Abstract

Although the skeleton is extensively innervated by sensory nerves, the importance of this innervation to skeletal physiology is unclear. Neuronal connectivity between limbs is little studied and likely underestimated. In this study, we examined the effect of bone loading on spinal plasticity in young male Sprague–Dawley rats, using end-loading of the ulna and transynaptic tracing with the Bartha pseudorabies virus (PRV). PRV was inoculated onto the periosteum of the right ulna after 10 days of adaptation to a single period of cyclic loading of the right ulna (1,500 cycles of load at 4 Hz, initial peak strain of −3,750 με). We found that neuronal circuits connect the sensory innervation of right thoracic limb to all other limbs, as PRV was detectable in the dorsal root ganglia (DRG) of left and right brachial and lumbosacral intumescences. We also found that mechanical loading of the right ulna induced plasticity in the spinal cord, with significant augmentation of the connectivity between limbs, as measured by PRV translocation. Within the spinal cord, PRV was predominantly found adjacent to the central canal and in the dorsal horns, suggesting that plasticity in cross-talk between limbs is likely a consequence of dendritic growth, and enhanced connectivity of propriospinal interneurons. In conclusion, the data clearly demonstrate that the innervation of the skeleton exhibits plasticity in response to loading events, suggesting the existence of a dynamic control system that may be of regulatory importance during functional skeletal adaptation.

Keywords: Functional adaptation, Rat, Neuronal plasticity, Sensory innervation

Although the skeleton is composed of a large number of bones, little is known about potential cross-talk between them. The mechanism by which the skeleton senses and responds to loading by altering bone mass is referred to as functional adaptation. Failure of bone to adapt to cyclic loading is common, and results in microscopic fatigue injury accumulation and bone weakening, which may in turn result in fracture(s) developing within the skeleton, particularly in individuals with osteoporosis.

In many regards, physiological processing of skeletal loading events is similar to processing of pain by the nervous system. The skeleton is exquisitely sensitive to loading, particularly dynamic loading, and normally responds to minimal cyclic load and strain [9]. However, the physiological thresholds for functional adaptation are constantly changing through plasticity in the regulatory system; eventually the skeleton accommodates to changes in habitual loading and new bone formation stops [14,15]. Adaptive load-induced bone formation is dependent upon the periodicity, the frequency, and the duration of skeleton loading events [11,14–16]. For example, when 360 cycles of ulnar loading/day, 3 days/week for 16 weeks is delivered as 4 bouts of 90 cycles with 3 hours between bouts, functional adaptation is enhanced, compared with delivery of 360 cycles/day in a single loading period [11].

The physiological mechanism that regulates skeletal adaptation is not fully understood. Adaptation is currently considered by many to be a local phenomenon, meaning that only loaded bones undergo adaptation [1,12]. This perspective is derived from the theory that osteocyte signaling is the principal pathway by which skeletal loading events elicit a local adaptive response, with the extent of adaptation correlating with local tissue strains (see Refs. [5,12], for example); the network of osteocyte dendritic processes within the matrix of bone are well positioned to detect and respond to biophysical stimuli. However, it has been established that the nervous system has important regulatory effects on skeletal metabolism [4,18]. Recent work suggests that this hypothesis regarding regulation of functional skeletal adaptation is not exclusive. For example, mechanical loading of the proximal tibial epiphysis in a mouse model enhances load-dependent bone formation at the tibial mid-diaphysis, a site which does not experience altered in situ strains [19]; this suggests that a cross-talk mechanism exists between different regions of the same bone. Work from our laboratory has extended these observations by suggesting that (1) skeletal responses to loading of a single bone involves multiple bones in different limbs, and (2) this adaptive response is neuronally regulated [13].

The periosteum, a fibrous connective tissue layer that covers the outer surface of bone, is innervated by a dense meshwork of nerves, suggesting the existence of a specialized neuronal regulatory mechanism optimized for detection of mechanical distortion [10]. Through the use of transynaptic viral tracing with attenuated Bartha pseudorabies virus (PRV), anatomic connections have been shown to exist between the distal appendicular skeleton and the brain [3].

The purpose of the present study was to determine whether neuroanatomical connections exist between different limbs and whether such connections are modulated by bone loading. In this study, we identified and quantified neural connectivity between limbs using trans-synaptic PRV tracing. After in vivo bone loading, we found that neuronal connectivity between limbs was enhanced. Our results indicate the existence of complex and dynamic neuronal pathways that have the capacity to enable cross-talk between limbs during adaptation to skeletal loading events.

Ten male Sprague–Dawley rats (10–17 weeks old) were used for this study. Rats were assigned to either a loaded group (n = 4), a sham-loaded group (n = 4), or a baseline group (n = 2). Rats were provided with food and water ad libitum and all procedures were performed in accordance with guidelines of the American Veterinary Medical Association and with approval from the School of Veterinary Medicine Animal Care & Use Committee, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

A standard bone-loading model was used for this study. In this model, the ulna was loaded in such a way that an adaptive response occurs without the induction of microdamage [17]. For bone loading, the antebrachium (forearm) of the rat was placed between horizontally orientated loading cups, which are fixed to the loading platen and actuator of a materials testing machine (Model 8800 DynaMight; Instron, Canton, MA) with a 250 N load cell (Honeywell Sensotec, Canton, MA) [13]. Loading of the right ulna was performed under isofluorane-induced general anesthesia. For analgesia, butorphanol (0.5 mg/kg) was given by subcutaneous injection 15 min before induction and again immediately after loading. The right antebrachium was flexed at the carpus and elbow and placed between an actuator cup and the load cell cup on the materials testing machine. A cyclic compressive load was applied to the ulna using a haversine waveform at 4 Hz, with a peak load of −18.0 N, which equates to an initial peak strain of approximately −3,750 με [13]. All rats were ambulatory within 20 min of recovery from anesthesia. In the sham-loaded group, all procedures were the same, except that the right ulna was not loaded.

PRV inoculation for transynaptic tracing was performed 10 days after loading or sham loading. Previous work has shown that bone neuropeptide concentrations remain persistently altered 10 days after loading, suggesting that neuronal plasticity has been established [13]. For PRV inoculation, general anesthesia was induced and maintained with isofluorane. For analgesia, butorphanol (0.5 mg/kg) was given by subcutaneous injection 15 min before induction and again immediately after surgery. After aseptic preparation of the caudolateral aspect of the right antebrachium, skin and deep antebrachial fascia were incised to expose the periosteum of the right ulna. A Hamilton syringe was used to inject 10.0 μl of PRV onto the periosteum of the mid-diaphysis of the ulna (108 plaque forming units/ml). Retraction of the superficial tissue layers was maintained for approximately 2 min to promote uptake of the virus into the periosteum. The incisions in the deep antebrachial fascia and the skin were then closed.

The 2 rats in the baseline group were used to determine an appropriate survival period after PRV inoculation. Euthanasia was performed at 4 days in one rat and 6 days in the other rat. A 6-day survival period after PRV inoculation was subsequently chosen due to the greater degree of PRV+ dorsal root ganglion (DRG) sensory neurons compared to the 4 day rat, and consequently euthanasia was performed at 6 days in the remaining rats in the study.

During euthanasia, rats were anesthetized with isofluorane and heparin was injected into the left ventricle (0.1 ml, 1,000 IU/ml). Rats were perfused with 200 ml of saline followed by periodate–lysine–paraformaldehyde fixative (PLP; 500 ml of 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer with 10 g of sodium metaperiodate and 6.85 g of lysine). Left and right DRG from the brachial intumescence (C6–T2) and lumbosacral intumescence (L4–S1) and spinal cord segments from the level of the cervicothoracic and thoracolumbar junctions were removed and post-fixed for 2–3 h at 4 °C [2]. Long bones were also removed and decalcified in Tris–EDTA [6].

Tissues were cryoprotected with 20% sucrose and 5% glycerol in 0.1 M phosphate buffer. Spinal cord and DRG were sectioned at 10 μm using a cryostat equipped with the CryoJane® tape transfer system (Instrumedics, St. Louis, MO). PRV immunohistochemistry was performed using a previously established protocol [2]. Sections were washed in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB, 4 × 15 min), pre-treated for 15 min in 0.5% sodium borohydride in 0.01 M phosphate buffered saline (PBS), washed in PB (4 × 15 min), incubated for 15 min in 0.05% hydrogen peroxide and 30% methanol in 0.01 M PBS and then washed in PB (4 × 15 min). Sections were incubated with a rabbit anti-PRV antibody (1:1000; Affinity Bioreagents, Golden, CO, USA) in 0.01 M PBS with 0.3% Triton X-100 and 1% normal goat serum for 36–48 h at 4 °C. Sections were then washed in 0.01 M PB and incubated with biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:200; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) in 2% normal goat serum with 0.03% Triton X-100 in 0.1 M PBS for 60–90 min, washed in 0.01 M PB and incubated with 0.5% ABC Complex (Vectastain Elite Kit, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), washed in 0.01 M PB and incubated with 0.04% 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) in 0.1 M PB with 0.01% hydrogen peroxide. Sections were then washed and protected with mountant and a cover slip.

Multiple tissue sections from the brachial and lumbosacral DRG (25 ± 7 tissue sections per site representing all available sections from each intumescence), and the spinal cord at the level of the cervicothoracic and thoracolumbar junctions, were examined for PRV+ neurons. The long bones from the baseline group were also examined for PRV+ neurons. Digital images were obtained using two microscopes (Nikon Eclipse E600, Nikon Instruments Inc., Melville, NY) equipped with a video camera (Sony DX-390, Scion Corp., Frederick, MA) and a SPOT RT Slider digital camera (Diagnostic Instruments, Sterling Heights, MI). In the loaded and sham-loaded rat DRG tissue sections, the number of PRV+ sensory neurons was quantified in each tissue section. The total area of each of these DRG tissue sections was also measured using image analysis software (ImageJ, NIH, Bethesda, MA), and the density of PRV+ neurons (#/mm2) in the left and right brachial and lumbosacral intumescences in the loaded and sham-loaded rats was determined. At least 4 spinal cord sections from the cervicothoracic and thoracolumbar junctions in each rat were subjectively evaluated for the presence and location of PRV+ neurons.

The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to confirm that data were normally distributed. Each limb was treated as a separate experiment. The Student’s t-test for un-paired data was used for data analysis. Using a Bonferroni correction 1 − (1 − α)1/n with α = 0.05, and n = 4, results with a p value ≤0.0127 were considered significant.

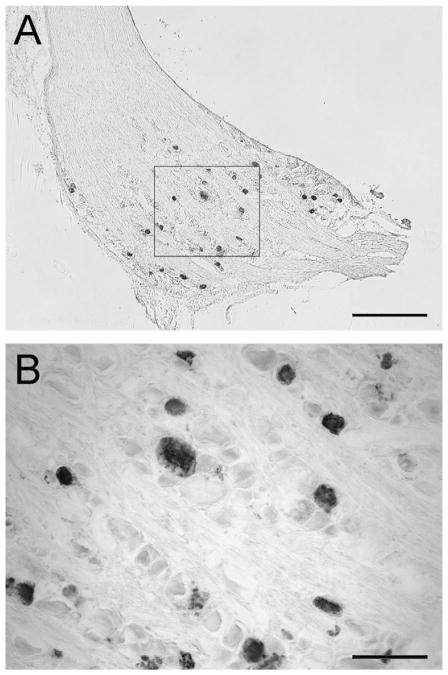

PRV+ sensory neurons were readily identified in the ipsilateral and contralateral brachial and lumbosacral DRG sections (Fig. 1) in both the loaded and sham groups. There was a significantly greater density of PRV+ neurons in the contralateral brachial DRG (p < 0.001) of the loaded group, when compared with the sham-loaded group. Higher numbers of PRV+ neurons were also found in both the contralateral and ipsilateral lumbosacral DRG (p = 0.024, p = 0.0129 respectively) of the loaded group compared to the sham-loaded group (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

(A) Photomicrograph of a section through a dorsal root ganglion (DRG) associated with the right brachial intumescence (C6 –T2 ) with immunohistochemical labeling of the Bartha pseudorabies virus (PRV) tracer, after a 10-day period of functional adaptation to mechanical loading of the right ulna. (B) Higher magnification of PRV+ neurons in the DRG. PRV labeled sensory neurons are evident throughout the DRG. (A) Scale bar = 500 μm; (B) scale bar = 100 μm.

Fig. 2.

Effect of mechanical loading of the right ulna on the number of Bartha pseudorabies virus (PRV) labeled dorsal root ganglion (DRG) sensory neurons after 10 days of adaptation to a single, short period of bone loading. Increased numbers of labeled neuronal cell bodies were found in the contralateral (left) brachial DRG, in response to ulnar loading. Higher numbers of labeled neurons were also found in the left and right DRG in the lumbosacral plexus. Differences between groups are indicated.

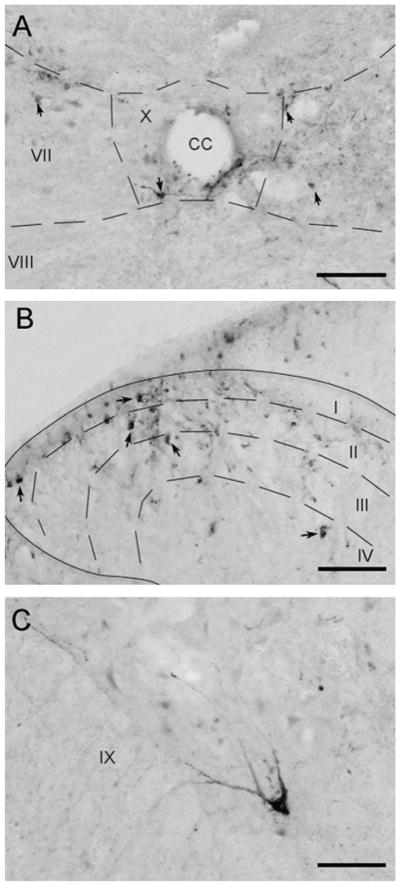

Although not quantified, PRV+ neurons were also noted in spinal cord sections taken at the cervicothoracic and thoracolumbar junctions. PRV+ neurons were seen adjacent to the central canal in and around lamina X, in the dorsal horns in the area of laminae I and II and with variable extension into laminae III and IV, and in lamina IX within the ventral horn (spinal layers according to Paxinos and Watson, The Rat Brain, 5th ed, 2005) (Fig. 3). Spinal cord sections from the cervicothoracic junction of the loaded group had a greater number of PRV+ neurons in both the ipsilateral and contralateral dorsal horns of the spinal cord, compared to the sham-loaded group. Very few PRV+ neurons were found in the ventral horn of the cervicothoracic region, but there were slightly more labeled neurons ipsilaterally in the loaded group compared to the sham-loaded group. In spinal cord sections taken at the level of the thoracolumbar junction, loaded rats again appeared to have a greater number of PRV+ neurons in the ipsilateral and contralateral dorsal horns by comparison with the sham-loaded group. No PRV+ neurons were noted in the ventral horns of sections through the thoracolumbar region.

Fig. 3.

Photomicrographs of coronal sections through the spinal cord taken in the area of the cervicothoracic junction. Arrows highlight PRV+ neurons. (A) PRV+ neurons were noted adjacent to the central canal of the spinal cord in lamina X. (B) PRV+ neurons in the dorsal horn in laminae I, II, III, and IV. (C) A PRV+ motor neuron in laminae IX of the ventral horn. CC, central canal. Scale bars = 100 μm.

Although it has been reported previously that there are neuroanatomical pathways connecting bone marrow and periosteum to the central nervous system via the ganglia of the sympathetic chain [3], the extent of the connectivity of the innervation between thoracic limbs and pelvic limbs, especially sensory pathways, has been studied minimally and is likely underestimated.

Interestingly, although PRV is principally a retrograde transynaptic tracer [3], our data clearly show that the virus also travels anterogradely, demonstrating that the peripheral sensory innervation of different limbs is connected. Our findings can be explained by uptake of PRV into sensory neurons innervating the right ulnar periosteum with subsequent retrograde transport into the spinal cord grey matter. PRV then passes transynaptically into interneurons whose axons extend across to the contralateral and ipsilateral grey matter. Subsequently, PRV passes into the central processes of primary sensory neurons on both sides, from where it is transported to the contralateral brachial DRG and the ipsilateral and contralateral lumbosacral DRG.

Importantly, we have also observed plasticity in these neuronal circuits in response to mechanical loading of the right ulna; mechanical loading of the right ulna enhanced PRV translocation, particularly to the contralateral brachial intumescence DRG. These findings support our hypothesis that the sensory innervation of the skeleton may represent a dynamic control system that is capable of adapting to changes in the biophysical environment that the skeleton is exposed to during daily life [13]. The plasticity in cross-talk between limbs is most likely a consequence of dendritic growth and enhanced connectivity of propriospinal interneurons that are predominantly in the dorsal horns and around the central canal. It is now recognized that these interneurons have the capacity to establish novel intraspinal relay pathways in both the cervical and thoracolumbar spinal cord [7,8]. However, much of this work is focused on propriospinal connections between sensory neurons and motor neurons in different limbs, not sensory neuron to sensory neuron connections.

Functional adaptation of the skeleton is very sensitive to transient loads, exhibits memory for loading events, and also exhibits plasticity or accommodation to habitual loading [11,14–16]. This memory and plasticity has traditionally been thought to reflect a control system in which the osteocytes embedded in the matrix of bone act as the mechanosensory cell of a physiological feedback loop. However, the observations cited above underscore the existence of a neuronally mediated physiological system that may have important regulatory influences on functional adaptation of the skeleton. Memory and plasticity are likely important in ensuring that mechanically induced signaling events, and the associated physiological pathways that regulate adaptation of the skeleton, are optimized over time.

In conclusion, our data support the hypothesis that functional adaptation is in part neuronally regulated. These findings indicate that DRG sensory neurons are modulated by skeletal loading events. Further work is needed to determine whether DRG sensory neurons modulate load-induced bone formation. Bone cells are capable of neurotransmitter synthesis, and thus may directly influence sensory nerve signaling via the direct non-synaptic connections that exist between sensory neurons and bone cells. During skeletal adaptation, plasticity from altered connectivity between neurons in the central nervous system may modulate the sensitivity of DRG sensory neurons to skeletal loading events.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a grant (S-06-9M) from the AO Research Fund of the AO Foundation, Switzerland.

References

- 1.Armstrong VJ, Muzylak M, Sunters A, Zaman G, Saxon LK, Price JS, Lanyon LE. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling is a component of osteoblastic bone cell early responses to load-bearing and requires estrogen receptor alpha. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:20715–20727. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703224200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barker JR, Thomas CF, Behan M. Serotonergic projections from the caudal raphe nuclei to the hypoglossal nucleus in male and female rats. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2009;165:175–184. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2008.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dénes A, Boldogkoi Z, Uhereckzky G, Hornyák A, Rusvai M, Palkovits M, Kovács KJ. Central autonomic control of the bone marrow: multisynaptic tract tracing by recombinant pseudorabies virus. Neuroscience. 2005;134:947–963. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.03.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elefteriou F, Ahn JD, Takeda S, Starbuck M, Yang X, Liu X, Kondo H, Richards WG, Bannon TW, Noda M, Clement K, Vaisse C, Karsenty G. Leptin regulation of bone resorption by the sympathetic nervous system and CART. Nature. 2005;434:514–520. doi: 10.1038/nature03398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gross TS, Edwards JL, McCloud KJ, Rubin CT. Strain gradients correlate with sites of periosteal bone formation. J Bone Miner Res. 1997;12:982–988. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.6.982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hao Z, Kalscheur VL, Muir P. Decalcification of bone for histochemistry and immunohistochemistry procedures. J Histotechnol. 2002;25:33–37. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jankowska E. Spinal interneuronal networks in the cat: Elementary components. Brain Res Rev. 2008;57:46–55. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lane MA, White TE, Coutts MA, Jones AL, Sandhu MS, Bloom DC, Bolser DC, Yates BJ, Fuller DD, Reier PJ. Cervical prephrenic interneurons in the normal and lesioned spinal cord of the adult rat. J Comp Neurol. 2008;511:692–709. doi: 10.1002/cne.21864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lanyon LE, Rubin CT. Static vs dynamic loads as an influence on bone remodeling. J Biomech. 1984;17:897–905. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(84)90003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin CD, Jimenez-Andrade JM, Ghilardi JR, Mantyh PW. Organization of a unique net-like meshwork of CGRP+ sensory fibers in the mouse periosteum: Implications for the generation and maintenance of bone fracture pain. Neurosci Lett. 2007;427:148–152. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.08.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robling AG, Hinant FM, Burr DB, Turner CH. Improved bone structure and strength after long-term mechanical loading is greatest if loading is separated into short bouts. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17:1545–1554. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.8.1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robling AG, Castillo AB, Turner CH. Biomechanical and molecular regulation of bone remodeling. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2006;8:455–498. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.8.061505.095721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sample SJ, Behan M, Smith L, Oldenhoff WE, Markel MD, Kalscheur VL, Hao Z, Miletic V, Muir P. Functional adaptation to loading of a single bone is neuronally regulated and involves multiple bones. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23:1372–1381. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.080407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saxon LK, Robling AG, Alam I, Turner CH. Mechanosensitivity of the rat skeleton decreases after a long period of loading, but is improved with time off. Bone. 2005;36:454–464. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2004.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schriefer JL, Warden SJ, Saxon LK, Robling AG, Turner CH. Cellular accommodation and the response of bone to mechanical loading. J Biomech. 2005;38:1838–1845. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Srinivasan S, Weimer DA, Agans SC, Bain SD, Gross TS. Low-magnitude mechanical loading becomes osteogenic when rest is inserted between each load cycle. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17:1613–1620. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.9.1613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Torrance AG, Mosley JR, Suswillo RFL, Lanyon LE. Noninvasive loading of the rat ulna in vivo induces a strain-related modeling response uncomplicated by trauma or periosteal pressure. Calcif Tiss Int. 1994;54:241–247. doi: 10.1007/BF00301686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yadav VK, Ryu JH, Suda N, Tanaka KF, Gingrich JA, Schütz G, Glorieux FH, Chiang CY, Zajac JD, Insogna KL, Mann JJ, Hen R, Ducy P, Karsenty G. Lrp5 controls bone formation by inhibiting serotonin synthesis in the duodenum. Cell. 2008;135:825–837. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang P, Tanaka SM, Jiang H, Su M, Yokota H. Diaphyseal bone formation in murine tibiae in response to knee loading. J Appl Physiol. 2006;100:1452–1459. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00997.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]