Abstract

Heart malformations are common congenital defects in humans. Many congenital heart defects involve anomalies in cardiac septation or valve development, and understanding the developmental mechanisms that underlie the formation of cardiac septal and valvular tissues thus has important implications for the diagnosis, prevention and treatment of congenital heart disease. The development of heart septa and valves involves multiple types of progenitor cells that arise either within or outside the heart. Here, we review the morphogenetic events and genetic networks that regulate spatiotemporal interactions between the cells that give rise to septal and valvular tissues and hence partition the heart.

Keywords: Signaling, Cardiac septation, Congenital heart disease, Heart development, Transcription, Valve development

Introduction

A mature mammalian heart has four valves and four chambers, with the wall of each chamber consisting of three tissue layers: endocardium, myocardium and epicardium (Fig. 1). The cardiac chambers and valves are organized such that they separate systemic from pulmonary circulation and ensure directional blood flow. The formation of these structures requires multiple cell types and complex morphogenetic processes, which often go awry in the developing human fetus. Heart malformations account for as many as 30% of embryos or fetuses lost before birth (Hoffman, 1995), and the incidence of heart defects in live births varies from 0.4% to 5% in different studies, depending on the severity of heart defects included in the statistics (Hoffman and Kaplan, 2002). On top of these statistics, another 2% of newborns have bicuspid aortic valves (BAVs; see Glossary, Box 1) or other defects (Hoffman and Kaplan, 2002), which may cause significant morbidity and mortality later in life (Brickner et al., 2000a). Congenital heart malformations, therefore, constitute an important medical issue challenging our society.

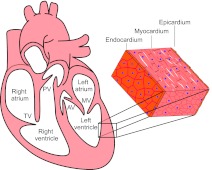

Fig. 1.

The structure of a mammalian heart. A mature mammalian heart contains four chambers (right atrium, left atrium, right ventricle, left ventricle) and four valves (pulmonary valve, PV; tricuspid valve, TV; atrial valve, AV; mitral valve, MV). The wall of each chamber consists of three tissue layers: endocardium, myocardium and epicardium.

Box 1. Glossary

Atrial septal defect (ASD). A congenital heart defect resulting from incomplete atrial septation.

Atrioventricular canal (AVC). The junction between developing atria and ventricles.

Atrioventricular cushions. The four endocardial cushions located at the AV canal: superior, inferior, left-lateral and right-lateral cushions.

Atrioventricular septal defect (AVSD). A congenital heart defect resulting from incomplete septation of the atrioventricular canal.

Bicuspid aortic valve (BAV). A congenital heart defect in which the aortic valve has only two cusps. The term BAV is also used broadly to describe any malformation of the aortic valve cusps.

Dorsal mesenchymal protrusion (DMP). A mesenchymal tissue that protrudes into the atrial chamber through the dorsal mesocardium.

Double-outlet right ventricle (DORV). A congenital heart defect in which both aorta and pulmonary trunk arise from the right ventricle.

First heart field (FHF). A population of mesodermal cells that form the cardiac crescent located in splanchnic mesoderm underlying the head folds. Progenitors of the FHF give rise to myocardium of the left ventricle, part of the right ventricle and part of the atria.

Interruption of the aortic arch (IAA). A congenital heart defect in which a segment of the aortic arch is occluded or absent.

Mesenchymal cap (MC). A mesenchymal tissue that caps the growing (inferior) edge of the primary atrial septum.

Outflow tract (OFT). The outflow region of the embryonic heart that develops into the left and right ventricular outlets, as well as the aorta and pulmonary trunk.

Overriding aorta (OA). A congenital heart defect in which the aortic root connects with both the left and right ventricle and receives blood from both ventricles.

Patent ductus arteriosus (PDA). A congenital heart defect in which the ductus arteriosus fails to close after birth.

Persistent truncus arteriosus (PTA). A congenital heart defect in which the aorta fails to separate from the pulmonary trunk, resulting in a single arterial trunk that emerges from the ventricles.

Pulmonary stenosis (PS). A congenital heart defect in which the pulmonary valve is malformed, causing narrowing of the pulmonary trunk and hindrance of blood flow.

Secondary heart field (SHF). A population of mesodermal cells located medially and posteriorly to the first heart field, then behind the heart tube, and extending into pharyngeal mesoderm as the embryo develops. Progenitor cells of the SHF give rise to myocardium of the right ventricle, cardiac outflow tract, and part of the left ventricle and atria.

Tetralogy of Fallot (TOF). A congenital heart defect characterized by right ventricular outflow tract obstruction, right ventricular hypertrophy, ventricular septal defect and overriding aorta.

Total or partial anomalous pulmonary venous return (TAPVR or PAPVR). A congenital heart defect in which pulmonary veins are misconnected and drained into the systemic venous circulation.

Transposition of the great arteries (TGA). A congenital heart defect in which the right ventricle connects to the aorta, and the left ventricle connects to the pulmonary trunk.

Tricuspid atresia (TA). A congenital heart defect in which the tricuspid valve is missing, hence blocking the blood flow from right atrium to right ventricle.

Ventricular septal defect (VSD). A congenital heart defect resulting from incomplete ventricular septation

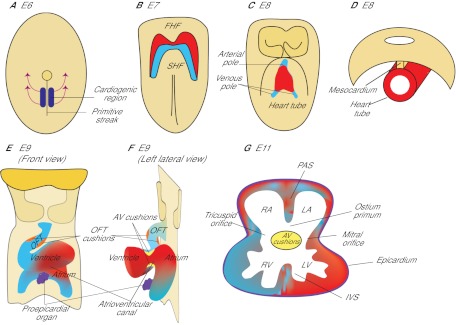

The heart of developing embryos originates from mesodermal cells located in the anterior part of the primitive streak (Lawson et al., 1991; Tam et al., 1997) (Fig. 2). During gastrulation, these cardiac mesodermal cells migrate from the streak to the splanchnic mesoderm underlying the head folds to form cardiac crescent (the first heart field, FHF; see Glossary, Box 1) (Abu-Issa and Kirby, 2007; Vincent and Buckingham, 2010) (Fig. 2A,B). As the embryo grows, the crescent of the FHF fuses in the ventral midline, forming a trough-like structure, which then closes dorsally to form a primitive heart tube (Fig. 2C). The heart tube is suspended from the body wall by dorsal mesocardium (Fig. 2D), and the tube elongates on both the arterial and venous poles via the addition of progenitor cells originating from the secondary heart field (SHF; see Glossary, Box 1), which lies medially and posteriorly to the crescent (Kelly et al., 2001; Mjaatvedt et al., 2001; Waldo et al., 2001; Cai et al., 2003). Concurrent with heart tube elongation, the dorsal mesocardium dissolves except at the poles, liberating the majority of the heart tube and allowing it to undergo rightward looping. The looped heart tube, composed of an inner endocardial lining and an outer myocardial layer, is segmented into the atrium, the atrioventricular canal (AVC; see Glossary, Box 1), the ventricle and the outflow tract (OFT; see Glossary, Box 1) (Fig. 2E). In the lumen of the AVC and proximal OFT, local tissue swellings, termed endocardial cushions, are formed by the accumulation of abundant extracellular matrix (cardiac jelly) in between the endocardium and myocardium (Fig. 2F). These endocardial cushions are subsequently populated by mesenchymal cells that descend from the endocardium. In addition, within the lumen of the distal OFT, local tissue swellings (termed truncal cushions) arise and are later populated by mesenchymal cells originating from the neural crest. While the cushions are developing, a sheath of cells, which originate from the proepicardial organ, grows over the myocardium of the heart tube to form the outermost epicardial layer of the heart (Fig. 2E-G). Later in development, the atrial and ventricular chambers divide into two atria (left and right) and two ventricles (left and right), forming a prototypic four-chamber heart (Fig. 2G). Along with chamber septation, the AVC separates into left (mitral) and right (tricuspid) orifices, forming ventricular inlets that connect the respective atrium to the ventricle. The outflow tract divides into the left and right ventricular outlets that connect the left and right ventricle, respectively, to the aorta and pulmonary trunk. These septation events segregate the systemic from pulmonary circulation. In addition, the AVC endocardial cushions develop into atrioventricular (mitral and tricuspid) valves, whereas the OFT endocardial cushions give rise to semilunar (aortic and pulmonic) valves (Fig. 1). The formation of heart valves ensures that blood flows in one direction from the atria to ventricles and then to the arteries.

Fig. 2.

The formation of a mouse heart. (A) Ventral view of a mouse embryo at E6. The heart originates from mesodermal cells in the primitive streak. During gastrulation, mesodermal cardiac progenitor cells migrate to the splanchnic mesoderm to form the cardiac crescent. (B) Ventral view at E7. One subset of cardiac progenitors forms a horseshoe-shaped cardiac crescent (the first heart field, FHF; red). Another subset of cardiac progenitor cells forms the secondary heart field (SHF; blue), which is located posteriorly and medially to the FHF. (C) Ventral view at E8. Cells in the FHF merge in the midline to form the heart tube, which then elongates on both arterial and venous poles via the addition of progenitor cells from the SHF. (D) Transverse section at E8. The developing heart tube is suspended from the body wall by the dorsal mesocardium, which later dissolves except at the poles of heart tube, allowing the tube to loop rightward. (E,F) Ventral (E) and left lateral (F) views at E9. The looped heart tube contains four anatomical segments: atrium, atrioventricular canal, ventricle and outflow tract (OFT). Within the AVC and OFT, AV cushions (yellow) and OFT cushions (orange) develop. The proepicardial organ (purple) houses epicardial progenitors that later migrate to the heart and give rise to the epicardium. (G) Transverse section at E11. At this stage, the heart is partially partitioned by the primitive atrial septum (PAS), interventricular septum (IVS) and atrioventricular cushions (AV cushions) into a prototypic four-chamber heart. The AVC is divided into tricuspid and mitral orifices, forming ventricular inlets that connect the respective atrium to the ventricle. The opening between the PAS and AVC is the ostium primum. RA, right atrium; LA, left atrium; RV, right ventricle; LV, left ventricle.

Multiple cells of distinct developmental origins contribute to the formation of a heart. Lineage tracing and clonal analyses in mice show the existence of two distinct myocardial lineages arising separately from the FHF and SHF. The FHF lineage contributes primarily to the myocardium of the left ventricle (Buckingham et al., 2005; Srivastava, 2006), whereas the SHF lineage contributes to the myocardium of the atria (Cai et al., 2003; Galli et al., 2008), right ventricle and outflow tract (Kelly et al., 2001; Cai et al., 2003; Zaffran et al., 2004; Verzi et al., 2005). By contrast, the epicardium arises from the proepicardial organ, which is located near the venous pole of the heart tube and originates from the coelomic mesenchyme of septum transversum (Männer et al., 2001) (Fig. 2E). Cells in the epicardium give rise to mesenchymal cells that migrate into the myocardium and differentiate into fibroblasts and coronary smooth muscle cells (Merki et al., 2005). The origin of endocardium, however, has been controversial: the endocardium may arise from the heart fields or vascular endothelial progenitors (Harris and Black, 2010; Vincent and Buckingham, 2010; Milgrom-Hoffman et al., 2011). The mesenchyme of cushions arises from two distinct origins. Endocardial cushions in the AVC and proximal OFT lumen derive their mesenchyme from the local endocardium that overlies the cushions (Eisenberg and Markwald, 1995), whereas the distal OFT cushions are populated by mesenchymal cells that migrate from the distant neural crest (Jiang et al., 2000).

Here, we review the interactions between these different progenitor cells and their derivatives that are essential for cardiac septation and valve development. We also highlight the key signaling pathways that are known to regulate cardiac septation and valve development.

Cardiac chamber septation and valve formation

Septation of the primitive cardiac chambers, the AVC and the OFT is necessary for forming a four-chamber heart. The morphogenic events that direct cardiac septation and valve development are described below.

Atrioventricular septation

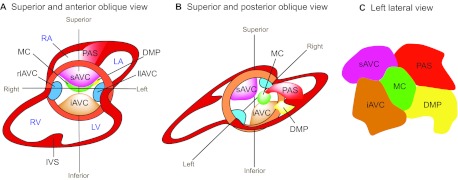

Four mesenchymal tissues are required for atrial and AVC septation: the superior and inferior atrioventricular (AV) endocardial cushions (atrioventricular cushions; see Glossary, Box 1), the mesenchymal cap (MC; see Glossary, Box 1), and the dorsal mesenchymal protrusion (DMP; see Glossary, Box 1) (Webb et al., 1998; Snarr et al., 2008) (Fig. 3). The AV cushions derive their mesenchyme from the endocardium through a cellular process called epithelial-to-mesenchymal transformation (EMT). During EMT, a subset of endocardial cells delaminates from the surface epithelium and transdifferentiates into mesenchymal cells, which migrate into the cardiac jelly and proliferate to cellularize the cushions (Eisenberg and Markwald, 1995). The MC, which envelops the growing edge of a muscular atrial septum, also arises through EMT from the endocardium overlying the cap (Snarr et al., 2008). Conversely, the mesenchyme of DMP comes from the SHF, which gives rise to cells that migrate through the dorsal mesocardium and bulge into the atrial chamber as a mesenchymal protrusion (Snarr et al., 2007a; Snarr et al., 2008).

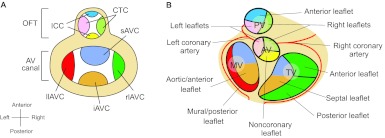

Fig. 3.

Endocardial cushion development. (A,B) Superior and anterior oblique view (A) and superior and posterior oblique view (B) of the heart. The superior and inferior atrioventricular cushions (sAVC and iAVC) are the two major cushions that develop in the central portion of the AVC. Two minor cushions, left and right lateral AV cushions (llAVC and rlAVC), form laterally at the AVC. The mesenchymal cap (MC) is a tissue that caps the leading edge of primary atrial septum (PAS) that grows from the atrial roof towards the AV canal. The dorsal mesenchymal protrusion (DMP) protrudes from the dorsal mesocardium into the atrial chamber. RA, right atrium; LA, left atrium; RV, right ventricle; LV, left ventricle; IVS, interventricular septum. (C) The composition of the atrial septum (left lateral view).

The mesenchyme of superior and inferior AV cushions fuses at the AV canal, dividing the canal into mitral and tricuspid orifices that form ventricular inlets (Fig. 2G, Fig. 3A,B). Meanwhile, a muscular septum (the primary atrial septum) grows from the atrial roof towards the AVC, with the MC at its leading edge. This muscular outgrowth partially septates the atrial chamber and leaves an opening (the ostium primum) between the MC and the AV canal (Fig. 2G). The MC then merges anteriorly with the AV cushions and posteriorly with the DMP to seal the ostium primum (Wessels et al., 1996; Schroeder et al., 2003; Wessels and Sedmera, 2003; Mommersteeg et al., 2006) (Fig. 3B,C). These mesenchymal tissues are later muscularized to form sturdy septum. While the ostium primum is closing, the upper margin of the primary atrial septum dissolves, creating a second opening (the ostium secundum) between the right and left atria. The ostium secundum is later sealed by a muscular septum (the secondary atrial septum), which is formed by part of the atrial roof that folds inward. The primary and secondary atrial septum then fuses to complete the septation of atrial chamber (Anderson et al., 2003a).

Within the ventricular chamber, an interventricular muscular septum emerges and grows superiorly to fuse with AV cushions, dividing the ventricular chamber into left and right ventricles (Fig. 2G, Fig. 3A) (Anderson et al., 2003a; Moorman et al., 2003). This muscular septum also connects with OFT cushions to separate the ventricular outlets. Abnormal chamber septation results in congenital heart diseases, including atrial septal defects (ASDs), ventricular septal defects (VSDs), and atrioventricular septal defects (AVSDs) (see Glossary, Box 1). These defects cause abnormal cardiac shunting and may lead to congestive heart failure (Brickner et al., 2000a).

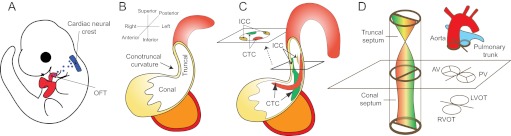

Outflow tract septation

Septation of the cardiac OFT requires neural crest cells (NCCs) of neuroectodermal origin, as well as truncal and conal cushions situated in the distal and proximal OFT (Fig. 4A-C). Early in development, a group of NCCs delaminates from the neuroectodermal junction of rhombomeres 6-8 at the hindbrain (Kirby et al., 1983), traverses the pharyngeal arches and secondary heart field, and migrates into the distal OFT (Fig. 4A). The NCCs that reach the heart become the mesenchyme of truncal cushions (Fig. 4C). Subsequently, the mesenchymal truncal cushions (the right-superior and left-inferior cushions) fuse to form aortopulmonary septum, dividing the distal OFT into the aorta and pulmonary trunk (Jiang et al., 2000; Li et al., 2000) (Fig. 4D). By contrast, at the proximal OFT, the endocardium, through EMT, gives rise to the mesenchyme of conal cushions. The mesenchymal conal cushions (the right-posterior and left-anterior cushions) then merge to form a conal septum, separating the proximal OFT into the right and left ventricular outlets (Anderson et al., 2003b) (Fig. 4C,D). The ventricular outlets are aligned to the arteries by the connection of conal and truncal cushions and to the ventricles by the fusion of conal cushions with the interventricular septum. Misaligned or incomplete OFT septation leads to a variety of congenital heart defects, including overriding aorta (OA; see Glossary, Box 1), double-outlet right ventricle (DORV; see Glossary, Box 1), tetralogy of Fallot (TOF; see Glossary, Box 1), transposition of great arteries (TGA; see Glossary, Box 1) and persistent truncus arteriosus (PTA; see Glossary, Box 1) (Brickner et al., 2000b). These defects can cause mixing of arterial with venous blood, leading to cyanosis and/or heart failure.

Fig. 4.

Septation of the cardiac outflow tract. (A) Left lateral view of an E10 mouse embryo. The neural crest at rhombomere 6-8 gives rise to cells (blue) that migrate to and colonize the distal cardiac outflow tract (OFT). (B) The cardiac OFT contains conal (proximal) and truncal (distal) cushions. The boundary between the conal and truncal cushions is marked by an outer curvature of the OFT (the conotruncal curvature). (C) The conotruncal cushions (CTCs) and intercalated cushions (ICCs) develop within the OFT. These cushions occupy four quadrants of the OFT (shown in cross-section). The conotruncal cushions fuse to septate the OFT, as shown in D. (D) Fusion of the conotruncal cushions forms a spiral septum, the truncal part of which divides the OFT into aorta and pulmonary trunk, whereas the conal part septates the OFT into left and right ventricular outlets (LVOT, RVOT). The aortic valves (AV) and pulmonic valves (PV) develop at the conotruncal junction.

Atrioventricular and semilunar valve development

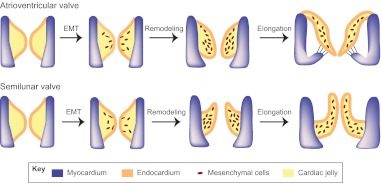

Heart valves develop at endocardial cushions of the AVC and OFT. Valve morphogenesis begins with the transformation of endocardial cells into mesenchymal cells through EMT (Fig. 5). Endocardial cushions with mesenchymal cells then elongate and remodel themselves to form primitive valves that gradually mature into thin valve leaflets. The elongation of valve leaflets is accomplished by a combination of cell proliferation at the growing edge and apoptosis at the base of the cushion (Hurle et al., 1980).

Fig. 5.

Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transformation and valve elongation. Endocardial cells in the AV cushions and conal cushions undergo epithelial-to-mesenchymal transformation (EMT) and generate mesenchymal cells that populate the cushions. The mesenchymal cushions then remodel and elongate themselves to from primitive valves that mature into thin valve leaflets (shown here for the atrioventricular valves and the semilunar valves).

The mitral and tricuspid (atrioventricular) valves originate from AV endocardial cushions. The fusion and remodeling of superior and inferior AV cushions, while dividing the AVC, gives rise to the anterior mitral leaflet and the septal tricuspid leaflet (de Lange et al., 2004) (Fig. 6A,B). The left lateral AV cushion becomes the posterior mitral leaflet, whereas the right lateral cushion produces the anterior and posterior tricuspid leaflets. Failure of the superior and inferior cushions to fuse causes a cleft in the anterior mitral leaflet, resulting in leaky ‘cleft mitral valve’, a disease encountered in patients with Down syndrome (Fraisse et al., 2003). Tricuspid valve malformations also cause human disease, such as the Ebstein’s anomaly: the septal and often the posterior tricuspid leaflets are displaced into the right ventricle with the anterior leaflet becoming excessively large, thus causing tricuspid valve regurgitation or stenosis (see Glossary, Box 1) (Brickner et al., 2000b).

Fig. 6.

Endocardial cushions and heart valve leaflets. (A) Schematic of endocardial cushions in the atrioventricular (AV) canal and the outflow tract (OFT). The figure is a superior view of the heart with atria removed. The cushions are color coded to correspond to their derived valve leaflets illustrated in B. CTC. conotruncal cushions; ICC. intercalated cushions; sAVC. superior AV cushion; iAVC. inferior AV cushion; rlAVC. right lateral AV cushion; llAVC. left lateral AV cushion. (B) Schematic (superior view) of atrioventricular and semilunar valve leaflets that develop from the corresponding cushions color coded in A. PV, pulmonary valve; AV, aortic valve; TV, tricuspid valve; MV, mitral valve.

The aortic and pulmonic (semilunar) valves arise from the conotruncal and intercalated cushions at the OFT. The conotruncal cushions give rise to the right and left leaflets of semilunar valves (Fig. 4C, Fig. 6A,B) (Restivo et al., 2006; Okamoto et al., 2010). Conal cushions, capable of supporting EMT of the endocardium, probably have major contributions to the aforementioned valve leaflets, of which the mesenchymal tissues largely come from the endocardium (de Lange et al., 2004). Adjacent to the conotruncal cushions are two other distinct cushions – the right-posterior and the left-anterior intercalated cushions – that develop respectively into the posterior aortic and the anterior pulmonic leaflets (Fig. 4C, Fig. 6A,B) (Anderson et al., 2003b; Restivo et al., 2006). These semilunar valve leaflets also derive their mesenchyme primarily from the endocardium (de Lange et al., 2004). Semilunar valve malformations are common and occur in 2-3% of the population, causing valve regurgitation and/or stenosis (Brickner et al., 2000a).

Similarities between AVC and OFT septation

Morphogenesis of the AV and OFT cushions is similar. The analogous roles of these cushions in cardiac septation and valve formation are better appreciated by rotating the OFT 90° counter-clockwise to superimpose the corresponding OFT and AV cushions (Fig. 6A). The superior and inferior AV cushions fuse to divide the AVC, forming valve leaflets that flank the AVC septation site; comparably, the right-superior and left-inferior conal cushions merge to separate the OFT, bringing about valve leaflets that border the OFT septation (Fig. 6A,B). Conversely, the lateral AV cushions are similar in function to the intercalated OFT cushions in that they both lack direct contributions to AV/OFT septation and that they form valve leaflets that oppose the AV/OFT septation site (Fig. 6A,B). The AVC and OFT, therefore, have evolved similar strategies for lumen septation and valve formation, sharing many essential developmental genes and pathways (Fig. 7).

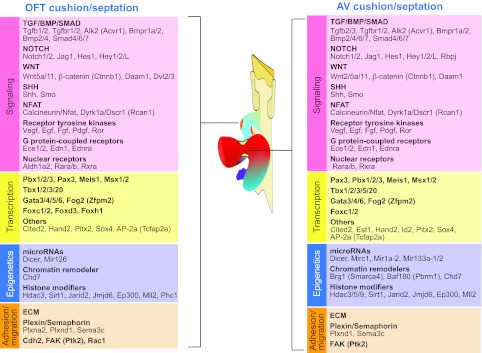

Fig. 7.

Genes and pathways essential for cardiac septation and valve development. Cushion and valve development, and hence septation, in the outflow tract (OFT) and the atrioventricular (AV) canal require similar molecular pathways. Factors required include those involved in signaling, transcription, epigenetics and cell adhesion/migration.

Cell lineages that contribute to septum formation and valve development

The endocardium, secondary heart field and neural crest contribute progenitor cells that give rise to septal tissues or valve leaflets. Besides direct lineage contributions, these progenitor cells of different origins interact with each other and with other cells in the heart to orchestrate cardiac septation and valve development.

Endocardium and EMT

EMT of the endocardium occurs only in the endocardial cushions and is regulated by many signaling factors secreted by the myocardium underlying the cushion. These EMT-regulating factors include bone morphogenetic proteins 2 and 4 (Bmp2, Bmp4), transforming growth factorβ 2 and 3 (TGFβ2, TGFβ3) and vascular endothelial growth factor (Vegf) (Fig. 7; Tables 1, 2). To react to myocardial signals and begin EMT, the endocardium at the cushion expresses receptors and effectors downstream of the myocardial signaling pathways, including Alk2 (Acvr1), Alk3 (Bmpr1a), Alk5 (Tgfbr1), Vegf-R, Notch1 and β-catenin. Different from the chamber myocardium, the myocardium at the cushion is specified and programmed by genes, such as Tbx2, Bmp2, Nfatc2, Nfatc3 and Nfatc4, to suppress chamber-specific gene expression, produce EMT-regulating molecules, and deposit extracellular matrix to support EMT (Abedin et al., 2004; Chang, C. P. et al., 2004; Christoffels et al., 2004; Rivera-Feliciano and Tabin, 2006; Shirai et al., 2009). The endocardium at the cushion is also different from that in the cardiac chamber: the cushion endocardium expresses genes essential for septal and valvular development, such as those encoding Nfatc1 and Vegf receptors, in a temporal pattern different from that of the chamber endocardium (Chang, C. P. et al., 2004; Stankunas et al., 2010). Such distinct gene programming and disparate arrays of signaling factors and receptors at the endocardial cushion determines the regional specificity of EMT. Much less is known about the post-EMT events at the endocardial cushion: for example, how mesenchymal cells control the remodeling of valvular and septal tissues. Future efforts to generate inducible and/or tissue-specific knockout mouse lines that specifically target cushion mesenchymal cells independent of their endocardial precursors will facilitate the investigation of post-EMT remodeling events at the cushion.

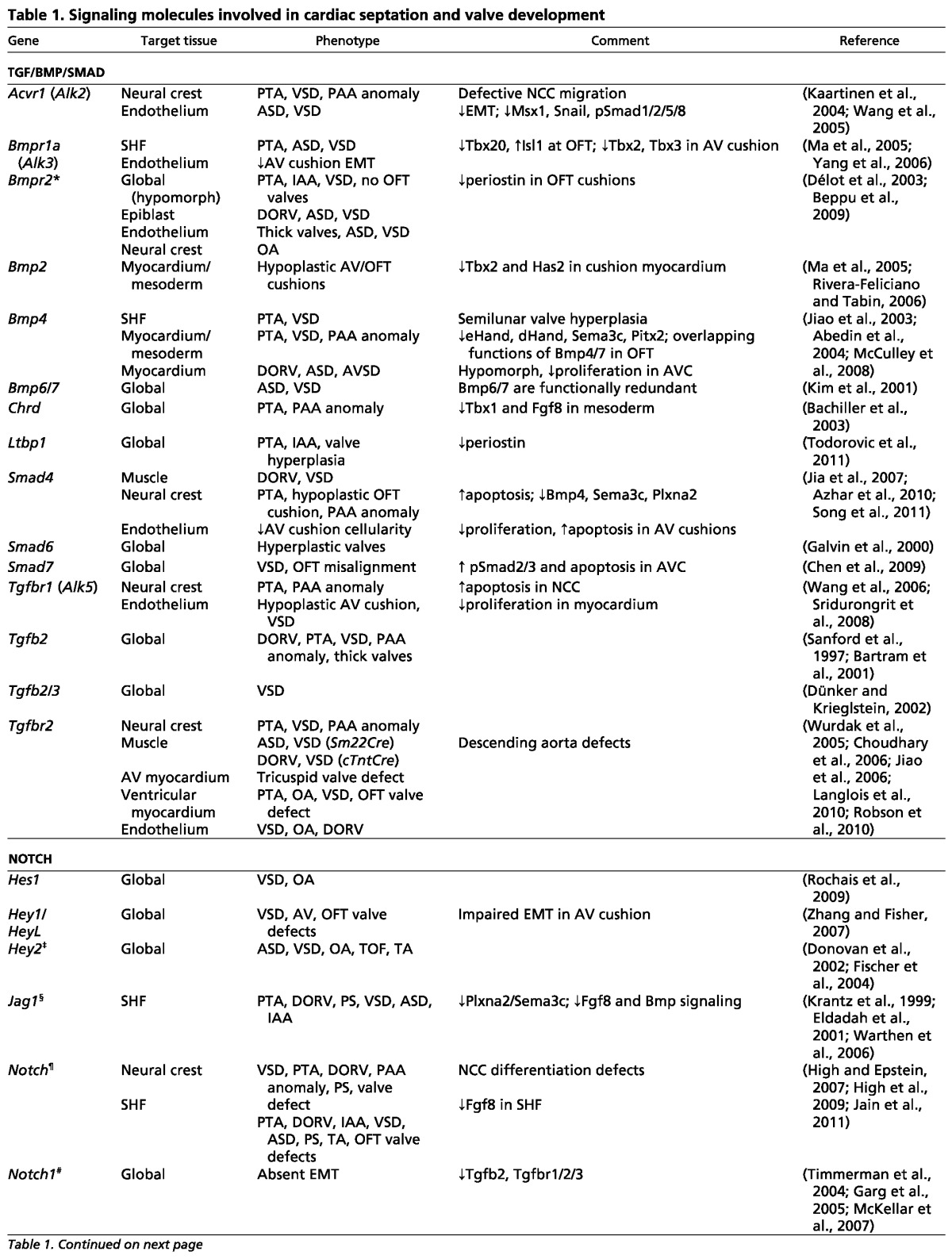

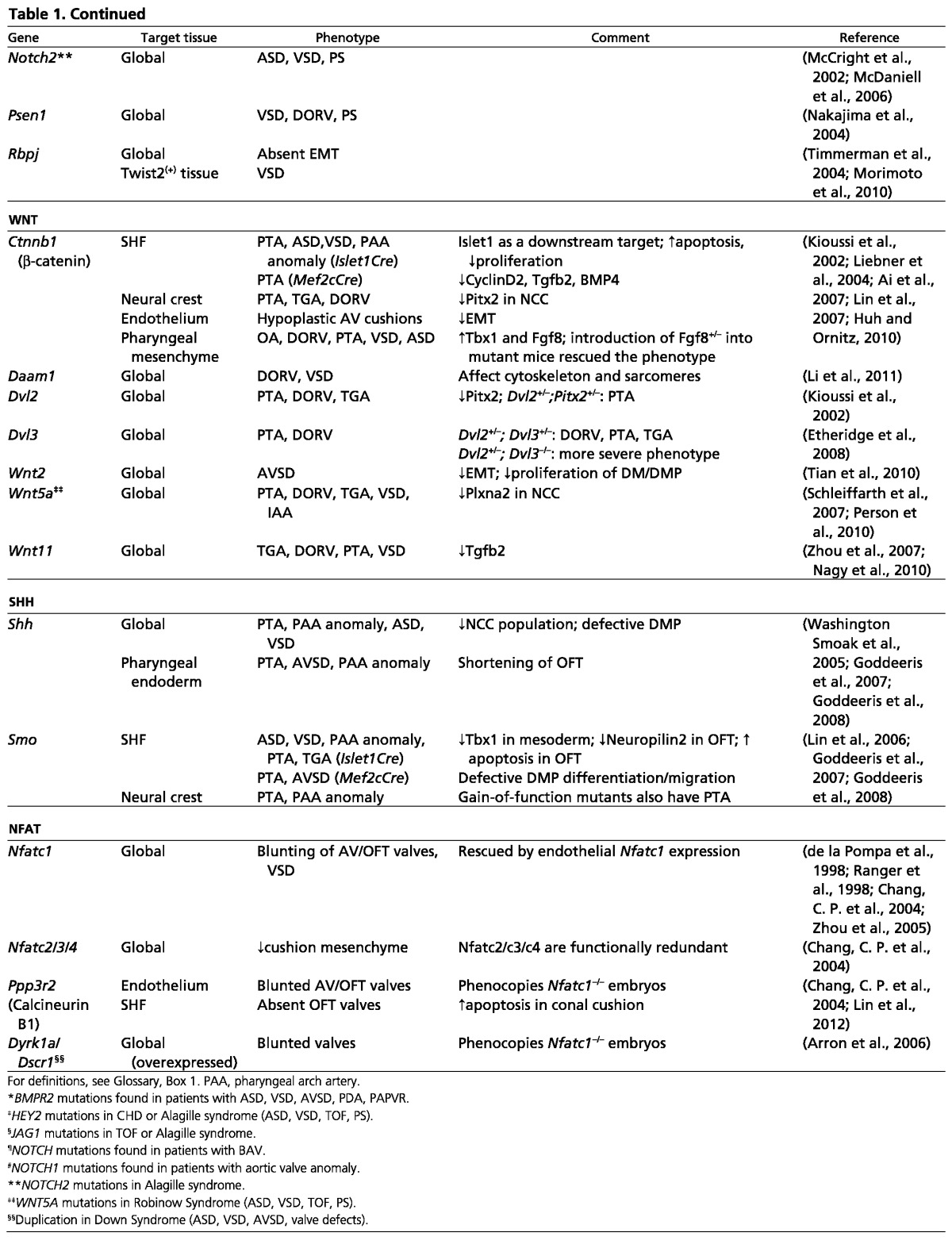

Table 1.

Signaling molecules involved in cardiac septation and valve development

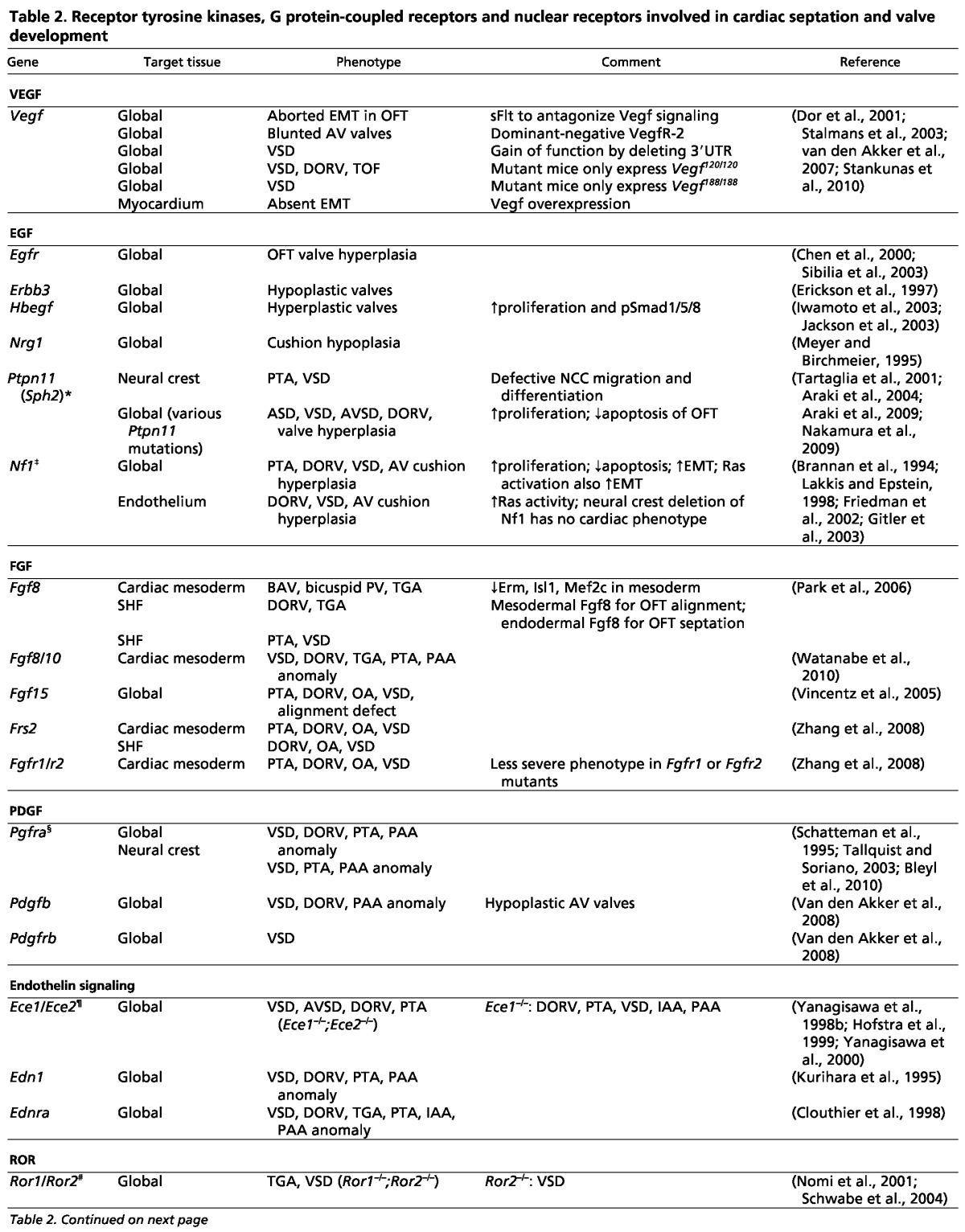

Table 2.

Receptor tyrosine kinases, G protein-coupled receptors and nuclear receptors involved in cardiac septation and valve development

The secondary heart field

The SHF progenitor cells contribute to cardiac septation and valve development. SHF progenitors give rise to the DMP mesenchyme, which merges with AV cushions and becomes part of the atrial septum (Snarr et al., 2007b). SHF progenitors also give rise to the OFT myocardium (Verzi et al., 2005), which secretes signaling molecules that stimulate the conal endocardium to undergo EMT, an essential step for later development of the ventricular outlet septum and semilunar valve leaflets (Anderson et al., 2003b; de Lange et al., 2004). Besides promoting EMT, the SHF-derived OFT myocardium secretes chemotactic molecules, such as Sema3c, to attract NCCs into the OFT to form the aortopulmonary septum (Brown et al., 2001; Feiner et al., 2001; Toyofuku et al., 2008). Furthermore, at the base of the aorta and pulmonary trunk, the SHF gives rise to vascular smooth muscle cells (Cai et al., 2003; Verzi et al., 2005) to support the separation of these arteries from ventricular outlets.

Disruption of many signaling pathways in the SHF, using Mef2c- or Islet1-Cre lines (Cai et al., 2003; Verzi et al., 2005), results in abnormalities in OFT septation or semilunar valves. These pathways include Wnt/β-catenin, BMP (Bmp4, Bmpr1a), Fgf8, Notch, Hedgehog/Smoothened, and calcineurin/Nfatc1 signaling (Fig. 7, Tables 1, 2). One major issue yet to be resolved is the actual action site(s) of these ‘SHF pathways’, i.e. whether they operate within the SHF or within SHF-derived tissues. Because of the overlap of many of the ‘SHF’ pathways with those functioning in cardiac tissues that are essential for EMT and cushion development, the outcomes of genetic manipulation in the SHF should be carefully interpreted and, in most cases, require further investigations. Nevertheless, calcineurin and Notch are known to operate in SHF progenitors to control OFT development. Deletion of calcineurin b1 (Cnb1; Ppp3r1 – Mouse Genome Informatics) in SHF progenitors causes cell apoptosis and regression of conal cushions, resulting in absent semilunar valves (Lin et al., 2012). Conversely, Cnb1 deletion in the OFT myocardium does not cause semilunar valve defects (Lin et al., 2012), thus localizing the site of calcineurin action to SHF progenitors for semilunar valve development. Likewise, inhibition of the Notch pathway in SHF progenitors causes OFT septation defects (such as DORV and PTA), but a later inhibition of Notch in the myocardium does not produce such defects (High et al., 2007; High et al., 2009).

Besides OFT development, AV septation requires signaling in SHF progenitors. Embryos lacking Hedgehog signaling in SHF progenitors, but not those lacking Hedgehog signaling in the myocardium or endocardium, show AV septal defects and a failure of the SHF-derived DMP mesenchyme to protrude into the atrial chamber (Goddeeris et al., 2008). Signaling within the SHF progenitors before they differentiate into cardiac cells, therefore, is essential for both AV and OFT septation. Further studies will be needed to elucidate how SHF signaling specifies developmental functions of SHF-derived tissues and how SHF progenitors modulate the activities of NCCs as the latter cells traverse the SHF during their migration to the heart.

Neural crest cell lineage

Cardiac NCCs migrate from their original location in the hindbrain (rhombomeres 6-8) to the pharyngeal arches and then to the heart to form the aortopulmonary septum (Kirby et al., 1983). Migrating NCCs actively exchange signals with surrounding tissues, such as the pharyngeal arch and the OFT myocardium. The pharyngeal arch endothelium, through its endothelin-converting enzyme-1 (Ece1), produces the signaling molecule endothelin-1, which activates the endothelin receptor A on NCCs to modulate NCC activities for pharyngeal arch artery (PAA) and OFT development. Embryos lacking Ece1 or endothelin receptor A develop PAA defects, as well as septation defects such as VSD, OA, DORV, PTA or TGA (Clouthier et al., 1998; Yanagisawa et al., 1998a). The OFT myocardium secretes Sema3c (ligand) to attract NCCs, which express Plxna2 (receptor), and promotes them to migrate into the OFT, where NCCs become the mesenchyme of truncal cushions. The truncal mesenchyme then fuses and differentiates to form a smooth muscle septum (aortopulmonary septum) that divides the aorta and pulmonary trunk. Knockout of Plxna2 or Sema3c in mice impairs the migration of NCCs, leading to PAA defects and PTA (Brown et al., 2001; Feiner et al., 2001; Toyofuku et al., 2008).

Many other signaling pathways are necessary for NCCs to regulate OFT septation, including the Wnt/β-catenin-Pitx2, Notch, TGF (Alk5), BMP (Alk2) and Hedgehog pathways (Fig. 7, Tables 1, 2). In contrast to the crucial roles of NCCs in OFT septation, most data suggest that NCCs do not have significant contribution to AV cushion development (Combs and Yutzey, 2009).

Molecular pathways that regulate septation and valve development

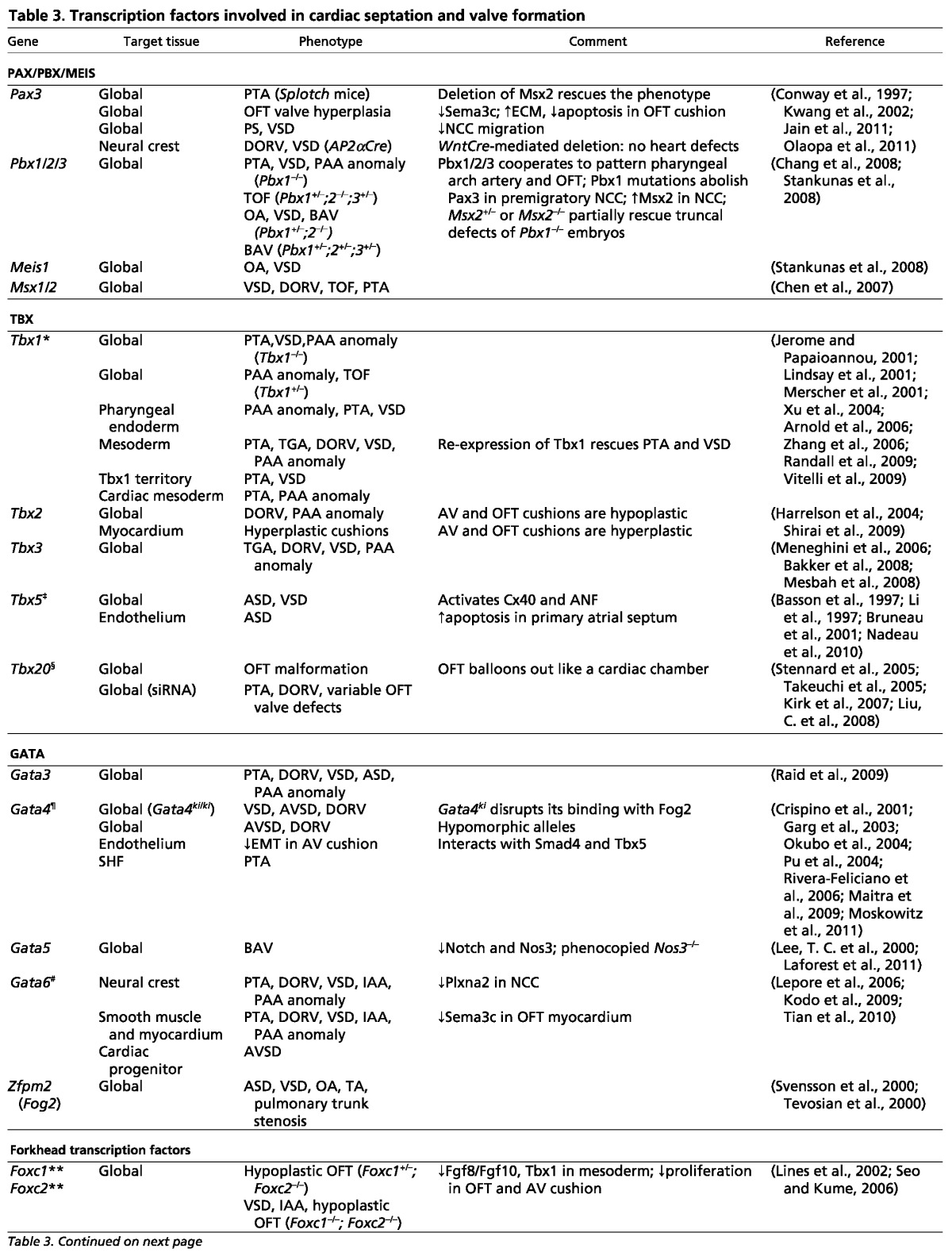

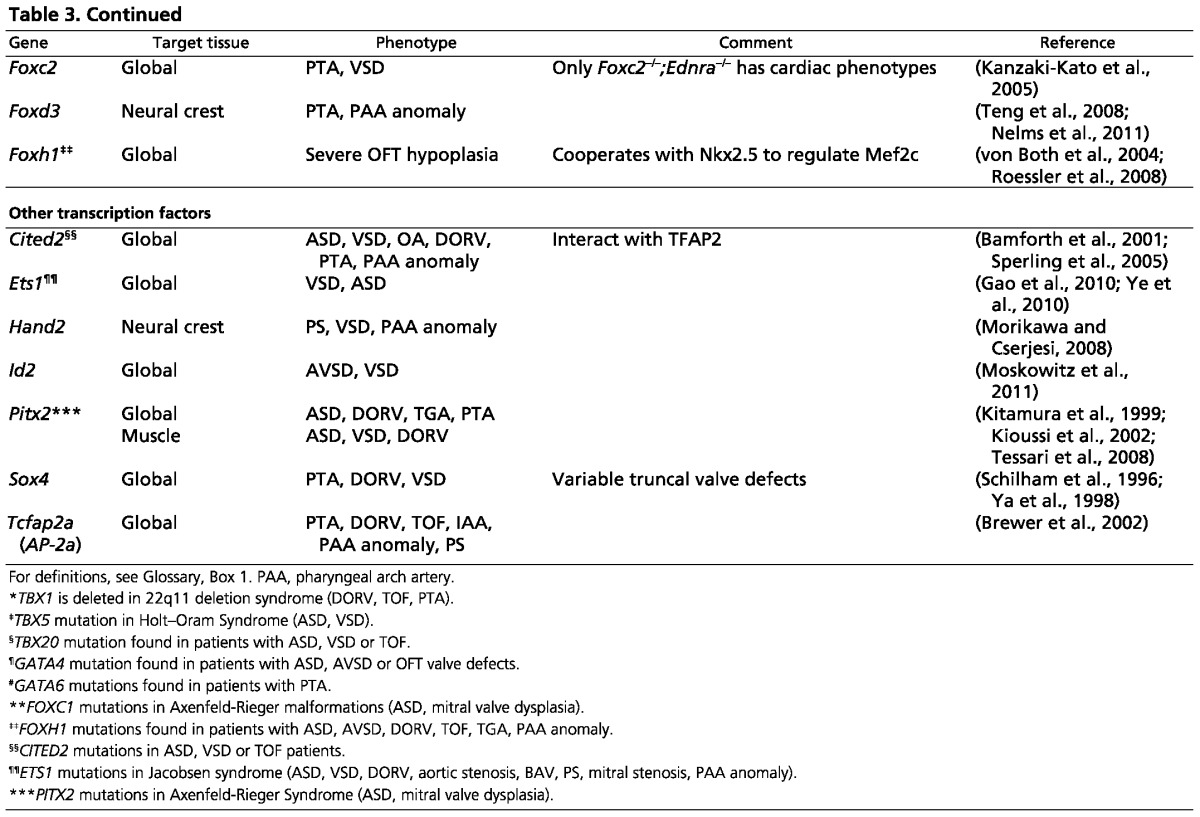

Many mouse genetic models have been established to demonstrate the function of genes involved in cardiac septation and valve development (Fig. 7). These include genes that encode signaling molecules (Tables 1, 2), transcription factors (Table 3), chromatin or epigenetic regulators (Table 4), and cell adhesion/migration molecules (Table 4). Discussed below are some of the most well characterized pathways that are known to regulate cardiac septation and valve development.

Table 3.

Transcription factors involved in cardiac septation and valve formation

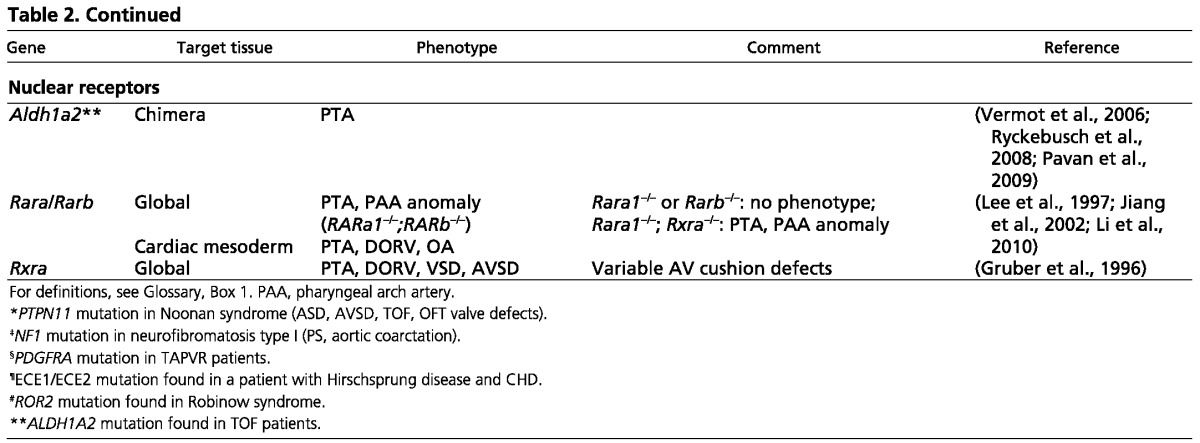

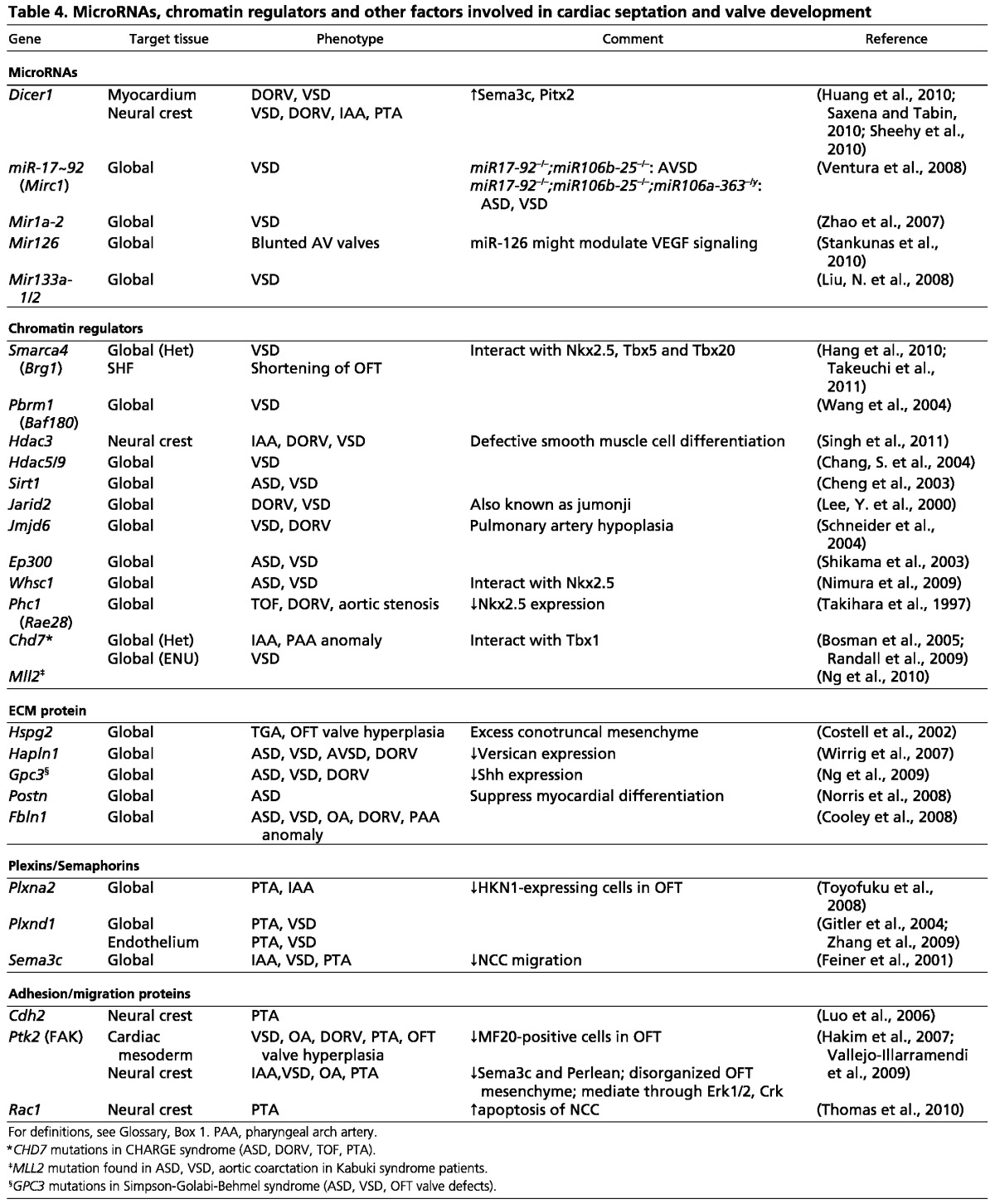

Table 4.

MicroRNAs, chromatin regulators and other factors involved in cardiac septation and valve development

TGF, BMP and SMAD pathways

TGFβs were among the first signaling molecules to be implicated in the initiation of EMT (Brown et al., 1996; Ramsdell and Markwald, 1997; Boyer et al., 1999; Brown et al., 1999; Boyer and Runyan, 2001), and multiple TGFβ isoforms are expressed in the endocardial cushions of mouse embryos (Akhurst et al., 1990; Millan et al., 1991). These mammalian TGFβ isoforms are highly redundant; disruption of multiple TGFβ ligands is often necessary to uncover their roles in heart development (Shull et al., 1992; Kaartinen et al., 1995; Sanford et al., 1997; Dünker and Krieglstein, 2002). Regardless of the redundancy, Tgfβ2 is known to function downstream of the Notch1, Bmp2 and Tbx2 pathways to activate Wnt/β-catenin signaling to promote EMT (Liebner et al., 2004; Timmerman et al., 2004; Shirai et al., 2009; Luna-Zurita et al., 2010).

BMPs have diverse roles in valve development and cardiac septation. Myocardial Bmp2 activates the expression of Has2 (hyaluronic acid synthetase 2) to produce the cushion extracellular matrix that is required for EMT (Rivera-Feliciano and Tabin, 2006). Also, myocardial Bmp2 signals the endocardial Bmp type 1A receptor (Bmpr1a) to induce the expression of Twist1, Msx1 and Msx2, which are essential for EMT (Ma et al., 2005). Bmp4 in the myocardium is necessary for cardiac septation. Absence of myocardial Bmp4 leads to ASD, VSD and PTA (Jiao et al., 2003; Liu et al., 2004; McCulley et al., 2008). Bmp6 and Bmp7, expressed in the myocardium and cushion/valve mesenchyme, are functionally redundant; mice with double knockout of these genes display hypocellular OFT cushions (Kim et al., 2001). Bmpr2, a receptor for Bmp2, Bmp4 and Bmp7, has different spatial roles. Mice with hypomorphic alleles of Bmpr2 exhibit interruption of the aortic arch (IAA; see Glossary, Box 1), PTA, and absent semilunar valves (Délot et al., 2003). Bmpr2 disruption in endothelial cells causes ASD, VSD, and hyperplastic semilunar and AV valve leaflets, whereas Bmpr2 deletion in myocardial cells or in NCCs leads to DORV or OA (Beppu et al., 2009).

SMAD proteins that transduce or modulate TGF/BMP signals are also essential for cardiac septation and valve formation. Loss of Smad4, the most common SMAD, in NCCs results in pharyngeal arch artery defects, OFT cushion hypoplasia and PTA (Jia et al., 2007). Smad4-null NCCs have increased apoptosis and reduced presence in the OFT, accompanied by a reduction in the Bmp4, Sema3c and Plxna2 signals that are necessary for OFT septation. By contrast, disruption of Smad6, which inhibits BMP signaling, causes hyperplasia of the AV and OFT cushions, leading to hyperplastic valves (Galvin et al., 2000).

Notch signaling

Notch signaling is necessary for EMT (Niessen and Karsan, 2008; MacGrogan et al., 2010), and mutation of Notch1 or its nuclear effector Rbpjk (Rbpj – Mouse Genome Informatics) causes EMT failure (Timmerman et al., 2004). Endocardial Notch1 induces the expression of Tgfβ2 to activate the expression of Snail1 (Snai1) and Snail2 (Snai2), which repress VE-cadherin expression and hence disrupt cell-cell contact, allowing EMT to occur (Romano and Runyan, 2000; Timmerman et al., 2004; Luna-Zurita et al., 2010). EMT of the Notch1/Tgfβ2-primed endocardial cells requires myocardial Bmp2, the expression of which, however, is repressed by myocardial Notch1 (Luna-Zurita et al., 2010). These seemingly opposing effects of endocardial and myocardial Notch signaling suggest a complex tissue-specific role for Notch in orchestrating EMT of AV cushions.

In the SHF, inhibition of Notch decreases Fgf8 expression, reduces EMT of OFT cushions, and impairs NCC migration with consequent thickened, unequally sized semilunar valve leaflets (High et al., 2009; Jain et al., 2011). Such an EMT defect is rescued by exogenous Fgf8, suggesting that Notch functions through Fgf8 to activate EMT of OFT cushions (High et al., 2009). NOTCH1 mutations are observed in some families with a multi-generation history of BAV and/or calcific aortic stenosis (Garg et al., 2005; Garg, 2006; McKellar et al., 2007; McBride et al., 2008; Rusanescu et al., 2008). Because Notch1 is capable of suppressing Runx2, which promotes calcification (Garg et al., 2005), NOTCH1 mutations in humans might cause RUNX2 upregulation with consequent valve calcification.

Disruption of the SHF Notch in mice also causes septation defects, including ASD, VSD, DORV and PTA (High et al., 2009). In humans, JAG1 or NOTCH2 mutations are associated with Alagille syndrome (McDaniell et al., 2006; Warthen et al., 2006), an autosomal dominant disorder with abnormalities in multiple organs, including pulmonary stenosis and TOF. The Alagille heart phenotypes of pulmonary stenosis and TOF also occur in mice lacking Hey2, a Notch downstream target gene (Donovan et al., 2002).

The Wnt pathway

Wnt/β-catenin signaling plays a major role in EMT and cardiac septation. For AV cushion development, β-catenin functions downstream of Tgfβ2 in the endocardium to promote EMT of AV cushions (Liebner et al., 2004). Wnt2 also signals through β-catenin to recruit SHF-derived mesenchymal cells into DMP. Mice lacking Wnt2 or β-catenin in the SHF have reduced DMP mesenchyme, resulting in ASD and VSD (Lin et al., 2007; Tian et al., 2010). For OFT development, β-catenin has crucial roles in the SHF and in NCCs. In the SHF, β-catenin is essential to prevent the development of abnormal pharyngeal arteries and PTA (Lin et al., 2007). In NCCs, Wnt/β-catenin functions through Pitx2 to control OFT septation. Migrating NCCs that lack β-catenin show reduced expression of Pitx2, disruption of which results in failure of NCC migration into the OFT, causing PTA, DORV or TGA (Kioussi et al., 2002).

The noncanonical Wnts, although not signaling through β-catenin, are also essential for OFT septation; mice lacking Wnt5a or Wnt11 display TGA, DORV or PTA (Schleiffarth et al., 2007; Zhou et al., 2007).

Epidermal growth factor signaling

Epidermal growth factor (EGF) signaling is essential for AV and OFT development. EGF signaling between endocardial HB-EGF (Hbegf; ligand) and myocardial ErbB1 (Egfr; an EGF receptor), for example, suppresses cushion development. Mutations affecting HB-EGF, an endocardial ligand that directly binds ErbB1 and ErbB4, result in hyperproliferation of cushion mesenchymal cells and hyperplasia of AV and semilunar valves (Iwamoto et al., 2003; Jackson et al., 2003). Similar cushion and semilunar valve hyperplasia is observed in mice with mutations in ErbB1, which is present primarily in the myocardium (Chen et al., 2000; Jackson et al., 2003; Sibilia et al., 2003). In contrast to myocardial ErbB1 signaling, ErbB2- or ErbB4-based signaling in the myocardium does not seem necessary for early cushion development. Mutations in ErbB2 or ErbB4, both present in the myocardium, have no apparent cushion defects at embryonic day (E) 10.5 before the mutant embryos die at E10-11 of severe hypotrabeculation (Gassmann et al., 1995; Lee et al., 1995).

EGF signaling within the mesenchyme promotes cushion development. Mutations in ErbB3, an EGF receptor present in the cushion mesenchyme (Meyer and Birchmeier, 1995), causes hypoplastic endocardial cushions (Erickson et al., 1997). Such mesenchymal ErbB3 signaling might be activated by endocardial Neuregulin 1 (Nrg1), which is a ligand that directly binds ErbB3 and ErbB4, because Nrg1 mutations, like ErbB3 mutations, cause cushion hypoplasia (Meyer and Birchmeier, 1995). The opposing effects of HB-EGF/ErbB1 and Nrg1/ErbB3 on the development of cushion mesenchyme suggest that a balance of signaling through ErbB1 and ErbB3 is essential to determine the extent of cushion and valve formation.

Tyrosine phosphorylation and activation of ErbB receptors is modulated by protein tyrosine phosphatases, including the phosphatase Shp2 encoded by Ptpn11 (Neel et al., 2003). PTPN11 mutations are associated with Noonan syndrome, which is characterized by short stature, facial abnormalities, myeloproliferative disease and heart malformations. The spectrum of heart defects in Noonan syndrome includes dysplastic/stenotic pulmonary valves, bicuspid/stenotic aortic valves, ASD or AVSD, and TOF (Tartaglia et al., 2001; Romano et al., 2010). Cardiac defects consistent with Noonan syndrome are present in mice bearing a Ptpn11 point mutation (D61G) and exhibiting hyperplastic cushions and large valves, AVSD and DORV (Araki et al., 2004). The Ptpn11 (D61G) mutation, possibly through activating ErbB/Erk, functions in the endocardium to enhance EMT and cause valve hyperplasia (Araki et al., 2009).

Calcineurin/NFAT signaling

The two distinct phases of valve development, EMT and valve elongation, are organized by sequential waves of nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) signaling (Chang, C. P. et al., 2004). Myocardial Nfatc2, Nfatc3 and Nfatc4 first trigger EMT of the AV cushions by repressing the expression of a potent EMT inhibitor, VEGF-A. Subsequent to EMT, a second wave of NFAT signaling, directed by calcineurin and Nfatc1, occurs in the endocardium to promote valve remodeling and elongation. However, the mechanisms that control the transition from EMT to valve elongation phase are not entirely clear. The phase transition is likely to be facilitated by VEGF-A, which is upregulated along with Vegf-R2 (Kdr – Mouse Genome Informatics) at the transition window to terminate EMT (Dor et al., 2001; Dor et al., 2003; Chang, C. P. et al., 2004) as well as to help initiate AV valve elongation (Stankunas et al., 2010).

In the endocardium, calcineurin triggers the entry of Nfatc1 into the nucleus to activate target genes essential for valve elongation (de la Pompa et al., 1998; Ranger et al., 1998; Chang et al., Chang, C. P. et al., 2004; Wu et al., 2007; Zeini et al., 2009). Furthermore, to support the endocardial growth required for valve elongation, a subpopulation of Nfatc1-expressing endocardial cells does not undergo EMT but remains as a proliferative cell population (Wu et al., 2011). In the OFT, Nfatc1 keeps EMT of conal cushions in check to prevent excessive EMT and invasion of EMT-derived mesenchymal cells into truncal cushions that are occupied by NCC-derived mesenchyme (Wu et al., 2011). Nfatc1 thus delineates a boundary between EMT- and NCC-derived mesenchyme at the conotruncal junction, where the semilunar valves develop. Besides functioning in the endocardium, calcineurin-Nfatc1 signals in the SHF to maintain conal cushion development (Lin et al., 2012). Without SHF calcineurin or Nfatc1, the conal cushion mesenchyme displays enhanced apoptosis, resulting in failure of semilunar valve formation.

Calcineurin-NFAT signaling is counteracted by Dscr1 (Down syndrome critical region 1) and Dyrk1a (dual specificity tyrosine-phosphorylation-regulated kinase 1A). Dscr1 inhibits calcineurin activity to prevent nuclear entry of NFAT, whereas Dyrk1a promotes nuclear export of NFAT (Arron et al., 2006). Dscr1 and Dyrk1a thus synergistically inhibit NFAT signaling. The triplication of DSCR1 (RCAN1 – Human Gene Nomenclature Database) and DYRK1A genes in Trisomy 21 (Down syndrome) might, therefore, attenuate calcineurin-NFAT signals in multiple developmental tissues, leading to the endocardial cushion and valve defects, as well as other developmental phenotypes, associated with Down syndrome (Lange et al., 2004; Arron et al., 2006; Wu et al., 2007).

VEGF signaling

Regulation of valve development by VEGF signaling is a complex process. VEGF-A can function as an inhibitor of EMT (Dor et al., 2001; Dor et al., 2003; Chang, C. P. et al., 2004), a growth factor for endothelial/endocardial cell proliferation (Fong et al., 1995; Shalaby et al., 1995; Olsson et al., 2006), and a promoter for valve elongation (Stankunas et al., 2010). Moreover, the expression of VEGF receptors is dynamically regulated during valve development (Stankunas et al., 2010). VEGF receptor 1 (Vegf-R1; Flt1 – Mouse Genome Informatics) is highly expressed in the early cushion endocardium, but its expression subsides after EMT, whereas VEGF receptor 2 (Vegf-R2) does not exhibit robust expression in the cushion endocardium until after EMT is complete. This distinct spatiotemporal expression of VEGF receptors correlates with their function in valve development. Vegf-R1 is essential for EMT of OFT cushions, whereas Vegf-R2 is required primarily for the elongation of AV valves after EMT (Stankunas et al., 2010).

Pax3, Pbx and Meis

Pax3 is a paired homeodomain transcription factor required for OFT septation (Epstein et al., 1991; Epstein, 1996; Conway et al., 1997). Pax3 is transiently expressed in premigratory NCCs and is quickly turned off before the emigration of those cells (Epstein et al., 2000; Chang et al., 2008). Deletion of Pax3 in early NCCs causes OFT septation defects (such as PTA), whereas a later deletion of Pax3 in NCCs has no influence on OFT development (Olaopa et al., 2011). Pax3 thus functions within a short window to program NCCs for OFT septation.

The short burst of Pax3 in NCCs is absent in mice lacking Pbx1, a TALE homeodomain transcription factor (Chang et al., 2008). Pbx1-null embryos exhibit pharyngeal arch artery defects, VSD and PTA, accompanied by an absence of Pax3 expression and upregulation of Msx2 in premigratory NCCs (Chang et al., 2008). Msx2 encodes a homeodomain transcription factor and is repressed by Pax3 in NCCs to maintain OFT development (Kwang et al., 2002). Pax3, by contrast, is a direct transcriptional target of Pbx1 and Pbx’s co-factors – the Hox and Meis homeodomain proteins (Chang et al., 1995; Chang et al., 1997; Chang et al., 2008). Both Hox and Meis are required for heart development. Hoxa3 knockout mice exhibit pharyngeal arch artery defects (such as patent ductus arteriosus; see Glossary, Box 1) and possible pulmonic stenosis (Chisaka and Capecchi, 1991), whereas Meis1-null mice show overriding aorta with VSD (Stankunas et al., 2008). The transcriptional cascade Pbx/Hox/Meis-Pax3-Msx2, composed of five different classes of homeodomain proteins, is therefore essential to program NCCs for the development of OFT.

Pbx1, the major Pbx gene, cooperates with two minor Pbx genes (Pbx2 and Pbx3) to control OFT development (Chang et al., 2008; Stankunas et al., 2008). Mice with compound Pbx mutations develop a spectrum of OFT malformations, with the exact type of abnormalities determined by the Pbx genotype (Chang et al., 2008; Stankunas et al., 2008). The triple heterozygous mice (Pbx1+/–;2+/–;3+/–) have isolated BAV, whereas Pbx1+/–;2–/– mice display overriding aorta with BAV. By contrast, Pbx1+/–;2–/–;3+/– mice have TOF with small, malformed semilunar valves, yet Pbx1–/– mice exhibit PTA with abnormal valve leaflets. Such increasing OFT abnormalities, from isolated bicuspid valve to PTA, are a consequence of a decreasing dosage of major and minor Pbx genes. Also, mutations in the gene encoding a Pbx DNA-binding partner, Meis1, result in VSD and overriding aorta, defects that fall within the spectrum of OFT abnormalities caused by Pbx mutations. The genetic influence of a major gene (Pbx1), minor genes (Pbx2 and Pbx3) and an interacting gene (Meis1) demonstrates a multi-genetic origin of congenital heart disease.

GATA factors

The zinc finger GATA transcription factors are essential for cardiac septation and valve formation. For example, mice with Gata4 hypomorphic alleles exhibit myocardial hypoplasia, DORV and AVSD (Crispino et al., 2001; Pu et al., 2004), and mice lacking endocardial Gata4 have EMT failure in AV cushions (Rivera-Feliciano et al., 2006). Gata4 cooperates with Smad4 to control AV septation and EMT (Moskowitz et al., 2011). Disruption of endocardial Smad4, like Gata4 mutations, results in EMT failure in AV cushions. Gata4 and Smad4 synergistically activate the expression of Id2, a helix-loop-helix transcriptional repressor, to regulate AV septation (Moskowitz et al., 2011). Gata4 also interacts with Tbx5 to control AV cushion development. Gata4 and Tbx5 double heterozygotes display thin myocardium as well as AVSD with a single atrioventricular valve (Maitra et al., 2009). GATA4 mutations are found in patients with septal defects (ASD or AVSD) or valve abnormalities (aortic regurgitation, mitral regurgitation and/or pulmonary stenosis) (Garg et al., 2003; Okubo et al., 2004; Sarkozy et al., 2005; Moskowitz et al., 2011). Interestingly, certain GATA4 missense mutations (G303E and G296S) in humans are known to disrupt the binding of GATA4 to SMAD4 (Moskowitz et al., 2011) or to TBX5 (Maitra et al., 2009), suggesting a conserved function of the human GATA4-SMAD4 and GATA4-TBX5 complex for AV septation and valve development.

Gata5 is involved in aortic valve development. Gata5-null mice have reduced ventricular trabeculation and partially penetrant BAV (Laforest et al., 2011). Endocardial Gata5 regulates aortic valve formation possibly through Notch signaling and endothelial nitric oxide synthase Nos3 (Lee, T. C. et al., 2000; Laforest et al., 2011).

Gata6 is essential for both AV and OFT development. Gata6 synergizes with its transcription target Wnt2 to regulate AV septation, and deletion of Gata6 in cardiac progenitor cells causes AV septation defects (Tian et al., 2010). By contrast, Gata6 regulates OFT septation through its activation of Sema3c and Plxna2 (Lepore et al., 2006; Kodo et al., 2009). Gata6 transcriptionally activates Sema3c in the OFT myocardium and Plxna2 in NCCs to orchestrate the migration of NCCs into the OFT. Deletion of Gata6 in the myocardium or NCCs causes Sema3c or Plxna2 downregulation, leading to pharyngeal arch artery defects and OFT abnormalities (PTA or DORV) (Lepore et al., 2006). GATA6 mutations that disrupt GATA6 nuclear localization (E486del) or abolish GATA6’s transcriptional activity on SEMA3C and PLXNA2 promoters (E486del and N466H) have been identified in patients with PTA (Kodo et al., 2009).

T-box genes

Tbx genes encode T-box transcription factors that regulate multiple developmental processes (Greulich et al., 2011). The absence of TBX1 is thought to be a major cause of 22q11 deletion syndrome (DiGeorge, velocardialfacial, and conotruncal face anomaly syndromes), which includes craniofacial abnormalities, pharyngeal arch artery defects and cardiac malformations (TOF, DORV and PTA). In mice, Tbx1 germline mutations or tissue-specific mutations in the pharyngeal endoderm or mesoderm result in pharyngeal arch artery defects and cardiac abnormalities (PTA and VSD) (Jerome and Papaioannou, 2001; Merscher et al., 2001; Vitelli et al., 2002; Arnold et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2006).

Tbx2 is essential for the developmental identity of myocardium at the AV and OFT cushions. Tbx2 is expressed in the cushion myocardium to repress the expression of chamber myocardium-specific genes (Habets et al., 2002; Christoffels et al., 2004; Harrelson et al., 2004). In Tbx2-null embryos, the cushion myocardium is partially turned into ventricular myocardium, resulting in hypoplastic endocardial cushions (Harrelson et al., 2004). Conversely, overexpression of Tbx2 in the myocardium of the heart tube inhibits cardiac chamber formation and chamber-specific gene expression (Christoffels et al., 2004). Such ectopic Tbx2 expression triggers excessive deposition of extracellular matrix in the ventricles and activates chamber myocardium to stimulate EMT (Shirai et al., 2009), rendering the chamber myocardium ‘cushion-like’. These changes are at least partly caused by ectopic activation by Tbx2 of the matrix-producing Has2 and the EMT-promoting Tgfβ2 (Shirai et al., 2009).

Tbx5 is essential for determining the left ventricle identity and interventricular boundary: the boundary between Tbx5-expressing left ventricle and non-Tbx5-expressing right ventricle determines the site of interventricular septation (Bruneau et al., 1999; Takeuchi et al., 2003). In mice, Tbx5 overexpression causes expansion of the left ventricle and a loss of interventricular septum, whereas in chick an extra interventricular septum forms at an ectopically induced boundary between Tbx5-positive and Tbx5-negative ventricles (Takeuchi et al., 2003). TBX5 mutations are associated with Holt-Oram syndrome, which is characterized by upper limb and cardiac malformations (ASD, VSD) (Basson et al., 1997; Li et al., 1997). These limb and cardiac defects are seen in mice with a heterozygous Tbx5 mutation (Bruneau et al., 2001), and loss of endocardial Tbx5 causes excessive apoptosis in primary atrial septum, possibly through disruption of the Tbx5/Gata4-Nos3 pathway (Nadeau et al., 2010).

TBX20 mutations occur in patients with various valve or septal malformations, including ASD, VSD and TOF (Kirk et al., 2007; Liu, C. et al., 2008). In line with this, Tbx20 knockdown in mice causes valve malformations (absent pulmonic valve with rudimentary aortic and tricuspid valves) and OFT defects (PTA or DORV) (Takeuchi et al., 2005).

MicroRNAs

MicroRNAs (miRNAs), which are short noncoding RNA species that post-transcriptionally silence target gene expression, have been implicated in multiple aspects of embryogenesis (Pauli et al., 2011). The biogenesis of functional miRNAs requires an RNase Dicer, the mutation of which abrogates the production of most mature miRNA species. Ablation of Dicer in the myocardium using Nkx2.5Cre (Stanley et al., 2002) causes DORV with VSD, accompanied by upregulation of Pitx2 and Sema3c in the myocardium (Saxena and Tabin, 2010). Deletion of Dicer in NCCs leads to abnormal pharyngeal arch arteries, VSD, DORV or PTA (Huang et al., 2010; Sheehy et al., 2010). Several miRNAs are known to regulate cardiac septation and valve development. Inactivation of Mir1a-2 or miRNA-17∼92 (MirC1), or compound deletion of Mir133a-1 and Mir133a-2 gives rise to VSD (Zhao et al., 2007; Liu, N. et al., 2008; Ventura et al., 2008), whereas ablation of miRNA-126 (Mir126 – Mouse Genome Informatics) results in AV valve defects (Stankunas et al., 2010). Because miRNA-126 is a modifier of VEGF signaling (Fish et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2008), it is possible that miRNA-126 interacts with calcineurin/NFAT signaling (Chang, C. P. et al., 2004) to modulate VEGF activities during AV valve development.

Chromatin regulators

Gene regulation at the chromatin level is achieved by three processes: DNA methylation, ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling, and covalent histone modifications. Factors that regulate these processes to alter chromatin structure play crucial roles in heart development and disease, and the details of these are described in recent reviews (Chang and Bruneau, 2011; Han et al., 2011). Table 4 summarizes the roles of chromatin-regulating factors known to regulate cardiac septation or valve development. These factors include chromatin remodelers (BAF complex, Chd7), polycomb repressive complex 1 (Phc1, also known as Rae28), histone methyltransferases (Whsc1, Mll2), histone demethylases (Jarid2, also known as Jumonji; Jmjd6, also known as Ptdsr), histone acetyltransferase (p300; Ep300 – Mouse Genome Informatics), sirtuins (Sirt1) and histone deacetylases (Hdac3, Hdac5, Hdac9).

New areas of research

Although murine genetic models have provided insights into the pathogenesis of human congenital heart disease (CHD), these models have not been able to fully recapitulate the spectrum of human pathobiology. One likely explanation is that the majority of mutations identified in patients with CHD are point mutations or insertions/deletions in the coding region (Wessels and Willems, 2010), which may generate amorphic, hypomorphic or hypermorphic alleles. However, murine studies largely use amorphic alleles and do not tackle modifier genes or variants in the noncoding region of the genome that can alter disease risk (Musunuru et al., 2010; Winston et al., 2010).

One way to overcome these limitations is to randomly mutagenize mice and screen for different susceptibility alleles or noncoding variants associated with CHD. The offspring of mice randomly mutagenized by N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea exhibit several types of cardiac septation defects, including VSD, DORV, PTA and TGA (Yu et al., 2004). Some of the genomic lesions have been identified as point mutations in genes essential for heart development, such as Sema3C (L605P) and connexin 43 (W45X), whereas most lesions await further investigations. In another cohort of randomly mutagenized mice, cardiac septal defects are the predominant lesion causing perinatal lethality (Kamp et al., 2010). Genomic lesions associated with AVSD in these mice have been mapped to a region spanning several megabases. Further elucidation of the genomic regions responsible for AVSD or other septation defects will provide additional insights into the genetic basis of human CHD.

Genome-wide surveys have also been applied to the genetic studies of human CHD. In sporadic, nonsyndromic TOF, copy number variants have been identified in several genomic loci, including those that encode known disease-associated genes (NOTCH1, JAG1) (Greenway et al., 2009). In patients with BAV, two haplotypes of a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) are strongly associated with the disease (Wooten et al., 2010). Also, next-generation sequencing of exome and whole genomes have facilitated studies of the genetic base of human diseases (Bamshad et al., 2011). Exome/genome analysis of disease-afflicted families or of large population-based studies provides a new, powerful tool for dissecting complex genetic traits and identifying disease-associated genomic lesions, intractable to conventional methods. Genome-wide association studies thus prompt further mechanistic investigations to define the causal roles of newly identified genomic lesions in CHD patients. It will be necessary to create new animal models carrying specific mutations to elucidate the mechanisms of how such genomic lesions cause human CHD.

Conclusions

The variety and large number of cells, genes and molecular pathways involved in cardiac septation and valve development highlights the complexity of the underlying developmental process. The spatiotemporal development of cardiac progenitor cells and endocardial cushions is regulated by genes that control diverse molecular and cellular processes, including those that control ligand-receptor signaling, signal transduction, transcription, chromatin or epigenetic regulation, extracellular matrix production, cell adhesion, and cellular motility (Tables 1, 2, 3, 4). Interactions between these genes in specific tissues and during distinct time windows of embryonic development are crucial for cushion development, septation and valve formation. Future research using multidisciplinary approaches from developmental biology, genetics, molecular biology and systems biology will be essential to resolve the mechanisms that underlie partitioning of the heart and to provide information for better treatment of CHDs.

Footnotes

Funding

C.-P.C. is supported by funds from the Oak Foundation, March of Dimes Foundation, Lucile Packard Foundation, National Institutes of Health (NIH), Children’s Heart Foundation, Office of the University of California (TRDRP), California Institute of Regenerative Medicine, and the American Heart Association (AHA) (National Scientist Development Award and Established Investigator Award). C.-J.L. is supported by a Lucille P. Markey Stanford Graduate Fellowship; C.-Y.L. and C.-H.C. by Stanford Institutional Fund. B.Z. is supported by NIH and AHA. Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

Competing interests statement

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Abedin M., Tintut Y., Demer L. L. (2004). Mesenchymal stem cells and the artery wall. Circ. Res. 95, 671–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Issa R., Kirby M. L. (2007). Heart field: from mesoderm to heart tube. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 23, 45–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ai D., Fu X., Wang J., Lu M. F., Chen L., Baldini A., Klein W. H., Martin J. F. (2007). Canonical Wnt signaling functions in second heart field to promote right ventricular growth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 9319–9324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhurst R. J., Lehnert S. A., Faissner A., Duffie E. (1990). TGF beta in murine morphogenetic processes: the early embryo and cardiogenesis. Development 108, 645–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson R. H., Webb S., Brown N. A., Lamers W., Moorman A. (2003a). Development of the heart: (2) Septation of the atriums and ventricles. Heart 89, 949–958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson R. H., Webb S., Brown N. A., Lamers W., Moorman A. (2003b). Development of the heart: (3) formation of the ventricular outflow tracts, arterial valves, and intrapericardial arterial trunks. Heart 89, 1110–1118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araki T., Mohi M. G., Ismat F. A., Bronson R. T., Williams I. R., Kutok J. L., Yang W., Pao L. I., Gilliland D. G., Epstein J. A., et al. (2004). Mouse model of Noonan syndrome reveals cell type- and gene dosage-dependent effects of Ptpn11 mutation. Nat. Med. 10, 849–857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araki T., Chan G., Newbigging S., Morikawa L., Bronson R. T., Neel B. G. (2009). Noonan syndrome cardiac defects are caused by PTPN11 acting in endocardium to enhance endocardial-mesenchymal transformation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 4736–4741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold J. S., Werling U., Braunstein E. M., Liao J., Nowotschin S., Edelmann W., Hebert J. M., Morrow B. E. (2006). Inactivation of Tbx1 in the pharyngeal endoderm results in 22q11DS malformations. Development 133, 977–987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arron J. R., Winslow M. M., Polleri A., Chang C. P., Wu H., Gao X., Neilson J. R., Chen L., Heit J. J., Kim S. K., et al. (2006). NFAT dysregulation by increased dosage of DSCR1 and DYRK1A on chromosome 21. Nature 441, 595–600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azhar M., Wang P. Y., Frugier T., Koishi K., Deng C., Noakes P. G., McLennan I. S. (2010). Myocardial deletion of Smad4 using a novel α skeletal muscle actin Cre recombinase transgenic mouse causes misalignment of the cardiac outflow tract. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 6, 546–555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachiller D., Klingensmith J., Shneyder N., Tran U., Anderson R., Rossant J., De Robertis E. M. (2003). The role of chordin/Bmp signals in mammalian pharyngeal development and DiGeorge syndrome. Development 130, 3567–3578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakker M. L., Boukens B. J., Mommersteeg M. T., Brons J. F., Wakker V., Moorman A. F., Christoffels V. M. (2008). Transcription factor Tbx3 is required for the specification of the atrioventricular conduction system. Circ. Res. 102, 1340–1349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bamforth S. D., Bragança J., Eloranta J. J., Murdoch J. N., Marques F. I., Kranc K. R., Farza H., Henderson D. J., Hurst H. C., Bhattacharya S. (2001). Cardiac malformations, adrenal agenesis, neural crest defects and exencephaly in mice lacking Cited2, a new Tfap2 co-activator. Nat. Genet. 29, 469–474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bamshad M. J., Ng S. B., Bigham A. W., Tabor H. K., Emond M. J., Nickerson D. A., Shendure J. (2011). Exome sequencing as a tool for Mendelian disease gene discovery. Nat. Rev. Genet. 12, 745–755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartram U., Molin D. G., Wisse L. J., Mohamad A., Sanford L. P., Doetschman T., Speer C. P., Poelmann R. E., Gittenberger-de Groot A. C. (2001). Double-outlet right ventricle and overriding tricuspid valve reflect disturbances of looping, myocardialization, endocardial cushion differentiation, and apoptosis in TGF-beta(2)-knockout mice. Circulation 103, 2745–2752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basson C. T., Bachinsky D. R., Lin R. C., Levi T., Elkins J. A., Soults J., Grayzel D., Kroumpouzou E., Traill T. A., Leblanc-Straceski J., et al. (1997). Mutations in human TBX5 cause limb and cardiac malformation in Holt-Oram syndrome. Nat. Genet. 15, 30–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beppu H., Malhotra R., Beppu Y., Lepore J. J., Parmacek M. S., Bloch K. D. (2009). BMP type II receptor regulates positioning of outflow tract and remodeling of atrioventricular cushion during cardiogenesis. Dev. Biol. 331, 167–175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleyl S. B., Saijoh Y., Bax N. A., Gittenberger-de Groot A. C., Wisse L. J., Chapman S. C., Hunter J., Shiratori H., Hamada H., Yamada S., et al. (2010). Dysregulation of the PDGFRA gene causes inflow tract anomalies including TAPVR: integrating evidence from human genetics and model organisms. Hum. Mol. Genet. 19, 1286–1301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosman E. A., Penn A. C., Ambrose J. C., Kettleborough R., Stemple D. L., Steel K. P. (2005). Multiple mutations in mouse Chd7 provide models for CHARGE syndrome. Hum. Mol. Genet. 14, 3463–3476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer A. S., Runyan R. B. (2001). TGFbeta Type III and TGFbeta Type II receptors have distinct activities during epithelial-mesenchymal cell transformation in the embryonic heart. Dev. Dyn. 221, 454–459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer A. S., Ayerinskas I. I., Vincent E. B., McKinney L. A., Weeks D. L., Runyan R. B. (1999). TGFbeta2 and TGFbeta3 have separate and sequential activities during epithelial-mesenchymal cell transformation in the embryonic heart. Dev. Biol. 208, 530–545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brannan C. I., Perkins A. S., Vogel K. S., Ratner N., Nordlund M. L., Reid S. W., Buchberg A. M., Jenkins N. A., Parada L. F., Copeland N. G. (1994). Targeted disruption of the neurofibromatosis type-1 gene leads to developmental abnormalities in heart and various neural crest-derived tissues. Genes Dev. 8, 1019–1029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer S., Jiang X., Donaldson S., Williams T., Sucov H. M. (2002). Requirement for AP-2alpha in cardiac outflow tract morphogenesis. Mech. Dev. 110, 139–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brickner M. E., Hillis L. D., Lange R. A. (2000a). Congenital heart disease in adults. First of two parts. N. Engl. J. Med. 342, 256–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brickner M. E., Hillis L. D., Lange R. A. (2000b). Congenital heart disease in adults. Second of two parts. N. Engl. J. Med. 342, 334–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown C. B., Boyer A. S., Runyan R. B., Barnett J. V. (1996). Antibodies to the Type II TGFbeta receptor block cell activation and migration during atrioventricular cushion transformation in the heart. Dev. Biol. 174, 248–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown C. B., Boyer A. S., Runyan R. B., Barnett J. V. (1999). Requirement of type III TGF-beta receptor for endocardial cell transformation in the heart. Science 283, 2080–2082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown C. B., Feiner L., Lu M. M., Li J., Ma X., Webber A. L., Jia L., Raper J. A., Epstein J. A. (2001). PlexinA2 and semaphorin signaling during cardiac neural crest development. Development 128, 3071–3080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruneau B. G., Logan M., Davis N., Levi T., Tabin C. J., Seidman J. G., Seidman C. E. (1999). Chamber-specific cardiac expression of Tbx5 and heart defects in Holt-Oram syndrome. Dev. Biol. 211, 100–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruneau B. G., Nemer G., Schmitt J. P., Charron F., Robitaille L., Caron S., Conner D. A., Gessler M., Nemer M., Seidman C. E., et al. (2001). A murine model of Holt-Oram syndrome defines roles of the T-box transcription factor Tbx5 in cardiogenesis and disease. Cell 106, 709–721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckingham M., Meilhac S., Zaffran S. (2005). Building the mammalian heart from two sources of myocardial cells. Nat. Rev. Genet. 6, 826–837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai C. L., Liang X., Shi Y., Chu P. H., Pfaff S. L., Chen J., Evans S. (2003). Isl1 identifies a cardiac progenitor population that proliferates prior to differentiation and contributes a majority of cells to the heart. Dev. Cell 5, 877–889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C. P., Bruneau B. (2012). Epigenetics and cardiovascular development. Annu. Rev. Physiol. . 74, 41–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C. P., Shen W. F., Rozenfeld S., Lawrence H. J., Largman C., Cleary M. L. (1995). Pbx proteins display hexapeptide-dependent cooperative DNA binding with a subset of Hox proteins. Genes Dev. 9, 663–674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C. P., Jacobs Y., Nakamura T., Jenkins N. A., Copeland N. G., Cleary M. L. (1997). Meis proteins are major in vivo DNA binding partners for wild-type but not chimeric Pbx proteins. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17, 5679–5687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C. P., Neilson J. R., Bayle J. H., Gestwicki J. E., Kuo A., Stankunas K., Graef I. A., Crabtree G. R. (2004). A field of myocardial-endocardial NFAT signaling underlies heart valve morphogenesis. Cell 118, 649–663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C. P., Stankunas K., Shang C., Kao S. C., Twu K. Y., Cleary M. L. (2008). Pbx1 functions in distinct regulatory networks to pattern the great arteries and cardiac outflow tract. Development 135, 3577–3586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang S., McKinsey T. A., Zhang C. L., Richardson J. A., Hill J. A., Olson E. N. (2004). Histone deacetylases 5 and 9 govern responsiveness of the heart to a subset of stress signals and play redundant roles in heart development. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 8467–8476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B., Bronson R. T., Klaman L. D., Hampton T. G., Wang J. F., Green P. J., Magnuson T., Douglas P. S., Morgan J. P., Neel B. G. (2000). Mice mutant for Egfr and Shp2 have defective cardiac semilunar valvulogenesis. Nat. Genet. 24, 296–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q., Chen H., Zheng D., Kuang C., Fang H., Zou B., Zhu W., Bu G., Jin T., Wang Z., et al. (2009). Smad7 is required for the development and function of the heart. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 292–300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y. H., Ishii M., Sun J., Sucov H. M., Maxson R. E., Jr (2007). Msx1 and Msx2 regulate survival of secondary heart field precursors and post-migratory proliferation of cardiac neural crest in the outflow tract. Dev. Biol. 308, 421–437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H. L., Mostoslavsky R., Saito S., Manis J. P., Gu Y., Patel P., Bronson R., Appella E., Alt F. W., Chua K. F. (2003). Developmental defects and p53 hyperacetylation in Sir2 homolog (SIRT1)-deficient mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 10794–10799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chisaka O., Capecchi M. R. (1991). Regionally restricted developmental defects resulting from targeted disruption of the mouse homeobox gene hox-1.5. Nature 350, 473–479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary B., Ito Y., Makita T., Sasaki T., Chai Y., Sucov H. M. (2006). Cardiovascular malformations with normal smooth muscle differentiation in neural crest-specific type II TGFbeta receptor (Tgfbr2) mutant mice. Dev. Biol. 289, 420–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christoffels V. M., Hoogaars W. M., Tessari A., Clout D. E., Moorman A. F., Campione M. (2004). T-box transcription factor Tbx2 represses differentiation and formation of the cardiac chambers. Dev. Dyn. 229, 763–770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clouthier D. E., Hosoda K., Richardson J. A., Williams S. C., Yanagisawa H., Kuwaki T., Kumada M., Hammer R. E., Yanagisawa M. (1998). Cranial and cardiac neural crest defects in endothelin-A receptor-deficient mice. Development 125, 813–824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Combs M. D., Yutzey K. E. (2009). Heart valve development: regulatory networks in development and disease. Circ. Res. 105, 408–421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway S. J., Henderson D. J., Copp A. J. (1997). Pax3 is required for cardiac neural crest migration in the mouse: evidence from the splotch (Sp2H) mutant. Development 124, 505–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooley M. A., Kern C. B., Fresco V. M., Wessels A., Thompson R. P., McQuinn T. C., Twal W. O., Mjaatvedt C. H., Drake C. J., Argraves W. S. (2008). Fibulin-1 is required for morphogenesis of neural crest-derived structures. Dev. Biol. 319, 336–345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costell M., Carmona R., Gustafsson E., González-Iriarte M., Fässler R., Muñoz-Chápuli R. (2002). Hyperplastic conotruncal endocardial cushions and transposition of great arteries in perlecan-null mice. Circ. Res. 91, 158–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crispino J. D., Lodish M. B., Thurberg B. L., Litovsky S. H., Collins T., Molkentin J. D., Orkin S. H. (2001). Proper coronary vascular development and heart morphogenesis depend on interaction of GATA-4 with FOG cofactors. Genes Dev. 15, 839–844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Pompa J. L., Timmerman L. A., Takimoto H., Yoshida H., Elia A. J., Samper E., Potter J., Wakeham A., Marengere L., Langille B. L., et al. (1998). Role of the NF-ATc transcription factor in morphogenesis of cardiac valves and septum. Nature 392, 182–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lange F. J., Moorman A. F., Anderson R. H., Männer J., Soufan A. T., de Gier-de Vries C., Schneider M. D., Webb S., van den Hoff M. J., Christoffels V. M. (2004). Lineage and morphogenetic analysis of the cardiac valves. Circ. Res. 95, 645–654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Délot E. C., Bahamonde M. E., Zhao M., Lyons K. M. (2003). BMP signaling is required for septation of the outflow tract of the mammalian heart. Development 130, 209–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan J., Kordylewska A., Jan Y. N., Utset M. F. (2002). Tetralogy of fallot and other congenital heart defects in Hey2 mutant mice. Curr. Biol. 12, 1605–1610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dor Y., Camenisch T. D., Itin A., Fishman G. I., McDonald J. A., Carmeliet P., Keshet E. (2001). A novel role for VEGF in endocardial cushion formation and its potential contribution to congenital heart defects. Development 128, 1531–1538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dor Y., Klewer S. E., McDonald J. A., Keshet E., Camenisch T. D. (2003). VEGF modulates early heart valve formation. Anat. Rec. A Discov. Mol. Cell. Evol. Biol. 271, 202–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dünker N., Krieglstein K. (2002). Tgfbeta2 –/– Tgfbeta3 –/– double knockout mice display severe midline fusion defects and early embryonic lethality. Anat. Embryol. (Berl.) 206, 73–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg L. M., Markwald R. R. (1995). Molecular regulation of atrioventricular valvuloseptal morphogenesis. Circ. Res. 77, 1–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eldadah Z. A., Hamosh A., Biery N. J., Montgomery R. A., Duke M., Elkins R., Dietz H. C. (2001). Familial Tetralogy of Fallot caused by mutation in the jagged1 gene. Hum. Mol. Genet. 10, 163–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein D. J., Vekemans M., Gros P. (1991). Splotch (Sp2H), a mutation affecting development of the mouse neural tube, shows a deletion within the paired homeodomain of Pax-3. Cell 67, 767–774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein J. A. (1996). Pax3, neural crest and cardiovascular development. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 6, 255–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein J. A., Li J., Lang D., Chen F., Brown C. B., Jin F., Lu M. M., Thomas M., Liu E., Wessels A., et al. (2000). Migration of cardiac neural crest cells in Splotch embryos. Development 127, 1869–1878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson S. L., O’Shea K. S., Ghaboosi N., Loverro L., Frantz G., Bauer M., Lu L. H., Moore M. W. (1997). ErbB3 is required for normal cerebellar and cardiac development: a comparison with ErbB2-and heregulin-deficient mice. Development 124, 4999–5011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etheridge S. L., Ray S., Li S., Hamblet N. S., Lijam N., Tsang M., Greer J., Kardos N., Wang J., Sussman D. J., et al. (2008). Murine dishevelled 3 functions in redundant pathways with dishevelled 1 and 2 in normal cardiac outflow tract, cochlea, and neural tube development. PLoS Genet. 4, e1000259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feiner L., Webber A. L., Brown C. B., Lu M. M., Jia L., Feinstein P., Mombaerts P., Epstein J. A., Raper J. A. (2001). Targeted disruption of semaphorin 3C leads to persistent truncus arteriosus and aortic arch interruption. Development 128, 3061–3070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer A., Klamt B., Schumacher N., Glaeser C., Hansmann I., Fenge H., Gessler M. (2004). Phenotypic variability in Hey2 –/– mice and absence of HEY2 mutations in patients with congenital heart defects or Alagille syndrome. Mamm. Genome 15, 711–716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fish J. E., Santoro M. M., Morton S. U., Yu S., Yeh R. F., Wythe J. D., Ivey K. N., Bruneau B. G., Stainier D. Y., Srivastava D. (2008). miR-126 regulates angiogenic signaling and vascular integrity. Dev. Cell 15, 272–284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong G. H., Rossant J., Gertsenstein M., Breitman M. L. (1995). Role of the Flt-1 receptor tyrosine kinase in regulating the assembly of vascular endothelium. Nature 376, 66–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraisse A., Massih T. A., Kreitmann B., Metras D., Vouhé P., Sidi D., Bonnet D. (2003). Characteristics and management of cleft mitral valve. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 42, 1988–1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman J. M., Arbiser J., Epstein J. A., Gutmann D. H., Huot S. J., Lin A. E., McManus B., Korf B. R. (2002). Cardiovascular disease in neurofibromatosis 1: Report of the NF1 Cardiovascular Task Force. Genet. Med. 4, 105–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galli D., Domínguez J. N., Zaffran S., Munk A., Brown N. A., Buckingham M. E. (2008). Atrial myocardium derives from the posterior region of the second heart field, which acquires left-right identity as Pitx2c is expressed. Development 135, 1157–1167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]