Abstract

Objective

This study evaluated the potential impact of proposed DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

Method

This study focused on a sample of 977 participants evaluated during the DSM-IV field trial; 657 carried a clinical diagnosis of an ASD, and 276 were diagnosed with a non-autistic disorder. Sensitivity and specificity for proposed DSM-5 diagnostic criteria were evaluated using field trial symptom checklists as follows: (a) individual field trial checklist items (e.g., nonverbal communication), (b) checklist items grouped together as described by a single DSM-5 symptom (e.g., nonverbal and verbal communication), (c) individual DSM-5 criterion (e.g., social-communicative impairment), and (d) overall diagnostic criteria.

Results

When applying proposed DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for ASD, 60.6% (95% confidence interval: 57–64%) of cases with a clinical diagnosis of an ASD met revised DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for ASD. Overall specificity was high, with 94.9% (95% confidence interval: 92–97%) of individuals accurately excluded from the spectrum. Sensitivity varied by diagnostic subgroup (Autistic Disorder =.76; Asperger’s Disorder = .25; PDD-NOS = .28) and cognitive ability (IQ < 70 = .70; IQ ≥ 70 = .46).

Conclusions

Proposed DSM-5 criteria substantially alter the composition of the autism spectrum. Revised criteria improve specificity, but exclude a substantial portion of cognitively able individuals and those with ASDs other than Autistic Disorder. A more stringent diagnostic rubric holds significant public health ramifications regarding service eligibility and compatibility of historical and future research.

Keywords: autism spectrum disorder, DSM-5, sensitivity, specificity

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) are one of the most common neurodevelopmental disorders, with an estimated prevalence of 1 in 110 children.1 Estimates from individual epidemiological studies have ranged as high as 2.64 percent,2 raising public concerns about an autism “epidemic.”3 Although current estimates represent an increase from prior estimates, the nature of this change is unclear. Multiple factors other than a true increase in incidence likely influence this number: greater recognition due to growing public and professional awareness of ASDs, use of the label in educational settings to establish service eligibility, and a broadening of the diagnostic construct beyond strictly defined autistic disorder.4 Changes in diagnostic criteria have also played a role. For example, inclusion of Asperger’s Disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV)5, likely contributed to subsequent impressions of increased prevalence by encouraging explicit identification of higher functioning children with significant social disabilities whose language, in many respects, was less impaired than in classic autism.6 Considering the possibility that increased prevalence reflects improved recognition and increased awareness, higher prevalence might reflect that individuals likely to benefit from intervention are being identified and provided access to therapeutic services.7

The current DSM diagnostic taxonomy8 places ASDs in the category of pervasive developmental disorders (PDDs). The class of PDDs includes five disorders, with the term, ASD, applied to Autistic Disorder, Asperger’s Disorder, and Pervasive Developmental Disorder – Not Otherwise Specified (PDD-NOS), excluding Rett’s syndrome and Childhood Disintegrative Disorder. Diagnosis of Autistic Disorder requires a minimum of six behavioral criteria, at least two from the domain of social impairment and one from each of the other two areas of impairment (communication and restricted/repetitive behaviors). Contrasting the disorder from more general intellectual impairment, these social and communicative deficits are considered with respect to overall developmental level. Asperger’s Disorder is identical to Autistic Disorder in terms of requiring two symptoms from the social domain and one from the stereotyped behavior domain. Asperger’s Disorder differs from Autistic Disorder in (a) omission of diagnostic criteria in the communication domain; (b) absence of a requirement for onset prior to age three; and (c) addition of criteria specifying harmful dysfunction, absence of a language delay, and absence of deficits in cognitive development or non-social adaptive function. Furthermore, a precedence rule indicates that, to meet criteria for Asperger’s Disorder, one cannot meet criteria for another specific PDD.9 PDD-NOS denotes a sub-threshold form of autism, or a manifestation of PDD that is atypical in terms of onset patterns or symptomatology such that defining features of other PDDs are not met. Diagnosis requires that the individual exhibit autistic-like social difficulty along with impairment in either communication or restricted/repetitive interests or behaviors.10

Various diagnostic approaches have been adopted in editions of the DSM since first official recognition of autism in DSM-III11; prior to that time, the term childhood schizophrenia was used very broadly to encompass a range of conditions, including autism. Official recognition of autism as a category in 1980 significantly advanced research, as did the adoption of an explicitly phenomenological and atheoretical approach to diagnosis.12 The DSM-III applied a monothetic approach (i.e., an individual must meet all diagnostic criteria) and consequently focused primarily on classic autism as manifest in more severely affected or younger individuals. A developmental orientation was introduced in DSM-III-R13 with a more developmental, polythetic criteria set (i.e., individuals must meet only a subset of a range of criteria), which also broadened the diagnostic concept.14–17 The modifications in DSM-IV5 more directly addressed cognitively able individuals with social disability. The diagnostic validity of ASD subtypes in the DSM-IV/ICD-10 system has been challenged18,19, but the current approach has been highly effective in fostering research20.

The DSM-5 is anticipated for release in 2013, and proposed diagnostic criteria have been circulated for comment.21 In this new approach, diagnostic subcategories would cease to exist in lieu of a single broad category of ASD, which would replace the term PDD. In addition to altering the taxonomic structure of the autism spectrum, proposed changes will alter the diagnostic construct of ASD itself. The traditional triad of symptom domains (i.e., social, communication, and atypical behaviors) would be reduced to two domains by combining social and communication symptoms into a single area (Social/Communicative Deficits). A second category would be called “restricted repetitive behaviors” (RRB) and would include sensory abnormalities, currently omitted from DSM-IV-TR criteria. In contrast to current polythetic criteria for social and communicative function, DSM-5 would re-adopt a monothetic approach that would require meeting all of the social-communicative criteria. A polythetic approach would remain for RRB criteria, requiring two of four symptoms be present; this differs from current criteria which require only a single RRB symptom for Asperger’s Disorder and Autistic Disorder and do not require any RRB symptoms for a diagnosis of PDD-NOS. The proposed DSM-5 rubric also includes a universal onset criterion (i.e., symptoms present in “early childhood” though they may not “become fully manifest until social demands exceed limited capacities”), previously included only for Autistic Disorder. A new, related diagnosis, Social Communication Disorder (SCD), is also proposed for inclusion in DSM-5.22 This disorder, mutually exclusive with ASD (i.e., children meeting criteria for ASD are ruled out), will be defined by impairment of pragmatics and observed difficulties in social applications of verbal and nonverbal communication in naturalistic contexts. These difficulties must be judged to impair social relationships and comprehension and must not be accounted for by problems with word structure, grammar, or general cognitive ability. To qualify for a diagnosis, social communication difficulties must detrimentally impact communication, social involvement, academic achievement, or occupational performance, and symptoms must be present in early childhood, though they may not developmentally manifest until social expectations exceed limited capacities. SCD is largely consistent with a DSM-IV-TR conceptualization of PDD-NOS absent RRB symptoms.

These changes have been enacted in response to longstanding criticism of the reliability and robustness of DSM-IV-TR diagnostic subtypes and an emphasis on objectivity of diagnosis rather than clinical judgment.23,24 By reducing the metric of diagnosis to the level of the autism spectrum, the diagnostic rubric will arguably be more appropriately matched to existing psychometric standards, permitting reliable and valid differentiation of ASD from typical development and other developmental and psychiatric disorders and representing the commonality among ASDs as a single diagnostic category.21 Several potential difficulties with this approach have been raised. Given the relatively short period of time in which current diagnostic subtypes have existed, weakness in these diagnostic constructs might be resolved with additional time for study.25 It has also been argued that, despite limitations in inter-rater reliability, diagnostic subtypes remain clinically useful; in this regard, diagnostic criteria might be refined to better characterize, rather than ignore, nuanced distinctions in social motivation, nature of circumscribed interests, communicative style, and overt age of onset.6 Omission of diagnostic subtypes, such as Asperger Syndrome, may be pragmatically and socio-emotionally detrimental to individuals carrying the diagnosis and their families.26 Finally, as has been the case with previous revisions of the DSM, diagnoses issued according to current criteria would, in some cases, differ from those based on proposed criteria, reducing the comparability of future studies with prior research. This has the potential to complicate interpretation of the massive quantity of research on autism and related conditions published according to DSM-IV and ICD-10 criteria.27

The changed diagnostic criteria may also fundamentally alter the composition of the autism spectrum. Given changes to actual symptom descriptions and to the constellation and quantity of symptoms required for diagnosis, it is possible that the autism spectrum would represent a different population of individuals. For example, inclusion of sensory behaviors in the rubric might enable inclusion of additional individuals with sensory symptoms that had been excluded according to DSM-IV-TR. Conversely, with the change to monothetic social-communicative criteria (versus polythetic) and two RRB symptoms required for diagnosis (versus none), it is possible that some individuals currently meeting criteria would not meet diagnostic criteria for DSM-5. In both cases, the public health ramifications are considerable. Expanding diagnostic boundaries would further stretch limited therapeutic resources, while reducing the number of individuals in the general population who meet criteria for ASD could result in lost eligibility for service among individuals who stand to benefit. In the current study, we examined the sensitivity and specificity of DSM-5 diagnostic criteria and potential impact on prevalence rates using available data from the DSM-IV field trial.28

Method

The data for the analyses in this study were obtained from the multisite field trial of the DSM-IV.28 In the context of the field trial, 977 patients were evaluated for possible PDD. This re-analysis focused on 933 cases, omitting individuals diagnosed with non-autistic PDDs (Rett’s Disorder, n=13; Childhood Disintegrative Disorder, n=16), as well as individuals missing data required for the present analyses (n=15). Sample characteristics are presented in Table 1. It included 657 individuals who received a clinical diagnosis (according to then-current diagnostic criteria, i.e., DSM-III-R and ICD-10) of an autism spectrum disorder (Autistic Disorder, n=450; Asperger’s Disorder, n=48; PDD-NOS/atypical autism, n=159) and a comparison sample of 276 individuals who received a clinical diagnosis other than ASD (Mental retardation, n=129; Developmental language disorders, n=86; Childhood schizophrenia n=9; “Other disorders”, n=52). Consistent with the skewed sex ratio characteristic of ASD, ASD and non-ASD groups differed in terms of gender ( X2(1)= 17.7, p < .001) but were comparable in terms of age (t (931) = .57, p > .05) and IQ ( X2(5) = 10.0, p > .05). Both groups represented a wide age span, with the ASD group ranging from 12 months to 43 years, 5 months and the non-ASD group ranging from 12 months to 39 years, 5 months.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics.

| ASD (n = 657) | non-ASD (n = 276) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Percent | N | Percent | ||

| Clinical Diagnosis | |||||

| Autism | 450 | 68.5 | |||

| Asperger’s disorder | 48 | 7.3 | |||

| PDD-NOS/atypical autism | 159 | 24.2 | |||

| Mental retardation | 129 | 46.7 | |||

| Developmental language disorders | 86 | 31.2 | |||

| Childhood schizophrenia | 9 | 3.3 | |||

| Other disorders | 52 | 18.9 | |||

| Sexa | X2(1) = 17.7, p < .001 | ||||

| Male | 533 | 81.1 | 191 | 69.2 | |

| Female | 114 | 17.4 | 82 | 29.7 | |

| IQb | X2(5) = 10.0, p > .05 | ||||

| <25 | 37 | 5.6 | 14 | 5.1 | |

| 25–39 | 104 | 15.8 | 31 | 11.2 | |

| 40–54 | 137 | 20.9 | 48 | 17.4 | |

| 55–69 | 115 | 17.5 | 48 | 17.4 | |

| 70–85 | 97 | 14.8 | 57 | 20.7 | |

| 85+ | 140 | 21.3 | 72 | 26.1 | |

|

| |||||

| M | SD | M | SD | ||

| Age | 9.2 | 6.9 | 9.5 | 8.2 | t(931) = .57; p > .05 |

Note: PDD-NOS – pervasive developmental disorder, not otherwise specified

IQ data unavailable for 27 individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and 6 individuals without ASD.

Sex not reported for 10 individuals with ASD and 3 individuals without ASD.

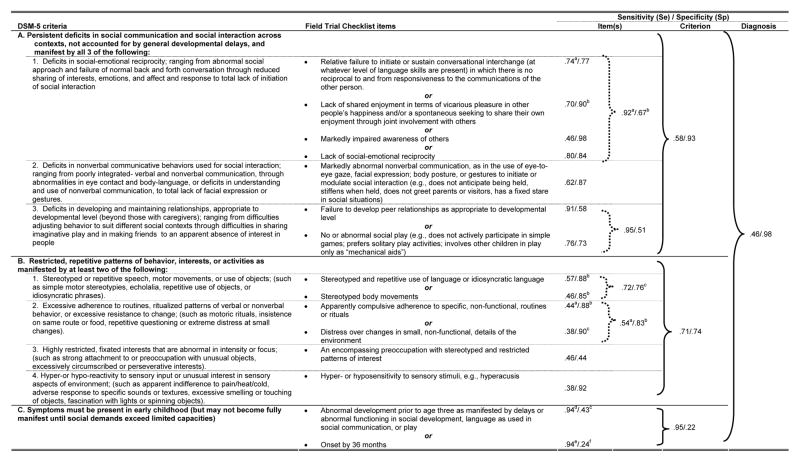

In the context of the field trial evaluations, 125 clinicians across 21 international sites evaluated cases to assign a clinical diagnosis. Each clinician also completed an extensive symptom checklist (61 items) encompassing DSM-III11 and DSM-III-R13 criteria, as well as the proposed diagnostic criteria for ICD-1029 and DSM-IV5 (copies of the complete checklist are available from the authors by request). Clinical diagnosis demonstrated good overall sensitivity and specificity, being highly consistent with the ICD-10 criteria that were current at that time.30 There was also strong inter-clinician agreement (kappa=.95) on whether or not individuals met clinical diagnosis for a PDD.31 The DSM-IV criteria set developed in the field trial had sensitivity of .93 and specificity of.78 for autism; additional methodological details regarding data acquisition are provided in the original study.28 For the current study, we developed an algorithm using individual items from this symptom set to correspond to the proposed DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for ASD. In developing this algorithm, all authors (two of whom are expert diagnosticians in ASD) developed a conceptual approach to (a) select items most closely matching proposed DSM-5 criteria in terms of both symptom constructs and wording and (b) consistent with actual diagnostic practice, in which clinicians judge correspondence among behaviors and a finite symptom set, to base the diagnostic algorithm on these specific items (rather than an exhaustive and redundant list of all 61 checklist items that could possibly correspond to a particular DSM-5 symptom). Having established these principles, each author independently selected items from the checklist to correspond to DSM-5 criteria, and all authors met as a group to develop a consensus algorithm (See Tables 2 and 3). For five proposed DSM-5 diagnostic criteria, multiple field trial symptom checklist items were required to ensure the construct was adequately represented (i.e., proposed DSM-5 criteria A1, A3, B1, B2, and C). In all of the instances that multiple checklist items were included, it was required that the case met only one of the items to meet the criteria. For the third proposed DSM-5 criterion (C), “Symptoms must be present in early childhood (but may not become fully manifest until social demands exceed limited capacities),” an onset of 36 months was applied. For the symptom checklist-derived algorithm, we determined sensitivity and specificity for (a) individual field trial checklist items (e.g., nonverbal communication), (b) checklist items grouped together as described by a specific symptom criterion (e.g., nonverbal and verbal communication), (c) symptom domain criterion (e.g., social-communicative impairment), and (d) overall diagnostic criteria. Sensitivity was calculated as the proportion of individuals with a clinical diagnosis of ASD meeting criteria according to the diagnostic algorithm, i.e., the proportion of true positives. Specificity was calculated as the proportion of individuals who did not carry a clinical diagnosis of ASD and did not meet criteria according to the diagnostic algorithm, i.e. the proportion of true negatives.

Table 2.

Sensitivity (Se) and Specificity (Sp) of proposed DSM-5 diagnostic criteria of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) for individuals with and without a clinical diagnosis of an ASD (Se – n = 657 unless otherwise noted; Sp – n = 276 unless otherwise noted)

|

n = 655;

n = 656;

n = 274;

n =275;

n = 651;

n = 652;

n = 608;

n = 264;

n = 650;

n = 259

Table 3.

Sensitivity (Se) and Specificity (Sp) of proposed DSM-5 diagnostic criteria of autism spectrum disorder for individuals with and without a clinical diagnosis of an autism spectrum disorder with IQ ≥ 70 (Se – n = 237 unless otherwise noted; Sp – n = 129 unless otherwise noted)

|

n = 236;

n = 128;

n = 127;

n =211;

n = 234;

n = 125

Results

Sensitivity and specificity for the DSM-5 algorithm are displayed in Table 2, with 95% confidence intervals (CI) displayed in Table 4. Based on DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for ASD, 398 of 657 clinically diagnosed cases (60.6%; 95% CI: 57–64%) met the proposed criteria for ASD, with 259 cases (39.4%) failing to meet diagnostic threshold. In terms of specificity, the proposed DSM-5 criteria accurately excluded 262 of 276 (94.9%; 95% CI: 92–97%) individuals. Exploratory analyses were conducted to examine potential discrepancies between individuals carrying a clinical diagnosis of ASD who met or failed to meet DSM-5 criteria. The proportion of individuals (274 of 393 cases, or 69.7%) with lower cognitive ability (i.e., IQ < 70) meeting DSM-5 criteria was significantly higher than the proportion of individuals (109 of 237 cases, or 46.0%) with higher cognitive ability (i.e., IQ ≥ 70) meeting DSM-5 criteria (X2(1)= 34.9, p < .001; 27 individuals with missing IQ data were excluded from this analysis). There were also significant discrepancies in cases meeting DSM-5 diagnostic criteria across clinical diagnoses (X2(2) = 138.3, p < .001); 341 of 450 (75.8%) of cases with a clinical diagnosis of Autistic Disorder, 12 of 48 (25%) of cases with Asperger’s Disorder, and 45 of 159 (28.3%) of cases with PDD-NOS or atypical autism met proposed DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for ASD. Those meeting and failing to meet proposed DSM-5 ASD diagnostic criteria were comparable with respect to chronological age (M = 9.15, SD = 6.92; M = 9.14, SD = 6.85, respectively; t(654) = 0.02, p = .98) and sex ratio (60.4% of males and 63.2% of females met diagnostic criteria; X2(1)= .30, p = .59).

Table 4.

95% Confidence Intervals (CI) for Sensitivity (Se) and Specificity (Sp) values for all cases and cases with IQ ≥ 70.

| DSM-5 Criteria | All Cases (Table 2) | IQ ≥ 70 (Table 3) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Se (95%CI) | Sp (95%CI) | Se (95%CI) | Sp (95%CI) | |

| A. Persistent deficits in social communication and social interaction across contexts, not accounted for by general developmental delays, and manifest by all 3 of the following: | .73 (.70–.77) | .88 (.83–.91) | .58 (.51–.64) | .93 (.87–.97) |

| A1. Deficits in social-emotional reciprocity; ranging from abnormal social approach and failure of normal back and forth conversation through reduced sharing of interests, emotions, and affect and response to total lack of initiation of social interaction. | .96 (.94–.97) | .60 (.54–.66) | .92 (.88–.95) | .67 (.58–.75) |

| • Relative failure to initiate or sustain conversational interchange (at whatever level of language skills are present) in which there is no reciprocal to and from responsiveness to the communications of the other person. | .77 (.74–.80) | .73 (.68–.78) | .74 (.68–.80) | .77 (.68–.84) |

| • Lack of shared enjoyment in terms of vicarious pleasure in other people’s happiness and/or a spontaneous seeking to share their own enjoyment through joint involvement with others. | .76 (.73–.79) | .82 (.77–.87) | .70 (.64–.76) | .90 (.83–.94) |

| • Markedly impaired awareness of others. | .63 (.59–.66) | .89 (.85–.93) | .46 (.39–.52) | .98 (.90–1.0) |

| • Lack of social-emotional reciprocity. | .86 (.83–.89) | .79 (.74–.84) | .80 (.75–.58) | .84 (.76–.90) |

| A2. Deficits in nonverbal communicative behaviors used for social interaction; ranging from poorly integrated- verbal and nonverbal communication, through abnormalities in eye contact and body-language, or deficits in understanding and use of nonverbal communication, to total lack of facial expression or gestures. | .76 (.72–.79) | .82 (.77–.86) | .62 (.55–.68) | .87 (.80–.92) |

| • Markedly abnormal nonverbal communication, as in the use of eye-to-eye gaze, facial expression; body posture, or gestures to initiate or modulate social interaction (e.g., does not anticipate being held, stiffens when held, does not greet parents or visitors, has a fixed stare in social situations). | .76 (.72–.79) | .82 (.77–.86) | .62 (.55–.68) | .87 (.80–.92) |

| A3. Deficits in developing and maintaining relationships, appropriate to developmental level (beyond those with caregivers); ranging from difficulties adjusting behavior to suit different social contexts through difficulties in sharing imaginative play and in making friends to an apparent absence of interest in people. | .96 (.95–.98) | .50 (.44–.56) | .95 (.92–.98) | .51 (.42–.60) |

| • Failure to develop peer relationships as appropriate to developmental level. | .90 (.88–.93) | .60 (.54–.66) | .90 (.86–.94) | .58 (.49–.67) |

| • No or abnormal social play (e.g., does not actively participate in simple games; prefers solitary play activities; involves other children in play only as “mechanical aids”). | .84 (.81–.87) | .71 (.65–.76) | .76 (.70–.81) | .73 (.64–.80) |

|

| ||||

| B. Restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities as manifested by at least two of the following: | .78 (.75–.81) | .67 (61–.73) | .71 (.65–.77) | .74 (.66–.82) |

| B1. Stereotyped or repetitive speech, motor movements, or use of objects; (such as simple motor stereotypies, echolalia, repetitive use of objects, or idiosyncratic phrases). | .80 (.77–.83) | .63 (.57–.69) | .72 (.66–.78) | .76 (.68–.83) |

| • Stereotyped and repetitive use of language or idiosyncratic language. | .52 (.48–.56) | .87 (.82–.91) | .57 (.50–.63) | .88 (.81–.93) |

| • Stereotyped body movements. | .64 (.60–.67) | .73 (.67–.78) | .46 (.39–.52) | .85 (.78–.91) |

| B2. Excessive adherence to routines, ritualized patterns of verbal or nonverbal behavior, or excessive resistance to change; (such as motoric rituals, insistence on same route or food, repetitive questioning or extreme distress at small changes). | .56 (.52–.60) | .85 (.80–.89) | .54 (.47–.60) | .83 (.75–.89) |

| • Apparently compulsive adherence to specific, non-functional, routines or rituals. | .45 (.41–.49) | .90 (.86–.93) | .44 (.37–.50) | .88 (.81–.93) |

| • Distress over changes in small, non-functional, details of the environment. | .41 (.37–.45) | .91 (.86–.94) | .38 (.31–.44) | .90 (.83–.94) |

| B3. Highly restricted, fixated interests that are abnormal in intensity or focus; (such as strong attachment to or preoccupation with unusual objects, excessively circumscribed or perseverative interests). | .48 (.44–.52) | .42 (.36–.48) | .46 (.40–.53) | .44 (.35–.53) |

| • An encompassing preoccupation with stereotyped and restricted patterns of interest. | .48 (.44–.52) | .42 (.36–.48) | .46 (.40–.53) | .44 (.35–.53) |

| B4. Hyper-or hypo-reactivity to sensory input or unusual interest in sensory aspects of environment; (such as apparent indifference to pain/heat/cold, adverse response to specific sounds or textures, excessive smelling or touching of objects, fascination with lights or spinning objects). | .44 (.40–.48) | .86 (.82–.90) | .38 (.31–.44) | .92 (86–.96) |

| • Hyper- or hyposensitivity to sensory stimuli, e.g., hyperacusis. | .44 (.40–.48) | .86 (.82–.90) | .38 (.31–.44) | .92 (.86–.96) |

|

| ||||

| C. Symptoms must be present in early childhood (but may not become fully manifest until social demands exceed limited capacities) | .97 (.95–.98) | .16 (.12–.20) | .95 (.91–.97) | .22 (.16–.31) |

| • Abnormal development prior to age three as manifested by delays or abnormal functioning in social development, language as used in social communication, or play. | .96 (.94–.98) | .30 (.24–.35) | .94 (.90–.97) | .43 (.35–.52) |

| • Onset by 36 months. | .96 (.95–.98) | .17 (.13–.22) | .94 (.90–.96) | .24 (.17–.32) |

|

| ||||

| Overall Diagnostic Status (met criteria A, B, and C) | .61 (.57–.64) | .95 (.92–.97) | .46 (.40–.53) | .98 (.93–1.0) |

Most individuals failing to meet the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria did so because of a failure to meet the social communication criterion (27%) and/or the RRB criterion domain (22%); all but 3% met the onset criterion. To examine the effect of the monothetic versus polythetic approach employed for this criterion, we calculated the proportion of individuals who would meet a polythetic threshold for the social-communication domain. If two of three social communication symptoms (instead of all three) were required, overall sensitivity would increase from .61 to .75 (specific sensitivity for Autistic Disorder, Asperger’s Disorder, and PDD-NOS would be .84, .52, and .55, respectively), with a corresponding decrease in specificity from .95 to .85. To examine the effect of the requirement of at least two RRB symptoms (not required in DSM-IV-TR), we computed the proportion of cases that would meet DSM-5 diagnostic criteria if one or zero RRB was required. If one RRB symptom were required, sensitivity would increase from .61 to .71 (specific sensitivity for Autistic Disorder, Asperger’s Disorder, and PDD-NOS would be .85, .31, and .40, respectively), with a corresponding decrease in specificity from .95 to .91. If zero RBB symptoms were required, sensitivity would increase from .61 to .72 (specific sensitivity for Autistic Disorder, Asperger’s Disorder, and PDD-NOS would be .86, .38, and .42, respectively), with a corresponding decrease in specificity from .95 to .88. With a polythetic threshold for social-communication (two of three criteria) and requirement of one RRB symptom, sensitivity would increase from .61 to .91 (specific sensitivity for Autistic Disorder, Asperger’s Disorder, and PDD-NOS would be .97, .77, and .77, respectively) with a corresponding decrease in specificity from .95 to .75. Finally, if two social-communication criteria and zero RRB symptoms were required (corresponding to the most lenient requirements for PDD-NOS according to DSM-IV-TR criteria), sensitivity would increase from .61 to .94 (specific sensitivity for Autistic Disorder, Asperger’s Disorder, and PDD-NOS would be .98, .88, and .81, respectively) with a corresponding decrease in specificity from .95 to .67.

Given the marked discrepancy in sensitivity between individuals with cognitive impairment (69.7% meeting criteria) and individuals with normative cognitive abilities (46% meeting criteria), we repeated the above analyses on the cognitive able subgroup (IQ ≥ 70, N = 237 with PDD and N = 129 without PDD). Sensitivity and specificity for the DSM-5 algorithm for this subgroup are displayed in Table 3, with 95% confidence intervals displayed in Table 4). Based on DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for ASD, 109 of 237 clinically diagnosed cases (46%) met the proposed criteria for ASD, with 128 cases (54%) failing to meet diagnostic threshold. In terms of specificity, DSM-5 criteria accurately excluded 126 of 129 (98%) individuals. There were also significant discrepancies in cases meeting DSM-5 diagnostic criteria across clinical diagnoses (X2(2) = 46.8, p < .001); 80 of 117 (68.4%) of cases with a clinical diagnosis of Autistic Disorder, 12 of 45 (26.7%) of cases with Asperger’s Disorder, and 17 of 75 (22.7%) of cases with PDD-NOS or atypical autism met proposed DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for ASD.

Most individuals failing to meet the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria did so because of a failure to meet the social communication criterion (42%) and/or the RRB criterion domain (29%); all but 5% met the onset criterion. To examine the effect of the monothetic versus polythetic approach employed for this criterion, we calculated the proportion of individuals that would meet a polythetic threshold for the social-communication domain. If two of three social communication symptoms (instead of all three) were required, overall sensitivity would increase from .46 to .67 (specific sensitivity for Autistic Disorder, Asperger’s Disorder, and PDD-NOS would be .81, .53, and .53, respectively), with a corresponding decrease in specificity from .98 to .93. To examine the effect of the requirement of at least two RRB symptoms (not required in DSM-IV-TR), we computed the proportion of cases that would meet DSM-5 diagnostic criteria if one or zero RRB was required. If one RRB symptom were required, sensitivity would increase from .46 to .54 (specific sensitivity for Autistic Disorder, Asperger’s Disorder, and PDD-NOS would be .79, .31, and .31, respectively), with a corresponding decrease in specificity from .98 to .96. If zero RBB symptoms were required, sensitivity would increase from .46 to .56 (specific sensitivity for Autistic Disorder, Asperger’s Disorder, and PDD-NOS would be .79, .38, and .31, respectively), with a corresponding decrease in specificity from .98 to .95. With a polythetic threshold for social-communication (two of three criteria) and requirement of one RRB symptom, sensitivity would increase from .46 to .85 (specific sensitivity for Autistic Disorder, Asperger’s Disorder, and PDD-NOS would be .97, .76, and .72, respectively) with a corresponding decrease in specificity from .98 to .82. Finally, if two social-communication criteria and zero RRB symptoms were required (corresponding to the most lenient requirements for PDD-NOS according to DSM-IV-TR criteria), sensitivity would increase from .46 to .89 (specific sensitivity for Autistic Disorder, Asperger’s Disorder, and PDD-NOS would be .99, .87, and .76, respectively) with a corresponding decrease in specificity from .98 to .74.

Discussion

The current study examined the impact of the proposed changes to the diagnostic criteria for ASD in DSM-5. We focused on 933 cases referred for evaluation for the presence of a PDD in the DSM-IV field trial. From this sample, we contrasted 657 who had been clinically diagnosed with an ASD and a comparison sample of 276 individuals who received a clinical diagnosis not on the autism spectrum. From 61 individual checklist items rated by these field trial evaluators, we created an algorithm analogous to proposed DSM-5 criteria and determined the proportion of individuals likely to meet criteria for individual DSM-5 symptom items, domain criteria, and overall diagnosis. This re-analysis indicated that, based on proposed DSM-5 criteria, 60.6% of individuals clinically diagnosed with an ASD in the field trial would continue to meet DSM-5 criteria but 39.4% would no longer meet diagnostic criteria. DSM-5 criteria, however, showed excellent specificity, accurately excluding 94.9% who did not receive a clinical diagnosis of ASD. Cases meeting or failing to meet DSM-5 criteria were comparable in terms of chronological age and sex but discrepant with respect to cognitive ability and ASD diagnostic subgroup. Individuals with intellectual disability were more likely than cognitively able individuals to meet DSM-5 criteria (69.7% and 46.0%, respectively). Individuals clinically diagnosed with Autistic Disorder were more likely to pass DSM-5 diagnostic threshold than those with Asperger’s Disorder or PDD-NOS (75.8%, 25.0%, and 28.3%, respectively).

The modifications proposed to diagnostic criteria for ASD appear to result in a more stringent diagnostic threshold. According to the proposed criteria, cognitively able individuals and those with ASDs other than Autistic Disorder would be less likely to receive a diagnosis on the autism spectrum. The proposed change to a spectrum approximates a diagnostic construct closer to classic autism. There also exist fewer ways to arrive at diagnostic threshold, with DSM-5 ASD offering 11 combinations of criteria and DSM-IV Autistic Disorder offering 2,027 combinations. From the group of individuals clinically diagnosed with ASD in the field trial, less than half of those with average cognitive abilities and approximately one quarter of individuals with Asperger’s Disorder or PDD-NOS would continue to meet diagnostic threshold according to DSM-5 criteria. This ostensible reduction in sensitivity is accompanied by very strong specificity, with nearly all individuals carrying non-ASD clinical diagnoses being accurately classified. This change in diagnostic criteria may address a criticism of prior systems that have broadened the spectrum and been associated with increased prevalence rates.32 With regard to both changes in sensitivity and specificity, current analyses suggest considerable public health impact of revised criteria, either alleviating burden on the service system by reducing over-diagnosis and misdiagnosis or potentially denying individuals with subthreshold disability access to services.

Exploratory analyses indicate that the observed changes in sensitivity and specificity are associated with particular characteristics of the revised diagnostic rubric. Rather than changes to the wording or inclusion/omission of any individual criterion, the change to a monothetic versus polythetic symptom set for the social-communication domain had the greatest effect. As suggested by prior work in this journal33, altering DSM-5 criteria to allow 2 of 3 social-communication criteria improves the balance of sensitivity and specificity from .61 and .95 to .75 and .85, respectively. Enacting this change and also lowering the RRB threshold to one symptom raised sensitivity to .91 but lowers specificity to .75. We see these changes as most effective in (a) balancing sensitivity and specificity and (b) preserving continuity of the diagnostic construct with DSM-IV-TR, while (c) maintaining a meaningful conceptual distinction between ASD and SCD (by virtue of the presence of at least one RRB for an ASD diagnosis). Because DSM-5 current are in draft format, pending conclusion of field trials, additional data will soon be obtained to further inform revision of the proposed criteria.

There are several additional issues raised by the transition to a novel set of diagnostic criteria. Based on the observed alterations in the composition of the autism spectrum, DSM-5 will affect the compatibility of future research with prior work. This is a known risk in development of new diagnostic rubrics, and it is particularly relevant in the present case given the quality of research and quantity of resources invested in studies based on the current diagnostic conceptualization. Significant changes in the type of individuals meeting or failing to meet criteria render comparisons of current or historical samples with DSM-5-based samples unreliable. Although overlapping groups of individuals with ASD would be present in historical and future samples, the alteration in nomenclature prevents a straightforward mapping of samples onto one another. These issues could lead to a considerable loss of information given the quantity of research conducted using the current diagnostic system.6 Another obvious challenge of the proposed diagnostic taxon is incompatibility with ICD-10 criteria (and possibly criteria for ICD-11, currently in preparation), rendering it unreliable in future work to compare studies conducted outside of the US with those conducted according to the APA’s standards. Elimination of diagnostic subcategories may be harmful to those who have found a diagnosis important in terms of service acquisition or self-directed insight.26 Collapsing into a spectrum eliminates the possibility of validating subtypes of ASD.25,34,35 Wing, Gould, and Gillberg raised several concerns with the proposed criteria themselves: non-specificity of sensory behavior, omission of a criterion describing lack of imagination, challenges in verifying onset criteria in adults, and problems applying social-communicative criteria in infancy.32

There are several limitations of our study to be addressed in future research. Most importantly, our work compared historical clinical diagnosis with currently proposed criteria and thus may, in part, confound differences in diagnostic cut-offs with evolved perspectives on ASD. For example, it is possible that clinicians in the field trial issued diagnoses based on an outmoded conceptualization of PDD, as DSM-III-R was the current diagnostic model at the time. Thus, it will be vital to examine proposed criteria by field studies that concurrently collect clinical diagnoses according to DSM-IV-TR and DSM-5. Our sample of convenience was based specifically on referral for differential diagnosis of ASD and related disorders and was skewed towards individuals with ASD. As these factors can influence sensitivity and specificity, it will be necessary to examine DSM-5 criteria in more balanced and community-based samples. Because we were drawing from an extant pool of checklist items, we chose the available onset criteria of 36 months. The descriptor of “early childhood” proposed in DSM-5, because it is more vague, may include a wider range of children whose difficulties manifest after age three. This potential confound suggests that it may be helpful to further operationalize “early childhood” to avoid such uncertainty. In either regard, this is minimally consequential with respect to our findings, as 97% of the sample met this 36 month cut-off.

In this study, we did not analyze the proportion of individuals in this sample who would have met criteria for the newly proposed diagnosis, SCD. At present, SCD, is defined purely descriptively and without formal operationalization21; more concrete diagnostic criteria will be helpful in supporting field studies to establish the validity of this diagnostic construct. Despite the vagueness of the description, it is likely that a number of individuals failing to meet DSM-5 criteria for ASD will meet criteria for SCD. It is unclear whether this possibility would compensate for public health ramifications associated with a potential loss of service eligibility; because SCD is entirely new, it cannot be determined to what extent services will be accessible to individuals carrying this diagnosis. A potential problem with SCD as written is that, like PDD-NOS in DSM-IV-TR, it is a loosely defined residual diagnosis and is potentially vulnerable to the same problems encountered with PDD-NOS, such as poor inter-rater agreement on diagnosis, limited insight into associated phenotypic characteristics (e.g., cognitive or neuropsychological function), and disagreement on precise symptom constellation.35

In summation, results of a reanalysis of DSM-IV field trial data indicate that proposed DSM-5 criteria will significantly alter the composition of individuals meeting criteria for an ASD. Most cognitively able individuals and individuals diagnosed with Asperger’s Disorder and PDD-NOS would no longer meet criteria for an ASD. This reduced sensitivity is associated with stronger specificity, with nearly all individuals carrying non-ASD clinical diagnoses being accurately excluded from the spectrum. These changes could exert detrimental effects on service eligibility and the ability of researchers to integrate information from autism research to-date with that conducted under the proposed criteria. Exploratory analyses suggest that, as DSM-5 criteria are finalized, it will be critical to (1) more thoroughly evaluate the transition to a monothetic symptom set for social-communicative symptoms, (2) specifically consider the effects of increasing the number of RRB symptoms required for ASD threshold, and (3) more formally operationalize diagnostic criteria for SCD to enable evaluation of the degree to which it will offset the public health ramifications of changes to ASD criteria.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) grants K23MH086785 (JCM) and P50MH081756 (FRV), a National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression Atherton Young Investigator Award (JCM), and National Institute of Child Health and Human Development grant P50HD003008 (FRV).

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of Adam Naples, Nicole Letsinger, and Timothy Steinhoff, with the Yale Child Study Center.

Footnotes

This article was reviewed under and accepted by Deputy Editor Douglas K. Novins, MD.

Disclosure: Dr. McPartland has received research support from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the Simons Foundation, and the National Institute of Mental Health. He has received royalties from Guilford Press and Lambert Academic Publishing. He has received lecture honoraria for presentations on autism. Dr. Volkmar has received lecture honoraria for presentations on autism. Dr. Reichow has served as a consultant for the Institute of Education Sciences – Small Business Innovation Research. He has received royalties from Springer and Henry Stewart Talks. He has received lecture honoraria for presentations on autism.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.CDC. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorders - Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, United States, 2006. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2009 Dec 18;58(10):1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim YS, Leventhal BL, Koh YJ, et al. Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorders in a Total Population Sample. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(9):904–912. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10101532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wazana A, Bresnahan M, Kline J. The autism epidemic: fact or artifact? J Am Academy Child and Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;46(6):721–730. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e31804a7f3b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fombonne E. Epidemiological studies of pervasive developmental disorders. In: Volkmar FR, Klin A, Paul R, Cohen DJ, editors. Handbook of Autism and Pervasive Developmental Disorders. 3. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2005. pp. 42–69. [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghaziuddin M. Should the DSM V drop Asperger syndrome? J Autism Dev Disord. 2010 Sep;40(9):1146–8. doi: 10.1007/s10803-010-0969-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsatsanis KD. Outcome research in Asperger syndrome and autism. Child & Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2003;12(1):47–63. doi: 10.1016/s1056-4993(02)00056-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV-TR. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller JN, Ozonoff S. Did Asperger’s cases have Asperger disorder? A research note. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1997;38(2):247–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb02354.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buitelaar JK, Van der Gaag R, Klin A, Volkmar F. Exploring the boundaries of Pervasive Developmental Disorder Not Otherwise Specified: Analyses of data from the DSM-IV autistic field trial. J Autism Dev Disord. 1999;29(1):33–43. doi: 10.1023/a:1025966532041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-III. 3. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spitzer RL, Endicott JE, Robbins E. Resarch Diagnostic Criteria. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1978;35:773–82. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1978.01770300115013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-III-R. 3. Washington, D.C: American Psychiatric Association; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spitzer RL, Siegel B. The DSM-III-R field trial of pervasive developmental disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1990;29(6):855–62. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199011000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Volkmar FR. DSM-IV in progress: Autism and the pervasive developmental disorders. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1991;42(1):33–5. doi: 10.1176/ps.42.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Volkmar FR, Cicchetti DV, Bregman J, Cohen DJ. Three diagnostic systems for autism: DSM-III, DSM-III-R, and ICD-10. J Autism Dev Disord. 1992;22(4):483–92. doi: 10.1007/BF01046323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wing L. The current status of childhood autism. Psychol Med. 1979;9(1):9–12. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700021516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mayes SD, Calhoun SL, Crites DL. Does DSM-IV Asperger’s disorder exist? J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2001;29(3):263–271. doi: 10.1023/a:1010337916636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ozonoff S, Griffith EM. Neuropsychological function and the external validity of Asperger syndrome. In: Klin A, Volkmar FR, editors. Asperger syndrome. New York, NY, US: The Guilford Press; 2000. pp. 72–96. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gupta S, Rossignol DA. Autism spectrum disorders: rising prevalence drives research on causes and cures. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2009;21(4):193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.American Psychiatric Association. Proposed draft revisions to DSM disorders and criteria: A 09 Autsm Spectrum Disorder. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2011. [Accessed November 21, 2011]. http://www.dsm5.org/ProposedRevisions/Pages/proposedrevision.aspx?rid=94#. [Google Scholar]

- 22.American Psychiatric Association. Proposed draft revisions to DSM disorders and criteria: A 05 Social Communication Disorder. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2011. [Accessed November 21, 2011]. http://www.dsm5.org/ProposedRevision/Pages/proposedrevision.aspx?rid=489#. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klin A, Lang J, Cicchetti DV, Volkmar FR. Brief report: Interrater reliability of clinical diagnosis and DSM-IV criteria for autistic disorder: results of the DSM-IV autism field trial. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders. 2000;30(2):163–7. doi: 10.1023/a:1005415823867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lord C, Petkova E, Hus V, et al. A Multisite Study of the Clinical Diagnosis of Different Autism Spectrum Disorders [published online ahead of print Nov 2011] Arch Gen Psychiatry. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ghanizadeh A. Can retaining Asperger syndrome in DSM V help establish neurobiological endophenotypes? J Autism Dev Disord. 2011 Jan;41(1):130. doi: 10.1007/s10803-010-1028-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaland N. Brief report: Should Asperger syndrome be excluded from the forthcoming DSM-V? Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2011;5(3):984–9. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Singh J, Illes J, Lazzeroni L, Hallmayer J. Trends in US autism research funding. J Autism Dev Disord. 2009;39:788–95. doi: 10.1007/s10803-008-0685-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Volkmar FR, Klin A, Siegal B, et al. Field trial for autistic disorder in DSM-IV. Am J Psychiatry. 1994 Sep;151(9):1361–7. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.9.1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.World Health Organization. International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems. 2. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992. 10th revision. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Volkmar F, Klin A. Issues in the classification of autism and related conditions. In: Volkmar F, Paul R, Klin A, Cohen D, editors. Handbook of autism and pervasive developmental disorders. 3. Vol. 1. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2005. pp. 5–41. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Klin A, Lang J, Cicchetti DV, Volkmar FR. Brief Report: Interrater Reliability of Clinical Diagnosis and DSM-IV Criteria for Autistic Disorder: Results of the DSM-IV Autism Field Trial. Journal of Autism and Developmental disorders. 2000;30(2):163–167. doi: 10.1023/a:1005415823867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wing L, Gould J, Gillberg C. Autism spectrum disorders in the DSM-V: better or worse than the DSM-IV? Res Dev Disabil. 2011;32(2):768–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2010.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mattila ML, Kielinen M, Linna SL, et al. Autism Spectrum Disorders According to DSM-IV-TR and Comparison With DSM-5 Draft Criteria: An Epidemiological Study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50(6):583–592. e511. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baron-Cohen S. The short life of a diagnosis. [Accessed June 10, 2011];New York Times. 2009 Nov 9; http://www.nytimes.com/2009/2011/2010/opinion/2010baron-cohen.html.

- 35.Mandy W, Charman T, Gilmour J, Skuse D. Toward specifying pervasive developmental disorder-not otherwise specified. Autism research: official journal of the International Society for Autism Research. 2011;4(2):121–31. doi: 10.1002/aur.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]