Abstract

Intervertebral disc degeneration is characterized by a cascade of cellular, biochemical and structural changes that may lead to functional impairment and low back pain. Interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β) is strongly implicated in the etiology of disc degeneration, however there is currently no direct evidence linking IL-1β upregulation to downstream biomechanical changes. The objective of this study was to evaluate long-term agarose culture of nucleus pulposus (NP) cells as a potential in-vitro model system to investigate this. Bovine NP cells were cultured in agarose for 49 days in a defined medium containing transforming growth factor-beta 3, after which both mechanical properties and composition were evaluated and compared to native NP. The mRNA levels of NP cell markers were compared to those of freshly isolated NP cells. Glycosaminoglycan (GAG) content, aggregate modulus and hydraulic permeability of mature constructs were similar to native NP, and aggrecan and SOX9 mRNA levels were not significantly different from freshly isolated cells. To investigate direct links between IL-1β and biomechanical changes, mature agarose constructs were treated with IL-1β, and effects on biomechanical properties, extracellular matrix composition and mRNA levels were quantified. IL-1β treatment resulted in upregulation of ADAMTS4, MMP13 and INOS, decreased GAG and modulus, and increased permeability. To evaluate the model as a test platform for therapeutic intervention, co-treatment with IL-1β and IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1ra) was evaluated. IL-1ra significantly attenuated degradative changes induced by IL-1β. These results suggest that this in vitro model represents a reliable and cost-effective platform for evaluating new therapies for disc degeneration.

Keywords: Intervertebral disc, nucleus pulposus, agarose, interleukin-1 beta, interleukin-1 receptor antagonist, biomechanical properties

Introduction

Intervertebral disc degeneration is characterized by a cascade of cellular, biochemical and structural changes that may ultimately lead to functional impairment and low back pain. This cascade begins in the central nucleus pulposus (NP), where decreasing proteoglycan content and an associated reduction in hydrostatic pressure impair the ability of the NP to perform its most critical role: the even distribution and transfer of compressive loads between the vertebral bodies (Adams et al., 1996; Roughley, 2004).

Inflammatory cytokines play key roles in the etiology of disc degeneration (Freemont, 2009). Interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β) in particular is highly expressed by cells in the degenerate NP (Le Maitre et al., 2005), and has been shown to be associated with increased activity of downstream catabolic enzymes, including those that degrade proteoglycans and collagen (Hoyland et al., 2008; Le Maitre et al., 2004; Le Maitre et al., 2007c). While previous studies have demonstrated that IL-1β induces a catabolic response by NP cells at the molecular level, to date no studies have reported a direct link between these molecular changes and altered biomechanical function. One reason for this is that there is currently a lack of appropriate mimetic model systems that facilitate simultaneous evaluation of cellular events, and molecular, compositional and biomechanical changes associated with disc degeneration.

The molecular and biosynthetic characteristics of NP cells have been studied extensively in three dimensional culture (Yang and Li, 2009). The majority of such studies have used alginate, a hydrogel that preserves the NP cell phenotype, however there is evidence that NP cells are not able to assemble a functional extracellular matrix in alginate (Baer et al., 2001). A smaller number of studies have used agarose, but have been of relatively short duration, and have not evaluated mechanical properties (Fernando et al., 2011; Gokorsch et al., 2004; Horner and Urban, 2001; Sato et al., 2001; Shen et al., 2003; Zeiter et al., 2009). Long term agarose culture has been extensively used to study the behavior of articular cartilage chondrocytes in vitro (Buschmann et al., 1992; Huang et al., 2010; Lima et al., 2008; Mauck et al., 2000). In the presence of specialized chemically defined media, chondrocytes cultured in agarose synthesize mechanically robust, cartilage-like constructs. Due to phenotypic similarities with chondrocytes, (Sive et al., 2002), it was hypothesized that mature NP cells would respond in a similar way when cultured under the same conditions.

The first objective of this study, therefore, was to engineer an in-vitro, biological nucleus pulposus-like construct which reflects the characteristics of the native tissue, including biochemical composition, biomechanical properties and mRNA levels, using long term culture in agarose and a chemically defined medium. The second objective was to investigate effects of IL-1β treatment on the biomechanical properties, extracellular matrix composition and mRNA levels of functionally mature NP cell seeded agarose constructs. Interleukin 1 receptor antagonist (IL-1ra) has shown early promise as a potential therapy for disc degeneration, by inhibiting IL-1β activity (Le Maitre et al., 2007a). The final objective of this study was to examine the ability of IL-1ra to attenuate functional matrix degradation induced by IL-1β.

Methods

Cell Isolation and Agarose Culture

Four caudal intervertebral discs were obtained from each of four fresh adult bovine tails (16 discs total), purchased from a local slaughterhouse according to Institutional guidelines. NP tissue was isolated, placed in high glucose Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) containing 2% penicillin/streptomycin/fungizone (PSF) and incubated overnight at 37°C to verify no bacterial growth. Each sample was then digested for 1 hour in 2.5 mg/ml pronase (66 PUK/mg solid), followed by 4 hours in 0.5 mg/ml collagenase (>125 CDU/mg solid), both at 37 degrees, then filtered through a 70 micron cell strainer. Three aliquots (2 × 105 cells) of these ‘freshly isolated’ cells were retained for comparative mRNA experiments. The remaining isolated cells were expanded in monolayer in high glucose DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% PSF. Passage 2 cells from all donor animals were combined to minimize the effects of inter-donor biological variation, and suspended in a chemically defined medium comprised of high glucose DMEM supplemented with 1% PSF, 0.1 μM dexamethasone, 50 mg/ml ascorbate 2-phosphate, 40 mg/ml L-proline, 100 mg/ml sodium pyruvate, ITS Premix (6.25 μg/ml insulin, 6.25 μg/ml transferrin, 6.25 ng/ml selenious acid), 1.25 mg/ml bovine serum albumin (BSA), 5.35 μg/ml linoleic acid and 10ng/ml of transforming growth factor-beta 3 (TGF-β3). This chemically defined medium has been demonstrated previously to facilitate enhanced matrix deposition over serum alone containing media by both NP cells and articular chondrocytes in three-dimensional culture (Mauck et al., 2006; Reza and Nicoll, 2010b). The cell solution was mixed with an equal volume of 4% sterile, low gelling temperature agarose at a temperature of 49°C such that the final seeding density was 2.0 × 107 cells/ml. While this cell density is higher than the native NP (Maroudas et al., 1975), it was necessary to achieve sufficient levels of functional matrix deposition that would facilitate measurable changes in mechanical properties following cytokine treatments. Gels were cast between 2 glass plates to obtain a slab 2.25 mm thick and individual constructs 4 mm in diameter were then cut using a biopsy punch. Constructs were cultured for 49 days. Agarose (catalogue no. A4018, batch no. 109K1232), collagenase, dexamethasone, L-proline, ascorbate 2-phosphate, linoleic acid and BSA were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St Louis, USA); DMEM, PSF (catalogue no. 15240), sodium pyruvate and FBS (lot #769376) from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, USA); pronase from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany); TGF-β3 from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, USA); ITS Premix from BD Biosciences (Bedford, USA); and sodium pyruvate from Mediatech Inc (Manassas, USA).

Mechanical properties, biochemical composition, histology and mRNA levels were evaluated after 14 and 49 days, and compared with day one properties and native tissue properties.

IL-1β and IL-1ra Treatment

For samples undergoing cytokine treatments, TGFβ-3 was removed from the media 7 days prior to commencing treatments (i.e. at day 42 of agarose culture). Constructs (n=16 per group) were treated with defined media (without TGFβ-3) supplemented with a single dose of recombinant human IL-1β (10 ng/ml), IL-1ra (100 ng/ml), or both IL-1β and IL-1ra together (R&D Systems, Inc; Minneapolis, USA). Dosages were selected based on the results of previous studies (Le Maitre et al., 2005; Le Maitre et al., 2007a) and our own pilot studies. Samples were harvested after 3 days. Mechanical properties, biochemical composition and mRNA levels were evaluated and compared to untreated controls as described below.

Mechanical Testing

Constructs (n = 5) at one, 14 and 49 days of culture, and from each treatment group were tested in confined compression. The testing system consisted of an acrylic chamber fixed above a porous, stainless steel platen (10 μm pore size, 50% void ratio) within a testing bath filled with culture media (without TGFβ-3). To account for variability in sample diameter following agarose culture, six confinement chambers were constructed ranging in diameter from 4.00 to 4.50 mm. Prior to testing, the diameter of each construct was measured using digital calipers and matched to a confinement chamber. Compression was applied using an impermeable ceramic indenter, size-matched to the confinement chamber, attached to a mechanical testing system fitted with a 5 N load cell (Instron; Norwood MA, USA). Samples were initially subjected to a 0.02 N preload held for 500 seconds, followed by a stress relaxation test. This consisted of 10% strain, calculated based on the sample thickness following preload, applied at a rate of 0.05% per second, followed by relaxation to equilibrium for 10 minutes. Aggregate modulus (HA) was calculated as the final, equilibrium stress (equilibrium force/sample area) divided by the applied strain. Hydraulic permeability (k0) was calculated from the relaxation data using linear biphasic theory, assuming material isotropy, as described previously (Soltz and Ateshian, 1998).

Biochemical Composition

Following mechanical testing, samples were weighed and digested overnight in papain at 60°C. Digests were assayed for DNA content using the PicoGreen assay (Invitrogen; Carlsbad, USA), sulfated GAG content using the dimethylmethylene blue (DMMB) technique, and collagen (following acid hydrolysis) using the p-diaminobenzaldehyde/chloramine-T technique for hydroxyproline. Collagen content was calculated assuming a ratio of hydroxyproline to collagen of 1:10 (Nimni, 1983). DNA content was normalized per construct, and GAG and collagen were normalized to construct wet weight. For treatment groups, media aliquots (n=5) were also analyzed for GAG content (normalized per construct) using the DMMB assay.

mRNA Levels

Nine constructs from each culture and treatment group pooled into three groups of three, and the three samples of freshly isolated cells, were used for mRNA analyses. RNA was isolated via two sequential extractions in TRIZOL/chloroform (Invitrogen) and spectrophotometrically quantified (ND-1000; Nanodrop Technologies, Wilmington, USA). Reverse transcription was performed on 1 μg of RNA with random hexamers using a Superscript II kit (Invitrogen Corp; Carlsbad, USA) in a 20 μl volume.

To determine the degree to which the NP cells recovered and/or maintained their phenotype in three-dimensional culture following monolayer expansion, the mRNA levels of aggrecan (ACAN), collagen II (COL2A1), collagen I (COL1A1), collagen VI (COL6A2), SOX9 and cytokeratin 8 (KRT8) after 1, 14, and 49 days of culture in agarose were measured and compared to the mRNA levels of freshly isolated NP cells. ACAN, COL2A1 and SOX9 are general phenotype markers that NP cells share with cartilage chondrocytes, while KRT8 is an NP cell specific marker (Minogue et al., 2010). For treatment groups, we additionally examined mRNA levels of matrix metalloproteinase 13 (MMP13), a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs 4 (ADAMTS4), and inducible nitric oxide synthase (INOS). Primer sequences are provided in Table 1. Primer specificities were confirmed by performing conventional polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and determining amplicon size on agarose gel electrophoresis of the products on a 3% w/v agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide. Optimal annealing temperatures were determined by performing a temperature gradient from 60°C to 50°C using conventional PCR as above. Quantitative PCR was subsequently performed on Applied Biosystems 7500 system using SYBR Green reagents (Applied Biosystems; Carlsbad, USA). Absolute mRNA levels were calculated from standard curves, normalized to glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), and expressed as a ratio to freshly isolated cells (one, 14 and 49 day agarose culture groups) or untreated constructs (treatment groups).

Table 1.

PCR primer sequences

| Primer | Accession Number | Direction (5′->3′) | Sequence | Tm (°C) | Product Length | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACAN | NM_173981.2 | F | CCTGAACGACAAGACCATCGA | 54.29 | 101 | (Fitzgerald et al., 2006) |

| R | TGGCAAAGAAGTTGTCAGGCT | 54.48 | ||||

| ADAMTS4 | NM_181667.1 | F | AACTCGAAGCAATGCACTGGT | 54.96 | 149 | |

| R | TGCCCGAAGCCATTGTCTA | 53.16 | ||||

| COL1A2 | NM_174520.2 | F | GGTAGCCATTTCCTTGGTGGTT | 54.84 | 102 | |

| R | AATTCCAAGGCCAAGAAGCATG | 53.85 | ||||

| COL2A1 | NM_001113224.1 | F | AAGAAGGCTCTGCTCATCCAGG | 56.09 | 124 | |

| R | TAGTCTTGCCCCACTTACCGGT | 57.04 | ||||

| COL6A2 | NM_001075126.1 | F | CTGGAGAGCCTGGACAGAAG | 53.64 | 95 | (Dimicco et al., 2007) |

| R | GCCTTTGAAACCAGGAACAC | 51.77 | ||||

| GAPDH | NM_001034034.1 | F | ATCAAGAAGGTGGTGAAGCAGG | 54.61 | 101 | (Fitzgerald et al., 2006) |

| R | TGAGTGTCGCTGTTGAAGTCG | 55.17 | ||||

| INOS | NM_001076799.1 | F | GTAACAAAGGAGATAGAAACAACAGG | 52.30 | 146 | This paper |

| R | CAGCTCCGGGCGTCAAAG | 55.52 | ||||

| KRT8 | NM_001033610.1 | F | CCGAGTCCTCTGATGTCCTGTCCA | 59.23 | 86 | This paper |

| R | GCTCCATCTGCAAGGAGCCAATGA | 59.29 | ||||

| MMP13 | NM_174389.2 | F | TGGTCCAGGAGATGAAGACC | 52.51 | 80 | (Fitzgerald et al., 2006) |

| R | TGGCATCAAGGGATAAGGAA | 50.22 | ||||

| SOX9 | XR_083993.1 | F | TGAAGAAGGAGAGCGAGGAG | 52.72 | 128 | This paper |

| R | CTTGTTCTTGCTCGAGCCGTTGA | 57.90 |

Histology

To assess uniformity of the distribution of the synthesized extracellular matrix, 2 samples from the 14 and 49 day culture groups were fixed in 10% buffered formalin immediately at harvest and processed for histology in paraffin. Seven micron-thick sections were stained with either alcian blue or picrosirius red to demonstrate GAG or collagen respectively.

Native Bovine NP Samples

Native bovine NP samples were obtained and properties compared with those of engineered constructs. Samples for biomechanical testing (n=4) were trimmed on a freezing stage microtome to a uniform thickness of approximately 2.5 mm. A biopsy punch was then used to core a central 4 mm diameter plug, and samples were tested in confined compression using the protocol described. Samples for biochemistry were processed identically to agarose constructs and assayed for GAG and collagen.

Statistical Analysis

All results are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Properties of samples after 14 and 49 days of agarose culture were compared to day one properties using unpaired Student’s t-tests. One, 14 and 49 day properties were compared to native NP properties using unpaired Student’s t-tests. To confirm that removal of TGFβ-3 at day 42 had no effect, properties of samples cultured under these conditions were compared to those of samples cultured with TGFβ-3 for the full 49 days using unpaired Student’s t-tests. The mRNA levels for one, 14 and 49 day samples were expressed as a ratio to freshly isolated cells for statistical comparisons. Properties of treated samples were compared to those of untreated samples using unpaired Student’s t-tests. The mRNA levels for treated samples were expressed as a ratio to untreated for statistical comparisons. Significance was defined as two-tailed p<0.05.

Results

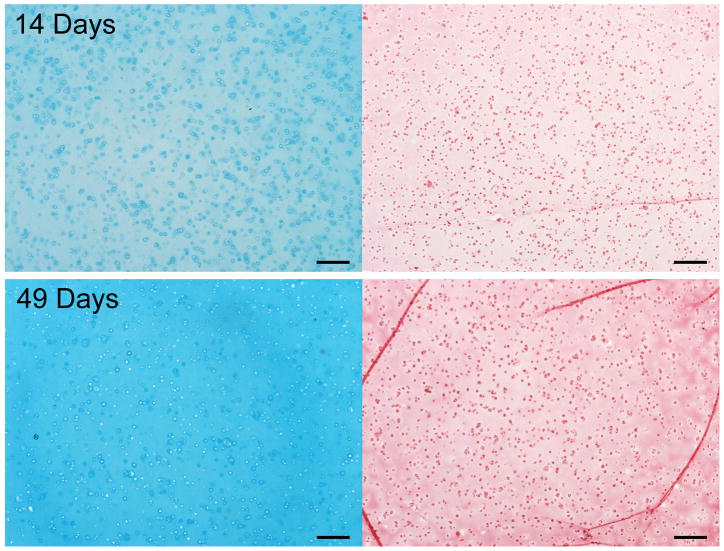

The intensity of GAG and collagen staining increased from 14 days to 49 days of culture in agarose (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Alcian blue (left) and picrosirius red (right) staining after 14 and 49 days of agarose culture showing progressive accumulation of GAG and collagen. Scale bars = 200μm.

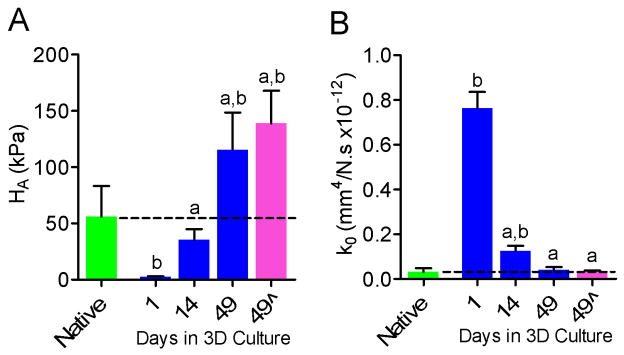

Mean aggregate modulus of constructs increased progressively with culture time, and was significantly greater at 14 days (35 kPa) and 49 days (115 kPa) than at 1 day (2 kPa) (Figure 2A). At day 1 of culture, aggregate modulus of constructs was 2% of the native NP modulus (p<0.05), 63% of native after 14 days culture (not significantly different) and 207% of native after 49 days (p<0.05) (Figure 2A). Hydraulic permeability of constructs decreased progressively with culture time, and was significantly lower at 14 days (0.76 mm4/N.s × 10–12) and 49 days (0.04 mm4/N.s ×10−12) than at 1 day (0.76 mm4/N.s ×10−12) (Figure 2B). At day 1, hydraulic permeability of constructs was 2432% of the native NP permeability (p<0.05), 401% of native after 14 days culture (p<0.05) and 102% of native after 49 days (not significantly different) (Figure 2B). Removal of TGFβ-3 from the culture medium at 42 days had no significant effect on either aggregate modulus (Figure 2A) or hydraulic permeability (Figure 2B) at 49 days compared with constructs cultured for the full 49 days with TGFβ-3.

Figure 2.

Mechanical properties of NP cell-seeded agarose constructs with culture duration and in comparison to native bovine NP (n=5). A. Aggregate modulus, HA. B. hydraulic permeability, k0; aSignificantly different from day 1, p<0.05; bsignificantly different from native NP, p<0.05. Dashed lines represent mean native values. 49^ = TGF-β3 removed from media at day 42.

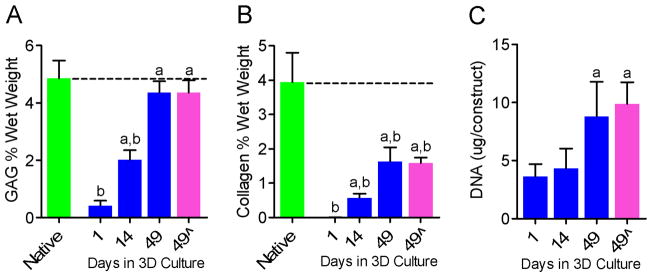

Both GAG and collagen content of constructs increased progressively with culture time, and were significantly greater at 14 days (2.0 and 0.6% wet weight respectively) and 49 days (4.4% and 1.6% wet weight respectively) than at day 1 (0.4 and 0.002% wet weight respectively) (Figures 3A and B). At day 1, GAG content of constructs was 8% of the native NP GAG content (p<0.05), 42% of native after 14 days culture (p<0.05) and 90% of native after 49 days (not significantly different) (Figure 3A). At day 1, collagen content of constructs was 0.05% of the native NP collagen content (p<0.05), 14% of native after 14 days culture (p<0.05) and 41% of native after 49 days (p<0.05) (Figure 3B). DNA content of agarose constructs increased progressively with culture time, and was significantly greater at 49 days than at 14 days or day 1 (Figure 3C). Removal of TGF-β3 from the culture medium at 42 days had no significant effect on either GAG, collagen or DNA content (Figures 3A, B and C) at 49 days compared with constructs cultured for the full 49 days with TGFβ-3.

Figure 3.

Biochemical composition of NP cell-seeded agarose constructs with culture duration and in comparison to native bovine NP (n=5). A. GAG content. B. Collagen content. C. DNA content. aSignificantly different from day 1, p<0.05; bsignificantly different from native NP, p<0.05. Dashed lines represent mean native values. 49^ = TGF-β3 removed from media at day 42.

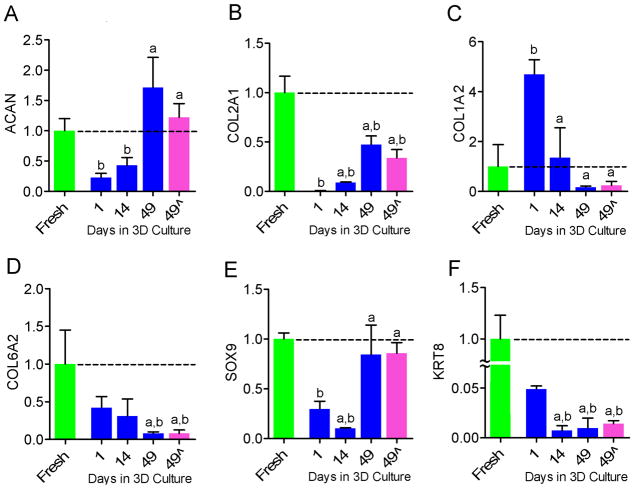

The level of ACAN mRNA at day 1 of agarose culture was 23% of that of freshly isolated cells (p<0.05), 43% after 14 days (p<0.05) and 171% after 49 days (not significantly different) (Figure 4A). The level of COL2A1 mRNA at day 1 of agarose culture was 0.6% of that of freshly isolated cells (p<0.05), 9% after 14 days (p<0.05) and 47% after 49 days (p<0.05) (Figure 4B). The level of COL1A2 mRNA expression at day 1 of agarose culture was 468% of freshly isolated cells (p<0.05), and 135% and 20% of fresh at days 14 and 49 respectively (both not significantly different) (Figure 4C). The ratio of COL1A2 to COL2A1 (%GAPDH) was 0.06 for freshly isolated cells, and 135, 1.07 and 0.06 for 1, 14 and 49 days of agarose culture. The level of COL6A2 mRNA at days 1 and 14 of agarose culture was 42% and 31% of freshly isolated cells respectively (both not significantly different), and 8% after 49 days (p<0.05) (Figure 4D). The level of SOX9 mRNA at day 1 of agarose culture was 30% of that of freshly isolated cells (p<0.05), 10% after 14 days (p<0.05) and 84% after 49 days (not significantly different) (Figure 4E). The mRNA level of the NP cell specific marker KRT8 at day 1 of agarose culture was 5% of that of freshly isolated cells (p<0.05), and 1% after both 14 days and 49 days (p<0.05, Figure 4F). Removal of TGFβ-3 from the culture medium at 42 days had no significant effect on mRNA levels of ACAN, COL2A1, COL1A2, COL6A2 SOX9 or KRT8 (Figures 4A–D) at 49 days compared with samples cultured for the full 49 days with TGF-β3.

Figure 4.

mRNA levels for NP cell-seeded agarose constructs with culture duration and in comparison to freshly isolated cells (n=3). A. ACAN. B. COL2A1. C. COL1A1. D. COL6A2. E. SOX9. F. KRT8. Values are expressed as a ratio to fresh (dashed line). aSignificantly different from day 1, p<0.05; bsignificantly different from Fresh, p<0.05; 49^ = TGF-β3 removed from media at day 42.

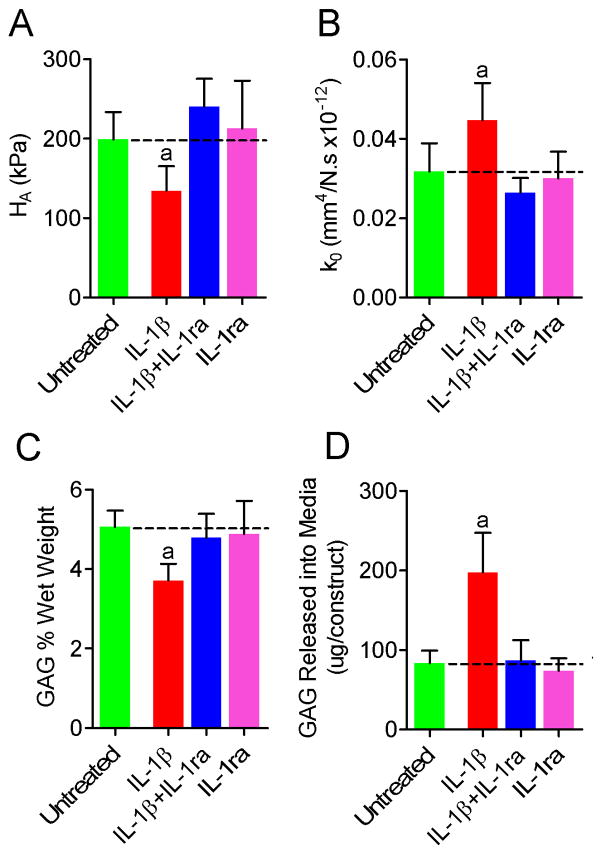

For constructs treated with IL-1β, aggregate modulus was significantly lower and hydraulic permeability was significantly higher than for untreated controls (67% and 141% of untreated respectively, Figures 5A and B). For constructs treated with both IL-1β and IL-1ra, or IL-1ra alone, neither of these properties was significantly different than those of untreated constructs.

Figure 5.

Mechanical properties and biochemical composition of NP cell-seeded agarose constructs following treatment with IL-1β and IL-1ra (n=5). A. Aggregate modulus, HA. B. Hydraulic permeability, k0. C. GAG content. D. GAG released into the media; asignificantly different from untreated, p<0.05; dashed lines represent mean untreated values.

For constructs treated with IL-1β, GAG content was 73% of untreated (p<0.05, Figure 5C) and significantly more GAG was released into the media (Figure 5D). For constructs treated with both IL-1β and IL-1ra, or IL-1ra alone, GAG content was not significantly different from untreated. Neither collagen nor DNA contents were significantly different from untreated for any of the 3 treatment groups.

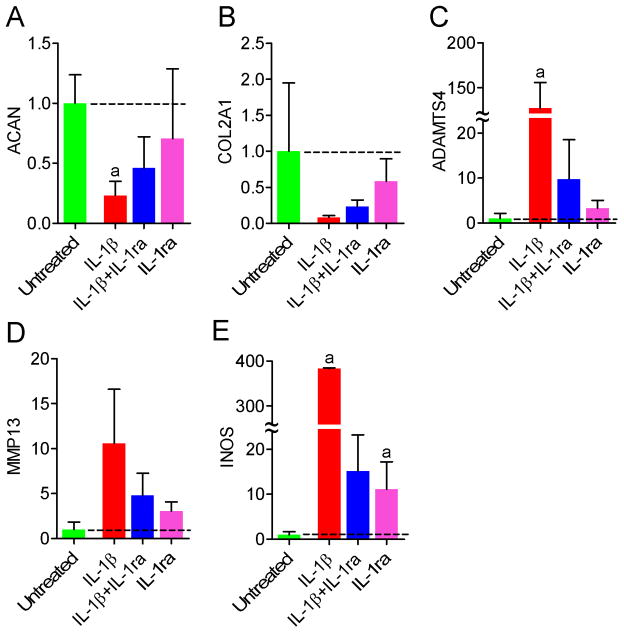

ACAN and COL2A1 mRNAs were both down-regulated by IL-1β treatment (23% (p<0.05) and 8% (not sig.) of untreated respectively, Figures 6A and B). ACAN and COL2A1 mRNAs were also lower than untreated for samples treated with both IL-1β and IL-1ra, and IL-1ra alone, but the differences were not statistically significant. COL1A2, COL6A2, SOX9 and KRT8 mRNA levels were not significantly affected by any treatment (not shown). ADAMST4 and INOS mRNAs were significantly up-regulated by IL-1β treatment (12,730% and 38,330% of untreated, respectively, Figures 6C and E, p<0.05). MMP13 mRNA levels were elevated for IL-1β treated samples, but not significantly (Fig 6D). For samples treated with both IL-1β and IL-1ra, and IL-1ra alone, ADAMTS4 and MMP13 mRNA levels were not significantly different from untreated (Figures 7C and D), while INOS mRNA was elevated with marginal significance (150% (p=0.05) and 111% (p=0.06) of untreated respectively, Figure 6E).

Figure 6.

mRNA levels of phenotypic and catabolic markers in NP cell-seeded agarose constructs following treatment with IL-1β and IL-1ra (n=3). A. ACAN. B. COL2A1. C. ADAMTS4. D. MMP13. E. INOS. Values are expressed as a ratio to untreated (dashed line). aSignificantly different from untreated, p<0.05.

Discussion

In this study we present an engineered three-dimensional model of the nucleus pulposus which exhibits similar composition and mechanical properties to the native tissue. Aggregate modulus and hydraulic permeability of native bovine NP tested in confined compression were of a similar magnitude to that reported previously (Perie et al., 2006), as was the aggregate modulus of acellular 2% agarose (Mauck et al., 2000). As far as the authors are aware, this is the first study to report mechanical properties of engineered NP tested in confined compression.

Monolayer expansion has been demonstrated previously to affect the phenotype of NP cells. Serial passaging of NP cells has been shown to result in a reduction in the expression of type collagen II and aggrecan (Kluba et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2001). The results of the current study show that these key anabolic markers, and the transcription factor SOX9, are significantly reduced after two-dimensional culture. Even after 14 days of three-dimensional culture expression levels are still lower than those of freshly isolated cells. Supportive of our model, the phenotype of the agarose-cultured NP cells was restored only after 49 days of culture in chemically defined media, with levels of aggrecan and SOX9 mRNA similar to levels for freshly isolated cells. Even at this later time point type, however, collagen II expression levels remained significantly lower. These mRNA expression level findings complement the findings for extracellular matrix composition, which showed that after 49 days, GAG content was similar to that of native NP, while collagen content was still significantly lower. The ratio of collagen I to collagen II initially increased relative to freshly isolated cells at the beginning of agarose culture, but returned to native levels after 49 days. This finding is consistent with cells that have de-differentiated towards a fibroblastic phenotype in monolayer culture, but re-differentiated upon return to a 3D environment with extended culture time. While KRT8 expression was significantly lower at day 1 of agarose culture than for freshly isolated cells, expression continued to decrease with extended 3D culture time. KRT8 is more highly expressed by notochordal-like NP cells than mature chondrocyte-like NP cells (Minogue et al., 2010). This suggests that our model may promote differentiation towards a more mature-NP cell like phenotype.

The agarose culture system used in this study has been used extensively for the study of articular chondrocytes (Buschmann et al., 1992; Kelly et al., 2009; Mauck et al., 2000; Mauck et al., 2003). Chondrocytes cultured under these conditions for an extended duration deposit an extracellular matrix with high GAG content and modulus. Further, it has been shown that chondrocytes cultured in this defined medium will synthesize more extracellular matrix than those cultured in serum alone containing media (Mauck et al., 2006). That NP cells and chondrocytes respond to this culture environment in a broadly similar way is in some respects not surprising. Mature NP cells and articular chondrocytes share phenotype similarities, reflected in their mutual high expression of aggrecan, collagen II and SOX9 (Sive et al., 2002). These two cell types however, reside in unique biochemical and micromechanical environments in vivo, and have distinct developmental lineages (Smith et al., 2011). As such, identification of unique markers which differentiate these cell types is being actively pursued (Minogue et al., 2010; Rutges et al., 2010; Sakai et al., 2009; Stoyanov et al., 2011). Transcription profiling of NP cells has suggested a handful of candidates, among them cytokeratin 8, a cytoskeletal protein that is also expressed by notochordal precursors (Gotz et al., 1995; Minogue et al., 2010). An important finding of the current study is that expression levels of cytokeratin 8, in contrast to aggrecan, collagen II and SOX9, are not restored to native levels in three-dimensional culture. This suggests that additional microenvironmental factors that are present in vivo, such as low oxygen tension, pH and glucose, mechanical loading, and molecular signaling from adjacent cell populations may be critical regulators of the NP cell phenotype (Stoyanov et al., 2011). The influence of these factors on NP cell specific markers will be the subject of future investigations.

Nucleus pulposus cells from degenerate human discs express IL-1β both in-situ and 3 dimensional culture (Le Maitre et al., 2006a; Le Maitre et al., 2007b). Furthermore, a positive correlation has been shown between severity of degeneration and levels of IL-1β expression. NP cells from degenerate human discs also express increased levels of catabolic enzymes, including MMPs -1, 3, 7, 13, and ADAMTS-4 (Le Maitre et al., 2006a; Le Maitre et al., 2004; Le Maitre et al., 2007c). Treatment of human NP cells in vitro by IL-1β results in increased activity of these enzymes and INOS, an important intermodulatory mediator of inflammation (Le Maitre et al., 2005; Zhao et al., 2011), demonstrating an association between the IL-1β and these downstream factors. We have confirmed this association in the current study, demonstrating the treatment of NP cells in agarose cultured with IL-1β results in upregulation of key enzymes that degrade interstitial collagens and proteoglycans, as well as the cell stress marker, INOS. Our results highlight the clinical importance of IL-1β signaling in disc degeneration, by linking these associated downstream molecular events to functionally relevant compositional changes. While treatment with IL-1β also resulted in down regulation of anabolic matrix genes aggrecan and collagen II, SOX9 expression was not significantly affected, a finding supported by a previous study on human cells (Le Maitre et al., 2005). Cytokeratin 8 expression was also unaffected.

While IL-1β is upregulated with disc degeneration, there is no concomitant upregulation of the endogenous inhibitor, IL-1ra (Le Maitre et al., 2005). IL-1ra is currently used clinically for the treatment of a rheumatoid arthritis and other inflammatory diseases (Gabay et al., 2010), and it has shown early promise in vitro as a treatment for disc degeneration (Goupille et al., 2007; Le Maitre et al., 2006b; Le Maitre et al., 2007a). Using the in vitro model developed in the current study, we have shown that not only does IL-1ra counteract the deleterious effects of IL-1β at the molecular level, but it effectively inhibits associated compositional and biomechanical changes. To enhance the clinical relevance of these important findings, ongoing work is investigating the effects of introducing IL-1ra to an environment with pre-existing inflammation.

In addition to biological therapies such as IL1ra, NP tissue engineering is being actively pursued as an alternative strategy for restoring disc function (Chou et al., 2009; Reza and Nicoll, 2010a). The results of the current study indicate that implantation of an engineered, biological construct into a disc space where there is substantial inflammation present will result in a significant reduction in the baseline mechanical properties of that implant. Integrating bioactive molecules, such as IL1ra, into implant scaffolds may be an effective means of counteracting these effects.

In this study we describe a tissue engineered model of the nucleus pulposus that closely mimics key functional, compositional and molecular characteristics of the native tissue. This model was used to demonstrate that exposure of NP cells to IL-1β leads to altered mechanical function, primarily due to loss of GAG. Furthermore, it was demonstrated that IL-1ra could effectively inhibit this cascade of catabolic events. In the future, this culture system could be further refined to incorporate additional features of the native NP microenvironment, including low oxygen, glucose and pH, and dynamic loading, all of which could reasonably be expected to further mediate cell behavior. Finally, the model described represents a stable and cost-effective platform for evaluating new therapies for disc degeneration, prior to translation to appropriate in vivo models and ultimately, human clinical use.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by Department of Veterans Affairs Merit Grant IOX RX 000211, NIH Grant R01EB002425 and the Penn Center for Musculoskeletal Disorders.

References

- Adams MA, McNally DS, Dolan P. ‘Stress’ distributions inside intervertebral discs. The effects of age and degeneration. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1996;78:965–972. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x78b6.1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer AE, Wang JY, Kraus VB, Setton LA. Collagen gene expression and mechanical properties of intervertebral disc cell-alginate cultures. J Orthop Res. 2001;19:2–10. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(00)00003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buschmann MD, Gluzband YA, Grodzinsky AJ, Kimura JH, Hunziker EB. Chondrocytes in agarose culture synthesize a mechanically functional extracellular matrix. J Orthop Res. 1992;10:745–758. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100100602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou AI, Akintoye SO, Nicoll SB. Photo-crosslinked alginate hydrogels support enhanced matrix accumulation by nucleus pulposus cells in vivo. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2009;17:1377–1384. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimicco MA, Kisiday JD, Gong H, Grodzinsky AJ. Structure of pericellular matrix around agarose-embedded chondrocytes. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2007;15:1207–1216. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2007.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernando HN, Czamanski J, Yuan TY, Gu W, Salahadin A, Huang CY. Mechanical loading affects the energy metabolism of intervertebral disc cells. J Orthop Res. 2011 doi: 10.1002/jor.21430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald JB, Jin M, Grodzinsky AJ. Shear and compression differentially regulate clusters of functionally related temporal transcription patterns in cartilage tissue. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:24095–24103. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510858200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freemont AJ. The cellular pathobiology of the degenerate intervertebral disc and discogenic back pain. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009;48:5–10. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ken396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabay C, Lamacchia C, Palmer G. IL-1 pathways in inflammation and human diseases. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2010;6:232–241. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2010.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gokorsch S, Nehring D, Grottke C, Czermak P. Hydrodynamic stimulation and long term cultivation of nucleus pulposus cells: a new bioreactor system to induce extracellular matrix synthesis by nucleus pulposus cells dependent on intermittent hydrostatic pressure. Int J Artif Organs. 2004;27:962–970. doi: 10.1177/039139880402701109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotz W, Kasper M, Fischer G, Herken R. Intermediate filament typing of the human embryonic and fetal notochord. Cell Tissue Res. 1995;280:455–462. doi: 10.1007/BF00307819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goupille P, Mulleman D, Chevalier X, Goupille P, Mulleman D, Chevalier X. Is interleukin-1 a good target for therapeutic intervention in intervertebral disc degeneration: lessons from the osteoarthritic experience. Arthritis Res Ther. 2007;9:110. doi: 10.1186/ar2324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horner HA, Urban JP. 2001 Volvo Award Winner in Basic Science Studies: Effect of nutrient supply on the viability of cells from the nucleus pulposus of the intervertebral disc. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2001;26:2543–2549. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200112010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyland JA, Le Maitre C, Freemont AJ. Investigation of the role of IL-1 and TNF in matrix degradation in the intervertebral disc. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008;47:809–814. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ken056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang AH, Stein A, Mauck RL. Evaluation of the complex transcriptional topography of mesenchymal stem cell chondrogenesis for cartilage tissue engineering. Tissue Eng Part A. 2010;16:2699–2708. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2010.0042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly TA, Ng KW, Ateshian GA, Hung CT. Analysis of radial variations in material properties and matrix composition of chondrocyte-seeded agarose hydrogel constructs. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2009;17:73–82. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2008.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kluba T, Niemeyer T, Gaissmaier C, Grunder T. Human anulus fibrosis and nucleus pulposus cells of the intervertebral disc: effect of degeneration and culture system on cell phenotype. Spine. 2005;30:2743–2748. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000192204.89160.6d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Maitre CL, Freemont AJ, Hoyland JA. Localization of degradative enzymes and their inhibitors in the degenerate human intervertebral disc. J Pathol. 2004;204:47–54. doi: 10.1002/path.1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Maitre CL, Freemont AJ, Hoyland JA. The role of interleukin-1 in the pathogenesis of human intervertebral disc degeneration. Arthritis Res Ther. 2005;7:R732–745. doi: 10.1186/ar1732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Maitre CL, Freemont AJ, Hoyland JA. Human disc degeneration is associated with increased MMP 7 expression. Biotech Histochem. 2006a;81:125–131. doi: 10.1080/10520290601005298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Maitre CL, Freemont AJ, Hoyland JA. A preliminary in vitro study into the use of IL-1Ra gene therapy for the inhibition of intervertebral disc degeneration. Int J Exp Pathol. 2006b;87:17–28. doi: 10.1111/j.0959-9673.2006.00449.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Maitre CL, Hoyland JA, Freemont AJ. Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist delivered directly and by gene therapy inhibits matrix degradation in the intact degenerate human intervertebral disc: an in situ zymographic and gene therapy study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2007a;9:R83. doi: 10.1186/ar2282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Maitre CL, Hoyland JA, Freemont AJ, Le Maitre CL, Hoyland JA, Freemont AJ. Catabolic cytokine expression in degenerate and herniated human intervertebral discs: IL-1beta and TNFalpha expression profile. Arthritis Res Ther. 2007b;9:R77. doi: 10.1186/ar2275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Maitre CL, Pockert A, Buttle DJ, Freemont AJ, Hoyland JA. Matrix synthesis and degradation in human intervertebral disc degeneration. Biochem Soc Trans. 2007c;35:652–655. doi: 10.1042/BST0350652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima EG, Tan AR, Tai T, Bian L, Stoker AM, Ateshian GA, Cook JL, Hung CT. Differences in interleukin-1 response between engineered and native cartilage. Tissue Eng Part A Part A. 2008;14:1721–1730. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2007.0347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maroudas A, Stockwell RA, Nachemson A, Urban J. Factors involved in the nutrition of the human lumbar intervertebral disc: cellularity and diffusion of glucose in vitro. J Anat. 1975;120:113–130. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauck RL, Soltz MA, Wang CC, Wong DD, Chao PH, Valhmu WB, Hung CT, Ateshian GA. Functional tissue engineering of articular cartilage through dynamic loading of chondrocyte-seeded agarose gels. J Biomech Eng. 2000;122:252–260. doi: 10.1115/1.429656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauck RL, Wang CC, Oswald ES, Ateshian GA, Hung CT. The role of cell seeding density and nutrient supply for articular cartilage tissue engineering with deformational loading. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2003;11:879–890. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2003.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauck RL, Yuan X, Tuan RS. Chondrogenic differentiation and functional maturation of bovine mesenchymal stem cells in long-term agarose culture. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2006;14:179–189. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minogue BM, Richardson SM, Zeef LA, Freemont AJ, Hoyland JA. Transcriptional profiling of bovine intervertebral disc cells: implications for identification of normal and degenerate human intervertebral disc cell phenotypes. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12:R22. doi: 10.1186/ar2929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimni ME. Collagen: structure, function, and metabolism in normal and fibrotic tissues. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1983;13:1–86. doi: 10.1016/0049-0172(83)90024-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perie DS, Maclean JJ, Owen JP, Iatridis JC. Correlating material properties with tissue composition in enzymatically digested bovine annulus fibrosus and nucleus pulposus tissue. Ann Biomed Eng. 2006;34:769–777. doi: 10.1007/s10439-006-9091-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reza AT, Nicoll SB. Characterization of novel photocrosslinked carboxymethylcellulose hydrogels for encapsulation of nucleus pulposus cells. Acta Biomater. 2010a;6:179–186. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reza AT, Nicoll SB. Serum-free, chemically defined medium with TGF-beta(3) enhances functional properties of nucleus pulposus cell-laden carboxymethylcellulose hydrogel constructs. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2010b;105:384–395. doi: 10.1002/bit.22545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roughley PJ. Biology of intervertebral disc aging and degeneration: involvement of the extracellular matrix. Spine. 2004;29:2691–2699. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000146101.53784.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutges J, Creemers LB, Dhert W, Milz S, Sakai D, Mochida J, Alini M, Grad S. Variations in gene and protein expression in human nucleus pulposus in comparison with annulus fibrosus and cartilage cells: potential associations with aging and degeneration. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2010;18:416–423. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai D, Nakai T, Mochida J, Alini M, Grad S. Differential phenotype of intervertebral disc cells: microarray and immunohistochemical analysis of canine nucleus pulposus and anulus fibrosus. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2009;34:1448–1456. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181a55705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato M, Kikuchi T, Asazuma T, Yamada H, Maeda H, Fujikawa K. Glycosaminoglycan accumulation in primary culture of rabbit intervertebral disc cells. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2001;26:2653–2660. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200112150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen B, Melrose J, Ghosh P, Taylor F. Induction of matrix metalloproteinase-2 and -3 activity in ovine nucleus pulposus cells grown in three-dimensional agarose gel culture by interleukin-1beta: a potential pathway of disc degeneration. Eur Spine J. 2003;12:66–75. doi: 10.1007/s00586-002-0454-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sive JI, Baird P, Jeziorsk M, Watkins A, Hoyland JA, Freemont AJ. Expression of chondrocyte markers by cells of normal and degenerate intervertebral discs. Mol Pathol. 2002;55:91–97. doi: 10.1136/mp.55.2.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith LJ, Nerurkar NL, Choi KS, Harfe BD, Elliott DM. Degeneration and regeneration of the intervertebral disc: lessons from development. Dis Model Mech. 2011;4:31–41. doi: 10.1242/dmm.006403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soltz MA, Ateshian GA. Experimental verification and theoretical prediction of cartilage interstitial fluid pressurization at an impermeable contact interface in confined compression. Journal of Biomechanics. 1998;31:927–934. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(98)00105-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoyanov JV, Gantenbein-Ritter B, Bertolo A, Aebli N, Baur M, Alini M, Grad S. Role of hypoxia and growth and differentiation factor-5 on differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells towards intervertebral nucleus pulposus-like cells. Eur Cell Mater. 2011;21:533–547. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v021a40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JY, Baer AE, Kraus VB, Setton LA. Intervertebral disc cells exhibit differences in gene expression in alginate and monolayer culture. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2001;26:1747–1751. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200108150-00003. discussion 1752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Li X. Nucleus pulposus tissue engineering: a brief review. Eur Spine J. 2009;18:1564–1572. doi: 10.1007/s00586-009-1092-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeiter S, der Werf M, Ito K. The fate of bovine bone marrow stromal cells in hydrogels: a comparison to nucleus pulposus cells and articular chondrocytes. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2009;3:310–320. doi: 10.1002/term.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao CQ, Zhang YH, Jiang SD, Li H, Jiang LS, Dai LY. ADAMTS-5 and intervertebral disc degeneration: the results of tissue immunohistochemistry and in vitro cell culture. J Orthop Res. 2011;29:718–725. doi: 10.1002/jor.21285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]