Abstract

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a growing problem in the pediatric population and recent advances in diagnostics and therapeutics have improved their management, particularly the use of esophago-gastroduodenoscopy (EGD). Most of the current knowledge is derived from studies in adults; however there are distinct features between infant onset and adult onset GERD. Children are not just little adults and attention must be given to the stages of growth and development and how these stages impact the disease management. Although there is a lack of a gold standard test to diagnose GERD in children, EGD with biopsy is essential to assess the type and severity of tissue damage. To date, the role of endoscopy in adults and children has been to assess the extent of esophagitis and detect metaplastic changes complicating GERD; however the current knowledge points another role for the EGD with biopsy that is to rule out other potential causes of esophagitis in patients with GERD symptoms such as eosinophilic esophagitis. This review highlights special considerations about the role of EGD in the management of children with GERD.

Keywords: Endoscopy, Gastroesophageal reflux, Esophagitis, Infants, Children

INTRODUCTION

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) has a global impact on health and impairs the health related quality of life of a substantial proportion of the population worldwide. GERD is also prevalent in infants and adolescents suggesting that the disease process can begin early in life[1]. The disease phenotype in the pediatric population has changed over the last decades. For example, some complications such as esophageal strictures have decreased in prevalence and other complications such as extra-esophageal manifestations have been increasing. This might be in part explained by the great impact of new pharmacological therapies for GERD, but the most troubling complications of reflux disease in adults-esophageal adenocarcinoma-continues to increase at an alarming rate in some countries[2]. Therefore, the natural history of the disease needs more clarification.

GERD is a growing problem in pediatric population[1]. A database study involving children with GERD in the United Kingdom between the years of 2000 and 2005 showed an incidence of GERD 0.84 per 1000 person-years[3]. The incidence decreased from 1-year age to 12-year age and further to that, it increased again reaching a maximum prevalence at age 16-17 (2.26 per 1000 person-years for girls and 1.75 per 1000 person-years for boys). Hiatus hernia, congenital esophageal abnormalities and neurologic impairment were risk factors. Although large prospective population-based studies are lacked, it has been suggested that many children who had GERD diagnosis continue to have symptoms in adolescence and as young adults[4].

The main difference between gastroesophageal reflux (GER) in the pediatric population and the adults is that spitting up, the most visible symptom of regurgitation in infants, occurs at least once per day in about 50% of the healthy 3- to 4-mo-old infants[5,6] and this leads up to 20% of caregivers in the United States seek medical help for this common behavior[5]. Regurgitation ameliorates spontaneously in most healthy infants by 12 mo to 18 mo of age[5-10]. When regurgitation occurs in an otherwise healthy infant with normal growth and development, this is the so called “physiologic GER” and lifestyle changes only are recommended to manage it[11] whereas GERD is defined when the reflux of gastric contents causes troublesome symptoms and/or complications[12].

Recently a consensus statement based on an extensive review of literature has been proposed by the North American and European Societies for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (NASPGHAN and ESPGHAN) to provide pediatricians for the evaluation and management of patients with physiologic GER and GERD[11]. Therefore, the management of children with GERD is the focus of this review, particularly addressing the role of endoscopy.

DIAGNOSIS OF GERD

The diagnosis of GERD is often made clinically based on the symptoms or signs that may be associated with GER. In contrast with the adults, who can describe heartburn and/or regurgitation as typical GERD symptoms[13], subjective symptom description lacks reliability in infants and children younger than 8 to 12 years of age and consequently many of GERD symptoms in infants and children are nonspecific[11].

The main role of the medical history and physical examination in the evaluation of a child with GER is to rule out other worrisome disorders that present with vomiting (red flags-bilious vomiting, gastrointestinal bleeding, hematemesis, hematochezia, consistently forceful vomiting, onset of vomiting after 6 mo of life, failure to thrive, diarrhea, constipation, fever, lethargy, hepatosplenomegaly, bulging fontanelle, macro/microcephaly, seizures, abdominal distension) and to identify complications of GERD[11].

Although many tests have been used to diagnose GERD, the lack of a gold standard has hampered the assessment of the accuracy of various approaches to the diagnosis of GERD[14]. In addition, it is not known if a test can predict an individual patient’s outcome. Nevertheless, tests are useful to detect pathologic reflux or its complications, to establish a causal relation between reflux and symptoms, to evaluate therapy, and to exclude other conditions. Because there is no test able to assess all those issues altogether, tests should be carefully selected according to the information sought, and the limitations of each test must be considered.

The tests more commonly available for the diagnosis of GERD in children are as follows[11]: (1) esophageal barium contrast radiography-not useful for the diagnosis of GERD but is useful to confirm or rule out anatomic abnormalities of the upper gastrointestinal tract, i.e., hiatal hernia; (2) esophageal pH monitoring-valid quantitative measure of esophageal acid exposure, useful to evaluate efficacy of anti- secretory therapy, but clinical utility of pH monitoring for diagnosis of extra-esophageal complications of GER are not well established; (3) esophageal combined multiple intraluminal impedance and pH monitoring-superior to pH monitoring alone for evaluation of the temporal relation between symptoms and GER, but clinical utility has yet to be determined; (4) esophageal manometry-may be useful to diagnose a motility disorder, i.e., achalasia or other esophageal motor abnormality that may mimic GERD; (5) esophago-gastroduodenoscopy (EGD) and biopsy-endoscopically visible breaks in the distal esophageal mucosa are the most reliable evidence of reflux esophagitis; endoscopic biopsy is important to identify or rule out other causes of esophagitis, and to diagnose and monitor Barrett esophagus (BE); (6) esophago-gastric ultrasonography and nuclear scintigraphy-not recommended for the routine evaluation of GERD in children; and (7) empiric trial of acid suppression as a diagnostic test-a trial of pre-endoscopy proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) up to 4 wk may be helpful in an older child or adolescent with typical symptoms suggesting GERD. Specific multiple questionnaires have been developed in both adults and children to improve the accuracy of diagnosing GER[15,16]; however, many have limitations therefore they are not indicated for routine use[17,18].

EGD AND BIOPSY IN GERD

EGD allows direct visual examination of the esophageal mucosa and mucosal biopsies enable evaluation of the microscopic anatomy[19]. Endoscopic findings in patients with GERD include esophagitis, erosions, exudates, ulcers, strictures, hiatus hernia, and areas of possible esophageal metaplasia. A continuously patent gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) seems to be helpful to predict esophagitis in biopsies[20].

Recent global consensus guidelines define reflux esophagitis as the presence of endoscopically visible breaks in the esophageal mucosa at or immediately above the GEJ[12,13,21]. The identification of esophagitis with EGD has specificity 90%-95% for GERD[22], but has a poor sensitivity of around 50%[23]. About 50% of adult patients with GERD symptoms (i.e., heartburn and/or regurgitation) showed normal endoscopy in referral centers[24], but studies from community practice demonstrated that 53% to 70% of the patients had non erosive reflux disease (NERD)[25-29]. Erosive esophagitis (EE) does not seem to be as common as previously suggested in adults[30]. In regard of the pediatric population, a recent multicenter survey in 7188 children aged 0-17 years that underwent EGD showed 12.4% prevalence of EE[31] whereas a previous single center had showed 34.6% prevalence in 402 children[32]. The criticism for the studies in children is that patients who had EGD were not patients with GERD symptoms only, therefore the prevalence of EE in pediatric patients might be underestimated.

Acid suppression before EGD may significantly limit the sensitivity of endoscopy as a diagnostic tool. A recent study has shown that PPI use contributes significantly to the classification of GERD patients into the NERD-phenotype. NERD adults on PPI therapy demonstrate some features that are significantly different from PPI-naïve patients, but similar to EE patients. This observation supports the notion that some PPI-NERD patients are actually healed EE patients, and that an overlap does exist between the GERD phenotypes[33].

Evidence from adult studies indicates that visible breaks in the esophageal mucosa are the endoscopic signs of greatest interobserver reliability[34,35]. Operator experience is an important component of interobserver reliability[36,37]. Mucosal erythema or an irregular Z-line is not a reliable sign of reflux esophagitis[34,35]. Grading the severity of esophagitis, using a recognized endoscopic classification system, is useful for evaluation of the severity of esophagitis and response to treatment. Nevertheless, a recent study randomized patients with uncomplicated GERD to either empiric PPI therapy or endoscopy followed by treatment based on mucosal findings[38] and the result was that empiric therapy was more cost-effective. Although endoscopic determination of the grade of esophagitis can predict the expected healing response to antisecretory agents and the need for effective maintenance regimens[39], GERD treatment is typically guided by symptoms in adults, and thus determination of the grade of esophagitis for most clinical situations is not necessary[40].

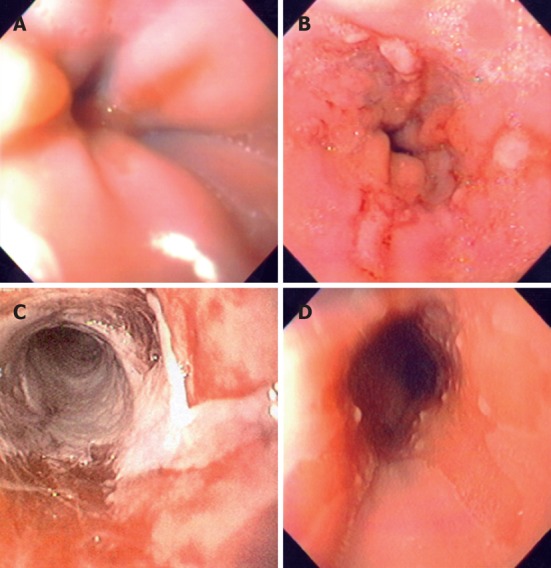

The endoscopic classification criteria for GERD more frequently used in the pediatric setting are Hetzel-Dent[41] and Savary-Miller[42] classification (Table 1). Both have been used in several studies in children[43-49] whereas the Los Angeles classification[21] is generally used for adults, but it can be used also in children (Figure 1). Los Angeles and Hetzel-Dent scoring systems were reproducible in a study that evaluated intra- and inter-observer variability in the endoscopic scoring of esophagitis in adults[36]. However, a recent meta-analysis found significant difference in interpretation and comparison of healing rates for esophagitis among the three classification criteria (Hetzel-Dent, Savary-Miller, and Los Angeles)[50]. Therefore, in order to standardize the interpretation criteria, particularly focusing the healing criteria for a specific acid suppressant therapy, the Los Angeles criteria have been proposed as common criteria in adults and children[11,21].

Table 1.

Classification criteria and grading system of esophago-gastroduodenoscopy findings

| Classification criteria | Grades | Findings |

| Hetzel-Dent[41] | 0 | Indicates no mucosal abnormalities |

| 1 | Erythema, hyperemia, or mucosal friability without macroscopic erosions | |

| 2 | Superficial erosions involving less than 10% of the surface of the distal 5 cm of squamous epithelium | |

| 3 | Erosions or ulcerations involve 10%–50% of the mucosal surface of the distal 5 cm of squamous epithelium | |

| 4 | Deep ulceration anywhere in the esophagus or confluent erosion involving more than 50% of the mucosal surface of the distal 5 cm of squamous epithelium | |

| Savary-Miller[42] | I | One or more supravestibular, nonconfluent reddish spots with or without exudates |

| II | Erosive and exudative lesions in the distal esophagus that may be confluent, but not circumferential | |

| III | Circumferential erosions in the distal esophagus, covered by hemorrhagic and pseudomembranous exudates | |

| IV | Presence of chronic complications such as deep ulcers, stenosis, or scarring with Barrett’s metaplasia | |

| Los Angeles[21] | A | One or more mucosal breaks, each ≤ 5 mm in length |

| B | At least one mucosal break > 5 mm long, but not continuous between the tops of adjacent mucosal folds | |

| C | At least one mucosal break that is continuous between the tops of adjacent mucosal folds, but which is not circumferential (< 75% of luminal circumference) | |

| D | Mucosal break that involves at least 75% of the luminal circumference |

Figure 1.

Endoscopy findings. A: Endoscopy of a child with esophagitis Los Angeles grade A showing one mucosal break < 5 mm in length; B: Another child with Los Angeles grade B showing 3 mucosal breaks > 5 mm long not continuous between the tops of adjacent mucosal folds; C: Endoscopy of a child with esophagitis Los Angeles grade D with mucosal break that involves at least 75% of the luminal circumference; D: Another 14-year-old patient with Barrett esophagus showing an area of endoscopically suspected esophageal metaplasia.

The presence of endoscopically normal esophageal mucosa does not exclude a diagnosis of NERD or esophagitis of other etiologies[51-54]. Acid reflux episodes, volume, and acid clearance are important factors in the pathogenesis of reflux-induced lesions. Nonacid reflux is involved in the development of reflux symptoms in both NERD and EE patients[55]. The diagnostic yield of endoscopy is generally greater if multiple samples of good size and orientation are obtained from biopsy sites that are identified relative to major esophageal land marks[19,56,57].

There is insufficient evidence to support the use of histology to diagnose or exclude GERD[11]. Several variables have an impact on the validity of histology as a diagnostic tool for reflux esophagitis[54,58]. These include sampling error because of the patchy distribution of inflammatory changes and a lack in standardization of biopsy location, tissue processing, and interpretation of morphometric parameters. Histologic findings of elongation of papillae and basal hyperplasia are nonspecific reactive changes that may be found in esophagitis of other causes or in healthy volunteers[53,54,58-60].

The primary role for esophageal histology is to rule out other conditions in the differential diagnosis, such as eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE), Crohn disease, BE, and infection[12,53]. EoE may have typical endoscopic features such as speckled exudates, trachealization of the esophagus, or linear furrowing; however in up to 30% of cases the esophageal mucosal appearance may be normal[51]. Two to 4 mucosal biopsy specimens of the proximal and distal esophagus should be obtained aiming diagnosis of EoE[52]. The number of eosinophils more than 15/phf is the major histological criterion of EoE[51,52]; however eosinophils have been found in a lower number in the esophageal mucosa of asymptomatic infants younger than 1 year of age[61], and in symptomatic infants with cow’s milk-protein allergy[62].

Electron microscopy of esophageal biopsies suggested that dilated intercellular spaces might be an early marker of mucosal damage in GERD, which occurs in NERD patients irrespective of esophageal acid exposure[63,64]. These observations are important but remain research tools.

Finally, endoscopically visible breaks in the distal esophageal mucosa are the most reliable evidence of reflux esophagitis. Mucosal erythema, pallor, and increased or decreased vascular pattern are highly subjective and nonspecific findings that are variations of normal. Histologic findings of eosinophilia, elongated papillae, basilar hyperplasia, and dilated intercellular spaces, alone or in combination, are insufficiently sensitive or specific to diagnose reflux esophagitis. Conversely, absence of these histologic changes does not rule out GERD. Endoscopic biopsy is important to identify or rule out other causes of esophagitis, and to diagnose and monitor BE and its complications.

EGD IN THE MANAGEMENT OF PEDIATRIC PATIENT WITH SUSPECTED GERD

Because the clinical presentation of GERD in infants is not restricted to typical symptoms (heartburn and/or regurgitation) as in older children, adolescents and adults, the several common signs or symptoms in whom an EGD is potentially helpful[11] are as follows.

Heartburn

A management approach to heartburn in older children and adolescents similar to that used in adults may be indicated[11,12]. If GERD is suspected as the most likely cause of symptoms, lifestyle changes, avoidance of precipitating factors, and a 2- to 4-wk trial of PPI are recommended[13]. If symptoms recur when therapy is discontinued, EGD with biopsy may be helpful to diagnose esophagitis and rule out other causes, i.e., EoE that may present with heartburn[11].

Reflux esophagitis

Once reflux esophagitis is diagnosed, initial treatment for 2-3 mo with PPI is recommended. Patients who require higher PPI dose to control symptoms are those with conditions that predispose to severe-chronic GERD and those with higher grades of esophagitis or BE. In most cases, efficacy of therapy can be monitored by extent of symptom relief without routine endoscopic follow-up. Endoscopic monitoring of treatment efficacy may be useful in patients with atypical signs and symptoms, who have persistent symptoms despite adequate acid-suppressive therapy, or who had severe esophagitis at presentation[11].

BE

Esophageal metaplasia of the intestinal type occurs as a function of time and severity of reflux, which explains why it has not been described under 5 years of age and largely occurs over age 10 years[57]. Endoscopically suspected BE was rare (< 0.25%) in children and adolescents who underwent EGD[57], and older age and the presence of hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism (HH) were possible risk factors for BE[65]. BE occurs with greatest frequency in children with underlying conditions putting them at high risk for GERD. The groups of patients at high risk of chronic GERD are those with neurologic impairment, obesity, HH, esophageal atresia, and chronic respiratory disorders. In a group of selected children with severe-chronic GERD, columnar metaplasia was found in 5% and columnar metaplasia with goblet-cell metaplasia was present in another 5%[57]. The diagnosis of BE is both overlooked and overcalled in children[56,57] therefore it is important to accurately diagnose BE, especially in light of the proposed new criteria for the diagnosis of BE in children and adults[12,13]. This is of particular importance in children with severe esophagitis, in whom landmarks at endoscopy may be obscured by bleeding or exudate, or when landmarks are displaced by anatomic abnormalities or HH[19,56,57]. In these circumstances, a course of high-dose PPIs for at least 12 wk is advised to better visualize the landmarks in a following endoscopy[56]. When biopsies from ESEM show columnar epithelium, the term BE should be applied and the presence or absence of intestinal metaplasia specified[12,13,66].

EoE

EoE is a clinicopathological entity isolated to the esophagus characterized by a set of symptoms similar to GERD and eosinophilic infiltration of the esophageal epithelium. EoE represents a chronic, immune/antigen-mediated esophageal disease characterized clinically by symptoms related to esophageal dysfunction and histologically by eosinophil-predominant inflammation. Infants and toddlers often present with feeding difficulties, whereas school-aged children and are more likely to present with vomiting or pain, and adolescents with dysphagia. EoE in children is most often present in association with other manifestations of atopic diathesis (food allergy, asthma, eczema, chronic rhinitis, and environmental allergies). The disease is isolated to the esophagus, and other causes of esophageal eosinophilia should be excluded. A subgroup of patients with EoE has been increasingly recognized as having PPI-responsive esophageal eosinophilia. These patients usually have typical EoE symptoms and GERD diagnostically excluded, but with clinicopathologic response to PPIs. It is important to establish the differential diagnosis among GERD, EoE and PPI-responsive esophageal eosinophilia as it implies distinct treatments. EGD with biopsy is currently the only reliable diagnostic test for EoE[52].

Dysphagia and food refusal

In the infant with feeding refusal, acid suppression without earlier diagnostic evaluation is not recommended. An upper gastrointestinal (GI) contrast study is useful but not required for the infant with feeding refusal or difficulty or the older child reporting dysphagia. Its major use is to identify a non-GERD disorder such as achalasia or foreign body or to identify esophageal narrowing from a stricture. In children and adolescents who report dysphagia or odynophagia EGD with biopsy is useful to distinguish among causes of esophagitis, p.e. EoE[11].

Child aged more than 18 mo with chronic regurgitation or vomiting

According to the natural history of GER, vomiting and regurgitation are less common in children older than 18 mo of age as these symptoms ameliorate after this age in the vast majority. Although these symptoms are not unique to GERD, evaluation to diagnose possible GERD and to rule out alternative diagnosis is recommended. Testing may include EGD, and/or esophageal pH/impedance monitoring, and/or barium upper GI series[11].

Infants with unexplained crying/distressed behavior

Few studies addressed the appropriate management of infants with irritability and reflux symptoms[67,68] and there is a lack of evidence to support an empiric trial of acid suppression therapy in infants with unexplained crying, irritability, or sleep disturbance. On the other hand, irritable infants may benefit from an empiric trial with hypoallergenic diet following diagnostic evaluations to rule out other conditions causing irritability[11,69,70]. However, if irritability persists with no explanation other than suspected GERD, additional investigations to assess the relationship between reflux episodes and symptoms or to diagnose reflux or other causes of esophagitis may be indicated. In such cases EGD, pH monitoring or impedance monitoring may be helpful[11].

EGD may be a useful tool to assess GER in children with other signs and symptoms suggestive of GERD such as apnea or apparent life threatening event; reactive airways disease; recurrent pneumonia; upper airway symptoms; dental erosions; Sandifer syndrome. In all cases, a rational decision should be taken considering all the available tests other than endoscopy that could be helpful to the better management of a child with GERD.

NOVEL EGD TECHNOLOGIES

The role of newer endoscopic technologies-including narrow band imaging to enhance the contrast between esophageal and gastric mucosa, endoscopic functional luminal imaging probe to assess the esophagogastric junction compliance; videotelemetry capsule endoscopy, and ultra-thin unsedated transnasal endoscopy-for the diagnosis of GERD is controversial, primarily because of a lack of comparison with other validated tests[71,72]. No studies regarding these new techniques have been performed in children.

ENDOLUMINAL THERAPY OF GERD

Over the last decade, various endoluminal innovative techniques aiming to reduce reflux and GERD symptoms were enthusiastically developed. Endoluminal procedures have emerged as a new therapeutic option for GERD treatment: radiofrequency ablation to create submucosal thermal lesions in the smooth muscles of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES), injection of biopolymer substances into the muscular layer of the LES, and transmural plication and suturing devices to create pleats in the GEJ. The procedure devices were removed from the market by the manufacturers due to a variety of problems, including serious adverse events such as esophageal perforation and lack of efficacy[73-75]. Two techniques are currently being evaluated: radiofrequency (Stretta)[76] and full thickness plication or endoluminal fundoplication. Durability still needs to be determined for the sole technique that remains available (EsophyX)[77].

Regarding the pediatric population, few studies of endoluminal treatment for GERD have been performed in this group population. Endoluminal plication (EndoCinch) was performed in 17 patients aged 6-15 years. A sustained improvement in symptoms was seen at 3-year but not at 5-year follow up[78]. The endoluminal antireflux procedure (Stretta) was described in another series of patients aged 11-16 years[79], however long-term results are needed.

In conclusion, EGD has contributed greatly to the understanding and management of GERD and will continue to play an important role. New technology and better use of available resources such as more extensive and well informed use of histopathology is likely to yield better clinical results.

Footnotes

Supported by Hospital de Clinicas de Porto Alegre, Porto Alegre-RS, Brazil

Peer reviewer: Paola De Angelis, MD, Digestive Surgery and Endoscopy Unit, Pediatric Hospital Bambino Gesù, Piazza S. Onofrio, 400165 Rome, Italy

S- Editor Song XX L- Editor A E- Editor Zheng XM

References

- 1.Vakil N. Disease definition, clinical manifestations, epidemiology and natural history of GERD. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;24:759–764. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2010.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ryan AM, Duong M, Healy L, Ryan SA, Parekh N, Reynolds JV, Power DG. Obesity, metabolic syndrome and esophageal adenocarcinoma: epidemiology, etiology and new targets. Cancer Epidemiol. 2011;35:309–319. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ruigómez A, Wallander MA, Lundborg P, Johansson S, Rodriguez LA. Gastroesophageal reflux disease in children and adolescents in primary care. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:139–146. doi: 10.3109/00365520903428606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.El-Serag HB, Gilger M, Carter J, Genta RM, Rabeneck L. Childhood GERD is a risk factor for GERD in adolescents and young adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:806–812. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.30098.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nelson SP, Chen EH, Syniar GM, Christoffel KK. Prevalence of symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux during infancy. A pediatric practice-based survey. Pediatric Practice Research Group. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1997;151:569–572. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1997.02170430035007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martin AJ, Pratt N, Kennedy JD, Ryan P, Ruffin RE, Miles H, Marley J. Natural history and familial relationships of infant spilling to 9 years of age. Pediatrics. 2002;109:1061–1067. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.6.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hegar B, Boediarso A, Firmansyah A, Vandenplas Y. Investigation of regurgitation and other symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux in Indonesian infants. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:1795–1797. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i12.1795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miyazawa R, Tomomasa T, Kaneko H, Tachibana A, Ogawa T, Morikawa A. Prevalence of gastro-esophageal reflux-related symptoms in Japanese infants. Pediatr Int. 2002;44:513–516. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-200x.2002.01609.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nelson SP, Chen EH, Syniar GM, Christoffel KK. One-year follow-up of symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux during infancy. Pediatric Practice Research Group. Pediatrics. 1998;102:E67. doi: 10.1542/peds.102.6.e67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campanozzi A, Boccia G, Pensabene L, Panetta F, Marseglia A, Strisciuglio P, Barbera C, Magazzù G, Pettoello-Mantovani M, Staiano A. Prevalence and natural history of gastroesophageal reflux: pediatric prospective survey. Pediatrics. 2009;123:779–783. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vandenplas Y, Rudolph CD, Di Lorenzo C, Hassall E, Liptak G, Mazur L, Sondheimer J, Staiano A, Thomson M, Veereman-Wauters G, et al. Pediatric gastroesophageal reflux clinical practice guidelines: joint recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (NASPGHAN) and the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;49:498–547. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181b7f563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sherman PM, Hassall E, Fagundes-Neto U, Gold BD, Kato S, Koletzko S, Orenstein S, Rudolph C, Vakil N, Vandenplas Y. A global, evidence-based consensus on the definition of gastroesophageal reflux disease in the pediatric population. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1278–1295; quiz 1296. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, Dent J, Jones R. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1900–1920; quiz 1943. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moayyedi P, Talley NJ. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Lancet. 2006;367:2086–2100. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68932-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Orenstein SR, Shalaby TM, Cohn JF. Reflux symptoms in 100 normal infants: diagnostic validity of the infant gastroesophageal reflux questionnaire. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 1996;35:607–614. doi: 10.1177/000992289603501201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kleinman L, Rothman M, Strauss R, Orenstein SR, Nelson S, Vandenplas Y, Cucchiara S, Revicki DA. The infant gastroesophageal reflux questionnaire revised: development and validation as an evaluative instrument. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:588–596. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lacy BE, Weiser K, Chertoff J, Fass R, Pandolfino JE, Richter JE, Rothstein RI, Spangler C, Vaezi MF. The diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Med. 2010;123:583–592. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2010.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dent J, Vakil N, Jones R, Bytzer P, Schöning U, Halling K, Junghard O, Lind T. Accuracy of the diagnosis of GORD by questionnaire, physicians and a trial of proton pump inhibitor treatment: the Diamond Study. Gut. 2010;59:714–721. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.200063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gillett P, Hassall E. Pediatric gastrointestinal mucosal biopsy. Special considerations in children. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2000;10:669–712, vi-vii. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zion N, Chemodanov E, Levine A, Sukhotnik I, Bejar J, Shaoul R. The yield of a continuously patent gastroesophageal junction during upper endoscopy as a predictor of esophagitis in children. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:3102–3107. doi: 10.1007/s10620-010-1128-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lundell LR, Dent J, Bennett JR, Blum AL, Armstrong D, Galmiche JP, Johnson F, Hongo M, Richter JE, Spechler SJ, et al. Endoscopic assessment of oesophagitis: clinical and functional correlates and further validation of the Los Angeles classification. Gut. 1999;45:172–180. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.2.172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Richter JE. Diagnostic tests for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Med Sci. 2003;326:300–308. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200311000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.An evidence-based appraisal of reflux disease management--the Genval Workshop Report. Gut. 1999;44 Suppl 2:S1–16. doi: 10.1136/gut.44.2008.s1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ronkainen J, Aro P, Storskrubb T, Johansson SE, Lind T, Bolling-Sternevald E, Graffner H, Vieth M, Stolte M, Engstrand L, Talley NJ, Agréus L. High prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux symptoms and esophagitis with or without symptoms in the general adult Swedish population: a Kalixanda study report. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:275–285. doi: 10.1080/00365520510011579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones RH, Hungin APS, Phillips J, Mills JG. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in primary care in Europe: Clinical presentation and endoscopic findings. Eur J Gen Pract. 1995;1:149–154. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smout AJPM. Endoscopy-negative acid reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997;11:81–85. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lind T, Havelund T, Carlsson R, Anker-Hansen O, Glise H, Hernqvist H, Junghard O, Lauritsen K, Lundell L, Pedersen SA, et al. Heartburn without oesophagitis: efficacy of omeprazole therapy and features determining therapeutic response. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1997;32:974–979. doi: 10.3109/00365529709011212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robinson M, Earnest D, Rodriguez-Stanley S, Greenwood-Van Meerveld B, Jaffe P, Silver MT, Kleoudis CS, Wilson LE, Murdock RH. Heartburn requiring frequent antacid use may indicate significant illness. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:2373–2376. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.21.2373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fass R, Fennerty MB, Vakil N. Nonerosive reflux disease--current concepts and dilemmas. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:303–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Savarino E, Zentilin P, Tutuian R, Pohl D, Casa DD, Frazzoni M, Cestari R, Savarino V. The role of nonacid reflux in NERD: lessons learned from impedance-pH monitoring in 150 patients off therapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2685–2693. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.02119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gilger MA, El-Serag HB, Gold BD, Dietrich CL, Tsou V, McDuffie A, Shub MD. Prevalence of endoscopic findings of erosive esophagitis in children: a population-based study. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008;47:141–146. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31815eeabe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.El-Serag HB, Gilger M, Kuebeler M, Rabeneck L. Extraesophageal associations of gastroesophageal reflux disease in children without neurologic defects. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:1294–1299. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.29545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hershcovici T, Fass R. Nonerosive Reflux Disease (NERD) - An Update. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;16:8–21. doi: 10.5056/jnm.2010.16.1.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bytzer P, Havelund T, Hansen JM. Interobserver variation in the endoscopic diagnosis of reflux esophagitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1993;28:119–125. doi: 10.3109/00365529309096057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vieth M, Haringsma J, Delarive J, Wiesel PH, Tam W, Dent J, Tytgat GN, Stolte M, Lundell L. Red streaks in the oesophagus in patients with reflux disease: is there a histomorphological correlate. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2001;36:1123–1127. doi: 10.1080/00365520152584725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pandolfino JE, Vakil NB, Kahrilas PJ. Comparison of inter- and intraobserver consistency for grading of esophagitis by expert and trainee endoscopists. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:639–643. doi: 10.1067/mge.2002.129220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rath HC, Timmer A, Kunkel C, Endlicher E, Grossmann J, Hellerbrand C, Herfarth HH, Lock G, Sahrbacher U, Schölmerich J, et al. Comparison of interobserver agreement for different scoring systems for reflux esophagitis: Impact of level of experience. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:44–49. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)01289-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Giannini EG, Zentilin P, Dulbecco P, Vigneri S, Scarlata P, Savarino V. Management strategy for patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease: a comparison between empirical treatment with esomeprazole and endoscopy-oriented treatment. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:267–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01659.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vigneri S, Termini R, Leandro G, Badalamenti S, Pantalena M, Savarino V, Di Mario F, Battaglia G, Mela GS, Pilotto A. A comparison of five maintenance therapies for reflux esophagitis. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1106–1110. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199510263331703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kahrilas PJ, Shaheen NJ, Vaezi MF, Hiltz SW, Black E, Modlin IM, Johnson SP, Allen J, Brill JV. American Gastroenterological Association Medical Position Statement on the management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1383–1391, 1391.e1-1391.e5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.08.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hetzel DJ, Dent J, Reed WD, Narielvala FM, Mackinnon M, McCarthy JH, Mitchell B, Beveridge BR, Laurence BH, Gibson GG. Healing and relapse of severe peptic esophagitis after treatment with omeprazole. Gastroenterology. 1988;95:903–912. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(88)90162-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Savary M, Miller G. The esophagus. In: Savary M, Miller G, editors. Handbook and atlas of endoscopy. Solothurn: Verlag Gassman AG; 1978. pp. 119–205. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gunasekaran TS, Hassall EG. Efficacy and safety of omeprazole for severe gastroesophageal reflux in children. J Pediatr. 1993;123:148–154. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)81561-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Boccia G, Manguso F, Miele E, Buonavolontà R, Staiano A. Maintenance therapy for erosive esophagitis in children after healing by omeprazole: is it advisable. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1291–1297. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hassall E, Israel D, Shepherd R, Radke M, Dalväg A, Sköld B, Junghard O, Lundborg P. Omeprazole for treatment of chronic erosive esophagitis in children: a multicenter study of efficacy, safety, tolerability and dose requirements. International Pediatric Omeprazole Study Group. J Pediatr. 2000;137:800–807. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2000.109607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Somani SK, Ghoshal UC, Saraswat VA, Aggarwal R, Misra A, Krishnani N, Naik SR. Correlation of esophageal pH and motor abnormalities with endoscopic severity of reflux esophagitis. Dis Esophagus. 2004;17:58–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2004.00374.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Madrazo-de la Garza A, Dibildox M, Vargas A, Delgado J, Gonzalez J, Yañez P. Efficacy and safety of oral pantoprazole 20 mg given once daily for reflux esophagitis in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2003;36:261–265. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200302000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Van Biervliet S, Van Winckel M, Robberecht E, Kerremans I. High-dose omeprazole in esophagitis with stenosis after surgical treatment of esophageal atresia. J Pediatr Surg. 2001;36:1416–1418. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2001.26388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Böhmer CJ, Niezen-de Boer MC, Klinkenberg-Knol EC, Devillé WL, Nadorp JH, Meuwissen SG. The prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux disease in institutionalized intellectually disabled individuals. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:804–810. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.00854.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yaghoobi M, Padol S, Yuan Y, Hunt RH. Impact of oesophagitis classification in evaluating healing of erosive oesophagitis after therapy with proton pump inhibitors: a pooled analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;22:583–590. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e328335d95d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Furuta GT, Liacouras CA, Collins MH, Gupta SK, Justinich C, Putnam PE, Bonis P, Hassall E, Straumann A, Rothenberg ME. Eosinophilic esophagitis in children and adults: a systematic review and consensus recommendations for diagnosis and treatment. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1342–1363. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liacouras CA, Furuta GT, Hirano I, Atkins D, Attwood SE, Bonis PA, Burks AW, Chehade M, Collins MH, Dellon ES, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: updated consensus recommendations for children and adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:3–20.e6; quiz 21-22. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dahms BB. Reflux esophagitis: sequelae and differential diagnosis in infants and children including eosinophilic esophagitis. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2004;7:5–16. doi: 10.1007/s10024-003-0203-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dent J. Microscopic esophageal mucosal injury in nonerosive reflux disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:4–16. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Savarino E, Tutuian R, Zentilin P, Dulbecco P, Pohl D, Marabotto E, Parodi A, Sammito G, Gemignani L, Bodini G, et al. Characteristics of reflux episodes and symptom association in patients with erosive esophagitis and nonerosive reflux disease: study using combined impedance-pH off therapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1053–1061. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hassall E. Esophageal metaplasia: definition and prevalence in childhood. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:676–677. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hassall E, Kerr W, El-Serag HB. Characteristics of children receiving proton pump inhibitors continuously for up to 11 years duration. J Pediatr. 2007;150:262–267, 267.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.08.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.van Malenstein H, Farré R, Sifrim D. Esophageal dilated intercellular spaces (DIS) and nonerosive reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1021–1028. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Salvatore S, Hauser B, Vandemaele K, Novario R, Vandenplas Y. Gastroesophageal reflux disease in infants: how much is predictable with questionnaires, pH-metry, endoscopy and histology. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2005;40:210–215. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200502000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Spechler SJ, Genta RM, Souza RF. Thoughts on the complex relationship between gastroesophageal reflux disease and eosinophilic esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1301–1306. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Orenstein SR, Shalaby TM, Kelsey SF, Frankel E. Natural history of infant reflux esophagitis: symptoms and morphometric histology during one year without pharmacotherapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:628–640. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hill DJ, Heine RG, Cameron DJ, Catto-Smith AG, Chow CW, Francis DE, Hosking CS. Role of food protein intolerance in infants with persistent distress attributed to reflux esophagitis. J Pediatr. 2000;136:641–647. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2000.104774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Caviglia R, Ribolsi M, Maggiano N, Gabbrielli AM, Emerenziani S, Guarino MP, Carotti S, Habib FI, Rabitti C, Cicala M. Dilated intercellular spaces of esophageal epithelium in nonerosive reflux disease patients with physiological esophageal acid exposure. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:543–548. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.40978.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Farré R, Fornari F, Blondeau K, Vieth M, De Vos R, Bisschops R, Mertens V, Pauwels A, Tack J, Sifrim D. Acid and weakly acidic solutions impair mucosal integrity of distal exposed and proximal non-exposed human oesophagus. Gut. 2010;59:164–169. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.194191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.El-Serag HB, Gilger MA, Shub MD, Richardson P, Bancroft J. The prevalence of suspected Barrett’s esophagus in children and adolescents: a multicenter endoscopic study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:671–675. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hassall E. Cardia-type mucosa as an esophageal metaplastic condition in children: “Barrett esophagus, intestinal metaplasia-negative”. [corrected] J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008;47:102–106. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31815ed0d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jordan B, Heine RG, Meehan M, Catto-Smith AG, Lubitz L. Effect of antireflux medication, placebo and infant mental health intervention on persistent crying: a randomized clinical trial. J Paediatr Child Health. 2006;42:49–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2006.00786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Moore DJ, Tao BS, Lines DR, Hirte C, Heddle ML, Davidson GP. Double-blind placebo-controlled trial of omeprazole in irritable infants with gastroesophageal reflux. J Pediatr. 2003;143:219–223. doi: 10.1067/S0022-3476(03)00207-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lucassen PL, Assendelft WJ, Gubbels JW, van Eijk JT, Douwes AC. Infantile colic: crying time reduction with a whey hydrolysate: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2000;106:1349–1354. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.6.1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hill DJ, Hudson IL, Sheffield LJ, Shelton MJ, Menahem S, Hosking CS. A low allergen diet is a significant intervention in infantile colic: results of a community-based study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1995;96:886–892. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(95)70224-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sharma P, Wani S, Bansal A, Hall S, Puli S, Mathur S, Rastogi A. A feasibility trial of narrow band imaging endoscopy in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:454–464; quiz 674. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Amano Y, Yamashita H, Koshino K, Ohshima T, Miwa H, Iwakiri R, Fujimoto K, Manabe N, Haruma K, Kinoshita Y. Does magnifying endoscopy improve the diagnosis of erosive esophagitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:1063–1068. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2008.05453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hogan WJ. Clinical trials evaluating endoscopic GERD treatments: is it time for a moratorium on the clinical use of these procedures. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:437–439. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Louis H, Devière J. Ensocopic-endoluminal therapies. A critical appraisal. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;24:969–979. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Vassiliou MC, von Renteln D, Rothstein RI. Recent advances in endoscopic antireflux techniques. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2010;20:89–101, vii. doi: 10.1016/j.giec.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Aziz AM, El-Khayat HR, Sadek A, Mattar SG, McNulty G, Kongkam P, Guda MF, Lehman GA. A prospective randomized trial of sham, single-dose Stretta, and double-dose Stretta for the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:818–825. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0671-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Velanovich V. Endoscopic, endoluminal fundoplication for gastroesophageal reflux disease: initial experience and lessons learned. Surgery. 2010;148:646–651; discussion 651-653. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2010.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Thomson M, Antao B, Hall S, Afzal N, Hurlstone P, Swain CP, Fritscher-Ravens A. Medium-term outcome of endoluminal gastroplication with the EndoCinch device in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008;46:172–177. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31814d4de1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Liu DC, Somme S, Mavrelis PG, Hurwich D, Statter MB, Teitelbaum DH, Zimmermann BT, Jackson CC, Dye C. Stretta as the initial antireflux procedure in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40:148–151; discussion 151-152. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2004.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]