definition of “functional independence” allowed by the revised criteria.

Methods

Pairwise demographic differences between the 3 diagnostic groups were tested using t-tests for continuous variables and chi-square for categorical variables.

Results

Almost all (99.8%) of individuals currently diagnosed with very mild AD dementia and the large majority (92.7%) of those diagnosed with mild AD dementia could be reclassified as MCI with the revised criteria, based on their level of impairment in the Clinical Dementia Rating domains for performance of instrumental activities of daily living in the community and at home. Large percentages of these AD dementia individuals also meet the revised “functional independence” criterion for MCI as measured by the Functional Assessment Questionnaire.

Conclusions

The categorical distinction between MCI and milder stages of Alzheimer dementia has been compromised by the revised criteria. The resulting diagnostic overlap supports the premise that “MCI due to AD” represents the earliest symptomatic stage of AD.

Keywords: Dementia Diagnosis, Alzheimer disease, MCI

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) aims to identify cognitive decline in its earliest stages. It is a popular concept: the National Institute on Aging (NIA) in 2004 noted MCI as a top discovery of the Alzheimer’s Disease Centers (ADCs) program,1 and in 2010 over 1220 publications listed “MCI” in the title, abstract, or keywords (Elsevier SciVerse Scopus). Given its importance, the NIA and the Alzheimer’s Association convened a Workgroup to update criteria for MCI. The revised criteria recently were published,2 as were revised criteria for Alzheimer disease (AD) dementia3 and for the preclinical stage of AD.4 A key criterion for MCI is the absence of dementia.2 The revised criteria for AD dementia, which are comparable to widely used criteria for dementia of the Alzheimer type (DAT),5 stipulate that impairment must be present in two or more cognitive domains and must interfere with the ability to function in usual activities. The original diagnosis of MCI6,7 was limited to individuals with cognitive impairment in a single domain (memory), thus distinguishing MCI from dementia, but more recently its differention from dementia has come to rest solely on the preservation of functional activities.8,9 The revised criteria for MCI2, however, allow considerable latitude as to what represents functional independence and thus blur the categorical distinction between MCI and dementia.

Initially proposed as a predictor of progressive cognitive decline in older adults,10 MCI later was defined as an amnestic syndrome that denoted a transitional stage between aging and dementia (particularly dementia caused by AD).6,7 With experience, however, came the realization that individuals classified as MCI frequently were impaired in cognitive domains other than memory.11,12 Criteria for MCI thus were broadened to include both non-amnestic presentations and the involvement of multiple cognitive domains but continued to require “essentially normal” functional activities.8,9 The recently published revised criteria for MCI require: 1) change in cognition recognized by the affected individual or observers; 2) objective impairment in one or more cognitive domains; 3) independence in functional activities; and 4) absence of dementia.2 Although on the surface these revised criteria conform to earlier definitions,8,9 the revised criteria operationalize “independence in functional activities” more expansively than before. For example, “mild problems” in performing daily activities such as shopping, paying bills, and cooking are permissible, as is dependency on aids or assistance to complete such activities.2 This interpretation of “independence in functional activities” thus has the potential to characterize as MCI some individuals who now are diagnosed with very mild and mild AD dementia.

To assess this potential, the functional ratings of participants enrolled at federally-funded Alzheimer’s Disease Centers (ADCs) with clinical and cognitive data maintained by the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC; U01 AG016976; W. Kukull, Principal Investigator) were evaluated. The degree of functional impairment as assessed by two ratings of activities of daily living, the Functional Activities Questionnaire (FAQ)13 and the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR),14 was determined for NACC participants with MCI and for participants with very mild and mild AD dementia (all diagnoses were made prior to the publication of the revised criteria for MCI). These functional ratings then were interpreted in accordance with the definition in the revised criteria for MCI of “independence in functional activities” to examine their potential to change current diagnoses.

METHODS

Data were obtained from participants entered into the NACC between September, 2005, and May 20, 2011, who were diagnosed by ADC clinicians as being cognitively normal, having MCI, or having probable AD; standard criteria were used to diagnose MCI8,9 and probable AD.15 Diagnoses were made by a single clinician or by consensus conference. A uniform assessment battery to characterize individuals with MCI and probable AD in comparison with cognitively normal aging was developed by a Clinical Task Force of the ADCs and implemented at each ADC in September, 2005. This Uniform Data Set (UDS)16,17 defines the standard clinical and cognitive observations that are collected longitudinally on ADC participants; the UDS data are submitted to NACC. Incorporated into the UDS is the FAQ, a measure of the participant’s functional impairment as rated by an informant. The FAQ rates the participant’s current ability to perform 10 instrumental activities of daily living: 1) household finances; 2) assembling financial and tax documents; 3) shopping; 4) hobbies; 5) simple kitchen functions, such as heating water; 6) preparing a meal; 7) monitoring current events; 8) comprehending televised programs or a book; 9) monitoring family occasions or personal medications; and 10) transportation (e.g., driving). Performance in each of the 10 activities is rated along a 4-point scale, from no difficulty in performance (0), to difficulty but still performing “by self” (1), to performing with assistance (2), to dependent (3). Only those activities that the participant previously performed are rated and, in the UDS, reflect impairment due only to cognitive loss. A conservative operationalization of the functional “independence” permitted by the revised criteria for MCI is considered here to include FAQ scores of 0 or 1 for each rated activity. As the revised criteria for MCI allow activities to be performed with assistance, also considered here is a more liberal interpretation where FAQ ratings of 0, 1, and 2 could be compatible with this definition of functional “independence”.

The UDS also includes the CDR. Using both informant report and an examination of the participant, an experienced clinician rates the presence or absence of cognitive and functional loss and, when present, rates severity in each of 6 domains: Memory, Orientation, Judgment and Problem Solving, and function in Community Affairs (CA), Home & Hobbies (HH), and Personal Care. The clinician synthesizes all relevant information, including that obtained with the FAQ, in rating instrumental activities of daily living in the community (CA) and at home (HH). Only impairment caused by cognitive loss is rated on a 5-point scale as none (0), very mild (0.5), mild (1), moderate (2), or severe (3). An algorithm combines the individual ratings in each of the 6 domains to derive a global CDR score, where CDR 0 indicates cognitive normality and CDR 0.5, 1, 2, and 3 indicate questionable/very mild, mild, moderate, and severe dementia.14 The CDR has demonstrated reliability in multicenter studies.18,19 Qualitative descriptions for different levels of impairment serve as anchor points to guide ratings of function in the CA and HH domains, or “boxes”, and are shown in Table 1. For both the CA and HH boxes, “slight” impairment is rated as 0.5. Mild impairment at the 1 level for CA translates to pretense of independent function (may engage in activities and appear “normal”, although does not function without assistance) and to independence in HH for simpler activities but not more complex ones. Impairment at the CDR 0.5 level for either CA and HH conservatively is consistent with revised MCI criteria for functional “independence”, and impairment at the CDR 1 level for CA and HH also could be interpreted more liberally as compatible with the “mild problems” in shopping, paying bills, and meal preparation and the need for assistance allowed by the revised criteria.

Table 1.

Anchor Points For Clinical Dementia Rating Levels in Functional Domains

| 0 | 0.5 | 1 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Community Affairs | Independent function at usual level | Slight impairment in these activities | Although may still be engaged in activities, unable to function independently; appears normal to casual inspection |

| Home and Hobbies | Home, hobbies, and intellectual interests well-maintained | Home, hobbies, and intellectual interests slightly impaired | Mild impairment; more difficult chores and hobbies abandoned |

| FAQ* Equivalency | Normal | Has difficulty but does by self | Requires assistance |

FAQ = Functional Assessment Questionnaire

Analyses

Data were analyzed from the first UDS assessment for NACC participants with non-missing data on age, gender, race, education, CA and HH box scores, and who had non-missing data on one or more of the FAQ items. Participants in the cognitively normal group were required to be CDR 0. Eligibility criteria for the MCI group included all subtypes (Amnestic MCI – memory impairment only; Amnestic MCI – memory impairment plus impairment in one or more other domains; Non-amnestic MCI – single domain; and Non-amnestic MCI – multiple domains),8,9 global CDR=0.5, and the clinician’s indication that the participant did not have dementia at that assessment. Data from participants younger than 50 years of age at the index assessment and individuals with Down syndrome were excluded from analyses. For persons who met eligibility criteria at more than one assessment (e.g., a cognitively normal participant who later developed AD dementia), data from the first assessment meeting eligibility criteria were used in the analyses.

Participants were assigned to one of six groups based on their global CDR and diagnosis: CDR 0, CDR 0.5/MCI, CDR 0.5/AD, CDR 1/AD, CDR 2/AD, and CDR 3/AD. Two levels of FAQ ratings and CDR box scores for CA and HH that meet the revised criteria’s operationalized functional “independence” for a diagnosis of MCI were examined: 1) conservative, with FAQ ratings of 0 or 1 and CDR box scores of 0 or 0.5, and 2) liberal, with FAQ ratings of 0, 1, or 2 and CDR box scores of 0, 0.5, and 1. The number and percent of participants at each CA and HH box score level and each FAQ item was reported for each group.

Pairwise demographic differences between the CDR 0, CDR 0.5/MCI, and CDR 0.5/AD groups were tested (t-tests for continuous variables, chi-square for categorical variables). Logistic regression using bias correction was employed to test differences across the CDR 0, CDR 0.5/MCI, and CDR 0.5/AD groups in the likelihood of functional impairment while adjusting for the effects of age, sex, education, race, and apolipoprotein E genotype. The CDR 0.5/MCI group was used as the reference category in these analyses.

RESULTS

There were 17,535 individuals from 33 ADCs entered into the NACC database who met eligibility criteria, including a diagnosis of normal cognition (n = 6,379), MCI (n = 4,947), or probable AD (n = 6,209). The mean age of the total sample was 74.6y (standard deviation [SD] 9.5y; range 50–110y) with a mean educational attainment of 14.7y (SD 3.5y). Fifty-nine percent were women, 79.8% were white, and 14.9% were African American. Of the 9,557 individuals for whom their apolipoprotein E allele status was known, 3,994 (41.7%) were carriers of at least one ε4 allele.

Table 2 shows the demographic characteristics of the sample as a function of CDR stage and diagnosis at time of entry into the NACC database, with statistical tests of differences between the groups of greatest interest (CDR 0 vs CDR 0.5/MCI and CDR 0.5/AD versus CDR 0.5/MCI). The CDR 0.5/MCI and the CDR 0.5/AD groups statistically were similar with regard to age and sex. For each of the remaining demographic variables, there were significant differences between CDR 0, CDR 0.5/MCI and CDR 0.5/AD groups. Regardless of how functional impairment was operationalized, the CDR 0 group was less likely, and the CDR 0.5/AD group more likely, than the CDR 0.5/MCI group to be functionally impaired. As expected, given the large sample sizes, all differences were statistically significant (see Supplementary Table).

Table 2.

Demographics.

| CDR 0 (N=6379) | CDR 0.5/MCI (N=4947) | CDR 0.5/AD (N=1684) | CDR 1/AD (N=2836) | CDR 2/AD (N=1127) | CDR 3/AD (N=562) | P-values for Differences Between the Groups | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N/Mean | %/SD | N/Mean | %/SD | N/Mean | %/SD | N/Mean | %/SD | N/Mean | %/SD | N/Mean | %/SD | CDR 0 vs. CDR 0.5/MCI | CDR 0.5/MCI vs. CDR 0.5/AD | CDR 0 vs. CDR 0.5/AD | |

| Age, y | 71.9 | 9.3 | 75.6 | 9.2 | 75.5 | 8.9 | 76.4 | 9.2 | 78.0 | 9.4 | 77.9 | 9.8 | <.0001 | .7142 | <.0001 |

| Educ, y | 15.5 | 3.0 | 14.8 | 3.5 | 14.5 | 3.4 | 14.1 | 3.8 | 13.0 | 4.2 | 13.2 | 4.2 | <.0001 | .0026 | <.0001 |

| Women, % | 4282 | 67.1% | 2543 | 51.4% | 892 | 53.0% | 1614 | 56.9% | 715 | 63.4% | 337 | 60.0% | <.0001 | .2672 | <.0001 |

| Race, % | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | ||||||||||||

| White | 5019 | 78.7% | 3972 | 80.3% | 1434 | 85.2% | 2284 | 80.5% | 835 | 74.1% | 442 | 78.7% | |||

| African American | 1126 | 17.7% | 659 | 13.3% | 183 | 10.9% | 371 | 13.1% | 203 | 18.0% | 74 | 13.2% | |||

| Other | 234 | 3.7% | 316 | 6.4% | 67 | 4.0% | 181 | 6.4% | 89 | 7.9% | 46 | 8.2% | |||

| Mini Mental State Examination score | 28.9 | 1.5 | 27.0 | 2.5 | 23.9 | 3.7 | 20.5 | 4.6 | 14.2 | 5.5 | 5.4 | 5.4 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| CDR Sum of Boxes | 0.02 | 0.1 | 1.4 | 0.9 | 2.9 | 1.0 | 5.9 | 1.4 | 11.3 | 1.6 | 17.2 | 1.1 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| APOE genotype | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | ||||||||||||

| e3, e3 | 2214/3817 | 58.0% | 1290/2680 | 48.1% | 297/852 | 34.9% | 469/1341 | 35.0% | 214/571 | 37.5% | 100/296 | 33.8% | |||

| e3, e4 | 894/3817 | 23.4% | 854/2680 | 31.9% | 366/852 | 43.0% | 563/1341 | 42.0% | 252/571 | 44.1% | 151/296 | 51.0% | |||

| e3, e2 | 498/3817 | 13.1% | 265/2680 | 9.9% | 52/852 | 6.1% | 90/1341 | 6.7% | 20/571 | 3.5% | 7/296 | 2.4% | |||

| e4, e4 | 94/3817 | 2.5% | 177/2680 | 6.6% | 102/852 | 12.0% | 182/1341 | 13.6% | 67/571 | 11.7% | 34/296 | 11.5% | |||

| e4, e2 | 89/3817 | 2.3% | 82/2680 | 3.1% | 32/852 | 3.8% | 36/1341 | 2.7% | 15/571 | 2.6% | 4/296 | 1.4% | |||

| e2, e2 | 28/3817 | 0.7% | 12/2680 | 0.5% | 3/852 | 0.4% | 1/1341 | 0.1% | 3/571 | 0.5% | 0/296 | 0.0% | |||

| Dx by consensus conference, % | 4517 | 70.8% | 4122 | 83.3% | 1196 | 71.0% | 2218 | 78.2% | 816 | 72.4% | 432 | 76.9% | |||

Table 3 shows the severity of functional impairment of the NACC sample. More than two thirds (68.3%) of CDR 0.5/MCI individuals were performing normally in community activities (CA box score = 0) versus only 23.9% of CDR 0.5/AD individuals; for CDR 1/AD individuals, only 0.2% were performing normally. Very similar percentages were found for normal performance of home activities (HH box score = 0) for these three diagnostic groups. By virtue of a score of 3 (“does with assistance”) on any of the four FAQ items (assembling tax records; writing checks; preparing a balanced meal; shopping) that are equivalent to the “mild problems in paying bills, preparing a meal, or shopping” of the revised criteria for MCI,2 41.8% of CDR 0.5/AD individuals are impaired versus 79.4% of CDR 1/AD individuals (p<.0001). When either a score of “2” or “3” for these FAQ items is considered, 73.8% of CDR 0.5/AD individuals versus 94.7% of CDR 1/AD individuals are impaired (p<.0001).

Table 3.

Functional perfomance for each group as reflected in Community Affairs box score, Home and Hobbies box score, and Functional Assessment Questionnaire (FAQ) items.

| CDR 0 (N=6379)

|

CDR 0.5/MCI (N=4947)

|

CDR 0.5/AD (N=1684)

|

CDR 1/AD (N=2836)

|

CDR 2/AD (N=1127)

|

CDR 3/AD (N=562)

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Community Affairs Box Score | ||||||||||||

| 0 | 6358 | 99.7 | 3377 | 68.3 | 403 | 23.9 | 6 | 0.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| 0.5 | 21 | 0.3 | 1490 | 30.1 | 1115 | 66.2 | 310 | 10.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0.0 | 78 | 1.6 | 164 | 9.7 | 2315 | 81.6 | 112 | 9.9 | 0 | 0.0 |

| ≥2 | 0 | 0.00 | 2 | 0.04 | 2 | 0.11 | 205 | 7.2 | 1015 | 90.1 | 562 | 100.0 |

| Home and Hobbies Box Score | ||||||||||||

| 0 | 6365 | 99.8 | 3312 | 67.0 | 406 | 24.1 | 28 | 1.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| 0.5 | 14 | 0.2 | 1503 | 30.4 | 1017 | 60.4 | 269 | 9.5 | 3 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0.0 | 127 | 2.6 | 254 | 15.1 | 2172 | 76.6 | 70 | 6.2 | 1 | 0.2 |

| ≥2 | 0 | 0.0 | 5 | 0.1 | 7 | 0.4 | 367 | 12.9 | 1054 | 93.5 | 561 | 99.8 |

| FAQ items endorsed with “Normal” | ||||||||||||

| Writing checks… | 6051/6197 | 97.6 | 2911/1540 | 65.4 | 363/1414 | 25.7 | 140/2515 | 5.6 | 5/1041 | 0.5 | 2/549 | 0.4 |

| Assembling tax records… | 5869/6052 | 97.0 | 2567/4152 | 61.8 | 291/1271 | 22.9 | 99/2350 | 4.2 | 4/1007 | 1.4 | 2/533 | 0.4 |

| Shopping alone… | 6213/6321 | 98.3 | 3740/4814 | 77.7 | 779/1621 | 48.1 | 332/2745 | 12.1 | 11/1102 | 1.0 | 1/558 | 0.2 |

| Playing a game of skill… | 5997/6054 | 99.1 | 3596/4329 | 83.1 | 767/1400 | 54.8 | 532/2415 | 22.0 | 50/1011 | 5.0 | 5/548 | 0.9 |

| Heating water… | 6270/6347 | 98.8 | 4354/4866 | 89.5 | 1292/1641 | 78.7 | 1281/2729 | 46.9 | 121/1091 | 11.1 | 7/560 | 1.3 |

| Preparing a balanced meal | 6011/6095 | 98.6 | 3450/4276 | 80.7 | 732/1337 | 54.8 | 410/2389 | 17.2 | 20/1043 | 1.9 | 2/556 | 0.4 |

| Keeping track of current events | 6285/6361 | 98.8 | 3672/4901 | 74.9 | 755/1662 | 45.4 | 427/2794 | 15.3 | 32/1108 | 2.9 | 2/560 | 0.4 |

| Paying attention to and understanding a TV program… | 6303/6371 | 98.9 | 3983/4923 | 80.9 | 899/1673 | 53.7 | 745/2822 | 26.4 | 93/1115 | 8.3 | 5/560 | 0.9 |

| Remembering appointments… | 6088/6366 | 95.6 | 2522/4918 | 51.3 | 336/1678 | 20.0 | 114/2821 | 4.0 | 6/1115 | 0.5 | 2/561 | 0.4 |

| Traveling out of the neighborhood… | 6182/6350 | 97.4 | 3242/4886 | 66.4 | 548/1657 | 33.1 | 201/2795 | 7.2 | 8/1109 | 0.7 | 1/560 | 0.18 |

| FAQ items endorsed with “Normal” or “Has difficulty but does by self” | ||||||||||||

| Writing checks… | 6148/6197 | 99.2 | 3742/4451 | 84.1 | 749/1414 | 53.0 | 405/2110 | 16.1 | 20/1021 | 1.9 | 3/549 | 0.6 |

| Assembling tax records… | 5981/6052 | 98.8 | 3299/853 | 79.5 | 551/1271 | 43.4 | 261/2350 | 11.1 | 12/995 | 1.2 | 2/533 | 0.4 |

| Shopping alone… | 6266/6321 | 99.1 | 4415/4814 | 91.7 | 1303/1621 | 80.4 | 887/2745 | 32.3 | 53/1102 | 4.8 | 4/558 | 0.7 |

| Playing a game of skill… | 6043/6054 | 99.8 | 4173/4329 | 96.4 | 1206/1400 | 86.1 | 1368/2415 | 56.7 | 176/1011 | 17.4 | 16/553 | 2.9 |

| Heating water… | 6335/6347 | 99.8 | 4747/4866 | 97.6 | 1549/1641 | 94.4 | 2007/2729 | 73.5 | 286/1091 | 26.2 | 12/560 | 2.1 |

| Preparing a balanced meal | 6065/6095 | 99.5 | 3962/4276 | 92.7 | 1047/1337 | 78.3 | 924/2389 | 38.7 | 69/1043 | 6.6 | 4/556 | 0.7 |

| Keeping track of current events | 6353/6361 | 99.9 | 4713/4901 | 96.2 | 1363/1662 | 82.0 | 1316/2794 | 47.1 | 142/1108 | 12.8 | 7/560 | 1.3 |

| Paying attention to and understanding a TV program… | 6364/6371 | 99.9 | 4799/4923 | 97.5 | 1482/1673 | 88.6 | 1879/2822 | 66.6 | 346/1115 | 31.0 | 23/560 | 4.1 |

| Remembering appointments… | 6339/6366 | 99.6 | 4218/4918 | 85.8 | 975/1678 | 58.1 | 612/2821 | 21.7 | 46/1121 | 4.1 | 5/561 | 0.9 |

| Traveling out of the neighborhood… | 6277/6350 | 98.9 | 4251/4886 | 87.0 | 1052/1657 | 63.5 | 652/2795 | 23.3 | 37/1109 | 3.3 | 2/560 | 0.36 |

| FAQ items rated as “Normal”, “Has difficulty but does by self”, or “Requires assistance” | ||||||||||||

| Writing checks… | 6181/6197 | 99.7 | 4194/4451 | 94.2 | 1123/1414 | 79.4 | 1039/2515 | 41.3 | 97/1041 | 9.3 | 4/549 | 0.7 |

| Assembling tax records… | 6033/6052 | 99.7 | 3814/4152 | 91.9 | 909/1271 | 71.5 | 732/2350 | 31.2 | 53/1007 | 5.3 | 4/529 | 0.8 |

| Shopping alone… | 6302/6321 | 99.7 | 4714/4814 | 97.9 | 1533/1621 | 94.6 | 1967/2745 | 71.7 | 275/1102 | 25.0 | 17/558 | 3.1 |

| Playing a game of skill… | 6047/6054 | 99.9 | 4283/4329 | 98.9 | 1349/1400 | 96.4 | 1999/2415 | 82.8 | 435/1011 | 43.0 | 37/553 | 6.7 |

| Heating water… | 6341/6347 | 99.9 | 4829/4866 | 99.2 | 1611/1641 | 98.2 | 2409/2729 | 88.3 | 495/1091 | 45.4 | 33/560 | 5.9 |

| Preparing a balanced meal | 6086/6095 | 99.9 | 4171/4276 | 97.5 | 1239/1337 | 92.7 | 1625/2389 | 68.0 | 231/1043 | 22.2 | 13/556 | 2.3 |

| Keeping track of current events | 6357/6361 | 99.9 | 4876/4901 | 99.5 | 1617/1662 | 97.3 | 2257/2794 | 80.8 | 441/1108 | 39.8 | 36/560 | 6.4 |

| Paying attention to and understanding a TV program… | 6366/6371 | 99.9 | 4907/4923 | 99.7 | 1645/1673 | 98.3 | 2613/2822 | 92.6 | 740/1115 | 66.4 | 78/560 | 13.9 |

| Remembering appointments… | 6361/6366 | 99.9 | 4813/4918 | 97.9 | 1541/1678 | 91.8 | 1812/2821 | 64.2 | 249/1121 | 22.2 | 24/561 | 4.3 |

| Traveling out of the neighborhood… | 6318/6350 | 99.5 | 4609/4886 | 94.3 | 1395/1657 | 84.2 | 1376/2795 | 49.2 | 117/1109 | 10.6 | 6/560 | 1.1 |

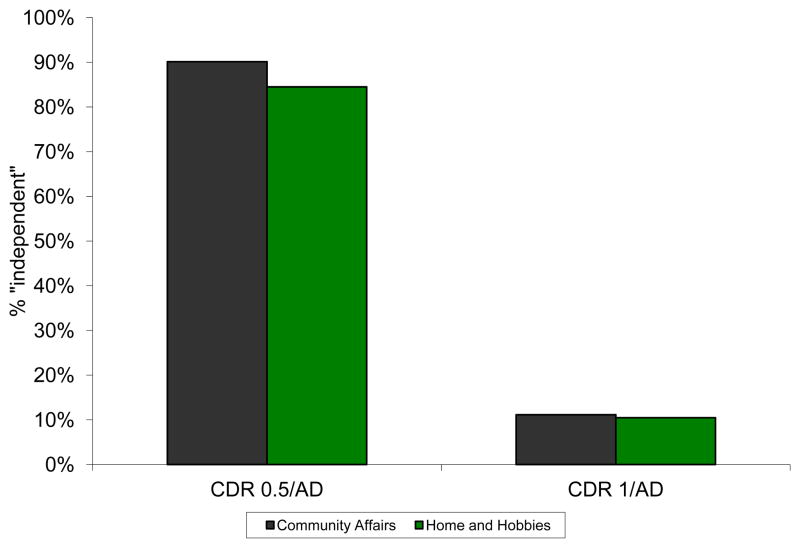

Box scores of 0, 0.5, or 1 in CA and in HH (i.e., normal, slight, and mild impairment) are allowable under the liberal operationalization of “functional independence” described by the revised criteria for MCI. The data in Table 3 indicate that 99.8% of all individuals currently diagnosed as CDR 0.5/AD and 92.7% of all individuals currently diagnosed as CDR 1/AD could be reclassified as MCI with the revised criteria, as these individuals have box scores of 0, 0.5, or 1 for CA and HH (Figure 1). Limiting the operationalization of “functional independence” to box scores of 0 and 0.5 still results in 90.1% (for CA) and 84.5% (for HH) of currently diagnosed CDR 0.5/AD individuals potentially meeting revised criteria for MCI, although the percent of currently diagnosed CDR 1/AD that could be reclassified as MCI is notably reduced (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Percent of AD dementia participants in NACC who would be considered “independent” in functional activities by revised MCI criteria where “independent” includes CDR box scores of 0, 0.5, and 1. These individuals could thus be reclassified as MCI.

Figure 2.

Percent of AD dementia participants in NACC who would be considered “independent in functional activities” by revised MCI criteria where “independent” includes CDR box scores of 0 and 0.5. These individuals could thus be reclassified as MCI.

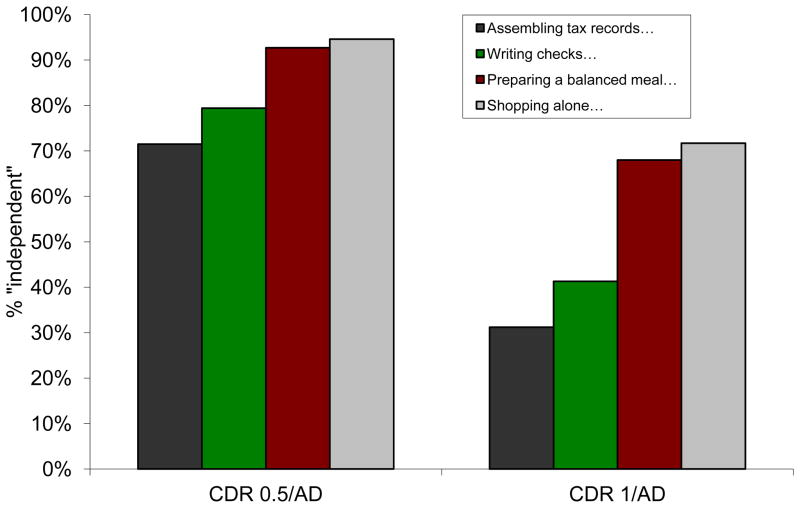

Data from FAQ items (Table 3) are consistent with the findings from the CA and HH box scores. Because “mild problems” in performing finances, cooking, and shopping or the need for assistance to perform these activities are allowed by the revised criteria for MCI, scores for the 4 corresponding FAQ items (assembling tax records, writing checks, preparing meals, shopping) of 0 (normal), 1 (does by self with difficulty), and 2 (does with assistance) are found for between 71.5% (assembling tax records) and 94.6% (shopping) of currently diagnosed CDR 0.5/AD individuals and for between 31.2% (assembling tax records) to 71.7% (shopping) of currently diagnosed CDR 1/AD individuals (Figure 3). These individuals thus could meet the revised criteria for MCI. Limiting FAQ scores to 0 and 1 shows that between 43.4% (assembling tax records) and 80.4% (shopping) of currently diagnosed CDR 0.5/AD individuals and between 11.1% (assembling tax records) and 38.7% (preparing meals) of currently diagnosed CDR 1/AD individuals could be reclassified as MCI (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Percent of AD dementia participants in NACC who would be considered “independent in functional activities” by revised MCI criteria where “independent” includes “does with assistance” (FAQ = 0, 1, 2). These individuals could thus be reclassified as MCI.

Figure 4.

Percent of AD dementia participants in NACC who would be considered “independent in functional activities” by revised MCI criteria where “independent” includes “does by self with difficulty” (FAQ = 0, 1). These individuals could thus be reclassified as MCI.

DISCUSSION

The differentiation between MCI and AD dementia in its earliest symptomatic stages has been based primarily on whether the cognitive impairment interferes with the conduct of activities of daily living. Clinicians for ADC participants currently submitted to NACC appear to follow this distinction, as two-thirds or more of individuals diagnosed with MCI are rated with no impairment in performance of activities in the community and at home, whereas over 75% of CDR 0.5/AD individuals have at least slight impairment in these activities. However, revised criteria for MCI2 now obscure this distinction by permitting mild difficulties in functional activities to be part of the MCI spectrum. As a result, the large majority of individuals currently diagnosed with milder stages of AD dementia now could be reclassified as MCI with the revised criteria. The elimination of the functional boundary between MCI and AD dementia means that their distinction will be based solely on the individual judgment of clinicians, resulting in nonstandard and ultimately arbitrary diagnostic approaches to MCI. This recalibration of MCI moves its focus away from the earliest stages of cognitive decline, confounds clinical trials of individuals with MCI where progression to AD dementia is an outcome, and complicates diagnostic decisions and research comparisons with legacy data.

The diagnostic overlap of MCI and AD dementia suggests ambiguity in the MCI concept,20,21 as also may be reflected by the continuing evolution of its criteria. The original criteria specified impairment in memory only with the preservation of other cognitive abilities and intact functional performance,6,7 distinguishing it from AD dementia where deficits in multiple cognitive domains and interference with functional activities are required. A multicenter clinical trial of donepezil and vitamin E in 769 individuals classified as MCI using the original criteria found, however, that very mild impairments often were present in cognitive domains other than memory.11 Criteria for MCI subsequently were modified to allow both impairment in cognitive domains other than memory and impairments in multiple domains, thus erasing one of the original distinguishing features of MCI and leaving only the “essentially normal” performance of functional activities in MCI as the difference between MCI and the milder stages of AD dementia.8,9

Standardizing the degree of functional impairment that is associated with dementia rather than MCI has been problematic,8 in part because the determination of impairment is dependent on how carefully performance of usual activities is interrogated by the clinician. It nonetheless has become apparent that many individuals characterized as MCI are functionally impaired.22,23 Ninety-six individuals with MCI in one study showed a wide range of impairment in everyday function as compared with 105 cognitively normal older adults,24 and another study of 285 individuals with MCI found that 34.3% were restricted in their ability to perform at least 2 of 4 activities (using a telephone; handle transportation; responsibility for medications; handle finances), compared with only 5.4% of cognitively older healthy persons.25 Even using criteria for MCI that require “essentially normal” activities for daily living, as is specified for the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative that examines the progression of MCI to very mild AD dementia, 104 (37%) of 283 MCI individuals were rated as functionally impaired with 0.5 ratings for both CA and HH on the CDR or a rating of 1 for either box.26

It is not surprising that their criteria essentially are indistinguishable if MCI and AD dementia are produced by the same underlying disease process. In many (but not all) instances the underlying process for MCI is AD, a brain disorder that is characterized by continuous deterioration of synaptic and neuronal integrity.27–29 The concept of an AD continuum has been noted from many perspectives, including epidemiological,30 neuropsychological,31,32 structural and metabolic imaging,33 and pathophysiological.34 The initial stages of the continuum, representing a preclinical stage of AD,4 are marked by no or only minimal synaptic and neuronal deterioration35–37 and correspondingly symptoms are absent (at least as detected by currently available methods). As the disease process progresses over time and neurodegeneration increases, the symptomatic stage of AD gradually develops.38 The symptomatic stage may be subdivided by the degree of cognitive and functional impairment, ranging from minimal to severe. (Table 4)

Table 4.

A Nonconformist’s View of Alzheimer Disease

|

|

|

For virtually all persons with AD, MCI represents the earliest clinically detectable stage of symptomatic AD. Imparting binary distinctions on the cognitive continuum of AD by designating one side as “MCI” and the other as “dementia” inherently is difficult and has been made more challenging because experts cannot agree on the operationalization of MCI.39 It has proven equally difficult to provide operational criteria that distinguish MCI from normal cognitive aging. Although the increased variability of cognitive performance with age40 complicates this distinction, another factor is the reliance on cognitive performance measured at a single point in time to determine “impairment”. This approach, based on present level of performance, cannot capture the salient cognitive feature of AD, which is decline from that individual’s previously attained abilities. Intraindividual decline (i.e., the temporal loss of cognitive abilities) must be obtained with serial cognitive measurements or by a history of change from previously attained levels as reported by an observant informant.41 (Self-reported memory complaints rarely predict either impairment42,43 or future dementia,44–46 although some investigators find that subjective memory complaints in highly educated older adults may do so.47 )

The operational cutpoint for MCI frequently has been a neuropsychological test score in a relevant domain, most often memory, that is 1.5 or more SDs below age-corrected means,48–51 but occasionally a score that is only 1 SD or more below normative values is used,52 as are other algorithms.53,54 Differing cutpoints produce different classifications of MCI and contribute to variable outcomes.55 Furthermore, the effects of preclinical AD artificially lower cognitive performances in putatively “normal” samples and produce cutoffs that are too lenient to identify initial change from truly healthy cognitive aging, thus resulting in an ascertainment bias where “impairment” is detected only after notable cognitive decline has occurred.56,57 Variable cutoff scores used to characterize MCI, ascertainment bias caused by preclinical AD, and problems of misclassification when using a measurement at a single time point to identify a process of intraindividual decline all introduce heterogeneity to MCI.49,58–62 Just as there are non-AD causes of dementia, there are non-AD causes of MCI. 63 The use of informant report to capture the intraindividual cognitive and functional decline that is the hallmark of symptomatic AD both minimizes this heterogeneity and enables the accurate identification of the subset of MCI that is caused by AD.23,64–67 The clinical diagnosis of symptomatic AD with this method, even in individuals who meet MCI criteria, is supported by autopsy confirmation of AD neuropathology at rates (92%) comparable to those found for AD dementia.68

The revised criteria for MCI laudably recommend an etiologic diagnosis, “MCI due to AD”, when the clinical judgment is that AD is responsible for the cognitive dysfunction. The Workgroup also suggests that diagnostic confidence for AD could be enhanced by utilizing biomarkers for amyloid-beta deposition and neuronal injury.2 Some clinicians, however, are reluctant to diagnose symptomatic AD in this situation, presumably because of uncertainty as to whether “MCI due to AD” will progress to AD dementia and because the diagnosis of AD is perceived as stigmatizing. As noted above, an informant-based diagnostic method to capture intraindividual decline accurately identifies individuals in the MCI stage who have underlying AD and who longitudinally progress in dementia severity.67 Clinicians using other diagnostic approaches may increasingly use AD biomarkers to improve diagnostic certainty. An early etiologic diagnosis is advocated for other devastating neurodegenerative diseases such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis69,70 without resorting to terms such as “minimal motor impairment” and thus allow patients and families to initiate planning to cope with the illness and enable therapeutic interventions early in the disease course. An analogous approach should be implemented for AD.

Some studies report that between 30%–60% of physicians do not disclose the diagnosis of dementia, much less “MCI due to AD”, to their patients,71–73 although over 94% of the same physicians disclosed a diagnosis of terminal cancer.71 Factors cited against disclosing a dementia diagnosis included concern about provoking psychological distress in patients and families.74,75 Although individuals given a diagnosis of dementia can experience catastrophic reactions, including suicide,76 the actual risk of suicide is very small and in one study of community living individuals with dementia was estimated to be less than 0.1%.77 Patients and families have consistently indicated that receiving a diagnosis of dementia is very important to them to indicate that the cognitive symptoms have an identifiable cause and to plan for the future.78,79 A study of individuals who qualify for a MCI classification showed that depressive symptoms and measures of stress after disclosure of the diagnosis of AD dementia did not worsen from pre-diagnosis levels and indeed often improved for both the affected individuals and their family members.80

The pathobiologically-based “next step” now is to transition from the syndromic label of “MCI” to its etiologic diagnosis when the responsible disorder is believed to be AD.81 This “next step” circumvents the difficulty in attempting to dichotomize MCI and AD dementia and more appropriately reflects the continuum of AD. However, “MCI” still could be used to characterize individuals who may be in the early symptomatic stages of a non-AD dementing disorder, where there is less experience in accurately determining etiology than exists for “MCI due to AD”, or when potentially reversible disorders such as cognitive dysfunction associated with medications are suspected. Similar recommendations have been proposed by the International Working Group for New Research Criteria for the Diagnosis of AD. This Working Group proposes that “MCI” be reclassified as “prodromal AD” when this diagnosis is supported by clinical phenotype and biomarker profile,82 and suggests that the use of “MCI” be limited to individuals without a diagnosable illness.

The revised criteria2 accept that MCI can be associated with impaired functional activities, such that the distinction of MCI from dementia now simply is a matter of an individual clinician’s threshold for what represents one condition versus the other. The diagnostic overlap for MCI with milder cases of AD dementia is considerable and suggests that any distinction is artificial and arbitrary. Already, many individuals with MCI are treated with pharmacological agents approved for symptomatic AD, indicating that clinicians often do not distinguish the two conditions when faced with issues of medical management.83,84 It now is time to advance AD patient care and research by accepting that “MCI due to AD” is more appropriately recognized as the earliest symptomatic stage of AD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Discussions with colleagues from the Knight Alzheimer Disease Research Center at Washington University in St. Louis, MO, have been critical to the development of the ideas expressed here, as has support by National Institute on Aging grants P50 AG05681, P01 AG03991, and P01 AG026276. Leslie E. Phillips, PhD, and Sarah E. Monsell, MS, from the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center, Seattle, WA (U01 AG16976) kindly provided the clinical data. Catherine M. Roe, PhD, of Washington University conducted the analyses.

Reference List

- 1.Alzheimer’s Disease Education and Referral (ADEAR) Center. Connections Newsletter 12[3–4] Silver Spring, MD, National Institute on Aging; 2005. ADCs contribute significant AD research advances; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, Dubois B, Feldman HH, Fox NC, Gamst A, Holtzman DM, Jagust WJ, Petersen RC, Snyder PJ, Carrillo MC, Thies W, Phelps CH. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2011;7:270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, Hynes M, Jack CR, Kawas CH, Klunk WE, Koroshetz W, Manly JJ, Mayeux R, Mohs RC, Morris JC, Rossor MN, Scheltens P, Carillo MC, Thies W, Weintraub S, Phelps CH. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer’s Association workgroup. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2011;7:263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sperling RA, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, Bennett DA, Craft S, Fagan AM, Iwatsubo T, Jack CR, Jr, Kaye J, Montine TJ, Park DC, Reiman EM, Rowe CC, Siemers E, Stern Y, Yaffe K, Carrillo MC, Thies W, Morrison-Bogorad M, Wagster MV, Phelps CH. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2011;7:280–292. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. Washington, D.C: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petersen RC, Smith GE, Ivnik RJ, Tangalos EG, Schaid DJ, Thobodeau SN, Kokmen E, Waring SC, Kurland LT. Apolipoprotein E status as a predictor of the development of Alzheimer’s disease in memory-impaired individuals. JAMA. 1995;273:1274–1278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Petersen RC, Smith GE, Waring SC, Ivnik RJ, Tangalos EG, Kokmen E. Mild cognitive impairment: clinical characterization and outcome. Arch Neurol. 1999;56:303–308. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.3.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Petersen RC. Mild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entity. J Intern Med. 2004;256:183–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Winblad B, Palmer K, Kivipelto M, Jelic V, Fratiglioni L, Wahlund L-O, Nordberg A, Backman L, Albert M, Almkvist O, Arai H, Basun H, Blennow K, DeLeon M, DeCarli C, Erkinjuntti T, Giacobini E, Graff C, Hardy J, Jack C, Jorm A, Ritchie K, van Duijn C, Visser P, Petersen RC. Mild cognitive impairment-beyond controversies, towards a consensus: Report of the International Working Group on mild cognitive impairment. J Intern Med. 2004;256:240–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flicker C, Ferris SH, Reisberg B. Mild cognitive impairment in the elderly: Predictors of dementia. Neurology. 1991;41:1006–1009. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.7.1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grundman M, Petersen RC, Ferris SH, Thomas RG, Aisen PS, Bennett DA, Foster NL, Jack CR, Galasko DR, Doody R, Kaye J, Sano M, Mohs R, Gauthier S, Kim HT, Jin S, Schultz AN, Schafer K, Mulnard R, van Dyck CH, Mintzer J, Zamrini EY, Cahn-Weiner D, Thal LJ for the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study. Mild cognitive impairment can be distinguished from Alzheimer disease and normal aging for clinical trials. Arch Neurol. 2004;61:59–66. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nordlund A, Rolstad S, Hellstrom P, Sjogren M, Hansen S, Wallin A. The Goteborg MCI study: mild cognitive impairment is a heterogeneous condition. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr. 2005;76:1485–1490. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.050385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pfeffer RI, Kurosaki TT, Harrah CH, Chance JM, Filos S. Measurement of functional activities of older adults in the community. J Gerontol. 1982;37:323–329. doi: 10.1093/geronj/37.3.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): Current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43:2412–2414. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.11.2412-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: Report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morris JC, Weintraub S, Chui HC, Cummings J, DeCarli C, Ferris S, Foster NL, Galasko D, Graff-Radford NR, Peskind ER, Beekly D, Ramos EM, Kukull WA. The Uniform Data Set (UDS): Clinical and cognitive variables and descriptive data from Alzheimer Disease Centers. Alz Dis Assoc Disord. 2006;20:210–216. doi: 10.1097/01.wad.0000213865.09806.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weintraub S, Salmon D, Mercaldo N, Ferris S, Graff-Radford NR, Chui H, Dietrich W, Beekly D, Kukull W, Morris JC. The Alzheimer’s Disease Centers’ Uniform Data Set (UDS): The Neuropsychological Test Battery. Alz Dis Assoc Disord. 2009;23:91–101. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318191c7dd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morris JC, Ernesto C, Schaefer K, Coats M, Leon S, Sano M, Thal L, Woodbury P the ADCS. Clinical dementia rating (CDR) training and reliability protocol: The Alzheimer Disease Cooperative Study experience. Neurology. 1997;48:1508–1510. doi: 10.1212/wnl.48.6.1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rockwood K, Strang D, MacKnight C, Downer R, Morris JC. Interrater reliability of the clinical dementia rating in a multicenter trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:558–559. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb05004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Whitehouse PJ. Mild cognitive impairment - a confused concept? Nature Clinical Practice Neurology. 2007;3:62–63. doi: 10.1038/ncpneuro0403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schneider LS. Mild Cognitive Impairment (Editorial) Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13:629–632. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.8.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Griffith HR, Belue K, Sicola A, Krzywanski S, Zamrini E, Harrell L, Marson DC. Impaired financial abilities in mild cognitive impairment. Neurology. 2003;60:449–457. doi: 10.1212/wnl.60.3.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morris JC, Storandt M, Miller JP, McKeel DW, Jr, Price JL, Rubin EH, Berg L. Mild cognitive impairment represents early-stage Alzheimer’s disease. Arch Neurol. 2001;58:397–405. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.3.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Farias ST, Mungas D, Reed BR, Harvey D, Cahn-Weiner D, DeCarli C. MCI is associated with deficits in everyday functioning. Alz Dis Assoc Disord. 2006;20:217–223. doi: 10.1097/01.wad.0000213849.51495.d9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peres K, Chrysostome V, Fabrigoule C, Orgogozo JM, Dartigues J-F, Barberger-Gateau P. Restriction in complex activities of daily living in MCI; Impact on outcome. Neurology. 2006;67:461–466. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000228228.70065.f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chang YL, Bondi MW, McEvoy LK, Fennema-Notestine C, Salmon DP, Galasko D, Hagler DJ, Dale AM for the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Global clinical dementia rating of 0. 5 in MCI masks variability related to level of function. Neurology. 2011;76:652–659. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31820ce6a5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ingelsson M, Fukumoto H, Newell KL, Growdon JH, Hedley-Whyte ET, Frosch MP, Albert MS, Hyman BT, Irizarry MC. Early Aβ accumulation and progressive synaptic loss, gliosis, and tangle formation in AD brain. Neurology. 2004;62:925–931. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000115115.98960.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Herrup K. Reimagining Alzheimer’s disease - An age-based hypothesis. J Neurosci. 2010;30:16755–16762. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4521-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hyman BT. Amyloid-dependent and amyloid-independent stages of Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2011;68:1062–1064. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brayne C, Calloway P. The case identification of dementia in the community: a comparison of methods. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1990;5:309–316. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kawas CH, Corrada MM, Brookmeyer R, Morrison A, Resnick SM, Zonderman AB, Arenberg D. Visual memory predicts Alzheimer’s disease more than a decade before diagnosis. Neurology. 2003;60:1089–1093. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000055813.36504.bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tierney MC, Moineddin R, McDowell I. Prediction of all-cause dementia using neuropsychological tests within 10 and 5 years of diagnosis in a community-based sample. J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2010;22:1231–1240. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-100516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chao LL, Mueller SG, Buckley ST, Peek K, Raptentsetseng S, Elman J, Yaffe K, Miller BL, Kramer JH, Madison C, Mungas D, Schuff N, Weiner MW. Evidence of neurodegeneration in brains of older adults who do not fulfill MCI criteria. Neurobiol Aging. 2010;31:368–377. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mesulam M, Shaw P, Mash D, Weintraub S. Cholinergic nucleus basalis tauopathy emerges early in the aging-MCI-AD continuum. Ann Neurol. 2004;55:815–828. doi: 10.1002/ana.20100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gomez-Isla T, Price JL, McKeel DW, Morris JC, Growdon JH, Hyman BT. Profound loss of layer II entorhinal cortex neurons occurs in very mild Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 1996;16:4491–4500. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-14-04491.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Price JL, Ko AI, Wade MJ, Tsou SK, McKeel DW, Jr, Morris JC. Neuron number in the entorhinal cortex and CA1 in preclinical Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2001;58:1395–1402. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.9.1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Price JL, McKeel DW, Buckles VD, Roe CM, Xiong C, Grundman M, Hansen LA, Petersen RC, Parisi JE, Dickson DW, Smith CD, Davis DG, Schmitt FA, Markesbery WR, Kaye J, Kurlan R, Hulette C, Kurland BF, Higdon R, Kukull W, Morris JC. Neuropathology of nondemented aging: presumptive evidence for preclinical Alzheimer disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2009;30:1026–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morris JC, Roe CM, Grant EA, Head D, Storandt M, Goate AM, Fagan AM, Holtzman DM, Mintun MA. Pittsburgh Compound B imaging and prediction of progression from cognitive normality to symptomatic Alzheimer’s disease. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:1469–1475. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Allegri RF, Glaser FB, Taragano FE, Buschke H. Mild cognitive impairment: believe it or not? International Review of Psychiatry. 2008;20:357–363. doi: 10.1080/09540260802095099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Launer LJ. Counting dementia: There is no one “best” way. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2011;7:10–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2010.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jorm AF. The informant questionnaire on cognitive decline in the elderly (IQCODE): a review. International Psychogeriatrics. 2004;16:275–293. doi: 10.1017/s1041610204000390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McGlone J, Gupta S, Humphrey D, Oppenheimer S, Mirsen T, Evans DR. Screening for early dementia using memory complaints from patients and relatives. Arch Neurol. 1990;47:1189–1193. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1990.00530110043015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Minett T, Dean JL, Firbank M, Philip DCR, O’Brien JT. Subjective memory complaints, white-matter lesions, depressive symptoms, and cognition in elderly patients. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13:665–671. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.8.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tierney MC, Szalai JP, Snow WG, Fisher RH. The prediction of Alzheimer disease; the role of patient and informant perceptions of cognitive deficits. Arch Neurol. 1996;53:423–427. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1996.00550050053023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Carr DB, Gray S, Baty J, Morris JC. The value of informant vs. individual’s complaints of memory impairment in early dementia. Neurology. 2000;55:1724–1726. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.11.1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Collie A, Maruff P, Shafiq-Antonacci R, Smith M, Hallup M, Schofield PR, Masters CL, Currie J. Memory decline in healthy older people; Implications for identifying mild cognitive impairment. Neurology. 2001;56:1533–1538. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.11.1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jonker C, Geerlings MI, Schmand B. Are memory complaints predictive for dementia? A review of clinical and population-based studies. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2000;15:983–991. doi: 10.1002/1099-1166(200011)15:11<983::aid-gps238>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tschanz JT, Welsh-Bohmer KA, Lyketsos CG, Corcoran C, Green RC, Hayden KM, Norton MC, Zandi PP, Toone L, West NA, Breitner JCS Cache County Study Group. Conversion to dementia from mild cognitive disorder The Cache County Study. Neurology. 2006;67:229–234. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000224748.48011.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Manly JJ, Tang MX, Schupf N, Stern Y, Vonsattel J-PG, Mayeux R. Frequency and course of mild cognitive impairment in a multiethnic community. Ann Neurol. 2008;63:494–506. doi: 10.1002/ana.21326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kinsella GJ, Mullaly E, Rand E, Ong B, Burton C, Price S, Phillips M, Storey E. Early intervention for mild cognitive impairment: A randomised controlled trial. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009;80:730–736. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2008.148346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sano M, Raman R, Emond J, Thomas RG, Petersen R, Schneider LS, Aisen PS. Adding delayed recall to the Alzheimer Disease Assessment Scale is useful to studies of mild cognitive impairment but not Alzheimer disease. Alz Dis Assoc Disord. 2011;25:122–127. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181f883b7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dickerson BC, Sperling RA, Hyman BT, Albert MS, Blacker D. Clinical prediction of Alzheimer disease dementia across the spectrum of mild cognitive impairment. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:1443–1450. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.12.1443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Boyle PA, Wilson RS, Aggarwal NT, Tang Y, Bennett DA. Mild cognitive impairment Risk of Alzheimer disease and rate of cognitive decline. Neurology. 2006;67:441–445. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000228244.10416.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Petersen RC, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, Donohue MC, Gamst AC, Harvey DJ, Jack CR, Jagust WJ, Shaw LM, Toga AW, Trojanowski JQ, Weiner MW. Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI): Clinical characterization. Neurology. 2010;74:201–209. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181cb3e25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Matthews FE, Stephan BCM, McKeith I, Bond J, Brayne C and the Medical Research Council Cognitive Function and Ageing Study. Two-year progression from mild cognitive impairment to dementia: To what extent do different definitions agree? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:1424–1433. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sliwinski M, Lipton RB, Buschke H, Stewart W. The effects of preclinical dementia on estimates of normal cognitive functioning in aging. J Gerontol. 1996;51B:217–225. doi: 10.1093/geronb/51b.4.p217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Storandt M, Morris JC. Ascertainment bias in the clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Arch Neurol. 2010;67:1364–1369. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Busse A, Hensel A, Guhne U, Angermeyer MC, Riedel-Heller SG. Mild cognitive impairment: Long-term course of four clinical subtypes. Neurology. 2006;67:2176–2185. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000249117.23318.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ritchie K, Artero S, Touchon J. Classification criteria for mild cognitive impairment. A population-based validation study. Neurology. 2001;56:37–42. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Visser PJ, Kester A, Jolles J, Verhey F. Ten-year risk of dementia in subjects with mild cognitive impairment. Neurology. 2006;67:1201–1207. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000238517.59286.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Okello A, Koivunen J, Edison P, Archer HA, Turkheimer FE, Nagren K, Bullock R, Walker Z, Kennedy A, Fox NC, Rossor MN, Rinne JO, Brooks DJ. Conversion of amyloid positive and negative MCI to AD over 3 years: an 11C-PIB PET study. Neurology. 2009;73:754–760. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181b23564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Koivunen J, Scheinin NM, Virta JR, Aalto S, Vahlberg T, Nagren K, Helin S, Parkkola R, Viitanen M, Rinne JO. Amyloid PET imaging in patients with mild cognitive impairment; a 2-year follow-up study. Neurology. 2011;76:1085–1090. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318212015e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jicha GA, Petersen RC, Knopman DS, Boeve BF, Smith GE, Geda YE, Johnson KA, Cha R, DeLucia MW, Braak H, Dickson DW, Parisi JE. Argyrophilic grain disease in demented subjects presenting initially with amnestic mild cognitive impairment. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2006;65:602–609. doi: 10.1097/01.jnen.0000225312.11858.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Morris JC, Fulling K. Early Alzheimer’s disease. Diagnostic considerations. Arch Neurol. 1988;45:345–349. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1988.00520270127033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Morris JC, McKeel DW, Jr, Storandt M, Rubin EH, Price JL, Grant EA, Ball MJ, Berg L. Very mild Alzheimer’s disease: Informant-based clinical, psychometric, and pathological distinction from normal aging. Neurology. 1991;41:469–478. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.4.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Morris JC, Storandt M, McKeel DW, Rubin EH, Price JL, Grant EA, Berg L. Cerebral amyloid deposition and diffuse plaques in “normal” aging: Evidence for presymptomatic and very mild Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1996;46:707–719. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.3.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Storandt M, Grant EA, Miller JP, Morris JC. Longitudinal course and neuropathological outcomes in original versus revised MCI and in PreMCI. Neurology. 2006;67:467–473. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000228231.26111.6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Berg L, McKeel DW, Jr, Miller JP, Storandt M, Rubin EH, Morris JC, Baty J, Coats M, Norton J, Goate AM, Price JL, Gearing M, Mirra SS, Saunders AM. Clinicopathologic studies in cognitively healthy aging and Alzheimer disease: Relation of histologic markers to dementia severity, age, sex, and apolipoprotein E genotype. Arch Neurol. 1998;55:326–335. doi: 10.1001/archneur.55.3.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schrooten M, Smetcoren C, Robberecht W, Van Damme P. Benefit of the Awaji Diagnostic Algorithm for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A prospective study. Ann Neurol. 2011;70:79–83. doi: 10.1002/ana.22380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Andersen PM, Borasio GD, Dengler R, Hardiman O, Kollewe K, Leigh PN, Pradat P-F, Silani V, Tomik B. EFNS task force on management of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: guidelines for diagnosing and clinical care of patients and relatives. Eur J Neurol. 2005;12:921–938. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2005.01351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vassilas CA, Donaldson J. Telling the truth: what do general practitioners say to patients with dementia or terminal cancer? Br J Gen Pract. 1998;48:1343–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.De Lepeleire J, Buntinx F, Aertgeerts B. Disclosing the diagnosis of dementia: the performance of Flemish general practitioners. Int Psychogeriatr. 2004;16:421–428. doi: 10.1017/s1041610204000407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tarke ME, Segers K, Van Nechel C. What Belgian neurologists and neuropsychiatrists tell their patients with Alzheimer disease and why: A national survey. Alz Dis Assoc Disord. 2009;23:33–37. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e31817d5e4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.McIlvane JM, Popa MA, Robinson B, Houseweart K, Haley WE. Perceptions of illness, coping, and well-being in persons with mild cognitive impairment and their care partners. Alz Dis Assoc Disord. 2008;22:284–292. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318169d714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Draper B, Peisah C, Snowdon J, Brodaty H. Early dementia diagnosis and the risk of suicide and euthanasia. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2010;6:75–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2009.04.1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Erlangsen A, Zarit SH, Conwell Y. Hospital-diagnosed dementia and suicide: A longitudinal study using prospective, nationwide register data. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16:220–228. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181602a12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lim WS, Rubin EH, Coats M, Morris JC. Early stage Alzheimer disease represents increased suicidal risk in relation to later stages. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2005;19:214–219. doi: 10.1097/01.wad.0000189051.48688.ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Connell CM, Gallant MP. Spouse caregivers’ attitudes toward obtaining a diagnosis of a dementing illness. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:1003–1009. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb01881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lin KN, Liao YC, Wang PN, Liu HC. Family members favor disclosing the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Int Psychogeriatr. 2005;17:679–688. doi: 10.1017/S1041610205001675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Carpenter BD, Xiong C, Porensky EK, Lee MM, Brown PJ, Coats M, Johnson D, Morris JC. Reaction to a dementia diagnosis in individuals with Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:405–412. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Morris JC. Mild cognitive impairment is early-stage Alzheimer disease; time to revise diagnostic criteria (Editorial) Arch Neurol. 2006;63:15–16. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dubois B, Feldman HH, Jacova C, DeKosky S, Barberger-Gateau P, Cummings J, Delacourte A, Galasko D, Gauthier S, Jicha G, Meguro K, O’Brien J, Pasquier F, Robert P, Rossor M, Salloway S, Stern Y, Visser PJ, Scheltens P. Research criteria for the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: revising the NINCDS-ADRDA criteria. The Lancet Neurology. 2007;6:734–746. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70178-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.McClendon MJ, Hernandez S, Smyth KA, Lerner AJ. Memantine and actylcholinesterase inhibitor treatment in cases of CDR 0. 5 or questionable impairment. J Alz Dis. 2009;16:577–583. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-0994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Schneider LS, Dagerman KS, Higgins JPT, McShane R. Lack of evidence for the efficacy of memantine in mild Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2011;68:991–998. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.