Abstract

Polybrominated diphenyl ether(s) (PBDE) are ubiquitous environmental contaminants that bind and cross the placenta but their effects on pregnancy outcome are unclear. It is possible that environmental contaminants increase the risk of inflammation-mediated pregnancy complications such as preterm birth by promoting a proinflammatory environment at the maternal-fetal interface. We hypothesized that PBDE would reduce IL-10 production and enhance the production of proinflammatory cytokines associated with preterm labor/birth by placental explants. Second trimester placental explants were cultured in either vehicle (control) or 2 μM PBDE mixture of congers 47, 99 and 100 for 72 h. Cultures were then stimulated with 106 CFU/ml heat-killed Escherichia coli for a final 24 h incubation and conditioned medium was harvested for quantification of cytokines and PGE2. COX-2 content and viability of the treated tissues were then quantified by tissue ELISA and MTT reduction activity, respectively. PBDE pre-treatment reduced E. coli-stimulated IL-10 production and significantly increased E. coli-stimulated IL-1β secretion. PBDE exposure also increased basal and bacteria-stimulated COX-2 expression. Basal, but not bacteria-stimulated PGE2, was also enhanced by PBDE exposure. No effect of PBDE on viability of the explants cultures was detected. In summary, pre-exposure of placental explants to congers 47, 99, and 100 enhanced the placental proinflammatory response to infection. This may increase the risk of infection-mediated preterm birth by lowering the threshold for bacteria to stimulate a proinflammatory response(s).

Keywords: Placenta, PBDE, Environment, Inflammation

1. Introduction

Polybrominated diphenyl ether(s) (PBDE) have been used as additive flame retardants in a variety of consumer products including textiles, plastics, electronics components and polyurethane foam padding. Although these compounds may save lives by slowing the spread of fires, they can leach out of the products (in which they are not chemically bound) to become ubiquitous environmental pollutants. PBDE enter humans bodies through inhalation or ingestion of household dust or contaminated food where they accumulate in adipose tissues. Median half-life of these molecules in human adipose tissues is estimated to be 1–3 years for the more common congers (28, 49, 47, 99, 100, 153, 154, 183) [1] and PBDE levels in breast milk have been increasing in recent decades [2].

PBDE have previously been isolated from the human placenta [3], fetal membranes [4], amniotic fluid [4], and umbilical cord blood [5]. Concentrations of PBDE in the placenta correlate with environmental concentrations [6, 7]. Placentas from women who lived near an electronics waste recycling site, where concentrations of PBDE are elevated, had over 19-fold higher concentrations of PBDE than placentas from women at a reference site [6]. Perfusion studies suggest that PBDE may cross the the placental barrier and accumulate in the cotyledons [7] but their effects on placental function is largely obscure. During normal pregnancy, immunity at the maternal-fetal interface is tightly regulated to favor the survival of the fetal allograft [8]. This is done in part by inhibiting proinflammatory cytokines but promoting anti-inflammatory mediators [8]. Ascending bacterial infections can alter this cytokine balance to favor production of proinflammatory cytokines some of which stimulate the production of prostaglandins promoting cervical ripening and uterine contractions [8].

Two proinflammatory cytokines, IL-1β and TNF-α, and one anti-inflammatory cytokine, IL-10, appear to be of particular importance to the mechanism of infection mediated preterm birth. Mice that are knock-out for IL-1β and TNF-α are resistant to E. coli-mediated preterm birth [9]. Mice lacking IL-10 are more sensitive to LPS than wild-type animals [10] and pharmacological administration of IL-10 to mice can prevent LPS-induced preterm birth [11]. Human studies also suggest a pivotal role for these cytokines. Both IL-1β and TNF-α are increased in amniotic fluid samples collected from pregnancies that ended in preterm birth [12, 13]. Placentas from babies born preterm also produce less IL-10 than those from pregnancies that ended at term [14].

Recent studies have demonstrated that exposure to the environmental toxin 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) reduces the sensitivity of pregnant mice to LPS-induced preterm birth [15, 16] which is mediated through proinflammatory cytokines. Whether or not PBDE, which share similar chemical structures, affect cytokine mileu at the maternal-fetal interface is unclear. Therefore, we conducted a series of experiments to evaluate the effects of PBDE exposure on cytokine production by placental explants.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Materials

PBDE treatments consisted of a mix of BDE-47, BDE-99, and BDE-100 congers suspended in DMSO (Accustandard, New Haven, CT). These congers were selected because they are components of the DE-71 mixture that is used widely used to study the biological activities of PBDE [17, 18, 19]. The concentration of each of these congers was 2 mM. For the experimental studies, PBDE mix was diluted 1:1000 with culture media and added to the cells to a final concentration of 2 μM. At this concentration, PBDE-47 binds to the Aryl hydrocarbon receptor and has biological effects [20, 21]. Heat-killed bacteria were prepared as previously described [22]. E. coli strain J5 was purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA) and cultivated in nutrient broth, concentrated by centrifugation and resuspended in culture medium. Concentration of the bacteria was determined by setting up quantitative cultures and organisms were heat-killed by heating at 75 °C for 1 hour. Preparations were aliquoted and stored at −80 °C until use.

2.2. Placental explant cultures

All placental tissues used in the experiment were obtained with the prior approval from Institutional Review Boards. Placental tissues were obtained from elective terminations of pregnancy at 16–23 weeks gestational age. Tissues were rinsed with PBS and blood clots, membranes, and decidual lining were removed. Villus placenta was then isolated and fragments were chopped at 10 micron increments using a McIlwain tissue chopper for 3 passes (The Mickle Laboratory Engineering Co. LTD, Wood Dale, IL). Minced tissue was washed with 30 ml Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium DMEM (Irvine Scientific, Santa Ana, CA) and weighed. Chopped placenta (0.20 g) was placed in 60 mm culture dishes containing 3 ml of DMEM supplemented with 20% FBS (v/v) + 100 U/ml Penicillin + 100 μg/ml Streptomycin. Cultures were incubated overnight at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. Following 18 h of pre-incubation, 2 ml of the media were replaced and PBDE mixture was added to the appropriate dishes to the final concentration of 2 μM and incubated for another 72 h. Initial experiments with other environmental toxins suggested that exposure for 72 h at a minimum is required to detect biological effects on cytokines produced in this model system [23]. Heat-killed E. coli (106 CFU/ml final concentration) or an equivalent volume of sterile culture medium was added and the cultures incubated for a final 24 h. Conditioned medium was then collected and stored at −80 °C until assay. Tissues were either frozen at −80 °C for COX-2 quantification or used immediately for viability testing as described below.

2.3. Immunoassays

Concentrations of IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-10 in conditioned medium were analyzed by ELISA using reagents purchased from eBioscience lab, Inc (Hercules, CA). In addition, tissue content of COX-2 and PGE2 production was quantified. PGE2 was measured using Luminex™ EIA kits (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI) and analyzed on a BioPlex 200 bead array analyzer (Bio Rad, Hercules, CA). COX-2 expression was quantified in cell lysates using COX-2 ELISA kit (Enzo Life Sciences, Plymouth Meeting, PA).

2.4. Viability assays

Relative viability of the explant cultures was evaluated using 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) to quantify mitochondrial dehydrogenase activity. 0.1 g of minced placenta tissues was cultured in 2 ml DMEM media and tissues were exposed to PBDE as described above. After 4 days incubation, MTT (0.5 mg/ml in PBS) was added and tissues were incubated for 1 hr to allow for for crystal formation. Crystals were extracted from the tissues with 10 ml of iso-propanol and absorbance was measured at 562 nm.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using mixed linear effects models using the lmer package of R (www.r-project.org). Effects due to bacterial stimulation and PBDE treatment were considered fixed and effects due to placental donor were considered random. Models were checked for fit using likelihood ratio tests to determine if separate slopes and intercepts for each patient were required or if separate intercepts alone would suffice. Residuals of the fitted models were evaluated for normality and homogeneity. When violations of these assumptions were detected, data were log-transformed for hypothesis testing (estimating P-values). Potential differences between individual treatments were evaluated with pre-planned contrasts using the esticon function of the doBy package. Data are presented as fitted means ± SEM and contrasts ±95% confidence intervals. Differences where P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

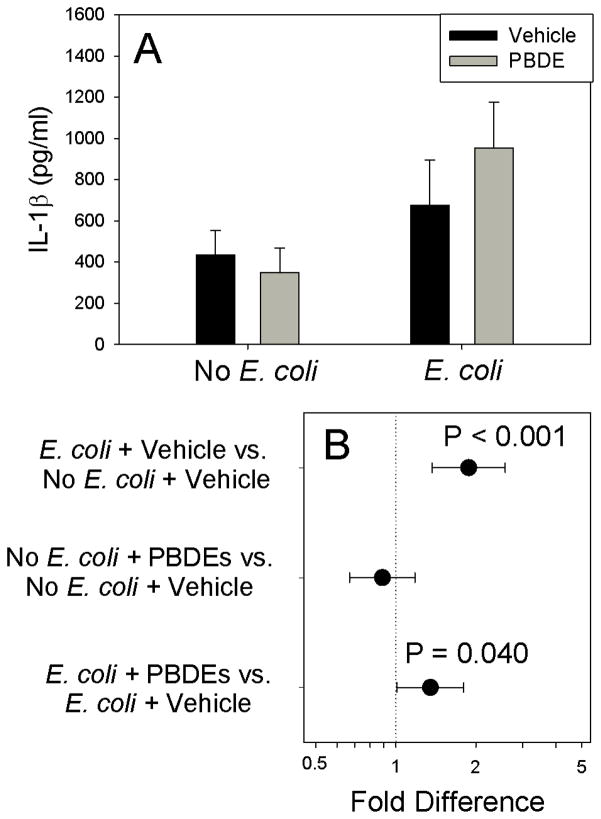

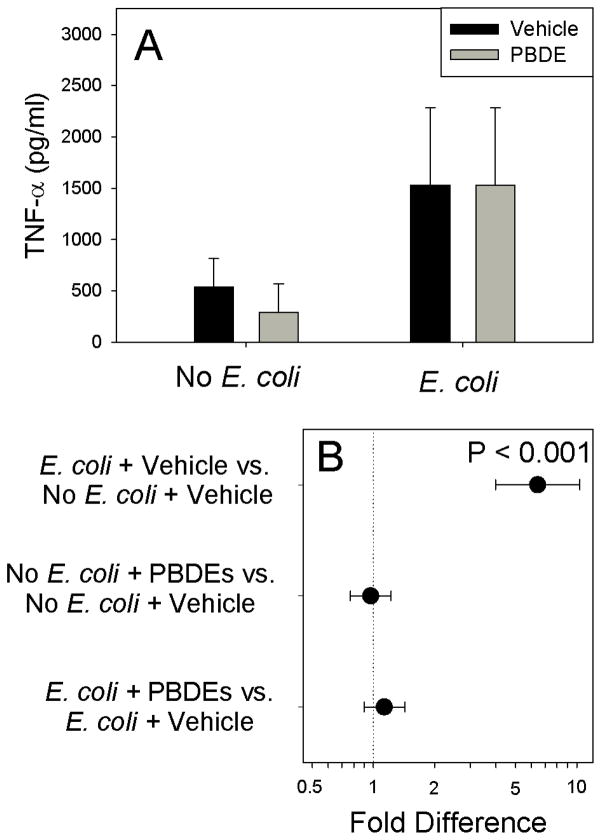

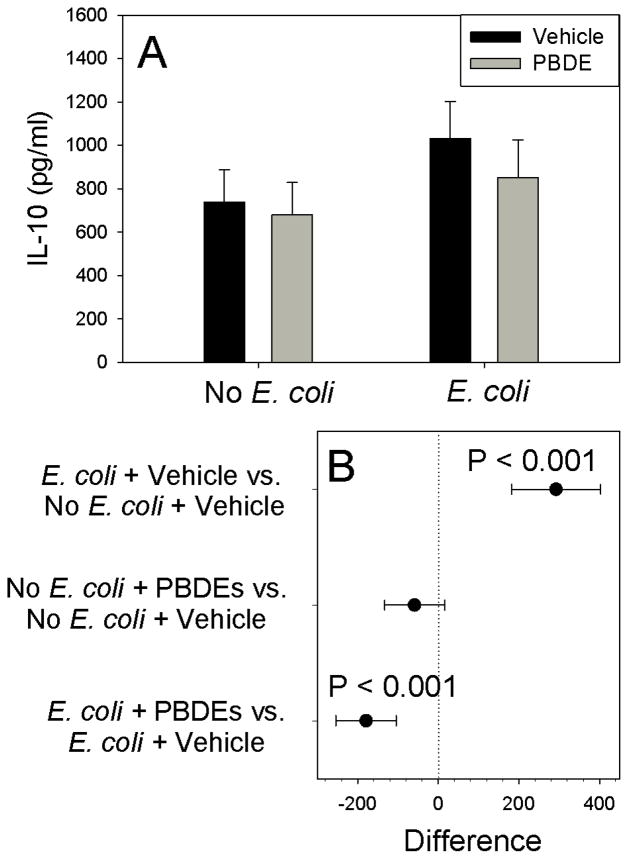

As expected, E. coli stimulated IL-1β production (P<0.001). Although PBDE treatment had no detectable effect on IL-1β production in the absence of infection (Figure 1, P=0.431), pre-exposure to PBDE augmented E. coli-stimulated IL-1β production (P=0.040). Although E. coli infection significantly stimulated TNF-α production (Figure 2, P<0.001), PBDE pre-treatment had no detectable effect on basal (P=0.808) or E. coli-stimulated (P=0.302) TNF-α production. IL-10 production was also increased by E. coli treatment, confirming the activity of the bacterial preparation (Figure 3; P<0.001), Although IL-10 was unaffected by PBDE pre-treatment for unstimulated placental explants (P=0.188), PBDE pretreatment significantly reduced (by ~180 pg/ml) for E. coli-stimulated cultures (Figure 3; P<0.001).

Figure 1.

Effect of Polybromated diphenyl ethers (PBDE) on basal and bacteria-stimulated IL-1β cytokine production by placental explant cultures from 10 different women. Shown are fitted means ± S.E.M. (Panel A) and preplanned comparisons (fold difference ± 95% confidence interval) between between individual treatments (Panel B). Contrasts where the 95% confidence intervals cross 1.0 (dotted vertical line) are not statistically significant.

Figure 2.

Effect of Polybromated diphenyl ethers (PBDE) on basal and bacteria-stimulated TNF-α production by placental explant cultures using tissues from 10 different women. Shown are fitted means ± S.E.M. (Panel A) and preplanned comparisons (fold difference ± 95% confidence interval) between between individual treatments (Panel B). Contrasts where the 95% confidence intervals cross 1.0 (dotted vertical line) are not statistically significant.

Figure 3.

Effect of Polybromated diphenyl ethers (PBDE) on basal and E. coli-stimulated IL-10 production by placental explant cultures from 10 different women. Shown are fitted means ± S.E.M. (Panel A) and preplanned comparisons (difference in cytokine production ± 95% confidence interval) between between individual treatments (Panel B). Contrasts where the 95% confidence intervals cross 0 (dotted vertical line) are not statistically significant.

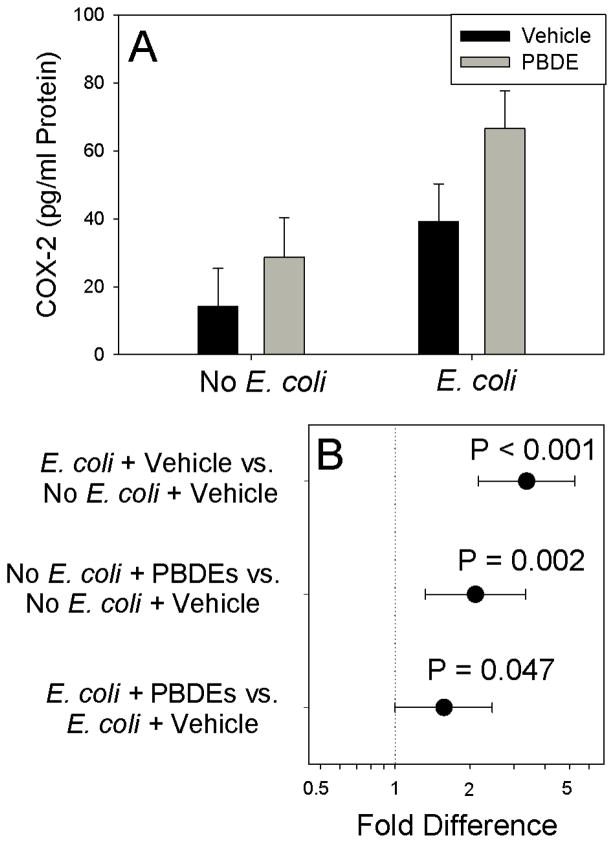

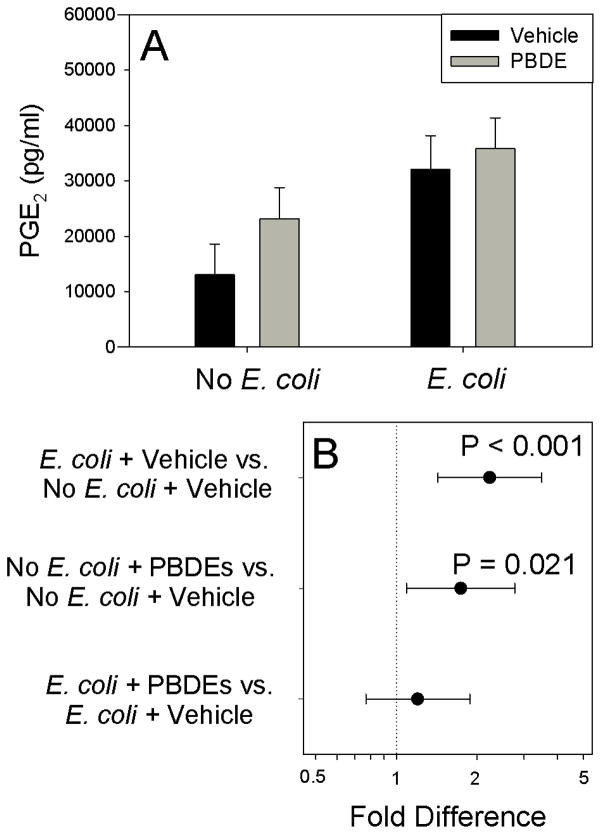

E. coli significantly increased COX-2 levels in the placental tissues (Figure 4; P<0.001). Exposure of the explants to PBDE mixture for 72 h significantly increased basal (P=0.002) and E. coli-stimulated COX-2 expression (P=0.047). As shown in Figure 5, PBDE significantly increased PGE2 secretion by unstimulated placental explants (P=0.021). Although, E. coli treatment increased PGE2 production (P<0.001), PBDE pretreatment did not augment E. coli-stimulated PGE2 production. No effects of PBDE were detected on MTT activity (Table 1).

Figure 4.

Effect of Polybromated diphenyl ethers (PBDE) on placental COX-2 content. Shown are fitted means ± S.E.M. (Panel A) and contrasts (fold-difference ± 95% confidence interval) between individual treatments (Panel B) for experiments using tissues from 9 different women. Contrasts where the 95% confidence intervals cross 0 (dotted vertical line) are not statistically significant.

Figure 5.

Effect of Polybromated diphenyl ethers (PBDE) on basal and bacteria stimulated PGE2 production for experiments performed on tissues harvested from 6 different women. Shown are fitted means ± S.E.M. (Panel A) and pre-planned contrasts (± 95% confidence interval) between individual treatments. Contrasts where the 95 % confidence interval crosses unity are not statistically significant

Table 1.

Effect of PBDE on viability of placental explant cultures. Shown are least-square means ± SEM for experiments performed on placental tissues from 5 different women.

| Treatment | A570–690 | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Control1 | 0.621±0.066 | Reference |

| Vehicle2 | 0.631±0.066 | 0.918 |

| 1 μM PBDE | 0.630±0.066 | 0.636 |

| 2 μM PBDE | .619±0.066 | 0.637 |

Culture medium (DMEM + 20% fetal bovine serum + 100 U/ml Penicillin + 100 ug/ml Streptomycin)

0.1% DMSO (v/v) in culture medium

4. Discussion

Our studies suggest that PBDE exposure may alter the production cytokines that have key roles in the pathophysiology of preterm birth. We found that PBDE enhanced bacteria-stimulated IL-1β production as well as inhibited bacteria-stimulated production of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10. Much of what is known about the mechanism of infection-mediated preterm birth centers on the reciprocal actions of these two cytokines. IL-1β activates the parturition mechanism by enhancing the production of COX-2, prostaglandins, and matrix metalloproteinases whereas IL-10 favors continuation of pregnancy by inhibiting IL-1β [8]. It is possible that PBDE exposure lowers the threshold for bacteria to induce preterm birth by promoting IL-1β production but inhibiting IL-10 production.

Many of the effects of IL-1β are mediated through COX-2 which makes the prostaglandins PGE2 and PGF2α that stimulate the uterine contractions associated with labor. In our study, PBDE exposure enhanced COX-2 and PGE2 production by unstimulated cultures. This may be independent of IL-1β, however, since no effect of PBDE on IL-1β production was observed in the absence of bacterial stimulation. Further studies are needed to determine if PBDE reduce the production of IL-1ra which could increase the biological activity of endogenous IL-1β levels. Alternatively PBDE may enhance the IL-1 receptor expression or its signal transduction pathways to enhance COX-2 and PGE2 production. Increased COX-2 and PGE2 expression in the placenta may also increase susceptibility of women to bacterial infections by stimulating premature cervical ripening-a common cause of preterm birth.

Despite the ubiquitous exposure of pregnant women to PBDE as evidenced by their detection in placenta [3], placental membranes [4], amniotic fluid [24] and breast milk[2], their effects on pregnancy have not been widely studied. Our results are consistent with a recent report by Miller who found no effect of PBDE congers −47, or −153 on basal IL-1β production by extraplacental fetal membranes [4]. Miller however, only used LPS as a positive control and did not evaluate the effects of PBDE on bacteria-stimulated cytokine production as we did in the present study [4]. Our results are consistent with other results from our lab where we used this same culture system to evaluate how TCDD may affect basal and bacteria-stimulated cytokine production by placental explants [23]. We found that TCDD increased basal and bacteria-stimulated PGE2 production [23]. Although no effect of TCDD on basal TNF-α, IL-1β or IL-10 production was detected, TCDD significantly enhanced E. coli-stimulated TNF-α production, inhibited E. coli-stimulated IL-10 production and had no effect on bacteria stimulated IL-1β production [23]. This differs slightly from our results where PBDE enhanced IL-1β production but had no effect on TNF-α production.

The mechanism by which PBDE may alter cytokine production is unclear. Due to the structural similarity with PCB-like molecules, interactions of PBDE with the Aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) and its signal transduction pathway have been studied [25, 20]. The most environmentally relevant PBDE (congers 47 and 99) that were used in our mixture, however, are only weak agonists to the AhR [25] but did antagonize TCDD signal transduction by competitive inhibition [20, 21].

Like PCBs, PBDE also have structural similarity to the thyroid hormones and may interact with the thyroid receptor [26]. Administration of PBDE commercial mix, DE-71, to pregnant rats resulted in a 44% reduction in maternal thyroxine levels at gestational day 20 [27]. Recent studies, have demonstrated that pregnant women with increased blood levels of PBDE (evaluated at 27 weeks gestation) are at significantly increased risk for subclinical hypothyroidism [28]. Another study found that pregnant women living near a recycling plant have increased blood levels of PBDE’s at 16 weeks gestation and lower plasma total T4 and TSH concentrations [29].

The placenta expresses thyroid receptors [30, 31, 32, 33, 34] and it is possible that disruption of thyroxine hormone signaling by PBDE could result in an enhanced inflammatory response by fewer numbers of microorganisms that can trigger preterm labor. Macrophages of hypothyroid rats have enhanced IL-1β expression in response to streptococcal wall protein than thyroid controls [35]. This enhanced inflammatory response in hypothyroid rats was ameliorated by thyroxine [35]. Women with subclinical hypothyroidism or anti-thyroglobulin auto-antibodies were at 2- to 3-fold increased risk for early preterm birth than normal women [36, 37]. Further studies are needed to determine if the results observed in the present study are mediated through disruption of the thyroid hormones and to clarify the role of infection and inflammation in preterm birth in women with subclinical hypothyroidism.

Our study has a number of strengths. First, we used second-trimester placentas which are presumably from normal pregnancies at 16–23 weeks gestation. This is during the time when the detrimental effects that ultimately result in preterm birth are likely to occur. Use of placental explants in lieu of primary trophoblast cultures eliminates the possibility that tissue processing could affect the results. It also enables us to study the total effect of many different cell types at the maternal-fetal interface on cytokine production while maintaining some of the 3-dimensional tissue architecture of the tissues. Application of all the treatments to placental cultures derived from tissues from the same patient allows us to control for patient-to-patient variability in the measured outcomes to the best extent possible. Any unmeasured interactions between treatments applied to the culture and a subgroup of patients (for example, if PBDE are more effective at enhancing inflammation in African-American women than Caucasians) would tend to bias results towards the null.

Our findings are not without limitations, however. We are using discarded tissues from women having a controversial obstetrical procedure. Therefore, we are unable to collect detailed information about the patients with regard to their demographics, medical history, reason for seeking termination, or use tobacco or alcohol out of respect for their privacy. Patients having elective abortions may be more likely to be younger, unmarried, use recreational drugs, smoke or consume alcohol than the general obstetrical population. Another limitation is that we are also unable to evaluate basal levels of PBDE in the tissues used for this experiment. Adipose tissue concentrations of PBDE in people in New York City, where the tissues were collected, were reported to be approximately 10–100 times higher than they are in Europe [38]. Our findings are also limited by the congers used for this study. We used a mixture of congers PBDE-47, PBDE-99, and PBDE-100 that are the major congers in breast milk in the northeastern United States [39] and comprise the DE-71 mixture that is widely used to study the biological effects of PBDE [17, 18, 19]. Other congers may have different effects on placental cytokine production. Although the concentrations of PBDE used in this study are typical of those used for other in vitro experiments [25, 20, 21], they are approximately 1000-fold greater than levels reported for human placental samples [3]. Tissue uptake of PBDE is likely to be inefficient since the placenta contains little fat and is a product of PBDE concentration and time of exposure. Therefore, high concentrations of PBDE are needed to compensate the limited time of exposure to them in our cell culture system. This may explain, in part, why previous studies did not find any effects of PBDE exposure on placental function [4].

In summary, pre-exposure to PBDE shifted placental cytokine production to a more proinflammatory phenotype. This may increase the risk of preterm birth by lowering the threshold for bacteria to induce a detrimental inflammatory response. Further studies with animal models are necessary to determine if the effects observed in our culture system are present in vivo and if PBDE exposure can alter pregnancy outcome.

Acknowledgments

This project was is supported in part by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (5R21ES017320-02). The authors wish to thank Mr. Adam Rhodes and Mr. Hschi-Chi Koo for skilled laboratory assistance during the performance of this project.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Trudel D, Scheringer M, von Goetz N, Hungerbuhler K. Total consumer exposure to polybrominated diphenyl ethers in North America and Europe. Environ Sci Technol. 2011;45:2391–2397. doi: 10.1021/es1035046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Solomon GM, Weiss PM. Chemical contaminants in breast milk: time trends and regional variability. Environ Health Perspect. 2002;110:A339–A347. doi: 10.1289/ehp.021100339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frederiksen M, Thomsen M, Vorkamp K, Knudsen LE. Patterns and concentration levels of polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) in placental tissue of women in Denmark. Chemosphere. 2009;76:1464–1469. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2009.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller MF, Chernyak SM, Batterman S, Loch-Caruso R. Polybrominated diphenyl ethers in human gestational membranes from women in southeast Michigan. Environ Sci Technol. 2009;43:3042–3046. doi: 10.1021/es8032764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frederiksen M, Thomsen C, Froshaug M, Vorkamp K, Thomsen M, Becher G, et al. Polybrominated diphenyl ethers in paired samples of maternal and umbilical cord blood plasma and associations with house dust in a Danish cohort. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2010;213:233–242. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2010.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leung AOW, Chan JKY, Xing GH, Xu Y, Wu SC, Wong CKC, et al. Body burdens of polybrominated diphenyl ethers in childbearing-aged women at an intensive electronic-waste recycling site in China. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2010;17:1300–1313. doi: 10.1007/s11356-010-0310-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frederiksen M, Vorkamp K, Mathiesen L, Mose T, Knudsen LE. Placental transfer of the polybrominated diphenyl ethers BDE-47, BDE-99 and BDE-209 in a human placenta perfusion system: an experimental study. Environ Health. 2010;9:32. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-9-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peltier MR. Immunology of term and preterm labor. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2003;1:122. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-1-122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirsch E, Filipovich Y, Mahendroo M. Signaling via the type I IL-1 and TNF receptors is necessary for bacterially induced preterm labor in a murine model. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:1334–1340. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murphy SP, Fast LD, Hanna NN, Sharma S. Uterine NK cells mediate inflammation-induced fetal demise in IL-10-null mice. J Immunol. 2005;175:4084–4090. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.6.4084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robertson SA, Skinner RJ, Care AS. Essential role for IL-10 in resistance to lipopolysaccharide-induced preterm labor in mice. J Immunol. 2006;177:4888–4896. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.7.4888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cox SM, Casey ML, MacDonald PC. Accumulation of interleukin-1beta and interleukin-6 in amniotic fluid: a sequela of labour at term and preterm. Hum Reprod Update. 1997;3:517–527. doi: 10.1093/humupd/3.5.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoon BH, Romero R, Park JS, Chang JW, Kim YA, Kim JC, et al. Microbial invasion of the amniotic cavity with Ureaplasma urealyticum is associated with a robust host response in fetal, amniotic, and maternal compartments. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:1254–1260. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)70142-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanna N, Bonifacio L, Reddy P, Hanna I, Weinberger B, Murphy S, et al. IFN-gamma-mediated inhibition of COX-2 expression in the placenta from term and preterm labor pregnancies. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2004;51:311–318. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2004.00162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Revich B, Aksel E, Ushakova T, Ivanova I, Zhuchenko N, Klyuev N, et al. Dioxin exposure and public health in Chapaevsk, Russia. Chemosphere. 2001;43:951–966. doi: 10.1016/s0045-6535(00)00456-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bruner-Tran KL, Osteen KG. Developmental exposure to TCDD reduces fertility and negatively affects pregnancy outcomes across multiple generations. Reprod Toxicol. 2011;31:344–350. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fowles JR, Fairbrother A, Baecher-Steppan L, Kerkvliet NI. Immunologic and endocrine effects of the flame-retardant pentabromodiphenyl ether (DE-71) in C57BL/6J mice. Toxicology. 1994;86:49–61. doi: 10.1016/0300-483x(94)90052-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stoker TE, Laws SC, Crofton KM, Hedge JM, Ferrell JM, Cooper RL. Assessment of DE-71, a commercial polybrominated diphenyl ether (PBDE) mixture, in the EDSP male and female pubertal protocols. Toxicol Sci. 2004;78:144–155. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfh029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dufault C, Poles G, Driscoll LL. Brief postnatal PBDE exposure alters learning and the cholinergic modulation of attention in rats. Toxicol Sci. 2005;88:172–180. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfi285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peters AK, van Londen K, Bergman A, Bohonowych J, Denison MS, van den Berg M, et al. Effects of polybrominated diphenyl ethers on basal and TCDD-induced ethoxyresorufin activity and cytochrome P450-1A1 expression in MCF-7, HepG2, and H4IIE cells. Toxicol Sci. 2004;82:488–496. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfh284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peters AK, Nijmeijer S, Gradin K, Backlund M, Bergman A, Poellinger L, et al. Interactions of polybrominated diphenyl ethers with the aryl hydrocarbon receptor pathway. Toxicol Sci. 2006;92:133–142. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfj186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nath CA, Ananth CV, Smulian JC, Peltier MR. Can sulfasalazine prevent infection-mediated pre-term birth in a murine model? Am J Reprod Immunol. 2010;63:144–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2009.00773.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hanna N, Arita Y, Klimova N, Koo HC, Gurzenda E, Peltier M. TCDD inhibit IL-10 production and enhance the proinflammatory response to bacteria by placental explants. Am J Reprod Immunol. doi: 10.1111/aji.12017. Submitted. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller MF. PhD Thesis. University of Michigan; 2009. The human gestational membranes as a site of polybrominated diphenly ether toxicity. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen G, Bunce NJ. Polybrominated diphenyl ethers as Ah receptor agonists and antagonists. Toxicol Sci. 2003;76:310–320. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfg236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luthe G, Jacobus JA, Robertson LW. Receptor interactions by polybrominated diphenyl ethers versus polychlorinated biphenyls: a theoretical Structure-activity assessment. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2008;25:202–210. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2007.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou T, Taylor MM, DeVito MJ, Crofton KM. Developmental exposure to brominated diphenyl ethers results in thyroid hormone disruption. Toxicol Sci. 2002;66:105–116. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/66.1.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chevrier J, Harley KG, Bradman A, Gharbi M, Sjodin A, Eskenazi B. Polybrominated diphenyl ether (PBDE) flame retardants and thyroid hormone during pregnancy. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118:1444–1449. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1001905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang J, Jiang Y, Zhou J, Wu B, Liang Y, Peng Z, et al. Elevated body burdens of PBDEs, dioxins, and PCBs on thyroid hormone homeostasis at an electronic waste recycling site in China. Environ Sci Technol. 2010;44:3956–3962. doi: 10.1021/es902883a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chan S, Murray PG, Franklyn JA, McCabe CJ, Kilby MD. The use of laser capture microdissection (LCM) and quantitative polymerase chain reaction to define thyroid hormone receptor expression in human ‘term’ placenta. Placenta. 2004;25:758–762. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2004.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leonard AJ, Evans IM, Pickard MR, Bandopadhyay R, Sinha AK, Ekins RP. Thyroid hormone receptor expression in rat placenta. Placenta. 2001;22:353–359. doi: 10.1053/plac.2000.0617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shahrara S, Drvota V, Sylven C. Organ specific expression of thyroid hormone receptor mRNA and protein in different human tissues. Biol Pharm Bull. 1999;22:1027–1033. doi: 10.1248/bpb.22.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Banovac K, Ryan EA, O’Sullivan MJ. Triiodothyronine (T3) nuclear binding sites in human placenta and decidua. Placenta. 1986;7:543–549. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4004(86)80140-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alderson R, Pastan I, Cheng S. Characterization of the 3,3′,5-triiodo-L-thyronine-binding site on plasma membranes from human placenta. Endocrinology. 1985;116:2621–2630. doi: 10.1210/endo-116-6-2621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rittenhouse PA, Redei E. Thyroxine administration prevents streptococcal cell wall-induced inflammatory responses. Endocrinology. 1997;138:1434–1439. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.4.5045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stagnaro-Green A, Chen X, Bogden JD, Davies TF, Scholl TO. The thyroid and pregnancy: a novel risk factor for very preterm delivery. Thyroid. 2005;15:351–357. doi: 10.1089/thy.2005.15.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Casey BM, Dashe JS, Wells CE, McIntire DD, Byrd W, Leveno KJ, et al. Subclinical hypothyroidism and pregnancy outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:239–245. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000152345.99421.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Johnson-Restrepo B, Kannan K, Rapaport DP, Rodan BD. Polybrominated diphenyl ethers and polychlorinated biphenyls in human adipose tissue from New York. Environ Sci Technol. 2005;39:5177–5182. doi: 10.1021/es050399x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Johnson-Restrepo B, Addink R, Wong C, Arcaro K, Kannan K. Polybrominated diphenyl ethers and organochlorine pesticides in human breast milk from Massachusetts, USA. J Environ Monit. 2007;9:1205–1212. doi: 10.1039/b711409p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]