Abstract

Introduction

Reactive metabolite-mediated toxicity is frequently limited to the organ where the electrophilic metabolites are generated. Some reactive metabolites however, might have the ability to translocate from their site of formation. This suggests that for these reactive metabolites, investigations into the role of organs other than the one directly affected could be relevant to understanding the mechanism of toxicity.

Areas covered

The authors discuss the physiological and biochemical factors that can enable reactive metabolites to cause toxicity in an organ distal from the site of generation. Furthermore, the authors present a case study which describes studies that demonstrate that S-(1,2-dichlorovinyl)-L-cysteine sulfoxide (DCVCS) and N-acetyl-S-(1,2-dichlorovinyl-L-cysteine sulfoxide (N-AcDCVCS), reactive metabolites of the known trichloroethylene metabolites S-(1,2-dichlorovinyl)-L-cysteine (DCVC) and N-acetyl-S-(1,2-dichlorovinyl)-L-cysteine (N-AcDCVC), are generated in the liver and translocate through the circulation to the kidney to cause nephrotoxicity.

Expert Opinion

The ability of reactive metabolites to translocate could be important to consider when investigating mechanisms of toxicity. A mechanistic approach, similar to the one described for DCVCS and N-AcDCVCS, could be useful in determining the role of circulating reactive metabolites in extrahepatic toxicity of drugs and other chemicals. If this is the case, intervention strategies that would not otherwise be feasible might be effective for reducing extrahepatic toxicity.

1. Introduction

All bodily systems in an organism are potentially susceptible to adverse side effects and toxicity induced by drugs and other chemicals. These undesirable effects represent a significant clinical concern, because they can lead to morbidity and mortality [1, 2]. They can also limit the utility of otherwise effective treatments. In some cases, adverse reactions to a drug in a minority of patients have led to withdrawal of the drug from general use [3].

Drugs or chemicals absorbed through the gastrointestinal tract into the hepatic-portal blood system are carried into the liver. Since the liver is one of the tissues first exposed to ingested compounds before its dilution in the systemic circulation, the liver is exposed to high concentrations of these chemicals. Indeed, because of the liver’s location, structure, and high metabolic capability, liver cells are readily exposed to both ingested drugs and their potentially toxic metabolites that are formed in these cells. However, because the liver has a large regenerative capacity and has a large functional reserve because of its relatively homogenous structure, diagnosis of drug-induced liver injury solely based on clinical signs can be difficult. In addition, many extrahepatic tissues are susceptible to drug-induced toxicity (Table 1).

Table 1.

Selected examples of drugs that induce extrahepatic toxicity and their reactive intermediate(s).

| Target Organ | Drug | Reactive Intermediate | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bladder | Cyclophosphamide | α,β-unsaturated aldehyde | [4,5] |

| Blood Cells | Dapsone | Nitroso derivative, Nitrenium ion |

[6] |

| Procainamide | Nitroso derivative; Nitrenium ion |

[7,8] | |

| Bone Marrow | Chloramphenicol | Nitroso derivative, Reactive acyl halide |

[9,10] |

| Kidney | Acetaminophen | Quinone-imine | [11,12] |

| Acyclovir | Reactive Aldehyde | [13] | |

| Ifosfamide | α-halo aldehyde | [14] | |

| Lung | 1,3-Bis-2-chloroethyl-1-nitrosourea | Isocyanate | [15] |

A particular drug’s ability to cause toxicity in a specific target organ depends on a number of drug- and organ-related factors. The situation becomes more complicated if toxicity is not induced by the parent drug, but rather by a reactive electrophilic metabolite. If this is the case, three possible scenarios could explain target organ-toxicity: (1) the reactive metabolite is primarily formed in the target organ and because of the metabolite’s high electrophilicity and short half-life it is unlikely to transfer to another tissue, (2) the reactive metabolite is sufficiently stable or can exist in an equilibrium with a somewhat more stable form that can translocate to the target organ where it directly interacts with sensitive cellular targets to cause toxicity, or (3) a combination of the two mechanisms (i.e. the metabolite translocates from the organ where it is formed to the target organ, where further metabolism yields the ultimate toxic metabolite).

In this review, an overview of this second scenario will be described. First, the chemical and biochemical properties of a drug, specifically with regards to its bioactivation, chemical stability, and reactivity under physiological conditions will be presented. The physiological and biochemical factors that make some organs particularly susceptible to toxicity will then be described. Since induction of extrahepatic toxicity is not limited to drugs, as many environmental pollutants and dietary contaminants also have the potential to cause extrahepatic adverse effects, a case study describing the formation, disposition, and nephrotoxicity of metabolites of the environmental toxicant, trichloroethylene (TCE), will be presented. This case study represents an example of the type of investigative strategy that can be used to demonstrate that the toxicity of a drug is mediated in part by the ability of a reactive metabolite to be formed in one organ followed by its translocation to cause damage in a distal organ. Finally, we will present a discussion of the toxicological implications of extrahepatic toxicity caused by circulating reactive metabolites and potential intervention strategies to minimize extrahepatic toxicity caused by these circulating reactive metabolites.

2. Reactive metabolites: bioactivation, stability, and reactivity

Many of the drugs that cause extrahepatic toxicity require metabolism to form reactive intermediates that are associated with toxicity. Drug metabolizing enzymes introduce a functional group to the xenobiotic compound via oxidation, reduction, or hydrolysis reactions or are involved in conjugation reactions utilizing the added functional group to attach endogenous molecules. Often, the fundamental process in these pathways is to detoxify lipophilic compounds by making them more hydrophilic, but for many drugs, the metabolites that are generated are more toxic than the parent compound; this process is known as bioactivation.

All drug metabolizing pathways have the potential to be involved in bioactivation processes. Furthermore, these pathways result in the formation of many different types of reactive metabolites, including carbonium ions, nitrenium ions, nitroso derivatives, iminium ions, epoxides, quinones, ketenes, α,β-unsaturated carbonyl compounds, acylhalides, isocyanates, and acyl glucoronides [8]. The type of reactive metabolite formed is dependent on the functional groups in the compound. For example, aromatic amines can be metabolized to quinone-imines, the type of metabolite of acetaminophen that has been implicated in its nephrotoxicity and hepatotoxicity [12,16], or nitroso derivatives and nitrenium ions, the types of metabolites derived from the antiarryhthmic agent procainamide that may be involved in the induction of drug-induced lupus erythematosus [7,8]. Metabolism of the anti-cancer drug cyclophosphamide leads to formation of the α,β-unsaturated aldehyde acrolein, which is associated with bladder toxicity [4,5]. Metabolism of ifosfamide leads to the formation of the α-haloaldehyde chloroacetaldehyde, which has been implicated in the neurotoxic or nephrotoxic effects of this anti-cancer drug [14,17].

Direct detection of reactive metabolites in biological samples is often complicated by the fact that many have short half-lives. As a result, many reactive metabolites can only be characterized after being trapped by nucleophilic compounds or after isolation and characterization of adducts or degradation products. For example, acetaminophen bioactivation results in the formation of a quinone-imine intermediate N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine (NAPQI) that is a highly reactive electrophile. Direct detection of NAPQI is difficult due to it readily reacting with sulfhydryl-containing molecules [18,19]. Evidence of NAPQI formation in vivo has been based on the detection of glutathione (GSH) conjugates, the cysteine (Cys) and N-acetyl cysteine (NAC) conjugates that are further metabolites of the GSH conjugates, and hemoglobin adducts [8,12,16,18].

Variations in reactivity are present not only between different chemical types of reactive electrophilic intermediates, but also among individual members of each type. For example, acrolein, 4-hydroxynonenal, and crotonaldehyde are all α,β-unsaturated aldehydes that can act as Michael acceptors in reactions with soft nucleophiles, but the compounds exhibit differences in the second-order rate constant in the presence of GSH (acrolein: 121 M−1s−1, crotonaldehyde: 0.785 M−1s−1, and 4-hydroxynonenal: 1.09 M−1s−1) [20,21]. This suggests that the type of reactive functional group is not the sole determining factor in reactive metabolite reactivity. Electrophilicity, stability, and presence of other substituents in the compound all affect metabolite reactivity. In vitro neurotoxicity induced by various α,β-unsaturated carbonyl derivatives was shown to correlate with the compound’s electrophilicity and the second-order rate constant for the reaction of these compounds with NAC [22]. The difference in the rate constants of acrolein and crotonaldehyde toward GSH indicates that substituents on the β carbon can affect reactivity. The presence of electron withdrawing groups in the 4-hydroxyalkenals is responsible for the higher reactivity of these compounds compared to α,β-unsaturated aldehydes that lack this type of substituent [20,21]. The individual contributions of these factors have been used to generate models to predict variations in reactivity for members of a reactive metabolite family. It was demonstrated that local electrophilicity at the β carbon, resonance stabilization of the transition state, and steric hindrance at the reaction site provide sufficient data to create a model for predicting Michael acceptor reactivity toward GSH [23].

Another aspect of a reactive metabolite’s chemical properties that is important in determining its mechanism of toxicity is the ability to interact with cellular constituents. While in some cases this can lead to the quick depletion of a reactive metabolite, the formation of reversible conjugates is a chemical process that can extend the half-life of a reactive metabolite. The quinone-imine intermediate of acetaminophen, NAPQI, can form a labile ipso adduct with GSH and sulfhydryl-containing proteins [17]. Although NAPQI is often detected in biological systems in the form of adducts and degradation products, the half-life of the decomposition of the ipso GSH adduct was shown to be pH dependent and was maximal (33 min) at pH 6 [17]. This suggests that the adduct has sufficient stability and can potentially explain the ability of NAPQI to translocate from the hepatocyte endoplasmic reticulum, where it is formed, and expose other cellular compartments and extracellular targets, such as hemoglobin [16], to covalent modification and oxidation by NAPQI.

Another important consequence of differences in reactivity is the variations in the selectivity of reactive metabolites for different cellular targets. Generally, high reactivity of a metabolite is associated with a short half-life and low specificity for targets. The relationship between reactivity and selectivity was demonstrated by the fact that the stability (lifetime) of carbocations of 1-phenylethyl derivatives generally correlates with selectivity toward nucleophiles [24]. For a group of related carbocations, the deleterious effects can correlate with reactivity until a threshold is reached where reactivity is so high that the interactions with solvent predominate and the correlation is no longer valid [25]. The implication of these studies is that reactive metabolites that demonstrate moderate reactivity could represent a more significant toxicological concern than highly reactive compounds due to the selectivity imparted by the stability of the reactive metabolite. As a result, a moderately reactive metabolite could alter specific critical targets whereas the promiscuity of a highly reactive metabolite means that its targets will be more likely based on proximity and may not necessarily be critical for cellular function.

3. Extrahepatic target organs: physiological and biochemical factors that influence susceptibility to toxicity

In addition to the aforementioned reactive metabolite-related factors that play a role in determination of the target organs where toxicity will manifest, there are several physiological and biochemical characteristics that determine a target organ’s potential susceptibility to toxicity. Three important tissue-related factors [26] that are important in predisposing a specific organ to toxicity are:

Physiological and biochemical aspects that affect degree of exposure to reactive metabolites.

Metabolic capabilities of the tissue to act upon the parent drug or reactive metabolite via bioactivation or detoxifying processes.

The presence of unique sensitive cell types and target molecules within the tissue and the cellular response to damage.

As this review highlights the effects of exposure of a tissue to reactive metabolites in the circulation, the kidney can provide an illustrative example of how these factors play an important role in making a target organ susceptible to a number of toxicants.

3.1 Anatomical, physiological and biochemical aspects that affect degree of exposure to reactive metabolites

The role of the kidney in the excretion of waste products and maintaining the balance of a number of important molecules (e.g. water, salts, etc.) requires unique functions that ultimately make the tissue vulnerable to toxicity induced by reactive metabolites. The kidneys receive a disproportionately large amount of blood flow (25% resting cardiac output) compared to their size (1% of body weight). This suggests that over time, the kidney could be exposed to a large amount of circulating reactive metabolites. In addition, the concentration of reactive metabolites in the luminal fluid can increase greatly as it passes through the nephron, the functional unit of the kidney. After filtration of blood by the glomerulus, the ultrafiltrate passes through the renal tubules, where reabsorption of water takes place, and approximately 5% of the initial fluid volume enters the collecting ducts. As a result of these processes, intraluminal concentrations of reactive metabolites can be increased as much as 200-fold [27]. Concentrated compounds in the luminal fluid can passively diffuse into the epithelium.

Furthermore, although blood flow to the kidney is unequal between the three parts of the kidney (cortex, medulla, and papilla), the location of each section in relation to the vasculature and their roles in renal function make each area susceptible to toxicity for different reasons. Exposure of the cortex to circulating reactive metabolites is high because it receives 90% of total renal blood flow. The medulla is generally less susceptible to toxicity due to the low blood flow to the region, but normal countercurrent mechanisms could concentrate chemicals in tubular urine that passes through the loop of Henle and the medullary collecting duct. The papilla contains the most concentrated luminal fluid, suggesting that it could be exposed to high concentrations of reactive metabolites.

The proximal tubule (PT) is the most common renal tubule to be targeted for toxicity, and there are a number of reasons why reactive metabolites are likely to accumulate in PT cells. The anatomical position of the PT renders it the first tubular epithelial cells exposed to toxicants in the nephron. The PT, as part of its role in reabsorbing solutes and water, has an epithelium that is more permeable to these compounds. There are also numerous transport systems in the PT that scavenge the luminal fluid for metabolic substrates and filtered proteins. In addition, an important excretory function of the PT is to transport organic anions and organic cations from post-glomerular blood into the tubular fluid. The presence of these transport systems in the PT suggest that active transport of reactive metabolites can lead to their accumulation and presence in greatly increased intracellular concentrations compared to systemic concentrations. An example of the importance of the transport systems present in the PT in mediating vulnerability to nephrotoxicants can be found in the nephrotoxicity of β-lactam antibiotics. The organic amino transporter protein 1 (OAT1) on the anti-luminal side of the proximal tubule is involved in secretion of cephalosporins, allowing these compounds to reach high intracellular concentrations [28-30]. In addition, the efflux rates of cephalosporins into the luminal fluid vary by compound, which might contribute to the differences in severity of nephrotoxicity induced by different compounds. For example, the cationic charge of cephaloridine is believed to be responsible for the low excretion rate of the compound into tubular fluid [31,32]. Evidence that toxic injury only occurs with β-lactam antibiotics that are secreted, that toxicity correlates with intracellular concentration, that inhibiting secretory transport reduces toxicity, and that increasing intracellular concentration enhances toxicity demonstrate that tubular transport is an important factor in cephalosporin nephrotoxicity [33].

3.2 Metabolic capabilities of the kidney

Similar to the liver, the kidney plays a role in the processing and removal of xenobiotics from the body. The kidney is a metabolically active tissue and many different classes of enzymes involved in drug metabolism are expressed in the tissue, including cytochrome P450s (CYPs), epoxide hydrolases, flavin-containing monooxygenases (FMOs), prostaglandin H-synthase, glutathione S-transferases (GSTs), and cysteine S-conjugate β-lyase. The action of xenobiotic metabolizing enzymes can result in detoxification or bioactivation of a parent compound, and the balance between detoxifying and bioactivating processes plays a significant role in determining the sensitivity of a tissue to toxicity.

Variation in expression of enzymes involved in drug metabolism likely plays a role in determining which areas of the kidney are vulnerable to damage from a particular reactive metabolite. Similar to the liver, the kidney contains many xenobiotic metabolizing enzymes, although they are generally expressed at a lower level than in the liver. For example, total expression of CYPs, considered the most important family of drug-metabolizing enzymes, in kidney is 10% of the expression in liver [34]. One caveat to this observation is that this does not account for variations in the isoform-specific expression of these enzymes in the kidney. In humans, total CYP3A expression is lower in kidney than liver [34], however unlike in the liver, where CYP3A4 is the predominant cytochrome P450 expressed [35,36], CYP3A5 expression is higher than CYP3A4 in the kidney [37,38]. There are also species-, sex-, age-, and individual-dependent variations in drug-metabolizing enzyme expression. An example of this is the expression of CYP2E1, widely believed to be involved in the nephrotoxicity of a number of drugs including acetaminophen. CYP2E1 has not been detected in human kidney, but is expressed in rat kidney [39]. CYP2E1 is regulated by testosterone in the mouse and therefore is found in greater levels in males than in females [40,41]. Combined with the regional distribution of this enzyme being highest in the PT [40], it suggests that male mouse PT is more sensitive than female mouse PT to toxicity caused by xenobiotic substrates of this enzyme. Collectively, these variations suggest that the enzyme expression profiles of individuals could represent an important risk factor in determining vulnerability to toxicity induced by drugs that require metabolism for effects to manifest.

Furthermore, enzymes involved in drug metabolism show regional differences in expression in the kidney. Expression of CYPs and FMOs is highest in tubular cells, suggesting that reactive metabolites that are substrates of these enzymes are likely to target this area. Conversely, studies utilizing rabbit and guinea pig kidneys have demonstrated that prostaglandin H-synthase shows the opposite pattern, as it is mainly localized in the collecting ducts and papilla, suggesting that substrates of this enzyme could be involved in papillary toxicity. A number of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, such as ibuprofen and indomethacin, are known substrates of prostaglandin H-synthase, and can cause renal papillary necrosis [27].

Another important set of enzymes that are expressed in kidney are involved in cytoprotection. Renal cytoprotective mechanisms include utilization of GSH, α-tocopherol (vitamin E), and ascorbic acid (vitamin C). Regional variations in the expression of proteins involved in cytoprotective processes are likely to be another factor in the differences of susceptibility of each nephron segment to toxicity from xenobiotics. For example, compared to the distal tubule (DT), the PT has much higher glutathione reductase and glutathione peroxidase activity and GSH uptake is higher [42]. The potential consequences of these particular differences were demonstrated when isolated rat PT and DT cells were exposed to tert-butyl hydroperoxide (tBH), a model oxidant. A similar percentage of GSH was oxidized in PT and DT cells, but DT cells were more susceptible to cytotoxicity from tBH [42].

3.3 The presence of unique cell types and target molecules and the response to injury in the kidney

Exposure to a reactive metabolite is not a sufficient determining factor by itself to demonstrate organ-specific toxicity. Predisposition to toxicity is also tied to the molecular effects of the reactive metabolite on normal organ function. All organs contain populations of specialized cells that have unique biochemical pathways and enzymes necessary for the organ’s function. If these critical cells or biochemical pathways are specifically targeted by a reactive metabolite, organ-specific toxicity can result. For example, the different segments of the PT exhibit differences in levels of enzymes involved in energy metabolism, cellular transport, and xenobiotic metabolism, an important reason why different segments of the PT exhibit varied susceptibility to toxicants.

In addition, the ultimate fate of an organ after exposure to a toxicant is highly dependent on the type of response that is elicited after injury. The relative contributions of pro-death and pro-survival processes determine whether the organ will survive a toxic insult intact or will be damaged irreversibly. Cells that are exposed to a toxin and sensitive to its toxic effects can undergo cell death via necrosis or apoptosis. Induction of a regenerative phase where lost cells are replaced with new ones favors the survival of the organ. Exposure of renal cells to a toxicant can result in the induction of stress response signaling pathways and an induction of transcription factors (e.g. c-fos, c-jun), and other stress-induced genes (e.g. heat shock proteins, clusterin) [43]. This initiates a signal cascade that can lead to induction of cell death via apoptosis or necrosis, or repair through regenerative processes. Adaptive processes initiated after injury lead to compensatory changes in filtration, renal mass, and metabolism that result in short term restoration of kidney function. However, after injury and loss of nephrons, alterations of existing cell function and metabolism as well as the induction of hypertrophy and hyperplasia-associated tubule and glomeruli growth can lead to sclerosis and chronic renal failure [44].

These factors provide more support for a model wherein reactive metabolites in the circulation can affect the kidney but not the liver, despite the presence of similar drug-metabolizing enzymes that can be involved in bioactivation. The liver has great regenerative abilities, contains the highest concentration of cytoprotective molecules in the body, and has a large reserve of functional cells and a homogenous structure that allows it to compensate for any damage inflicted in specific areas without resulting in major effects on the organism. On the other hand, the structure of the kidney is highly organized and has a larger number of distinct cell types. As a result, drug-induced toxicity that affects a small population of renal cells could have a disproportionately large effect.

4. Case Study: hepatic bioactivation of cysteine S-conjugates and nephrotoxicity of trichloroethylene

Trichloroethylene (TCE) is an organic solvent that has been used in industrial applications, such as a metal degreaser. TCE is a common air and groundwater contaminant that can cause nephrotoxicity in humans [45-47]. A study that reported on a 17 year old male who ingested a large amount of TCE in a suicide attempt demonstrates that a single oral dose of TCE has the potential to cause acute nephrotoxicity [46].

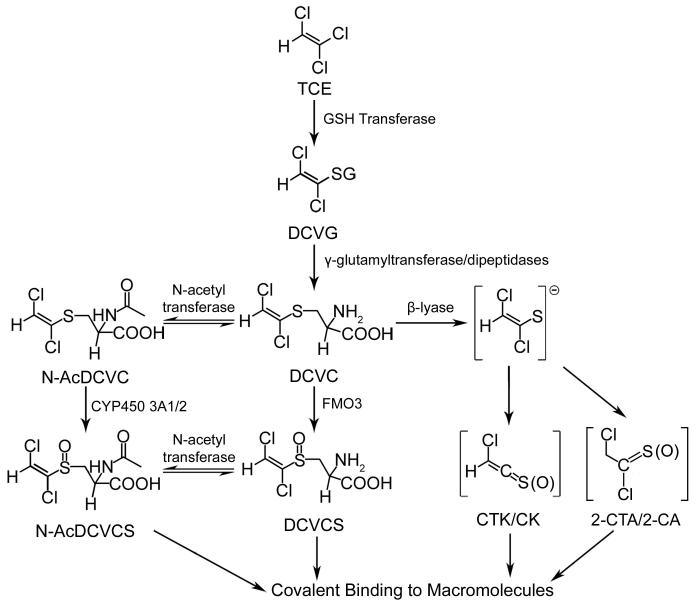

Metabolism of TCE is required for the manifestation of toxicity. TCE can be metabolized through two different pathways. One pathway involves oxidation by CYPs, resulting in the formation of metabolites which are associated with liver toxicity [48-50]. The other pathway involves GSH conjugation (Figure 1); the metabolites generated in this pathway are associated with the nephrotoxic effects of TCE exposure [51-54].

Figure 1.

Glutathione-dependant metabolism of trichloroethylene (TCE). Glutathione S-transferase (GST), S-(1,2-dichlorovinyl)glutathione (DCVG), γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT), S-(1,2-dichlorovinyl)-L-cysteine (DCVC), flavin-containing monooxygenase 3 (FMO3), S-(1,2-dichlorovinyl)-L-cysteine sulfoxide (DCVCS), N-acetyl-S-(1,2-dichlorovinyl)-L-cysteine (N-AcDCVC), Cytochrome P450 3A1/2 (CYP3A1/2), N-acetyl-S-(1,2-dichlorovinyl)-L-cysteine sulfoxide (N-AcDCVCS), chlorothioketene (CTK) and its hydrolysis product chloroketene (CK), and 2-chlorothionoacetyl chloride (2-CTA) and its hydrolysis product 2-chloroacetyl chloride (2-CA). Adapted from [92] with permission of the American Chemical Society.

In this pathway, TCE is first conjugated to GSH in the liver to form S-(1,2-dichlorovinyl)glutathione (DCVG). DCVG has been detected for 12 h in the blood of human volunteers exposed to TCE [55]. Cysteinyl-glycine dipeptidases and gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) located in the bile canalicular membrane of hepatocytes, the luminal membrane of the bile duct epithelium, the intestinal lumen, and kidney cells cleave off the gamma-glutamyl and glycine residues to form the cysteine S-conjugate, S-(1,2-dichlorovinyl)-L-cysteine (DCVC). DCVC can be N-acetylated by N-acetyl transferases to form the mercapturic acid, N-acetyl DCVC (N-AcDCVC). N-AcDCVC has been detected for 48 h in the urine of humans exposed for 6 h to TCE [56]. DCVC can be bioactivated through β-elimination by cysteine conjugate β-lyases to form chlorothioketene (CTK) and 2-chlorothionoacetyl chloride (2-CTA); these reactive electrophiles can be readily hydrolyzed to chloroketene (CK) and 2-chloroacetyl chloride (2-CA), respectively. All four compounds have the ability to modify cellular proteins [57-60].

It is widely considered that the reactive metabolites formed by β-elimination are responsible for the nephrotoxicity caused by TCE, as β-elimination is known to occur in kidney cells. However, a number of observations suggest that there could be other metabolic processes that also contribute to nephrotoxicity. Aminooxyacetic acid (AOAA), a potent inhibitor of β-lyase did not completely protect isolated kidney cells from the cytotoxicity of DCVC [52]. AOAA has a Ki of 0.1 μM in kidney mitochondria [51] and 2 μM in isolated kidney cells [52]. Therefore, even though the study demonstrating AOAA partial protection from DCVC toxicity only examined a single concentration of AOAA (0.1 mM), it was far in excess of the Ki and should have been sufficient to completely protect cells from β-lyase derived metabolites. In addition, AOAA pretreatment of rats before dosing with the similar nephrotoxic cysteine s-conjugate S-(1,2,2-trichlorovinyl)-L-cysteine (TCVC) lead to an increase in toxicity, suggesting that by blocking the β-lyase pathway, it is possible that AOAA treatment caused greater TCVC bioactivation to S-(1,2,2-trichlorovinyl)-L-cysteine sulfoxide (TCVCS), a much more potent nephrotoxin than TCVC [61].The S3 segment of the proximal tubule in the rat nephron is the most susceptible to DCVC-induced toxicity, but proximal tubule susceptibility to toxicity does not always correlate with localization of β-lyase activity [62]. In addition, total β-lyase activity in human kidney is lower compared to rat kidney [63]. Collectively, these factors led to the questioning of the hypothesis that β-lyase derived reactive metabolites are the only contributors to DCVC nephrotoxicity [64].

In an effort to identify other metabolites of DCVC and characterize their potential role in nephrotoxicity, studies have investigated alternative metabolic pathways for DCVC, the ability of the metabolites generated to move through the circulation, and their nephrotoxic potential. The results from these studies show how two metabolites of DCVC are likely formed primarily in the liver, enter the circulation, and translocate to the kidney to play a role in DCVC-induced nephrotoxicity.

4.1 Alternative metabolism of DCVC

4.1.1 Flavin-containing monooxygenases and the formation of S-(1,2-dichlorovinyl)-L-cysteine sulfoxide (DCVCS)

Given the previously mentioned factors that suggested that metabolites other than those formed by β elimination could also contribute to the TCE-associated toxicity, an alternative pathway involving S-oxidation was considered, as studies have demonstrated that cysteine S-conjugates can undergo S-oxidation to yield the corresponding sulfoxides [65-67]. Determination of whether the putative sulfoxide metabolite of DCVC, DCVCS, could be generated in vivo and understanding the metabolic pathway responsible for formation of this metabolite would provide information about the significance of DCVCS in TCE-induced nephrotoxicity.

CYPs, FMOs, and prostaglandin synthetase are known to catalyze sulfoxide formation from sulfides. Using S-benzyl-cysteine as a substrate, sulfoxidation of cysteine S-conjugates was determined to be FMO-mediated [68]. DCVC was found to be a competitive inhibitor of S-benzyl-cysteine sulfoxidation, suggesting that DCVC was itself a potential substrate for FMOs [68].

FMOs are microsomal enzymes that can catalyze the oxidation of sulfur, selenium, and nitrogen containing compounds. There are 5 known FMO isoforms present in mammalian tissues and FMO expression differs among species, sex, tissue, and age, suggesting that differential localization of expression could be relevant to our understanding of DCVCS disposition and toxicity. Immunohistochemical studies have demonstrated that FMOs are zonally expressed [69]. In rat kidney, FMO1, 3, and 4 are localized in the proximal and distal tubule of the rat nephron, areas known to contain other xenobiotic metabolizing enzymes. In rat liver, FMO1 and 3 are localized in the perivenous region, similar to CYPs, while FMO4 is expressed in the periportal region. Regulation of FMO expression is relatively unknown, although it is known to be affected by endogenous compounds like testosterone and estrogen, as well as exogenous compounds like 2,3,7,8,-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin and 3-methylcholanthrene [70-72].

Initially, incubations of DCVC with rabbit liver microsomes or cDNA-expressed rabbit FMO isoforms were carried out to determine which isoform, if any, can metabolize DCVC. In these studies, DCVC was found to only be a substrate for rabbit FMO3 [73]. With human FMOs, DCVC was demonstrated to be a substrate for human cDNA-expressed FMO3 but was not a substrate for FMO1, FMO4, or FMO5 [74]. Furthermore, DCVCS formation was detectable when DCVC was incubated with human liver microsomes but not human kidney microsomes [74]. DCVCS was detected by HPLC as a pair of diastereomers, and the stereoselectivities of S-oxidation of DCVC by human liver microsomes and cDNA-expressed human FMO3 were 80% and 100% diastereomer 2, respectively [74].

Understanding the difference in metabolizing enzyme expression between organs provides insight into where the reactive metabolites they form are likely to be generated in the organism. In the case of FMO3, enzyme expression is greater in kidney than in liver in rats, whereas FMO3 levels are lower in human kidney compared to liver (Table 2) [74-76]. Interestingly, FMO levels also vary between individuals; in human liver, there is up to a 20-fold variation in expression [75], and in human kidney, a 5- to 6-fold variation exists.

Table 2.

FMO3 expression in human liver and kidney.

These results demonstrate that, in humans, DCVCS could be formed in the liver. Because DCVCS was later shown to be a selective nephrotoxicant, these results suggest that DCVCS may translocate from the liver to the kidney to cause nephrotoxicity. Thus, with regards to TCE-induced nephrotoxicity, the role of the liver in DCVCS formation may have to be considered when describing the mechanism of DCVC or TCE nephrotoxicity. Furthermore, the interindividual variability in FMO3 expression levels could be a determinant of the variability of the nephrotoxic response after human exposure to TCE.

4.1.2 Cytochrome P450s and the formation of N-acetyl-S-(1,2-dichlorovinyl)-L-cysteine sulfoxide (N-AcDCVCS)

The formation of N-AcDCVC is generally considered to be a detoxification pathway by making DCVC more easily excreted. A novel metabolic pathway was discovered where N-acetyl-S-(1,2,3,4,4-pentachlorobuta-1,3-dienyl)-L-cysteine, a mercapturate derived from the chlorinated alkene hexachlorobutadiene, was metabolized to a sulfoxide only in male rats [77]. As a result, studies were carried out investigating the possibility that N-AcDCVC could be similarly metabolized to its sulfoxide, N-AcDCVCS.

Incubations of N-AcDCVC with male and female rat liver microsomes, as well as with male rat kidney microsomes, demonstrated that formation of N-AcDCVCS was only detectable in male rat liver microsomes [78], suggesting that the monooxygenase that could be responsible for this reaction might be CYP3A2, since it is expressed in adult male rats but not adult female rats. S-Oxidation of N-AcDCVCS by liver microsomal monooxygenases exhibits little stereoselectivity. Using troleandomycin, an inhibitor of the cytochrome 3A family, a significant reduction in the sulfoxide formation was observed, suggesting that these enzymes play a significant role in N-AcDCVCS formation. Further evidence of CYP3A involvement was provided by showing that liver microsomes from rats treated with inducers of CYP3A1/2 (i.e. phenobarbital and dexamethasone) increased sulfoxide formation in both male and female rats. Heat inactivation, which abolishes FMO activity while leaving CYP450 activity intact, did not affect sulfoxide formation. In addition, N-octylamine, an activator of FMO activity that also inhibits CYP450 activity, reduced sulfoxide formation. Collectively, these results implicate CYP3A1/2 rather than FMO as the likely enzyme catalyzing the formation of N-AcDCVCS.

Members of the CYP3A family are monooxygenases involved in the oxidation of 6-β-hydroxylation of testosterone as well as a large number of drugs. CYP3A2 is a member of this protein family expressed in the rat. CYP3A2 expression varies by sex and age; the protein is constitutively expressed in immature female and male rats, but is only expressed in the adult male rat [79]. Furthermore, CYP3A2 expression is limited to the liver, mainly in the centrilobular zone [80].

In adult humans, at least two CYP3A isoforms exist. CYP3A4 is predominantly found in the liver, where it represents a large proportion of total CYP protein [35,36]. In addition, CYP3A4 is found in the kidney, although the expression levels are lower than in the liver [37,38]. In the kidney, CYP3A4 is mainly localized to the collecting ducts and is only detectable in 30% of kidney samples [37,38]. CYP3A5 is the predominant isoform in the kidney, whereas it only represents a small portion of CYP3As in the liver [81]. There is significant interindividual variability in CYP3A expression due to genetic and environmental factors, as human in vivo studies have indicated that expression can vary as much as five-fold [36].

Based on the greater total CYP3A levels in the liver, N-AcDCVCS is likely to be formed in the liver in humans, similar to rats. Similar to FMOs, the interindividual variability in CYP3A expression suggests that enzyme expression levels could play a role in determining the nephrotoxic response after an individual’s exposure to TCE.

4.2 DCVCS and N-AcDCVCS translocation from liver to the circulation

The findings that humans have low FMO3, CYP3A, and β-lyase levels in their kidneys suggests that either humans are not sensitive to DCVC-induced nephrotoxicity or that the toxic metabolites are formed extra-renally and translocate to the site of toxicity. As mentioned previously, other metabolites of the GSH-conjugation pathway of TCE metabolism (DCVG, N-AcDCVC; Figure 1) have been detected in the blood and urine of humans exposed to TCE. More recently, the presence of circulating DCVCS and N-AcDCVCS in animals given DCVC has been established [60].

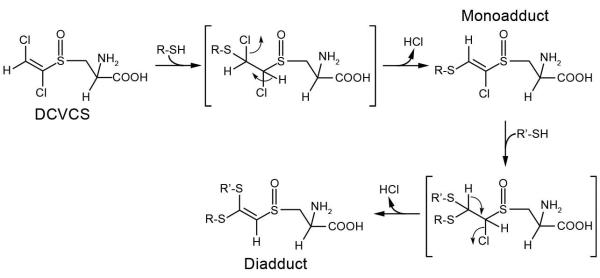

DCVCS contains an α,β-unsaturated moiety that allows it to act as Michael acceptor in addition-elimination reactions with the thiol group of Cys, NAC, and GSH to form adducts [60,82-84]. The presence of two chiral centers, at the sulfoxide moiety and the α-carbon of the cysteine moiety, allows DCVCS to be formed as a pair of diastereomers, which have been resolved by HPLC. The diastereomers exhibit a difference in reactivity toward nucleophiles that is likely due to the configuration of the sulfoxide group. For example, the half-lives of the DCVCS diastereomers in the presence of NAC were 13.8 min and 9.4 min for diastereomers 1 and 2, respectively [82]. Nucleophilic addition is less hindered if the sulfoxide is aimed anti to the double bond. Since N-AcDCVCS also contains the α,β-unsaturated moiety, it also can act as a Michael acceptor and react with thiol-containing molecules.

The mechanism of nucleophilic addition involves Michael addition of the sulfhydryl-containing nucleophile followed by elimination of HCl (Figure 2). When NAC and DCVCS were incubated together, four new products were detected, and LC/MS analysis demonstrated that these products were three mono-NAC DCVCS adducts and one di-NAC DCVCS cross-link [82]. Two of these monoadducts are diastereomers of the adduct that has the proton at the terminal vinylic carbon, while the third monoadduct was a minor product that has a proton adjacent to the sulfoxide moiety. This third monoadduct is likely the result of the less favorable elimination of HCl through the loss of the terminal vinylic carbon’s proton and the chlorine atom from the carbon adjacent to the sulfoxide. These in vitro results demonstrated that when searching for evidence of DCVCS in circulation, the metabolite might be found incorporated into adducts and cross-links with sulfhydryl-containing nucleophiles.

Figure 2.

The reaction between DCVCS and thiol-containing molecules results in the formation of adducts and cross-links. DCVCS contains an α,β-unsaturated moiety allowing it to act as a Michael acceptor, forming a covalent bond with the thiol and and subsequently losing HCl by trans-elimination. Adapted from [82] with permission of the American Chemical Society.

Detection of metabolite-derived hemoglobin adducts was the strategy used to provide evidence for translocation of DCVCS from liver cells into the circulation. This strategy was selected because it could also provide useful biomarkers of exposure to TCE. Hemoglobin contains a number of sulfhydryl groups that could be susceptible to adduction by DCVCS.

DCVCS-derived hemoglobin adducts were detectable in rat erythrocytes treated in vitro and male Sprague-Dawley rats treated in vivo with DCVCS [83]. Going one step further, male rats were given a subacute dose (3 or 30 μmol/kg b.w.) of DCVC daily for five days [60]. These doses were chosen based on the levels of DCVG detected in the blood of human volunteers after a 4 h inhalation exposure to TCE [55]. After hemoglobin was isolated by precipitation, trypsin digests of hemoglobin samples were analyzed by tandem mass spectrometry. Analysis for adducts and cross-links was carried out by searching for shifts in peptide peak masses that correspond to the addition of a various DCVCS-derived metabolites (for an adduct) or metabolites plus another peptide (for a cross-link). DCVCS-related metabolites that were considered were DCVCS, DCVCS-GSH, N-AcDCVCS, and N-AcDCVCS-GSH.

Hemoglobin adducts were detected in rats given the subacute doses (3 or 30 μmol/kg b.w.) (Table 3). Similar adducts were detected in rats given a single nephrotoxic dose of DCVC (460 μmol/kg b.w.; data not shown). All five cysteine residues in rat hemoglobin were susceptible to modification by DCVCS-derived metabolites.

Table 3.

S-oxidase derived adducts detected in rats dosed with 3 or 30 μmol/kg b.w. DCVC daily for 5 days. Adapted from [60] with permission of the American Chemical Society.

| Type of Adduct |

Metabolite | Chains Modified |

Cys Modified | Treatment Groupa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monoadduct | N-AcDCVCS | α1 | Cys13 | HS |

| N-AcDCVCS-GSH | β | Cys125 | HS | |

| Cross-link | DCVCS | α2 + α | Cys13 + Cys13 | LS |

| N-AcDCVCS | α2 + α | Cys13 + Cys104/111 | LS | |

| N-AcDCVCS | β + β | Cys93 + Cys125 | LS | |

| N-AcDCVCS | β + β | Cys125 + Cys125 | LS |

LS - Low subacute dose: 3 μmol/kg b.w. daily for 5 d

HS – High subacute dose: 30 μmol/kg b.w. daily for 5 d

Furthermore, cross-links tended to be more prevalent than monoadducts, consistent with the results from studies of rats dosed with DCVCS.

Similar to the rats dosed with DCVCS, N-AcDCVCS-derived adducts were detected in the rats dosed with DCVC, suggesting that N-acetylation of DCVCS plays an important role in DCVC metabolism. Since N-AcDCVCS-derived adducts were detected in rats dosed with DCVCS, this suggests that N-acetylation by N-acetyltransferases after bioactivation of DCVC to DCVCS can occur in rats. Another possible source of N-AcDCVCS could be the aforementioned S-oxidation of N-AcDCVC by CYP3A2.

Given that no S-oxidase activity was detectable in red blood cells [85], the results from these studies provide in vivo evidence for bioactivation of DCVC to DCVCS and formation of N-AcDCVCS outside of the circulation. The high reactivity of DCVCS and N-AcDCVCS toward sulfhydryl groups suggests that when excreted from the liver into the circulation, a fraction is likely to be present in the form of a GSH conjugate, either due to spontaneous GSH conjugation or GSH S-transferase-mediated conjugation. In the circulation, the GSH conjugates also have the ability to react with hemoglobin, indicated by the N-AcDCVCS-GSH-hemoglobin cross-link that was identified in rats given the 30 μmol DCVC subacute dose. However, as demonstrated with other GSH conjugates of Michael acceptors such as trans-4-phenyl-3-buten-2-one and 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal, retro Michael addition reactions could occur spontaneously or through catalysis by GSH S-transferases to free DCVCS to react with subsequent nucleophiles [86,87].

4.3 Circulating reactive metabolite toxicity

Although β-lyase derived metabolites are widely considered to be responsible for nephrotoxicity of DCVC, there existed evidence that pointed to the additional involvement of other metabolites of DCVC. Metabolism studies identified two other metabolites, DCVCS and N-AcDCVCS, which are formed in the liver by FMO3 and CYP3A2, respectively. Despite the fact that these compounds are direct acting reactive electrophiles that can act as Michael acceptors to react with thiol-containing molecules, both compounds were detected in the circulation of rats dosed with DCVC in the form of hemoglobin adducts, suggesting that these compounds are excreted from the liver and could translocate to the kidney. In order to determine whether these metabolites can contribute to DCVC-induced nephrotoxicity, it was important to establish their nephrotoxic potential.

4.3.1 Nephrotoxicity and cytotoxicity of DCVCS

In vivo studies of rats dosed with DCVC or DCVCS demonstrated that, on an equimolar basis, DCVCS is a more potent nephrotoxicant than DCVC [64]. In rats dosed with DCVCS, increased blood urea nitrogen levels, anuria, more severe PT necrosis, and depletion of renal GSH were observed compared to rats dosed with DCVC [64,83].

In vitro studies have generally focused on primary cultures of PT cells as a model system, since the PT appears to be the major target of DCVC-induced toxicity in the kidney [52]. Isolated rat and human PT cells exposed to DCVC or DCVCS undergo cell death in a dose-and time-dependent manner [88]. The type of cell death appears to correlate with mitochondrial dysfunction, as increases in DCVC or DCVCS concentrations lead to an increase in dysfunction and a decrease in competency to undergo apoptosis. DCVC has been shown to inhibit mitochondrial Ca2+ sequestration in isolated rat PT cells, which is associated with an increase membrane permeability and inability to generate a membrane potential [52]. In addition, both DCVC and DCVCS cause inhibition of succinate-dependent state 3 respiration and decreases in ATP levels in isolated human PT cells [88,89]. Isolated human PT cells exposed to DCVC and DCVCS also exhibit GSH depletion, however DCVCS causes greater depletion than DCVC, which is most likely due to the ability of DCVCS to form GSH adducts [88]. The GSH depletion caused by DCVC is most likely due to oxidative stress [52, 90].

Other in vitro studies provided evidence that physiological, hemodynamic, and pharmacokinetic factors play a significant role in the nephrotoxicity induced by DCVCS. The liver possesses significant S-oxidase activity and isolated hepatocytes are similarly susceptible to DCVC cytotoxicity as isolated kidney cells [91], however, no hepatotoxicity is observed in rats dosed with DCVC or DCVCS [64,90]. DCVCS also causes cytotoxicity in primary cultures of rat renal DT and PT cells [64]. Although DT cells were found to be more susceptible to DCVCS-induced cytotoxicity in vitro, in vivo necrotic lesions are observed in the PT, while the DT is only mildly affected. In conjunction with the previously described metabolism data, this suggests that although DCVCS is formed in liver, other factors play a role in determining where damage is caused.

4.3.2 Role of protein covalent modifications by DCVCS in nephrotoxicity

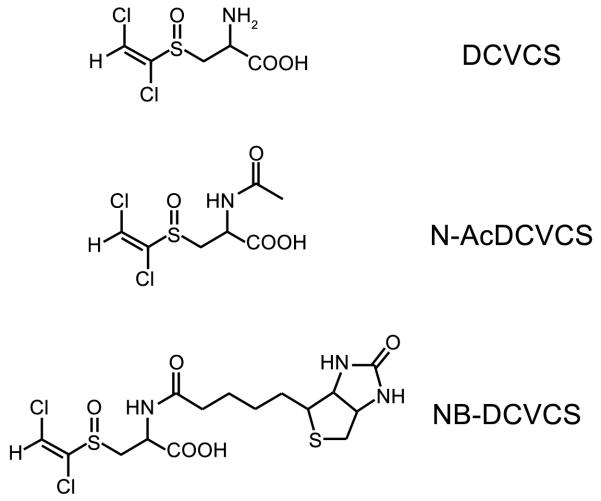

As mentioned before, unlike DCVC, DCVCS can act as a Michael acceptor to react with sulfhydryl-containing molecules to form adducts. Covalent modification of proteins by reactive electrophiles can cause toxicity if modification results in an alteration of protein function or signal transduction. In order to determine what proteins are targeted for modification by DCVCS and whether there is a connection between the ability to covalently modify macromolecules and DCVCS nephrotoxicity, we recently developed a biotin-tagged form of DCVCS, N-biotinyl DCVCS (NB-DCVCS) (Figure 3) [92].

Figure 3.

Structures of DCVCS, N-AcDCVCS and N-biotinyl-DCVCS (NB-DCVCS).

Biotin-tagged probes derived from thiol-reactive electrophiles have been used in other studies to identify potential protein targets for modification [93,94]. In addition, the utility of a DCVCS-derived biotin-tagged probe is great as the biotin tag can possibly be used for immunohistochemical studies to determine cellular and tissue localization, ELISA-based quantification of adducts in tissues of animals dosed with the probe, and enrichment of modified proteins for mass spectrometry-based identification of targets.

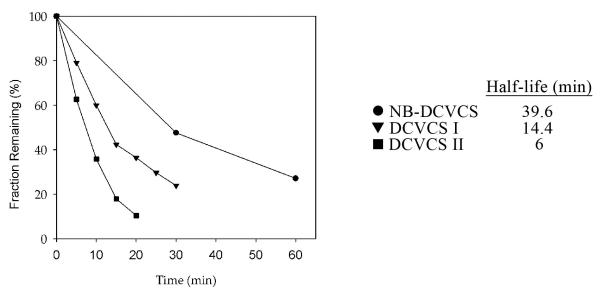

Addition of the biotin tag to the amino group of DCVCS was shown to not interfere with the ability of the compound to react with thiol groups, as NB-DCVCS and DCVCS had half-lives of the same order of magnitude in the presence of GSH (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

NB-DCVCS (●) and DCVCS diastereomers I (▼) and II (■) exhibit half-lives in the same order of magnitude in the presence of GSH. (3:10 molar ratio of sulfoxide to GSH incubated at pH 7.4, 37°C). Adapted from [92] with permission of the American Chemical Society.

The reaction between NB-DCVCS and GSH resulted in the formation of four products, all of which were identified as mono-GSH NB-DCVCS adducts by MS. NB-DCVCS was shown to covalently modify GSH reductase (GRd) and mitochondrial malate dehydrogenase (MDH), model proteins chosen because they have differential cellular localization, multiple sulfhydryl groups, and are potentially relevant to the mechanism of DCVC toxicity. GRd activity was reduced in rat renal PT cells treated with DCVC [95] and MDH activity was reduced in rat liver mitochondria in the presence of DCVC [96]. Further investigations are being carried out in order to determine whether covalent modification of these proteins affects protein function.

When NB-DCVCS was incubated with rat kidney cytosol followed by immunoblotting, multiple bands of different molecular weights were detected in a concentration-dependent manner. This suggests that multiple kidney proteins are sensitive to covalent modification and that target protein susceptibility to modification varies as different bands begin to be detectable at different concentrations of NB-DCVCS. In addition, when rat kidney cytosol is first incubated with DCVCS before incubating with NB-DCVCS and immunoblotting, the signal was reduced proportional to the DCVCS concentration in the initial incubation. This suggests that DCVCS and NB-DCVCS share many of the same targets. Collectively, these results suggested that NB-DCVCS can be used as a probe to investigate the covalent modification of proteins and its effects in vitro.

DCVCS and NB-DCVCS stability in rat blood and plasma in vitro was characterized to determine whether NB-DCVCS has sufficient stability in these media to potentially reach the kidney intact. NB-DCVCS exhibited greater stability than DCVCS in both media. These results suggest that NB-DCVCS would likely be useful in in vivo applications, although further studies into the disposition and toxicity of NB-DCVCS in the whole organism are required before use of NB-DCVCS as a model for DCVCS in vivo can be confirmed.

4.3.3 N-AcDCVCS cytotoxicity

Generally, little is known about the toxicity of N-AcDCVCS. The nephrotoxicity of N-AcDCVCS, a metabolite likely formed in the liver, has yet to be characterized. N-AcDCVC and N-AcDCVCS are both cytotoxic to isolated rat renal epithelial cells in vitro [78]. Similar to results with DCVC and DCVCS, the cytotoxicity of N-AcDCVCS was greater than that of N-AcDCVC, suggesting that the metabolism of N-AcDCVC to N-AcDCVCS is a bioactivation mechanism. Cytotoxicity of N-AcDCVC was significantly reduced by treating cells with AOAA, whereas the inhibitor had no effect on the toxicity of N-AcDCVCS. This is consistent with the results of similar studies with DCVC and DCVCS, and gives support to the notion that the ability of N-AcDCVCS to react with thiols is a likely important factor in its toxicity.

4.4. Assessing possible intervention strategies

Due to DCVCS formation in liver and translocation to kidney, strategies to reduce DCVCS nephrotoxicity could include inhibiting formation of the reactive metabolites in the liver, trapping the reactive metabolites in the circulation, and/or blocking the renal uptake of the reactive metabolites. The drug methimazole, commonly used to treat hyperthyroidism, was found to provide complete protection against nephrotoxicity when rats were given methimazole (20 mg/kg) 30 min prior to injection with a nephrotoxic dose of DCVC (100 mg/kg) [97]. In addition to its antioxidant properties, methimazole is a competitive inhibitor of FMOs [68], suggesting that its protective effects against DCVC-induced nephrotoxicity could in part be due to inhibition of DCVC bioactivation to DCVCS.

Another strategy to prevent exposure of the target organ to circulating reactive electrophiles could be accomplished through trapping with nucleophilic agents. As mentioned earlier, many reactive intermediates are detected as chemically stable adducts of endogenous thiols such as NAC. The increase in circulating concentrations of NAC could lead to depletion of available circulating reactive metabolites before they reach the target organ. Minimizing target organ exposure to circulating reactive electrophiles may also be accomplished by limiting uptake of reactive electrophiles. Blocking OAT1 with probenecid or p-aminohippuric acid has been shown to protect against the nephrotoxicity of cisplatin and DCVC [51,98].

Collectively, the investigations that comprise this case study suggest that understanding the role of circulating reactive metabolites in extrahepatic toxicity can lead to development of effective methods to reduce toxicity. It is important to note that the development of therapeutic approaches against a specific circulating drug-derived reactive metabolite would require optimization for the liver enzymes involved, characteristics of the reactive metabolite electrophilicity, and the mechanism of translocation of the reactive metabolite into extrahepatic tissues.

5. Conclusions

Reactive metabolites often play a role in drug-induced extrahepatic toxicity. Although many toxic metabolites are believed to cause toxicity in the organ in which they are generated, some have demonstrated the ability to enter the circulation, leading to the exposure of organs distal to the site of formation. Various tissue-related physiological and biochemical factors play a role in determining which organs are susceptible to toxicity induced by circulating reactive metabolites. Identifying metabolites of compounds that utilize this process to cause toxicity is possible by investigating the metabolism, translocation, and toxicity of the compounds. An example of a metabolite that falls into this category is DCVCS, a selective nephrotoxicant formed from the bioactivation of the environmental contaminant TCE. DCVCS is formed by FMO3, which in humans is expressed in high levels in liver. Detection of DCVCS-derived hemoglobin adducts in the circulation of rats treated with its precursor, DCVC, at concentrations relevant to DCVG concentrations observed in humans exposed to TCE demonstrates that DCVCS enters the circulation after formation and can translocate to other organs. Collectively, the findings of these studies provide strong evidence that DCVCS is a metabolite that causes extrahepatic toxicity after being released into the circulation. The ability of DCVCS to covalently modify sulfhydryl-containing molecules likely plays a role in its ability to cause toxicity. Future studies determining the proteins targeted by DCVCS for covalent modification and whether modification of targets results in alterations in function or signal transduction could provide further insight into the mechanism by which this compound causes nephrotoxicity. In addition, some general intervention strategies to reduce the toxicity caused by reactive metabolites include the provision or induction of protective molecules and mechanisms or the induction of repair and regenerative processes in the target tissue. However, due to the fact that DCVCS requires translocation from the site of formation to its target organ, the identification of other methods to reduce DCVCS nephrotoxicity by intercepting the compound prior to reaching the kidney, such as inhibition of its formation in the liver, trapping the reactive metabolite with nucleophiles before it can enter the kidney, and blocking its uptake from the circulation by kidney cells would be of great interest.

6. Expert opinion

A large body of work has examined the role of reactive metabolites in drug-induced extrahepatic toxicity. The balance between the chemical stability and reactivity of the metabolite is believed to be a major determining factor as to whether toxicity is caused where the reactive metabolite is formed or in other organs via transport through the systemic circulation. The prevailing opinion has been that highly chemically reactive metabolites with short half-lives are more likely to cause toxicity within the target organ if they are generated in situ while moderately chemically reactive metabolites with longer half-lives can be transported through the circulation to their target organ. An investigative strategy that integrates studies on the formation, presence in the circulation, and the relative potency of the various metabolites in causing toxicity can be carried out to determine whether the ability of reactive metabolites to translocate is relevant to the metabolite’s mechanism of toxicity.

There are a number of toxicological and clinical implications to be considered when examining reactive metabolites that translocate to their target organ. Interindividual variations in drug metabolizing enzyme expression in liver could play a role in determining the magnitude of extrahepatic toxicity for some compounds. As a result, subsets of the population could be disproportionately susceptible to a reactive electrophile. A thorough understanding of variability factors in expression when determining likelihood of drug-induced extrahepatic toxicity can be extremely important.

The overall significance of the type of covalent modification (monoadduct or cross-link) in reactive electrophile extrahepatic toxicity is at the present unknown. DCVCS- and N-AcDCVCS-derived hemoglobin cross-link formation was more prevalent at lower doses than monoadducts, but the relative contributions of monoadduct and cross-link formation in DCVCS-induced nephrotoxicity has yet to be determined. The increased nephrotoxic potency of DCVCS compared to DCVC may be associated with cross-link formation as cross-link formation is more likely to change the tertiary structure of the target protein and inhibit its function. In addition, damage due to protein cross-link formation could be harder to repair than damage caused by monoadducts.

The ability of circulating reactive electrophiles to cause extrahepatic toxicity suggests that dietary factors that promote higher non-protein thiol (i.e. Cys, NAC, and GSH) concentrations in the blood could be protective against these types of metabolites. In addition, factors and behaviors that promote GSH oxidation could have enhancing effects on the toxicity caused by circulating reactive metabolites. The increased complexity in the mechanism of toxicity for these compounds allows for additional intervention strategies to be considered. Development of therapeutic strategies to prevent exposure of the target organ could have great value in preventing drug-induced extrahepatic toxicity that is mediated by circulating reactive electrophiles. Clearly, characterizing the chemical properties of a toxic metabolite are insufficient; to fully assess the potential damage that can be done, one must develop a fuller understanding of the formation, disposition, reactivity, and selectivity of all known or potential metabolites.

Article Highlights.

Many adverse drug reactions are initiated by the formation of reactive electrophilic metabolites in the liver.

Whereas metabolites with high chemical reactivity are likely to cause damage within the tissue where they are generated, reactive metabolites with moderate chemical reactivity have the potential to enter the circulation, either intact or in equilibrium with a relatively more stable adduct, leading to possible exposure of extrahepatic tissues to the reactive metabolites, which can directly initiate toxicity.

Several metabolite and organ-specific factors play a role in determining a target organ’s susceptibility to toxicity induced by circulating reactive metabolites.

A research strategy similar to the one described herein that characterizes the formation, translocation, and nephrotoxicity of two reactive electrophilic metabolites of trichloroethylene could be used to investigate the mechanisms of extrahepatic toxicity.

Identification of circulating reactive metabolites that play a role in drug-induced extrahepatic toxicity could lead to development of effective intervention methods to reduce or block toxicity. Possible intervention methods include inhibition of formation of reactive metabolites in the liver, trapping reactive metabolites in the circulation, and limiting reactive metabolite uptake into the extrahepatic target organ.

Acknowledgments

The authors are supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health: R01 NIDDK 044295 and T32 ES 007015

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest

References

- 1.Einarson TR. Drug-related hospital admissions. Ann Pharmacother. 1993;27:832–40. doi: 10.1177/106002809302700702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lazarou J, Pomeranz BH, Corey PN. Incidence of adverse drug reactions in hospitalized patients: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. JAMA. 1998;279:1200–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.15.1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lasser KE, Allen PD, Woolhandler SJ, et al. Timing of new black box warnings and withdrawals for prescription medications. JAMA. 2002;287:2215–20. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.17.2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brock N, Hohorst HJ. Metabolism of cyclophosphamide. Cancer. 1967;20:900–4. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(1967)20:5<900::aid-cncr2820200552>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li F, Patterson AD, Ho fer CC, et al. Comparative metabolism of cyclophosphamide and ifosfamide in the mouse using UPLC-ESI-QTOFMS-based metabolomics. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010;80:1063–74. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson JR, Harris JW. Hematologic side-effects of dapsone. Ohio State Med J. 1977;73:557–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Uetrecht JP. Reactivity and possible significance of hydroxylamine and nitroso metabolites of procainamide. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1985;232:420–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kalgutkar AS, Gardner I, Obach RS, et al. A comprehensive listing of bioactivation pathways of organic functional groups. Curr Drug Metab. 2005;6:161–225. doi: 10.2174/1389200054021799. * Extensive review of the type of reactive intermediates that can be formed by the action of drug metabolizing enzymes on specific functional groups.

- 9.Yunis AA, Miller AM, Salem Z, et al. Nitroso-chloramphenicol: possible mediator in chloramphenicol-induced aplastic anemia. J Lab Clin Med. 1980;96:36–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park JY, Kim KA, Kim SL. Chloramphenicol is a potent inhibitor of cytochrome P450 isoforms CYP2C19 and CYP3A4 in human liver microsomes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:3464–9. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.11.3464-3469.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prescott LF, Proudfoot AT, Cregeen RJ. Paracetamol-induced acute renal failure in the absence of fulminant liver damage. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1982;284:421–2. doi: 10.1136/bmj.284.6313.421-d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dahlin DC, Miwa GT, Lu AY, Nelson SD. N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine: a cytochrome P-450-mediated oxidation product of acetaminophen. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984;81:1327–31. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.5.1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gunness P, Aleksa K, Bend J, Koren G. Acyclovir-induced nephrotoxicity: the role of the acyclovir aldehyde metabolite. Transl Res. 2011;158:290–301. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nissim I, Horyn O, Daikhin Y, et al. Ifosfamide-induced nephrotoxicity: mechanism and prevention. Cancer Res. 2006;66:7824–31. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rice KP, Penketh PG, Shyam K, Sartorelli AC. Differential inhibition of cellular glutathione reductase activity by isocyanates generated from the antitumor prodrugs Cloretazine and BCNU. Biochem Pharmacol. 2005;69:1463–72. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Axworthy DB, Hoffmann KJ, Streeter AJ, et al. Covalent binding of acetaminophen to mouse hemoglobin. Identification of major and minor adducts formed in vivo and implications for the nature of the arylating metabolites. Chem Biol Interact. 1988;68:99–116. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(88)90009-9. *Demonstrates that reactive metabolites of acetaminophen are formed in the liver and enter the circulation to interact with hemoglobin.

- 17.Sood C, O’Brien PJ. 2-Chloroacetaldehyde-induced cerebral glutathione depletion and neurotoxicity. Br J Cancer Suppl. 1996l;27:S287–93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen W, Shockcor JP, Tonge R, et al. Protein and nonprotein cysteinyl thiol modification by N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine via a novel ipso adduct. Biochemistry. 1999;38:8159–66. doi: 10.1021/bi990125k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coles B, Wilson I, Wardman P, et al. The spontaneous and enzymatic reaction of N-acetyl-p-benzoquinonimine with glutathione: a stopped-flow kinetic study. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1988;264:253–60. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(88)90592-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Esterbauer H, Zollner H, Scholz N. Reaction of glutathione with conjugated carbonyls. Z Naturforsch C 1975. 1975;30:466–73. doi: 10.1515/znc-1975-7-808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Witz G. Biological interactions of alpha,beta-unsaturated aldehydes. Free Radic Biol Med. 1989;7:333–49. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(89)90137-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.LoPachin RM, Gavin T, Geohagen BC, Das S. Neurotoxic mechanisms of electrophilic type-2 alkenes: soft soft interactions described by quantum mechanical parameters. Toxicol Sci. 2007;98:561–70. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfm127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schwo bel JA, Wondrousch D, Koleva YK, et al. Prediction of Michael-Type Acceptor Reactivity toward Glutathione. Chem Res Toxicol. 2010;23:1576–85. doi: 10.1021/tx100172x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Richard JP, Jencks WP. A simple relationship between carbocation lifetime and reactivity-selectivity relationships for the solvolysis of ring-substituted 1-phenylethyl derivatives. J Am Chem Soc. 1982;104:4689–4691. * Demonstrates that increasing carbocation stability generally correlates with selectivity for reactions with target nucleophiles.

- 25.Lyle TA, Royer RE, Daub GH, Vander Jagt DL. Reactivity-selectivity properties of reactions of carcinogenic electrophiles and nucleosides: influence of pH on site selectivity. Chem Biol Interactions. 1980;29:197–207. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(80)90033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohen G. Basic Principles of Target Organ Toxicity. In: Cohen G, editor. Target Organ Toxicity. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 1986. pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tarloff JB, Goldstein RS. Biochemical Mechanisms of Renal Toxicity. In: Hodgson E, Levi PE, editors. Introduction to Biochemical Toxicology. Appleton & Lange; Norwalk, Conn: 1994. pp. 519–46. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tune BM, Burg MB, Patlak CS. Characteristics of p-aminohippurate transport in proximal renal tubules. Am J Physiol. 1969;217:1057–63. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1969.217.4.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tune BM, Fernholt M. Relationship between cephaloridine and p-aminohippurate transport in the kidney. Am J Physiol. 1973;225:1114–7. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1973.225.5.1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brogard JM, Comte F, Pinget M. Pharmacokinetics of cephalosporin antibiotics. Antibiot Chemother. 1978;25:123–62. doi: 10.1159/000401060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wold JS, Turnipseed SA, Miller BL. The effect of renal cation transport inhibition on cephaloridine nephrotoxicity. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1979;47:115–22. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(79)90078-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Williams PD, Hitchcock MJ, Hottendorf GH. Effect of cephalosporins on organic ion transport in renal membrane vesicles from rat and rabbit kidney cortex. Res Commun Chem Pathol Pharmacol. 1985;47:357–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tune BM. The nephrotoxicity of β-lactam antibiotics. In: Hook JB, Goldstein RS, editors. Toxicology of the Kidney. Raven Press; New York: 1993. pp. 257–81. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lock EA, Reed CJ. Xenobiotic metabolizing enzymes of the kidney. Toxicol Pathol. 1998;26:18–25. doi: 10.1177/019262339802600102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shimada T, Yamazaki H, Mimura M, et al. Interindividual variations in human liver cytochrome P-450 enzymes involved in the oxidation of drugs, carcinogens and toxic chemicals: studies with liver microsomes of 30 Japanese and 30 Caucasians. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1994;270:414–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thummel KE, Wilkinson GR. In vitro and in vivo drug interactions involving human CYP3A. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1998;38:389–430. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.38.1.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schuetz EG, Schuetz JD, Grogan WM, et al. Expression of cytochrome P450 3A in amphibian, rat, and human kidney. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1992;294:206–14. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(92)90159-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Haehner BD, Gorski JC, Vandenbranden M, et al. Bimodal distribution of renal cytochrome P450 3A activity in humans. Mol Pharmacol. 1996;50:52–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cummings BS, Lash LH. Metabolism and toxicity of trichloroethylene and S-(1,2-dichlorovinyl)-L-cysteine in freshly isolated human proximal tubular cells. Toxicol Sci. 2000;53:458–66. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/53.2.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hu JJ, Rhoten WB, Yang CS. Mouse renal cytochrome P450IIE1: immunocytochemical localization, sex-related difference and regulation by testosterone. Biochem Pharmacol. 1990;40:2597–602. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(90)90576-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pan J, Hong JY, Yang CS. Post-transcriptional regulation of mouse renal cytochrome P450 2E1 by testosterone. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1992;299:110–5. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(92)90251-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lash LH, Tokarz JJ. Oxidative stress in isolated rat renal proximal and distal tubular cells. Am J Physiol. 1990;259:F338–47. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1990.259.2.F338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Safirstein RL. Gene Expression Following Nephrotoxic Exposure. In: Goldstein RS, editor. Renal Toxicology. 1st ed Pergamon; New York: 1997. pp. 449–54. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fogo A. Adaptation in Progression of Renal Injury. In: Goldstein RS, editor. Renal Toxicology. 1st ed Pergamon; New York: 1997. pp. 159–80. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brüning T, Golka K, Makropoulos V, Bolt HM. Preexistence of chronic tubular damage in cases of renal cell cancer after long and high exposure to trichloroethylene. Arch Toxicol. 1996;70:259–60. doi: 10.1007/s002040050271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brüning T, Vamvakas S, Makropoulos V, Birner G. Acute intoxication with trichloroethene: clinical symptoms, toxicokinetics, metabolism, and development of biochemical parameters for renal damage. Toxicol Sci. 1998;41:157–65. doi: 10.1006/toxs.1997.2401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brüning T, Mann H, Melzer H, et al. Pathological excretion patterns of urinary proteins in renal cell cancer patients exposed to trichloroethylene. Occup Med (Lond) 1999;49:299–305. doi: 10.1093/occmed/49.5.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Halmes NC, McMillan DC, Oatis JE, Pumford NR. Immunochemical detection of protein adducts in mice treated with trichloroethylene. Chem Res Toxicol. 1996;9:451–6. doi: 10.1021/tx950171v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miller RE, Guengerich FP. Oxidation of trichloroethylene by liver microsomal cytochrome P-450: evidence for chlorine migration in a transition state not involving trichloroethylene oxide. Biochemistry. 1982;21:1090–7. doi: 10.1021/bi00534a041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Miller RE, Guengerich FP. Metabolism of trichloroethylene in isolated hepatocytes, microsomes, and reconstituted enzyme systems containing cytochrome P-450. Cancer Res. 1983;43:1145–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Elfarra AA, Jakobson I, Anders MW. Mechanism of S-(1,2-dichlorovinyl)glutathione-induced nephrotoxicity. Biochem Pharmacol. 1986;35:283–8. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(86)90527-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lash LH, Anders MW. Cytotoxicity of S-(1,2-dichlorovinyl)glutathione and S-(1,2-dichlorovinyl)-L-cysteine in isolated rat kidney cells. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:13076–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lock EA, Reed CJ. Trichloroethylene: mechanisms of renal toxicity and renal cancer and relevance to risk assessment. Toxicol Sci. 2006;91:313–31. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfj107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dekant W, Vamvakas S, Anders MW. Formation and fate of nephrotoxic and cytotoxic glutathione S-conjugates: cysteine conjugate beta-lyase pathway. Adv Pharmacol. 1994;27:115–62. doi: 10.1016/s1054-3589(08)61031-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lash LH, Putt DA, Brashear WT, et al. Identification of S-(1,2-dichlorovinyl)glutathione in the blood of human volunteers exposed to trichloroethylene. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 1999;56:1–21. doi: 10.1080/009841099158204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bernauer U, Birner G, Dekant W, Henschler D. Biotransformation of trichloroethene: dose-dependent excretion of 2,2,2-trichloro-metabolites and mercapturic acids in rats and humans after inhalation. Arch Toxicol. 1996;70:338–46. doi: 10.1007/s002040050283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lash LH, Elfarra AA, Anders MW. Renal cysteine conjugate beta-lyase. Bioactivation of nephrotoxic cysteine S-conjugates in mitochondrial outer membrane. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:5930–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Elfarra AA, Lash LH, Anders MW. Alpha-ketoacids stimulate rat renal cysteine conjugate beta-lyase activity and potentiate the cytotoxicity of S-(1,2-dichlorovinyl)-L-cysteine. Mol Pharmacol. 1987;31:208–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chen JC, Stevens JL, Trifillis AL, Jones TW. Renal cysteine conjugate beta-lyase-mediated toxicity studied with primary cultures of human proximal tubular cells. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1990;103:463–73. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(90)90319-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Barshteyn N, Elfarra AA. Globin monoadducts and cross-links provide evidence for the presence of S-(1,2-dichlorovinyl)-L-cysteine sulfoxide, chlorothioketene, and 2-chlorothionoacetyl chloride in the circulation in rats administered S-(1,2-dichlorovinyl)-L-cysteine. Chem Res Toxicol. 2009;22:1629–38. doi: 10.1021/tx900219x. ** First demonstration of in vivo bioactivation of DCVC to DCVCS and N-AcDCVCS and subsequent metabolite translocation to the circulation.

- 61.Krause RJ, Elfarra AA. S-(1,2,2-Trichlorovinyl)-L-cysteine sulfoxide, a reactive metabolite of S-(1,2,2-trichlorovinyl)-L-cysteine formed in rat liver and kidney microsomes, is a potent nephrotoxicant. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;321:1095–101. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.120444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kim HS, Cha SH, Abraham DG, et al. Intranephron distribution of cysteine S-conjugate β-lyase activity and its implication for hexachloro-1,3-butadiene-induced nephrotoxicity in rats. Arch Toxicol. 1997;71:131–41. doi: 10.1007/s002040050367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.McGoldrick TA, Lock EA, Rodilla V, Hawksworth GM. Renal cysteine conjugate C-S lyase mediated toxicity of halogenated alkenes in primary cultures of human and rat proximal tubular cells. Arch Toxicol. 2003;77:365–70. doi: 10.1007/s00204-003-0459-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lash LH, Sausen PJ, Duescher RJ, et al. Roles of cysteine conjugate beta-lyase and S-oxidase in nephrotoxicity: studies with S-(1,2-dichlorovinyl)-L-cysteine and S-(1,2-dichlorovinyl)-L-cysteine sulfoxide. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1994;269:374–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Barnsley EA, Thomson AE, Young L. Biochemical studies of toxic agents. 15. The biosynthesis of ethylmercapturic acid sulphoxide. Biochem J. 1964;90:588–96. doi: 10.1042/bj0900588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sklan NM, Barnsley EA. The metabolism of S-methyl-L-cysteine. Biochem J. 1968;107:217–23. doi: 10.1042/bj1070217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Waring RH, Mitchell SC. The metabolism and elimination of S-carboxymethyl-L-cysteine in man. Drug Metab Dispos. 1982;10:61–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sausen PJ, Elfarra AA. Cysteine conjugate S-oxidase. Characterization of a novel enzymatic activity in rat hepatic and renal microsomes. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:6139–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Novick RM, Mitzey AM, Brownfield MS, Elfarra AA. Differential localization of flavin-containing monooxygenase (FMO) isoforms 1, 3, and 4 in rat liver and kidney and evidence for expression of FMO4 in mouse, rat, and human liver and kidney microsomes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;329:1148–55. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.152058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Falls JG, Ryu DY, Cao Y, et al. Regulation of mouse liver flavin-containing monooxygenases 1 and 3 by sex steroids. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1997;342:212–23. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1997.9965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chung WG, Park CS, Roh HK, Cha YN. Induction of flavin-containing monooxygenase (FMO1) by a polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon, 3-methylcholanthrene, in rat liver. Mol Cells. 1997;7:738–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Novick RM, Vezina CM, Elfarra AA. Isoform distinct time-, dose-, and castration-dependent alterations in flavin-containing monooxygenase expression in mouse liver after 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin treatment. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010;79:1345–51. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]