Abstract

Introduction: differentiating mild cognitive impairment (MCI) from normal cognition (NC) is difficult. The AB Cognitive Screen (ABCS) 135, sensitive in differentiating MCI from dementia, was modified to improve sensitivity and specificity, producing the quick mild cognitive impairment (Qmci) screen.

Objective: this study compared the sensitivity and specificity of the Qmci with the Standardised MMSE and ABCS 135, to differentiate NC, MCI and dementia.

Methods: weightings and subtests of the ABCS 135 were changed and a new section ‘logical memory’ added, creating the Qmci. From four memory clinics in Ontario, Canada, 335 subjects (154 with MCI, 181 with dementia) were recruited and underwent comprehensive assessment. Caregivers, attending with the subjects, without cognitive symptoms, were recruited as controls (n = 630).

Results: the Qmci was more sensitive than the SMMSE and ABCS 135, in differentiating MCI from NC, with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.86 compared with 0.67 and 0.83, respectively, and in differentiating MCI from mild dementia, AUC of 0.92 versus 0.91 and 0.91. The ability of the Qmci to identify MCI was better for those over 75 years.

Conclusion: the Qmci is more sensitive than the SMMSE in differentiating MCI and NC, making it a useful test, for MCI in clinical practice, especially for older adults.

Keywords: quick mild cognitive impairment screen, mild cognitive impairment, standardised mini-mental state examination, AB cognitive screen 135, sensitivity

Introduction

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) represents a heterogeneous group of disorders of memory impairment [1]. Individuals with MCI have variable, subtle, cognitive changes. Although many go on to develop dementia, the rate of progression varies considerably. The annual conversion rate from MCI to dementia is estimated at between 5 and 10% [2]. The reason for this is partly due to variability in the definitions used [3] and in the diagnostic methods employed. When people present with memory loss, it is important to differentiate between MCI and dementia, as treatment choices differ. In particular, patients with dementia benefit from cholinesterase inhibitors, while those with MCI do not have a sustained response [4]. Clinical and functional assessments are used to differentiate between these two groups. While those with MCI generally do not have functional impairment, evidence suggests that subtle functional changes are present in 31% [5].

Several cognitive screening tools have been used in an attempt to differentiate normal cognition (NC), and MCI from dementia [6, 7]. Not all are able to distinguish between dementia and MCI, and it has been suggested that no single screening tool will fit all situations [8]. One of the most widely employed tools is the Folstein Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) [9]. The Standardised Mini-Mental State Examination (SMMSE) improved inter-rater reliability by the inclusion of explicit administration and scoring guidelines [10, 11]. The MMSE and SMMSE have a limited role in identifying MCI [12], lacking sufficient sensitivity to differentiate between NC and MCI, in particular, where individuals have higher levels of academic achievement [13]. The AB Cognitive Screen 135 (ABCS 135) was developed to address this problem [6].

Description of the ABCS 135

The ABCS 135, a short screening test, administered in 3–5 min, is more sensitive in differentiating NC from dementia, and more importantly, MCI from dementia than the SMMSE. The ABCS 135 evaluates five domains, orientation, registration, clock drawing, delayed recall (DR) and verbal fluency (VF) [6] (Table 1). Although, the ABCS 135 is sensitive and quick to employ, it could be argued, that much of the test is redundant. All the domains differentiate NC and MCI from dementia, but orientation, registration and clock drawing did not enhance the discriminatory properties of the test in differentiating NC from MCI. For this reason, the Quick Mild Cognitive Impairment (Qmci) screen was developed to enhance the sensitivity of the ABCS 135.

Table 1.

Comparison of ABCS version 135 and Qmci

| ABCS 135 | Score | Qmci | Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| Orientation | 25 | Orientation | 10 |

| Registration | 25 | Registration | 5 |

| Clock drawing | 30 | Clock drawing | 15 |

| Delayed recall | 25 | Delayed recall | 20 |

| Verbal fluency | 30 | Verbal fluency | 20 |

| Logical memory | 30 |

Development of the Qmci

The Qmci, is a modified version of the ABCS 135, scored out of 100 points, placing greater emphasis on verbal memory and fluency, along with DR, (Supplementary data are available in Age and Ageing online, Appendix 1). As analysis of the ABCS 135 subtests found that DR and VF, were more sensitive at differentiating MCI from NC than orientation, registration and clock drawing [14], these three subtests had their weightings reduced by a factor of 2.5, 5 and 2, respectively (Table 1). Logical memory (LM), which is highly sensitive and specific in differentiating NC from MCI [15] was added and given the largest weighting, necessitating the reduction of weightings for all the other subtests. LM is a linguistic memory test (for stories) [16] and is unaffected by age or education [17]. VF and DR are highly sensitive tests for distinguishing MCI from NC [14], and although their weighting were cut, by a factor of 0.66 and 0.8 respectively, to allow for the introduction of LM, their relative weighting, compared to the other subtests, increased.

The Qmci, has six domains; five orientation items (country, year month, day and date), five registration items and a clock drawing test, each scored within 1 min. It also has a recall section (timed at 20 s), a test of VF (60 s) and a LM test with 30 s for administration and 30 s for response. It can be administered and scored in 5 min.

The primary objective of this study was to compare the sensitivity and specificity of the new Qmci with the ABCS 135 and SMMSE to distinguish individuals with NC from those with MCI and dementia.

Methods

Subjects

Subjects attending four memory clinics across Ontario, Canada (Hamilton, Paris, Niagara Falls and Grand Bend) referred for the investigation of cognitive loss were recruited between 2004 and 2010. Normal controls were selected by convenience sampling. All caregivers, or those attending with the subjects, were asked if they themselves had memory problems. Those without memory problems were invited to participate as normal controls. A diagnosis of dementia was based on NINCDS [18] and DSM-IV criteria [19]. Dementia severity was correlated with the Reisberg FAST scale [20]. A diagnosis of MCI was made by a consultant geriatrician if patients had recent, subjective but corroborated memory loss without obvious loss of social or occupational function. Subjects were excluded if they were under 55 years of age, unable to communicate verbally in English, if they had depression (as defined by a Geriatric Depression Scale greater than seven [21]), or if a reliable collateral was not available. Subjects with Parkinson's disease and Lewy body dementia were excluded as these typically present with exaggerated functional deficits and a different MCI syndrome [22]. Ethics approval was obtained and subjects provided verbal consent. Assent was obtained from individuals with cognitive impairment.

Data collection

Each subject had demographic data collected which included age, gender and number of years of education. Each had a physical examination and work-up for causes of cognitive impairment including a brain CT (computerised tomogram) scan, an electrocardiogram and blood tests. Each subject had the SMMSE and the Qmci administered sequentially but randomly by the same trained rater, who was blind to the eventual diagnosis.

Statistical analysis

Data were entered into SPSS version 16.0 [23]. Subjects were subdivided according to age, > or <75 years and educational level achieved, > or <12 years (approximating high school/secondary school level). ABCS 135 data, based on the Qmci, were reconstituted from data collected from the Qmci. The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to test normality and found that the majority of data were non-parametric. This was analysed using the Mann–Whitney U test, whereas Student's t-tests compared scores for parametric data. Data were also analysed using Receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curves.

Results

A total of 965 participants, 551 females (57%) and 414 males (43%), were included in the study. Overall, 630 subjects had NC (65%), 154 had MCI (16%) and 181 (19%) had dementia. The median age of the total population was 70.5 years; those with NC had a mean age 67 years compared with 75.5 for the MCI group and 79 for the dementia group. The dementia group was older than the NC (P < 0.001) and MCI (P < 0.001) groups. They also had spent less time in education, 10 years compared with the normal control (13 years, P < 0.001) and MCI (12 years, P < 0.005) populations. Dementia was divided into mild (n = 141), moderate (n = 33) and severe cognitive impairment (n = 7). The normal population had a median SMMSE score of 29 and a median Qmci score of 76, the MCI group scored 28 and 62 and the dementia group scored 22 and 36 on the SMMSE and Qmci, respectively. These results and demographics are summarised with inter-quartile range (IQR) in Table 2. All three cognitive tests (SMMSE, ABCS 135 and the Qmci) were sensitive in differentiating MCI from NC. The Qmci was best able to do this in a clinically useful way. The median difference in scores between subjects with either MCI or NC was one for the SMMSE compared with 14 for the Qmci. This represents a difference of 3.33% of the total score of 30 with the SMMSE and a 14% difference for the Qmci (scored out of 100).

Table 2.

Characteristics of the normal, MCI and dementia groups, including median Qmci, SMMSE and ABCS 135 scores and inter-quartile range (IQR), (Q1–Q3 = IQR; Q1 = 1st Quartile, Q3 = 3rd Quartile)

| Group | Normal | MCI | Dementia |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of subjects | 630 | 154 | 181 |

| Age | |||

| Mean | 67.4 | 73.6 | 78.1 |

| Median | 67 | 75.5 | 79 |

| Range | 44–92 | 50–88 | 49–93 |

| Proportion female (57.0%) n = 551 | |||

| Mean age | 67.0 | 73.3 | 78.7 |

| Median age | 66.5 | 75 | 80 |

| Range | 50–92 | 50–87 | 49–93 |

| Proportion male (43.0%) n = 414 | |||

| Mean age | 68.0 | 73.9 | 77.6 |

| Median age | 68 | 76 | 79 |

| range | 44–85 | 51–88 | 53–92 |

| Education (years in education) | |||

| Mean | 13.8 | 12.2 | 11.0 |

| Median | 13 | 12 | 10 |

| Range | 5–29 | 5–26 | 3–20 |

| Qmci (median with IQR) | 76 (83–69 = 14) | 62 (68–53 = 15) | 36 (45–23 = 22) |

| SMMSE (median with IQR) | 29 (30–28 = 2) | 28 (29–27 = 2) | 22 (25–18 = 7) |

| ABCS 135 (median with IQR) | 115.5 (121–109 = 12) | 102 (111–94 = 17) | 70 (83.5–45.5 = 38) |

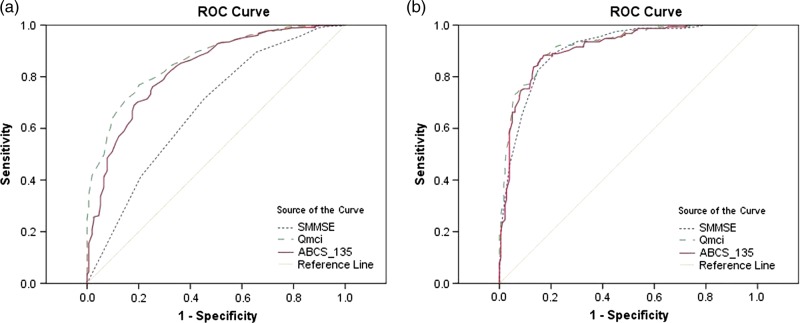

All three tests distinguished dementia from MCI. Patients with MCI, scored a median 26 points more on the Qmci than those with dementia (P < 0.001), whereas there was a 40 point difference in the Qmci between those with NC and dementia (P < 0.001). Figure 1 shows two ROC curves demonstrating the sensitivities and specificities of the Qmci, ABCS 135 and SMMSE in differentiating MCI from NC and MCI from dementia. Although the Qmci, ABCS 135 and the SMMSE were able to distinguish MCI from NC, the Qmci was more sensitive with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.86 (95% CI: 0.83–0.89) compared with 0.83 (95% CI: 0.79–0.86) for the ABCS 135 and 0.67 (95% CI: 0.62–0.72) for the SMMSE. The Qmci was also more sensitive at differentiating MCI from dementia, AUC of 0.92 (95% CI: 0.89–0.95) versus 0.91 (95% CI: 0.88–0.94) for the ABCS 135 and 0.91 (95% CI: 0.88–0.94) for the SMMSE. When moderate and severe dementia cases were removed from analysis, the AUC of the Qmci and SMMSE for differentiating MCI from mild dementia cases alone was unchanged at 0.92 (95% CI: 0.89–0.95) and 0.90 (95% CI: 0.85–0.93), respectively.

Figure 1.

ROC curve demonstrating sensitivities and specificities of the Qmci, ABCS 135 and SMMSE in differentiating (a). MCI from normal cognition, (b). MCI and dementia.

Subanalysis for age (> or < 75 years of age) and education (> or <12 years) showed that the Qmci was more sensitive, with a larger AUC, than the SMMSE. The Qmci was best for distinguishing MCI from NC in an older age group, (over 75 years), with more time, (>12 years), in education, with an AUC of 0.86 (95% CI: 0. 79–0.92) compared with 0.55 (95% CI: 0.44–0.66) for the SMMSE. The only subjects where the difference in sensitivity between the Qmci and SMMSE was less obvious was for younger individuals, (<75 years) with less than 12 years in education, AUC of 0.72 (95% CI: 0.62–0.82) for the Qmci versus 0.65 (95% CI: 0.54–0.76) for the SMMSE. The SMMSE, ABCS 135 and Qmci were all able to differentiate MCI from dementia, irrespective of age or educational status (P < 0.001).

Conclusion

This study compares the refined ABCS tool, the newly developed Qmci, to the established SMMSE and the original ABCS 135 in their ability to discriminate NC and MCI from dementia. The results presented here show that the Qmci is more sensitive than the SMMSE and the ABCS 135 in differentiating MCI from NC, whereas all three are able to distinguish NC from dementia. Although, the SMMSE was useful in differentiating MCI and NC groups, from dementia subjects, it was not able to separate MCI from NC. The small percentage difference (3.33%) of the total score for the SMMSE between those with NC and MCI shows that the SMMSE is not clinically useful in distinguishing MCI from normals. The Qmci had a wider and more clinically significant percentage difference in median scores to help discriminate MCI from dementia. Similarly, the median SMMSE score for MCI cases and controls, even taking the IQR into account, at 28 out of 30 (IQR: 29–27 = 2) lies within the accepted cut-off interval for NC, at greater than 25 out of 30 [11, 24]. This again suggests that the SMMSE is not adequately sensitive in detecting MCI. The Qmci was also more sensitive than the SMMSE in differentiating MCI from NC among older adults, over 75 years, especially those with more than 12 years in education.

Of note, age and educational level did not affect the ability of the Qmci or SMMSE to discriminate between MCI and dementia. The dementia group in this study was significantly older and had spent less time in formal education than either the MCI group or the NC group. The dementia group was weighted towards the mild spectrum of dementia. This is important, as differentiating MCI from mild dementia is more challenging than differentiating it from severe dementia. Removing moderate and severe dementia cases from analysis, showed that the Qmci retains and even improves its increased sensitivity, for differentiating MCI from mild dementia, confirming that this tool is useful across the whole range of the cognitive impairment spectrum.

Our paper has several limitations. First, we cannot be certain that all patients were classified appropriately as having normal or impaired cognition. This is difficult to do, especially where controls are drawn from a sample of convenience. Controls in this study did not have any complaints of memory loss. We acknowledge that one of the major clinical challenges is to separate symptomatic patients with NC from those with MCI, especially as approximating 50%, attending some memory clinics with subjective memory problems, have NC [25]. However, within the confines of a sample of convenience, the subjects chosen as normal controls were tested rigorously, screened for cognitive impairment and depression and underwent the same detailed assessment as cases with MCI and dementia. Future validation of the Qmci, will target controls with NC, referred to the memory clinic.

Second, we used NINCDS and DSM IV criteria to make a diagnosis of dementia. While there is no defined gold standard, these criteria are broadly accepted and have been validated internationally [26]. Third, the diagnosis of dementia was based on a single assessment which may have reduced accuracy and one rater scored both cognitive tests which may have led to ‘practice’ effects. However, the raters were blind to the eventual diagnosis made at the clinical assessment. Finally, we compared the Qmci to the SMMSE and ABCS 135 which are not gold standards for differentiating MCI from NC or dementia. This said, the SMMSE is the most widely used screen for dementia and no gold standard yet exists for the diagnosis of MCI.

The strengths of this study are the large sample size, comprehensive assessment and bigger number of controls than the original ABCS 135 validation paper. The diagnosis of MCI and diagnosis and grading of dementia are based on both functional and cognitive assessments. This study was performed at multiple sites. Future research will focus on comparing the Qmci to other short cognitive tests such as the Montreal Cognitive Assessment [27] and further refinement of the different domains in the test.

The study confirms that the Qmci, a short cognitive screen, is more sensitive in differentiating NC from MCI, than the widely used SMMSE. Compared with the ABCS 135, the Qmci is more sensitive in differentiating MCI, takes the same time to complete and is conveniently scored out of 100, making it easy to interpret in clinical practice.

Key points.

The Qmci is more sensitive than the SMMSE in differentiating MCI from NC.

The Qmci is more sensitive than the SMMSE in differentiating MCI from dementia.

The Qmci is more sensitive at differentiating MCI from NC in older adults, over 75.

The Qmci needs to be compared with other short-cognitive screening tools.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data mentioned in the text is available to subscribers in Age and Ageing online.

References

- 1.Petersen RC. Mild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entity. J Int Med. 2004;256:183–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mitchell AJ, Shiri-Feshki M. Rate of progression of mild cognitive impairment to dementia–meta-analysis of 41 robust inception cohort studies. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2009;119:252–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fisk JD, Merry HR, Rockwood K. Variations in case definition affect prevalence but not outcomes of mild cognitive impairment. Neurology. 2003;61:1179–84. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000089238.07771.c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peterson RC, Thomas RG, Grundman M, et al. for the Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study Group. Vitamin E and donepezil for the treatment of mild cognitive impairment. N Eng J Med. 2005;352:2379–88. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Artero S, Touchon J, Ritchie K. Disability and mild cognitive impairment: a longitudinal, population-based study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;16:1092–7. doi: 10.1002/gps.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Molloy DW, Standish TIM, Lewis DL. Screening for mild cognitive impairment: comparing the SMMSE and the ABCS. Can J Psychiatry. 2005;50:52–58. doi: 10.1177/070674370505000110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lonie JA, Tierney KM, Ebmeier KP. Screening for mild cognitive impairment: a systematic review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24:902–15. doi: 10.1002/gps.2208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cullen B, O'Neill B, Evans JJ, Coen RF, Lawlor BA. A review of screening tests for cognitive impairment. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78:790–9. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2006.095414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. ‘Mini-mental state’. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–98. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Molloy DW, Alemayehu E, Roberts R. Reliability of a standardized Mini-Mental State Examination compared with the traditional Mini-Mental State Examination. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:102–5. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.1.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Molloy DW, Standish TIM. A guide to the Standardized Mini-Mental State Examination. Int Psychogeriatr. 1997;9(S1):87–94. doi: 10.1017/s1041610297004754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mitchell AJ. A meta-analysis of the accuracy of the mini-mental state examination in the detection of dementia and mild cognitive impairment. J Psychiatr Res. 2009;43:411–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crum RM, Anthony JC, Bassett SS, Folstein MF. Population-based norms for the Mini-Mental State Examination by age and educational level. JAMA. 1993;269:2386–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Standish T, Molloy DW, Cunje A, Lewis DL. Do the ABCS 135 short cognitive screen and its subtests discriminate between normal cognition, mild cognitive impairment and dementia? Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;22:189–94. doi: 10.1002/gps.1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cunje A, Molloy DW, Standish TI, Lewis DL. Alternative forms of logical memory and verbal fluency tasks for repeated testing in early cognitive changes. Int Psychogeriatr. 2007;19:65–75. doi: 10.1017/S1041610206003425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wechsler D. Wechsler Memory Scale—Third Edition Manual. San Antonio, TX, USA: The Psychological Corporation; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lichtenberg PA, Christensen B. Extended normative data for the logical memory subtests of the Wechsler Memory Scale–Revised: responses from a sample of cognitively intact elderly medical patients. Psychol Rep. 1992;71:745–6. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1992.71.3.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McKhann G, Drachman DA, Folstein MF, et al. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer's Disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939–44. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reisberg B. Functional Assessment Staging (FAST) Psychopharmacol Bull. 1988;24:653–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yesavage JA. Geriatric Depression Scale. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1988;24:709–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caviness JN, Driver-Dunckley E, Connor DJ, et al. Defining mild cognitive impairment in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2007;22:1272–7. doi: 10.1002/mds.21453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.SPSS Inc. Chicago IL: SPSS Inc; 2008. SPSS for Windows 16.0. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mungas D. In-office mental status testing: a practical guide. Geriatrics. 1991;46:54–8. 63, 66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steenland K, Macneil J, Bartell S, Lah J. Analyses of diagnostic patterns at 30 Alzheimer's disease centers in the US. Neuroepidemiology. 2010;35:19–27. doi: 10.1159/000302844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O Connor DW, Blessed G, Cooper B, Jonker C, Morris JC. Cross-national interrater reliability of dementia diagnosis in the elderly and factors associated with disagreement. Neurology. 1996;47:1194–9. doi: 10.1212/wnl.47.5.1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nasreddine ZS, Philips NA, Bedirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:695–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.