Abstract

Objectives The objectives of this study were to study the safety profile and role of mononuclear stem cells in the rehabilitation of posttraumatic facial nerve paralysis not improving with conventional treatment.

Study Design This is a prospective nonrandomized controlled trial.

Study Setting This study is conducted at Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research (PGIMER), Chandigarh between July, 2007 and December, 2008.

Patients We included eight patients of either sex aged between 18 and 60 years of posttraumatic facial nerve paralysis not improving with conventional treatment presented to PGIMER, Chandigarh between July 2007 and December 2008.

Methods All patients underwent preoperative electroneuronography (ENoG), clinical photography, and high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) temporal bone. All patients then underwent facial nerve decompression and stem cell implantation. Stem cells processing was done in well-equipped bone marrow laboratory. Postoperatively, all patients underwent repeat ENoG and clinical photography at 3 and 6 months to assess for objective and clinical improvement. Clinical improvement was graded according to modified House–Brackmann grading system.

Intervention Done All patients of posttraumatic facial nerve paralysis who were not improving with conventional surgical treatment were subjected to facial nerve decompression and stem cell implantation.

Main Outcome Measures All patients who were subjected to stem cell implantation were followed up for 6 months to assess for any adverse effects of stem cell therapy on human beings; no adverse effects were seen in any of our patients after more than 6 months of follow-up.

Results Majority of the patients were male, with motor vehicle accidents as the most common cause of injury in our series. Majority had longitudinal fractures on HRCT temporal bone. The significant improvement in ENoG amplitude was seen between preoperative and postoperative amplitudes on involved side which was statistically significant (0.041). Clinical improvement seen was statistically significant both for eye closure (p < 0.010) and for deviation of angle of mouth (p < 0.008) at 6-month follow-up in 85% of our patients, far better than the results of previous conventional surgeries.

Conclusion Stem cell therapy can be used safely in human beings without any adverse effects on humans, and it appears to be a promising modality for rehabilitation of patients with posttraumatic facial nerve paralysis not improving with conventional surgical treatment but few more clinical series are required for validation.

Keywords: traumatic facial nerve paralysis, stem cell therapy, rehabilitation

Introduction

Facial nerve (cranial nerve VII) composed of 10,000 neurons of which 7000 are myelinated is more prone to injury as it travels a long distance through a bony canal during its intratemporal course.1,2 Patients with paralysis of the facial nerve has significant functional, aesthetic, and psychological disability from impairment of facial expression, communication, eye exposure, and oral competence.

Common causes of facial nerve paralysis includes Bell's palsy (51%), trauma (22%), herpes zoster encephaliticus (7%), tumors (6%), and infection (4%).3 In cases with posttraumatic facial nerve paralysis, timely surgical intervention results in improvement in ~90% cases.3 The regeneration of facial nerve fibers after wallerian degeneration occurs at ~1 mm/day.4

All rehabilitative procedures which includes observation with or without medical therapy, neurorrhaphy, cable graft, nerve transposition, muscle transposition or transfer, static sling procedures and ancillary eyelid or oral procedure aims at achieving normal appearance, symmetry with voluntary and involuntary facial motion, and minimal donor deficit.

The results of facial nerve decompression as mentioned in the English literature is variable and ranges from 16 to 79% (Griffin et al5 reported good clinical recovery only in 16%; Kamerer6 reported good recovery in 79% patients; McKennan and Chole7 reported good response only in 33% while Green et al8 reported good results only in 38%).This means that 10 to 20% patients live with deviated face even after conventional surgical intervention. To improve the clinical recovery rate of conventional treatment, a new method of rehabilitation adopted by us was to implant stem cells along with facial nerve decompression at the site of nerve transection. Stem cells are pluripotent cells which develop into many types of differentiated cells depending on growth factors and paracrine hormones provided by the local environment in which they are implanted. This prospective study is unique in the sense that for the first time in the world, effect of stem cells in the rehabilitation of facial nerve paralysis was being analyzed and the results in terms of improvement achieved were assessed.

Materials and Methods

This prospective study was conducted on eight patients with posttraumatic facial nerve paralysis who had presented to outpatient services of Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh during the period between July 2007 and December 2008. Patients of either sex or aged between 18 and 65 years who did not improve with conventional treatment were included in our study. Patients of facial nerve paralysis with more than 1 year duration after injury, patients with Bell's palsy, and patients unfit for surgery due to medical reasons were excluded from the study.

All patients underwent detailed history and clinical examination, pure tone audiometry (PTA), and impedance audiometry. High-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) was done in all the patients to look for the site of injury. Routine investigations such as hemogram, electrolytes, chest X-ray, and electrocardiography were also performed in each case. Modified House–Brackmann grading system9 was used as criteria for clinical grading and both preoperative and postoperative clinical grading were done and compared statistically.

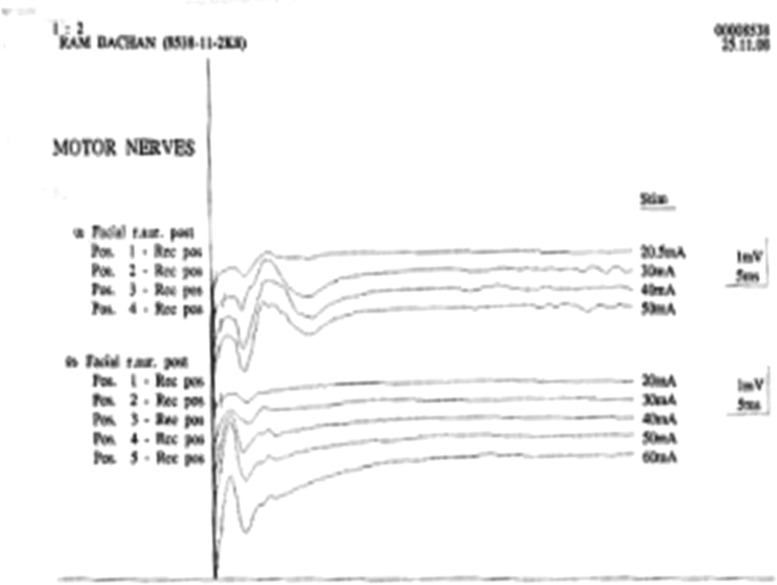

Electroneuronography (ENoG)10,11

ENoG is the most accurate prognostic indicator of all electrodiagnostic tests for evaluation of facial nerve integrity. It helps us to determine whether surgical intervention would be required in a particular patient. ENoG should be performed ~72 hours after the injury as it takes 72 hours for wallerian degeneration to occur. The procedure involves electrical stimulation of facial nerve at or near stylomastoid foramen and the subsequent measurement and interpretation of motor response of facial muscles. After placing the electrodes, the stimulus intensity is increased gradually until a smooth biphasic waveform of maximal amplitude is achieved. The response amplitude of normal side is compared with that of paralyzed side and percentage reduction is calculated which corresponds with the percentage of axonal degeneration (see Figs. 5 and 6). In ENoG, we see the amplitude (µV) and latency (ms) of branches of facial nerve and compare it on both sides. Latency is not critically important for evaluation of ENoG. The percentage degeneration of nerve fibers is calculated by ENoG as follows12:

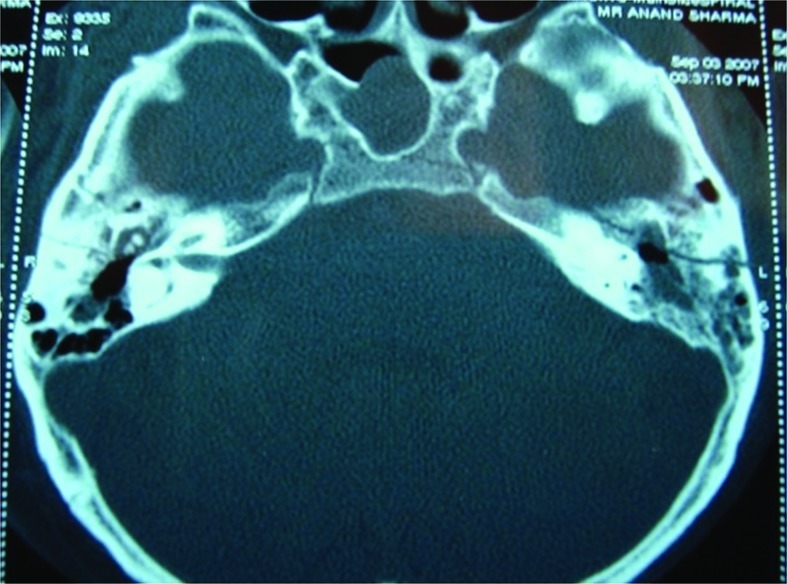

Figure 5.

Axial cut of high-resolution computed tomography temporal bone showing longitudinal fracture on both sides.

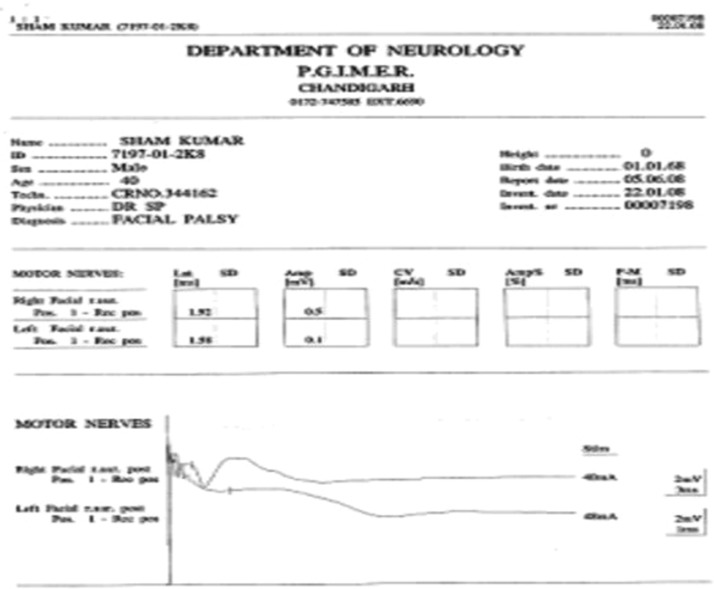

Figure 6.

Preoperative electroneuronography showing flat curves on right side and well-formed amplitude peak on left side.

Normally, any response <10% (>90% degeneration) within 6 days of injury is an indication for surgical intervention.13 ENoG was done both preoperatively and postoperatively in our study for objective assessment. All patients in our study presented to us after 2 to 3 months of injury, so the criteria of >90% degeneration on ENoG within 6 days of injury for surgical exploration as mentioned in the literature13 could not be applied. Thus for our study, ENoG with postoperative objective response >50% (<50% degeneration) was taken as good, and 50 and <50% (50 and >50% degeneration) were taken as poor response.

After fulfilling the selection criteria, all patients underwent facial nerve decompression with stem cell implantation.

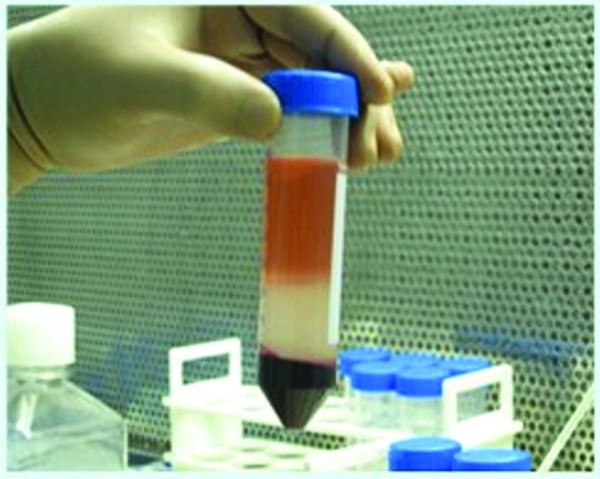

Bone marrow stem cell harvesting and processing: under local anesthesia, approximately 50 mL bone marrow containing mononuclear cells (MNCs) were aspirated from one or both iliac crests and were collected in standard blood collection bag containing anticoagulant/citrate phosphate dextrose adenosine. The ratio of these anticoagulants was 1:5 to 7. The harvested bone marrow was diluted with phosphate buffered saline (biotechnology grade) and was layered onto Ficoll hypaque (warmed to room temperature with specific gravity of 1.077) at the ratio of 3:1. The layered marrow was centrifuged at 400g for 30 minutes at 25°C and the interphase cells were aspirated into a separate container (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Stem cell processing being done at bone marrow laboratory.

Using a sterile pipette, MNCs were transferred into sterile container. Phosphate buffered saline was added to the cell suspension which was washed thrice at 400g for 10 minutes each time before the final suspension in 1 mL of heparinized normal saline.

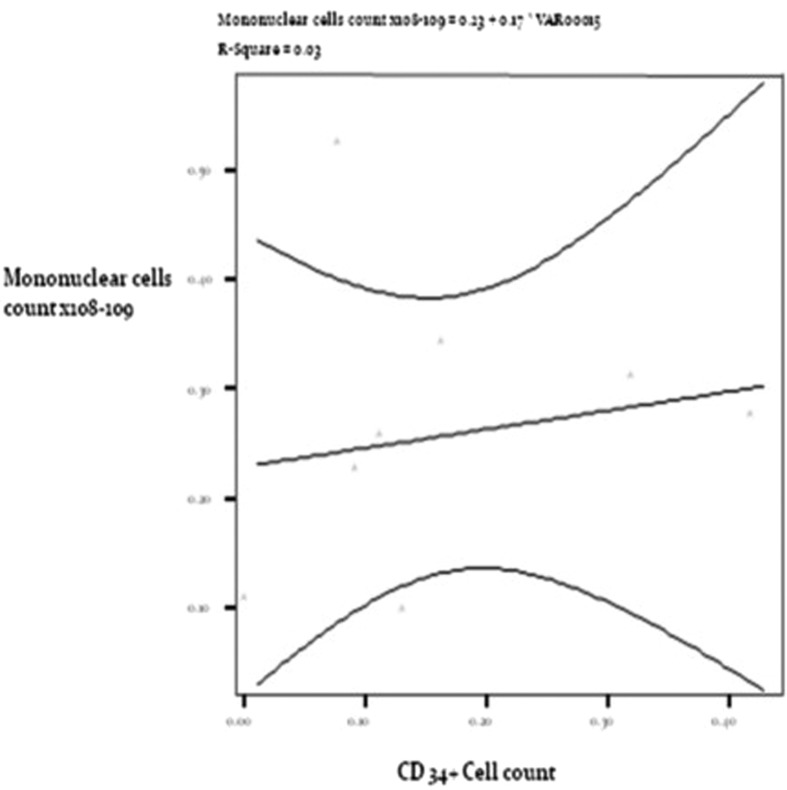

Final cell suspension was checked for total nucleated cell/MNC count, cluster of differentiation (CD)34 count, viability, and microbiology culture for sterility. The final product was loaded in 5 mL disposable syringe with a target dose varying from 1.51 × 108 to 2.32 × 109 MNCs in the syringe. The CD34 count varied from 1.69 × 106 to 3.54 × 107 in the syringe.

Postoperatively, all patients were followed up for a period of 6 months with ENoG for objective assessment and modified House–Brackmann grading system9 for clinical assessment and the data collected were analyzed statistically for improvement in facial paralysis. The modified House–Brackmann grading system9 used for our study was graded as follows:

Grade 1 (normal)—normal facial functions in all areas.

Grade 2 (mild paralysis)—slight weakness noticeable on close inspection, may have slight synkinesis, complete eye closure without effort but slight weakness noticeable on opening the upper eyelid with thumb.

Grade 3 (moderate paralysis)—obvious weakness or disfiguring symmetry and tone at rest, complete eye closure with effort.

Grade 4 (moderately severe paralysis)—only barely perceptible motion, asymmetry at rest, incomplete eye closure.

Grade 5 (complete paralysis)—no movement.

Clinical criteria taken for our study were as follows: grades 1 and 2—good response; grades 3 and 4—moderate response; and grade 5—poor response.

Operative Procedure

Under general anesthesia and orotracheal intubation, patient was positioned, cleaned, and draped. Incision site was infiltrated with local anesthetic and epinephrine. Postauricular incision was made and pinna retracted anteriorly. The transmastoid approach to facial nerve comprised cortical mastoidectomy with removal of mastoid air cells till short process of incus and prominence of horizontal semicircular canal could be identified. Facial nerve was then decompressed completely extending from first genu upto stylomastoid foramen by posterior tympanotomy approach. After identifying the transected site, the bony canal was completely removed both proximally and distally upto 1 cm and the nerve was decompressed by slitting the nerve sheath. In addition, 0.2 mL of mesenchymal stem cell concentrate was injected at the transected site and gelfoam was kept over transected ends. Wound closed with 3-0 vicryl in two layers and aseptic mastoid dressing was done. Pack and stitch removal was done after 10 days.

Follow-Up

All patients were followed up for a minimum period of 6 months and postoperative ENoG was done for objective assessment and the clinical improvement was graded as per modified House–Brackmann grading system.9 The data collected were then analyzed statistically using Wilcoxon signed ranked tests (for paired data) for improvement achieved in facial paralysis. Outcome variables were analyzed using chi-square test.

Results and Analysis

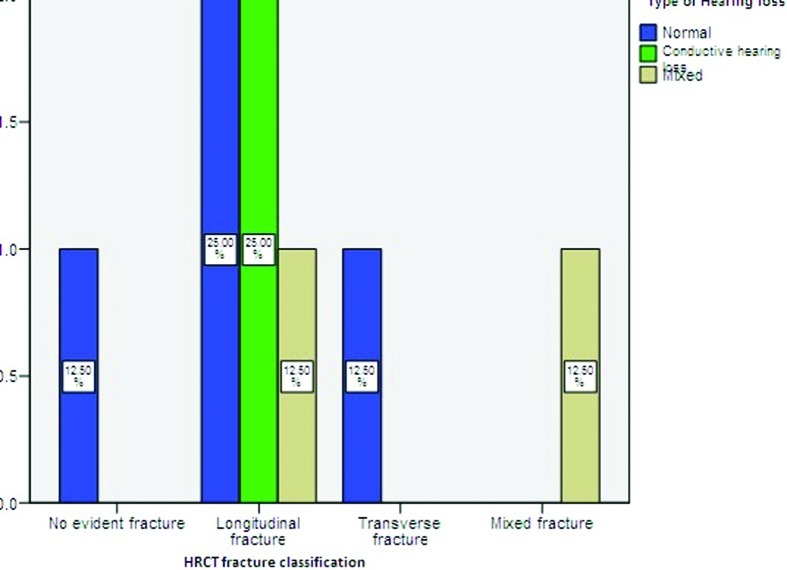

Most of our patients were males (87.5%) and ranged between 20 and 60 years of age with a mean of 33.38 years. The most common mode of injury was motor vehicle accident (50%) followed by assault (25%) and industrial head injury (25%). Facial palsy was immediate in onset in 75% of our cases. Half of the patients presented with hearing loss and tinnitus as associated symptoms along with facial paralysis. The hearing loss was more on the side of fracture and it was conductive in nature. None of the patients had tympanic membrane perforation. A total of 62.5% patients had longitudinal fracture (62.5%) on HRCT temporal bone followed by transverse (12.5%) and mixed fractures (12.5%). No evidence of fracture was present on HRCT temporal bone in 12.5% patients (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Distribution of hearing loss with different types of fracture.

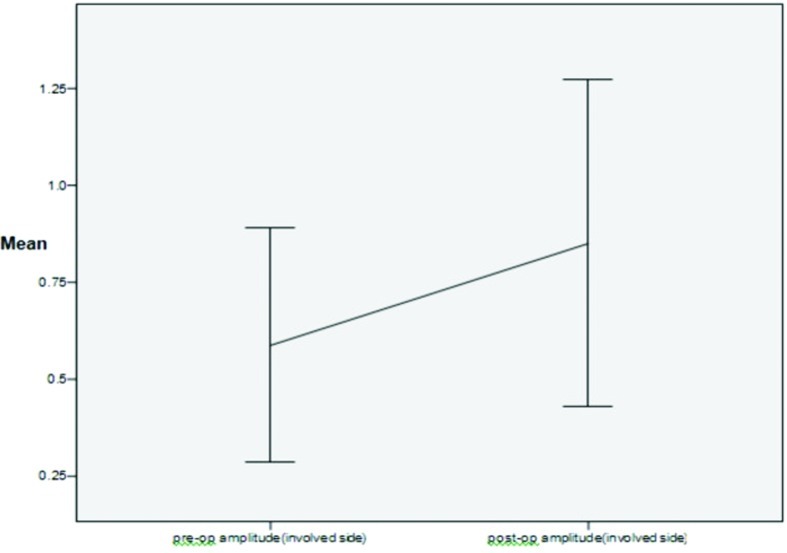

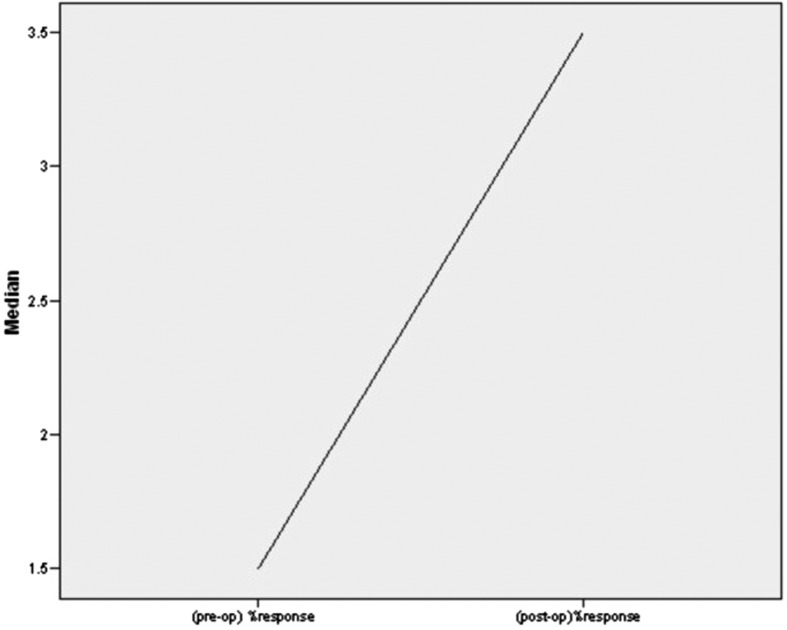

A marked improvement was seen between preoperative (0.59 ± 0.36) and postoperative amplitudes (0.85 ± 0.50) on the side of facial paralysis on ENoG (Fig. 3) though the result was not statistically significant (p < 0.06). The postoperative percentage of intact facial nerve fibers was statistically significant (p < 0.041) when compared with preoperative percentage of intact nerve fibers (Fig. 4). The result was also statistically significant (p < 0.046) when criteria for good objective response (<50% degeneration) and poor objective response (50 and >50% degeneration) was taken into consideration.

Figure 3.

Comparison between preoperative amplitude with postoperative amplitude on involved side.

Figure 4.

Comparison between preoperative percentage of intact fibers with postoperative intact fibers.

All patients showed significant clinical improvement in eye closure at 6 months of follow-up with 87.5% patients showing improvement from grade 4 to grade 1. Improvement in eye closure at 6 months follow-up was highly statistically significant (p < 0.010). The significant clinical improvement was also seen in deviation of angle of mouth with 87.5% patients recovering from grades 4 and 5 to grades 1 and 2 (see Figs. 9 and 10). Improvement in deviation of angle of mouth was highly statistically significant (p < 0.008).

Figure 9.

Preoperative photograph of patient showing posttraumatic right facial nerve paralysis.

Figure 10.

Postoperative photograph of patient showing clinical improvement at 6 month follow-up.

Discussion

Motor vehicle accidents account for majority of cases of severe head trauma in trauma centers. Of these, 14 to 22% sustain temporal bone fracture, resulting in cerebrospinal fluid fistula, facial nerve paralysis, sensorineural or conductive hearing loss, vertigo, and meningitis.14,15 Approximately, 7 to 10% fractures are associated with facial nerve paralysis.16

Temporal bone fractures are being divided into transverse and longitudinal, based on relationship of fracture line to axis of petrous ridge and otic capsule.17 However, majority of fractures are oblique and hence of mixed type. Facial nerve injuries occur in 30 to 50% cases of transverse fractures with labyrinthine and mastoid segments most commonly involved. Longitudinal fractures result in facial nerve injuries in 10 to 25% cases with perigeniculate region and tympanic segment most commonly involved.18

In acute facial paralysis, the predictive factors for surgical exploration are degeneration >90% within 6 days of onset of paralysis and immediate onset of facial paralysis.19 Goals to be achieved in surgical exploration are decompression of facial nerve to prevent ischemic injury, to remove bone fragments impinging on facial nerve, and to establish continuity in case of nerve transection. May et al20 recommended nerve repair within 30 days of injury. According to Quaranta et al,19 recovery of satisfactory facial nerve function can be achieved in only 75% patients treated 1 to 3 months after trauma.

To improve the neural function, lot of research is going on about the role of stem cells in regeneration of neurons, glial cells, and peripheral nerves.21 Hematopoietic stem cells have been seen to differentiate in vitro and in vivo into neurons, oligodendrocytes, and astrocytes and also into nerve cells along peripheral nerves to regenerate the damaged nerves and to achieve nerve continuity.22,23 In our study, stem cells were used along with facial nerve decompression to improve the functional consequences of traumatic facial nerve paralysis.

In our study, most patients were males and were in the age group of 20 to 30 years which was in agreement with largest study done on temporal bone fractures by Brodie and Thompson.16 The most common mode of injury was motor vehicle accidents; 75% patients had immediate onset of facial paralysis which was in accordance with study done by Glarner et al.24 Most of the patients had longitudinal fracture on HRCT temporal bone (Fig. 5). Half of the patients was complaining of hearing loss and tinnitus along with facial deviation as associated symptoms and similar observation had been made by Brodie and Thompson.16 None of our patients had tympanic membrane perforation.

On PTA, no significant difference was present in bone conduction between paralyzed side and normal side, whereas significant difference was present in air conduction between paralyzed and normal sides though the result was not statistically significant.

ENoG was done in all cases both preoperatively and postoperatively to assess for objective improvement (Figs. 6 and 7). Latency and amplitude were taken as assessment criteria though the amplitude is more robust for objective assessment. Percentage of intact fibers present preoperatively was compared with postoperative regeneration of facial nerve fibers after intervention. All patients in our study presented to us 3 to 4 months after the trauma, so the criteria of >90% degeneration within 6 days of injury on ENoG for surgical exploration could not be applied. So, the criteria of good objective response (>50% intact fibers) and poor objective response (50% and <50% intact fibers) were taken for our study. There was significant difference in average preoperative amplitude on paralyzed side (0.59 ± 0.36) and postoperative amplitude on paralyzed side after intervention (0.85 ± 0.50) (see Fig. 3). The significant statistical difference was present between preoperative percentage of intact fibers and postoperative percentage of regeneration of fibers (p π .041) (see Fig. 4) and also in preoperative poor objective response which got improved to good objective response after intervention (p < 0.046).

Figure 7.

Postoperative electroneuronography showing same configuration of curves on left and right sides with equal amplitudes.

The autologues bone marrow mononuclear stem cells in our study were harvested from aspirated blood from iliac crest of each patient and were then processed in well-equipped bone marrow laboratory. The processed stem cells were then cross-typed to check for MNC count and CD34+ cell count. The CD34+ count was varying from 1.69 × 106 to 3.54 × 107 in dispensed 5 mL disposable syringe while MNC count was varying from 1.51 × 108 to 2.32 × 109 in our study (as shown in Table 1). Volume of 0.2 mL was injected at the site of nerve transaction in each case. Positive correlation was seen between MNC count and CD34+ cell count injected in each case (Fig. 8). Research has demonstrated that transplanted mesenchymal stem cells can cause nerve regeneration due to property of plasticity at site of nerve transection, replacing lost or damaged nerve cells, rescuing defective nerve cells, and by reversing disease symptoms such as inflammation. Transplanted mesenchymal stem cells are known to express neuronal and glial markers indicating their competence to differentiate into glial cells or neurons.22 These cells can survive at transplanted site for more than 7 days after implantation making them a viable substrate for research purposes.25 Stem cells have been seen to play a supportive role in maintaining the viability or prolonging the function of surviving motor neurons.23

Table 1. Stem Cells Cellular Dose Given to Each Patient of Facial Nerve Paralysis.

| Patient Order | Volume of Suspension (mL) | Mononuclear Cells Count per Injection | CD34+ Count (%) | CD34+ Absolute Numbers | Volume of Suspension Injected at Injured Site (mL) | Mononuclears Cells Count Injected at Injured Site | CD34+ Cells Count at Injured Site |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3.0 | 1.33 × 109 | 1.63 | 2.16 × 107 | 0.2 | 8.86 × 107 | 1.44 × 106 |

| 2 | 3.3 | 5.03 × 108 | 1.15 | 5.78 × 106 | 0.2 | 3.05 × 107 | 3.50 × 105 |

| 3 | 4.0 | 2.32 × 109 | 1.53 | 3.54 × 107 | 0.2 | 1.16 × 108 | 1.77 × 106 |

| 4 | 3.0 | 7.74 × 108 | 1.70 | 1.31 × 107 | 0.2 | 5.16 × 107 | 8.73 × 105 |

| 5 | 4.0 | 4.35 × 108 | 0.47 | 2.04 × 106 | 0.2 | 2.17 × 107 | 1.02 × 105 |

| 6 | 3.0 | 4.04 × 108 | 1.59 | 6.42 × 106 | 0.2 | 2.69 × 107 | 3.21 × 105 |

| 7 | 3.0 | 1.51 × 108 | 1.12 | 1.69 × 106 | 0.2 | 1.0 × 107 | 1.12 × 105 |

| 8 | 2.0 | 2.49 × 108 | 1.10 | 2.73 × 106 | 0.2 | 2.49 × 107 | 2.73 × 105 |

Figure 8.

Positive correlation between mononuclear cell count and CD34+ cell count at injected site.

The clinical improvement in eye closure and facial deviation was assessed by utilizing modified House–Brackmann grading scale9 both preoperatively and postoperatively.

All of our patients presented to us 2 to 3 months after trauma after being operated for facial nerve decompression outside. Despite such late presentation, 87.5% of cases had good clinical recovery using our surgical modality while 12.5% patients had moderate clinical recovery. The clinical improvement seen at second follow-up was highly significant both for eye closure (p < 0.010) and for deviation of angle of mouth (p < 0.008) (Figs. 9 and 10). The success rate achieved using our surgical modality was far greater than any of the conventional surgical techniques described till date.

Conclusion

Facial nerve decompression with stem cell implantation appears to be a novel and promising surgical modality for facial nerve paralysis but a larger series with control group needs to be assessed before recommending this modality for facial nerve paralysis.

Summary

In view of clinical recovery achieved in our patients, facial nerve decompression and stem cell implantation appear to be a promising surgical modality in patients with long-standing facial nerve paralysis as compared with conventional facial nerve decompression alone.

Stem cell use on human body appears to be safe and without any adverse effects as seen in our study. Stem cells are being used nowadays in nerve injuries with significant improvement in the nerve function.

As a number of patients in our series were less, few more clinical series using this surgical modality need to be assessed before actual significance of this surgical modality can be validated.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Dr. Sahul Bharti for carrying out all the statistical analysis of our research work and helping us in the interpretation of results. We also acknowledge the contribution made by the patients enrolled in our study for their full cooperation in completing our research work. We are also thankful to the Government of India for providing funds for carrying out stem cell research activities in our institute.

References

- 1.Crosby E C, Dejonge B R. Experimental and clinical studies of the central connections and central relations of the facial nerve. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1963;72:735–755. doi: 10.1177/000348946307200310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carpenter M B. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins; 1976. Human Neuroanatomy. 7th ed. [Google Scholar]

- 3.May M, Klein S R. Differential diagnosis of facial nerve palsy. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1991;24(3):613–645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ellis J C, McCaffrey T V. Nerve grafting. Functional results after primary vs delayed repair. Arch Otolaryngol. 1985;111(12):781–785. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1985.00800140025003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Griffin J E, Altenau M M, Schaefer S D. Bilateral longitudinal temporal bone fractures: a retrospective review of seventeen cases. Laryngoscope. 1979;89(9 Pt 1):1432–1435. doi: 10.1002/lary.5540890908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kamerer D B. Intratemporal facial nerve injuries. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1982;90(5):612–615. doi: 10.1177/019459988209000520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McKennan K X, Chole R A. Facial paralysis in temporal bone trauma. Am J Otol. 1992;13(2):167–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Green J D, Shelton C, Brackmann D E. Surgical management of iatrogenic facial nerve injuries. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1994;111(5):606–610. doi: 10.1177/019459989411100511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.House J W, Brackmann D E. Facial nerve grading system. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1985;93(2):146–147. doi: 10.1177/019459988509300202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Esslen E. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1977. Investigation on the localization and pathogensis of meatolabyrinthine palsies. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fisch U. Surgery for Bell's palsy. Arch Otolaryngol. 1981;107(1):1–11. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1981.00790370003001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beck D L, Hall J W. Evaluation of the facial nerve via electroneuronography (ENoG) The Hearing J. 2001;54(3):36–44. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fisch U. Prognostic value of electrical tests in acute facial paralysis. Am J Otol. 1984;5(6):494–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nageris B, Hansen M C, Lavelle W G, Pelt F A Van. Temporal bone fractures. Am J Emerg Med. 1995;13(2):211–214. doi: 10.1016/0735-6757(95)90096-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Virapongse C, Bhimani S, Sarwar M. Philadelphia: 1987. Radiography of the abnormal ear. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brodie H A, Thompson T C. Management of complications from 820 temporal bone fractures. Am J Otol. 1997;18(2):188–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cannon C R, Jahrsdoerfer R A. Temporal bone fractures. Review of 90 cases. Arch Otolaryngol. 1983;109(5):285–288. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1983.00800190007002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wiet R J, Valvassori G E, Kotsanis C A, Parahy C. Temporal bone fractures. State of the art review. Am J Otol. 1985;6(3):207–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Quaranta A, Campobasso G, Piazza F, Quaranta N, Salonna I. Facial nerve paralysis in temporal bone fractures: outcomes after late decompression surgery. Acta Otolaryngol. 2001;121(5):652–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.May M, Sobol S M, Mester S J. Managing segmental facial nerve injuries by surgical repair. Laryngoscope. 1990;100(10 Pt 1):1062–1067. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199010000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haïk S, Gauthier L R, Granotier C. et al. Fibroblast growth factor 2 up regulates telomerase activity in neural precursor cells. Oncogene. 2000;19(26):2957–2966. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Naito Y, Nakamura T, Nakagawa T. et al. Transplantation of bone marrow stromal cells into the cochlea of chinchillas. Neuroreport. 2004;15(1):1–4. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200401190-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Svendsen C N, Langston J W. Stem cells for Parkinson disease and ALS: replacement or protection? Nat Med. 2004;10(3):224–225. doi: 10.1038/nm0304-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Glarner H, Meuli M, Hof E. et al. Management of petrous bone fractures in children: analysis of 127 cases. J Trauma. 1994;36(2):198–201. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199402000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matsuoka A J, Kondo T, Miyamoto R T, Hashino E. In vivo and in vitro characterization of bone marrow-derived stem cells in the cochlea. Laryngoscope. 2006;116(8):1363–1367. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000225986.18790.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]