Abstract

Eph/ephrin signaling has been implicated in various types of key cancer-enhancing processes, like migration, proliferation, and angiogenesis. In medulloblastoma, invading tumor cells characteristically lead to early recurrence and a decreased prognosis. Based on kinase-activity profiling data published recently, we hypothesized a key role for the Eph/ephrin signaling system in medulloblastoma invasion. In primary medulloblastoma samples, a significantly higher expression of EphB2 and the ligand ephrin-B1 was observed compared with normal cerebellum. Furthermore, medulloblastoma cell lines showed high expression of EphA2, EphB2, and EphB4. Stimulation of medulloblastoma cells with ephrin-B1 resulted in a marked decrease in in vitro cell adhesion and an increase in the invasion capacity of cells expressing high levels of EphB2. The cell lines that showed an ephrin-B1–induced phenotype possessed increased levels of phosphorylated EphB2 and, to a lesser extent, EphB4 after stimulation. Knockdown of EphB2 expression by short hairpin RNA completely abolished ephrin ligand–induced effects on adhesion and migration. Analysis of signal transduction identified p38, Erk, and mTOR as downstream signaling mediators potentially inducing the ephrin-B1 phenotype. In conclusion, the observed deregulation of Eph/ephrin expression in medulloblastoma enhances the invasive phenotype, suggesting a potential role in local tumor cell invasion and the formation of metastases.

Keywords: adhesion, Eph, EphB2, ephrin-B1, invasion, medulloblastoma

The Eph receptors constitute the largest family of receptor tyrosine kinases identified so far. Receptor binding of ephrin ligands either transmembrane or linked to glycosylphosphatidylinositol results in signaling that can be bidirectional at sites of cell/cell contact.1 Eph receptor forward signaling is known to be essential for neural development, mediating cytoskeleton dynamics, guided migration, cell proliferation, and angiogenesis.1–5 Ephrins can also transduce a reverse signal into the cell. This reverse signaling is dependent on PDZ (Psd-95 [postsynaptic density protein], DlgA[Drosophiladisc large tumor suppressor], ZO1 [Zonula Occludens–1 protein]) and has recently been implicated in neural development and mediation of axon guidance.6

Eph receptor and ephrin expression has been observed in various benign human tissues.7 The role of Eph/ephrin signaling, from a tumor perspective, can be divided into effects on the tumor stroma and into direct effects on the tumor cells through induction of migration or proliferation. A key role for reverse signaling downstream of ephrin-B2 in tumor angiogenesis has recently been established. Upon binding of EphB, ephrin-B2 directly activates vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR)2 and VEGFR3, resulting in angiogenesis even in the absence of VEGF.8–10 Furthermore, Eph/ephrin forward as well as reverse signaling have been implicated in a number of malignancies, including glioma, enhancing key cancer-promoting processes like tumor cell migration and proliferation.11–15

The complexity of Eph/ephrin signaling is intriguing because both tumor-promoting and suppressing effects of Eph/ephrin signaling on tumor growth have been reported.16–20 This seeming discrepancy likely depends on the relative expression signature of the Eph/ephrin family members.21 Furthermore, strict selectivity in the activation of downstream signaling pathways has tremendous influence on the phenotype.22 Recently generated kinase activity profiles of primary pediatric brain tumor tissue suggested the presence of Eph receptor kinase activity in medulloblastoma.23 In the current study, we aimed to determine whether aberrant Eph/ephrin signaling plays a role in medulloblastoma progression from a tumor cell perspective.

Medulloblastoma are the most frequent malignant brain tumor occurring during childhood. Local recurrence due to tumor cell migration/invasion is a characteristic feature of medulloblastoma. Furthermore, it exhibits the propensity for leptomeningeal dissemination and local spread.24–26 Up until now the potential role of Eph/ephrin signaling in relation to medulloblastoma tumor cell behavior was unknown. Here we demonstrate overexpression of EphB2 and its corresponding ligand ephrin-B1 in medulloblastoma. Stimulation with ephrin-B1 ligand resulted in a marked decrease in in vitro cell adhesion and an increase in invasion of medulloblastoma cell lines expressing high levels of EphB2. This implicates a selective expression of Eph/ephrin family genes in favor of tumor cell migration. It is tempting to speculate that the observed deregulation of Eph/ephrin expression and function may underlie the invasive character of medulloblastoma.

Materials and Methods

Patient Samples and Cell Lines

All tissue was obtained by surgical resection. Tissue material was histologically evaluated and graded according to World Health Organization 2007 classification.27 Written informed consent and local ethics committee approval were granted for use of the patient material.

The following medulloblastoma cell lines were included in the study: DAOY, Res-300, Res-256, Uw-426, Uw-473, and Uw-402. DAOY was derived from the American Type Culture Collection (LGC Standards). The other medulloblastoma cell lines were characterized (immunohistochemistry) and made available by Dr. Michael S. Bobola (Seattle Children's Hospital Research Institute).28

All cell lines were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium F12 (Invitrogen) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum. All cell cultures contained 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (PAA Laboratories).

Quantitative Reverse Transcriptase Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR)

Eph/ephrin expression levels were determined in 11 primary medulloblastoma samples and in 6 medulloblastoma cell lines. RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen) and cDNA was prepared as described previously.29 Quantitative reverse transcriptase (qRT) PCR was performed on the Bio-rad MyiQ Thermal Cycler platform using SYBR Green I for DNA visualization. Custom primers were designed for all currently identified Eph receptors and ephrin-B ligands (Supplementary material, Table S1; Invitrogen). Expression levels of mRNA were quantified relative to the expression of the housekeeping gene glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate-dehydrogenase using the ΔΔCt method.

Expression in medulloblastoma was compared with expression levels in normal cerebellum tissue (N = 4). Expression in cell lines was compared with commercially available pooled mRNA samples of adult cerebellum (#636535; Clontech) and fetal brain (#636106; Clontech). Expression differences were statistically assessed by 2-tailed Student's t-tests.

Antibody Arrays

Changes in cell signaling were assessed by performing Proteome Profiler antibody arrays (catalog nos. ARY001 and ARY003; R&D Systems) according to manufacturer's instructions. ARY001 contains antibody probes for a panel of receptor tyrosine kinases, including most of the Eph receptors. ARY003 was applied to identify changes in phosphorylation of downstream signaling mediators. After protein binding, phosphorylation was visualized using a pan-pTyr antibody. Scanned images were processed using ImageJ software v.1.41 (National Institutes of Health) followed by relative quantification of signal intensities using ScanAlyze array analysis software (Eisen Lab, Stanford University).

Cell Adhesion Assay

Culturing dishes were coated with laminin or collagen for 2h at 37°C. Cell lines were serum starved for 4 h in medium containing 0.5% fetal calf serum (FCS). After trypsinization, the cells were treated with 2 μg/mL recombinant mouse ephrin-B1 Fc chimera (R&D Sytems), 2 μg/mL recombinant mouse ephrin-A1 Fc chimera (R&D Sytems), or 2 μg/mL ChromPure mouse immunoglobulin (Ig)G, Fc fragment (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) and plated on the coated wells in quadruplicate. After 30 min at 37°C, the wells were washed and the adhered cells were fixed with methanol followed by cell staining with crystal violet (1%). Cell adhesion was quantified by cell counting at high power fields (2 fields per well) and statistically assessed by 2-tailed Student's t-tests.

Cell Invasion Assay

Cell invasion assays were based on the Boyden's chamber technique described previously.30 Transwell inserts (8 μm pore size; Corning Life Sciences) were coated with collagen (10 μg/cm2 in 50 μL) for 2 h at 37°C. The transwell inserts were adjusted to cell culture medium for 30 min prior to cell seeding. Cells were serum starved (0.5% FCS) for 4 h. After trypsinization the cells were treated with 2 μg/mL recombinant mouse ephrin-B1 Fc chimera (R&D Sytems), 2 μg/mL recombinant mouse ephrin-A1 Fc chimera (R&D Sytems), or 2 μg/mL ChromPure mouse IgG, Fc fragment (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) for 15 min prior to plating in the top compartments of the transwell system. The lower compartments contained 5% FCS to create a gradient. After 2.5 h the cells in the upper compartment were removed with cotton swabs and the invaded cells were fixed in methanol followed by staining with crystal violet (1%). Cell invasion was quantified by cell counting at high power fields (2 fields per well) and statistically assessed by 2-tailed Student's t-tests.

Cell Proliferation Assay

Proliferation was assessed by performing bromodeoxyuridine proliferation assays (QIA58) according to manufacturer's instructions (Merck Chemicals).

DNA Bisulfite Treatment and Methylation Analysis

DNA was modified with sodium bisulfite. In summary, 2 μg of DNA were used for bisulfite treatment. DNA was denatured in 0.2 N NaOH at 37°C for 10 min, incubated with 3 M sodium bisulfite at 50°C for 16 h, purified with the Wizard cleanup system (Promega), and desulfonated with 0.3 N NaOH at 25°C for 5 min; then DNA was precipitated with ammonium acetate and ethanol, washed with 70% ethanol, dried, and resuspended in H2O. For the analysis of DNA methylation, bisulfite pyrosequencing was used. For pyrosequencing, we performed PCR. The degree of methylation was calculated using the PSQ HS 96A 1.2 software (Biotage). The methylation status of EphB1-4, EphA2, EphA4-7, and EphA10 in medulloblastoma (N = 15) were compared with their status in normal cerebellum control tissue (N = 4). Primer sequences for bisulfite PCR and pyrosequencing are shown in Supplementary material, Table S1.

DNA quality was assessed by performing multiplex PCR according to the Biomed-2 protocol. Only DNA samples with PCR products of at least 600 bp in size were included in this study.31

EphB2 Gene Expression Knockdown

Early passage DAOY, Res-256, and Uw-402 cells were stably transfected with pLKO.1 Mission short hairpin (sh)RNA vectors (Sigma-Aldrich) against EphB2 using Fugene HD transfection reagent (Roche) according to manufacturer's instructions. Transfected cells were selected and maintained in culture medium containing 1.0 μg/mL puromycin. For a vector control, we used pLKO control vector 1. Knockdown was validated by measuring EphB2 mRNA levels by means of qRT-PCR.

Immunoblotting

Cultured cells were washed with ice cold phosphate buffered saline and scraped in Laemmli sample buffer. Proteins were separated by sodium dodecyl sulphate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transported to nitrocellulose membranes. Blots were incubated overnight at 4°C in 5% bovine serum albumin containing a primary antibody (1:1000 dilution) against P38 (21245; Westburg), phospho-P38 (11253), Erk (21238), phospho-Erk (11246), paxillin (21107), phospho-paxillin (11089), Stat5 (21048), phospho-Stat5 (11048) mTor (21214) or phospho-mTOR (11221), followed by incubation with the appropriate peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:3000; Dako) at room temperature for 1 hr. Antibody binding was visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence. Beta-actin was probed as a protein loading control (200 mg/mL stock; 1:3000; sc-47778 mouse mAb; Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Results

Eph Receptor and Ephrin Ligand Expression

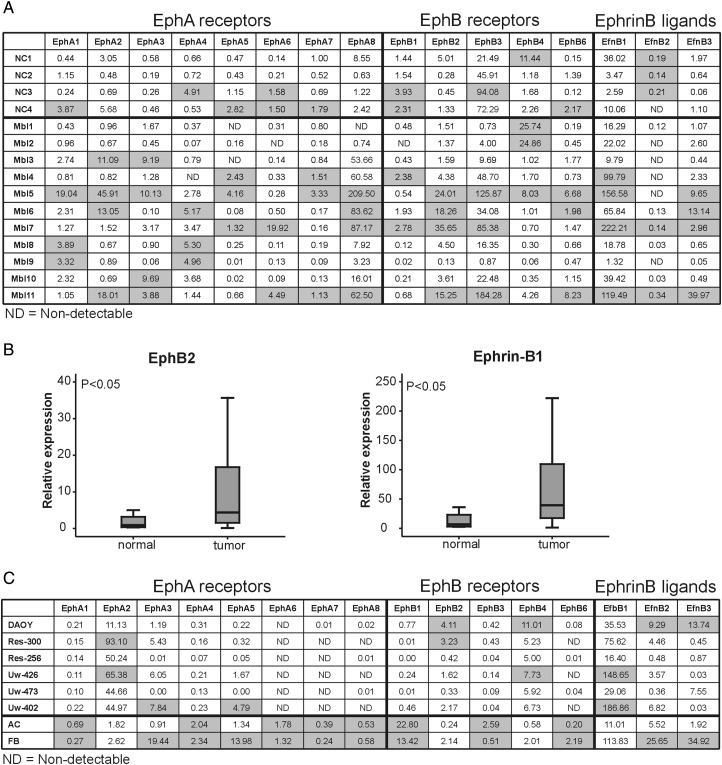

Previously generated kinase activity profiling data of pediatric brain tumors indicated high kinase activity on Eph receptor–derived peptides (Supplementary material, Fig. S1). Although the phosphorylated Eph peptides were derived from specific EphA and EphB receptors, high homology in the primary amino acid sequence of the Eph receptor phosphorylation sites could indicate activity of other EphA and EphB receptors as well. This urged us to address the relevance of the various members of the Eph/ephrin protein family in an unbiased approach. To assess whether aberrant Eph receptor signaling potentially plays a role in medulloblastoma cell behavior, we assessed the mRNA expression of Eph/ephrin family genes in medulloblastoma primary tissue samples and compared it with expression levels in normal cerebellum (Fig. 1A). Expression of all Eph receptors and ephrin-B ligands was observed. A significantly higher expression was observed for the B-type Eph receptor EphB2 and one of its corresponding ligands, ephrin-B1 (P < .05) (Fig. 1B). The A-type Eph receptors EphA3 and -A8 were expressed significantly higher in medulloblastoma as well. No significant differences between normal cerebellum and medulloblastoma tissue were measured for the other receptors and ligands.

Fig. 1.

Significantly increased mRNA expression of EphB2 and ephrin-B1 in a cohort of primary pediatric medulloblastomas. Relative mRNA expression levels of Eph receptors and ephrin-B ligands were determined in a panel of 11 primary medulloblastomas (Mbl) and 4 normal cerebellum samples (NC) (A). Significantly higher expression of EphB2 and ephrin-B1 could be appeciated in the tumor tissue compared with the normal control cerebelli (B). Overexpression of EphB2 was also present in a number of medulloblastoma cell lines (C). Here, expression levels of Eph receptors and ephrin-B ligands were compared with a pooled adult normal cerebellum sample (AC) and a pooled fetal normal brain sample (FB). For each gene the samples with the highest expression are highlighted.

Expression levels in medulloblastoma cell lines were compared with the levels in normal cerebellum and fetal whole brain, indicating an enhanced expression of EphA2, EphB2, and EphB4 in most cell lines (Fig. 1C). Interestingly, corresponding to the expression data of the medulloblastoma tissue, a number of cell lines demonstrated a consistent overexpression of EphB2. Furthermore, multiple cell lines displayed a decreased expression of EphA3 through -A8, EphB1, -B3, and -B6.

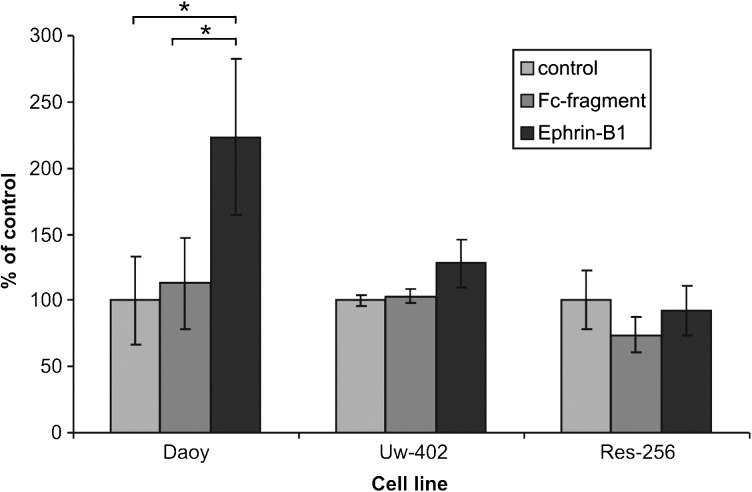

Functional Effects of Eph Receptor Stimulation on Adhesion and Invasion

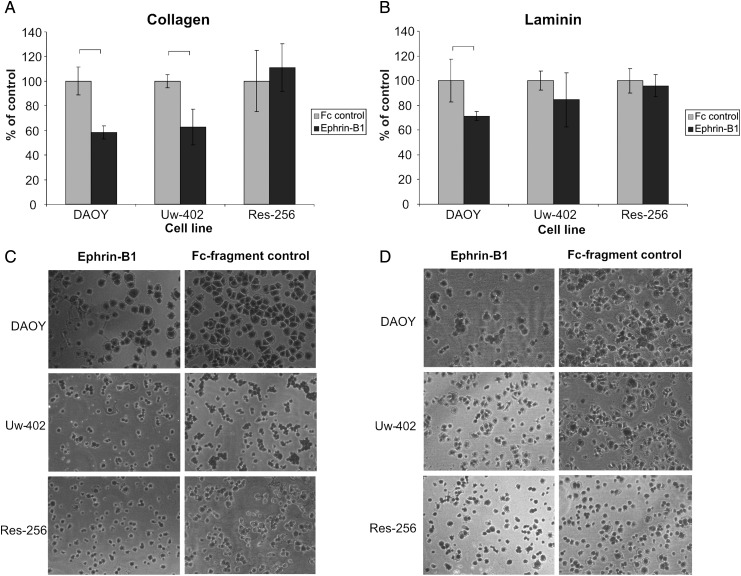

Based on the Eph/ephrin mRNA expression results, we focused on dissecting the functional role of EphB2 forward signaling. To determine the relative importance of the EphB and EphA receptor families, 3 medulloblastoma cell lines with highly differential EphB2 receptor expression levels were stimulated with Fc-conjugated ephrin-A1 or ephrin-B1, upon which the invasion and adhesion capacity was assessed. We selected DAOY, Uw-402, and Res-256, which possess high, intermediate, and low EphB2 expression levels, respectively. Stimulation with ephrin-A1 did not result in an observable phenotype. Ephrin-B1 stimulation, however, showed effects on cell adhesion and invasion that correspond with the relative EphB2 mRNA expression levels in the different cell lines (P < .05). Stimulation with ephrin-B1 markedly increased the invasive capacity of DAOY and, to a lesser extent, Uw-402 in concentrations as low as 0.2 μg/mL, whereas no effects were observed on Res-256 (Fig. 2). The effect of ephrin-B1 on medulloblastoma cell adhesion was assessed on collagen- and laminin-coated culture dishes. Again, no effects could be observed on Res-256, while the adhesive capacity of DAOY and Uw-402 on collagen decreased substantially (Fig. 3). On laminin, ephrin-B1 elicited identical effects on DAOY migration, while the adhesive capacity of Uw-402 seemed to be unaffected.

Fig. 2.

Increased invasion capacity of DAOY medulloblastoma cells upon stimulation with ephrin-B1. In a transwell migration assay, stimulation of DAOY medulloblastoma cells with ephrin-B1 (2 μg/mL) resulted in a marked increase of the invasion capacity of the cells compared with untreated and Fc-fragment–treated control cells (P < .05). The cell lines Uw-402 and Res-256 did not show an altered invasion rate.

Fig. 3.

Decreased cell adhesion of the medulloblastoma cell lines DAOY and Uw-402 upon stimulation with ephrin-B1. Cell adhesion was assessed on a collagen (A and C) and laminin (B and D) matrix. Stimulation of DAOY cells with ephrin-B1 resulted in a sharp decrease in adhesion compared with Fc-fragment control and untreated cells (data not shown) on both collagen and laminin (P < .05). Uw-402 showed the same phenotype on collagen. Res-256, a cell line with low EphB2 expression and phosphorylation, did not show altered cell adhesion upon stimulation with ephrin-B1.

In bromodeoxyuridine incorporation assays, no direct effect on cell proliferation was measured upon stimulation with either ephrin-A1 or ephrin-B1 (data not shown).

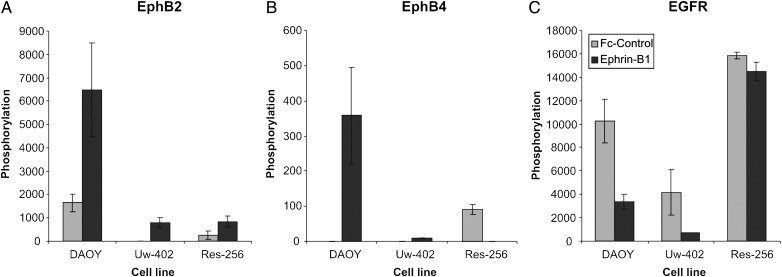

Effects of Ephrin-B1 Stimulation on Receptor Tyrosine Kinase Phosphorylation Levels

We assessed the phosphorylation levels of the Eph receptors in the selected cell lines at basal levels and upon stimulation (Fig. 4A and B, Supplementary material, Table S2). Under basal conditions, phosphorylated EphB2 could be detected only in DAOY and Res-256 at very low amounts. Low levels of phospho-EphB4 could be detected in Res-256. Stimulation of the cells with ephrin-B1 rendered a substantial increase of phosphorylated EphB2 and EphB4 in DAOY. To a lesser extent Uw-402 also showed an increased phosphorylation of these receptors, as well as EphA1 and EphA2 upon stimulation (see also Supplementary material, Table S2). Stimulation of Res-256 did not result in increased phosphorylation of these receptors. Intriguingly, the observed increase in Eph receptor phosphorylation upon stimulation with ephrin-B1 ligand, as observed for DAOY and Uw-402, was accompanied by a sharp decrease in phosphorylation of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

Increased phosphorylation of EphB2 and EphB4 upon stimulation with ephrin-B1 receptors. Medulloblastoma cell lines were stimulated with ephrin-B1 or Fc-fragment control for 15 min. Subsequently, the phosphorylation of 42 different human receptor tyrosine kinases was assessed applying antibody array screening (Supplementary material, Table S2). Stimulation resulted in a marked increase in EphB2 (A) and EphB4 (B) phosphorylation in DAOY and Uw-402. No increase in EphB2 and EphB4 phosphorylation could be observed in Res-256, which also possessed only minor mRNA expression of these receptors. The highest basal EphB2 phosphorylation was measured for DAOY, whereas Uw-402 and Res-256 did not show any EphB2 phosphorylation in unstimulated conditions. Strikingly, the change in phosphorylation of EphB2 and EphB4 as observed for DAOY and Uw-402 was accompanied by a marked decrease in EGFR phosphorylation (C). For Res-256, which showed only minor change in Eph receptor phosphorylation upon stimulation with ephrin-B1, no effects on EGFR phosphorylation could be observed.

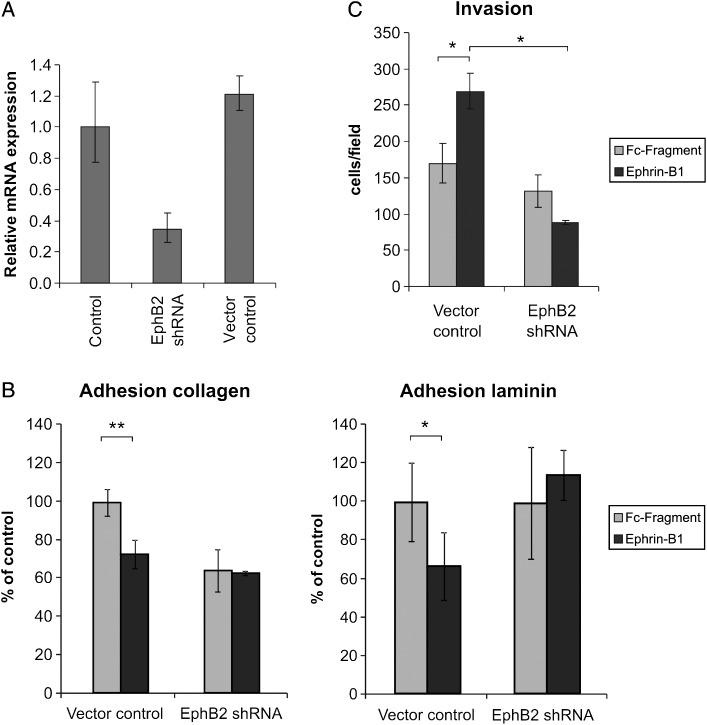

Knockdown of EphB2 Abolishes Functional Effects of Ephrin-B1

To validate the functional relevance of EphB2 in medulloblastoma, DAOY cells were stably transfected with shRNA against EphB2, resulting in a marked knockdown of mRNA expression of this receptor (Fig. 5A). This knockdown completely abolished the ephrin-B1–induced effects on cell adhesion and invasion (Fig. 5B and 5C). Furthermore, EphB2 shRNA transfected DAOY cells displayed a decrease in basal invasion capacity and decreased adhesion on collagen matrix. These results show that activation of EphB2 receptor essentially drives the ephrin-B1–induced invasive phenotype we observed in the DAOY medulloblastoma cell line.

Fig. 5.

Knockdown of EphB2 expression abolishes the ephrin-B1–induced effects on DAOY cell adhesion and invasion capacity. DAOY medulloblastoma cells were stably transfected with either shRNA against EphB2 or shRNA empty vector control (A). The decrease in EphB2 expression abolished the ephrin-B1–induced decrease in cell adhesion on collagen as well as laminin matrix, whereas the effect of receptor stimulation remained present in cells transfected with the shRNA control vector (B) (*P < .03; **P < .01). The invasive capacity of the medulloblastoma cells was assessed by means of transwell invasion assays (C). Here, the increased invasion upon ephrin-B1 stimulation could no longer be observed after EphB2 knockdown (*P < .01).

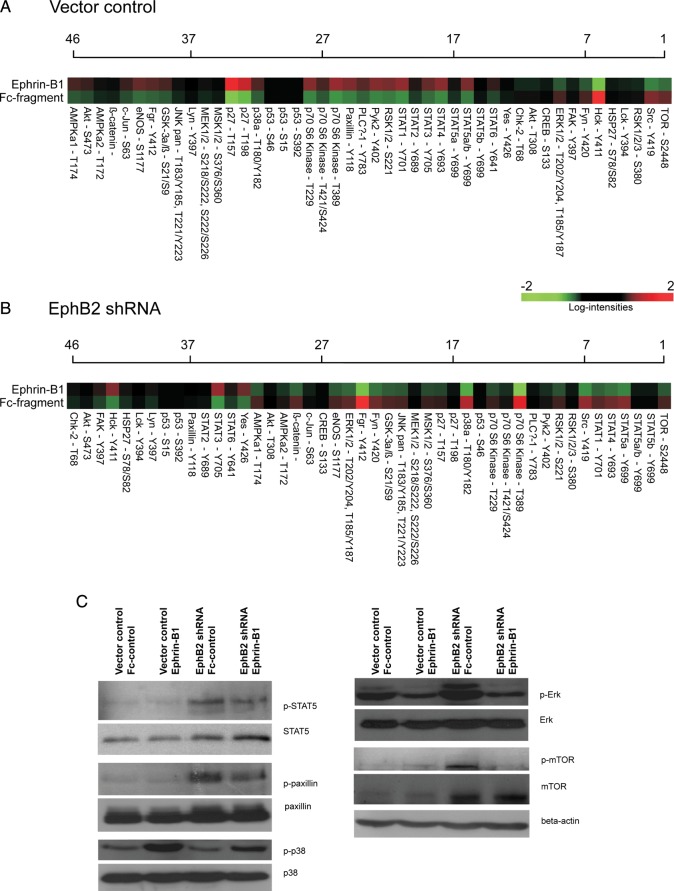

Effects of Ephrin-B1 Stimulation on Downstream Cell Signaling in DAOY and EphB2 shRNA Transfected DAOY

By means of phospho-proteome profiler antibody arrays, insight was gained into altered downstream signal transduction upon stimulation with ephrin-B1 (15 min) and/or EphB2 knockdown (Fig. 6; Supplementary material, Table S3). We observed multiple changes in the downstream signaling phospho-proteome. In vector control cells, stimulation with ephrin-B1 resulted in decreased levels of phosphorylated Erk, Hck, and mTOR and increased activity of Stat1/2/4/5a/6, p38, MSK1/2, RSK1/2, c-Jun, PLCγ-1, p27, and paxillin. Knockdown of EphB2 raised basal phosphorylation levels of multiple kinases, including Erk1/2, MSK1/2, mTOR, p27, paxillin, PLCγ-1,Stat1/4/5a, p27, and RSK1/2. The effects on kinase phosphorylation reported in vector control cells were abolished or even reversed for Hck, Stat1/4/5a, p38, MSK1/2, RSK1/2, c-Jun, Pyk-2, PLCγ-1, and p27. This indicates that multiple prominent cell signaling pathways are affected by altered EphB2 activity. Changes in members of the PI3K–Akt–mTOR pathway as well as the Ras–Raf–MEK–Erk pathway were observed. Furthermore, there is altered activity of renowned mediators of cell migration such as p27 and paxillin, providing a cell biological explanation for the observed pro-migratory phenotype of DAOY. Stat5, paxillin, p38, pErk, and mTOR were selected as representatives of key signal transduction pathways potentially involved in the studied phenotypes. Changes in the phosphorylation status of these proteins were validated by western blot (Fig. 6C). EphB2 knockdown increased basal levels of phosphorylated Stat5, paxillin, Erk, and mTOR and decreased phosphorylation of p38. Upon EphB2 knockdown, increased phosphorylation of p38 and mTOR resulting from stimulation with Ephrin-B1 decreased and reversed, respectively. Ephrin-B1 stimulation induced a mild decrease in the levels of phosphorylated Stat5 and paxillin in EphB2 knockdown cells.

Fig. 6.

Downstream cell signaling in DAOY medulloblastoma cells in response to ephrin-B1 stimulation changes upon EphB2 knockdown. DAOY control cells (A) as well as EphB2 shRNA transfected DAOY cells (B) were treated with ephrin-B1 or Fc-fragment control (15 min), upon which the downstream signal transduction activity was assessed by means of phospho-proteome profiling (Supplementary material, Table S4). Changes in phosphorylation levels of multiple cell signaling mediators upon ephrin-B1 stimulation are abolished or inverted as a result of EphB2 knockdown. Five representatives from key signal transduction pathways potentially involved in the studied phenotypes were selected and validated by phospho-specific western blotting (C).

Interestingly, stimulation with Ephrin-B1 enhanced the effect of a higher receptor expression on downstream signaling through p38 and Erk; for mTOR, ephrin-B1 stimulation achieved the opposite.

Eph Promoter Methylation in Tumor Samples and Cell Lines

Recently, Kuang et al.11 provided evidence for epigenetic silencing as an important regulatory mechanism in the expression of Eph/ephrin family genes in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Based on the observed Eph/ephrin expression pattern, we hypothesized a similar regulatory mechanism in medulloblastoma. We performed methylation analysis of the Eph promoters in a set of primary medulloblastoma samples. This did not indicate a changed promoter methylation of the Eph receptors in medulloblastoma compared with normal cerebellum (Supplementary material, Table S4).

Discussion

Increasing evidence points to a crucial role for Eph/ephrin signaling in cancer progression by coordinating essential cell migratory and invasive processes. Solid tumors, including medulloblastoma, are characterized by a profound invasion of tumor cells into surrounding tissue, thus complicating treatment and resulting in relapse and the development of metastases. We sought to clarify the role of Eph/ephrin signaling in medulloblastoma progression and identified a key role for EphB2 signaling in tumor cell adhesion and invasion.

Our data point to a selective overexpression of EphB2 and its corresponding ligand ephrin-B1 in medulloblastoma. Recently, gene expression data of a larger cohort of medulloblastomas were published by Kool et al.,32 showing a significant increase in the expression of EphB2 and ephrin-B1 compared with normal cerebellum as well, thus confirming the expression changes we found in our cohort. One might speculate that the dramatic effects we observed on in vitro cell adhesion and invasion were indicative of a role in the local spread of the tumor, thus contributing to the formation of metastases or local relapse. Nakada et al.12 previously reported a role for EphB2 signaling in glioblastoma adhesion and migration as well as proliferation. The fact that we observed no direct effects on medulloblastoma proliferation is supported by recent literature describing how EphB2-induced migration and proliferation are controlled independently by activation of distinct pathways.22 The exact role of Eph/ephrin signaling in local recurrence and formation of metastases should be clarified by means of future in vivo experiments.

An increase in the phosphorylation levels of EphA1 and -A2 could be appreciated in the medulloblastoma cell line Uw-402 upon stimulation with ephrin-B1. Although no phenotype was observed stimulating medulloblastoma cell lines with ephrin-A1, our results are indicative of a modest activation of the A-type Eph receptors by ephrin-B1 in Uw-402. Promiscuity in receptor binding of ephrin ligands has been observed previously,3 whereas interaction between ephrin-B1 and A-type Eph receptors has not been described before.

Li et al.16 recently observed a striking decrease in EGFR phosphorylation levels in glioma cell lines upon treatment with ephrin-A5. They show that activation of EphA2 results in recruitment of c-Cbl to EGFR, indicative of ubiquitinylation and subsequent degradation of the EGFR. In addition, Larsen et al.33 showed that EphA2 and EGFR can be co-immunoprecipitated in multiple cell lines, providing evidence for a direct interaction. In our study we observed a decrease in EGFR phosphorylation levels in DAOY and Uw-402 upon treatment with ephrin-B1. Possibly the observed ephrin-B1 phenotype in medulloblastoma is (partly) derived from altered EGFR activity. Curiously, ephrin-A5 has binding affinity for EphB2 as well, so possibly the observed effect of ephrin-A5 on EGFR activity in glioma is caused by EphB2 activation.34 In a more recent study, a reciprocal effect of EGFR activity on the expression of EphA2 was observed in a number of cancer cell lines, including glioma.35 Furthermore, a decreased EGF-induced cell motility was shown upon EphA2 downregulation. In our opinion this underscores the complexity of this protein interaction, which apparently functions bidirectionally.

EphB2 activation in DAOY resulted in decreased phosphorylation of several members of the Ras–Raf–MEK–Erk as well as the PI3K–Akt–mTOR signal transduction pathways. Yang et al.36 previously described a downregulation of Akt–mTOR signaling in response to EphA2 activation in multiple cancer cell types. Possibly this process takes place in response to EphB2 activation in medulloblastoma as well. R-Ras signaling is known to play a key role in medulloblastoma metastasis formation.37 A direct link between EphB2 and R-Ras has been described previously.38 In concurrence with these data, we observed a strong decrease in Erk activity upon EphB2 stimulation. As observed previously for EphA4, Jak/Stat signaling seems to be activated upon stimulation of EphB2.39 Interestingly, we also observed decreased activity of members of this pathway in response to ephrin-B1 stimulation.

Stimulation with ephrin-B1 enhances the effect of increased receptor expression on downstream signaling through p38 and Erk, whereas for mTOR ephrin-B1 stimulation achieves the opposite. Furthermore, the effect of ephrin-B1 stimulation on the phosphorylation status of multiple downstream signaling mediators is still present after EphB2 knockdown. Although the extent of EphB2 silencing cannot prevent residual signaling through EphB2, these results likely reflect promiscuity in Eph receptor activation, as described previously.3

We observed an increased phosphorylation of paxillin and p27 upon EphB2 knockdown, suggesting a role for these kinases in migration and adhesion of medulloblastoma cells upon Eph receptor activation. For p27 a key role in tumor cell motility and migration has been described.40–42 Paxillin is a well-known mediator of cell motility and thus has been implicated in tumor invasion and formation of metastases for a variety of malignancies.43,44 Furthermore, Vindis et al.45 report that EphB1-mediated cell migration requires paxillin activation. Corresponding to our data, the suggestion has recently been made that p27 as well as paxillin play a role in medulloblastoma cell motility.46,47 The exact role of altered signal transduction on the observed phenotypes needs to be clarified. Future studies with constitutively active Eph receptors likely will shed light on the complex but intriguing Eph/ephrin signaling network.

Expression of Eph receptors as well as ephrin ligands was observed in primary medulloblastoma tissue. Likely, the medulloblastoma microenvironment will be highly influenced by alternate Eph receptor and ephrin ligand expression as well. However, targeting Eph/ephrin can elicit effects on the tumor cells and the microenvironment that are not necessarily beneficial from a cancer treatment perspective. Upregulation of ephrin-A1 in endothelial cells and consequent activation of EphA2 has been reported to have an important function in the pro-angiogenic effects of VEGF-A and tumor necrosis factor–α.48,49 Enhanced tumor suppressor signaling in response to EphA2 activation is therefore bound to be accompanied by enhanced tumor angiogenesis.50,51 More recently, a key role for ephrin-B2 reverse signaling in VEGFR2-induced angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis has been reported.9,10 In an ephrin-B2 knockout mouse model, intracranial astrocytoma growth was substantially impaired due to decreased angiogenesis. Possibly the characteristically high vascularity of pilocytic astrocytoma and the presence of VEGFR2 kinase activity are indicative of a role of EphB/ephrin-B signaling as well.52 Whether the observed overexpression of EphB2 in medulloblastoma results in enhanced ephrin-B2–mediated VEGFR2 function, thus inducing tumor angiogenesis, is an intriguing concept that should be the aim of future study. Possibly interplay between B-type Eph receptors and the corresponding ephrin-B ligands is responsible for a tumor-promoting phenotype through enhanced angiogenesis as well as tumor cell invasion.

Although the Eph/ephrin signaling mechanism is still largely unknown, the presence of counteracting effects in response to activation of different Eph receptors is indicative of a tightly controlled balance in the relative expressions of the various receptors that ultimately determines the phenotype. Since the effects of ephrin-B1 stimulation in DAOY stably transfected with EphB2 shRNA resulted in a further decrease of the invasive capacity instead of an increase as observed in normal DAOY cells, one might speculate upon an opposite phenotype due to a perturbed Eph receptor expression balance. Here, no indication for direct epigenetic regulation of Eph expression in medulloblastoma could be observed.

In conclusion, the observed deregulation of Eph/ephrin expression in medulloblastoma enhances the invasive phenotype in vitro. This suggests a potential role in tumor invasiveness and metastasization. Here the complexity of the Eph/ephrin signaling network calls for more detailed tumor-specific insight into the effects of Eph and ephrin signaling inhibition on the tumor as well as the microenvironment to allow potential application as a target for anticancer therapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Michael S. Bobola (Seattle Children's Hospital Research Institute) for making the pediatric brain tumor cell lines available.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the Foundation of Pediatric Oncology Groningen (SKOG-05-001 to A.H.S.).

References

- 1.Pasquale EB. Eph receptors and ephrins in cancer: bidirectional signalling and beyond. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:165–180. doi: 10.1038/nrc2806. doi:10.1038/nrc2806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kullander K, Klein R. Mechanisms and functions of Eph and ephrin signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:475–486. doi: 10.1038/nrm856. doi:10.1038/nrm856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pasquale EB. Eph-ephrin bidirectional signaling in physiology and disease. Cell. 2008;133:38–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.011. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pasquale EB. Eph-ephrin promiscuity is now crystal clear. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:417–418. doi: 10.1038/nn0504-417. doi:10.1038/nn0504-417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brantley-Sieders DM, Fang WB, Hicks DJ, Zhuang G, Shyr Y, Chen J. Impaired tumor microenvironment in EphA2-deficient mice inhibits tumor angiogenesis and metastatic progression. FASEB J. 2005;19:1884–1886. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4038fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bush JO, Soriano P. Ephrin-B1 regulates axon guidance by reverse signaling through a PDZ-dependent mechanism. Genes Dev. 2009;23:1586–1599. doi: 10.1101/gad.1807209. doi:10.1101/gad.1807209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hafner C, Schmitz G, Meyer S, et al. Differential gene expression of Eph receptors and ephrins in benign human tissues and cancers. Clin Chem. 2004;50:490–499. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2003.026849. doi:10.1373/clinchem.2003.026849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Branco-Price C, Johnson RS. Tumor vessels are Eph-ing complicated. Cancer Cell. 2010;17:533–534. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.05.020. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2010.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sawamiphak S, Seidel S, Essmann CL, et al. Ephrin-B2 regulates VEGFR2 function in developmental and tumour angiogenesis. Nature. 2010;465:487–491. doi: 10.1038/nature08995. doi:10.1038/nature08995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang Y, Nakayama M, Pitulescu ME, et al. Ephrin-B2 controls VEGF-induced angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis. Nature. 2010;465:483–486. doi: 10.1038/nature09002. doi:10.1038/nature09002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuang SQ, Bai H, Fang ZH, et al. Aberrant DNA methylation and epigenetic inactivation of Eph receptor tyrosine kinases and ephrin ligands in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2010;115:2412–2419. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-222208. doi:10.1182/blood-2009-05-222208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakada M, Niska JA, Tran NL, McDonough WS, Berens ME. EphB2/R-Ras signaling regulates glioma cell adhesion, growth, and invasion. Am J Pathol. 2005;167:565–576. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62998-7. doi:10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62998-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakada M, Drake KL, Nakada S, Niska JA, Berens ME. Ephrin-B3 ligand promotes glioma invasion through activation of Rac1. Cancer Res. 2006;66:8492–8500. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4211. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zelinski DP, Zantek ND, Stewart JC, Irizarry AR, Kinch MS. EphA2 overexpression causes tumorigenesis of mammary epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61:2301–2306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guo DL, Zhang J, Yuen ST, et al. Reduced expression of EphB2 that parallels invasion and metastasis in colorectal tumours. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27:454–464. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi259. doi:10.1093/carcin/bgi259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li JJ, Liu DP, Liu GT, Xie D. EphrinA5 acts as a tumor suppressor in glioma by negative regulation of epidermal growth factor receptor. Oncogene. 2009;28:1759–1768. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.15. doi:10.1038/onc.2009.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Batlle E, Bacani J, Begthel H, et al. EphB receptor activity suppresses colorectal cancer progression. Nature. 2005;435:1126–1130. doi: 10.1038/nature03626. doi:10.1038/nature03626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Noren NK, Foos G, Hauser CA, Pasquale EB. The EphB4 receptor suppresses breast cancer cell tumorigenicity through an Abl-Crk pathway. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:815–825. doi: 10.1038/ncb1438. doi:10.1038/ncb1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Truitt L, Freywald T, DeCoteau J, Sharfe N, Freywald A. The EphB6 receptor cooperates with c-Cbl to regulate the behavior of breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2010;70:1141–1153. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1710. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davalos V, Dopeso H, Castano J, et al. EPHB4 and survival of colorectal cancer patients. Cancer Res. 2006;66:8943–8948. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4640. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Noberini R, Pasquale EB. Proliferation and tumor suppression: not mutually exclusive for Eph receptors. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:452–454. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.11.008. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2009.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Genander M, Halford MM, Xu NJ, et al. Dissociation of EphB2 signaling pathways mediating progenitor cell proliferation and tumor suppression. Cell. 2009;139:679–692. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.08.048. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2009.08.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sikkema AH, Diks SH, den Dunnen WF, et al. Kinome profiling in pediatric brain tumors as a new approach for target discovery. Cancer Res. 2009;69:5987–5995. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3660. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koeller KK, Rushing EJ. From the archives of the AFIP: medulloblastoma: a comprehensive review with radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2003;23:1613–1637. doi: 10.1148/rg.236035168. doi:10.1148/rg.236035168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laerum OD. Local spread of malignant neuroepithelial tumors. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1997;139:515–522. doi: 10.1007/BF02750993. doi:10.1007/BF02750993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ayan I, Kebudi R, Bayindir C, Darendeliler E. Microscopic local leptomeningeal invasion at diagnosis of medulloblastoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;39:461–466. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(97)00083-7. doi:10.1016/S0360-3016(97)00083-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK, editors. WHO Classification of the Central Nervous System. Lyon: IARC Lyon; 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bobola MS, Silber JR, Ellenbogen RG, Geyer JR, Blank A, Goff RD. O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase, O6-benzylguanine, and resistance to clinical alkylators in pediatric primary brain tumor cell lines. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:2747–2755. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2045. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Bont ES, Fidler V, Meeuwsen T, Scherpen F, Hahlen K, Kamps WA. Vascular endothelial growth factor secretion is an independent prognostic factor for relapse-free survival in pediatric acute myeloid leukemia patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:2856–2861. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roorda BD, ter Elst A, Diks SH, Meeuwsen-de Boer TG, Kamps WA, de Bont ES. PTK787/ZK 222584 inhibits tumor growth promoting mesenchymal stem cells: kinase activity profiling as powerful tool in functional studies. Cancer Biol Ther. 2009;8:1239–1248. doi: 10.4161/cbt.8.13.8688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Dongen JJ, Langerak AW, Bruggemann M, et al. Design and standardization of PCR primers and protocols for detection of clonal immunoglobulin and T-cell receptor gene recombinations in suspect lymphoproliferations: report of the BIOMED-2 Concerted Action BMH4-CT98-3936. Leukemia. 2003;17:2257–2317. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403202. doi:10.1038/sj.leu.2403202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kool M, Koster J, Bunt J, et al. Integrated genomics identifies five medulloblastoma subtypes with distinct genetic profiles, pathway signatures and clinicopathological features. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3088. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003088. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0003088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Larsen AB, Pedersen MW, Stockhausen MT, Grandal MV, van Deurs B, Poulsen HS. Activation of the EGFR gene target EphA2 inhibits epidermal growth factor-induced cancer cell motility. Mol Cancer Res. 2007;5:283–293. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-06-0321. doi:10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-06-0321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Himanen JP, Chumley MJ, Lackmann M, et al. Repelling class discrimination: ephrin-A5 binds to and activates EphB2 receptor signaling. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:501–509. doi: 10.1038/nn1237. doi:10.1038/nn1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Larsen AB, Stockhausen MT, Poulsen HS. Cell adhesion and EGFR activation regulate EphA2 expression in cancer. Cell Signal. 2010;22:636–644. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2009.11.018. doi:10.1016/j.cellsig.2009.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang NY, Fernandez C, Richter M, et al. Crosstalk of the EphA2 receptor with a serine/threonine phosphatase suppresses the Akt-mTORC1 pathway in cancer cells. Cell Signal. 2011;23:201–212. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2010.09.004. doi:10.1016/j.cellsig.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.MacDonald TJ, Brown KM, LaFleur B, et al. Expression profiling of medulloblastoma: PDGFRA and the RAS/MAPK pathway as therapeutic targets for metastatic disease. Nat Genet. 2001;29:143–152. doi: 10.1038/ng731. doi:10.1038/ng731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zou JX, Wang B, Kalo MS, Zisch AH, Pasquale EB, Ruoslahti E. An Eph receptor regulates integrin activity through R-Ras. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:13813–13818. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.13813. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.24.13813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lai KO, Chen Y, Po HM, Lok KC, Gong K, Ip NY. Identification of the Jak/Stat proteins as novel downstream targets of EphA4 signaling in muscle: implications in the regulation of acetylcholinesterase expression. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:13383–13392. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313356200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M313356200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Larrea MD, Wander SA, Slingerland JM. p27 as Jekyll and Hyde: regulation of cell cycle and cell motility. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:3455–3461. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.21.9789. doi:10.4161/cc.8.21.9789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roorda BD, ter Elst A, Scherpen FJ, Meeuwsen-de Boer TG, Kamps WA, de Bont ES. VEGF-A promotes lymphoma tumour growth by activation of STAT proteins and inhibition of p27(KIP1) via paracrine mechanisms. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:974–982. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.12.027. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2009.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wander SA, Zhao D, Slingerland JM. p27: a barometer of signaling deregulation and potential predictor of response to targeted therapies. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:12–18. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0752. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Crowe DL, Ohannessian A. Recruitment of focal adhesion kinase and paxillin to beta1 integrin promotes cancer cell migration via mitogen activated protein kinase activation. BMC Cancer. 2004;4:18. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-4-18. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-4-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Azuma K, Tanaka M, Uekita T, et al. Tyrosine phosphorylation of paxillin affects the metastatic potential of human osteosarcoma. Oncogene. 2005;24:4754–4764. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208654. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1208654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vindis C, Teli T, Cerretti DP, Turner CE, Huynh-Do U. EphB1-mediated cell migration requires the phosphorylation of paxillin at Tyr-31/Tyr-118. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:27965–27970. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401295200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M401295200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nalla AK, Asuthkar S, Bhoopathi P, Gujrati M, Dinh DH, Rao JS. Suppression of uPAR retards radiation-induced invasion and migration mediated by integrin beta1/FAK signaling in medulloblastoma. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13006. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013006. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0013006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bhatia B, Malik A, Fernandez L, Kenney AM. p27(Kip1), a double-edged sword in Shh-mediated medulloblastoma: tumor accelerator and suppressor. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:4307–4314. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.21.13441. doi:10.4161/cc.9.21.13441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cheng N, Brantley DM, Liu H, et al. Blockade of EphA receptor tyrosine kinase activation inhibits vascular endothelial cell growth factor-induced angiogenesis. Mol Cancer Res. 2002;1:2–11. doi:10.1186/1476-4598-1-2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pandey A, Shao H, Marks RM, Polverini PJ, Dixit VM. Role of B61, the ligand for the Eck receptor tyrosine kinase, in TNF-alpha-induced angiogenesis. Science. 1995;268:567–569. doi: 10.1126/science.7536959. doi:10.1126/science.7536959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ireton RC, Chen J. EphA2 receptor tyrosine kinase as a promising target for cancer therapeutics. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2005;5:149–157. doi: 10.2174/1568009053765780. doi:10.2174/1568009053765780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wykosky J, Debinski W. The EphA2 receptor and ephrinA1 ligand in solid tumors: function and therapeutic targeting. Mol Cancer Res. 2008;6:1795–1806. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0244. doi:10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sikkema AH, de Bont ES, Molema G, et al. VEGFR-2 signalling activity in paediatric pilocytic astrocytoma is restricted to tumour endothelial cells. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2011;37:538–548. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2011.01160.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.