Abstract

Aims: Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) increases angiogenesis by stimulating endothelial cell (EC) migration. VEGF-induced nitric oxide (•NO) release from •NO synthase plays a critical role, but the proteins and signaling pathways that may be redox-regulated are poorly understood. The aim of this work was to define the role of •NO-mediated redox regulation of the sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase (SERCA) in VEGF-induced signaling and EC migration. Results: VEGF-induced EC migration was prevented by the •NO synthase inhibitor, N (G)-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (LNAME). Either VEGF or •NO stimulated endoplasmic reticulum (ER) 45Ca2+ uptake, a measure of SERCA activity, and knockdown of SERCA2 prevented VEGF-induced EC migration and 45Ca2+ uptake. S-glutathione adducts on SERCA2b, identified immunochemically, were increased by VEGF, and were prevented by LNAME or overexpression of glutaredoxin-1 (Glrx-1). Furthermore, VEGF failed to stimulate migration of ECs overexpressing Glrx-1. VEGF or •NO increased SERCA S-glutathiolation and stimulated migration of ECs in which wild-type (WT) SERCA2b was overexpressed with an adenovirus, but did neither in those overexpressing a C674S SERCA2b mutant, in which the reactive cysteine-674 was mutated to a serine. Increased EC Ca2+ influx caused by VEGF or •NO was abrogated by overexpression of Glrx-1 or the C674S SERCA2b mutant. ER store-emptying through the ryanodine receptor (RyR) and Ca2+ entry through Orai1 were also required for VEGF- and •NO-induced EC Ca2+ influx. Innovation and Conclusions: These results demonstrate that •NO-mediated activation of SERCA2b via S-glutathiolation of cysteine-674 is required for VEGF-induced EC Ca2+ influx and migration, and establish redox regulation of SERCA2b as a key component in angiogenic signaling. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 00, 000–000.

Introduction

Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is a potent stimulus of endothelial cell (EC) migration and angiogenesis. Although capable of directly promoting several kinase cascades, such as mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) and Src, through VEGF receptor phosphorylation, VEGF notably stimulates activity of the endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) to promote production of nitric oxide (•NO). The importance of •NO for angiogenesis is well established by studies showing decreased angiogenesis in response to hind-limb ischemia and decreased Matrigel plug angiogenesis (19, 15) in mice lacking eNOS (26, 29, 31). In addition, decreased •NO bioavailability due to disease may contribute to increased vascular permeability (22); decreased •NO-induced vessel relaxation (4, 21); and decreased angiogenesis (18). However, the mechanisms of •NO action in ECs and angiogenesis are not well understood.

Innovation.

Endothelial cell (EC) migration is required for both physiological and pathological angiogenesis. Nitric oxide (•NO)‐dependent signaling is required for vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)‐induced EC migration, but the protein targets that may be redox regulated are poorly understood. Here, we present novel evidence that S‐glutathiolation of SERCA2b cysteine‐674 is a novel specific redox‐regulated target of VEGF‐stimulated •NO production in ECs, which is required for VEGF‐induced Ca2+ influx and cell migration. These data represent a novel redox‐regulated mechanism of EC Ca2+ handling essential to angiogenic function, which constitutes a potential therapeutic target in diseases of altered angiogenesis.

In addition to classical signaling via cyclic guanine monophosphate-dependent mechanisms, •NO can elicit signaling through protein redox modifications. Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS/RNS), such as hydrogen peroxide, and the •NO metabolite, peroxynitrite, are potent mediators of cellular signaling and vascular function. Physiologically, low levels of ROS/RNS regulate cell signaling via reversible post-translational oxidative protein modifications, including S-nitrosation and S-glutathiolation, and these are important for transient changes in protein function (10). The sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase (SERCA) has been identified as an important target of both physiological and pathological redox modification with resulting changes in protein activity (4). S-glutathiolation of purified SERCA at cysteine-674 was demonstrated to cause a 50% increase in maximal Ca2+ uptake activity, and this protein modification has been associated with inhibition of smooth muscle cell (SMC) migration by •NO (28) and increased cardiac myocyte contractility caused by nitroxyl anion (14). ECs represent a distinct redox environment with regard to intracellular production of •NO by eNOS, and the redox regulation of SERCA within the endothelium has not been characterized.

SERCA is located on the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and is responsible for uptake of Ca2+ into the ER required to maintain ER Ca2+ stores. In addition, changes in SERCA activity play an important role in intracellular signaling through regulation of extracellular Ca2+ influx (17). SERCA and its isoforms are the products of three genes: SERCA2b and SERCA3 are expressed in ECs (5, 13, 20), whereas SERCA2b is the principal isoform in smooth muscle (13). Unlike in SMCs, EC migration is enhanced by •NO (23), leading us to study here novel redox regulation mechanisms by which EC SERCA might participate in •NO-dependent, VEGF-induced cell migration.

Our findings show that VEGF induces an •NO-dependent S-glutathiolation of EC SERCA cysteine-674 and increase in SERCA activity that are required for stimulating EC migration into a scratch wound, as well as capillary tube formation. Additionally, knockdown of SERCA2 or overexpression of the C674S SERCA2b mutant prevents both VEGF- and •NO-induced EC migration. We found that VEGF and •NO stimulate Ca2+ influx from the extracellular space into the cytosol and that this is dependent upon both the plasma membrane Ca2+ influx channel, Orai1, and the ER ryanodine receptor (RyR) Ca2+-release channel, identifying a novel regulation of EC Ca2+ influx dependent on ER Ca2+-uptake and release mechanisms. These studies indicate that •NO-mediated S-glutathiolation of EC SERCA C674 induces a novel redox-regulated Ca2+ influx into ECs that is essential for angiogenic signaling.

Results

VEGF-induced increase in EC migration is mediated by •NO and SERCA

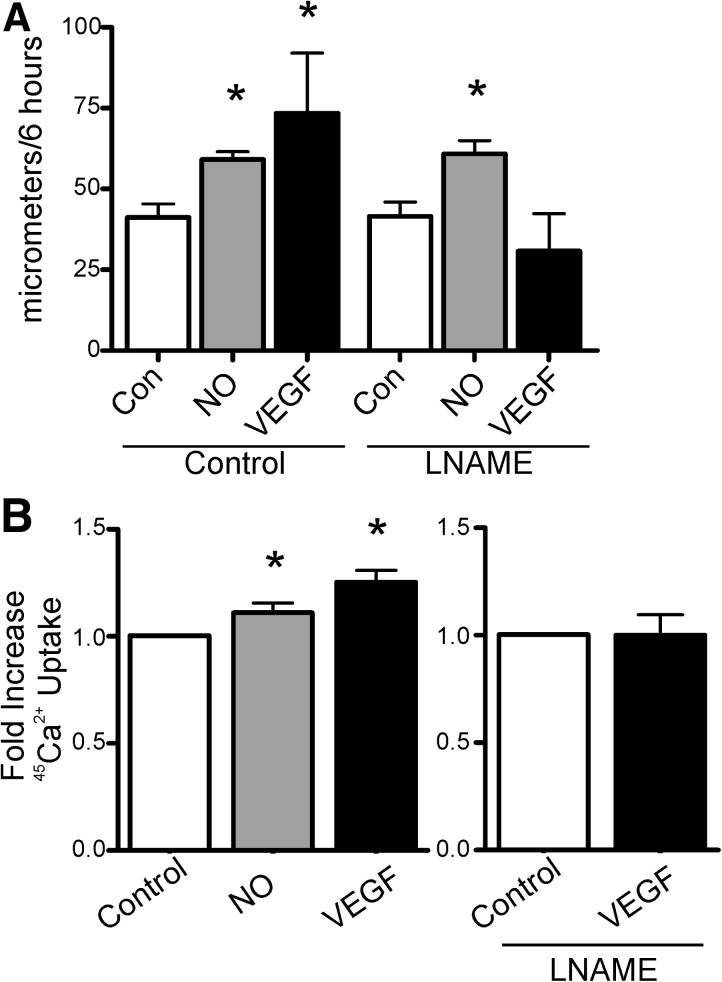

VEGF (50 ng/ml), the •NO donor, diethylenetriamine NONOate (DETA NONOate; 30 μM), or vehicle was added to human aortic ECs (HAECs) for 1 h before scratch wounding of the monolayer and were reapplied at the time of the scratch. Over 6 h, both VEGF and DETA NONOate significantly increased the average distance of migration into the scratch (Fig. 1A). Co-treatment of cells with the •NO synthase inhibitor, N (G)-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (LNAME, 30 μM), prevented the VEGF-induced increase in migration without affecting the migration distance in the vehicle control, consistent with the role of eNOS and •NO in VEGF-induced EC migration. Measurement of SERCA activity as 45Ca2+ uptake showed that DETA NONOate or VEGF significantly increased SERCA activity (Fig. 1B). Additionally, VEGF-induced stimulation of SERCA activity was blocked by LNAME (Fig. 1B). VEGF and •NO also stimulated SERCA activity in bovine aortic endothelial cells (BAECs), and similar to HAECs, stimulation caused by VEGF was blocked by LNAME (Supplementary Fig. S1; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertonline.com/ars). These results indicate that VEGF via •NO stimulates both endothelial cell migration and SERCA activity.

FIG. 1.

VEGF and •NO increase endothelial cell migration and SERCA activity. (A) HAEC monolayers were treated with VEGF (50 ng/ml) or DETA NONOate (30 μM), and then migration into a scratch wound was measured over 6 h. The •NO synthase inhibitor, LNAME (30 μM), was added just before the scratch (n=3). (B) SERCA activity was assessed by thapsigargin-sensitive 45Ca2+ uptake in saponin-permeablized HAECs treated with DETA NONOate or VEGF, or VEGF and LNAME (n=4). * p<0.05 versus control. DETA NONOate, diethylenetriamine NONOate; HAEC, human aortic endothelial cell; LNAME, N (G)-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester; •NO, nitric oxide; SERCA, sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

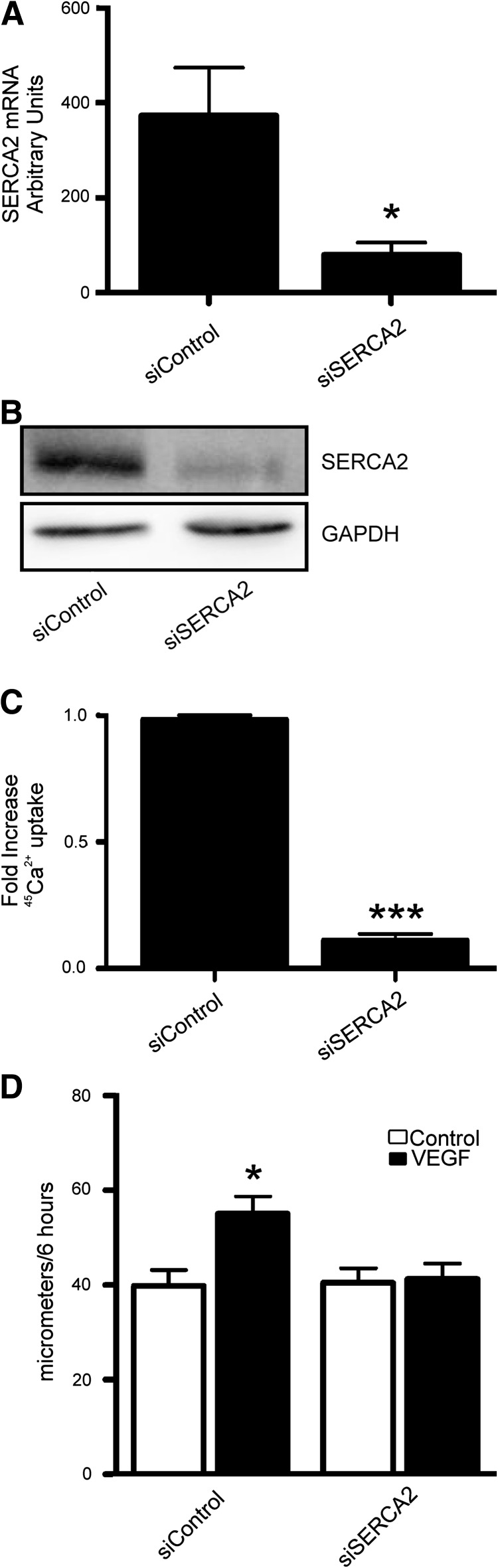

Knockdown of the SERCA2 isoform inhibits Ca2+ uptake and prevents VEGF-induced increase in EC migration

Because ECs contain both SERCA3 and the SERCA2 splice isoform, SERCA2b (5, 13, 20), the specific contribution of SERCA2b to VEGF-induced signaling, was assessed by knockdown of SERCA2 in HAECs using selective siRNA. Knockdown was confirmed by both quantitative real time-polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) for SERCA2 mRNA and western blot for SERCA2b with an isoform-specific antibody (Fig. 2A, B). Cell viability was confirmed by trypan blue exclusion (data not shown). In addition, the basal SERCA activity, assessed by 45Ca2+ uptake, was markedly inhibited by knockdown of SERCA2, indicating that it is the major isoform in these cells (Fig. 2C). Wound-healing migration assays over 6 h showed no change in unstimulated migration between ECs treated with scrambled siRNA controls and siRNA against SERCA2, indicating that basal migration is not dependent on SERCA2 levels (Fig. 2D). However, knockdown of SERCA2 entirely prevented the VEGF-induced increase in HAEC migration, demonstrating an essential role for SERCA2 in VEGF-stimulated EC migratory signaling. Although SERCA3 was also present in these cells, as shown by Western blot and low levels of mRNA as measured by qRT-PCR, ECs treated with SERCA3 siRNA displayed 45Ca2+ uptake similar to that of those treated with scrambled siRNA and migrated similarly to controls in response to VEGF (Supplementary Fig. S2).

FIG. 2.

siRNA-mediated knockdown of SERCA2 prevents VEGF-induced endothelial cell migration. HAECs were treated with specific siRNA to SERCA2. Knockdown was confirmed by qRT-PCR for SERCA2 (A) and immunoblot for SERCA2 [(B), n=4]. HAECs treated with siRNA for SERCA2 were assessed for basal 45Ca2+ uptake [(C), p<0.001, n=3]. HAEC migration with or without VEGF [(D), 50 ng/ml, n=6]. *p<0.05 versus Control.

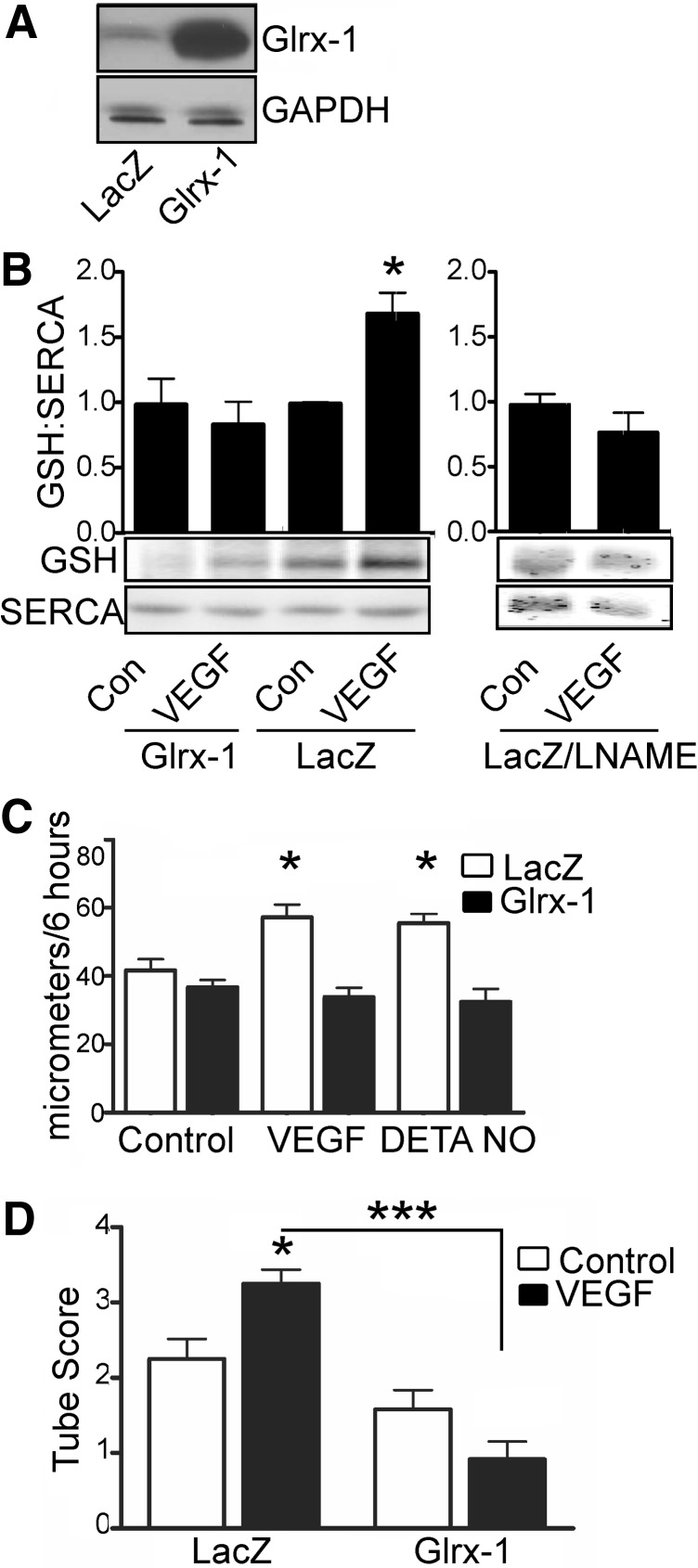

Stimulation of EC migration by VEGF is mediated by S-glutathiolation of SERCA2b and can be prevented by overexpression of Glrx-1

To assess S-glutathiolation of SERCA2b, HAECs were treated with VEGF (50 ng/ml) for 15 min before lysis. SERCA2b was immunoprecipitated using a polyclonal SERCA2 antibody and then western blotted for protein-bound glutathione and SERCA2b. Unstimulated SERCA2b was basally S-glutathiolated; however, addition of VEGF increased S-glutathiolation of SERCA2b, suggesting a role for redox regulation of SERCA in VEGF signaling (Fig. 3B). To confirm the specificity of the antibody probe, glutaredoxin-1 (Glrx-1), which specifically reduces S-glutathione adducts (11), was overexpressed by ∼10-fold (Fig. 3A), and HAECs were treated with VEGF and assessed for SERCA2b S-glutathiolation. Glrx-1 inhibited VEGF-dependent glutathiolation of SERCA2b (Fig. 3B). Similarly, inhibition of •NO production by pretreatment with LNAME prevented VEGF-induced SERCA2b glutathiolation, confirming that •NO produced by VEGF signaling causes the S-glutathiolation of SERCA. To assess functional consequences of S-glutathiolation, HAECs overexpressing Glrx-1 were subjected to a wound-healing scratch assay over 6 h or were assessed for formation of capillary tube-like structures over 24 h. Compared to LacZ controls, Glrx-1 overexpression did not affect migration or tube formation of unstimulated HAECs (Fig. 3C, D and Supplementary Fig. S3A). In contrast, VEGF-stimulated migration and tube formation were prevented, unlike in the LacZ control. In addition, overexpression of Glrx-1 prevented •NO-induced increase in migration (Fig. 3C).

FIG. 3.

VEGF-induced S-glutathiolation of SERCA increases migration of HAECs. (A) HAECs were infected with adenoviral vectors to overexpress β-galactosidase (LacZ) or Glrx-1 by ∼10-fold. (B) VEGF (15 min) or DETA-NONOate (1 min) treatment-induced S-glutathiolation of SERCA was assessed by immunoprecipitation with a polyclonal SERCA antibody, and then immunoblotting for protein-bound glutathione adducts using a monoclonal antibody. Bar graph of densitometry results is shown above a representative blot (n=8, *p<0.05). (C) HAECs overexpressing Glrx-1 were treated with VEGF or DETA NONOate, and then scratch wounded for assessment of migration over 6 h (n=4, *p<0.05 vs. control). HAECs overexpressing LacZ or Glrx-1 were seeded on Matrigel in the presence or absence of VEGF (D) and assessed for tube formation over 24 h (n=4, *p<0.05 vs. LacZ control, ***p<0.001). Glrx, glutaredoxin-1.

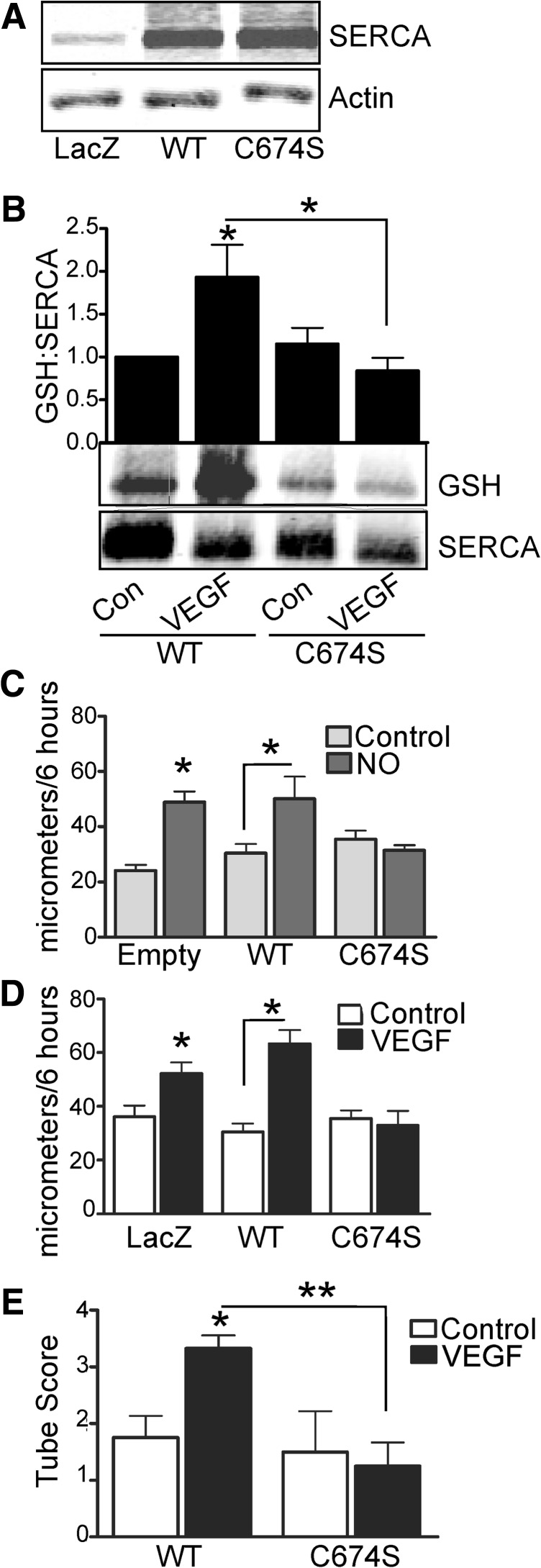

Mutation of the SERCA2b-reactive cysteine-674 prevents VEGF-induced increase in SERCA S-glutathiolation and EC migration

Wild-type (WT) SERCA2b or SERCA2b in which cysteine-674 was mutated to a serine (C674S) was overexpressed in HAECs using adenovirus (Fig. 4A). HAECs overexpressing WT SERCA2b demonstrated increased S-glutathiolation (Fig. 4B) in response to VEGF treatment. In contrast, VEGF-induced SERCA2b S-glutathiolation (Fig. 4B) was inhibited in cells overexpressing SERCA2b C674S. To assess the functional importance of SERCA2b C674, migration in response to either VEGF or •NO was measured over 6 h. Overexpression of WT SERCA2b did not significantly influence the increased migration caused by DETA NONOate or VEGF compared with cells infected with an empty vector or LacZ (Fig. 4C, D). However, overexpression of SERCA2b C674S prevented increased migration due to either DETA NONOate (Fig. 4C) or VEGF (Fig. 4D). Similarly, expression of SERCA2b C674S, but not WT SERCA2b, prevented increased formation of EC capillary tube-like structures in response to VEGF (Fig. 4E and Supplementary Fig. S3B).

FIG. 4.

Mutation of SERCA2b-reactive cysteine-674 prevents VEGF- or •NO-induced S-glutathiolation and endothelial cell migration. (A) WT SERCA2b or SERCA2b C674S was overexpressed in HAECs by ∼3-fold with adenoviral vectors. (B) S-glutathiolation of either WT SERCA2b or SERCA2b C674S was assessed in HAECs by immunoprecipitation of SERCA2b and immunoblot of protein-bound glutathione (n=4, *p<0.05 vs. control). Migration over 6 h in response to DETA NONOate [(C), n=3, *p<0.05] or VEGF [(D), n=4, *p<0.05] was assessed in HAECs overexpressing WT or C674S SERCA2b. (E) EC tube formation in response to VEGF was assessed at 24 h and quantified by scoring of tube number (*p<0.05 vs. vehicle control, **p<0.01). EC, endothelial cell; WT, wild type.

Redox regulation of SERCA is required for the VEGF-induced EC Ca2+ influx

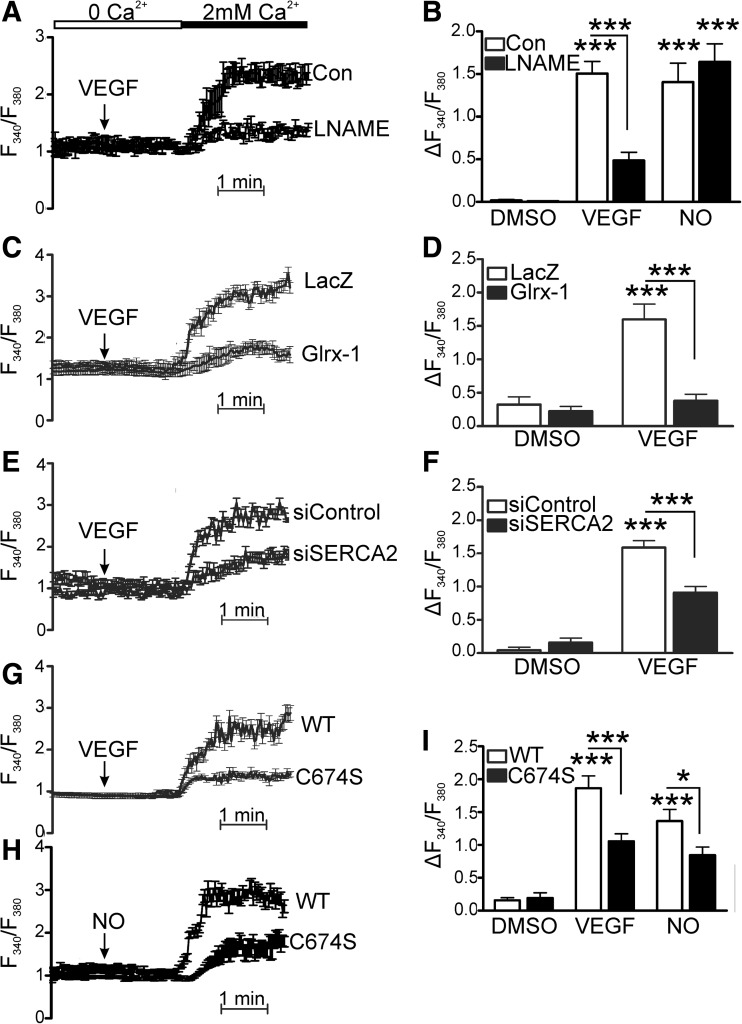

Ca2+ influx was essential for VEGF-induced migration, demonstrated by the Ca2+ entry blocker, nickel (100 μM), which prevented both the increase in intracellular Ca2+ and HAEC migration caused by VEGF (Supplementary Fig. S4). To investigate the redox regulation of Ca2+ signaling in ECs, the effects of Glrx-1 overexpression and S-glutathiolation of SERCA2b on influx of extracellular Ca2+ into the cytosol after stimulation by VEGF were measured using Fura2. We first confirmed that Ca2+ influx was not stimulated by Ca2+ addition alone in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) vehicle controls (Supplementary Fig. S4D). In the absence of extracellular Ca2+, VEGF had no significant effect on intracellular Ca2+ levels, but caused a robust increase in Ca2+ upon Ca2+ re-addition (Fig. 5) Demonstrating the importance of •NO production, we found that LNAME treatment inhibited VEGF-induced Ca2+ influx (Fig. 5A, B). In addition, we found that VEGF-induced increase in Ca2+ influx was significantly less in cells overexpressing Glrx-1 compared with cells expressing LacZ (Fig. 5C, D). This finding suggests that VEGF-induced influx of extracellular Ca2+ is regulated by a novel redox mechanism involving protein S-glutathiolation. To assess the specific role of SERCA2b in VEGF-induced Ca2+ influx, SERCA2 was knocked down using siRNA. VEGF-induced Ca2+ influx was significantly inhibited in cells with decreased SERCA2b expression compared to cells treated with nontargeting siRNA (Fig. 5E, F). Additionally, overexpression of SERCA2b C674S, but not WT SERCA2b, significantly decreased not only VEGF-induced Ca2+ influx but also •NO-induced Ca2+ influx (Fig. 5G, H), indicating a critical role for •NO-dependent redox regulation of SERCA2b C674 in VEGF- and •NO-induced Ca2+ signaling.

FIG. 5.

Inhibition of nitric oxide synthase, knockdown of SERCA2, or overexpression of Glrx-1 or SERCA2b C674S mutant decreases VEGF-induced Ca2+ entry. (A, B) VEGF or •NO was added in the absence of extracellular Ca2+, and the maximal increase in intracellular Ca2+ associated with Ca2+ influx upon Ca2+ (2 mM) re-addition was assessed in ECs treated with LNAME (30 μM, n=4, ***p<0.001). Data shown are the representative VEGF response trace with mean±standard error of the mean of Ca2+ for measured cells (A) and quantification of change in Fura2 fluorescence ratio between baseline and maximal Ca2+ in VEGF- and •NO-stimulated cells (B). (C, D) Ca2+ influx in HAECs overexpressing LacZ or Glrx-1 representative trace (C) and quantification of maximal Ca2+ associated with Ca2+ influx [(D), n=at least 4, ***p<0.001]. (E, F) Ca2+ influx in EC, in which SERCA2 was knocked down by siRNA [(E), n=4, ***p<0.001] and representative trace of Fura2 in HAECs treated with VEGF before Ca2+ addition (F). (G–I) Ca2+ influx in ECs overexpressing either WT SERCA2b or SERCA2b C674S [(I), n=at least 4, *p<0.05, ***p<0.001] and representative traces of Fura2 ratio in HAECs treated with VEGF (G) or •NO (H) before Ca2+ addition.

Orai1 and RyR are required for redox-dependent Ca2+ influx

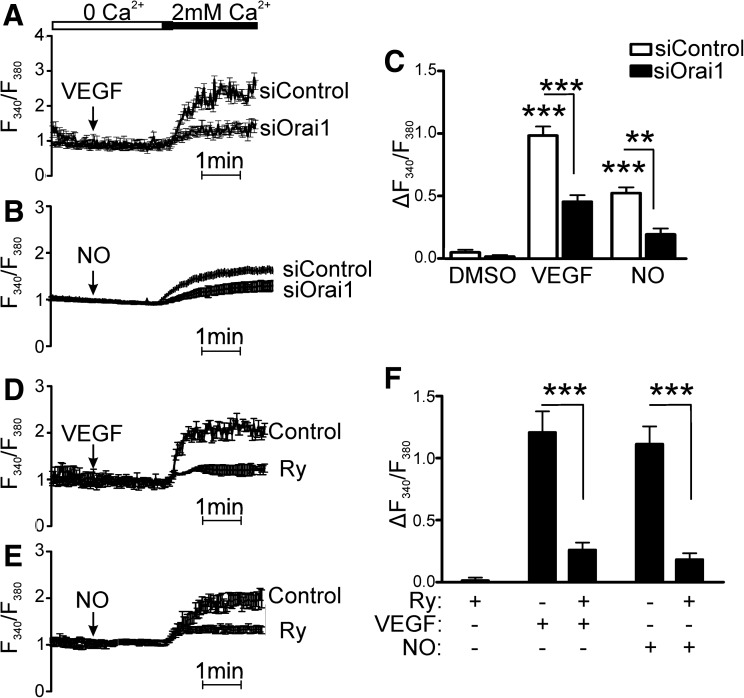

Orai1, a plasma membrane Ca2+ influx channel, was knocked down because of its reported importance to Ca2+ entry during VEGF stimulation (16). Forty-eight hours after EC transfection with siRNA specific to Orai1, Ca2+ influx in response to VEGF was significantly inhibited (Fig. 6A). In addition, we also found that •NO-induced Ca2+ influx was prevented when Orai-1 was knocked down (Fig. 6B).

FIG. 6.

Store-operated Ca2+ influx and store-emptying are required for VEGF-induced Ca2+ influx. (A–C) Ca2+ influx in HAECs in response to VEGF or •NO in cells treated with siRNA against Orai1 shown as the representative VEGF (A) or •NO gas (B) response trace and quantitation of maximal Ca2+ [(C), n=3, ***p<0.001]. (D–F) Ca2+ influx in response to VEGF or •NO after treatment with ryanodine (100 μM) representative VEGF (D) and •NO gas trace (E) and quantification of maximal Ca2+ [(F), n=3, ***p<0.001]. Ry, ryanodine.

Next, the potential mechanisms of VEGF-dependent Ca2+ store-emptying were assessed. It has previously been shown that HAECs have ER RyR Ca2+-release channels, and that their activation causes extracellular Ca2+ influx (7), but nothing is known about their involvement in VEGF signaling. First, we confirmed that caffeine caused Ca2+ influx in HAECs, and that this could be blocked by inhibiting RyR channel opening with ryanodine (100 μM, data not shown). Ca2+ influx in response to either VEGF or •NO was then measured in the presence of the same ryanodine concentration. Inhibition of the RyR with ryanodine prevented both VEGF- and •NO-stimulated Ca2+ influx (Fig. 6C, D), suggesting that ER Ca2+ store-emptying, in addition to Ca2+ uptake by SERCA2b, is required for VEGF-induced Ca2+ influx.

Discussion

Our studies reveal three novel findings regarding the mechanism of VEGF-induced EC migration. First, we identify that SERCA2b, and specifically the redox- active cysteine 674, is required for VEGF-induced EC migration. Second, VEGF-induced EC migration depends upon •NO-mediated S-glutathione adducts on SERCA2b cysteine-674, and both can be prevented by Glrx-1. Third, we demonstrate a novel redox-dependent regulation of VEGF-induced EC Ca2+ influx that depends on •NO-mediated redox regulation of SERCA2b. Although the role of •NO in VEGF-mediated EC migration is well recognized, its redox-regulated target proteins have not been fully established. Evidence that VEGF-induced •NO production regulates SERCA activity in ECs by S-glutathiolation, which controls Ca2+ influx, provides novel insights into the redox-regulation of VEGF-mediated angiogenic signaling.

Previous studies from our lab and others (2–4, 14, 28, 30) have demonstrated the importance of SERCA redox regulation in both physiology and disease, but its contribution to EC physiology has not been widely explored. In these studies, we determined that the ubiquitous SERCA isoform, SERCA2b, accounts for the majority of the SERCA activity and is required for VEGF- or •NO-induced migration. Although SERCA3 is also present in these cells, low mRNA levels, as measured by qRT-PCR (Supplementary Fig. S2), indicate that this isoform is poorly expressed in cultured HAECs. In addition, SERCA activity was unaffected, and ECs were still able to respond to VEGF in ECs treated with SERCA3 siRNA (Supplementary Fig. S2). In contrast, knockdown of SERCA2 eliminated the large majority of EC SERCA activity and accounted for VEGF-induced migration. A role for SERCA3 in other ECs cannot be excluded, because its expression varies markedly in culture (20). Although not addressed here directly, the arginine-rich environment of the amino acid sequence containing C675 of SERCA3 is similar to that which confers increased reactivity to C674 of SERCA2 (27), so that it too might be redox-sensitive.

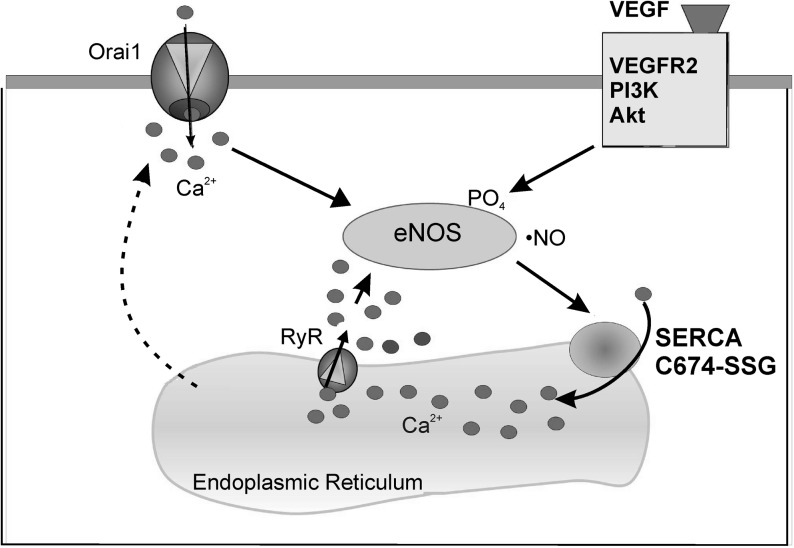

Although redox regulation of SERCA2b has been explored previously in the context of SMCs, the presence of eNOS in ECs provides a unique redox environment that can affect SERCA function. We determined that VEGF stimulation in ECs required an eNOS activity, and that this led to S-glutathiolation of the SERCA2b-reactive cysteine-674. As a consequence of this redox modification, SERCA Ca2+ uptake activity was enhanced, and Ca2+ influx was stimulated. Interestingly, VEGF-induced Ca2+ influx was dependent on SERCA S-glutathiolation and could be prevented either by overexpression of Glrx-1 or SERCA2b C674S mutant or by knockdown of SERCA2, indicating that SERCA2b redox is critical for the VEGF-induced EC Ca2+ response. In addition, we determined that the RyR channel activity, which can mediate ER Ca2+ store-emptying, is required for VEGF-induced Ca2+ influx. RyRs have previously been found in HAECs, and their stimulation was shown to cause Ca2+ influx (32, 33), potentially by the way of store-operated Ca2+ entry. In agreement with previous reports, we found that VEGF-stimulated Ca2+ influx depended upon Orai1 channels (1, 16). Additionally, we found that •NO stimulates Orai1-dependent Ca2+ influx, supporting the involvement of these channels in a redox-sensitive pathway involving stimulation of SERCA-dependent ER Ca2+ uptake. We propose that the SERCA2b and RyR activity in response to VEGF plays an important role in Ca2+ cycling through the ER. Ca2+ influx is required for replenishment of that released from ER stores and is required for EC angiogenic signaling, including eNOS activation and redox-dependent Ca2+ reuptake by SERCA (as shown in Fig. 7). This model of •NO-induced cycling of Ca2+ through the ER is quite distinct from that proposed in SMCs, in which •NO-induced S-glutathiolation of SERCA refills SR stores and inhibits store-operated Ca2+ influx (4, 6). It is notable that the RyR activity is also known to be redox-regulated by •NO (8), and it is possible that in addition to SERCA, the RyR and potentially other redox-regulated proteins coordinate the Ca2+ response to VEGF and NO.

FIG. 7.

A model for VEGF-induced, SERCA2b C674-dependent Ca2+ influx in ECs. VEGF stimulation promotes the production of •NO by eNOS, leading to S-glutathiolation of the SERCA2b-reactive cysteine-674 and activation of SERCA2b. Ca2+ is pumped by SERCA2b into the ER, where it is then released by the RyR, eliciting continued activation of eNOS. Additionally, activation of the plasma membrane Ca2+ channel, Orai1, stimulates Ca2+ influx from the extracellular space into the cytosol, further stimulating eNOS and stimulating EC migration. eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; RyR, ryanodine receptor.

Our studies show that stimulation of EC SERCA2b activity by S-glutathiolation of cysteine-674 is essential for VEGF-induced Ca2+ influx and EC migration. We therefore propose that •NO-dependent stimulation of SERCA activity increases Ca2+ entry, and is required for driving early angiogenic events of migration and tube formation. These studies suggest that the redox status of SERCA may be important in inducing therapeutic angiogenesis or inhibiting pathological angiogenesis.

Materials and Methods

Materials

The Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM), fetal bovine serum (FBS), and SERCA siRNAs were purchased from Invitrogen. TaqMan primers and real time-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) reagents were purchased from Applied Biosystems. BAECs were purchased from Cell Systems. HAECs (19 years old, female) and the endothelial growth medium were purchased from Lonza. The SERCA3 antibody was from Affinity Bioreagents. The SERCA2 IID8 antibody was purchased from Santa Cruz Biochemicals. The rabbit polyclonal SERCA antibody was generated by Bethyl Laboratory. The glutathione antibody was from Virogen. Recombinant human VEGF-165 was purchased from R&D Biosciences. LNAME, thapsigargin, ryanodine, and DETA NONOate were purchased from Sigma.

Adenoviral constructs and infection

Adenoviral WT SERCA and mutant SERCA (C674S) were designed as previously described (4). SERCA adenoviruses were screened for proper constructs by extraction of viral DNA using the RedExtract-N-Amp Tissue PCR kit (Sigma). Extracted DNA was subjected to polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using a forward primer specific to the viral promoter and a reverse primer located beyond the C674 codon: 5′-ACCGTCAGATCCGCTAGAGA-3′ and 5′-GCCACAATGGTGGAGAAGTT-3′. PCR products were cleaned using a Qiagen QiaQuick PCR Purification kit and then sequenced using the sequencing primer: 5′-GATCACTGGGGACAACAAGG-3′. SERCA adenovirus was purified using the double cesium chloride purification technique. Adenoviral E1A contamination of the purified SERCA adenovirus was excluded as described previously (12). ECs were infected to achieve equal expression of WT SERCA2b and SERCA2b C674S protein at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of ≈10. Adenoviral Glrx-1 was previously reported (25) and was delivered at an MOI of ≈10. Cells were infected in FBS-free media and 10 μg/ml Polybrene (Sigma) for 48 h. Cells were quiesced for 24 h in the medium with 0.1% serum before treatments.

45Ca2+ uptake assays

Ca2+ uptake into the ER was measured using an oxalate-dependent ER 45Ca2+ uptake assay in cells in which the cell membrane was permeabilized. Cells were treated with VEGF (50 ng/ml) with or without LNAME (30 μM) or DETA NONOate (30 μM) for times indicated. The medium was replaced with a Ca2+ uptake solution (in mM: 30 Tris–HCl, 100 KCl, 5 NaN3, 6 MgCl2, 0.15 EGTA, 0.12 CaCl2, and 10 oxalate), and ECs were permeablized with saponin (250 μg/mL) before treatment with thapsigargin (TG) (10 μM, 20 min), such that the extravesicular Ca2+ concentration was controlled by buffer content. After treatment, cells were trypsinized and then incubated in a solution with 45Ca2+ (1 μCi) and ATP (2 mM). After 30 min, cells were filtered through Whatman GF/C glass filters under vacuum and washed with physiological saline solution (PSS). Radioactivity was measured on a Beckman Coulter LS1801 scintillation counter. 45Ca2+ uptake was evaluated by counting radioactivity on the filters and normalized to protein concentration measured by the Bradford assay.

siRNA infection

To knockdown SERCA expression, HAECs were cultured for 48 h with the SERCA2-specific siRNA constructs 5′-ACCAGUAUGAUGGUCUGGUAGAAUU-3′ and 5′-AAUUCUACCAGACCAUCAUACUGGU-3′, the SERCA3-specific constructs 5′-CCAUCUACAGCAACAUGAAGCAAU-3′ and 5′-AAUUGCUUCAUGUUGCUGUAGAUGG-3′, or a scrambled siRNA control (Invitrogen) with Lipofectamine (Invitrogen) reagent in serum-free, antibiotic-free endothelial basal medium-2 (EBM-2).

Migration assay

BAECs or HAECs were grown to 80% confluency and quiesced overnight. Scratch wounds were applied to EC monolayers in low-serum media as previously described (28, 30). Inhibitors were given 1 h before making a scratch wound with a pipette tip and reapplied at the time of the scratch. VEGF (50 ng/ml) or DETA NONOate (30 μM, released concentration ≈1 μM (9) was given at the time of the scratch in a serum-free medium. Images were taken at 0 and 6 h at three fixed locations along the scratch (Supplementary Fig. S1). Migration distances were averaged from the three measurements per condition using ImageJ software, and this was considered as n=1 (see Supplementary Methods for expanded details).

Endothelial cell tube formation assay

In vitro capillary tube-like formation on Growth Factor Reduced Matrigel (BD Biosciences) was performed as previously described (24). Briefly, 96-well plates were coated with Matrigel according to the manufacturer's instructions. Appropriately treated HAECs were seeded at a density of 1×104 cells/cm2 with or without 50 ng/ml VEGF in low-serum endothelial growth media (Lonza) and incubated at 37°C overnight. Images were taken at 24 h with the scale indicated in the images, and tube formation was quantified by scoring for the tube number by observers blinded to sample treatment.

qRT-PCR

Quantitative PCR was performed using gene-specific FAM-NFQ-conjugated TaqMan primers for human SERCA2 mRNA sequence 5′-GAGTTACCGGCTGAAGAAGGAAAAA-3′ or human SERCA3 mRNA sequence 5′-CTGGCTATCGGAGTGTACGTAGGCC-3′ (Applied Biosystems). A VIC-NFQ-conjugated human 18S primer was used to normalize mRNA expression levels. Expression was analyzed using the comparative CT (ΔΔCT) with StepOne™ Real Time PCR Software (Applied Biosystems).

Immunoprecipitation

HAECs were infected with Glrx-1 or LacZ for 48 h and then quiesced in EBM-2 with 0.1% FBS. Cells were initially treated with VEGF over a time course of 0–60 min to determine the time of peak S-glutathiolation. Cells were treated with VEGF for 5 min or •NO gas solution (10 μM) for 1 min. Lysates were incubated with a custom polyclonal SERCA2 antibody and immunoblotted with a monoclonal GSH antibody (Virogen) and a monoclonal SERCA2 antibody (Santa Cruz).

Intracellular Ca2+ imaging

HAECs plated on gelatin-coated glass coverslips were loaded with 2 μM Fura2-AM (Invitrogen) in the presence of 0.02% pluronic F127 (Invitrogen) in serum-free endothelial growth media, and right before the experiment were transferred to nominally Ca2+-free PSS supplemented with 2.5 mM probenecid (Alfa Aesar, Ward Hill, MA). Changes in intracellular Ca2+ (F340/F380) were monitored as previously described (7, 31). Briefly, cells were allowed to equilibrate in nominally Ca2+-free PSS for 1 min before addition of VEGF, •NO, or TG. After 2.5 min, Ca2+ (2 mM) was added to the PSS. Ca2+ influx was recorded for 2 min before addition of ionomycin (2 μM) to permeablize the membrane and manganese (8 mM) to quench the Fura2. A dual-excitation fluorescence-imaging system (Intracellular Imaging) was used for studies of individual cells. The changes in intracellular Ca2+ were expressed as ΔRatio, which was calculated for each cell as the difference between the maximal F340/F380 ratio after extracellular Ca2+ was added, and its level right before Ca2+ addition (see Supplementary Methods for expanded details).

Western blotting

Samples in the Laemmli buffer were run on 10% electrophoresis gels. Proteins were transferred onto supported nitrocellulose membranes and blocked with 5% milk. Primary antibodies were incubated overnight at 4°C in milk. Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated or IR dye-conjugated secondary antibodies were used. Blots were imaged using film or the LICOR system.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the Student's t-test or one-way analysis of variance with a Bonferroni multiple comparisons post-test. Results are expressed as means±SE. p<0.05 was considered significant.

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations Used

- BAEC

bovine aortic endothelial cell

- C674S

cysteine-674 mutated to serine

- DETA NONOate

diethylenetriamine NONOate

- DMEM

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- EBM-2

endothelial basal medium-2

- EC

endothelial cell

- eNOS

endothelial nitric oxide synthase

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- Glrx-1

glutaredoxin-1

- GMP

guanine monophosphate

- GSH

reduced glutathione

- HAEC

human aortic endothelial cell

- HRP

horseradish peroxidase

- IR

infrared

- LNAME

N (G)-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MOI

multiplicity of infection

- •NO

nitric oxide

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- PSS

physiological saline solution

- qRT-PCR

quantitative real time-PCR

- RNS

reactive nitrogen species

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- RT-PCR

real time-PCR

- RyR

ryanodine receptor

- SERCA

sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase

- SMC

smooth muscle cell

- TG

thapsigargin

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- WT

wild type

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Health Grants HL031607-29 (R.A.C. and X.Y.T.) and Grants RO1-HL54150 and RO1-HL071793 (V.B.), NIH Predoctoral Training Grant HL007501-26 (A.E.), and the Boston University Levinsky Fellowship (A.E.). These studies were supported by the Calcium Affinity Research Collaborative of the Evans Center, Department of Medicine, Boston University Medical Center.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Abdullaev IF. Bisaillon JM. Potier M. Gonzalez JC. Motiani RK. Trebak M. Stim1 and Orai1 mediate CRAC currents and store-operated calcium entry important for endothelial cell proliferation. Circ Res. 2008;103:1289–1299. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000338496.95579.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adachi T. Matsui R. Weisbrod RM. Najibi S. Cohen RA. Reduced sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca(2+) uptake activity can account for the reduced response to NO, but not sodium nitroprusside, in hypercholesterolemic rabbit aorta. Circulation. 2001;104:1040–1045. doi: 10.1161/hc3501.093798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adachi T. Schoneich C. Cohen RA. S-glutathiolation in redox-sensitive signaling. Drug Discov Today. 2005;2:39–46. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adachi T. Weisbrod RM. Pimentel DR. Ying J. Sharov VS. Schoneich C. Cohen RA. S-glutathiolation by peroxynitrite activates SERCA during arterial relaxation by nitric oxide. Nat Med. 2004;10:1200–1207. doi: 10.1038/nm1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anger M. Samuel JL. Marotte F. Wuytack F. Rappaport L. Lompre AM. In situ mRNA distribution of sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca(2+)-ATPase isoforms during ontogeny in the rat. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1994;26:539–550. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1994.1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen RA. Weisbrod RM. Gericke M. Yaghoubi M. Bierl C. Bolotina VM. Mechanism of nitric oxide-induced vasodilatation: refilling of intracellular stores by sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase and inhibition of store-operated Ca2+ influx. Circ Res. 1999;84:210–219. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.2.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Corda S. Spurgeon HA. Lakatta EG. Capogrossi MC. Ziegelstein RC. Endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ depletion unmasks a caffeine-induced Ca2+ influx in human aortic endothelial cells. Circ Res. 1995;77:927–935. doi: 10.1161/01.res.77.5.927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donoso P. Sanchez G. Bull R. Hidalgo C. Modulation of cardiac ryanodine receptor activity by ROS and RNS. Front Biosci. 2011;16:553–567. doi: 10.2741/3705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feelisch M. Stamler JS. Donors of nitrogen dioxides. In: Feelisch M, editor; Stamler JS, editor. Methods in Nitric Oxide Research. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 1996. pp. 71–115. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Foster MW. Hess DT. Stamler JS. Protein S-nitrosylation in health and disease: a current perspective. Trends Mol Med. 2009;15:391–404. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gallogly MM. Mieyal JJ. Mechanisms of reversible protein glutathionylation in redox signaling and oxidative stress. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2007;7:381–391. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haeussler DJ. Evangelista AM. Burgoyne JR. Cohen RA. Bachschmid MM. Pimental DR. Checkpoints in adenoviral production: cross-contamination and E1A. PLoS One. 2011;6:e23160. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khan I. Sandhu V. Misquitta CM. Grover AK. SERCA pump isoform expression in endothelium of veins and arteries: every endothelium is not the same. Mol Cell Biochem. 2000;203:11–15. doi: 10.1023/a:1007093516593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lancel S. Zhang J. Evangelista A. Trucillo MP. Tong X. Siwik DA. Cohen RA. Colucci WS. Nitroxyl activates SERCA in cardiac myocytes via glutathiolation of cysteine 674. Circ Res. 2009;104:720–723. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.188441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee PC. Salyapongse AN. Bragdon GA. Shears LL. Watkins SC. Edington HD. Billiar TR. Impaired wound healing and angiogenesis in eNOS-deficient mice. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:H1600–H1608. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.277.4.H1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li J. Cubbon RM. Wilson LA. Amer MS. McKeown L. Hou B. Majeed Y. Tumova S. Seymour VA. Taylor H. Stacey M. O'Regan D. Foster R. Porter KE. Kearney MT. Beech DJ. Orai1 and CRAC channel dependence of VEGF-activated Ca2+ entry and endothelial tube formation. Circ Res. 2011;108:1190–1198. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.243352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manjarres IM. Rodriguez-Garcia A. Alonso MT. Garcia-Sancho J. The sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca(2+) ATPase (SERCA) is the third element in capacitative calcium entry. Cell Calcium. 2010;47:412–418. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller TW. Isenberg JS. Roberts DD. Molecular regulation of tumor angiogenesis and perfusion via redox signaling. Chem Rev. 2009;109:3099–3124. doi: 10.1021/cr8005125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Min JK. Cho YL. Choi JH. Kim Y. Kim JH. Yu YS. Rho J. Mochizuki N. Kim YM. Oh GT. Kwon YG. Receptor activator of nuclear factor (NF)-kappaB ligand (RANKL) increases vascular permeability: impaired permeability and angiogenesis in eNOS-deficient mice. Blood. 2007;109:1495–1502. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-06-029298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mountian I. Manolopoulos VG. De SH. Parys JB. Missiaen L. Wuytack F. Expression patterns of sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca(2+)-ATPase and inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor isoforms in vascular endothelial cells. Cell Calcium. 1999;25:371–380. doi: 10.1054/ceca.1999.0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raghavan SA. Dikshit M. Vascular regulation by the L-arginine metabolites, nitric oxide and agmatine. Pharmacol Res. 2004;49:397–414. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2003.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sessa WC. Molecular control of blood flow and angiogenesis: role of nitric oxide. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7(Suppl 1):35–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sinha S. Sridhara SR. Srinivasan S. Muley A. Majumder S. Kuppusamy M. Gupta R. Chatterjee S. NO (nitric oxide): the ring master. Eur J Cell Biol. 2011;90:58–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Skurk C. Maatz H. Rocnik E. Bialik A. Force T. Walsh K. Glycogen-synthase kinase3beta/beta-catenin axis promotes angiogenesis through activation of vascular endothelial growth factor signaling in endothelial cells. Circ Res. 2005;96:308–318. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000156273.30274.f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Song JJ. Lee YJ. Differential role of glutaredoxin and thioredoxin in metabolic oxidative stress-induced activation of apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1. Biochem J. 2003;373:845–853. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tamarat R. Silvestre JS. Kubis N. Benessiano J. Duriez M. deGasparo M. Henrion D. Levy BI. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase lies downstream from angiotensin II-induced angiogenesis in ischemic hindlimb. Hypertension. 2002;39:830–835. doi: 10.1161/hy0302.104671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tong X. Evangelista A. Cohen RA. Targeting the redox regulation of SERCA in vascular physiology and disease. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2010;10:133–138. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2009.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tong X. Ying J. Pimentel DR. Trucillo M. Adachi T. Cohen RA. High glucose oxidizes SERCA cysteine-674 and prevents inhibition by nitric oxide of smooth muscle cell migration. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2008;44:361–369. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2007.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Urano T. Ito Y. Akao M. Sawa T. Miyata K. Tabata M. Morisada T. Hato T. Yano M. Kadomatsu T. Yasunaga K. Shibata R. Murohara T. Akaike T. Tanihara H. Suda T. Oike Y. Angiopoietin-related growth factor enhances blood flow via activation of the ERK1/2-eNOS-NO pathway in a mouse hind-limb ischemia model. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:827–834. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.149674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ying J. Tong X. Pimentel DR. Weisbrod RM. Trucillo MP. Adachi T. Cohen RA. Cysteine-674 of the sarco/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase is required for the inhibition of cell migration by nitric oxide. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:783–790. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000258413.72747.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu J. deMuinck ED. Zhuang Z. Drinane M. Kauser K. Rubanyi GM. Qian HS. Murata T. Escalante B. Sessa WC. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase is critical for ischemic remodeling, mural cell recruitment, and blood flow reserve. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:10999–11004. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501444102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ziegelstein RC. Spurgeon HA. Pili R. Passaniti A. Cheng L. Corda S. Lakatta EG. Capogrossi MC. A functional ryanodine-sensitive intracellular Ca2+ store is present in vascular endothelial cells. Circ Res. 1994;74:151–156. doi: 10.1161/01.res.74.1.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ziegelstein RC. Xiong Y. He C. Hu Q. Expression of a functional extracellular calcium-sensing receptor in human aortic endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;342:153–163. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.01.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.