Abstract

Background Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage represents a major source of morbidity following microvascular decompression (MVD) surgery. The objective of this study was to retrospectively assess whether complete versus incomplete reconstruction of the suboccipital cranial defect influences the incidence of CSF leakage following MVD.

Methods We reviewed the charts of 100 patients who consecutively underwent MVD for trigeminal neuralgia by two attending neurosurgeons between July 2004 and April 2010. Operative variables including incomplete or complete calvarial reconstruction, primary dural closure or dural closure with adjunct, and use of lumbar drainage were recorded. The effect of complete calvarial reconstruction on the incidence of postoperative CSF leakage was examined using a multivariate logistic regression model.

Results Of the 36 patients whose wound closure was reconstructed with a complete cranioplasty, 2 (5.6%) patients experienced a postoperative CSF leak. Of the 64 patients whose wound closure was augmented with an incomplete cranioplasty, 15 (23.4%) experienced a postoperative CSF leak. There was suggestive but inconclusive evidence that the risk of CSF leakage following MVD was smaller with complete reconstruction of calvarial defect than with incomplete reconstruction (two-sided p value = 0.059), after accounting for age, dural closure method, use of lumbar drainage, and previous MVD.

Conclusion Complete reconstruction of the suboccipital cranial defect decreases the risk of CSF leakage.

Keywords: cerebrospinal fluid leak, pseudomeningocele, suboccipital, craniectomy, microvascular decompression

Introduction

Microvascular decompression (MVD) is a surgical procedure for the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia that directly addresses pathologic compression of the trigeminal nerve via a retrosigmoid suboccipital approach.1 Despite progressive advances in surgical technique, complications with this procedure are still encountered. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage represents a major source of postoperative patient morbidity. In previous series, the incidence of CSF leakage following suboccipital craniotomy for various pathologies has been reported to range from 1.5 to 14.5% (Table 1).2,3,4,5,6,7,8 The objective of this study was to retrospectively assess whether variations in operative protocol influenced the incidence of CSF leakage following MVD.

Table 1. Previous Studies Documenting the Incidence of CSF Leakage Following MVD.

| Author | Intervention | Dural Closure | Bone Defect | Rate of CSF Leak |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barker et al, 1995 | MVD of CN VII | Muscle or fascial graft for “water-tight” dural closure as needed | Replacement with mesh or PMM | 19/782 (2.4%) |

| Barker et al, 1996 | MVD of CN V | Muscle or fascial graft for “water-tight” dural closure as needed | Replacement with mesh or PMM | 20/1336 (1.5%) |

| Jodicke et al, 1999 | MVD of CN V | NR | Replacement of bone flap alone | 1/8 (12.5%) |

| Broggi et al, 2000 | MVD of CN V | NR | Craniectomy alone | 24/250 (9.6%) |

| Linskey et al, 2008 | MVD of CN V | Fascial graft for “water-tight” dural closure as needed | Replacement with mesh or PMM | 1/36 (2.8%) |

| Jellish et al, 2008 | MVD of CN V | NR | NR | 2/37 (5.4%) |

| Dubey et al, 2009 | MVD of CN V, 7, or 9 | NR | NR | 16/110 (14.5%) |

Note: Methods of dural closure and calvarial flap replacement are described.

CN, cranial nerve; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; MVD, microvascular decompression; NR, not reported, PMM, polymethylmethacrylate.

Methods

From July 2004 to June 2009, one neurosurgeon (P.E.K.) at our institution performed 75 MVDs. Beginning in November 2008, operative protocol was changed from a standard retrosigmoid craniectomy without replacement of calvarial defect to a modified craniectomy in which the entire calvarial defect was reconstructed with methylmethacrylate following dural closure. The method of dural closure varied during this time period. From December 2006 to April 2010, the other neurosurgeon (J.S.N.) performed 25 MVDs. Closure by this neurosurgeon involved (1) the addition of harvested pericranial graft oversewn along the dural closure, (2) replacement of any removed piece of bone attached with small cranial plates, and (3) filling any remaining defect with a synthetic bone analogue (e.g., methylmethacrylate, calcium carbonate bone cement). We retrospectively reviewed the operative cases from July 2004 to April 2010 to analyze the effect of method of dural closure and degree of cranioplasty on incidence of CSF leakage.

Patient Population

Between July 2004 and April 2010, 100 patients underwent a suboccipital craniectomy or craniotomy for MVD surgery in the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia. The patient population was composed of 68 women and 32 men with ages ranging from 22 to 86 years and a mean of 55.6 years. Follow-up was available from 1 to 24 months. Complete cranioplasty was defined as complete replacement of the entire calvarial defect. This was done either with the bone flap and bone analogue together or the bone analogue alone filling the entire defect. An incomplete cranioplasty technique was defined as the incomplete reconstruction of the calvarial defect. This definition includes closure with bone flap alone, mesh alone, or nothing at all. The dura was often closed in conjunction with some type of adjunct material used to ensure approximation of tissue edges. Materials used as adjuncts in dural closure included: autologous pericranial graft and synthetic dural substitute. Additional epidural adjuncts included fibrin-based sealants (i.e., Tisseel [Baxter Healthcare Corp., Westlake Village, CA, USA], Evicel [OMRIX biopharmaceuticals Ltd., Ramat Gan, Tel Aviv, Israel]) and hydro-gel sealants (i.e., Duraseal [Confluent Surgical, Waltham, MA, USA]).

Surgical Procedure

All of the surgical procedures were performed via a retrosigmoid, suboccipital approach. Facial nerve function and hearing were monitored throughout the procedure.9 Following the induction of general anesthesia, the patient was placed in pins and moved to the lateral park bench position with side of the desired MVD placed up. A curvilinear, postauricular incision was made and suboccipital musculature was divided, exposing the lateral occiput and mastoid eminence.

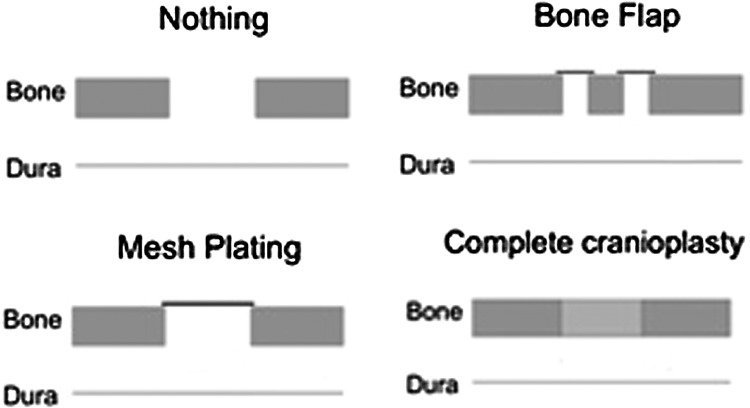

The following operative techniques for exposure of the transverse-sigmoid junction are described as follows. In all cases, the cranial defect created for the suboccipital approach measured ~3 cm in diameter. In some cases, pericranium was harvested before craniotomy to be used for primary dural closure later in the case. Exposure of the cerebellopontine angle proceeded after adequate CSF drainage. The trigeminal nerve and offending vessels were identified, and the nerve decompressed in a manner described in previous publications.1,10,11 Following MVD and Teflon (DuPont Co., Wilmington, DE) pad placement, the durotomy was closed using 4-0 Nurolon suture (Ethicon Inc., Somerville, NJ, USA). Methods for dural closure included either primary closure or suturing with either synthetic dural analogue or pericranium. Duraseal (Confluent Surgical, Waltham, MA, USA) or fibrin glue was occasionally used to supplement the site of dural closure whether the cranial defect was filled or not. The cranial defect was reconstituted as follows: (1) no cranioplasty: galea and skin closed with sutures; (2) incomplete cranioplasty: remaining bone flap reattached with small cranial plate and screws without filling any defect or cranial mesh applied over the surface of the skull without filling the defect; or (3) complete cranioplasty: complete reconstruction of the cranial defect. All but the last option were considered as an incomplete closure of the cranial defect. Following calvarial supplementation, the wound is then closed in multiple layers in the standard fashion.

Other Methods for Prevention of Postoperative CSF Fistulas

In addition to the above-mentioned intraoperative methods, a lumbar drain has recently been used by one of the authors (J.S.N.). The lumbar drain is inserted following induction of anesthesia but before positioning and is used for intraoperative cerebellar relaxation. The drain is kept in place until patients are discharged from the hospital (usually postoperative day 2). This method was employed in the most recent 11 patients of this author included in this study.

Outcome Analysis

A diagnosis of CSF leakage was rendered in all patients with any clinical documentation of postoperative rhinorrhea, otorrhea, and/or significant amount of fluid leakage from the incision. A pseudomeningocele was said to be present when documentation of a significant fluid collection was present beneath the incision without any sign of fluid leaking from the incision or presence of rhinorrhea. Follow-up in every patient described in this study was 6 weeks or longer.

Statistical Analysis

Pearson's chi-square test and Wilcoxon test were used to compare the baseline characteristics between complete and incomplete reconstruction groups. We employed a multivariable generalized linear regression model to examine the effect of complete reconstruction on the incidence of CSF leakage. Age, type of dural closure method, previous MVD, and lumbar drain were adjusted in the model using a propensity score method. The propensity score of a patient is the probability of receiving complete reconstruction given these potential confounding covariates. A similar approach was also used to assess the effect of complete reconstruction in the time to CSF leak (with an identity link function) and the incidences of pseudomeningocele formation, aseptic meningitis, and wound infection. Confidence intervals and p values on the estimates were calculated based on Wald's test. All the analysis was performed using R 2.10.1 (R. Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).12

Results

Demographic and surgical characteristics were statistically compared between complete and incomplete reconstruction cohorts (Table 2). The mean age of the complete reconstruction and incomplete reconstruction cohorts was 53 years (standard deviation ± 13) and 57 years (standard deviation ± 14), respectively. The percentage of patients who underwent a previous MVD was 3 and 17% in each cohort, respectively. The proportion of patients who had received prior radiation was 8 and 12% in each cohort, respectively. The percentage of patients who underwent lumbar drain placement was 31 and 0% in each cohort, respectively. The percentage of patients with incomplete reconstruction who underwent primary dural closure was 80%, while most of the patients with complete reconstruction underwent dural closure augmented with a pericranial graft.

Table 2. Demographic and Surgical Characteristics of Each Method.

| Incomplete (n = 64) | Complete (n = 36) | p Valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (year) | 56.7 ± 13.8 | 52.8 ± 13.3 | 0.279 |

| Previous MVD | 17% (11) | 3% (1) | 0.033 |

| Dural closure method | <0.001 | ||

| Primary dural closure | 80% (51) | 28% (10) | |

| Pericranium graft | 0% (0) | 69% (25) | |

| Synthetic dural analogue | 20% (13) | 3% (1) | |

| Lumbar drain | 0% (0) | 31% (11) | <0.001 |

| Prior radiation | 12% (8) | 8% (3) | 0.523 |

Note: Numbers after percentages are frequencies.

Wilcoxon test was used for age; Pearson test for other variables.

MVD, microvascular decompression.

Incidences of CSF leak, pseudomeningocele formation, and wound infection among 100 MVD patients subgrouped by different types of calvarial reconstruction are listed in Table 3. Calvarial reconstruction with nothing, bone flap, and mesh plating were combined and designated as incomplete reconstruction. Only when the calvarial defect was completely reconstructed, was the closure designated a complete cranioplasty. Schematic depictions of the reconstruction methods are shown in Fig. 1.

Table 3. Case Numbers of CSF Leak and Other Complications Following MVD.

| Method of Reconstruction of Calvarial Defect | Number of Patients | CSF Leak | Pseudomeningocele Formation | Wound Infection |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incomplete reconstruction of calvarial defect | ||||

| Nothing | 42 | 24% (10) | 21% (9) | 10% (4) |

| Bone flap | 14 | 21% (3) | 14% (2) | 7% (1) |

| Mesh plating | 8 | 25% (2) | 0% (0%) | 0% (0) |

| Complete reconstruction of calvarial defect | ||||

| Complete cranioplasty | 36 | 6% (2) | 3% (1) | 3% (1) |

| Total | 100 | 17% (17) | 12% (12) | 6% (6) |

Note: Numbers after percentages are frequencies.

CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; MVD, microvascular decompression.

Figure 1.

Representations of the three types of incomplete reconstruction and one type of complete reconstruction.

Of the 100 patients who underwent MVD surgery between 2004 and 2010, a complete cranial reconstruction was performed in 36 of the 100 patients. In this group, 2 (5.6%) patients had CSF leakage (Table 3). Of the 64 patients where an incomplete cranial reconstruction was performed, 15 (23.4%) patients had CSF leakage. After accounting for age, dural closure method, previous MVD, as well as lumbar drain placement, there was suggestive but inconclusive evidence that the risk of a patient having CSF leakage following MVD was smaller with complete reconstruction of calvarial defect than with incomplete reconstruction (two-sided p value = 0.059) (Table 4). The odds of CSF leakage following complete reconstruction were estimated to be 12% the odds of CSF leakage for patients with incomplete reconstruction (95% confidence interval 1 to 108%). Among the patients who suffered from CSF leakage after MVD, the time (mean ± SD) to CSF leak occurrence was 21.5 ± 6.1 days in the complete reconstruction group versus 8.3 ± 6.1 days in the incomplete reconstruction group. After accounting for age, dural closure method, previous MVD, and lumbar drain placement, complete reconstruction was associated with 6.8 days longer in the time to CSF leak, but this was not statistically significant (two-sided p value = 0.309).

Table 4. Effects of Complete Reconstruction of Suboccipital Cranial Defects on CSF Leak and Other Clinical Outcomes.

| Clinical Outcomes | Odds Ratio | p Value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| CSF leakagea | 0.123 | 0.059 | (0.014, 1.082) |

| Pseudomeningocelea | 0.261 | 0.219 | (0.031, 2.217) |

| Wound infectionb | 0.340 | 0.415 | (0.007, 3.220) |

| Estimate | p value | 95% CI | |

| Time to CSF leak (day)c | 6.8 | 0.309 | (−7.0, 20.5) |

Logistic regression adjusted for age, dural closure method, previous MVD, and lumbar drain.

Fisher's exact test.

Among patients with CSF leak, linear regression adjusted for age, dural closure method, previous MVD, and lumbar drain.

CI, confidence interval; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid.

The incidence of pseudomeningocele formation was 2.8% (1/36) in patients with a complete cranioplasty and 17.2% (11/64) in patients with an incomplete cranioplasty (Table 3). After accounting for age, closure method, previous MVD, as well as lumber drain practice, the odds of having pseudomeningocele formation after MVD for patients with complete reconstruction type were estimated to be 26% of the odds of pseudomeningocele formation for patients with incomplete reconstruction (95% confidence interval 3 to 222%). However, the results were not statistically significant (two-sided p value = 0.219).

We also observed 2.8% (1/36) of patients with complete cranioplasty had wound infection versus 7.8% (5/64) incompletely reconstructed patients suffered from this complication. The difference is not statistically significant (two-sided p value = 0.415).

In addition to accounting for use of lumbar drain in the propensity score, an analysis was conducted on the incidence of CSF leak in those in the complete reconstruction group who did and did not receive a lumbar drain. Among the 36 patients who underwent complete reconstruction, 11 had lumbar drain and 25 did not. Among the 11 who received a lumbar drain, 1 suffered from a CSF leak and among the 25 who did not have lumbar drain, 1 suffered from a CSF leak. The p value is 0.524 indicating a nonsignificant relationship (Fisher's exact test). Future analysis of this association with greater power is warranted.

Discussion

CSF leakage is a significant and potentially preventable cause of morbidity following retrosigmoid craniotomy. When present, this complication significantly increases the risk of bacterial meningitis and often requires costly methods of treatment that include prolonged hospital stay, lumbar drainage, and/or ventriculoperitoneal shunt insertion.13 The incidence of CSF leakage following a retrosigmoid craniotomy is thought to be related to the ability to tightly approximate the dural edges during closure. When CSF egresses through the durotomy, leakage through the skin may be prevented by the additional superficial layers of closure. However, CSF which escapes through the dural layer but does not escape through skin closure can still result in problematic pseudomeningocele formation. In animal models, CSF in contact with soft tissue has been shown to result in degeneration of muscle fibers, dystrophic calcification, fat necrosis, and coagulation necrosis.14 Moreover, subcutaneous collections of CSF can potentially egress into incompletely obliterated mastoid air cells and leak from the middle ear into the eustachian tube, resulting in CSF rhinorrhea.1 These considerations underscore the importance of prevention of CSF leakage.

In reviewing methods for prevention of CSF leakage, the vast majority of studies have advocated “water-tight” closure at the dural level. Methods to achieve this goal have included plugging of dural closure with autologous material (e.g., muscle or fat), use of synthetic materials for dural augmentation, or epidural augmentation with hydro-gel or fibrin sealants.15,16,17,18 These methods have been reported to decrease the incidence of postoperative CSF leak with varying rates of success (Table 5). However, not all reports are in agreement. A study by Steinbok et al failed to demonstrate a difference in the incidence of CSF leakage in patients whose dural closure was augmented with dural grafts or tissue glue. In contrast, data indicated a nonsignificant trend toward increased risk of CSF leakage and pseudomeningocele formation in these patients.19 Other authors have repudiated the quest for “water-tight” dural closure—stating that CSF leakage persists through pinholes associated with suture placement even when “water-tight” dural closure was thought to have been achieved.15,20

Table 5. Studies Using Varying Methods to Prevent CSF Leaks Following Posterior Fossa Surgery.

| Author | Intervention | CSF Leak in Control Group | CSF Leak in Experimental Group | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Li et al | Artificial dura mater post-MVD surgery | 6/114 (5%) | 0/103 (0%) | Posterior fossa |

| Park et al | “Plugging muscle” method | N/A | 2/678 (0.3%) | Posterior fossa |

| Than et al | Dural sealant (fibrin glue) | 10/100 (10%) | 2/100 (2%) | Posterior fossa |

| Black et al | Fat grafts | N/A | 1/150 (0.7%) | Posterior fossa |

CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; MVD, microvascular decompression; N/A, not available.

The association between calvarial defect reconstruction and decreased rate of postoperative CSF leakage has previously received attention in transsphenoidal procedures. In a recent study, Leng et al reported that using a method of closure known as the “gasket-seal” in endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal surgeries decreased the risk of CSF leakage in select procedures.21 This technique involved harvesting a piece of fascia lata larger than the bone defect, laying it over the defect, and then wedging a bone into the defect to create a tight seal. While other authors have advocated filling the calvarial defect completely in retrosigmoid craniotomy to decrease headaches after MVD,22 to the authors' knowledge, impact of cranioplasty on incidence of CSF leakage has never been formally analyzed.

Extensive retrospective data analysis from the present study indicates that complete reconstruction of the calvarial defect appears to decrease the risk of CSF leakage and pseudomeningocele formation following retrosigmoid craniotomy. However, the putative mechanism underlying this decrease in CSF egress remains uncertain. It is possible that the use of complete cranial reconstruction enhances the function of other dural closure techniques via a buttressing effect. Pascal's law, known as the principle of transmission of fluid pressure, states that pressure exerted anywhere in a confined incompressible fluid is transmitted equally in all directions throughout the fluid. Thus, postoperative increases in intrathecal pressures are inexorably transmitted to the site of dural closure—often the point of least resistance. Complete cranial reconstruction hypothetically “buttresses” these sites of dural closure—preventing migration of epidural adjuncts. Park et al,16 who advocated a “plugging muscle” method in prevention of CSF leaks following MVD, stated that cranioplasty with bone cement compressed the muscle pieces and helped to buttress and plug the dural defect. In addition to a potential buttressing effect, it is alternatively possible that complete flap reconstruction provides something of an obstruction to CSF flow at physiological pressures in its own right—independent of method of dural closure.

Limitations

This study is limited in that it is a retrospective analysis. Other variables that may have influenced the risk of CSF leak—including poor wound healing (malnutrition, diabetes mellitus, concurrent glucocorticoid administration) and factors relating to possibly underlying hydrocephalus—were not tracked, possibly confounding the analysis. Also, these surgical results have been pooled by two neurosurgeons at a single institution—as a result, individual variations in operative protocol unrelated to the above discussion might also potentially confound data analysis.

Conclusion

Complete reconstruction of the suboccipital cranial defect appears to decrease the risk of CSF leakage and pseudomeningocele formation.

References

- 1.Elias W J, Burchiel K J. Microvascular decompression. Clin J Pain. 2002;18(1):35–41. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200201000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barker F G, Jannetta P J, Bissonette D J, Shields P T, Larkins M V, Jho H D. Microvascular decompression for hemifacial spasm. J Neurosurg. 1995;82(2):201–210. doi: 10.3171/jns.1995.82.2.0201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barker F G, Jannetta P J, Bissonette D J, Larkins M V, Jho H D. The long-term outcome of microvascular decompression for trigeminal neuralgia. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(17):1077–1083. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199604253341701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jödicke A, Winking M, Deinsberger W, Böker D K. Microvascular decompression as treatment of trigeminal neuralgia in the elderly patient. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 1999;42(2):92–96. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1053379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Broggi G, Ferroli P, Franzini A, Servello D, Dones I. Microvascular decompression for trigeminal neuralgia: comments on a series of 250 cases, including 10 patients with multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;68(1):59–64. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.68.1.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Linskey M E, Ratanatharathorn V, Peñagaricano J. A prospective cohort study of microvascular decompression and Gamma Knife surgery in patients with trigeminal neuralgia. J Neurosurg. 2008;109(Suppl):160–172. doi: 10.3171/JNS/2008/109/12/S25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jellish W S, Benedict W, Owen K, Anderson D, Fluder E, Shea J F. Perioperative and long-term operative outcomes after surgery for trigeminal neuralgia: microvascular decompression vs percutaneous balloon ablation. Head Face Med. 2008;4:11. doi: 10.1186/1746-160X-4-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dubey A, Sung W S, Shaya M. et al. Complications of posterior cranial fossa surgery—an institutional experience of 500 patients. Surg Neurol. 2009;72(4):369–375. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Møller A R, Jannetta P J. Monitoring facial EMG responses during microvascular decompression operations for hemifacial spasm. J Neurosurg. 1987;66(5):681–685. doi: 10.3171/jns.1987.66.5.0681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hitotsumatsu T Matsushima T Inoue T Microvascular decompression for treatment of trigeminal neuralgia, hemifacial spasm, and glossopharyngeal neuralgia: three surgical approach variations: technical note Neurosurgery 20035361436–1441., discussion 1442–1443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sindou M P Microvascular decompression for primary hemifacial spasm. Importance of intraoperative neurophysiological monitoring Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2005147101019–1026., discussion 1026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.R Development Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing, reference index version 2.01.1 Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2011. Available at: http://www.r-project.org [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grotenhuis J A Costs of postoperative cerebrospinal fluid leakage: 1-year, retrospective analysis of 412 consecutive nontrauma cases Surg Neurol 2005646490–493., discussion 493–494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Babuccu O, Kalayci M, Peksoy I, Kargi E, Cagavi F, Numanoğlu G. Effect of cerebrospinal fluid leakage on wound healing in flap surgery: histological evaluation. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2004;40(3):101–106. doi: 10.1159/000079850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li N, Zhao W G, Pu C H, Shen J K. Clinical application of artificial dura mater to avoid cerebrospinal fluid leaks after microvascular decompression surgery. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 2005;48(6):369–372. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-915629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park J S Kong D S Lee J A Park K Intraoperative management to prevent cerebrospinal fluid leakage after microvascular decompression: dural closure with a “plugging muscle” method Neurosurg Rev 2007302139–142., discussion 142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Than K D Baird C J Olivi A Polyethylene glycol hydrogel dural sealant may reduce incisional cerebrospinal fluid leak after posterior fossa surgery Neurosurgery 2008631, Suppl 1ONS182–ONS186., discussion ONS186–ONS187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Black P. Cerebrospinal fluid leaks following spinal or posterior fossa surgery: use of fat grafts for prevention and repair. Neurosurg Focus. 2000;9(1):e4. doi: 10.3171/foc.2000.9.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steinbok P Singhal A Mills J Cochrane D D Price A V Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak and pseudomeningocele formation after posterior fossa tumor resection in children: a retrospective analysis Childs Nerv Syst 2007232171–174., discussion 175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kabuto M, Kubota T, Kobayashi H, Handa Y, Tuchida A, Takeuchi H. MR imaging of cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea following the suboccipital approach to the cerebellopontine angle and the internal auditory canal: report of the two cases. Surg Neurol. 1996;45(4):336–340. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(95)00263-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leng L Z, Brown S, Anand V K, Schwartz T H. “Gasket seal” watertight closure in minimal access endoscopic skull base surgery. Neurosurgery. 2008;62(5 Suppl):ONSE342–ONSE343. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000326017.84315.1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Silverman D A, Hughes G B, Kinney S E, Lee J H. Technical modifications of suboccipital craniectomy for prevention of postoperative headache. Skull Base. 2004;14(2):77–84. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-828698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]